Research | Open Access | Volume 9 (1): Article 22 | Published: 04 Feb 2026

Investigation of the 2024 Aeromonas hydrophila outbreak in Jinja and Luuka, Uganda: A mixed-methods approach

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Tables

| Socio-demographic | Participants (n) | Cases n (%) | No cases n (%) | P-value | Chi-square (χ²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 84 | 44 (52.4) | 40 (47.6) | 0.411 | 0.6768 |

| Female | 101 | 59 (58.4) | 42 (41.6) | ||

| Education | |||||

| None | 10 | 7 (70.0) | 3 (30.0) | 0.102 | 6.2004 |

| Primary | 110 | 52 (47.3) | 58 (52.7) | ||

| Secondary | 21 | 14 (66.7) | 7 (33.3) | ||

| Tertiary or higher | 2 | 0 | 2 (100) | ||

| Marital status | |||||

| Divorced | 3 | 3 (100) | 0 | 0.323 | 3.4818 |

| Married | 55 | 26 (47.3) | 29 (52.7) | ||

| Never married | 81 | 41 (50.6) | 40 (49.4) | ||

| Widowed | 3 | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | ||

| Occupation | |||||

| Business | 5 | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | 0.147 | 12.102 |

| Political leader | 1 | 0 | 1 (100) | ||

| Child | 2 | 2 (100) | 0 | ||

| Health worker | 2 | 0 | 2 (100) | ||

| Housewife | 1 | 0 | 1 (100) | ||

| Mechanic | 1 | 0 | 1 (100) | ||

| Peasant | 66 | 39 (59.1) | 27 (40.9) | ||

| Pupil | 63 | 28 (44.4) | 35 (55.6) | ||

| Student | 2 | 2 (100) | 0 | ||

| Geographical Area of Origin – Village | |||||

| Bukasami | 126 | 61 (48.4) | 65 (51.6) | 0.066 | 17.4007 |

| Bulamogi | 1 | 0 | 1 (100) | ||

| Buwolero | 1 | 0 | 1 (100) | ||

| Iziru TC | 6 | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | ||

| Kigalagala Bupupa | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 | ||

| Magamaga East | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 | ||

| Muguluka East | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 | ||

| Nabitosi | 3 | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | ||

| Nabweru | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 | ||

| Nakitokolo | 4 | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | ||

| Nawandyo | 40 | 31 (77.5) | 9 (22.5) | ||

| Parish | |||||

| Other | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 | 0.013* | 16.1895 |

| Bugomba | 40 | 31 (77.5) | 9 (22.5) | ||

| Bulugo | 4 | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | ||

| Buweera | 1 | 0 | 1 (100) | ||

| Itakaibolu | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 | ||

| Iziru | 136 | 65 (47.8) | 71 (52.2) | ||

| Magamaga | 2 | 2 (100) | 0 | ||

| Sub-county / District | |||||

| Busede | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 | 0.015* | 12.3226 |

| Buwenge | 3 | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | ||

| Other | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 | ||

| Buyengo TC | 140 | 68 (48.6) | 72 (51.4) | ||

| Nawampiti | 40 | 31 (77.5) | 9 (22.5) | ||

| Jinja | 144 | 71 (49.3) | 73 (50.7) | 0.004* | 10.8842 |

| Luuka | 40 | 31 (77.5) | 9 (22.5) | ||

| Other | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 | ||

Table 1. Analysis of the association of sociodemographic characteristics and geographic origin with Aeromonas hydrophila illness

| Food Consumed | Participants (n) | Cases n (%) | No cases n (%) | P-value | Chi-Square (χ²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown fried rice (Pilau) | |||||

| Yes | 75 | 46 (61.3) | 29 (38.7) | 0.411 | 0.6768 |

| No | 110 | 57 (51.8) | 53 (48.2) | ||

| White rice | |||||

| Yes | 31 | 19 (61.3) | 12 (38.7) | 0.490 | 0.4757 |

| No | 154 | 84 (54.5) | 70 (45.5) | ||

| Goat’s meat | |||||

| Yes | 18 | 13 (72.2) | 5 (27.8) | 0.137 | 2.2123 |

| No | 167 | 90 (53.9) | 77 (46.1) | ||

| Rice cooked elsewhere | |||||

| Yes | 25 | 16 (64.0) | 9 (36.0) | 0.368 | 0.8117 |

| No | 160 | 87 (54.4) | 73 (45.6) | ||

| Bovine meat | |||||

| Yes | 30 | 17 (56.7) | 13 (43.3) | 0.905 | 0.0142 |

| No | 155 | 86 (55.5) | 69 (44.5) | ||

| Tea | |||||

| Yes | 11 | 7 (63.6) | 4 (36.4) | 0.584 | 0.3003 |

| No | 174 | 96 (55.2) | 78 (44.8) | ||

| Posho | |||||

| Yes | 11 | 4 (36.4) | 7 (63.6) | 0.184 | 1.76 |

| No | 174 | 99 (56.9) | 75 (43.1) | ||

| Porridge | |||||

| Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 (100) | 0.261 | 1.2629 |

| No | 184 | 103 (56.0) | 81 (44.0) | ||

| Beans | |||||

| Yes | 8 | 2 (25.0) | 6 (75.0) | 0.074 | 3.1884 |

| No | 177 | 101 (57.1) | 76 (42.9) | ||

Table 2. Analysis of the association of the food eaten at the funeral with Aeromonas hydrophila illness

| Food eaten at the funeral | Aeromonas hydrophila (at least two cardinal symptoms) | Total | Attack Rate (AR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| No | 36 | 36 | 72 | 50.0% |

| Yes | 46 | 67 | 113 | 59.29% |

| Total | 82 | 103 | 185 | |

Table 3. Attack rate of Aeromonas hydrophila among funeral attendees

| Food Consumed | Cases n (%) | No cases n (%) | RR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown fried rice (Pilau) | |||||

| Yes | 46 (61.3) | 29 (38.7) | 0.765 | 0.157–1.133 | 0.181 |

| No | 57 (51.8) | 53 (48.2) | 1.00 | Reference | |

| White rice | |||||

| Yes | 19 (61.3) | 12 (38.7) | 0.993 | 0.621–1.587 | 0.977 |

| No | 84 (54.5) | 70 (45.5) | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Goat’s meat | |||||

| Yes | 13 (72.2) | 5 (27.8) | 0.719 | 0.315–1.640 | 0.433 |

| No | 90 (53.9) | 77 (46.1) | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Rice cooked elsewhere | |||||

| Yes | 16 (64.0) | 9 (36.0) | 0.669 | 0.367–1.220 | 0.190 |

| No | 87 (54.4) | 73 (45.6) | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Bovine meat | |||||

| Yes | 17 (56.7) | 13 (43.3) | 1.160 | 0.702 | 0.562 |

| No | 86 (55.5) | 69 (44.5) | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Other food (Tea, Posho, Porridge, Beans) | |||||

| Yes | 13 (41.9) | 18 (58.1) | 1.156 | 0.736–1.815 | 0.530 |

| No | 399 (56.3) | 310 (43.7) | 1.00 | Reference | |

R.R: Risk Ratios

C.I.: Confidence Interval

Table 4. Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis of Food Consumption and A. hydrophila illness

| Critical Control Points (CCP) | Unsafe food handling practices | Hazards – Contamination – Survival – Growth/Toxin | Corrective measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cooking, Serving, Handwashing, Drinking | Open unsecured food cooking places. (Night 12th/Feb/24) | Microbial and toxin contamination. | Closed, secured, and cleaned cooking places. |

| Food handlers reported having GIT illness. (cooked on 12th to 13th/Feb/24) | Aeromonas hydrophila microbial contamination | Individuals with GIT illness should not handle food processes. | |

| Water was supplied from the unsafe Kabakubya stream in Iziru and Nawandyo borehole. | Aeromonas hydrophila microbial contamination | Water should be from a protected source and treated with chlorine. | |

| Serving, Drinking | Fermented cold food (served on 13th/Feb/24 at 8:00 am) | Microbial and toxin contamination, survival, and growth. | Food should be served freshly cooked and hot. |

| 02 food handlers with GIT illness (died). (served on 12th to 13th/Feb/24) | Aeromonas hydrophila contamination | Individuals with GIT illness are not allowed to handle food. | |

| Drinking water from the unsafe Kabakubya stream in Iziru and Nawandyo borehole. | Aeromonas hydrophila contamination, survival, growth | Treat drinking water (chlorine dispensers were not used). | |

| Eating | Water for washing hands from Kabakubya stream and Nawandyo borehole. | Aeromonas hydrophila contamination | Water should be clean and safe. |

| Serving, Eating, Drinking | Eating fermented cold food and Duwa served by those with GIT illness. | Aeromonas hydrophila contamination, survival, growth/toxin | Food should be eaten freshly cooked and hot. |

GIT: Gastrointestinal Tract illness

HACCP: Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points – a science-based, systematic approach used in food safety to identify, evaluate, and control hazards that could affect the safety of food products, ensuring food is safe for consumption by preventing, eliminating, or reducing hazards to acceptable levels.

Table 5. Summary of the hazard analysis and critical control point (HACCP) risk assessment

| Bottlenecks and Enablers | Detection | Notification | Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Timeliness | 3 Days | 0 Days | 11 Days |

| Target met? | 7-day target met? Yes | 1-day target met? Yes | 7-day target met? No |

| Bottlenecks | • Poor healthcare-seeking behaviors • Misconceptions and perceptions of the cause • Limited health facility records | • Lack of sample collection containers • Inadequate labeling of samples, CIFs, and referrals • Poor coordination with the HUB system • Inadequate tracking of samples | • Delay in the release of results • Lack of funds to support DRRT and RPHEOC • Lack of medical supplies (drugs, PPEs, etc.) • Lack of fuel for vehicles • Antimicrobial resistance |

| Root causes | • Limited community engagement (RCCE) • Limited adoption of the One Health approach • Inadequacy of tools | • No training provided to health workers on sample management • Limited coordination of the DLFP and HUB system | • Limited support by IPs for public health emergencies • No budget for DRRTs and RPHEOC for rapid response |

| Enablers | • Availability of trained VHTs • High alert and increased suspicion by health workers • Public–Private Partnership in Health | • Availability of an electronic sample tracking system • Availability of eIDSR system • Availability of HUB system | • Trained DRRT in place • RPHEOC in place • Trained frontline epidemiologists • Implementing partners supporting the initial response |

7-1-7 metric of timeliness: First 7 – detect within 7 days; 1 – notify high public health authorities within 1 day; Last 7 – complete full response within 7 days.

VHT: Village Health Teams (healthcare level one in Uganda)

DRRTs: District Rapid Response Teams

RPHEOC: Regional Public Health Emergency Operations Centre

DLFP: District Laboratory Focal Person

IPs: Implementing Partners

eIDSR: Electronic Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response

Table 6. 7-1-7 Timeliness Intervals, Bottlenecks, and Enablers for A. hydrophila Infection Response

Figures

Keywords

- Aeromonas hydrophila

- Outbreak

- Attack rate

- Public health response

- Uganda

Joseph Oposhia1,2,3,&, Joseph Kungu4, Peter Dyogo Nantamu2,5, Aggrey Bameka2, Pauline Akiror2, Yenusu Mbwire2, Joash Magambo2, Susan Nabadda6, Michael Mulowoza3, Alfred Yayi3, Deborah Aujo3, Gorretti Akol Olupot3, Kenneth Kabaali7, Peter Olupot-Olupot1

1Department of Community Health, Infectious Diseases Field Epidemiology and Biostatistics in Africa (EDCTP-IDEA), Busitema University, Mbale, Uganda, 2District Health Department, Jinja District Local Government, Ministry of Health, Jinja, Uganda, 3Busoga Regional Public Health Emergency Operations Centre (RPHEOC), Jinja Regional Referral Hospital, Ministry of Health, Jinja, Uganda, 4Department of Biosafety and Biosecurity, College of Veterinary Medicine, Animal Resources and Biosecurity, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda, 5School Doctoral Studies, Unicaf University, Zambia, 6Department of National Health Laboratory and Diagnostic Services (NHLDS), Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda, 7Emergency Preparedness and Response Cluster, World Health Organization Uganda Country Office, Kampala, Uganda

&Corresponding author: Joseph Oposhia, Department of Community Health, Infectious Diseases Field Epidemiology and Biostatistics in Africa (EDCTP-IDEA), Busitema University, Mbale, Uganda, Email: oposia@live.com ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5574-4547

Received: 15 Jan 2025, Accepted: 01 Feb 2026, Published: 04 Feb 2026

Domain: Outbreak Investigation

Keywords: Aeromonas hydrophila, outbreak, attack rate, public health response, Uganda

©Joseph Oposhia et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Joseph Oposhia et al., Investigation of the 2024 Aeromonas hydrophila outbreak in Jinja and Luuka, Uganda: A mixed-methods approach. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2026; 9(1):22. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00025

Abstract

Introduction: Aeromonas infections are an emerging global public health challenge due to their complex pathogenicity and diverse virulence factors. These infections can lead to various conditions in humans, such as gastroenteritis, wound infections, and septicaemia. On February 12, 2024, an outbreak of Aeromonas hydrophila infection in Jinja and Luuka, Uganda, resulted in cases of abdominal pain, diarrhoea, vomiting, and death. This study described the epidemiology of the outbreak and the public health response.

Methods: To investigate the outbreak and evaluate the epidemiology and public health response, a mixed-methods study was conducted using secondary data involving 185 individuals. Confirmed cases were identified through positive culture results from gastric aspirates or stool samples. Suspected and probable cases were defined by at least two symptoms, including abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhoea, history of exposure, and an epidemiological link to a confirmed case or outbreak cluster occurring between February 12 and 27, 2024. The study also included secondary laboratory investigations, food safety assessments, and an evaluation of timeliness using the 7-1-7 metric. Data analysis was performed using STATA-17.

Results: Among 185 individuals investigated, 54.1% were female, the mean age was 23.9 ±18.7years, 103 Aeromonas hydrophila cases were identified, resulting in an attack rate of 55.7%(103/185), including one laboratory-confirmed case. Cases were younger than non-cases (22.1 vs. 26.3 years). The outbreak lasted five days (12–16 February 2024), peaked on 14 February, and had an incubation period of 33–38 hours, indicating a common-source exposure. Eight deaths occurred (case fatality rate: 7.8%). Geographical clustering of cases was observed, with high attack rates in Iziru (48%) and Bugomba (78%) parishes, respectively. Funeral food exposure showed an attributable risk of 9.3/100 and an attributable fraction of 15.7%. A. hydrophila was detected in gastric aspirate and water samples, implicating contaminated water and ill food handlers. Relapse occurred in 30.1% of cases.

Conclusion: The outbreak of Aeromonas hydrophila was rapid, geographically clustered, and linked to contaminated water and ill food handlers, with funeral food exposure contributing to the outbreak. High attack, relapse, and fatality rates highlight the need for timely water safety interventions, improved food hygiene, and strengthened outbreak detection and response to prevent future occurrences.

Introduction

Aeromonas hydrophila, a gram-negative, facultative anaerobe, thrives in freshwater and brackish environments and can cause infections ranging from gastroenteritis to septicaemia [1, 2]. A. hydrophila is increasingly recognized as an emerging public health threat, particularly in low-income countries where poor water quality amplifies its impact [3-5]. Severe infections, such as bacteremia, can result in high case fatality rates ranging from 30% to 70% [5]. Recent reports suggest that the prevalence of Aeromonas is higher in children with diarrhoea in Africa, with an estimated rate of 8.8%, attributed to poor hygiene and sanitation conditions [5]

In February 2024, an outbreak of foodborne illness linked to A. hydrophila occurred in Jinja and Luuka Districts, Uganda (unpublished Busoga Regional Public Health Emergency Operations Centre (RPHEOC) situation reports 2024). Despite its clinical and epidemiological significance, data on A. hydrophila in Uganda remain scarce, with limited research focus, hindering effective prevention and response efforts. The outbreak underscored the bacterium’s impact on public health, the economy, and access to social services. Furthermore, its resilience to antimicrobial agents complicates treatment, especially in vulnerable populations.

This study employed a mixed-methods approach to investigate the clinical aspects, epidemiological characteristics, environmental factors, and public health response associated with the outbreak. The findings aimed to bridge the knowledge gap on A. hydrophila infections and inform targeted interventions to mitigate future outbreaks in similar settings.

Methods

Study design

The study employed a mixed-methods approach using secondary data, integrating both quantitative and qualitative analysis methods. It incorporated epidemiological principles, Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) principles, and the 7-1-7 metric of timeliness to investigate the outbreak, assess the distribution and presentation of cases, identify vehicles and modes of transmission, and evaluate the effectiveness of the public health response.

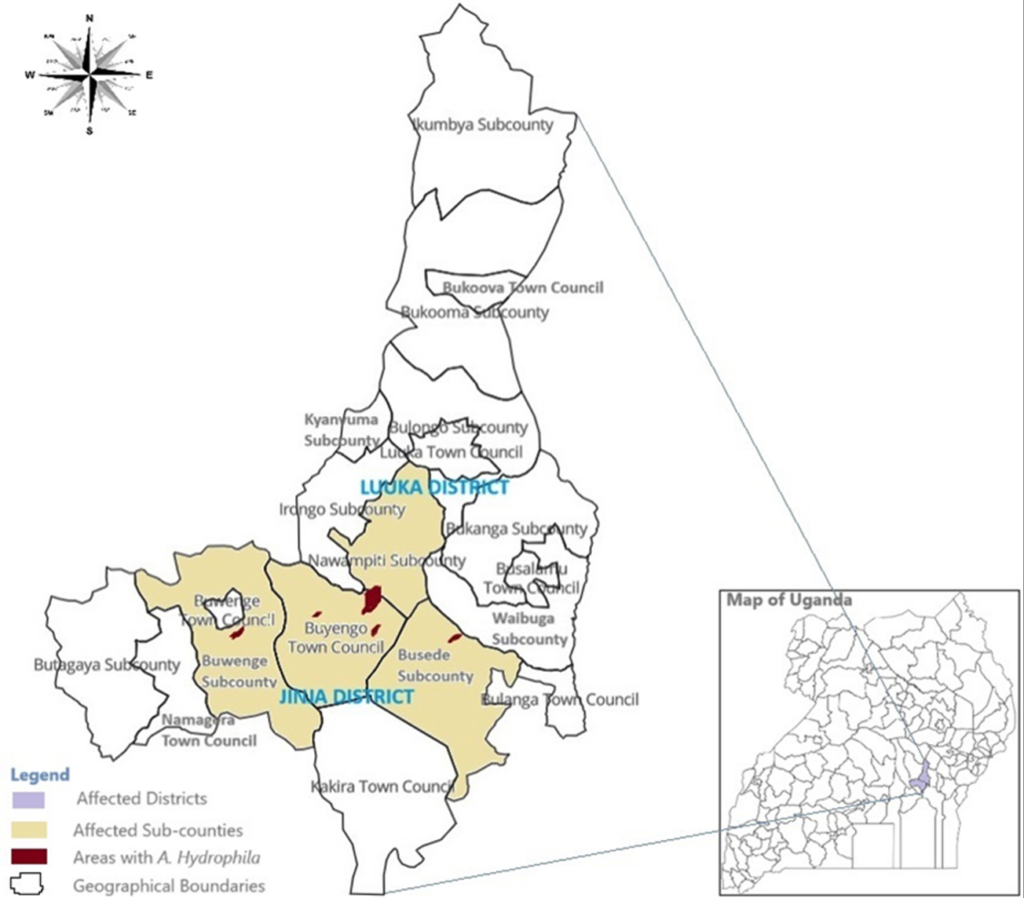

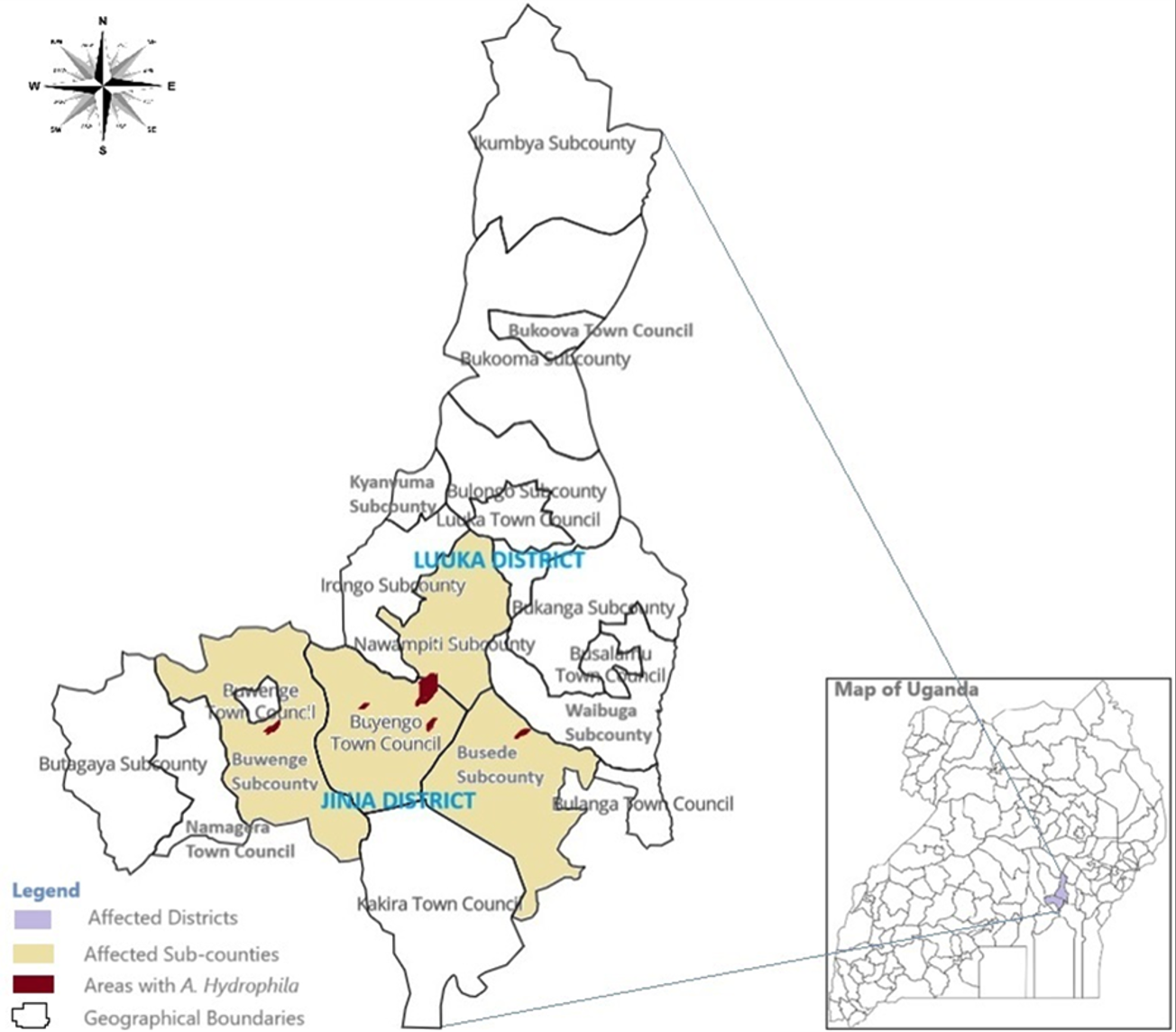

Study area

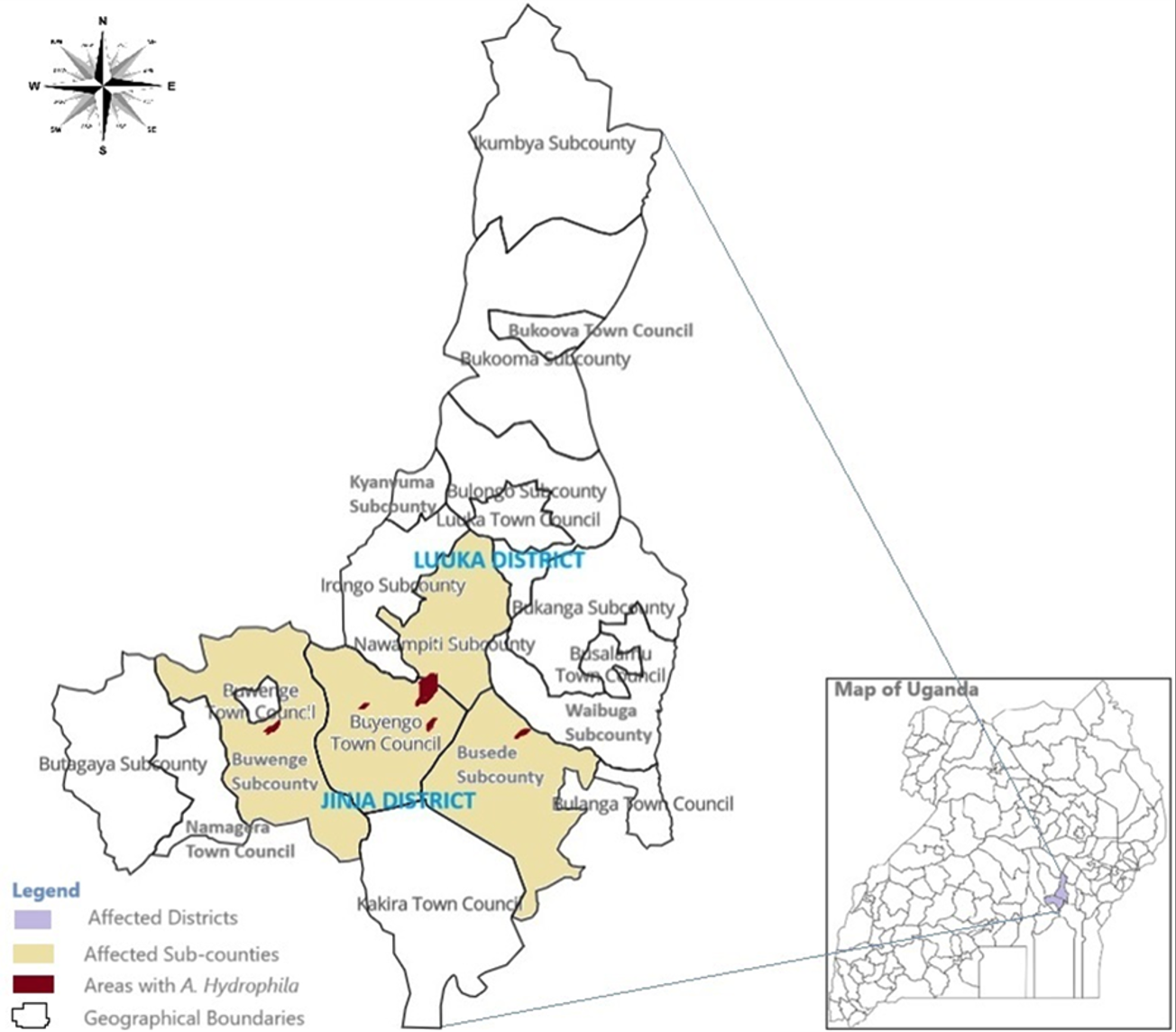

Jinja and Luuka Districts are in Eastern Uganda, along Lake Victoria’s northern shores near the River Nile’s source, about 80 km east of Kampala. Jinja is an industrial and tourism hub, while Luuka, a rural district northeast of Jinja, relies on smallholder agriculture for livelihood. The districts are bordered by Kamuli and Buyende Districts to the north, Buikwe District to the west, Iganga and Kaliro Districts to the east, and Mayuge District to the south. Their proximity to Lake Victoria and the Nile increases the risk of waterborne diseases.

The study focused on all diagnosed cases of Aeromonas hydrophila infection in Jinja and Luuka. The individuals investigated included those who had travelled from various geographical areas in Jinja and Luuka for funeral rites and other reasons before the outbreak. The cases originated from eight villages across six parishes in five sub-counties within the districts of Jinja and Luuka. In Jinja District, the cases were distributed across six villages: Bukasami (61 cases, 59.2%), Iziru Trading Centre (3 cases, 2.9%), Nakitokolo (3 cases, 2.9%), Kigalagala Bupupa (1 case, 1%), Magamaga East (1 case, 1%), Muguluka East (1 case, 1%), and Nabitosi (1 case, 1%). In contrast, Luuka District had cases originating from one village, Nawandyo (31 cases, 30.1%). The most affected sub-counties include Buyengo (68 cases, 66%) and Nawampiti (31 cases, 30.1%) (Figure 1).

Sample size determination

The sample size was primarily determined by the availability and completeness of relevant existing data, encompassing all diagnosed, suspected, and probable cases identified from secondary data during the Jinja and Luuka outbreak (February 12–27, 2024). Public health reports, laboratory results, investigation records, and relevant contacts (e.g., family members or event participants) were also taken into consideration. This approach was appropriate due to the rarity of Aeromonas hydrophila infection and time constraints.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study included records of diagnosed, suspected, or probable cases, reports on the February 2024 outbreak in Jinja and Luuka, and individuals exposed during key events or relevant contacts. Incomplete or unclear records were excluded.

Data collection and analyses

Clinical Investigation

We conducted a retrospective investigation and review of records and community reports. A case definition for Aeromonas hydrophila infections in an outbreak setting typically follows WHO or CDC guidelines, incorporating clinical, epidemiological, and laboratory criteria to classify cases as suspected, probable, or confirmed as follows: [6, 7]

Suspected case: An individual presenting with acute gastroenteritis characterized by one or more of the following symptoms: watery or bloody diarrhoea, abdominal pain or cramps, nausea and/or vomiting, fever, AND history of consuming contaminated food or water, or close contact with a confirmed case between February 12th and 27th, 2024.

Probable case: A suspected case with an epidemiological link to a confirmed case, outbreak cluster, or known exposure source (e.g., consumption of contaminated food or water, poor sanitation, or exposure to untreated water sources).

Confirmed case: A case with laboratory-confirmed isolation of A. hydrophila from a clinical specimen through culture-based identification from stool/ gastric aspirate, blood, or wound specimen, molecular testing (Polymerase Chain Reaction or sequencing), and antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Epidemiology investigation

The study utilised secondary data by examining records from case investigation forms, line lists, surveillance reports, and situation reports to gather information on potential sources of exposure for participants. Cases of Aeromonas hydrophila infection were identified based on records detailing the time of onset and clinical presentation. An epidemic curve was constructed, and patient presentations and outcomes were summarised using frequencies and percentages, presented in tables and graphs. Statistical analyses were conducted to identify the vehicles and modes of transmission, with p-values, confidence intervals, and risk ratios assessed at the 95% confidence level. Bivariate analysis was performed using the χ² test, and statistically significant variables were further analysed through multivariate logistic regression using STATA 17.0.

Laboratory investigation

We reviewed laboratory results from local and regional facilities using non-specialised methods for clinical and environmental examinations. Additionally, we analysed secondary data from laboratory results of 124 samples previously submitted to four national reference laboratories for specialized diagnosis. These included 106 clinical samples (blood, stool, vomitus, and gastric aspirate), four food samples from the funeral rite, one piece of spongy mattress vomited on by a victim, and 13 water samples from various sources used by the affected communities. The laboratory test results, including toxicology and infectious agent analyses from staining, culture, biochemical, and molecular tests, were summarized in a table.

Environmental investigation

The Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) approach was applied by reviewing available data from the funeral to systematically identify and evaluate potential food safety hazards and controls throughout the food preparation and handling process. This involved hazard identification, critical control points (CCPs) identification, risk assessment, developing corrective measures, and summarising findings.

Public health response investigation

Using secondary data, we applied the 7-1-7 metric to evaluate the timeliness and effectiveness of outbreak detection, notification, and response measures. This process involved verifying reports, incorporating stakeholder perspectives, and reviewing meeting records. We assessed the 7-1-7 intervals by determining whether the outbreak was detected within 7 days of its initial emergence, whether public health authorities were notified within 1 day of detection, and whether a full response was initiated within 7 days of notification. Additionally, we identified bottlenecks and enablers that influenced overall performance. The findings were summarised in relevant tables.

Ethical considerations

The study adhered to confidentiality and data protection standards, with a waiver of consent granted due to anonymized secondary data. The data was archived at the Regional Public Health Emergency Operations Centre (RHEOC) at Jinja Regional Referral Hospital, and the cases and deceased individuals were identified using acronyms of their names. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board of the Jinja Regional Referral Hospital for the outbreak investigation (Ref No: JRRH-REC 580/2024).

Results

In this study, 185 individuals were selected, including 84 males (45.41%) and 101 females (54.05%). The mean age of the participants was 23.9 years, with a standard deviation of 18.7 years. These participants were from diverse geographical locations in the Jinja and Luuka districts.

Distribution of Aeromonas hydrophila cases

Distribution of cases by person

There were 102 suspected and probable cases, along with one confirmed case. The mean age of the cases was 22.1 years (95% confidence interval [CI]: (18.51-25.76), whereas the mean age of the non-cases was 26.3 years (95%CI: 22.26-30.40). Among the identified cases, educational attainment was recorded for 141 participants. Of these, 14 of 21 participants with secondary education (66.7%), 52 of 110 with primary education (47.3%), and 7 of 10 with no formal education (70.0%) were cases; no cases were identified among the two participants with tertiary education. Marital status was available for 142 participants, among whom cases occurred in 41 of 81 participants who were never married (50.6%), 26 of 55 who were married (47.2%), 3 of 3 who were divorced (100%), and 2 of 3 who were widowed (66.7%). Sex was recorded for 103 participants; of these, 59 of 101 females (58.4%) and 44 of 84 males (52.4%) were cases (Table 1).

Distribution of cases by time of onset

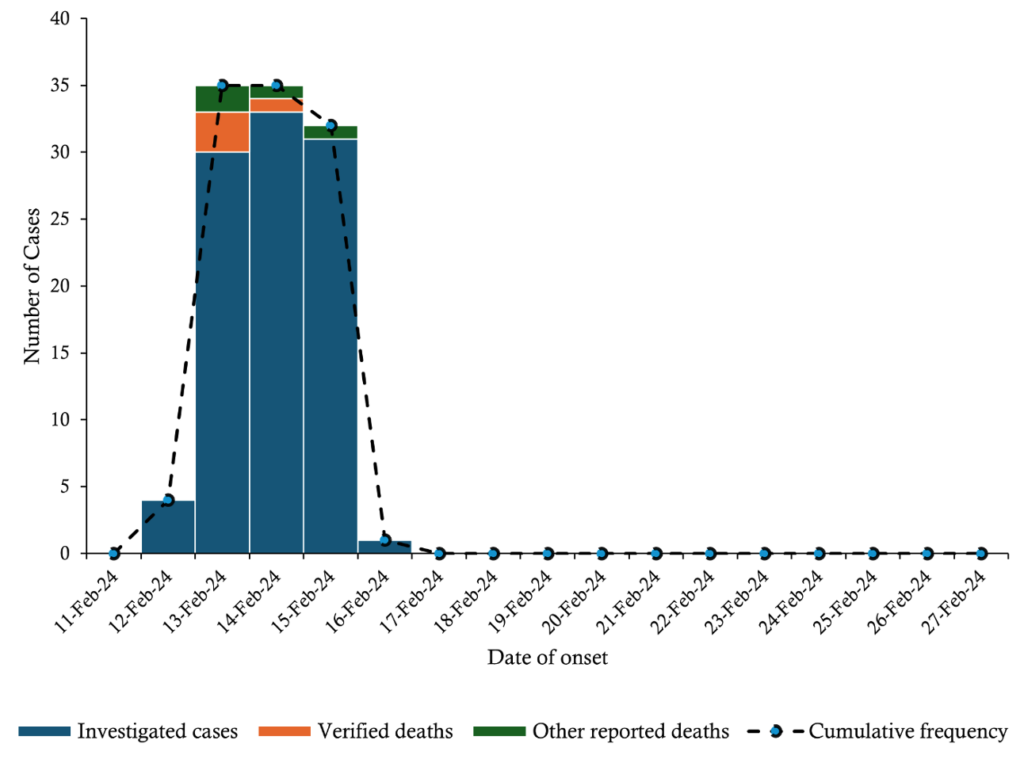

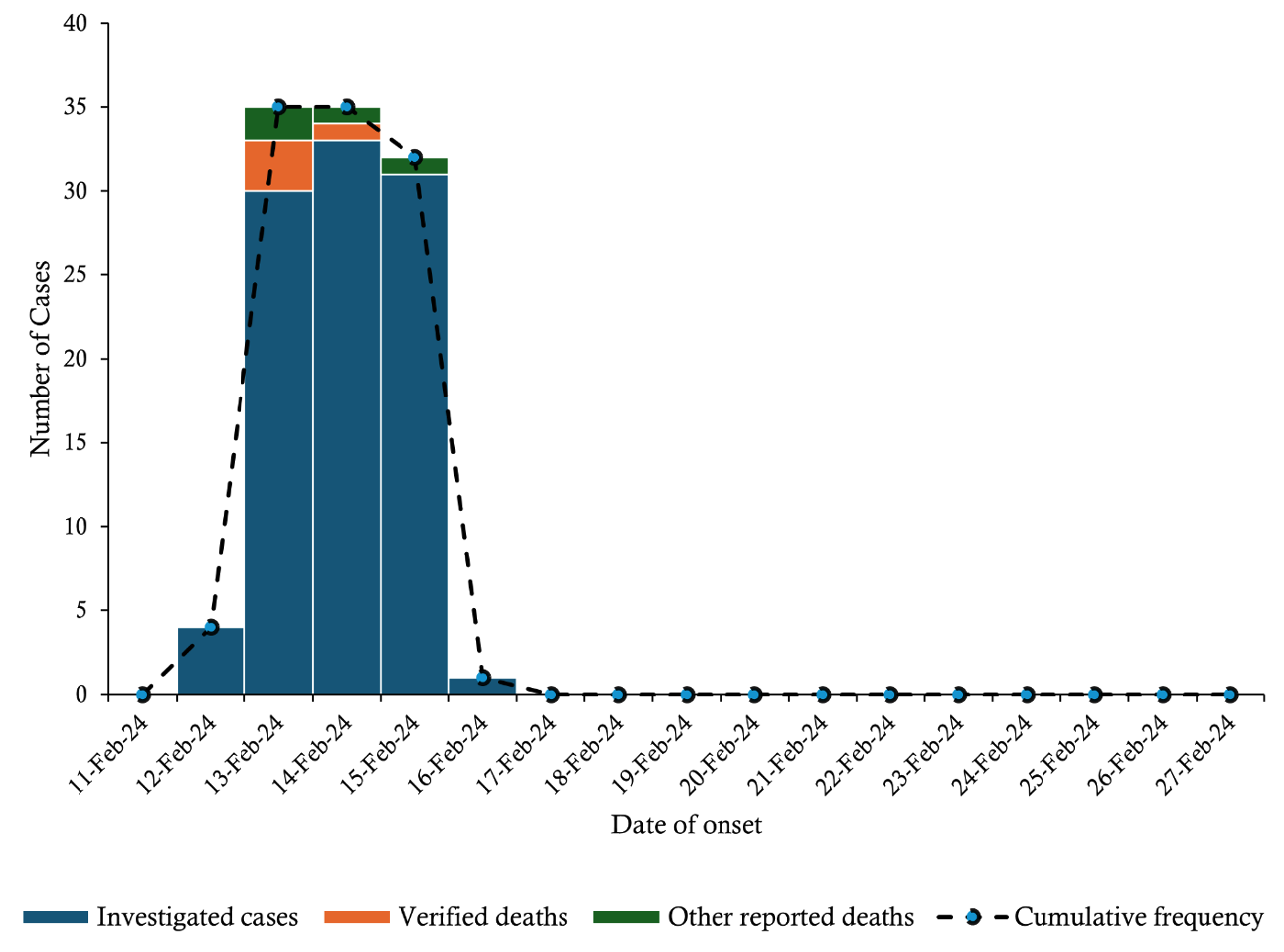

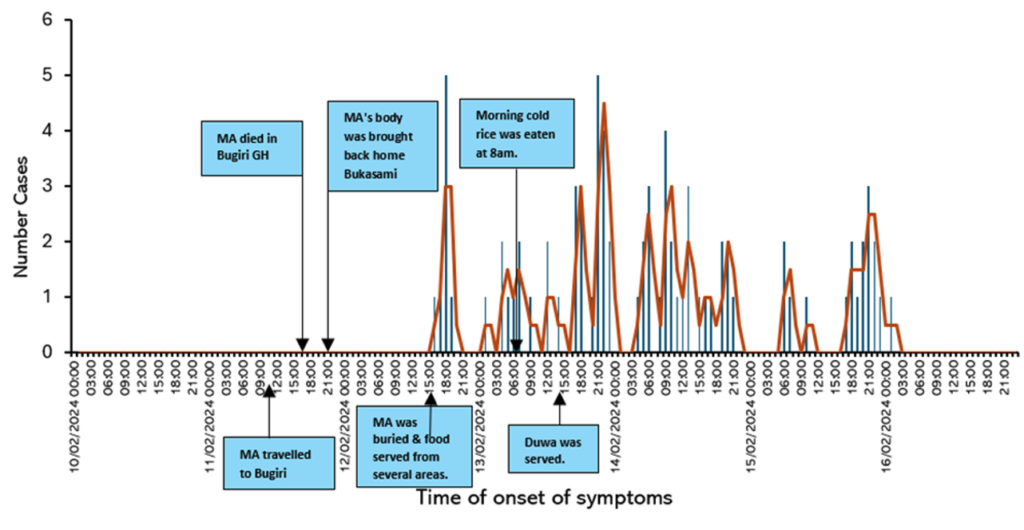

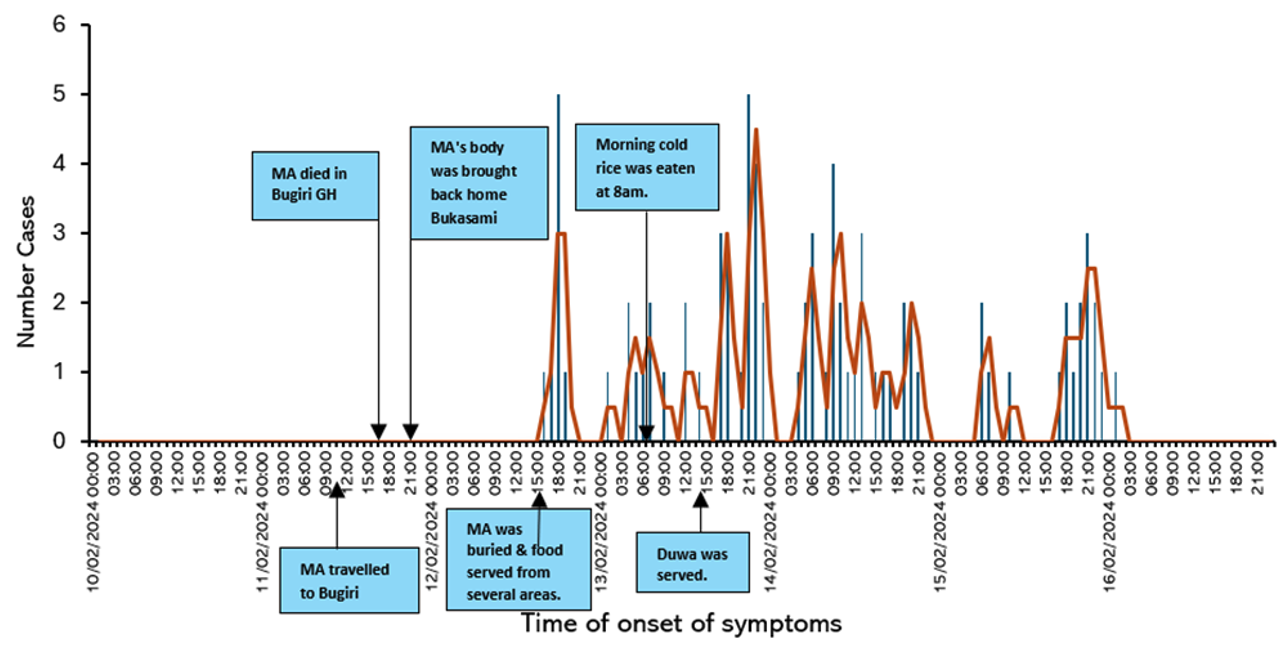

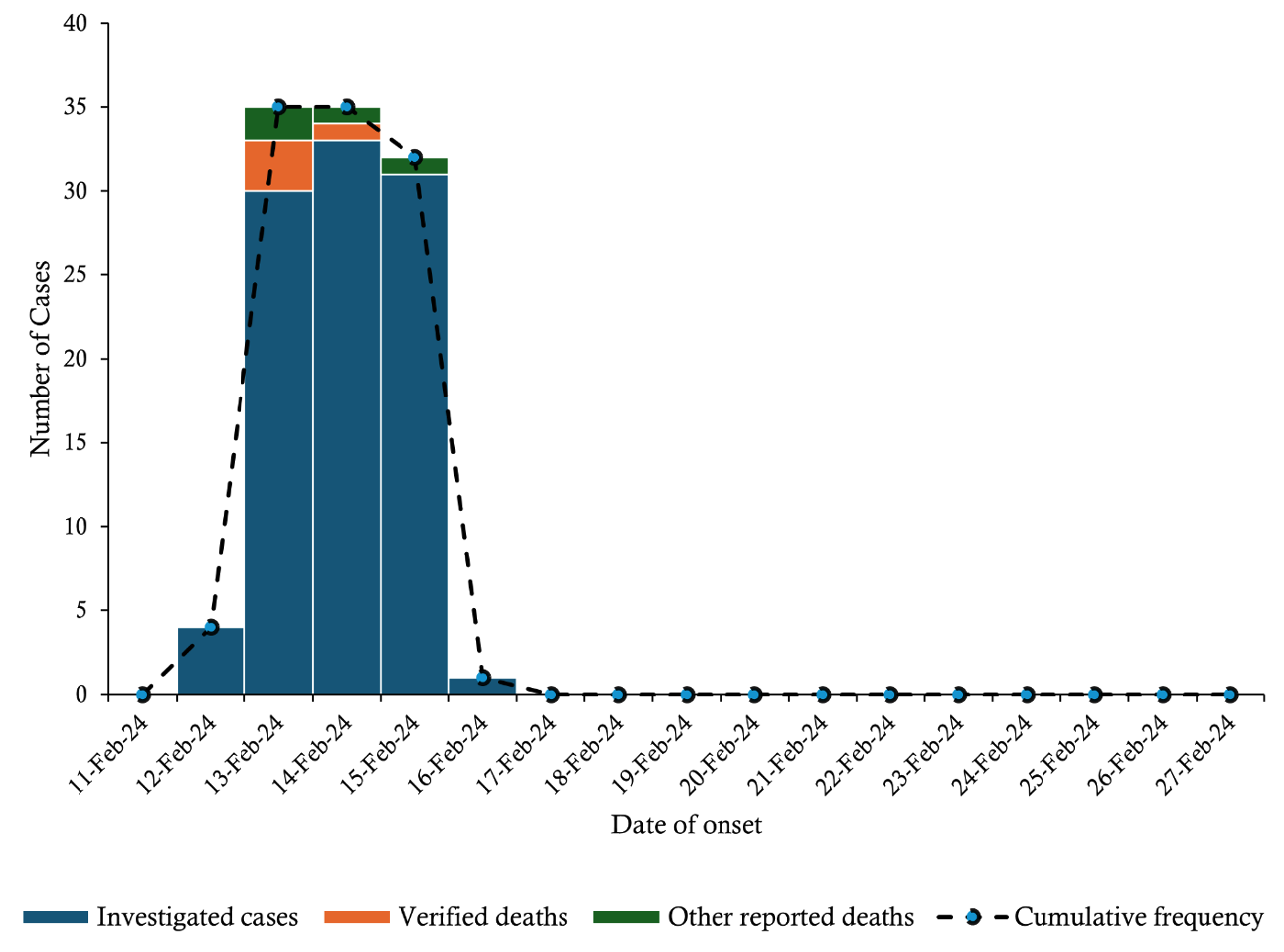

The outbreak began on February 12 with 4 cases, surged to a peak of 34 on February 14, and declined sharply to 1 case by February 16, suggesting a common source of exposure.

Three deaths on February 13 and one on February 14 coincided with the early cases, likely indicating severe initial infections. Four additional deaths between February 13 and 15 suggest the progression of severe cases. The high fatality rate warrants an urgent assessment of disease severity and healthcare response. The incubation period was estimated to be 33–38 hours (Figure 2).

Presentation and outcomes of patients with Aeromonas hydrophila

Symptom presentation and incubation period

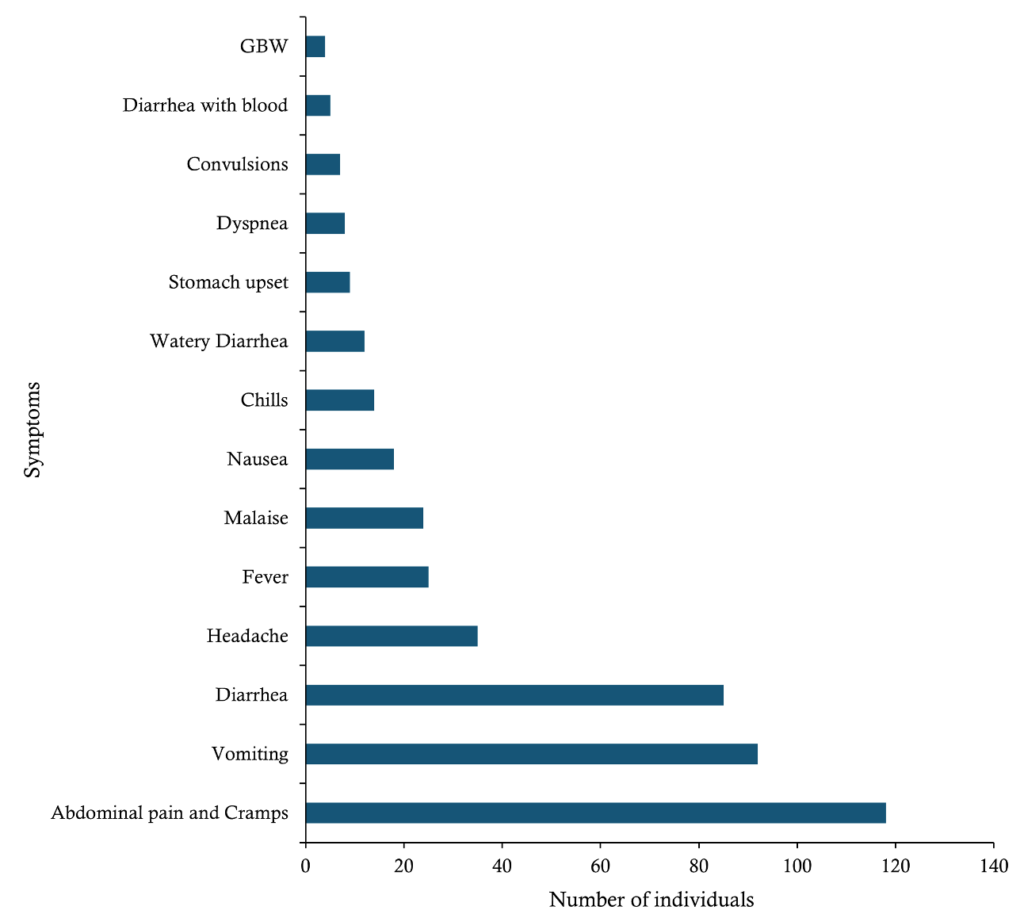

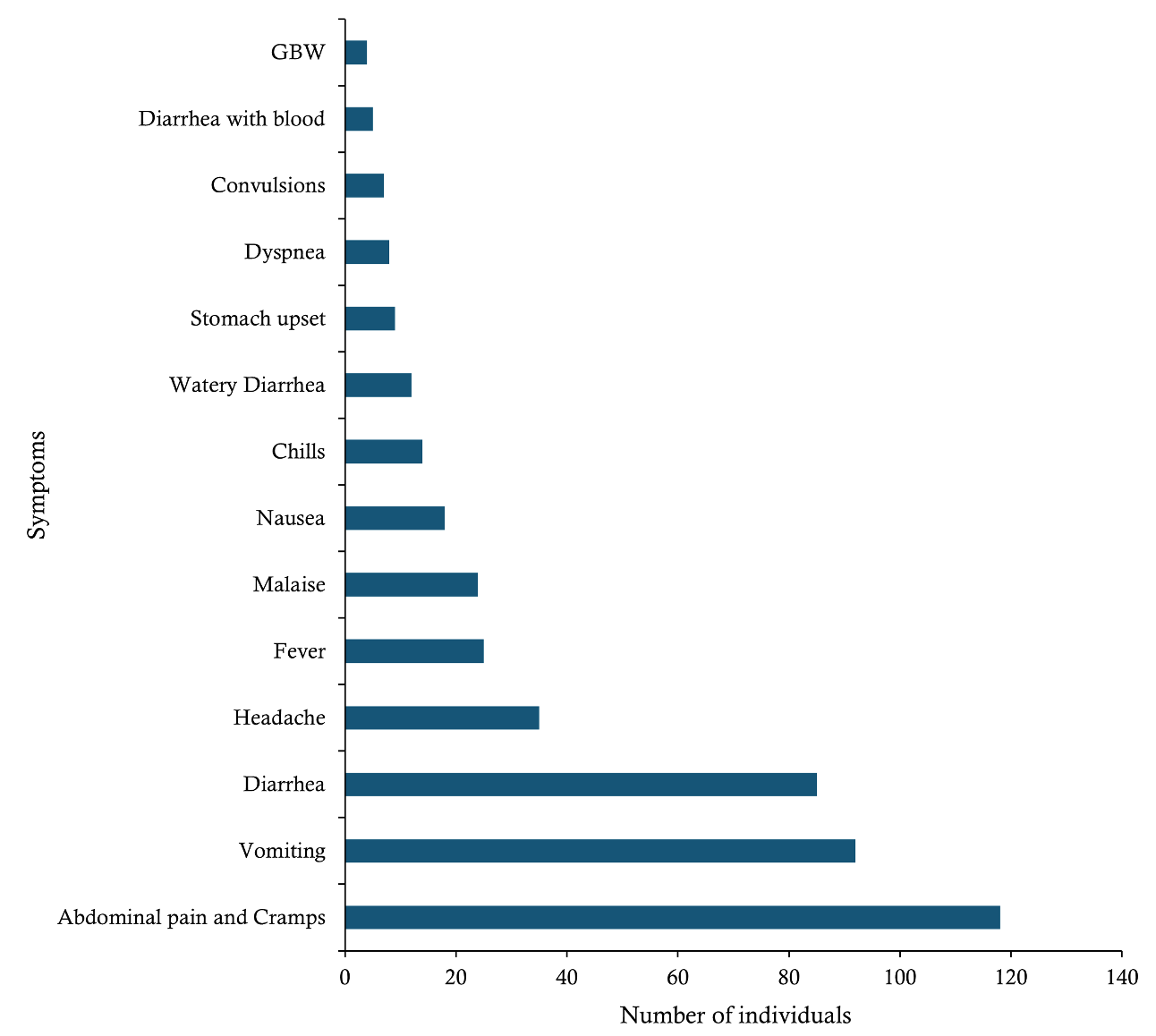

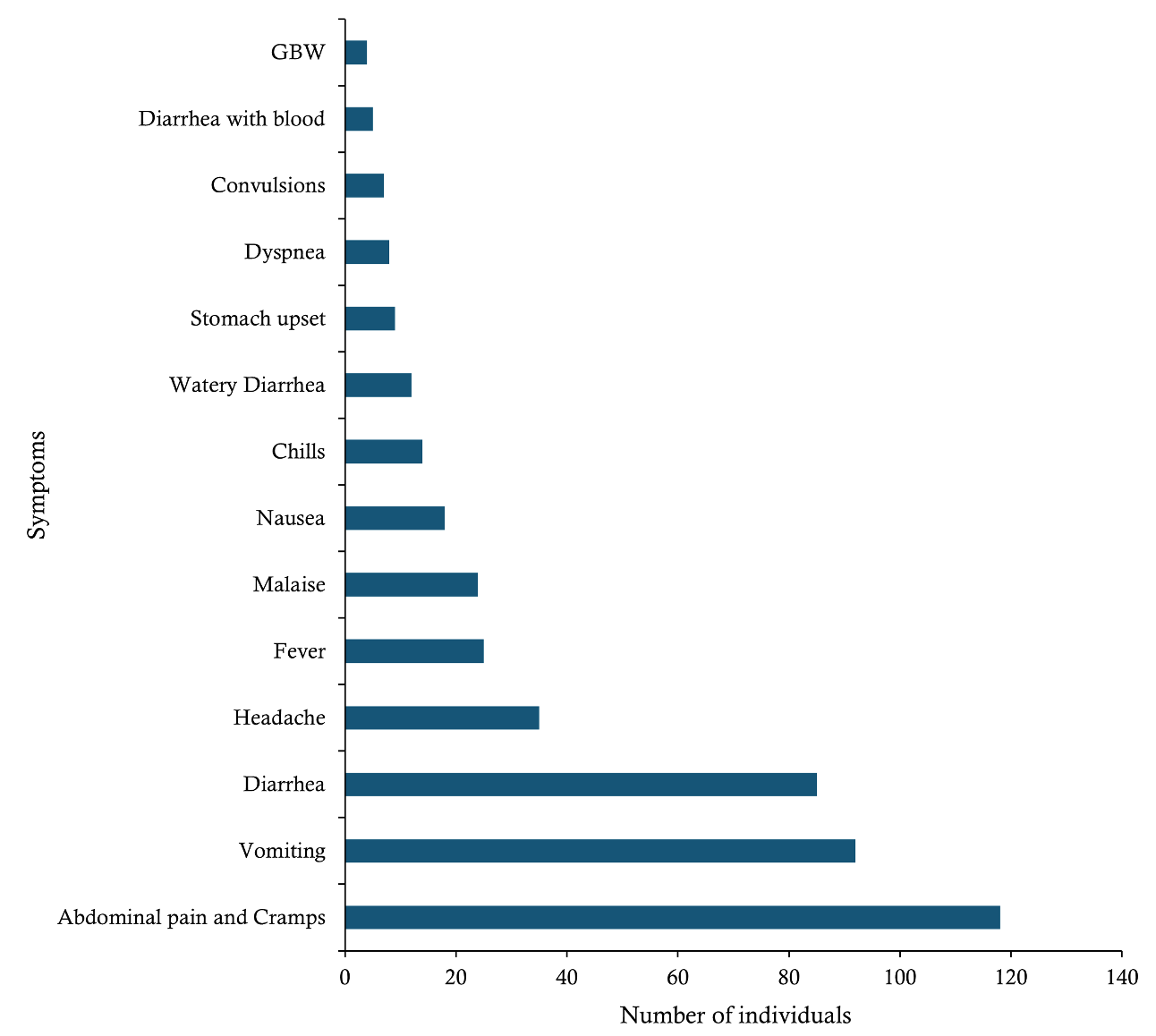

The onset of cases spanned 5 days, from February 12 to February 16, 2024, with an incubation period of 33–38 hours. The most common symptoms among probable cases of Aeromonas infection were abdominal pain and cramps (118 cases, 81.4%), vomiting (92 cases, 63.4%), and diarrhoea (85 cases, 58.6%). Other symptoms included headache (35 cases, 24.1%), fever (25 cases, 17.2%), malaise (24 cases, 16.6%), nausea (18 cases, 12.5%), chills (14 cases, 9.7%), watery diarrhoea (12 cases, 8.3%), and stomach upset (9 cases, 6.2%). The least reported symptoms were dyspnoea (8 cases, 5.5%), convulsions (7 cases, 4.8%), diarrhoea with blood (5 cases, 3.4%), and generalised body weakness (4 cases, 2.8%) (Figure 3).

Health outcome of cases

In this outbreak, 103 cases were identified from the 185 records reviewed, including one laboratory-confirmed case. Eight deaths were reported, yielding a case fatality rate (CFR) of 7.8% (8/103), all of which were linked to the funeral in Bukasami, Jinja. The study examined four of these deaths: a 4-year-old boy and a 10-year-old girl from Nawandyo Village in Luuka District; a 24-year-old male who served food at the Bukasami funeral; and an adult female over 50 years of age who attended both the Bukasami funerals of MA and of a 24-year-old male. She died in Jinja and was buried in Nabirumba, Kamuli. Additionally, four other deaths were reported, with at least two cardinal symptoms.

The relapse of cases occurred in 31 out of 103 individuals (30.1%), particularly among those from Bugomba Parish in Luuka District. Patients were discharged with prescriptions, hoping they would complete their treatment, especially for medications unavailable at the admitting hospital. This led to health outcomes such as delayed recovery and additional deaths. The duration of Aeromonas hydrophila illness lasted up to 21 days among individuals who experienced a relapse of the infection.

Predisposing factors for Aeromonas hydrophila

Sociodemographic factors

Statistical tests indicated no significant association between the sociodemographic factors (age, sex, education level, marital status) and Aeromonas hydrophila illness at a 95% confidence level (Table 1).

Geographical distribution by area of origin

Marked geographical clustering of cases was observed, with particularly high attack rates in Iziru Parish (48%; 136 cases) and Bugomba Parish (78%; 40 cases) of Buyengo and Nawampiti Sub-counties, respectively. At the sub-county level, similarly elevated attack rates were recorded in Buyengo (49%; 140 cases) in Jinja and Nawampiti (78%; 40 cases) in Luuka district, indicating localised concentration of cases within these administrative areas (Table 1a).

Food consumption at the funeral

Attack rates and attributable risk measures

Among the 103 cases, 102 were probable, and one was confirmed, resulting in an attack rate of 55.7% (103/185). The attack rate was higher among funeral attendees (59.3%, 67/113) than those who did not (50.0%, 36/72), suggesting a possible link between food consumption at the event and the outbreak (Table 2 and Table 3). Eating food at the funeral was associated with an attributable risk of 9.3 cases per 100 exposed and an attributable fraction of 15.7%.

Epidemiological investigation

The most commonly consumed food served at the funeral was Pilau brown rice (75 cases, 66.4%), followed by bovine meat (30 cases, 26.5%), white rice (31 cases, 27.4%), other rice (25 cases, 22.1%), goat meat (18 cases, 15.96%), tea (11 cases, 9.7%), posho (11 cases, 9.7%), beans (8 cases, 7.1%), and porridge (1 case, 1%). The χ² analysis showed no significant association (p > 0.05) between Aeromonas hydrophila illness and the food served at the funeral (Table 2). Multivariate logistic regression analysis found no statistically significant link between Aeromonas hydrophila illness and food served at the funeral (Table 4). However, many cases occurred among funeral attendees who ate specific foods, including goat meat (72%), separately cooked rice (64%), tea (64%), brown fried rice (pilau) (61%), and white rice (61%) (Table 4).

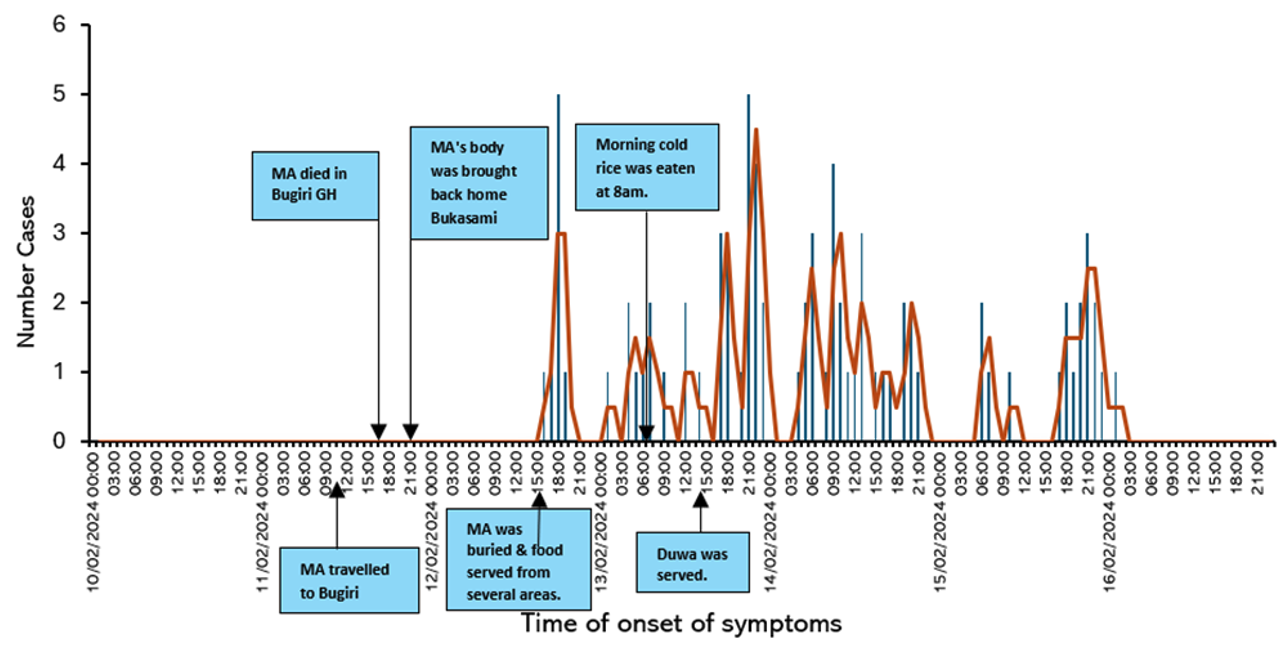

Hazard analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) investigation

We identified several probable sources of contamination and infection, including food handlers who experienced gastrointestinal illness, suspected due to Aeromonas hydrophila. Among them were two food handlers (MF and a friend) who served food at the funeral and later died of likely Aeromonas hydrophila illness. Other sources included water supplied by hired motorcycle riders (renowned as Boda-boda riders) from the Kabakubya Stream in Iziru parish, Jinja district, water collected from a contaminated borehole in Nawandyo Village Luuka district, whose water samples tested positive for Aeromonas hydrophila isolates, unsecured cooking areas, and fermented cold food served in the morning (Table 5 and Figure 4).

Laboratory investigation

Water quality test results from three boreholes and piped water systems, analysed by local and regional laboratories, showed optimal levels of mineral salts and no E. coli, which is considered an indicator organism for contamination. Additionally, local laboratory test results for hospitalised individuals found no indicative cause of gastroenteritis.

One hundred twenty-four laboratory test results of four national specialised reference laboratories were analysed, covering 106 clinical samples (blood, stool, urine, vomitus, and gastric aspirate) and 20 environmental samples (food and water). Aeromonas hydrophila was detected by the National Reference Laboratory in gastric aspirate samples (n = 2) for cases, stream water from Kabakubya, Iziru Parish, Jinja district, and borehole water from Bugomba Parish (Nawandyo Village), Luuka district (n = 2) for the environment. This was confirmed through culture, biochemical, and molecular tests. However, all water samples tested negative for E. coli, while other clinical and environmental samples tested negative for pathogens and toxic substances (Table 6). This suggests that E. coli isolates alone are not a reliable indicator for assessing water quality.

Public health response to Aeromonas hydrophila outbreak

Assessment of the timeliness of response: The first case occurred on February 12, 2024, and was detected on February 15, 2024, meeting the seven-day detection target. The district health office and regional public health emergency operations centre (RPHEOC) notified the Ministry of Health and initiated a response within one day, including clinical management, sample collection, and investigation. Full response measures began 11 days after notification, following the confirmation of A. hydrophila on February 26, 2024, and continued with water sample results on March 15, 2024, 30 days after notification (Table 7).

Assessment of bottlenecks and enablers: Several bottlenecks were identified in detection, notification, and response, including poor healthcare-seeking behaviour, misconceptions, inadequate sample collection and labelling, poor coordination with the HUB system, delays in result release, limited financial resources, fuel shortages, lack of medical supplies, and antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Despite these challenges, key enablers included trained village health teams (VHT), increased suspicion among health workers, public-private partnerships (PPPH), electronic systems for sample tracking and disease reporting (HUB and eIDSR), trained district and RPHEOC personnel, frontline epidemiologists, and support from implementing partners (Table 7).

Discussion

Epidemiological Investigations

The significant rise in cases and deaths, as shown by the epidemic curve, suggests a common source of exposure was responsible for the surge in cases typical of an epidemic. The outbreak exhibited a peak period of cases, reflecting geographical and temporal clustering triggered by a specific event or source. Semwal observed that Aeromonas hydrophila, though emerging, can cause sporadic outbreaks globally, resulting in significant negative impacts on those affected [1]. The 2015 cholera outbreak in Haiti exhibited substantial clustering of cases in specific geographic areas and timeframes, with a peak in case numbers occurring after the disease’s initial introduction [8]. Worldwide, Aeromonas are among the leading causes of diarrhoea among children, with a high case fatality rate of up to 30% to 70% in those with disseminated gastrointestinal bacteremia [5].

The lack of association with socio-demographic factors suggests that they have no significant impact on infection likelihood, indicating that environmental conditions or exposure sources are more influential. Similarly, studies reveal that Aeromonas hydrophila can affect individuals across various demographics, which is particularly challenging for those with compromised immune systems [4].

In this outbreak, marked geographical clustering of cases in specific parishes and their sub-counties in the districts suggests a link to shared broader regional factors and environmental issues potentially related to a nearby large sugar factory’s pollution. Studies show that Aeromonas hydrophila is spread through contaminated water or food, as well as contact with contaminated surfaces or objects [9] [10]. Poor water quality, marked by high nitrogen, phosphorus, chlorophyll, and ammonium levels, combined with factory pollution and oxygen depletion, fosters Aeromonas hydrophila proliferation, driven by human activities and climate change [1, 11]. Managing and preventing outbreaks should prioritise regional factors like environmental conditions and shared resources over demographic factors, as Kamal’s study indicates that demographic factors are less relevant for Aeromonas hydrophila outbreaks [12]. Public health interventions should prioritise improving sanitation, water quality, food safety, and regional surveillance, while further research is needed to explore community practices and factors in villages with no significant associations.

Aeromonas infections typically present with gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, cramps, vomiting, and diarrhoea, consistent with acute gastroenteritis, as seen in this outbreak. Although less common, systemic symptoms such as headache, fever, and malaise can occur, possibly indicating more severe or widespread infection. Rare symptoms like dyspnoea, convulsions, and bloody diarrhoea may suggest atypical cases or complications and may require further investigation. Zhao and Alexander’s research indicates that Aeromonas hydrophila typically causes gastrointestinal issues, such as diarrhoea, abdominal pain, nausea, fever, and occasionally bloody stools, especially in immunocompromised individuals [2]. In rare cases, Aeromonas hydrophila can cause respiratory infections with symptoms like coughing and difficulty breathing. During a foodborne outbreak at a college in Xingyi City, China, affecting 349 students, the primary symptoms were abdominal pain (80%), headache (55%), vomiting (29%), fever (18%), and diarrhoea, with 14% experiencing acute bloody and mucous diarrhoea lasting 2-3 days [13]. In severe cases or among individuals with a weakened immune system, Aeromonas hydrophila infection can lead to bloodstream infections (sepsis), which can cause fever, chills, low blood pressure, rapid heart rate, confusion, and organ failure [14, 15]. A. hydrophila frequently affects the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) more than any other site does and is responsible for 2.0% of travellers’ diarrhoea [16]. Not everyone exposed to Aeromonas hydrophila will show symptoms, and symptom severity can vary based on factors like immune status and existing health conditions. It’s important to seek medical attention if severe or persistent symptoms occur. Understanding how the infection presents, its virulence factors, and how it spreads is essential for effective prevention, diagnosis, and treatment [6].

The Aeromonas hydrophila infection outbreak provides a comprehensive view of the infection’s severity and progression. The fatalities linked to the funeral in Jinja underscore the urgent need for rapid response measures in similar outbreaks. The high relapse rate suggests treatment gaps due to self-medication and raises concerns about potential antimicrobial resistance among isolates, though further laboratory investigations are needed to confirm this hypothesis. This suggests severe infection and challenges in recovery, potentially due to inadequate initial treatment, reinfection, environmental pathogen persistence, or self-medication. Aeromonas hydrophila is known to possess a variety of virulence factors that contribute to its pathogenicity in both humans and animals [1]. Key virulence factors of Aeromonas hydrophila include adhesins, extracellular enzymes, cytokines, enterotoxins, flagella, biofilm formation, inherent antibiotic resistance, and quorum-sensing systems, which enable the bacteria to colonize, invade, and damage host tissues, leading to infections of varying severity [4].

Environmental investigations

Although food consumption showed no direct statistical significance, the attack rate was higher among funeral attendees, with an attributable risk indicating increased cases due to food consumption at the funeral. However, HACCP analysis suggested the risk of contamination through unsafe food handling and water supplies. This indicates that infection may have occurred through alternative transmission routes, non-food sources, such as water, person-to-person contact, or environmental exposure. The HACCP findings indicate conditions that could lead to contamination (e.g., improper storage, handling), but they do not confirm the actual presence of pathogens. The high attack rate among funeral attendees and the involvement of infected food handlers suggest that food preparation may have played a role in the outbreak. The attributable fraction indicates that approximately one in six cases among exposed individuals could have been prevented. The findings similarly underscore the role of ill workers in foodborne illness outbreaks in retail food establishments, emphasizing the need for strict health and safety protocols for food handlers [17, 18, 19]. The WHO highlights the importance of considering various contamination sources in foodborne outbreaks, noting that environmental contamination and indirect transmission routes can significantly contribute, even without direct links [17, 18, 20].

Laboratory investigations

The laboratory investigation confirmed other sources of contamination as indicated by HACCP, including water from the Kabakubya Stream in Iziru and the borehole in Nawandyo, with their parishes being statistically linked to an increased risk of infection in the districts. HACCP analysis identified unsafe food handling, fermented cold food, contaminated water supplies, and unsecured cooking areas as potential contributors to the outbreak, highlighting factors beyond those captured by statistical analysis. The outbreak’s spread may involve multiple factors, including indirect contamination from water or other sources, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive investigation and approach to manage water quality, food handling, and environmental conditions. Aeromonas hydrophila, a bacterium from aquatic environments, infects humans and animals through contaminated water, food, or surfaces, with its prevalence influenced by factors like water quality, temperature, host species, antibiotic use, and environmental stressors [9, 17, 21].

Challenges in response and surveillance

This outbreak investigation highlights that effective outbreak management depends on prompt response and timely notification. Key challenges include logistical barriers and antimicrobial resistance, while enablers such as well-trained health teams and strong partnerships play a crucial role. Improving outbreak management requires reducing testing delays, streamlining processes, enhancing coordination, and ensuring faster turnaround times for critical diagnostics. Effective management also fosters proactive healthcare-seeking behaviours, optimises logistics, strengthens coordination, increases funding, addresses antimicrobial resistance, and builds on existing capacities [19]. Leveraging the enablers will revitalise prompt full response.

This study was limited by its narrow geographical scope, partial assessment of antimicrobial resistance, and the absence of analyses on pathogenic mechanisms, genetic diversity, survivor analysis, and geospatial distribution. These limitations may restrict generalization, insights into the findings, and preclude a more detailed characterization of the pathogen.

Conclusion

While no direct statistical association was found between food consumption and Aeromonas hydrophila infection, the higher attack rate among funeral attendees and unsafe food handling practices suggest a possible role in transmission. Contaminated water and ill food handlers were the most likely sources of infection, emphasising the need for strengthened water safety and food hygiene measures. The following recommendations are suggested to mitigate future infections within similar community settings.

- Future efforts should improve healthcare-seeking behaviours, engage communities, optimise resources, and leverage existing strengths to prevent and manage similar outbreaks.

- Regular water quality monitoring in high-risk areas should be implemented to detect and mitigate future contaminations

- Training programs for food handlers should be established to reduce the risk of foodborne outbreaks

- Enhanced laboratory capacity is needed to detect and assess antimicrobial resistance patterns in Aeromonas infections

The outbreak underscores the urgent need for improved public health infrastructure, surveillance, and intervention strategies. A multi-sectoral approach addressing environmental contamination, food and water safety, and antimicrobial resistance is critical to reducing future risks.

Further research is essential to understand the factors influencing Aeromonas hydrophila outbreaks. Investigating why some communities remained unaffected could provide insights into protective factors. Examining antimicrobial resistance patterns is crucial for guiding effective treatment strategies. Additionally, studying the pathogen’s persistence in environmental reservoirs could aid in preventing future outbreaks

What is already known about the topic

- Aeromonas hydrophila is an emerging pathogen causing various illnesses, with limited data from Uganda, highlighting the need for further research on its prevalence and impact

- Poor water and sanitation infrastructure, along with limited awareness of food and waterborne pathogens, contribute to Aeromonas outbreaks, especially in vulnerable communities

- In immunocompromised patients, hydrophila infections can lead to a more severe and potentially life-threatening condition

- Limited surveillance and diagnostic capabilities in Uganda have led to underreporting and delayed responses to Aeromonas hydrophila outbreaks

What this study adds

- This study offers insights into the February 2024 outbreak in Jinja and Luuka, Uganda, focusing on transmission dynamics, affected populations, and contributing factors

- It highlights the critical role of unsafe food handling and contaminated water sources in the spread of Aeromonas hydrophila

- The study uses the WHO 7-1-7 metric to evaluate the timeliness and effectiveness of Uganda’s public health response, highlighting key bottlenecks and enablers

- The study uses a comprehensive mixed-methods approach, combining secondary data, stakeholder perspectives, laboratory results, and HACCP assessments to provide a holistic view of the outbreak’s clinical, environmental, and public health aspects

- The study fills a gap in research on Aeromonas hydrophila infections in Uganda, providing valuable evidence to inform policies and practices for improving food and water safety in similar settings

Authors´ contributions

JO, PDN, and JMK conceived and designed the study, collected samples, collected data, did laboratory analysis of sample results, analysed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, and drafted and approved submission of the final manuscript. MM, AY, AB, PA, SK, YM, JMI, DA, and GAO collected samples, collected data, analysed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, drafted, and approved submission of the final manuscript. LN, CK, SN, and POO conceived and designed the study, analysed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, and drafted and approved the submission of the final manuscript.

| Socio-demographic | Participants (n) | Cases n (%) | No cases n (%) | P-value | Chi-square (χ²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 84 | 44 (52.4) | 40 (47.6) | 0.411 | 0.6768 |

| Female | 101 | 59 (58.4) | 42 (41.6) | ||

| Education | |||||

| None | 10 | 7 (70.0) | 3 (30.0) | 0.102 | 6.2004 |

| Primary | 110 | 52 (47.3) | 58 (52.7) | ||

| Secondary | 21 | 14 (66.7) | 7 (33.3) | ||

| Tertiary or higher | 2 | 0 | 2 (100) | ||

| Marital status | |||||

| Divorced | 3 | 3 (100) | 0 | 0.323 | 3.4818 |

| Married | 55 | 26 (47.3) | 29 (52.7) | ||

| Never married | 81 | 41 (50.6) | 40 (49.4) | ||

| Widowed | 3 | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | ||

| Occupation | |||||

| Business | 5 | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | 0.147 | 12.102 |

| Political leader | 1 | 0 | 1 (100) | ||

| Child | 2 | 2 (100) | 0 | ||

| Health worker | 2 | 0 | 2 (100) | ||

| Housewife | 1 | 0 | 1 (100) | ||

| Mechanic | 1 | 0 | 1 (100) | ||

| Peasant | 66 | 39 (59.1) | 27 (40.9) | ||

| Pupil | 63 | 28 (44.4) | 35 (55.6) | ||

| Student | 2 | 2 (100) | 0 | ||

| Geographical Area of Origin – Village | |||||

| Bukasami | 126 | 61 (48.4) | 65 (51.6) | 0.066 | 17.4007 |

| Bulamogi | 1 | 0 | 1 (100) | ||

| Buwolero | 1 | 0 | 1 (100) | ||

| Iziru TC | 6 | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | ||

| Kigalagala Bupupa | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 | ||

| Magamaga East | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 | ||

| Muguluka East | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 | ||

| Nabitosi | 3 | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | ||

| Nabweru | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 | ||

| Nakitokolo | 4 | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | ||

| Nawandyo | 40 | 31 (77.5) | 9 (22.5) | ||

| Parish | |||||

| Other | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 | 0.013* | 16.1895 |

| Bugomba | 40 | 31 (77.5) | 9 (22.5) | ||

| Bulugo | 4 | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | ||

| Buweera | 1 | 0 | 1 (100) | ||

| Itakaibolu | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 | ||

| Iziru | 136 | 65 (47.8) | 71 (52.2) | ||

| Magamaga | 2 | 2 (100) | 0 | ||

| Sub-county / District | |||||

| Busede | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 | 0.015* | 12.3226 |

| Buwenge | 3 | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | ||

| Other | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 | ||

| Buyengo TC | 140 | 68 (48.6) | 72 (51.4) | ||

| Nawampiti | 40 | 31 (77.5) | 9 (22.5) | ||

| Jinja | 144 | 71 (49.3) | 73 (50.7) | 0.004* | 10.8842 |

| Luuka | 40 | 31 (77.5) | 9 (22.5) | ||

| Other | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 | ||

| Food Consumed | Participants (n) | Cases n (%) | No cases n (%) | P-value | Chi-Square (χ²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown fried rice (Pilau) | |||||

| Yes | 75 | 46 (61.3) | 29 (38.7) | 0.411 | 0.6768 |

| No | 110 | 57 (51.8) | 53 (48.2) | ||

| White rice | |||||

| Yes | 31 | 19 (61.3) | 12 (38.7) | 0.490 | 0.4757 |

| No | 154 | 84 (54.5) | 70 (45.5) | ||

| Goat’s meat | |||||

| Yes | 18 | 13 (72.2) | 5 (27.8) | 0.137 | 2.2123 |

| No | 167 | 90 (53.9) | 77 (46.1) | ||

| Rice cooked elsewhere | |||||

| Yes | 25 | 16 (64.0) | 9 (36.0) | 0.368 | 0.8117 |

| No | 160 | 87 (54.4) | 73 (45.6) | ||

| Bovine meat | |||||

| Yes | 30 | 17 (56.7) | 13 (43.3) | 0.905 | 0.0142 |

| No | 155 | 86 (55.5) | 69 (44.5) | ||

| Tea | |||||

| Yes | 11 | 7 (63.6) | 4 (36.4) | 0.584 | 0.3003 |

| No | 174 | 96 (55.2) | 78 (44.8) | ||

| Posho | |||||

| Yes | 11 | 4 (36.4) | 7 (63.6) | 0.184 | 1.76 |

| No | 174 | 99 (56.9) | 75 (43.1) | ||

| Porridge | |||||

| Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 (100) | 0.261 | 1.2629 |

| No | 184 | 103 (56.0) | 81 (44.0) | ||

| Beans | |||||

| Yes | 8 | 2 (25.0) | 6 (75.0) | 0.074 | 3.1884 |

| No | 177 | 101 (57.1) | 76 (42.9) | ||

| Food eaten at the funeral | Aeromonas hydrophila (at least two cardinal symptoms) | Total | Attack Rate (AR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| No | 36 | 36 | 72 | 50.0% |

| Yes | 46 | 67 | 113 | 59.29% |

| Total | 82 | 103 | 185 | |

| Food Consumed | Cases n (%) | No cases n (%) | RR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown fried rice (Pilau) | |||||

| Yes | 46 (61.3) | 29 (38.7) | 0.765 | 0.157–1.133 | 0.181 |

| No | 57 (51.8) | 53 (48.2) | 1.00 | Reference | |

| White rice | |||||

| Yes | 19 (61.3) | 12 (38.7) | 0.993 | 0.621–1.587 | 0.977 |

| No | 84 (54.5) | 70 (45.5) | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Goat’s meat | |||||

| Yes | 13 (72.2) | 5 (27.8) | 0.719 | 0.315–1.640 | 0.433 |

| No | 90 (53.9) | 77 (46.1) | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Rice cooked elsewhere | |||||

| Yes | 16 (64.0) | 9 (36.0) | 0.669 | 0.367–1.220 | 0.190 |

| No | 87 (54.4) | 73 (45.6) | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Bovine meat | |||||

| Yes | 17 (56.7) | 13 (43.3) | 1.160 | 0.702 | 0.562 |

| No | 86 (55.5) | 69 (44.5) | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Other food (Tea, Posho, Porridge, Beans) | |||||

| Yes | 13 (41.9) | 18 (58.1) | 1.156 | 0.736–1.815 | 0.530 |

| No | 399 (56.3) | 310 (43.7) | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Critical Control Points (CCP) | Unsafe food handling practices | Hazards – Contamination – Survival – Growth/Toxin | Corrective measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cooking, Serving, Handwashing, Drinking | Open unsecured food cooking places. (Night 12th/Feb/24) | Microbial and toxin contamination. | Closed, secured, and cleaned cooking places. |

| Food handlers reported having GIT illness. (cooked on 12th to 13th/Feb/24) | Aeromonas hydrophila microbial contamination | Individuals with GIT illness should not handle food processes. | |

| Water was supplied from the unsafe Kabakubya stream in Iziru and Nawandyo borehole. | Aeromonas hydrophila microbial contamination | Water should be from a protected source and treated with chlorine. | |

| Serving, Drinking | Fermented cold food (served on 13th/Feb/24 at 8:00 am) | Microbial and toxin contamination, survival, and growth. | Food should be served freshly cooked and hot. |

| 02 food handlers with GIT illness (died). (served on 12th to 13th/Feb/24) | Aeromonas hydrophila contamination | Individuals with GIT illness are not allowed to handle food. | |

| Drinking water from the unsafe Kabakubya stream in Iziru and Nawandyo borehole. | Aeromonas hydrophila contamination, survival, growth | Treat drinking water (chlorine dispensers were not used). | |

| Eating | Water for washing hands from Kabakubya stream and Nawandyo borehole. | Aeromonas hydrophila contamination | Water should be clean and safe. |

| Serving, Eating, Drinking | Eating fermented cold food and Duwa served by those with GIT illness. | Aeromonas hydrophila contamination, survival, growth/toxin | Food should be eaten freshly cooked and hot. |

| Sn | Sample Type | No. | Test Performed | Method Used | Results | Reference Range | Interpretation | Lab |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Blood | 53 | LFTS / RFTS / CBC / C&S | Elevated (14) | Infection | Ref lab 1 & 2 | ||

| 2 | Blood | 18 | PCR for viral pathogens | RT-PCR | No VHF | Negative | Negative | Nat. Ref. lab 3 |

| 3 | Urine | 5 | GCMS/MS | GCMS/MS | No toxic substance | Negative | Negative | Nat. Ref. lab 5 |

| 4 | Blood | 10 | GCMS/MS | GCMS/MS | No toxic substance | Negative | Negative | Nat. Ref. lab 5 |

| 5 | Food (Rice sample) | 2 | GCMS/MS | GCMS/MS | No toxic substance | Negative | Negative | Nat. Ref. lab 5 |

| 6 | Gastric aspirate | 2 | Appearance, staining, culture, GCMS/MS | Culture, biochemical, and molecular (MALDI-TOF), GCMS/MS | Aeromonas species; No toxic substance | Aeromonas hydrophila | Positive | Nat. Ref. lab 5 & 6 |

| 7 | Stool | 8 | Culture for bacterial pathogens | Culture and sensitivity | No Salmonella / Shigella / Enteropathogenic E. coli | Negative | Negative | Nat. Ref. lab 6 |

| 8 | Blood | 11 | PCR for Anthrax | RT-PCR | No Bacillus | Negative | Negative | Nat. Ref. lab 4 |

| 9 | Vomitus-soiled spongy mattress | 1 | GCMS/MS | GCMS/MS | No chemical | Negative | Negative | Nat. Ref. lab 5 |

| 10 | Water | 13 | C/S, biochemical, and molecular | Culture, biochemical, and molecular (MALDI-TOF) | Aeromonas hydrophila; No Salmonella / Shigella / Vibrio / Enteropathogenic E. coli | Aeromonas hydrophila (2 samples) | Positive | Nat. Ref. lab 6 |

| 11 | Food | 1 | Culture for bacterial pathogen | Culture and sensitivity | No pathogen isolated | Negative | Negative | Nat. Ref. lab 6 |

| 12 | Stool | 90 | Stool analysis | Parasites | No parasite | Negative | Negative | Ref. lab 1 |

Ref lab 1: General Hospital Laboratories;

Ref lab 2: Regional Referral Hospital Laboratory;

Nat. Ref. lab 3: National Reference Viral Laboratory;

Nat. Ref. lab 4: National Reference Laboratory for Anthrax testing;

Nat. Ref. lab 5: National Reference Laboratory for Toxicology tests;

Nat. Ref. lab 6: National Reference Laboratory for Microbiology tests.

MALDI-TOF: Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight mass spectrometry, used for rapid microbial identification based on protein spectra.

RT-PCR: Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction.

GCMS/MS: Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry.

C/S: Culture and Sensitivity (or Susceptibility).

| Bottlenecks and Enablers | Detection | Notification | Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Timeliness | 3 Days | 0 Days | 11 Days |

| Target met? | 7-day target met? Yes | 1-day target met? Yes | 7-day target met? No |

| Bottlenecks |

|

|

|

| Root causes |

|

|

|

| Enablers |

|

|

|

References

- Semwal A, Kumar A, Kumar N. A review on pathogenicity of Aeromonas hydrophila and their mitigation through medicinal herbs in aquaculture [Internet]. Heliyon. 2023 Mar [cited 2026 Feb 4];9(3):e14088. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2405844023012951 doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14088.

- Zhao Y, Alexander J. Aeromonas hydrophila infection in an immunocompromised host [Internet]. Cureus. 2021 Dec 30 [cited 2026 Feb 4]; Available from: https://www.cureus.com/articles/78248-aeromonas-hydrophilia-infection-in-an-immunocompromised-host doi:10.7759/cureus.20834.

- Yuwono C, Wehrhahn MC, Liu F, Zhang L. Enteric Aeromonas infection: a common enteric bacterial infection with a novel infection pattern detected in an Australian population with gastroenteritis [Internet]. Microbiol Spectr. 2023 Jun 28 [cited 2026 Feb 4];11(4):e00286-23. Available from: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/spectrum.00286-23 doi:10.1128/spectrum.00286-23.

- Fernández-Bravo A, Figueras MJ. An update on the genus Aeromonas: taxonomy, epidemiology, and pathogenicity [Internet]. Microorganisms. 2020 Jan 17 [cited 2026 Feb 4];8(1):129. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2607/8/1/129 doi:10.3390/microorganisms8010129.

- Sadeghi H, Alizadeh A, Vafaie M, Maleki MR, Khoei SG. An estimation of global Aeromonas infection prevalence in children with diarrhoea: a systematic review and meta-analysis [Internet]. BMC Pediatr. 2023 May 22 [cited 2026 Feb 4];23(1):254. Available from: https://bmcpediatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12887-023-04081-3 doi:10.1186/s12887-023-04081-3.

- Kaki R. A retrospective study of Aeromonas hydrophila infections at a university tertiary hospital in Saudi Arabia [Internet]. BMC Infect Dis. 2023 Oct 9 [cited 2026 Feb 4];23(1):671. Available from: https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-023-08660-8 doi:10.1186/s12879-023-08660-8.

- World Health Organization. Strengthening surveillance of and response to foodborne diseases: a practical manual. Stage 1: using indicator- and event-based surveillance to detect foodborne events [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2017 Nov 17 [cited 2026 Feb 4]. 127 p. Available from: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/891d15ca-c33e-4c4c-8aab-21376ed4f133/content.

- Griffiths K, Moise K, Piarroux M, Gaudart J, Beaulieu S, Bulit G, Marseille JP, Jasmin PM, Namphy PC, Henrys JH, Piarroux R, Rebaudet S. Delineating and analyzing locality-level determinants of cholera, Haiti [Internet]. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021 Jan [cited 2026 Feb 4];27(1):170-81. Available from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/27/1/19-1787_article.htm doi:10.3201/eid2701.191787.

- Bhowmick UD, Bhattacharjee S. Bacteriological, clinical and virulence aspects of Aeromonas-associated diseases in humans [Internet]. Pol J Microbiol. 2018 Jun 30 [cited 2026 Feb 4];67(2):137-50. Available from: https://www.sciendo.com/article/10.21307/pjm-2018-020 doi:10.21307/pjm-2018-020.

- Hoel S, Vadstein O, Jakobsen AN. The significance of mesophilic Aeromonas spp. in minimally processed ready-to-eat seafood [Internet]. Microorganisms. 2019 Mar 23 [cited 2026 Feb 4];7(3):91. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2607/7/3/91 doi:10.3390/microorganisms7030091.

- Grabowska K, Bukowska A, Kaliński T, Kiersztyn B, Siuda W, Chróst RJ. Presence and identification of Legionella and Aeromonas spp. in the Great Masurian Lakes system in the context of eutrophication: Legionella and Aeromonas spp. in the Great Masurian Lakes system [Internet]. J Limnol. 2020 [cited 2026 Feb 4];79(1). Available from: https://www.jlimnol.it/jlimnol/article/view/jlimnol.2019.1924 doi:10.4081/jlimnol.2019.1924.

- Kamal MM, Tewabe T, Tsheten T, Hossain SZ. Individual- and community-level factors associated with diarrhea in children younger than age 5 years in Bangladesh: evidence from the 2014 Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey [Internet]. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2022 [cited 2026 Feb 4];97:100686. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0011393X2200025X doi:10.1016/j.curtheres.2022.100686.

- Zhang Q, Shi GQ, Tiang GP, Zou ZT, Yao GH, Zeng G. A foodborne outbreak of Aeromonas hydrophila in a college, Xingyi City, Guizhou, China, 2012 [Internet]. WPSAR. 2012 Dec 31 [cited 2026 Feb 4];3(4):39-43. Available from: http://ojs.wpro.who.int/ojs/index.php/wpsar/article/view/173/202 doi:10.5365/wpsar.2012.3.4.018.

- Tsujimoto Y, Kanzawa Y, Seto H, Nakajima T, Ishimaru N, Waki T, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis and sepsis caused by Aeromonas hydrophila [Internet]. Le Infezioni in Medicina. 2019 Dec [cited 2026 Feb 4];27(4):429-435. Available from: https://www.infezmed.it/media/journal/Vol_27_4_2019_11.pdf.

- Yumoto T, Ichiba S, Umei N, Morisada S, Tsukahara K, Sato K, Ugawa T, Ujike Y. Septic shock due to Aeromonas hydrophila bacteremia in a patient with alcoholic liver cirrhosis: a case report [Internet]. J Med Case Reports. 2014 Dec 3 [cited 2026 Feb 4];8(1):402. Available from: https://jmedicalcasereports.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1752-1947-8-402 doi:10.1186/1752-1947-8-402.

- Patil SM, Hilker ED. Aeromonas hydrophila community-acquired bacterial pneumonia with septic shock in a chronic lymphocytic leukemia patient due to absolute neutropenia and lymphopenia [Internet]. Cureus. 2022 Mar 20 [cited 2026 Feb 4]; Available from: https://www.cureus.com/articles/91282-aeromonas-hydrophila-community-acquired-bacterial-pneumonia-with-septic-shock-in-a-chronic-lymphocytic-leukemia-patient-due-to-absolute-neutropenia-and-lymphopenia doi:10.7759/cureus.23345.

- International Association for Food Protection. Procedures to investigate waterborne illness. 3rd ed. Cham (Switzerland): Springer International Publishing; 2016. 153 p.

- World Health Organization. Strengthening surveillance of and response to foodborne diseases: stage two manual: strengthening indicator-based surveillance [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2025 Dec 12 [cited 2026 Feb 4]. 201 p. Available from: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/7da6f240-620e-4624-a4a1-19b67f37fda4/content.

- Lipcsei LE, Brown LG, Coleman EW, Kramer A, Masters M, Wittry BC, Reed K, Radke VJ. Foodborne illness outbreaks at retail establishments — National Environmental Assessment Reporting System, 16 state and local health departments, 2014–2016 [Internet]. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2019 Feb 22 [cited 2026 Feb 4];68(1):1-20. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/ss/ss6801a1.htm?s_cid=ss6801a1_w.

- Elbehiry A, Abalkhail A, Marzouk E, Elmanssury AE, Almuzaini AM, Alfheeaid H, Alshahrani MT, Huraysh N, Ibrahem M, Alzaben F, Alanazi F, Alzaben M, Anagreyyah SA, Bayameen AM, Draz A, Abu-Okail A. An overview of the public health challenges in diagnosing and controlling human foodborne pathogens [Internet]. Vaccines. 2023 Mar 24 [cited 2026 Feb 4];11(4):725. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/11/4/725 doi:10.3390/vaccines11040725.

- Sheikh HI, Nordin B, Paharuddin N, Liew HJ, Fadhlina A, Abdulrazzak LA, Jalal KCA, Musa N. Virulence factors and mechanisms of Aeromonas hydrophila infection in catfish Siluriformes: a review and bibliometric analysis [Internet]. Desalin Water Treat. 2023 Dec [cited 2026 Feb 4];315:538-47. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1944398624107497 doi:10.5004/dwt.2023.30019.