Research | Open Access | Volume 9 (1): Article 12 | Published: 19 Jan 2026

Factors predicting fatality among healthcare workers infected with Ebola in the Democratic Republic of Congo, August 2018 – June 2020

Menu, Tables and Figures

Navigate this article

Tables

| Characteristics (N=145) | Low viral load Ct > 20 (n=105) | High viral load Ct ≤ 20 (n=40) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic | |||

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 44 (41.9) | 17 (42.5) | 61 |

| Male | 61 (58.1) | 23 (57.5) | 84 |

| Age Group, n (%) | |||

| 18–29 | 34 (32.4) | 18 (45.0) | 52 |

| 30–39 | 37 (35.2) | 12 (30.0) | 49 |

| 40–49 | 21 (20.0) | 8 (20.0) | 29 |

| 50+ | 13 (12.4) | 2 (5.0) | 15 |

| Cadres of HCWs, n (%) | |||

| Nurses | 77 (72.6) | 29 (27.4) | 106 |

| Lab technicians | 6 (60.0) | 4 (40.0) | 10 |

| Medical Doctors | 8 (88.9) | 1 (11.1) | 9 |

| Pharmacists | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | 6 |

| Other HCWs | 10 (71.4) | 4 (28.6) | 14 |

| Residence, n (%) | |||

| Ituri | 7 (6.7) | 7 (17.5) | 14 |

| North-Kivu | 98 (93.3) | 33 (82.5) | 131 |

| Vaccination status, n (%) | |||

| Vaccinated | 39 (37.1) | 13 (32.5) | 52 |

| Non-vaccinated | 66 (62.9) | 27 (67.5) | 93 |

| DOA, n (%) | |||

| < 5 days | 66 (62.9) | 16 (40.0) | 82 |

| ≥ 5 days | 39 (37.1) | 24 (60.0) | 63 |

| Clinical | |||

| Vomiting, n (%) | |||

| Non-emetic | 53 (50.5) | 17 (35.0) | 70 |

| Emetic | 52 (49.5) | 23 (65.0) | 75 |

| Diarrhea, n (%) | |||

| Non-diarrheic | 78 (74.3) | 31 (77.5) | 109 |

| Diarrheic | 27 (25.7) | 9 (22.5) | 36 |

| Difficult swallowing, n (%) | |||

| Non-dysphagic | 96 (91.4) | 31 (77.5) | 127 |

| Dysphagic | 9 (8.6) | 9 (22.5) | 18 |

| Sore throat, n (%) | |||

| Painless throat | 98 (93.3) | 34 (85.0) | 132 |

| Painful throat | 7 (6.7) | 6 (15.0) | 13 |

| Hiccups, n (%) | |||

| No hiccups | 101 (96.2) | 34 (85.0) | 135 |

| Hiccups | 4 (3.8) | 6 (15.0) | 10 |

| Confusion, n (%) | |||

| Non-confused | 103 (98.1) | 37 (92.5) | 140 |

| Confused | 2 (1.9) | 3 (7.5) | 5 |

| Hemorrhage, n (%) | |||

| Non-hemorrhagic | 96 (91.4) | 31 (77.5) | 127 |

| Hemorrhagic | 9 (8.6) | 9 (22.5) | 18 |

| Difficult breathing, n (%) | |||

| Non-dyspneic | 100 (95.2) | 35 (87.5) | 135 |

| Dyspneic | 5 (4.8) | 5 (12.5) | 10 |

| Outcome | |||

| Final Status, n (%) | |||

| Live | 79 (75.2) | 14 (35.0) | 93 |

| Died | 26 (24.8) | 26 (65.0) | 52 |

Table 1: Socio-demographic, clinical and outcome characteristics of EVD-Infected Healthcare workers by exposed groups in DR Congo, 2018–2020

| Risk factors | Died, n (%) | Censored, n (%) | cHR (95% CI) | P-value | aHR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 28 (53.4) | 56 (60.2) | 0.81 (0.47 – 1.39) | 0.445 | 0.99 (0.53 – 1.85) | 0.969 |

| Female | 24 (46.6) | 37 (39.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| 18–29 | 19 (36.5) | 33 (35.5) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 30–39 | 18 (34.6) | 31 (33.3) | 1.01 (0.53 – 1.92) | 0.983 | 1.30 (0.63 – 2.72) | 0.472 |

| 40–49 | 9 (17.3) | 20 (21.5) | 0.71 (0.32 – 1.56) | 0.388 | 0.63 (0.25 – 1.64) | 0.348 |

| 50+ | 6 (11.5) | 9 (9.7) | 1.11 (0.44 – 2.79) | 0.820 | 1.10 (0.39 – 3.06) | 0.855 |

| District of residence | ||||||

| North Kivu | 44 (84.6) | 87 (93.4) | 0.48 (0.23 – 1.03) | 0.059 | 0.50 (0.22 – 1.14) | 0.101 |

| Ituri | 8 (15.4) | 6 (6.6) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Viral load level | ||||||

| HVL (Ct ≤ 20) | 35 (67.3) | 17 (32.7) | 3.85 (2.23 – 6.67) | 0.001* | 3.43 (1.78 – 6.59) | < 0.001* |

| LVL (Ct > 20) | 17 (18.3) | 76 (81.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Duration of illness before admission (DOA) | ||||||

| ≥ 5 days | 36 (57.1) | 27 (42.9) | 3.82 (2.12 – 6.90) | 0.001* | 2.23 (1.19 – 4.19) | 0.012* |

| < 5 days | 16 (19.5) | 66 (80.5) | 1 | 1 | ||

| EVD vaccination status | ||||||

| Non-vaccinated | 41 (44.1) | 52 (55.9) | 2.35 (1.21 – 4.57) | 0.012* | 2.56 (1.21 – 5.42) | 0.014* |

| Vaccinated | 11 (21.2) | 41 (78.9) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Confusion | ||||||

| Confused | 4 (80.0) | 1 (20.0) | 3.55 (1.28 – 9.88) | 0.015* | 3.70 (1.05 – 13.05) | 0.042* |

| Non-confused | 48 (34.3) | 92 (65.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Vomiting | ||||||

| Emetic | 37 (49.3) | 38 (50.7) | 2.62 (1.44 – 4.78) | 0.002* | 2.76 (1.31 – 5.81) | 0.008* |

| Non-emetic | 15 (21.4) | 55 (78.6) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Sore throat | ||||||

| Painful throat | 10 (76.9) | 3 (23.1) | 3.72 (1.85 – 7.49) | 0.001* | 2.94 (1.05 – 8.23) | 0.040* |

| Painless throat | 42 (31.8) | 90 (68.2) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Hemorrhage | ||||||

| Hemorrhagic | 13 (25.0) | 5 (5.4) | 2.90 (1.54 – 5.45) | 0.001 | 1.48 (0.70 – 3.13) | 0.307 |

| Non-hemorrhagic | 39 (75.0) | 88 (94.6) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Hiccups | ||||||

| Hiccups | 7 (13.5) | 3 (3.2) | 2.72 (1.22 – 6.05) | 0.014 | 1.12 (0.44 – 2.84) | 0.809 |

| No hiccups | 45 (86.5) | 90 (96.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Dysphagia | ||||||

| Dysphagia | 11 (21.2) | 7 (7.5) | 2.53 (1.30 – 4.94) | 0.006 | 0.54 (0.20 – 1.44) | 0.219 |

| No dysphagia | 41 (78.8) | 86 (92.5) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Diarrhea | ||||||

| Diarrheic | 20 (38.5) | 16 (17.2) | 2.16 (1.23 – 3.79) | 0.007 | 1.24 (0.61 – 2.52) | 0.552 |

| Non-diarrheic | 32 (61.5) | 77 (82.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Dyspnea | ||||||

| Dyspneic | 6 (11.5) | 4 (4.3) | 2.61 (1.11 – 6.14) | 0.028 | 1.47 (0.54 – 4.03) | 0.450 |

| Non-dyspneic | 46 (88.5) | 89 (95.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

* Significant factors with p-value ≤ 0.05

Table 2: Factors predicting death among healthcare workers infected with Ebolavirus in North–Kivu and Ituri, DRC, 2018–2020

Figures

Keywords

- Ebola virus disease

- Hazard of dying

- Ebola vaccination

- Healthcare workers

- DR Congo

Danny Mukandila Kalala1,&, Francis Anto2, Cris Guure3, Steve Ahuka4, Leopold Lubula5, Charles Noora6

1National Public Health Institute, Emergency Operating Centre, Kinshasa, DR Congo, 2School of Public Health, Department of Epidemiology, University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana, 3School of Public Health, Department of Biostatistics, University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana, 4National Institute of Biomedical Research, Department of Virology, Kinshasa, DR Congo, 5Directorate of Epidemiologic Surveillance, Kinshasa, DR Congo, 6Ghana Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training, Accra, Ghana

&Corresponding author: Danny Mukandila Kalala, National Public Health Institute, Emergency Operating Centre, Kinshasa, DR Congo, +243 821614089, Email: dkalalam@gmail.com ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-0461-608X

Received: 18 Mar 2025, Accepted: 11 Jan 2026, Published: 19 Jan 2026

Domain: Infectious Disease Epidemiology

Keywords: Ebola virus disease, hazard of dying, Ebola vaccination, healthcare workers, DR Congo

©Danny Mukandila Kalala et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Danny Mukandila Kalala et al., Factors predicting fatality among healthcare workers infected with Ebola in the Democratic Republic of Congo, August 2018 – June 2020. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2026; 9(1):12. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00072

Abstract

Introduction: Ebolavirus disease (EVD) threatens global public health with fatality rates of 25% – 90%. From August 2018 to June 2020, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) reported several EVD infections, including deaths among healthcare workers (HCWs). We analyzed the factors predicting death among infected HCWs during the 10th Ebola outbreak in the DRC.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from healthcare providers and frontline responders infected with Ebolavirus in North Kivu and Ituri provinces from August 2018 to June 2020. The outcome variable was the time in days from admission to death; the exposure variables were high viral load (Ct value ≤ 20), previous Ebolavirus vaccination, duration from onset to admission (DOA), socio-demographic and clinical factors. We calculated the hazard rate of dying among the subjects; we ensured that the global proportional assumption was met and ran all the exposure variables in a Cox proportional hazard regression at 5% significance level using STATA-17 to assess how they predicted the hazard of dying among the subjects, and we finally performed a backward elimination of factors to select the best-fitting model.

Results: We analyzed data from 145 admitted HCWs out of 172 total infections recorded. Among them, the hazard rate of dying was 3 deaths per 100 infected-HCWs per day; 40 (27.59%) of them had Ct ≤ 20 and 52 (35.86%) died. Factors increasing hazard of dying were Ct ≤ 20 (aHR= 3.43, 95%CI: 1.78 – 6.59), DOA ≥ 5 days (aHR =2.23, 95%CI: 1.19 – 4.19), non-previous Ebola vaccination (aHR =2.56, 95%CI: 1.21 – 4.42), confusion (aHR 3.70, 95%CI: 1.05 – 13.05), vomiting (aHR= 2.76, 95%CI: 1.31 – 5.81) and sore throat (aHR =2.94, 95%CI: 1.05 – 8.23).

Conclusion: High viral load, delayed admission, non-previous Ebola vaccination, confusion, vomiting, and sore throat were associated with increased hazard for death among infected HCWs. Strengthening early diagnosis, timely admission for appropriate treatment, and mandatory Ebola vaccination of HCWs should be advocated to reduce fatality among HCWs during future EVD outbreaks.

Introduction

Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) is a viral haemorrhagic fever caused by Zaire Ebolavirus, one of the species in the family of Filoviridae. Other species are Sudan virus, Tai Forest virus, Bundibugyo virus, Reston virus and Bombali virus, but only species Zaire and Sudan are highly pathogenic and fatal in humans and non-human primates [1]. Zaire Ebolavirus is the most lethal with a case fatality rate of 70 – 90% causing the majority of human EVD outbreaks [2], and its suspected reservoirs are fruit bats, great apes (monkeys, chimpanzees, gorillas) and duikers [3]. Recent studies showed that EVD survivors constitute the virus’s human reservoirs and the disease can be sexually transmitted [3,4].

Transmission of the virus can be animal-to-human by close contact with the bodily fluids of infected animals, or human-to-human by direct contact with bodily fluids of infected persons through mucous membranes or indirectly via fomites [5]. After exposure, the incubation period is 2 – 21 days, a non-infectious period [4]; then occur three phases: the dry phase, from 1 – 5 days, with fever and non-specific symptoms; the wet phase, from the 6th – 7th day, with severe gastro-enteritis disturbances; and the terminal phase, from the 8th day up, with multiple organ failure and hemorrhagic manifestations [4,6]. Laboratory confirmation is done by Xpert Ebola Assay, which detects the virus particles within an hour [7]. Case management consists of early detection and isolation, supportive care with appropriate fluid replacement, and the use of EVD-specific products approved by the US “Food and Drug Administration” (FDA) of the United States of America[8]. Post-Ebola complications that were observed in survivors include mental health issues, abdominal pain, musculoskeletal (persistent myalgia, arthralgia), and neuro-sensorial disturbances [9]. Ocular complications observed in EVD survivors were uveitis, cataracts, and optic or retinal nerve disease; auditory complications (Tinnitus and hearing loss) were observed in a quarter of EVD survivors; the persistence of the virus in the bodily fluids (semen, eye, brain, mammary gland, etc.) of survivors enlarges the extent of concern about the disease. These complications gradually resolve for several months, justifying the need for an EVD survivors programme whose main objective is to monitor survivors to ensure that the virus is eliminated from their bodily fluids [10].

Globally, from 1976 to 2019, the virus has caused over 38 intermittent outbreaks [11]. Unpublished papers showed evidence of three other outbreaks: 2020 Equateur, 2021 North Kivu and 2022 North Kivu [12–15]. These outbreaks were thought to be a resurgence of the previous outbreaks in these regions [16]. Central and West Africa experienced a high proportion of the global burden of this disease, with over 32 outbreaks having caused over 34,393 cases including 15,143 deaths (44%) [3,11]. DRC has experienced the highest burden with 11 EVD outbreaks [1]. The country lies on the Equator, with one-third to the north and two-thirds to the south and sustains the Congo rainforest, which is the 2nd largest rainforest in the world. This ecology is favourable for suspected reservoirs of Ebolavirus and increases the risk of hunters, butchers and consumers of wildlife, hence animal-to-human transmission [4]. The country is also an EVD epidemiologically-linked area where health care workers (HCWs) are at high-risk of infection and death, due to the nature of their work [3,4] and to the challenges related to the availability and proper use of personal protective equipment in health facilities [17]. In DRC, management of Ebola cases usually consists of early detection, isolation, and supportive care, but during the 2018 – 2020 EVD outbreak, the vaccine r-VSV-ZEBOV (Ervebo) was used under compassionate use for the first time for HCWs and contacts due to a rapid increase in the number of cases [18].

Despite efforts deployed to enhance infection prevention and control (IPC) and to vaccinate, several deaths from EVD still occurred among HCWs from 2018 to 2020 in DRC [8]. We conducted this study to determine risk factors for death from EVD among HCWs in order to apply this knowledge to control death among them during future outbreaks.

Methods

Study area

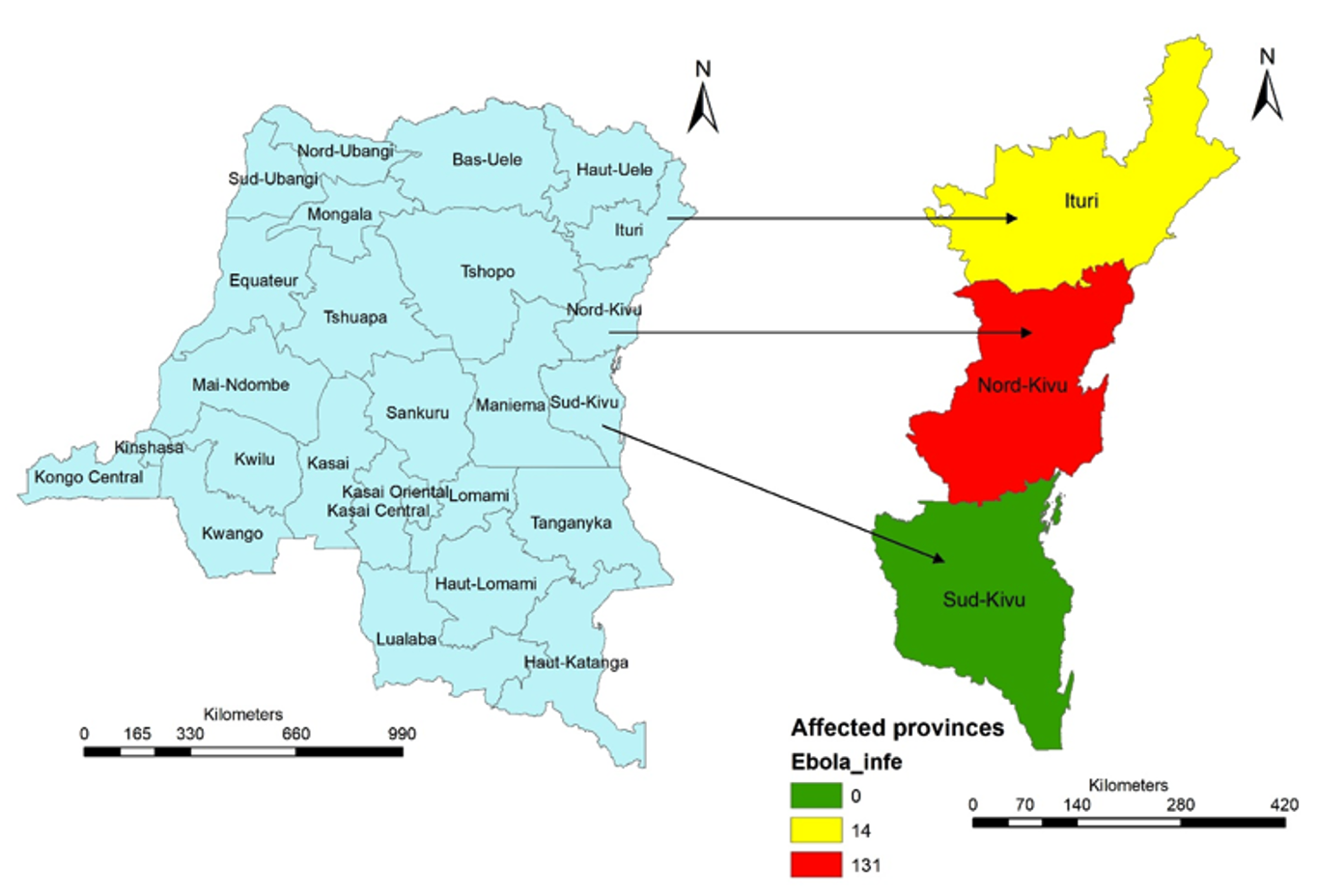

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is located in Central Africa; with an area of 2,345,409 square kilometres, it is the 2nd largest country in Africa after Algeria and the 11th largest country in the World. With a population of over 105 million [20], it is the 11th most populous country in the world. The country is divided into 26 provinces.

Health care workers in the DRC operate in a highly challenging context marked by recurrent epidemics, limited resources, and geographic disparities. Their profile is characterised by strong experience in outbreak response and community-based care, but also by gaps in staffing, training, and retention, especially in rural and conflict-affected areas.

Study design, population and period

Data extracted from the country’s EVD database enabled us to define a cohort of healthcare workers infected with Ebolavirus during the period July 2018–June 2020. We considered the baseline viral load on admission in Ebola treatment centres (ETCs) to classify the subjects into two groups. Subjects with high viral load (Ct value ≤ 20) were the exposed group, and those with low viral load (Ct value > 20) were the non-exposed group [19]. Subjects who were dead upon admission were excluded from the analysis. We analyzed the time to death for both groups from admission; we measured and compared the hazard of dying between the two groups.

Sample size and sampling procedure

For this cohort, we needed a minimum sample size of 106 subjects. This sample size was calculated using Fleiss formula of cohort studies at 95% confidence, and 80% statistical power [20]. Literature showed that 63.5% of deaths occurred in EVD subjects with a Ct value ≤ 20 and 36.5% of deaths in those with a Ct value > 20 [19]; therefore, we used these proportions in the calculations.

Despite this minimum sample size, our sampling approach was a census by using all the eligible subjects. We, therefore, performed a post hoc power analysis to ensure that the observed sample size is enough to detect our effect size. To calculate it we used the proportion of deaths among subjects with Ct value ≤ 20 (p1), the proportion of deaths among subjects with Ct value >20 (p2), the number of subjects with Ct value ≤ 20 (n1), the number of subjects with Ct value >20 (n2) and 95% level of significance (alpha 0.05).

Study variables

The outcome variable was the time to death from admission at ETCs; the primary exposure variable was the baseline Ct value (≤20 or >20); other exposure variables were sex, age, district of residence, qualification, duration from onset of symptoms to admission (DOA≥ 5days or DOA< 5 days), prior EVD vaccination, confusion, vomiting, diarrhea, difficulty swallowing, hemorrhage, hiccups and sore throat.

Eligibility criteria

We included all HCWs in the dataset with a laboratory confirmation of Ebolavirus and a corresponding Ct value from 2018 to 2020. All the variables in the databases were extracted for each subject. We excluded eligible subjects who died or were declared dead upon admission and those without a baseline Ct value.

Data sources and collection

Three data sources of the DRC Ministry of Health were used to collect the data: the Directorate of Epidemiologic Surveillance (DSE), the National Institute of Bio-medical Research (INRB) and the Kinshasa School of Public Health (ESPK). The data were extracted from all three sources by the Data managers of each of these institutions using an Excel spreadsheet and applying the eligibility criteria.

Data processing

The three datasets extracted from DSE (primary dataset), INRB and ESPK were compared for quality control. Data quality issues like missing data, transposition errors, improbable data from the primary dataset were identified and corrected with information found in the INRB and ESPK datasets; duplicated data were identified and removed from the primary dataset. Laboratory variables, like GeneXpert® Assay results with their corresponding Ct values, were extracted from the INRB dataset and matched for each subject in the primary dataset. EVD vaccination status data were extracted from the ESPK and matched for each subject in the primary dataset. This process produced a final dataset that was used for the analysis.

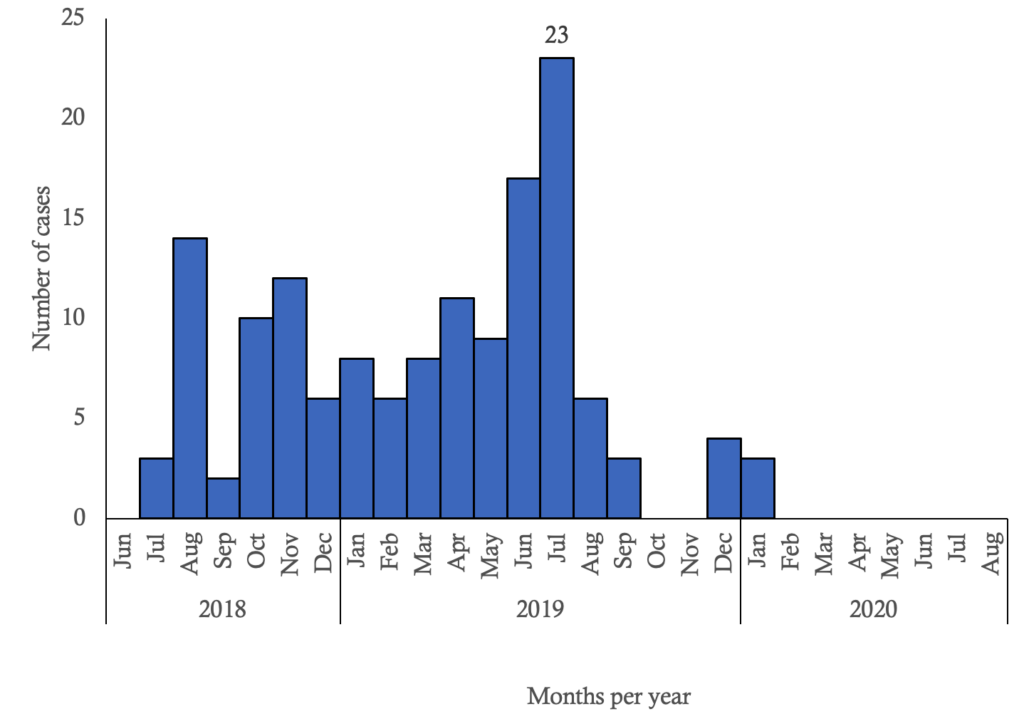

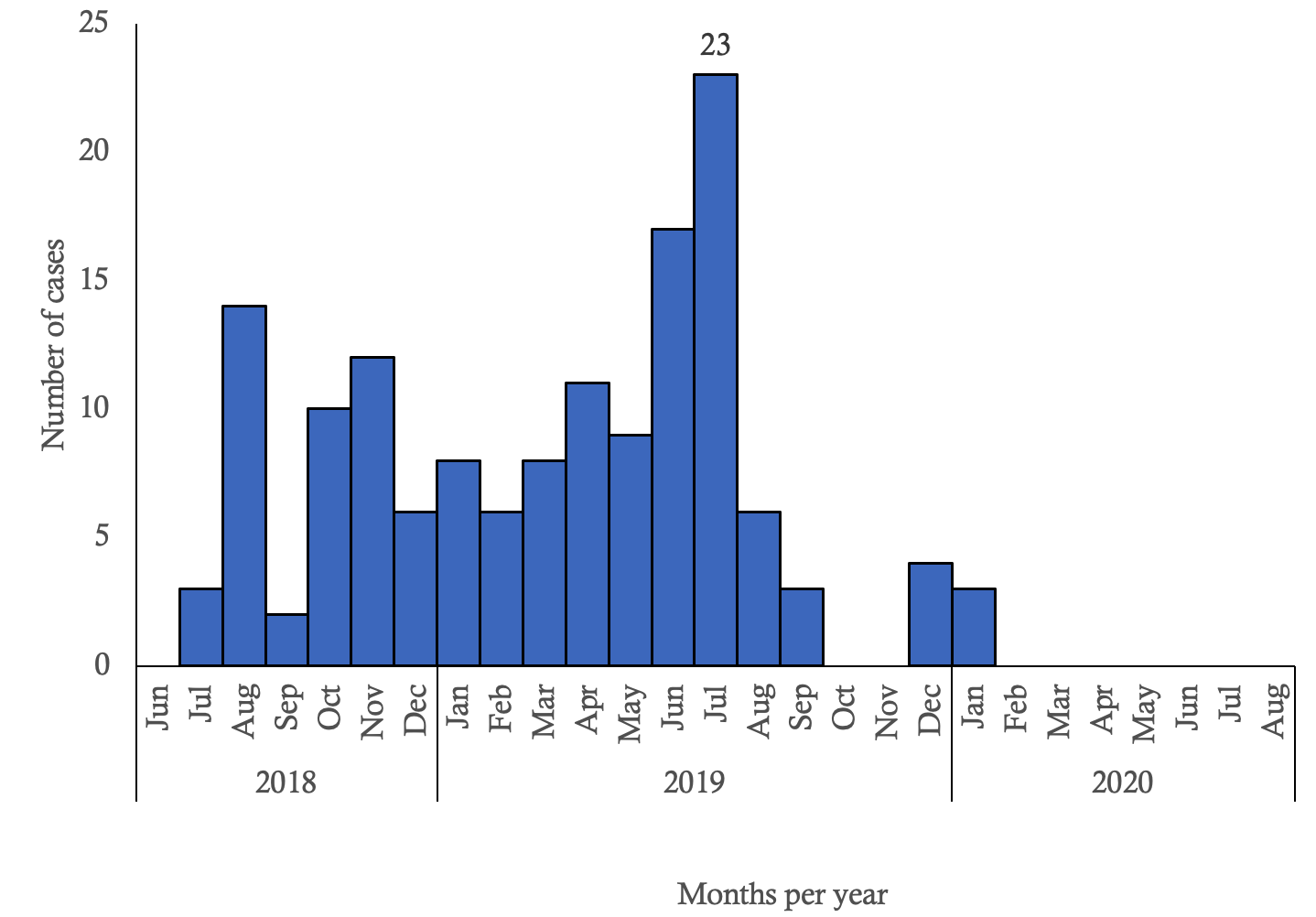

Data analysis

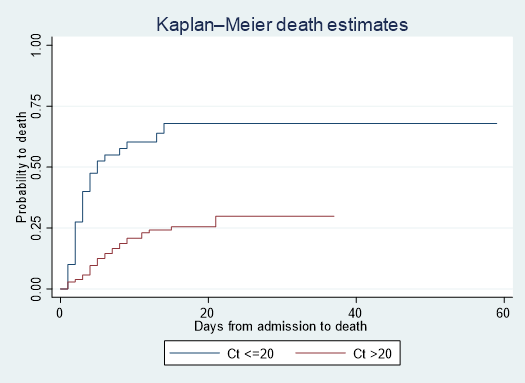

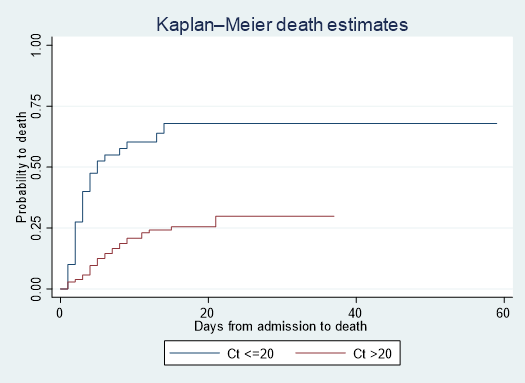

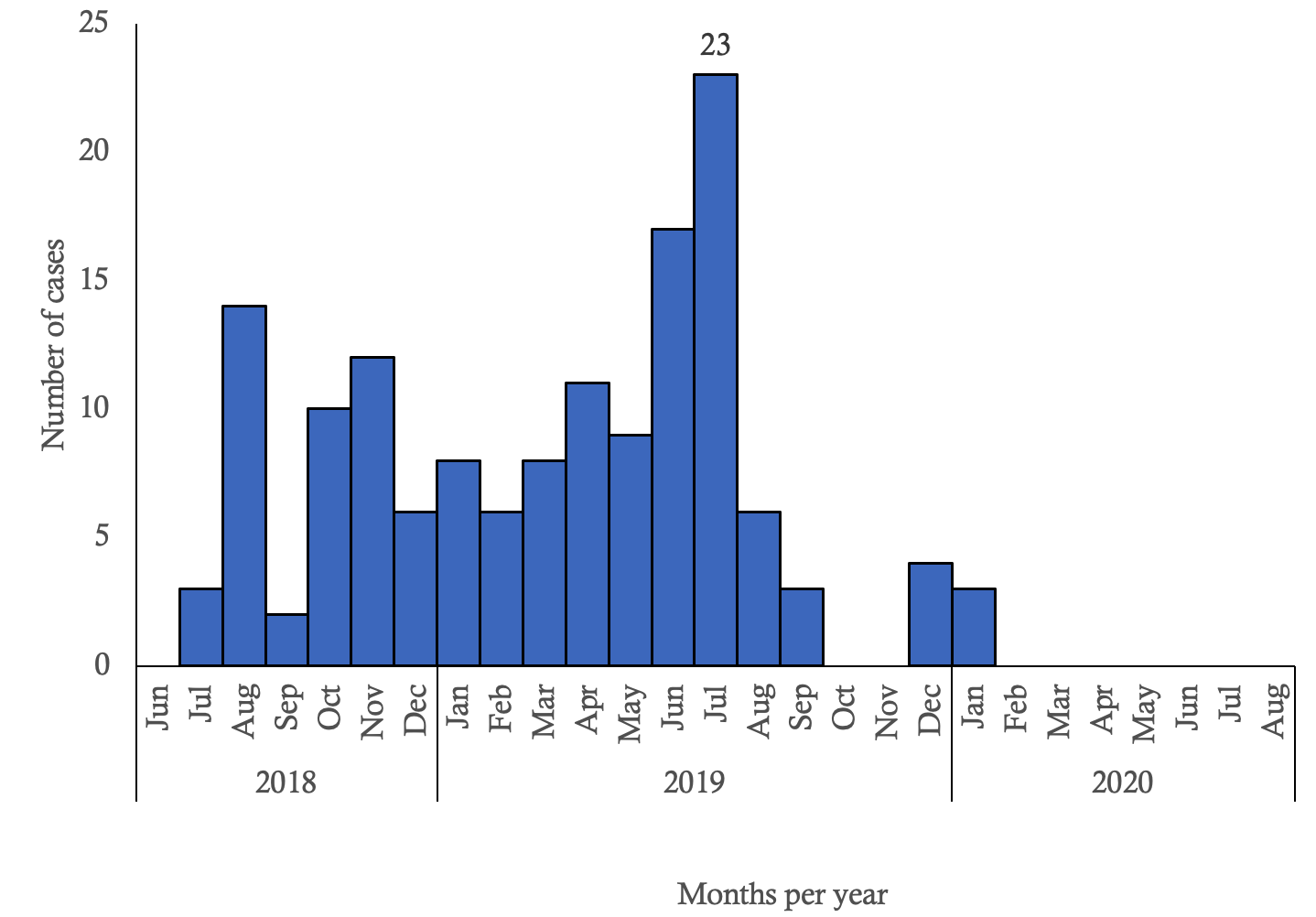

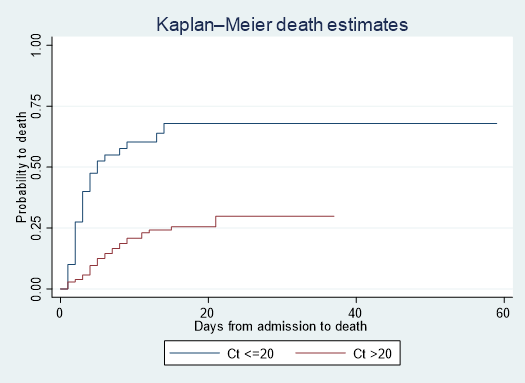

We performed univariate and Cox proportional hazard model analyses. We summarised the period at risk of dying with median and interquartile range, as the distribution of periods at risk of dying for each subject was asymmetrical; we calculated the total person-days at risk of dying, and therefore the hazard rate of dying. We calculated frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. We constructed an epidemic curve of the cases. We coded the outcome variable as “1” for death and “0” for censored; we generated the Kaplan Meier Curves for subjects with high and low viral load and we calculated the logrank test at 5% significance level; we then ran all the exposure variables in a Cox regression model at 5% significance level to assess how they predicted the hazard of dying. We then ran the Schoenfeld Global test to make sure that the proportional hazard assumption was met for each exposure variable. Lastly, we performed a backward elimination of covariates using the Wald test at 5% significance to obtain the best-fitting model. We used Stata: Version 17.0 BE, StataCorp LLC, 1985-2021 to model Cox proportional hazard regression; Microsoft® Excel® 2021 MSO Version 2506 to elaborate a composite table of factors’ frequencies and regression statistics and to generate the epidemic curve; and ArcGIS Desktop Version 10.8 Esri inc. 1999 – 2019 to generate a map of the spatial distribution of cases.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the “Comité d’Ethique de la Recherche de l’Ecole de Santé Publique” of the University of Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of Congo under the approval number ESP/CE/01/2023.

Results

Descriptive characteristics of the outbreak

From August 2018 to June 2020, a total of 3,470 Ebola infections were reported in DR Congo. Out of 3,470 Ebola infections, 172 (5.0%) were recorded as HCWs. Among the HCWs, 27 (15.7%) subjects were dead upon admission at ETCs and were therefore excluded from the analysis. Only 145 records of admitted HCWs were analysed over time as our observed sample size. From these 145 subjects, 40 had Ct value ≤ 20 and 104 subjects had a Ct value > 20. Out of the subjects with Ct value ≤ 20, 26 (65.0%) died; and out of those with Ct value > 20, 26 (24.8%) died (Table 1). The difference in proportion being 40.2%, the statistical power to detect this effect size was 99.57%. The median period at risk of dying was 13 (IQR 5 – 18) days; the total person-time at risk of dying during follow-up was 1,818 person-days, and 52 (35.9%) subjects died; therefore, the hazard rate of dying was 3 (95% CI: 2.2 – 3.8) deaths per 100 person-day.

Sociodemographic, clinical and outcome characteristics of HCWs infected with Ebola

Among the 145 (84.3%) treated subjects, nurses accounted for 106 (73.1%) subjects; forty (27.6%) constituted the exposed group, among whom 23 (57.5%) were males, 33 (82.5%) from North-Kivu, 27 (67.5%) non-vaccinated, 24 (60.0%) with DOA ≥ 5 days; among the unexposed group, 61 (58.1%) were males, 98 (93.3%) from North-Kivu, 66 (62.9%) non-vaccinated, 39 (37.1%) with DOA ≥ 5 days. Among the exposed group, 23 (65.0%) had vomiting, nine (22.5%) diarrhoea, and nine (22.5%) haemorrhage. Among the unexposed, 52 (49.5%) had vomiting, 27 (25.7%) diarrhoea, and nine (8.6%) haemorrhage (Table 1).

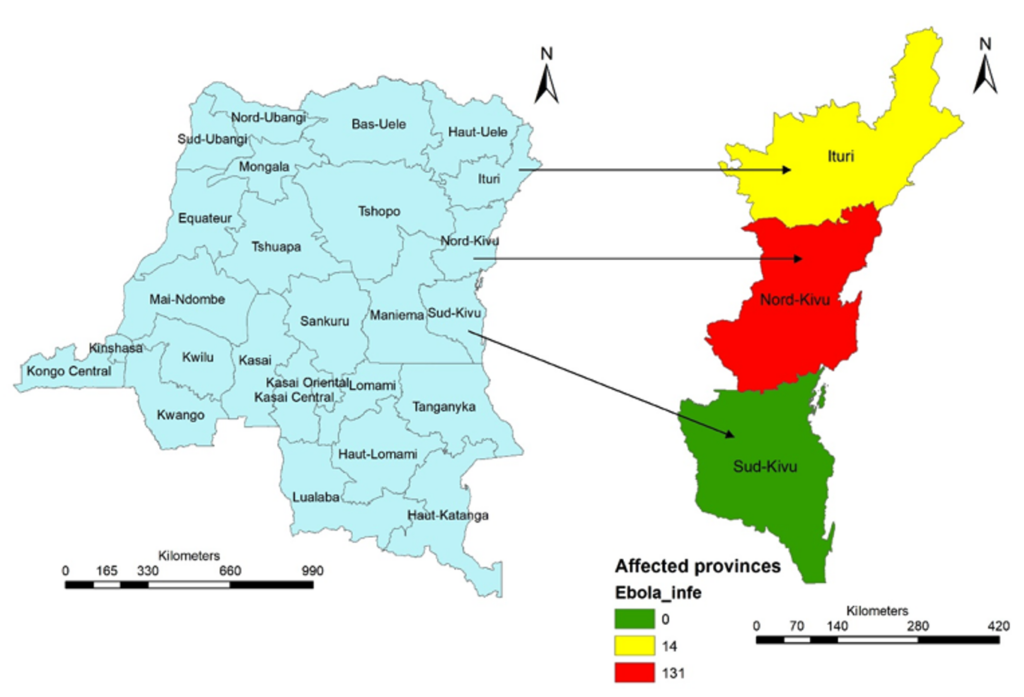

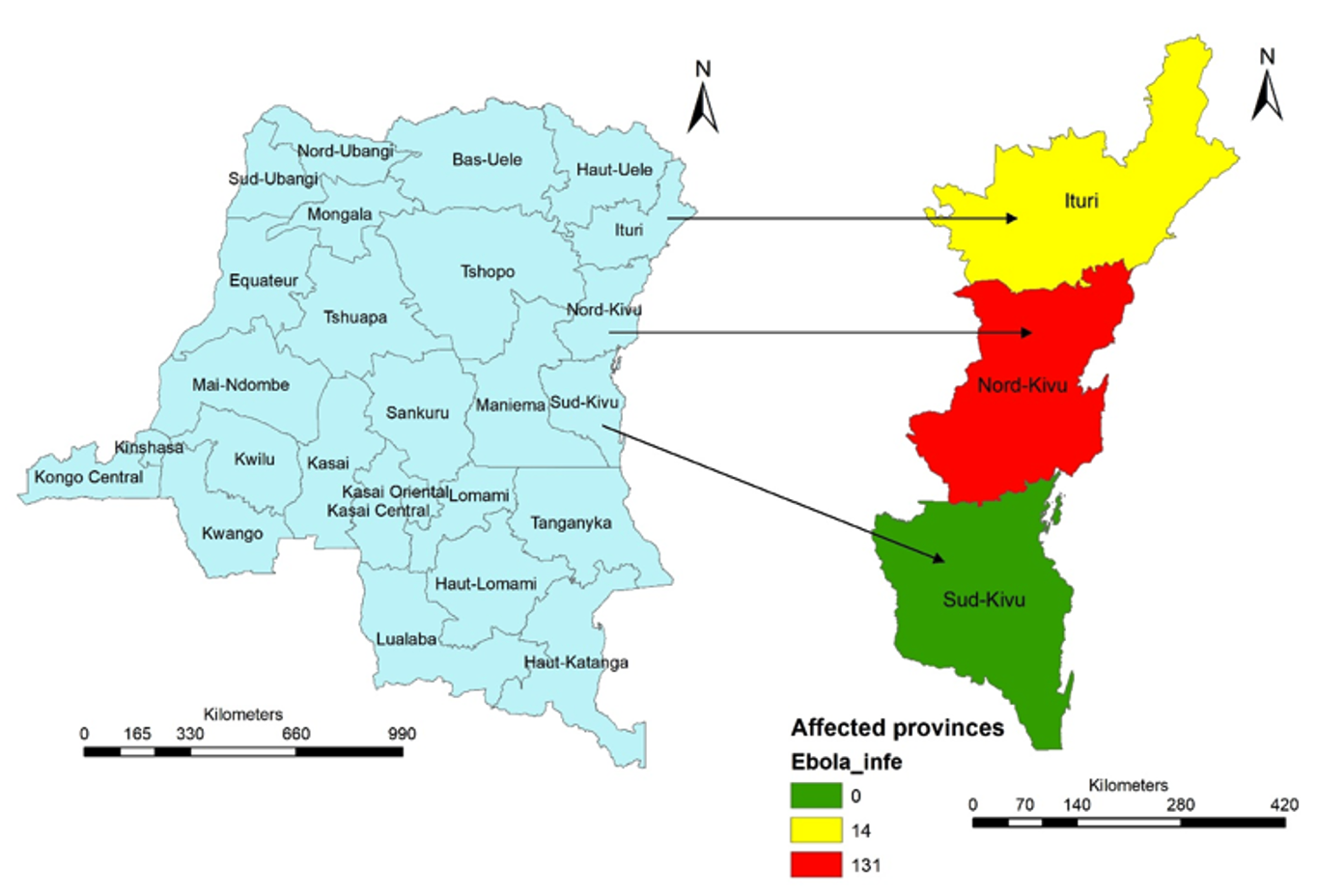

Distribution and evolution of Ebola virus infections among healthcare workers by place

Three provinces of the country were affected by EVD: North Kivu, Ituri and South Kivu. Only North-Kivu and Ituri recorded cases among HCWs: North-Kivu 131 (90.3%) cases and Ituri 14 (9.7%) cases (Figure 1). EVD infections among HCWs were spread from July 2018 to January 2020, with the highest magnitude of 23 infections observed in July 2019 (Figure 2).

Predictors of death

The Kaplan Meier Curves showed that the subjects with high viral load (Ct <=20) had a high probability of death over time. There are significant differences in survival probabilities between the two groups (Log-rank test Chi square = 27.87, p <0.001) (Figure 3). The Schoenfeld Global test showed a Chi-square of 11.7 for 14 degrees of freedom and a p-value of 0.6299. The proportional hazard assumption was met. Factors that independently predicted death among HCWs were a Ct value ≤ 20 (aHR 3.43, 95%CI: 1.78 – 6.59), DOA ≥ 5 days (aHR 2.23, 95%CI: 1.19 – 4.19), non-previous Ebola vaccination (aHR 2.56, 95%CI: 1.21 – 4.42), confusion (aHR 3.70, 95%CI: 1.05 – 13.05), vomiting (aHR 2.76, 95%CI: 1.31 – 5.81) and sore throat (aHR 2.94, 95%CI: 1.05 – 8.23) (Table 2).

Discussion

In this study, we found that a baseline Ct value ≤ 20 on admission, a DOA ≥ 5 days, non-prior Ebola vaccination, presence of confusion, vomiting and sore throat independently predicted increased hazard for death among EVD-infected HCWs.

Having a baseline Ct value ≤ 20 on admission independently increased the hazard of dying. This finding is consistent with the conclusions of several studies that showed that high viral load was highly associated with death among EVD patients [4,21]. The severity of the disease increases with the viral load that peaks at 6 to 7 days from the disease onset. Symptoms include severe gastrointestinal disturbances, including diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain causing dehydration and hypotension that can lead to death.

Several studies showed that early detection and admission at ETCs were associated with patients’ survival to EVD [7,8,22]. Our findings show that HCWs admitted five days or more had an increased hazard of dying at any particular time. According to the clinical evolution of the disease, the wet and terminal phases occur after five days from the onset. During these phases, severe gastro-enteritis, hydro-electrolyte disorders, hemorrhagic manifestations and multiple organ failure were recorded. This informs public health policies about early detection, good contact tracing and advocacy for early self-reporting.

HCWs not previously vaccinated against Ebolavirus were independently associated with a high hazard of dying. EVD-patients who received prior rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine reported fewer EVD-associated symptoms and had reduced time to clearance of viral load, and had reduced length of stay at the Ebola Treatment Center [23] Ebola vaccination with rVSV-ZEBOV is recommended during declared EVD outbreaks and target contacts, contacts of contacts and healthcare workers [24]. The vaccine induces the production of antibodies against the virus necessary to allow the clearance of the virus in the system. This implies the prioritisation of Ebola vaccination response during future outbreaks.

The presence of confusion independently increased the hazard of dying among HCWs. Getting confused was found to be a clinical factor associated with death in EVD patients [19]. EVD patients develop multi-organ failure during the terminal phase, which causes confusion, coma and death [4,6].

Studies have shown that EVD patients develop profuse vomiting from the 6th day (wet phase), which can lead to imbalanced electrolytes, dehydration, hypotension, and shock. Tissue hypoperfusion leads to multiple organ failure, which can explain the occurrence of death. Our findings showed that infected HCWs with vomiting were more likely to die at any particular time. This finding is similar to several studies that concluded that vomiting was significantly associated with an increased risk of death in EVD patients [25,26]. This finding informs public health policies on the availability of well-equipped ETCs with qualified staff in terms of intensive care.

Previous studies also showed that sore throat was present at 47.7 % in the pool of fatal cases of EVD patients [27]. EVD patients with difficulty swallowing due to a sore throat had high fatalities with a significant association [26]. This is consistent with the findings of this study showing that HCWs with a sore throat had an increased hazard for death. This can be explained by difficulty swallowing that prevents oral feeding, which can lead to death by hypoglycemia. This informs the prioritisation of the availability of parenteral feeding during EVD outbreaks.

Limitations

This study did not consider the effect of investigational products on the disease outcome used during the outbreak because the data on the effects of these products were not available. Four EVD investigational products were offered under compassionate use; two of them (mAb114 and REGN-EB3) demonstrated reduced mortality and were approved for use in 2021 [8]. These products reduce the virus replication necessary to allow the individual’s innate and adaptive immune system to clear the infection, but the survival by these products was associated with early treatment and low viral load [8]. Further studies are needed to include the effect of FDA-approved products and to highlight the interaction between them and antibodies from prior Ebola vaccination, as both factors block the virus replication through its surface glycoprotein.

The study did not consider the effect of comorbidities on EVD outcome due to data limitations. Malaria and bacterial co-infections were addressed by the systematic use of anti-malarial drugs and broad-spectrum antibiotics in EVD patients [6]. Other comorbidities with immune deficiency (HIV infection, diabetes, malnutrition, cancer), heart, liver and kidney diseases could negatively influence the disease outcome; and this could be an opportunity for research in future outbreaks.

Conclusion

In conclusion, high viral load on admission, delayed admission for treatment, non-previous Ebola vaccination, confusion, vomiting and sore throat were associated with an increased hazard for death among HCWs infected with Ebola from August 2018 – June 2020. Health authorities should strengthen early diagnosis, timely admission for appropriate treatment and mandatory Ebola vaccination of HCWs to reduce fatality among HCWs during future EVD outbreaks.

What is already known about the topic

- HCW are highly exposed to the disease during the EVD outbreak

- High risk of health system collapse during EVD outbreak

- EVD is a highly fatal disease without timely detection and appropriate treatment

- Vomiting and subsequent dehydration are essentially the cause of death

What this study adds

- Mandatory vaccination of all HCWs during EVD outbreaks is important.

- Admission for proper treatment within five days from the onset of the symptoms improves the outcome

- Monitoring and maintaining the Ct value higher than 20 as possible during treatment is essential

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all individuals and institutions who contributed to this study. We are grateful to Professor Ernest Kenu, Head of Epidemiology Department at the University of Ghana, for his invaluable assistance with ideas, feedbacks and guidance; we also acknowledge Mrs Delia A. Bandoh, Scientific Writer at Ghana Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program (GFELTP) for providing scientific communication guidance; Dr Ameme Donne, Field Coordinator at GFELTP, Dr Gaston Tshiapenda, Field mentor and head of NCDs division at DSE and Dr Alain Magazani, Central Africa regional coordinator at DRC Field Epidemiology Training Program for their assistance on the field for data collection and analysis.

Authors´ contributions

FA conceptualized and designed the study and provided insights into data analysis. SA and LL facilitated data collection and processing and guided the ethical approval. CG and CL performed statistical analyses, interpreted the results, reviewed, and provided feedback on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

| Characteristics (N=145) | Low viral load Ct > 20 (n=105) | High viral load Ct ≤ 20 (n=40) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic | |||

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 44 (41.9) | 17 (42.5) | 61 |

| Male | 61 (58.1) | 23 (57.5) | 84 |

| Age Group, n (%) | |||

| 18–29 | 34 (32.4) | 18 (45.0) | 52 |

| 30–39 | 37 (35.2) | 12 (30.0) | 49 |

| 40–49 | 21 (20.0) | 8 (20.0) | 29 |

| 50+ | 13 (12.4) | 2 (5.0) | 15 |

| Cadres of HCWs, n (%) | |||

| Nurses | 77 (72.6) | 29 (27.4) | 106 |

| Lab technicians | 6 (60.0) | 4 (40.0) | 10 |

| Medical Doctors | 8 (88.9) | 1 (11.1) | 9 |

| Pharmacists | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | 6 |

| Other HCWs | 10 (71.4) | 4 (28.6) | 14 |

| Residence, n (%) | |||

| Ituri | 7 (6.7) | 7 (17.5) | 14 |

| North-Kivu | 98 (93.3) | 33 (82.5) | 131 |

| Vaccination status, n (%) | |||

| Vaccinated | 39 (37.1) | 13 (32.5) | 52 |

| Non-vaccinated | 66 (62.9) | 27 (67.5) | 93 |

| DOA, n (%) | |||

| < 5 days | 66 (62.9) | 16 (40.0) | 82 |

| ≥ 5 days | 39 (37.1) | 24 (60.0) | 63 |

| Clinical | |||

| Vomiting, n (%) | |||

| Non-emetic | 53 (50.5) | 17 (35.0) | 70 |

| Emetic | 52 (49.5) | 23 (65.0) | 75 |

| Diarrhea, n (%) | |||

| Non-diarrheic | 78 (74.3) | 31 (77.5) | 109 |

| Diarrheic | 27 (25.7) | 9 (22.5) | 36 |

| Difficult swallowing, n (%) | |||

| Non-dysphagic | 96 (91.4) | 31 (77.5) | 127 |

| Dysphagic | 9 (8.6) | 9 (22.5) | 18 |

| Sore throat, n (%) | |||

| Painless throat | 98 (93.3) | 34 (85.0) | 132 |

| Painful throat | 7 (6.7) | 6 (15.0) | 13 |

| Hiccups, n (%) | |||

| No hiccups | 101 (96.2) | 34 (85.0) | 135 |

| Hiccups | 4 (3.8) | 6 (15.0) | 10 |

| Confusion, n (%) | |||

| Non-confused | 103 (98.1) | 37 (92.5) | 140 |

| Confused | 2 (1.9) | 3 (7.5) | 5 |

| Hemorrhage, n (%) | |||

| Non-hemorrhagic | 96 (91.4) | 31 (77.5) | 127 |

| Hemorrhagic | 9 (8.6) | 9 (22.5) | 18 |

| Difficult breathing, n (%) | |||

| Non-dyspneic | 100 (95.2) | 35 (87.5) | 135 |

| Dyspneic | 5 (4.8) | 5 (12.5) | 10 |

| Outcome | |||

| Final Status, n (%) | |||

| Live | 79 (75.2) | 14 (35.0) | 93 |

| Died | 26 (24.8) | 26 (65.0) | 52 |

| Risk factors | Died, n (%) | Censored, n (%) | cHR (95% CI) | P-value | aHR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 28 (53.4) | 56 (60.2) | 0.81 (0.47 – 1.39) | 0.445 | 0.99 (0.53 – 1.85) | 0.969 |

| Female | 24 (46.6) | 37 (39.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| 18–29 | 19 (36.5) | 33 (35.5) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 30–39 | 18 (34.6) | 31 (33.3) | 1.01 (0.53 – 1.92) | 0.983 | 1.30 (0.63 – 2.72) | 0.472 |

| 40–49 | 9 (17.3) | 20 (21.5) | 0.71 (0.32 – 1.56) | 0.388 | 0.63 (0.25 – 1.64) | 0.348 |

| 50+ | 6 (11.5) | 9 (9.7) | 1.11 (0.44 – 2.79) | 0.820 | 1.10 (0.39 – 3.06) | 0.855 |

| District of residence | ||||||

| North Kivu | 44 (84.6) | 87 (93.4) | 0.48 (0.23 – 1.03) | 0.059 | 0.50 (0.22 – 1.14) | 0.101 |

| Ituri | 8 (15.4) | 6 (6.6) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Viral load level | ||||||

| HVL (Ct ≤ 20) | 35 (67.3) | 17 (32.7) | 3.85 (2.23 – 6.67) | 0.001* | 3.43 (1.78 – 6.59) | < 0.001* |

| LVL (Ct > 20) | 17 (18.3) | 76 (81.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Duration of illness before admission (DOA) | ||||||

| ≥ 5 days | 36 (57.1) | 27 (42.9) | 3.82 (2.12 – 6.90) | 0.001* | 2.23 (1.19 – 4.19) | 0.012* |

| < 5 days | 16 (19.5) | 66 (80.5) | 1 | 1 | ||

| EVD vaccination status | ||||||

| Non-vaccinated | 41 (44.1) | 52 (55.9) | 2.35 (1.21 – 4.57) | 0.012* | 2.56 (1.21 – 5.42) | 0.014* |

| Vaccinated | 11 (21.2) | 41 (78.9) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Confusion | ||||||

| Confused | 4 (80.0) | 1 (20.0) | 3.55 (1.28 – 9.88) | 0.015* | 3.70 (1.05 – 13.05) | 0.042* |

| Non-confused | 48 (34.3) | 92 (65.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Vomiting | ||||||

| Emetic | 37 (49.3) | 38 (50.7) | 2.62 (1.44 – 4.78) | 0.002* | 2.76 (1.31 – 5.81) | 0.008* |

| Non-emetic | 15 (21.4) | 55 (78.6) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Sore throat | ||||||

| Painful throat | 10 (76.9) | 3 (23.1) | 3.72 (1.85 – 7.49) | 0.001* | 2.94 (1.05 – 8.23) | 0.040* |

| Painless throat | 42 (31.8) | 90 (68.2) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Hemorrhage | ||||||

| Hemorrhagic | 13 (25.0) | 5 (5.4) | 2.90 (1.54 – 5.45) | 0.001 | 1.48 (0.70 – 3.13) | 0.307 |

| Non-hemorrhagic | 39 (75.0) | 88 (94.6) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Hiccups | ||||||

| Hiccups | 7 (13.5) | 3 (3.2) | 2.72 (1.22 – 6.05) | 0.014 | 1.12 (0.44 – 2.84) | 0.809 |

| No hiccups | 45 (86.5) | 90 (96.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Dysphagia | ||||||

| Dysphagia | 11 (21.2) | 7 (7.5) | 2.53 (1.30 – 4.94) | 0.006 | 0.54 (0.20 – 1.44) | 0.219 |

| No dysphagia | 41 (78.8) | 86 (92.5) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Diarrhea | ||||||

| Diarrheic | 20 (38.5) | 16 (17.2) | 2.16 (1.23 – 3.79) | 0.007 | 1.24 (0.61 – 2.52) | 0.552 |

| Non-diarrheic | 32 (61.5) | 77 (82.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Dyspnea | ||||||

| Dyspneic | 6 (11.5) | 4 (4.3) | 2.61 (1.11 – 6.14) | 0.028 | 1.47 (0.54 – 4.03) | 0.450 |

| Non-dyspneic | 46 (88.5) | 89 (95.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

References

- Sivanandy P, Jun PH, Man LW, Wei NS, Mun NFK, Yii CAJ, Ying CCX. A systematic review of Ebola virus disease outbreaks and an analysis of the efficacy and safety of newer drugs approved for the treatment of Ebola virus disease by the US Food and Drug Administration from 2016 to 2020. J Infect Public Health [Internet]. 2022 Mar [cited 2026 Jan 19];15(3):285–92. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2022.01.005. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1876034122000065.

- Choi MJ, Cossaboom CM, Whitesell AN, Dyal JW, Joyce A, Morgan RL, Campos-Outcalt D, Person M, Ervin E, Yu YC, Rollin PE, Harcourt BH, Atmar RL, Bell BP, Helfand R, Damon IK, Frey SE. Use of ebola vaccine: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices, united states, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep [Internet]. 2021 Jan 8 [cited 2026 Jan 19];70(1):1–12. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr7001a1. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/rr/rr7001a1.htm.

- Ohimain EI. Ecology of ebolaviruses. Curr Opin Pharmacol [Internet]. 2021 Oct [cited 2026 Jan 19];60:66–71. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2021.06.009. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1471489221000825.

- Malvy D, McElroy AK, De Clerck H, Günther S, Van Griensven J. Ebola virus disease. Lancet [Internet]. 2019 Feb 15 [cited 2026 Jan 19];393(10174):936–48. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33132-5. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(18)33132-5/fulltext.

- Inungu J, Iheduru-Anderson K, Odio OJ. Recurrent Ebolavirus disease in the Democratic Republic of Congo: update and challenges. AIMS Public Health [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2026 Jan 19];6(4):502–13. doi:10.3934/publichealth.2019.4.502. Available from: https://www.aimspress.com/article/10.3934/publichealth.2019.4.502.

- Jacob ST, Crozier I, Fischer WA, Hewlett A, Kraft CS, Vega MADL, Soka MJ, Wahl V, Griffiths A, Bollinger L, Kuhn JH. Ebola virus disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers [Internet]. 2020 Feb 20 [cited 2026 Jan 19];6(1):13. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-0147-3. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41572-020-0147-3.

- Mukadi-Bamuleka D, Bulabula-Penge J, Jacobs BKM, De Weggheleire A, Edidi-Atani F, Mambu-Mbika F, Legand A, Klena JD, Fonjungo PN, Mbala-Kingebeni P, Makiala-Mandanda S, Kajihara M, Takada A, Montgomery JM, Formenty P, Muyembe-Tamfum JJ, Ariën KK, Van Griensven J, Ahuka-Mundeke S, Kavunga-Membo H, Ishara-Nshombo E, Roge S, Mulopo-Mukanya N, Tsiwedi-Tsilabia E, Muhindo-Milonde E, Kavira-Muhindo MA, Morales-Betoulle ME, Nkuba-Ndaye A. Head-to-head comparison of diagnostic accuracy of four Ebola virus disease rapid diagnostic tests versus GeneXpert® in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo outbreaks: a prospective observational study. eBioMedicine [Internet]. 2023 May [cited 2026 Jan 19];91:104568. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104568. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/ebiom/article/PIIS2352-3964(23)00133-0/fulltext.

- Tshiani Mbaya O, Mukumbayi P, Mulangu S. Review: insights on current fda-approved monoclonal antibodies against ebola virus infection. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2021 Aug 30 [cited 2026 Jan 19];12:721328. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.721328. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.721328/full.

- Tozay S, Fischer WA, Wohl DA, Kilpatrick K, Zou F, Reeves E, Pewu K, DeMarco J, Loftis AJ, King K, Grant D, Schieffelin J, Gorvego G, Johnson H, Conneh T, Williams G, Nelson JAE, Hoover D, McMillian D, Merenbloom C, Hawks D, Dube K, Brown J. Long-term complications of ebola virus disease: prevalence and predictors of major symptoms and the role of inflammation. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2019 Nov 6 [cited 2026 Jan 19];71(7):1749–55. doi:10.1093/cid/ciz1062. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/71/7/1749/5613876.

- World Health Organization. Clinical care for survivors of Ebola virus disease: Interim Guidance [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2016 Jan 25 [cited 2026 Jan 19]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/204235.

- Arcos González P, Fernández Camporro Á, Eriksson A, Alonso Llada C. The epidemiological presentation pattern of ebola virus disease outbreaks: changes from 1976 to 2019. Prehosp Disaster Med [Internet]. 2020 Jun [cited 2026 Jan 19];35(3):247–53. doi:10.1017/S1049023X20000333. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S1049023X20000333/type/journal_article.

- Pratt C. Two Ebola virus variants circulating during the 2020 Equateur Province outbreak [Internet]. 2020 Aug 15 [cited 2026 Jan 19]. Available from: https://virological.org/t/two-ebola-virus-variants-circulating-during-the-2020-equateur-province-outbreak/538.

- Pratt C. August 2022 EVD case in DRC linked to 2018–2020 Nord Kivu EVD outbreak [Internet]. 2022 Aug [cited 2026 Jan 19]. Available from: https://virological.org/t/august-2022-evd-case-in-drc-linked-to-2018-2020-nord-kivu-evd-outbreak/889.

- Pratt C. April 2022 Ebola virus disease case in Equateur Province, DRC, represents a new spillover event [Internet]. 2022 Apr [cited 2026 Jan 19]. Available from: https://virological.org/t/april-2022-ebola-virus-disease-case-in-equateur-province-drc-represents-a-new-spillover-event/795.

- Pratt C. Oct 2021 EVD case in DRC linked to 2018–2020 Nord Kivu EVD outbreak [Internet]. 2021 Oct [cited 2026 Jan 19]. Available from: https://virological.org/t/oct-2021-evd-case-in-drc-linked-to-2018-2020-nord-kivu-evd-outbreak/762.

- Judson SD, Munster VJ. The multiple origins of ebola disease outbreaks. J Infect Dis [Internet]. 2023 Aug 13 [cited 2026 Jan 19];228(Supplement_7):S465–73. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiad352. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/228/Supplement_7/S465/7245174.

- Ngatu NR, Kayembe NJM, Phillips EK, Okech-Ojony J, Patou-Musumari M, Gaspard-Kibukusa M, Madone-Mandina N, Godefroid-Mayala M, Mutaawe L, Manzengo C, Roger-Wumba D, Nojima S. Epidemiology of ebolavirus disease (Evd) and occupational EVD in health care workers in Sub-Saharan Africa: Need for strengthened public health preparedness. J Epidemiol [Internet]. 2017 Oct [cited 2026 Jan 19];27(10):455–61. doi:10.1016/j.je.2016.09.010. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0917504017300886.

- Tomori O, Kolawole MO. Ebola virus disease: current vaccine solutions. Curr Opin Immunol [Internet]. 2021 Aug [cited 2026 Jan 19];71:27–33. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2021.03.008. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0952791521000285.

- Hartley MA, Young A, Tran AM, Okoni-Williams HH, Suma M, Mancuso B, Al-Dikhari A, Faouzi M. Predicting ebola severity: a clinical prioritization score for ebola virus disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2017 Feb 2 [cited 2026 Jan 19];11(2):e0005265. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005265. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005265.

- World Health Organization. Therapeutics for Ebola virus disease [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2022 Aug 19 [cited 2026 Jan 19]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/361697.

- Haaskjold YL, Bolkan HA, Krogh KØ, Jongopi J, Lundeby KM, Mellesmo S, Garcés PSJ, Jøsendal O, Øpstad Å, Svensen E, Fuentes LMZ, Kamara AS, Riera M, Arranz J, Roberts DP, Stamper PD, Austin P, Moosa AJ, Marke D, Hassan S, Eide GE, Berg Å, Blomberg B. Clinical features of and risk factors for fatal ebola virus disease, Moyamba District, Sierra Leone, December 2014–February. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2016 Sep [cited 2026 Jan 19];22(9):1537–44. doi:10.3201/eid2209.151621. Available from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/22/9/15-1621_article.

- Rupani N, Ngole ME, Lee JA, Aluisio AR, Gainey M, Perera SM, Ntamwinja LK, Matafali RM, Muhayangabo RF, Makoyi FN, Laghari R, Levine AC, Kearney AS. Effect of recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus–zaire ebola virus vaccination on ebola virus disease illness and death, democratic republic of the congo. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2022 Jun [cited 2026 Jan 19];28(6):1180–88. doi:10.3201/eid2806.212223. Available from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/28/6/21-2223_article.htm.

- Ilunga Kalenga O, Moeti M, Sparrow A, Nguyen VK, Lucey D, Ghebreyesus TA. The ongoing ebola epidemic in the democratic republic of congo, 2018–2019. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2019 Jul 25 [cited 2026 Jan 19];381(4):373–83. doi:10.1056/NEJMsr1904253. Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMsr1904253.

- Amoa‑Dadzeasah M, Kartsonaki C, Merson L, Yeabah MT. Biomarkers and Mortality in Ebola Virus Disease Patients [master’s thesis]. Limbe (Cameroon): AIMS-Cameroon; 2022 May 29 [cited 2026 Jan 19]. Available from: https://www.iddo.org/sites/default/files/publication/2022-11/Mavis%20Amoa-Dadzeasah_Essay_2021-2022.pdf.

- Kangbai JB, Heumann C, Hoelscher M, Sahr F, Froeschl G. Sociodemographic and clinical determinants of in-facility case fatality rate for 938 adult Ebola patients treated at Sierra Leone Ebola treatment center. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2020 Apr 21 [cited 2026 Jan 19];20(1):293. doi:10.1186/s12879-020-04994-9. Available from: https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-020-04994-9.

- Moole H, Chitta S, Victor D, Kandula M, Moole V, Ghadiam H, Akepati A, Yerasi C, Uppu A, Dharmapuri S, Boddireddy R, Fischer J, Lynch T. Association of clinical signs and symptoms of Ebola viral disease with case fatality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect [Internet]. 2015 Sep 1 [cited 2026 Jan 19];5(4):28406. doi:10.3402/jchimp.v5.28406. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3402/jchimp.v5.28406.

- US Congressional Research Service. Democratic Republic of Congo: Background and U.S. Relations [Internet]. Washington (DC): US Congressional Research Service; 2022 Mar 25 [cited 2026 Jan 19]. Report No. R43166. Available from: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R43166.