Research | Open Access | Volume 9 (1): Article 01 | Published: 02 Jan 2026

Evaluation of community health workers’ training for community-based cardiovascular disease risk factors screening in rural Morogoro, Tanzania

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Google Scholar

Navigate this article

Tables

| Day | Session | Training Contents |

|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Session 1.0 | Opening and Introductions |

| Session 1.1 | Orientation to training and review of the training schedule | |

| Session 1.2 | Pre-training assessment | |

| Session 1.3 | Review of research study and training expectations | |

| Session 1.4 | Definition and overview of major CVDs | |

| Session 1.5 | Definition and overview of modifiable CVD risk factors | |

| Session 1.6 | Definition and overview of non-modifiable CVD risk factors | |

| Day 2 | Session 2.0 | Measurements |

| Session 2.1 | Measuring blood pressure | |

| Session 2.2 | Measuring body weight | |

| Session 2.3 | Measuring body height | |

| Session 2.4 | Practical session | |

| Day 3 | Session 3.0 | CVD Screening Procedures and Interpretation of Results |

| Session 3.1 | Screening for overweight and obesity | |

| Session 3.2 | Screening for hypertension | |

| Session 3.3 | Screening for diabetes | |

| Session 3.4 | Screening for dyslipidemia | |

| Session 3.5 | Assessing and communicating the 10-year risk of developing CVD | |

| Day 4 | Session 4.0 | Health Education and Healthy Lifestyle Promotion |

| Session 4.1 | Deleterious effects of CVD risk factors | |

| Session 4.2 | Ideal/normal body weight | |

| Session 4.3 | Smoking cessation | |

| Session 4.4 | Reduction of excess alcohol drinking | |

| Session 4.5 | Healthy dietary habits | |

| Session 4.6 | Physical exercise and physical activity | |

| Session 4.7 | Health check-ups | |

| Day 5 | Session 5.0 | Effective Communication Skills for Behavior Change |

| Session 5.1 | How to evoke the desire to change behavior | |

| Session 5.2 | Skills and techniques to enable behavior change | |

| Session 5.3 | Providing reasons/rationale for behavior change | |

| Session 5.4 | Explaining the importance/benefits of changing such behavior | |

| Session 5.5 | Supporting and setting goals for individual behavior change | |

| Session 5.6 | Post-training assessment of knowledge and skills | |

| Session 5.7 | Administrative and logistics | |

| Session 5.8 | Questions and answers, conclusions, and final wrap-up |

Table 1: Schedule and Contents for Cardiovascular Disease Training to Community Health Workers

| Variable | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | ||

| <35 | 6 | 33.3 |

| ≥35 | 12 | 66.7 |

| Sex | ||

| Males | 5 | 27.8 |

| Females | 13 | 72.2 |

| Education level | ||

| Secondary education | 18 | 100.0 |

| Participated in pre- and post-training assessments | ||

| Pre-training assessment | 18 | 100.0 |

| Post-training assessment | 18 | 100.0 |

| Ever heard about CVDs | ||

| Yes | 18 | 100.0 |

| No | 0 | 0.0 |

| Source of information | ||

| Radio (Yes) | 15 | 83.3 |

| Television (Yes) | 14 | 77.8 |

| Health worker (Yes) | 6 | 33.3 |

| Relative/friend/neighbor (Yes) | 10 | 55.6 |

| Previous training (Yes) | 7 | 38.9 |

| Online/Internet (Yes) | 6 | 33.3 |

Table 2: Characteristics of the Community Health Workers

| Variable | Pre-training | Post-training | Mean or % Change (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Exam Test Score | ||||

| Mean test score | 70.3±4.1 | 87.7±5.9 | 17.4 (10.1, 24.8) | <0.001 |

| Mean Knowledge Scores¶ | ||||

| Mean knowledge score for CVD risk factors | 5.9±3.0 | 9.6±1.0 | 3.7 (2.2, 5.2) | <0.001 |

| Mean knowledge score for CVD warning signs | 4.2±2.2 | 8.9±0.3 | 4.7 (3.6, 5.7) | <0.001 |

| Mean knowledge score for a healthy diet | 5.2±0.7 | 5.9±0.3 | 0.7 (0.3, 1.1) | <0.001 |

| Mean knowledge score for the appropriate action | 5.8±0.5 | 6.0±0.0 | 0.2 (-0.0, 0.5) | 0.095 |

| Overall mean knowledge score | 21.1±5.5 | 30.4±1.3 | 9.3 (6.6, 12.1) | <0.001 |

| Proportion with Good Knowledge‡ | ||||

| Good knowledge of risk factors | 44.4 | 100.0 | 55.6 (26.2, 73.8) | <0.001 |

| Good knowledge of warning signs | 16.7 | 100.0 | 83.3 (55.0, 95.0) | <0.001 |

| Good knowledge of risk factors and warning signs | 27.8 | 100.0 | 72.2 (42.8, 87.2) | <0.001 |

¶ Results are presented as mean (standard deviation) ‡ Results are presented as a number (percentage) | ||||

Table 3: Pre- and Post-Training Knowledge of Risk Factors and Warning Signs for Cardiovascular Diseases

| Variable | Correct Response (%) | % Change (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Training | After Training | |||

| Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Diseases | ||||

| Older age | 61.1 | 94.4 | 33.3 (4.8, 55.2) | 0.016 |

| Obesity/Overweight | 72.2 | 94.4 | 22.2 (-4.0, 44.0) | 0.074 |

| Hypertension | 72.2 | 94.4 | 22.2 (-4.0, 44.0) | 0.074 |

| Dyslipidemia | 88.9 | 100.0 | 11.1 (-8.3, 28.3) | 0.146 |

| Smoking | 44.4 | 100.0 | 55.6 (26.2, 73.8) | <0.001 |

| Excess alcohol consumption | 50.0 | 100.0 | 50.0 (21.1, 68.9) | <0.001 |

| Physical inactivity | 72.2 | 94.4 | 22.2 (-4.0, 44.0) | 0.074 |

| Family history | 44.4 | 88.9 | 44.4 (13.2, 66.8) | 0.005 |

| Stress | 66.7 | 100.0 | 33.3 (7.0, 53.0) | 0.007 |

| Kidney disease | 16.7 | 94.4 | 77.8 (48.1, 91.9) | <0.001 |

| High-fat diet | 100.0 | 94.4 | -5.6 (-21.3, 11.3) | 0.310 |

| Warning Signs for Cardiovascular Diseases | ||||

| Headache | 72.2 | 100.0 | 22.8 (2.8, 47.2) | 0.016 |

| Chest pain | 27.8 | 100.0 | 72.2 (42.8, 87.2) | <0.001 |

| Dyspnea/difficulty in breathing | 94.4 | 100.0 | 5.6 (-11.3, 21.3) | 0.310 |

| Sweating | 50.0 | 94.4 | 44.4 (14.4, 65.6) | 0.003 |

| Vomiting | 5.6 | 100.0 | 94.4 (68.7, 100.0) | <0.001 |

| Pain in the teeth/jaw | 0.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 (76.5, 100.0) | <0.001 |

| Painful shoulder/hand | 50.0 | 100.0 | 50.0 (21.1, 68.9) | <0.001 |

| Loss of consciousness | 66.7 | 100.0 | 33.3 (7.0, 53.0) | 0.007 |

| Dizziness or lightheadedness | 55.6 | 100.0 | 38.9 (9.5, 60.5) | 0.007 |

Table 4: Pre- and Post-Training Knowledge of Specific Risk Factors and Warning Signs for Cardiovascular Diseases

Figures

Keywords

- Community Health Workers

- Training

- Knowledge

- Tanzania

Alfa Muhihi1,2,3,&, Amani Anaeli4, Marina Njelekela5,6, Rose Mpembeni7, David Urassa1

1Department of Community Health, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, United Nations Road, Upanga, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2Africa Academy for Public Health, Plot 82A Light Industrial Area, Mikocheni, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 3The Bernard Lown Scholars Program, Department of Global Health and Population, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, 4Department of Development Studies, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, United Nations Road, Upanga, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 5Department of Physiology, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, United Nations Road, Upanga, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 6Deloitte Consulting Limited, Aris House, Plot #152, Haile Selassie Road, Oysterbay, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 7Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, United Nations Road, Upanga, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

&Corresponding author: Alfa Muhihi, Department of Community Health, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, P. O. Box 65001, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, Email: selukundo@gmail.com, amuhihi@aaph.or.tz ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4477-7300

Received: 08 Jul 2025 Accepted: 30 Dec 2025, Published: 02 Jan 2026

Domain: Non-Communicable Disease Epidemiology

Keywords: Community Health Workers, Training, Knowledge, Tanzania

©Alfa Muhihi et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Alfa Muhihi et al., Evaluation of community health workers’ training for community-based cardiovascular disease risk factors screening in rural Morogoro, Tanzania. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;9(1):01. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00155

Abstract

Introduction

The global burden of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) has continued to rise, disproportionately affecting low and middle-income countries (LMICs)[1]. In 2019, one-third of deaths worldwide were estimated to be due to CVDs.[2] In Africa, available data indicate that two out of every five deaths due to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are caused by CVDs [3]. Contrary to the declining trend observed in many developed countries [4, 5], reports indicate that Africa has experienced nearly a 50% increase in the burden of CVDs in recent decades [6]. The mortality burden due to CVDs is projected to be 36.6 million deaths by 2050 [7]. In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) attributable to CVDs increased by 67%, making CVDs the second leading cause of disease burden in the region [6]. The rising mortality from CVDs and associated risk factors in LMICs is largely driven by ongoing epidemiological and nutritional transition, rapid urbanization, changing lifestyles, and improving economic conditions [8].

In Tanzania, the proportion of deaths attributable to ischemic heart diseases, stroke, and hypertensive heart diseases nearly doubled from 6.4% to 11.3% between 2000 and 2017.[9] While mortality from all other causes has declined, deaths from stroke and ischemic heart disease have increased by 23.7% and 37.9%, respectively, between 2009 and 2019 [10]. CVDs are now the leading cause of non-communicable (NCD) related deaths, accounting for 40% of all NCD mortality [11]. The increase in CVD-related deaths in Tanzania is attributable to the rising burden of lifestyle-related risk factors among young and middle-aged adults [12, 13]. Improvement in economic conditions also plays an important role, due to its influence on eating behaviour [14].

Evidence from high-income countries has demonstrated that community-based interventions targeting population risk factors such as blood pressure, smoking, and cholesterol can reduce CVD-related morbidity and mortality [5, 15]. In LMICs, community-based interventions implemented by CHWs have contributed to improved maternal and child health outcomes by promoting facility delivery, vaccination, breastfeeding, and hygiene practices to prevent infectious diseases [16]. More recently, there has been emerging evidence that CHWs can also play a critical role in the prevention and control of CVDs by improving community knowledge, self-management, and behavior related to CVD risk factors [17, 18].

Tanzania’s 2021-2026 strategy and action plan for preventing and controlling NCDs emphasizes health promotion to increase awareness of NCDs and their risk factors, promote healthy lifestyles, and strengthen leadership for community involvement and empowerment [19]. Although CHWs are recognised as providers of preventive and health promotion services, their specific roles have not been clearly defined, except for the provision of community-based rehabilitation and palliative care services [19].

There is a gap in evidence regarding CHW training, knowledge acquisition, and skills development for effective and successful implementation of community-based health promotion interventions aimed at CVD prevention and control in Tanzania. The current CHW training package includes health promotion, maternal and child health, prevention and control of communicable diseases, prevention and control of non-communicable diseases, prevention and control of malnutrition, and social welfare [20]. In this analysis, we evaluated the effects of a short, focused training program designed to impart the required knowledge and skills to CHWs to enable them to provide health education, conduct community-based screening, and promote healthy lifestyles for the reduction of blood pressure and other CVD risk factors in rural Morogoro, Tanzania.

Methods

Study design and setting

This evaluation was conducted as part of a cluster-randomised trial of CHW interventions for reducing blood pressure among adults in Kilombero and Ulanga districts in Morogoro region, Tanzania. Together, the two districts cover a total surface area of 28,669 square kilometres and are located approximately 450 kilometres by road southwest of Tanzania’s commercial capital of Dar es Salaam. Kilombero and Ulanga districts were selected for this study because of the high number of CHWs (approximately 14 per 1,000 population) who had been trained through various initiatives [21] and the reports of high CVD-related deaths [22].

The intervention

The intervention package for the cluster-randomised trial consisted of two components, namely, training of CHWs on CVDs and their risk factors, and Home-based health education and healthy lifestyle promotion delivered by trained CHWs.

CHW training content and materials

Training of CHWs was conducted in September 2019 in Kilombero district, Morogoro, Tanzania. The training was designed to equip CHWs with knowledge and skills regarding hypertension and other CVD risk factors. The training contents are summarized in Table 1 and covered the following key thematic areas; 1) Overview of major CVDs, and their modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors, 2) Clinical and anthropometric measurement (blood pressure, body weight, and height), 3) Screening procedures and interpretation of results including 10-year risk for CVD event, 4) Health education and healthy lifestyle promotion strategies, and 5) Motivational and effective communication skills for behavior change, including techniques to facilitate setting simple and achievable goals for specific behavior change.

Health education messages focused on (a) the deleterious effects of CVD risk factors, (b) importance of maintaining an ideal body weight, (c) smoking cessation, (d) reduction of excessive alcohol consumption, (e) lowering salt intake, (f) increasing consumption of fresh fruits and green leafy vegetables, (g) using vegetable cooking oil and (h) promoting use of unrefined cereals.

The training was conducted for five days and was based on the WHO training manual for the prevention of NCDs and promotion of healthy lifestyles[23]. Additional CVD-related topics were adapted from the Tanzanian Curriculum for Basic Technician Certificate in Community Health,[24] a one-year CHWs training program. The investigator (AJM) delivered the training through slow-paced interactive lectures, PowerPoint presentations, in-class exercises, and practical sessions.

Pre- and post-training evaluation of knowledge

We conducted an outcome evaluation of knowledge and skills using a test adapted from the WHO training manual to prevent NCDs and promote healthy lifestyles [23]. The test consisted of 11 items about knowledge of risk factors and nine items on knowledge of warning signs for heart attack and stroke. Each correct response was assigned a score of 1, and 0 for each incorrect response. Knowledge scores were summed separately for risk factors (maximum 11 points) and warning signs (maximum 9 points). Knowledge was categorized as poor (0-3 points), moderate (4-6 points), or good (≥7 points) for each domain. Combined knowledge of risk factors and warning signs for heart attack and stroke was assessed from the summation of knowledge for risk factors and warning signs (maximum 20 points), and was categorized as poor (0-6 points), moderate (7-14 points), or good (≥15 points). In addition to knowledge assessment, the post-training assessment included extra practical questions to assess CHWs’ skills in conducting anthropometric measurements, blood pressure, and using the office-based Globorisk prediction chart to calculate individual CVD risk scores [25]. Although the Tanzanian training guide to CHWs considers a learner who attains 50% as having passed and qualified for certification, we used a minimum post-training knowledge pass mark of 75% based on experience from other studies that provided short, focused training to CHWs [26].

Description of home-based CHW interventions

Trained CHWs were involved in the intervention study to provide home-health education and a healthy lifestyle promotion intervention to participants with elevated blood pressure in the intervention villages. The health messages provided focused on the effects of CVD risk factors and avoiding unhealthy behaviours such as smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, and dietary habits such as high salt intake, poor intakes of fruits and vegetables. CHWs assisted participants to set achievable behaviour change goals and monitored blood pressure. The CHWs’ home visits were conducted monthly for the first six months, then bi-monthly for 12 months. To ensure consistency and quality, CHWs used a structured intervention checklist as a reference guide to go through all required aspects of the intervention during each home visit. Participants with hypertension in the control group were referred to the local health facility for standard care in accordance with the Tanzanian guidelines. They were not visited at home for health education, healthy lifestyle promotion or blood pressure monitoring. proper management. They continued with and followed the standard of care

Data analysis

Demographic characteristics of the CHWs were summarised using frequency and proportions. Knowledge test results or risk factors and warning signs for heart attack and stroke, before and after training, were analysed using means and standard deviation for continuous variables or frequency and proportions for categorical variables. Pre- and post-training comparison of mean knowledge scores was performed using a paired sample t-test, while the change in proportion of CHWs with poor, moderate, and good knowledge before and after training was done using Fisher’s exact test. Statistical significance was considered based on a two-sided p-value of ≤0.05.

Ethical approval

This cluster-randomised study was approved by the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS-REC-1-2017-070). All CHWs were informed about the aim of the pre- and post-training evaluation and provided written informed consent before participating in the knowledge assessments.

Results

General characteristics of CHWs

Characteristics of the CHWs are summarised in Table 2. The mean (SD) age of CHWs was 37.1 (±8.0) years, with two-thirds aged 35 years or older. All CHWs had attained a secondary level of education, and the majority (72.2%) were females. All CHWs reported having heard about CVDs before the training. The main sources of information about CVDs were radio (83.3%), television (77.8%), and relatives, friends, or neighbours (55.6%). Only 7 CHWs (38.9%) reported receiving information about CVDs through previous health training sessions.

Changes in CVD knowledge

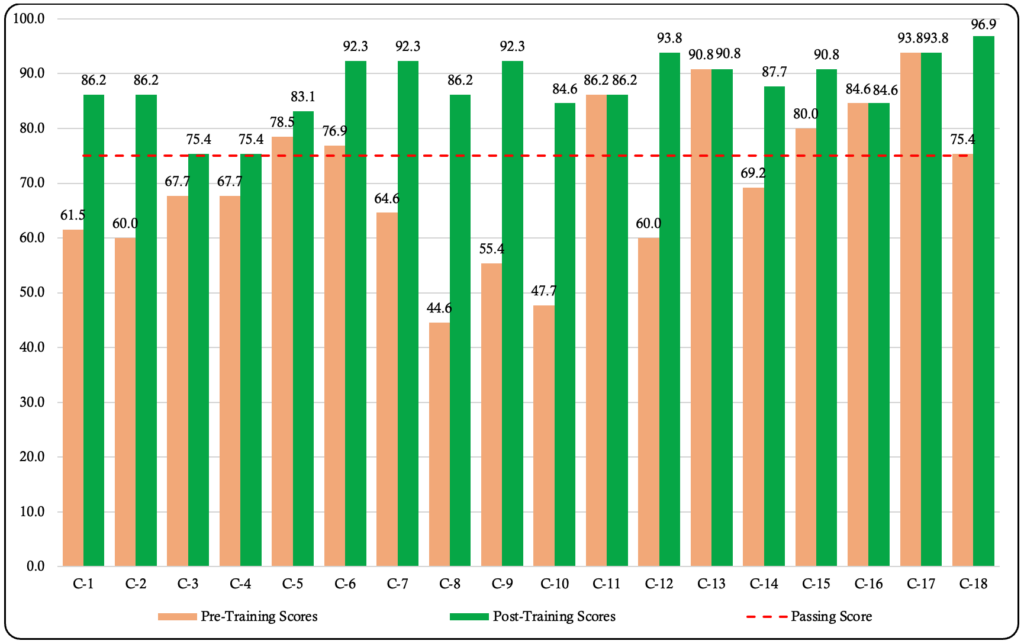

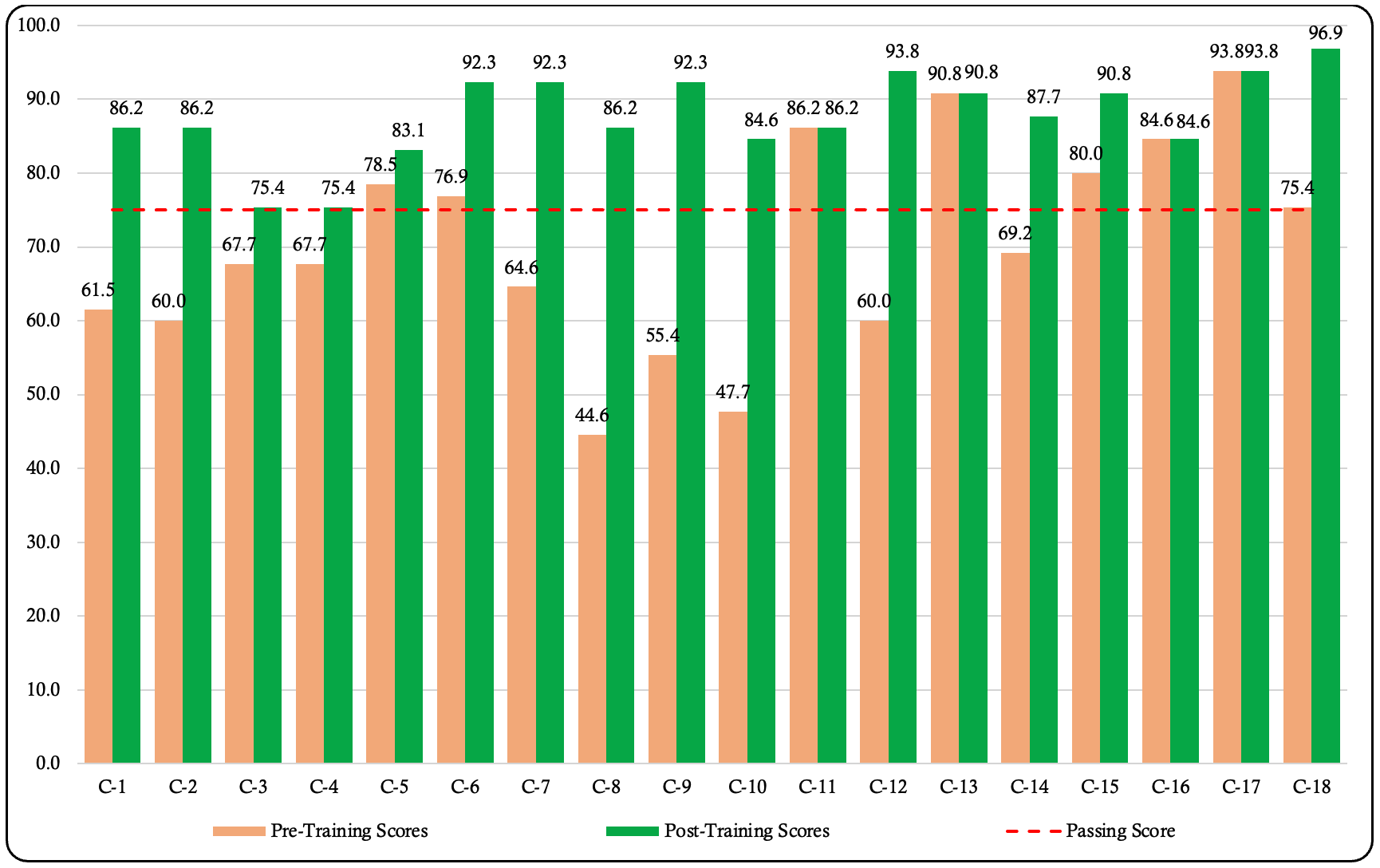

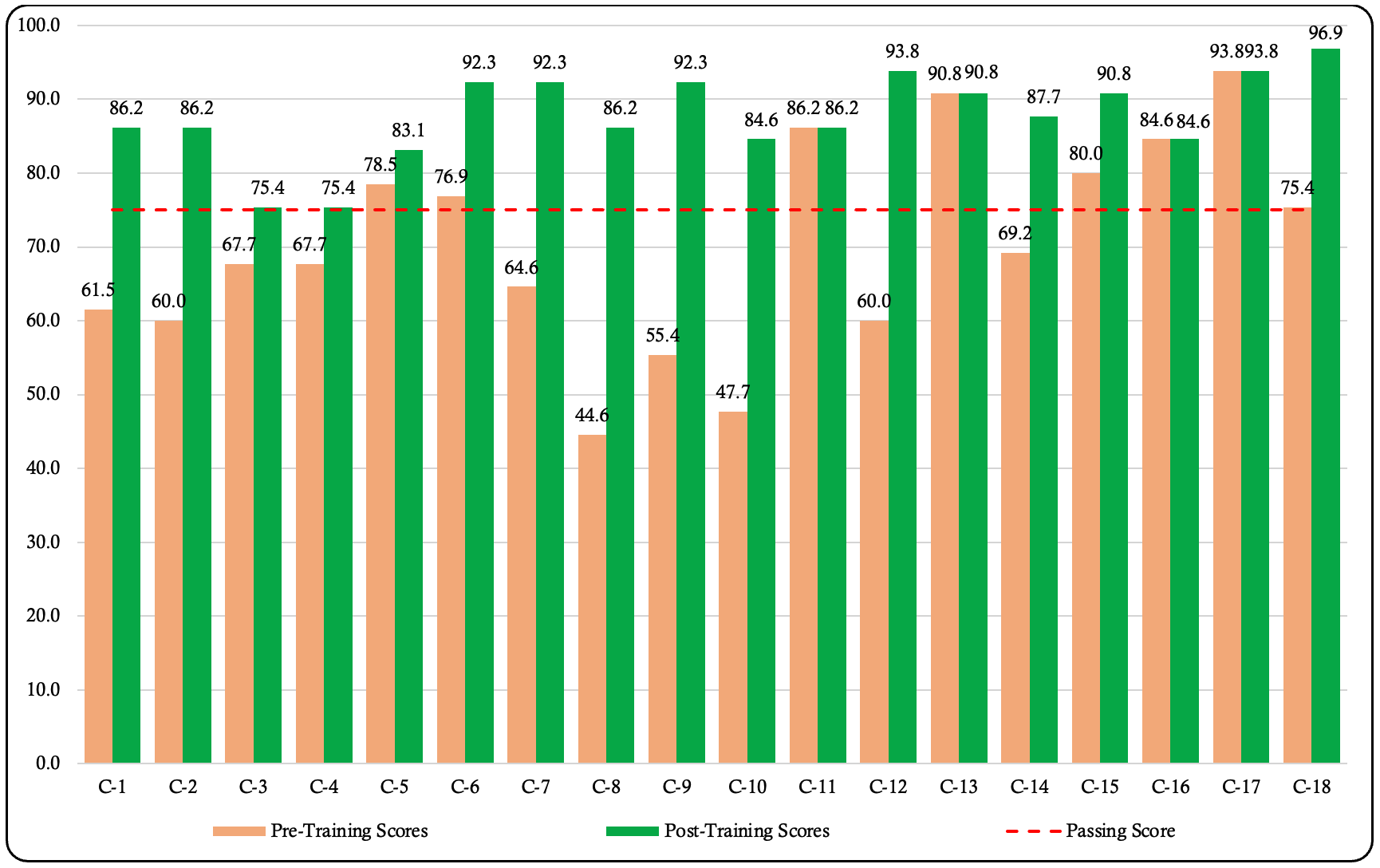

Changes in test scores from the administered questionnaire are presented in Figure 1. During the pre-training assessment, more than half of the CHWs (55.6%) scored below the passing mark. In contrast, all CHWs (100%) scored above the passing mark during the post-training assessment. As shown in Table 3, the mean (SD) test score before training was 70.3 (14.1), which increased to 87.7 (5.9) after the training. The observed mean increase of 24.8% in test scores was statistically significant (p<0.001).

Similarly, the mean (SD) knowledge scores improved significantly across domains (Table 3). The score for knowledge of risk factors increased from 5.9 (±3.0) to 9.6 (±1.0), for warning signs from 4.2 (±2.22) to 8.9 (±0.3), and for healthy dietary habits from 5.2 (±0.7) to 5.9 (±0.3). The combined mean knowledge score for risk factors and warning signs increased from 10.1 (±4.9) to 18.5 (±1.3). All these improvements in knowledge were statistically significant (p<0.001).

Before training, 44.4% of CHWs demonstrated good knowledge of risk factors, 16.7% demonstrated good knowledge of warning signs, and 27.8% demonstrated good knowledge of both risk factors and warning signs for heart attack and stroke. After the training, all CHWs (100%) achieved good knowledge of risk factors and warning signs, representing a remarkable improvement.

CHWs’ knowledge of specific CVD risk factors and warning signs for heart attack and stroke before and after the training is presented in Table 4. Before training, CHWs demonstrated good knowledge of several risk factors for heart attack and stroke, including dyslipidemia (88.9%), obesity/overweight (72.2%), high blood pressure (72.2%), and lack of physical activity (72.2%). For warning signs, CHWs showed good knowledge of dyspnoea (94.4%) and headache (72.2%). CHWs also demonstrated good knowledge regarding healthy dietary habits and the appropriate course of action to take in case of a heart attack and stroke. Although the proportions of CHWs with good knowledge of specific risk factors and warning signs for heart attack and stroke improved following the training, the increase did not reach statistical significance.

Discussion

This study has demonstrated that a short, focused training for CHWs can significantly improve their knowledge of risk factors and warning signs for heart attack and stroke. Additionally, it shows that available training materials can be adapted and used locally to guide CHW training for implementing community-based interventions to reduce high blood pressure and other CVD risk factors.

Before training, only 44.4% of the CHWs scored above the pass mark. Most CHWs reported knowledge of risk factors primarily from radio, television, relatives, friends, and prior health training. The baseline knowledge observed in our study was higher than previously reported in South Africa, where none of the CHWs attained the passing mark [27]. Following the training, all CHWs in our study scored above the passing mark, with mean post-training knowledge scores increasing by 24.8%. This finding aligns with previous studies, where training improved CHWs’ content knowledge and practical skills [28–30]. The reported improvement in content knowledge in other studies ranged from 3% to 40%, with specific increases of 7% in Mexico and 39% in South Africa [26].

Our training lasted 8 hours per day over five days (totaling 40 hours), double the time allocated for training on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases in the Tanzania training guide for community health workers [20]. The duration of training is critical to ensuring that the intended topics are thoroughly covered, discussed, and understood by trainees. It also provides sufficient time for practical sessions to demonstrate the skills acquired. Previous studies on CHWs’ training for CVD prevention and management reported training durations ranging from 2.5 hours to 40 hours [31]. While the training duration alone does not entirely explain post-training knowledge gains, the training duration must match the depth and breadth of the topics to be covered. In the systematic review,[31] the study with the shortest training time (2.5 hours) focused only on health education about physical activity,[32] whereas the study with the longest training duration (40 hours) targeted diabetes education and prevention [29].

The trainee’s baseline knowledge should guide the duration of training, as those with limited understanding may require longer and more comprehensive training sessions. Training and discussions should be conducted in a language well understood by CHWs to enhance effectiveness. Facilitating training in the learners’ language enhances comprehension, encourages participation in discussions, understanding and grasping the intended concepts, and enables them to effectively communicate the same messages during their community health education [33].

The CHW-learning agenda project (CHW-LAP) supported the Ministry of Health (MoH) in Tanzania to develop a framework for implementing a general CHW cadre that would be institutionalized and integrated into the health system for a standardized and sustainable scale-up country-wide [34]. Our findings support the effectiveness of a short, focused training to improve CHWs’ knowledge and practical skills for CVD prevention and control in Tanzania. However, the knowledge and skills acquired must be maintained and strengthened through continuous education and refresher training programs. Such programs are vital, especially in rural settings, to ensure that CHWs provide up-to-date, accurate, and high-quality health education services. Experience from South Africa has shown that in the absence of formal training and regular refresher training, CHWs tend to rely on knowledge passed down from experienced peers, which may not always be accurate [35]. Therefore, regular structured refresher training programs are necessary to standardize and update CHWs’ knowledge across communities.

Our study attempted to evaluate the understanding and skills of CHWs following a training program. It is important to mention that the CHWs included in this study had similar education qualifications to those currently required for the CHW cadre. The training outcome evaluation conducted in our study has policy implications for informing the current CHW training and deployment in Tanzania.

Our study had limitations which should be considered when interpreting the findings. The post-training assessment of knowledge was conducted immediately after the training, when the knowledge gained was still fresh and easy to remember. We did not conduct a follow-up assessment to evaluate knowledge retention after the 12-month intervention period. Additionally, we did not have a control group of CHWs. A control group could have increased the reliability of our results of improved CHWs’ knowledge in relation to the training they received. Lastly, the purpose of the training was to empower CHWs with knowledge and skills to provide health education and healthy lifestyle promotion, and conduct screening for early identification and referral of individuals at high risk for CVD for treatment. Thus, knowledge gained by CHWs in this study may not be comparable to studies that focused on other NCDs or general health.

Conclusion

By adapting training existing material, this study has demonstrated that a short, CVD-specific training for CHWs is feasible and effective in improving their knowledge and skills. Such improvement in knowledge and skills equips CHWs to deliver health education better, promote healthy lifestyles, and conduct community-based screening for early identification of high-risk individuals using simple non-invasive tools. Given the rising burden of CVDs in Tanzania, and in particular rural settings, CHWs present a culturally acceptable and scalable approach to address this public health challenge through health education and healthy lifestyle promotion interventions. Further studies should be conducted to explore the long-term retention of knowledge and skills acquired during the training to inform the timing and contents of the refresher training.

What is already known about the topic

- Cardiovascular diseases such as heart attack and stroke remain a problem of public concern globally, with a higher burden of morbidity and mortality in low-and middle-income countries.

- Despite being largely preventable, CVDs have increased significantly in Africa in recent decades and are projected to continue to rise

- Community-based intervention targeting the reduction of population risk, such as hypertension, smoking and cholesterol, led to a significant decline in CVDs in high-income countries.

- Community interventions implemented by CHWs have also shown promising results in enhancing awareness, promoting self-management and behaviour change.

What this study adds

- The findings of this study demonstrate the effectiveness of a short and focused training on improving knowledge and skills of CHWs necessary for providing health education and conducting community-based screening for early identification of individual risk for CVDs

- Our findings add to the body of existing proof regarding the potential of integrating CHWs in the prevention and control strategies

- The findings provide an opportunity to implement a simple, culturally acceptable and cost-effective approach to combating the rising burden of CVDs, especially in rural settings with limited access to health services.

Funding

Data collection for this study was made possible with financial support from the Bernard Lown Scholars in Cardiovascular Health Program at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (Agreement #BLSCHP-1901) to AM., and the SIDA small grant award from Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences to AA. Funders had no role in the design, data collection, analysis, manuscript preparation, or publication decision. Interpretations and views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the funders.

Authors´ contributions

Conception: AM., MN., and DU.; data collection: AM. and AA.; analysis and interpretation of results: AM. with input from RM. and MN.; writing initial draft of the manuscript: AM.; critical review and revisions: MN., AA., RM., and DU.; and all authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

| Day | Session | Training Contents |

|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Session 1.0 | Opening and Introductions |

| Session 1.1 | Orientation to training and review of the training schedule | |

| Session 1.2 | Pre-training assessment | |

| Session 1.3 | Review of research study and training expectations | |

| Session 1.4 | Definition and overview of major CVDs | |

| Session 1.5 | Definition and overview of modifiable CVD risk factors | |

| Session 1.6 | Definition and overview of non-modifiable CVD risk factors | |

| Day 2 | Session 2.0 | Measurements |

| Session 2.1 | Measuring blood pressure | |

| Session 2.2 | Measuring body weight | |

| Session 2.3 | Measuring body height | |

| Session 2.4 | Practical session | |

| Day 3 | Session 3.0 | CVD Screening Procedures and Interpretation of Results |

| Session 3.1 | Screening for overweight and obesity | |

| Session 3.2 | Screening for hypertension | |

| Session 3.3 | Screening for diabetes | |

| Session 3.4 | Screening for dyslipidemia | |

| Session 3.5 | Assessing and communicating the 10-year risk of developing CVD | |

| Day 4 | Session 4.0 | Health Education and Healthy Lifestyle Promotion |

| Session 4.1 | Deleterious effects of CVD risk factors | |

| Session 4.2 | Ideal/normal body weight | |

| Session 4.3 | Smoking cessation | |

| Session 4.4 | Reduction of excess alcohol drinking | |

| Session 4.5 | Healthy dietary habits | |

| Session 4.6 | Physical exercise and physical activity | |

| Session 4.7 | Health check-ups | |

| Day 5 | Session 5.0 | Effective Communication Skills for Behavior Change |

| Session 5.1 | How to evoke the desire to change behavior | |

| Session 5.2 | Skills and techniques to enable behavior change | |

| Session 5.3 | Providing reasons/rationale for behavior change | |

| Session 5.4 | Explaining the importance/benefits of changing such behavior | |

| Session 5.5 | Supporting and setting goals for individual behavior change | |

| Session 5.6 | Post-training assessment of knowledge and skills | |

| Session 5.7 | Administrative and logistics | |

| Session 5.8 | Questions and answers, conclusions, and final wrap-up |

| Variable | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | ||

| <35 | 6 | 33.3 |

| ≥35 | 12 | 66.7 |

| Sex | ||

| Males | 5 | 27.8 |

| Females | 13 | 72.2 |

| Education level | ||

| Secondary education | 18 | 100.0 |

| Participated in pre- and post-training assessments | ||

| Pre-training assessment | 18 | 100.0 |

| Post-training assessment | 18 | 100.0 |

| Ever heard about CVDs | ||

| Yes | 18 | 100.0 |

| No | 0 | 0.0 |

| Source of information | ||

| Radio (Yes) | 15 | 83.3 |

| Television (Yes) | 14 | 77.8 |

| Health worker (Yes) | 6 | 33.3 |

| Relative/friend/neighbor (Yes) | 10 | 55.6 |

| Previous training (Yes) | 7 | 38.9 |

| Online/Internet (Yes) | 6 | 33.3 |

| Variable | Pre-training | Post-training | Mean or % Change (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Exam Test Score | ||||

| Mean test score | 70.3±4.1 | 87.7±5.9 | 17.4 (10.1, 24.8) | <0.001 |

| Mean Knowledge Scores¶ | ||||

| Mean knowledge score for CVD risk factors | 5.9±3.0 | 9.6±1.0 | 3.7 (2.2, 5.2) | <0.001 |

| Mean knowledge score for CVD warning signs | 4.2±2.2 | 8.9±0.3 | 4.7 (3.6, 5.7) | <0.001 |

| Mean knowledge score for a healthy diet | 5.2±0.7 | 5.9±0.3 | 0.7 (0.3, 1.1) | <0.001 |

| Mean knowledge score for the appropriate action | 5.8±0.5 | 6.0±0.0 | 0.2 (-0.0, 0.5) | 0.095 |

| Overall mean knowledge score | 21.1±5.5 | 30.4±1.3 | 9.3 (6.6, 12.1) | <0.001 |

| Proportion with Good Knowledge‡ | ||||

| Good knowledge of risk factors | 44.4 | 100.0 | 55.6 (26.2, 73.8) | <0.001 |

| Good knowledge of warning signs | 16.7 | 100.0 | 83.3 (55.0, 95.0) | <0.001 |

| Good knowledge of risk factors and warning signs | 27.8 | 100.0 | 72.2 (42.8, 87.2) | <0.001 |

| ¶ Results are presented as mean (standard deviation) ‡ Results are presented as a number (percentage) | ||||

| Variable | Correct Response (%) | % Change (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Training | After Training | |||

| Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Diseases | ||||

| Older age | 61.1 | 94.4 | 33.3 (4.8, 55.2) | 0.016 |

| Obesity/Overweight | 72.2 | 94.4 | 22.2 (-4.0, 44.0) | 0.074 |

| Hypertension | 72.2 | 94.4 | 22.2 (-4.0, 44.0) | 0.074 |

| Dyslipidemia | 88.9 | 100.0 | 11.1 (-8.3, 28.3) | 0.146 |

| Smoking | 44.4 | 100.0 | 55.6 (26.2, 73.8) | <0.001 |

| Excess alcohol consumption | 50.0 | 100.0 | 50.0 (21.1, 68.9) | <0.001 |

| Physical inactivity | 72.2 | 94.4 | 22.2 (-4.0, 44.0) | 0.074 |

| Family history | 44.4 | 88.9 | 44.4 (13.2, 66.8) | 0.005 |

| Stress | 66.7 | 100.0 | 33.3 (7.0, 53.0) | 0.007 |

| Kidney disease | 16.7 | 94.4 | 77.8 (48.1, 91.9) | <0.001 |

| High-fat diet | 100.0 | 94.4 | -5.6 (-21.3, 11.3) | 0.310 |

| Warning Signs for Cardiovascular Diseases | ||||

| Headache | 72.2 | 100.0 | 22.8 (2.8, 47.2) | 0.016 |

| Chest pain | 27.8 | 100.0 | 72.2 (42.8, 87.2) | <0.001 |

| Dyspnea/difficulty in breathing | 94.4 | 100.0 | 5.6 (-11.3, 21.3) | 0.310 |

| Sweating | 50.0 | 94.4 | 44.4 (14.4, 65.6) | 0.003 |

| Vomiting | 5.6 | 100.0 | 94.4 (68.7, 100.0) | <0.001 |

| Pain in the teeth/jaw | 0.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 (76.5, 100.0) | <0.001 |

| Painful shoulder/hand | 50.0 | 100.0 | 50.0 (21.1, 68.9) | <0.001 |

| Loss of consciousness | 66.7 | 100.0 | 33.3 (7.0, 53.0) | 0.007 |

| Dizziness or lightheadedness | 55.6 | 100.0 | 38.9 (9.5, 60.5) | 0.007 |

References

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2025 Jul 31 [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds).

- Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, Addolorato G, Ammirati E, Baddour LM, Barengo NC, Beaton AZ, Benjamin EJ, Benziger CP, Bonny A, Brauer M, Brodmann M, Cahill TJ, Carapetis J, Catapano AL, Chugh SS, Cooper LT, Coresh J, Criqui M, DeCleene N, Eagle KA, Emmons-Bell S, Feigin VL, Fernández-Solà J, Fowkes G, Gakidou E, Grundy SM, He FJ, Howard G, Hu F, Inker L, Karthikeyan G, Kassebaum N, Koroshetz W, Lavie C, Lloyd-Jones D, Lu HS, Mirijello A, Temesgen AM, Mokdad A, Moran AE, Muntner P, Narula J, Neal B, Ntsekhe M, Moraes De Oliveira G, Otto C, Owolabi M, Pratt M, Rajagopalan S, Reitsma M, Ribeiro ALP, Rigotti N, Rodgers A, Sable C, Shakil S, Sliwa-Hahnle K, Stark B, Sundström J, Timpel P, Tleyjeh IM, Valgimigli M, Vos T, Whelton PK, Yacoub M, Zuhlke L, Murray C, Fuster V. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019. J Am Coll Cardiol [Internet]. 2020 Dec 22 [cited 2025 Dec 29];76(25):2982–3021. Available from: https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010.

- Mensah G, Roth G, Sampson U, Moran A, Feigin V, Forouzanfar M, Naghavi M, Murray C. Mortality from cardiovascular diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis of data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013: cardiovascular topic. Cardiovasc J Afr [Internet]. 2015 Apr 30 [cited 2025 Dec 29];26(2):S6–10. Available from: https://www.cvja.co.za/onlinejournal/vol26/vol26_issue2_supplement/#8/z doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2015-036.

- Laatikainen T, Critchley J, Vartiainen E, Salomaa V, Ketonen M, Capewell S. Explaining the decline in coronary heart disease mortality in Finland between 1982 and 1997. Am J Epidemiol [Internet]. 2005 Oct 15 [cited 2025 Dec 29];162(8):764–73. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/aje/article/162/8/764/122427 doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi274.

- Koopman C, Vaartjes I, van Dis I, Verschuren WMM, Engelfriet P, Heintjes EM, Blokstra A, Deutekom AW, Wilhelminapark 1, Bots ML. Explaining the Decline in Coronary Heart Disease Mortality in the Netherlands between 1997 and 2007. PLoS One [Internet]. 2016 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Dec 29];11(12):e0166139. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0166139 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166139.

- Gouda HN, Charlson F, Sorsdahl K, Ahmadzada S, Ferrari AJ, Erskine H, Leung J, Santamauro D, Lund C, Aminde LN, Mayosi BM, Kengne AP, Harris MG, Whiteford HA. Burden of non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, 1990–2017: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Glob Health [Internet]. 2019 Oct [cited 2025 Dec 29];7(10):e1375–87. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(19)30374-2/fulltext doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30374-2.

- Chong B, Jayabaskaran J, Jauhari SM, Chan SP, Goh R, Kueh MTW, Sivapragasam V, Kong G, Ong MEH, Yeo TC, Lim YL, Chew NWS, Foo R. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: projections from 2025 to 2050. Eur J Prev Cardiol [Internet]. 2024 Aug 25 [cited 2025 Dec 29];32(11):1001–1015. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/eurjpc/article/32/11/1001/7756567 doi: 10.1093/eurjpc/zwae281.

- Mendoza W, Miranda JJ. Global shifts in cardiovascular disease, the epidemiologic transition and other contributing factors: Toward a new practice of Global Health Cardiology. Cardiol Clin [Internet]. 2017 Feb [cited 2025 Dec 29];35(1):1–12. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0733865116300760 doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2016.08.004.

- Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD Compare: Tanzania Mortality [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/.

- Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Tanzania Country Profile [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/health-by-location/profiles/tanzania.

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases country profiles 2018. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2018 Sep 24 [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/ncd-country-profiles-2018.

- Mayige M, Kagaruki G, Ramaiya K, Swai A. Non communicable diseases in Tanzania: a call for urgent action. Tanzan J Health Res [Internet]. 2012 Mar 26 [cited 2025 Dec 29];13(5). Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/thrb/article/view/71079 doi: 10.4314/thrb.v13i5.7.

- Muhamedhussein MS, Nagri ZI, Manji KP. Prevalence, risk factors, awareness, and treatment and control of hypertension in mafia island, tanzania. Int J Hypertens [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2025 Dec 29];2016:1–5. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ijhy/2016/1281384/ doi: 10.1155/2016/1281384.

- Miassi YE, Dossa FK, Zannou O, Akdemir Ş, Koca I, Galanakis CM, Alamri AS. Socio-cultural and economic factors affecting the choice of food diet in West Africa: a two‑stage Heckman approach. Discov Food [Internet]. 2022 Dec [cited 2025 Dec 29];2(1):16. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s44187-022-00017-5 doi: 10.1007/s44187-022-00017-5.

- Unal B, Critchley JA, Capewell S. Explaining the decline in coronary heart disease mortality in england and wales between 1981 and 2000. Circulation [Internet]. 2004 Mar 9 [cited 2025 Dec 29];109(9):1101–7. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/01.CIR.0000118498.35499.B2 doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118498.35499.B2.

- Gilmore B, McAuliffe E. Effectiveness of community health workers delivering preventive interventions for maternal and child health in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2013 Dec [cited 2025 Dec 29];13(1):847. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-13-847 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-847.

- Abdel-All M, Putica B, Praveen D, Abimbola S, Joshi R. Effectiveness of community health worker training programmes for cardiovascular disease management in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2017 Nov 3 [cited 2025 Dec 29];7(11):e015529. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/7/11/e015529 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015529.

- Miles A, Reeve MJ, Grills NJ. Effectiveness of community health worker-delivered interventions on non-communicable disease risk and health outcomes in India: A systematic review. Christian Journal for Global Health [Internet]. 2020 Dec 21 [cited 2025 Dec 29];7(5):31–51. Available from: https://cjgh.org/articles/10.15566/cjgh.v7i5.439 doi: 10.15566/cjgh.v7i5.439.

- Ministry of Health Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children (Tanzania). National strategic plan for prevention and control of non-communicable diseases 2021-2026. Dodoma (Tanzania): Ministry of Health Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children; [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: https://tzdpg.or.tz/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/NCD-ACTION-PLAN-2021-2026.pdf.

- Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children (Tanzania). The Guide for Training Community Health Workers [Internet]. Dodoma (Tanzania): Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children; 2021 Dec [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: https://hssrc.tamisemi.go.tz/storage/app/uploads/public/636/23b/e41/63623be411cb9867015115.pdf.

- Tani K, Exavery A, Baynes CD, Pemba S, Hingora A, Manzi F, Phillips JF, Kanté AM. Unit cost analysis of training and deploying paid community health workers in three rural districts of Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2016 Jul 8 [cited 2025 Dec 29];16(1):237. Available from: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-016-1476-5 doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1476-5.

- Narh‐Bana SA, Chirwa TF, Mwanyangala MA, Nathan R. Adult deaths and the future: a cause‐specific analysis of adult deaths from a longitudinal study in rural Tanzania 2003–2007. Trop Med Int Health [Internet]. 2012 Sep 14 [cited 2025 Dec 29];17(11):1396–404. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03080.x doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03080.x.

- World Health Organization. Strengthening health workforce capacity in the Pacific [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2009 [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: http://www.wpro.who.int/philippines/publications/trainersguide.pdf?ua=1.

- Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (Tanzania). Curriculum for Basic Technician Certificate in Community Health (NTA Level 4) [Internet]. Dar es Salaam (Tanzania): Ministry of Health and Social Welfare; 2015 [cited 2025 Dec 29].

- Risk Charts. Globorisk [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: http://www.globorisk.org/risk-charts.

- Abrahams-Gessel S, Denman CA, Montano CM, Gaziano TA, Levitt N, Rivera-Andrade A, Carrasco DM, Zulu J, Khanam MA, Puoane T. The training and fieldwork experiences of community health workers conducting population-based, noninvasive screening for cvd in lmic. Glob Heart [Internet]. 2015 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Dec 29];10(1):45. Available from: https://www.globalheartjournal.com/article/S2211-8160(14)02735-5/fulltext doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.12.008.

- Puoane T, Abrahams-Gessel S, Gaziano TA, Levitt N. Training community health workers to screen for cardiovascular disease risk in the community: experiences from Cape Town, South Africa. Cardiovasc J Afr [Internet]. 2017 Jun 23 [cited 2025 Dec 29];28(3):170–5. Available from: https://www.cvja.co.za/onlinejournal/vol28/vol28_issue3/#36/z doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2016-077.

- Sangprasert P. The Effects of a Training Program for the Development of Hypertension Knowledge and Basic Skills Practice (HKBSP) for Thai Community Healthcare Volunteers. Siriraj Med J [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2025 Dec 29];63:163–7. Available from: https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/sirirajmedj/article/view/241000/164231.

- Sranacharoenpong K, Hanning RM. Diabetes prevention education program for community health care workers in Thailand. J Community Health [Internet]. 2011 Oct 5 [cited 2025 Dec 29];37(3):610–8. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10900-011-9491-2 doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9491-2.

- Gaziano TA, Abrahams-Gessel S, Denman CA, Montano CM, Khanam M, Puoane T, Levitt NS. An assessment of community health workers’ ability to screen for cardiovascular disease risk with a simple, non-invasive risk assessment instrument in Bangladesh, Guatemala, Mexico, and South Africa: an observational study. Lancet Glob Health [Internet]. 2015 Jul 14 [cited 2025 Dec 29];3(9):e556–63. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(15)00143-6/fulltext doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00143-6.

- Ogungbe O, Byiringiro S, Adedokun-Afolayan A, Seal SM, Dennison Himmelfarb CR, Davidson PM, Commodore-Mensah Y. Medication adherence interventions for cardiovascular disease in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence [Internet]. 2021 Apr 29 [cited 2025 Dec 29];15:885–97. Available from: https://www.dovepress.com/medication-adherence-interventions-for-cardiovascular-disease-in-low—peer-reviewed-fulltext-article-PPA doi: 10.2147/PPA.S296280.

- Seyed Emami R, Eftekhar Ardebili H, Golestan B. Effect of a Health Education Intervention on Physical Activity Knowledge, Attitude and Behavior in Health Volunteers. Journal of Hayat [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2025 Dec 29];16(3 and 4):48-55. Available from: http://hayat.tums.ac.ir/article-1-78-en.html.

- Rivombo AM. A study of the challenges of adult learning facilitation in a diverse setting with special reference to Soshanguve [master’s thesis on Internet]. Pretoria (South Africa): University of South Africa; 2014 [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: https://uir.unisa.ac.za/server/api/core/bitstreams/9a3f09a5-310b-4ad5-be8e-820781e47eb2/content.

- Abdullah H. Baqui. Learning Agenda Project for CHWs [Internet]. Baltimore (Maryland): John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: https://publichealth.jhu.edu/institute-for-international-programs/our-work/past-projects/health-research-challenge-for-impact-hrci.

- Tsolekile LP, Puoane T, Schneider H, Levitt NS, Steyn K. The roles of community health workers in management of non-communicable diseases in an urban township. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med [Internet]. 2014 Nov 21 [cited 2025 Dec 29];6(1). Available from: https://phcfm.org/index.php/phcfm/article/view/693 doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v6i1.693.