Research | Open Access | Volume 9 (1): Article 09 | Published: 13 Jan 2026

Myopia awareness and preferences for myopia information: Perception of basic school children in the Kumasi Metropolis and Bekwai Municipality, Ghana

Menu, Tables and Figures

Navigate this article

Tables

| Demographic factor | Number of school children (n=1420) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| District | ||

| Kumasi Metropolis | 1,092 | 76.9 |

| Bekwai Municipality | 328 | 23.1 |

| Age group (years) | ||

| ≤9 | 12 | 0.9 |

| 10–14 | 1,075 | 75.7 |

| 15–19 | 333 | 23.5 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 646 | 45.5 |

| Female | 774 | 54.5 |

| School grade | ||

| Upper primary (4–6) | 209 | 14.7 |

| Junior High School | 1,211 | 85.3 |

| School type | ||

| Government | 956 | 67.3 |

| Mission | 464 | 32.7 |

| Difficulty seeing at far (n=1,408) | ||

| Yes | 558 | 39.6 |

| No | 850 | 60.4 |

| Relative has difficulty seeing at far (n=1,411) | ||

| Yes | 577 | 40.9 |

| No | 382 | 27.1 |

| Don’t know | 452 | 32.0 |

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants

| Characteristics | Myopia Awareness | Crude OR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||

| Age | 342 | 1056 | 1.21 (1.12, 1.33) | <0.001 | 1.17 (1.10, 1.31) | 0.003* |

| District | ||||||

| Kumasi | 218 | 866 | 0.40 (0.30, 0.52) | <0.001 | 0.26 (0.19, 0.37) | <0.001* |

| Bekwai | 124 | 190 | Reference | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 148 | 489 | 0.90 (0.70, 1.15) | 0.376 | 0.89 (0.69, 1.16) | 0.393 |

| Female | 194 | 567 | Reference | |||

| School grade | ||||||

| Junior High School | 297 | 892 | 1.19 (0.84, 1.70) | 0.332 | 0.76 (0.48, 1.19) | 0.235 |

| Upper Primary | 45 | 164 | Reference | |||

| School type | ||||||

| Mission | 148 | 307 | 1.89 (1.47, 2.44) | <0.001 | 3.11 (2.31, 4.18) | <0.001* |

| Government | 194 | 749 | Reference | |||

| Difficulty seeing at far | ||||||

| Yes | 157 | 394 | 1.42 (1.11, 1.82) | 0.005 | 1.47 (1.13, 1.91) | 0.004* |

| No | 184 | 653 | Reference | |||

| Relative has difficulty seeing at far | ||||||

| Yes | 146 | 420 | 1.00 (0.75, 1.35) | 0.976 | 1.14 (0.83, 1.57) | 0.409 |

| Don’t know | 96 | 354 | 0.78 (0.57, 1.08) | 0.134 | 0.93 (0.66, 1.31) | 0.675 |

| No | 97 | 277 | Reference | |||

| Constant | 0.07 (0.02, 0.28) | <0.001 | ||||

* Statistically significant

Table 2: Factors associated with myopia awareness among school children

| Factor | Sample (N) | Median (IQR) | Mean rank | Mann Whitney | Kruskal Wallis (χ²) statistic | p-value | Effect size (r) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| u-statistics | z-statistic | |||||||

| District | 324 | |||||||

| Bekwai Municipal | 117 | 26 (24, 29) | 136.94 | 15099.50 | 3.70 | <0.001* | 0.21 | |

| Kumasi Metropolis | 207 | 29 (25, 32) | 176.94 | |||||

| Gender | 324 | |||||||

| Male | 142 | 28 (24, 32) | 159.40 | 12529.50 | -0.47 | 0.638 | ||

| Female | 182 | 28 (25, 32) | 164.66 | |||||

| School grade | 324 | |||||||

| Upper primary | 39 | 26 (23, 28) | 126.79 | 6950.00 | 2.54 | 0.011* | 0.17 | |

| Junior High School | 285 | 28 (25, 32) | 167.39 | |||||

| School type | 324 | |||||||

| Government | 180 | 27 (24, 31) | 153.25 | 14625.50 | 1.99 | 0.046* | 0.11 | |

| Mission | 144 | 29 (25, 32) | 174.07 | |||||

| Difficulty seeing at far | 323 | |||||||

| Yes | 148 | 28 (25, 31) | 159.31 | 12552.00 | -0.48 | 0.633 | ||

| No | 175 | 28 (25, 32) | 164.27 | |||||

| Age group | 324 | 10.00 | 0.007* | |||||

| ≤9 | 6 | 25 (25, 26) | 98.83 | |||||

| 10–14 | 228 | 28 (25, 32) | 172.52 | |||||

| 15–19 | 90 | 27 (24, 30) | 141.36 | |||||

| Dunn’s post-hoc test with significance values adjusted by the Bonferroni correction for multiple tests | ||||||||

| Sample 1-Sample 2β | Test Statistic | Std. Error | Std. Test Statistic | Sig. | Adj. Sig.# | |||

| ≤9 vs 15–19 | -42.522 | 39.424 | -1.079 | 0.281 | 0.842 | |||

| ≤9 vs 10–14 | -73.689 | 38.672 | -1.905 | 0.057 | 0.170 | |||

| 15–19 vs 10–14 | 31.166 | 11.640 | 2.678 | 0.007* | 0.022* | |||

β Each row tests the null hypothesis that the Sample 1 and Sample 2 distributions are the same.

# Significance adjusted by Bonferroni correction for multiple tests.

* Statistically significant.

χ²: Chi-square.

Table 3: Median scores for myopia knowledge compared with participant factors

| Characteristics | Myopia Knowledge | Crude OR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inadequate | Adequate | |||||

| Age | 23 | 301 | 0.70 (0.50, 1.00) | 0.043 | 0.71 (0.48, 1.05) | 0.085 |

| District | ||||||

| Kumasi | 14 | 193 | 1.15 (0.48, 2.74) | 0.755 | 0.68 (0.24, 1.95) | 0.476 |

| Bekwai | 9 | 108 | Reference | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 11 | 131 | 0.84 (0.36, 1.97) | 0.689 | 0.87 (0.36, 2.11) | 0.756 |

| Female | 12 | 170 | Reference | |||

| School grade | ||||||

| Junior High School | 22 | 263 | 0.32 (0.04, 2.40) | 0.265 | 0.74 (0.08, 7.21) | 0.798 |

| Upper Primary | 1 | 38 | Reference | |||

| School type | ||||||

| Mission | 7 | 137 | 1.91 (0.76, 4.78) | 0.167 | 2.23 (0.78, 6.36) | 0.134 |

| Government | 16 | 164 | Reference | |||

| Difficulty seeing at far | ||||||

| Yes | 9 | 139 | 1.34 (0.56, 3.20) | 0.505 | 1.38 (0.56, 3.42) | 0.487 |

| No | 14 | 161 | Reference | |||

| Relative has difficulty seeing at far | ||||||

| Yes | 9 | 127 | 1.16 (0.42, 3.24) | 0.774 | 1.07 (0.37, 3.11) | 0.906 |

| Don’t know | 7 | 86 | 1.01 (0.34, 3.01) | 0.983 | 1.12 (0.36, 3.47) | 0.842 |

| No | 7 | 85 | Reference | |||

| Constant | 1727.579 | 0.007 | ||||

Table 4: Factors associated with myopia knowledge among the participants

Figures

Keywords

- Myopia

- Myopia awareness

- Children’s perception

Sylvester Kyeremeh1,&, Khathutshelo Percy Mashige1, Kovin Shunmugan Naidoo1

1Discipline of Optometry, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

&Corresponding author: Sylvester Kyeremeh, Discipline of Optometry, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa, Email: sylvester.kyeremeh@knust.edu.gh, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7916-0175

Received: 20 Jul 2025, Accepted: 08 Jan 2026, Published: 13 Jan 2026

Domain: School Health

Keywords: Myopia, myopia awareness, children’s perception

©Sylvester Kyeremeh et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Sylvester Kyeremeh et al., Myopia awareness and preferences for myopia information: Perception of basic school children in the Kumasi Metropolis and Bekwai Municipality, Ghana. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025; 9(1):09. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00162

Abstract

Introduction: Childhood myopia prevalence remains high across the globe, with its development and progression closely linked to environmental and lifestyle factors. Protective lifestyle modification, among children, depends on the dissemination and acquisition of accurate myopia information. Hence, understanding myopia awareness level among children and their preferred modes of receiving myopia information are critical for the design of an effective awareness programme. The current study determined the current level of myopia awareness among basic school children and their preferred methods of myopia awareness creation.

Methods: An analytical cross-sectional survey of primary school children from the Kumasi Metropolis and Bekwai Municipality in the Ashanti region of Ghana was conducted using a two-staged cluster sampling technique. Self-administered, pretested semi-structured questionnaire was used to assess myopia awareness and the preferred method of myopia awareness creation. A response of “yes” to the question, “Have you heard about myopia?” indicated awareness. Binary logistic regression was used to examine the relationship of myopia awareness with demographic factors. A p-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant at a 95% confidence level.

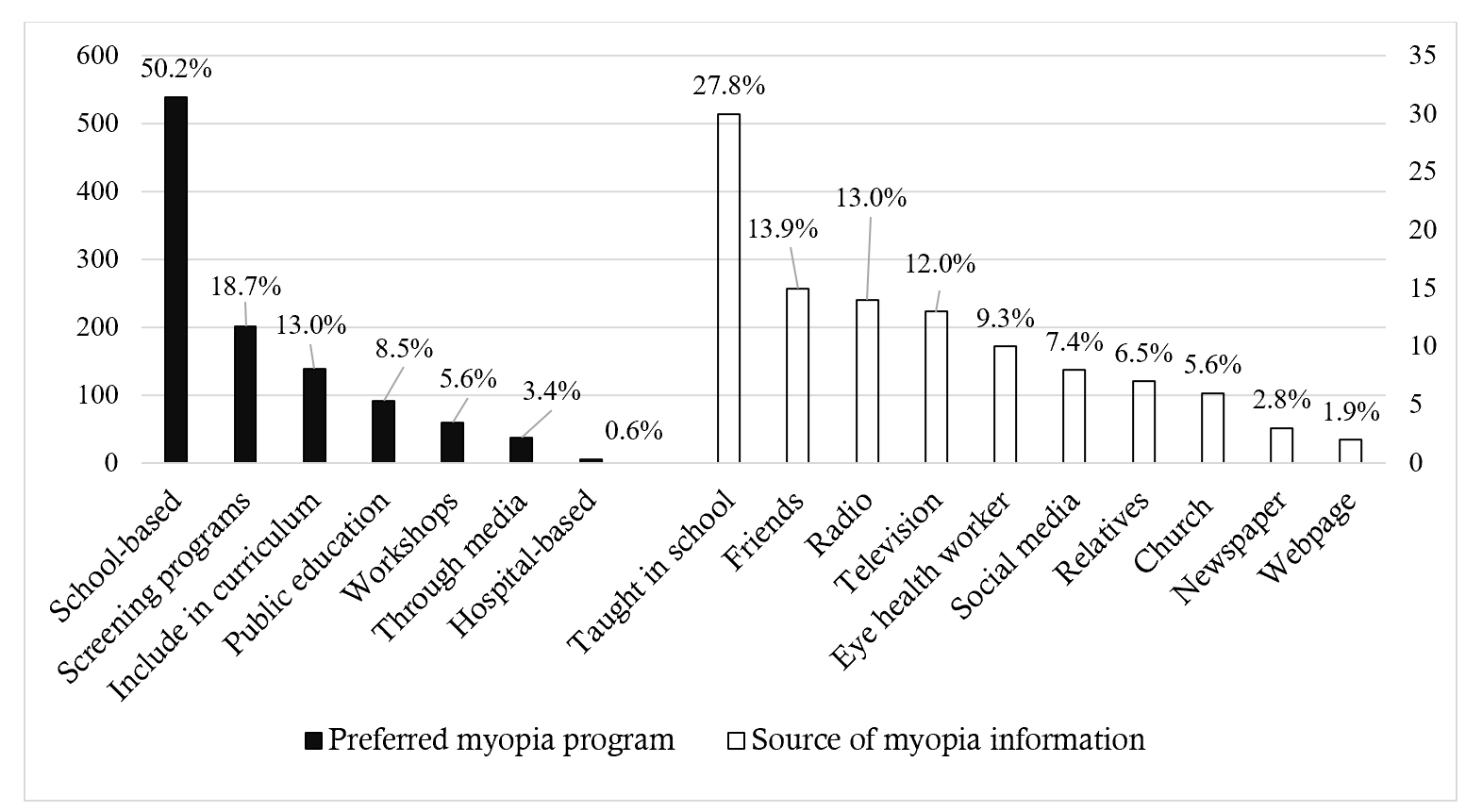

Results: A total of 1420 school children with a mean (SD) age of 13.4 (±1.5) years participated in the study, with the majority being females, 774 (54.5%). Of the 1398 participants responding to myopia awareness questions, 342 (24.5%) reported having heard of myopia. Myopia awareness was significantly associated with age (aOR:1.17, 95%Confidence Interval (95%CI):1.06-1.31, p=0.003), district of residence (aOR=0.26, 95%CI:0.19-0.37, p<0.001), school type (aOR=3.11, 95%CI:2.31-4.18, p<0.001) and difficulty with distance vision (aOR=1.47, 95%CI: 1.13-1.91, p=0.004). Of the 1340 participants who answered questions about the need for a myopia awareness programme, 1243(92.8%) indicated support. Approximately half of the participants, 539 (50.2%), recommended that the awareness programme should be school-based, whereas 6 (0.56%) advocated for a hospital-based approach.

Conclusion: Myopia awareness remains low among basic school children, with the majority supporting the implementation of a school-based awareness creation program.

Introduction

Myopia represents a significant public health challenge worldwide, necessitating the development of effective interventions. Globally, the prevalence of myopia has surged from 22.9% in 2000 to an estimated 34% in 2020 [1]. Projections indicate that by 2050, approximately 4.8 billion individuals globally will be affected, with 10% of these progressing to high myopia, which is associated with increased risk of severe ocular complications, such as retinal detachment, glaucoma, and macular degeneration [2]. However, the prevalence of myopia exhibits significant variability, influenced by demographic, racial and geographical factors. In East and Southeast Asia, prevalence rates can reach up to 90% among young adults [3-5]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis confirmed a substantial and potentially worsening epidemic of childhood myopia in China [6]. The study reported that childhood myopia increased from 2.6% in ages 0-4 years to 67.2% in those aged 15-19 years, with high myopia increasing steadily from 0.1% to 9.5% [6]. Similarly, a cross-sectional study of 20,527 Hong Kong children found a stable prevalence rate of 23.5-24.9% from 2015 to 2019, but a drastic rise to 28.8% in 2020 and 36.2% in 2021 [7]. Comparable studies in Europe also reported prevalence from 11.9% to 49.7% with 5.5% of children aged 6-11 years, 25.2% of adolescents (12-17years) and 24.3% of adults (18-39 years) affected [8]. In the United States, a projected prevalence rate of up to 42% over a 30 year period was reported in a recent reappraisal, highlighting the contribution of adult-onset myopia [9].

In Africa, while myopia prevalence follows the global increasing trend, it remains comparatively low (10), with rates of 4.7% in children [10] and 11.4% in adults reported [11]. Estimated prevalence across the African regions is notably highest in the Northern {6.8% (95% CI: 4.0%–10.2%}), followed by Southern (6.3% {95% CI: 3.9%–9.1%}), Eastern (4.7% {95% CI: 3.1%–6.7%}) and Western (3.5% {95% CI: 1.9%–6.3%}) Africa (12). Childhood myopia prevalence is projected to increase in urban settings and older children to 11.1% and 10.8% by 2030, 14.4% and 14.1% by 2040 and 17.7% and 17.4% by 2050, respectivel,; indicating marginally higher prevalence rates than projected in the overall population (16.4% by 2050) [12].

In Ghana, the increasing trend of myopia has become a concern as it is reportedly surpassing other refractive errors [13, 14]. Among school children, prevalence rates range from 1.7 to 3.4% [15, 16], whereas up to 54.12% is reported from a recent review of patient records [17]. The consistently increasing trend of myopia strongly proves that the relatively low prevalence rates in Africa do not indicate immunity of the continent to the myopia issue. It is also a reflection of a continuous increase in exposure to risk factors. Should current trends persist, myopia prevalence in Africa is projected to increase from 7% to 28% by 2050 [2]. Consequently, adopting a preventive lifestyle, particularly among children, could help reverse current trends and also serve as an economically relevant early intervention.

Research confirms the significant impact of environmental and lifestyle factors on the development and progression of myopia among children [18]. Prolonged near work, extended use of digital screens, and decreased outdoor time are prominent risk factors [18, 19]. A decrease in outdoor activity and an increase in screen time have been associated with a marked rise in myopia prevalence, among Asian populations, following the COVID-19 pandemic [20-22]. These trends highlight the significant role of environmental factors in the growing myopia epidemic and underscore the urgent need for the implementation of preventive lifestyle modifications [18, 19].

Protective lifestyle modifications are fundamentally dependent on awareness and knowledge dissemination. Insufficient efforts in awareness creation and a lack of knowledge can significantly increase susceptibility to myopia consequences. It is therefore essential to implement timely, relevant and acceptable awareness interventions, particularly in Africa, with children as the primary target group. However, there is currently no clear evidence regarding the level of children’s myopia awareness and their preferred modes of information delivery across Africa, particularly in Ghana. This complicates the development of targeted programmes that effectively capture children’s interest and ensure their engagement. This study, therefore, determined the current level of myopia awareness among basic school children and their preferred methods of myopia awareness creation. Findings of the study would provide valuable insights for designing and implementing effective public health interventions to promote positive lifestyle practices that mitigate myopia development and progression, particularly among children in Africa.

Methods

Study design and setting

An analytical cross-sectional survey design, involving only available participants, was utilised over a three-month duration. This design facilitated the examination of multiple outcome variables, and its inherent simplicity rendered it well-suited for the study [23]. The study included basic school children from two districts in Ghana: the Kumasi Metropolis, an urban area, and the Bekwai Municipality, a comparatively suburban area. Typically, basic school children in Ghana are aged 4 to 14 years [24]. School grades in basic education in Ghana consist of kindergarten (KG), primary (1-6), and junior high schools (1-3). English is the official medium of instruction, though students may also be taught in local languages [25-27]. Public schools at the district level are clustered into circuits, which are managed by the Ghana Education Service (GES) directorates. At the time of the study, there were 14 circuits within the Kumasi Metropolis with a total enrolment of 51,472 pupils, and 10 circuits within the Bekwai Municipality with 32,402 enrolled students, as reported by the respective directorates. To facilitate independent and accurate responses, only students from upper primary (Primary 4 to 6) and junior high schools were included, as they are generally more mature. Students who were unable to read the questionnaire independently or comprehend the questions, even after receiving guidance from trained research assistants, were excluded to avoid inaccurate responses.

Sample size determination and sampling technique

A two-stage cluster sampling technique was employed, wherein the 14 circuits within the Kumasi Metropolis were stratified into five clusters based on geographic proximity and shared demographic characteristics. Similarly, the circuits within the Bekwai Municipality were grouped into three clusters using the same criteria. Within these clusters, schools that granted permission for the study were visited, and eligible pupils present at the time of data collection were randomly selected for inclusion in the study.

The minimum required sample size was calculated using Cochran’s formula:

$$N = \frac{Z^2 p q}{e^2}$$

where Z is z-value at a 95% confidence interval, being 1.96, p is the estimated proportion of myopia in the population, taken as 0.5 for maximum variability, and e is the margin of error, set at 0.05, q = 1-p

$$ n = \frac{1.96^2 \times 0.5 \times 0.5}{0.05^2} ≈ 384$$

Specific sample sizes were determined for each district (Kumasi Metropolis and Bekwai Municipality) by adjusting for each district’s total enrolment as follows:

$$ n_x = \frac{n}{1 + \frac{n – 1}{N}} $$

where nx is the specific sample size for the respective district, n is calculated sample and N is the pupil’s enrolment for each district.

For Kumasi Metropolis

$$

\text{sample size} =

\frac{384}{1 + \frac{384 – 1}{51{,}472}}

= 381.16 \approx 381

$$

Non-response rate of 10% = 0.1*381 = 38.1 ≈ 38+381 = 419

For Bekwai Municipality

$$

\text{Sample size} =

\frac{384}{1 + \frac{384 – 1}{32{,}402}}

= 379.45 \approx 379

$$

Non-response rate of 10% = 0.1*379 = 37.9 ≈ 38+379 = 417

Total sample size for both districts = 419 + 417 = 836

Data collection tools and data collection procedure

Semi-structured questionnaires were developed and pretested among 20 participants, prior to administration. The feedback was utilised to revise and reword the questions for clarity and easy comprehension. Additionally, this process facilitated the inclusion of only relevant closed-ended and open-ended questions and was organised into five sections: demographic information (district, gender, age, school grade, type of school), previous ocular history, myopia awareness, knowledge about myopia and participation in routine activities. Research assistants, who were final-year Doctor of Optometry students, were trained to assist participants in completing the questionnaires to ensure accurate responses. They provided explanations when necessary to mitigate biases and avoid misinterpretations. The reliability of the tool was ensured through the selection of an appropriate study population and the inclusion of only relevant questions aligned with the study objectives. A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.651 and a mean inter-item correlation (MIIC) of 0.189 confirmed an acceptable internal consistency and adequate homogeneity among test items without redundancy [28-30]. The questionnaires were hand-delivered to the students by the trained research assistants.

Data management and statistical analysis

Data were entered into Microsoft Excel (2021 version), cleaned, and subsequently exported for analysis using Stata (version 17, StataCorp LLC) and IBM SPSS Statistics (version 27). Similar open-ended responses were thematically categorised and analysed quantitatively. Descriptive statistics, including frequency tables, measures of central tendency, percentages, and graphical representations, were employed. The Pearson chi-square test was used to determine statistical significance for differences in categorical variables. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests were conducted to evaluate the normality of data distribution. For comparisons between two independent groups, the Mann-Whitney U test was applied. The independent-samples Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess statistical differences across more than two groups, with Dunn’s post hoc test employed to determine significant contributing groups. Binary logistic regression was performed to determine the impact of demographic factors on myopia awareness among participants. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test was used to evaluate the model’s calibration, with a non-significant result (p>0.05) was considered acceptable model fit. Multicollinearity was assessed using variance inflation factor (VIF). A mean VIF <5 was considered absence of multicollinearity. Myopia awareness was determined by asking participants whether they had heard of myopia; those responding ‘yes’ were classified as aware, while those responding ‘no’ were categorised as unaware. Knowledge of myopia among aware participants was assessed using an 8-item Likert scale. The Likert scale had 5 grading levels: strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree and strongly disagree and were coded 5,4,3,2 and 1 respectively for positively directed statements, while negatively directed statements were reverse coded using the same grading. Myopia knowledge comprised myopia definition, symptoms, treatment and impact, which were framed into the 8-item Likert scale questions. Composite scores were calculated for each item to obtain the total myopia knowledge score, which ranged from 1 to 40. To categorise scores for analytical and interpretive purposes, the midpoint score was used as a cutoff point. Hence, participants achieving a score of ≥20 were classified as having adequate knowledge, while those scoring <20 were considered to have inadequate knowledge. A p-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant at 95% confidence level for all inferential statistical analyses.

Ethical consideration

The study adhered to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was granted by the Committee of Human Research and Publication Ethics (CHRPE) (CHRPE/AP/801/22) at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) and the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (HSSREC) (HSSREC/00004822/2022) at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN). Formal written approval was obtained from appropriate education and school authorities as well as informed consent from parents. Additionally, assent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study. In order to ensure confidentiality and anonymity of participants, no personal information that could be traced to them was collected.

Results

A total of 1,420 school children participated in the study, with the majority being females, 774 (54.5%). The mean (SD) age was 13.44 (±1.47) years, and approximately 76% fell within the 10–14-year age group. The Mann-Whitney U test revealed a significantly higher mean age among pupils from the Bekwai Municipality, 14.06 (±1.62) years, compared to those from the Kumasi Metropolis, 13.25 ± 1.37 years (p<0.001, Table 1).

Of 1,258 participants, the majority, 935 (74.3%), reported never having undergone an eye examination. Furthermore, 558 (39.8%) participants indicated experiencing difficulty seeing at far, while 844 (69.2%) did not have such a symptom. Two hundred and sixty-five (47.5%) of those having difficulty seeing at far, and 306 (36.3%) of those without distance vision issues reported that they had relatives who experienced similar distance vision difficulties. Additionally, 134 (24.0%) of those reporting difficulty seeing at far and 248 (29.4%) of those without distance vision problems had no relatives with such challenges. About 159 (28.5%) of participants with difficulty seeing at far and 290 (34.4%) of those without difficulty seeing at far reported no knowledge of whether their relatives had distance vision difficulties. The relationship between having a relative with distant vision difficulties and having myopia was statistically significant (χ² = 17.57; p < 0.001). Among those reporting difficulty with distance vision, 56 (10.0%) used spectacles, whereas the remaining 502 (90.0%) did not utilise any optical aids.

Myopia awareness

Of 1,398 participants, 342 (24.5%) reported having heard of myopia, while 1,056 (75.5%) indicated that they had not. A binary logistic regression using participants’ demographic factors as independent variables and myopia awareness as dependent variable was performed. The model was statistically significant (χ2(8, 1,382) = 124.12, p<0.001), with 8.1% of the variance in the dependent variable explained by the predictors. Additionally, model diagnostics indicated good fit with a non-significant Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p=0.865) and no problematic multicollinearity (mean VIF=1.3). Participants’ age, (Adjusted Odds Ratio (aOR) = 1.17; 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.06-1.31; p = 0.003), district (aOR=0.26; 95% CI:0.19-0.37; p<0.001), school type (aOR=3.11; 95% CI: 2.31-4.18; p<0.001) and difficulty seeing at far (aOR=1.47; 95%CI: 1.13-1.91; p = 0.004) were statistically significant predictors of myopia awareness (Table 2).

Participants’ sources of myopia information and preferred mode of myopia awareness programme

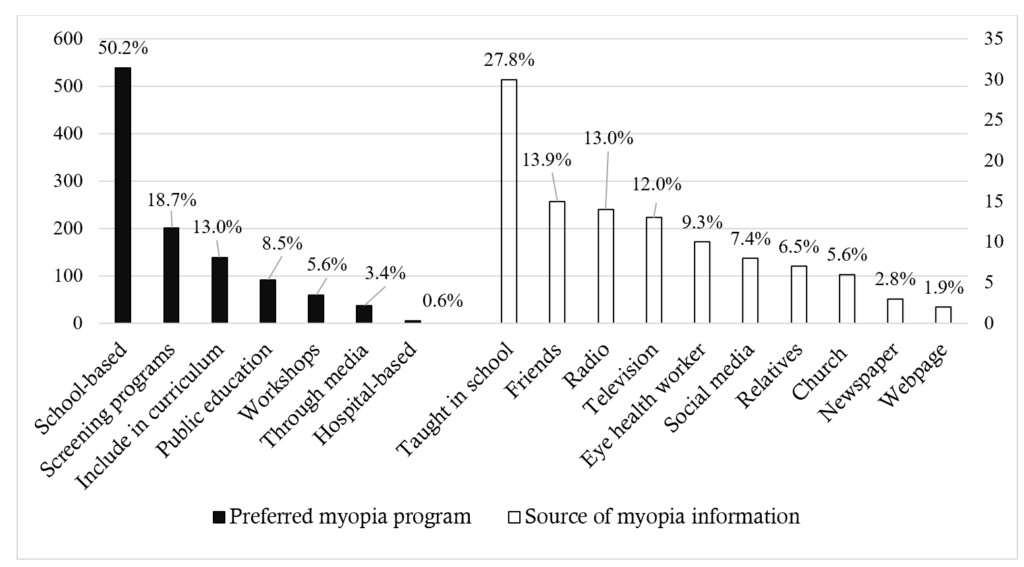

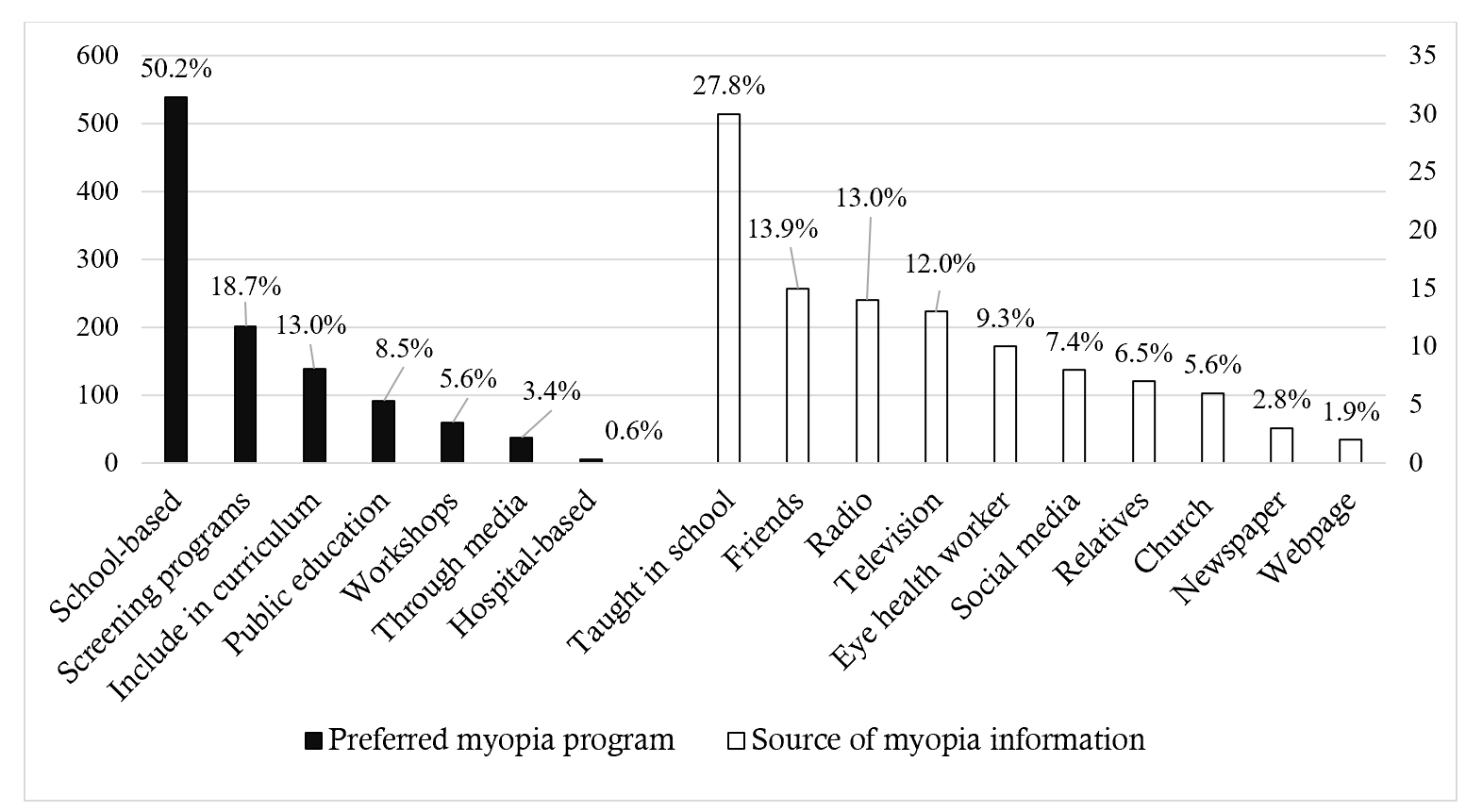

Regarding sources of myopia information, 108 multiple responses were provided by 64 (4.5%) participants. Of these, 30 (27.8%) indicated that they had been taught about myopia in school, while 2 (1.9%) reported obtaining information from websites (Figure 1). Of the 1,340 participants, 1,243 (92.8%) indicated support for a myopia awareness programme, while 97 (7.2%) opposed its implementation. Approximately half of the participants, 539 (50.2%), recommended that the awareness programme should be school-based, whereas 6 (0.6%) advocated for a hospital-based approach (Figure 1).

Myopia knowledge

Among the 342 participants reporting awareness of myopia, 324 (94.7%) answered questions on myopia knowledge. The mean knowledge score was 27.61 (5.69), ranging from 4 to 40. Inadequate knowledge was exhibited by 23 (7.1%) participants while 301 (92.9%) showed adequate knowledge. Kolmogorov-Smirnov (D (324) =0.08, p<0.001) and Shapiro-Wilk (W (324) =0.97; p<0.001) tests indicated non-normally distributed scores, with skewness (standard error) of -0.687 (0.135), and kurtosis (standard error) 1.329 (0.270). The Mann-Whitney U test showed that myopia knowledge was significantly associated with participants’ district (z=3.70, p<0.001), school grade (z=2.54, p=0.011), and school type (z=1.99, p=0.046), but had small effect sizes (Table 3).

An independent-samples Kruskal-Walli’s test revealed a statistically significant difference in myopia knowledge scores and age group (χ2(2, 324) =10.00; p=0.007) (Table 3). Dunn’s post hoc test showed that participants in the 10-14-year age group had significantly higher scores than those in 15-19 years (χ2(2, 324) =31.17; p=0.022) (Table 3). A binary logistic regression model to determine the impact of demographic factors on myopia knowledge showed an acceptable Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test (p =0.504) and no problematic multicollinearity (mean VIF=1.20). However, the model was not statistically significant (χ2(8, 321) = 7.66, p = 0.468, Table 4).

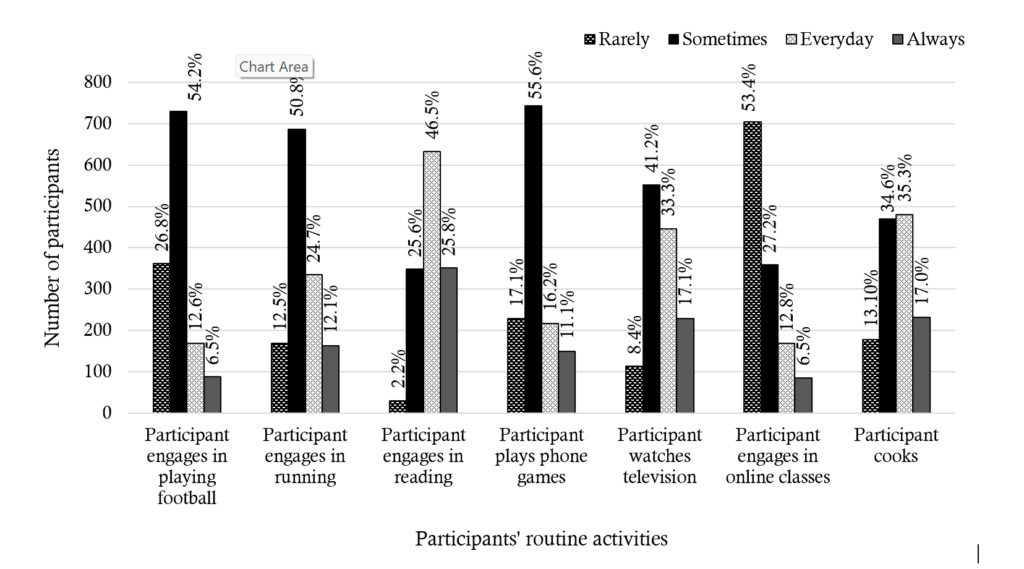

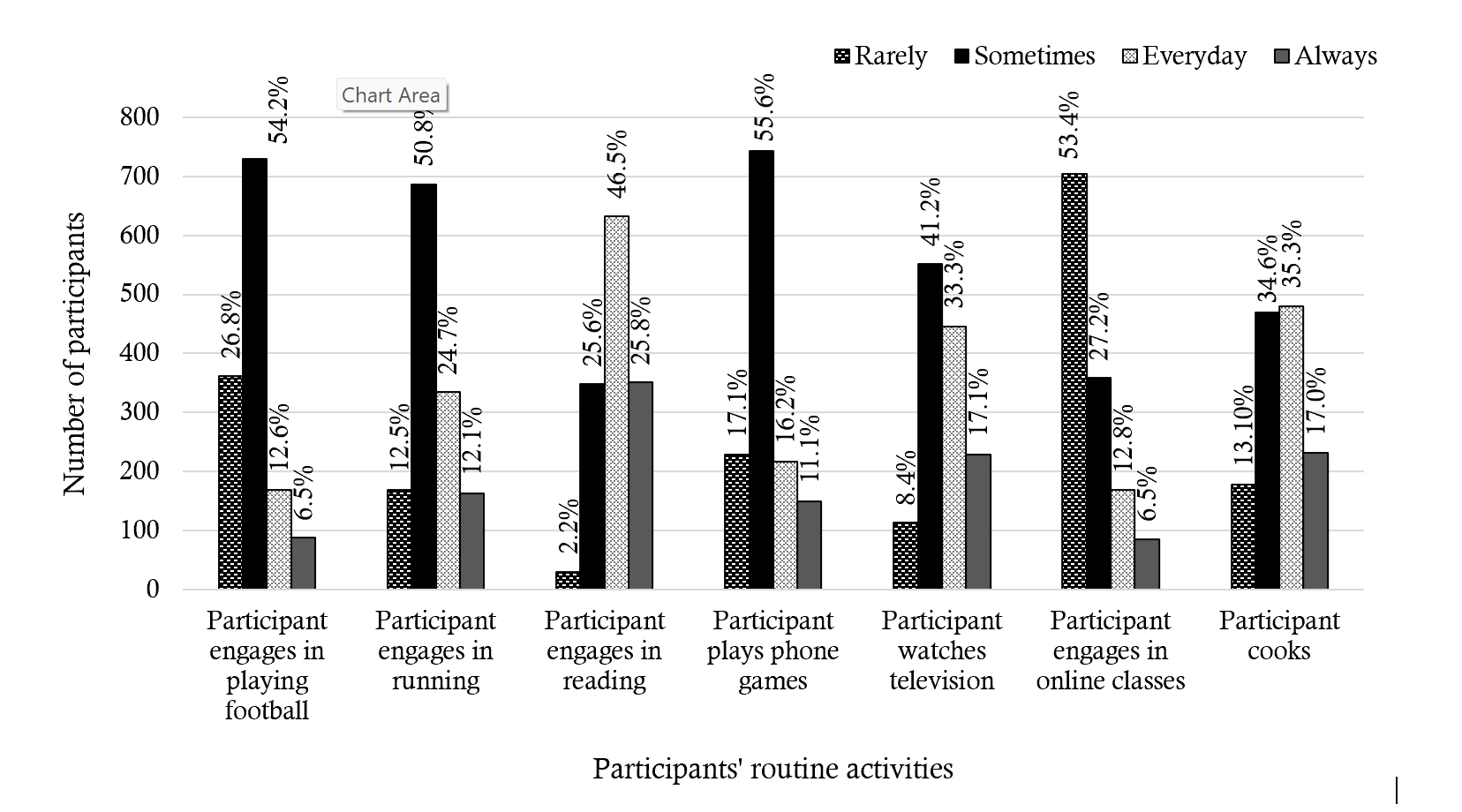

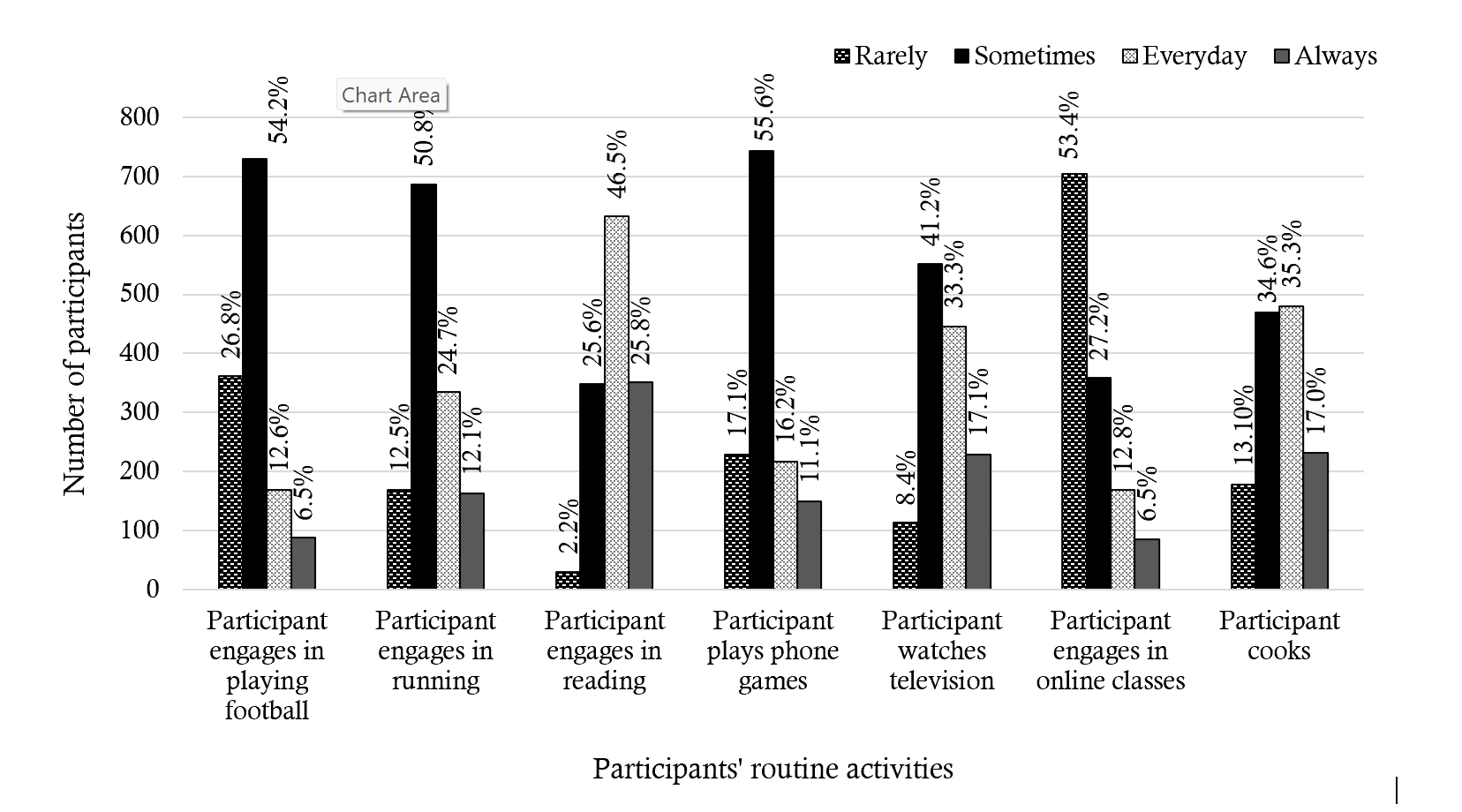

Participation in daily activities

The most frequently reported activity was reading, with 633 participants (46.5%) indicating daily engagement. In contrast, 729 (54.2%) and 687 participants (50.8%) respectively engaged in football and running on a less frequent basis. Similarly, playing phone games and watching television were performed occasionally by 743 (55.6%) and 552 (41.2%) participants, respectively. The least frequently engaged activity was participation in online classes, which was occurred rarely among 704 (53.5%) participants. Further details on the frequency of engagement in these activities (Figure 2).

Discussion

Myopia continues to be a significant public health issue, particularly affecting children and adolescents [31]. Consequently, understanding their perceptions in the development of myopia interventions is essential. This study provides evidence on the level of myopia awareness among basic school children and their preferred methods of receiving myopia information. The reported level of myopia awareness among the participants was notably low, being 24%. However, among those who were aware, the knowledge base was adequate. These findings highlight the urgent need for increased myopia awareness initiatives targeted at children. Although existing awareness programmes in Ghana, such as the Refractive Error Day [32] hold promise for improving refractive error awareness, it is not fully targeted at children and not exclusive to myopia, which further affirms the need for immediate attention. The unfamiliarity of participants with the term “myopia” likely contributed to the low awareness levels and suggests myopia-related educational content within the basic school curriculum may be limited or insufficiently emphasised. Integrating structured myopia health education into the curriculum could improve understanding and awareness. Consistent with observations from China, stakeholder collaboration to develop innovative and engaging educational resources may enhance myopia science literacy [33]. Revisiting existing policies and collaborations between the ministries of education and health may therefore facilitate the inclusion of targeted activities aimed at improving awareness. In contrast to these findings, a similar study in Saudi Arabia reported a substantially higher awareness rate (82%) among school children [34].

Myopia awareness and knowledge were significantly associated with age, school grade, participant’s district of residence, type of school, and difficulty seeing at far. For every one-year increase in age, participants were 17% more likely to be aware of myopia, indicating that older students were more likely to know about myopia than younger ones. Similarly, participants in higher school grade (JHS) demonstrated slightly higher knowledge compared to those in lower grade (Primary). This finding may be attributed to several factors including widened peer interaction, increased cognitive maturity and curious search of information due to interest in diverse topics and lived experience among older students. Moreover, myopia is typically diagnosed between 8 and 12 years of age, after which it progressively advances and eventually stabilises in adulthood with cessation of axial elongation [35]. This progression may be linked to the increasing recognition of symptoms, leading to a heightened search for related information and subsequently greater awareness among older children. Therefore, ensuring early integration of myopia information and vision health education into basic school curriculum at an early age could increase awareness and engender positive lifestyle modification against myopia development. While a Ghanaian adult study found an inverse relationship between myopia knowledge and age [36], the present findings align with reports among left-behind children of Chinese migrant workers [37].

District of residence was also a significant predictor of awareness. Participants from Kumasi metropolis were 74% less likely to be aware of myopia compared to their counterparts from the Bekwai Municipality, despite urban areas typically having greater access to health information. This unexpected pattern may reflect contextual differences, such as exposures to school-based vision screening initiatives or eye health outreach or non-governmental organisations in Bekwai [38]. The relatively older average age pattern of participants in Bekwai Municipality could also account for this trend. These findings indicate the need to scale school- and community-based health promotion across both urban and semi-urban areas. School Health Education Programme (SHEP) structures, for example, may serve as practical channels for disseminating myopia-related information. Similar disparities were previously documented among Ghanaian adults, where individuals from less developed northern regions exhibited higher myopia knowledge, attributed to non-governmental organisation-driven interventions [36].

School type was another key determinant of awareness. Learners in mission schools were over three times more likely to be aware of myopia than those from government schools, indicating that the type of school could influence myopia awareness of school children. Stricter supervision and monitoring in mission schools might potentially culminate in efficient integration of health education, and subsequent higher health awareness [39] . Additionally, mission schools are more likely to benefit from their related faith-based and church-affiliated health facilities through free school screening programmes and health talks, which students from public schools may not readily access, due to resource constraints. Furthermore, other factors such as variations in school curricula and an effective parental involvement, may contribute to the observed disparity in awareness levels in the different school types. Hence, mission schools and their affiliated health facilities could be engaged as strategic partners in eye and vision health promotion. Relevant authorities could further leverage existing network and collaboration for the development of health promotion strategies towards advancement of myopia awareness.

Participants who reported difficulty seeing at far had a 47% higher likelihood of being aware of myopia compared to those who had no challenge with their distance vision, suggesting that higher awareness is linked to lived experience and personal relevance, as these could arouse curiosity for information and possible modification in eye health seeking behaviour. In line with this, persons who have myopia could be effectively engaged as educators to raise awareness of the condition among their peers. However, it is worthy to note that over 74% of participants in the current study reported never having had an eye examination, suggesting a considerable burden of undiagnosed myopia and potential risk exposure. Furthermore, the finding reaffirms the critical need of access to and utilisation of eye care services, as a key to promoting eye health and mitigation against myopia. This finding is consistent with the work of Nyamai et al who found that only 39% of students attending public high schools in Nairobi County had ever had an eye-checkup [40]. Therefore, it is crucial that existing national policies focusing on health education among basic school children and future programmes contextually reflect the aforementioned variables to ensure success.

Most participants expressed support for the development of a school-based myopia awareness programme. This preference, influenced by the low baseline awareness, suggests stronger learner interest in acquiring relevant knowledge. The preference for a school-based programme may offer the advantage of being more relatable to students, potentially fostering greater engagement, acceptance, and facilitating early detection and referral of affected individuals [41-43]. Additionally, previous studies have supported the effectiveness of school-based myopia education programmes, demonstrating improvements in knowledge, attitudes and skills related to myopia [44]. Considering that preventive care is generally less resource-intensive than curative measures [45], promoting myopia awareness through cost-effective, school-based programmes presents a feasible strategy, particularly within low-income economies.

Approximately 5% of participants reported obtaining myopia-related information through educational instruction. This finding underscores the importance of integrating myopia awareness programmes into school curricula, as such initiatives provide a platform for acquiring new knowledge and insights. Notably, webpages emerged as the least utilised source of myopia information, which may partly be attributed to students’ preference for printed materials over online resources [46] coupled with a lack of interest in myopia-related topics, possibly due to lack of awareness. Additional factors, such as the financial costs associated with internet usage [47] and potential parental control [48], may further limit use of webpages for disseminating myopia information. These results contrast with those of a Saudi Arabian study [34], where parents and teachers were identified as the primary sources of myopia information for the school children. In contrast, a study conducted in China found television and the internet to be predominant sources of myopia knowledge [44].

Participants reported reading daily, whereas engagement in outdoor activities such as playing football and running were limited. While additional data is required for a comprehensive understanding of participants’ routine behaviours, these findings suggest a potential increase in exposure to myopia risk factors. However, the limited involvement in playing phone games, online teaching, and watching television may reduce their indoor time, potentially offering some protective effect. Nevertheless, further studies are warranted to explore these dynamics for accurate understanding of the risk exposure among these school children.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The study’s primary strengths lie in its large sample size and the application of rigorous statistical analyses. Additionally, the careful selection of participants and the use of validated data collection instruments contributed to the reliability of the findings. However, the cross-sectional design of the study precludes the establishment of causal relationships, may introduce recall bias, and the findings may not fully represent the true state of affairs.

Conclusion

The findings of the present study indicate that myopia awareness remains low among basic school children, with the majority supporting the implementation of a school-based awareness creation programme. Additionally, myopia awareness and knowledge were positively associated with age, district, school grade, school type, and history of previous eye examination. Finally, participants reported engaging in daily reading activities but had limited participation in activities such as playing football, running, mobile gaming, online teaching, and television viewing. These findings underscore the critical need for targeted myopia awareness initiatives among basic school children and provide valuable insights for the development of evidence-based intervention strategies.

What is already known about the topic

- Myopia represents a significant public health challenge worldwide, necessitating effective interventions.

- Environmental and lifestyle factors have significant impact on the development and progression of myopia among children.

- Protective lifestyle modifications could potentially mitigate the development and progression of myopia among children.

- Positive lifestyle modifications are fundamentally dependent on awareness and knowledge dissemination.

What this study adds

- The study provides evidence for myopia awareness among school children in the African context.

- It further highlights key demographic characteristics influencing myopia awareness levels among these children.

- The findings further underscore the critical need for targeted myopia awareness initiatives among basic school children.

- It offers valuable insights for the development of evidence-based public health intervention strategies.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all participants for their corporation. We appreciate the efforts of the College of Health Sciences (CHS), the Department of Optometry (UKZN), African Vision Research Institute (AVRI), and the Centre for Eye and Public Health Intervention Initiative (CEPHII), for their immense assistance. The authors are also grateful to the Doctor of Optometry students from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) who assisted in the data collection.

Authors´ contributions

S.K., K.P.M and K.S.N. were involved in conceptualising, designing and preparing the draft manuscript. S.K. collected and analysed the data. S.K, K.P.M and K.S.N. made equal contributions in writing, critically revising and finally approving this version of the article to be published.

| Demographic factor | Number of school children (n=1420) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| District | ||

| Kumasi Metropolis | 1,092 | 76.9 |

| Bekwai Municipality | 328 | 23.1 |

| Age group (years) | ||

| ≤9 | 12 | 0.9 |

| 10–14 | 1,075 | 75.7 |

| 15–19 | 333 | 23.5 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 646 | 45.5 |

| Female | 774 | 54.5 |

| School grade | ||

| Upper primary (4–6) | 209 | 14.7 |

| Junior High School | 1,211 | 85.3 |

| School type | ||

| Government | 956 | 67.3 |

| Mission | 464 | 32.7 |

| Difficulty seeing at far (n=1,408) | ||

| Yes | 558 | 39.6 |

| No | 850 | 60.4 |

| Relative has difficulty seeing at far (n=1,411) | ||

| Yes | 577 | 40.9 |

| No | 382 | 27.1 |

| Don’t know | 452 | 32.0 |

| Characteristics | Myopia Awareness | Crude OR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||

| Age | 342 | 1056 | 1.21 (1.12, 1.33) | <0.001 | 1.17 (1.10, 1.31) | 0.003* |

| District | ||||||

| Kumasi | 218 | 866 | 0.40 (0.30, 0.52) | <0.001 | 0.26 (0.19, 0.37) | <0.001* |

| Bekwai | 124 | 190 | Reference | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 148 | 489 | 0.90 (0.70, 1.15) | 0.376 | 0.89 (0.69, 1.16) | 0.393 |

| Female | 194 | 567 | Reference | |||

| School grade | ||||||

| Junior High School | 297 | 892 | 1.19 (0.84, 1.70) | 0.332 | 0.76 (0.48, 1.19) | 0.235 |

| Upper Primary | 45 | 164 | Reference | |||

| School type | ||||||

| Mission | 148 | 307 | 1.89 (1.47, 2.44) | <0.001 | 3.11 (2.31, 4.18) | <0.001* |

| Government | 194 | 749 | Reference | |||

| Difficulty seeing at far | ||||||

| Yes | 157 | 394 | 1.42 (1.11, 1.82) | 0.005 | 1.47 (1.13, 1.91) | 0.004* |

| No | 184 | 653 | Reference | |||

| Relative has difficulty seeing at far | ||||||

| Yes | 146 | 420 | 1.00 (0.75, 1.35) | 0.976 | 1.14 (0.83, 1.57) | 0.409 |

| Don’t know | 96 | 354 | 0.78 (0.57, 1.08) | 0.134 | 0.93 (0.66, 1.31) | 0.675 |

| No | 97 | 277 | Reference | |||

| Constant | 0.07 (0.02, 0.28) | <0.001 | ||||

| Factor | Sample (N) | Median (IQR) | Mean rank | Mann Whitney | Kruskal Wallis (χ²) statistic | p-value | Effect size (r) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| u-statistics | z-statistic | |||||||

| District | 324 | |||||||

| Bekwai Municipal | 117 | 26 (24, 29) | 136.94 | 15099.50 | 3.70 | <0.001* | 0.21 | |

| Kumasi Metropolis | 207 | 29 (25, 32) | 176.94 | |||||

| Gender | 324 | |||||||

| Male | 142 | 28 (24, 32) | 159.40 | 12529.50 | -0.47 | 0.638 | ||

| Female | 182 | 28 (25, 32) | 164.66 | |||||

| School grade | 324 | |||||||

| Upper primary | 39 | 26 (23, 28) | 126.79 | 6950.00 | 2.54 | 0.011* | 0.17 | |

| Junior High School | 285 | 28 (25, 32) | 167.39 | |||||

| School type | 324 | |||||||

| Government | 180 | 27 (24, 31) | 153.25 | 14625.50 | 1.99 | 0.046* | 0.11 | |

| Mission | 144 | 29 (25, 32) | 174.07 | |||||

| Difficulty seeing at far | 323 | |||||||

| Yes | 148 | 28 (25, 31) | 159.31 | 12552.00 | -0.48 | 0.633 | ||

| No | 175 | 28 (25, 32) | 164.27 | |||||

| Age group | 324 | 10.00 | 0.007* | |||||

| ≤9 | 6 | 25 (25, 26) | 98.83 | |||||

| 10–14 | 228 | 28 (25, 32) | 172.52 | |||||

| 15–19 | 90 | 27 (24, 30) | 141.36 | |||||

| Dunn’s post-hoc test with significance values adjusted by the Bonferroni correction for multiple tests | ||||||||

| Sample 1-Sample 2β | Test Statistic | Std. Error | Std. Test Statistic | Sig. | Adj. Sig.# | |||

| ≤9 vs 15–19 | -42.522 | 39.424 | -1.079 | 0.281 | 0.842 | |||

| ≤9 vs 10–14 | -73.689 | 38.672 | -1.905 | 0.057 | 0.170 | |||

| 15–19 vs 10–14 | 31.166 | 11.640 | 2.678 | 0.007* | 0.022* | |||

| Characteristics | Myopia Knowledge | Crude OR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inadequate | Adequate | |||||

| Age | 23 | 301 | 0.70 (0.50, 1.00) | 0.043 | 0.71 (0.48, 1.05) | 0.085 |

| District | ||||||

| Kumasi | 14 | 193 | 1.15 (0.48, 2.74) | 0.755 | 0.68 (0.24, 1.95) | 0.476 |

| Bekwai | 9 | 108 | Reference | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 11 | 131 | 0.84 (0.36, 1.97) | 0.689 | 0.87 (0.36, 2.11) | 0.756 |

| Female | 12 | 170 | Reference | |||

| School grade | ||||||

| Junior High School | 22 | 263 | 0.32 (0.04, 2.40) | 0.265 | 0.74 (0.08, 7.21) | 0.798 |

| Upper Primary | 1 | 38 | Reference | |||

| School type | ||||||

| Mission | 7 | 137 | 1.91 (0.76, 4.78) | 0.167 | 2.23 (0.78, 6.36) | 0.134 |

| Government | 16 | 164 | Reference | |||

| Difficulty seeing at far | ||||||

| Yes | 9 | 139 | 1.34 (0.56, 3.20) | 0.505 | 1.38 (0.56, 3.42) | 0.487 |

| No | 14 | 161 | Reference | |||

| Relative has difficulty seeing at far | ||||||

| Yes | 9 | 127 | 1.16 (0.42, 3.24) | 0.774 | 1.07 (0.37, 3.11) | 0.906 |

| Don’t know | 7 | 86 | 1.01 (0.34, 3.01) | 0.983 | 1.12 (0.36, 3.47) | 0.842 |

| No | 7 | 85 | Reference | |||

| Constant | 1727.579 | 0.007 | ||||

References

- Padmaja Sankaridurg, Nina Tahhan, Himal Kandel, Thomas Naduvilath, Haidong Zou, Kevin D. Frick, Srinivas Marmamula, David S. Friedman, Ecosse Lamoureux, Jill Keeffe, Jeffrey J. Walline, Timothy R. Fricke, Kovai V, Serge Resnikoff. IMI impact of myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci [Internet]. 2021 Apr 28 [cited 2026 Jan 13];62(5):2. Available from: https://iovs.arvojournals.org/article.aspx?articleid=2772540. doi:10.1167/iovs.62.5.2

- Brien A. Holden, Timothy R. Fricke, David A. Wilson, Monica Jong, Kovin S. Naidoo, Padmaja Sankaridurg, Tien Y. Wong, Thomas J. Naduvilath, Serge Resnikoff. Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology [Internet]. 2016 May [cited 2026 Jan 13];123(5):1036–42. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0161642016000257. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.006

- Ian G. Morgan, Amanda N. French, Regan S. Ashby, Xinxing Guo, Xiaohu Ding, Mingguang He, Kathryn A. Rose. The epidemics of myopia: Aetiology and prevention. Prog Retin Eye Res [Internet]. 2018 Jan [cited 2026 Jan 13];62:134–49. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1350946217300393. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.09.004

- Lin LLK, Shih YF, Hsiao CK, Chen CJ. Prevalence of myopia in Taiwanese schoolchildren: 1983 to 2000. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2004 Jan;33(1):27–33

- Jung SK, Lee JH, Kakizaki H, Jee D. Prevalence of myopia and its association with body stature and educational level in 19-year-old male conscripts in Seoul, South Korea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci [Internet]. 2012 Aug 15 [cited 2026 Jan 13];53(9):5579. Available from: http://iovs.arvojournals.org/article.aspx?doi=10.1167/iovs.12-10106. doi:10.1167/iovs.12-10106

- Pan W, Saw SM, Wong TY, Morgan I, Yang Z, Lan W. Prevalence and temporal trends in myopia and high myopia children in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis with projections from 2020 to 2050. Lancet Reg Health West Pac [Internet]. 2025 Feb [cited 2026 Jan 13];55:101484. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2666606525000215. doi:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2025.101484

- Zhang XJ, Zhang Y, Kam KW, Tang F, Li Y, Ng MPH, Young AL, Ip P, Tham CC, Chen LJ, Pang CP, Yam JC. Prevalence of myopia in children before, during, and after COVID-19 restrictions in Hong Kong. JAMA Netw Open [Internet]. 2023 Mar 22 [cited 2026 Jan 13];6(3):e234080. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2802737. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.4080

- Moreira-Rosário A, Lanca C, Grzybowski A. Prevalence of myopia in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis of data from 14 countries. Lancet Reg Health Eur [Internet]. 2025 Jul [cited 2026 Jan 13];54:101319. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2666776225001115. doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2025.101319

- Bullimore MA, Cheng X, Brennan NA. Increased prevalence of myopia in the United States between 1971 and 1972 and 1999 and 2004—a reappraisal. Ophthalmol Sci [Internet]. 2025 Sep [cited 2026 Jan 13];5(5):100786. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2666914525000843. doi:10.1016/j.xops.2025.100786

- Ovenseri-Ogbomo G, Osuagwu UL, Ekpenyong BN, Agho K, Ekure E, Ndep AO, Ocansey S, Mashige KP, Naidoo KS, Ogbuehi KC. Systematic review and meta-analysis of myopia prevalence in African school children. PLoS One [Internet]. 2022 Feb 3 [cited 2026 Jan 13];17(2):e0263335. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263335. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0263335

- Mashige KP, Jaggernath J, Ramson P, Martin C, Chinanayi FS, Naidoo KS. Prevalence of refractive errors in the Inanda area, Durban, South Africa. Optom Vis Sci [Internet]. 2016 Mar [cited 2026 Jan 13];93(3):243–50. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/00006324-201603000-00005. doi:10.1097/OPX.0000000000000771

- Kobia-Acquah E, Flitcroft DI, Akowuah PK, Lingham G, Loughman J. Regional variations and temporal trends of childhood myopia prevalence in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt [Internet]. 2022 Nov [cited 2026 Jan 13];42(6):1232–52. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/opo.13035. doi:10.1111/opo.13035

- Kwarteng MA, Mashige KP, Kyei S, Govender-Poonsamy P, Dogbe DSQ. Compliance with spectacle wear among learners with hearing impairment in Ghana. Afr J Disabil [Internet]. 2024 Jun 13 [cited 2026 Jan 13];13. Available from: http://www.ajod.org/index.php/AJOD/article/view/1314. doi:10.4102/ajod.v13i0.1314

- Kyei S, Gyaami RK, Abowine JB, Zaabaar E, Nti A, Asiedu K, Boadi-Kusi SB, Owusu-Afriyie B, Assiamah F, Armah A. Epidemiology and demographic risk factors for myopia in Ghana: a 5-year retrospective study. Discov Soc Sci Health [Internet]. 2024 May 13 [cited 2026 Jan 13];4(1):22. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s44155-024-00081-5. doi:10.1007/s44155-024-00081-5

- Kumah BD, Ebri A, Abdul-Kabir M, Ahmed AS, Koomson NY, Aikins S, Aikins A, Amedo A, Lartey S, Naidoo K. Refractive error and visual impairment in private school children in Ghana. Optom Vis Sci. 2013;90(12):1456-61. doi:10.1097/OPX.0000000000000099

- Ovenseri-Ogbomo GO, Assien R. Refractive error in school children in Agona Swedru, Ghana. Afr Vis Eye Health [Internet]. 2010 Dec 15 [cited 2026 Jan 13];69(2):86–92. Available from: http://avehjournal.org/index.php/aveh/article/view/129. doi:10.4102/aveh.v69i2.129

- Koomson NY, Lartey SY, Adjah KK. Prevalence of Myopia amongst patients with refractive error in the Kumasi Metropolis of Ghana. 2013 [cited 2026 Jan 13];33(2). Available from: https://journal.knust.edu.gh/index.php?journal=just&page=article&op=view&path[]=396

- Biswas S, El Kareh A, Qureshi M, Lee DMX, Sun CH, Lam JSH, Saw SM, Najjar RP. The influence of the environment and lifestyle on myopia. J Physiol Anthropol [Internet]. 2024 Jan 31 [cited 2026 Jan 13];43(1):7. Available from: https://jphysiolanthropol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40101-024-00354-7. doi:10.1186/s40101-024-00354-7

- Ba M, Li Z. The impact of lifestyle factors on myopia development: Insights and recommendations. AJO International [Internet]. 2024 Apr [cited 2026 Jan 13];1(1):100010. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2950253524000108. doi:10.1016/j.ajoint.2024.100010

- Cai T, Zhao L, Kong L, Du X. Complex interplay between covid-19 lockdown and myopic progression. Front Med [Internet]. 2022 Mar 21 [cited 2026 Jan 13];9:853293. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2022.853293/full. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.853293

- Zhang X, Cheung SSL, Chan HN, Zhang Y, Wang YM, Yip BH, Kam KW, Yu M, Cheng CY, Young AL, Kwan MYW, Ip P, Chong KKL, Tham CC, Chen LJ, Pang CP, Yam JCS. Myopia incidence and lifestyle changes among school children during the COVID-19 pandemic: a population-based prospective study. Br J Ophthalmol [Internet]. 2022 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 13];106(12):1772–8. Available from: https://bjo.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2021-319307. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2021-319307

- Yang X, Chen G, Qian Y, Wang Y, Zhai Y, Fan D, Xu Y. Prediction of myopia in adolescents through machine learning methods. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2020 Jan 10 [cited 2026 Jan 13];17(2):463. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/2/463. doi:10.3390/ijerph17020463

- Wang X, Cheng Z. Cross-sectional studies. Chest [Internet]. 2020 Jul [cited 2026 Jan 13];158(1):S65–71. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0012369220304621. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.012

- Nyatsikor MK. Primary school learners’ age and academic achievement in Ghana. The moderating effects of school types. Educ Res Theory Pract [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2026 Jan 13];35(1):53-71. Available from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1417705.pdf

- Ghana Education Service (GES). About Us [Internet]. Accra (Ghana): Ghana Education Services; 2025 [cited 2026 Jan 13]. Available from: https://ges.gov.gh/

- Ghana Education Service (GES). Early Childhood Education (ECE) Unit [Internet]. Accra (Ghana): Ghana Education Service (GES); 2025 [cited 2026 Jan 13]. Available from: https://ges.gov.gh/directorate.php?id=16

- US Embassy in Ghana. Education System of Ghana [Internet]. Accra (Ghana): US Embassy in Ghana; 2025 [cited 2026 Jan 13]. Available from: https://gh.usembassy.gov/education-culture/educationusa-center/educational-system-ghana/

- Taber KS. The use of cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res Sci Educ [Internet]. 2018 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 13];48(6):1273–96. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2. doi:10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2

- Spiliotopoulou G. Reliability reconsidered: Cronbach’s alpha and paediatric assessment in occupational therapy. Aust Occup Ther J [Internet]. 2009 Jun [cited 2026 Jan 13];56(3):150–5. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2009.00785.x. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1630.2009.00785.x

- Piedmont RL, Hyland ME. Inter-item correlation frequency distribution analysis: a method for evaluating scale dimensionality. Educ Psychol Meas [Internet]. 1993 Jun [cited 2026 Jan 13];53(2):369–78. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0013164493053002006. doi:10.1177/0013164493053002006

- Grzybowski A, Kanclerz P, Tsubota K, Lanca C, Saw SM. A review on the epidemiology of myopia in school children worldwide. BMC Ophthalmol [Internet]. 2020 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 13];20(1):27. Available from: https://bmcophthalmol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12886-019-1220-0. doi:10.1186/s12886-019-1220-0

- The Herald. Ghana Optometric Association launches maiden World Refractive Error Day [Internet]. Accra (Ghana): The Herald; 2024 Jul 17 [cited 2026 Jan 13]. Available from: https://theheraldghana.com/ghana-optometric-association-launches-maiden-worldrefractive-error-day/

- Liu Q, Chen M, Yan T, Jiang N, Shu Q, Liang X, Tao Z, Yang X, Nie W, Guo Y, Li X, Zhu DJ, Zeng C, Li J, Li L. A survey of public eye-care behavior and myopia education. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2025 Feb 18 [cited 2026 Jan 13];13:1518956. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1518956/full. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2025.1518956

- Almujalli AAA, Almatrafi AAA, Aldael AA, Almojali HA, Almujalli AI, Pathan A. Knowledge, attitude, and practice about myopia in school students in Marat city of Saudi Arabia. J Family Med Prim Care [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2026 Jan 13];9(7):3277. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/jfmpc/Fulltext/2020/09070/Knowledge,_attitude,_and_practice_about_myopia_in.20.aspx. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_86_20

- Osuagwu UL, Ocansey S, Ndep AO, Kyeremeh S, Ovenseri-Ogbomo G, Ekpenyong BN, Agho KE, Ekure E, Mashige KP, Ogbuehi KC, Rasengane T, Nkansah ND, Naidoo KS, Centre for Eyecare & Public Health Intervention Initiative (CEPHII). Demographic factors associated with myopia knowledge, attitude and preventive practices among adults in Ghana: a population-based cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2023 Sep 4 [cited 2026 Jan 13];23(1):1712. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-023-16587-7. doi:10.1186/s12889-023-16587-7

- Liu S, Yang G, Li Q, Pei R, Tang S. Knowledge, attitudes and practice toward refractive errors management among left-behind children of migrant workers. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2025 Jan 21 [cited 2026 Jan 13];12:1373209. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1373209/full. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2024.1373209

- Anokye GO, Price-Sanchez C, Yong AC, Ali M, Tate C, Graham R, Chan VF. School-based eye health interventions for improving eye care and spectacles compliance in children in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. AJO International [Internet]. 2025 Jul [cited 2026 Jan 13];2(2):100126. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2950253525000292. doi:10.1016/j.ajoint.2025.100126

- Emukowhate C. Impact of ethical leadership on job satisfaction in public secondary school in Kaduna State. IJAMPS [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2026 Jan 13];4(2):E-ISSN: 2814-038. Available from: https://ijamps.com/view-journal.php?id=66

- Adhiambo Nyamai L, Kanyata D, Njambi L, Njuguna M. Knowledge, attitude and practice on refractive error among students attending public high schools in Nairobi County. J Ophthalmol East Cent South Afr [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2026 Jan 13];35-41. Available from: https://joecsa.coecsa.org/index.php/joecsa/article/view/124

- Knifsend CA, Camacho-Thompson DE, Juvonen J, Graham S. Friends in activities, school-related affect, and academic outcomes in diverse middle schools. J Youth Adolesc [Internet]. 2018 Jun [cited 2026 Jan 13];47(6):1208–20. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10964-018-0817-6. doi:10.1007/s10964-018-0817-6

- Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2017 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 13];17(1):88. Available from: http://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-017-2031-8. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2031-8

- Jan CL, Timbo CS, Congdon N. Children’s myopia: prevention and the role of school programmes. Community Eye Health. 2017 [cited 2026 Jan 13];30(98):37–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29070927/

- Huang LM, Xie YH, Meng ZY, Chen T, Dai BF, Yu Y, Zeng Z, Zhou CY, Lin JJ, Chen YH, Wang Q, Hu JM. Improving myopia awareness via school-based myopia prevention health education among Chinese students. Int J Ophthalmol [Internet]. 2023 May 18 [cited 2026 Jan 13];16(5):794–9. Available from: http://ies.ijo.cn/gjyken/ch/reader/view_abstract.aspx?file_no=20230518&flag=1. doi:10.18240/ijo.2023.05.18

- Wang F. The roles of preventive and curative health care in economic development. PLoS One [Internet]. 2018 Nov 7 [cited 2026 Jan 13];13(11):e0206808. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0206808. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0206808

- Skutil M, Krupová J, Svárovská A. Sources of information in the life of pupils in the 1st grade of primary school. Procedia Soc Behav Sci [Internet]. 2012 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 13];69:2237–42. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1877042812056601. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.12.193

- Sonaike SAS. The internet and the dilemma of africa’s development. Gazette (Leiden, Netherlands) [Internet]. 2004 Feb [cited 2026 Jan 13];66(1):41–61. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0016549204039941. doi:10.1177/0016549204039941

- Phyfer J, Burton P, Leoschut L, Lezanne. Global Kids Online South Africa: barriers, opportunities and risks. A glimpse into South African children’s internet use and online activities [Internet]. Cape Town, South Africa: Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention; 2016 [cited 2026 Jan 13]. Available from: https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/71267/2/GKO_Country-Report_South-Africa_CJCP_upload.pdf