Research | Open Access | Volume 9 (1): Article 02 | Published: 02 Jan 2026

Eliminating leprosy from the Volta Region, Ghana: The importance of linking all cases to care

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Tables

| Variables | Frequency (N = 82) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 41 | 50.0 |

| Female | 41 | 50.0 |

| Age, median (IQR), years | 55 (37–65) | |

| Age (years) | ||

| <25 | 5 | 6.1 |

| 25–34 | 11 | 13.4 |

| 35–44 | 13 | 15.9 |

| 45–54 | 10 | 12.2 |

| ≥55 | 43 | 52.4 |

| Residence of the case seen | ||

| Within the Volta Region | 79 | 96.3 |

| Outside the Volta Region | 3 | 3.7 |

| Year | ||

| 2019 | 17 | 20.7 |

| 2020 | 23 | 28.1 |

| 2021 | 27 | 32.9 |

| 2022 | 11 | 13.4 |

| 2023 | 4 | 4.9 |

| Class of Leprosy | ||

| Multibacillary (Mb) | 80 | 97.6 |

| Paucibacillary (Pb) | 2 | 2.4 |

| Disability Grading | ||

| Grade 0 | 72 | 87.8 |

| Grade 1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Grade 2 | 10 | 12.2 |

| Treatment outcome | ||

| Complete treatment | 58 | 70.7 |

| Died | 3 | 3.7 |

| Transferred out | 2 | 2.4 |

| Lost to follow-up | 19 | 23.2 |

Table 1: Demographic and clinical characteristics of reported leprosy cases, Volta Region, 2019–2023

Figures

Keywords

- Leprosy

- Trend

- Distribution

- Volta Region

- Ghana

Chrysantus Kubio1,2, Christopher Kankpetinge3, Victor Zeng4, Christian Atsu Gohoho5, Williams Azumah Abanga6, Ignatius Aklikpe4, Christopher Sunkwa Tamal7, Gyesi Razak Issahaku8, Samuel Adolf Bosoka9, Maxwell Afetor4, Frank Baiden2

1Volta Regional Health Directorate, Ghana Health Service, Ho, Ghana, 2Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Fred N. Binka School of Public Health, University of Health and Allied Sciences, Ho, Ghana, 3Ketu North Municipal Health Directorate, Ghana Health Service, Volta Region, Dzodze, Ghana, 4Health Information Unit, Volta Regional Health Directorate, Ghana Health Service, Ho, Ghana, 5Disease Control Unit, Volta Regional Health Directorate, Ghana Health Service, Ho, Ghana, 6Saboba District Health Directorate, Ghana Health Service, Saboba, Ghana, 7WHO Country Office, Accra, Ghana, 8Laboratory Department, Tamale Teaching Hospital, Tamale, Ghana, 9Disease Surveillance Unit, Volta Regional Health Directorate, Ho, Ghana.

&Corresponding author: Chrysantus Kubio, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Fred N. Binka School of Public Health, University of Health and Allied Sciences, Ho, Ghana, Email: chryskubio@yahoo.com

Received: 25 Jul 2025, Accepted: 29 Dec 2025, Published: 02 Jan 2026

Domain: Infectious Disease Epidemiology

Keywords: Leprosy, trend, distribution, Volta Region, Ghana

©Chrysantus Kubio et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Chrysantus Kubio et al Eliminating leprosy from the Volta Region, Ghana: The importance of linking all cases to care. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;9(1):02. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00165

Abstract

Introduction: Leprosy is earmarked for elimination in Ghana. However, achieving zero leprosy case reporting has been a challenge since 1998. This study described the geographical distribution, trends and treatment outcomes of leprosy in the Volta Region of Ghana to help understand the progress being made to achieve zero leprosy in the region.

Methods: Leprosy surveillance data from 2019 to 2023 were analyzed for the 18 districts in the Volta Region. Data on leprosy cases were extracted from the leprosy registers and analyzed as frequencies, rates, and proportions. The leprosy incidence rate was computed per 1,000,000 population. Results were presented in tables, charts, and maps.

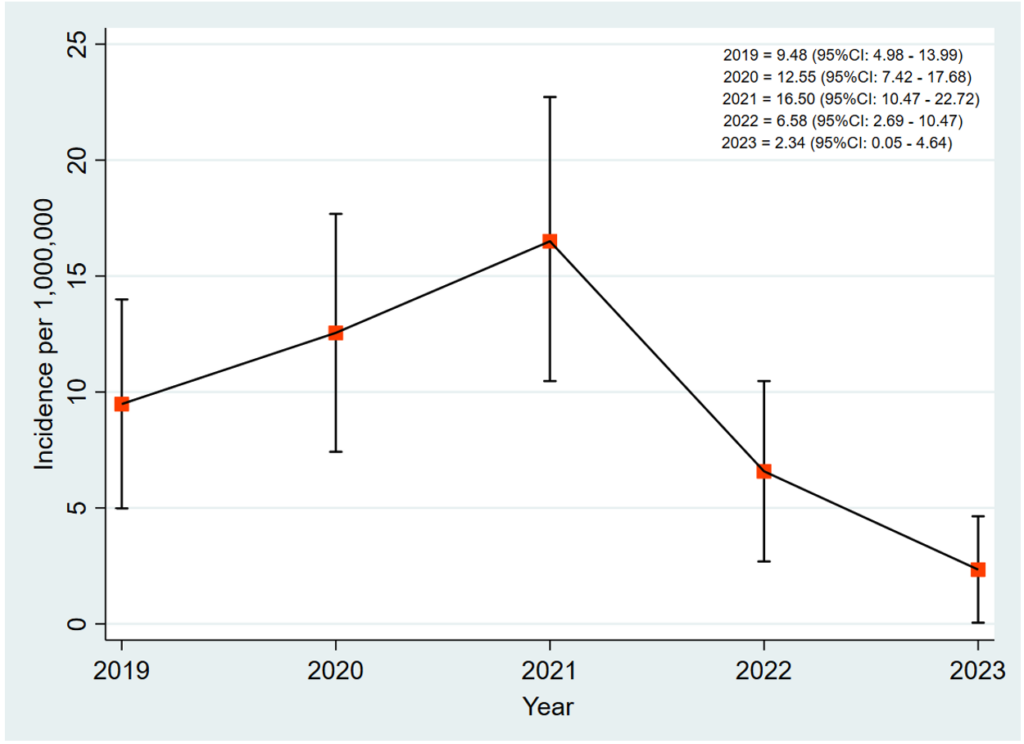

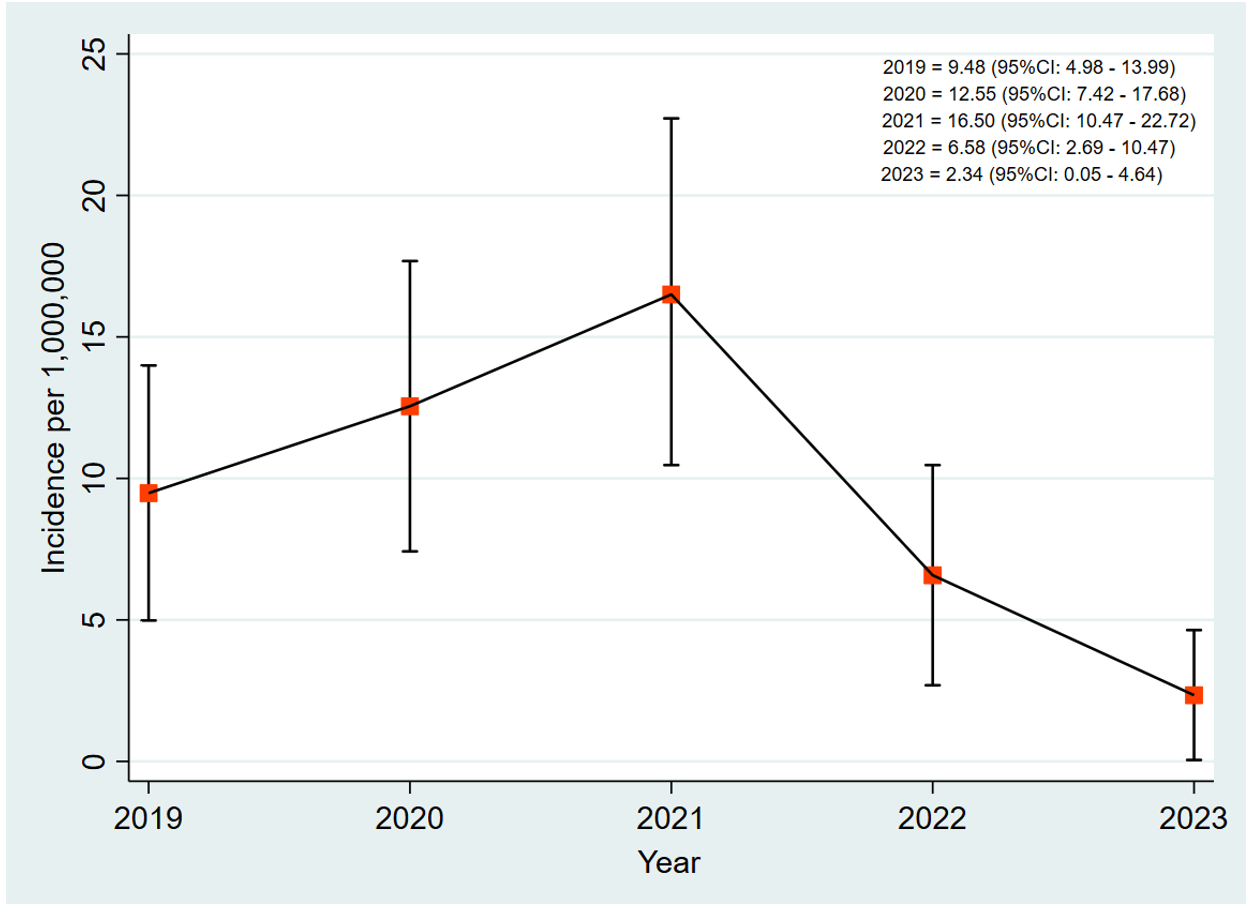

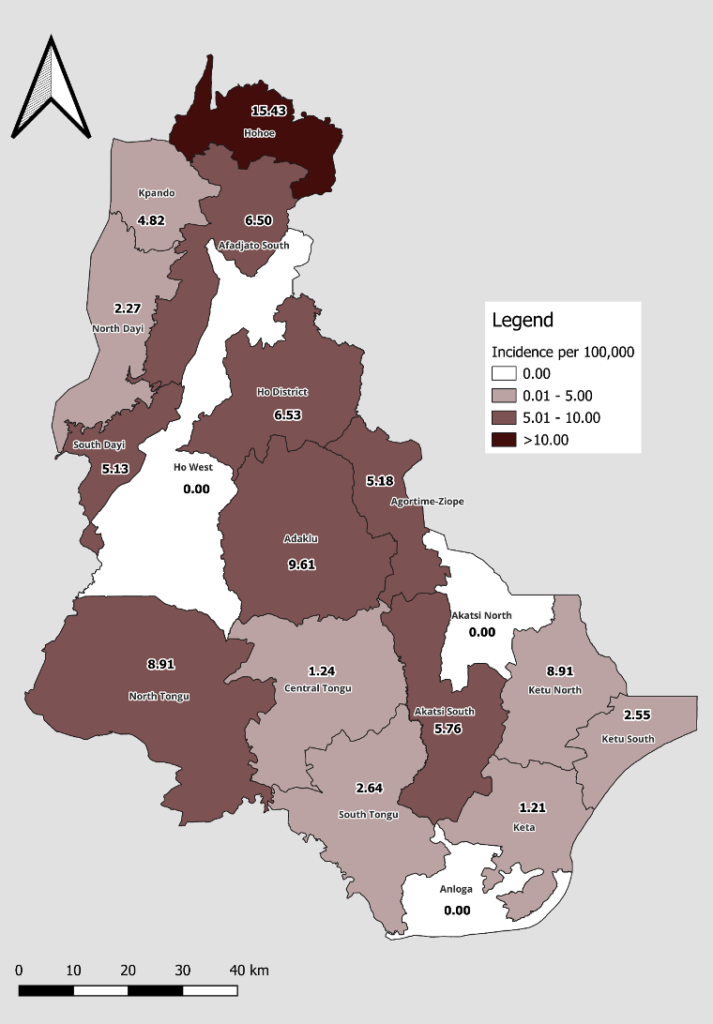

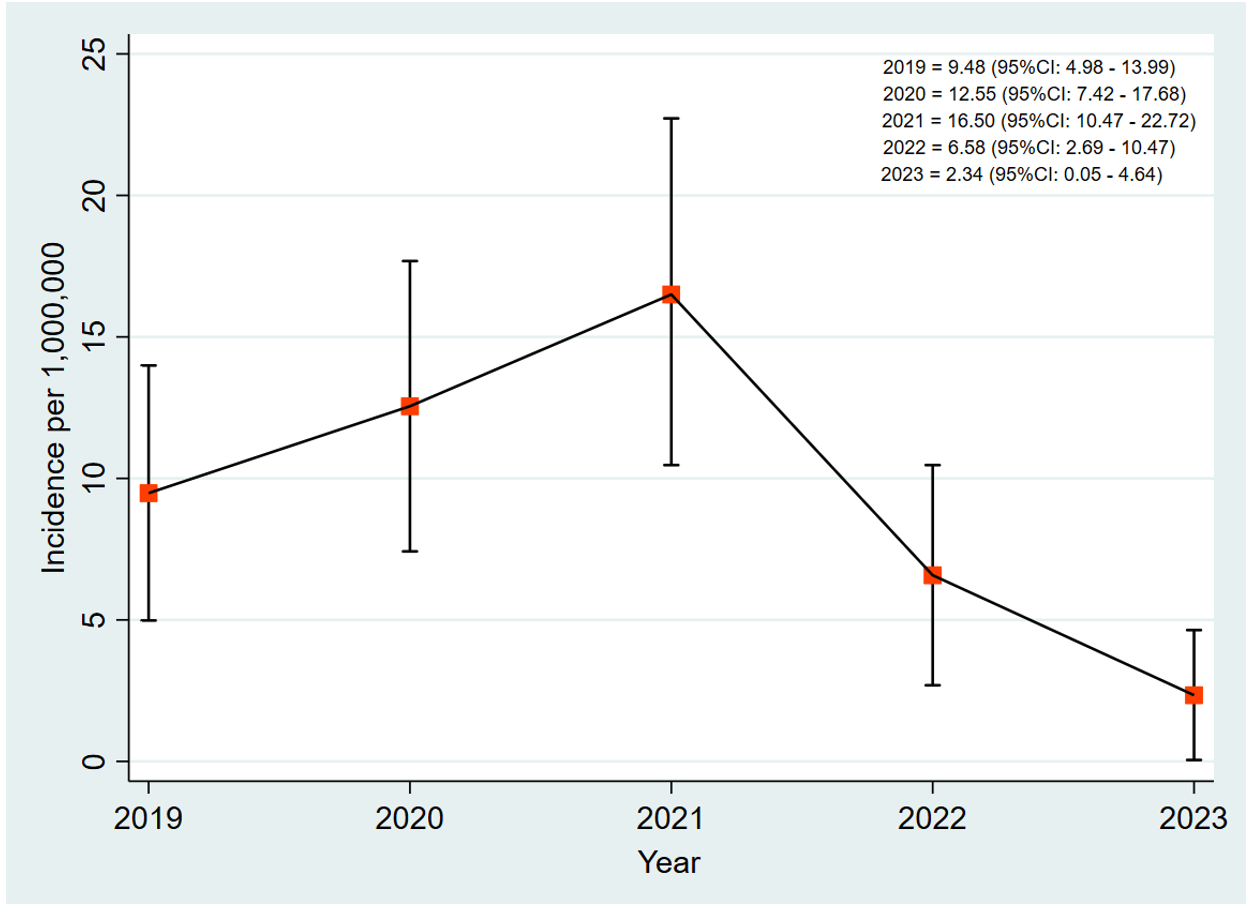

Results: Over the period, a total of 82 new leprosy cases were reported in the Volta Region. Three of the 82 cases were transferred into the region. The median age of the cases was 55 (IQR=37-65) years. The cases among males and females were equally distributed (41 cases each). Almost all the cases (80 of the 82) were multibacillary. Fifty-eight cases (70.7%) completed treatment. However, three cases were confirmed dead, while 19 (23.2%) were lost to follow-up. The incidence of leprosy increased from 9.48 per 1,000,000 in 2019 to 16.50 per 1,000,000 in 2021 and decreased to 2.34 per 1,000,000 in 2023. Geographically, the highest number of cases, 17, were reported in Hohoe Municipality.

Conclusion: Leprosy cases were predominant among older adults in the Volta Region. The incidence of leprosy is declining in the region; however, the number lost to follow-up is high. A linkage between treatment centres and community health nurses is needed to help reduce the number of cases lost to follow-up.

Introduction

Leprosy (Hansen’s disease) is an ancient chronic disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae [1,2]. It is an infectious, neglected tropical disease that principally affects the peripheral nerves and other parts of the body, including the skin, eyes, and the mucosa of the upper respiratory tract [3,4]. Untreated leprosy infection can cause impairment, permanent disability and debilitating deformities, resulting in social stigma that affects the health-seeking behaviour of victims [3,5]. Late detection of cases normally leads to major disabilities [6]. The World Health Organization (WHO) indicates that 9,729 new cases with Grade-2 Disabilities (G2D) were recorded globally in 2023 [3]. A study by Chen and colleagues, among migrant patients, observed an increase in the G2D rate from 18.0% in 2001 to 25.7% in 2021.

Leprosy is targeted for elimination [7] and there has been a substantial decline in cases worldwide from over 5 million in the 1980s to 133,802 in 2021 (4). Despite the remarkable progress towards the global elimination drive, earlier targets set were not met, as new cases continue to occur in many countries [4]. The WHO estimates that over 200,000 new cases occur annually in over 120 countries [2]. In 2023, over 182,815 new leprosy cases were reported from 184 countries, provinces and territories, of which 39.8% were females and 5.6% were children [3]. Leprosy cases have been geographically distributed with variations across South-East Asia, the Americas, Africa, Eastern Mediterranean, Western Pacific, Europe and other territories [3].

The WHO Africa region is one of the regions that has countries with high rates of leprosy cases, with 42 out of the 47 countries reporting new cases in 2022 [9]. Approximately 12.6% of the 174,087 cases reported in 2022 were from Africa; six countries reported over 1,000 new cases, 17 reported cases ranging from 101 to 1,000 and the rest reported 100 and below [9]. A study in Togo revealed that new leprosy cases increased from 70% in 2010 to 96.6% in 2022, with cases reported mostly in the health districts [10].

Ghana, according to the WHO, is one of the African countries that reported cases ranging from 101 to 1,000 in 2022 [9]. Available data show that 279 new cases were reported in 2019, while 153 new cases were detected in 2020 in Ghana [11]. In 2022 and 2023, the country recorded 277 and 234 new cases, 13.0% and 15.8% with G2D, respectively [12]. The elimination goal for leprosy in Ghana is a prevalence of <1 new case with G2D per 1,000,000 population [7]. Several interventions have been implemented in the country and the Volta Region to help achieve the leprosy elimination agenda. It is imperative to understand the progress made towards these elimination targets. Despite Ghana’s commitment to leprosy elimination, the reviewed literature has shown that no studies have explored the epidemiological profile of leprosy in the Volta Region. Examining the distribution, trends, and treatment outcomes of leprosy is crucial to understanding the progress towards achieving zero leprosy in the Volta Region of Ghana. This will help advocate for community involvement in early case detection and health education, as well as efficient resource allocation to high-incidence districts as part of the “Towards Zero Leprosy Strategy” by 2030 by the WHO [13]. This study described the incidence, trends, and geographical distribution of leprosy in the Volta Region of Ghana between 2019 and 2023.

Methods

Study design and setting

This study employed a descriptive cross-sectional analysis using secondary data collected from the leprosy surveillance system from January 2019 to December 2023. The analysis focused on individuals diagnosed with leprosy at health facilities in the Volta Region during the study period. The Volta Region is one of the 16 regions in Ghana with 18 administrative districts.

Data collection and processing

Secondary data were extracted from the leprosy registry, which included variables such as demographic data: age, sex, and residence of patients; clinical information: type of leprosy (paucibacillary or multibacillary) and disability grading (GD) as classified by the WHO (G0D, G1D, G2D). Diagnosis and treatment outcomes: date of diagnosis, date of treatment completion and outcome of treatment.

All reported cases with a confirmed diagnosis of leprosy according to WHO criteria and with complete data on key variables were included. To minimize errors, two independent data entry clerks were tasked to extract records from the leprosy registry. The data was then reviewed for completeness and consistency. Records with duplicate entries were excluded from the analysis. Data was anonymized to ensure confidentiality and safeguard patients’ private information. The study included only clinically confirmed cases of leprosy recorded in the surveillance registry.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata version 17 (15). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and clinical characteristics. Quantum Geographical Information System (QGIS) was used to geographically display the cases of leprosy across districts in the Volta Region. The incidence of leprosy per any geographic unit (district or region) was computed by dividing the number of leprosy cases by the total (district/regional) population per 1,000,000.

Ethics statement

This study adhered to the Helsinki Declaration on research. The need for informed consent and ethical approval for the study was waived according to the Public Health Act, 2012, of Ghana, which requires the Ghana Health Service to maintain and update surveillance data for diseases that are prone to epidemics and public health events. As a result, no formal ethical approval was needed for this study. Additionally, anonymized secondary data was used for the analysis. However, the Volta Regional Health Directorate granted administrative approval for the use of the data for the study (Reference number of the administrative approval letter: GHS/VRHD/ORD/46).

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of reported leprosy cases

A total of 82 cases of leprosy were retrieved from the leprosy register from 2019 to 2023. The majority of the cases were reported in 2021, 27 (32.9%), followed by 23 (28.1%) cases in 2020. Males, 41 (50.0%) and females, 41 (50.0%) were evenly distributed. The median age of cases was 55 (IQR=35-67) years, with more than half of the cases (52.4%) 55 years and above. The majority of cases, 79 (96.3%), had their residence in the Volta Region, whereas 3 (3.7%) resided in communities outside the Volta Region. The majority of cases, 80 (97.6%), were multibacillary (mb) while two cases (2.4%) were paucibacillary (pb). There was no grade 1 disability (G1D) among the cases recorded. However, 10 of the cases were grade 2 disability (G2D) and the remaining 72 were grade 0 disability (G0D). Out of the 82 patients who started treatment for leprosy, 58 (70.7%) completed treatment, 19 (23.2%) were lost to follow-up, 3 (3.7%) died and 2 (2.4%) were transferred to different regions to continue treatment (Table 1).

Incidence of leprosy cases

The incidence of leprosy in the Volta Region increased from 9.48 [95% CI: 4.98 – 13.99] per 1,000,000 in 2019 to 16.50 [95% CI: 10.47 – 22.72] per 1,000,000 in 2021. The incidence decreased from 16.50 [95% CI: 10.47 – 22.72] per 1,000,000 in 2021 to 6.58 [95% CI: 2.69 – 10.47] per 1,000,000 in 2022. It further decreased to 2.34 [95% CI: 0.05 – 4.64] per 1,000,000 in 2023 (Figure 1).

Geographical distribution of leprosy cases

The Hohoe Municipality recorded the highest number of leprosy cases with an incidence of 15.43 per 100,000. South Dayi, Agortime-Ziope, Akatsi South, Afadzato South, Ho, North Tongu, and Adaklu recorded an incidence ranging from 5.13 to 9.61 per 100,000. No case was recorded in Akatsi North, Ho West, or Anloga (Figure 2) over the study period.

Discussion

This study examined the geographical distribution, trends and treatment outcomes of leprosy cases in the Volta Region from 2019 to 2023. It aimed to understand the progress made towards achieving the WHO Zero-Leprosy Strategy in the region. The findings will inform policy decisions and response efforts to eliminate leprosy in the region and Ghana at large.

The study observed a fluctuation in the incidence of leprosy cases from 9.48 per 1,000,000 population in 2019 to a peak of 16.50 per 1,000,000 population in 2021 and then a decline in the last two years of the study period. This is consistent with findings from a study in Tanzania, which reported a reduction in leprosy cases from 3.1 per 100,000 population in 2017 to 2.4 per 100,000 in 2020 [14]. Similar to our findings, a downward incidence of leprosy cases from 0.29 per million population in 2020 to 0.27 per million population in 2021 was reported in China [15]. The findings from a studyin Togo, however, observed an increasing trend of leprosy cases from 70% in 2010 to 96.6% in 2022 [10]. The varied results from the different studies could be attributed to several factors, including the study settings, the objective of the study, the kind of data collected and the data collection method. Our study, for example, relied on health facility-based data of leprosy cases on treatment within the five-year period. Unlike other data collection methods, the tendency for our study to understate the actual burden of the disease may be high. Other possible factors that may account for differences in research findings include the endemicity of the disease in the different study locations, knowledge level on the disease, surveillance mechanisms for the disease, access to healthcare and stigmatization [16–19].

Possible reasons that might have accounted for the fluctuation of cases as observed in our study are a change in reporting practices/systems, the dynamics in transmission patterns of the disease, the level of awareness of the disease, case management and other public health actions [10,20–23]. Particularly, the rising incidence of cases from 2019 to the peaking of cases in 2021 could be ascribed to the launching of the national NTDs master plan in 2021[24] which could have resulted in heightened awareness creation about the disease, community-level engagement, mobilizations and related activities, thereby contributing to more cases being detected [25]. The decline in cases after the peak, on the other hand, could be due to robust case management practices and effective control interventions. It could also be because of poor knowledge of the disease and where to seek care, poor community engagement and linkage of leprosy cases to health facilities. Also, it is important to mention that interventions and strategies implemented by the 2021-2025 NTDs master plan could have contributed to the decline in cases between 2021 and 2023 [25]. Besides, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on case finding and other public health efforts during the period cannot be overruled. This is largely because the decline of cases began at the peak of COVID-19, when almost all efforts were shifted towards combating the pandemic at the expense of other diseases of public health concern [18,26,27]. It is, however, possible that the rise in cases at the onset of COVID-19 in 2020 to the peak of cases in 2021 could have been due to early reporting of cases to seek medical care, probably triggered by fear of the high complications and mortality associated with COVID-19 co-morbidity and chronic diseases.

The study reported a 70.7% treatment completion rate among the cases put on treatment. This is quite significant when compared to the 57.1% treatment completion rate observed by a similar study in the Philippines [28]. It is, however, lower than the national treatment completion target of ≥90% for Ghana [29] and a 74.7% treatment completion rate reported in Zanzibar [30]. The loss to follow-up of 23.2% of cases put on treatment is a bit alarming. It raises concerns about tracking mechanisms for cases put on treatment, healthcare accessibility and patient adherence to treatment. Also, the 3.7% mortality rate recorded by the study was comparatively lower than 6% observed by Figueres-Pesudo et al [31]. The fact that most (97.6%) cases were multibacillary, with 10 (12.2%) of them as disability grade 2, suggests there might have been some underlying factors that compounded their situation. Some attributable reasons could include secondary infection of wounds or injuries that were probably left untreated or were poorly treated, leading to possible complications such as sepsis, osteomyelitis, cellulitis and other vital organ damage [32]. Aggravations of patients’ condition by comorbidities or conditions such as diabetes mellitus, anaemia, hypertension and kidney problems, delayed diagnosis and treatment, especially of grade 2 disability patients, increase the disease’s progression and severe nerve damage, chronic ulcer, which can result in death [31]. Lastly, most of these patients might have lacked the needed care and support from families and relatives due to stigma. The consequences of this neglect are poor nutrition, poor adherence to treatment regimen, social exclusion and psychological trauma, which affect their overall well-being and increase their risk of death. Coupled with this is the fact that most of these patients may be very poor and are unable to afford the cost of visiting the health facilities for periodic assessment and additional medication to continue their treatment per protocol [32,33]. It is, therefore, crucial to implement measures for early diagnosis and treatment of cases, encouraging family and community support, discouraging and educating against stigmatization, educating patients on treatment adherence, and instituting effective follow-up mechanisms to improve treatment outcomes.

With respect to sex, the cases of leprosy from the study were evenly distributed between males and females. This implies that the disease does not favor one by virtue of their sex characteristics. This, however, contrasts with the findings of other studies in different geographical locations. In Ecuador, for instance, Hernandez-Bojorge et al found that most males (71.5%) were affected by leprosy compared to their female counterparts [34]. Similarly, a study in Tanzania was not different, as they reported 64.3% of male patients to be affected with the disease [14]. The story in West Java was the same, with the disease commonly found among males [35]. Disparities in sex distribution of cases can be attributed to socio-cultural factors such as stigmatization and gender norms regarding household decision-making, which automatically affect healthcare-seeking behaviour. While generally females are almost always ready to seek health care even with minor ailments [36], they might not have the courage and confidence to withstand stigma with a debilitating disease like leprosy and as a result, may decide not to seek care. Also, unlike females, males, especially in African settings, tend to have a higher decision-making autonomy, including health care decisions for the family. In most cases, without their permission, women are unable to seek health care [37–41]. These could lead to an underestimation of cases in the female population, as observed by the study. That aside, males are mostly seen as breadwinners of the household and may defy the odds of stigma to seek care for leprosy to prevent deformities that may render them incapable of performing their masculine duties. Moreover, beyond the household, males are more likely to be associated with a lot of social networks than females, which may expose them to a higher risk of contracting the disease. It is, however, important to add that there is no medical evidence to the knowledge of the authors to suggest that leprosy is more likely to occur in males than females. Nonetheless, interventions for the control of leprosy should be designed and tailored to the most vulnerable groups.

Furthermore, the study revealed that more than half (52.4%) of the cases were persons aged 55 years and above. This aligns with results from other studies, indicating that the older population might be the most at-risk group for the disease. For example, a study in Ecuador reported 63% of leprosy cases in persons over 50 years old as the most affected age group [34]. In a separate study in Tanzania[14], most cases (38.7%) were in the age group of 35 to 54 years. Attributable reasons for this may partly be delayed diagnosis, the long incubation period of the disease (an average of five to 20 years following exposure), which might result in late manifestation of the disease, usually at an advanced age [42,43]. It will also not be out of place to assert that the older age groups are most affected by the disease because geriatric-related factors such as weakness in the peripheral nervous system, chronic conditions and other physiological factors might have suppressed their immune system. This is confirmed by observations from similar studies that found that the aging process decreases immunosenescence as a result of dysfunction of innate immune cells, phagocytosis impairment and malfunctioning of T- and B-lymphocytes, giving rise to bacterial invasion [44–46]. Other contributory factors may include comorbidities [42], poor nutrition, perception about the disease and health-seeking behaviour (resorting to spiritual, traditional and alternative sources for care), living in rural and remote settings, stigma, lack of information and awareness of the disease and treatment availability [47]. Therefore, it may be prudent as part of public health actions to embark on active case finding through targeted awareness creation and screening among older and younger people for the timely diagnosis and treatment of cases. Collaboration with community stakeholders through effective community engagement will also help link cases for early diagnosis and treatment.

The concentration of cases in Hohoe and Ho municipalities observed by the study may be influenced by population density and sociocultural factors such as access to health care [10], educational status, knowledge level and health-seeking behaviour of the people. Local socio-economic conditions like poverty, unemployment, poor housing and overcrowded living conditions could all be underlying triggers for the high proportion of cases in the region and the two municipalities. The zero cases reported in Akatsi North and Ho West districts are consistent with a similar study by Hernandez-Bojorge et al, who observed no cases in the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador [34]. These two districts are rural and mountainous in nature and lack hospitals. Due to these features, it is possible that the awareness level of the disease, self-reporting and diagnostic capacity might be low. Other factors, such as environmental (vegetation, sanitation), weak surveillance and poor knowledge level of health staff on the disease, could all be influential factors in the zero incidence of cases in the two districts. It could also be that the zero cases in these districts are operational and the need for Mini Leprosy Elimination Campaign and rapid village assessments to validate the situation.

Implications of the findings

This study provides important information on the magnitude of leprosy in the Volta Region. It highlighted districts with high rates of reported cases that may require urgent attention to reduce or break transmission. It is worth stating that the findings might be an underestimation of the incidence of leprosy cases in the region since the data were derived from cases routinely reported to health facilities for treatment. Nevertheless, it is a good source of information that can guide health authorities in planning and implementing control programs to combat the disease. Targeted interventions such as active surveillance and community sensitization programs can be rolled out in areas with a high incidence of leprosy. Policy makers and partners can rely on the findings as an essential advocacy and lobbying tool to solicit funding and other resources to support leprosy elimination efforts. The findings may also serve as a basis for policymakers to design and implement training programs for Clinicians, Disease Control Officers and other relevant staff members to detect, report and manage leprosy cases in a timely manner to reduce disabilities. The results may also guide the allocation and efficient management of resources for control of the disease among high-risk groups and populations. The findings may trigger the reevaluation and strengthening of the leprosy surveillance system, case management and tracking mechanisms, community involvement and stigma control reduction strategies. These, in effect, will improve case identification, quality of care, patients’ adherence, reduce loss-to-follow-up and the overall treatment outcome of leprosy cases towards the Zero Leprosy Strategy.

Strengths and limitations

This study offers essential information on the geographical distribution, trends and treatment outcomes of leprosy cases in the Volta Region. Data was comprehensively analysed from reliable data sources at health facilities to provide accurate information for a clear understanding of the progress towards eliminating leprosy in the region. The study findings are vital to guide policy decisions on establishing care pathways to improve the quality of care and patient support systems. Furthermore, the findings will enable the implementation of targeted control interventions and efficient resource allocation that will significantly impact leprosy elimination in the region and Ghana at large. Key limitations of the study include the fact that the study results might be underestimated due to a lack of awareness of the disease, stigma, and poor access to health facilities can skew the findings. Also, since the surveillance data analysed was from hospital registry records and not an active surveillance system data, the real burden of the disease might have been underestimated. This is because only a few cases might have been reported to the hospital for care and treatment. The findings of the study may also not represent the general epidemiological picture of leprosy in Ghana since the study was limited to only the Volta Region. Lastly, the study did not explore geographical factors such as urbanization and climate conditions, personal, cultural, socio-economic variables and systemic challenges, which can influence the disease’s incidence, distribution and treatment outcome.

Conclusion

The study observed a declining incidence of leprosy cases in the region. However, the number lost to follow-up was high. Cases were predominant among older adults. Except for three districts, all other districts recorded cases with higher case concentration in the Ho and Hohoe Municipalities. There is a need for a linkage between treatment centres and community health nurses or community-based surveillance volunteers to help reduce the number of cases lost to follow-up. Also, strengthened community surveillance, patient tracking systems, decentralization of care, increased public education and targeted interventions are critical to eliminating leprosy in the Volta Region.

What is already known about the topic

- Leprosy (Hansen’s disease) is an ancient chronic disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae.

- It is an infectious, neglected tropical disease.

- Late detection of cases normally leads to major disabilities.

What this study adds

- There is a declining incidence of leprosy cases in the Volta Region; however, cases lost to follow-up are high.

- Leprosy cases in the Volta Region were predominant among older adults.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Heads of Health Facilities and District Health Directorates of the Volta Region for ensuring the data collection and recording. The authors are also thankful to the Regional Health Directorate of the Volta Region for granting permission to use the data for this study.

Authors´ contributions

CK, CK, VZ, MA and FB, were involved in the study’s conception and design. CK, CK, ZG, CAG, WAA, CST, GRI, MA, SAB and FB helped in the literature review. CK, CK, VZ, CAG, WAA, MA, SAB and IA, participated in the data acquisition and analysis. CK, CK, VZ, CAG, WAA, CST, GRI, MA, SAB, IA and FB, drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

List of abbreviations

CHPS: Community-based Health Planning and Services

CI: Confidence Interval

DHIMS: District Health Information Management System

G2G: Grade-2 Disabilities

GHS: Ghana Health Service

NTDs: Neglected Tropical Diseases

OPD: Outpatient Department

QGIS: Quantum Geographic Information System

WHO: World Health Organization

| Variables | Frequency (N = 82) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 41 | 50.0 |

| Female | 41 | 50.0 |

| Age, median (IQR), years | 55 (37–65) | |

| Age (years) | ||

| <25 | 5 | 6.1 |

| 25–34 | 11 | 13.4 |

| 35–44 | 13 | 15.9 |

| 45–54 | 10 | 12.2 |

| ≥55 | 43 | 52.4 |

| Residence of the case seen | ||

| Within the Volta Region | 79 | 96.3 |

| Outside the Volta Region | 3 | 3.7 |

| Year | ||

| 2019 | 17 | 20.7 |

| 2020 | 23 | 28.1 |

| 2021 | 27 | 32.9 |

| 2022 | 11 | 13.4 |

| 2023 | 4 | 4.9 |

| Class of Leprosy | ||

| Multibacillary (Mb) | 80 | 97.6 |

| Paucibacillary (Pb) | 2 | 2.4 |

| Disability Grading | ||

| Grade 0 | 72 | 87.8 |

| Grade 1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Grade 2 | 10 | 12.2 |

| Treatment outcome | ||

| Complete treatment | 58 | 70.7 |

| Died | 3 | 3.7 |

| Transferred out | 2 | 2.4 |

| Lost to follow-up | 19 | 23.2 |

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hansen’s Disease (Leprosy) [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/leprosy/about/index.html.

- World Health Organization. Key Facts on Leprosy [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leprosy.

- World Health Organization. The Global Health Observatory. Explore a World of Health Data [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho.

- World Health Organization. Global leprosy (Hansen disease) update, 2021: moving towards interruption of transmission. Weekly Epidemiological Record [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Dec 29];36:429–30. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-wer9736-429-450.

- Chen KH, Lin CY, Su S Bin, Chen KT. Leprosy: A Review of Epidemiology, Clinical Diagnosis, and Management. Journal of Tropical Medicine [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jtm/2022/8652062/.

- Chen L, Zheng D, Li M, Zeng M, Yang B, Wang X. Epidemiology and grade 2 disability of leprosy among migrant and resident patients in Guangdong: an unignorable continued transmission of leprosy. Frontiers in Public Health [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Dec 29];11(November):1–11. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10710308/.

- Ghana Health Service. Technical Guidelines for Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response in Ghana [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.gh/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Integrated-Disease-Surveillance-and-Response-Ghana-Guidelines.pdf.

- Richardus JH. Towards zero leprosy: Dream or vision? Indian J Med Res [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Dec 29]. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_304_21.

- World Health Organization. Leprosy [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/leprosy.

- Bakoubayi AW, Haliba F, Zida-Compaore WIC, Bando PP, Konu YR, Adoli L komla, Akpadja K, Alaglo K, Tchalim M, Patchali P, Djakpa Y, Amekuse K, Gnossike P, Gadah DAY, Ekouevi DK. Any resurgence of leprosy cases in the Togo’s post-elimination period? Trend analysis of reported leprosy cases from 2010 to 2022. BMC Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Dec 29];24(1):1–9. Available from: https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-024-09492-w doi: 10.1186/s12879-024-09492-w.

- Ghana Health Service. Contact Tracing: Ghana Perspective [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Dec 29];(October 2020):1–21.

- World Health Organization. Leprosy: Number of new leprosy cases 2023 [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: https://www.who.int/activities/monitoring-the-global-leprosy-situation.

- Quao B. Achieving the objectives of the Towards Zero Leprosy Strategy by 2030 in Ghana seems a realistic goal if current efforts continue [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: https://www.anesvad.org/en/historia/dr-quao-a-realistic-optimist-at-the-forefront-of-the-fight-against-leprosy-in-ghana/.

- Mrema G, Hussein A, Magoge W, Mmbaga V, Simba A, Balama R, Nkiligi E, Shunda P, Kamara D, Kisonga R, Kwesigabo G. Burden of leprosy and associated risk factors for disabilities in Tanzania from 2017 to 2020. PloS one [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Dec 29];19(10):e0311676. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0311676 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0311676.

- Shi Y, Sun PW, Wang L, Wang HS, Yu MW, Gu H. Epidemiology of Leprosy in China, 2021: An Update. International Journal of Dermatology and Venereology [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Dec 29];7(1):35–9. doi: 10.1097/JD9.0000000000000344.

- Gargi Sarode, Sachin Sarode, Rahul Anand, Shankargouda Patil, Mohammed Jafer, Hosam Baeshen KHA. Epidemiological aspects of leprosy [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559307/.

- Nyamogoba H, Mbuthia G, Mulambalah C. Endemicity and Increasing Incidence Of Leprosy In Kenya And Other World Epidemiologic Regions: A Review. African Journal of Health Sciences [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Dec 29];32(3):38–62. Available from: https://www.academia.edu/110658338/Endemicity_and_increasing_incidence_of_leprosy_in_Kenya_and_other_world_epidemiologic_regions_A_review.

- Shi Y, Sun PW, Wang L, Wang HS, Yu MW, Gu H. Epidemiology of Leprosy in China, 2021: An Update. International Journal of Dermatology and Venereology [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Dec 29];7(1):35–9. doi: 10.1097/JD9.0000000000000344.

- Haverkort E, van ‘t Noordende AT. Health workers’ perceptions of leprosy and factors influencing their perceptions in endemic countries: A systematic literature review. Leprosy Review [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Dec 29];93(4):332–47. Available from: https://leprosyreview.org/article/93/4/20-22036.

- Abbo AG, Migisha R, Amanya G, Kengonzi R, Turyahabwe S, Luzze H, Kwesiga B, Ario AR. Trends and distribution of Leprosy cases , Uganda , 2020 – 2024 , tracking progress towards elimination [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Dec 29];10(1):2020–4. Available from: https://event.fourwaves.com/onehealth2025/abstracts/ad6b91c3-5e50-4557-a375-6f31a43f4cbe.

- John AS, Karthikeyan G, Dutta A, Lal V, Arif MA, Raju MS. Leprosy Awareness, Knowledge and Attitude in the Community Across Three Endemic States in India: A Cross-sectional Study. Indian Journal of Leprosy [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Dec 29];93(3):271–80. Available from: https://www.ijl.org.in/pdf/05 AS John et al (271-280).pdf.

- Hambridge T, Chandran SLN, Geluk A, Saunderson P, Richardus JH. Mycobacterium leprae transmission characteristics during the declining stages of leprosy incidence: A systematic review. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0009436 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009436.

- Van‘t Noordende AT, Korfage IJ, Lisam S, Arif MA, Kumar A, Van Brakel WH. Correction: The role of perceptions and knowledge of leprosy in the elimination of leprosy: A baseline study in Fatehpur district, northern India (PLoS Negl Trop Dis). PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Dec 29];16(6):1–16. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0010519 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010519.

- Ghana Health Service. Ghana NTD Master Plan 2021 – 2025 [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: https://espen.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/content/document/Ghana NTD Master Plan 2021-2025.pdf.

- Ghana Health Service. Country NTD Master Plan 2021-25 [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: https://espen.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/content/document/Ghana NTD Master Plan 2021-2025.pdf.

- Butala CB, Cave RNR, Fyfe J, Coleman PG, Yang GJ, Welburn SC. Impact of COVID-19 on the neglected tropical diseases: a scoping review. Infectious Diseases of Poverty [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Dec 29];13(1):1–16. Available from: https://idpjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40249-024-01223-2 doi: 10.1186/s40249-024-01223-2.

- Matos TS, de Souza CDF, de Oliveira Fernandes TRM, Santos MB, de Brito RJVC, Matos DUS, do Carmo RF, da Silva TFA. Time trend and identification of risk areas for physical disability due to leprosy in Brazil: An ecological study, 2001-2022. BMC Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Dec 29];25(1). Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12879-025-10052-8.

- Pepito VCF, Amit AML, Samontina RED, Abdon SJA, Fuentes DNL, Saniel OP. Patterns and determinants of treatment completion and default among newly diagnosed multibacillary leprosy patients: A retrospective cohort study. Heliyon [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Dec 29];7(6):e07279. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405844021013827 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07279.

- Ghana Health Service. Leprosy Performance targets. Leprosy Control Program, Ghana Health Service [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Dec 29].

- Said AH, Mwanga H, Hussein AK. Trends in case detection rate for leprosy and factors associated with disability among registered patients in Zanzibar , 2018 – 2021. Bulletin of the National Research Centre [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: https://bnrc.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s42269-024-01258-3 doi: 10.1186/s42269-024-01258-3.

- Figueres-Pesudo B, Pinargote-Celorio H, Belinchón-Romero I, Ramos-Rincón JM. Comorbidities and Complications in People Admitted for Leprosy in Spain, 1997–2021. Life [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Dec 29];14(5):1–11. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-1729/14/5/586 doi: 10.3390/life14050586.

- Butlin CR. Excess of deaths of leprosy-affected people. Leprosy Review [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Dec 29];91(2):220–3. Available from: https://leprosyreview.org/article/91/2/22-0-223.

- Swetalina Pradhan, Rashid Shahid SS. Clinicoepidemiologic profile of leprosy in geriatric population in post-elimination era: A retrospective, hospital-based, cross-sectional study from Eastern India. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Dec 29]. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/jfmpc/fulltext/2023/12110/clinicoepidemiologic_profile_of_leprosy_in.2.aspx doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_940_23.

- Hernandez-Bojorge S, Gardellini T, Parikh J, Rupani N, Jacob B, Hoare I, Calvopiña M, Izurieta R. Ecuador Towards Zero Leprosy: A Twenty-Three-Year Retrospective Epidemiologic and Spatiotemporal Analysis of Leprosy in Ecuador. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Dec 29];9(10). Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2414-6366/9/10/246 doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed9100246.

- Wulan Dewanti Martamevia. Epidemiological overview of new cases of leprosy in West Java In 2021-2023, Indonesia. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Dec 29];22(3):1701–7. Available from: https://wjarr.com/content/epidemiological-overview-new-cases-leprosy-west-java-2021-2023-indonesia.

- Thompson AE, Anisimowicz Y, Miedema B, Hogg W, Wodchis WP, Aubrey-Bassler K. The influence of gender and other patient characteristics on health care-seeking behaviour: A QUALICOPC study. BMC Family Practice [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2025 Dec 29];17(1):1–7. Available from: https://bmcfampract.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12875-016-0440-0 doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0440-0.

- Deol AK, Fleming FM, Calvo-Urbano B, Walker M, Bucumi V, Gnandou I, Tukahebwa EM, Jemu S, Mwingira UJ, Alkohlani A, Traoré M, Ruberanziza E, Touré S, Basáñez MG, French MD, Webster JP. Schistosomiasis — Assessing Progress toward the 2020 and 2025 Global Goals. New England Journal of Medicine [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Dec 29];381(26):2519–28. Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1812165 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812165.

- Seidu AA, Darteh EKM, Agbaglo E, Dadzie LK, Ahinkorah BO, Ameyaw EK, Tetteh JK, Baatiema L, Yaya S. Barriers to accessing healthcare among women in Ghana: a multilevel modelling. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Dec 29];20(1):1–12. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/347436700_Barriers_to_accessing_healthcare_among_women_in_Ghana_a_multilevel_modelling.

- Osamor PE, Grady C. Women’s autonomy in health care decision-making in developing countries: A synthesis of the literature. International Journal of Women’s Health [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2025 Dec 29];8:191–202. Available from: https://www.dovepress.com/women39s-autonomy-in-health-care-decision-making-in-developing-countri-peer-reviewed-fulltext-article-IJWH.

- Seidu AA, Darteh EKM, Agbaglo E, Dadzie LK, Ahinkorah BO, Ameyaw EK, Tetteh JK, Baatiema L, Yaya S, Osamor PE, Grady C, Andaratu Achuliwor Khalid DLAI and AS, Lee Rose, Kumar Jessica and ANA. Women’s autonomy in health care decision-making in developing countries: A synthesis of the literature. International Journal of Women’s Health and Wellness [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Dec 29];8(2):1–12.

- Lee Rose, Kumar Jessica and ANA. Women’s Healthcare Decision-Making Autonomy by Wealth Quintile from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) in Sub-Saharan African Countries. International Journal of Women’s Health and Wellness [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2025 Dec 29];3(2):1–7. Available from: https://clinmedjournals.org/articles/ijwhw/international-journal-of-womens-health-and-wellness-ijwhw-3-054.php?jid=ijwhw doi: 10.23937/2474-1353/1510054.

- De Sousa Oliveira JS, Dos Reis ALM, Margalho LP, Lopes GL, Da Silva AR, De Moraes NS, Xavier MB. Leprosy in elderly people and the profile of a retrospective cohort in an endemic region of the Brazilian Amazon. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Dec 29];13(9):1–12. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0007709 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007709.

- Napoleão Rocha MC, Nobre ML, Garcia LP. Temporal trend of leprosy among the elderly in Brazil, 2001 – 2018. Revista Panamericana de Salud Publica/Pan American Journal of Public Health [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Dec 29];45:1–9. Available from: https://www.paho.org/journal/en/articles/temporal-trend-leprosy-among-elderly-brazil-2001-2018 doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2020.12.

- Silva MJA, Silva CS, Brasil TP, Alves AK, dos Santos EC, Frota CC, Lima KVB, Lima LNGC. An update on leprosy immunopathogenesis: systematic review. Frontiers in Immunology [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Dec 29];15(September):1–21. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1416177/full doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1416177.

- Theodorakis N, Feretzakis G, Hitas C, Kreouzi M, Kalantzi S, Spyridaki A, Kollia Z, Verykios VS, Nikolaou M. Immunosenescence : How Aging Increases Susceptibility to Bacterial Infections and Virulence Factors. Microorganisms [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Dec 29];1–18. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2607/12/10/2052 doi: 10.3390/microorganisms12102052.

- da Silva PHL, de Castro KKG, Mendes MA, Leal-Calvo T, Leal JMP, Nery JA da C, Sarno EN, Lourenço RA, Moraes MO, Lara FA, Esquenazi D. Presence of Senescent and Memory CD8+ Leukocytes as Immunocenescence Markers in Skin Lesions of Elderly Leprosy Patients. Frontiers in Immunology [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Dec 29];12(March):1–11. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.647385/full doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.647385.

- Dharmawan Y, Fuady A, Korfage I, Richardus JH. Individual and community factors determining delayed leprosy case detection: A systematic review. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Dec 29];15(8):1–17. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0009651 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009651.