Research | Open Access | Volume 9 (1): Article 25 | Published: 06 Feb 2026

Epidemiological situation of 2023 dengue fever outbreaks in ECOWAS Region: Implications for strengthening preparedness and response

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Tables

| Country | Number of cases | Number of deaths | Case fatality rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benin | 3 | 1 | 33.3 |

| Burkina Faso | 71,229 | 709 | 1.0 |

| Cabo Verde | 194 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Cote d’Ivoire | 321 | 3 | 0.9 |

| Ghana | 9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Guinea | 1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Mali | 808 | 34 | 4.2 |

| Nigeria | 14 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Senegal | 203 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Togo | 17 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Total | 72,799 | 748 | 1.0 |

| Age group (years) | Total cases | Percentage of total (%) | Countries contributing the highest numbers |

|---|---|---|---|

| <20 | 19,047 | 26.2 | Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Cabo Verde |

| 20–39 | 34,649 | 47.7 | Burkina Faso (dominant), Mali |

| 40–59 | 15,601 | 21.5 | Burkina Faso, Mali |

| 60–79 | 3,067 | 4.2 | Burkina Faso |

| ≥80 | 193 | 0.3 | Burkina Faso |

| Missing | 39 | 0.1 | |

| Gender Distribution | |||

| Male | 31,334 | 43.2 | Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Cabo Verde |

| Female | 41,262 | 56.8 | Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Cabo Verde |

| N | Disease | Benin | Burkina Faso | Cabo Verde | Côte d’Ivoire | The Gambia | Ghana | Guinea | Guinea-Bissau | Liberia | Mali | Niger | Nigeria | Senegal | Sierra Leone | Togo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anthrax | |||||||||||||||

| 2 | Chemical skin burns among Fishermen | |||||||||||||||

| 3 | Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus | |||||||||||||||

| 4 | Chikungunya | |||||||||||||||

| 5 | Dengue Fever | |||||||||||||||

| 6 | Diphtheria | |||||||||||||||

| 7 | Food Poisoning | |||||||||||||||

| 8 | Lassa Fever | |||||||||||||||

| 9 | Meningitis | |||||||||||||||

| 10 | Pertussis | |||||||||||||||

| 11 | Poliomyelitis (cVDPV2) | |||||||||||||||

| 12 | Rabies | |||||||||||||||

| 13 | Rift Valley Fever | |||||||||||||||

| 14 | Zika Virus | |||||||||||||||

| 15 | West Nile Valley | |||||||||||||||

| 16 | Yellow Fever | |||||||||||||||

| No of new Events | 2 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 0 | 2 | |

| Color Legend | |

|---|---|

| 1 outbreak | |

| >1 outbreak / epidemic | |

| Country | No. of Concurrent Outbreaks | Key Co-circulating Diseases (from Data) | Clinical Syndrome Group & Implications for Differential Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nigeria | 6 | Dengue Fever, Chikungunya, Meningitis, Diphtheria, Yellow Fever, Polio | Complex Mixed Syndromes. High risk of misdiagnosis between arboviruses (Dengue/Chikungunya/Yellow Fever) in the initial febrile phase. Meningitis and severe Dengue can present with similar neurological symptoms. Requires robust lab capacity for multiplex PCR and serological testing. |

| Senegal | 9 | Dengue Fever, Chikungunya, Rift Valley Fever, Zika Virus, Measles, Yellow Fever, Meningitis | Major Arboviral Overlap. A hotspot for syndromic overlap of mosquito-borne diseases (Dengue/Chikungunya/Zika/Yellow Fever/RVF), which are clinically indistinguishable without testing. Co-circulation with Measles (fever/rash) further complicates the picture for pediatric cases. |

| Burkina Faso | 4 | Dengue Fever, Meningitis, Diphtheria, Measles | Febrile & Rash Illnesses. While known as the Dengue epicenter, co-circulation with Meningitis (fever/headache) and Diphtheria/Measles (fever/rash) poses a significant challenge for frontline health workers. Differentiation from severe Dengue is critical. |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 4 | Dengue Fever, Chikungunya, Crimean-Congo HF, Measles | High-Pathogen Mix. Co-circulation of multiple arboviruses with a high-consequence viral hemorrhagic fever (CCHF). Initial presentation of fever and myalgia could be any of these, making strict infection prevention and control (IPC) protocols and early detection vital. |

| Mali | 3 | Dengue Fever, Yellow Fever, Chikungunya | Focused Arboviral Overlap. Experienced concurrent outbreaks of the three major Aedes-borne viruses. Public health messaging and clinical guidelines must emphasize the near-identical presentation of these diseases and the importance of vector control. |

| Ghana | 4 | Dengue Fever, Yellow Fever, Cerebrospinal Meningitis, Polio | Neurological & Febrile Syndromes. Overlap of arboviral fevers with diseases causing neurological symptoms like Meningitis and Polio. This necessitates a careful neurological examination in febrile patients, especially children. |

| Benin | 2 | Dengue Fever, Chikungunya | Dengue-Chikungunya Co-circulation. A classic and common co-circulation scenario. These two viruses frequently occur together and share vectors. Multiplex testing or clinical algorithms to distinguish severe Dengue risk from chronic Chikungunya |

Figures

Keywords

- Dengue Fever

- Outbreak

- Preparedness

- Response

- ECOWAS

Virgil Kuassi Lokossou1, Aishat Bukola Usman1,&, William Kofi Bosu1, Olivier Manigart1,2, Cedric Bationo3 , Felix Agbla1, Babacar Fall4, Damola Olajide1, Tomé CA1, , Issiaka Sombie1, Melchior Athanase Joel Codjovi Aïssi1

1West African Health Organization, Bobo Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 2School of Public Health, Université Libre de Bruxelles, 3INSERM, IRD, SESSTIM, ISSPAM, UMR1252, Faculty of Medicine, Aix Marseille University, 13005 Marseille, France, 4ECOWAS Regional Centre for Surveillance and Disease Control, Abuja, Nigeria

&Corresponding author: Aishat Bukola Usman, West African Health Organisation, Bobo Dioulasso Burkina Faso. Email: ausman@support.wahooas.org, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0952-4639

Received: 21 Sept 2025, Accepted: 03 Feb 2026, Published: 06 Feb 2026

Domain: Field Epidemiology, Outbreak Response

Keywords: Dengue Fever, Outbreaks, Preparedness, Response, ECOWAS

©Virgil Kuassi Lokossou et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Virgil Kuassi Lokossou et al., Epidemiological situation of 2023 dengue fever outbreaks in ECOWAS Region: Implications for strengthening preparedness and response. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2026; 9(1):25. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00201

Abstract

Introduction: The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) saw a significant rise in dengue fever (DF) outbreaks in 2023, presenting new challenges for public health systems. This paper outlines the epidemiological situation and highlights key challenges and implications for enhancing preparedness and response strategies in the region.

Methods: We characterised DF outbreaks in ECOWAS from January to December 2023 using a mixed-methods approach. This included: an extensive desk review of published and grey literature; quantitative analysis of data from a self-administered questionnaire completed by key informants in Member States(MS) to assess the epidemiological situation, response, and control efforts; and a qualitative synthesis of a two-day regional stakeholder meeting. Quantitative data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel and Epi Info version 7.2 to generate descriptive statistics. Missing data and reporting limitations were explicitly documented and discussed.

Results: Ten (66%) of the 15 Member States reported a total of 157,031 suspected cases, including 72,799 confirmed and probable cases and 748 deaths (overall case fatality rate [CFR]: 1.0%). Burkina Faso accounted for 98% of confirmed/probable cases (71,299) and 95% of fatalities. The highest CFR (33.3%) was reported in Benin. Among confirmed/probable cases, females (56.8%) and adults aged 20–49 years (47.5%) constituted the largest proportion. The predominant circulating viral serotypes were DENV-3 and DENV-1. Member States faced several health system, environmental, and coordination challenges

Conclusion: The 2023 dengue outbreaks in ECOWAS underscore the urgent need to strengthen surveillance, improve vector control interventions, enhance laboratory diagnostic capacity, and promote regional coordination. These findings should be interpreted considering limitations in data completeness and reporting consistency across countries.

Introduction

Dengue fever (DF) is a viral disease of major public health concern in tropical and sub-tropical regions due to its associated morbidity and mortality [1]. Caused by the dengue virus (DENV), which has four distinct serotypes (DENV1-4), DF is transmitted primarily through the bites of infected female Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. Transmission via blood transfusion has also been reported [2].

Globally, over 4.5 million cases and 4,000 deaths were reported from 80 countries as of early November 2023 [3]. While dengue epidemiology is well-characterized in the Americas and Asia, it remains poorly understood in Africa [4]. Limited awareness, ineffective surveillance, clinical overlap with other febrile illnesses like malaria, and scarce diagnostic tools contribute to this knowledge gap [5,6].

Since 1964, dengue epidemics have been reported in 15 African countries, involving all four serotypes, with DENV-1 and DENV-2 historically dominant [7]. DF is of particular importance for West Africa. Eleven ECOWAS countries have experienced outbreaks, with cases expanding from urban to rural settings since 2000 [8,9]. Factors such as urbanization, global travel and trade, waste accumulation, and insecticide resistance favor the breeding of Aedes vectors [10]. Climate change may further shift transmission dynamics, potentially favouring arboviruses like dengue over malaria [11]. Although three vaccine candidates (Sanofi, Takeda, and NIH/Bhutan/MSD) have been licensed, none has been evaluated in West Africa. Therefore, reactive vaccination campaigns are not currently feasible. [12]. Other regional challenges include misdiagnosis as malaria [13], limited laboratory capacity, inadequate surveillance, and general resource constraints.

The ECOWAS Regional Center for Surveillance and Disease Control (RCSDC) was established under the West African Health Organisation (WAHO) to strengthen disease surveillance, build resilience to epidemics, and coordinate preparedness and response across its 15 Member States [14]. This manuscript describes the epidemiological characteristics of the 2023 dengue outbreaks in the ECOWAS region and proposes evidence-informed recommendations for improving preparedness and response systems.

Methods

Study design and settings

This descriptive, cross-sectional study analysed the epidemiological situation of DF outbreaks in the ECOWAS region during 2023. It was conducted across the region, involving 10 of the 15 Member States that reported outbreaks: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, and Togo. The remaining five Member States (The Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Niger, and Sierra Leone) were excluded from the analysis due to the absence of reported dengue cases during the study period. This absence may reflect true low transmission, under-detection due to limited surveillance, or diagnostic constraints rather than a complete absence of the disease.

Participants and sampling

Participants included key stakeholders from National Public Health Institutions, International Health Regulations National Focal Points, laboratory officers, subject matter experts, non-governmental organizations, and first-line epidemic responders from the 15 ECOWAS countries. A purposive sampling approach was used. Each Member State was requested to nominate three to five respondents directly involved in dengue surveillance, outbreak investigation, laboratory diagnosis, or epidemic response during 2023.

Outbreak case definitions

Suspected case: Acute febrile illness (fever >38°C) lasting 2-7 days, accompanied by at least two symptoms: severe headache, pain behind the eyes, muscle/joint pain, rash, leucopenia, or hemorrhagic manifestations[15].

Probable case: A suspected case with the addition of one or more “warning signs,” including abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, mucosal bleeding, lethargy, or rapid fluid accumulation [2].

Confirmed case: A suspected or probable case that is laboratory-confirmed via IgM antibody detection, PCR, viral isolation, or IgG antibody rise[15].

Severe dengue: Defined by severe plasma leakage (leading to shock or fluid accumulation with respiratory distress), severe bleeding, or severe organ involvement (eg, liver, heart, brain)[15].

Variables

Primary variables: Number of probable and confirmed dengue fever cases, fatalities, circulating viral strains, and socio-demographic characteristics (age and gender).

Secondary variables: Response efforts (surveillance, laboratory testing, case management, vector control), challenges faced by health systems, and cross-border collaboration.

Data sources

- A self-administered questionnaire was emailed to representatives of National Public Health Institutions.

- A two-day online regional meeting involving ~100 participants, organized by the RCSDC.

- A desk review of situation reports, relevant literature, and consultations with international organizations.

Regional surveillance coordination and data flow within the ECOWAS/WAHO System

Routine public health surveillance in the ECOWAS region is coordinated through the ECOWAS Regional Centre for Surveillance and Disease Control (RCSDC) under the West African Health Organization (WAHO). At the country level, dengue surveillance data are generated through national integrated disease surveillance and response systems and consolidated by National Public Health Institutes and the International Health Regulations (IHR) National Focal Points.

Member States report aggregated outbreak and event-based surveillance through established regional reporting and information-sharing mechanisms; the ECOWAS data Dashboard is coordinated by WAHO. RCSDC serves as the regional hub for the collation, validation, and analysis of surveillance data, and sharing among Member States and with technical partners to support early warning, situational awareness, and coordinated preparedness and response in the ECOWAS region.

In the context of the 2023 dengue outbreaks, this routine regional surveillance architecture was used to collect national situation reports and questionnaire data from Member States, validate reported figures through direct communication with national surveillance and laboratory focal points, and consolidate regional epidemiological and response information. The resulting harmonized dataset was used to describe the epidemiological situation, response activities, and operational challenges associated with dengue outbreaks across ECOWAS Member States in this study.

Data management and analysis

Data validation: Submitted questionnaires were reviewed for completeness and cross-checked with official national situation reports and dashboard data. Discrepancies were clarified with national focal points. Data were harmonised and validated jointly by RCSDC and WAHO surveillance teams before analysis.

Missing data and reporting limitations: Missing data were assessed descriptively. Given heterogeneous reporting systems and the outbreak-response nature of the data, formal imputation techniques were not applied. Countries with incomplete data were retained to preserve regional representation; analyses were restricted to available data. The potential for reporting bias, particularly under-reporting in countries with weaker surveillance, was acknowledged as a key limitation affecting case counts and mortality estimates.

Quantitative data analysis: Data was cleaned and analyzed using Microsoft Excel and Epi Info 7.2. Descriptive statistics (frequencies, proportions, means, medians) summarize epidemiological indicators. Case fatality rates were calculated. Due to the aggregated nature of national-level data and the absence of individual-level variance measures, confidence intervals were not calculated. Instead, ranges and qualitative descriptions of uncertainty are provided for key estimates.

Qualitative data analysis: A detailed content analysis of data from the desk review and regional stakeholder meeting was conducted. Notes, transcripts, and reports were reviewed and coded manually to extract recurring themes related to outbreak coordination, surveillance, laboratory capacity, case management, vector control, and risk communication.

Ethical considerations

This study utilized aggregated, anonymized national surveillance data and stakeholder meeting outputs. According to the ECOWAS Regional Centre for Surveillance and Disease Control (RCSDC) and West African Health Organization (WAHO) guidelines, ethical approval was not required for secondary analysis of routine public health surveillance data. All data were handled confidentially and in accordance with WAHO data sharing protocols.

Results

Descriptive Data: Dengue Fever Distribution in the ECOWAS Region in 2023

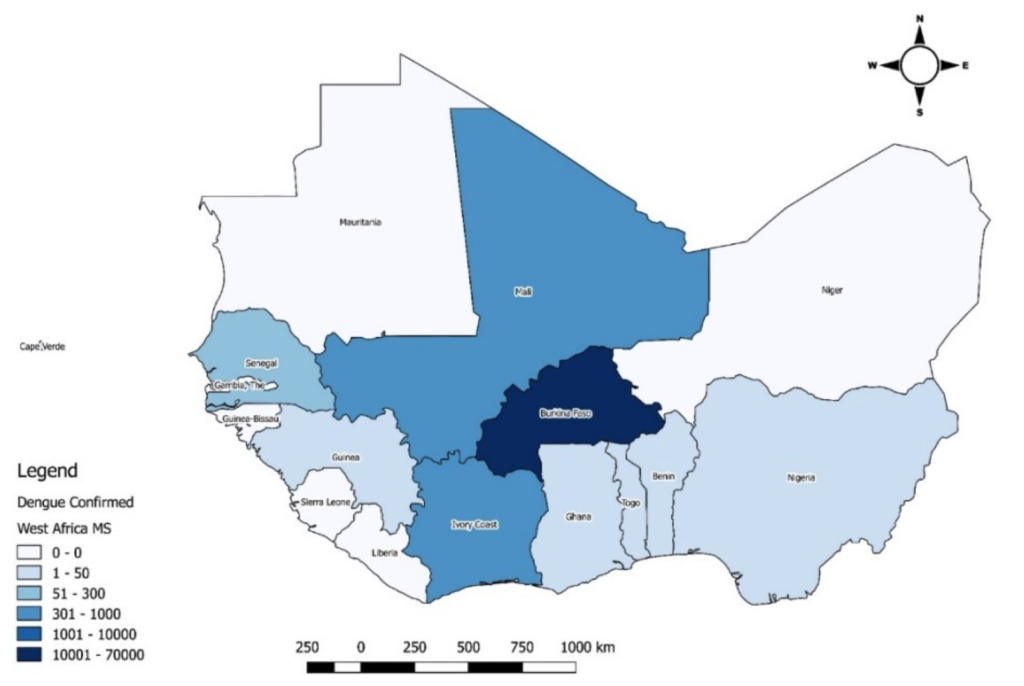

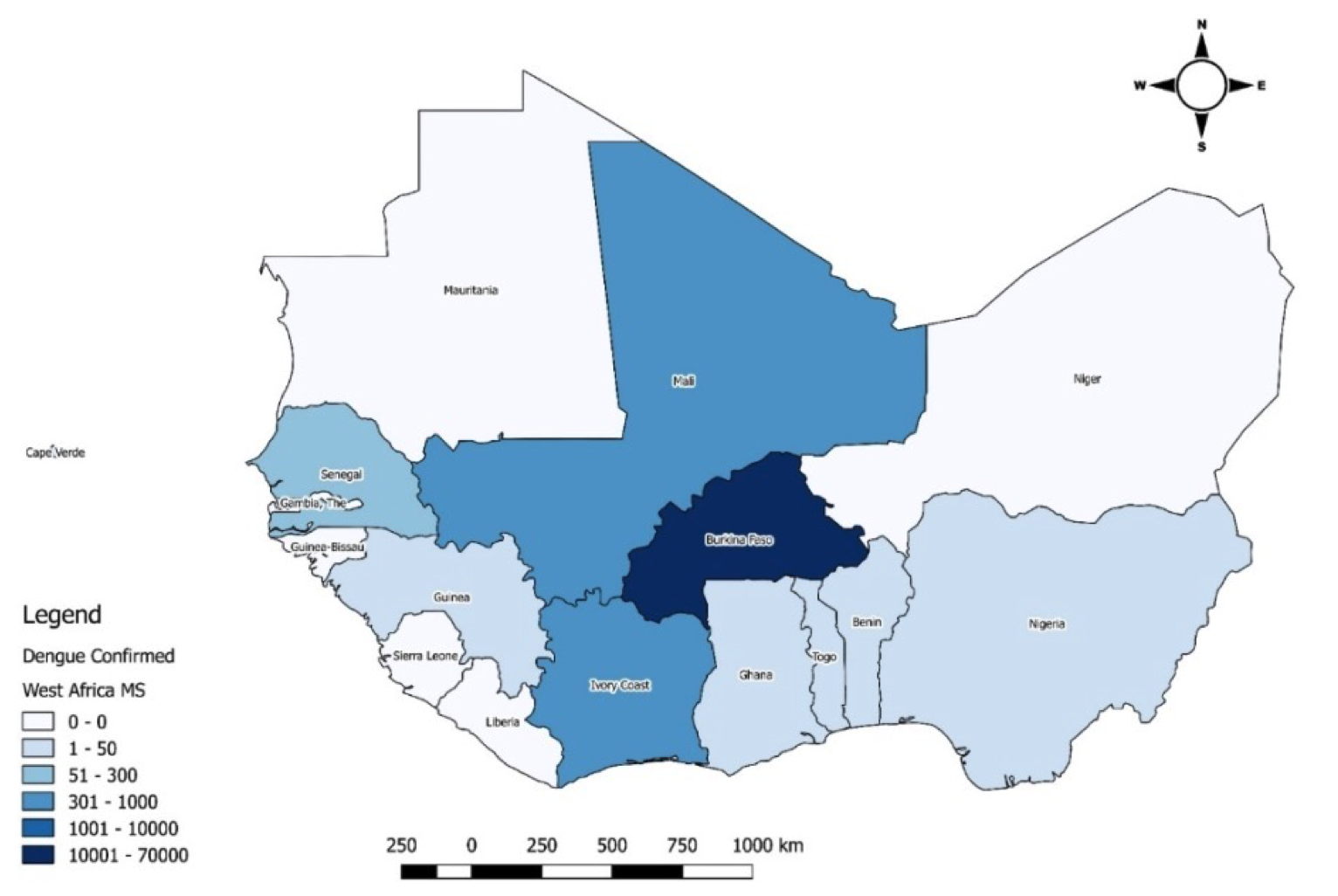

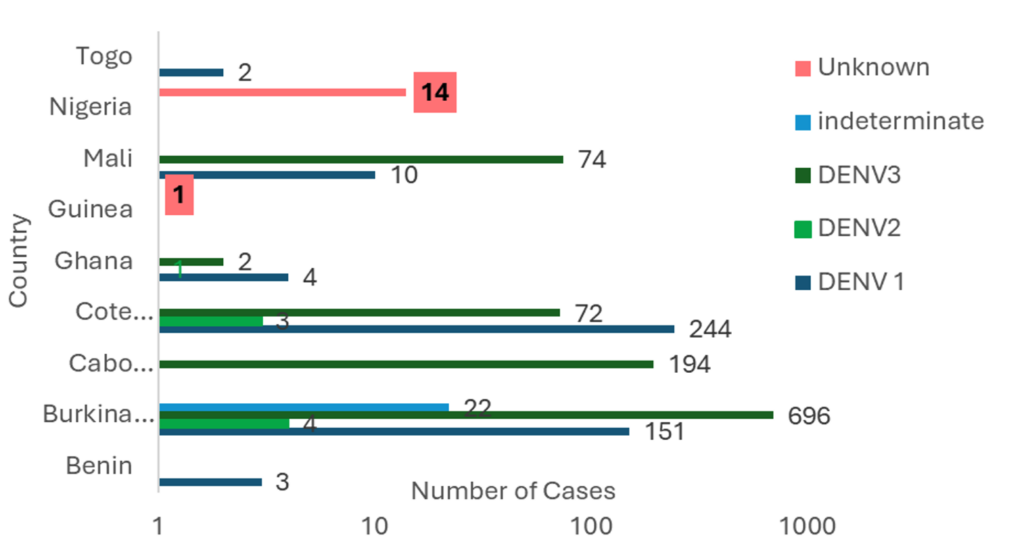

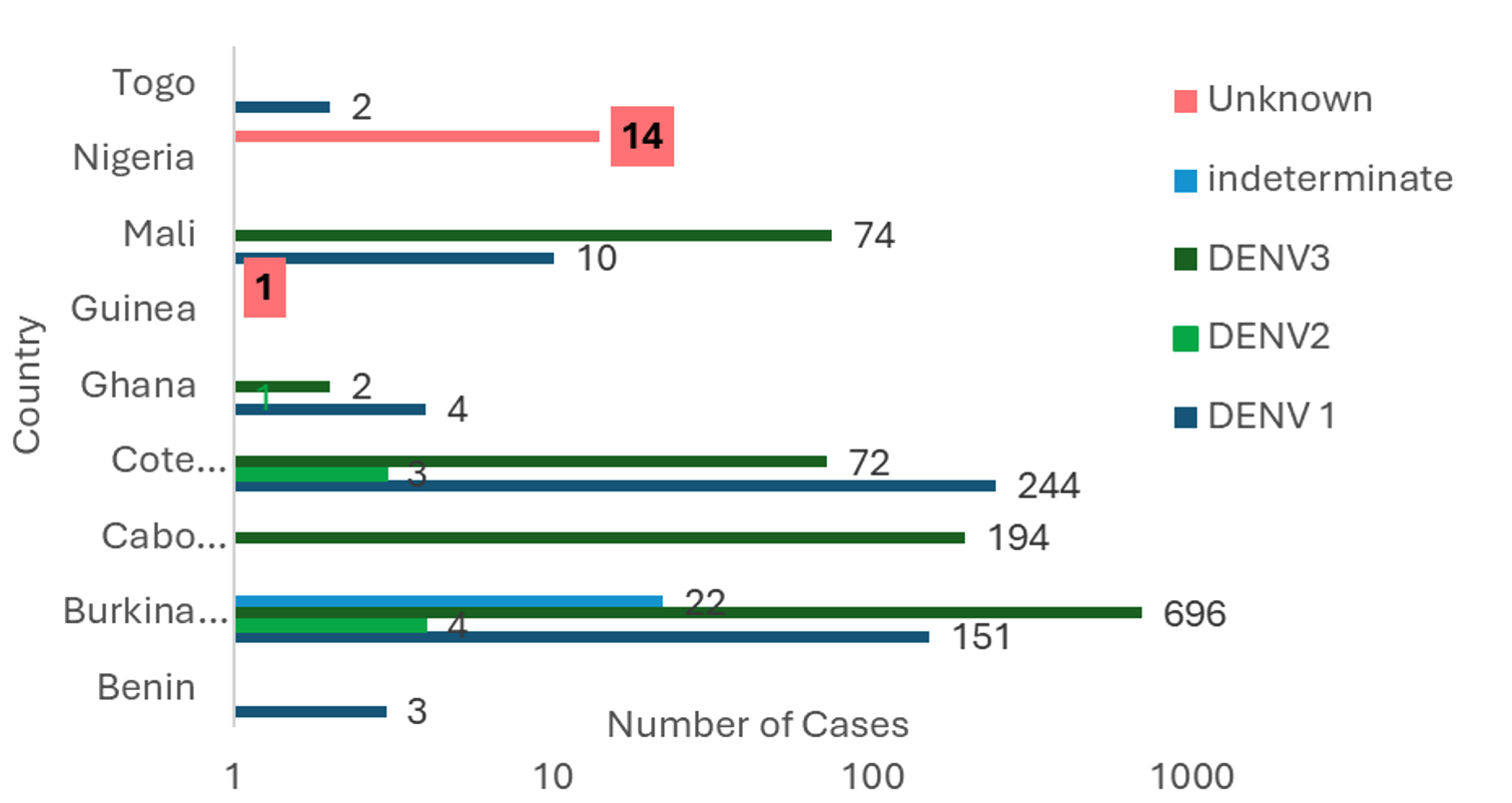

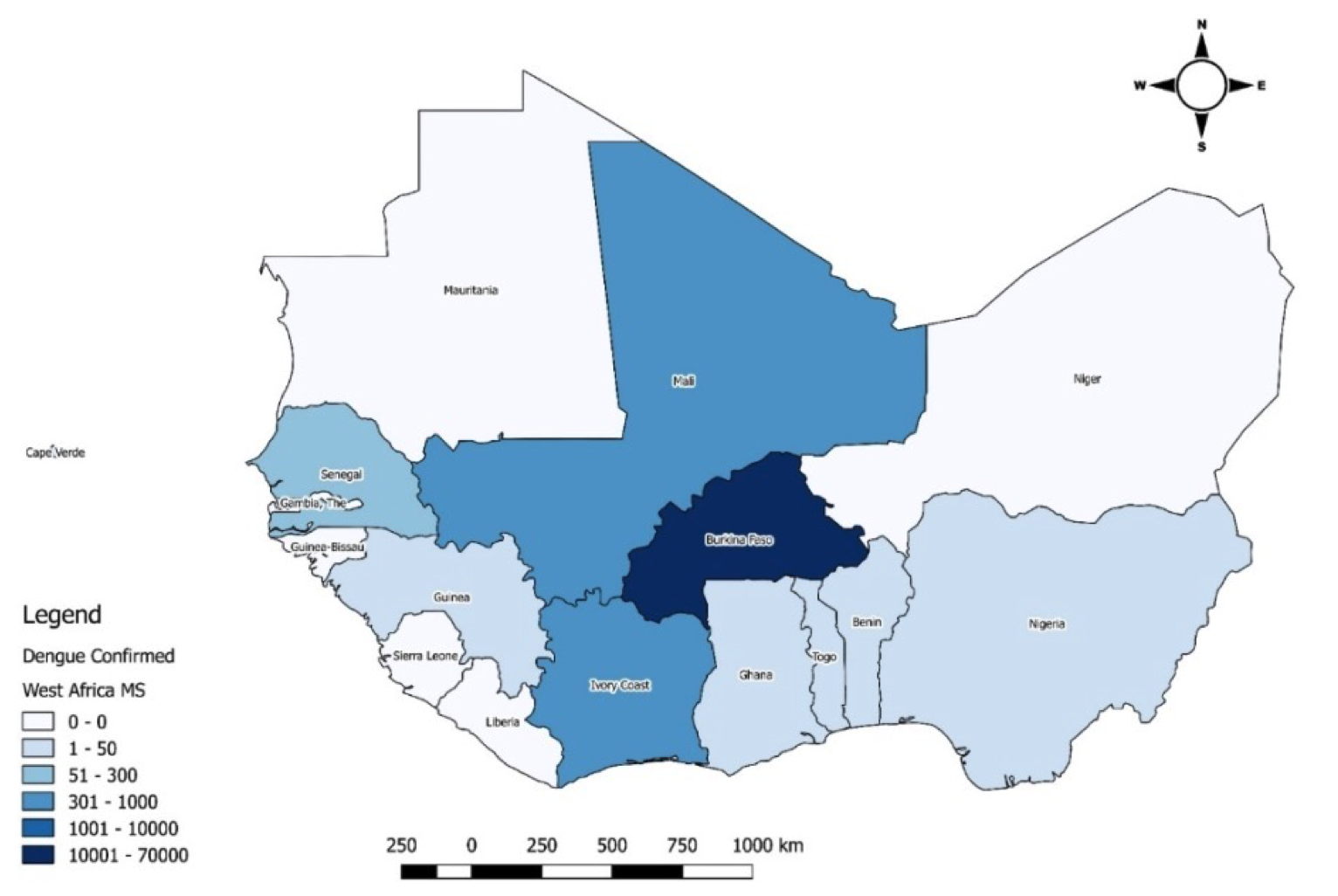

As of epidemiological week 52, 10 (66%) of the 15 ECOWAS Member States reported 157,031 suspected cases, 72,799 confirmed and probable cases, and 748 deaths (CFR 1.0%). Burkina Faso reported 71,299 (98%) of the cases and 709 (95%) of the deaths, followed by Mali (808 cases; 34 deaths) and Côte d’Ivoire (321 cases; 3 deaths). Benin reported the highest CFR (33.3%) (Table 1, Figure 1).

Sociodemographic characteristics of Dengue fever cases in ECOWAS 2023

Overall, females (56.8%) and individuals aged 20-39 years (47.5%) constituted the largest proportion of cases across the affected MS (Table 2). Cases were predominantly male in five countries. Most cases were in urban areas. The overall case fatality rate was 1.0% across ECOWAS, with significant variation by country. Burkina Faso had 709 deaths (CFR ~1.0%), while Benin reported a CFR of 33.3% based on limited data.

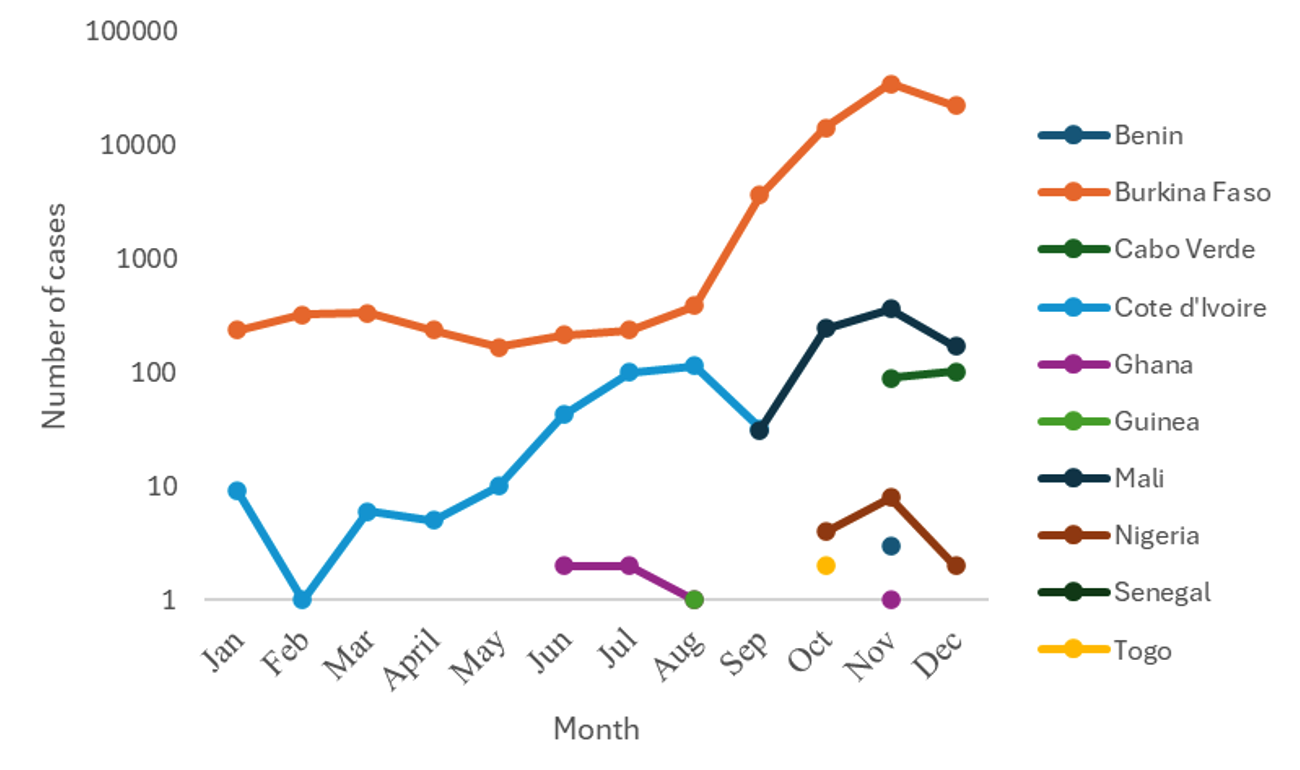

Temporal trends and serotype distribution

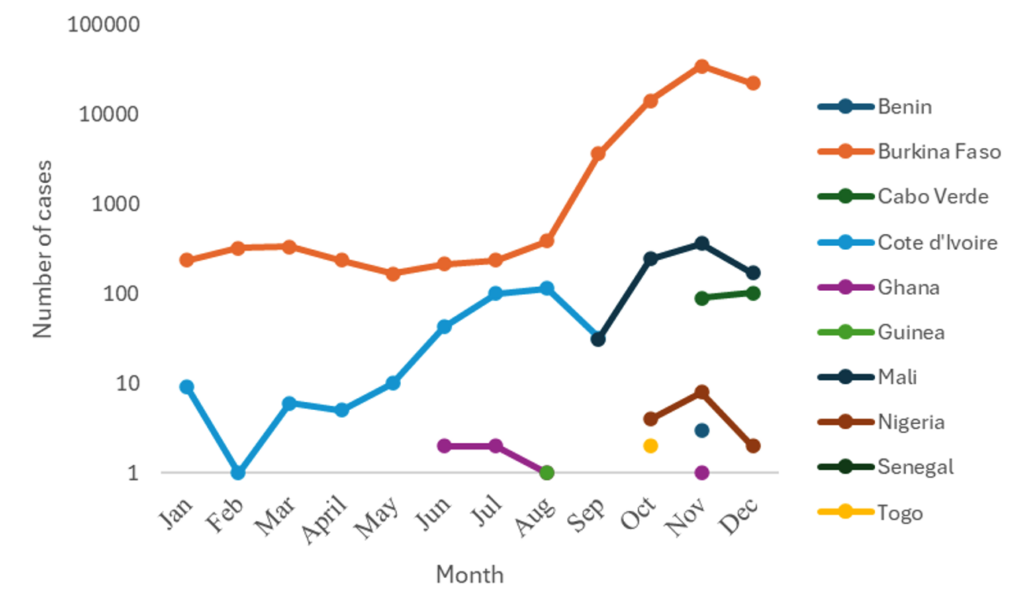

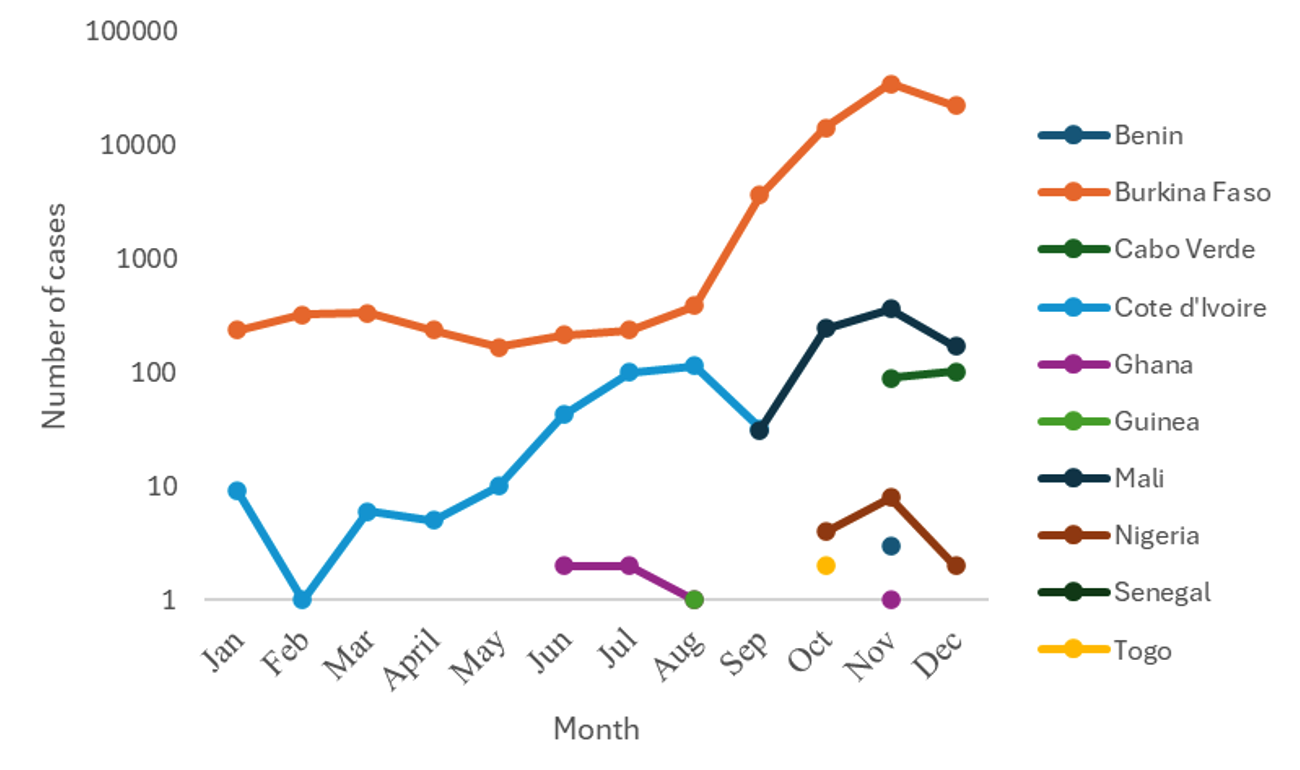

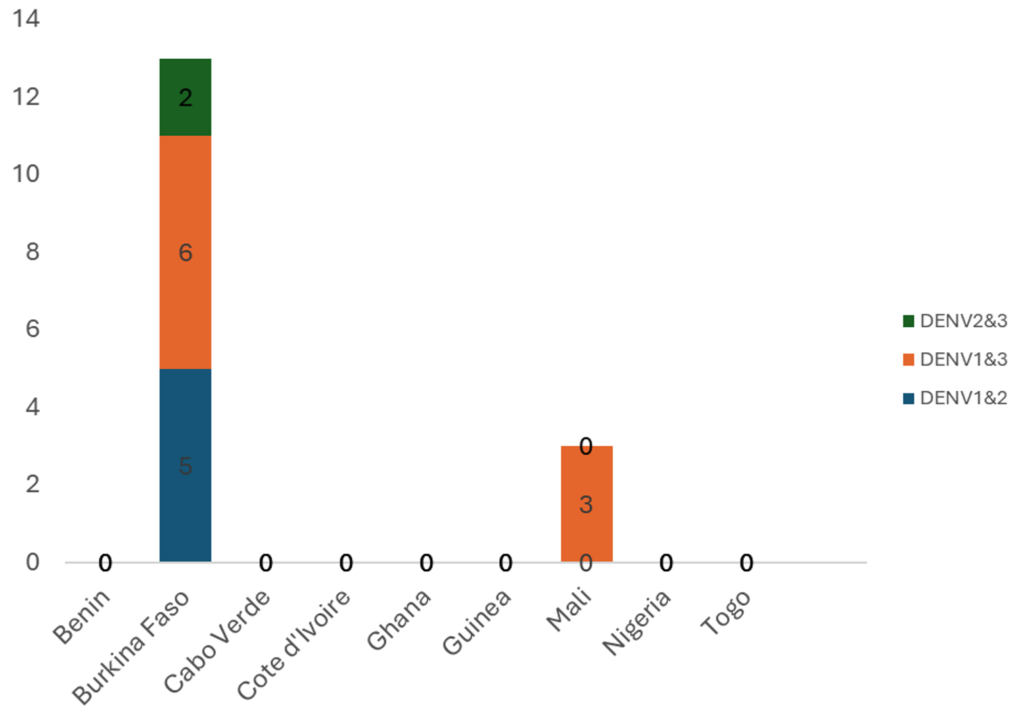

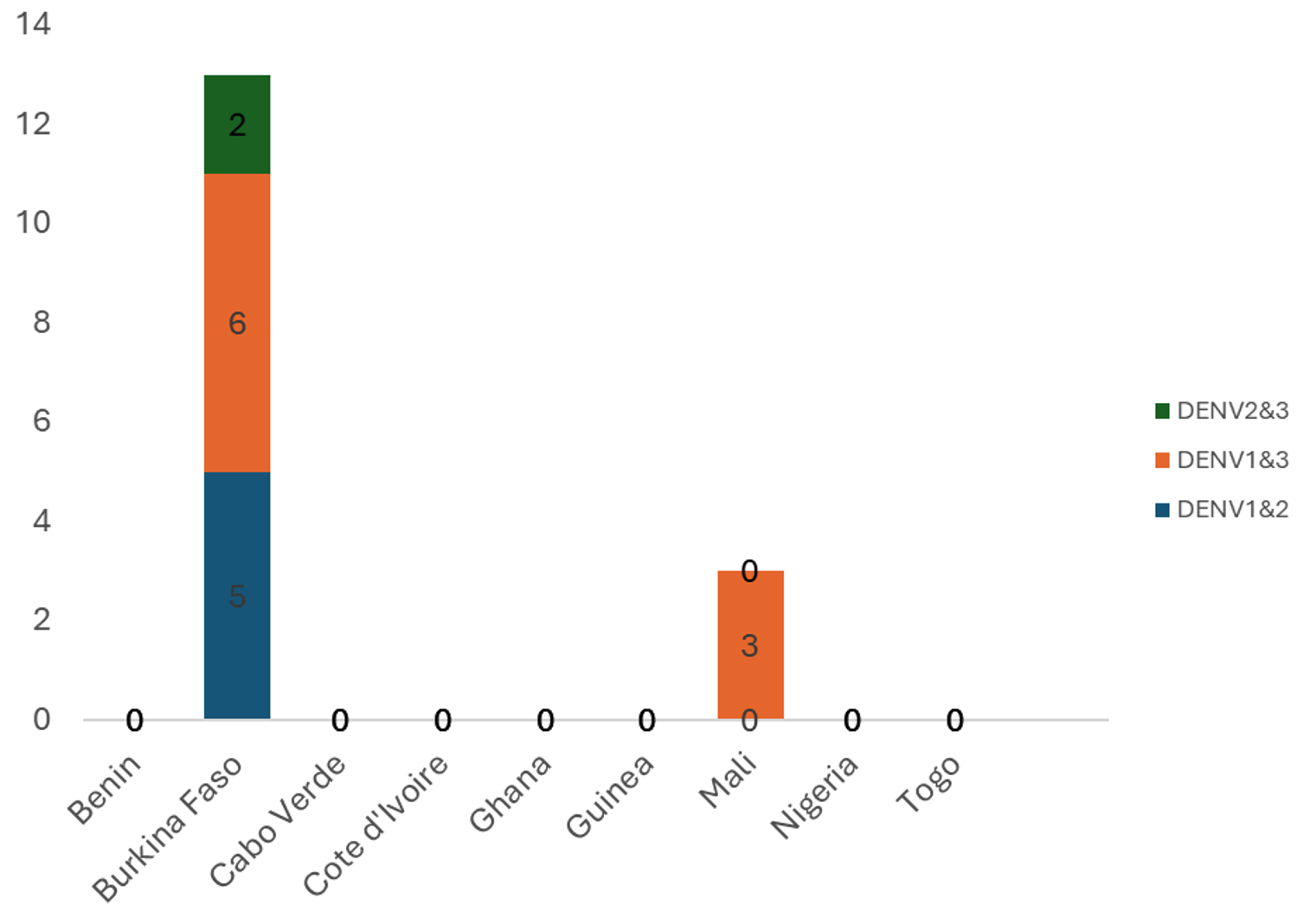

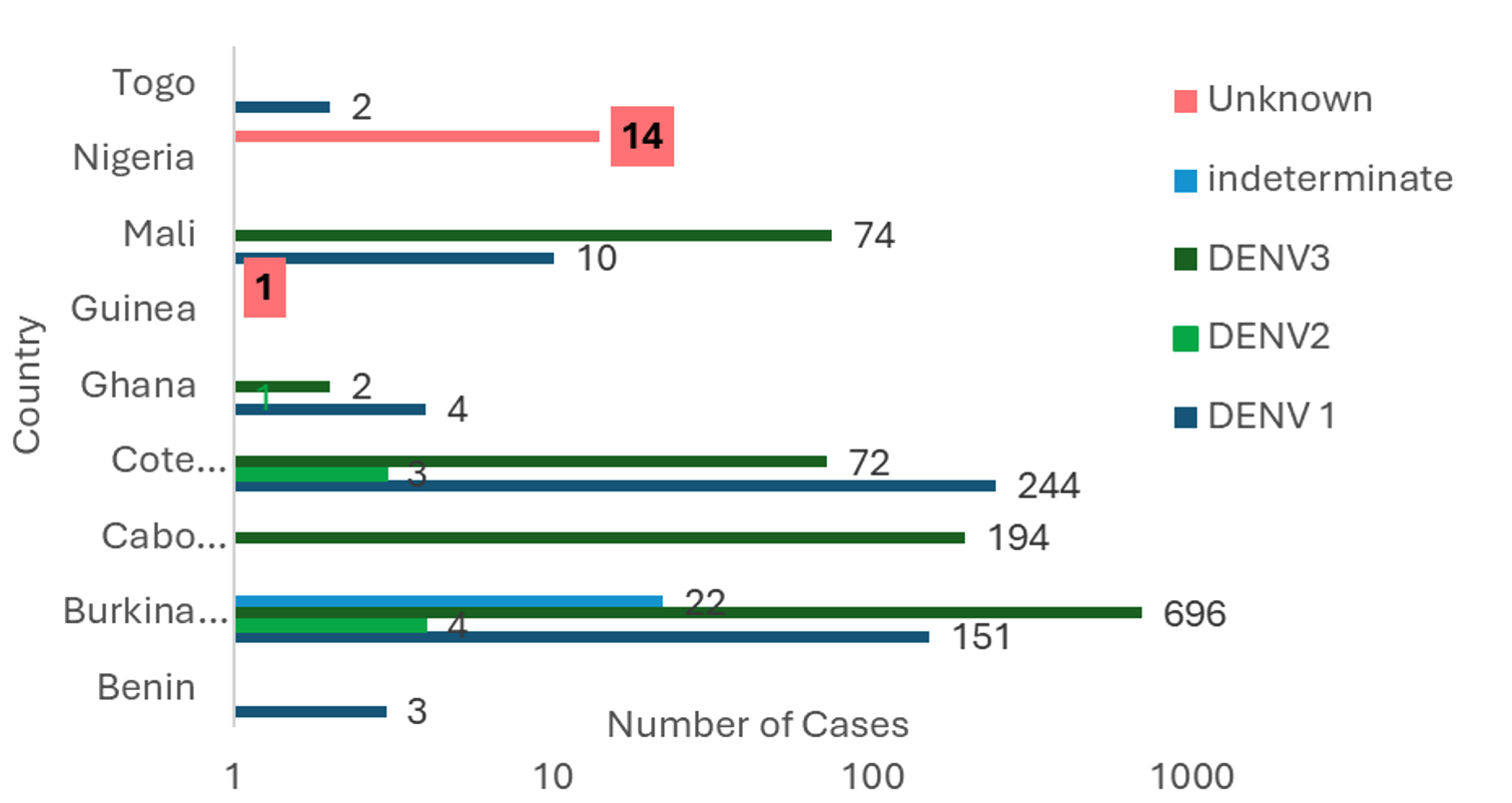

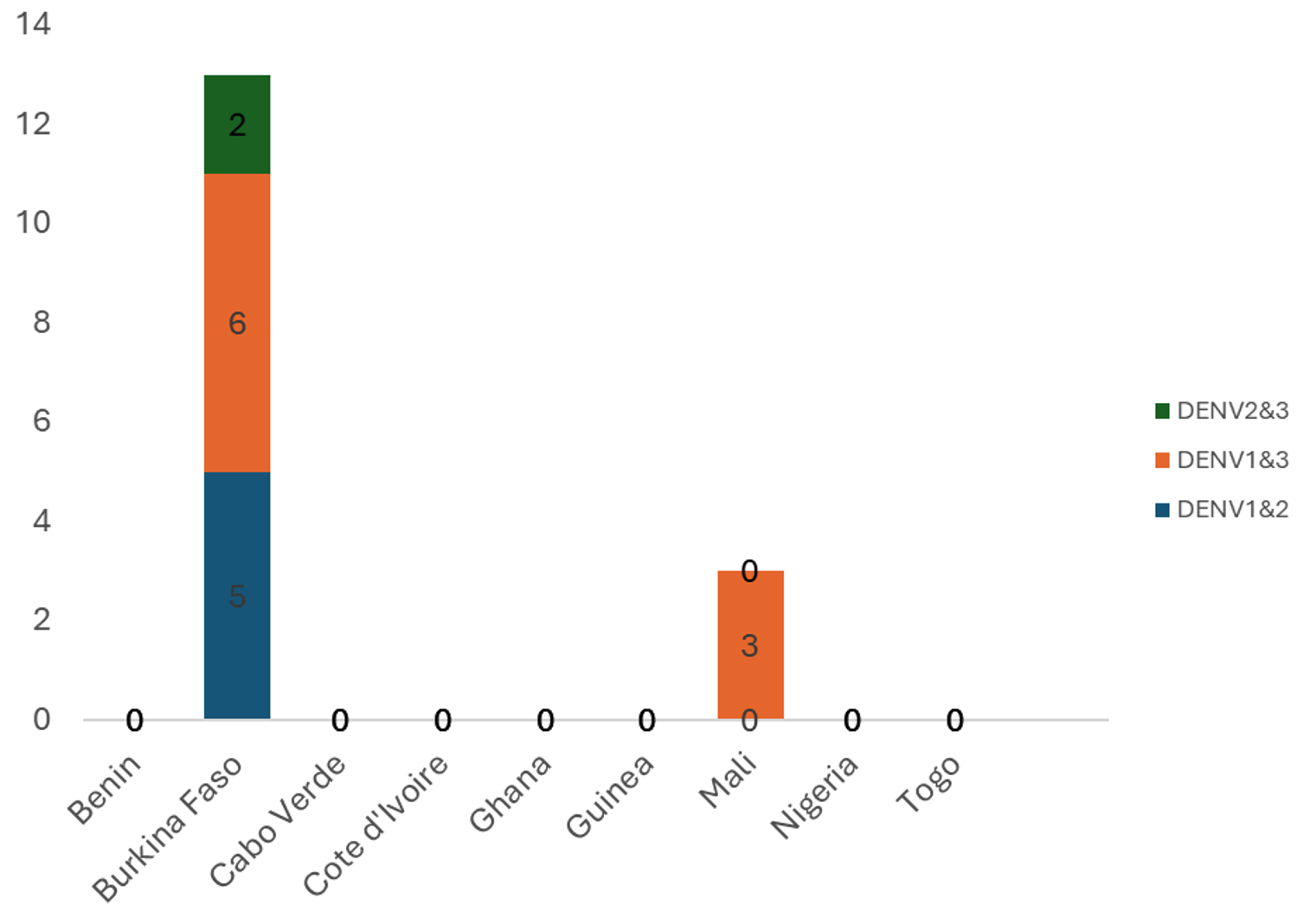

Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire reported cases throughout the year, with numbers increasing from September. The seven other countries reported cases for one to four months (Figure 2). All affected countries except Cabo Verde reported DENV-1. Burkina Faso and Ghana reported DENV-1, DENV-2, and DENV-3. Co-infections involving DENV-1 & DENV-3 were reported in Mali and Burkina Faso. Only Burkina Faso reported DENV-1&DENV-2 and DENV-2&DENV-3 co-infections (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Regional laboratory diagnostic and sequencing capacity for dengue in ECOWAS, 2023

During the 2023 dengue outbreaks, laboratory confirmation and virological characterization were supported by a limited number of national and regional reference laboratories within the ECOWAS region. Confirmatory diagnostic testing using PCR and/or ELISA was available in selected national public health and reference laboratories in Burkina Faso,, Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria, and Senegal.

Genomic sequencing and serotype determination were conducted in Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal, either through national reference laboratories or in collaboration with established regional and international laboratory partners.

Member States lacking in-country molecular diagnostic or sequencing capacity relied on sample referral to these reference laboratories through ad hoc or partner-supported transportation mechanisms. This laboratory network supported the identification of circulating dengue virus serotypes and co-infections reported in this study.

Co-occurrence of arboviral diseases

Other arboviral infections, including Chikungunya, Zika, and Lassa fever, were recorded in five Member States in 2023(Table 3). Senegal and Mali experienced simultaneous outbreaks of dengue, chikungunya, and Zika. Table 4 analyzes this co-circulation, highlighting the risk of clinical misdiagnosis due to syndromic overlap.

Response of ECOWAS Member States to dengue fever cases in 2023

- Coordination: Eight of ten(80%) affected MS activated emergency operation centers. Three (37.5%)had a pre-existing dengue contingency plan.

- Surveillance: All the affected MS (100%) strengthened surveillance and contact tracing using nationally approved dengue fever case definitions and guidelines. Four(40%) conducted sensitization campaigns for health facilities. Investigations and regular situation reports were produced in eight (80%) of the affected MS.

- Laboratory testing and sample transportation: Nine (90%)MS conducted confirmatory testing using rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs), PCR, or sequencing. Most used third-party sample transportation.

- Risk communication and community engagement: All ten MS issued press releases and conducted public awareness campaigns via multiple media channels.

- Clinical case management: Three MS (30%) had treatment algorithms; severe cases were referred to tertiary facilities. Free treatment was provided in two countries(20%).

- Vector control: Household and spatial spraying were implemented, along with larval source reduction campaigns in Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire. However, the capacity for vector control was sub-optimal in seven (70%) of the affected MS.

- Cross-border Collaboration: No MS held cross-border meetings or conducted joint surveillance exercises. Surveillance data sharing with neighboring countries was minimal

- Dengue Research: Four (40%) MS Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Cote d ‘Ivoire, and Nigeria had some research projects on dengue fever, assessing risk factors in their respective countries.

- ECOWAS and partners’ support: ECOWAS/WAHO provided USD1.15 million to Burkina Faso. The World Bank contributed USD5 million. WHO, UNICEF, USAID, and the Red Cross also provided technical and logistical support.

Discussion

This study provides a detailed characterization of the unprecedented 2023 dengue outbreaks in the ECOWAS region. These findings reveal a concentrated epidemic in Burkina Faso multi-serotype circulation and concurrent arbovirus outbreaks, which complicate clinical management. Critical gaps were identified in surveillance, laboratory capacity, and cross-border collaboration. These findings should be interpreted cautiously, as uncertainty around estimates could not be formally quantified across all countries. Nevertheless, descriptive patterns provide valuable operational insights for preparedness and response.

The WHO African region reported 1,843 public health emergencies (PHEs) between 2001 and 2022, and a 63% increase in zoonotic disease outbreaks in 2012-2022 compared to 2001–2011 [16]. A systematic review reported that severe dengue cases in Africa have been increasing in different countries [7], including Burkina Faso [17], Côte d’Ivoire [18], and Senegal [19].

The ten countries with ongoing outbreaks for emergency response in 2023 were classified as tier 1 risk index by WHO [20]. Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire reported cases every month in 2023, with peak cases in November. This pattern resembles an analysis of monthly dengue case data Bangladesh, which revealed peaks in August-October [21]. However, a recent study projected that climate warming could lead to year-round dengue transmission at the end of the 21st century [22].

The extreme concentration of cases in Burkina Faso suggests hyper-endemicity and established transmission cycles. In 2023, the observed increase in reported dengue cases during the second half of the year coincided with the main rainy season in several affected countries; however, this observation is based on a single year of data and should be interpreted cautiously. Similar associations between rainfall, seasonality, and dengue transmission have been reported in previous studies in other settings[23,24]. This predictable seasonality provides a clear window for pre-emptive public health action.

The absence of data from five ECOWAS countries may suggest under-reporting due to limited surveillance and diagnostic capacity rather than the true absence of DF. The confirmed presence of multiple serotypes, particularly in Burkina Faso and Ghana, increases the risk of severe dengue due to antibody-dependent enhancement.

This serotypic diversity necessitates a fundamental shift in case management and risk communication, moving from a perception of dengue as a one-time infection to a disease with potentially more severe outcomes in future outbreaks. Co-outbreaks of dengue with other viral hemorrhagic fevers have been reported in one-third of West African countries.

Co-outbreaks of dengue with other viral hemorrhagic fevers in one-third of West African countries highlight the insufficiency of syndrome-based reporting and the urgent need for integrated, laboratory-supported surveillance. Recent evidence from East Africa indicates the simultaneous circulation of DENV-1, DENV-2, and DENV-3, mirroring patterns observed in Burkina Faso and Ghana [25]. This underscores that multi-serotype co-circulation is a regional threat, not isolated to West Africa. Similarly, a 2023 Southeast Asian analysis highlighted how hyper-endemicity and climate anomalies can lead to explosive urban outbreaks [26]. The vulnerabilities exposed in the ECOWAS health systems, particularly diagnostic gaps and surveillance fragmentation, are consistent with systemic challenges documented in recent reviews of arbovirus preparedness in low-resource settings [27]. These contemporary comparisons reinforce that the 2023 ECOWAS outbreaks are part of a broader, intensifying trend of arboviral emergence in tropical regions, where urbanization, climate change, and health system constraints converge to amplify risk. A meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies in Africa reported that the prevalence of malaria-dengue co-infection ranges from 16 to 28.5 per 1000 febrile cases in West Africa [28]. This was corroborated by another systematic review that analyzed severe dengue in six countries between 2011 and 2019 [7]. It reported that malaria and dengue co-infections were the most prevalent, followed by dengue and chikungunya co-infections and other co-morbidities (yellow fever, measles, pancreatitis, and hepatitis E). These findings underscore the need to enhance differential diagnosis of non-malaria febrile illnesses and to implement an integrated arboviral response in West Africa.

Age and gender patterns observed in this study have important public health implications. Age is a key factor influencing dengue infection and progression to severe disease during the febrile phase [29]. The predominance of cases among adults aged 20–49 years shifts the disease burden to the economically productive population, amplifying societal and economic impacts.

Females accounted for a higher proportion of reported cases across the ECOWAS region. This finding is consistent with studies from South America, where female cases were equal to or exceeded those among males [30], and with data from Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, where more than half of dengue patients were female [31]. This pattern warrants further gender-sensitive analysis to determine whether it reflects differences in care-seeking behavior, biological susceptibility, or gender-specific exposure risks.

Strengths and Limitations

This analysis used a comprehensive, multi-method approach, integrating quantitative data with qualitative insights from a regional stakeholder meeting. The assessment of concurrent outbreaks across ECOWAS provides a crucial regional perspective.

Data was incomplete, with only ten of the fifteen ECOWAS MS reporting. The accuracy of national-level reporting could not be independently verified. The analysis could not classify cases by WHO severity guidelines, distinguish between primary and secondary infections, or calculate age-standardized incidence rates. The overwhelming concentration of cases in Burkina Faso limits the regional generalizability of some findings. Missing data were not imputed due to heterogeneous reporting, and potential reporting bias (particularly under-reporting) may affect case and mortality estimates. Sensitivity analyses were not feasible given data constraints.

Challenges faced during the 2023 dengue fever outbreak in the ECOWAS region

Challenges were categorised as health system, laboratory, environmental, epidemiological, and political.

Health system: Weak healthcare infrastructure, especially in politically unstable areas, and delayed detection and treatment. Limited diagnostic tools, treatment facilities, and trained staff hindered case management. Inadequate public awareness led to poor symptom recognition and self-medication.

Laboratory: Limited access to PCR and ELISA kits, high reagent costs, and reliance on unevaluated Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs) constrained confirmatory testing. Genomic sequencing was sporadic, performed only in Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Côte d’Ivoire, and Senegal.

Environmental: Climate change altered rainfall and temperature, favoring Aedes mosquito breeding. Poor sanitation and waste management further expanded breeding sites. Limited resources, weak infrastructure, and insecticide resistance hindered effective vector control efforts, complicating outbreak prediction and management.

Epidemiological: ECOWAS lacked regional dengue risk maps and an integrated arbovirus plan, impeding targeted interventions. Inadequate cross-border cooperation delayed outbreak detection. Insufficient research and epidemiological data limit the understanding of transmission dynamics and risk factors across the region.

Political: Regional political instability and security challenges in the three affected countries hindered access, cooperation, and importation of essential supplies.

Recommendations and policy implications

To improve dengue preparedness and response in West Africa, we propose the following prioritized recommendations:

- Immediate Actions:

- Evaluate all commercially available RDTs against gold-standard tests.

- Establish cross-border alert mechanisms and data-sharing protocols.

- Strengthen public awareness campaigns focusing on symptom recognition and prevention.

- Medium-Term Capacity Building:

- Strengthening laboratory networks for PCR, ELISA, and sequencing.

- Develop integrated arbovirus surveillance leveraging existing malaria platforms.

- Implement digital tools (e.g., GIS mapping, SMS reporting) for real-time surveillance.

- Long-Term Strategies:

- Develop a regional strategic plan for arboviruses under ECOWAS/WAHO.

- Incorporate climate change adaptation into national preparedness plans.

- Invest in operational research on vector bionomics, insecticide resistance, and DENV molecular epidemiology.

- Cross-Sectoral Collaboration:

- Leverage lessons from Ebola and COVID-19 responses (e.g., coordination pillars, community engagement).

- Foster partnerships between health, environment, education, and the private sectors.

- Advocate for sustained political commitment and funding for health security.

Conclusion

The 2023 dengue fever outbreaks represent a significant public health challenge for the ECOWAS region, revealing an escalation in arboviral threats. The unprecedented case burden, concentrated in Burkina Faso yet revealing regional vulnerabilities, indicates that dengue is a persistent public health issue. The co-circulation of multiple dengue serotypes may increase the risk of severe disease, while simultaneous outbreaks of other arbovirus strains occur in health systems.

The response exposed critical weaknesses in surveillance, diagnostics, and cross-border collaboration. These challenges present a clear agenda for action. The region must build a robust, integrated arbovirus defence system through sustained political commitment and investment in laboratory surveillance, data-driven vector control, and regional health security networks. By leveraging lessons learned and existing infrastructure, ECOWAS can build resilience against dengue and other emerging infectious diseases influenced by urbanization and climate change.

What is already known about the topic

- Dengue Fever is of significant public health concern in tropical and subtropical regions.

- West Africa hosts eleven of the 15 African countries that have reported dengue fever outbreaks since 1964.

What this study adds

- This study presents a comprehensive descriptive analysis of the 2023 Dengue Fever outbreaks and co-outbreaks in the ECOWAS region.

- Using multiple methods, including stakeholder meetings, it assesses the preparedness and response, funding support from partners, and challenges encountered by Member States.

- It represents the first regional synthesis integrating qualitative stakeholder insights with epidemiological data across ECOWAS.

| Country | Number of cases | Number of deaths | Case fatality rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benin | 3 | 1 | 33.3 |

| Burkina Faso | 71,229 | 709 | 1.0 |

| Cabo Verde | 194 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Cote d’Ivoire | 321 | 3 | 0.9 |

| Ghana | 9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Guinea | 1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Mali | 808 | 34 | 4.2 |

| Nigeria | 14 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Senegal | 203 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Togo | 17 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Total | 72,799 | 748 | 1.0 |

| Age group (years) | Total cases | Percentage of total (%) | Countries contributing the highest numbers |

|---|---|---|---|

| <20 | 19,047 | 26.2 | Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Cabo Verde |

| 20–39 | 34,649 | 47.7 | Burkina Faso (dominant), Mali |

| 40–59 | 15,601 | 21.5 | Burkina Faso, Mali |

| 60–79 | 3,067 | 4.2 | Burkina Faso |

| ≥80 | 193 | 0.3 | Burkina Faso |

| Missing | 39 | 0.1 | |

| Gender Distribution | |||

| Male | 31,334 | 43.2 | Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Cabo Verde |

| Female | 41,262 | 56.8 | Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Cabo Verde |

| N | Disease | Benin | Burkina Faso | Cabo Verde | Côte d’Ivoire | The Gambia | Ghana | Guinea | Guinea-Bissau | Liberia | Mali | Niger | Nigeria | Senegal | Sierra Leone | Togo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anthrax | |||||||||||||||

| 2 | Chemical skin burns among Fishermen | |||||||||||||||

| 3 | Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus | |||||||||||||||

| 4 | Chikungunya | |||||||||||||||

| 5 | Dengue Fever | |||||||||||||||

| 6 | Diphtheria | |||||||||||||||

| 7 | Food Poisoning | |||||||||||||||

| 8 | Lassa Fever | |||||||||||||||

| 9 | Meningitis | |||||||||||||||

| 10 | Pertussis | |||||||||||||||

| 11 | Poliomyelitis (cVDPV2) | |||||||||||||||

| 12 | Rabies | |||||||||||||||

| 13 | Rift Valley Fever | |||||||||||||||

| 14 | Zika Virus | |||||||||||||||

| 15 | West Nile Valley | |||||||||||||||

| 16 | Yellow Fever | |||||||||||||||

| No of new Events | 2 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 0 | 2 | |

| Color Legend | |

|---|---|

| 1 outbreak | |

| >1 outbreak / epidemic | |

| Country | No. of Concurrent Outbreaks | Key Co-circulating Diseases (from Data) | Clinical Syndrome Group & Implications for Differential Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nigeria | 6 | Dengue Fever, Chikungunya, Meningitis, Diphtheria, Yellow Fever, Polio | Complex Mixed Syndromes. High risk of misdiagnosis between arboviruses (Dengue/Chikungunya/Yellow Fever) in the initial febrile phase. Meningitis and severe Dengue can present with similar neurological symptoms. Requires robust lab capacity for multiplex PCR and serological testing. |

| Senegal | 9 | Dengue Fever, Chikungunya, Rift Valley Fever, Zika Virus, Measles, Yellow Fever, Meningitis | Major Arboviral Overlap. A hotspot for syndromic overlap of mosquito-borne diseases (Dengue/Chikungunya/Zika/Yellow Fever/RVF), which are clinically indistinguishable without testing. Co-circulation with Measles (fever/rash) further complicates the picture for pediatric cases. |

| Burkina Faso | 4 | Dengue Fever, Meningitis, Diphtheria, Measles | Febrile & Rash Illnesses. While known as the Dengue epicenter, co-circulation with Meningitis (fever/headache) and Diphtheria/Measles (fever/rash) poses a significant challenge for frontline health workers. Differentiation from severe Dengue is critical. |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 4 | Dengue Fever, Chikungunya, Crimean-Congo HF, Measles | High-Pathogen Mix. Co-circulation of multiple arboviruses with a high-consequence viral hemorrhagic fever (CCHF). Initial presentation of fever and myalgia could be any of these, making strict infection prevention and control (IPC) protocols and early detection vital. |

| Mali | 3 | Dengue Fever, Yellow Fever, Chikungunya | Focused Arboviral Overlap. Experienced concurrent outbreaks of the three major Aedes-borne viruses. Public health messaging and clinical guidelines must emphasize the near-identical presentation of these diseases and the importance of vector control. |

| Ghana | 4 | Dengue Fever, Yellow Fever, Cerebrospinal Meningitis, Polio | Neurological & Febrile Syndromes. Overlap of arboviral fevers with diseases causing neurological symptoms like Meningitis and Polio. This necessitates a careful neurological examination in febrile patients, especially children. |

| Benin | 2 | Dengue Fever, Chikungunya | Dengue-Chikungunya Co-circulation. A classic and common co-circulation scenario. These two viruses frequently occur together and share vectors. Multiplex testing or clinical algorithms to distinguish severe Dengue risk from chronic Chikungunya |

References

- Jane P. Messina, Oliver J. Brady, Nick Golding, Moritz U. G. Kraemer, G. R. William Wint, Sarah E. Ray, David M. Pigott, Freya M. Shearer, Kimberly Johnson, Lucas Earl, Laurie B. Marczak, Shreya Shirude, Nicole Davis Weaver, Marius Gilbert, Raman Velayudhan, Peter Jones, Thomas Jaenisch, Thomas W. Scott, Robert C. Reiner, Simon I. Hay. The current and future global distribution and population at risk of dengue. Nat Microbiol [Internet]. 2019 Jun 10 [cited 2026 Feb 5];4(9):1508–15. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41564-019-0476-8 doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0476-8

- Ester C. Sabino, Paula Loureiro, Maria Esther Lopes, Ligia Capuani, Christopher McClure, Dhuly Chowdhury, Claudia Di-Lorenzo-Oliveira, Lea C. Oliveira, Jeffrey M. Linnen, Tzong-Hae Lee, Thelma Gonçalez, Donald Brambilla, Steve Kleinman, Michael P. Busch, Brian Custer. Transfusion-Transmitted Dengue and Associated Clinical Symptoms During the 2012 Epidemic in Brazil. J Infect Dis [Internet]. 2016 Mar 1 [cited 2026 Feb 5];213(5):694–702. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jid/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/infdis/jiv326 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv326

- Global Health Press. Millions infected with dengue this year in a new record as hotter temperatures cause the virus to flare [Internet]. Singapore (Singapore): Global Health Press; 2023 Dec 27 [cited 2026 Feb 05]. Available from: https://id-ea.org/millions-infected-with-dengue-this-year-in-new-record-as-hotter-temperatures-cause-virus-to-flare/

- L Franco, A Di Caro, F Carletti, O Vapalahti, C Renaudat, H Zeller, A Tenorio. Recent expansion of dengue virus serotype 3 in West Africa. Eurosurveillance [Internet]. 2010 Feb 18 [cited 2026 Feb 5];15(7). Available from: https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/ese.15.07.19490-en doi: 10.2807/ese.15.07.19490-en

- Duane J. Gubler, Gary G. Clark. Dengue/Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever: The Emergence of a Global Health Problem. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 1995 Jun [cited 2026 Feb 5];1(2):55–7. Available from: http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/1/2/95-0204_article.htm doi: 10.3201/eid0102.952004

- Zékiba Tarnagda, Assana Cissé, Brice Wilfried Bicaba, Serge Diagbouga, Tani Sagna, Abdoul Kader Ilboudo, Dieudonné Tialla, Moussa Lingani, K. Appoline Sondo, Issaka Yougbaré, Issaka Yaméogo, Hyacinthe Euvrard Sow, Jean Sakandé, Lassana Sangaré, Rebecca Greco, David J. Muscatello. Dengue Fever in Burkina Faso, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2018 Jan [cited 2026 Feb 5];24(1):170–2. Available from: http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/24/1/17-0973_article.htm doi: 10.3201/eid2401.170973

- Gaspary O. Mwanyika, Leonard E. G. Mboera, Sima Rugarabamu, Baraka Ngingo, Calvin Sindato, Julius J. Lutwama, Janusz T. Paweska, Gerald Misinzo. Dengue Virus Infection and Associated Risk Factors in Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Viruses [Internet]. 2021 Mar 24 [cited 2026 Feb 5];13(4):536. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/13/4/536 doi: 10.3390/v13040536

- Athanase Badolo, Aboubacar Sombié, Félix Yaméogo, Dimitri W. Wangrawa, Aboubakar Sanon, Patricia M. Pignatelli, Antoine Sanon, Mafalda Viana, Hirotaka Kanuka, David Weetman, Philip J. McCall. First comprehensive analysis of Aedes aegypti bionomics during an arbovirus outbreak in west Africa: Dengue in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 2016–2017. Joseph T. Wu, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2022 Jul 6 [cited 2026 Feb 5];16(7):e0010059. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0010059 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010059

- Olivia Man, Alicia Kraay, Ruth Thomas, James Trostle, Gwenyth O. Lee, Charlotte Robbins, Amy C. Morrison, Josefina Coloma, Joseph N. S. Eisenberg. Characterizing dengue transmission in rural areas: A systematic review. Rebecca C. Christofferson, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2023 Jun 8 [cited 2026 Feb 5];17(6):e0011333. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0011333 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0011333

- Kristie L. Ebi, Joshua Nealon. Dengue in a changing climate. Environmental Research [Internet]. 2016 Nov [cited 2026 Feb 5];151:115–23. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0013935116303127 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2016.07.026

- Erin A Mordecai, Sadie J Ryan, Jamie M Caldwell, Melisa M Shah, A Desiree LaBeaud. Climate change could shift disease burden from malaria to arboviruses in Africa. The Lancet Planetary Health [Internet]. 2020 Sep [cited 2026 Feb 5];4(9):e416–23. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2542519620301789 doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30178-9

- Stephen J. Thomas. Is new dengue vaccine efficacy data a relief or cause for concern? npj Vaccines [Internet]. 2023 Apr 15 [cited 2026 Feb 5];8(1):55. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41541-023-00658-2 doi: 10.1038/s41541-023-00658-2

- Zeno Bisoffi, Dora Buonfrate. When fever is not malaria. The Lancet Global Health [Internet]. 2013 Jul [cited 2026 Feb 5];1(1):e11–2. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2214109X13700135 doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70013-5

- ECOWAS Commission. Regulations C/REG. 11/12/15 Establishing and stating operating procedures of the ECOWAS Regional Centre for Surveillance and Disease Control (ECOWAS – RCSDC), 13-14 December 2015 [Internet]. London (England): Oxford International Organizations; 2019 Apr 17 [cited 2026 Feb 05]. Available from: https://opil.ouplaw.com/display/10.1093/law-oxio/e467.013.1/law-oxio-e467

- World Health Organization. Dengue: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2009 Apr 21 [cited 2026 Feb 05]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241547871

- WHO Regional Office for Africa. In Africa, a 63% jump in diseases spread from animals to people seen in the last decade [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 30]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/news/africa-63-jump-diseases-spread-animals-people-seen-last-decade

- Kongnimissom Apoline Sondo, Adama Ouattara, Eric Arnaud Diendéré, Ismaèl Diallo, Jacques Zoungrana, Guelilou Zémané, Léa Da, Arouna Gnamou, Bertrand Meda, Armel Poda, Hyacinthe Zamané, Ali Ouédraogo, Macaire Ouédраogo, Blandine Thieba/Bonané. Dengue infection during pregnancy in Burkina Faso: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2019 Dec [cited 2026 Feb 5];19(1):997. Available from: https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-019-4587-x doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4587-x

- E.B.F. Aoussi, E. Ehui, N.A. Kassi, G. Kouakou, Y. Nouhou, E.V. Adjogoua, S. Eholié, E. Bissagnéné. Seven native cases of dengue in Abidjan, Ivory Coast. Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses [Internet]. 2014 Sep [cited 2026 Feb 5];44(9):433–6. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0399077X14002054 doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2014.08.002

- Ousmane Faye, Yamar Ba, Oumar Faye, Cheikh Talla, Diawo Diallo, Rubing Chen, Mireille Mondo, Rouguiétou Ba, Edgard Macondo, Tidiane Siby, Scott C. Weaver, Mawlouth Diallo, Amadou Alpha Sall. Urban Epidemic of Dengue Virus Serotype 3 Infection, Senegal, 2009. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2014 Mar [cited 2026 Feb 5];20(3). Available from: http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/20/3/12-1885_article.htm doi: 10.3201/eid2003.121885

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Weekly Regional Dengue Bulletin 001: 19 Dec 2023 [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2023 [cited 2026 Feb 05]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/375392

- Mohammad Sorowar Hossain, Abdullah Al Noman, Sm Abdullah Al Mamun, Abdullah Al Mosabbir. Twenty-two years of dengue outbreaks in Bangladesh: epidemiology, clinical spectrum, serotypes, and future disease risks. Trop Med Health [Internet]. 2023 Jul 11 [cited 2026 Feb 5];51(1):37. Available from: https://tropmedhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s41182-023-00528-6 doi: 10.1186/s41182-023-00528-6

- Kishor K Paul, Ian Macadam, Donna Green, David G Regan, Richard T Gray. Dengue transmission risk in a changing climate: Bangladesh is likely to experience a longer dengue fever season in the future. Environ Res Lett [Internet]. 2021 Nov 1 [cited 2026 Feb 5];16(11):114003. Available from: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ac2b60 doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ac2b60

- Kazi Mizanur Rahman, Yushuf Sharker, Reza Ali Rumi, Mahboob-Ul Islam Khan, Mohammad Sohel Shomik, Muhammad Waliur Rahman, Sk Masum Billah, Mahmudur Rahman, Peter Kim Streatfield, David Harley, Stephen P. Luby. An Association between Rainy Days with Clinical Dengue Fever in Dhaka, Bangladesh: Findings from a Hospital Based Study. IJERPH [Internet]. 2020 Dec 18 [cited 2026 Feb 5];17(24):9506. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/24/9506 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249506

- Fabrício Drummond Silva, Alcione Miranda Dos Santos, Rita Da Graça Carvalhal Frazão Corrêa, Arlene De Jesus Mendes Caldas. Temporal relationship between rainfall, temperature and occurrence of dengue cases in São Luís, Maranhão, Brazil. Ciênc saúde coletiva [Internet]. 2016 Feb [cited 2026 Feb 5];21(2):641–6. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-81232016000200641&lng=en&tlng=en doi: 10.1590/1413-81232015212.09592015

- Antonios Kolimenakis, Sabine Heinz, Michael Lowery Wilson, Volker Winkler, Laith Yakob, Antonios Michaelakis, Dimitrios Papachristos, Clive Richardson, Olaf Horstick. The role of urbanisation in the spread of Aedes mosquitoes and the diseases they transmit—A systematic review. Pattamaporn Kittayapong, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2021 Sep 9 [cited 2026 Feb 5];15(9):e0009631. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0009631 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009631

- Marcio R. T. Nunes, Gustavo Palacios, Nuno Rodrigues Faria, Edivaldo Costa Sousa, Jamilla A. Pantoja, Sueli G. Rodrigues, Valéria L. Carvalho, Daniele B. A. Medeiros, Nazir Savji, Guy Baele, Marc A. Suchard, Philippe Lemey, Pedro F. C. Vasconcelos, W. Ian Lipkin. Air Travel Is Associated with Intracontinental Spread of Dengue Virus Serotypes 1–3 in Brazil. Adalgisa Caccone, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2014 Apr 17 [cited 2026 Feb 5];8(4):e2769. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002769 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002769

- Marvina Rahman Ritu, Dana Sikder, Muhammad Mainuddin Patwary, Ashiqur Rahman Tamim, Alfonso J. Rodriguez-Morales. Climate change, urbanization and resurgence of dengue in Bangladesh. New Microbes and New Infections [Internet]. 2024 Jun [cited 2026 Feb 5];59:101414. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2052297524001987 doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2024.101414

- Annelies Wilder-Smith, Duane J Gubler, Scott C Weaver, Thomas P Monath, David L Heymann, Thomas W Scott. Epidemic arboviral diseases: priorities for research and public health. The Lancet Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2017 Mar [cited 2026 Feb 5];17(3):e101–6. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1473309916305187 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30518-7

- Sangkaew S, Ming D, Boonyasiri A, Honeyford K, Kalayanarooj S, Yacoub S, et al. Risk predictors of progression to severe disease during the febrile phase of dengue: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 Jul 1;21(7):1014–26. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30601-0

- Martha Anker, Yuzo Arima. Male-female differences in the number of reported incident dengue fever cases in six Asian countries. WPSAR [Internet]. 2011 Jul 5 [cited 2026 Feb 5];2(2):e1–e1. Available from: http://ojs.wpro.who.int/ojs/index.php/wpsar/article/view/118/37 doi: 10.5365/WPSAR.2011.2.1.002

- Valéry Ridde, Isabelle Agier, Emmanuel Bonnet, Mabel Carabali, Kounbobr Roch Dabiré, Florence Fournet, Antarou Ly, Ivlabèhiré Bertrand Meda, Beatriz Parra. Presence of three dengue serotypes in Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso): research and public health implications. Infect Dis Poverty [Internet]. 2016 Dec [cited 2026 Feb 5];5(1):23. Available from: http://www.idpjournal.com/content/5/1/23 doi: 10.1186/s40249-016-0120-2