Research | Open Access | Volume 9 (1): Article 05 | Published: 07 Jan 2026

COVID-19 vaccine program in Nigeria: A systematic review of newspaper reporting

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Google Scholar

Navigate this article

Tables

| Newspaper | Total Articles (n) | Positive Coverage (%) | Negative Coverage (%) | Neutral Coverage (%) | Common Themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Punch | 50 | 40 | 45 | 15 | Vaccine safety, Side effects, Government response |

| The Guardian | 42 | 50 | 30 | 20 | Immunity, Public awareness, Misinformation |

| Vanguard | 55 | 35 | 50 | 15 | Vaccine hesitancy, Misinformation, Access to vaccines |

| ThisDay | 38 | 45 | 40 | 15 | Economic impact, Global supply chains, Vaccine equity |

| Daily Trust | 33 | 30 | 55 | 15 | Religious concerns, Public skepticism, Myths about vaccines |

| Premium Times | 45 | 55 | 25 | 20 | Scientific research, Policy debates, Global vaccine efforts |

Table 1: Sentiment Analysis and Common Themes

| Category | Description | Thematic Responses | Frequency (n = 263) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine Position | Whether the article opposes, supports, or presents both views on vaccination | Pro-vaccine, Anti-vaccine, Both perspectives | Pro: 158 (60%), Anti: 46 (17.5%), Both: 59 (22.5%) |

| Evidence on Safety & Efficacy | Whether the article provides evidence supporting or questioning vaccine safety and efficacy | Scientific study cited, Expert opinion, No evidence provided | Scientific Study: 119 (45%), Expert Opinion: 105 (40%), No Evidence: 39 (15%) |

| Risks Mentioned (COVID-19 vs. Vaccine) | Whether the article discusses risks of COVID-19, vaccine, or both | COVID-19 complications, Vaccine side effects, Both, None | COVID–19 Complications: 125 (47.5%), Vaccine Side Effects: 79 (30%), Both: 33 (12.5%), None: 26 (10%) |

Table 2: Thematic Analysis of the Newspaper Articles

| Sources Cited | Citation Rate (%) | Coverage Bias |

|---|---|---|

| Scientists | 40% | Mostly Neutral or Positive |

| Government Agencies | 30% | Mixed |

| Activists / NGOs | 35% | Mostly Negative |

| WHO | 25% | Mostly Negative |

| Medical Experts or Healthcare Professionals | 20% | Mostly Positive |

| Public Figures (Opinion Leaders, Public Personalities, Influencers, and Top Politicians) | 10% | Mostly Negative |

| Citizens | 3% | Mostly Positive |

Table 3: Source Attributions in COVID-19 News Coverages

Figures

Keywords

- COVID-19

- Vaccine

- Nigeria

- Newspaper

- Articles

- Vaccination

Olalekan Isaac Olatunde1,&, Olusola Olalekan Elekofehinti2, Joel Emmanuel3

1Institute of Advanced Clinical Sciences Education, University of Medical Sciences, Ondo, Ondo State, Nigeria, 2Bioinformatics and Molecular Biology Unit, Department of Biochemistry, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria, 3Department of Radiology, Bioclinix Medical Diagnostics Centre, Lagos Nigeria

&Corresponding author: Olalekan Isaac Olatunde, Department of Health Law and Policy, Faculty of Health Law and Humanities, University of Medical Sciences, Laje Road, Ondo, Ondo State, Email: Reachout2isaac@gmail.com, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3975-2360

Received: 29 Oct 2025, Accepted: 04 Jan 2026, Published: 07 Jan 2026

Domain: COVID-19 Pandemic, Risk Communication

Keywords: COVID-19, Vaccine, Nigeria, Newspaper, Articles, Vaccination

©Olalekan Isaac Olatunde et al Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Olalekan Isaac Olatunde et al., COVID-19 vaccine program in Nigeria: A systematic review of newspaper reporting. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;9(1):05. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00260

Abstract

Introduction: The COVID-19 vaccination program in Nigeria commenced on March 5, 2021, and garnered substantial media attention and extensive coverage in national newspapers. This study aimed to examine the portrayal of COVID-19 vaccination in Nigerian media.

Method: A quantitative content analysis of 263 articles from major Nigerian newspapers published between January 2020 and December 2023 was conducted to examine the evidence presented on vaccination, perceived risks of COVID-19, and the overall tone of media coverage related to COVID-19 vaccination in Nigeria. Using relevant keywords, articles were retrieved through Google News, Google Search, and PressReader from newspapers including Punch, Vanguard, Daily Trust, Premium Times, and The Whistler, selected for their extensive national reach and readership. The content of the articles was systematically reviewed and analyzed. Data for this study were analyzed using quantitative thematic content analysis and descriptive statistical techniques to systematically examine patterns in newspaper coverage of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Results: Of the 263 articles reviewed, 60% (158/263) of media coverage was pro-vaccine, while 17.5% (46/263) was anti-vaccine and 22.4% (59/263) presented a balanced view of both perspectives. Some of the platforms cited evidence from scientific studies in 44.9% (118/263) of the articles and expert opinions in 40% (105/263), while 15% (40/263) provided no evidence. Regarding risk communication, articles primarily emphasised COVID-19 complications in 47.5% (125/263) of the articles and vaccine side effects in 30% (79/263). scientists and medical professionals were the most common and positively framed sources, whereas attributions to government agencies, non-governmental organizations, and international health bodies were frequently linked to mixed or negative sentiments.

Conclusion: Nigerian newspapers generally portrayed COVID-19 vaccination positively, although some reports have contributed to skepticism regarding vaccine safety. These findings demonstrate the role of media framing in shaping trust in the public. Future studies should explore how such portrayals influence vaccination behaviour and policy outcomes in Nigeria.

Introduction

In December 2019, an outbreak of a new and virulent strain of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was first reported in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei, China. SARS-CoV-2 (now referred to as COVID-19) spread rapidly across many countries in early 2020 [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) on January 30, 2020 [2]. It was first reported in Lagos State, Nigeria, in February 2020. Following a comprehensive assessment of its impact and spread, the WHO officially declared it a global pandemic on March 11, 2020 [3]. As of March 28, 2021, Nigeria has recorded a total of 162,593 confirmed cases, with a cumulative death toll of 2,048. Lagos remained at the epicenter of the pandemic, accounting for 35.4% of the cases in Nigeria [4]. Reports of COVID-19 vaccine development began to appear in the media, and the first COVID-19 vaccine, the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine, was developed in the UK. It was administered outside the clinical trial setting on December 8, 2020 [5]. The vaccine was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on August 13, 2021, for individuals aged 16 years and older [6]. Mass COVID-19 vaccination clinics were established, and guidelines and best practices were developed to guide their operations [7]. Following the rapid development and emergency approval of COVID-19 vaccines globally [8], several countries have faced challenges not only in procurement and distribution, but also in public acceptance [9]. However, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) face enormous challenges in procurement, distribution, allocation, and uptake of vaccines. Inequities in vaccine supply and access are already evident in resource-rich nations, which have secured a large amount of available vaccine doses for 2021 [9]. While international efforts, such as COVAX, sought to promote equitable access to vaccines, national responses were shaped by local socio-political contexts. However, COVAX efforts alone have not been enough to reverse or significantly reduce the inequality of the total COVID-19 vaccine distribution [10], especially in Sub-Saharan Africa. Nigeria, like many other developing nations, faces multiple challenges in vaccine rollout, including limited access to doses, infrastructural deficits in vaccine storage and distribution, and administrative bottlenecks. Beyond these logistical issues, the success of vaccination efforts in Nigeria has also been influenced by long-standing issues of vaccine hesitancy [11], varying levels of trust in health institutions, and the widespread circulation of misinformation and conspiracy theories in the media [12].

To better understand how these factors interacted and shaped public response to vaccination campaigns, it is essential to situate them within Nigeria’s broader national, demographic and economic context. Nigeria is a federal republic situated in West Africa, sharing borders with Cameroon and Chad to the east, Niger to the North and Benin to the west. Its southern coastline is along the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean [13]. Nigeria is composed of 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), Abuja, is located [14]. With approximately 237 million inhabitants [15], Nigeria has the largest population on the African continent and ranks as the eighth most populous country globally [16]. While Nigeria has the biggest economy in Africa, its large GDP Per Capita has not translated into an improved standard of living for its populace, and many Nigerians still find it difficult to afford basic necessities such as food, housing, and healthcare [17].

According to the Nigeria’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), 30.9% of Nigerians lived below the international extreme poverty line of $2.15 per person per day[18] (2017 Purchasing Power Parity [PPP]) in 2018 and 2019 before the COVID-19 pandemic [19]. Healthcare remains significantly underfunded, representing only 5.18% of Nigeria’s total budget, which falls well short of the 15% allocation target established by the Abuja Declaration [20].

Nigeria recorded the second-highest number of zero-dose children globally, with an estimated 2.25 million in 2021 [21]. The COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent vaccination campaign affected various aspects of the country’s healthcare system, including routine childhood immunization. As a result of this low vaccination coverage in Nigeria, outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases such as tuberculosis, diphtheria, pneumonia, and measles have continued to pose serious public health challenges to children[22]. Future vaccination programs implemented during public health emergencies should be carried out equitably to prevent outbreaks of previously controlled vaccine-preventable diseases. According to data published on July 18, 2023, by the World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), in 2022, 20.5 million children did not receive one or more vaccines delivered through routine immunization services, compared to 24.4 million children in 2021[23]. The vaccine against tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis (DTP) is used as the global marker for vaccination coverage in children[24]. Of the 20.5 million children who missed out on one or more doses of their DTP vaccines in 2022, 14.3 million did not receive a single dose, so-called zero-dose children[25].

The COVID-19 vaccination program began in Nigeria in March 2021, marking the largest vaccination program ever implemented in the country [26]. On March 2, 2021, Nigeria received its first shipment of four million Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine doses from the COVAX facility through a partnership between the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), WHO, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI) [27]. The COVID-19 vaccination program in Nigeria was controversial and debated. In addition to disinformation, misinformation, and anti-vaccine sentiments [28] there were numerous conspiracy theories on the COVID-19 virus, and concerns have been raised about the effectiveness and safety of the vaccine [29]. Lack of self-assurance in the vaccine, lack of trust in the government, limited knowledge and access to vaccines, inadequate infrastructure, and a weak cold chain system were some of the major factors contributing to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy[28]. The COVID-19 Mass Vaccination Program was managed by the National Primary Healthcare Development Agency. Together with the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention, they developed, implemented, and evaluated the National Deployment and Vaccination Plan for COVID-19 Vaccines. They also assisted in addressing misinformation and supported field efforts [30]

The Federal Government of Nigeria’s efforts to raise awareness regarding the availability of COVID-19 vaccinations during the first phase of the vaccination program were ineffective[26]. This hinders the understanding of the long-lasting benefits of the vaccine among Nigerians, particularly among those who could not access information about the vaccination rollout in their language [27]. Consequently, concerns regarding vaccines have increased [28]. There were also beliefs that the COVID-19 pandemic was a hoax and that it was merely an attempt by politicians to launder public funds [31]. Globally, 7.81 billion vaccine doses had been administered as of November 28, 2021 [32]. In Nigeria, approximately six million people received the first dose of the vaccine as of November 19, 2021, whereas only 3,369,628 people received the second dose [33]. This has left more than 200 million people unvaccinated, representing 97.15% of the country’s entire population of the country [1]. Considerable vaccine apathy and profound hesitancy remain as challenges for COVID-19 vaccination in Nigeria. The vaccination rate remains low in Nigeria, particularly in pregnant women [34]. The WHO report as of March 6, 2023, showed that Nigeria had established an aggregate of 266,641 confirmed cases of COVID-19, and as of March 7, 2023, the country had administered a total of 111,985,403 vaccine doses to its population [35]. The hesitancy of Nigerians to receive COVID-19 vaccination despite the urgent and compelling need for vaccination [36] raises significant questions about Nigerians’ attitudes towards vaccination and the factors that influence vaccine uptake. Investigating how Nigerian newspapers reported on the vaccination program is therefore important for understanding media framing and its potential impact on public attitudes towards vaccine uptake. Previous studies have shown that news media reports play a critical role in informing the public about vaccines and shaping behaviour and attitudes towards vaccine uptake [37]. Consequently, the media portrayals of vaccine safety and their potential impact on public confidence in vaccination programs are valid concerns for public health authorities. The influence of news media on public opinion and behaviour is multifaceted and intricate [38]. In addition, with the rise of online news media, particularly the Internet, the role of traditional sources of health information, such as newspapers, is changing [39]. However, studies have consistently shown that news media, including newspapers, remain among the most important sources of health information [40]. News media have the power to influence perceptions of the benefits and risks of health interventions [41]. Previous research has demonstrated the significant role of media coverage in shaping public opinion on vaccination programs [40]. This study investigated the portrayal of the COVID-19 vaccine in Nigerian newspapers, using the method adopted in similar scholarly work to analyse the coverage content, tone, and framing of vaccination risks and benefits [40].

Methods

Study design

This study employed quantitative content analysis to examine the portrayal of COVID-19 vaccination in Nigerian newspapers. The design was adapted from previously validated media content analytical approaches or methods used in vaccination-related studies. The objective was to systematically evaluate the themes, evidence presented, perceived benefits, risks, and tone of media coverage of COVID-19 vaccination in Nigeria.

Study area

This study focuses on newspaper publications with a national circulation across Nigeria. Nigeria has a diverse media landscape comprising digital print, print, and hybrid newspaper platforms (both print and digital). Major national newspapers such as Punch, Vanguard, Daily Trust, Premium Times, and Whistler were selected because of their national reach, readership, and consistent publication of health-related content. Although some Nigerian newspapers were published in local languages, these publications were excluded because COVID-19 vaccine topics were rarely covered in local-language media, making them unsuitable for systematic content analysis within the scope of this study.

Data sources

A comprehensive search was conducted to identify Nigerian newspaper articles on COVID-19 vaccination. Newspaper articles were retrieved through three major platforms and search engines: Google News, Google Search, and PressReader, all of which provide extensive access to Nigerian newspapers. The search covered the period from January 2020 to December 2024, and this allowed the study to capture articles published before the arrival of COVID-19 vaccines in Nigeria as well as coverage following the vaccine’s arrival on March 2, 2021[42].

To ensure the comprehensive retrieval of relevant publications, a set of predefined keywords and Boolean combinations were applied during the search process. These included: “COVID-19 vaccine Nigeria,” “COVID-19 vaccines,” “COVID-19,” “COVID-19 outbreak,” “Coronavirus in Nigeria,” “Coronavirus vaccine,” “intervention on Coronavirus,” “updates on Coronavirus vaccines,” “Coronavirus vaccines,” and “pandemic in Nigeria.” These search terms were used to capture a wide spectrum of articles that discussed vaccine development, distribution, scientific evidence, public health messaging, reported risks, and perceived benefits of COVID-19 vaccination in Nigeria [43].

Eligibility criteria

Newspaper articles were selected for inclusion based on predefined eligibility criteria that were designed to ensure the relevance, quality, and analytical value of the dataset. To be eligible, an article must have been published between January 2020 and December 2024 and must appear in an English-language Nigerian newspaper, whether in print or online formats, or both. Only articles that directly covered COVID-19 vaccination, including vaccine availability, distribution, safety, efficacy, public perception, risk communication, and broader health-policy implications, were included. Eligible articles also had to provide full-text access either through the newspaper’s website, Google archived versions, or the PressReader platform. Newspapers with a wide national circulation and readership, such as Punch, Vanguard, Daily Trust, Premium Times, and Whistler, were prioritized to ensure that the dataset reflected mainstream media coverage across Nigeria.

Articles were excluded if they did not discuss COVID-19 vaccines or if their content focused exclusively on unrelated COVID-19 issues, such as lockdown directives, travel restrictions, political commentary, or general pandemic updates without any connection to vaccination. Publications were also excluded if they were duplicates, syndicated copies of the same report, or if the accessible version contained only headlines or summaries without full article text. Nigerian-language newspapers were not included in the study because they contained very limited reports on COVID-19 vaccines, and their exclusion ensured that the dataset remained consistent in terms of content availability, language, and scope.

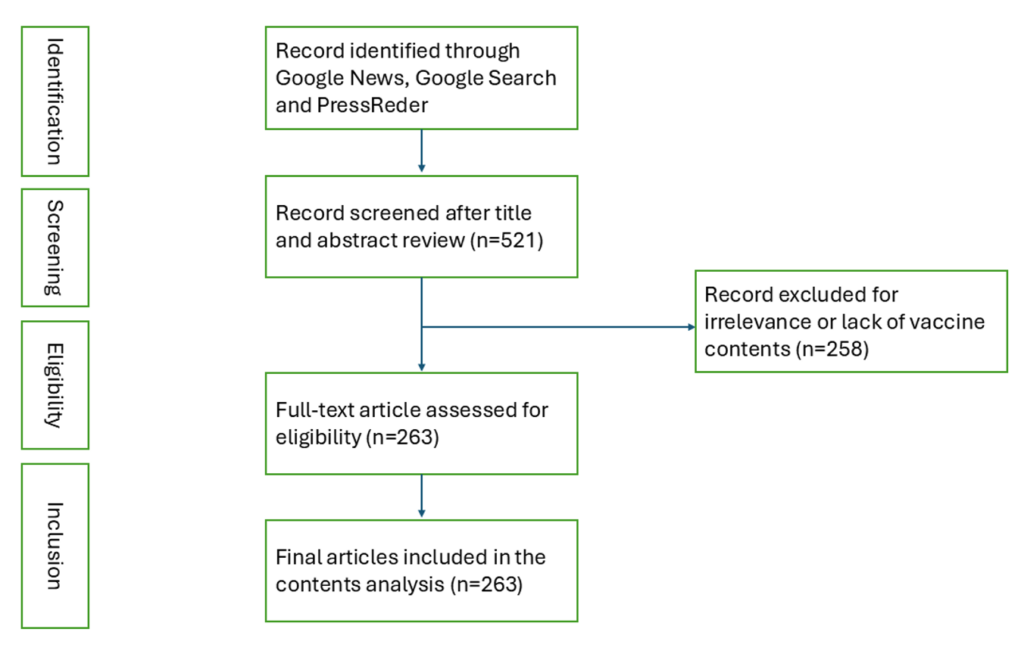

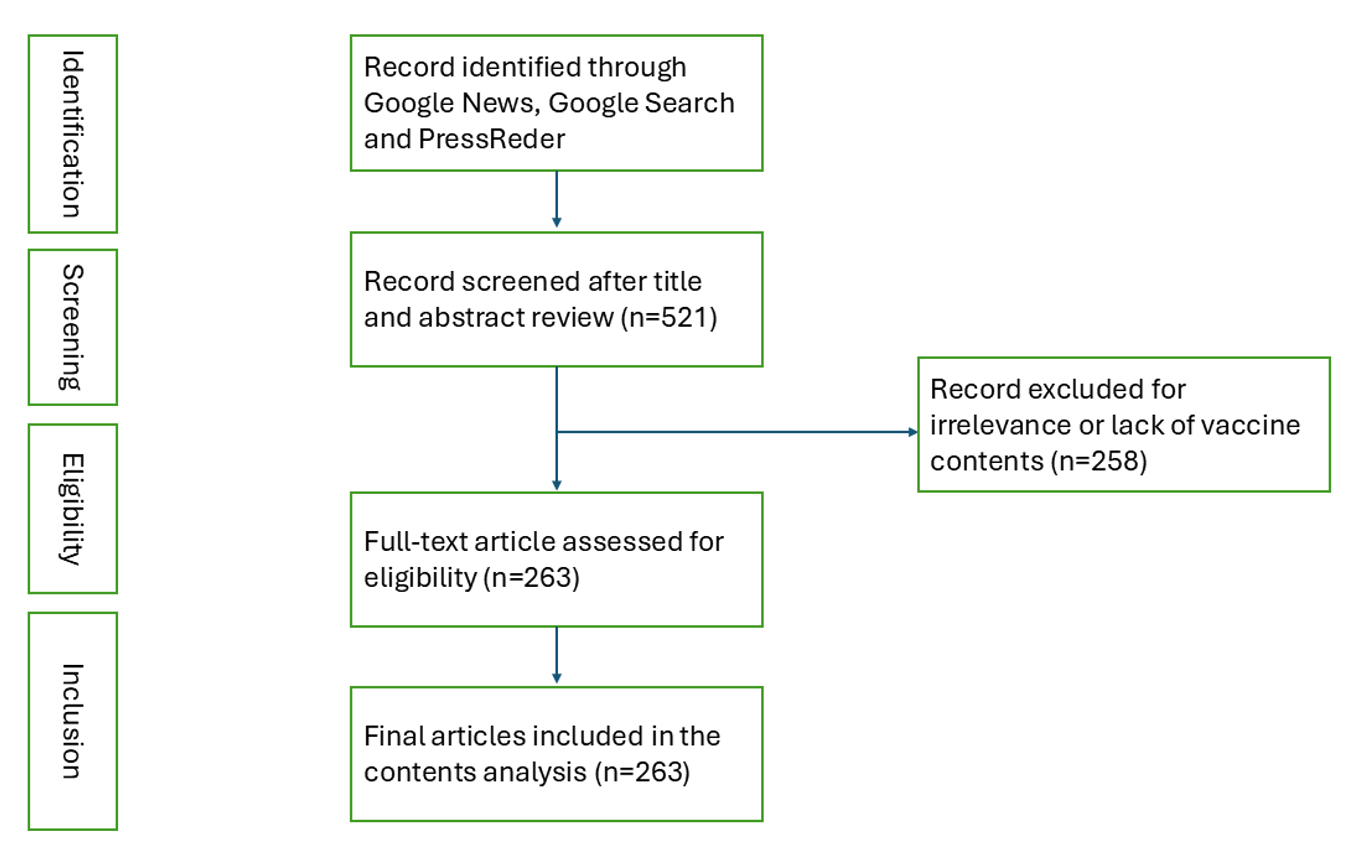

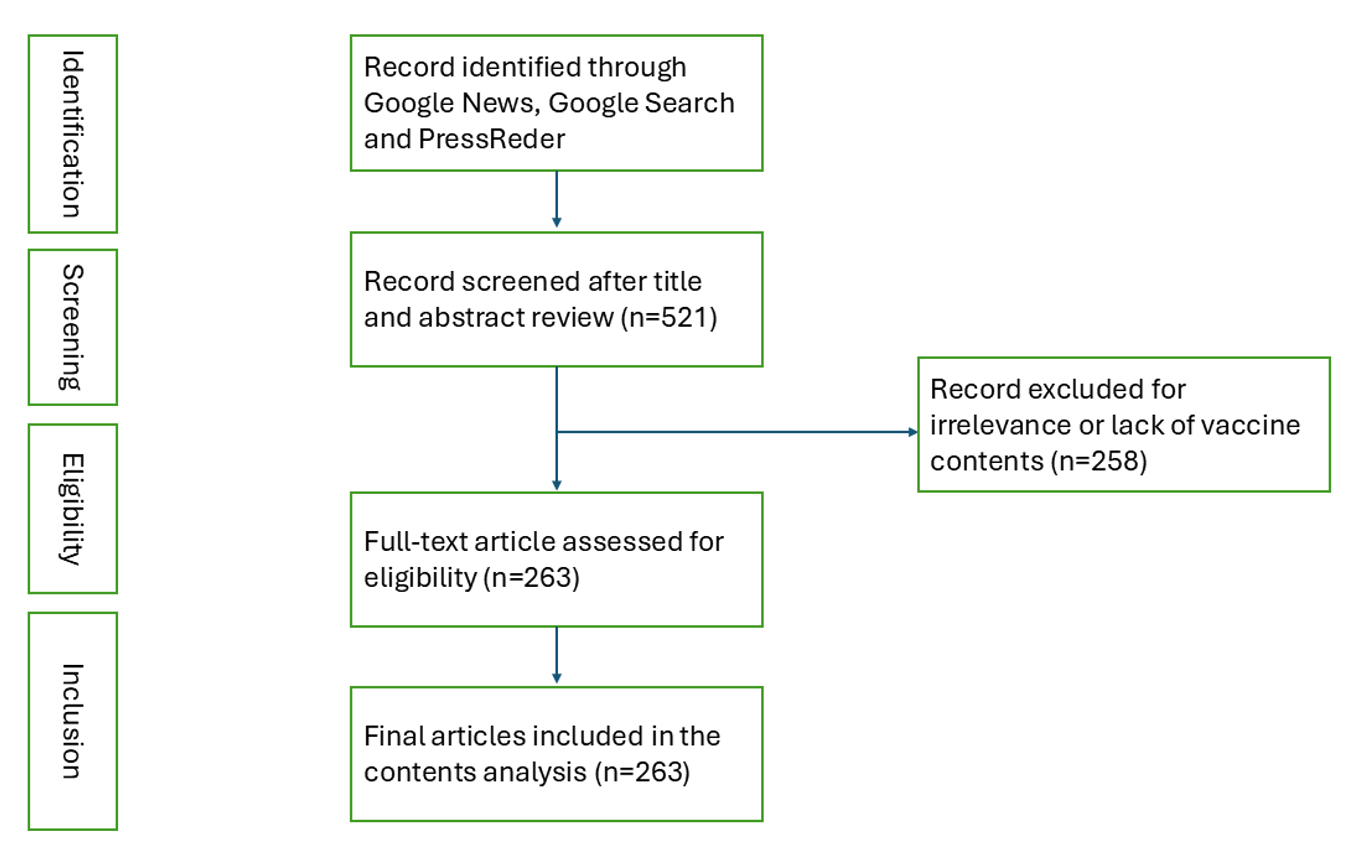

Data collection methods and tools

The data collection for this study followed a systematic two-stage screening and extraction process designed to ensure that only relevant and complete articles were included in the final dataset. In the first stage, an initial search yielded 521 articles from the selected databases. The titles and brief previews of these articles were reviewed to assess their relevance to the focus of the study. During this stage, any article that did not address COVID-19 vaccination was identified and marked for exclusion, which allowed for an efficient narrowing of the results before detailed examination.

In the second stage, all potentially relevant articles underwent comprehensive full-text screening. Full articles were accessed through various sources, including the official websites of the respective newspapers, PressReader platform, and Google’s cached versions when direct access was limited. Each article was carefully reviewed to determine whether it substantively discussed COVID-19 vaccines, including topics such as vaccine availability, safety, efficacy, risk perception, and public health. Articles that met these criteria were retained, whereas those lacking substantive vaccine-related content were excluded. At the end of this process, 263 articles met the eligibility requirements and constituted the final dataset used for analysis. The article selection process followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework to ensure a systematic and transparent screening procedure (Figure I).

Data extraction framework

Content analysis was conducted using a structured, three-section coding framework designed to systematically capture the key aspects of each newspaper article. The first section focused on sentiment and tone, categorizing articles as positive, negative, or neutral in their overall portrayal of the COVID-19 vaccination. This allowed the study to assess the media’s general attitude toward the vaccine and how it might influence public perception.

The second section addressed the thematic focus of these articles. The themes captured included public vaccine benefits, vaccine risks or hesitancy, communications from the government or health authorities, and the presence of scientific evidence or misinformation. This was done to identify the dominant narratives and the balance of risk versus benefit coverage in Nigerian newspapers. The third section examined content-specific variables, including whether the articles presented arguments for or against vaccination, whether they provided evidence regarding vaccine safety and efficacy, whether they discussed the risks associated with COVID-19 infection or vaccination, and which stakeholders were quoted or cited. Stakeholders included organizations such as the NCDC, NAFDAC, the WHO, public officials, scientists, and members of the public.

A coding guide was developed prior to the analysis to ensure consistency, reliability, and replicability of the coding across the dataset. This framework provides a comprehensive structure for systematically analyzing the 263 selected articles and enables both quantitative and qualitative interpretations of media coverage of COVID-19 vaccination in Nigeria.

Coding and data analysis

Data for this study were analyzed using descriptive quantitative techniques to systematically examine patterns in newspaper coverage of the COVID-19 vaccine. Each article was subjected to structured coding. The coding focused on identifying the sentiment expressed toward the vaccine, classified as positive, negative, or neutral. In addition, major thematic categories were documented to capture recurring issues emphasized in the reports. Articles were also assessed for their use of evidence-based reporting, including how they represented the risks and benefits of vaccination. Finally, all cited sources were categorized to determine the extent to which reports relied on scientific authorities, government officials, experts, or non-scientific voices.

The theme was assessed to determine whether it was descriptive, supported the use of the vaccine, opposed or questioned the vaccine, or presented both positions. The theme included both the author’s own attitude towards the vaccination program and the position presented in the news article. For example, an author might have written in a neutral or descriptive tone, but only opposing opinions were presented [40].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, percentages, and cross-tabulations, were used to summarise the coded data. These analyses provided insights into the distribution of major themes, patterns in how risks and benefits were framed, and tonal variations across newspapers. Additionally, statistical summaries highlighted the types of evidence and sources cited in articles.

Results

A total of 263 newspaper articles published between January 2020 and December 2023 were included in the analysis, drawn from The Guardian, Premium Times, Vanguard, Daily Trust, Punch, and ThisDay. As shown in Table 1, the articles were unevenly distributed across the newspapers, reflecting differences in the frequency of publication and editorial focus. Significant variations were observed in COVID-19 vaccine coverage across newspapers. The Guardian and Premium Times reported more positively on COVID-19 vaccination. Among articles published by Premium Times (n = 45/263), 55% (n = 25/45) presented the vaccine in a positive light, while 25% (n = 11/45) reflected negative sentiment and 20% (9/45) were neutral. Coverage in Premium Times focused largely on global vaccine efforts, scientific research, and policy debates. Similarly, The Guardian (n = 42/263) demonstrated a relatively positive tone, with 50% (21/42) of articles reporting positively on vaccination, 30% (13/42) expressing negative sentiment, and 20% (8/42) were neutral. The Guardian (n = 42/263) demonstrated evidence-based reporting, with recurring themes centered on immunity, public awareness, and misinformation. This finding may suggest an editorial effort to educate the public and counter false narratives about COVID-19 vaccination.

In contrast, Vanguard and Daily Trust exhibited predominantly negative sentiment toward COVID-19 vaccination. In Vanguard (n = 55/263), half of the articles (50%; 28/55) reflected skepticism or criticism, while 35% (19/55) were positive and 15% (8/55) neutral. The coverages of the articles frequently focused on vaccine hesitancy, misinformation, and access challenges, pointing to systemic issues and public distrust. Daily Trust (n = 33/263) recorded the highest proportion of negative coverage, with 55% (18/33) of articles expressing negative sentiment, compared with 30% (10/33) positive and 15% (5/33) neutral coverage. Themes such as religious concerns, public skepticism, and vaccine-related myths were prominent. This may reflect potential cultural and religious barriers to vaccine acceptance among its readerships.

Punch and ThisDay newspapers demonstrated more balanced coverage. In Punch (n = 50/263), 40% (20/50) of articles were positive, 45% (23/50) negative, and 15% (7/50) neutral, with strong emphasis on vaccine safety, side effects, and government response. This may be indicative of a watchdog approach to public health accountability. ThisDay (n = 38/263) similarly reflected a mixed stance, with 45% (17/38) positive coverage, 40% (15/38) negative coverage, and 15% (6/38) neutral coverage, focusing on the economic impact of the pandemic, global supply chains, and vaccine equity.

Across all newspapers, recurring themes such as misinformation, vaccine safety, hesitancy, and government response were consistently evident, highlighting ongoing challenges in public health communication. While some media outlets tended to foster public confidence in vaccination, others foregrounded skepticism and obstacles to acceptance, suggesting the influential role of the media in shaping public perceptions of vaccination.

To vaccinate or not to vaccinate

In terms of vaccine position, as indicated in the thematic analysis of the newspaper articles (Table 2), 60% (158/263) of the articles(n=263) were pro-vaccines only, clearly supporting the use of vaccines and encouraging their public use. A small number, 17.5% (46/263) of the articles expressed only anti-vaccine sentiments, either opposing vaccination or raising concerns that could discourage their use. A total of 59 articles (22.4%) presented both pro- and anti-vaccine perspectives, indicating concerted efforts by some newspapers to maintain a balance in reporting or reflect a diversified opinion. This distribution shows that, while most media coverage tends to favor vaccination, there is a notable presence of skepticism or mixed reactions in public discourse.

Evidence

Regarding the use of evidence to support claims regarding vaccine safety and efficacy, articles generally relied on credible sources (Table 2). 45% (119/263) of the 263 articles analysed cited scientific studies or investigations, while 40% (105/263) of the articles referred to expert opinions such as those from medical professionals or public health authorities. However, only 15% (39/263) provided no supporting evidence, suggesting that some coverage may have relied on speculation or unverified claims from the internet. This variation in the quality of evidence highlights the need for consistent fact-based reporting, particularly regarding matters as critical as vaccine safety.

Communication about risks and side effects

Regarding how risk was communicated, most articles, 47.5% (125/263), focused on the risks associated with COVID-19 complications, such as severe illness or death, emphasising the dangers of the virus (Table 2). 30% (79/263) highlighted vaccine side effects, which could raise concerns among readers if not properly contextualized. 12.5% (33/263) of the articles assessed addressed the risks of both COVID-19 complications and vaccination, thus offering a more balanced comparison. Meanwhile, only 10% (26/263) did not mention any risks, possibly concentrating instead on the logistical, policy, or economic aspects of the vaccine rollout. Overall, the findings suggest that Nigerian newspapers have generally played a supportive role in promoting vaccines and educating the public, often using scientific or expert-based evidence. Nevertheless, the presence of articles with anti-vaccine views, lack of evidence, or focus on vaccine risks shows the importance of responsible health journalism in shaping public perception and behavior during a global health emergency. Source attributions in COVID-19 news coverage (Table 3) show that scientists were the most frequently cited sources of COVID-19 vaccination news coverage, appearing in 40% (105/263) of the articles. Citations were generally associated with neutral or positive coverage. This suggests that scientific input was framed as credible, informative, and aligned with overall public health goals. Government agencies were cited in 30% (79/263) of articles. The coverage bias was mixed, indicating that media representation of government sources varied, sometimes supportive and other times critical. This may reflect the public’s divided perceptions of the government’s pandemic responses. Activists and NGOs were cited in 35% (92/263) of cases and were generally associated with mostly negative coverage. This could suggest that these groups were often quoted in contexts that highlighted high-handedness in pandemic handling, inequality, or human rights concerns, possibly placing them in opposition to official narratives. The World Health Organization (WHO) was cited in 25% (66/263) of the articles, but the tone of these mentions was mostly negative. This may reflect critical reporting of the WHO’s early pandemic response, delays, or controversies surrounding the evolving guidance during the crisis. Medical experts and healthcare professionals, while cited less frequently (20%, 53/263), were associated with mostly positive coverage, indicating that their voices were seen as trustworthy, particularly in guiding public behavior and explaining health measures. Public figures (e.g., politicians and celebrities) were cited in only 10% (26/263) of the articles, and coverage was mostly negative. Citizens were cited in 3% (8/263) of the articles and mostly associated with positive coverage. Although rarely included, their perspectives were often portrayed sympathetically, most likely when they shared personal experiences or expressed support for health measures.

Discussion

The role of the media had transcended from just informing to dealing with disinformation, misinformation and the fake news epidemic.[44] The news media play a crucial role in disseminating public health and policy information, ensuring accountability in decision-making processes, and influencing public perceptions through the number of news reports, content, and tone of news reports. The way the media presents public health crises, such as the novel COVID-19 pandemic, impacted how the public reacted to it,[45] including how they reacted to the action taken, such as vaccination to contain the spread of the disease.[46] While COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and uptake may be influenced by more than just media coverage,[47] the nature of media reports or coverage has a high tendency to influence public acceptance and rate of uptake. Our study supports the scholarly evidence that the Nigerian media contributed significantly to reducing the spread of the COVID-19 disease in the country [45]. During a public health emergency such as a disease outbreak, the source of information is of high importance and the information must be factual, reliable, accurate, credible and balanced [48]. Some researchers[49] had argued that “Government officials and technical experts were predominantly used by the newspapers as the source of their information”[50]. This aligned with our findings that showed that the majority of newspapers analyzed relied on experts (scientists) and government authorities as their credible sources of information. Also, our findings revealed a high level of trust in government authorities as reliable and credible sources of COVID-19 information, with experts identified as the most trusted sources. This finding is consistent with earlier research on newspaper coverage of COVID-19 vaccine side effects in Nigeria[50] and studies highlighting role of media and community engagement in COVID-19 vaccinations in Tanzania [51].

Nigeria has a large population of over 220 million people [52]. comprising more than 300 ethnic groups and languages [53]. Existing studies have shown that such cultural and linguistic diversity often translates into unequal access to information [54]. with disparities shaped by language, socioeconomic status, and educational level [51]. Consequently, tailoring inclusive communication strategies and ensuring that remote and underprivileged communities have access to credible information are critical during responses to public health emergencies, such as COVID-19 [55]. Previous studies have shown that risk communication disseminated through mass media significantly increases both risk perception and public compliance [56].

Consistent with these findings, most of the articles analysed in our study emphasised the risks associated with COVID-19, including severe illness and death, thereby highlighting the dangers posed by the virus. Such framing is likely to influence both risk perception and compliance with public health measures, including COVID-19 vaccination. While acknowledging that multiple factors shape public perceptions of available interventions during public health emergencies, Nigeria’s public health authorities, the Ministry of Health, and policymakers must develop effective strategies to promote vaccine acceptance during such crises [57]. As of February 2023, only 30.5% of Nigeria’s population had received full COVID-19 vaccination [47]. Although COVID-19 vaccine acceptance was relatively low in Nigeria, this study does not draw conclusions regarding the direct impact of Nigerian newspaper coverage on vaccination uptake in the country.

The findings of this study have important implications for public health policy. Given the media’s substantial influence on public perceptions and attitudes toward vaccination, [50] ensuring accurate, credible, and evidence-based reporting should be a central focus for health authorities [58]. Collaboration between policymakers and news organizations can enhance public education, counter misinformation, and tailor communication to Nigeria’s diverse cultural, linguistic, and religious contexts [59]. Media-specific strategies may also be necessary to address differences in coverage across outlets and build vaccine confidence effectively [60]. To strengthen the media’s role during public health emergencies, authorities should establish formal partnerships with media outlets [61], implement communication strategies that reach underserved populations, promote media literacy programs to help the public critically evaluate information, and engage trusted community leaders and influencers to amplify credible messages. Collectively, these measures can enhance public trust, improve compliance, reduce vaccine hesitancy, and strengthen preparedness for future health crises. Moreover, healthcare providers play a critical role in addressing vaccine hesitancy and promoting vaccine uptake [62]. Through patient education and counselling, they can directly respond to concerns about vaccine safety and effectiveness, providing clear and accurate information on the benefits of vaccination. In addition, healthcare professionals can work closely with public health authorities to disseminate reliable information and actively counter misinformation, thereby strengthening public trust and supporting broader vaccination efforts [38].

Limitation

Our study has several limitations. It was a sample of Nigerian newspaper articles, and our analysis did not include social media posts, blogs, or other graphics in newspaper articles that could impact vaccine acceptability. A key limitation of this study is that while we assessed whether news articles cited scientific studies or expert opinions, we did not evaluate the quality, credibility, or accuracy of the evidence referenced. During the COVID-19 pandemic, several scientific studies were later withdrawn, corrected, or discredited, and some expert opinions were found to be inaccurate or misleading [64]. Without examining the methodological soundness of the cited evidence, we cannot determine whether the articles relied on robust scientific information or inadvertently amplified misinformation. This limitation has implications for understanding how well newspaper journalists engage with scientific content and highlights the need for capacity-building to support accurate, evidence-informed health reporting.

Conclusion

This study showed that Nigerian newspapers varied significantly in their coverage of the COVID-19 vaccine program, with some newspapers promoting public trust in the vaccine, while others reinforced skepticism and promoted fear among the public regarding the risks associated with the vaccine and its safety. While publications like Premium Times and The Guardian tend towards evidence-based and supportive reporting, others such as Daily Trust and Vanguard highlighted public fears and hesitancy in the uptake of the vaccine. These differences reinforce the powerful influence of the media in shaping public perceptions and attitudes towards vaccination. To promote uptake of vaccines during public health emergencies, balanced and factual reporting is essential for effective communication, particularly for combating misinformation and promoting vaccine confidence [65]. Overall, our findings suggested that newspapers can play a supportive role in promoting vaccines and public health measures, but tailored, inclusive, and evidence-based communication strategies are essential to reach diverse populations, address skepticism, and enhance vaccine acceptance during public health emergencies. Policymakers and health authorities should leverage trusted media channels and expert voices to design effective communication campaigns that foster public trust and compliance.

What is already known about the topic

- Media shapes public perceptions and attitudes towards vaccination.

- Vaccination rate is low in Nigeria

- Nigeria faces significant challenges with vaccination of its population

What this study adds

- The findings demonstrate the importance of accurate, balanced, and factual media reporting in promoting public confidence in vaccination during public health emergency.

- The study provides evidence that can guide Nigerian health authorities and policymakers in designing effective communication strategies to counter misinformation and boost vaccine uptake during public health emergencies.

- It identifies key research gaps such as the impact of media coverage on vaccination rates, paving the way for more comprehensive future studies on vaccine communication in Nigeria.

- The study demonstrates that Nigerian newspapers played a major role in shaping public attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination, either promoting trust or amplifying skepticism and fear.

Authors´ contributions

Conceptualization & Supervision: Olalekan Isaac Olatunde<

Methodology & Investigation: Emmanuel Joel, Olushola Olalekan Elekofehinti

Formal Analysis & Writing – Original Draft: Olalekan Isaac Olatunde, Emmanuel Joel

Writing – Review & Editing: Olalekan Isaac Olatunde, Olushola Olalekan Elekofehinti

| Newspaper | Total Articles (n) | Positive Coverage (%) | Negative Coverage (%) | Neutral Coverage (%) | Common Themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Punch | 50 | 40 | 45 | 15 | Vaccine safety, Side effects, Government response |

| The Guardian | 42 | 50 | 30 | 20 | Immunity, Public awareness, Misinformation |

| Vanguard | 55 | 35 | 50 | 15 | Vaccine hesitancy, Misinformation, Access to vaccines |

| ThisDay | 38 | 45 | 40 | 15 | Economic impact, Global supply chains, Vaccine equity |

| Daily Trust | 33 | 30 | 55 | 15 | Religious concerns, Public skepticism, Myths about vaccines |

| Premium Times | 45 | 55 | 25 | 20 | Scientific research, Policy debates, Global vaccine efforts |

| Category | Description | Thematic Responses | Frequency (n = 263) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine Position | Whether the article opposes, supports, or presents both views on vaccination | Pro-vaccine, Anti-vaccine, Both perspectives | Pro: 158 (60%), Anti: 46 (17.5%), Both: 59 (22.5%) |

| Evidence on Safety & Efficacy | Whether the article provides evidence supporting or questioning vaccine safety and efficacy | Scientific study cited, Expert opinion, No evidence provided | Scientific Study: 119 (45%), Expert Opinion: 105 (40%), No Evidence: 39 (15%) |

| Risks Mentioned (COVID-19 vs. Vaccine) | Whether the article discusses risks of COVID-19, vaccine, or both | COVID-19 complications, Vaccine side effects, Both, None | COVID–19 Complications: 125 (47.5%), Vaccine Side Effects: 79 (30%), Both: 33 (12.5%), None: 26 (10%) |

| Sources Cited | Citation Rate (%) | Coverage Bias |

|---|---|---|

| Scientists | 40% | Mostly Neutral or Positive |

| Government Agencies | 30% | Mixed |

| Activists / NGOs | 35% | Mostly Negative |

| WHO | 25% | Mostly Negative |

| Medical Experts or Healthcare Professionals | 20% | Mostly Positive |

| Public Figures (Opinion Leaders, Public Personalities, Influencers, and Top Politicians) | 10% | Mostly Negative |

| Citizens | 3% | Mostly Positive |

References

- Oluwatosin Olu-Abiodun, Olumide Abiodun, Ngozi Okafor. COVID-19 vaccination in Nigeria: A rapid review of vaccine acceptance rate and the associated factors. PLOS ONE [Internet]. 2022 May 11 [cited 2026 Jan 7];17(5):e0267691. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0267691 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0267691

- World Health Organization. WHO Timeline – COVID-19 [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2020 Apr 27 [cited 2026 Jan 7]. [about 5 screens]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/27-04-2020-who-timeline—covid-19

- Chioma Dan-Nwafor, Chinwe Lucia Ochu, Kelly Elimian, John Oladejo, Elsie Ilori, Chukwuma Umeokonkwo, Laura Steinhardt, Ehimario Igumbor, John Wagai, Tochi Okwor, Olaolu Aderinola, Nwando Mba, Assad Hassan, Mahmood Dalhat, Kola Jinadu, Sikiru Badaru, Chinedu Arinze, Abubakar Jafiya, Yahya Disu, Fatima Saleh, Anwar Abubakar, Celestina Obiekea, Adesola Yinka-Ogunleye, Dhamari Naidoo, Geoffrey Namara, Saleh Muhammad, Oladipupo Ipadeola, Chinenye Ofoegbunam, Oladipo Ogunbode, Charles Akatobi, Matthias Alagi, Rimamdeyati Yashe, Emily Crawford, Oyeladun Okunromade, Everistus Aniaku, Sandra Mba, Emmanuel Agogo, Michael Olugbile, Chibuzo Eneh, Anthony Ahumibe, William Nwachukwu, Priscilla Ibekwe, Ope-Oluwa Adejoro, Winifred Ukponu, Adebola Olayinka, Ifeanyi Okudo, Olusola Aruna, Fatima Yusuf, Morenike Alex-Okoh, Temidayo Fawole, Akeem Alaka, Hassan Muntari, Sebastian Yennan, Rhoda Atteh, Muhammad Balogun, Ndadilnasiya Waziri, Abiodun Ogunniyi, Blessing Ebhodaghe, Virgile Lokossou, Mohammed Abudulaziz, Bimpe Adebiyi, Akin Abayomi, Ismail Abudus-Salam, Sunday Omilabu, Lukman Lawal, Mohammed Kawu, Basheer Muhammad, Aminu Tsanyawa, Festus Soyinka, Tomi Coker, Olaniran Alabi, Tony Joannis, Ibrahim Dalhatu, Mahesh Swaminathan, Babatunde Salako, Ibrahim Abubakar, Braka Fiona, Patrick Nguku, Sani H Aliyu, Chikwe Ihekweazu. Nigeria’s public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic: January to May 2020. Journal of Global Health [Internet]. 2020 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 7];10(2):020399. Available from: http://jogh.org/documents/issue202002/jogh-10-020399.pdf doi:10.7189/jogh.10.020399

- Henshaw Uchechi Okoroiwu, Christopher Ogar Ogar, Glory Mbe Egom Nja, Dennis Akongfe Abunimye, Regina Idu Ejemot-Nwadiaro. COVID-19 in Nigeria: account of epidemiological events, response, management, preventions and lessons learned. Germs [Internet]. 2021 Sept [cited 2026 Jan 7];11(3):391–402. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2248-2997/11/3/391 doi:10.18683/germs.2021.1276

- Oliver J Watson, Gregory Barnsley, Jaspreet Toor, Alexandra B Hogan, Peter Winskill, Azra C Ghani. Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: a mathematical modelling study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2022 Sept [cited 2026 Jan 7];22(9):1293–302. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(22)00320-6/fulltext doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00320-6

- Dinah V. Parums. Editorial: first full regulatory approval of a covid-19 vaccine, the bnt162b2 pfizer-biontech vaccine, and the real-world implications for public health policy. Med Sci Monit [Internet]. 2021 Sept 6 [cited 2026 Jan 7];27. Available from: https://www.medscimonit.com/abstract/index/idArt/934625 doi:10.12659/MSM.934625

- Shima Shakory, Azza Eissa, Tara Kiran, Andrew D. Pinto. Best practices for covid-19 mass vaccination clinics. Ann Fam Med [Internet]. 2022 Mar [cited 2026 Jan 7];20(2):149–56. Available from: http://www.annfammed.org/lookup/doi/10.1370/afm.2773 doi:10.1370/afm.2773

- Ulrich Kalinke, Dan H. Barouch, Ruben Rizzi, Eleni Lagkadinou, Özlem Türeci, Shanti Pather, Pieter Neels. Clinical development and approval of COVID-19 vaccines. Expert Review of Vaccines [Internet]. 2022 May 4 [cited 2026 Jan 7];21(5):609–19. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14760584.2022.2042257 doi:10.1080/14760584.2022.2042257

- Abu Baker Sheikh, Suman Pal, Nismat Javed, Rahul Shekhar. Covid-19 vaccination in developing nations: challenges and opportunities for innovation. Infectious Disease Reports [Internet]. 2021 May 14 [cited 2026 Jan 7];13(2):429–36. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2036-7449/13/2/41 doi:10.3390/idr13020041

- Y Katelyn Yoo, Akriti Mehta, Joshua Mak, David Bishai, Collins Chansa, Bryan Patenaude. COVAX and equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines. Bull World Health Organ [Internet]. 2022 May 1 [cited 2026 Jan 7];100(05):315–28. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9047429/pdf/BLT.21.287516.pdf doi:10.2471/BLT.21.287516

- Oghenowede Eyawo, Uchechukwu Chidiebere Ugoji, Shenyi Pan, Patrick Oyibo, Amtull Rehman, Mishel Mahboob, Olapeju Adefunke Esimai. Predictors of the willingness to accept a free COVID-19 vaccine among households in Nigeria. Vaccine [Internet]. 2024 Oct [cited 2026 Jan 7];42(23):126225. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0264410X24009071 doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2024.126225

- Mohammed Sadiq, Stephen Croucher, Debalina Dutta. Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy: a content analysis of nigerian youtube videos. Vaccines (Basel) [Internet]. 2023 June 2 [cited 2026 Jan 7];11(6):1057. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10305430/ doi:10.3390/vaccines11061057

- Emmanuel Ikechi Onah. Nigeria: a country profile. Journal of International Studies [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2026 Jan 7];10. Available from: http://e-journal.uum.edu.my/index.php/jis/article/view/7954

- E. Gayawan, E. D. Arogundade, S. B. Adebayo. Possible determinants and spatial patterns of anaemia among young children in Nigeria: a Bayesian semi-parametric modelling. International Health [Internet]. 2014 Mar 1 [cited 2026 Jan 7];6(1):35–45. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/inthealth/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/inthealth/iht034 doi:10.1093/inthealth/iht034

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Nigeria Population 2025 – United Nations Population Fund [Internet]. New York (NY): UNFPA. 2025 [cited 2026 Jan 7]. [about 3 screens]. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/data/world-population/NG

- Chiemezie S. Atama, Obinna J. Eze, Ugochukwu Simeon Asogwa. Population data and resource allocation in Nigeria: Evidences from the challenges of distributing COVID-19 palliatives. Social Sciences & Humanities Open [Internet]. 2024 Jan 1 [cited 2026 Jan 7];10:101186. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590291124003838 doi:10.1016/j.ssaho.2024.101186

- Oluwatobi Ojabello, Wasiu Alli. Economic analysis: Growth on paper, struggle on the ground: Nigeria’s economic paradox [Internet]. Lagos (Nigeria): BusinessDay Media; 2024 Sept 02 [cited 2026 Jan 7]. [about 12 screens]. Available from: https://businessday.ng/news/article/economic-analysis-growth-on-paper-struggle-on-the-ground-nigerias-economic-paradox/

- Majekodunmi Waheed Oladipo, Oduola Oladotun Kabir, Ambali Abiodun Kabiru. An Assessment of the Trends of Income Growth, Poverty, Inequality and Human Welfare in Africa: New Evidence from Selected Sub-Saharan African Countries. International Journal of Advanced Academic Research [Internet]. 2023 Jun 1 [cited 2026 Jan 7];9(6):411–35. Available from: https://www.ijaar.org/articles/v9n6/ijaar968.pdf

- World Bank. Nigeria Poverty and Equity Brief: October 2025 [Internet]. Washington (DC): World Bank Group; 2025 Oct 01 [cited 2026 Jan 7]. [about 2 screens]. Available from: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099253204222517873

- Vivianne Ihekweazu. Nigeria Health Watch. Shaping a Healthier Future for Nigeria in 2025 [Internet]. Abuja (Nigeria): Nigeria Health Watch; 2025 Jan 02 [cited 2026 Jan 7]. [about 9 screens]. Available from: https://articles.nigeriahealthwatch.com/shaping-a-healthier-future-for-nigeria-in-2025/

- WHO. Breaking barriers, building bridges: the collaborative effort to reach every child in Nigeria [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2024 Aug 13 [cited 2026 Jan 7]. [about 7 screens]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/breaking-barriers-building-bridges-collaborative-effort-nigeria

- Ibrahim Dadari, Alyssa Sharkey, Ismael Hoare, Ricardo Izurieta. Analysis of the impact of COVID-19 pandemic and response on routine childhood vaccination coverage and equity in Northern Nigeria: a mixed methods study. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2023 Oct [cited 2026 Jan 7];13(10):e076154. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-076154 doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2023-076154

- Health Professional Academy. WHO: global childhood vaccination begins recovery after pandemic [Internet]. Wooburn Green (England): Health Professional Academy; 2023 Jul 20 [cited 2026 Jan 7]. [about 2 screens]. Available from: https://www.healthprofessionalacademy.co.uk/news/who-global-childhood-vaccination-begins-recovery-after-pandemic

- UNICEF. Immunization [Internet].New York (NY): UNICEF; 2025 [cited 2026 Jan 7]. [about 12 screens]. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-health/immunization/

- UNICEF. Childhood immunization begins recovery after COVID-19 backslide [Internet]. New York (NY): UNICEF (Nigeria); 2023 Jul 18 [cited 2026 Jan 7]. [about 8 screens]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/press-releases/childhood-immunization-begins-recovery-after-covid-19-backslide

- Tolulope Joseph Ogunniyi, Basirat Oluwadamilola Rufai, Sunday Nguher Uketeh, Justice Kwadwo Turzin, Emmanuel Abiodun Oyinloye, Fortune Benjamin Effiong. Two years of COVID-19 vaccination in Nigeria: a review of the current situation of the pandemic: a literature review. Annals of Medicine & Surgery [Internet]. 2023 Nov [cited 2026 Jan 7];85(11):5528–32. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/10.1097/MS9.0000000000001310 doi:10.1097/MS9.0000000000001310

- Taiwo Oluwaseun Sokunbi, Abdmateen Temitope Oluyedun, Emmanuel Ayomide Adegboye, Glory Peace Oluwatomisin, Abdulmumin Damilola Ibrahim. COVID‐19 vaccination in Nigeria: Challenges and recommendations for future vaccination initiatives. Public Health Challenges [Internet]. 2023 Mar [cited 2026 Jan 7];2(1):e57. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/puh2.57 doi:10.1002/puh2.57

- Tasmiah Nuzhath, Samia Tasnim, Rahul Kumar Sanjwal, Nusrat Fahmida Trisha, Mariya Rahman, S M Farabi Mahmud, Arif Arman, Susmita Chakraborty, Md Mahbub Hossain. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy, misinformation and conspiracy theories on social media: A content analysis of Twitter data [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2026 Jan 7]. Available from: https://osf.io/vc9jb_v1 doi:10.31235/osf.io/vc9jb

- Orestis Papakyriakopoulos, Juan Carlos Medina Serrano, Simon Hegelich. The spread of COVID-19 conspiracy theories on social media and the effect of content moderation [Internet]. Cambridge (MA): Havard Kennedy School-Mis/information Review; 2020 Aug 18 [cited 2026 Jan 7];1(3). Available from: https://misinforeview.hks.harvard.edu/article/the-spread-of-covid-19-conspiracy-theories-on-social-media-and-the-effect-of-content-moderation/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC Supports Nigeria’s COVID-19 Response [Internet]. Georgia (ATL): CDC; 2023 Jan 26 [cited 2026 Jan 7]. [about 7 screens]. Available from: https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/global-health/impact/nigeria-experts-support-covid-19.html

- Chizoba Wonodi, Chisom Obi-Jeff, Funmilayo Adewumi, Somto Chloe Keluo-Udeke, Rachel Gur-Arie, Carleigh Krubiner, Elana Felice Jaffe, Bamiduro T, Ruth Karron, Ruth Faden. Conspiracy theories and misinformation about COVID-19 in Nigeria: Implications for vaccine demand generation communications. Vaccine [Internet]. 2022 Mar 18 [cited 2026 Jan 7];40(13):2114–21. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X22001268 doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.02.005

- Samrat Kumar Dey, Md. Mahbubur Rahman, Umme Raihan Siddiqi, Arpita Howlader, Md. Arifuzzaman Tushar, Atika Qazi. Global landscape of COVID-19 vaccination progress: insight from an exploratory data analysis. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics [Internet]. 2022 Jan 31 [cited 2026 Jan 7];18(1):2025009. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21645515.2021.2025009 doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.2025009

- Nma Bida Alhaji, Ismail Ayoade Odetokun, Mohammed Kabiru Lawan, Abdulrahman Musa Adeiza, Wesley Daniel Nafarnda, Mohammed Jibrin Salihu. Risk assessment and preventive health behaviours toward COVID-19 amongst bushmeat handlers in Nigerian wildlife markets: Drivers and One Health challenge. Acta Trop [Internet]. 2022 Nov [cited 2026 Jan 7];235:106621. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9329136/ doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2022.106621

- Ijeoma Victoria Ezeome, Fausta Chioma Emegoakor, Theophilus Ogochukwu Nwankwo, Chidinma Ifechi Onwuka. Covid-19 guidelines adherence and vaccine acceptability among pregnant women in niger foundation hospital enugu, south-eastern nigeria: a mixed method study. International Journal of Women’s Health and Reproduction Sciences [Internet]. 2024 Jan 6 [cited 2026 Jan 7];12(1):21–32. Available from: https://www.ijwhr.net/text.php?id=702 doi:10.15296/ijwhr.2023.8009

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Nigeria – COVID-19 Overview [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): Johns Hopkins University of Medicine; 2023 [cited 2026 Jan 7]. [about 3 screens]. Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/region/nigeria

- Lucia Y Ojewale, Ferdinand C Mukumbang. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Nigerians living with non-communicable diseases: a qualitative study. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2023 Feb [cited 2026 Jan 7];13(2):e065901. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-065901 doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2022-065901

- Almudena Recio-Román, Manuel Recio-Menéndez, María Victoria Román-González. Influence of media information sources on vaccine uptake: the full and inconsistent mediating role of vaccine hesitancy. Computation [Internet]. 2023 Oct 23 [cited 2026 Jan 7];11(10):208. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2079-3197/11/10/208 doi:10.3390/computation11100208

- Tania Bubela, Matthew C Nisbet, Rick Borchelt, Fern Brunger, Cristine Critchley, Edna Einsiedel, Gail Geller, Anil Gupta, Jürgen Hampel, Robyn Hyde-Lay, Eric W Jandciu, S Ashley Jones, Pam Kolopack, Summer Lane, Tim Lougheed, Brigitte Nerlich, Ubaka Ogbogu, Kathleen O’Riordan, Colin Ouellette, Mike Spear, Stephen Strauss, Thavaratnam T, Lisa Willemse, Timothy Caulfield. Science communication reconsidered. Nat Biotechnol [Internet]. 2009 June [cited 2026 Jan 7];27(6):514–8. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nbt0609-514 doi:10.1038/nbt0609-514

- Geoff Brumfiel. Science journalism: Supplanting the old media? Nature [Internet]. 2009 Mar 1 [cited 2026 Jan 7];458(7236):274–7. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/458274a doi:10.1038/458274a

- Christen M. Rachul, Nola M. Ries, Timothy Caulfield. Canadian newspaper coverage of the a/h1n1 vaccine program. Can J Public Health [Internet]. 2011 May [cited 2026 Jan 7];102(3):200–3. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF03404896 doi:10.1007/BF03404896

- Tanya R. Berry, Joan Wharf-Higgins, P.J. Naylor. Sars wars: an examination of the quantity and construction of health information in the news media. Health Communication [Internet]. 2007 Apr 10 [cited 2026 Jan 7];21(1):35–44. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10410230701283322 doi:10.1080/10410230701283322

- Toluwanimi Ojeniyi, Amenze Eguavoen, Fejiro Chinye-Nwoko. Moving the needle for COVID-19 vaccinations in Nigeria through leadership, accountability, and transparency. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2023 Sept 21 [cited 2026 Jan 7];11:1199481. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1199481/full doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1199481

- Oberiri Destiny Apuke, Bahiyah Omar. How do Nigerian newspapers report COVID-19 pandemic? The implication for awareness and prevention [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2026 Jan 7]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/her/article/35/5/471/5935539 doi:10.1093/her/cyaa031

- Marian Chinwe Odionye (PHD). The Role of the Mass Media and Public Relations in Influencing Public Uptake of COVID-19 Vaccination in Nigeria. Journal of Media Practice and Research [Internet]. 2021 Jan 01 [cited 2026 Jan 7];5(1):2021. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/377722135_The_Role_of_the_Mass_Media_and_Public_Relations_in_Influencing_Public_Uptake_of_COVID-19_Vaccination_in_Nigeria

- Sunday G. John. Impact of media messages on containment of Coronavirus pandemic in Nigeria. J Public Health Afr [Internet]. 2023 Feb 28 [cited 2026 Jan 7];14(2):7. Available from: https://publichealthinafrica.org/index.php/jphia/article/view/234 doi:10.4081/jphia.2023.2048

- Molalegn Mesesle. Awareness and attitude towards covid-19 vaccination and associated factors in Ethiopia: cross-sectional study. IDR [Internet]. 2021 June [cited 2026 Jan 7];Volume 14:2193–9. Available from: https://www.dovepress.com/awareness-and-attitude-towards-covid-19-vaccination-and-associated-fac-peer-reviewed-fulltext-article-IDR doi:10.2147/IDR.S316461

- Ojo TO, Ojo AO, Ojo OE, Akinwalere BO, Akinwumi AF. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake among Nigerians: evidence from a cross-sectional national survey. Arch Public Health [Internet]. 2023 May 26 [cited 2026 Jan 7];81(1):95. Available from: https://archpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13690-023-01107-1 doi:10.1186/s13690-023-01107-1

- Harsh Lata, Neil Jan Saad Duque, Eri Togami, Miglietta A, Devin Perkins, Aura Corpuz, Masaya Kato, Amarnath Babu, Tshewang Dorji, Tamano Matsui, Maria Almiron, Ka Yeung Cheng, Lauren E MacDonald, Jukka Tapani Pukkila, George Sie Williams, Roberta Andraghetti, Carmen Dolea, Abdirahman Mahamud, Oliver Morgan, Babatunde Olowokure, Ibrahima Socé Fall, Adedoyin Awofisayo-Okuyelu, Esther Hamblion. Disseminating information on acute public health events globally: experiences from the WHO’s Disease Outbreak News. BMJ Glob Health [Internet]. 2024 Feb [cited 2026 Jan 7];9(2):e012876. Available from: https://gh.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjgh-2023-012876 doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2023-012876

- Pietro Battiston, Ridhi Kashyap, Valentina Rotondi. Reliance on scientists and experts during an epidemic: Evidence from the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. SSM – Population Health [Internet]. 2021 Mar [cited 2026 Jan 7];13:100721. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S235282732030358X doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100721

- Kehinde Victor Soyemi, Olagoke A Ewedairo, Charles Oluwatemitope Olomofe. COVID-19 Vaccine: Newspaper Coverage of the side effects of the vaccine in Nigeria [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2026 Jan 7]. Available from: http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2021.10.02.21264454 doi:10.1101/2021.10.02.21264454

- Ambrose T. Kessy, Chima E. Onuekwe, William M. Mwengee, Haonga Tumaini. The role of media and community engagement in COVID-19 vaccinations in Tanzania. Journal of Public Health in Africa [Internet]. 2025 Apr 18 [cited 2026 Jan 7];16(3). Available from: https://publichealthinafrica.org/index.php/jphia/article/view/705 doi:10.4102/jphia.v16i3.705

- Yan Shao, Zhe Yang, Yongbing Yan, Yuan Yan, Feruza Israilova, Nawal Khan, Liu Chang. Navigating Nigeria’s path to sustainable energy: Challenges, opportunities, and global insight. Energy Strategy Reviews [Internet]. 2025 May [cited 2026 Jan 7];59:101707. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2211467X25000707 doi:10.1016/j.esr.2025.101707

- Samuel B.K., Deinibiteim M.H. Ethnic diversity and democratic governance in nigeria: a consociational perspective. African Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Research [Internet]. 2023 June 20 [cited 2026 Jan 7];6(3):71–82. Available from: https://abjournals.org/ajsshr/papers/volume-6/issue-3/ethnic-diversity-and-democratic-governance-in-nigeria-a-consociational-perspective/ doi:10.52589/AJSSHR-2H3F3PH3

- Human Rights Research Center (HRRC). Lost in Translation: Language Discrimination and the Human Right to Access [Internet]. Alexandria (VA): HRRC; 2025 Jun 20 [cited 2026 Jan 7]. [about 7 screens]. Available from: https://www.humanrightsresearch.org/post/lost-in-translation-language-discrimination-and-the-human-right-to-access

- Phrashiah Githinji, Alexandra L. MacMillan Uribe, Jacob Szeszulski, Chad D. Rethorst, Vi Luong, Laura J. Rolke, Miquela G. Smith, Rebecca A. Seguin-Fowler. Public health communication during the COVID-19 health crisis: sustainable pathways to improve health information access and reach among underserved communities. Humanit Soc Sci Commun [Internet]. 2024 Sept 15 [cited 2026 Jan 7];11(1):1218. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-024-03718-7 doi:10.1057/s41599-024-03718-7

- Wilberforce Cholo, Fletcher Njororai, Walter Ogutu Amulla, Caleb Kogutu Nyaranga. Risk communication and public health emergency responses during covid-19 pandemic in rural communities in kenya: a cross-sectional study. COVID [Internet]. 2025 May 20 [cited 2026 Jan 7];5(5):74. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2673-8112/5/5/74 doi:10.3390/covid5050074

- Ahmad Ibrahim Al-Mustapha, Ochulor Okechukwu, Ademola Olayinka, Oyeniyi Rasheed Muhammed, Muftau Oyewo, Samuel A. Owoicho, Ahmed Tijani Abubakar, Abdulsalam Olabisi, Simon Ereh, Oluwatosin Enoch Fakayode, Oluwaseun Adeolu Ogundijo, Nusirat Elelu, Victoria Olusola Adetunji. A national survey of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Nigeria. Vaccine [Internet]. 2022 Aug [cited 2026 Jan 7];40(33):4726–31. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0264410X22008180 doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.06.050

- Taylor A. Holroyd, Oladeji K. Oloko, Daniel A. Salmon, Saad B. Omer, Rupali J. Limaye. Communicating recommendations in public health emergencies: the role of public health authorities. Health Security [Internet]. 2020 Feb 1 [cited 2026 Jan 7];18(1):21–8. Available from: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/hs.2019.0073 doi:10.1089/hs.2019.0073

- Omotola Ogunbola, Lanre Amodu, Goshen David Miteu, Omolara Ajayi. Covid-19 infodemic: media literacy and perception of fake news among residents of Ikeja, Lagos state. Ann Med Surg (Lond) [Internet]. 2025 July 15 [cited 2026 Jan 7];87(9):5644–9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC12401298/ doi:10.1097/MS9.0000000000003530

- Matt Motta, Steven Sylvester, Timothy Callaghan, Kristin Lunz-Trujillo. Encouraging covid-19 vaccine uptake through effective health communication. Front Polit Sci [Internet]. 2021 Jan 28 [cited 2026 Jan 7];3:630133. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.630133/full doi:10.3389/fpos.2021.630133

- Abbigail J. Tumpey, David Daigle, Glen Nowak. Communicating During an Outbreak or Public Health Investigation: At a glance – Chapter 12 of The CDC Field Epidemiology Manual [Internet]. Georgia (ATL): CDC; 2024 Aug 08 [cited 2026 Jan 7]. [about 26 screens]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/field-epi-manual/php/chapters/communicating-investigation.html

- Vaccine hesitancy and health care providers: Using the preferred cognitive styles and decision- making model and empathy tool to make progress – PMC [Internet]. [cited 2026 Jan 7]. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9241108/ doi:10.1016/j.jvacx.2022.100174

- Winifred Ekezie, Beauty Igein, Jomon Varughese, Ayesha Butt, Blessing Onyinye Ukoha-Kalu, Ifunanya Ikhile, Genevieve Bosah. Vaccination communication strategies and uptake in africa: a systematic review. Vaccines [Internet]. 2024 Nov 27 [cited 2026 Jan 7];12(12):1333. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/12/12/1333 doi:10.3390/vaccines12121333

- Angelo Capodici, Aurelia Salussolia, Francesco Sanmarchi, Davide Gori, Davide Golinelli. Biased, wrong and counterfeited evidences published during the COVID-19 pandemic, a systematic review of retracted COVID-19 papers. Qual Quant [Internet]. 2023 Oct [cited 2026 Jan 7];57(5):4881–913. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11135-022-01587-3 doi:10.1007/s11135-022-01587-3