Research | Open Access | Volume 9 (1): Article 14 | Published: 22 Jan 2026

Factors associated with malaria in pregnancy in N'Zérékoré District, Republic of Guinea

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Tables

| Characteristics | Frequency (n=437) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | ||

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤18 | 112 | 25.63 |

| 19–22 | 130 | 29.75 |

| 23–27 | 88 | 20.14 |

| >27 | 107 | 24.49 |

| Marital status | ||

| Monogamy | 308 | 70.50 |

| Polygamy | 129 | 29.50 |

| Woman’s education | ||

| None | 201 | 46.00 |

| Primary | 114 | 26.10 |

| Secondary | 104 | 23.80 |

| Bachelor’s Degree and Above | 18 | 4.12 |

| Spouse’s education | ||

| None | 170 | 38.90 |

| Primary | 35 | 8.01 |

| Secondary | 154 | 35.20 |

| Bachelor’s Degree and Above | 78 | 17.80 |

| Occupation of the woman | ||

| Seamstress | 213 | 48.70 |

| Housekeeper | 134 | 30.70 |

| Student | 58 | 13.30 |

| Healthcare Professional | 16 | 3.66 |

| Hairdresser | 8 | 1.83 |

| Other | 8 | 1.83 |

| Woman’s income | ||

| No Income | 116 | 26.50 |

| <550000 GNF | 187 | 42.80 |

| 550000 GNF and Above | 134 | 30.70 |

| Socioeconomic well-being quintile | ||

| Poorest | 219 | 50.10 |

| Poor | 200 | 45.80 |

| Middle | 18 | 4.20 |

| Place of residence | ||

| Rural | 1 | 0.23 |

| Urban | 436 | 99.77 |

| Obstetric Characteristics | ||

| Gestational age | ||

| First Trimester | 122 | 27.90 |

| Second Trimester | 247 | 56.50 |

| Third Trimester | 68 | 15.60 |

| Gravida | ||

| <5 | 359 | 82.20 |

| ≥5 | 78 | 17.80 |

| Parity | ||

| Nulliparous | 150 | 34.30 |

| Multiparous (1–3) | 221 | 50.60 |

| Grande multiparous (≥4) | 66 | 15.10 |

| Environmental Characteristics | ||

| Stagnant water around neighborhood (Yes) | 20 | 4.58 |

| Stagnant water around neighborhood (No) | 417 | 95.40 |

| Behavioral Characteristics | ||

| Less than 4 prenatal visits | 429 | 98.20 |

| 4 or more prenatal visits | 8 | 1.83 |

Table 1: Sociodemographic, obstetric, behavioural, and environmental profile of participants at the Gonia Health Center, N’Zérékoré Health District in Guinea, 2023

| Characteristics | Malaria Status | Crude OR (95% CI) | aP-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | bP-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive n (%) | Negative n (%) | |||||

| Socioeconomic well-being quintile | ||||||

| Poorest | 75 (34.20) | 144 (65.80) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Poor | 43 (21.50) | 157 (78.50) | 0.52 (0.33–0.81) | 0.004 | 0.48 (0.29–0.79) | 0.004* |

| Middle | 5 (27.80) | 13 (72.20) | 0.73 (0.25–2.15) | 0.6 | 0.54 (0.15–1.74) | 0.3 |

| Source of information | ||||||

| Other (Friend, family, etc.) | 99 (26.30) | 278 (73.70) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Poster / Billboard | 24 (40.00) | 36 (60.00) | 1.87 (1.05–3.29) | 0.04 | 2.01 (1.03–3.91) | 0.04* |

| Gravida | ||||||

| ≥5 | 11 (14.10) | 67 (85.90) | 1 | 1 | ||

| <5 | 112 (31.20) | 247 (68.80) | 2.73 (1.44–5.66) | 0.002 | 3.42 (0.79–20.90) | 0.13 |

| Parity | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 55 (36.70) | 95 (63.30) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Multiparous (1–3) | 59 (26.70) | 162 (73.30) | 0.63 (0.40–0.99) | 0.04 | 0.58 (0.34–0.97) | 0.03* |

| Grand multiparous (≥4) | 9 (13.60) | 57 (86.40) | 0.28 (0.12–0.58) | 0.68 | 0.51 (0.08–3.72) | 0.5 |

| Gestational age | ||||||

| First trimester | 26 (21.30) | 96 (78.70) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Second trimester | 84 (34.00) | 163 (66.00) | 1.89 (1.15–3.19) | 0.01 | 3.00 (1.64–5.63) | <0.001* |

| Third trimester | 13 (19.10) | 55 (80.90) | 0.88 (0.40–1.83) | 0.73 | 2.41 (0.91–6.26) | 0.072 |

| Headaches | ||||||

| No | 47 (23.70) | 151 (76.30) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 76 (31.80) | 163 (68.20) | 1.50 (0.98–2.30) | 0.06 | 1.69 (1.03–2.81) | 0.04* |

| Means of transportation used | ||||||

| Motorcycle / Car | 98 (31.70) | 211 (68.30) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Walking | 25 (19.50) | 103 (80.50) | 0.53 (0.31–0.85) | 0.009 | 0.51 (0.28–0.89) | 0.02* |

*Notes: *Significant at p < 0.05; 1 = reference group; CI = Confidence Interval;

COR = Crude Odds Ratio; AOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio.

Table 2: Factors Associated with Malaria Infection in Pregnant Women at Gonia Health Center, N’Zérékoré Health District, Guinea, 2023

Figures

Keywords

- Malaria

- pregnant women

- risk factors

- Guinea

Mory Diakite1,2,3,&, Fatoumata Binetou Diong4,5 , Mohamed Khalis2,5, Saad Zbiri2,3, Bapaté Barry6, Mouhamadou Faly Ba4,5, Amadou Ibra Diallo4,5, Kenza Hassouni2,3, Najdi Adil7, Adama Faye4,5

1Prefectural Health Directorate of Siguiri, Siguiri, Guinea, 2International School of Public Health, Mohammed VI University of Sciences and Health, Casablanca, Morocco, 3Laboratory of Public Health and Health Management, Mohammed VI University of Sciences and Health, Casablanca, Morocco, 4Cheikh Anta Diop University of DAKAR, Dakar, Senegal, 5Institute of Health and Development, M’Bour, Senegal, 6ECLAIR Office, Conakry, Guinea, 7Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy of Tanger, Abdelmalek Essaadi University (UAE), Tanger, Morocco

&Corresponding author: Mory Diakité, Prefectural Health Directorate of Siguiri, Siguiri, Guinea. Email: mdiakite@um6ss.ma, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2310-004X

Received: 29 Oct 2025, Accepted: 20 Jan 2026, Published: 22 Jan 2026

Domain: Infectious Disease Epidemiology, Maternal Health

Keywords: Malaria, pregnant women, risk factors, Guinea

©Mory Diakité et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Mory Diakité et al. Factors associated with malaria in pregnancy in N’Zérékoré District, Republic of Guinea. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2026; 9(1):14. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00262

Abstract

Introduction: Malaria in pregnant women poses a significant public health challenge in Africa, with serious consequences for both the mother and the fetus, as well as the newborn. It is linked to a high rate of maternal and infant morbidity and mortality. The objective of this study was to identify factors associated with malaria in pregnant women.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional study conducted from March 1st to August 31st, 2023, involving all pregnant women at the Gonia Health Center in the health district of N’Zérékoré, Republic of Guinea. Data were collected using a questionnaire covering clinical, socioeconomic, and environmental information, along with the Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT). A comprehensive sampling approach was employed. Using R software version 4.2.2, a multivariate analysis was performed with binomial logistic regression, and a 5% alpha error rate was used to determine odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals.

Results: We included 437 women in the study. The malaria frequency among the pregnant women was 28%(95% CI: 23.97-32.62). The average age was 23.20 (±6.20 years), with the most represented age group being women aged 19 to 22 years (29.7%). Nearly half of the pregnant women, 50.1%, were in the poorest socioeconomic well-being quintile, and 46.0% had no formal education. Factors associated with the occurrence of malaria in pregnant women were multiparity (aOR=0.58, 95%CI: 0.34-0.97), the second trimester of pregnancy (aOR = 3, 95%CI:1.64-5.63]), poor socioeconomic well-being quintile (aOR = 0.48 95%CI:0.29-0.79), the use of posters or billboards as a source of information (aOR = 2.01, 95%CI:1.03-3.91), and walking to prenatal care appointments (aOR = 0.51, 95%CI:0.28-0.89).

Conclusion: The high prevalence of malaria among pregnant women in Gonia highlights factors such as socioeconomic status, sources of information, parity, gestational age, symptoms, the number of doses of antimalarial drugs, sleep, and travel habits. The high malaria prevalence among pregnant women underscores the need for comprehensive health education for healthcare professionals, with a focus on malaria prevention during prenatal consultations. Special attention is required for pregnant women with these risk factors to prevent and manage malaria infection effectively during pregnancy.

Introduction

Malaria infection during pregnancy represents a significant health challenge, posing substantial risks to the health of the mother, fetus, and newborn[1]. These risks include consequences such as an increased rate of miscarriage, intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) linked to elevated perinatal mortality [2], low birth weight (LBW), prematurity, as well as instances of stillbirth[3].

Efforts have been made in the fight against malaria; nevertheless, pregnant women and children remain a vulnerable group to malaria [4]. In 2019, in sub-Saharan Africa, approximately 35% of pregnant women, representing nearly 12 million individuals, were exposed to malaria infection during pregnancy. Each year, nearly 30 million pregnant women remain at risk of infection with Plasmodium falciparum [5,6] and most often, they experience negative consequences [4]. The severity of malaria in pregnant women varies depending on the intensity of malaria transmission and the level of acquired immunity in the geographical area [7].

In Guinea, malaria constitutes the primary cause of outpatient visits (34%), hospitalizations (31%), and deaths (14%) in both public and private healthcare facilities, across all age groups[8]. Between 2022 and 2023, the number of cases saw a reduction of 3% (decreasing from 317 to 307 per 1,000 at-risk population), while the number of deaths decreased by 4.1% (from 0.73 to 0.7 per 1,000 at-risk population) [9].

According to data from the Demographic and Health Survey with Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (DHS-MICS 2012) and the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey on Malaria (MICS-PALU 2016), parasitic prevalence has decreased. The region N’Zérékoré transitioned from a high transmission stratum at 59.2%[10] to a moderate transmission stratum with a significant reduction in prevalence to 30.2% [11].

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a three-pronged approach to reduce the incidence of malaria during pregnancy (MIP). This involves diagnosis, early treatment, and the use of long-lasting insecticidal bed nets (LLINs), as well as intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine [12], all these should be backed by client education.

Malarial infection during pregnancy remains a major public health concern in Guinea, impacting the health of the mother, fetus, and newborn, despite the efforts made by the Guinean Government in recent years to combat malaria. National malaria control objectives align with global and African initiatives to combat the disease, including the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the Global Malaria Action Plan (GMAP) of the Roll Back Malaria Partnership (RBM), the Abuja targets of the African Union, and the goals of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) [13].

In Guinea, few studies have been conducted on malaria in pregnant women[14–16]. However, their findings do not explore the risk factors of malaria in pregnant women, particularly the influential networks around them (the spouse, traditional advice, perception of the disease, and other women in the household). In this context, it is essential to investigate the factors that may contribute to the occurrence of malaria in pregnant women. Therefore, we undertook this study at the Gonia Health Center to identify factors associated with malaria in pregnant women and formulate appropriate preventive measures.

Methods

Study design and setting

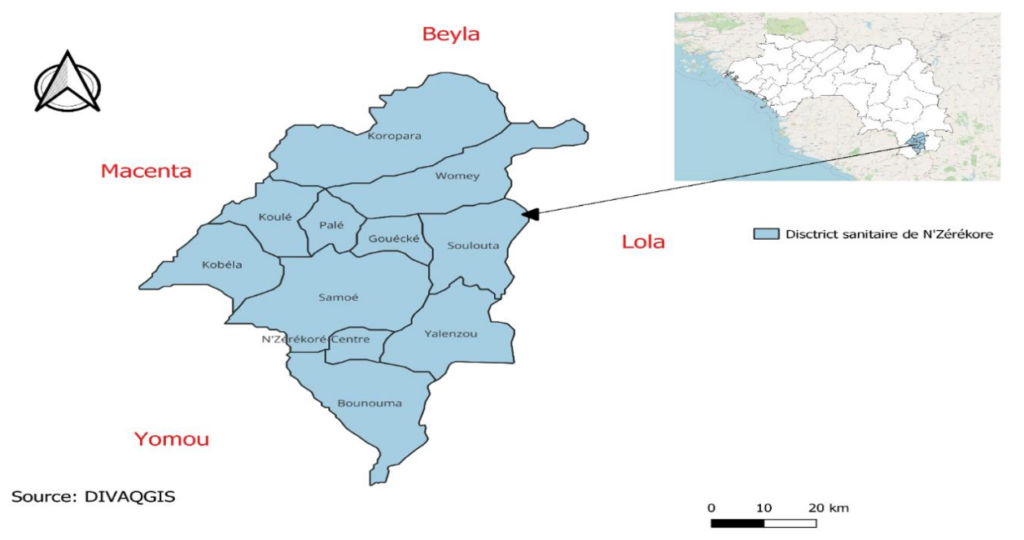

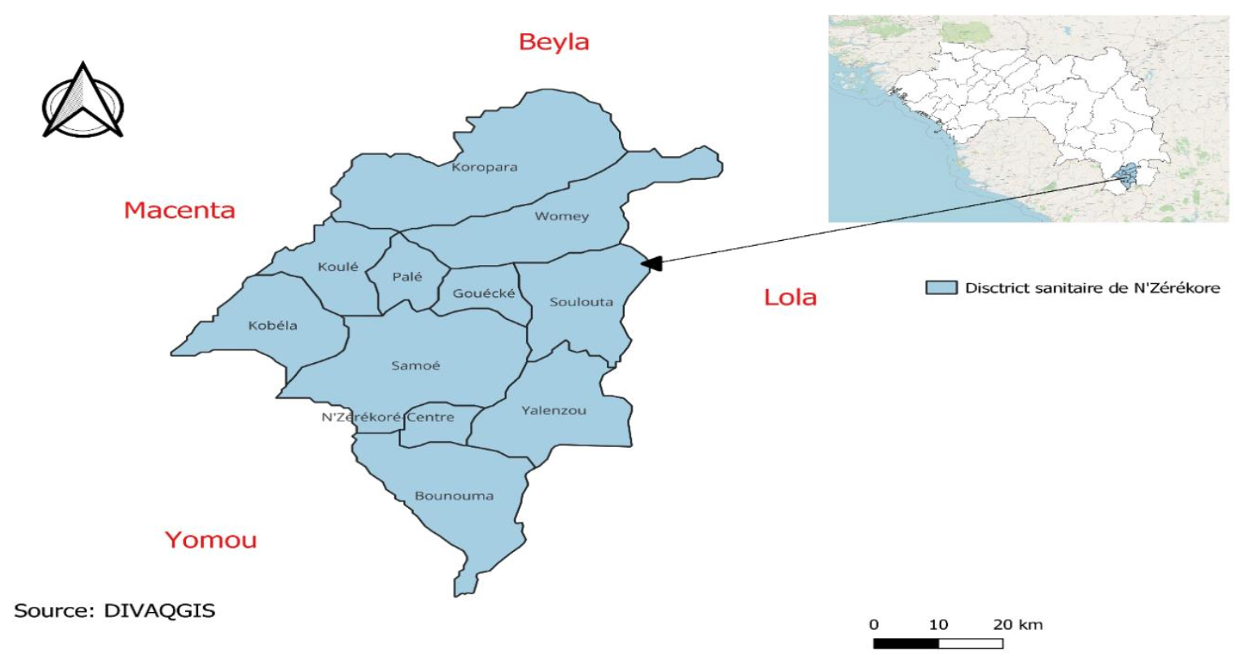

This was a cross-sectional study conducted over a six-month period, from March 1st to August 31st, 2023. The study was conducted at the Gonia Health Center, in the health district of N’Zérékoré (Figure 1). The Gonia Health Center serves a target population of 45,684 inhabitants,. There are two seasons: a rainy season from March to November and a dry season from December to February [17]. According to the third general population and housing census of 2014, the prefecture has a total population of 500,513 inhabitants, of which 254,440 are women. Women of reproductive age (15-49 years) represent 47.6% of the female population in the prefecture [18].

Study population

The study population consisted of pregnant women who attended the health centre for prenatal or curative consultations.

Inclusion criteria: All pregnant women attending prenatal or curative consultations at the health centre, who underwent a rapid diagnostic test (RDT) for malaria and agreed to participate in the study, were included.

Exclusion criteria: Pregnant women who had received antimalarial treatment in the two weeks prior were excluded.

Sampling

The study employed a comprehensive recruitment of all pregnant women during the study period, utilizing a rapid diagnostic test (RDT). Based on the number of pregnant women tested in the second half of 2022, it was anticipated to include approximately 300 pregnant women between March 1st and August 31st, 2023. This approach was chosen as the test is not administered systematically to all women but only to those showing presumed signs of malaria.

Data collection tool

An electronic questionnaire on the KoboToolbox platform served as the tool for data collection. The questionnaire comprised four main sections: socioeconomic and demographic factors of the mothers, individual characteristics, environmental features, and characteristics related to healthcare systems. It involved in-person interviews with the participants at the study site.

Study variables

The dependent variable of this study was the occurrence of malaria among pregnant women, considered as a binary variable defined by the presence or absence of malaria infection. A suspected malaria case was defined as any pregnant woman presenting one or more clinical signs suggestive of malaria, including fever, nausea, body aches, osteoarticular pain, headache, or any other compatible symptoms. A confirmed malaria case was any pregnant woman with a positive malaria rapid diagnostic test (RDT) result.

The socioeconomic variables mainly included household income and socioeconomic well-being. Household income was defined as the total monthly income earned by the pregnant woman and/or her spouse, derived from their professional activities. Monthly household income was categorized into two groups: income less than or equal to 550,000 Guinean francs (approximately USD 55), corresponding to an approximation of the guaranteed minimum interprofessional wage, and income strictly greater than this threshold.

Socioeconomic well-being was assessed using a composite questionnaire designed to calculate an individual socioeconomic score for each participant. This questionnaire was based on ten indicators related to household living conditions, including access to electricity, availability of flush toilets, ownership of a fixed or mobile phone, television, refrigerator, car, washing machine, as well as the presence of an indoor bathroom or shower and an indoor water tap. Based on these indicators, a global score was calculated for each pregnant woman and subsequently divided into quintiles of socioeconomic well-being, ranging from the poorest quintile (0–20%) to the richest quintile (81–100%), with intermediate categories defined as poorer (21–40%), middle (41–60%), and richer (61–80%).

Data collection procedure

All data collection was conducted by a qualified biologist who had received prior training on the study objectives, data collection procedures, ethical considerations, and the administration of the study questionnaire. Supervision was provided by a supervisor to ensure the quality and accuracy of the collected data.

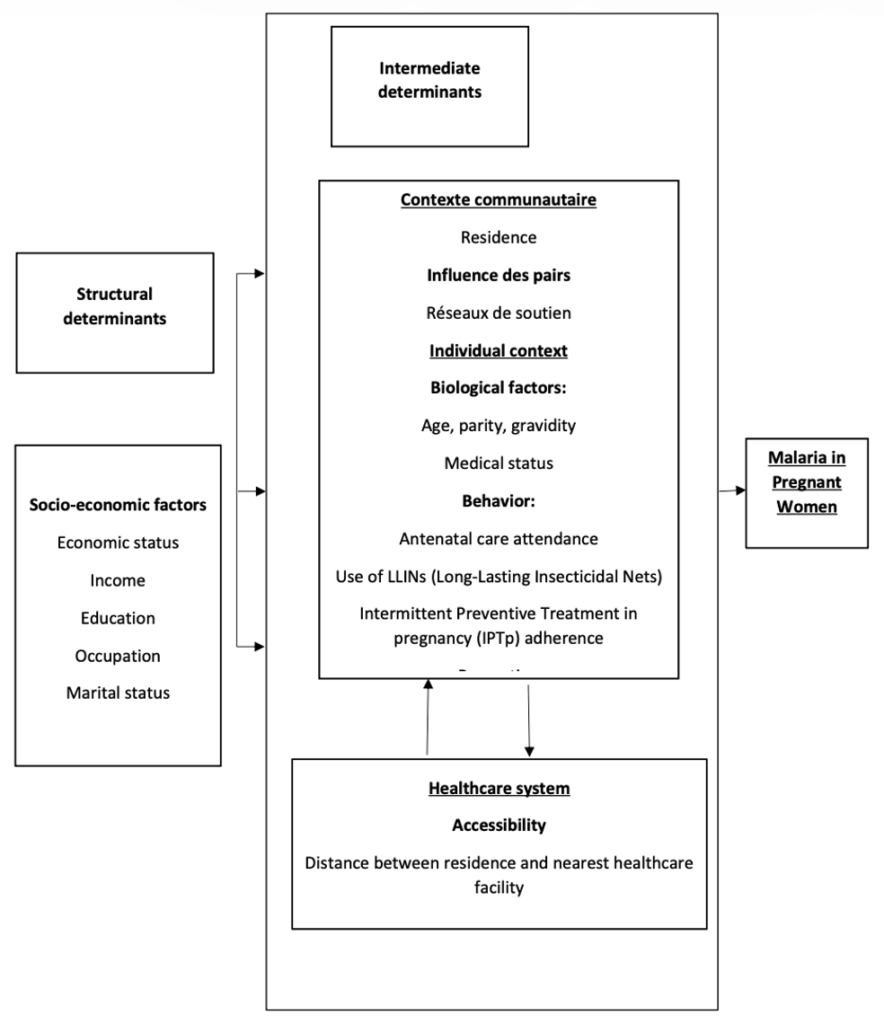

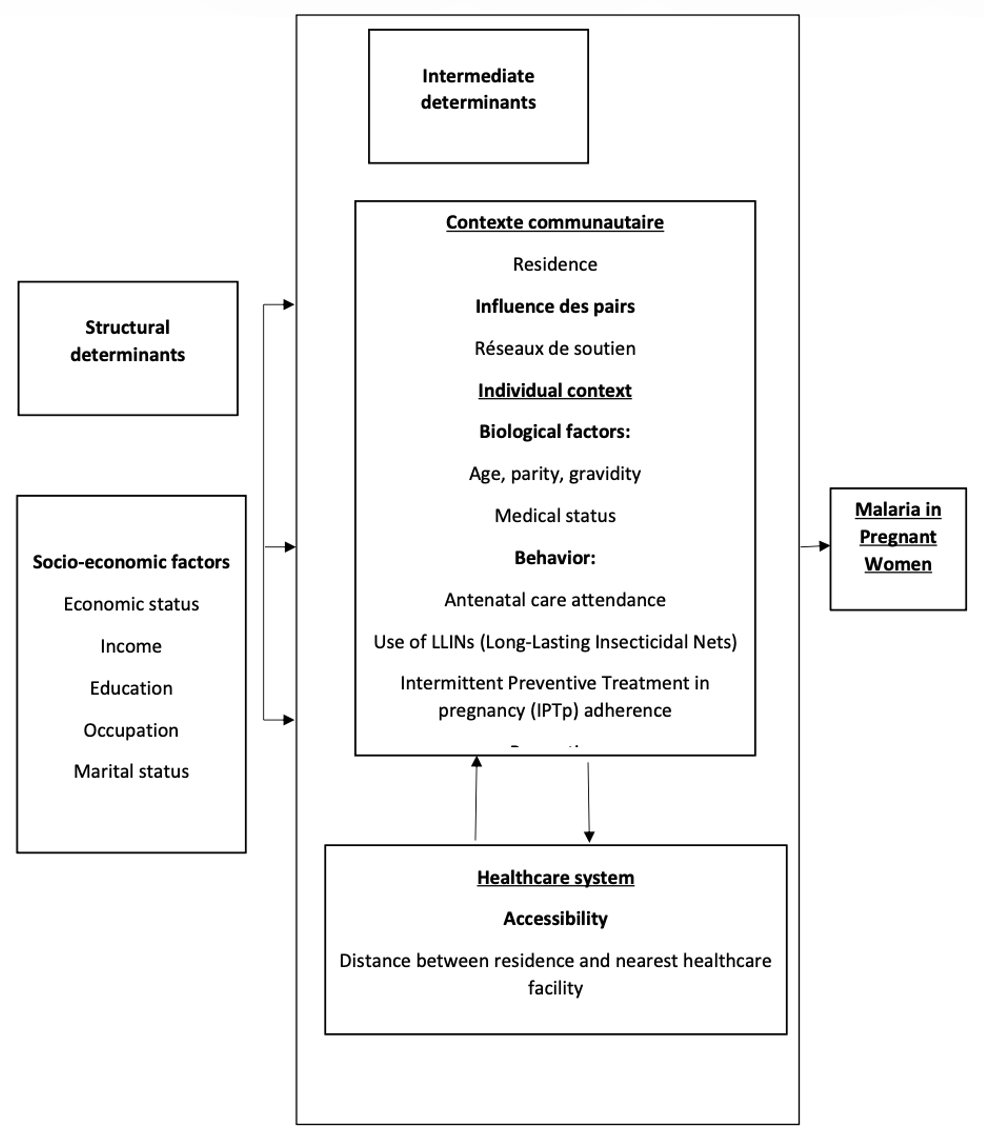

We utilised a modified conceptual framework based on the framework formulated by the Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH), adapted for maternal health by Hamal et al., and McCarthy & Maine’s framework on proximal and distal determinants of maternal deaths [19,20]. Within this framework, we were able to categorise independent variables into two main categories: structural determinants, encompassing socio-economic factors, and intermediate determinants, which could be grouped into individual factors (biological, health, and behavioral), environmental factors (community, family, and peer influence), and health system factors. The analysis of these different frameworks led to the development of the conceptual framework below (Figure 2).

Data entry, processing, and analysis

The real-time data entry into the Kobotoolbox platform was optimised to enhance operational efficiency while maintaining rigorous security controls. Once entered, the information is securely transmitted to the central server, where it is then stored in a database.

Statistical analysis was performed using R software version 4.2.2. Qualitative variables were described using absolute and relative frequencies, while quantitative variables were presented as means and standard deviations, median, and extremes. Bivariate analysis was employed to examine the association between the dependent variable (the variable to be explained) and the independent variables (explanatory variables). Pearson’s Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests were applied for qualitative variables, while the Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test was used for quantitative variables, depending on the conditions of application.

A logistic regression model was estimated; the primary outcome was the result of the rapid diagnostic test (RDT), which is a binary qualitative variable (positive or negative) during the study period. The variables that showed an association with malaria in the bivariate analysis, with a p-value less than 0.25, were introduced into a simple logistic multivariate regression model. From the initial model, we performed an automated stepwise mixed-method to obtain the final model, which allowed us to estimate the measure of association with adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and its 95% confidence interval.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Prefectural Health Directorate of N’Zérékoré and the Hospital-University Ethics Committee of Tanger (CEHUT) under the number AC42NV/2023. Before the start of data collection, the objectives, methodology, and implications of the study were presented to each participant in clear and accessible language. Participants were also given the opportunity to ask any questions to ensure full understanding of the study procedures prior to providing their consent.

In this study, the consent procedure did not involve any signatures, in accordance with the protocol approved by the ethics committee. Investigators were responsible for providing all relevant information in advance, including the study objectives, participation procedures, duration, potential benefits, possible risks, confidentiality principles, and the right to withdraw at any time without justification or consequence.

Following these explanations, consent was obtained orally. Once a participant clearly expressed her willingness to take part in the study, the investigator immediately assigned her a unique identification code, which allowed her inclusion in the study. No documents were signed, and no identifying information was collected, thereby ensuring complete confidentiality and anonymity.

This procedure, including the method used to document verbal consent, was previously submitted to and approved by the research ethics committee, which authorised verbal consent due to the non-invasive nature of the study and the operational context of the field setting. The choice of verbal consent was also justified by the limited literacy level of some participants. All data collected were treated with strict confidentiality, anonymised, and used solely for scientific purposes.

Results

In total, 437 pregnant women participated in this study, and the prevalence of malaria was 28.15% (95% CI: 23.97-32.62). The average age of the surveyed women was 23.2 years (± 5.60 years), with 29.75% belonging to the age group of 19 to 22 years and 24.49% in the group over 27 years. Women living in a monogamous relationship constituted 70.50%. The majority of women (46.00%) had no formal education, followed by those who had completed secondary education (26.10%). The majority of the spouses of the women (38.90%) had no formal education, 35.20% had completed secondary education Regarding their occupation, 48.70% of the participants were seamstresses, and less than half 42.80% had an income below the guaranteed interprofessional minimum wage (SMIG) of 550,000 GNF, equivalent to $64 (Table I). Nearly half of the pregnant women (50.10%) were in the most disadvantaged socio-economic well-being quintile, while only 4.20% were in the middle socio-economic well-being quintile. Almost all women (99.77%) resided in urban areas, and the majority had been living in their neighborhood for at least 6 months. Almost all surveyed women (99.50%) lived within 5 km of the nearest healthcare facility. The majority of the interviewed women (70.70%) used a motorcycle or a car to travel to the health center (Table I).

Most participants, 56.50%, were in the second trimester of their pregnancy at the time of inclusion. Among them, 82.20% had a gravidity less than 5, and 50.60% were multiparous. The majority of the included women, 70.50%, experienced headaches.The majority of participants primarily resided in environments without stagnant water (95.40%) and without waste around the neighborhood (92.90%). Garbage was regularly collected in 90.20% of cases (Table I). Regarding sources of information on malaria, the main ones used by pregnant women were their friends (52.90%), family members (66.80%), radio (59.30%), as well as health workers and community health workers (91.10%) (Table I).

The main reasons for consultation among women were physical asthenia (68.2%), headaches (70.5%), and fever (95.7%) (Table I), reflecting the most frequently observed symptoms in the study population. Women in the second trimester of pregnancy represented 56.50% of our sample. 82.20% of women had a gravidity of less than 5, and 50.60% were multiparous (1-3) (Table I). All pregnant women, 100% of the sample, received prenatal care. The majority of these women, 98.20%, had fewer than 4 prenatal visits. All pregnant women, representing 100% of the sample, were monitored at the health centre. Only 9.70% of pregnant women had taken sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, and only 2.29% had taken 3 doses or more. It is important to note that, among pregnant women, the first recourse for care in case of symptoms was a health facility, 99.10%. Regarding the use of traditional medicine, the majority of pregnant women, 80.30%, had resorted to it. Regarding the use of Long-Lasting Insecticide-Treated Nets (LLINs), more than 58% of pregnant women had access to them. Before pregnancy, only 41.90% had always slept under LLIN, while 42.10% used it since the beginning of pregnancy, and 42.30% had used it in the last two weeks (Table I).

The main reasons cited by pregnant women for using LLIN were to protect against malaria (99.50%) and to avoid mosquito bites (98.90%). Among pregnant women who did not use it, the main reasons for non-use were the habit of not using it (41.60%) and the lack of LLIN (28.60%) (Table I)

Factors associated with the occurrence of malaria in pregnant women

In this study, 437 women were tested for malaria, among whom 123 had a positive result using a rapid diagnostic test (RDT). After adjusting for other variables, women in the second socioeconomic well-being quintile were 0.48 times less likely to contract malaria compared to the poorest women (AOR=0.48; 95% CI: 0.29-0.79). Multiparous women had a lower risk of malaria, with an odds ratio of 0.58 (95% CI: 0.34-0.97) compared to nulliparous women. Pregnant women in the second trimester had a three times higher likelihood of developing malaria than those in the first trimester (AOR = 3.00; 95% CI: 1.64-5.63). Women experiencing headaches had a 1.69 times higher risk of malaria than those without headaches (AOR=1.69; 95% CI: 1.03-2.81) (Table 2). Women who indicated receiving information about malaria through the use of a poster or billboard had a twofold higher risk of malaria compared to those who did not use this information source (Friend, family member, healthcare providers, radio, etc.) (AOR=2.01; 95% CI: 1.03-3.91) (Table 2).

Furthermore, women in neighbourhoods where garbage was regularly collected had a 0.40 times lower risk of malaria than those in areas where garbage was not regularly collected (AOR=0.40; 95% CI: 0.19-0.88). In this study, an increase in the number of doses of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) during pregnancy was associated with a reduced risk of malaria. Women with a moderate number of doses (1 to 3 doses) had a reduced risk of 0.30 (95%CI: 0.15-0.57) compared to those who did not take any SP doses. Similarly, women with a satisfactory number of doses (3 doses or more) had a reduced risk of 0.03 (95% CI: 0.00-0.55) compared to those who did not take any SP doses (Table 2).

Women who never slept under a mosquito net before the current pregnancy had a twofold higher risk of contracting malaria than those who slept under a mosquito net every night (AOR=2.44; 95% CI: 1.37-4.42). Similarly, women who occasionally slept under a mosquito net also had a threefold higher risk of malaria (AOR=3.41; 95% CI: 1.15-6.43) compared to those who slept under a mosquito net every night before pregnancy. Women who used the mosquito net to avoid mosquito bites had a 0.03 times reduced risk of contracting malaria compared to those who did not use it for this purpose (AOR=0.03; 95% CI: 0.00-0.31). Women who walked to their prenatal appointments had 0.5 times less risk of contracting malaria (AOR=0.50; 95% CI: 0.27-0.89) (Table 2).

Discussion

This study was conducted to assess the prevalence of malaria infection among pregnant women attending the Gonia Health Center in the N’Zérékoré Health District in the southern part of the Republic of Guinea. Factors associated with this infection were also investigated. Identified determinants of malaria in pregnant women included the socio-economic well-being quintile, information source through a poster or billboard, parity, gestational age, presence of headaches, the number of doses of SP (sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine), regular garbage collection in the neighborhood, sleeping under LLINs (Long-Lasting Insecticidal Nets) before this pregnancy, sleeping under LLINs to avoid mosquito bites, as well as the mode of transportation used.In this study, the prevalence of malaria was 28.15%. This result was lower than that of a study conducted at the Issaka Gazobi Maternity (MIG) in Niamey[21], and lower than rates observed in Ghana [22]. Furthermore, it was higher than the prevalence in Cameroon [23]. This disparity could be attributed to various interventions carried out by Non-Governmental Organizations and donors in N’Zérékoré. These initiatives have strengthened existing malaria prevention measures, including the provision of SP, promotion of antenatal visits, and encouragement of LLINs utilisation [14].

Women belonging to the poor socioeconomic quintile showed a lower susceptibility to developing malaria compared to those in a wealthier class. Disadvantaged women often face challenges in accessing adequate healthcare, especially in settings where the number of qualified healthcare workers is insufficient. When poverty coexists with weak healthcare systems, pregnant women become a highly vulnerable population. Malaria is one of the major causes of morbidity for both mothers and children in such conditions [24].

The study revealed a significant relationship between malaria in pregnant women and information obtained through posters or billboards. This source of information appears to be a risk factor for the occurrence of malaria in women. Furthermore, the results show that the majority of pregnant women, 50.10%, belong to the poorest socioeconomic quintile, and 46% of them have no formal education, which could explain their difficulty in understanding messages conveyed by posters or billboards written in French. This lack of understanding may hinder the implementation of malaria prevention measures contained in awareness messages. However, it is important to note that these results should be interpreted with caution, as a more in-depth investigation would be necessary to fully assess the effect of this information source.

We also examined the means of transportation used by women to reach the health center to determine if there is an association with malaria. Interestingly, we observed that walking to prenatal consultations or health services could have a protective effect against malaria. Indeed, walking to access the health center may suggest greater geographical proximity between the women’s homes and health services. Additionally, regular physical activity, such as walking, may be associated with a more active lifestyle and better overall health, thereby strengthening the immune system and reducing susceptibility to infections, including malaria [25].

However, it is essential to note that other factors, such as socio-economic status, access to transportation, and environmental characteristics, may also influence this association. Therefore, additional studies are needed to confirm these observations and better understand the underlying mechanisms of this relationship.

In this study, we found that gestational age in the second trimester was a risk factor for the development of malaria in pregnant women. These results are consistent with a previous study by Fischer PR, which noted that pregnant women in the second and third trimesters were more likely to contract malaria [26]. There are several reasons to explain this association. Firstly, during pregnancy, women’s immune systems undergo changes, which can make pregnant women more vulnerable to infections, including malaria[27]. Additionally, as pregnancy progresses, there may be changes in the level of immunity and resistance to malaria, increasing the risk of infection[27]. It is important to consider gestational age when planning and implementing malaria prevention and control strategies for pregnant women. Preventive measures such as the regular use of insecticide-treated mosquito nets, intermittent preventive treatment, and regular malaria screening may be particularly important for pregnant women in the second trimester to reduce their risk of infection. Special attention should be given to malaria prevention and control in pregnant women, focusing on preventive measures tailored to each stage of pregnancy.

Not regularly collecting garbage in the neighborhood was a risk factor for malaria in pregnant women. Unattended garbage can serve as breeding and hiding sites for malaria-carrying mosquitoes. Stagnant water accumulated in the waste can serve as ideal breeding sites for mosquitoes, thus increasing their population and the chances of malaria transmission [28]. Furthermore, the presence of uncollected garbage can create an environment conducive to mosquito proliferation by providing shelter and food sources[29]. Mosquitoes can seek refuge in the waste and feed on organic matter, promoting their reproduction and survival. It is therefore crucial to implement effective waste management measures, including regular garbage collection, to reduce the presence of mosquito breeding sites and limit malaria transmission. This can be achieved through awareness and education programs promoting proper waste disposal practices, as well as community interventions such as regular cleaning of residential areas.

We found that regular use of the mosquito net had a protective effect against malaria in pregnant women. These results align with findings in the literature, notably in Niger[21] and Burkina Faso [30], which demonstrated that the risk of malaria infection was significantly higher in pregnant women not using the mosquito net. The mosquito net serves as an effective physical barrier against mosquito bites carrying malaria parasites [31]. It protects not only the pregnant woman but also the fetus by reducing exposure to malaria parasites[31]. It is important to emphasise that regular use of the mosquito net is recommended as a preventive measure for malaria during pregnancy, complementing intermittent preventive treatment and other vector control strategies [27]. Therefore, our results highlight the importance of promoting the regular use of mosquito nets among pregnant women to reduce the risk of malaria infection. Awareness and education interventions are necessary to inform pregnant women about the importance of mosquito net use and to overcome potential obstacles, such as availability issues and negative perceptions.

Strengths and Limitations

This study represents a significant advancement, exploring a wide range of factors influencing the occurrence of malaria during pregnancy. However, some limitations need to be considered. Firstly, this study is monocentric, limiting the generalisation of the results to other geographical contexts. A multicentric approach would have allowed obtaining more representative and applicable data for a broader population. Another limitation is that systematic screening for malaria in all pregnant women was not performed. This approach could have provided a more precise estimate of malaria frequency in the studied population, including asymptomatic cases that might have been underestimated in this study. One limitation of this study is that gestational age was not considered in the analysis of the number of SP doses, which may affect the interpretation of the results. Despite these limitations, the results obtained offer important insights that can inform the development of malaria prevention policies for pregnant women in Guinea.

Conclusion

The prevalence of malaria infection among pregnant women was relatively high at the Gonia health centre. Several factors were identified as significantly associated with malaria infection, such as the socio-economic well-being quintile, information source through posters or billboards, parity, gestational age, presence of headaches, the number of doses of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) taken, regular garbage collection in the neighborhood, sleeping under Long-Lasting Insecticidal Nets (LLINs) before this pregnancy, sleeping under LLINs to avoid mosquito bites as a reason for using LLINs, and the mode of transportation used to reach the health center, especially walking.

It is essential for healthcare professionals to provide comprehensive health education on malaria prevention methods during prenatal care. They should also pay special attention to pregnant women with identified risk factors to better prevent and manage malaria infection during pregnancy.

Furthermore, additional research is recommended to delve into the associations between information sources, physical activity, and the occurrence of malaria in pregnant women. A better understanding of these links could lead to more targeted and effective prevention strategies to reduce malaria incidence in this vulnerable population.

What is already known about the topic

- The risk of malaria infection is significantly higher among non-educated pregnant women, suggesting that education level influences the adoption of preventive measures.

- Pregnant women living in peripheral urban areas or surrounding rural villages are more likely to contract malaria, mainly due to limited access to healthcare services and preventive interventions.

- Not using insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs) remains a major risk factor for malaria infection during pregnancy.

- Intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP) is recognized as an effective protective factor against gestational malaria and its complications.

What this study adds

- Walking to the health center was associated with a reduced risk of malaria among pregnant women, suggesting that greater proximity and easier access to health services may promote early prevention and management.

- Women whose main source of information about malaria came from posters or billboards were more likely to contract the disease, indicating that such passive communication tools may be less effective than interactive awareness approaches.

- Irregular garbage collection in the neighborhood emerged as a significant risk factor for malaria among pregnant women, highlighting the importance of environmental and community-level determinants in malaria prevention efforts.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the women who generously participated in this study. Our thanks also go to the authorities of the N’Zérékoré Health District and the team at the Health Center for their favorable reception of our data collection request. We would like to extend special thanks to Mr. Koly LAMAH for his valuable contribution to data collection.

Authors´ contributions

Mory Diakite: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software Supervision, Validation, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Fatoumata Binetou Diong: Conceptualisation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Saad Zbiri: Validation, Writing – review & editing

Bapaté veve Barry: Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Mouhamadou Faly: Validation, Writing – review & editing,

Amadou Ibra Diallo: Validation Writing – review & editing

Kenza Hassouni: Validation, Writing – review & editing

Najdi Adil: Validation, Writing – review & editing

Mohamed Khalis: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Adama Faye: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing

| Characteristics | Frequency (n=437) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | ||

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤18 | 112 | 25.63 |

| 19–22 | 130 | 29.75 |

| 23–27 | 88 | 20.14 |

| >27 | 107 | 24.49 |

| Marital status | ||

| Monogamy | 308 | 70.50 |

| Polygamy | 129 | 29.50 |

| Woman’s education | ||

| None | 201 | 46.00 |

| Primary | 114 | 26.10 |

| Secondary | 104 | 23.80 |

| Bachelor’s Degree and Above | 18 | 4.12 |

| Spouse’s education | ||

| None | 170 | 38.90 |

| Primary | 35 | 8.01 |

| Secondary | 154 | 35.20 |

| Bachelor’s Degree and Above | 78 | 17.80 |

| Occupation of the woman | ||

| Seamstress | 213 | 48.70 |

| Housekeeper | 134 | 30.70 |

| Student | 58 | 13.30 |

| Healthcare Professional | 16 | 3.66 |

| Hairdresser | 8 | 1.83 |

| Other | 8 | 1.83 |

| Woman’s income | ||

| No Income | 116 | 26.50 |

| <550000 GNF | 187 | 42.80 |

| 550000 GNF and Above | 134 | 30.70 |

| Socioeconomic well-being quintile | ||

| Poorest | 219 | 50.10 |

| Poor | 200 | 45.80 |

| Middle | 18 | 4.20 |

| Place of residence | ||

| Rural | 1 | 0.23 |

| Urban | 436 | 99.77 |

| Obstetric Characteristics | ||

| Gestational age | ||

| First Trimester | 122 | 27.90 |

| Second Trimester | 247 | 56.50 |

| Third Trimester | 68 | 15.60 |

| Gravida | ||

| <5 | 359 | 82.20 |

| ≥5 | 78 | 17.80 |

| Parity | ||

| Nulliparous | 150 | 34.30 |

| Multiparous (1–3) | 221 | 50.60 |

| Grande multiparous (≥4) | 66 | 15.10 |

| Environmental Characteristics | ||

| Stagnant water around neighborhood (Yes) | 20 | 4.58 |

| Stagnant water around neighborhood (No) | 417 | 95.40 |

| Behavioral Characteristics | ||

| Less than 4 prenatal visits | 429 | 98.20 |

| 4 or more prenatal visits | 8 | 1.83 |

| Characteristics | Malaria Status | Crude OR (95% CI) | aP-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | bP-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive n (%) | Negative n (%) | |||||

| Socioeconomic well-being quintile | ||||||

| Poorest | 75 (34.20) | 144 (65.80) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Poor | 43 (21.50) | 157 (78.50) | 0.52 (0.33–0.81) | 0.004 | 0.48 (0.29–0.79) | 0.004* |

| Middle | 5 (27.80) | 13 (72.20) | 0.73 (0.25–2.15) | 0.6 | 0.54 (0.15–1.74) | 0.3 |

| Source of information | ||||||

| Other (Friend, family, etc.) | 99 (26.30) | 278 (73.70) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Poster / Billboard | 24 (40.00) | 36 (60.00) | 1.87 (1.05–3.29) | 0.04 | 2.01 (1.03–3.91) | 0.04* |

| Gravida | ||||||

| ≥5 | 11 (14.10) | 67 (85.90) | 1 | 1 | ||

| <5 | 112 (31.20) | 247 (68.80) | 2.73 (1.44–5.66) | 0.002 | 3.42 (0.79–20.90) | 0.13 |

| Parity | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 55 (36.70) | 95 (63.30) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Multiparous (1–3) | 59 (26.70) | 162 (73.30) | 0.63 (0.40–0.99) | 0.04 | 0.58 (0.34–0.97) | 0.03* |

| Grand multiparous (≥4) | 9 (13.60) | 57 (86.40) | 0.28 (0.12–0.58) | 0.68 | 0.51 (0.08–3.72) | 0.5 |

| Gestational age | ||||||

| First trimester | 26 (21.30) | 96 (78.70) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Second trimester | 84 (34.00) | 163 (66.00) | 1.89 (1.15–3.19) | 0.01 | 3.00 (1.64–5.63) | <0.001* |

| Third trimester | 13 (19.10) | 55 (80.90) | 0.88 (0.40–1.83) | 0.73 | 2.41 (0.91–6.26) | 0.072 |

| Headaches | ||||||

| No | 47 (23.70) | 151 (76.30) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 76 (31.80) | 163 (68.20) | 1.50 (0.98–2.30) | 0.06 | 1.69 (1.03–2.81) | 0.04* |

| Means of transportation used | ||||||

| Motorcycle / Car | 98 (31.70) | 211 (68.30) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Walking | 25 (19.50) | 103 (80.50) | 0.53 (0.31–0.85) | 0.009 | 0.51 (0.28–0.89) | 0.02* |

References

- World Health Organization. WHO policy brief for the implementation of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy using sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP) [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2013 Mar 31 [revised 2014 Jan; cited 2026 Jan 22]. 12 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HTM-GMP-2014.4 WHO Reference Number: WHO/HTM/GMP/2014.4.

- White NJ, Pukrittayakamee S, Hien TT, Faiz MA, Mokuolu OA, Dondorp AM. Malaria. Lancet [Internet]. 2013 Aug 15 [cited 2026 Jan 22];383(9918):723-35. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673613600240 doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60024-0. Erratum in: Lancet. 2013 Sep 13;383(9918):696. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61535-4.

- Kalinjuma AV, Darling AM, Mugusi FM, Abioye AI, Okumu FO, Aboud S, Masanja H, Hamer DH, Hertzmark E, Fawzi WW. Factors associated with sub-microscopic placental malaria and its association with adverse pregnancy outcomes among HIV-negative women in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: a cohort study. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2020 Oct 27 [cited 2026 Jan 22];20(1):796. Available from: https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-020-05521-6 doi:10.1186/s12879-020-05521-6.

- Diallo A, Touré AA, Doumbouya A, Magassouba AS, Traoré F, Cissé M, Barry I, Conté I, Cissé D, Cissé A, Camara G, Bérété AO, Camara AY, Conté NY, Beavogui AH. Factors associated with malaria preventive measures among pregnant women in Guinea. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol [Internet]. 2021 Jul 1 [cited 2026 Jan 22];2021:1-9. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/idog/2021/9914424/ doi:10.1155/2021/9914424.

- Desai M, ter Kuile FO, Nosten F, McGready R, Asamoa K, Brabin B, Newman RD. Epidemiology and burden of malaria in pregnancy. Lancet Infect Dis [Internet]. 2007 Jan 22 [cited 2026 Jan 22];7(2):93-104. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S147330990770021X doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70021-X.

- Gerome P. [Malaria: Global Situation 2020 (World Health Organization)] [Paludisme: Situation mondiale 2020 (Organisation mondiale de la Santé)] [Internet]. Bordeaux (France): Groupe d’Etudes en Préventologie; MesVaccins; 2020 Dec 12 [updated 2025 Nov 16; cited 2026 Jan 22]. Available from: https://www.mesvaccins.net/web/news/16794-paludisme-situation-mondiale-2020-organisation-mondiale-de-la-sante. French.

- Diarra SS, Konaté D, Diawara SI, Tall M, Diakité M, Doumbia S. Factors associated with intermittent preventive treatment of malaria during pregnancy in Mali. J Parasitol [Internet]. 2019 Apr 10 [cited 2026 Jan 22];105(2):299-302. Available from: https://journal-of-parasitology.kglmeridian.com/view/journals/para/105/2/article-p299.xml doi:10.1645/17-141.

- Ministère en charge des investissements et des parténariats publics privés. [Sector presentation: Health] [Présentation sectorielle: Santé] [Internet]. Conakry (Guinea): Ministère en charge des investissements et des parténariats publics privés; [cited 2026 Jan 22]. Available from: https://www.invest.gov.gn/page/sante?onglet=presentation. French.

- Severe Malaria Observatory. Guinea: Malaria facts [Internet]. Meyrin (Switzerland): Medicines for Malaria Venture; [cited 2026 Jan 22]. Available from: https://www.severemalaria.org/countries/guinea.

- Ministère du Plan et de la Coopération Internationale (MPCI), Institut National de la Statistique. [Demographic and Health Survey and Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (DHS-MICS 2012)] [Enquête Démographique et de Santé et à Indicateurs Multiples (EDS-MICS 2012)] [Internet]. Conakry (Guinea): MPCI; 2013 Nov [cited 2026 Jan 22]. 510 p. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR280/FR280.pdf. French.

- Ministère du Plan et de la Coopération Internationale (MPCI), Institut National de la Statistique (INS), Programme National de Lutte contre le Paludisme (PNLP). [2016 Parasite Prevalence Survey of Malaria and Anemia] [Enquête sur la Prévalence du Paludisme et de l’Anémie 2016] [Internet]. Conakry (Guinea): MPCI; 2017 Apr [cited 2026 Jan 22]. 52 p. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR332/FR332.pdf. French.

- World Health Organization. WHO guidelines for malaria [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2025 Aug 13 [cited 2026 Jan 22]. 478 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/guidelines-for-malaria.

- Ministère du Plan et du Développement Economique, Institut National de la Statistique. [2018 Demographic and Health Survey: Summary Report] [Enquête Démographique et de Santé 2018: Rapport de Synthèse] [Internet]. Conakry (Guinea): MCPI; 2019 [cited 2026 Jan 22]. 19 p. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SR262/SR262.pdf. French.

- Touré AA, Doumbouya A, Diallo A, Loua G, Cissé A, Sidibé S, Beavogui AH. Malaria-associated factors among pregnant women in Guinea. J Trop Med [Internet]. 2019 Nov 15 [cited 2026 Jan 22];2019:1-9. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jtm/2019/3925094/ doi:10.1155/2019/3925094.

- Flueckiger RM, Thierno DM, Colaço R, Guilavogui T, Bangoura L, Reithinger R, Fitch ER, Taton JL, Fofana A. Using short message service alerts to increase antenatal care and malaria prevention: findings from implementation research pilot in Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 2019 Oct 2 [cited 2026 Jan 22];101(4):806-8. Available from: https://www.ajtmh.org/view/journals/tpmd/101/4/article-p806.xml doi:10.4269/ajtmh.19-0202.

- Barry I, Toure AA, Sangho O, Beavogui AH, Cisse D, Diallo A, Magassouba AS, Sylla Y, Doumbia L, Cherif MS, Camara AY, Diawara F, Tounkara M, Delamou A, Doumbia S. Variations in the use of malaria preventive measures among pregnant women in Guinea: a secondary analysis of the 2012 and 2018 demographic and health surveys. Malar J [Internet]. 2022 Nov 1 [cited 2026 Jan 22];21(1):309. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-022-04322-3 doi:10.1186/s12936-022-04322-3.

- Guinée politique. [Introducing N’zerekore] [Présentation de N’zérékoré] [Internet]. Conakry (Guinea): Guinée Politique; 2020 [cited 2026 Jan 22]. Available from: https://guineepolitique.org/presentation-de-nzerekore/. French.

- Ministère du plan et la coopération internationale, Institut National De La Statistique, Bureau Central De Recensement. [General Population and Housing Census (RGPH3): Situation of women] [Recensement Général de la Population et de l’Habitation (RGPH3): Situation des femmes] [Internet]. Conakry (Guinea): MCPI; 2017 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 22]. 131 p. Available from: https://www.stat-guinee.org/images/Documents/Publications/INS/rapports_enquetes/RGPH3/RGPH3_situation_des_femmes.pdf. French.

- Hamal M, Dieleman M, De Brouwere V, De Cock Buning T. Social determinants of maternal health: a scoping review of factors influencing maternal mortality and maternal health service use in India. Public Health Rev [Internet]. 2020 Jun 2 [cited 2026 Jan 22];41(1):13. Available from: https://publichealthreviews.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40985-020-00125-6 doi:10.1186/s40985-020-00125-6.

- World Health Organization. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2010 Jul 13 [cited 2026 Jan 22]. 75 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241500852.

- Oumarou ZM, Lamine MM, Issaka T, Moumouni K, Alkassoum I, Maman D, Doutchi M, Alido S, Ibrahim ML. [Malaria infection in pregnant women in Niamey, Niger] [Infection palustre chez les femmes enceintes à Niamey, Niger]. Pan Afr Med J [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2026 Jan 22];37:365. Available from: https://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/37/365/full doi:10.11604/pamj.2020.37.365.20034. French.

- Dako-Gyeke M, Kofie HM. Factors influencing prevention and control of malaria among pregnant women resident in urban slums, southern Ghana. Afr J Reprod Health [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2026 Jan 22];19(1):44-53. Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajrh/article/view/115804.

- Fokam EB, Ngimuh L, Anchang-Kimbi JK, Wanji S. Assessment of the usage and effectiveness of intermittent preventive treatment and insecticide-treated nets on the indicators of malaria among pregnant women attending antenatal care in the Buea Health District, Cameroon. Malar J [Internet]. 2016 Mar 17 [cited 2026 Jan 22];15(1):172. Available from: http://www.malariajournal.com/content/15/1/172 doi:10.1186/s12936-016-1228-3.

- Worldwide Antimalarial Resistance Network. [Pregnant mothers matter, especially when they are at risk of contracting malaria] [Les mamans enceintes comptent surtout lorsqu’elles risquent de contracter le paludisme] [Internet]. Oxford (UK): IDDO; 2017 [cited 2026 Jan 22]. Available from: https://www.wwarn.org/fr/actualite/les-mamans-enceintes-comptent-surtout-lorsquelles-risquent-de-contracter-le-paludisme. French.

- Senn N, Del Rio Carral M, Gonzalez Holguera J, Gaille M, editors. [Health and the environment – Towards a comprehensive approach] [Santé et environnement – Vers une approche globale] [Internet]. 1st ed. RMS éditions / Médecine & Hygiène; 2022 Nov [cited 2026 Jan 22]. 502 p. Available from: https://www.revmed.ch/livres/sante-et-environnement doi:10.53738/REVMED.95022. French.

- Fischer PR. Malaria and newborns. J Trop Pediatr [Internet]. 2003 Jun 1 [cited 2026 Jan 22];49(3):132-5. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/tropej/article/49/3/132/1659449 doi:10.1093/tropej/49.3.132.

- World Health Organization. More pregnant women and children protected from malaria, but accelerated efforts and funding needed to reinvigorate global response, WHO report shows [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2019 Dec 4 [cited 2026 Jan 22]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/04-12-2019-more-pregnant-women-and-children-protected-from-malaria-but-accelerated-efforts-and-funding-needed-to-reinvigorate-global-response-who-report-shows.

- Rozendaal JA, World Health Organization, editors. [Vector control: methods for use by individuals and communities] [Lutte antivectorielle: méthodes à l’usage des particuliers et des collectivités] [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 1999 [cited 2026 Jan 22]. 449 p. Available from: https://iris.who.int/items/cd8487f5-7f81-4b52-8e4e-afa5ac3462ff. French.

- Diabaté M. [Household waste: impact on health and the environment in Commune I of the Bamako district: the case of Banconi] [Déchets ménagers: impact sur la santé et l’environnement dans la Commune I du district de Bamako: cas de Banconi] [thesis on the Internet]. Bamako (Mali): [publisher unknown]; 2010. [Chapter 3: Impact of household waste on health and the environment]; [cited 2026 Jan 22]; [about 40 screens]. Available from: https://www.memoireonline.com/09/10/3886/m_Dechets-menagers-impact-sur-la-sante-et-lenvironnement-en-commune-I-du-district-de-Bamako-ca2.html. French.

- Ouédraogo CMR, Nébié G, Sawadogo L, Rouamba G, Ouédraogo A, Lankoandé J. [Study of factors favoring the occurrence of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in pregnant women in the Bogodogo health district of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso] [Étude des facteurs favorisant la survenue du paludisme à Plasmodium falciparum chez la femme enceinte dans le district sanitaire de Bogodogo à Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) [Internet]. 2011 Apr 22 [cited 2026 Jan 22];40(6):529-34. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0368231511000871 doi:10.1016/j.jgyn.2011.03.005. French.

- Darriet F. [The fight against mosquitoes]. In: [Mosquitoes and Men] [Les moustiques et les hommes] [Internet]. Marseille (France): IRD Éditions; 2014 [cited 2026 Jan 22]. p. 69-108. Available from: https://books.openedition.org/irdeditions/9284 doi:10.4000/books.irdeditions.9284. French.