Research | Open Access | Volume 9 (1): Article 23 | Published: 04 Feb 2026

Knowledge, attitude, practice and entomological risk of dengue in Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 2024

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Tables

| Characteristics | n | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–24 | 37 | 9.20 |

| 25–34 | 96 | 23.88 |

| 35–44 | 92 | 22.89 |

| 45–54 | 88 | 21.89 |

| ≥55 | 89 | 22.14 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 163 | 40.55 |

| Female | 239 | 59.45 |

| Education level | ||

| None | 135 | 33.58 |

| Primary | 122 | 30.35 |

| Secondary or higher | 145 | 36.07 |

| Economic level* | ||

| Low | 106 | 26.37 |

| Medium | 224 | 55.72 |

| High | 72 | 17.91 |

| Occupation | ||

| Agriculture | 12 | 2.99 |

| Trade | 85 | 21.14 |

| Salaried / Self-employed | 130 | 32.34 |

| Unemployed / Homemaker | 175 | 43.53 |

* Economic level derived from a household asset-based index

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of participants, Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 2024 (N = 402)

| Attitudes | n | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Perceives dengue as a community health problem | 381 | 94.8 |

| Wishes to receive more information | 275 | 68.4 |

| Would seek care at a health facility | 378 | 94.0 |

| Would also consult a traditional healer | 134 | 33.3 |

Note: N = 402 represents the total number of participants interviewed.

Table 2: Attitudes of participants towards dengue, Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 2024 (N = 402)

| Practice | n | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Implements at least one preventive measure | 378 | 94.0 |

| Uses an insecticide-treated net | 294 | 73.1 |

| Practices environmental cleaning | 185 | 46.0 |

| Eliminates stagnant water | 143 | 35.6 |

| Uses mosquito coils | 123 | 30.6 |

| Uses repellents | 115 | 28.6 |

| Regularly cleans household surroundings | 96 | 23.9 |

| Wears protective covering clothing | 38 | 9.5 |

Note: N = 402 corresponds to the total number of participants surveyed.

Table 3: Preventive practices of participants regarding dengue, Bobo-Dioulasso, 2024 (N = 402)

| Parameter | n | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Households inspected | 384 | |

| Households with positive larval breeding sites | 236 | 61.5 |

| Mosquito species captured (n = 1,052) | ||

| Species | n | % |

| Culex quinquefasciatus | 705 | 67.0 |

| Aedes formosus | 226 | 21.5 |

| Aedes aegypti | 110 | 10.5 |

| Anopheles gambiae | 11 | 1.0 |

| Distribution of Aedes aegypti (n = 110) | ||

| Sex | n | % |

| Females | 82 | 73.6 |

| Males | 28 | 26.4 |

Note: The House Index represents the proportion of households with at least one positive breeding site.

Adult mosquito captures were conducted in a subsample of households, as described in the Methods section.

Table 4: Entomological parameters observed in households, Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 2024

| Characteristics | Yes n (%) | No n (%) | Crude PR | 95% CI | Adjusted PR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||

| 18–24 | 35 (94.59) | 2 (5.41) | Ref | ||

| 25–34 | 90 (94.79) | 5 (5.21) | 1.00 | 0.91–1.09 | 0.99 (0.92–1.07) |

| 35–44 | 87 (94.57) | 5 (5.43) | 0.99 | 0.91–1.09 | 0.99 (0.92–1.07) |

| 45–55 | 82 (93.18) | 6 (6.82) | 0.99 | 0.89–1.08 | 0.98 (0.90–1.07) |

| ≥55 | 82 (92.13) | 7 (7.87) | 0.97 | 0.88–1.07 | 0.96 (0.88–1.04) |

| Education level | |||||

| None | 125 (92.59) | 10 (7.41) | Ref | ||

| Primary | 110 (90.16) | 12 (9.84) | 0.90 | 0.90–1.05 | 0.95 (0.88–1.03) |

| Secondary / Higher | 142 (97.93) | 3 (2.07) | 1.05 | 1.00–1.11 | 1.02 (0.97–1.07) |

| Profession | |||||

| Unemployed / Housewife | 162 (92.57) | 13 (7.43) | Ref | ||

| Agriculture | 12 (100) | 0 | 1.08 | 1.10–1.15 | 1.12 (1.03–1.21) |

| Commerce | 77 (90.59) | 8 (9.41) | 0.97 | 0.90–1.06 | 0.96 (0.88–1.04) |

| Salaried / Independent | 126 (92.92) | 4 (3.08) | 1.04 | 0.99–1.10 | 1.04 (0.98–1.09) |

| History of dengue | |||||

| Yes | 53 (94.64) | 3 (5.36) | Ref | ||

| No | 323 (93.62) | 22 (6.38) | 0.98 | 0.92–1.05 | 0.98 (0.91–1.06) |

| Knowledge of transmission | |||||

| Good | 364 (95.29) | 18 (4.71) | Ref | ||

| Poor | 13 (65.00) | 7 (35.00) | 0.68* | 0.49–0.94 | 0.68* (0.49–0.93) |

Notes: PR = prevalence ratio; aPR = adjusted prevalence ratio. Robust Poisson models adjusted for age,

education level, occupation, history of dengue, and knowledge of the mode of transmission.

Reference categories: age 18–24 years; no formal education; Unemployed/Housewife; good knowledge.

* p < 0.05. Wald χ²(9) = 19.52; p = 0.021.

Table 5: Factors associated with care-seeking at a health facility among the participants

| Characteristics | Elimination of stagnant water | Crude PR | 95% CI | Adjusted PR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n (%) | No n (%) | ||||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 18–24 | 30 (81.08) | 7 (18.92) | Ref | – | Ref (–) |

| 25–34 | 56 (58.33) | 40 (41.67) | 0.71 | 0.57–0.90 | 0.72 (0.56–0.93) |

| 35–44 | 58 (63.04) | 34 (36.96) | 0.77 | 0.62–0.96* | 0.77 (0.60–0.99) |

| 45–55 | 32 (36.36) | 56 (63.64) | 0.78 | 0.62–0.97* | 0.77 (0.60–0.99) |

| ≥55 | 59 (66.29) | 30 (33.71) | 0.80 | 0.65–1.01 | 0.88 (0.63–1.02) |

| Education level | |||||

| None | 94 (69.63) | 41 (30.37) | Ref | ||

| Primary | 68 (63.93) | 44 (36.07) | 0.90 | 0.77–1.09 | 0.92 (0.77–1.10) |

| Secondary/Higher | 87 (60.00) | 58 (40.00) | 0.86 | 0.72–1.02 | 0.83 (0.68–1.01) |

| Profession | |||||

| Unemployed/Housewife | 123 (70.29) | 52 (29.71) | Ref | ||

| Agriculture | 7 (58.33) | 5 (41.67) | 0.82 | 0.50–1.35 | 0.82 (0.50–1.33) |

| Commerce | 50 (58.82) | 35 (41.18) | 1.00 | 0.60–1.68 | 0.86 (0.70–1.07) |

| Salaried/Independent | 79 (60.77) | 51 (39.23) | 1.04 | 0.63–1.71 | 0.93 (0.77–1.11) |

| History of dengue | |||||

| Yes | 37 (66.07) | 19 (33.93) | Ref | ||

| No | 211 (64.06) | 124 (35.94) | 0.96 | 0.79–1.18 | 0.99 (0.80–1.21) |

| Knowledge of transmission | |||||

| Good | 243 (63.61) | 139 (36.39) | Ref | ||

| Poor | 16 (80.00) | 4 (20.00) | 1.25 | 0.99–1.50 | 1.18 (0.94–1.48) |

Notes: PR = prevalence ratio; aPR = adjusted prevalence ratio. Robust Poisson models adjusted for age, education level, occupation, history of dengue, and knowledge of the mode of transmission. Reference categories: age 18–24 years; no formal education; Unemployed/Housewife; good knowledge. * p < 0.05. Wald χ²(9) = 13.65; p = 0.135.

Table 6. Factors associated with the elimination of stagnant water among the participants

Figures

Keywords

- Dengue

- Aedes

- Health knowledge

- Attitudes

- Practice

- Vector control

- Burkina Faso

Saïdou-Mady Bagaya1,&, Christian Manuel Zett1, Denis Yelbeogo2, Hamadou Seogo3, Roland Lamoussa Abga4, Bérenger Kabore2, Toussaint Compaore1, Pananou Daourou1, Dahourou Sou1, Kouka Ousséni Ouedraogo1, Wendlassida-Aboubacar Mahamane Nacro4, Evariste Pikbougoum1, Ousseni Barry1, Alphonse Traore1, Hamed Ouedraogo1

1Ministry of Health, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 2FETP Coordination (Frontline and Intermediate levels), Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 3Regional Technical Coordination – French-speaking West African countries, African Field Epidemiology Network (AFENET), 4Ministry of Agriculture, Animal and Fisheries Resources, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso

&Corresponding author: Bagaya Saïdou-Mady, Ministry of Health, Tenkodogo, Burkina Faso,

Email: bagayasm@yahoo.fr, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-2507-5244

Received: 18 Nov 2025, Accepted: 03 Feb 2026, Published: 04 Feb 2026

Domain: Infectious Disease Epidemiology

Keywords: Dengue, Aedes, health knowledge, attitudes, practice, vector control, Burkina Faso

©Bagaya Saïdou-Mady et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Bagaya Saïdou-Mady et al., Knowledge, attitude, practice and entomological risk of dengue in Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 2024. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2026; 9(01):23. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00290

Abstract

Introduction: Burkina Faso has experienced recurrent dengue outbreaks, including a major epidemic in 2023. This study assessed community knowledge, attitudes, preventive practices (KAP), and household-level entomological risk in Bobo-Dioulasso.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional study conducted in 2024 in the Do and Dafra health districts. Simple random sampling was performed using the household database from the 2022 long-lasting insecticidal net (LLIN) distribution campaign. KAP data were collected using a structured questionnaire. Entomological inspection of larval breeding sites was carried out in 384 households, and adult mosquito collection was conducted in 60 households. Data were analyzed using proportions and prevalence ratios (PR), estimated through robust Poisson regression.

Results: A total of 402 participants were included. Among them, 95.0% reported that dengue is transmitted by mosquitoes, and 91.3% knew mosquito breeding sites. Dengue was perceived as a community health problem by 94.8% of respondents. In case of suggestive symptoms, 94.0% reported they would seek care at a health facility, while 33.3% indicated they would also consult a traditional healer. Regarding preventive practices, 73.1% reported using an insecticide-treated net, 46.0% practiced environmental sanitation, and 35.6% eliminated stagnant water. Among the 384 households inspected, 61.5% had at least one positive larval breeding site. A total of 1,052 mosquitoes were captured, of which 10.5% were Aedes aegypti; among these, 73.6% were females. After adjustment, poor knowledge of the mode of transmission was associated with a lower likelihood of healthcare seeking (aPR = 0.68; 95% CI: 0.49–0.93).

Conclusion. This study shows high levels of knowledge and generally favourable attitudes toward dengue, but preventive practices remain limited, and household-level entomological risk is high. Strengthening health education, community mobilisation, environmental management, and entomological surveillance remain necessary in Bobo-Dioulasso.

Introduction

Dengue is a viral infection transmitted to humans by infected Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes [1]. It occurs predominantly in tropical and subtropical regions and is particularly common in urban and peri-urban environments [1]. Four main serotypes (DENV-1 to DENV-4) are recognised, and a fifth serotype (DENV-5) was identified in 2013 in Borneo [2]. Infection with one serotype confers long-term immunity against that serotype but only temporary protection against others, while secondary infection increases the risk of severe disease [1,2].

Since the 1980s, the global incidence of dengue has increased sharply, making it the most widespread arboviral infection worldwide, with an estimated 50 to 100 million cases annually, including 200,000 to 500,000 severe cases [3]. A global resurgence was reported in 2023 [4]. Africa was among the most affected regions, recording 171,991 cases and 753 deaths across 15 countries, with Burkina Faso being the most affected [1]. This increasing burden has been closely linked to the global expansion of Aedes mosquitoes and their adaptation to diverse ecological and climatic conditions, particularly in urban and peri-urban settings, driven by climate variability and environmental change [5,6]. These trends underscore the growing public health importance of dengue in Africa and highlight the need for locally generated evidence to guide context-specific prevention and control strategies.

In Burkina Faso, dengue transmission has been characterized by recurrent outbreaks in recent years. According to the WHO African Region, a major outbreak occurred in 2017, with more than 9,000 reported cases and 18 deaths [7]. Sustained viral circulation was subsequently documented by Africa CDC between 2021 and 2022, with a notable increase in reported incidence [8].

In 2023, surveillance systems reported a dengue outbreak with 154,867 suspected cases, including 70,433 probable cases and 709 deaths, corresponding to an estimated case fatality rate of approximately 0.4% [9]. During this outbreak, transmission particularly affected the Centre and Hauts-Bassins regions, where the health districts of Dafra and Do recorded the highest attack rates, estimated at 29.68 and 24.60 cases per 1,000 inhabitants, respectively [8,9]. In response, national health authorities implemented several interventions, including strengthened epidemiological surveillance, vector control measures, and social and behavioural change communication activities [10,11]. Despite these efforts, transmission persists due to structural determinants such as unplanned urbanization, high population density, widespread water storage practices, and environmental factors linked to climate variability and ecosystem change [12].

Effective dengue prevention requires a sound understanding of community knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Knowledge–Attitude–Practice (KAP) surveys provide timely insights into health behaviours, knowledge gaps, and determinants influencing the adoption of preventive measures [13]. Several studies conducted in endemic settings have shown that adequate knowledge is essential for sustaining effective preventive behaviours [14]. This study was therefore guided by the Knowledge–Attitude–Practice (KAP) framework, which assumes that knowledge shapes attitudes and ultimately influences behaviour. Previous dengue-related KAP studies conducted in endemic settings have frequently reported gaps between knowledge and the consistent adoption of preventive practices, particularly with regard to environmental management [13,14].

Nevertheless, KAP indicators alone may not fully capture actual transmission risk. Complementing behavioural assessment with entomological data is therefore essential to better characterise household-level dengue risk [15,16]. Moreover, increasing insecticide resistance among mosquito populations represents a growing challenge for vector control, reinforcing the need for continuous entomological surveillance and locally relevant evidence [15,16]. Yet, in Bobo-Dioulasso, the second largest city in Burkina Faso and the epicenter of the 2023 outbreak, evidence on community knowledge, attitudes, practices, and household-level entomological risk remains limited in the current epidemiological context. This study, therefore, sought to address this gap by assessing community knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding dengue prevention and evaluating household-level entomological risk in Bobo-Dioulasso in 2024.

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted in the commune of Bobo-Dioulasso, located in Houet Province within the Hauts-Bassins health region in western Burkina Faso [17,18]. It is the country’s second-largest urban area after Ouagadougou. The commune comprises thirty-three (33) urban sectors distributed across seven (7) administrative districts. The climate is Sudanian tropical, characterized by a rainy season from May to October and a dry season from November to April. Annual temperatures range from 25°C to 33°C, providing favourable conditions for the proliferation of arbovirus-transmitting mosquitoes.

The study focused on the health districts of Do and Dafra, which were previously identified as high-endemicity areas for dengue during recent outbreaks. The local health system is organised in a pyramidal structure. The first level includes Health and Social Promotion Centers (CSPS) and Medical Centers (CM), which provide primary healthcare services. The second level consists of District Hospitals (HD) or Medical Centers with Surgical Units (CMA), which manage referred cases and provide technical supervision to peripheral health facilities [17].

Study design and period

A cross-sectional study design was used, as it allowed a timely assessment of community knowledge, attitudes, preventive practices, and household-level entomological risk following the 2023 dengue outbreak, while enabling rapid data collection to inform public health decision-making. The study was conducted from 1 May to 31 October 2024.

Study population

The targeted population consisted of households residing in the Do and Dafra health districts of Bobo-Dioulasso. The study population included household heads or their representatives aged 18 years or older who were present at the time of data collection.

Inclusion criteria

Households were eligible if the household head or an adult representative (≥18 years) resided in the Do or Dafra health districts at the time of the survey. Households with a current or recent history of dengue infection were also included.

Exclusion criteria

Households were excluded if the household head or eligible representative was absent at the time of the visit or declined to participate in the study.

Sampling and sample size

Households were selected using simple random sampling from a database derived from a recent exhaustive household enumeration conducted prior to the 2022 long-lasting insecticidal net (LLIN) distribution campaign in the Do and Dafra health districts. Random selection was performed using computer-generated random numbers. When the household head was absent, up to two revisits were conducted. If the household remained unavailable after these visits, it was replaced using the same random selection procedure within the same health district. The minimum sample size was calculated using Schwartz’s formula:

assuming an expected proportion (p) of 50%, a type I error of 5%, and a precision (d) of 5%. This yielded a minimum required sample size of 384 households. To account for potential non-response, the sample size was increased by 10%, resulting in an expected sample of 422 households.

The sampling frame consisted of a single exhaustive household database covering both the Do and Dafra health districts. Simple random sampling was applied to the combined list without predefined quotas for each district, allowing a natural proportional allocation based on district population size. Ultimately, 402 households were successfully interviewed, including 227 households from the Do health district and 175 from the Dafra health district. Prior to data collection, the questionnaire was pre-tested in Koudougou to assess clarity, cultural appropriateness, and average interview duration.

Data collection techniques and tools

KAP component

Data were collected through face-to-face interviews with household heads or their representatives aged 18 years or older. A structured questionnaire was administered in French or local languages (Dioula, Mooré, Bwamu, and Djan), depending on participants’ preferences. The questionnaire assessed knowledge (vector, modes of transmission, symptoms, and prevention), attitudes (perceived severity, perceived vulnerability, and healthcare-seeking behavior), and preventive practices (use of mosquito nets, elimination of stagnant water, and environmental sanitation). Responses were recorded using a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.”

In addition, direct observation of dwellings and their immediate surroundings was conducted to assess the actual implementation of selected preventive practices, including the presence of stagnant water, environmental cleanliness, and the elimination of potential breeding sites. The questionnaire was adapted from previously published dengue Knowledge–Attitude–Practice (KAP) surveys [19,20] and contextualized to the local setting. It was pre-tested in a non-study area (Koudougou) to assess clarity, cultural relevance, and interview duration, and minor revisions were made accordingly. Formal psychometric validation was not conducted and is acknowledged as a limitation of the study.

Entomological component

The presence of larval breeding sites was assessed through direct observation in all surveyed households. Adult mosquito sampling was conducted in a subsample of approximately sixty households. This subsample size was determined based on operational feasibility constraints, including the limited availability of mosquito aspiration devices and the restricted number of adequately trained personnel. A purposive sampling approach was therefore adopted to ensure acceptable methodological quality while maintaining safe and standardized field implementation. Households included in the entomological component were randomly selected from among those participating in the KAP survey.

Six field teams, each composed of a health technician and a community worker specifically trained in dengue vector detection and collection, conducted the entomological activities. Each team carried out mosquito aspirations in ten households. Collections were performed early in the morning, between 6:00 and 9:00 a.m., to maximize the likelihood of capturing resting adult mosquitoes and to minimize variability related to mosquito activity.

In each household, two areas were systematically explored: (1) indoor spaces, including dark corners, curtains, under beds, wardrobes, and bathrooms; and (2) outdoor areas, including courtyards and surrounding environments, with particular attention to containers, flower pots, used tyres, drums, gutters, and other potential larval habitats. Aspiration procedures were standardized across all sampled households. The same Prokopack aspirators were used by all teams, and a similar aspiration duration of approximately 10 minutes per household (about 5 minutes indoors and 5 minutes outdoors) was applied, following identical surface and overhead aspiration protocols to ensure data comparability. Environmental conditions were broadly similar across collection sites, and all activities were conducted during the dengue transmission season.

Collected mosquitoes were placed in pre-labelled entomological containers indicating the household code, capture site (indoor or outdoor), date, and health district. Samples were stored in refrigerated coolers and transported on the same day to the Fundamental Entomology Laboratory of Joseph Ki-Zerbo University. Morphological identification was performed under a stereomicroscope using standardized taxonomic keys, in accordance with World Health Organization entomological guidelines, drawing on classical reference works by Gillies & De Meillon and Edwards [21]. Captured specimens were classified by genus and sex and recorded on standardized laboratory forms.

Operational definitions

- Knowledge was assessed using 13 items covering modes of transmission, symptoms, and preventive measures. Each correct response was assigned one point. Good knowledge was defined as a score equal to or above the median (≥10 out of 13).

- Attitudes were measured using five items related to perceived disease severity, perceived personal vulnerability, confidence in preventive measures, and healthcare-seeking intentions. Favorable attitudes were defined as scores equal to or above the median (≥4 out of 5).

- Preventive practices were assessed using seven items related to the use of long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs), environmental sanitation, elimination of stagnant water, compound cleaning, and use of mosquito repellents. Good preventive practices were defined as scores equal to or above the median (≥5 out of 7).

- Household economic level was estimated using a composite asset-based index derived from ownership of seven items: telephone, television, computer, motorized vehicle, access to running water, access to electricity (or solar energy), and livestock.

- A larval breeding site was defined as any natural or artificial container holding stagnant water and containing at least one immature mosquito stage (egg, larva, or pupa). Breeding sites could be located inside dwellings or in adjacent outdoor areas (courtyards or compounds). A site was considered positive if it contained immature stages of Aedes mosquitoes, regardless of species.

- A household was defined as a group of related or unrelated individuals living in the same dwelling and sharing daily meals.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered using Epi Info™ version 7.2.5.0 and exported to Stata version 14.2 for statistical analysis.

Qualitative variables were summarised as frequencies and percentages, while quantitative variables were described using the median and interquartile range (IQR). For analytical purposes, Likert-scale responses were dichotomised to generate composite knowledge, attitude, and practice scores, an approach commonly used in KAP studies to enhance interpretability and comparability across studies. However, this dichotomization may have reduced variability and statistical power and is therefore acknowledged as a limitation of the analysis.

Knowledge, attitude, and practice scores were dichotomised using the median as the cut-off point to classify participants as having good or poor knowledge, favourable or unfavourable attitudes, and good or poor preventive practices. The median was chosen in the absence of standardised thresholds for dengue-related KAP scores in this context; this choice is inherently arbitrary and is acknowledged as a methodological limitation.

Associations between explanatory variables and outcomes of interest were assessed using Poisson regression with robust variance, allowing estimation of prevalence ratios (PRs) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). For categorical variables with more than two categories, global p-values were obtained using the Wald test. Variables with a p-value ≤ 0.25 in univariable analysis were retained as candidates for multivariable modelling, while epidemiologically important variables, particularly age, were included regardless of their statistical significance at the univariable level.

Multivariable analysis was performed using Poisson regression with robust variance. The final model was obtained through a backward stepwise selection procedure to achieve a parsimonious model. This analytical approach was selected because the outcomes of interest were common (prevalence >10%), a situation in which conventional logistic regression may overestimate associations when expressed as odds ratios.

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Results are presented as crude prevalence ratios (PRs) and adjusted prevalence ratios (aPRs) with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee of Burkina Faso (approval No. 2024-07-226) on 10 July 2024, prior to the initiation of data collection. Before enrollment, all participants received clear and comprehensive information regarding the study objectives, procedures, expected benefits, and the voluntary nature of participation. Written informed consent was obtained from each household head or their representative before the interview. All data collected was anonymised and used exclusively for research purposes. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the national ethical guidelines for health research in Burkina Faso.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

A total of 402 household heads were included in the study. The median age of participants was 42 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 32–54 years; range: 18–85 years). Participants aged 35–44 years, 45–55 years, and 55 years and older accounted for 22.9%, 21.9%, and 22.1% of the sample, respectively. Women represented 59.5% of respondents. Overall, 33.6% of participants had no formal education, and 26.4% belonged to the low economic level (Table 1).

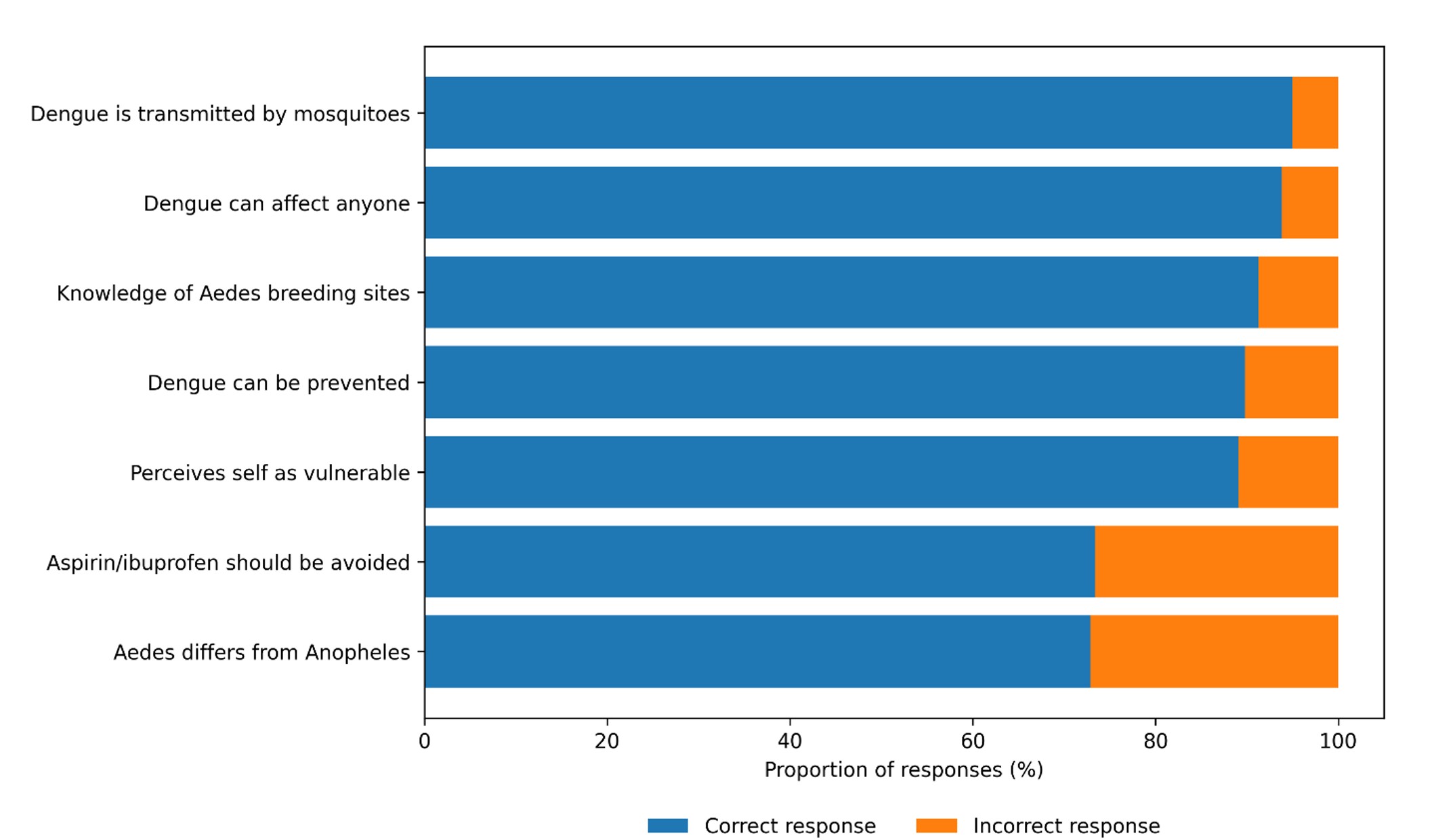

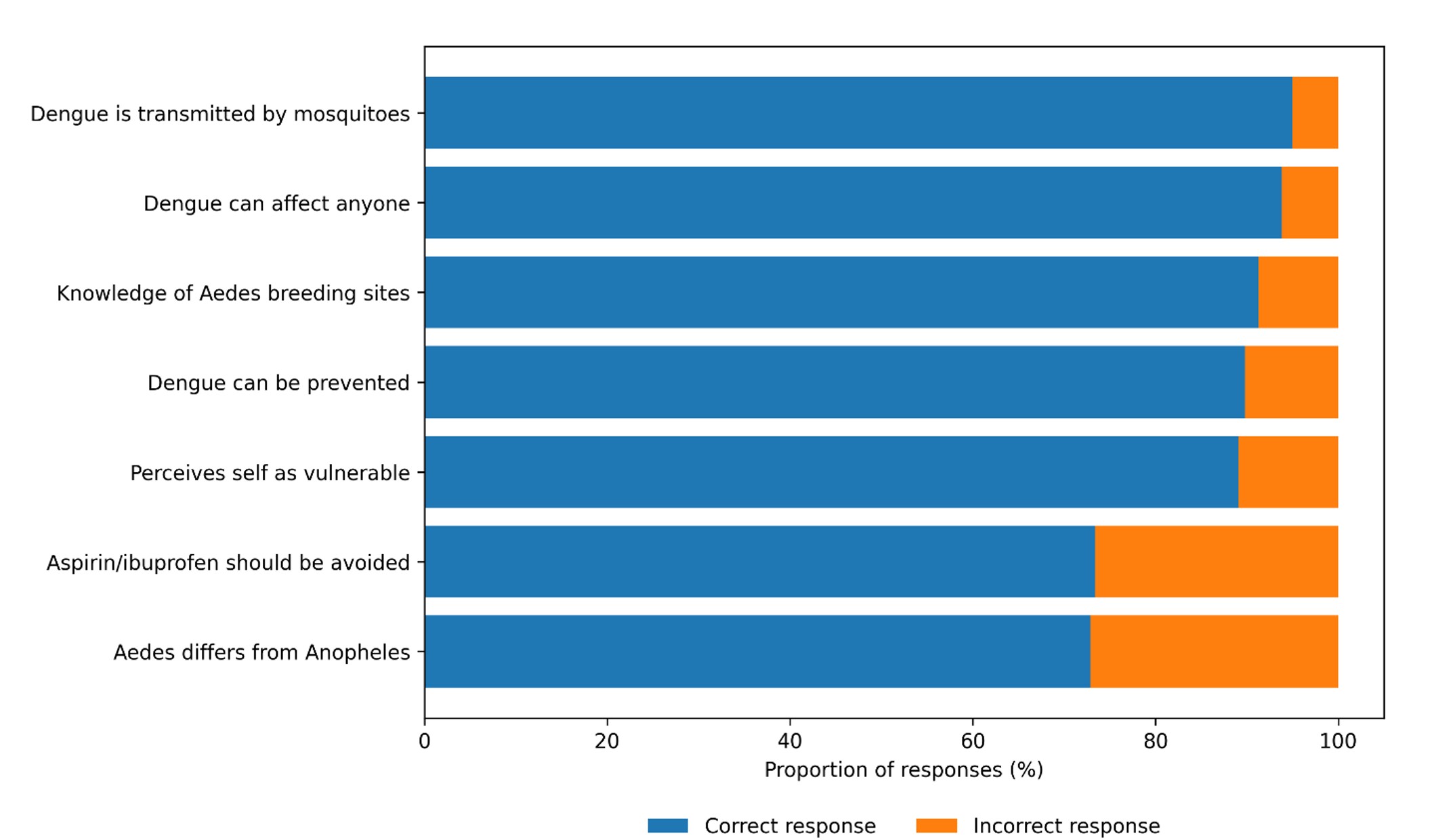

Knowledge of dengue

Mosquito bites as the mode of dengue transmission were correctly identified by 95.0% of respondents. Larval breeding sites were recognized by 91.2% of participants, and 72.9% were able to distinguish the dengue vector mosquito from the malaria vector. In addition, 93.2% of respondents perceived themselves as being vulnerable to dengue infection (Figure 1).

Attitudes toward dengue

Among the participants, 94.8% perceived dengue as a community health problem. Approximately 68.4% expressed a desire to receive more information about the disease. Overall, 94.0% reported that they would seek care at a health facility in the event of suggestive symptoms, while 33.3% indicated that they would also consult a traditional healer (Table 2).

Dengue prevention practices

Among the 402 participants, 94.0% reported adopting at least one preventive measure against dengue. The use of insecticide-treated nets was reported by 73.1% of respondents. Environmental sanitation activities were practiced by 46.0% of households, and 35.6% reported eliminating stagnant water. Other preventive measures included the use of mosquito coils (30.6%) and repellents (28.6%). Regular cleaning of household surroundings was reported by 23.9% of participants, while wearing protective clothing was mentioned by 9.5% (Table 3).

Entomological parameters

Among the 384 households inspected, 236 had at least one positive larval breeding site, corresponding to a House Index of 61.5%. A total of 1,052 adult mosquitoes were captured during aspiration activities. Of these, 705 (67.0%) were Culex quinquefasciatus, 226 (21.5%) were Aedes formosus, 110 (10.5%) were Aedes aegypti, and 11 (1.0%) were Anopheles gambiae. Among the Aedes aegypti specimens collected, 82 (73.6%) were females and 28 (26.4%) were males (Table 4).

Associated factors

Regarding healthcare-seeking behaviour in case of dengue-like symptoms (Table 5), no statistically significant differences were observed according to age, education level, occupation, or history of dengue after adjustment. However, participants with poor knowledge of the mode of dengue transmission were significantly less likely to seek care at a health facility compared with those with good knowledge (aPR = 0.68; 95% CI: 0.49–0.93). With respect to the elimination of stagnant water (Table 6), none of the variables included in the model showed a statistically significant association after adjustment.

Discussion

Guided by the Knowledge–Attitude–Practice (KAP) framework, this study assessed the population’s knowledge, attitudes, preventive practices, and household-level entomological risk related to dengue in Bobo-Dioulasso following the 2023 outbreak. Overall, the findings indicate good knowledge and generally favorable attitudes. However, preventive behaviors and environmental management remain insufficient, while entomological indicators confirm a persistent risk of dengue transmission.

A high proportion of respondents correctly identified mosquitoes as the vector of dengue (95.0%) and recognized larval breeding sites (91.3%). Similar findings have been reported in several West African settings, where recent epidemics and communication efforts contributed to increased awareness [19,22,23]. However, about one quarter (27.1%) of respondents were still unable to clearly distinguish the dengue vector mosquito from the malaria vector, an observation also reported in Senegal [24]. This persistent confusion highlights the need to reinforce communication strategies with more technically accurate content and practical demonstrations.

Participants largely perceived dengue as a community health concern (94.8%) and reported willingness to seek care in health facilities in case of suggestive symptoms (94.0%). Nevertheless, one-third (33.3%) also indicated they would consult traditional healers, a trend similarly reported in Nigeria and Benin [20,23]. This underscores the importance of involving community leaders and traditional practitioners in awareness strategies to reduce consultation delays and discourage inappropriate self-medication.

Despite high levels of knowledge, preventive practices were less consistently implemented. While the use of insecticide-treated nets was common (73.1%), environmental sanitation activities were reported by less than half of households (46.0%), and only 35.6% regularly eliminated stagnant water. Similar discrepancies between knowledge and behaviour have been documented in a previous study from Nigeria [20]. This gap remains a recurring challenge in dengue control and suggests the need for integrated interventions combining communication, provision of equipment, and structured community mobilization.

From a behavioral theory perspective, these findings are consistent with established health behavior models, including the Knowledge–Attitude–Practice framework and the PRECEDE–PROCEED model described by Green and colleagues [25]. These models emphasise that while knowledge and favourable attitudes are important prerequisites, they are often insufficient on their own to produce sustained behavioural change in the absence of enabling and reinforcing factors. In the context of dengue prevention, structural constraints, environmental conditions, and social norms may therefore limit the translation of knowledge into effective preventive practices, particularly with regard to environmental management.

In Burkina Faso, dengue prevention and control activities are led by national and subnational health authorities and include routine epidemiological surveillance, outbreak response coordination, vector control interventions, and social and behavioural change communication, particularly during epidemic periods. Monitoring of these activities relies mainly on routine surveillance data, outbreak investigation reports, and periodic public health bulletins. However, the effectiveness of these interventions may be constrained by operational challenges such as limited financial and human resources, rapid and often unplanned urbanization, difficulties in sustaining environmental management activities, and the predominantly reactive nature of vector control interventions. These contextual limitations may partly explain the persistence of dengue transmission despite ongoing prevention and control efforts.

The analysis of associated factors showed that poor knowledge of transmission was significantly associated with lower healthcare-seeking behaviour, with participants having poor knowledge being less likely to seek care at a health facility compared with those with good knowledge (aPR = 0.68; 95% CI: 0.49–0.93). This finding is consistent with studies conducted in Venezuela and Singapore, where adequate knowledge was shown to facilitate appropriate care-seeking [26,27], reinforcing the central role of effective health education.

From an entomological perspective, a high proportion of households harbored positive breeding sites, with 61.5% of inspected households presenting at least one positive larval site. This finding corresponds to a high House Index (HI), a classical larval indicator recommended by the World Health Organization to assess dengue transmission risk at the household level. Elevated HI values are generally associated with increased mosquito density and higher transmission potential and are often reported alongside high Container Index values and other larval indices. Although the Container Index and Breteau Index could not be calculated in this study due to the absence of container-level data, the observed high HI provides a relevant proxy for household-level larval infestation and supports the presence of a sustained risk of dengue transmission.

Among the 1,052 adult mosquitoes captured, 10.5% were Aedes aegypti, of which 73.6% were females, confirming a sustained risk of transmission. These findings are consistent with observations reported in Abidjan and other African urban settings [28]. Beyond local behavioural and environmental determinants, these results align with broader evidence showing the continued expansion of Aedes populations globally, influenced by climate variability, urbanisation, and ecological changes [5–7]. Furthermore, increasing evidence of insecticide resistance among mosquito vectors, including Culex and Aedes species, represents an emerging threat that may limit the effectiveness of current control measures and requires close monitoring [9,10]. Strengthening surveillance, including entomological monitoring and integration of innovative tools such as geospatial risk prediction and remote sensing technologies, has been recommended to enhance preparedness and response to arboviral outbreaks [29,30].

Altogether, our findings highlight the need for a comprehensive approach to dengue prevention, combining sustained community engagement, strengthened environmental management, improved communication strategies, and robust entomological surveillance, in line with current international evidence.

Study limitations

Given the cross-sectional design, causal relationships cannot be established. Self-reported data expose the study to social desirability bias, and the survey was limited to the districts of Do and Dafra, which restricts generalizability to the entire city. Finally, entomological collections were performed in a subsample of households, which may lead to an underestimation of certain indices.

Conclusion

This study, conducted in Bobo-Dioulasso following the 2023 dengue outbreak, indicates that although community knowledge and attitudes toward dengue were generally good, preventive practices remain insufficient, particularly with regard to environmental sanitation and the elimination of stagnant water. Healthcare-seeking intentions were high; however, the concurrent use of traditional care persists. In addition, the high proportion of households with positive breeding sites (61.5%) and the presence of Aedes aegypti females indicate a sustained household-level entomological risk of transmission.

These findings underscore the need to strengthen community engagement and health education through technically accurate and practical messages, while reinforcing environmental management and source reduction activities. Integrating behavioral interventions with routine entomological surveillance and strengthened vector control strategies is essential to reduce dengue transmission risk in urban settings such as Bobo-Dioulasso.

What is already known about the topic

- Dengue is an emerging viral disease in Burkina Faso, responsible for recurrent epidemics since 2013.

- KAP studies conducted in Africa generally report good levels of knowledge but limited preventive practices.

- Aedes aegypti is recognized as the primary vector of dengue transmission in tropical urban settings.

What this study adds

- It provides updated (2024) data on the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of the population of Bobo-Dioulasso regarding dengue, in a context of epidemic resurgence.

- It highlights a marked gap between high levels of knowledge and limited preventive practices, particularly insufficient elimination of stagnant water and inadequate environmental sanitation.

- It shows that healthcare-seeking behaviour is influenced by occupation and knowledge of the mode of transmission, underscoring the need for communication strategies tailored to groups less likely to seek care.

- It confirms a significant entomological risk, with 61.5% of households presenting positive breeding sites and the detection of female Aedes aegypti, indicating persistent vulnerability to transmission.

- It reveals vector cohabitation between Aedes aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus, supporting the need for a continuous and integrated vector control approach.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Regional Health Directorate of the Hauts-Bassins region and the health districts of Do and Dafra for their institutional support. They express their gratitude to the Community-Based Health Workers (CBHWs) and community volunteers who contributed to data collection and translation of the questionnaires into local languages. The authors also thank all study participants for their availability and cooperation. Finally, they acknowledge the technical and financial support of the African Field Epidemiology Network (AFENET), the U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI/USAID), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Abbreviations

KAP: Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices

Aedes spp.: Aedes mosquitoes

LLIN: Long-Lasting Insecticidal Net

RHD: Regional Health Directorate

PHC: Primary Health Care Center (equivalent of CSPS — Centre de Santé et de Promotion Sociale)

CMA: Medical Centre with Surgical Unit

DH: District Hospital

95% CI: 95% Confidence Interval

PR: Prevalence Ratio

aPR: Adjusted Prevalence Ratio

IQR: Interquartile Range

Authors´ contributions

Bagaya Saïdou-Mady: study design, supervision, data analysis, and manuscript writing; Nacro Wendlassida-N. Aboubacar, Compaore Toussaint, Zett Christian Manuel, Daourou Pananou, Sou Dahourou, Ouedraogo Kouka Ousséni, Pikbougoum Evariste, Barry Ousseni, Abga Roland Lamoussa, Traore Alphonse: study design, data collection, validation, and organization; Yelbeogo Denis, Kabore Bérenger: contribution to data analysis and interpretation; Ouedraogo Hamed, Yelbeogo Denis, Kabore Bérenger, Seogo Hamadou: critical revision of the manuscript and substantial intellectual input. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

| Characteristics | n | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–24 | 37 | 9.20 |

| 25–34 | 96 | 23.88 |

| 35–44 | 92 | 22.89 |

| 45–54 | 88 | 21.89 |

| ≥55 | 89 | 22.14 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 163 | 40.55 |

| Female | 239 | 59.45 |

| Education level | ||

| None | 135 | 33.58 |

| Primary | 122 | 30.35 |

| Secondary or higher | 145 | 36.07 |

| Economic level* | ||

| Low | 106 | 26.37 |

| Medium | 224 | 55.72 |

| High | 72 | 17.91 |

| Occupation | ||

| Agriculture | 12 | 2.99 |

| Trade | 85 | 21.14 |

| Salaried / Self-employed | 130 | 32.34 |

| Unemployed / Homemaker | 175 | 43.53 |

| Attitudes | n | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Perceives dengue as a community health problem | 381 | 94.8 |

| Wishes to receive more information | 275 | 68.4 |

| Would seek care at a health facility | 378 | 94.0 |

| Would also consult a traditional healer | 134 | 33.3 |

| Practice | n | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Implements at least one preventive measure | 378 | 94.0 |

| Uses an insecticide-treated net | 294 | 73.1 |

| Practices environmental cleaning | 185 | 46.0 |

| Eliminates stagnant water | 143 | 35.6 |

| Uses mosquito coils | 123 | 30.6 |

| Uses repellents | 115 | 28.6 |

| Regularly cleans household surroundings | 96 | 23.9 |

| Wears protective covering clothing | 38 | 9.5 |

Note: N = 402 corresponds to the total number of participants surveyed.

| Parameter | n | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Households inspected | 384 | |

| Households with positive larval breeding sites | 236 | 61.5 |

| Mosquito species captured (n = 1,052) | ||

| Species | n | % |

| Culex quinquefasciatus | 705 | 67.0 |

| Aedes formosus | 226 | 21.5 |

| Aedes aegypti | 110 | 10.5 |

| Anopheles gambiae | 11 | 1.0 |

| Distribution of Aedes aegypti (n = 110) | ||

| Sex | n | % |

| Females | 82 | 73.6 |

| Males | 28 | 26.4 |

Note: The House Index represents the proportion of households with at least one positive breeding site. Adult mosquito captures were conducted in a subsample of households, as described in the Methods section.

| Characteristics | Yes n (%) | No n (%) | Crude PR | 95% CI | Adjusted PR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||

| 18–24 | 35 (94.59) | 2 (5.41) | Ref | ||

| 25–34 | 90 (94.79) | 5 (5.21) | 1.00 | 0.91–1.09 | 0.99 (0.92–1.07) |

| 35–44 | 87 (94.57) | 5 (5.43) | 0.99 | 0.91–1.09 | 0.99 (0.92–1.07) |

| 45–55 | 82 (93.18) | 6 (6.82) | 0.99 | 0.89–1.08 | 0.98 (0.90–1.07) |

| ≥55 | 82 (92.13) | 7 (7.87) | 0.97 | 0.88–1.07 | 0.96 (0.88–1.04) |

| Education level | |||||

| None | 125 (92.59) | 10 (7.41) | Ref | ||

| Primary | 110 (90.16) | 12 (9.84) | 0.90 | 0.90–1.05 | 0.95 (0.88–1.03) |

| Secondary / Higher | 142 (97.93) | 3 (2.07) | 1.05 | 1.00–1.11 | 1.02 (0.97–1.07) |

| Profession | |||||

| Unemployed / Housewife | 162 (92.57) | 13 (7.43) | Ref | ||

| Agriculture | 12 (100) | 0 | 1.08 | 1.10–1.15 | 1.12 (1.03–1.21) |

| Commerce | 77 (90.59) | 8 (9.41) | 0.97 | 0.90–1.06 | 0.96 (0.88–1.04) |

| Salaried / Independent | 126 (92.92) | 4 (3.08) | 1.04 | 0.99–1.10 | 1.04 (0.98–1.09) |

| History of dengue | |||||

| Yes | 53 (94.64) | 3 (5.36) | Ref | ||

| No | 323 (93.62) | 22 (6.38) | 0.98 | 0.92–1.05 | 0.98 (0.91–1.06) |

| Knowledge of transmission | |||||

| Good | 364 (95.29) | 18 (4.71) | Ref | ||

| Poor | 13 (65.00) | 7 (35.00) | 0.68* | 0.49–0.94 | 0.68* (0.49–0.93) |

Notes: PR = prevalence ratio; aPR = adjusted prevalence ratio. Robust Poisson models adjusted for age,

education level, occupation, history of dengue, and knowledge of the mode of transmission.

Reference categories: age 18–24 years; no formal education; Unemployed/Housewife; good knowledge.

* p < 0.05. Wald χ²(9) = 19.52; p = 0.021.

| Characteristics | Elimination of stagnant water | Crude PR | 95% CI | Adjusted PR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n (%) | No n (%) | ||||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 18–24 | 30 (81.08) | 7 (18.92) | Ref | – | Ref (–) |

| 25–34 | 56 (58.33) | 40 (41.67) | 0.71 | 0.57–0.90 | 0.72 (0.56–0.93) |

| 35–44 | 58 (63.04) | 34 (36.96) | 0.77 | 0.62–0.96* | 0.77 (0.60–0.99) |

| 45–55 | 32 (36.36) | 56 (63.64) | 0.78 | 0.62–0.97* | 0.77 (0.60–0.99) |

| ≥55 | 59 (66.29) | 30 (33.71) | 0.80 | 0.65–1.01 | 0.88 (0.63–1.02) |

| Education level | |||||

| None | 94 (69.63) | 41 (30.37) | Ref | ||

| Primary | 68 (63.93) | 44 (36.07) | 0.90 | 0.77–1.09 | 0.92 (0.77–1.10) |

| Secondary/Higher | 87 (60.00) | 58 (40.00) | 0.86 | 0.72–1.02 | 0.83 (0.68–1.01) |

| Profession | |||||

| Unemployed/Housewife | 123 (70.29) | 52 (29.71) | Ref | ||

| Agriculture | 7 (58.33) | 5 (41.67) | 0.82 | 0.50–1.35 | 0.82 (0.50–1.33) |

| Commerce | 50 (58.82) | 35 (41.18) | 1.00 | 0.60–1.68 | 0.86 (0.70–1.07) |

| Salaried/Independent | 79 (60.77) | 51 (39.23) | 1.04 | 0.63–1.71 | 0.93 (0.77–1.11) |

| History of dengue | |||||

| Yes | 37 (66.07) | 19 (33.93) | Ref | ||

| No | 211 (64.06) | 124 (35.94) | 0.96 | 0.79–1.18 | 0.99 (0.80–1.21) |

| Knowledge of transmission | |||||

| Good | 243 (63.61) | 139 (36.39) | Ref | ||

| Poor | 16 (80.00) | 4 (20.00) | 1.25 | 0.99–1.50 | 1.18 (0.94–1.48) |

References

- World Health Organization. Dengue [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2025 Aug 21 [cited 2026 Feb 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue.

- Mustafa MS, Rasotgi V, Jain S, Gupta V. Discovery of fifth serotype of dengue virus (DENV-5): a new public health dilemma in dengue control [Internet]. Med J Armed Forces India. 2014 Nov 24 [cited 2026 Feb 4];71(1):67–70. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0377123714001725 doi:10.1016/j.mjafi.2014.09.011.

- Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, Drake JM, Brownstein JS, Hoen AG, Sankoh O, Myers MF, George DB, Jaenisch T, Wint GRW, Simmons CP, Scott TW, Farrar JJ, Hay SI. The global distribution and burden of dengue [Internet]. Nature. 2013 Apr 25 [cited 2026 Feb 4];496(7446):504–7. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature12060 doi:10.1038/nature12060.

- World Health Organization (Western Pacific Region). Dengue Situation Update 663 [Internet]. Manila (Philippines): World Health Organization (Western Pacific Region); 2023 Jan 19 [cited 2026 Feb 4]. 7 p. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/365676/Dengue-20230119.pdf.

- Abbasi E. The impact of climate change on travel-related vector-borne diseases: a case study on dengue virus transmission [Internet]. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2025 Mar 19 [cited 2026 Feb 4];65:102841. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S147789392500047X doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2025.102841.

- Abbasi E. Global expansion of Aedes mosquitoes and their role in the transboundary spread of emerging arboviral diseases: a comprehensive review [Internet]. IJID One Health. 2025 Mar 4 [cited 2026 Feb 4];6:100058. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S294991512500006X doi:10.1016/j.ijidoh.2025.100058.

- World Health Organization (Regional Office for Africa). Dengue in the WHO African Region: Situation Report 01: 19 December 2023 [Internet]. Brazzaville (Congo): World Health Organization (Regional Office for Africa); 2023 Dec 19 [cited 2026 Feb 4]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/countries/burkina-faso/publication/dengue-who-african-region-situation-report-01-19-december-2023.

- Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak updates on dengue fever in West Africa, including Burkina Faso [Internet]. Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention; 2025 Mar 31 [cited 2026 Feb 4]. 12 p. Available from: https://khub.africacdc.org/storage/uploads/publications/a2819f09aed4f55d28633203f978b31f.pdf.

- Ministère de la Santé et de l’Hygiène Publique (Burkina Faso). Annuaire statistique 2023 [National Statistical Yearbook 2023] [Internet]. Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso): Ministère de la Santé et de l’Hygiène Publique (Burkina Faso); 2024 Jul [cited 2026 Feb 4]. 420 p. Available from: http://cns.bf.

- World Health Organization (Regional Office for Africa). Weekly Bulletin on Outbreak and other Emergencies: Week 04: 20 to 26 January 2025 [Internet]. Brazzaville (Congo): World Health Organization (Regional Office for Africa); 2025 Jan 26 [cited 2026 Feb 4]. 19 p. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/380354.

- Ministère de la Santé et de l’Hygiène Publique (Burkina Faso). Bulletin National de Santé Publique [National Public Health Bulletin] [Internet]. Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso): Bulletin National de Santé Publique de Burkina Faso; 2023 [cited 2026 Feb 4]. 42 p. Available from: https://www.sante.gov.bf/fileadmin/user_upload/bsp_301223_nume__ro_1_final.pdf.

- Abbasi E. The impact of climate change on Aedes aegypti distribution and dengue fever prevalence in semi-arid regions: a case study of Tehran Province, Iran [Internet]. Environ Res. 2025 Mar 19 [cited 2026 Feb 4];275:121441. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0013935125006929 doi:10.1016/j.envres.2025.121441.

- Gubler DJ. Dengue, urbanization and globalization: the unholy trilogy of the 21st century [Internet]. Trop Med Health. 2011 Aug 25 [cited 2026 Feb 4];39(4 Suppl):S3–11. Available from: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/tmh/39/4SUPPLEMENT/39_2011-S05/_article doi:10.2149/tmh.2011-S05.

- Launiala A. How much can a KAP survey tell us about people’s knowledge, attitudes and practices? Some observations from medical anthropology research on malaria in pregnancy in Malawi [Internet]. Anthropol Matters. 1970 Jan 1 [cited 2026 Feb 4];11(1). Available from: https://anthropologymatters.com/index.php/anth_matters/article/view/31 doi:10.22582/am.v11i1.31.

- Abbasi E, Daliri S. Knockdown resistance (kdr) associated organochlorine resistance in mosquito-borne diseases (Culex quinquefasciatus): systematic study of reviews and meta-analysis [Internet]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2024 Aug 19 [cited 2026 Feb 4];18(8):e0011991. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0011991 doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0011991.

- Abbasi E, Vahedi M, Bagheri M, Gholizadeh S, Alipour H, Moemenbellah-Fard MD. Monitoring of synthetic insecticides resistance and mechanisms among malaria vector mosquitoes in Iran: a systematic review [Internet]. Heliyon. 2022 Jan 24 [cited 2026 Feb 4];8(1):e08830. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2405844022001189 doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08830.

- Institut National de la Statistique et de la Démographie (Burkina Faso). 5e Recensement général de la population et de l’habitation (RGPH 2019) [5th General Population and Housing Census of Burkina Faso (5th GPH)] [Internet]. Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso): Institut National de la Statistique et de la Démographie; 2019 [cited 2026 Feb 4]. 2 p. Available from: https://www.insd.bf/fr/file-download/download/public/2075.

- Institut National de la Statistique et de la Démographie (Burkina Faso). Annuaire statistique national 2023 [National Statistical Yearbook 2023] [Internet]. Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso): Institut National de la Statistique et de la Démographie; 2024 Dec [cited 2026 Feb 4]. 378 p. Available from: https://www.insd.bf/sites/default/files/2025-01/Annuaire%20statistique%20national%202023.pdf.

- Diaz-Quijano FA, Martínez-Vega RA, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Rojas-Calero RA, Luna-González ML, Díaz-Quijano RG. Association between the level of education and knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding dengue in the Caribbean region of Colombia [Internet]. BMC Public Health. 2018 Jan 16 [cited 2026 Feb 4];18(1):143. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-018-5055-z doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5055-z.

- Oche OM, Yahaya M, Oladigbolu RA, Ango JT, Okafoagu CN, Ezenwoko Z, Ijapa A, Danmadami AM. A cross-sectional survey of knowledge, attitude, and practices toward dengue fever among health workers in a tertiary health institution in Sokoto state, Nigeria [Internet]. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021 Oct 10 [cited 2026 Feb 4];10(10):3575–83. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_327_21 doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_327_21.

- World Health Organization. Manual on practical entomology in malaria [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 1975 [cited 2026 Feb 4]. 197 p. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/42481.

- Togan RM, Diallo AI, Zida-Compaoré WIC, Ba MF, Sadio AJ, Konu RY, Bakoubayi AW, Tchankoni MK, Gnatou GYS, Gbeasor-Komlanvi FA, Diongue FB, Tine JAD, Faye A, Ekouévi DK. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of health care professionals regarding dengue fever: need for training and provision of diagnostic equipment in Togo in 2022, a cross-sectional study [Internet]. Front Public Health. 2024 Jun 10 [cited 2026 Feb 4];12:1375773. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1375773/full doi:10.3389/fpubh.2024.1375773.

- Allanonto V, Yanogo P, Sawadogo B, Akpo Y, Noudeke ND, Saka B, Sourakatou S. Investigation des cas de dengue dans les départements de l’Atlantique, du Littoral et de l’Ouémé, Bénin, Avril-juillet 2019 [Investigation of dengue cases in the Atlantic, Littoral and Ouémé departments, Benin, April-July 2019] [Internet]. J Intervent Epidemiol Public Health. 2021 Sep 14 [cited 2026 Feb 4];4(3). Available from: https://www.afenet-journal.net/content/series/4/3/5/full/ doi:10.37432/jieph.supp.2021.4.3.03.5.

- Dieng I, Barry MA, Talla C, Sow B, Faye O, Diagne MM, Sene O, Ndiaye O, Diop B, Diagne CT, Fall G, Sall AA, Loucoubar C, Faye O. Analysis of a dengue virus outbreak in Rosso, Senegal 2021 [Internet]. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022 Dec 7 [cited 2026 Feb 4];7(12):420. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2414-6366/7/12/420 doi:10.3390/tropicalmed7120420.

- Green LW, Kreuter MW. Health program planning: an educational and ecological approach. 4th ed [Internet]. Boston (MA): McGraw-Hill; 2005 [cited 2026 Feb 4]. 458 p. Available from: https://www.mheducation.com/highered/product/health-program-planning-educational-ecological-approach-green/M9780072556834.html.

- Elsinga J, Lizarazo EF, Vincenti MF, Schmidt M, Velasco-Salas ZI, Arias L, Bailey A, Tami A. Health seeking behaviour and treatment intentions of dengue and fever: a household survey of children and adults in Venezuela [Internet]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015 Dec 1 [cited 2026 Feb 4];9(12):e0004237. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0004237 doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004237.

- Ng WL, Toh JY, Ng CJ, Teo CH, Lee YK, Loo KK, Abdul Hadi H, Noor Azhar AM. Self-care practices and health-seeking behaviours in patients with dengue fever: a qualitative study from patients’ and physicians’ perspectives [Internet]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023 Apr 27 [cited 2026 Feb 4];17(4):e0011302. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0011302 doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0011302.

- Roudnický P, Potěšil D, Zdráhal Z, Gelnar M, Kašný M. Laser capture microdissection in combination with mass spectrometry: approach to characterization of tissue-specific proteomes of Eudiplozoon nipponicum (Monogenea, Polyopisthocotylea) [Internet]. PLoS ONE. 2020 Jun 17 [cited 2026 Feb 4];15(6):e0231681. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231681 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0231681.

- Abedi-Astaneh F, Rad HR, Izanlou H, Hosseinalipour SA, Hamta A, Eshaghieh M, Ebrahimi M, Ansari-Cheshmeh MA, Pouriayevali MH, Salehi-Vaziri M, Jalali T, Talbalaghi A, Abbasi E. Extensive surveillance of mosquitoes and molecular investigation of arboviruses in Central Iran [Internet]. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2025 Jan 9 [cited 2026 Feb 4];87(1):130–7. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/10.1097/MS9.0000000000002826 doi:10.1097/MS9.0000000000002826.

- Abbasi E. Application of remote sensing and geospatial technologies in predicting vector-borne disease outbreaks [Internet]. R Soc Open Sci. 2025 Oct 15 [cited 2026 Feb 4];12(10):250536. Available from: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsos.250536 doi:10.1098/rsos.250536.