Research | Open Access | Volume 9 (1): Article 04 | Published: 06 Jan 2026

Factors associated with malaria transmission in children aged 3 to 59 months during seasonal malaria chemoprevention implementation, Kotido District, Uganda, 2024

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Tables

| Characteristic | Cases n=272 (%) | Controls n=272 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age of child in months, mean (SD) | 19 ± (15) | 20 ± (16) |

| Sex of the child | ||

| Male | 131 (48) | 110 (40) |

| Female | 141 (52) | 162 (60) |

| Primary caregivers’ level of education | ||

| No formal education | 239 (87) | 242 (88) |

| Primary | 24 (9) | 16 (6) |

| Secondary | 6 (3) | 7 (3) |

| Tertiary | 3 (2) | 7 (3) |

| Duration after SMC intake | ||

| ≤28 days | 68 (25) | 234 (86) |

| >28 days | 204 (75) | 38 (14) |

| Underlying medical condition | ||

| No | 155 (57) | 173 (64) |

| Yes | 117 (43) | 99 (36) |

| Malaria risk perception | ||

| High | 208 (76) | 262 (96) |

| Low | 64 (24) | 10 (4) |

| Used bed nets | ||

| Yes | 191 (70) | 188 (69) |

| No | 81 (30) | 84 (31) |

SD: standard deviation; SMC: seasonal malaria chemoprevention

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants, Kotido District, Uganda, September 2024

| Variable | Cases | Controls | Unadjusted odds ratio | Adjusted odds ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | uOR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR | p-value | |||

| Age of child (months), mean (SD) | 19 (±15) | 20 (± 16) | ||||||

| Age categories (months) | ||||||||

| ≤11 | 140 (51) | 138 (50) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 12–23 | 108 (40) | 113 (42) | 0.94 (0.66–1.3) | 0.843 | 0.95 (0.60–1.5) | 0.843 | ||

| 24–59 | 24 (9) | 21 (8) | 1.1 (0.60–2.1) | 0.806 | 1.9 (0.39–2.1) | 0.806 | ||

| Duration after SMC intake | ||||||||

| ≤28 days | 68 (25) | 234 (86) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| >28 days | 204 (75) | 38 (14) | 18 (12–29) | <0.0001 | 17 (11–26) | <0.0001 | ||

| Underlying medical condition | ||||||||

| No | 155 (57) | 173 (64) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 117 (43) | 99 (36) | 1.3 (0.93–1.9) | 0.12 | 1.6 (1.02–2.5) | 0.042 | ||

| Malaria risk perception | ||||||||

| High | 208 (76) | 262 (96) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Low | 64 (24) | 10 (4) | 8.1 (4.04–16) | <0.0001 | 5.03 (2.3–11) | <0.0001 | ||

| Used bed nets | ||||||||

| Yes | 191 (70) | 188 (69) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| No | 81 (33) | 84 (31) | 1.1 (0.73–1.5) | 0.78 | 1.05 (0.65–1.7) | 0.85 | ||

aOR: Adjusted odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval; cOR: Crude odds ratio

Table 2: Factors associated with malaria transmission among children aged 3–59 months during seasonal malaria chemoprevention, Kotido District, Uganda, September 2024

| Variable | Cases | Controls | Crude odds ratio | Adjusted odds ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | cOR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR | p-value | |||

| Age of child (months), mean (SD) | 19 (±15) | 20 (±16) | ||||||

| Age categories (months) | ||||||||

| ≤11 | 140 (51) | 138 (50) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 12–23 | 108 (40) | 113 (42) | 0.94 (0.66–1.3) | 0.843 | 0.95 (0.60–1.5) | 0.843 | ||

| 24–59 | 24 (9) | 21 (8) | 1.1 (0.60–2.1) | 0.806 | 1.9 (0.39–2.1) | 0.806 | ||

| Duration after SMC intake | ||||||||

| >28 days | 204 (75) | 38 (14) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≤28 days | 68 (25) | 234 (86) | 0.054 (0.035–0.084) | <0.0001 | 0.059 (0.038–0.093) | <0.0001 | ||

| Underlying medical condition | ||||||||

| No | 155 (57) | 173 (64) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 117 (43) | 99 (36) | 1.3 (0.93–1.9) | 0.12 | 1.6 (1.02–2.5) | 0.042 | ||

| Malaria risk perception | ||||||||

| High | 208 (76) | 262 (96) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Low | 64 (24) | 10 (4) | 8.1 (4.04–16) | <0.0001 | 5.03 (2.3–11) | <0.0001 | ||

| Used bed nets | ||||||||

| Yes | 191 (70) | 188 (69) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| No | 81 (33) | 84 (31) | 1.1 (0.73–1.5) | 0.78 | 1.05 (0.65–1.7) | 0.85 | ||

aOR: Adjusted odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval; cOR: Crude odds ratio

Table 3: Protective effectiveness of seasonal malaria chemoprevention among children aged 3–59 months, Kotido District, Uganda, September 2024

Figures

Figure 2: Distribution of mumps attack rates by district, Western North Region, August 2022

Keywords

- Seasonal malaria chemoprevention

- Effectiveness

- Malaria transmission

- Uganda

Charity Mutesi1,&, Richard Migisha1, Lilian Bulage1, Gerald Rukundo2, Jane Irene Nabakooza2, Patrick Kwizera1, Mathias Mulyazaawo2, Ronald Kimuli2, Benon Kwesiga1, Alex Riolexus Ario1

1Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program, Uganda National Institute of Public Health, Kampala, Uganda, 2National Malaria Elimination Division, Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda

&Corresponding author: Charity Mutesi, Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program, Uganda National Institute of Public Health, Kampala, Uganda, Email: charitymutesi@uniph.go.ug, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-5986-2211

Received: 24 Nov 2025, Accepted: 05 Jan 2026, Published: 06 Jan 2026

Domain: Infectious Disease Epidemiology, Malaria Control

Keywords: Seasonal malaria chemoprevention, effectiveness, Malaria transmission, Uganda

©Charity Mutesi et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Charity Mutesi et al., Factors associated with malaria transmission in children aged 3 to 59 months during seasonal malaria chemoprevention implementation, Kotido District, Uganda, 2024. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;9(1):04. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00303

Abstract

Introduction: Uganda introduced seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) in the Karamoja region, an area where transmission of malaria is high. While SMC is effective in similar settings, 2023 surveillance data in Kotido District showed a 15% increase in malaria incidence among children during implementation. We investigated the factors driving transmission of malaria among children aged 3 to 59 months in Kotido and assessed SMC effectiveness.

Methods: An unmatched 1:1 case-control study was conducted at three high-volume health facilities in Kotido in September 2024. Cases were children aged 3–59 months with parasitologically confirmed malaria, while the controls were children who tested negative for malaria at the same facilities, recruited concurrently. We conducted health facility exit interviews with caregivers of children to collect information on sociodemographic and clinical features. Logistic regression identified factors associated with malaria, and SMC effectiveness was computed as 1-adjusted odds ratio (aOR)*100.

Results: We enrolled 272 cases and 272 controls. Most cases were female (141, 52%). More of the cases’ caregivers had a low malaria risk perception (64, 24%) compared to those of the controls (10, 4%). SMC provided a 94% (95% CI: 91%–96%) protection against malaria in children who took it within 28 days of the previous cycle. Children who had spent more than the recommended 28 days without SMC administration (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 17, 95%CI = 11–26), those with underlying medical conditions (aOR = 1.6, 95% CI = 1.02–2.5), and those whose caregivers had a low malaria risk perception (aOR = 5.0, 95% CI=2.3–11) were at a higher risk of getting malaria.

Conclusion: Children who did not adhere to the 28-day SMC schedule, had existing health conditions, or whose caregivers perceived malaria as low risk had increased odds of contracting malaria. Strengthening adherence to SMC schedules, providing integrated care for children, and enhancing caregiver awareness could maximize SMC effectiveness and sustain malaria control efforts.

Introduction

Malaria remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality among children under five years globally, with the highest burden borne by sub-Saharan Africa [1,2]. In 2021, an estimated 227 million malaria cases occurred worldwide, with the African region accounting for about 90% of malaria deaths. Uganda is among the highest-burden countries, contributing approximately 5% of global malaria cases, highlighting the substantial risk to children under five years [3]. Young children are particularly vulnerable due to limited immunity, making targeted preventive strategies critical during periods of intense malaria transmission. Seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) is one such strategy, and it involves the intermittent administration of full therapeutic doses of antimalarial medicines to children aged 3 to 59 months during peak transmission seasons to prevent malaria episodes and related deaths [4,5].

SMC consists of monthly administration of a complete treatment regimen of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) and amodiaquine (AQ), delivered over consecutive months corresponding to the high-transmission period. Several randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that SMC can substantially reduce malaria incidence and severe disease in young children when delivered at high coverage and adherence [5]. In Uganda, SMC is primarily implemented through community-based delivery by village health teams (VHTs) who conduct household visits. During these visits, VHTs administer the first dose of SP and AQ under directly observed treatment (DOT), while caregivers are instructed to administer the remaining two daily doses of AQ at home. Age-specific dosing regimens are used for children aged 3 to <12 months and those aged 12 to 59 months to ensure safety and efficacy.

Uganda initiated the implementation of SMC in April 2021, in response to persistently high malaria transmission in the Karamoja sub-region, initially targeting Moroto and Kotido districts before expanding to nine districts [6]. The 2018 Uganda Malaria Indicator Survey identified Karamoja as having the highest malaria prevalence among children under five years [7]. Malaria transmission in the region is highly seasonal, peaking between May and September and corresponding with a unimodal rainfall pattern. The annual parasite index in Karamoja exceeds 450 cases per 1,000 population, underscoring the sustained intensity of transmission and the vulnerability of children under five years [7].

To support malaria control efforts in the region, the National Malaria Elimination Division (NMED), in collaboration with the Malaria Consortium, evaluated the effectiveness of SMC delivery in Karamoja. These evaluations demonstrated high short-term protective efficacy, with a reported 92% reduction in confirmed malaria cases among children aged 3 to 59 months in intervention districts compared to control districts over a five-month period [8,9]. Evidence from both local and regional studies indicates that SMC provides between 79% and 94% protection within the first 28 days after administration, although protection declines with time, falling to approximately 61% between days 29 and 42 [8,10].

Despite its documented effectiveness, the impact of SMC has varied across settings, including within Karamoja [11-13]. Furthermore, retrospective analyses of the routine Uganda District Health Information System 2 (DHIS2) data revealed an unexpected increase in malaria incidence and malaria-related hospitalizations among children under five years in Kotido District during the 2023 SMC cycles [14]. These findings raised concerns about ongoing malaria transmission despite SMC implementation and suggest that contextual, behavioural, programmatic, or environmental factors may be undermining the expected protective effects.

The factors contributing to continued malaria transmission among children aged 3 to 59 months during SMC implementation in Kotido District remain poorly understood. The study aimed to determine factors associated with malaria transmission among children aged 3 to 59 months during seasonal malaria chemoprevention implementation in Kotido District, Uganda, and to assess the effectiveness of SMC in this setting.

Methods

Study setting

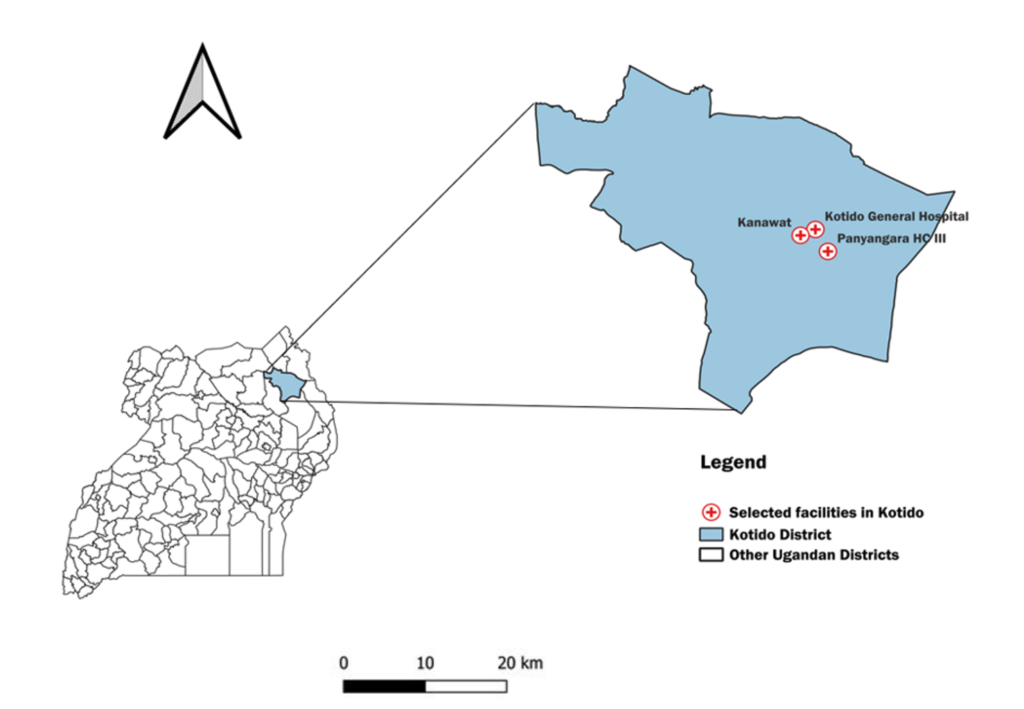

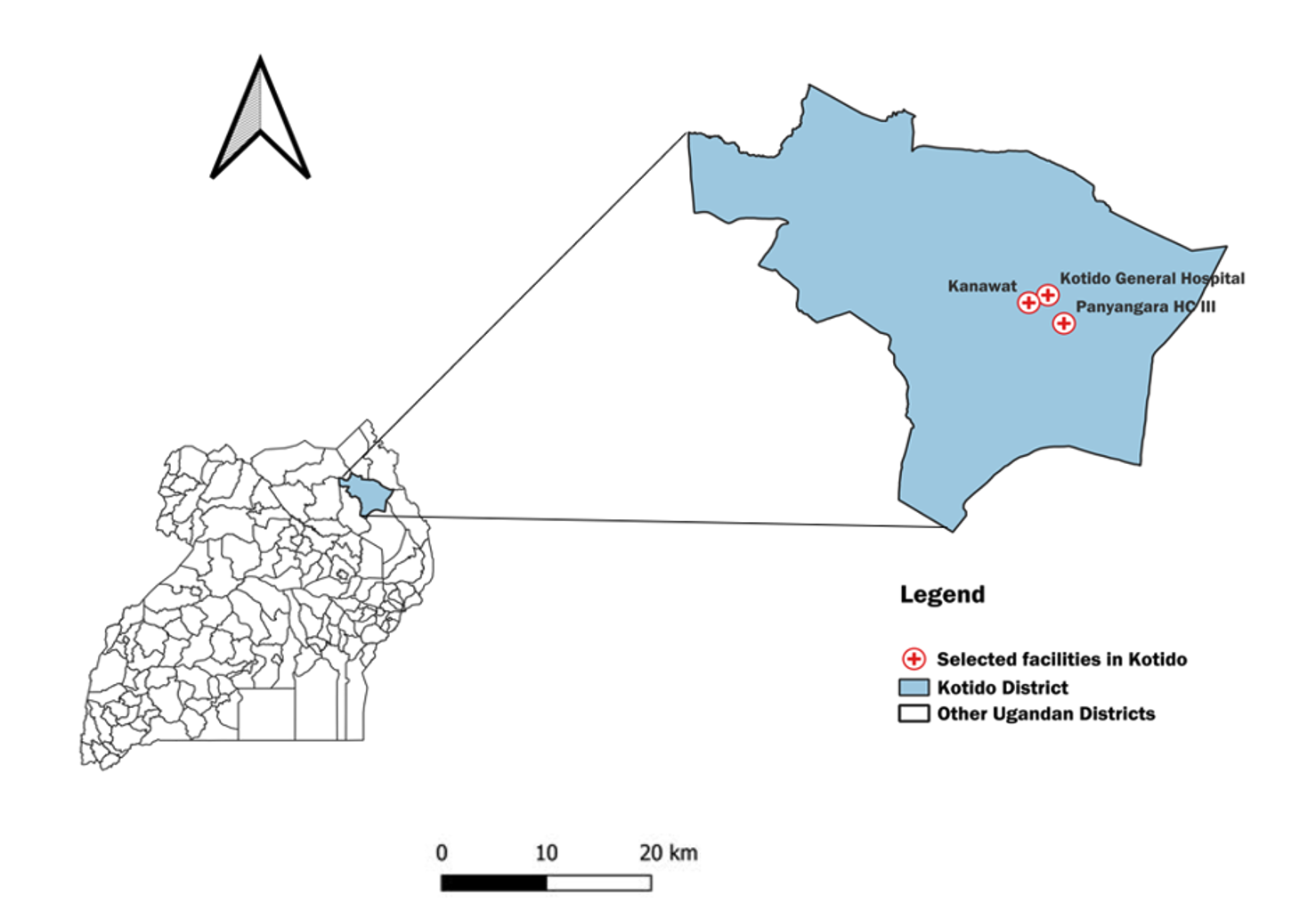

This study took place in Kotido District, situated within Uganda’s Karamoja sub-region. Karamoja’s demographic characteristics are unique, including its sparsely distributed nomadic pastoralist communities and distinct housing infrastructure, which pose challenges to conventional malaria control interventions such as indoor residual spraying [15,16]. Kotido District has 230 healthcare facilities, all providing malaria treatment services. We conducted the study in three healthcare facilities (Kotido General Hospital, Panyangara, and Kanawat Health Centre III (HCIII) (Figure 1). These were purposively chosen as they recorded the largest number of malaria cases during the 2023 implementation of SMC.

Study design

An unmatched case-control study was undertaken in selected health facilities in Kotido District in September 2024. A case was defined as a febrile child aged 3 to 59 months with parasitological confirmation of malaria according to national malaria treatment guidelines, attending the outpatient department of any of the selected three health facilities with high patient turnout. A control was defined as a child from the same facility who tested negative for malaria.

Sample size

We calculated the sample size using the Fleiss et al. formula in Open Epi software [17]. The calculation assumed a two-sided 95% confidence level, 80% power, and a 1:1 case to control ratio. Timing of SMC administration was considered the primary exposure, with an expected odds ratio of 0.49 and 20.1% of controls exposed [10]. Exposure was classified as within 28 days or ≥28 days since SMC administration, reflecting the period of highest protection against clinical malaria, which is strongest during the first four weeks and gradually thereafter [18]. The final sample included 544 participants.

Sampling procedures

During the 2024 SMC implementation, a total of 2,426 malaria cases were reported among children aged 3 to 59 months across the three high-volume health facilities: Kotido General Hospital (n=947), Panyangara (n=1,052), and Kanawat (n=427). Cases were selected proportionately to the numbers reported in each facility: 106 from Kotido General Hospital, 118 from Panyangara, and 48 from Kanawat.

The sampling interval for each facility was calculated by dividing the total number of reported cases by the required sample size: 947/106 ≈ 9 for Kotido General Hospital, 1,052/118 ≈ 9 for Panyangara Health Centre, and 427/48 ≈ 9 for Kanawat Health Centre. Within each health facility, cases were systematically selected at every 9th interval until the facility-specific sample size was reached. If a selected case did not consent or left before the interview, the next case in the register was included. Controls were selected from children attending the same facility immediately following the identification of a case.

Data collection and study variables

Exit interviews were carried out with caregivers at the selected health facilities between September 1–22, 2024. Using structured-interviewer-administered questionnaires loaded in the Kobo collect toolbox, data on sociodemographic of the children and their caregivers, caregivers’ perceptions of malaria, duration of SMC (intake of SMC within 28 days of the previous SMC cycle or beyond), use of insecticide-treated nets, and underlying medical conditions. Caregiver’s malaria risk perception was a composite variable that was assessed by three questions using a Likert scale. The questions asked caregivers whether they believed malaria could lead to serious outcomes such as death, if they thought people in their community were at risk of getting malaria, and whether they trusted government-recommended methods (such as SMC) to protect their children from the disease. Responses were then re-categorized as either having high or low malaria risk perception

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using STATA 17 (StataCorp, Texas, USA). Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables, such as the age of the child, were presented as means with standard deviation (SD). The protective effectiveness of SMC was estimated as 1–aOR (adjusted odds ratio), expressed as a percentage. Logistic regression was used to calculate both crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) to identify factors independently associated with malaria during the SMC period. The association between the outcome variable and predictor variables were evaluated using odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals. A p-value of less than 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Ethical considerations

This study was carried out as a response to a public health emergency and was classified as non-research. Administrative clearance was given by the Ministry of Health, Uganda, through the office of the Director General of Health Services to conduct the study. Furthermore, the Centre for Global Health at the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) determined that the activity did not constitute human subjects research and was primarily intended for public health practice and disease control. Written informed consent was obtained from all legal caregivers of the participants, who were informed that participation was voluntary and that declining would not lead to any negative consequences. To ensure confidentiality, unique identifiers were assigned, interviews were conducted privately, and data were stored securely under password protection by the study team. This activity was reviewed by the CDC and conducted in accordance with relevant federal laws and CDC policies (e.g., 45 C.F.R. part 46; 21 C.F.R. part 56; 42 U.S.C. §241(d); 5 U.S.C. §552a; 44 U.S.C. §3501 et seq.).

Results

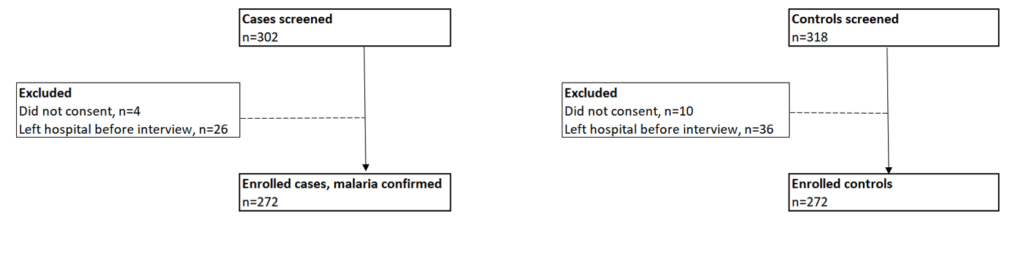

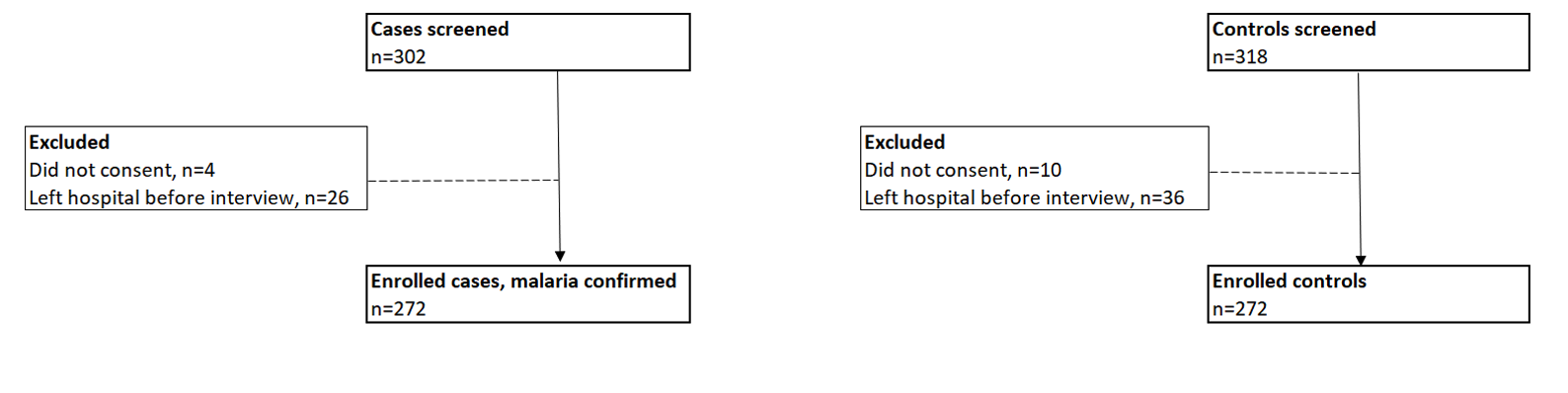

We screened 620 children and excluded 76 who either exited the facility before the interview or whose caregivers declined participation. Our study enrolled 544 children aged 3-59 months (Figure 2).

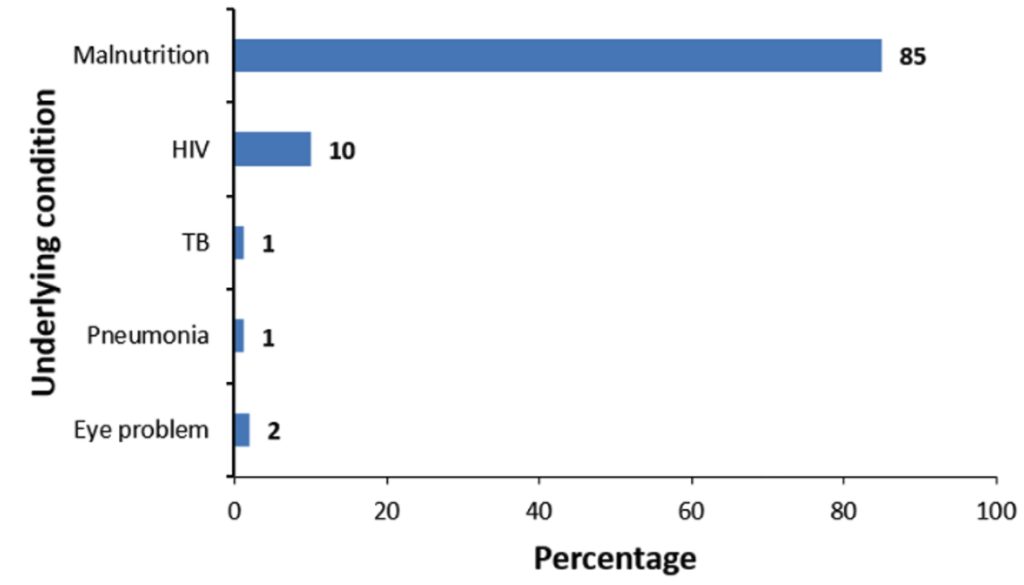

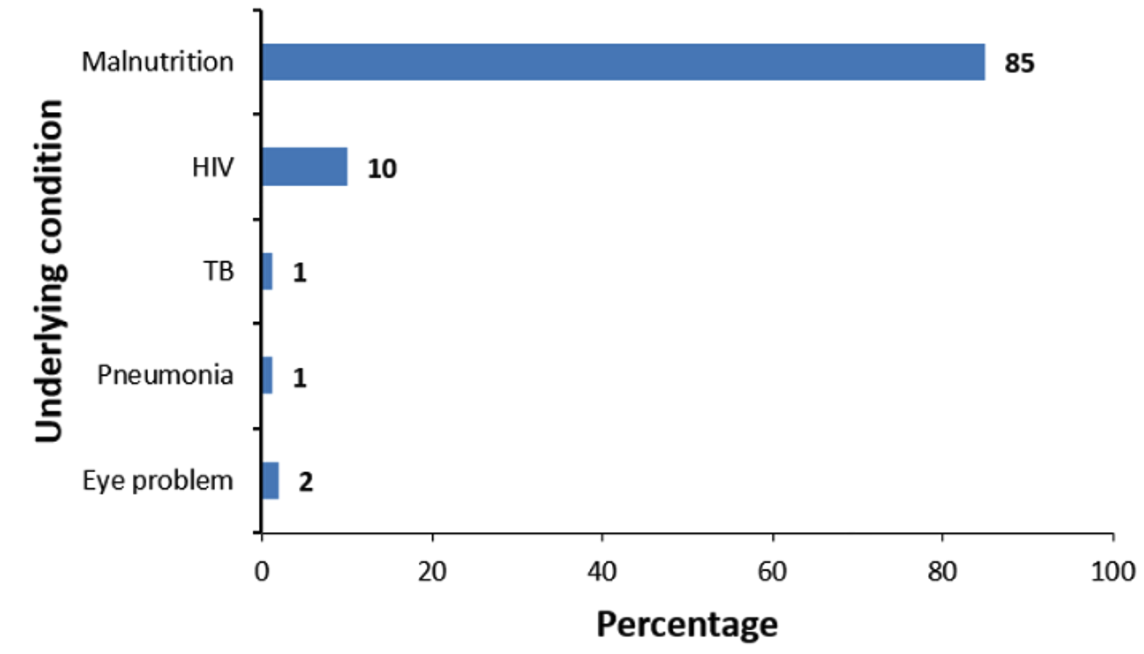

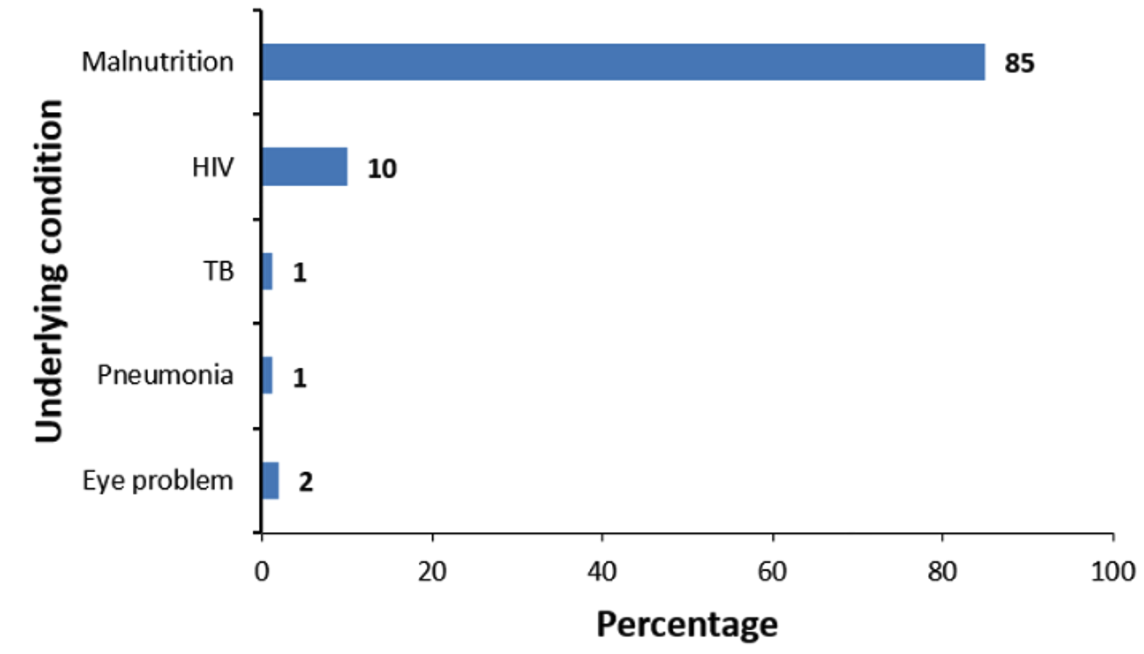

The average age of cases was slightly lower (19 ± 15 months) compared to that of controls (20 ± 16 months). Most caregivers in both the case (241, 87%) and control (242, 88%) groups had no formal education. More children in the control group (234, 86%) had received SMC within 28 days compared to the case group (68, 25%). Underlying medical conditions were more common among cases (117, 43%) than controls (99, 36%). Caregivers of controls had a higher malaria risk perception (262, 96%) compared to those of cases (208, 76%, Table 1). Among children with documented underlying conditions (n=87), malnutrition was the most frequently reported (85%), followed by HIV (10%) (Figure 3).

Determinants of malaria transmission in children aged 3 to 59 months during seasonal malaria chemoprevention, Kotido District, Uganda, September 2024

At multivariable analysis (Table 2), we adjusted for the age of the children, duration of SMC intake, underlying medical condition, malaria risk perception, and bed net usage. Children who were exposed to SMC beyond 28 days from the previous cycle had 17 times higher odds of developing malaria (aOR:17, 95% CI:11–26) compared to those who received SMC within 28 days. Similarly, children who had underlying medical conditions such as malnutrition had higher odds of getting malaria (aOR = 1.6, 95%CI:1.02–2.5) compared to those who had no underlying medical conditions. The odds of having malaria were higher among children whose caregivers had a low-risk perception of malaria (aOR:5.03, 95% CI:2.3–11) compared to children of caregivers who had a high-risk perception of malaria (Table 2).

Holding age of the children, underlying medical conditions, malaria risk perceptions, and use of bed nets, seasonal malaria chemoprevention provided a 94% (95% CI: (91%–96%) effectiveness in preventing malaria in children aged 3-59 months within 28 days of the previous SMC dose (Table 3).

Discussion

Our findings demonstrated that children who received seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) beyond the 28 days from the previous cycle, those with underlying medical conditions, and those whose caregivers had a low malaria risk perception had significantly higher odds of malaria infection. In contrast, SMC administered within 28 days of the previous cycle provided high protection against malaria, with an estimated effectiveness of 94%.

The observed protective effectiveness of SMC within the first 28 days is consistent with findings from studies conducted in Uganda and other parts of central and western Africa, which demonstrate that SMC offers substantial short-term protection when administered at recommended monthly intervals [19,20]. The significantly higher odds of malaria among children whose last SMC dose exceeded 28 days align with established evidence that SMC efficacy wanes as drug concentrations decline beyond the four weeks [21,22]. These findings underscore the importance of strict adherence to the recommended SMC dosing schedule to sustain protection during periods of high transmission. In settings where children miss or delay SMC doses, complementary interventions such as insecticide-treated net use, prompt case management, and vector control remain essential.

Children with underlying medical conditions, particularly malnutrition followed by HIV, were more likely to develop malaria compared to those without such conditions. This finding is consistent with previous studies showing that compromised nutritional and immune status increases susceptibility to malaria and other infectious diseases [23-25]. Malnutrition may impair immune responses, increase disease severity, and reduce the effectiveness of preventive interventions, including SMC. Integrating nutritional and HIV screening and support into SMC delivery and routine child health services may enhance malaria prevention efforts. Strengthening coordination between malaria and nutrition programs could further support early identification and management of vulnerable children.

Caregiver perception of malaria risk also emerged as an important factor. Children whose caregivers perceived malaria as a low-risk condition had higher odds of malaria infection compared to those whose caregivers reported a high-risk perception. This finding supports existing evidence that caregiver beliefs and risk perception influence uptake and adherence to preventive health behaviours [26,27]. Underestimation of malaria severity may reduce compliance with SMC schedules and other preventive measures, such as bed net use and timely care-seeking [28,29]. Conversely, caregivers who perceive malaria as a serious threat are more likely to engage in protective behaviours [30,31]. Targeted health education and risk communication strategies emphasising the vulnerability of young children and the consequences of missed SMC doses may improve caregiver engagement and adherence.

Study limitations

Data collection took place during a period of political unrest in the district, which limited community access and necessitated a hospital-based case-control design. Hospital-based controls may differ from community controls, potentially affecting the generalizability of our findings. Hospital-based controls may have underlying health conditions that increase their likelihood of seeking healthcare, which could lead to over- or underestimation of the association between exposure and outcome [32]. Additionally, using caregiver-reported information may introduce biases, including social desirability bias, which may either overestimate or underestimate the reported exposures. Lastly, our study did not assess environmental, socio-economic, or healthcare access factors, which could also influence malaria transmission patterns. Future studies incorporating these contextual variables would provide a more comprehensive understanding of malaria risk in similar settings.

Conclusion

Timely administration of SMC within 28 days was highly effective in protecting children against malaria in Kotido District. Children who missed the recommended SMC schedule, had underlying medical conditions, or whose caregivers perceived malaria as a low risk had significantly higher odds of malaria infection. Sustaining the protective effectiveness of SMC requires strict adherence to the 28-day dosing cycle, alongside integration of nutritional and HIV services and strengthened caregiver risk communication to improve compliance with malaria prevention interventions.

What is already known about the topic

- Malaria remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality among children under five in Uganda.

- Seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) reduces malaria risk in children aged 3–59 months in areas with seasonal transmission.

- Protection from SMC is highest within the first 28 days after administration and declines thereafter.

What this study adds

- Children who received SMC more than 28 days after the previous cycle had significantly higher odds of malaria.

- Underlying medical conditions, particularly malnutrition, increased the risk of malaria during SMC implementation.

- Low caregiver perception of malaria risk was independently associated with malaria infection.

- SMC administered within 28 days remained highly effective (94%) in preventing malaria.

- The findings highlight the need to integrate behavioural risk communication and child health services, including nutrition and HIV care, into SMC delivery to sustain its protective impact.

Funding

This project received support from the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under Cooperative Agreement number GH001353-01, administered through Makerere University School of Public Health to the Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program, Ministry of Health. The content of this manuscript is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official positions of the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, the Department of Health and Human Services, Makerere University School of Public Health, or the Uganda Ministry of Health.

Disclosure

The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, or decision to prepare or publish this manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets upon which our findings are based belong to the Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program. For confidentiality reasons, the datasets are not publicly available. The datasets can be availed upon reasonable request from the corresponding author with permission from the Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kotido District, the administration of Kotido General Hospital, Panyangara HC III, and Kanawat HC III for permitting us to conduct the study at their sites. We are grateful for the technical assistance offered by the Ministry of Health. We also acknowledge the US CDC for providing technical guidance and funding through the Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program (UPHFP), under which this study was carried out.

Authors´ contributions

CM, RM, GR, JIN, and BK were involved in developing the study concept, data collection, analyzing and interpreting the data, and drafting the initial manuscript. CM, RM, LB, GR, JIN, PK, MM, RK, BK, and ARA assessed the manuscript drafts for content and accuracy, and contributed substantial revisions. All authors reviewed and provided approval for the final manuscript.

List of abbreviations

aOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio

cOR: Crude Odds Ratio

HC: Health Centre

SMC: Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention

DOT: Directly Observed Therapy

VHTs: Village Health Teams

CI: Confidence Interval

| Characteristic | Cases n=272 (%) | Controls n=272 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age of child in months, mean (SD) | 19 ± (15) | 20 ± (16) |

| Sex of the child | ||

| Male | 131 (48) | 110 (40) |

| Female | 141 (52) | 162 (60) |

| Primary caregivers’ level of education | ||

| No formal education | 239 (87) | 242 (88) |

| Primary | 24 (9) | 16 (6) |

| Secondary | 6 (3) | 7 (3) |

| Tertiary | 3 (2) | 7 (3) |

| Duration after SMC intake | ||

| ≤28 days | 68 (25) | 234 (86) |

| >28 days | 204 (75) | 38 (14) |

| Underlying medical condition | ||

| No | 155 (57) | 173 (64) |

| Yes | 117 (43) | 99 (36) |

| Malaria risk perception | ||

| High | 208 (76) | 262 (96) |

| Low | 64 (24) | 10 (4) |

| Used bed nets | ||

| Yes | 191 (70) | 188 (69) |

| No | 81 (30) | 84 (31) |

| Variable | Cases | Controls | Unadjusted odds ratio | Adjusted odds ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | uOR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR | p-value | |||

| Age of child (months), mean (SD) | 19 (±15) | 20 (± 16) | ||||||

| Age categories (months) | ||||||||

| ≤11 | 140 (51) | 138 (50) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 12–23 | 108 (40) | 113 (42) | 0.94 (0.66–1.3) | 0.843 | 0.95 (0.60–1.5) | 0.843 | ||

| 24–59 | 24 (9) | 21 (8) | 1.1 (0.60–2.1) | 0.806 | 1.9 (0.39–2.1) | 0.806 | ||

| Duration after SMC intake | ||||||||

| ≤28 days | 68 (25) | 234 (86) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| >28 days | 204 (75) | 38 (14) | 18 (12–29) | <0.0001 | 17 (11–26) | <0.0001 | ||

| Underlying medical condition | ||||||||

| No | 155 (57) | 173 (64) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 117 (43) | 99 (36) | 1.3 (0.93–1.9) | 0.12 | 1.6 (1.02–2.5) | 0.042 | ||

| Malaria risk perception | ||||||||

| High | 208 (76) | 262 (96) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Low | 64 (24) | 10 (4) | 8.1 (4.04–16) | <0.0001 | 5.03 (2.3–11) | <0.0001 | ||

| Used bed nets | ||||||||

| Yes | 191 (70) | 188 (69) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| No | 81 (33) | 84 (31) | 1.1 (0.73–1.5) | 0.78 | 1.05 (0.65–1.7) | 0.85 | ||

| Variable | Cases | Controls | Crude odds ratio | Adjusted odds ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | cOR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR | p-value | |||

| Age of child (months), mean (SD) | 19 (±15) | 20 (±16) | ||||||

| Age categories (months) | ||||||||

| ≤11 | 140 (51) | 138 (50) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 12–23 | 108 (40) | 113 (42) | 0.94 (0.66–1.3) | 0.843 | 0.95 (0.60–1.5) | 0.843 | ||

| 24–59 | 24 (9) | 21 (8) | 1.1 (0.60–2.1) | 0.806 | 1.9 (0.39–2.1) | 0.806 | ||

| Duration after SMC intake | ||||||||

| >28 days | 204 (75) | 38 (14) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≤28 days | 68 (25) | 234 (86) | 0.054 (0.035–0.084) | <0.0001 | 0.059 (0.038–0.093) | <0.0001 | ||

| Underlying medical condition | ||||||||

| No | 155 (57) | 173 (64) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 117 (43) | 99 (36) | 1.3 (0.93–1.9) | 0.12 | 1.6 (1.02–2.5) | 0.042 | ||

| Malaria risk perception | ||||||||

| High | 208 (76) | 262 (96) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Low | 64 (24) | 10 (4) | 8.1 (4.04–16) | <0.0001 | 5.03 (2.3–11) | <0.0001 | ||

| Used bed nets | ||||||||

| Yes | 191 (70) | 188 (69) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| No | 81 (33) | 84 (31) | 1.1 (0.73–1.5) | 0.78 | 1.05 (0.65–1.7) | 0.85 | ||

References

- World Health Organization. Malaria [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2025 Dec 4 [cited 2026 Jan 6]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malaria.

- Obasohan PE, Walters SJ, Jacques R, Khatab K. A scoping review of selected studies on predictor variables associated with the malaria status among children under five years in sub-saharan africa. IJERPH [Internet]. 2021 Feb 22 [cited 2026 Jan 6];18(4):2119. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/4/2119 doi: 10.3390/ijerph18042119.

- World Health Organization. World malaria [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2022 Dec 8 [cited 2026 Jan 6]. 293 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2022.

- Ndiaye M, Sylla K, Sow D, Tine R, Faye B, Ndiaye JL, Dieng Y, Lo AC, Abiola A, Cisse B, Ndiaye D, Theisen M, Gaye O, Alifrangis M. Any impact of seasonal malaria chemoprevention on the acquisition of antibodies against glutamate-rich protein and apical membrane antigen 1 in children living in southern Senegal. The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene [Internet]. 2015 Oct 7 [cited 2026 Jan 6];93(4):798–800. Available from: https://www.ajtmh.org/view/journals/tpmd/93/4/article-p798.xml doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0808.

- Nikiema S, Soulama I, Sombié S, Tchouatieu AM, Sermé SS, Henry NB, Ouedraogo N, Ouaré N, Ily R, Ouédraogo O, Zongo D, Djigma FW, Tiono AB, Sirima SB, Simporé J. Any seasonal malaria chemoprevention implementation: Effect on malaria incidence and immunity in a context of expansion of P. falciparum resistant genotypes with potential reduction of the effectiveness in Sub-Saharan Africa. Infect Drug Resist [Internet]. 2022 Aug 13 [cited 2026 Jan 6];15:4517–27. Available from: https://www.dovepress.com/seasonal-malaria-chemoprevention-implementation-effect-on-malaria-inci-peer-reviewed-fulltext-article-IDR doi: 10.2147/IDR.S375197.

- Nakkazi E. Any resurgence of malaria chemoprevention. The Lancet Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2021 Nov [cited 2026 Jan 6];21(11):1499. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(21)00636-8/fulltext doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(21)00636-8.

- Uganda National Malaria Control Division, Uganda Bureau of Statistics, ICF. 2018-19 Uganda Malaria Indicator Survey Atlas of Key Indicators [Internet]. Rockville (Maryland): ICF; 2019 [cited 2026 Jan 6]. 12 p. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/ATR21/ATR21.pdf.

- Nuwa A, Baker K, Bonnington C, Odongo M, Kyagulanyi T, Bwanika JB, Richardson S, Nabakooza J, Salandini D, Asua V, Nakirunda M, Rassi C, Rutazaana D, Achuma R, Sagaki P, Bwanika JB, Magumba G, Yeka A, Nsobya S, Kamya MR, Tibenderana J, Opigo J. Any protective effect of SMC in the context of high parasite resistance in Uganda: a three-arm, open-label, non-inferiority and superiority, cluster-randomised, controlled trial. Malar J [Internet]. 2023 Feb 22 [cited 2026 Jan 6];22(1):63. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-023-04488-4 doi: 10.1186/s12936-023-04488-4.

- Kajubi R, Ainsworth J, Baker K, Richardson S, Bonnington C, Rassi C, Achan J, Magumba G, Rubahika D, Nabakooza J, Tibenderana J, Nuwa A, Opigo J. A hybrid effectiveness-implementation study protocol to assess the effectiveness and chemoprevention efficacy of implementing seasonal malaria chemoprevention in five districts in Karamoja region, Uganda. Gates Open Res [Internet]. 2023 Dec 18 [cited 2026 Jan 6];7:14. Available from: https://gatesopenresearch.org/articles/7-14/v2 doi: 10.12688/gatesopenres.14287.2.

- Cairns M, Ceesay SJ, Sagara I, Zongo I, Kessely H, Gamougam K, Diallo A, Ogboi JS, Moroso D, Van Hulle S, Eloike T, Snell P, Scott S, Merle C, Bojang K, Ouedraogo JB, Dicko A, Ndiaye JL, Milligan P. Effectiveness of seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) treatments when SMC is implemented at scale: Case–control studies in 5 countries. PLoS Med [Internet]. 2021 Sep 8 [cited 2026 Jan 6];18(9):e1003727. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1003727 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003727.

- Kirakoya-Samadoulougou F, De Brouwere V, Fokam AF, Ouédraogo M, Yé Y. Assessing the effect of seasonal malaria chemoprevention on malaria burden among children under 5 years in Burkina Faso. Malar J [Internet]. 2022 May 6 [cited 2026 Jan 6];21(1):143. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-022-04172-z doi: 10.1186/s12936-022-04172-z.

- Diawara F, Steinhardt LC, Mahamar A, Traore T, Kone DT, Diawara H, Kamate B, Kone D, Diallo M, Sadou A, Mihigo J, Sagara I, Djimde AA, Eckert E, Dicko A. Measuring the impact of seasonal malaria chemoprevention as part of routine malaria control in Kita, Mali. Malar J [Internet]. 2017 Aug 10 [cited 2026 Jan 6];16(1):325. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-017-1974-x doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1974-x.

- Kwiringira A, Kwesiga B, Migisha R, Bulage L, Kadobera D, Rutazaana D, Harris JR, Ario AR, Ssempiira J. Effect of seasonal malaria chemoprevention on incidence of malaria among children under five years in Kotido and Moroto Districts, Uganda, 2021: time series analysis. Malar J [Internet]. 2024 Dec 18 [cited 2026 Jan 6];23(1):389. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-024-05220-6 doi: 10.1186/s12936-024-05220-6.

- Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda. Electronic Health Information Management System [Internet]. [cited 2026 Jan 6]. Available from: https://hmis.health.go.ug/dhis-web-login/#/.

- Burns J, Bekele G, Akabwai D. Livelihood dynamics in northern Karamoja : A participatory baseline study for the growth health and governance program [Internet]. Medford (Massachusetts): Tufts University; 2013 May [cited 2026 Jan 6]. 70 p. Available from: https://fic.tufts.edu/wp-content/uploads/Livelihood-Dynamics-in-Northern-Karamoja.pdf.

- Mangeli M, Rayyani M, Cheraghi MA, Tirgari B. Exploring the challenges of adolescent mothers from their life experiences in the transition to motherhood: a qualitative study. J Family Reprod Health [Internet]. 2017 Sep [cited 2026 Jan 6];11(3):165–73. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6045691/.

- Johansson J, Tibenderana J, Abdoulaye R, Coulibaly P, Hubbard E, Jah H, Lama EK, Razafindralambo L, Van Hulle S, Jagoe G, Tchouatieu AM, Collins D, Gilmartin C, Tetteh G, Djibo Y, Ndiaye F, Kalleh M, Kandeh B, Audu B, Ntadom G, Kiba A, Savodogo Y, Boulotigam K, Sougoudi DA, Guilavogui T, Keita M, Kone D, Jackou H, Ouba I, Ouedraogo E, Messan HA, Jah F, Kaira MJ, Sano MS, Traore MC, Ngarnaye N, Elagbaje AYC, Halleux C, Merle C, Iessa N, Pal S, Sefiani H, Souleymani R, Laminou I, Doumagoum D, Kesseley H, Coldiron M, Grais R, Kana M, Ouedraogo JB, Zongo I, Eloike T, Ogboi SJ, Achan J, Bojang K, Ceesay S, Dicko A, Djimde A, Sagara I, Diallo A, NdDiaye JL, Loua KM, Beshir K, Cairns M, Fernandez Y, Lal S, Mansukhani R, Muwanguzi J, Scott S, Snell P, Sutherland C, Tuta R, Milligan P. Effectiveness of seasonal malaria chemoprevention at scale in west and central Africa: an observational study. The Lancet [Internet]. 2020 Dec 5 [cited 2026 Jan 6];396(10265):1829–40. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)32227-3/fulltext doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32227-3.

- Nuwa A, Baker K, Kajubi R, Nnaji CA, Theiss-Nyland K, Odongo M, Kyagulanyi T, Nabakooza J, Salandini D, Asua V, Nakirunda M, Rassi C, Rutazaana D, Achuma R, Sagaki P, Bwanika JB, Magumba G, Yeka A, Nsobya S, Kamya MR, Tibenderana J, Opigo J. Effectiveness of sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine plus amodiaquine and dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine for seasonal malaria chemoprevention in Uganda: a three-arm, open-label, non-inferiority and superiority, cluster-randomised, controlled trial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2025 July 1 [cited 2026 Jan 6];25(7):726–36. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(24)00746-1/fulltext doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(24)00746-1.

- Cairns M, Barry A, Zongo I, Sagara I, Yerbanga SR, Diarra M, Zoungrana C, Issiaka D, Sienou AA, Tapily A, Sanogo K, Kaya M, Traore S, Diarra K, Yalcouye H, Sidibe Y, Haro A, Thera I, Snell P, Grant J, Tinto H, Milligan P, Chandramohan D, Greenwood B, Dicko A, Ouedraogo JB. The duration of protection against clinical malaria provided by the combination of seasonal RTS,S/AS01E vaccination and seasonal malaria chemoprevention versus either intervention given alone. BMC Med [Internet]. 2022 Oct 7 [cited 2026 Jan 6];20(1):352. Available from: https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-022-02536-5 doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02536-5.

- Chotsiri P, White NJ, Tarning J. Pharmacokinetic considerations in seasonal malaria chemoprevention. Trends in Parasitology [Internet]. 2022 Jul 7 [cited 2026 Jan 6];38(8):673–82. Available from: https://www.cell.com/trends/parasitology/fulltext/S1471-4922(22)00106-4 doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2022.05.003.

- Kojom Foko LP, Eboumbou Moukoko CE, Nyabeyeu Nyabeyeu H, Tonga C, Lehman LG. Any prevalence, patterns, and determinants of malaria and malnutrition in douala, cameroon: a cross‐sectional community‐based study. Bharti P, editor. BioMed Research International [Internet]. 2021 Jul 12 [cited 2026 Jan 6];2021(1):5553344. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2021/5553344/ doi: 10.1155/2021/5553344.

- Mmbando BP, Mwaiswelo RO, Chacky F, Molteni F, Mohamed A, Lazaro S, Ngasala B. Nutritional status of children under five years old involved in a seasonal malaria chemoprevention study in the Nanyumbu and Masasi districts in Tanzania. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2022 Apr 29 [cited 2026 Jan 6];17(4):e0267670. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0267670 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0267670.

- Guerra CVC, Da Silva BM, Müller P, Baia-da-Silva DC, Moura MAS, Araújo JDA, Silva JCSE, Silva-Neto AV, Da Silva Balieiro AA, Da Costa-Martins AG, Melo GC, Val F, Bassat Q, Nakaya HI, Martinez-Espinosa FE, Lacerda M, Sampaio VS, Monteiro W. HIV infection increases the risk of acquiring Plasmodium vivax malaria: a 4-year cohort study in the Brazilian Amazon HIV and risk of vivax malaria. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2022 May 31 [cited 2026 Jan 6];12(1):9076. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-13256-4 doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-13256-4.

- Karimy M, Bastami F, Sharifat R, Heydarabadi AB, Hatamzadeh N, Pakpour AH, Cheraghian B, Zamani-Alavijeh F, Jasemzadeh M, Araban M. Factors related to preventive COVID-19 behaviors using health belief model among general population: a cross-sectional study in Iran. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Oct 24 [cited 2026 Jan 6];21(1):1934. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-021-11983-3 doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11983-3.

- Ndejjo R, Musinguzi G, Nuwaha F, Bastiaens H, Wanyenze RK. Understanding factors influencing uptake of healthy lifestyle practices among adults following a community cardiovascular disease prevention programme in Mukono and Buikwe districts in Uganda: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2022 Feb 17 [cited 2026 Jan 6];17(2):e0263867. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0263867 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0263867.

- Zou L, Ma H, Sharifi MS, Deng W, Kan X, Luo J, Bai Y, Ouyang Y, Zhou W. Correction: The perception and interpretation of malaria among Chinese construction workers in sub-Saharan Africa: a qualitative study. Malar J [Internet]. 2023 Nov 3 [cited 2026 Jan 6];22(1):332. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-023-04770-5 doi: 10.1186/s12936-023-04770-5.

- Yirsaw AN, Gebremariam RB, Getnet WA, Mihret MS. Insecticide-treated net utilization and associated factors among pregnant women and under-five children in East Belessa District, Northwest Ethiopia: using the Health Belief model. Malar J [Internet]. 2021 Mar 4 [cited 2026 Jan 6];20(1):130. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-021-03666-6 doi: 10.1186/s12936-021-03666-6.

- Aerts C, Revilla M, Duval L, Paaijmans K, Chandrabose J, Cox H, Sicuri E. Correction: Understanding the role of disease knowledge and risk perception in shaping preventive behavior for selected vector-borne diseases in Guyana. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2025 Oct 6 [cited 2026 Jan 6];19(10):e0013586. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0013586 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0013586.