Research | Open Access | Volume 9 (1): Article 27 | Published: 12 Feb 2026

Stigma and associated factors among Mpox survivors in central Uganda, August 2024–January 2025

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Tables

| Characteristic | Completed n=346 (%) | Withdrawn n=81 (%) | χ² | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 2.17 | 0.54 | ||

| 18–24 | 70 (20) | 20 (25) | ||

| 25–34 | 162 (47) | 35 (43) | ||

| 35–44 | 84 (24) | 18 (22) | ||

| ≥45 | 30 (9) | 8 (10) | ||

| Sex | 0.12 | 0.73 | ||

| Female | 149 (43) | 33 (41) | ||

| Male | 197 (57) | 48 (59) | ||

| Hospital stay (days) | 0.66 | 0.72 | ||

| 1–7 | 232 (67) | 51 (63) | ||

| 8–14 | 88 (25) | 21 (26) | ||

| >14 | 26 (8) | 9 (11) |

| Characteristics (n=346) | Frequency | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–24 | 70 | (20) |

| 25–34 | 162 | (47) |

| 35–44 | 84 | (24) |

| ≥45 | 30 | (9) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 149 | (43) |

| Male | 197 | (57) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 138 | (40) |

| Married | 151 | (44) |

| Separated/Widowed | 57 | (16) |

| Education level | ||

| No formal education/Primary | 130 | (38) |

| Secondary | 161 | (46) |

| Tertiary | 55 | (16) |

| Sex work | ||

| No | 312 | (90) |

| Yes | 34 | (10) |

| Hospital stay (days) | ||

| 1–7 | 232 | (67) |

| 8–14 | 88 | (25) |

| >14 | 26 | (8) |

| Co-morbidities | ||

| No | 228 | (66) |

| Yes | 118 | (34) |

Table 2: Socio-demographic characteristics of mpox survivors in Kampala Metropolitan Area, August 2024–January 2025

| Characteristics | Stigma (n=87) | (%) | No stigma (n=259) | (%) | cPR | (95%CI) | aPR | (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 49 | (56) | 100 | (39) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Male | 38 | (44) | 159 | (61) | 0.59 | (0.41-0.85) | 0.57 | (0.39-0.84) |

| Hospital stay (days) | ||||||||

| 1–7 | 48 | (55) | 184 | (71) | Ref | Ref | ||

| 8–14 | 29 | (33) | 59 | (23) | 1.60 | (1.10-2.40) | 1.70 | (1.10-2.50) |

| >14 | 10 | (12) | 16 | (6) | 1.90 | (1.07-3.20) | 2.50 | (1.30-4.50) |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| 18–24 | 18 | (21) | 52 | (20) | Ref | Ref | ||

| 25–34 | 44 | (51) | 118 | (46) | 1.06 | (0.66-1.70) | 1.10 | (0.68-1.80) |

| 35–44 | 21 | (24) | 63 | (24) | 0.97 | (0.56-1.70) | 1.03 | (0.58-1.80) |

| ≥45 | 4 | (4) | 26 | (10) | 0.52 | (0.19-1.40) | 0.51 | (0.18-1.50) |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Single | 38 | (44) | 100 | (39) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Married | 30 | (34) | 121 | (47) | 0.72 | (0.47-1.10) | 0.76 | (0.49-1.20) |

| Separated/Widowed | 19 | (22) | 38 | (14) | 1.20 | (0.77-1.90) | 1.30 | (0.78-1.70) |

| Education level | ||||||||

| No formal education/Primary | 35 | (40) | 95 | (37) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Secondary | 38 | (44) | 123 | (47) | 0.88 | (0.59-1.3) | 0.86 | (0.59-1.30) |

| Tertiary | 14 | (16) | 41 | (16) | 0.95 | (0.55-1.6) | 1.01 | (0.59-1.70) |

| Sex work | ||||||||

| No | 80 | (56) | 232 | (90) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 7 | (44) | 27 | (10) | 0.80 | (0.40-1.60) | 0.58 | (0.29-1.20) |

| Co-morbidities | ||||||||

| No | 53 | (61) | 175 | (68) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 34 | (39) | 84 | (32) | 1.20 | (0.86-1.80) | 0.90 | (0.61-1.40) |

Table 3: Factors associated with stigma among mpox survivors, Kampala metropolitan Area, August 2024–January 2025

| Characteristics | Stigma n=49 (%) | No stigma n=100 (%) | cPR (95% CI) | aPR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 24 (39) | 37 (61) | Ref | Ref |

| Married | 10 (20) | 39 (80) | 0.52 (0.27–0.98) | 0.48 (0.26–0.87) |

| Separated/Widowed | 15 (38) | 24 (62) | 0.98 (0.59–1.62) | 1.02 (0.58–1.81) |

| Sex Work | ||||

| No | 42 (36) | 74 (64) | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 7 (21) | 26 (79) | 0.59 (0.29–1.20) | 0.53 (0.26–1.08) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–24 | 10 (29) | 25 (71) | Ref | Ref |

| 25–34 | 28 (39) | 44 (61) | 1.40 (0.75–2.50) | 1.50 (0.83–2.7) |

| 35–44 | 9 (27) | 25 (73) | 0.93 (0.43–2.00) | 1.10 (0.53–2.4) |

| ≥45 | 2 (25) | 6 (75) | 0.88 (0.24–3.30) | 1.10 (0.26–4.60) |

| Length of stay (days) | ||||

| 1–7 | 29 (28) | 75 (72) | Ref | Ref |

| 8–14 | 18 (44) | 23 (56) | 1.60 (0.99–2.50) | 1.60 (0.99–2.70) |

| >14 | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 1.80 (0.64–5.03) | 1.40 (0.58–3.40) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| No | 31 (30) | 71 (70) | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 18 (38) | 29 (62) | 1.30 (0.79–2.01) | 0.88 (0.54–1.50) |

| Education level | ||||

| No/Primary | 23 (35) | 42 (65) | Ref | Ref |

| Secondary | 19 (27) | 51 (73) | 0.77 (0.46–1.30) | 0.72 (0.45–1.20) |

| Tertiary | 7 (50) | 7 (50) | 1.41 (0.76–2.60) | 1.12 (0.58–2.10) |

Table 4: Factors associated with stigma among female survivors, Kampala Metropolitan Area, August 2024–January 2025

| Characteristics | Stigma n=38 (%) | No stigma n=159 (%) | cPR (95% CI) | aPR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length of stay (days) | ||||

| 1–7 | 19 (15) | 109 (85) | Ref | Ref |

| 8–14 | 11 (23) | 36 (77) | 1.60 (0.81–3.07) | 1.80 (0.85–3.70) |

| >14 | 8 (36) | 14 (64) | 2.40 (1.20–4.90) | 2.90 (1.30–6.50) |

| Sex work | ||||

| No | 38 (19) | 158 (81) | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | NA | NA |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–24 | 8 (23) | 27 (77) | Ref | Ref |

| 25–34 | 16 (18) | 74 (82) | 0.78 (0.37–1.70) | 0.81 (0.34–1.80) |

| 35–44 | 12 (24) | 38 (76) | 1.05 (0.48–2.30) | 0.97 (0.38–2.50) |

| ≥45 | 2 (9) | 20 (91) | 0.40 (0.09–1.20) | 0.28 (0.07–1.10) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| No | 22 (17) | 104 (83) | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 16 (22) | 55 (78) | 1.30 (0.73–2.30) | 0.82 (0.47–1.60) |

| Education level | ||||

| No/primary | 12 (18) | 53 (82) | Ref | Ref |

| Secondary | 19 (21) | 72 (79) | 1.10 (0.59–2.20) | 1.10 (0.58–2.01) |

| Tertiary | 7 (17) | 34 (83) | 0.92 (0.40–2.20) | 0.96 (0.44–2.30) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 14 (18) | 63 (82) | Ref | Ref |

| Married | 20 (20) | 82 (80) | 1.08 (0.58–2.00) | 1.10 (0.55–2.30) |

| Separated/Widowed | 4 (22) | 14 (78) | 1.20 (0.40–3.30) | 1.90 (0.64–5.70) |

Table 5: Factors associated with stigma among male survivors, Kampala Metropolitan Area,

August 2024–January 2025

Figures

Keywords

- Stigma

- Mpox

- Survivors

- Disease outbreaks

- Uganda

Joanita Nalwanga1,&, Richard Migisha1, Ivan Lukabwe1, Gidudu Samuel1, Benon Kwesiga1, Lilian Bulage1, Annet Mary Namusisi1, Emmanuel Okiror1, Prichard Kavuma2, Ruth Kaliisa2, Inyeong Park3, Dohoon Kim2, Alex Ndyabakira3, Dansan Atim4, Alex Riolexus Ario1

1Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program, Uganda National Institute of Public Health, Kampala, Uganda| 2Korea Foundation for International Healthcare, Kampala, Uganda| 3Directorate of Public Health and Environment, Kampala Capital City Authority, Kampala, Uganda| 4Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda

&Corresponding author: Joanita Nalwanga, Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program, Uganda National Institute of Public Health, Kampala, Uganda, Email: jnalwanga@uniph.go.ug ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-2216-3685

Received: 1 Dec 2025, Accepted: 08 Feb 2026, Published: 12 Feb 2026

Domain: Infectious Disease Epidemiology

Keywords: Stigma, Mpox, Survivors, Disease outbreaks, Uganda

©Joanita Nalwanga et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Joanita Nalwanga et al., Stigma and associated factors among mpox survivors in central Uganda, August 2024–January 2025. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2026; 9(1):27. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00308

Abstract

Introduction: In January 2025, Kampala Metropolitan Area (KMA) in central Uganda had approximately 60% of the national Mpox burden. In Mpox, like other similar infectious diseases, stigma can persist long after clinical recovery among survivors, leading to social isolation and psychological distress. We determined the prevalence of stigma and associated factors among Mpox survivors in KMA.

Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional study in February 2025 among laboratory-confirmed Mpox survivors in KMA, central Uganda. Eligible participants had been treated and discharged from the Mpox treatment unit during August 2024–January 2025. Data on demographics, Mpox-related characteristics, and stigma were collected using interviewer-administered questionnaires, including an Mpox stigma scale adapted from the HIV Berger Stigma Scale. Scores ≥30 were considered indicative of stigma. Modified Poisson regression was used to identify factors associated with stigma.

Results: We enrolled 346 Mpox survivors, of whom 197 (57%) were male. The median age was 30 years (IQR, 25-36). Most (66%) were hospitalised for 1–7 days. The prevalence of stigma was 25% (n=87, 95%CI: 21%–30%), with concerns about public attitude (46%) and disclosure concerns (45%) being the most common. Males had a lower prevalence of stigma compared to females (aPR=0.57, 95% CI: 0.39–0.84). Longer hospital stays were associated with increased stigma: 8–14 days (aPR=1.7, 95% CI: 1.1–2.5) and >14 days (aPR=2.5, 95% CI: 1.3–4.5). Among females, being married was associated with lower prevalence of stigma (aPR=0.48, 95% CI: 0.26–0.87). Among males, hospitalisation for >14 days (aPR=2.9, 95% CI: 1.3–6.5) was associated with increased prevalence of stigma.

Conclusion: Approximately one in four Mpox survivors experienced stigma, with a higher prevalence among females and those with prolonged hospitalisations. Marriage was protective among females, whereas prolonged hospitalisation was a key driver among males. The most common concerns were about disclosure and the public’s attitude towards Mpox. Efforts to reduce stigma could prioritize public education and provision of psychosocial support, especially for survivors with extended hospital stays. Gender-sensitive programs may address the unique stigma experiences of different sexes.

Keywords: Stigma, Mpox, Survivors, Disease outbreaks, Uganda

Introduction

Stigma is the negative association between a person or group of people who share certain characteristics and or a specific disease [1]. Stigma associated with infectious diseases has long been recognised as a major barrier to effective public health response and survivor wellbeing [2]. During infectious disease outbreaks, including Ebola and COVID-19, survivors often experience discrimination, social exclusion, and limited access to healthcare services [3,4,5]. These experiences compromise mental health and hinder reintegration into communities [2]. In the context of mpox, stigma has been driven by public anxiety, misinformation, particularly through media reporting and the presence of physically visible lesions that may leave permanent scars, provoking discriminatory attitudes [6]. Although mpox is endemic in some African regions, its spread in Western countries was linked to sexual behaviour among men who have sex with men, fueling stigma and discrimination [7, 8, 9].

Sub-Saharan Africa has repeatedly experienced stigma-prone outbreaks [10]. Uganda, in particular, has faced outbreaks such as Ebola and COVID-19, during which survivors reported widespread stigmatisation [3,11]. Additionally, during the Ebola epidemic, survivors were frequently subjected to community rejection, livelihood disruptions, and psychological distress [12]. In the same Ebola outbreak, Uganda implemented measures in partnership with organizations to support survivor reintegration through livelihood restoration, community sensitization, and psychosocial support [13,14]. While these approaches alleviated stigma for some, they inadvertently exacerbated it for others [3].

On July 24, 2024, Uganda confirmed its first cases of mpox and subsequently reported a steady increase in case numbers, hospital admissions, and recoveries over the study period [15]. By the end of January 2025, KMA, in central Uganda, had approximately 60% of the total national mpox burden [16, 17]. Understanding the dynamics and consequences of stigma among mpox survivors is critical for designing effective public health interventions and fostering supportive environments for affected individuals [2]. To inform Uganda’s mpox outbreak response and contribute to stigma-reduction strategies, we determined the prevalence and associated factors of stigma among survivors of mpox in KMA, the central region of the country.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a cross-sectional study among mpox survivors who were diagnosed and discharged from the mpox treatment unit in KMA from August 2024 to January 2025. By the end of January 2025, Uganda had close to 2,500 mpox cases and 16 deaths [16]. We selected KMA because it contributed approximately 60% of the national caseload [17]. KMA is Uganda’s central and most populous urban zone, made up of Kampala City, Wakiso, and Mukono Districts [18]. Kampala City hosts approximately 1.7 million residents, but its daytime population exceeds 2.5 million due to commuting. Wakiso District, with about 3.4 million people, is Uganda’s most populous and fastest-growing district. Mukono has a population of roughly 929,000 people and presents a mix of urban and rural characteristics [19]. KMA is Uganda’s urban and economic hub, but grapples with challenges such as unregulated urban growth, high infectious disease risk, and unequal access to healthcare [18, 20].

Study population

We calculated the sample size using the Kish Leslie formula (1965), at a 95% confidence level and a prevalence of 50% due to the absence of previous data on mpox stigma in Uganda:

\[

n = \frac{Z^2 \times P \times (1 – P)}{d^2}

\]

where: n=sample size, Z= Z-score for 95% confidence (1.96), P= estimated prevalence (0.5), d = margin of error (0.05), giving 384 participants. To account for a potential 10% non-response rate, the sample size was adjusted using the formula:

Final adjusted sample size

\[

n_{\text{adj}} = \frac{n}{1 – \text{non-response rate}}

\]

The final calculated sample size was 427 participants.

From the discharge register at the mpox treatment unit, we included adult (≥18years) mpox survivors and residents of KMA who had previously been diagnosed, treated, and had no known history of mental illness. Individuals with mental illness may have an altered capacity to accurately reflect on and report internal experiences, which could bias or misrepresent stigma levels in the study [21]. We excluded those who had incomplete or missing phone contact information. We used stratified random sampling to ensure proportional representation of mpox survivors from the three districts in KMA (Kampala, Wakiso, and Mukono). We enlisted eligible mpox survivors from the discharge register and made district-specific lists as sampling frames. We randomly and proportionately selected participants from each list. All participants provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Data collection and study variables

Data were collected during February 2025 by a trained study team of public health officers. Using contact information from the treatment unit registers and with the help of the village health team, the study team traced and visited participants at their homes or workplaces, where they administered a structured questionnaire in a private setting.

The data tool contained sociodemographic characteristics, mpox-related questions and a 24-item stigma scale. The primary outcome variable was stigma among mpox survivors, defined as self-reported experiences of discrimination, social rejection, or reduced opportunities following illness. For analysis, stigma was categorised as present or absent. The independent variables included a range of sociodemographic, clinical, and stigma-related questions. Sociodemographic variables were age, sex, marital status, highest level of education attained, occupation, and place of residence. Age was grouped into 18–24, 25–34, 35–44, and ≥45 years by collapsing the standard 5-year age bands used in the Uganda Demographic and Health Survey [22]. Clinical variables included length of hospital stay and comorbidities, defined as any chronic or pre-existing condition in addition to mpox. These included self-reported or clinically documented conditions such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, HIV infection, tuberculosis, and other long-term illnesses.

We adapted an mpox stigma scale previously used during the survey of pain and stigma experiences in Baltimore during the 2022 mpox outbreak [23]. This tool was based on the validated and abbreviated HIV Berger Stigma Scale, encompassing four domains: personalised stigma, disclosure concerns, negative self-image, and public attitudes [24, 25]. To ensure cultural relevance and applicability to mpox survivors rather than those with active disease, four items were removed, including statements related to sexual orientation, LGBTQ community perceptions, the stigmatizing nature of the term “monkeypox,” and efforts to conceal infection.

Data management and analysis

Descriptive analysis was done for socio-demographic characteristics using STATA version 17.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA) and presented in frequency tables. To assess the potential impact of participant withdrawal on the study findings, we compared the demographic characteristics of participants who withdrew with those who completed the study. Descriptive analyses were conducted for age, sex, and duration of hospitalization to evaluate whether important differences existed between the two groups using the Chi-square (χ²) test. Responses to stigma questions were scored 2 for “strongly agree” and “agree” responses and 1 for “disagree” and “strongly disagree”. With a maximum score of 40 and a minimum of 20, stigma was measured on a scale ranging from 20 to 40. To create a binary variable, we used a cut-off score of 30, the midpoint of the possible range. Scores ≥30 were categorized as ‘stigma: Yes’ (indicating presence of stigma), and scores <30 as ‘Stigma: No’ (indicating absence of stigma). Modified Poisson regression was performed to determine factors associated with stigma.

To assess potential effect modification by sex, we stratified the dataset by sex and conducted separate modified Poisson regression models for male and female participants. Within each stratum, we estimated adjusted prevalence ratios (aPR) and 95% confidence intervals for the association between predictor variables and stigma. The same set of covariates were included in both male and female-specific models to allow comparability. Stratified estimates were then examined to identify differences in the magnitude or direction of associations between the two groups.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was in response to a public health emergency and was therefore determined to be non-research. The Ministry of Health (MoH) gave permission to conduct the study. In agreement with the International Guidelines for Ethical Review of Epidemiological Studies by the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (1991) and the Office of the Associate Director for Science, US CDC/Uganda, it was determined that this activity was not human subject research and that its primary intent was public health practice or disease control activity (specifically, epidemic or endemic disease control activity). This activity was reviewed by the US CDC and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy. §§See, e.g., 45 C.F.R. part 46, 21 C.F.R. part 56; 42 U.S.C. §241(d); 5 U.S.C. §552a; 44 U.S.C. §3501 et seq. All experimental protocols were approved by the US CDC human subjects review board (The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Institutional Review Board) and were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Permission to conduct the study was also granted by the districts’ health offices. We obtained informed consent from all the participants who were aged 18 years or older (legal age in Uganda). Verbal consent was sought for timely data collection to inform public health action and minimize physical contact to prevent possible spread of mpox and other infectious diseases to the study participants and the investigating team. The investigators informed participants about the aim of the study and that their participation was voluntary, free to withdraw from the study at any time without giving a reason. All the information provided was handled confidentially. We did not collect any personal identifying information. We stored the data in a password-protected computer and only shared it with the investigation team.

Results

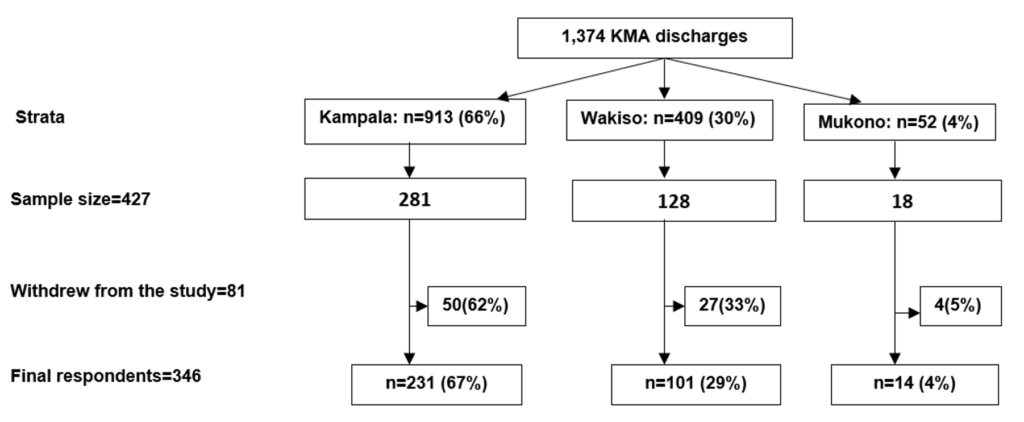

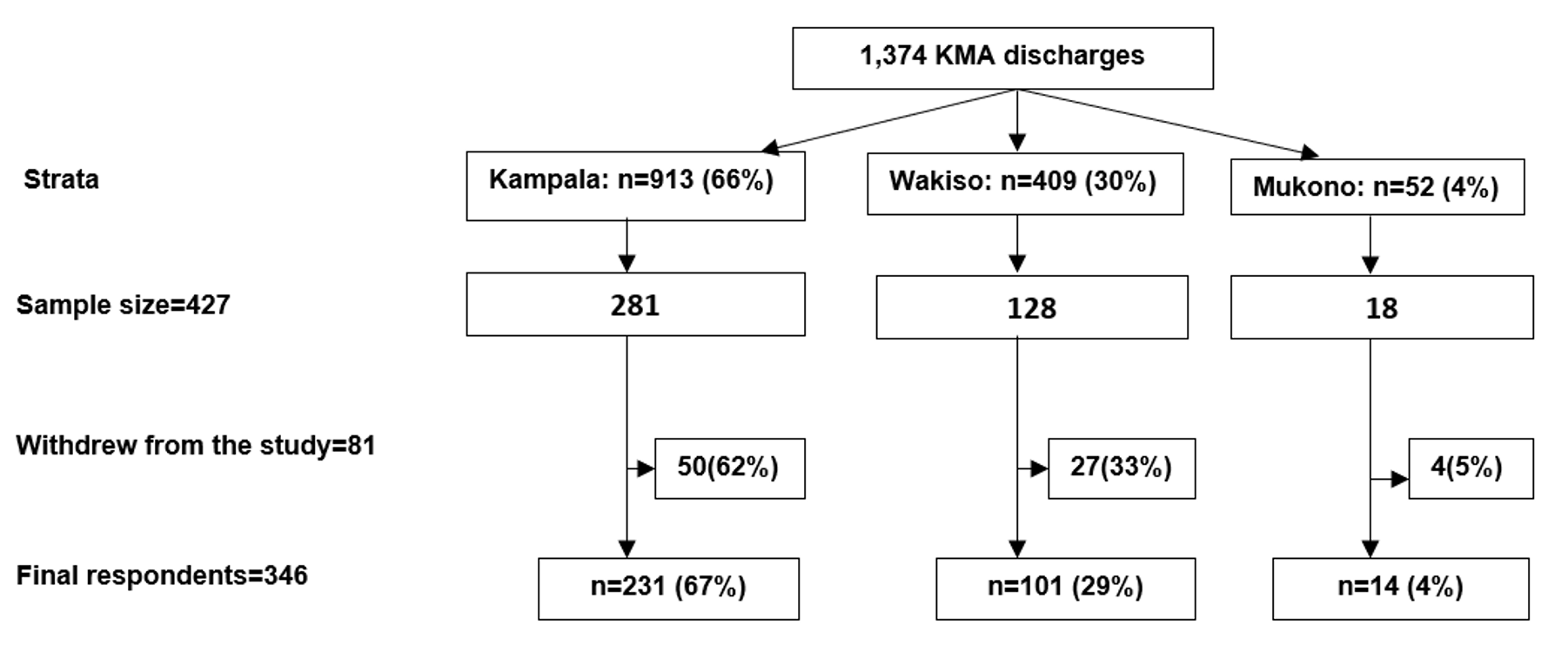

A total of 427 mpox survivors were selected from the treatment unit discharge list. Forty-seven were excluded due to incomplete contact information and replaced to maintain the sample size. Of the eligible participants, 81 (19%) withdrew, leaving 346 who completed the study (81% response rate). Participants were predominantly from Kampala (67%), followed by Wakiso (29%) and Mukono (4%) (Figure 1). Those who withdrew were demographically similar to those who completed the study (Table 1).

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of study participants

The median age for the participants was 30 years (IQR= 25–36). Among the 346 participants, 197 (57%) were males. Most (44%) of the participants were married, 46% had attained secondary education, and 10% identified as sex workers. The majority (66%) had spent 1-7 days admitted to the isolation facility. Most (66%) reported absence of comorbidities (Table 2).

Prevalence of stigma among study participants

Overall, 87 participants met the predefined threshold for stigma according to the study criteria, corresponding to a prevalence of 25% (95% CI: 21%-30%). Most participants reported concerns about public attitudes (n=158; 46%) and disclosure concerns (n=156; 45%) (Figure 2).

Factors associated with stigma among study participants

Males had a lower prevalence of stigma compared to females (aPR=0.57, 95% CI: 0.39–0.84). The prevalence of stigma increased with prolonged hospital stay: 8-14 days (aPR=1.7, 95% CI: 1.10–2.50) and >14 days (aPR=2.5, 95% CI: 1.3–4.5). The rest of the other factors were not statistically significant (Table 3).

Adjusted prevalence ratios for stigma among female mpox survivors

Among females, being married was significantly associated with lower prevalence of stigma (aPR=0.48, 95% CI: 0.26–0.87) (Table 4).

Adjusted prevalence ratios for stigma among male mpox survivors

Among males, staying in hospital for more than 14 days was significantly associated with a higher prevalence of stigma (aPR=2.9, 95% CI: 1.3–6.5). There was no significant association between stigma and other variables (Table 5).

Discussion

This study assessed significant stigma, as defined by a predefined threshold and its associated factors, among mpox survivors in central Uganda. Overall, one in four survivors experienced stigma, primarily driven by external negative public attitudes. Female survivors and those with prolonged hospital stays were more likely to report stigma. Stratified analysis revealed marital status as a determinant for stigma among females, and length of stay was found to be a strong determinant among males.

The prevalence of stigma among mpox survivors in our study was substantial implying that stigma remains a significant consequence of infectious disease outbreaks even after clinical recovery. This aligns with evidence from other settings. In Nigeria, nearly half of mpox survivors reported stigma-related experiences such as social exclusion and discrimination following the 2017–2018 outbreak [26]. Similarly, during the 2022 mpox outbreak, survey data from the United States revealed that individuals with confirmed mpox infection perceived some levels of stigma [23]. These findings demonstrate that stigma is not only common among mpox survivors but may also persist for an unknown duration beyond illness recovery. To our knowledge, this is the first study assessing stigma specifically among mpox survivors in Uganda. Previous studies on disease outbreaks in the country, including Ebola virus disease and COVID-19, have similarly highlighted stigma experiences among survivors [3, 27]. This underscores the importance of integrating stigma mitigation strategies into outbreak response efforts to improve the well-being of both individuals with active disease and survivors [8, 28].

The most commonly reported concerns among survivors related to negative public attitudes, including being treated as outcasts and experiencing impacts on employment. This aligns with other studies in which survivors reported rejection and discrimination by those around them [29, 30]. These experiences also reflect findings from previous research showing that visible symptoms, fear of contagion, and misinformation contribute to public stigma and social exclusion [4, 7, 31]. Such experiences can hinder recovery and community reintegration of survivors [29, 32]. Consequently, public health interventions could address both individual support and community-level education to dispel myths, reduce prejudice, and foster inclusive attitudes [4].

Our study revealed that females experienced a higher prevalence of stigma compared to males. This finding aligns with evidence from previous research showing that gender significantly influences the perception and experience of stigma in health-related contexts. Women often bear a disproportionate burden of social consequences following illness due to pre-existing gender inequities, cultural norms, and caregiving expectations within households and communities [33, 34]. In outbreaks of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases, gender experiences of stigma have been consistently documented. For example, studies conducted during the Ebola virus disease epidemics in West Africa and the Democratic Republic of Congo demonstrated that women were more likely to be stigmatized, often due to their central role as caregivers, which increased their exposure and community suspicion [35, 36]. Similarly, during the COVID-19 pandemic, women frequently reported greater psychosocial distress and stigmatization, compounded by social roles and economic vulnerabilities [37, 38].

Several mechanisms may explain the higher stigma observed among females in our study. First, women in many African settings face entrenched cultural stereotypes that exacerbate discrimination when they are associated with infectious diseases [39]. Second, economic dependence and lower decision-making power can limit their ability to resist or cope with stigmatizing behaviors [40]. Third, women may also be more visible in health-care seeking and isolation facilities, which can inadvertently expose them to labeling within their communities [41].

Hospitalization has been shown to increase vulnerability to stigma across various infectious diseases. Prolonged hospital stays may be interpreted as markers of disease severity or infectiousness, amplifying fear and discrimination within communities [42, 43]. These interpretations are supported by studies from the COVID-19 and Ebola outbreaks, which demonstrated that longer duration of quarantine or hospitalization was strongly associated with stigma and social rejection [3, 29, 37, 44].

Stratified analysis revealed important sex-specific patterns. Among females, being married was protective against stigma, while among males, prolonged hospitalization was the strongest predictor. These differential predictors suggest effect modification by sex, which is consistent with literature indicating that men and women experience stigma differently due to gender norms, roles, and social expectations [45, 46].

Among women only, marriage appeared to buffer stigma likely due to increased social support and perceived social legitimacy. Similar findings have been observed in HIV and mental health research, where married individuals often reported lower levels of perceived stigma due to familial and community acceptance [5, 47]. This protective effect may reflect Uganda’s sociocultural context, in which marital status can shape how health conditions are interpreted and socially responded to [48].

In contrast, among men, extended hospitalization was associated with stigma. This may be due to the complex interplay between gender roles, illness experience, and societal expectations that men remain strong and self-reliant. In the Ugandan context, cultural expectations often dictate that men embody resilience and self-reliance, and an extended period of illness may contradict these norms, thereby exposing them to judgment and stigmatization [49, 50]. In our study, it is plausible that longer hospitalization among men amplified visibility of their illness, reinforcing perceptions of weakness or contagion, which in turn heightened experiences of stigma. Similar findings have been described among people living with HIV, where men undergoing repeated or prolonged treatment encounters reported intensified stigma compared to their female counterparts [42]. The sex differences in stigma experiences imply the incorporation of a gendered approach to stigma.

Implications of the study

Our findings have practical implications for outbreak response. Interventions targeting stigma reduction should prioritise psychosocial support for men with prolonged hospital stays, particularly addressing cultural narratives that associate illness with diminished masculinity. Moreover, integrating stigma screening into hospital discharge planning may help identify at-risk groups early and link them to community reintegration programs. By acknowledging sex as an important determinant of stigma, public health responses can become more responsive and equitable in supporting survivors of emerging infectious diseases. Further studies could assess the trajectory of stigma over time through longitudinal follow-up of survivors, and to explore how prolonged hospitalization mediates stigma among men. Validation of brief stigma measurement tools tailored to the Ugandan context could strengthen monitoring and ensure stigma is tracked as a routine program indicator. Such evidence would inform sustainable stigma-mitigation policies that support equitable access to care and survivor wellbeing.

Study limitations

One of the main limitations was reliance on participants’ self-reports, which may have brought about information bias where participants may underreport their negative experiences and give information that does not accurately reflect their true feelings. To mitigate this, we ensured confidentiality and privacy during interviews and trained data collectors to create a safe, nonjudgmental environment. The exclusion of individuals with a history of mental illness and those with incomplete or missing phone contact information may have affected the study findings, as these groups may also experience stigma, potentially leading to an underestimation of the prevalence and associated factors for stigma. These exclusions were necessary to ensure reliable self-reporting and completeness of data. By applying these criteria consistently, the study minimised information bias and enhanced internal validity, allowing robust estimation of factors associated with stigma among clinically stable mpox survivors.

Conclusion

Approximately one in four Mpox survivors experienced stigma, with higher prevalence among females and those with prolonged hospitalization. Stratified analysis revealed distinct gendered patterns: marriage was protective against stigma among females, whereas prolonged hospitalization was a key driver among males. Survivors also reported significant concerns about disclosure and negative public attitudes toward Mpox. These findings highlight the need for psychosocial support and community-based stigma reduction strategies during and after recovery. Further studies are recommended to evaluate the long-term impact of stigma among survivors.

What is already known about the topic

- Stigma affects health seeking behavior and adherence to care among sufferers and survivors of infectious diseases

- Limited evidence exists on the burden and determinants of stigma among mpox survivors, especially in sub-Saharan Africa.

- Previous studies on stigma have focused mainly on HIV, tuberculosis and Ebola, mpox-related stigma remains poorly documented and inadequately addressed.

What this study adds

- Provides the first quantitative study on stigma levels among mpox survivors in central Uganda.

- Identifies key determinants of stigma including sex, severity of illness, prolonged hospitalization and community perceptions that can inform interventions.

- Highlights gender variations in stigma showing that females experience higher stigma than males.

- Generates evidence to guide integration of psychosocial support into mpox case management and post-recovery follow-up programs.

Funding

This study was supported by Korea Foundation for International Healthcare (KOFIH) under the project titled ‘Strengthening Health System to Prevent, Detect, and Respond to infectious Diseases in Uganda’. Implemented in collaboration with the Uganda National Institute of Public Health (UNIPH) and the Ministry of Health.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the participants in Kampala, Wakiso, and Mukono Districts, who generously shared their time and experiences for this study. We also extend our appreciation to the Entebbe Treatment and Isolation Unit staff, the district surveillance focal persons and village health teams in the study districts, who supported recruitment of mpox survivors. Special thanks to the Uganda National Institute of Public Health and Korea Foundation for International Healthcare staff for their guidance and support throughout the project.

Authors´ contributions

JN conceptualized the study idea, collected data, analyzed it, and wrote the manuscript. AMN, EOO and EM supported in conceptualizing the study and reviewing the manuscript. RM, IL, GS, AN, LB, BK, CM, PK, RK, IP, DK, AN, DA and ARA supported in editing and reviewing of the manuscript to ensure scientific rigor and integrity. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

| Characteristic | Completed n=346 (%) | Withdrawn n=81 (%) | χ² | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 2.17 | 0.54 | ||

| 18–24 | 70 (20) | 20 (25) | ||

| 25–34 | 162 (47) | 35 (43) | ||

| 35–44 | 84 (24) | 18 (22) | ||

| ≥45 | 30 (9) | 8 (10) | ||

| Sex | 0.12 | 0.73 | ||

| Female | 149 (43) | 33 (41) | ||

| Male | 197 (57) | 48 (59) | ||

| Hospital stay (days) | 0.66 | 0.72 | ||

| 1–7 | 232 (67) | 51 (63) | ||

| 8–14 | 88 (25) | 21 (26) | ||

| >14 | 26 (8) | 9 (11) |

| Characteristics (n=346) | Frequency | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–24 | 70 | (20) |

| 25–34 | 162 | (47) |

| 35–44 | 84 | (24) |

| ≥45 | 30 | (9) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 149 | (43) |

| Male | 197 | (57) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 138 | (40) |

| Married | 151 | (44) |

| Separated/Widowed | 57 | (16) |

| Education | ||

| No formal education/Primary | 130 | (38) |

| Secondary | 161 | (46) |

| Tertiary | 55 | (16) |

| Sex work | ||

| No | 312 | (90) |

| Yes | 34 | (10) |

| Hospital stay (days) | ||

| 1–7 | 232 | (67) |

| 8–14 | 88 | (25) |

| >14 | 26 | (8) |

| Co-morbidities | ||

| No | 228 | (66) |

| Yes | 118 | (34) |

| Characteristics | Stigma (n=87) | (%) | No stigma (n=259) | (%) | cPR | (95%CI) | aPR | (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 49 | (56) | 100 | (39) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Male | 38 | (44) | 159 | (61) | 0.59 | (0.41-0.85) | 0.57 | (0.39-0.84) |

| Hospital stay (days) | ||||||||

| 1–7 | 48 | (55) | 184 | (71) | Ref | Ref | ||

| 8–14 | 29 | (33) | 59 | (23) | 1.60 | (1.10-2.40) | 1.70 | (1.10-2.50) |

| >14 | 10 | (12) | 16 | (6) | 1.90 | (1.07-3.20) | 2.50 | (1.30-4.50) |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| 18–24 | 18 | (21) | 52 | (20) | Ref | Ref | ||

| 25–34 | 44 | (51) | 118 | (46) | 1.06 | (0.66-1.70) | 1.10 | (0.68-1.80) |

| 35–44 | 21 | (24) | 63 | (24) | 0.97 | (0.56-1.70) | 1.03 | (0.58-1.80) |

| ≥45 | 4 | (4) | 26 | (10) | 0.52 | (0.19-1.40) | 0.51 | (0.18-1.50) |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Single | 38 | (44) | 100 | (39) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Married | 30 | (34) | 121 | (47) | 0.72 | (0.47-1.10) | 0.76 | (0.49-1.20) |

| Separated/Widowed | 19 | (22) | 38 | (14) | 1.20 | (0.77-1.90) | 1.30 | (0.78-1.70) |

| Education | ||||||||

| No formal education/Primary | 35 | (40) | 95 | (37) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Secondary | 38 | (44) | 123 | (47) | 0.88 | (0.59-1.3) | 0.86 | (0.59-1.30) |

| Tertiary | 14 | (16) | 41 | (16) | 0.95 | (0.55-1.6) | 1.01 | (0.59-1.70) |

| Sex work | ||||||||

| No | 80 | (56) | 232 | (90) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 7 | (44) | 27 | (10) | 0.80 | (0.40-1.60) | 0.58 | (0.29-1.20) |

| Co-morbidities | ||||||||

| No | 53 | (61) | 175 | (68) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 34 | (39) | 84 | (32) | 1.20 | (0.86-1.80) | 0.90 | (0.61-1.40) |

| Characteristics | Stigma n=49 (%) | No stigma n=100 (%) | cPR (95% CI) | aPR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 24 (39) | 37 (61) | Ref | Ref |

| Married | 10 (20) | 39 (80) | 0.52 (0.27–0.98) | 0.48 (0.26–0.87) |

| Separated/Widowed | 15 (38) | 24 (62) | 0.98 (0.59–1.62) | 1.02 (0.58–1.81) |

| Sex Work | ||||

| No | 42 (36) | 74 (64) | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 7 (21) | 26 (79) | 0.59 (0.29–1.20) | 0.53 (0.26–1.08) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–24 | 10 (29) | 25 (71) | Ref | Ref |

| 25–34 | 28 (39) | 44 (61) | 1.40 (0.75–2.50) | 1.50 (0.83–2.7) |

| 35–44 | 9 (27) | 25 (73) | 0.93 (0.43–2.00) | 1.10 (0.53–2.4) |

| ≥45 | 2 (25) | 6 (75) | 0.88 (0.24–3.30) | 1.10 (0.26–4.60) |

| Length of stay (days) | ||||

| 1–7 | 29 (28) | 75 (72) | Ref | Ref |

| 8–14 | 18 (44) | 23 (56) | 1.60 (0.99–2.50) | 1.60 (0.99–2.70) |

| >14 | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 1.80 (0.64–5.03) | 1.40 (0.58–3.40) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| No | 31 (30) | 71 (70) | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 18 (38) | 29 (62) | 1.30 (0.79–2.01) | 0.88 (0.54–1.50) |

| Education level | ||||

| No/Primary | 23 (35) | 42 (65) | Ref | Ref |

| Secondary | 19 (27) | 51 (73) | 0.77 (0.46–1.30) | 0.72 (0.45–1.20) |

| Tertiary | 7 (50) | 7 (50) | 1.41 (0.76–2.60) | 1.12 (0.58–2.10) |

| Characteristics | Stigma n=38 (%) | No stigma n=159 (%) | cPR (95% CI) | aPR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length of stay (days) | ||||

| 1–7 | 19 (15) | 109 (85) | Ref | Ref |

| 8–14 | 11 (23) | 36 (77) | 1.60 (0.81–3.07) | 1.80 (0.85–3.70) |

| >14 | 8 (36) | 14 (64) | 2.40 (1.20–4.90) | 2.90 (1.30–6.50) |

| Sex work | ||||

| No | 38 (19) | 158 (81) | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | NA | NA |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–24 | 8 (23) | 27 (77) | Ref | Ref |

| 25–34 | 16 (18) | 74 (82) | 0.78 (0.37–1.70) | 0.81 (0.34–1.80) |

| 35–44 | 12 (24) | 38 (76) | 1.05 (0.48–2.30) | 0.97 (0.38–2.50) |

| ≥45 | 2 (9) | 20 (91) | 0.40 (0.09–1.20) | 0.28 (0.07–1.10) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| No | 22 (17) | 104 (83) | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 16 (22) | 55 (78) | 1.30 (0.73–2.30) | 0.82 (0.47–1.60) |

| Education level | ||||

| No/primary | 12 (18) | 53 (82) | Ref | Ref |

| Secondary | 19 (21) | 72 (79) | 1.10 (0.59–2.20) | 1.10 (0.58–2.01) |

| Tertiary | 7 (17) | 34 (83) | 0.92 (0.40–2.20) | 0.96 (0.44–2.30) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 14 (18) | 63 (82) | Ref | Ref |

| Married | 20 (20) | 82 (80) | 1.08 (0.58–2.00) | 1.10 (0.55–2.30) |

| Separated/Widowed | 4 (22) | 14 (78) | 1.20 (0.40–3.30) | 1.90 (0.64–5.70) |

References

- World Health Organization. A guide to preventing and addressing social stigma associated with COVID-19 [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2020 Feb 24 [cited 2026 Feb 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/a-guide-to-preventing-and-addressing-social-stigma-associated-with-covid-19

- Fischer LS, Mansergh G, Lynch J, Santibanez S. Addressing Disease-Related Stigma During Infectious Disease Outbreaks. Disaster Med Public Health Prep [Internet]. 2019 Jun 3 [cited 2026 Feb 12];13(5-6):989-94. doi:10.1017/dmp.2018.157 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2018.157

- Zalwango GM, Paige S, Migisha R, Nakafeero Simbwa B, Nsubuga EJ, Asio A, Kabami Z, Zalwango JF, Kawungezi PC, Wanyana MW, King P, Naiga HN, Agaba B, Zavuga R, Earle-Richardson G, Kwesiga B, Bulage L, Kadobera D, Ario AR, Harris JR. Stigma among Ebola Disease Survivors in Mubende and Kassanda districts, Central Uganda, 2022 [Internet]. medRxiv [preprint]. 2024 May 8 [cited 2026 Feb 12]. doi:10.1101/2024.05.07.24307005 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.07.24307005

- SeyedAlinaghi S, Afsahi AM, Shahidi R, Afzalian A, Mirzapour P, Eslami M, Ahmadi S, Matini P, Yarmohammadi S, Saeed Tamehri Zadeh S, Asili P, Paranjkhoo P, Ramezani M, Nooralioghli Parikhani S, Sanaati F, Amiri Fard I, Emamgholizade Baboli E, Mansouri S, Pashaei A, Mehraeen E, Hackett D. Social stigma during COVID-19: A systematic review. SAGE Open Med [Internet]. 2023 Nov 10 [cited 2026 Feb 12];11:20503121231208273. doi:10.1177/20503121231208273 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/20503121231208273

- Charles B, Jeyaseelan L, Pandian AK, Sam AE, Thenmozhi M, Jayaseelan V. Association between stigma, depression and quality of life of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHA) in South India – a community based cross sectional study. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2012 Jun 21 [cited 2026 Feb 12];12(1):463. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-463 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-463

- El Dine FB, Gebreal A, Samhouri D, Estifanos H, Kourampi I, Abdelrhem H, Mostafa HA, Elshaar AG, Suvvari TK, Ghazy RM. Ethical considerations during Mpox Outbreak: a scoping review. BMC Med Ethics [Internet]. 2024 Jul 22 [cited 2026 Feb 12];25(1):79. doi:10.1186/s12910-024-01078-0 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-024-01078-0

- Zimmermann HML, Gültzow T, Marcos TA, Wang H, Jonas Kai J, Stutterheim SE. Mpox stigma among men who have sex with men in the Netherlands: Underlying beliefs and comparisons across other commonly stigmatized infections. J Med Virol [Internet]. 2023 Sep 26 [cited 2026 Feb 12];95(9):e29091. doi:10.1002/jmv.29091 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.29091

- Norberg AN, Norberg PRBM, Manhães FC, Filho RMF, Souza DGD, Queiroz MMDC, Neto CHG, Ribeiro PC, Boechat JCDS, Viana KS, Silva MTRD. Public Health Strategies Against Social Stigma in the Mpox Outbreak: A Systematic Review. JAMMR [Internet]. 2024 Feb 10 [cited 2026 Feb 12];36(2):33-47. doi:10.9734/jammr/2024/v36i25365 Available from: https://doi.org/10.9734/jammr/2024/v36i25365

- World Health Organization. Mpox [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2024 Aug 26 [cited 2026 Feb 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mpox

- Omosigho PO, John OO, Musa MB, Aboelhassan YMEI, Olabode ON, Bouaddi O, Mengesha DT, Micheal AS, Modber MAKA, Sow AU, Kheir SGM, Shomuyiwa DO, Adebimpe OT, Manirambona E, Lucero-Prisno DE. Stigma and infectious diseases in Africa: examining impact and strategies for reduction. Ann Med Surg (Lond) [Internet]. 2023 Nov 1 [cited 2026 Feb 12];85(12):6078-82. doi:10.1097/MS9.0000000000001470 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/MS9.0000000000001470

- Amir K. COVID-19 and its related stigma: A qualitative study among survivors in Kampala, Uganda. Stigma Health [Internet]. 2021 Aug [cited 2026 Feb 12];6(3):272-6. doi:10.1037/sah0000325 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000325

- Rutakumwa R, Ninsiima S, Settuba E, Kyohangirwe L, Mpango RS, Tusiime C, Turyahabwa J, Knizek BL, Kaleebu P, Nyirenda M, Sentongo H, Kalani K, Kinyanda E. A qualitative study of Ebola survivors’ psychological experiences of evacuation, treatment and community reintegration: Lessons in holistic person-centred care from the 2022 outbreak in Uganda. PLOS Ment Health [Internet]. 2025 Jun 23 [cited 2026 Feb 12];2(6):e0000316. doi:10.1371/journal.pmen.0000316 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmen.0000316

- USAID. Restoring Hope and Dignity of Ebola Survivors in Uganda [Internet]. Washington (D.C.): USAID; 2023 [cited 2026 Feb 12]. Available from: https://medium.com/usaid-2030/restoring-the-hope-and-dignity-of-ebola-survivors-in-uganda-41cd96844eca

- World Health Organization. Fighting Ebola in the line of duty [Internet]. Kampala (Uganda): WHO Uganda; 2024 Jul 9 [cited 2026 Feb 12]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/countries/uganda/news/fighting-ebola-line-duty

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Uganda Mpox Situation report #002 [Internet]. Brazzaville (Congo): WHO AFRO; 2024 Sep 2 [cited 2026 Feb 12]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/countries/uganda/publication/uganda-mpox-situation-report-002

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Mpox Outbreak in Uganda Situation Update – 28 January 2025 [Internet]. Brazzaville (Congo): WHO AFRO; 2025 Jan 28 [cited 2026 Feb 12]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/countries/uganda/publication/mpox-outbreak-uganda-situation-update-28-january-2025

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Mpox Outbreak in Uganda Situation Update – 27 January 2025 [Internet]. Brazzaville (Congo): WHO AFRO; 2025 Jan 27 [cited 2026 Feb 12]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/countries/uganda/publication/mpox-outbreak-uganda-situation-update-27-january-2025

- Office of the President (Uganda). Ministry of Kampala Capital City and Metropolitan Affairs [Internet]. Kampala (Uganda): Office of the President (Uganda); c2026 [cited 2026 Feb 12]. Available from: https://op.go.ug/departments/ministry-kampala-capital-city-and-metropolitan-affairs

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics. National Population and housing census 2024 FINAL REPORT [Internet]. Kampala (Uganda): UBOS; 2024 Dec [cited 2026 Feb 12]. Available from: https://www.ubos.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/National-Population-and-Housing-Census-2024-Final-Report-Volume-1-Main.pdf

- UN-HABITAT. Uganda [Internet]. Nairobi (Kenya): UN-HABITAT; c2026 [cited 2026 Feb 12]. Available from: https://unhabitat.org/uganda

- Agnoli S, Zuberer A, Nanni-Zepeda M, McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Esterman M, DeGutis J. Depressive Symptoms are Associated with More Negative Global Metacognitive Biases in Combat Veterans, and Biases Covary with Symptom Changes over Time. Depress Anxiety [Internet]. 2023 Apr 17 [cited 2026 Feb 12];2023:1-13. doi:10.1155/2023/2925551 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/2925551

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2022 Main Report [Internet]. Kampala (Uganda): UBOS; 2023 Nov [cited 2026 Feb 12]. Available from: https://www.ubos.org/uganda-demographic-and-health-survey-2022-main-report/

- Schmalzle SA, Grant M, Lovelace S, Jung J, Choate C, Guerin J, Weinstein W, Taylor G. Survey of pain and stigma experiences in people diagnosed with mpox in Baltimore, Maryland during 2022 global outbreak. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2024 May 21 [cited 2026 Feb 12];19(5):e0299587. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0299587 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0299587

- Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: Psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health [Internet]. 2001 Nov 26 [cited 2026 Feb 12];24(6):518-29. doi:10.1002/nur.10011 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.10011

- Reinius M, Wettergren L, Wiklander M, Svedhem V, Ekström AM, Eriksson LE. Development of a 12-item short version of the HIV stigma scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes [Internet]. 2017 May 30 [cited 2026 Feb 12];15(1):115. doi:10.1186/s12955-017-0691-z Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0691-z

- Yinka-Ogunleye A, Aruna O, Dalhat M, Ogoina D, McCollum A, Disu Y, Mamadu I, Akinpelu A, Ahmad A, Burga J, Ndoreraho A, Nkunzimana E, Manneh L, Mohammed A, Adeoye O, Tom-Aba D, Silenou B, Ipadeola O, Saleh M, Adeyemo A, Nwadiutor I, Aworabhi N, Uke P, John D, Wakama P, Reynolds M, Mauldin MR, Doty J, Wilkins K, Musa J, Khalakdina A, Adedeji A, Mba N, Ojo O, Krause G, Ihekweazu C, Mandra A, Davidson W, Olson V, Li Y, Radford K, Zhao H, Townsend M, Burgado J, Satheshkumar PS. Outbreak of human monkeypox in Nigeria in 2017–18: a clinical and epidemiological report. Lancet Infect Dis [Internet]. 2019 Jul 5 [cited 2026 Feb 12];19(8):872-9. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30294-4 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30294-4

- Asio A, Massanja V, Kadobera D, Kwesiga B, Bulage L, Ario RA. Covid-19 related stigma among survivors in Soroti District, Uganda, March 2020 to December 2021 [Internet]. Kampala (Uganda): UNIPH; 2023 Apr 27 [cited 2026 Feb 12]. Available from: https://uniph.go.ug/covid-19-related-stigma-among-survivors-in-soroti-district-uganda-march-2020-to-december-2021/

- Humphreys G. Mpox and stigma. Bull World Health Organ [Internet]. 2024 Dec 1 [cited 2026 Feb 12];102(12):848-9. doi:10.2471/BLT.24.021224 Available from: https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.24.021224

- Overholt L, Wohl DA, Fischer WA, Westreich D, Tozay S, Reeves E, Pewu K, Adjasso D, Hoover D, Merenbloom C, Johnson H, Williams G, Conneh T, Diggs J, Buller A, McMillian D, Hawks D, Dube K, Brown J. Stigma and Ebola survivorship in Liberia: Results from a longitudinal cohort study. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2018 Nov 28 [cited 2026 Feb 12];13(11):e0206595. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0206595 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0206595

- Nanyonga M, Saidu J, Ramsay A, Shindo N, Bausch DG. Sequelae of Ebola Virus Disease, Kenema District, Sierra Leone. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2015 Dec 9 [cited 2026 Feb 12];62(1):125-6. doi:10.1093/cid/civ795 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ795

- Amzat J, Kanmodi KK, Aminu K, Egbedina EA. School‐based interventions on Mpox: A scoping review. Health Sci Rep [Internet]. 2023 Jun 12 [cited 2026 Feb 12];6(6):e1334. doi:10.1002/hsr2.1334 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.1334

- März JW, Holm S, Biller-Andorno N. Monkeypox, stigma and public health. Lancet Reg Health Eur [Internet]. 2022 Oct 30 [cited 2026 Feb 12];23:100536. doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100536 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100536

- Morgan R, Baker P, Griffith DM, Klein SL, Logie CH, Mwiine AA, Scheim AI, Shapiro JR, Smith J, Wenham C, White A. Beyond a Zero-Sum Game: How Does the Impact of COVID-19 Vary by Gender? Front Sociol [Internet]. 2021 Jun 15 [cited 2026 Feb 12];6:650729. doi:10.3389/fsoc.2021.650729 Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2021.650729

- Logie CH, Turan JM. How Do We Balance Tensions Between COVID-19 Public Health Responses and Stigma Mitigation? Learning from HIV Research. AIDS Behav [Internet]. 2020 Apr 7 [cited 2026 Feb 12];24(7):2003-6. doi:10.1007/s10461-020-02856-8 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02856-8

- James PB, Wardle J, Steel A, Adams J. Post‐Ebola psychosocial experiences and coping mechanisms among Ebola survivors: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health [Internet]. 2019 Mar 7 [cited 2026 Feb 12];24(6):671-91. doi:10.1111/tmi.13226 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.13226

- Kelly JD, Weiser SD, Wilson B, Cooper JB, Glayweon M, Sneller MC, Drew C, Steward WT, Reilly C, Johnson K, Fallah MP. Ebola virus disease-related stigma among survivors declined in Liberia over an 18-month, post-outbreak period: An observational cohort study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2019 Feb 27 [cited 2026 Feb 12];13(2):e0007185. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0007185 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007185

- Singh R, Subedi M. COVID-19 and stigma: Social discrimination towards frontline healthcare providers and COVID-19 recovered patients in Nepal. Asian J Psychiatr [Internet]. 2020 Oct [cited 2026 Feb 12];53:102222. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102222 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102222

- AlAteeq DA, Aljhani S, Althiyabi I, Majzoub S. Mental health among healthcare providers during coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health [Internet]. 2020 Oct [cited 2026 Feb 12];13(10):1432-7. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2020.08.013 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2020.08.013

- Connell R. Gender, health and theory: Conceptualizing the issue, in local and world perspective. Soc Sci Med [Internet]. 2012 Jun [cited 2026 Feb 12];74(11):1675-83. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.006 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.006

- Turan JM, Elafros MA, Logie CH, Banik S, Turan B, Crockett KB, Pescosolido B, Murray SM. Challenges and opportunities in examining and addressing intersectional stigma and health. BMC Med [Internet]. 2019 Dec [cited 2026 Feb 12];17(1):7. doi:10.1186/s12916-018-1246-9 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1246-9

- Abramowitz SA, Bardosh KL, Leach M, Hewlett B, Nichter M, Nguyen VK. Social science intelligence in the global Ebola response. Lancet [Internet]. 2015 Jan 24 [cited 2026 Feb 12];385(9965):330. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60119-2 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60119-2

- Nyblade L, Stockton MA, Giger K, Bond V, Ekstrand ML, Lean RM, Mitchell EMH, Nelson LRE, Sapag JC, Siraprapasiri T, Turan J, Wouters E. Stigma in health facilities: why it matters and how we can change it. BMC Med [Internet]. 2019 Feb 15 [cited 2026 Feb 12];17(1):25. doi:10.1186/s12916-019-1256-2 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1256-2

- Imran N, Afzal H, Aamer I, Hashmi AM, Shabbir B, Asif A, Farooq S. Scarlett Letter: A study based on experience of stigma by COVID-19 patients in quarantine. Pak J Med Sci [Internet]. 2020 Oct 17 [cited 2026 Feb 12];36(7). doi:10.12669/pjms.36.7.3606 Available from: https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.36.7.3606

- Bhattacharya P, Banerjee D, Rao TS. The “Untold” Side of COVID-19: Social Stigma and Its Consequences in India. Indian J Psychol Med [Internet]. 2020 Jul [cited 2026 Feb 12];42(4):382-6. doi:10.1177/0253717620935578 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/0253717620935578

- Bagcchi S. Stigma during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Infect Dis [Internet]. 2020 Jul 14 [cited 2026 Feb 12];20(7):782. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30498-9 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30498-9

- Lo LLH, Suen YN, Chan SKW, Sum MY, Charlton C, Hui CLM, Lee EHM, Chang WC, Chen EYH. Sociodemographic correlates of public stigma about mental illness: a population study on Hong Kong’s Chinese population. BMC Psychiatry [Internet]. 2021 May 29 [cited 2026 Feb 12];21(1):274. doi:10.1186/s12888-021-03301-3 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03301-3

- Pulerwitz J, Michaelis A, Weiss E, Brown L, Mahendra V. Reducing HIV-Related Stigma: Lessons Learned from Horizons Research and Programs. Public Health Rep [Internet]. 2010 Mar 1 [cited 2026 Feb 12];125(2):272-81. doi:10.1177/003335491012500218 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/003335491012500218

- Li J, Liang W, Yuan B, Zeng G. Internalized Stigmatization, Social Support, and Individual Mental Health Problems in the Public Health Crisis. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2020 Jun 23 [cited 2026 Feb 12];17(12):4507. doi:10.3390/ijerph17124507 Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124507

- Francis Asuquo E, Ackley Akpan-Idiok P. The Exceptional Role of Women as Primary Caregivers for People Living with HIV/AIDS in Nigeria, West Africa. In: Cascella M, John Stones M, editors. Suggestions for Addressing Clinical and Non-Clinical Issues in Palliative Care [Internet]. London: IntechOpen; 2020 Sep 29 [cited 2026 Feb 12]. doi:10.5772/intechopen.93670 Available from: https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.93670

- Sileo KM, Reed E, Kizito W, Wagman JA, Stockman JK, Wanyenze RK, Chemusto H, Musoke W, Mukasa B, Kiene SM. Masculinity and engagement in HIV care among male fisherfolk on HIV treatment in Uganda. Cult Health Sex [Internet]. 2018 Nov 13 [cited 2026 Feb 12];21(7):774-88. doi:10.1080/13691058.2018.1516299 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2018.1516299

- Siu GE, Wight D, Seeley JA. Masculinity, social context and HIV testing: an ethnographic study of men in Busia district, rural Eastern Uganda. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2014 Jan 13 [cited 2026 Feb 12];14(1):33. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-33 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-33