Research![]() | Volume 8(1), Article 9, 15 Apr 2025

| Volume 8(1), Article 9, 15 Apr 2025

Trends and distribution of malaria among children under five in Tamale Metropolis in Ghana, amidst interventions: Analysis of surveillance and program data, 2017 -2021

Shahadu Shembla Sayibu1,2,&, Basil Benduri Kaburi1, Dora Dadzie1, Delia Bandoh1, Isaac Baffoe-Nyarko1, Charles Lwanga Noora1, Abdul Gafaru Mohammed1, Francis Genye Salifu2, Peter Apetorgbor2, Paul Hilarius Asiwome Kosi Abiwu2, Ernest Kenu1

1Ghana Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program, Accra, Ghana, 2Tamale Metropolitan Health Directorate, Ghana Health Service, Tamale, Ghana

&Corresponding author: Shahadu Shembla Sayibu, Ghana Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program, Accra, Ghana, Tamale Metropolitan Health Directorate, Ghana Health Service, Tamale, Ghana. Email address: drshembla@yahoo.co.uk

Received: 30 May 2024 – Accepted: 10 Apr 2025 – Published: 15 Apr 2025

Domain: Malaria Control, Child Health, Infectious Disease Epidemiology

Keywords: Surveillance, Data Analysis, Malaria control interventions, Seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC), Insecticidal nets (ITN)

This article is published as part of the Eighth AFENET Scientific Conference Supplement: Volume Two, commissioned by

African Field Epidemiology Network

Ground Floor, Wings B & C

Lugogo House

Plot 42, Lugogo By-Pass

PO Box 12874 Kampala

Uganda.

©Shahadu Shembla Sayibu et al Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Shahadu Shembla Sayibu et al. Trends and distribution of malaria among children under five in Tamale Metropolis in Ghana, amidst interventions: Analysis of surveillance and program data, 2017 -2021. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8 Suppl 12:9. https://doi.org/ 10.37432/jieph.supp.2025.8.2.12.11

Abstract

Introduction: Despite the distribution of insecticide-treated nets (ITN), and seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) in Tamale Metropolis, the malaria burden started increasing in 2021. We described the distribution and trends of malaria cases; and evaluated SMC and ITN coverages among children under five years (under-5).

Methods: Data sources were District Health Information Management System II (DHIMS II) at Tamale Metropolis from 2017 – 2021, Ghana Malaria Control Program reports, Ghana Expanded Program on Immunization and the Ghana Statistical Services. Variables included: under-5 malaria cases (tested or not tested) and deaths; ITN distributed to under-5s; and SMC doses distributed. We computed percentages, constructed CUSUM-2 thresholds for trend analysis. SMC and ITN coverages were extracted from the DHIMS II as pre-populated indicators (i.e., children under-5 who got an ITN at measles-2 vaccination, and those who received SMC per cycle). We compared findings with WHO targets.

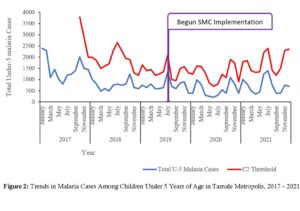

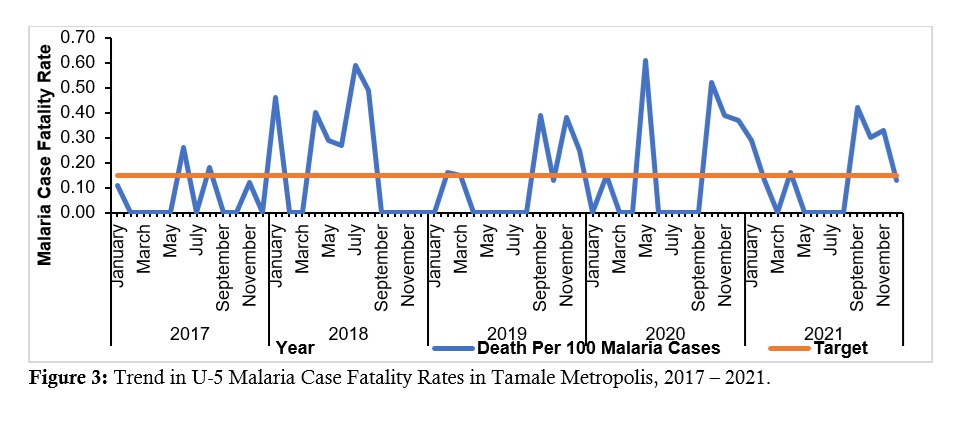

Results: Total malaria cases among children under five years were 50,379. Children 1-4years old accounted for 74.8% (37697/50379). Presumptively-treated cases were 79.28% (13694/17272) in 2017, 54.4% (9586/17626) in 2018, 48.5% (6294/12976) in 2019, 2.1% (144/6742) in 2020 and 10.33% (875/8471) in 2021. Total malaria cases decreased from 2,300 in January 2017 to 300 mid-period, rising to 1000 from July 2020; seasonal (July-November) peaks followed similar trends. Mean ITN coverage was 50.8%, while SMC cycle coverages were all below 90%.

Conclusion: While malaria cases resurged in 2021, case fatality rates increased throughout the period. Presumptive treatment rates decreased, though, still above WHO target. This inflated neonatal malaria cases. SMC and ITN coverages were poor, suggesting why malaria cases increased. Findings informed facilitation of health workers’ discussion forum on adherence to the WHO’s Test, Treat and Track strategy and boosting of ITN and SMC coverage, as well as audit into cases and deaths.

Introduction

Malaria is still endemic and a main cause of morbidity and mortality in most parts of Sub-Saharan Africa. About 70% of worldwide burden of malaria is borne by only 11 countries, 10 of which are in the WHO Africa Region [1], including Ghana. The African Region also accounted for 80% of the global under-5 malaria deaths in 2021 [2].

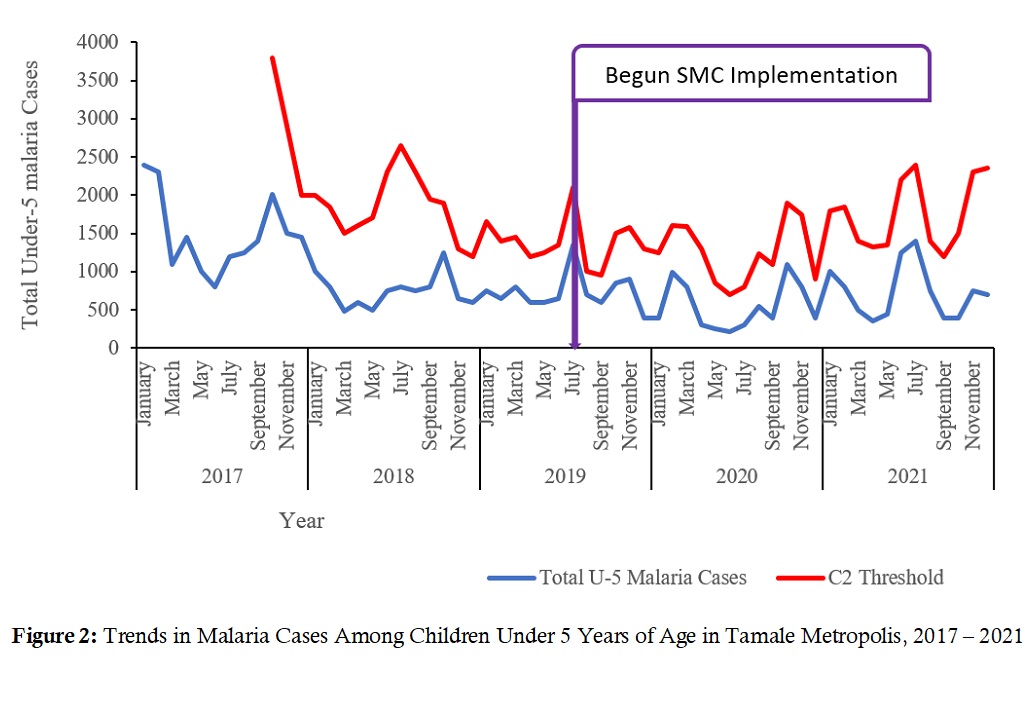

In 2016, the Ghana Malaria Indicator Survey revealed that Northern Region had the fourth largest prevalence of malaria (25%) among children under-5 years of age and the Tamale Metropolis contributed the largest proportion (over one-quarter) of cases [3]. Also, while the general case fatality rate (CFR) in Ghana had reduced to 0.06% in 2020, the Northern Region was concerned about the high number of deaths and CFR (mean above target of 0.15% – the national target for malaria CFR is 0.15 deaths per 100 malaria cases.) especially among children under-5 [4].

Long-lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLINs or ITNs); seasonal malaria chemo-prevention (SMC) to children under-5; and case management are effective malaria control interventions [2] implemented in the Tamale Metropolis. Although malaria interventions have reduced malaria cases in Sub-Saharan Africa by nearly 70% between 2001 and 2015 [5], among all age categories, malaria still remained a significant cause of morbidity and mortality with the burden actually rising among the under-5s since the year 2000 [6].

In addition, Ghana subscribed to the WHO recommendation of Test, Treat and Track (3Ts) in 2010 and developed guidelines to that effect [7], using the District Health Management Information System (DHIMS II) as the single largest tracking tool in Ghana. Evidence suggests that practitioners may still not be testing all cases [8], especially some private facilities.

Data quality is an integral part of disease surveillance systems [9]. Routine analysis ensures quality and can help evaluate the effectiveness of disease control programs [10] and fulfillment of surveillance [11]. Tamale Metropolis defaulted on routine analysis for many years.

Our study looked at the distribution of malaria cases and deaths, and to uncover any peculiarities. At the same time, a look at presumptive treatment rates offered insights into how appropriately cases were managed once they were suspected. While an appraisal of case fatality rates generated discussions whether deaths were in right proportions to the trend in malaria cases or not. Again, we looked at the distribution of the main malaria control interventions in the metropolis namely SMC and ITN, and tried to situate our findings in the context of how the burden of malaria had been in the Tamale Metropolis.

Methods

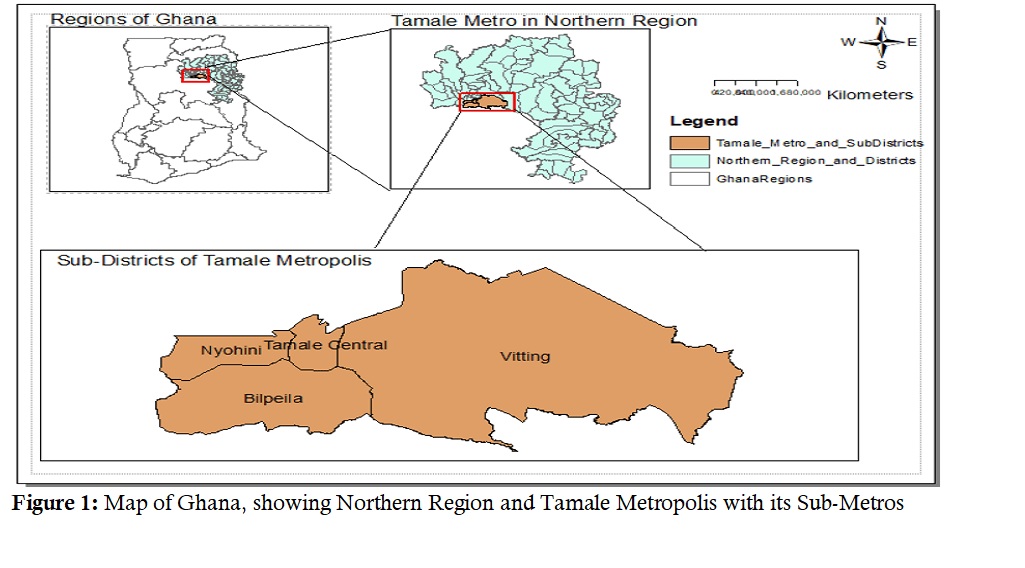

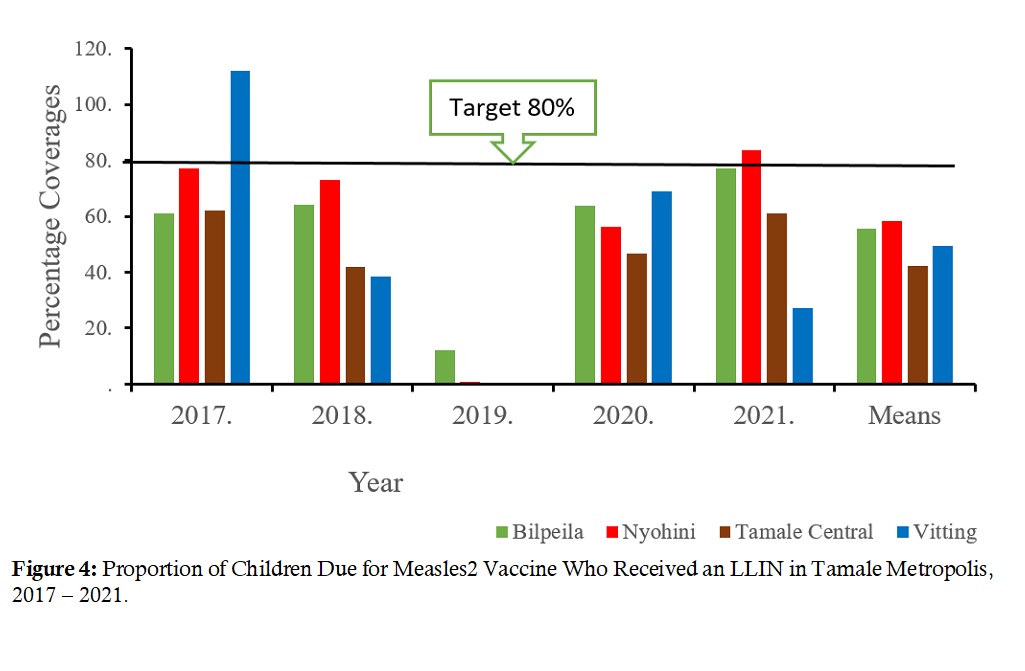

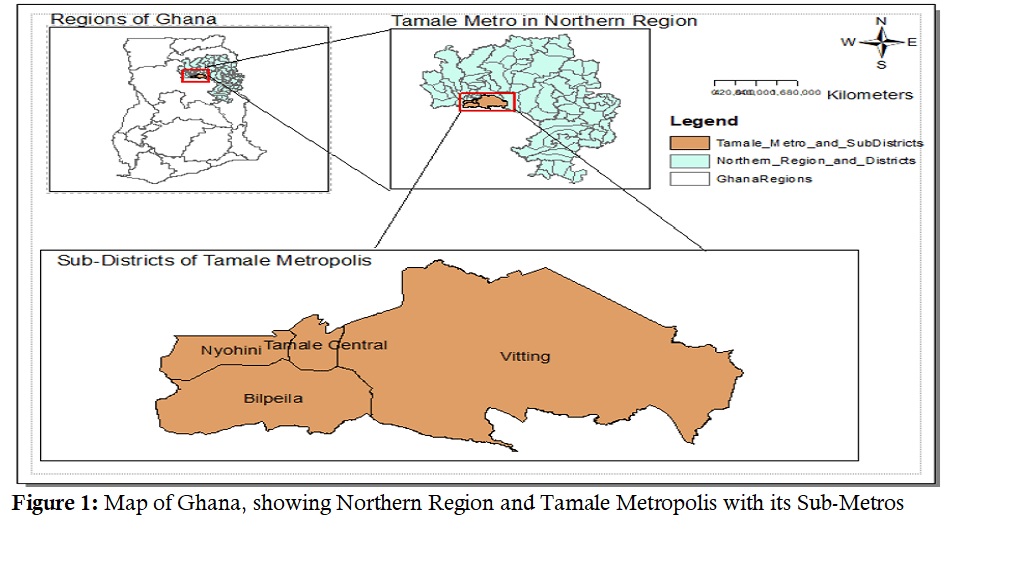

The study setting was the Tamale Metropolis in the Northern Region of Ghana. According to 2021 Ghana population and housing census (PHC) the Tamale Metropolis recorded a total population of 374,744. Data sets from the Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) showed the Tamale Metropolis had estimated the population of children under the age of 15 years to be 32.5% (121,710/374,744) while children under five years of age were 15.5% (57,957/374,744), with a 2021 growth projection of 2.9%. Tamale Metropolis is arranged into four Health Sub-Districts/Sub-Metros (Bilpeila, Nyohini, Tamale Central, and Vitting) (Figure 1). Tamale Metropolis has 44 health facilities of which there are 17 Community-based Health Planning Services (CHPS) compounds – which are the lowest levels of care concerned with primary and preventive services, and refering cases appropriately (Figure 1).

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study involving secondary data analysis of under-5 malaria data from Tamale Metropolis, Ghana. We conducted the study from 2017 to 2021.

Data sources

Data were retrieved from the District Health Information Management System II (DHIMS II) at the Metropolitan Health Directorate. Other sources of data included reports to the Malaria Control Program from within the Metropolis, Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) and Ghana Statistical Survey (GSS).

Data collection and management

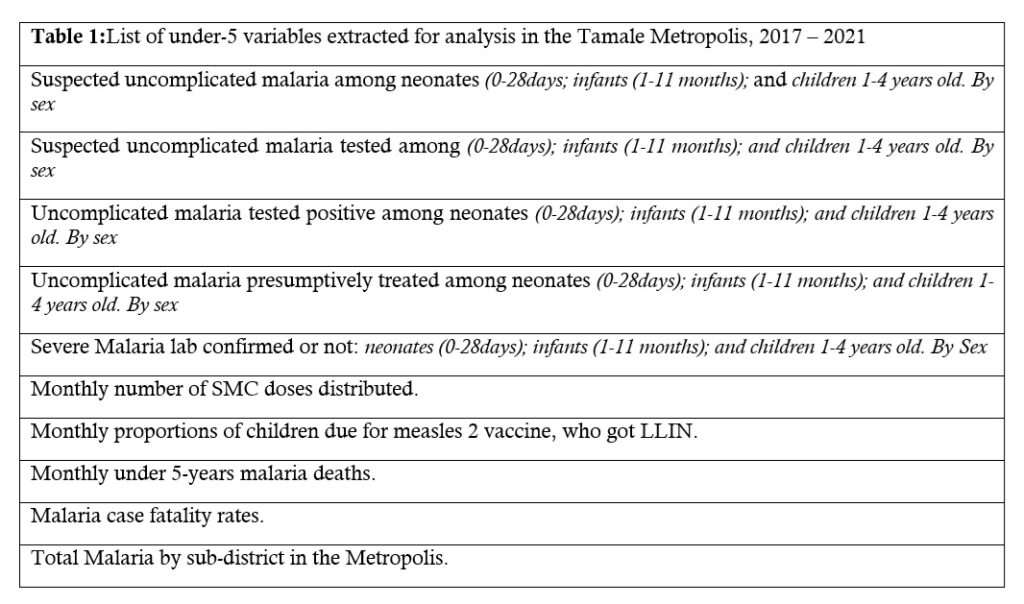

From the DHIMS II we downloaded malaria data sets, including some pre-calculated respective rates. We also downloaded data from National Malaria Control Program, Ghana Statistical Services and Expanded Program on Immunization. All data were stored on a password-protected computer imported onto MS Excel for analysis. The age groups used to record malaria morbidity data in the DHIMS II were: neonates (0-28 days old); infants (1-11 months old); children 1-4 years old. The main variables and pre-calculated rates such as case fatality rates, and the proportion of children receiving the second dose of measles vaccine who also received an ITN were all extracted from the DHIMS II (Table 1).

Data analysis

We conducted a descriptive secondary data analysis on under-5 malaria data from January 2017 to December 2021. Data were checked for quality, cleaned, and organized into tables. We calculated the proportion of malaria cases among the under-5 age groups; number of malaria cases per 1000 under-5 population; proportion of malaria cases treated presumptively; and test positivity rates. However, number of deaths per 100 malaria cases (case fatality rates), ITN Coverage (proportion of children due for measles-2 vaccine who got an ITN), and SMC Coverage {“Percentage of children aged 3–59 months who received SMC per cycle during the transmission season” [12]}, were extracted from DHIMS II. We constructed cumulative sum (CUSUM-2) threshold for trend analysis of malaria cases. The CUSUM 2 threshold was drawn from the total malaria cases employing the formular: X + 3*SD, (where X = mean, SD = standard deviation). The mean was obtained for the prior seven months, skipping the two most recent months so that any possible incomplete data, discovered later, may not affect the results.

Ethical Considerations

With the help of Ghana Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program and School of Public Health, we sought permission from the Tamale Metropolitan Health Directorate through the Northern Regional Health Directorate (Ghana Health Service). At the time of this data analysis (2023) all surveillance activities in Ghana were considered part of the routine activities of the District/Metropolitan/Regional Health Directorate(s) and as such did not require ethical clearance if conducted by a staff (many of the authors were staff). A copy of a 2017 letter to this effect each from Director for Surveillance (National) and Deputy Director Public Health (Northern Region) are attached in appendix section. The Data did not contain personal identifiers. Nonetheless, we stored data under password.

Results

Age and sex distribution of under-5 malaria cases

The total number of suspected under-5 malaria cases in the Tamale Metropolis from 2017 to 2021 was 82,522. The total number of under-5 malaria cases (confirmed and presumed) treated in the metropolis over the five years was 50,379 cases. Males accounted for 53.0% (26720/50379) of the total treated malaria cases. Among the treated malaria cases, children aged 1-4 years old accounted for 74.8% (37697/50379); neonatal malaria cases in the metropolis over the five-year period were 1.7% (845/50379).

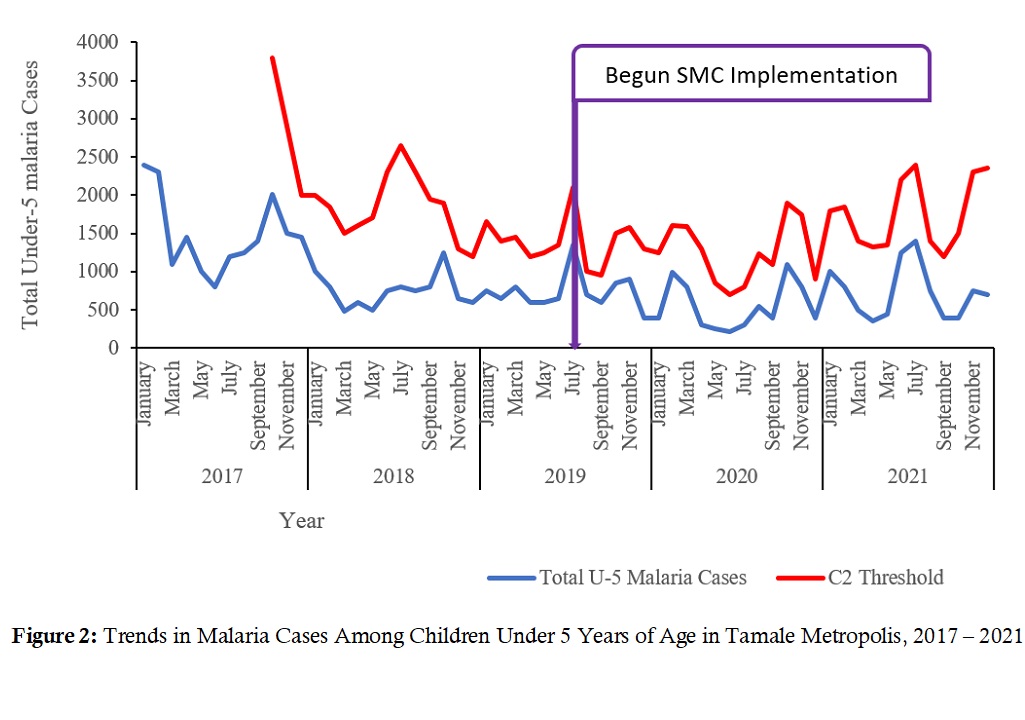

Trend in under-5 malaria cases

Total under-5 malaria cases (treated) are shown compared to cumulative sum (CUSUM 2) threshold. Total number of cases in January 2017 was 2300, declined steadily to 250 cases in June 2020. The number of malaria cases among the under-5s started rising after June 2020 and into 2021 (Figure 2).

Presumptive treatment rates

In 2017, the proportion of presumptively treated malaria was 76.1% (13694/17995); 54.4% (9586/17626) in 2018; 48.5% (6294/12976) in 2019; 2.1% (144/6742) in 2020; and rose to 10% (875/8471) in 2021. Seventy-four percent, (626/845) of all neonatal cases were presumptively treated over the five years.

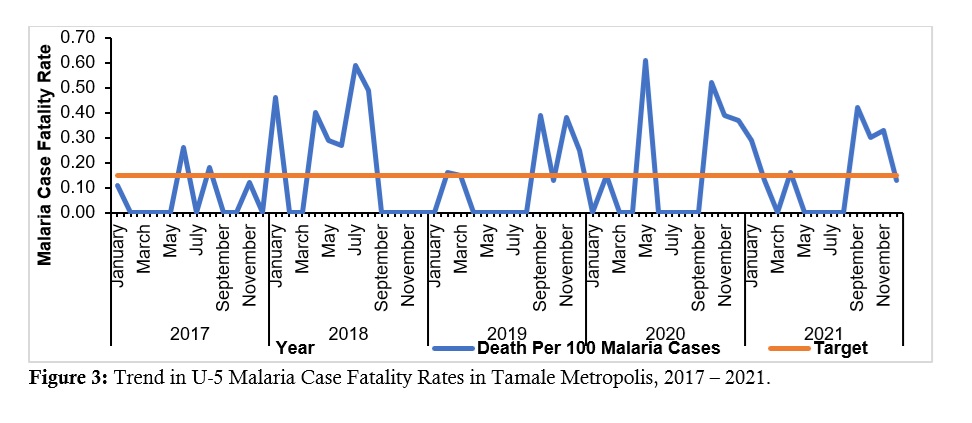

Case fatality rates (CFR)

In some years (2018) the Tamale Metropolis recorded CFRs as high as 0.63% (Figure 3).

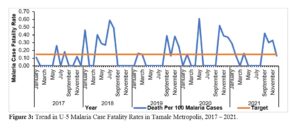

Malaria control interventions

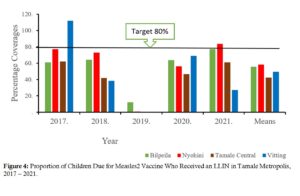

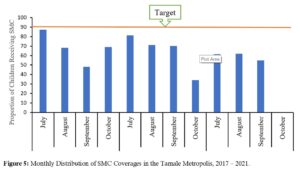

ITN (LLIN) coverage: For this intervention, the Vitting Sub-Metro in 2017 achieved a coverage of 98%, while the Nyohini Sub-Metro had 83% in 2020. All other coverages were below the 80% target, with 2019 coverages all close to zero (Figure 4).

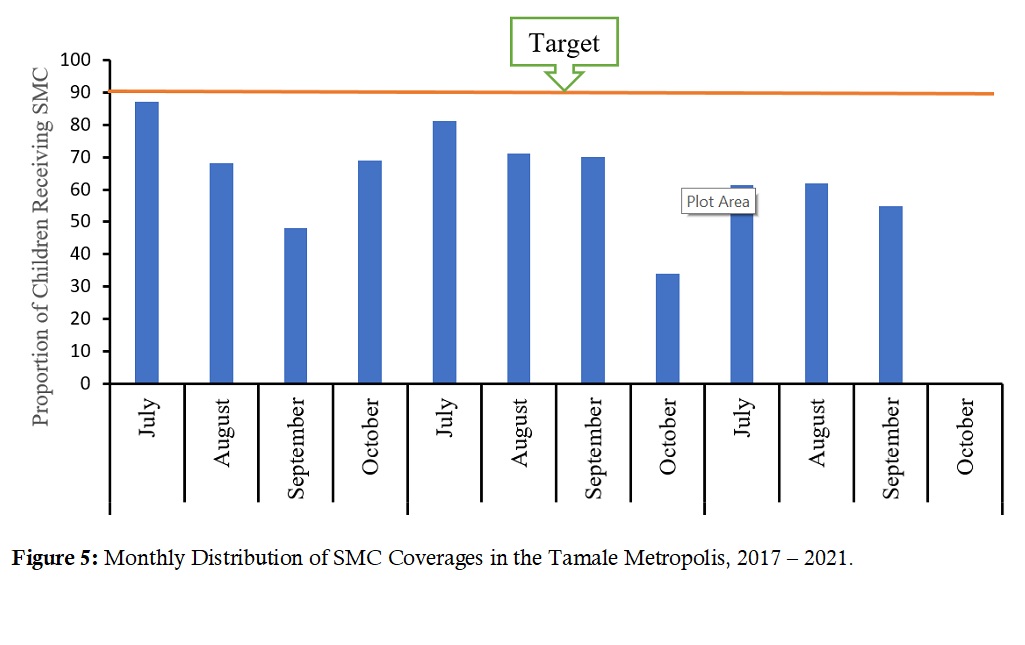

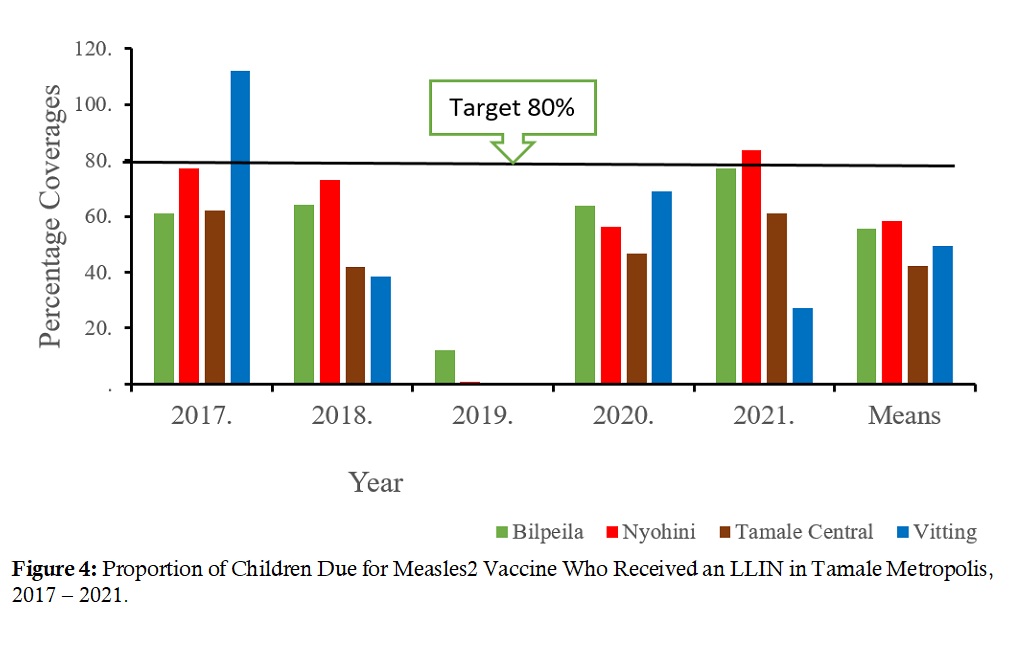

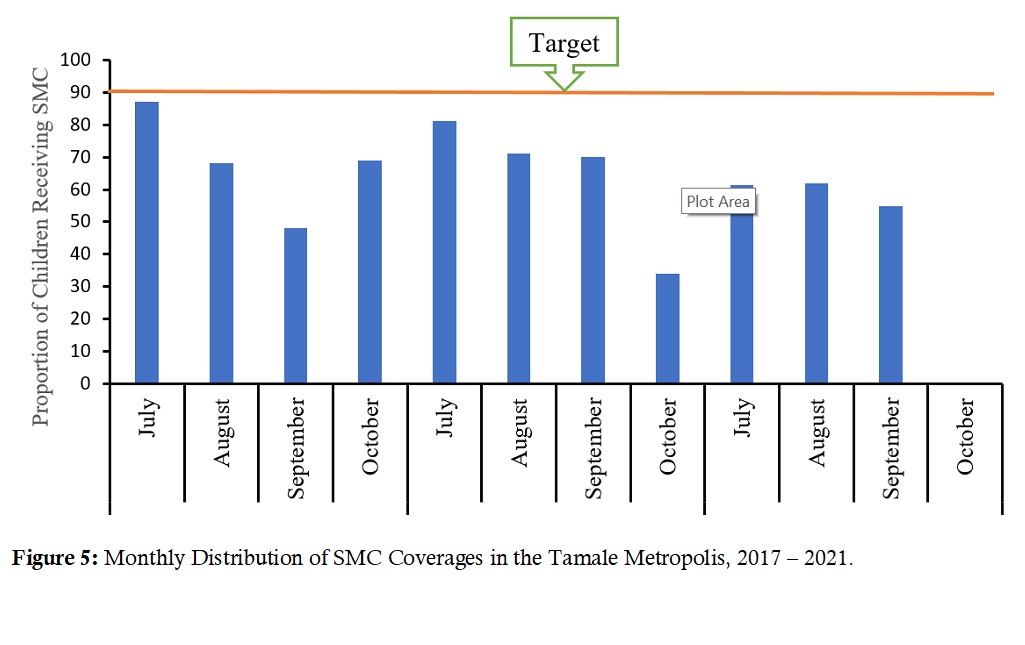

Seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) coverage: In the years 2019 and 2020, SMC was given from July to October. However, in 2021 it was given only from July-September, with October having 0% coverage. The total three-year SMC doses distributed was 814,188. For monthly cycle coverages, July 2017 had 86% while July 2018 saw 83% coverages (Figure 5).

Discussion

Our analysis of the under-5 malaria data revealed that though there had been periodic surges in malaria cases none was up to the threshold to declare an outbreak of malaria. Neonates were disproportionately subjected to treatments without testing, though the practice improved towards the year 2020.Also, case fatality rate in some years (2018) were as high as 0.63%. In addition, only Vitting Sub-Metro in 2017 and Nyhini Sub-Metro in 2020 had ITN coverages above the target. Lastly, SMC monthly cycle coverages in only July of 2017 and 2018 were up to 86% and 83% respectively.

Demographic characteristics of under-5 malaria cases

The demographic characteristics of recorded under-5 malaria cases revealed a slight male predominance for the five years. Similarly, Dao and colleagues in 2021 reported male predominance when they assessed the burden of malaria among children under-5 and their caregivers’ health seeking behavior in an artisanal mining site in Ghana [13]. Children aged 1-4 years accounted for more than three-quarters of all malaria cases. When Khagayi and team (2017) used a Bayesian model to assess the relationship between prevalence of malaria among various age groups, they found that children aged 1-4 years had higher malaria prevalence and mortality than adults [14]. For each age category, malaria cases declined steadily from 2017 to the lowest in 2020, and started increasing in 2021.

Trends in malaria cases

Neonatal malaria made a sharp decline annually. This is despite a yearly projected average population growth of about 2.1% [15]. The reduction therefore, may suggest improvement in case management such as clinicians’ increased compliance to the test-before-treat guidelines by NMCP [16] and WHO [17]. Also, under-reporting of cases due to disruption of service by Covid-19 [18] could have contributed to the low number of cases in 2020. Furthermore, the availability of test logistics may have influenced compliance to the test, treat and track (3Ts) policy, while compliance itself reduced all malaria cases as well as unnecessary treatments. A randomized controlled trial found that RDT helped reduce unnecessary administration of anti-malarial medications, but at the same time did not reduce the prescription of anti-malarial medications to those who needed them [19]. A review and meta-analysis stated that using the RDTs correctly in low resource areas could confirm diagnosis, speed up care and prevent inappropriate prescription and cost [20]. Contrary to the foregoing, Bonko et al., (2019) in Burkina Faso thought that RDTs may actually lead to overestimation of febrile illness (malaria) [21].

Distribution of under-five years old malaria cases by time; and proportion presumptively treated

Tamale Metro recorded the lowest levels of malaria cases in mid-2020 coinciding with the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic. According to WHO (2021), Covid-19 had a possibly significant impact on malaria control by disrupting supply of logistics, but this impact was difficult to measure [18]. Records-keeping might also have been disrupted by the Covid-19 Pandemic. To buttress this, for the year 2020, Zimbabwe had recorded malaria cases in excess of each of the three preceding years, presumably due to disruptions in malaria prevention and care [22]. Over the reviewed years, in Tamale Metropolis, no case crossed the CUSUM-2 threshold, suggesting that no ‘outbreak’ of malaria occurred. This suggests that malaria control interventions have had a positive impact on the disease possibly reducing transmissions.

The proportion of cases that were presumptively treated was arguably a key factor that influenced the trends in malaria cases at the time in the Tamale Metropolis. Being a proportion of the total malaria cases treated, high presumptive rates implied that a lower proportion was tested or confirmed before treatment. Many instances saw large numbers of malaria cases treated presumptively especially in the year 2017 when these proportions averaged over 70% among each age category. However, in the year 2020 the proportion of presumptively treated cases averaged about 2%. This finding suggests care givers were adhering to the policy of testing for malaria before treating which, in turn reduced unnecessary treatments. Although, closer to the WHO recommendations of testing all cases before treating [7,16], there’s still room for improvement. This is because Ghana is now in pre-elimination phase, and presumptive treatment rates should be 0%. In 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic may have lowered test thresholds among prescribers. The explanation given by care providers that non-testing resulted from logistic downtime was buttressed by a study which suggested that providing RTD led to significantly reduced number of inappropriate treatments to patients who presented with symptoms [19]. Clinical features alone have very low specificity in malaria diagnosis, leading to overtreatment [23].

Case fatality rate (CFR)

For most parts of the five years, the CFRs were above the national target, even during the time when malaria cases and deaths had been reducing, i.e., before 2021. This was a matter of concern and required further investigation, such as clinical audits, as this falls in the category of factors that require clinical audit [24].

LLIN coverage

The mean coverage rate was lower than the minimum 80% [25]. This level of coverage can stagnate malaria control, and serve as a nidus for malaria vector resistance since rooms with no LLINs allow mosquitoes to recuperate, develop resistance and reproduce [26]. The LLINs are distributed during Child Welfare Clinics (CWC) at the second measles-mumps-rubella (or measles-2) vaccination. So, low measles-2 coverages is expected to lower LLIN coverage, and the converse may be true.

We thought low LLIN coverage was partly responsible for the increasing number of malaria cases. This was similar to a Ghanaian data analysis from 2015 to 2019 that found malaria cases to be increasing between 2015 and 2019 [27]. Also, two separate studies in DRC found that increased ownership and use of LLINs led to reduced malaria cases [28,29].

Seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) coverage.

Health officers explained that in 2021 LLINs were distributed for only three months because of logistic constraints. The Deputy Director Public Health (DDPH) confirmed this, and said even in October 2021, SMC medications never arrived. The delays (or lack) were ascribed to re-routing of resources during Covid-19 pandemic, which might have also led to reduced human contact. Such interruptions in SMC distribution and poor coverage, was partly responsible for malaria case surge. Some authors have reported similarly and even suggested extending coverage to children up to 14 years old [30], while others have called for increase in SMC cycles to five [31].

A meta-analysis found up to 75% decrease in clinical malaria when SMC was compared to a placebo. The same authors acknowledged donor fatigue as a disincentive in continuing the SMC project, as may be the case with Tamale Metropolis [32]. Also, reported among the challenges to SMC coverage are that nutrition, EPI, and SMC do not integrate, making sustainability difficult once funding declines [33]. Meaning, malaria control efforts can be forestalled once this SMC project faces any setback, leading to resurgence of the disease.

Limitations

Data inconsistencies: Calculating age-group-specific malaria incidence ratios and ITN coverage were not feasible, due to lack of case-based data. The Malaria Elimination Program uses the age groups: neonates, 1-11months, and 1-4 years, while the Population Census only makes room for calculating under-5 and under-2 years old. Therefore, malaria case distributions were analyzed using program-specific age categorization. Also, the Elimination Program tends to now focus on absolute numbers of cases. This was further compounded by the lack of data for three-yearly mass distributions. However, the proxy indicator – the proportion of children due for measles 2 who also got ITN was readily accessible in the DHIMS II and was used instead. This allowed for approximate estimation of ITN coverages.

Conclusion

High number of malaria cases especially in the first few years corresponded with above-target presumptive treatment rates, which inflated the number of malaria cases, particularly malaria cases among neonates. The sustained increase in CFR even during decline in the number of malaria cases raised the need for investigations such as clinical audits. Coverages of the two main interventions were poor.

We recommended that the Metropolitan Director should organize refresher training for prescribers to strictly test and treat, aiming at presumptive treatment rates of 0%. The NMEP should avail supplies of SMC and LLINs for distribution. As Public Health Action, we discussed ways of improving coverage and entreated matching the distributions with immunization and other Child Welfare activities. Also, we discussed with the NMEP ways to conduct case management audits for in-patient malaria cases, which is currently ongoing.

What is already known about the topic

- To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this topic is the first of its kind in the Tamale Metropolis, though some authors elsewhere have conducted studies along similar lines. For example, Afagbedzi et al., (2022) carried out a study on “Impact evaluation of long-lasting insecticidal nets distribution campaign on malaria cases reported at outpatient departments across all the regions in Ghana”. However, their study only looked at one aspect of our topic – intervention (impact of ITN distribution and malaria cases). Since the implementation of the two main malaria control interventions (SMC and insecticide-treated net distribution) in the Tamale Metropolis, data generated from these interventions have not been analyzed in relation to malaria burden (especially among children under-5 years old) to generate insights into how malaria control is faring with the interventions

What this study adds

- Why malaria burden is increasing despite interventions

- Presumptive treatments can over-rate malaria case numbers

- Findings informed the direction of discussions on how to boost malaria control in Tamale

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Northern Regional Health Directorate led by Dr. Paul H. A. K. Abiwu (Deputy Director Public Health), the Disease Control Officer of Tamale Metropolitan Health Directorate Mr. Peter Apetorgbor, who represented the Director and granted us the permission to carry out the data analysis. Lastly, we acknowledge the technical support from the Ghana Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program (GFELTP).

Authors´ contributions

SSS: Conceptualized the plan of the analysis, collected data sets and conducted the analysis. He prepared the initial draft of the manuscript, addressed all the reviewer’s comments, did proofreading while fine-tuning the manuscript.

BBK: Helped conceptualize the plan of the analysis, oversaw the entire process including its planning, execution, and manuscript preparation, revised the initial draft manuscript for scientific content, clarity, and accuracy, and helped address reviewers’ comments. Also, assisted in data review and cleaning, proofread, and reviewed the draft manuscripts.

CNL: Assisted in data review and cleaning, proofread, and reviewed the draft manuscripts.

IBN: Assisted in data extraction, review, cleaning and analysis. Also assisted in response to reviewer’s comments.

AGM: Assisted in data review and cleaning, proofread, and reviewed the draft manuscripts.

FGS: Assisted in data extraction, review, cleaning and analysis. Also assisted in response to reviewer’s comments.

PA: Assisted in data extraction, review, cleaning and analysis. Also assisted in response to reviewer’s comments.

PHAKA: Assisted in data extraction, review, cleaning and analysis. Also assisted in response to reviewer’s comments.

DD: Helped conceptualize the plan of the analysis, oversaw the entire process including its planning, execution, and manuscript preparation, revised the initial draft manuscript for scientific content, clarity, and accuracy, and helped address reviewer’s comments.

DB: Helped conceptualize the plan of the analysis, oversaw the entire process including its planning, execution, and manuscript preparation, revised the initial draft manuscript for scientific content, clarity, and accuracy, and helped address reviewer’s comments.

EK: Reviewed and approved the protocol of the analysis, oversaw the entire process including its planning, execution, and manuscript preparation, revised the initial draft manuscript for scientific content, clarity, and accuracy, and helped address reviewers’ comments. Also revised the manuscript, proofread, and approved the final work.

References

- WHO. High burden to high impact: a targeted malaria response [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2018 Nov 19 [cited 2025 Apr 10]. 7 p. WHO Reference Number: WHO/CDS/GMP/2018.25 Rev 1. Download PDF to view full text.

- WHO. Malaria: Key facts [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2024 Dec 11 [cited 2025 Apr 10].

- Ghana Statistical Service (GSS). Ghana Malaria Indicator Survey 2016 [Internet]. Accra (Ghana): GSS; 2016 May [cited 2025 Apr 10]. 138 p.

- Ghana Health Service, National Malaria Control Programme. 2021- 2025 Malaria Strategic Plan [Internet]. Accra (Ghana): GHS; 2021 [cited 2025 Apr 11]. 144 p.

- Korenromp E, Hamilton M, Sanders R, Mahiané G, Briët OJT, Smith T, Winfrey W, Walker N, Stover J. Impact of malaria interventions on child mortality in endemic African settings: comparison and alignment between LiST and Spectrum-Malaria model. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2017 Nov 7 [cited 2025 Apr 10];17(S4):781. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4739-0

- Afoakwah C, Deng X, Onur I. Malaria infection among children under-five: the use of large-scale interventions in Ghana . BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2018 Apr 23 [cited 2025 Apr 10];18(1):536. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5428-3

- Akanteele Agandaa S, Kweku M, Agboli E, Takase M, Takramah W, Tarkang E, Gyapong J. Implementation and challenges of test, treat and track (T3) strategy for malaria case management in children under five years in the Bongo District, Ghana. Clin Res Trials [Internet]. 2016 Dec 15 [cited 2025 Apr 10];2(6):235-41. https://doi.org/10.15761/CRT.1000154

- Soniran OT, Abuaku B, Anang A, Opoku-Afriyie P, Ahorlu C. Factors impacting test-based management of suspected malaria among caregivers of febrile children and private medicine retailers within rural communities of Fanteakwa North District, Ghana . BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Oct 20 [cited 2025 Apr 10];21(1):1899. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11960-w

- Kayode GA, Amoakoh-Coleman M, Brown-Davies C, Grobbee DE, Agyepong IA, Ansah E, Klipstein-Grobusch K. Quantifying the validity of routine neonatal healthcare data in the greater Accra Region, Ghana . Petersen I, editor. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2014 Aug 21 [cited 2025 Apr 10];9(8):e104053. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0104053

- Roush SW. Chapter 19: Enhancing Surveillance. In: Roush SW, Baldy LM, Mulroy J, editors. Manual for the Surveillance of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; 2017 Nov 17 [cited 2025 Apr 10]. [about 6 p.].

- CDC. Updated Guidelines for evaluating public health surveillance systems: Recommendations from the Guidelines Working Group . MMWR [Internet] 2001 Jul 27 [cited 2025 Apr 10]; 50(RR13);1-35.

- Diawara F, Steinhardt LC, Mahamar A, Traore T, Kone DT, Diawara H, Kamate B, Kone D, Diallo M, Sadou A, Mihigo J, Sagara I, Djimde AA, Eckert E, Dicko A. Measuring the impact of seasonal malaria chemoprevention as part of routine malaria control in Kita, Mali . Malar J [Internet]. 2017 Aug 10 [cited 2025 Apr 11];16(1):325. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-017-1974-x

- Dao F, Djonor SK, Ayin CTM, Adu GA, Sarfo B, Nortey P, Akuffo KO, Danso-Appiah A. Burden of malaria in children under five and caregivers’ health-seeking behaviour for malaria-related symptoms in artisanal mining communities in Ghana . Parasites Vectors [Internet]. 2021 Aug 21 [cited 2025 Apr 11];14(1):418. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04919-8

- Khagayi S, Amek N, Bigogo G, Odhiambo F, Vounatsou P. Bayesian spatio-temporal modeling of mortality in relation to malaria incidence in Western Kenya . Carvalho LH, editor. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2017 Jul 13 [cited 2025 Apr 11];12(7):e0180516. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180516

- World Bank Group. Population growth (annual %) – Ghana [Internet]. Washington (DC): World Bank Group; c2025 [cited 2025 Apr 11]. [about 2 screens].

- Boadu NY, Amuasi J, Ansong D, Einsiedel E, Menon D, Yanow SK. Challenges with implementing malaria rapid diagnostic tests at primary care facilities in a Ghanaian district: a qualitative study. Malar J [Internet]. 2016 Feb 27 [cited 2025 Apr 11];15(1):126. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-016-1174-0

- WHO. WHO releases new malaria guidelines for treatment and procurement of medicines [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2010 Dec 10 [cited 2025 Apr 11].

- WHO. The e-2020 initiative of 21 malaria-eliminating countries: 2019 progress report [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2019 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Apr 11]. 15 p. Download PDF to view full text .

- Ansah EK, Narh-Bana S, Affran-Bonful H, Bart-Plange C, Cundill B, Gyapong M, Whitty CJM. The impact of providing rapid diagnostic malaria tests on fever management in the private retail sector in Ghana: a cluster randomized trial . BMJ [Internet]. 2015 Mar 4 [cited 2025 Apr 11];350:h1019. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1019

- Kabaghe AN, Visser BJ, Spijker R, Phiri KS, Grobusch MP, Van Vugt M. Health workers’ compliance to rapid diagnostic tests (Rdts) to guide malaria treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Malar J [Internet]. 2016 Mar 15 [cited 2025 Apr 11];15(1):163. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-016-1218-5

- Bonko MDA, Kiemde F, Tahita MC, Lompo P, Some AM, Tinto H, Van Hensbroek MB, Mens PF, Schallig HDFH. The effect of malaria rapid diagnostic tests results on antimicrobial prescription practices of health care workers in Burkina Faso . Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob [Internet]. 2019 Jan 28 [cited 2025 Apr 11];18(1):5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-019-0304-2

- Gavi S, Tapera O, Mberikunashe J, Kanyangarara M. Malaria incidence and mortality in Zimbabwe during the COVID-19 pandemic: analysis of routine surveillance data . Malar J [Internet]. 2021 May 24 [cited 2025 Apr 11];20(1):1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-021-03770-7

- WHO. WHO Guidelines for malaria, 16 February 2021 [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2021 Feb 16.; 5 – Case Management [cited 2025 Apr 11]. p. 61-110. Document No: WHO/UCN/GMP/2021.01.

- Esposito P, Canton AD. Clinical audit, a valuable tool to improve quality of care: General methodology and applications in nephrology . World Journal of Nephrology [Internet]. 2014 Nov 6 [cited 2025 Apr 11];3(4):249–55. http://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v3.i4.249

- WHO. Global Malaria Program: Achieving and maintaining universal coverage with long-lasting insecticidal nets for malaria control [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2017 Dec [cited 2025 Apr 11]. 4 p. Document No.: WHO/HTM/GMP/2017.20. Download pdf to view full text.

- Liu N. Insecticide resistance in mosquitoes: impact, mechanisms, and research directions. Annu Rev Entomol [Internet]. 2015 Jan 7 [cited 2025 Apr 11];60(1):537–59.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020828 Purchase or subscription required to view full text.

- Afagbedzi SK, Alhassan Y, Guure C. Impact evaluation of long-lasting insecticidal nets distribution campaign on malaria cases reported at outpatient departments across all the regions in Ghana . Malar J [Internet]. 2022 Dec 4 [cited 2025 Apr 11];21(1):370. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-022-04393-2

- Karemere J, Nana IG, Andrada A, Kakesa O, Mukomena Sompwe E, Likwela Losimba J, Emina J, Sadou A, Humes M, Yé Y. Associating the scale-up of insecticide-treated nets and use with the decline in all-cause child mortality in the Democratic Republic of Congo from 2005 to 2014 . Malar J [Internet]. 2021 May 29 [cited 2025 Apr 11];20(1):241. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-021-03771-6

- Levitz L, Janko M, Mwandagalirwa K, Thwai KL, Likwela JL, Tshefu AK, Emch M, Meshnick SR. Effect of individual and community-level bed net usage on malaria prevalence among under-fives in the Democratic Republic of Congo . Malar J [Internet]. 2018 Jan 18 [cited 2025 Apr 11];17(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-018-2183-y

- Konate D, Diawara SI, Sogoba N, Shaffer JG, Keita B, Cisse A, Sanogo I, Dicko I, Guindo MDA, Balam S, Traore A, Kante S, Dembele A, Kasse F, Denou L, Diakite SAS, Traore K, M’Baye Thiam S, Sanogo V, Toure M, Diarra A, Agak GW, Doumbia S, Diakite M. Effect of a fifth round of seasonal malaria chemoprevention in children aged 5–14 years in Dangassa, an area of long transmission in Mali . Parasite Epidemiology and Control [Internet]. 2023 Jan 2 [version of record 2023 Jan 18; cited 2025 Apr 11];20:e00283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parepi.2022.e00283

- Traore A, Donovan L, Sawadogo B, Ward C, Smith H, Rassi C, Counihan H, Johansson J, Richardson S, Savadogo JR, Baker K. Extending seasonal malaria chemoprevention to five cycles: a pilot study of feasibility and acceptability in Mangodara district, Burkina Faso . BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2022 Mar 5 [cited 2025 Apr 11];22(1):442. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12741-9

- Coldiron ME, Von Seidlein L, Grais RF.Seasonal malaria chemoprevention: successes and missed opportunities . Malar J [Internet]. 2017 Nov 28 [cited 2025 Apr 11];16(1):481. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-017-2132-1

- Souares A, Lalou R, Sene I, Sow D, Le Hesran JY. Factors related to compliance to anti-malarial drug combination: example of amodiaquine/sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine among children in rural Senegal . Malar J [Internet]. 2009 Jun 4 [cited 2025 Apr 11];8(1):118. https://doi.org/보기 1475-2875-8-118

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Tables

Table 1: List of under-5 variables extracted for analysis in the Tamale Metropolis, 2017 – 2021

| Variables (N=267) | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Age (Years) | ||

| 1-5 | 163 | 61.1 |

| 6-10 | 70 | 26.2 |

| 11-15 | 8 | 3.0 |

| Above 15 | 26 | 9.7 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 120 | 44.9 |

| Male | 147 | 55.1 |

| Occupation | ||

| Other | 31 | 11.7 |

| Pupil | 234 | 88.3 |

| District | ||

| Juaboso | 102 | 38.2 |

| Bibiani-Anhwiaso-Bekwai | 97 | 36.3 |

| Bodi | 37 | 13.9 |

| Wiawso | 25 | 9.4 |

| Bia West | 3 | 1.1 |

| Aowin | 2 | 0.8 |

| Suaman | 1 | 0.4 |

| Case Fatality | ||

| Total Deaths | 0 | 0 |

| N=Total number of cases | ||

Table 1: List of under-5 variables extracted for analysis in the Tamale Metropolis, 2017 – 2021

Figures

Figure 1: Map of Ghana, showing Northern Region and Tamale Metropolis with its Sub-Metros

Figure 2: Trends in Malaria Cases Among Children Under 5 Years of Age in Tamale Metropolis, 2017 – 2021

Figure 3: Trend in Under-5 Malaria Case Fatality Rates in Tamale Metropolis, 2017 – 2021

Figure 4: Proportion of Children Due for Measles2 Vaccine Who Received an LLIN in Tamale Metropolis, 2017 – 2021

Figure 5: Monthly Distribution of SMC Coverage in the Tamale Metropolis, 2017 – 2021

Keywords

- Surveillance

- Data Analysis

- Malaria control interventions

- Seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC)

- Insecticidal nets (ITN)