Research | Open Access | Volume 8 (2): Article 45 | Published: 26 Jun 2025

Performance of community health workers and associated factors in responding to yellow fever and COVID-19 outbreaks: A case study of Masaka District, Uganda, 2022

Nicholas Muhumuza1,&, Eric Segujja1, Abel Wilson Walekhwa2,3, Angela Kisakye1,4, Brenda Nakazibwe3, Prossy Nakito1, Charity Mutesi1, Carolyne Nyamar1, Sarah Paige5, Suzanne Kiwanuka1

1Department of Health Policy Planning and Management, Makerere University School of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, 2Diseases Dynamic Unit, Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom, 3Pathogen Economy Bureau, Science Technology and Innovation Secretariat Office of the President, 4African Field Epidemiology Network, Lugogo House, Plot 42, Lugogo Bypass, Kampala, Uganda, 5University of Wisconsin-Madison, United States

&Corresponding author: Nicholas Muhumuza, Department of Health Policy Planning and Management, Makerere University School of Public Health, College of Health Sciences Email: nicholasmuhumuza00@gmail.com

Received: 03 Dec 2024, Accepted: 23 Jun 2025, Published: 26 Jun 2025

Domain: Outbreak Investigation and Response, Field Epidemiology

Keywords: Community health workers, Outbreak response, Uganda

©Nicholas Muhumuza et al Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Nicholas Muhumuza et al. Performance of community health workers and associated factors in responding to yellow fever and COVID-19 outbreaks: A case study of Masaka District, Uganda, 2022. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8(2):45. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-24-02003

Abstract

Introduction: Community health workers (CHWs), also known as Village Health Teams (VHTs) in Uganda, play a crucial role in delivering healthcare to communities with limited access to formal health facilities. Their role in responding to yellow fever and COVID-19 outbreaks remains inadequately documented. This study examined the performance of Community Health Workers (CHWs) and associated factors in responding to the aforementioned outbreaks in Masaka District, Uganda.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted in Masaka District using quantitative methods. A total of 427 CHWs were selected using stratified random sampling. Performance was assessed using 10 key indicators based on CHWs’ roles in outbreak response, high performance was defined as scoring six or more. Data were analyzed using STATA version 14.0. Poisson regression with robust standard errors was employed to identify factors associated with CHW performance and to estimate crude and adjusted prevalence ratios (PRs) with 95% confidence intervals.

Results: Most respondents 279(65.3%) were females, 325(76.1%) depended on agriculture and 337(78.9%) lived in rural areas. The majority, 320 (74.9%), demonstrated high performance in responding to yellow fever and COVID-19 outbreaks. Key facilitators of performance included provision of record books (APR= 1.23; 95% CI: [1.06-1.43]), support supervision (APR=1.43; 95% CI: [1.04-1.96]), recognition by health workers (APR= 1.37; 95% CI; [1.02-1.85]), and receipt of financial incentives (APR=1.16; 95% CI: [1.04-1.30]). Barriers included use of foot as means of transport (CPR=0.69; 95% CI: [0.58-0.84]), never refunded transport costs to attend supervision meeting (CPR=0.72; 95% CI: [0.64-0.81]) and shortage of PPE (CPR=0.78; 95% CI: [0.71-0.86]).

Conclusion: CHWs demonstrated high performance in yellow fever and COVID-19 outbreak response, driven by training, recognition and case reporting tools. Both intrinsic (training, recognition) and extrinsic (financial incentives) motivators are essential for enhancing CHWs’ performance. The Ministry of Health and stakeholders should invest in sustainable incentives and continuous capacity-building for CHWs to strengthen disease outbreak responses in low-resource settings.

Introduction

CHWs play a significant role in ensuring equitable access to primary healthcare (PHC) services and have contributed to improvements in community health outcomes. Globally, CHW programs have been prioritized as a means of strengthening PHC delivery and achieving Universal Health Coverage [1]. It is estimated that approximately five million CHWs are currently working worldwide [2]. In low and middle-income countries (LMIC), governments have embraced decentralized health policies, which have facilitated the deployment of CHWs at the community level, where they serve as the first contact in the health systems [3]. CHW programs act as an intermediary between health systems and local communities. Their primary role is to extend healthcare services, thereby enhancing access and equity, which leads to improved individual and community health outcomes [4].

Uganda has implemented the CHWs/Village Health Team (VHT) program since 2001 and they are tasked with conducting health education, performing regular home visits, promoting hygiene and sanitation practices like hand washing, construction of pit latrines and encouraging boiling of drinking water, implementing integrated Community Case Management (iCCM) of childhood illnesses such as pneumonia, malaria and diarrhea, and referring patients to the nearest health facilities when necessary [5]. An assessment conducted in Uganda revealed that CHWs mobilize communities for public health interventions like immunization, fistula services, HIV/AIDS counselling and testing services, family planning, mobilizing pregnant women for antenatal care services, distribution of mosquito nets and mass distribution of neglected tropical diseases (NTD) drugs [6].

Despite their well-established role in community health, CHWs’ contribution to disease outbreak response remains undocumented. In Uganda, particularly in Masaka District, CHWs’ involvement in outbreak response, including yellow fever and COVID-19 outbreaks has not been systematically assessed. Several Non -Government Organizations (NGOs) support CHWs activities in Masaka District. For example, Program for Accessible Health Communication and Education (PACE) supports iCCM, Rakai Health Science Project (RHSP) and Uganda Cares focus on HIV/AIDS, while Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI) supports child immunization. Masaka has experienced multiple outbreaks, including yellow fever, African swine fever, and COVID-19. In April 2016, Masaka confirmed a yellow fever outbreak after three samples tested positive through polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and IgM antibody tests [7]. Another yellow fever outbreak was reported in March 2022, with one case tested positive for PCR [8]. In 2017 an outbreak of African swine fever led to the death of 300 pigs on a single farm in Masaka [9]. These events highlight the district’s vulnerability to infectious disease outbreaks and the potential role of CHWs in responding to them.

Although Masaka District Health Office (DHO) recognizes the contributions of CHWs and has emphasized the need for regular support supervision and performance reviews, systematic documentation of CHWs practices is lacking. This gap in knowledge is significant, as delayed reporting of suspected outbreaks may hinder timely response efforts, potentially exacerbating disease spread. Addressing this research gap is essential for informing policy and improving CHW capacity in epidemic preparedness and response. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the performance of CHWs in responding to yellow fever and COVID-9 outbreaks in Masaka District and to identify factors that facilitate or hinder their effectiveness.

Methods

Study area

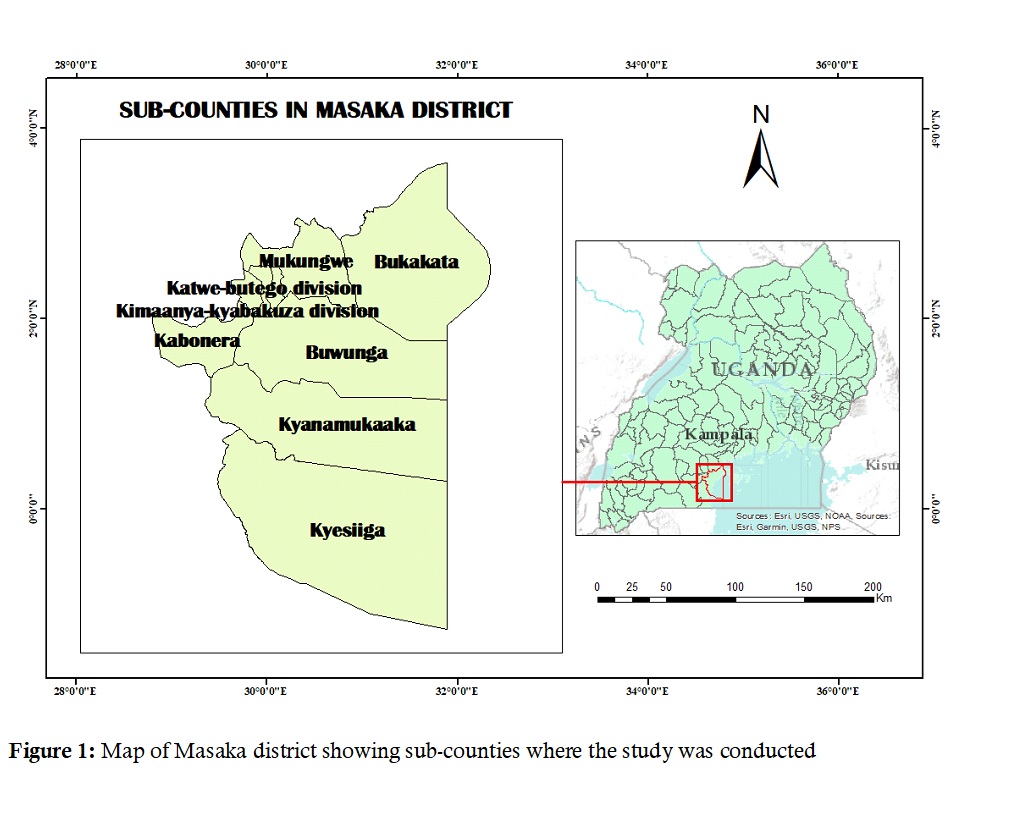

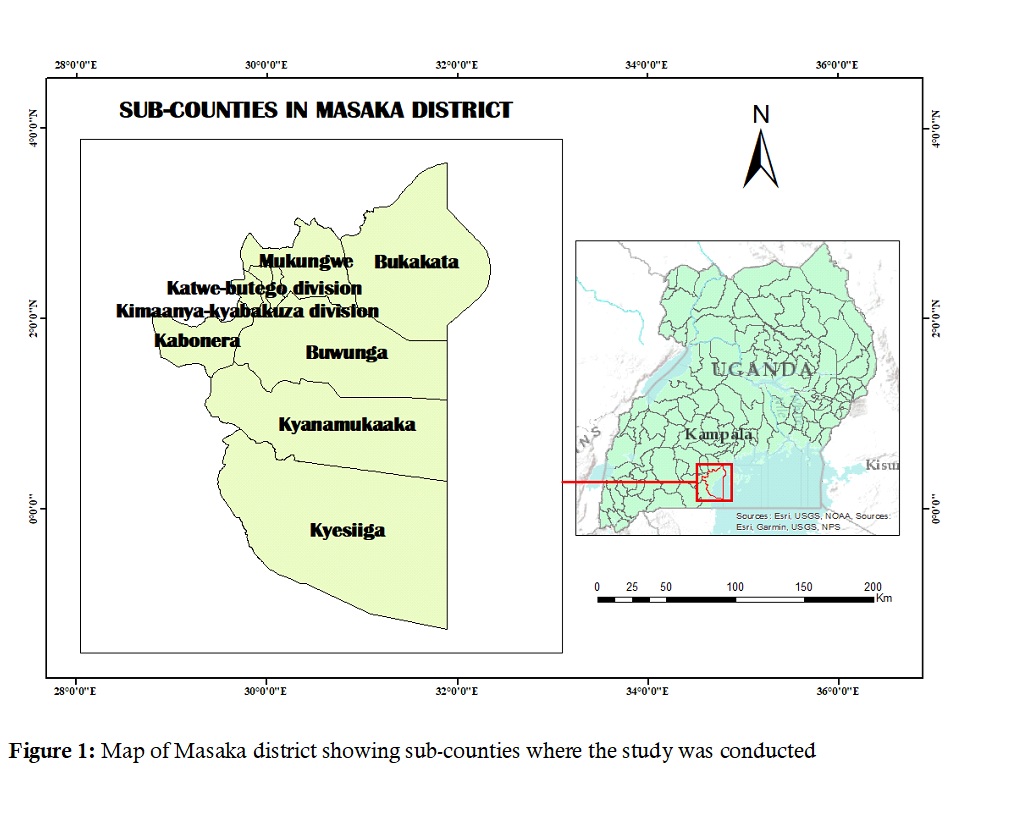

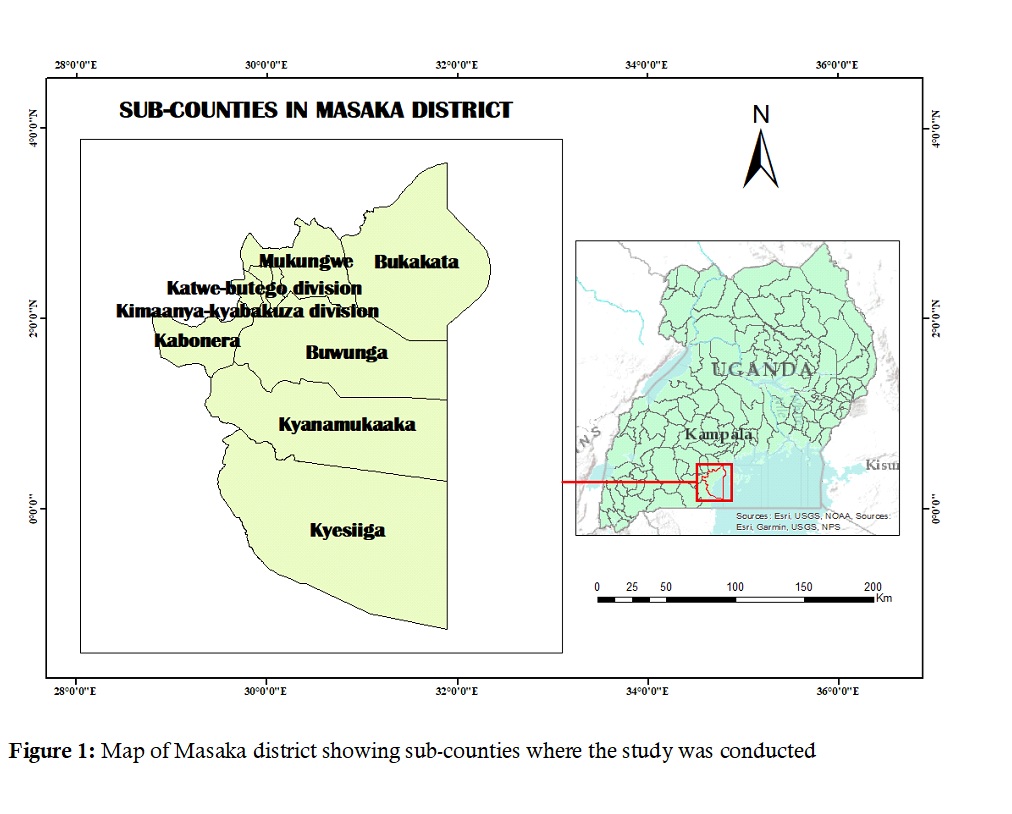

The study was conducted in Masaka District, Uganda from March to May 2022. Masaka District is located in central Uganda and serves as a major trade hub due to its proximity to the Mutukula border with Tanzania (Figure 1). This positioning exposes the district to increased disease transmission risks, particularly during public health crises like the COVID-19 pandemic. Masaka’s geographical characteristics further contribute to its vulnerability to disease outbreaks. The district has several landing sites along Lake Victoria where ships from Kalangala islands dock, attracting both fishing and non-fishing communities. This high level of population movement at landing sites, coupled with the district’s role as a rest stop for long-distance truck drivers, increases the risk of infectious disease outbreaks. By selecting Masaka District for this study, we aimed to explore CHW contributions in a setting with high mobility and outbreak risks, providing valuable insights into strengthening community-based outbreak response efforts.

Study design and population

This study employed a cross-sectional design using quantitative methods to assess the performance of CHWs in responding to yellow fever and COVID-19 outbreaks in Masaka District, Uganda. The outcome variable was CHW performance, categorized as high or low, based on their involvement in yellow fever and COVID-19 response activities.

The study included CHWs actively involved in disease outbreak response activities in Masaka District. CHWs function as Health Centre 1 (HC1) in Uganda’s health system. Each village has four CHWs, two assigned to the iCCM program (i.e., focused on childhood illnesses) and two engaged in general health promotion, including household sanitation. Masaka has 824 CHWs serving as a vital link between health facilities and the community.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included CHWs who were actively engaged in CHW activities at the time of data collection. Eligible participants were those involved in health education, disease surveillance, and outbreak response, ensuring they had direct experience relevant to the study’s objectives. Only CHWs who were available during the data collection period and willing to participate were included. Additionally, participants were required to have served as CHWs for at least six months, as this duration was considered sufficient to gain meaningful experience in their roles. CHWs were excluded if they were absent or unreachable during the data collection period, making it impossible to gather their inputs. Those who had served for less than six months were also excluded, as their limited experience may not provide adequate insights into their performance in disease outbreak response. Additionally, CHWs engaged in non-health related activities at the time of data collection were not included as their roles would not align with the study’s focus on outbreak response.

Sample size and sampling

We calculated the sample size using Kish Leslie’s formula for cross-sectional studies [12]. An estimated prevalence of 50% was considered as the expected performance of CHWs in responding to disease outbreaks because no literature has shown the percentage performance of CHWs in responding to disease outbreaks, a standard normal deviation at 95% confidence (1.96), and a 5% margin of error yielded a minimum sample size of 384.16 CHWs. Considering a non-response rate of 10%, a sample size of 427 was obtained for this study.

Participants were selected using stratified random sampling, where the study area was divided into nine sub-counties/divisions that formed Masaka District. After stratification, a random sample of CHWs proportionate to the population size was selected from each stratum.

Data collection methods and tools

We used a semi-structured questionnaire to collect data from CHWs. Data were collected using Kobo Collect software version 2021.2.4 installed on Android-enabled mobile phones. The questionnaire consisted of 50 questions covering socio-demographic characteristics and study objectives of determining the facilitators and barriers associated with the performance of CHWs in responding to yellow fever and COVID-19 outbreaks. Trained and experienced research assistants conducted the interviews under close supervision. The research assistants, three female and two males held diplomas in clinical medicine, nursing and environmental health sciences. They were trained in basic interviewing techniques, including neutrally phrasing questions, avoiding suggestive cues and accurately recording open-ended responses. Additionally, research assistants fluent in the local language facilitated accurate translation where necessary.

Study tools were developed using previous studies [13, 16]. Before the actual data collection commenced, the tools were pre-tested in Lwengo District, a nearby district, and the tools were edited following the pretesting exercise to improve their reliability and validity. To minimize bias, the interviewers received extensive training on conducting neutral and non-leading interviews, ensuring that questions were phrased in a way that did not influence respondents’ answers. Additionally, recall bias was mitigated by employing event anchoring techniques where respondents were asked to recall information about significant well-known local events to improve accuracy. Interviewers were also instructed to probe responses consistently without suggesting answers.

Interviews were conducted in a local language (Luganda) to accommodate participants who were not conversant with English. This approach ensured inclusivity while minimizing response biases that could arise due to language barrier. Each interview lasted between 10-15 minutes and data collection took place in March and April 2022. The data and data collection tools used are available upon reasonable request.

Data management and analysis

All data collected were uploaded to a secure server, downloaded into Excel and exported to STATA software version 2014 for analysis. Performance was measured using 10 questions generated from variables informed by the roles of CHWs as per the Uganda Ministry of Health guidelines [11] and existing literature, while scoring was guided by previous studies [13]. These indicators included contact tracing, community awareness on infection prevention and control, home visits, health education, and record keeping. CHWs with a score of six or more were categorized as having high performance, while those with a score below six were categorized as having low performance [13].

Descriptive analysis was conducted where continuous variables were summarized using mean, median and standard deviations while categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Inferential statistics were obtained using Poisson regression with robust standard errors in two stages. In the first stage, bivariate analysis was performed to determine the association between each independent variable and CHW performance in responding to yellow fever and COVID-19 outbreaks. Crude prevalence ratios (CPR) with 95% confidence intervals were generated to measure the strength of association. Variables with a p-value <0.05 in the bivariate analysis were considered for inclusion in the multivariable model. In addition, variables identified in the literature or through theoretical reasoning as potential confounders were also included to avoid excluding important factors that may not have appeared as statistically significant at the bivariate level.

In the second stage, multivariable poisson regression with robust error variance was used to estimate adjusted prevalence ratios (APR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. before inclusion in the final model, all variables were assessed for multicollinearity, and those with a correlation coefficient above 0.4 were excluded. A stepwise modeling approach was employed, and model fit was assessed using the goodness-of-fit statistic with a final value of 0.9958, indicating adequate fit.

Ethical considerations

We obtained ethical approval from the Makerere University, School of Public Health Higher Degrees Research and Ethics Committee (dated 19 January 2022). At the district level, administrative clearance to conduct the study was obtained from the District Health Officer. Permission was also obtained from the health facility in-charges where CHWs report, as well as from the local council I (LC1) Chairperson of each village. Informed consent was obtained from each participant at the start of the study. Participants were given the option to provide either written or verbal consent based on their preference and literacy level, ensuring voluntary participation while adhering to ethical standards. Confidentiality and anonymity were maintained by using coded numbers on the questionnaire instead of participant names and all collected data were securely stored with a password to prevent unauthorized access.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

Most 279 (65.3%) of the respondents were females, 325 (76.1%) of the respondents depended on agriculture as a source of income, and 337 (78.9%) lived in rural areas. Most 300 (70.2%) of the respondents were married, more than half 218 (51.1%) of the respondents had secondary and above education level, and 285 (66.7%) were Catholics (Table 1).

Performance of CHWs in responding to yellow fever and COVID-19 outbreaks

Most 320 (74.9%) of CHWs were categorized as high performers in responding to disease outbreaks. Almost all respondents 422 (98.8%) had carried out home visits in the previous 6 months, the median number of homes visited by CHWs prior to the month of data collection was 4, with an interquartile range (IQR) from 3(Q1) to 12(Q3). In the month preceding the study, the median number of household visited was 15, with an IQR from 8(Q1) to 40(Q3). Almost all respondents 422 (98.8%) had carried out community awareness on Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) of diseases prone to outbreaks, 258 (60.4%) possessed a register used to record cases identified in the community and more than half of respondents 147 (57.0%) had compiled and recorded the information from the register into the monthly reports (Table 2).

Factors associated with CHWs’ response to yellow fever and COVID-19 outbreaks

In bivariate analysis, the factors found to be significant were ever receiving training (CPR=1.30; 95% CI: [1.01-1.67]) and being given training materials (CPR=1.39; 95% CI: [1.16-1.66]). Monetary incentive (CPR= 1.35; 95% CI: [1.21-1.51]), appreciation/recognition (CPR= 1.57; 95% CI: [1.38-1.79]), provision of case reporting forms (CPR= 1.61; 95% CI: [1.45-1.79]), regular support supervision (CPR= 2.01; 95% CI: [1.51-2.68]), the provision of personal protective equipment (PPE) (CPR=1.53; 95% CI: [1.22-1.92]), provision of record books (CPR= 1.60; 95% CI: [1.46-1.75]), facilitating CHWs with airtime or prepaid calls to report cases/contacts (CPR= 1.37; 95% CI: [1.27-1.48]), health workers at health facilities acknowledging CHWs when they report cases or contacts (CPR= 1.77; 95% CI: [1.34-2.33]), more training (CPR=1.41; 95% CI: [1.26-1.58]) also significantly influenced CHW performance (Table 3).

Barriers associated with low performance included walking as the primary means of transport (CPR=0.69; 95% CI: [0.58-0.84]), sometimes refunded transport costs (CPR=0.72; 95% CI: [0.66-0.79]), never refunded transport costs (CPR=0.72; 95% CI: [0.64-0.81]) and shortage of PPEs (CPR=0.78; 95% CI: [0.71-0.86]) (Table 3).

After adjusting for confounding factors, several variables were significantly associated with CHWs performance in responding to yellow fever and COVID-19 outbreaks. CHWs whose supervisors organized support supervision meetings were 1.43 times more likely to perform compared to those without regular supervision (APR=1.43; 95% CI: [1.04-1.96]) (Table 4).

Provision of record books also influenced performance. CHWs who were provided with these record books were 1.23 times more likely to perform effectively compared to those who did not receive them (APR=1.23; 95% CI: [1.06-1.43]) (Table 4). Financial incentives played a crucial role, as CHWs who received a monetary incentive were 1.16 more likely to perform well than those who were not compensated (APR=1.16; 95% CI: [1.04-1.30]). (Table 4). Recognition by health workers at the health facility boosted CHW performance. Those who were acknowledged after reporting a case were 1.37 times more likely to perform effectively than those who were not recognized (APR=1.37; 95% CI: [1.02-1.85]). (Table 4). These findings highlight the importance of regular supervision, provision of necessary tools, financial incentives, training and recognition in enhancing CHW performance during yellow fever and COVID-19 outbreaks.

Discussion

We found that CHWs’ performance in responding to yellow fever and COVID-19 outbreaks was relatively high, with 74.9% categorized as having high performance. This finding indicates a strong capacity among CHWs to effectively engage in outbreak response activities, which is crucial in managing public health emergencies. The relatively high performance suggests that CHWs were able to fulfill their roles effectively, contributing to disease prevention and control efforts within their communities. It reflects their capacity to carry out essential tasks such as health education, community engagement, and disease surveillance which are vital in mitigating the spread of infectious diseases. The result underscores the importance of CHWs in public frameworks, particularly during outbreaks when timely and efficient responses are essential. High performance in this context can lead to improved health outcomes, increased community awareness, and greater overall effectiveness in managing public health crises.

Many CHWs engaged in community awareness efforts on infection prevention and control (IPC). The CHWs’ performance could be linked to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which emphasized the need for community protection. CHWs may have also been motivated by their close relationships with their communities, making them more committed to disease prevention efforts. Additionally, the timing of this study during the post-pandemic recovery phase could have contributed to higher recall of outbreak response activities among CHWs.

Several factors were associated with improved CHWs’ performance, including monetary and non-monetary incentives, training, supervision and recognition from health workers. CHWs who received monetary incentives performed better than those who did not. While financial compensation has been widely recognized as a key motivator, non-monetary incentives, such as airtime, training materials and PPE, also played a crucial role in enhancing performance. Conversely, barriers to performance included lack of monetary incentives, absence of refresher training, limited supervision, and inadequate reporting tools. These findings align with previous studies that highlight the importance of sustainable incentives in maintain CHW motivation and effectiveness [3]. Similarly, other findings have indicated that CHWs tend to perform better when they receive non-monetary incentives especially when it is considered reasonable, regular, and sustainable [16]. To optimize CHW contributions, stakeholders should ensure that both monetary and non-monetary incentives are provided in a structured and sustainable manner.

The absence of monetary incentives significantly affects CHWs’ motivation and productivity. Many CHWs operate in low-resource settings where they juggle multiple responsibilities, often relying on other income-generating activities to sustain their livelihoods. Without financial compensation, CHWs may deprioritize their healthcare duties, leading to reduced service delivery. When CHWs are financially unstable, their ability to focus on community health services diminishes, ultimately compromising the quality of healthcare provided.

Support supervision was another significant factor influencing CHW performance. Regular supervision provided guidance, early identification of challenges, and reinforcement of the best practices. CHWs who received support supervision were more likely to perform well, as engagement with supervision fostered accountability and motivation. These findings are consistent with studies from other settings which emphasized the role of supervision in improving CHW performance [17]. Effective supervision helps ensure that CHWs follow established protocols, deliver accurate health information, provide appropriate referrals, and receive the necessary support to navigate challenges in their work. When supervision is inadequate, CHWs may feel isolated, lack accountability, and struggle with job-related uncertainties. Supportive supervision, which includes mentorship, feedback, and problem-solving, has been shown to enhance CHWs’ motivation and job satisfaction. Regular supervision allows for the identification of gaps in service delivery and provides an opportunity for corrective action, ensuring that CHWs continue to deliver quality healthcare services. Without proper oversight, inconsistencies in service delivery may arise, leading to inefficiencies in community health programs. Therefore, health system stakeholders should ensure that CHWs attend regular supervision meetings to address challenges and enhance their performance.

Although the study did not specifically assess CHWs’ participation in village COVID-19 taskforces, their inclusion in these structures during the pandemic may help contextualize the observed levels of performance. The national community engagement strategy for COVID-19 emphasized that CHWs should be part of the village COVID-19 taskforces [18], potentially enhancing their involvement in community-based surveillance, case detection and referral services. This engagement could have contributed to increased motivation and improved response capacity during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, the financial facilitation provided to CHWs during the pandemic may have supported their sustained participation in disease prevention and response activities.

Our study identified key barriers affecting CHW performance as lack of training, inadequate PPE and absence of financial incentives hindered CHW performance. Training plays a crucial role in building capacity and ensuring CHWs have the necessary skills to conduct their responsibilities. While initial training equips CHWs with foundational knowledge and skills, continuous training is necessary to keep them updated on emerging health trends, new treatment protocols, and best practices. Without regular refresher courses, CHWs may experience knowledge gaps, reduced confidence in service delivery, and difficulty in managing complex cases. The absence of refresher training not only limits CHWs’ effectiveness but also affects their ability to adapt to changing healthcare needs. Limited access to PPE not only affected CHW performance but also posed a risk to their health and safety. These challenges reflect findings from other low-resource settings. For instance, a study conducted in Kenya, Uganda and Senegal reported that CHWs commonly lacked protective gear, regular stipends or salary, refresher training, work identification cards, and adequate supervision [15]. Similar barriers were observed in India, where the COVID-19 pandemic severely affected CHWs’ livelihood [19]. To address these challenges, stakeholders should prioritize regular refresher training, consistent provision of PPE and structured financial support to enhance CHW performance and resilience.

This study has some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, although our inclusion criteria ensured that only CHWs who were actively engaged in health education, disease surveillance and outbreak response were selected, the level of involvement in specific outbreaks particularly COVID-19 varied among participants. Those who had more or intensive engagement in the COVID-19 response may have had better recall of their roles during previous disease outbreaks, introducing potential recall bias. To minimize this bias, we used structured questionnaires with clearly defined reference periods and trained data collectors to probe responses consistently.

Secondly, the question on CHW performance during recent disease outbreaks may have introduced response bias, as many participants primarily reflected on routine activities such as drug distribution, iCCM, Immunization, antenatal follow-up and household sanitation areas where there were most frequently engaged. To minimize this, we provided context-specific examples and prompts during data collection to help participants distinguish between routine responsibilities and outbreak specific duties. Despite these limitations, we believe the study provides valuable insights into the factors influencing CHW performance during yellow fever and COVID-19 outbreaks.

Conclusion

CHW performance in responding to yellow fever and COVID-19 was relatively high, particularly in areas related to community awareness, IPC measures and case reporting. These findings underscore the critical role of CHWs as frontline responders in outbreak settings. The Ministry of Health should consider implementing structured financial and non-monetary incentives, such as stipends, transport refunds, training materials, and support supervision of CHWs. Additionally, providing essential reporting tools such as record books/registers and case reporting or investigation forms would improve documentation and follow-up of suspected cases.

Investing in periodic refresher training is also crucial as emerging and re-emerging diseases require CHWs to stay updated on case definitions and surveillance protocols. Strengthening CHW involvement in yellow fever and COVID-19 outbreak response through adequate support and resources will enhance their contributions to community health and epidemic preparedness.

What is already known about the topic

- CHWs are considered an integral part of the health system in achieving universal health coverage for all individuals at all times.

- Countries that have had episodes of epidemics have used CHWs to establish strong linkages with communities to win community trust and involvement in the fight against disease outbreaks. Community health workers play a significant role of linking communities to health facilities, participate in creating awareness about epidemic prevention, detect/identify and report suspected cases to the response team.

What this study adds

- This study documents the performance of CHWs in responding to disease outbreaks, which provides evidence for stakeholders to engage CHWs in disease outbreak response functional district surveillance systems.

- This study identified factors associated to CHWs’ performance in responding to disease outbreaks, which is useful information for the Ministry of Health and other stakeholders who engage CHWs in outbreak response.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of State’s Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator and Health Diplomacy (S/GAC), and President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) under Award Number 1R25TW011213. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.”

| Variable | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age of respondent (years): Mean 50.8 (SD±11.5), median 50 | ||

| 20–29 | 8 | 1.9 |

| 30–39 | 58 | 13.6 |

| 40 and above | 361 | 84.5 |

| Sex of respondent | ||

| Male | 148 | 34.7 |

| Female | 279 | 65.3 |

| Religion | ||

| Anglican | 58 | 13.6 |

| Catholic | 285 | 66.7 |

| Muslim | 53 | 12.4 |

| Pentecostal | 24 | 5.6 |

| SDA* | 7 | 1.6 |

| Marital status | ||

| Divorced/separated | 38 | 8.9 |

| Currently married | 300 | 70.2 |

| Never married | 31 | 7.3 |

| Widowed | 58 | 13.6 |

| Education level | ||

| Primary | 209 | 48.9 |

| Secondary and above | 218 | 51.1 |

| Occupation | ||

| Agriculture (subsistence farming, small-scale crop and livestock production) | 325 | 76.1 |

| Business (small-scale enterprises, trading, retail businesses and market vending) | 64 | 15.0 |

| Casual labourer | 6 | 1.4 |

| Civil servant | 15 | 3.5 |

| Housewife | 17 | 4.0 |

| Residence | ||

| Rural | 337 | 78.9 |

| Urban | 90 | 21.1 |

| Average monthly income (UGX)* | ||

| <20,000 | 89 | 20.8 |

| 20,000–100,000 | 214 | 50.2 |

| >100,000 | 124 | 29.0 |

| Total | 427 | 100 |

* SDA = Seventh-day Adventist; UGX = Ugandan Shillings

| Variable | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ever carried out home visits in the last 6 months | ||

| No | 5 | 1.2 |

| Yes | 422 | 98.8 |

| Ever conducted contact tracing/identification of suspected cases | ||

| No | 92 | 21.6 |

| Yes | 335 | 78.4 |

| Ever carried out community awareness on IPC* of diseases prone to outbreaks | ||

| No | 5 | 1.2 |

| Yes | 422 | 98.8 |

| Home visits conducted in a month (Median = 4; IQR = 3, 12) | ||

| <10 | 315 | 73.8 |

| >10 | 112 | 26.2 |

| Households visited in the previous month (Median = 15; IQR = 8, 40) | ||

| <10 | 164 | 38.4 |

| >10 | 263 | 61.6 |

| CHW carry out community health education | ||

| No | 13 | 3.0 |

| Yes | 414 | 97.0 |

| Health education sessions conducted in the previous month | ||

| None | 23 | 5.4 |

| <2 | 195 | 45.7 |

| >2 | 209 | 48.9 |

| CHWs possess a register used to record cases in the community | ||

| No | 169 | 39.6 |

| Yes | 258 | 60.4 |

| Register completely filled | ||

| No | 108 | 41.9 |

| Yes | 150 | 58.1 |

| Information from the register is compiled and recorded in the monthly reports | ||

| No | 111 | 43.0 |

| Yes | 147 | 57.0 |

| Total | 427 | 100 |

* IPC = Infection Prevention and Control

| Factors | CHW Performance | CPR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High (%) (n=320) | Low (%) (n=107) | |||

| Households CHW served | ||||

| <30HHs | 18 (5.6) | 23 (21.5) | Ref | |

| 30–50HHs | 46 (14.4) | 14 (13.1) | 1.75 (1.20–2.54) | 0.003 |

| >50HHs | 256 (80.0) | 70 (65.4) | 1.79 (1.26–2.54) | 0.001 |

| Ever been trained on roles in responding to disease outbreak | ||||

| Yes | 294 (91.9) | 89 (83.2) | 1.30 (1.01–1.67) | 0.042** |

| No | 26 (8.1) | 18 (16.8) | Ref | |

| Received any refresher training on disease outbreaks | ||||

| Yes | 234 (79.9) | 68 (75.6) | 1.06 (0.92–1.23) | 0.408 |

| No | 59 (20.1) | 22 (24.4) | Ref | |

| Always given training manuals (IEC materials) | ||||

| Yes | 263 (82.2) | 65 (60.7) | 1.39 (1.16–1.66) | 0.001** |

| No | 57 (17.8) | 42 (39.3) | Ref | |

| Supervisor(s) organize support supervision meetings | ||||

| Yes | 289 (91.2) | 60 (60.0) | 2.01 (1.51–2.68) | 0.001** |

| No | 28 (8.8) | 40 (40.0) | Ref | |

| Provision of PPEs | ||||

| Yes | 282 (88.1) | 72 (67.3) | 1.53 (1.22–1.92) | 0.001** |

| No | 38 (11.9) | 35 (32.7) | Ref | |

| Health workers accept CHW referrals | ||||

| Yes | 318 (99.4) | 103 (96.3) | Ref | |

| No | 2 (0.6) | 4 (3.7) | 2.27 (0.73–7.04) | 0.157 |

| Record book | ||||

| Yes | 174 (54.4) | 106 (99.1) | 1.60 (1.46–1.75) | 0.001** |

| No | 146 (45.6) | 1 (0.9) | Ref | |

| Case reporting forms | ||||

| Yes | 148 (46.3) | 100 (93.5) | 1.61 (1.45–1.79) | 0.001** |

| No | 172 (53.7) | 7 (6.5) | Ref | |

| Means of transport | ||||

| Bicycle/personal motorcycle | 31 (9.7) | 6 (5.6) | Ref | |

| Boda boda | 178 (55.6) | 21 (19.6) | 1.07 (0.92–1.24) | 0.392 |

| Walking | 111 (34.7) | 80 (74.8) | 0.69 (0.58–0.84) | 0.001** |

| Refunded transport cost | ||||

| Always refunded | 68 (22.6) | 1 (1.0) | Ref | |

| Sometimes refunded | 153 (50.8) | 62 (64.6) | 0.72 (0.66–0.79) | 0.001** |

| Never refunded | 80 (26.6) | 33 (34.4) | 0.72 (0.64–0.81) | 0.001** |

| What is refunded worth what CHW spend | ||||

| No | 232 (77.1) | 95 (99.0) | 1.39 (1.29–1.50) | 0.001** |

| Yes | 69 (22.9) | 1 (1.0) | Ref | |

| Monetary incentive | ||||

| Yes | 143 (44.7) | 80 (74.8) | 1.35 (1.21–1.51) | 0.001** |

| No | 177 (55.3) | 27 (25.2) | Ref | |

| Appreciation/recognition | ||||

| Yes | 108 (33.7) | 82 (76.6) | 1.57 (1.38–1.79) | 0.001** |

| No | 212 (66.3) | 25 (23.4) | Ref | |

| Improved supervision | ||||

| Yes | 89 (27.8) | 55 (51.4) | 1.32 (1.15–1.52) | 0.001** |

| No | 231 (72.2) | 52 (48.6) | Ref | |

| More training | ||||

| Yes | 181 (56.6) | 24 (22.4) | 1.41 (1.26–1.58) | 0.001** |

| No | 139 (43.4) | 83 (77.6) | Ref | |

| CHWs recognized by health workers | ||||

| Yes | 29 (9.1) | 35 (32.7) | 1.77 (1.34–2.33) | 0.001** |

| No | 292 (99.9) | 72 (67.3) | Ref | |

| CHWs facilitated with airtime/prepaid calls | ||||

| Yes | 254 (79.4) | 105 (98.1) | 1.37 (1.27–1.48) | 0.001** |

| No | 66 (20.6) | 2 (1.9) | ||

| Shortage of PPE | ||||

| Yes | 270 (84.4) | 103 (96.3) | 0.78 (0.71–0.86) | 0.001** |

| No | 50 (15.6) | 4 (3.7) | Ref | |

| Financial barriers | ||||

| Yes | 280 (87.5) | 64 (59.8) | 1.69 (1.34–2.12) | 0.001** |

| No | 40 (12.5) | 43 (40.2) | Ref | |

Note: **p<0.05; CHWs = Community Health Workers; PPE = Personal Protective Equipment; IEC = Information, Education and Communication materials; CPR = Crude Prevalence Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval

| Variable | CHW Performance | CPR (95% CI) | P-value | APR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High (%) (n=320) | Low (%) (n=107) | |||||

| Households CHW served | ||||||

| <30HHs | 18 (5.6) | 23 (21.5) | Ref | Ref | ||

| 30–50HHs | 46 (14.4) | 14 (13.1) | 1.75 (1.20–2.54) | 0.003 | 1.35 (0.98–1.88) | 0.069 |

| >50HHs | 256 (80.0) | 70 (65.4) | 1.79 (1.26–2.54) | 0.001 | 1.29 (0.95–1.75) | 0.100 |

| Ever been trained on roles in responding to a disease outbreak | ||||||

| Yes | 294 (91.9) | 89 (83.2) | 1.30 (1.01–1.67) | 0.042** | 0.87 (0.26–2.94) | 0.828 |

| No | 26 (8.1) | 18 (16.8) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Received any refresher training on responding to disease outbreak | ||||||

| No | 59 (20.1) | 22 (24.4) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 234 (79.9) | 68 (75.6) | 1.06 (0.92–1.23) | 0.408 | 0.96 (0.82–1.14) | 0.674 |

| Always given training manuals (IEC materials) | ||||||

| Yes | 263 (82.2) | 65 (60.7) | 1.39 (1.16–1.66) | 0.001** | 1.12 (0.92–1.36) | 0.264 |

| No | 57 (17.8) | 42 (39.3) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Supervisor(s) always organize support supervision meetings | ||||||

| Yes | 289 (91.2) | 60 (60.0) | 2.01 (1.51–2.68) | 0.001** | 1.43 (1.04–1.96) | 0.027** |

| No | 28 (8.8) | 40 (40.0) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Provision of PPEs to use while tracing suspected cases | ||||||

| Yes | 282 (88.1) | 72 (67.3) | 1.53 (1.22–1.92) | 0.001** | 1.09 (0.86–1.38) | 0.482 |

| No | 38 (11.9) | 35 (32.7) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Health workers at the health facility accept suspected case referrals from CHW | ||||||

| No | 2 (0.6) | 4 (3.7) | 2.27 (0.73–7.04) | 0.157 | 1.20 (0.70–2.08) | 0.504 |

| Yes | 318 (99.4) | 103 (96.3) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Record book | ||||||

| Yes | 174 (54.4) | 106 (99.1) | 1.60 (1.46–1.75) | 0.001** | 1.23 (1.06–1.43) | 0.007** |

| No | 146 (45.6) | 1 (0.9) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Case reporting forms | ||||||

| Yes | 148 (46.3) | 100 (93.5) | 1.61 (1.45–1.79) | 0.001** | 1.08 (0.94–1.25) | 0.257 |

| No | 172 (53.7) | 7 (6.5) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Means of transport | ||||||

| Bicycle/personal motorcycle | 31 (9.7) | 6 (5.6) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Boda boda | 178 (55.6) | 21 (19.6) | 1.07 (0.92–1.24) | 0.392 | 1.08 (0.95–1.23) | 0.213 |

| Walking | 111 (34.7) | 80 (74.8) | 0.69 (0.58–0.84) | 0.001** | 0.97 (0.82–1.14) | 0.684 |

| Always refunded the transport cost incurred to attend supervision meetings | ||||||

| Always refunded | 68 (22.6) | 1 (1.0) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Sometimes refunded | 153 (50.8) | 62 (64.6) | 0.72 (0.66–0.79) | 0.001** | 1.37 (1.01–1.86) | 0.042** |

| Never refunded | 80 (26.6) | 33 (34.4) | 0.72 (0.64–0.81) | 0.001** | 1.18 (0.89–1.56) | 0.263 |

| What is refunded worth what CHW spend | ||||||

| No | 232 (77.1) | 95 (99.0) | 1.39 (1.29–1.50) | 0.001** | 0.95 (0.65–1.39) | 0.795 |

| Yes | 69 (22.9) | 1 (1.0) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Monetary incentive | ||||||

| Yes | 143 (44.7) | 80 (74.8) | 1.35 (1.21–1.51) | 0.001** | 1.16 (1.04–1.30) | 0.011** |

| No | 177 (55.3) | 27 (25.2) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Appreciation/recognition | ||||||

| Yes | 108 (33.7) | 82 (76.6) | 1.57 (1.38–1.79) | 0.001** | 1.14 (1.00–1.30) | 0.058 |

| No | 212 (66.3) | 25 (23.4) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Improved supervision | ||||||

| Yes | 89 (27.8) | 55 (51.4) | 1.32 (1.15–1.52) | 0.001** | 0.90 (0.77–1.06) | 0.225 |

| No | 231 (72.2) | 52 (48.6) | Ref | Ref | ||

| More training | ||||||

| Yes | 181 (56.6) | 24 (22.4) | 1.41 (1.26–1.58) | 0.001** | 1.11 (0.95–1.29) | 0.175 |

| No | 139 (43.4) | 83 (77.6) | Ref | |||

| Health workers at health facilities recognize CHWs when they report cases/contacts | ||||||

| Yes | 29 (9.1) | 35 (32.7) | 1.77 (1.34–2.33) | 0.001** | 1.37 (1.02–1.85) | 0.037** |

| No | 292 (99.9) | 72 (67.3) | Ref | Ref | ||

| CHWs facilitated with airtime or prepaid calls to report cases or contacts | ||||||

| Yes | 254 (79.4) | 105 (98.1) | 1.37 (1.27–1.48) | 0.001** | 1.08 (0.82–1.42) | 0.602 |

| No | 66 (20.6) | 2 (1.9) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Shortage of PPE | ||||||

| Yes | 270 (84.4) | 103 (96.3) | 0.78 (0.71–0.86) | 0.001** | 0.96 (0.87–1.05) | 0.386 |

| No | 50 (15.6) | 4 (3.7) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Financial barriers | ||||||

| Yes | 280 (87.5) | 64 (59.8) | 1.69 (1.34–2.12) | 0.001** | 1.26 (0.98–1.62) | 0.073 |

| No | 40 (12.5) | 43 (40.2) | Ref | Ref | ||

Note: **p<0.05; CHWs = Community Health Workers; PPE = Personal Protective Equipment; IEC = Information Education Materials; CPR = Crude Prevalence Ratio; APR = Adjusted Prevalence Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval

References

- Ludwick T, Brenner JL, Kyomuhangi T, Wotton KA, Kabakyenga JK. Poor retention does not have to be the rule: retention of volunteer community health workers in Uganda. Health Policy Plan [Internet]. 2014 May;29(3):388-95. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/heapol/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/heapol/czt025 doi: 10.1093/heapol/czt025

- Mistry SK, Harris-Roxas B, Yadav UN, Shabnam S, Rawal LB, Harris MF. Community health workers can provide psychosocial support to the people during COVID-19 and beyond in low- and middle-income countries. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Jun 22 [cited 2025 Jun 24];9:666753. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2021.666753/full doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.666753

- Kok MC, Broerse JEW, Theobald S, Ormel H, Dieleman M, Taegtmeyer M. Performance of community health workers: situating their intermediary position within complex adaptive health systems. Hum Resour Health [Internet]. 2017 Sep 2 [cited 2025 Jun 24];15(1):59. Available from: https://human-resources-health.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12960-017-0234-z doi: 10.1186/s12960-017-0234-z

- Schneider H. The governance of national community health worker programmes in low- and middle-income countries: an empirically based framework of governance principles, purposes and tasks. Int J Health Policy Manag [Internet]. 2019 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Jun 24];8(1):18-27. Available from: http://www.ijhpm.com/article_3544.html doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.92

- Musoke D, Ndejjo R, Atusingwize E, Ssemugabo C, Ottosson A, Gibson L, et al. Panacea or pitfall? The introduction of community health extension workers in Uganda. BMJ Glob Health [Internet]. 2020 Aug [cited 2025 Jun 24];5(8):e002445. Available from: https://gh.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002445 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002445

- Ministry of Health (Uganda). National VHT assessment in Uganda report 2015 [Internet]. Kampala: Ministry of Health (Uganda); 2015 Mar [cited 2025 Jun 24]. Available from: https://library.health.go.ug/sites/default/files/resources/National%20VHT%20Assessment%20in%20Uganda%20Report%202015.pdf

- Kwagonza L, Masiira B, Kyobe-Bosa H, Kadobera D, Atuheire EB, Lubwama B, et al. Outbreak of yellow fever in central and southwestern Uganda, February–May 2016. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2018 Nov 3 [cited 2025 Jun 24];18(1):548. Available from: https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-018-3440-y doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3440-y

- World Health Organization. Yellow fever outbreak in Uganda 2022 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022 Apr 25 [cited 2025 Jun 24]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON367

- The Independent. African swine fever outbreak claims over 50 pigs [Internet]. Kampala: The Independent; 2022 Jan 9 [cited 2025 Jun 24]. Available from: https://www.independent.co.ug/african-swine-fever-outbreak-claims-over-50-pigs/

- Ministry of Health (Uganda). Community health extension workers policy [Internet]. Kampala: Ministry of Health (Uganda); 2018 Oct [cited 2025 Jun 25]. Available from: http://library.health.go.ug/sites/default/files/resources/CHEW%20Policy%20-%20November%20%202018-%20FOR%20CABINET-Final.pdf

- Ministry of Health (Uganda). Village health team: strategy and operational guidelines [Internet]. Kampala: Ministry of Health (Uganda), Health Education and Promotion Division; 2010 Mar [cited 2025 Jun 25]. Available from: http://library.health.go.ug/sites/default/files/resources/VHT-strategy-and-operational-guidelines.pdf

- Kish L. Survey sampling. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1965.

- Musoke D, Ndejjo R, Atusingwize E, Mukama T, Ssemugabo C, Gibson L. Performance of community health workers and associated factors in a rural community in Wakiso district, Uganda. Afr Health Sci [Internet]. 2019 Sep;19(3):2784-97. Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ahs/article/view/190940 doi: 10.4314/ahs.v19i3.55

- Shabani SS, Ezekiel MJ, Mohamed M, Moshiro CS. Knowledge, attitudes and practices on Rift Valley fever among agro pastoral communities in Kongwa and Kilombero districts, Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2015 Aug 21 [cited 2025 Jun 24];15:363. Available from: http://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-015-1099-1 doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1099-1

- Chengo R, Esho T, Kuria S, Kimani S, Indalo D, Kamanzi L, et al. A situation assessment of community health workers’ preparedness in supporting health system response to COVID-19 in Kenya, Senegal, and Uganda. J Prim Care Community Health [Internet]. 2022 Jan-Dec;13:21501319211073415. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/21501319211073415 doi: 10.1177/21501319211073415

- Bagonza J, Kibira SP, Rutebemberwa E. Performance of community health workers managing malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea under the community case management programme in central Uganda: a cross sectional study. Malar J [Internet]. 2014 Sep 18 [cited 2025 Jun 24];13:367. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1475-2875-13-367 doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-367

- Kuule Y, Dobson AE, Woldeyohannes D, Zolfo M, Najjemba R, Edwin BMR, et al. Community health volunteers in primary healthcare in rural Uganda: factors influencing performance. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2017 Mar 29 [cited 2025 Jun 24];5:62. Available from: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00062/full doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00062

- Ministry of Health (Uganda); Technical Inter-Sectoral Committee COVID-19 Community Engagement Strategy Sub-Committee. National community engagement strategy for COVID-19 response [Internet]. Kampala: Ministry of Health (Uganda); 2020 Sep 30 [cited 2023 May 14]. Available from: https://www.redcrossug.org/images/forms/National-Covid-19-Community-Engagement-Strategy-300920-V3.pdf

- Bhatia S, Pal S, Saha D. Challenges faced by community health workers in COVID-19 containment efforts [Internet]. New Delhi: Ideas for India; 2021 Aug 11 [cited 2025 Jun 24]. Available from: https://www.ideasforindia.in/topics/human-development/challenges-faced-by-community-health-workers-in-covid-19-containment-efforts.html

- Juma J, Fonseca V, Konongoi SL, Van Heusden P, Roesel K, Sang R, et al. Genomic surveillance of Rift Valley fever virus: from sequencing to lineage assignment. BMC Genomics [Internet]. 2022 Jul 18 [cited 2025 Jun 24];23(1):520. Available from: https://bmcgenomics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12864-022-08764-6 doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08764-6

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Tables

| Variable | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age of respondent (years): Mean 50.8 (SD±11.5), median 50 | ||

| 20–29 | 8 | 1.9 |

| 30–39 | 58 | 13.6 |

| 40 and above | 361 | 84.5 |

| Sex of respondent | ||

| Male | 148 | 34.7 |

| Female | 279 | 65.3 |

| Religion | ||

| Anglican | 58 | 13.6 |

| Catholic | 285 | 66.7 |

| Muslim | 53 | 12.4 |

| Pentecostal | 24 | 5.6 |

| SDA* | 7 | 1.6 |

| Marital status | ||

| Divorced/separated | 38 | 8.9 |

| Currently married | 300 | 70.2 |

| Never married | 31 | 7.3 |

| Widowed | 58 | 13.6 |

| Education level | ||

| Primary | 209 | 48.9 |

| Secondary and above | 218 | 51.1 |

| Occupation | ||

| Agriculture (subsistence farming, small-scale crop and livestock production) | 325 | 76.1 |

| Business (small-scale enterprises, trading, retail businesses and market vending) | 64 | 15.0 |

| Casual labourer | 6 | 1.4 |

| Civil servant | 15 | 3.5 |

| Housewife | 17 | 4.0 |

| Residence | ||

| Rural | 337 | 78.9 |

| Urban | 90 | 21.1 |

| Average monthly income (UGX)* | ||

| <20,000 | 89 | 20.8 |

| 20,000–100,000 | 214 | 50.2 |

| >100,000 | 124 | 29.0 |

| Total | 427 | 100 |

* SDA = Seventh-day Adventist; UGX = Ugandan Shillings

| Variable | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ever carried out home visits in the last 6 months | ||

| No | 5 | 1.2 |

| Yes | 422 | 98.8 |

| Ever conducted contact tracing/identification of suspected cases | ||

| No | 92 | 21.6 |

| Yes | 335 | 78.4 |

| Ever carried out community awareness on IPC* of diseases prone to outbreaks | ||

| No | 5 | 1.2 |

| Yes | 422 | 98.8 |

| Home visits conducted in a month (Median = 4; IQR = 3, 12) | ||

| <10 | 315 | 73.8 |

| >10 | 112 | 26.2 |

| Households visited in the previous month (Median = 15; IQR = 8, 40) | ||

| <10 | 164 | 38.4 |

| >10 | 263 | 61.6 |

| CHW carry out community health education | ||

| No | 13 | 3.0 |

| Yes | 414 | 97.0 |

| Health education sessions conducted in the previous month | ||

| None | 23 | 5.4 |

| <2 | 195 | 45.7 |

| >2 | 209 | 48.9 |

| CHWs possess a register used to record cases in the community | ||

| No | 169 | 39.6 |

| Yes | 258 | 60.4 |

| Register completely filled | ||

| No | 108 | 41.9 |

| Yes | 150 | 58.1 |

| Information from the register is compiled and recorded in the monthly reports | ||

| No | 111 | 43.0 |

| Yes | 147 | 57.0 |

| Total | 427 | 100 |

* IPC = Infection Prevention and Control

| Factors | CHW Performance | CPR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High (%) (n=320) | Low (%) (n=107) | |||

| Households CHW served | ||||

| <30HHs | 18 (5.6) | 23 (21.5) | Ref | |

| 30–50HHs | 46 (14.4) | 14 (13.1) | 1.75 (1.20–2.54) | 0.003 |

| >50HHs | 256 (80.0) | 70 (65.4) | 1.79 (1.26–2.54) | 0.001 |

| Ever been trained on roles in responding to disease outbreak | ||||

| Yes | 294 (91.9) | 89 (83.2) | 1.30 (1.01–1.67) | 0.042** |

| No | 26 (8.1) | 18 (16.8) | Ref | |

| Received any refresher training on disease outbreaks | ||||

| Yes | 234 (79.9) | 68 (75.6) | 1.06 (0.92–1.23) | 0.408 |

| No | 59 (20.1) | 22 (24.4) | Ref | |

| Always given training manuals (IEC materials) | ||||

| Yes | 263 (82.2) | 65 (60.7) | 1.39 (1.16–1.66) | 0.001** |

| No | 57 (17.8) | 42 (39.3) | Ref | |

| Supervisor(s) organize support supervision meetings | ||||

| Yes | 289 (91.2) | 60 (60.0) | 2.01 (1.51–2.68) | 0.001** |

| No | 28 (8.8) | 40 (40.0) | Ref | |

| Provision of PPEs | ||||

| Yes | 282 (88.1) | 72 (67.3) | 1.53 (1.22–1.92) | 0.001** |

| No | 38 (11.9) | 35 (32.7) | Ref | |

| Health workers accept CHW referrals | ||||

| Yes | 318 (99.4) | 103 (96.3) | Ref | |

| No | 2 (0.6) | 4 (3.7) | 2.27 (0.73–7.04) | 0.157 |

| Record book | ||||

| Yes | 174 (54.4) | 106 (99.1) | 1.60 (1.46–1.75) | 0.001** |

| No | 146 (45.6) | 1 (0.9) | Ref | |

| Case reporting forms | ||||

| Yes | 148 (46.3) | 100 (93.5) | 1.61 (1.45–1.79) | 0.001** |

| No | 172 (53.7) | 7 (6.5) | Ref | |

| Means of transport | ||||

| Bicycle/personal motorcycle | 31 (9.7) | 6 (5.6) | Ref | |

| Boda boda | 178 (55.6) | 21 (19.6) | 1.07 (0.92–1.24) | 0.392 |

| Walking | 111 (34.7) | 80 (74.8) | 0.69 (0.58–0.84) | 0.001** |

| Refunded transport cost | ||||

| Always refunded | 68 (22.6) | 1 (1.0) | Ref | |

| Sometimes refunded | 153 (50.8) | 62 (64.6) | 0.72 (0.66–0.79) | 0.001** |

| Never refunded | 80 (26.6) | 33 (34.4) | 0.72 (0.64–0.81) | 0.001** |

| What is refunded worth what CHW spend | ||||

| No | 232 (77.1) | 95 (99.0) | 1.39 (1.29–1.50) | 0.001** |

| Yes | 69 (22.9) | 1 (1.0) | Ref | |

| Monetary incentive | ||||

| Yes | 143 (44.7) | 80 (74.8) | 1.35 (1.21–1.51) | 0.001** |

| No | 177 (55.3) | 27 (25.2) | Ref | |

| Appreciation/recognition | ||||

| Yes | 108 (33.7) | 82 (76.6) | 1.57 (1.38–1.79) | 0.001** |

| No | 212 (66.3) | 25 (23.4) | Ref | |

| Improved supervision | ||||

| Yes | 89 (27.8) | 55 (51.4) | 1.32 (1.15–1.52) | 0.001** |

| No | 231 (72.2) | 52 (48.6) | Ref | |

| More training | ||||

| Yes | 181 (56.6) | 24 (22.4) | 1.41 (1.26–1.58) | 0.001** |

| No | 139 (43.4) | 83 (77.6) | Ref | |

| CHWs recognized by health workers | ||||

| Yes | 29 (9.1) | 35 (32.7) | 1.77 (1.34–2.33) | 0.001** |

| No | 292 (99.9) | 72 (67.3) | Ref | |

| CHWs facilitated with airtime/prepaid calls | ||||

| Yes | 254 (79.4) | 105 (98.1) | 1.37 (1.27–1.48) | 0.001** |

| No | 66 (20.6) | 2 (1.9) | ||

| Shortage of PPE | ||||

| Yes | 270 (84.4) | 103 (96.3) | 0.78 (0.71–0.86) | 0.001** |

| No | 50 (15.6) | 4 (3.7) | Ref | |

| Financial barriers | ||||

| Yes | 280 (87.5) | 64 (59.8) | 1.69 (1.34–2.12) | 0.001** |

| No | 40 (12.5) | 43 (40.2) | Ref | |

Note: **p<0.05; CHWs = Community Health Workers; PPE = Personal Protective Equipment; IEC = Information, Education and Communication materials; CPR = Crude Prevalence Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval

Table 3: Bivariate analysis of facilitators and barriers associated with CHWs Performance in response to Yellow fever and COVID-19 outbreaks, N = 427

Table 4: Multi-variable analysis of factors associated with CHWs Performance in response to Yellow fever and COVID-19 outbreaks, N=427

| Variable | CHW Performance | CPR (95% CI) | P-value | APR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High (%) (n=320) | Low (%) (n=107) | |||||

| Households CHW served | ||||||

| <30HHs | 18 (5.6) | 23 (21.5) | Ref | Ref | ||

| 30–50HHs | 46 (14.4) | 14 (13.1) | 1.75 (1.20–2.54) | 0.003 | 1.35 (0.98–1.88) | 0.069 |

| >50HHs | 256 (80.0) | 70 (65.4) | 1.79 (1.26–2.54) | 0.001 | 1.29 (0.95–1.75) | 0.100 |

| Ever been trained on roles in responding to a disease outbreak | ||||||

| Yes | 294 (91.9) | 89 (83.2) | 1.30 (1.01–1.67) | 0.042** | 0.87 (0.26–2.94) | 0.828 |

| No | 26 (8.1) | 18 (16.8) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Received any refresher training on responding to disease outbreak | ||||||

| No | 59 (20.1) | 22 (24.4) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 234 (79.9) | 68 (75.6) | 1.06 (0.92–1.23) | 0.408 | 0.96 (0.82–1.14) | 0.674 |

| Always given training manuals (IEC materials) | ||||||

| Yes | 263 (82.2) | 65 (60.7) | 1.39 (1.16–1.66) | 0.001** | 1.12 (0.92–1.36) | 0.264 |

| No | 57 (17.8) | 42 (39.3) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Supervisor(s) always organize support supervision meetings | ||||||

| Yes | 289 (91.2) | 60 (60.0) | 2.01 (1.51–2.68) | 0.001** | 1.43 (1.04–1.96) | 0.027** |

| No | 28 (8.8) | 40 (40.0) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Provision of PPEs to use while tracing suspected cases | ||||||

| Yes | 282 (88.1) | 72 (67.3) | 1.53 (1.22–1.92) | 0.001** | 1.09 (0.86–1.38) | 0.482 |

| No | 38 (11.9) | 35 (32.7) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Health workers at the health facility accept suspected case referrals from CHW | ||||||

| No | 2 (0.6) | 4 (3.7) | 2.27 (0.73–7.04) | 0.157 | 1.20 (0.70–2.08) | 0.504 |

| Yes | 318 (99.4) | 103 (96.3) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Record book | ||||||

| Yes | 174 (54.4) | 106 (99.1) | 1.60 (1.46–1.75) | 0.001** | 1.23 (1.06–1.43) | 0.007** |

| No | 146 (45.6) | 1 (0.9) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Case reporting forms | ||||||

| Yes | 148 (46.3) | 100 (93.5) | 1.61 (1.45–1.79) | 0.001** | 1.08 (0.94–1.25) | 0.257 |

| No | 172 (53.7) | 7 (6.5) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Means of transport | ||||||

| Bicycle/personal motorcycle | 31 (9.7) | 6 (5.6) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Boda boda | 178 (55.6) | 21 (19.6) | 1.07 (0.92–1.24) | 0.392 | 1.08 (0.95–1.23) | 0.213 |

| Walking | 111 (34.7) | 80 (74.8) | 0.69 (0.58–0.84) | 0.001** | 0.97 (0.82–1.14) | 0.684 |

| Always refunded the transport cost incurred to attend supervision meetings | ||||||

| Always refunded | 68 (22.6) | 1 (1.0) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Sometimes refunded | 153 (50.8) | 62 (64.6) | 0.72 (0.66–0.79) | 0.001** | 1.37 (1.01–1.86) | 0.042** |

| Never refunded | 80 (26.6) | 33 (34.4) | 0.72 (0.64–0.81) | 0.001** | 1.18 (0.89–1.56) | 0.263 |

| What is refunded worth what CHW spend | ||||||

| No | 232 (77.1) | 95 (99.0) | 1.39 (1.29–1.50) | 0.001** | 0.95 (0.65–1.39) | 0.795 |

| Yes | 69 (22.9) | 1 (1.0) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Monetary incentive | ||||||

| Yes | 143 (44.7) | 80 (74.8) | 1.35 (1.21–1.51) | 0.001** | 1.16 (1.04–1.30) | 0.011** |

| No | 177 (55.3) | 27 (25.2) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Appreciation/recognition | ||||||

| Yes | 108 (33.7) | 82 (76.6) | 1.57 (1.38–1.79) | 0.001** | 1.14 (1.00–1.30) | 0.058 |

| No | 212 (66.3) | 25 (23.4) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Improved supervision | ||||||

| Yes | 89 (27.8) | 55 (51.4) | 1.32 (1.15–1.52) | 0.001** | 0.90 (0.77–1.06) | 0.225 |

| No | 231 (72.2) | 52 (48.6) | Ref | Ref | ||

| More training | ||||||

| Yes | 181 (56.6) | 24 (22.4) | 1.41 (1.26–1.58) | 0.001** | 1.11 (0.95–1.29) | 0.175 |

| No | 139 (43.4) | 83 (77.6) | Ref | |||

| Health workers at health facilities recognize CHWs when they report cases/contacts | ||||||

| Yes | 29 (9.1) | 35 (32.7) | 1.77 (1.34–2.33) | 0.001** | 1.37 (1.02–1.85) | 0.037** |

| No | 292 (99.9) | 72 (67.3) | Ref | Ref | ||

| CHWs facilitated with airtime or prepaid calls to report cases or contacts | ||||||

| Yes | 254 (79.4) | 105 (98.1) | 1.37 (1.27–1.48) | 0.001** | 1.08 (0.82–1.42) | 0.602 |

| No | 66 (20.6) | 2 (1.9) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Shortage of PPE | ||||||

| Yes | 270 (84.4) | 103 (96.3) | 0.78 (0.71–0.86) | 0.001** | 0.96 (0.87–1.05) | 0.386 |

| No | 50 (15.6) | 4 (3.7) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Financial barriers | ||||||

| Yes | 280 (87.5) | 64 (59.8) | 1.69 (1.34–2.12) | 0.001** | 1.26 (0.98–1.62) | 0.073 |

| No | 40 (12.5) | 43 (40.2) | Ref | Ref | ||

Note: **p<0.05; CHWs = Community Health Workers; PPE = Personal Protective Equipment; IEC = Information Education Materials; CPR = Crude Prevalence Ratio; APR = Adjusted Prevalence Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval

Table 4: Multivariable analysis of factors associated with CHWs Performance in response to Yellow fever and COVID-19 outbreaks, N=427

Figures

Figure 1: Map of Masaka district showing sub-counties where the study was conducted

Keywords

- Community health workers

- Outbreak response

- Uganda