Outbreak Investigation | Open Access | Volume 8 (3): Article 55 | Published: 23 Jul 2025

Social investigation report of cVDPV2 outbreak in Dagahaley Refugee Camp, Dadaab Sub-County, Garissa County, Kenya, November 2021

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Google Scholar

Navigate this article

Tables

Table 1: Stool specimen of confirmed cVDPV2*, Dagahaley Refugee camp, June 2022

Table 1: Stool specimen of confirmed cVDPV2*, Dagahaley Refugee camp, June 2022 | |

Date 1st stool collection | 22/06/2021 |

Date 1st stool received by the lab | 26/06/2021 |

Viruses isolated | PV2 |

Genetic sequencing (nucleotide difference) | PV2 is Genetically linked to an environmental sample from Garissa and has been in circulation for 7 years. |

Table 1: Stool specimen of confirmed cVDPV2*, Dagahaley Refugee camp, June 2022

Table 2: Sociodemographic characteristics of under-five children by age and sex, Dagahaley Refugee camp and Dadaab host community, Garissa County, Kenya November 2021

Table 2: Sociodemographic characteristics of under-five children by age and sex, Dagahaley Refugee camp and Dadaab host community, Garissa County, Kenya November 2021 | ||

Age Group | Frequency(n=116) | Percentage (%) |

< 1 year | 21 | 18.10 |

≥1 year | 95 | 81. 90 |

Sex | ||

Male | 81 | 69.83 |

Female | 35 | 31.17 |

Table 2: Sociodemographic characteristics of under-five children by age and sex, Dagahaley Refugee camp and Dadaab host community, Garissa County, Kenya November 2021

Table 3: Field Investigation Selected Facilities and antigens administered in Dadaab Sub County –November, 2021

Table 3: Field Investigation Selected Facilities and antigens administered in Dadaab Sub County –November, 2021 | |||

Name of Facility | Antigen (Jan-Jun 2021) | ||

Variables | OPV1 | OPV3 | IPV |

Hagadera IRC Main Hospital | 76% | 68% | 68% |

Ifo Refugee Hospital | 61% | 52% | 52% |

Dagahaley MSF Main Hospital | 84% | 74% | 74% |

Dadaab Sub County Hospital | 100% | 90% | 90% |

Borehole 5 Dispensary | 86% | 82% | 82% |

Alinjugur Health Centre | 15% | 11% | 11% |

Labisigale Dispensary | 69% | 67% | 67% |

Table 3: Field Investigation Selected Facilities and antigens administered in Dadaab Sub County –November, 2021

Table 4: Types of Toilets used Dagahaley, Dadaab Sub-County, Garissa County, Kenya. November 2021

Table 4: Types of Toilets used Dagahaley, Dadaab Sub-County, Garissa County, Kenya. November 2021 | ||

Type of Toilet | Frequency (n=61) | Percentage (%) |

Pit Latrine | 54 | 88.5% |

Open defecation | 7 | 11.5% |

Table 4: Types of Toilets used Dagahaley, Dadaab Sub-County, Garissa County, Kenya. November 2021

Figures

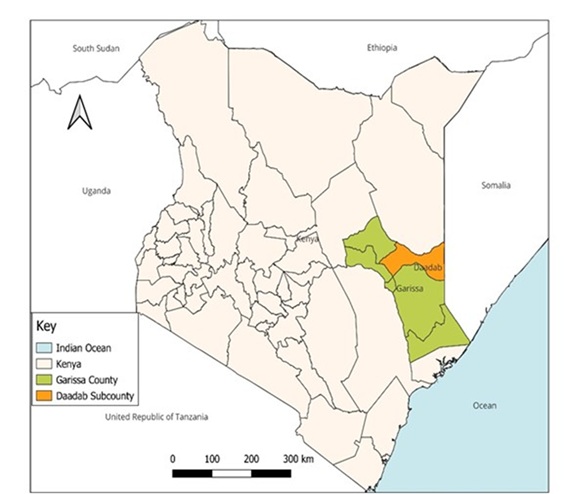

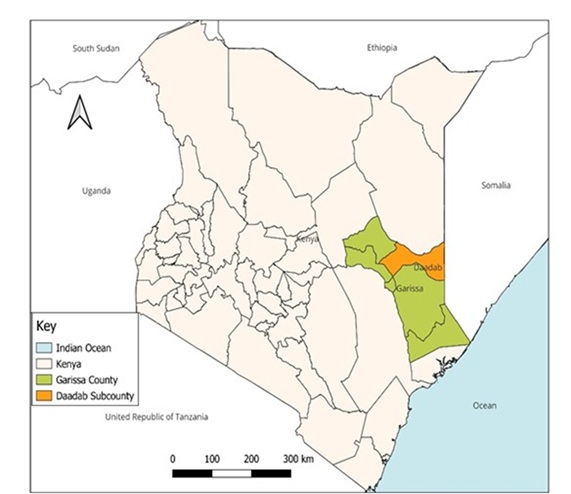

Figure 1: A Map showing Dadaab Sub-County, Garissa County, Kenya

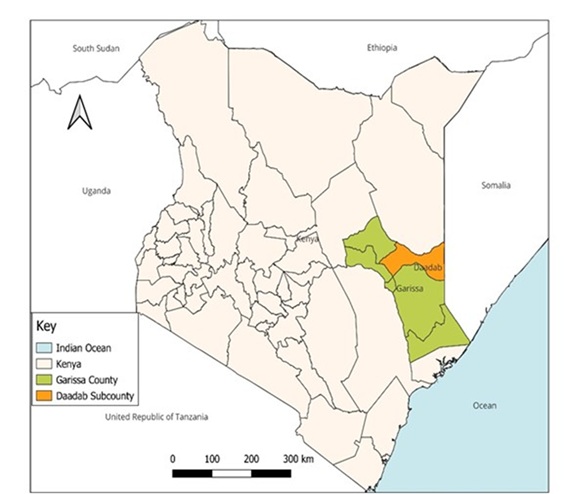

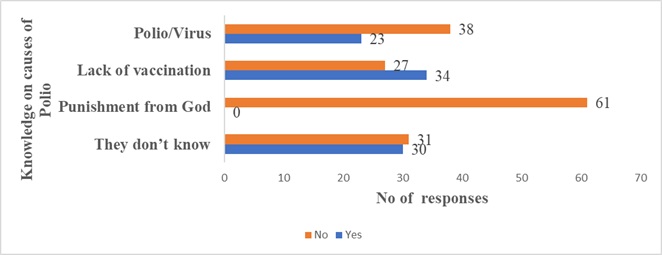

Figure 2: Knowledge of causes of polio, Dagahaley, Dadaab Sub-County, Garissa County

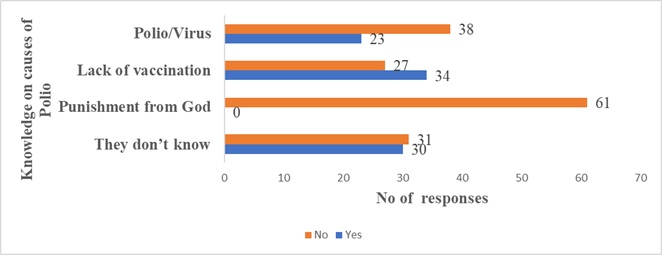

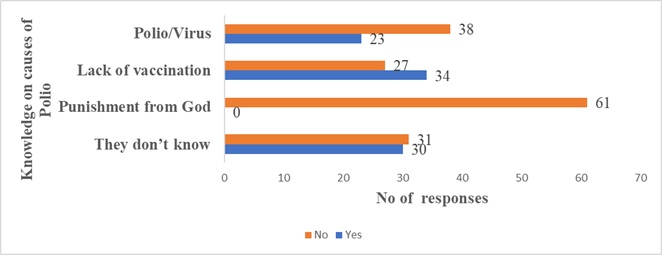

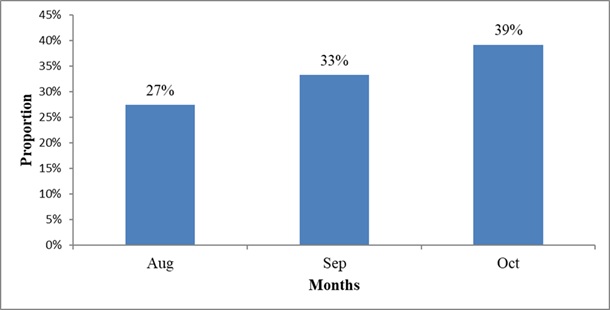

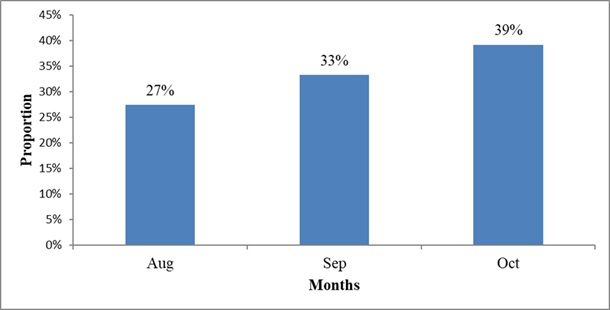

Figure 3: New Arrivals from Somalia to Kenya by Months 2021

Keywords

- Vaccination Coverage

- Paralysis

- Kenya

- Somalia

- Refugee Camps

- World Health Organization

Freshia Waithaka1,2,&, Fredrick Ngeno3, Hillary Limo2, Wickliffe Mattini2, Fredrick Odhiambo1, Maurice Owiny1

&Corresponding author: Freshia Waithaka, Kenya Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program, Ministry of Health, Kenya. Email: freshiwaithaka@gmail.com

Received: 12 Jul 2023, Accepted: 21 Jul 2025, Published: 23 Jul 2025

Domain: Outbreak Investigation, Polio Elimination

Keywords: Vaccination Coverage, Paralysis, Kenya, Somalia, Refugee Camps, World Health Organization

©Freshia Waithaka et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Freshia Waithaka et al. Social Investigation Report of cVDPV2 Outbreak in Dagahaley Refugee Camp, Dadaab Sub-County, Garissa County, Kenya, November 2021. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8(3):55. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph.2025.8.3.173

Abstract

Introduction: A 17-month-old female from Somalia was found positive for poliovirus type two, which was genetically linked to environmental samples from Garissa County that had been in circulation for seven years. We investigated the outbreak of an imported case from Somalia that occurred in the Dagahaley refugee camp to describe the epidemiology of the epidemic and identify the risk factors.

Methods: We conducted a descriptive field investigation, which included retrospective case searching, a health facility review in nine purposively selected health facilities, and household (HH) survey in 61 households (31 HHs in the camp and 30 HHs in the host community). Socio-demographic and clinical data were collected using the Open Data Kit. We defined a case as any person with poliovirus isolated in their stool. Data were analysed using descriptive statistics.

Results: The case was a 17-month-old female child who was a zero dose and had arrived with her mother from Somalia to visit a relative in Dagahaley camp. She had paralysis on the right upper and lower limbs. From August through October 2021, 51 children aged under five years arrived. In the refugee camp, 49/51 (96.1%) had not received first dose of Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV). Three facilities in the camp had less than 80% OPV3 and inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) coverage, while 7/61 (11.5%) families had no sanitation facilities and practiced open defecation.

Conclusion: Our investigation found that the unvaccinated child caused the cVDPV2 outbreak. The main concern is the high numbers of vulnerable populations who serve as a breeding ground for disease outbreaks and reservoirs for disease vectors. We recommended strengthening polio cross-border surveillance systems by utilising the existing structures and ensuring high vaccination coverage.

Introduction

Circulating Vaccine Derived Polio Viruses 2 (cVDPV 2) are rare; they are mutated viruses from the weakened virus in Oral Polio Vaccine, mainly occurring in under-immunized populations. Poliovirus outbreaks persist despite the Global Polio Eradication Initiative’s (GPEI) increased efforts to eradicate the poliovirus worldwide by a specific date [1–4]. Polio eradication strategy 2022–2026 Goal 2- seeks to stop cVDPV transmission and prevent outbreaks in non-endemic countries [3].

Globally, more than 90% of poliovirus outbreaks being experienced are caused by cVDPV type 2 (cVDPV2] [5]. In 2020, 959 cases occurred [6]; these outbreaks have set the hands of clock of polio and derailed the eradication efforts [7]. Africa has been experiencing increasing cVDPV2 outbreaks, which remain a challenge in 16 countries or at least 30 % of the African countries. The problem in these countries is not the vaccine but low vaccination coverage [8]. Kenya reported its last case of indigenous wild poliovirus (WPV) in 1984 but suffered from an outbreak of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2) on 6 April 2018. It has since been experiencing frequent outbreaks [9]. Garissa County, which borders Somalia, has undergone several polio outbreaks due to the influx of refugees with low population immunity.

Additionally, some parts of the county practice open defecation, which encourages the shedding of poliovirus into the environment, which is a breeding ground for the polio virus, given that polio is a fecal-oral route disease [7]. The Dadaab refugee camps recorded two cases of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus between May and July 2013 and two additional cases between February and June 2021. They all had a history of travel from Somalia. One element common to these outbreaks was proximity to the border areas between Kenya and its neighbouring country [7].

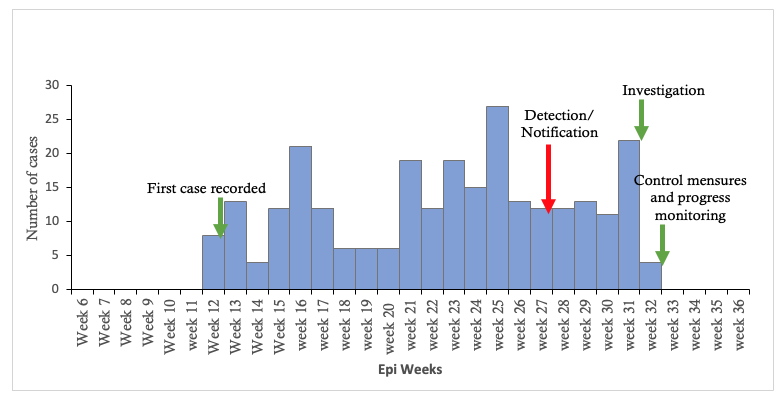

Outbreak notification and verification

The case was identified on 22 June 2021 by a Community Health Promoter (CHP) during a routine household visit and met the lay case definition for Acute Flaccid Paralysis (AFP), which is defined as any child who develops sudden weakness or paralysis in the leg (s) and arm (s) not caused by injury [10]. The child was referred to a health facility where the clinician suspected AFP. Two stool samples were collected and shipped to the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) polio laboratory, and on 26 June 2021, the laboratory isolated poliovirus. The Department of Health County government of Garissa notified the Division of Disease Surveillance and Response national team. WHO guidelines state that one confirmed case of cVDPV2 is an outbreak, and health authorities should initiate the investigation within 24 hours of a poliovirus isolate report [11]. A joint epidemiological and social investigation group comprising public health experts, sociologists, data experts, surveillance experts, and epidemiologists was constituted and deployed to Dadaab Sub-County from 22 through 27 November 2021. The investigation team aimed to conduct a case social investigation in line with the Global Polio Eradication Initiative – GPEI.

Methods

Field Settings

The study was conducted in the Dadaab sub-county, Garissa County which borders Somalia as shown in (Figure 1). The sub-county is one of the seven sub-counties in the county. It is subdivided into six wards: Abakaile, Dadaab, Labisigale, Damajaley, Dertu, and Liboi. According to the latest Census (2019), the Dadaab sub-county has a total population of 185,252 (Males 99,059, females 86,185) and 35,793 households [12]. The Sub County has 15 Public health facilities: one Sub-County hospital, four health centers, and ten dispensaries. The sub-county has 14 community units attached to different facilities. The average distance to the nearest health facility from the settlement areas is 10 to 30 km. The sub-county hosts the refugee camps. The polio virus case was hosted in Dagahaley refugee camp.

Dagahaley refugee camp is a rural setting established in 1992. An estimated 93,687 people live in this camp- two health posts and one central hospital. Currently, an estimated 1,000 households are living in the camp [13]. The main risk factor for the frequent outbreaks is the new incoming refugees from Somalia where immunization activities are low because of the security situation [14]. AFP Surveillance at the Dagahaley Refugee camp reporting and screening of new arrivals. Arrival at the camps is by road through informal routes while entry into the camps is mostly at night. Block leaders are informed immediately of the arrival and they alert the Community Health Promoters who visit the new arrivals, and initiate vaccination screening.

All children less than 15 years are screened for immunization status, documented, and referred to the health posts to receive the antigens. Stool samples are then collected for those who meet the following criteria: The child must be a new arrival, should be < 5 years and should have received less than three doses of OPV. If a child meets these criteria, the Sub County Disease Surveillance Coordinator and the Laboratory officer collects the stool samples before the antigens are administered. Routinely each camp should collect five samples spread throughout the month [15].

Field Participants

The field investigation participants were caregivers of eligible children aged 0 –59 months old from the Dagahaley refugee camp and the host community.

Field Investigation Design and Procedure

The field investigators conducted a detailed social investigation of the confirmed circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV2) case. The social investigation process is detailed below.

Conducting a detailed investigation of the case and contacts

The team interviewed the index case caregiver and collected socio-demographic information and caregivers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices on Polio. It also involved identification of any contacts.

Health facility survey to assess polio vaccination coverage (OPV and IPV) in selected health facilities

The investigation team conducted a health facility review in seven health facilities that were purposively selected. Two were from Dagahaley camp and the rest from the host community. In the health facility we reviewed data like (age, sex, diagnosis, history of travel, vaccination status) for six months of all under five children to assess polio vaccination coverage and identify any cases.

Immunization coverage was calculated by dividing the number of OPV and IPV administered among the eligible children by the number of targeted eligible children per facility multiplied by 100.

Household survey to identify any additional cases, determine OPV vaccination coverage and the social-cultural factors of the local population.

Active case search (ACS) was conducted in 61 households which had eligible children aged 0–59 months. Household survey tools were administered to 31 households in Dagahaley camp and 30 households in the host community using Open Data Kit (ODK) to collect socio-demographic and clinical data. A total of 116 children aged between 0–59 months were reached. Vaccination status of children in households visited was assessed by card and caregiver recall. Knowledge of the caregivers on the causes of polio, the type of latrines used in the households, and the travel history of the local community was also assessed.

Operational Definition

Social investigation is an activity wherein people or groups study how people in a community live. This includes their lifestyle, significant income, and other societal norms that could put them at risk of diseases [16]

Zero dose

A child who has not received even a single dose of any routine vaccine by the age of 12 months.

Case Definitions [10]

a) Lay case definition at the community level: Any child who develops sudden weakness or paralysis in the leg[s] and arm[s] not caused by injury.

b) Suspected: Any case with weakness or floppiness of the limbs of sudden onset not due to trauma in a child under 15 years of age or any person of any age in whom a clinician suspects polio.

c) Confirmed: A suspected case with poliovirus isolated from their stool sample.

Data collection

An Open Data Kit (ODK) was used as a data abstraction tool to collect variables from the interviewed caregivers and the selected health facilities. The collected variables included identifying information, knowledge of polio causes, type of toilets used, and the confirmed cVDPV2 case results. Data was uploaded into an Excel sheet after completing the survey.

Data analysis

Descriptive analysis was done to describe the confirmed case and the contacts that characterise them. Measures of central tendency and dispersion were analyzed for continuous variables, and frequency and proportions were calculated for categorical variables. Descriptive analysis was done to assess the vaccination coverage in the households and selected health facilities. Measures of central tendency and dispersion were analyzed for continuous variables, and frequency and proportions were calculated for categorical variables. The denominators for the children were 116, for the household it was 61, and seven for the selected health facilities. Maps were generated using QGIS version 3.24.1.

Ethical Consideration

Since the investigation was a response to a public health emergency, no ethical approval was sought from an Institutional Review and Ethics Committee (IREC). The Ministry of Health approved the protocol. The team obtained authorization to investigate from the County Director of Health, Garissa. Informed consent was obtained from all interviewees before the interviews. All personal identifications were excluded from the database before the analysis. The database was kept confidential and only used to answer the study’s objectives.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the confirmed cVDPV 2 case and the contacts cVDPV 2 Positive case social demographic information. On 26 June 2021, the case KEN-GAR-DAD-21-007 was reported; the child was a 17-month-old female child who had arrived with her mother from Somalia to visit a relative in Dagahaley camp (Block D4) on 21 June 2021. The child was a zero dose. The case was identified on 22 June 2021. The onset of paralysis/ weakness was on 12 May 2021 while in Somalia. The site of paralysis/weakness was the right upper and lower limbs. Two stool samples were collected and shipped to the KEMRI polio laboratory. The results showed that the confirmed case was genetically linked to an environmental sample picked from Garissa County and had been in circulation for seven years, as shown in (Table 1).

The results for the three contacts who were all under 5 aged 2, 2.6 and 4 years. Two were female and one male. One child from the hosting household and two contacts from neighbouring households sharing the same amenities like water and their parents often visited each other; their samples were negative. We interviewed 61 caregivers. The majority of the eligible children were males 81/116 (69.83 %), and at least one-year-old 95/116 (81.90%) (Table 2).

OPV and IPV vaccination coverage in households and selected health facilities

Sixty-one caregivers responded to the survey, with 116 children between 0–59 months reached during the immunisation coverage survey. Of the 116 children reached, those aged 12–59 months accounted for 95/116 (81.9%) while 0–11 months old were 21/116 (18.1%). The children who had a mother and child handbook/card were 75% (87/116).

Vaccination status of children in households visited by card and by a recall

- OPV≥3

- By card: 78/116 (67.24%) children had OPV ≥3 doses, and nine/116 (7.76%) children did not receive OPV≥3

- By recall: 10/116 (8.62%) children reported receiving OPV≥3 doses.

- IPV (is an injectable vaccine that protects the blood. It is given with the third dose of Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV) when your child is 3½ months old).

- By card: 78/116 (67.24 %) children had IPV doses, and nine/116 (7.76%) children did not receive IPV

- By recall: 10/116 (8.62%) children reported receiving an IPV dose

The overall coverage for the immunisation survey (OPV3 and IPV) was 77%.

Vaccination status of the new arrivals by antigen

Fifty-one under-five children had arrived from August through October 2021, of which majority 49/51 (96.1%) children had not received 1st dose of OPV, while none of the children had received IPV and MR vaccines.

Health Facility Review revealed that five facilities had OPV3 and IPV coverage of less than 80%, while the health facilities in the host community – Dadaab Hospital and Borehole 5 Dispensary achieved above 80% (Table 3).

The social-cultural factors of the local population

Sanitation-Majority of households shared pit latrines 54/61 (88.5%). 7/61 (11.5%) households had no sanitation facilities and practiced open defecation (Table 4).

Knowledge of Polio & OPV: The caregivers had little knowledge of the causes of polio. With 23/61(37.7%) stating that the cause of polio was a “virus,” while 34/61 (55.7%) said “lack of vaccination” was the cause (Figure 2).

Travel: The history of travel showed that there was a high influx of refugees from Somalia with an increase in the three months of August-14/51 (27%), September-17 (33%), and October-20 (39%) 2021- that were reviewed (Figure 3)

Discussion

The case described here represents a cVDPV2 outbreak; it was clinically suspected because of paralysis/weakness in the right upper and lower limbs. WHO recommends the collection of two adequate specimens within 14 days of the onset of paralysis and stool samples sent to a WHO-accredited polio laboratory. Thus, stool samples were collected and shipped to the KEMRI polio laboratory, which isolated the cVDPV 2 virus in the stool and confirmed the case. This shows laboratories’ crucial role in isolating different disease-causing organisms, including poliovirus. This conclusion is in line with a similar field investigation that cited the vital role of the laboratory in AFP surveillance. Additionally, laboratory surveillance is one of the four main objectives of the World Health Organization’s Polio Eradication & Endgame Strategic Plan 2013-2018 [4]. The continuous cVDPV2 outbreaks are a significant threat to the Polio Eradication Strategy 2022–2026 second goal: to stop cVDPV2 transmission and prevent outbreaks in non-endemic countries, of which Kenya is one of them [3] [17].

High routine coverage with at least three doses of oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV3) has been the foundation of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative [18]. However, four facilities had less than 80% OPV3 and IPV coverage. This might be due to the frequent influx of refugees in the camp who have a very low percentage of vaccination status, hence the need to strengthen the surveillance of AFP cases to detect any new virus importation rapidly and to facilitate a rapid response; a similar field investigation showed that immunization plays an essential role in preventing transmission [4]. No missed children were found during house-to-house case searches and from the in-depth inquiry of families and communities.

Our study found that Community Health Promoters (CHPs) have a high level of knowledge regarding the signs and symptoms of the disease and are proactive in reporting to the health system. This was evidenced by one CHP identifying and documenting a suspected case during a routine household visit.” This points out the critical role Community Health Promoters play in early disease detection and the linkage between the community and the health facilities. These findings agree with a field investigation carried out in Uganda that highlighted the critical roles Community Health Promoters played in disease prevention in those under five due to early detection [19]; however, most of the community members and refugees had insufficient knowledge of the causes of AFP.

Polio is an oral-fecal disease; therefore, open defecation cannot be separated from the perennial polio outbreaks [15]. Some parts of the refugee camp practiced open defecation. This investigation is in line with a similar field investigation carried out in many countries of Africa, which showed open defecation being persistent in the periphery of most towns and cities. [20]. These findings agree with findings from India, which showed that poor sanitation contributes to the spread of poliovirus [21]. Another finding showed the risk of infectious disease outbreaks increases in the refugee camp due to factors such as overcrowding and compromised hygiene and sanitation [22].

Our findings noted significant travel history from Somalia to the refugee camp; the increase in new arrivals from August through October backed this. Additionally, the case was an importation from Somalia. Most of the under-five children who had arrived had not received the first dose of the OPV vaccine. This points out the threat that Kenya faces due to the frequent influx of refugees from neighboring countries with low immunization coverage and the need for cross-border surveillance to prevent the polio virus importation. These findings agree with similar studies conducted in Ethiopia that indicated that the country remains at risk of reinfection because of the importation of poliovirus from polio outbreaks bordering countries [23].

Limitations

The caregivers who did not have the MCH immunization booklet relied on recall which could have led to under or over-estimation of vaccination status due to recall bias. The confirmed cVDPV2 case had returned to Somalia by the time of the investigation, so it relied on secondary information from the hosting relative, which could be limited.

Conclusion

Based on the detailed cVDPV2 virus case assessment, OPV vaccination coverage, and social-cultural factors findings, the investigation team concluded that the clinical presentation of the case was compatible with poliovirus infection, which was an importation from Somalia, there was no community transmission since all the contact samples were negative. This importation poses a significant threat to the Global Polio Eradication Initiative’s goal two: to stop cVDPV2 transmission and prevent outbreaks in non-endemic countries, of which Kenya is one of them.

Recommendations

Upscale routine immunization services in all service delivery points, including refugee camps, continuous active AFP surveillance, and conducting community sensitization on the causes of AFP through the already established structures. Additionally, we recommend additional research on strengthening cross-border surveillance between Kenya and Somalia to prevent subsequent outbreaks. Since the child has returned to Somalia, we recommend that the polio eradication initiatives (PEI) team in Kenya notify their Somalia counterpart and follow up on the case, mainly because of the continuous shedding of the virus, which can contaminate the environment.

What is already known about the topic

- Circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses (cVDPVs) can emerge in settings with low poliovirus immunity and can cause paralysis [14].

What this study adds

- Our investigation provides concrete evidence that cross-border surveillance is key in preventing transmission and transmission of imported

Authors´ contributions

FWW, FN, HL, and WM conceived, planned, and carried out this research. FWW and FN jointly conducted all quantitative analyses. FWW and FN participated in preparing the first draft. FO and MO reviewed and critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors contributed substantially to the review and revision of the manuscript.

|

Table 1: Stool specimen of confirmed cVDPV2*, Dagahaley Refugee camp, June 2022 |

|

|

Date 1st stool collection |

22/06/2021 |

|

Date 1st stool received by the lab |

26/06/2021 |

|

Viruses isolated |

PV2 |

|

Genetic sequencing (nucleotide difference) |

PV2 is Genetically linked to an environmental sample from Garissa and has been in circulation for 7 years. |

Table 2: Sociodemographic characteristics of under-five children by age and sex, Dagahaley Refugee camp and Dadaab host community, Garissa County, Kenya November 2021 | ||

Age Group | Frequency(n=116) | Percentage (%) |

< 1 year | 21 | 18.10 |

≥1 year | 95 | 81. 90 |

Sex | ||

Male | 81 | 69.83 |

Female | 35 | 31.17 |

Table 3: Field Investigation Selected Facilities and antigens administered in Dadaab Sub County –November, 2021 | |||

Name of Facility | Antigen (Jan-Jun 2021) | ||

Variables | OPV1 | OPV3 | IPV |

Hagadera IRC Main Hospital | 76% | 68% | 68% |

Ifo Refugee Hospital | 61% | 52% | 52% |

Dagahaley MSF Main Hospital | 84% | 74% | 74% |

Dadaab Sub County Hospital | 100% | 90% | 90% |

Borehole 5 Dispensary | 86% | 82% | 82% |

Alinjugur Health Centre | 15% | 11% | 11% |

Labisigale Dispensary | 69% | 67% | 67% |

Table 4: Types of Toilets used Dagahaley, Dadaab Sub-County, Garissa County, Kenya. November 2021 | ||

Type of Toilet | Frequency (n=61) | Percentage (%) |

Pit Latrine | 54 | 88.5% |

Open defecation | 7 | 11.5% |

References

- Deblina Datta S, Tangermann RH, Reef S, William Schluter W, Adams A. National, regional and global certification bodies for polio eradication: a framework for verifying measles elimination. The Journal of Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2017 Jul 1 [cited 2025 Jul 21];216(suppl_1):S351–4. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/216/suppl_1/S351/3935049 https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiw578

- Polio Global Eradication Initiative. Polio Endgame Strategy 2019- 2023: Eradication, integration, certification and containment [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2023 [cited 2025 Jul 21]. 55 p. Document Number: WHO/Polio/19.04. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/329948/WHO-Polio-19.04-eng.pdf

- Polio Global Eradication Initiative. Delivering on a Promise: Polio Eradication Strategy 2022–2026: Pre-publication version, as of 10 June 2021 [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2021 [cited 2025 Jul 21]. 81 p. Available from: https://polioeradication.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/polio-eradication-strategy-2022-2026-pre-publication-version-20210609.pdf

- Booth T, Grudeski E, McDermid A, Rotondo J. The polio eradication endgame: Why immunization and continued surveillance is critical. CCDR [Internet]. 2015 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Jul 21];41(10):233–40. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/migration/phac-aspc/publicat/ccdr-rmtc/15vol41/dr-rm41-10/assets/pdf/ccdrv41i10a03-eng.pdf https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v41i10a03

- Greene SA. Progress toward polio eradication — worldwide, January 2017–March 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2019 May 24 [last reviewed 2019 May 23; cited 2025 Jul 21];68(20):458–462. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6820a3.htm http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6820a3

- Cooper LV, Bandyopadhyay AS, Gumede N, Mach O, Mkanda P, Ndoutabé M, Okiror SO, Ramirez-Gonzalez A, Touray K, Wanyoike S, Grassly NC, Blake IM. Risk factors for the spread of vaccine-derived type 2 polioviruses after global withdrawal of trivalent oral poliovirus vaccine and the effects of outbreak responses with monovalent vaccine: a retrospective analysis of surveillance data for 51 countries in Africa. The Lancet Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2021 Oct 11 [cited 2025 Jul 21];22(2):284–94. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1473309921004539 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00453-9

- Nwogu C, Musyoka J, Gathenji C, Nzunza R, Onuekwusi I, Okeibunor J, Mkanda P, Shukla H, Humayun Kabir S, O Okiror S. Overview of polio outbreak response in Kenya, 2013 to 2015. J Immunol Sci [Internet]. 2020 Nov 19 [cited 2025 Jul 21];Special Issue(2):3–11. Available from: https://www.immunologyresearchjournal.com/articles/overview-of-polio-outbreak-response-in-kenya-2013-to-2015.html https://doi.org/10.29245/2578-3009/2021/S2.1103

- Pandey K. Africa eradicates polio, but vaccine-driven outbreaks rise [Internet]. New Delhi (India): Down To Earth; 2020 Aug 27 [cited 2025 Jul 21]. [about 13 screens]. Available from: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/africa/africa-eradicates-polio-but-vaccine-driven-outbreaks-rise-73080

- Tesfaye B, Sowe A, Kisangau N, Ogange J, Ntoburi S, Nekar I, Muitherero C, Camara Y, Gathenji C, Langat D, Sergon K, Limo H, Nzunza R, Kiptoon S, Kareko D, Onuekwusi I. An epidemiological analysis of Acute Flaccid Paralysis (AFP) surveillance in Kenya, 2016 to 2018. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2020 Aug 18 [cited 2025 Jul 21];20(1):611. Available from: https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-020-05319-6 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05319-6

- Poliomelytis [Internet]. Washington (DC): PAHO; [cited 2022 Jul 23]. [about 6 screens]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/en/topics/poliomyelitis

- Polio Global Eradication Initiative. Guidelines for Investigating a Polio outbreak or AFP case clustering [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): PGEI; [cited 2025 Jul 21]. [about 4 pages]. Available from: https://www.poliokit.org/sites/default/files/migrate/AFP_Case_Clustering.pdf

- UN HABITAT. Programs: Five flagship programs for a decade of action on the sustainable development goals [Internet]. c2012-2025 [cited 2025 Jul 21]. [about 5 screens]. Available from: https://unhabitat.org/programme/

- Dagahaley Camp Profile, Dadaab Refugee Camps, Kenya [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): UNHCR; 2015 Mar 15 [cited 2022 Jul 23]. [about 4 p.]. Available from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/32021 Download PDF to view full text.

- UN News. Polio outbreak in refugee complex in Kenya being contained, say UN agencies [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): UN; 2013 May 31 [cited 2025 Jul 21]. Available from: https://news.un.org/en/story/2013/05/441072

- CORE Group. Orientation on Disease Surveillance for Health Care Providers [Internet]. Washington (DC): Core Group; 2016 [cited 2025 Jul 21]. 40 p. Available from: https://coregroup.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Orientation-on-Disease-Surveillance-for-Health-Care-Providers.pdf

- Burr V, Dick P. Social constructionism. In: Gough B, editor. The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Social Psychology [Internet]. London (England): Palgrave Macmillan; 2017 Apr 12 [cited 2025 Jul 21]. p. 59–80. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1057/978-1-137-51018-1_4 https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-51018-1_4 Subscription or purchase required to view full text.

- Tangermann RH, Lamoureux C, Tallis G, Goel A. The critical role of acute flaccid paralysis surveillance in the Global Polio Eradication Initiative. International Health [Internet]. 2017 Jun 3 [cited 2025 Jul 21];9(3):156–63. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/inthealth/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/inthealth/ihx016 https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihx016

- Global Polio Eradication Initiative Strategic Plan 2004- 2008 [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2004 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Jul 21]. 40 p. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/42850/924159117X.pdf;sequence=1 Download PDF to view full text

- Singh D, Cumming R, Mohajer N, Negin J. Motivation of Community Health Volunteers in rural Uganda: the interconnectedness of knowledge, relationship and action. Public Health [Internet]. 2016 Feb 11 [version of record 2016 Jun 29; cited 2025 Jul 21]; 136:166–71. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0033350616000135 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2016.01.010 Subscription or purchase required to view full text.

- Open Defecation: India’s Health Hazard of the Poor [Internet]. BORGEN Magazine; 2014 May 23 [cited 2025 Jul 21]:[about 6 screens]. Available from: https://www.borgenmagazine.com/open-defecation-indias-health-hazard-poor/#:~:text=Open%20defecation’s%20link%20to%20global,work%20and%20provide%20for%20themselves.

- Lien G, Heymann DL. The problems with polio: toward eradication. Infect Dis Ther [Internet]. 2013 Sep 17 [cited 2025 Jul 21];2(2):167–74. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s40121-013-0014-6 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-013-0014-6

- Habib J. Communicable Disease in Humanitarian Emergencies: Polio Outbreak Syria [Internet]. Nairobi (Kenya): The Communication Initiative; 2013 Nov 11 [cited 2022 Jul 28]. Available from: https://global.comminit.com/content/communicable-disease-humanitarian-emergencies-polio-outbreak-syria

- Bisrat F, Kidanel L, Abraha K, Asres M, Dinku B, Conlon F, Fantahun M. Cross-border wild polio virus transmission in CORE Group Polio Project areas in Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J [Internet]. 2013 Jul [cited 2025 Jul 21];51( Suppl 1):31–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24380205/ Abstract only.