Research | Open Access | Volume 8 (3): Article 62 | Published: 08 Aug 2025

Evaluating the effectiveness of chlorhexidine digluconate 7.1% in comparison to alternative cord care practices in Kiambu County, Kenya: A cross-sectional study on neonatal outcomes

Menu, Tables and Figures

Navigate this article

Tables

Table 1: The socio-demographic characteristics of the mothers recruited from both public and private health facilities in this study, with a breakdown of demographics from public and private facilities.

| Variable | Total N = 434, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 15–24 | 167 (38.5%) |

| 25–34 | 224 (51.6%) |

| 35–44 | 43 (9.9%) |

| Level of Education Attained | |

| Primary school | 70 (16.1%) |

| Secondary school | 205 (47.2%) |

| College | 117 (27.0%) |

| University | 42 (9.7%) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 87 (20.1%) |

| Married | 334 (77.0%) |

| Divorced or separated | 10 (2.3%) |

| Widowed | 3 (0.7%) |

| Occupation | |

| Unemployed | 208 (47.9%) |

| Employed | 76 (17.5%) |

| Self-employed | 150 (34.6%) |

| ANC attendance | |

| Attended ANC | 415 (95.6%) |

| Did not attend ANC | 19 (4.4%) |

| Attending Hospital Level | |

| Level 3 | 28 (18.7%) |

| Level 4 | 102 (11.3%) |

| Level 5 | 304 (70.1%) |

| Delivery Place | |

| Health centre/dispensary | 67 (15.4%) |

| Hospital | 367 (84.6%) |

| Issued with CHX | |

| Yes | 94 (21.7%) |

| No | 340 (78.3%) |

| Given CHX Prescription (n=340) | |

| Yes | 132 (38.8%) |

| No | 208 (61.2%) |

| CHX bought after prescription (n=132) | |

| Yes | 86 (63.6%) |

| No | 46 (34.8%) |

| Prior use of CHX | |

| Yes | 54 (12.4%) |

| No | 380 (87.6%) |

Table 1: The socio-demographic characteristics of the mothers recruited from both public and private health facilities in this study, with a breakdown of demographics from public and private facilities.

Table 2: The cord care outcomes of all the mothers in the study compared with variables concerning maternal choices in cord care practices

| Variables | Cord-care outcome Healed | Cord-care outcome Not Healed | Crude OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provided CHX | ||||

| Yes | 90 (21.74%) | 4 (20.00%) | Ref | |

| No | 324 (78.26%) | 16 (80.00%) | 0.90 (0.25–2.53) | 0.8537 |

| Uptake CHX | ||||

| Yes | 166 (40.10%) | 12 (60.00%) | Ref | |

| No | 248 (59.90%) | 8 (40.00%) | 2.24 (0.91–5.83) | 0.0842 |

| Prior use CHX | ||||

| Yes | 50 (12.08%) | 4 (20.00%) | Ref | |

| No | 364 (87.92%) | 16 (80.00%) | 1.82 (0.51–5.20) | 0.301 |

| Cord-care used | ||||

| CHX | 166 (40.10%) | 12 (60.00%) | Ref | |

| Alternate | 248 (59.90%) | 8 (40.00%) | 2.24 (0.90–5.83) | 0.0842 |

Table 2: The cord care outcomes of all the mothers in the study compared with variables concerning maternal choices in cord care practices

Table 3: Association Between Chlorhexidine (CHX) Use and Cord-Care Outcomes

| Variable | Cord-Care Outcome | Crude OR (95% CI) | P-Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place Provided CHX | |||||

| Maternity (Ref) | 82 (49.40%) Healed, 3 (25.00%) Not Healed | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Bought Outside Facility | 75 (45.18%) Healed, 8 (66.67%) Not Healed | 0.34 (0.07–1.23) | 0.1240 | 1.28 (0.00445–1.54) | 0.1448 |

| Pharmacy | 9 (5.42%) Healed, 1 (8.33%) Not Healed | 0.33 (0.04–7.04) | 0.3573 | 6.85 (0.0227–24.0) | 0.8179 |

| Application at Birth | |||||

| Yes (Ref) | 106 (63.86%) Healed, 5 (41.67%) Not Healed | Ref | – | – | – |

| No | 60 (36.14%) Healed, 7 (58.33%) Not Healed | 2.47 (0.76–8.68) | 0.1360 | – | – |

| Person Applying CHX | |||||

| Healthcare Worker (Ref) | 51 (30.72%) Healed, 1 (8.33%) Not Healed | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Self | 115 (69.28%) Healed, 11 (91.67%) Not Healed | 0.20 (0.01–1.10) | 0.1341 | 4.24 (0.0152–6.19) | 0.5480 |

| CHX Use Demonstration | |||||

| Yes (Ref) | 162 (97.59%) Healed, 11 (91.67%) Not Healed | Ref | – | – | – |

| No | 4 (2.41%) Healed, 1 (8.33%) Not Healed | 0.27 (0.04–5.55) | 0.2614 | – | – |

| CHX Use Demonstration Location | |||||

| Maternity (Ref) | 154 (93.90%) Healed, 10 (83.33%) Not Healed | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Pharmacy | 10 (6.10%) Healed, 2 (16.67%) Not Healed | 0.32 (0.07–2.29) | 0.1808 | 3.89 (0.0108–10.6) | 0.5764 |

| CHX Use Frequency | |||||

| Once Daily (OD) (Ref) | 47 (28.31%) Healed, 4 (33.37%) Not Healed | Ref | – | – | – |

| Twice Daily (BD) | 78 (46.99%) Healed, 6 (50.00%) Not Healed | 1.11 (0.27–4.07) | 0.8803 | – | – |

| Three Times Daily (TID) | 41 (24.70%) Healed, 2 (16.67%) Not Healed | 1.74 (0.32–13.05) | 0.5326 | – | – |

| CHX Use Duration | |||||

| One Week (Ref) | 144 (86.75%) Healed, 8 (66.67%) Not Healed | Ref | – | – | – |

| Beyond One Week | 22 (13.35%) Healed, 4 (33.33%) Not Healed | 0.31 (0.09–1.22) | 0.0697 | – | – |

| Median (IQR) = 7 (3 – 7) | 0.85 (0.74–0.98) | 0.0260 | – | – | |

| CHX Use Experience | |||||

| Easy to Use (Ref) | 156 (93.98%) Healed, 1 (8.33%) Not Healed | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Not Easy to Use | 10 (6.02%) Healed, 11 (91.67%) Not Healed | 0.00583 (0.000303–0.0342) | 2.56e-6 | 0.00247 (0.0000682–0.022) | 0.0000155 |

| CHX Prior Use | |||||

| Yes (Ref) | 37 (22.29%) Healed, 3 (25.00%) Not Healed | Ref | – | – | – |

| No | 129 (77.71%) Healed, 9 (75.00%) Not Healed | 1.16 (0.25–4.13) | 0.8281 | – | – |

Table 3: Association Between Chlorhexidine (CHX) Use and Cord-Care Outcomes

Figures

Keywords

- Surgical spirit

- Dry cord-care

- Chlorhexidine

- Kiambu county

- Cord care

James Maina Githinji1,2, Angeline Chepchirchir3, Prabhjot Kaur Juttla4,&, Ruth Nduati2

1Pharmacist, Department of Health, County Government of Kiambu, Kenya, 2Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 3Department of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 4School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya

&Corresponding author: Prabhjot Kaur Juttla, School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, Email: pkjuttla13@students.uonbi.ac.ke

Received: 22 Mar 2025, Accepted: 07 Aug 2025, Published: 08 Aug 2025

Domain: Maternal and Child Health

Keywords: Surgical spirit, Dry cord-care, Chlorhexidine, Kiambu county, Cord care

©James Maina Githinji et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: James Maina Githinji et al., Evaluating the effectiveness of chlorhexidine digluconate 7.1% in comparison to alternative cord care practices in Kiambu County, Kenya: A cross-sectional study on neonatal outcomes. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8(3):62. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00079

Abstract

Introduction: The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends chlorhexidine (CHX) for cord care in regions with low hospital delivery rates and high neonatal mortality. Based on this, the Kenyan Ministry of Health (MOH) adopted these guidelines nationwide to improve child survival. However, Kiambu County may not meet the WHO’s criteria for CHX use, and we sought to describe and evaluate the outcomes of cord care practices in Kiambu County.

Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional survey and collected data through standardized interviews with mothers of infants attending the 6-week well-child clinic at six high-volume hospitals between August and September 2022. Data analysis was conducted using R version 4.2.1, employing both descriptive and inferential statistics, including bivariable and multivariable logistic regression.

Results: We enrolled 434 mothers to participate in the study. CHX cord care uptake was 27.9% in public facilities and 100% in private ones. CHX resulted in a 93.3% healing rate, surgical spirit achieved 96.2%, and dry cord care showed a 100% healing rate. Self-application of CHX was associated with over four times greater likelihood of healing than healthcare-assisted application (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 4.24, 95%CI= 0.0152 – 6.19, p = 0.55). Previous CHX use increased healing odds (COR = 1.16, 95%CI= 0.25-4.13, p = 0.8281), though not statistically significant. Mothers at Kiambu Level 5 hospital, using predominantly CHX, had a 64% lower likelihood of positive outcomes compared to those at Thika Level 5, where dry cord care was common (AOR = 0.36, 95%CI= 0.12-1.01, p = 0.06). Surgical spirit users had 1.85 times higher odds of positive outcomes compared to CHX users, but this was not statistically significant (AOR=1.85, 95%CI= 0.73-5.07, p = 0.20).

Conclusion: The study found that cord care practices in Kiambu, such as CHX, dry cord care, and methylated spirit, showed comparable effectiveness. This suggests that the Ministry of Health’s nationwide guidelines for CHX use may need to be reconsidered, especially in regions like Kiambu, where alternative practices may be just as effective. A more context-specific approach, considering local health data and infrastructure, could enhance neonatal outcomes and optimize resource use.

Introduction

The first month of a newborn’s life is particularly critical due to the high risk of mortality per day compared to any other period in childhood [1]. Although it represents only about 5% of the under-five time span, it accounts for approximately 47% of all under-five deaths globally [2]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 2.3 million children died in the first 20 days of life in 2022 worldwide [3]. In addition, each day, 6,500 newborns die from various health complications, accounting for 47% of all deaths among children under five years old [3]. Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has the highest neonatal mortality rate (NMR) in the world, with 27 deaths per 1,000 live births, accounting for 43% of all newborn deaths globally [3].

Infections are responsible for over 15% of neonatal deaths, with omphalitis alone contributing to 7-15% of this mortality [4]. This primarily results from unsanitary obstetric conditions during childbirth and harmful cord care practices in developing countries [4]. As a result, the WHO provides different recommendations to countries depending on the quality of obstetric care and the common cord care practices in place [5]. WHO recommends clean and dry cord care for newborns in countries with adequate obstetric care and lower neonatal mortality rates. The current WHO recommendation of chlorhexidine (CHX) cord care targets low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) with high out-of-hospital birth rates and prevalent harmful cord care practices [6]. However, data tracking the effects of this intervention at global, national, and local levels remains limited.

Through various public health campaigns and initiatives such as Linda Mama [7], combined with the improvement in coverage of maternity services, Kenya has managed to reduce the number of home births. According to the Kenya Demographic Health Survey (KDHS) of 2016, 62% of all births in the survey period were assisted by a skilled birth provider. In 2022, the KDHS revealed 89% of all births were attended to by a skilled birth provider and 82.3% in a health facility [8]. While these figures represent national statistics, significant variations exist between the different counties of Kenya. Notably, Kiambu County reports a skilled birth attendance rate of 98% and a hospital delivery rate of 89.2%, much higher than the national average. In addition to this, the national NMR in 2022 stood at 21 per 1000 live births, while Kiambu County’s NMR was 10.65 per 1000 live births [8]. Therefore, Kiambu county may not fully meet the CHX cord care recommendations outlined by the WHO, but regardless, this recommendation has been fully adopted and is the recommended practice nation-wide by Kenya’s Ministry of Health (MOH).

Methods

Study site

This study was conducted in Kiambu County, which is part of the Nairobi Metropolis. Kiambu County covers an area of 2449.2 km2 and has a population of just over 2.4 million, 60% of whom are urban dwellers [9]

Kiambu County has 505 health facilities, among them 108 public, 64 faith-based, and 333 privately owned [10].

Study setting

Kenya’s healthcare system is organized through a devolved structure established by the 2010 Constitution [11,12]. This decentralization aims to bring services closer to the people, allowing for tailored healthcare delivery that responds to the specific needs of each region [11]. Kenya’s healthcare system is divided into national and county levels. The national government sets health policy, standards, and guidelines, while the 47 county governments are responsible for implementing these policies and managing health services within their jurisdictions [13]. Each county has its own healthcare system and varies widely in terms of infrastructure, staffing, resources, and service delivery capabilities.

Kenya’s healthcare facilities are also categorized into different levels based on their infrastructure, staffing, and the range of services provided [14]. Kenya’s healthcare system is structured into five levels, each serving distinct roles and functions. At Level 4, County Referral Hospitals provide specialized outpatient and inpatient services, advanced surgical care, and intensive care, catering to more complex healthcare needs, including surgical deliveries. While Level 5 facilities, offer highly specialized services, advanced diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, and comprehensive care for complex health conditions, serving as referral centers for complicated cases from lower-level facilities.

Study population

All the mothers attending their 6-week well-child clinic visit within Kiambu County between 1st August and 30th September 2022 formed the sampling frame.

Sampling and Sample Size

The study focused on the six healthcare facilities in Kiambu County that recorded the highest number of deliveries. This included two Level 5 hospitals along with one facility from each of the other categories. Specifically, the selected facilities were Thika and Kiambu Level 5 hospitals, Kihara Level 4, Githunguri Level 3 public facility, Nazareth Mission Hospital (a faith-based organization, FBO), and Plainsview private maternity hospital located in Ruiru (Table 1 of the Supplementary Information).

The study employed a multi-stage sampling strategy, utilizing purposive sampling to select hospitals and convenience sampling to recruit participants, similar to our previous study that only examined the uptake of CHX in public facilities [15]. This approach ensured proportional representation based on hospital delivery volumes.

Cochrane’s formula was used, as below, to determine the sample size:

\( n = \frac{Z^2 \cdot p \cdot q}{e^2} \)

\( n = \frac{(1.96)^2 \cdot (0.53 \times 0.47)}{(0.05)^2} \)

With a 95% confidence level (Z-score = 1.96), p was set at 0.53, based on an Ethiopian study [16], q was taken as 1−p, and the margin of error (e) was 0.05. The calculated sample size was n = 383, which was adjusted by 10% to account for potential attrition, leading to a final sample size of n = 421.

Study design

This was a cross-sectional survey using a standardized interview tool. Data were collected from mothers attending the 6-week well-baby clinic at six selected high-volume public and private hospitals, as previously described [15]. Mothers of infants attending this clinic were invited to participate in the study. After obtaining informed consent, mothers were recruited in succession until the desired sample size was reached for each facility. Interviews were conducted with 434 mothers from various facilities to assess their use of CHX for cord care or alternative practices.

Inclusion criteria: Mothers eligible for the study included those bringing infants to the 6-week well-child clinic at the selected facilities, whose babies were born in Kiambu County, and who were willing to provide written informed consent and answer questions using the standardized interview tool. Data was collected through structured questionnaires administered by researchers.

Exclusion Criteria: The study excluded mothers whose infants were older than seven weeks, those who had delivered in facilities outside Kiambu County, and individuals deemed not mentally sound or unable to comprehend the informed consent process. Additionally, mothers who did not agree to sign the written informed consent form were also excluded from participation.

Data collection

Data were collected during the months of August and September 2022, using a structured questionnaire that included relevant biodata, gender of the neonate, ANC attendance, and facility of delivery. Information on whether a mother was issued with CHX or a prescription to purchase it, the ease of use of CHX, and outcomes of use were captured, too.

Questions were structured with various options to choose from. Research assistants used KoboToolbox version 2.022.16 (Harvard Humanitarian Initiative. Available from https://www.kobotoolbox.org) to collect and manage data. The surveys were available in both English or Kiswahili language depending on the respondent’s preference.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using R version 4.2.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), employing both descriptive and inferential statistical methods. Descriptive statistics were utilized to summarize sociodemographic characteristics and to assess the uptake of CHX cord care, as well as the types of cord care selected by participants. The crude odds ratio (COR) was calculated for each independent variable in relation to the dependent variable. Bivariable and subsequently multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate the crude and adjusted associations of each variable with the uptake of CHX.

In our previous work, the data from private health facilities was excluded from the analysis as it was inconsequential [15]. However, in this study, we have included all the recruited mothers and are focusing on the outcomes of the cord care practices used in both public and private health facilities in the county.

The criteria for variable selection in the multivariate model included the following: first, individual hospitals were excluded from the model to account for the observed clustering effect within institutions; given that this clustering effect was not incorporated into the analysis, the individual hospital variable was omitted, and instead, the classification into hospital levels was utilized. Second, variables with exceptionally wide confidence intervals were removed from consideration. Finally, variables with p-values greater than 0.2 were excluded from the final model [17].

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval was obtained at various administrative levels, including county and sub-county authorities, before the study commenced. Ethical clearance was secured from the University of Nairobi/Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH) Ethical Review Committee (ERC) [P470/05/2022], County Government of Kiambu Department of Health Services, Kiambu County [KIAMBU/HRDU/22/09/14/RA_GITHINJI], and a research license obtained from the National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation [NACOSTI/P/22/20446]. The participating facilities also provided permission to conduct the study in their facilities: SCMOH/GSC/RES.VOL1.1/1/2022; KBU/STAFF.14/XL IV/ANNEX 34; CGK/DHS/KL4H/2022 and MOH/TKA/GEN/VOL.V/800. Respondents provided written informed consent prior to being interviewed.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

A total of 434 mothers participated in the study. Table 1 summarizes the social demographic characteristics of the sample. The majority were aged between 25 and 34 years (51.6%, n=224), with only 9.9% (n=43) aged between 35 and 44 years. Most mothers (47.2%, n=205) had completed secondary school, while smaller proportions had attained primary school (16.1%), college (27.0%), or university education (9.7%). The majority of participants were married (77.0%, n=334). Employment data indicated that 47.9% (n=208) of mothers were not employed, with smaller proportions being employed or self-employed.

Regarding antenatal care, 95.6% (n=415) attended ANC, with a median of four visits. Most mothers (70.1%) attended Level 5 hospitals, and the majority delivered in hospitals (84.6%). For CHX cord care, 21.7% (n=94) received CHX, while 12.4% (n=54) reported prior use of CHX.

CHX uptake per facility

The uptake of CHX gel/solution for cord care varied across health facilities in the study population of 434 mothers. Thika Level 5 Hospital had a low CHX usage rate, with only 4 out of 151 mothers (2.7%) applying it. In contrast, Kiambu Level 5 Hospital showed a much higher uptake, with 107 of 153 mothers (69.9%) using CHX. At Kihara Level 4 Hospital, the uptake was moderate, with 7 out of 49 mothers (14.3%) using CHX. Similarly, Githunguri Level 3 Hospital had 7 of 28 mothers (25.0%) using CHX. In the private facilities, both Nazareth and Plainsview Hospitals had full compliance, with all 20 mothers (100%) at Nazareth and all 33 mothers (100%) at Plainsview using CHX. Overall, CHX cord-care uptake was found to be 27.9% in public health facilities but 100.0% in private health facilities.

Outcomes of chlorhexidine as reported by mothers

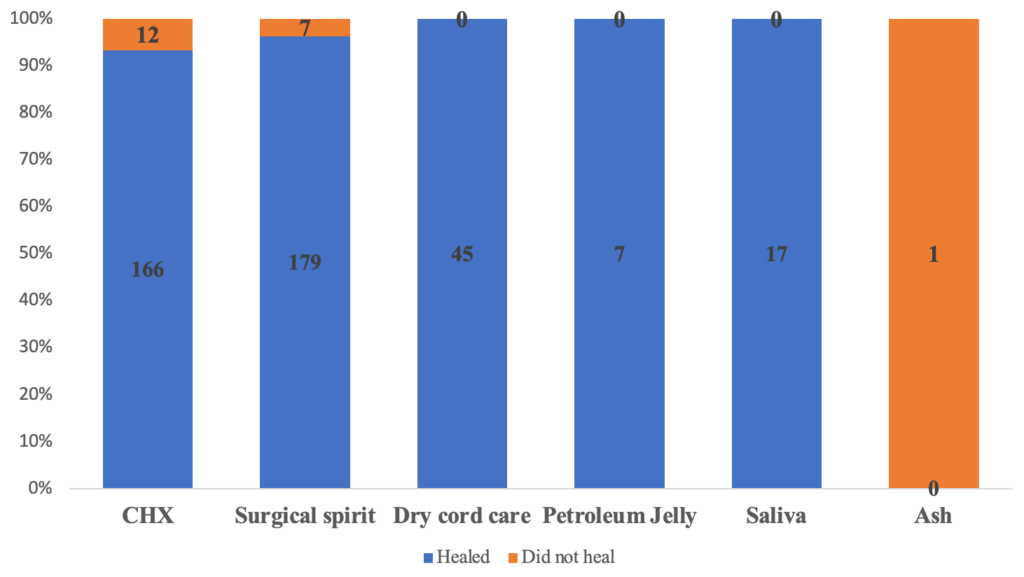

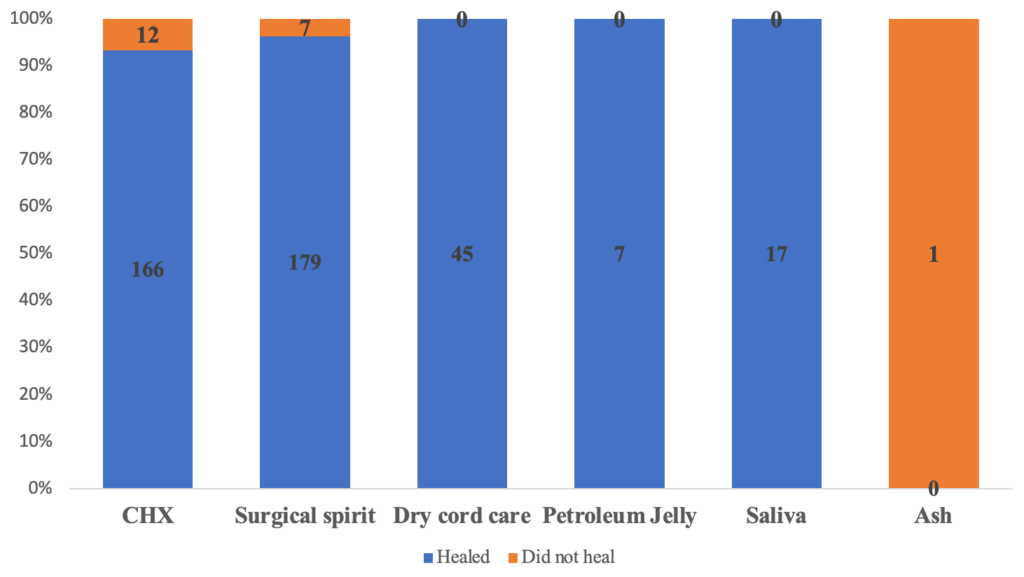

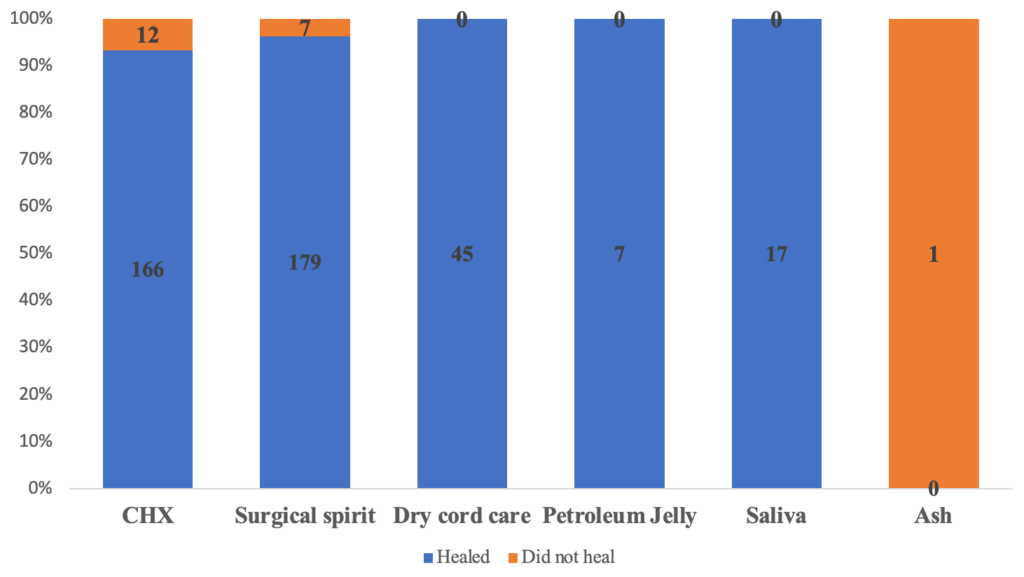

Figure 1 shows the healing outcomes for various cord care methods used by mothers. CHX was used by 178, resulting in 93.3% (n=166) of cases healing and 6.7% (n=12) not healing. Surgical spirit was used by the largest portion of respondents at 186 and had the higher success rate than CHX, with 96.2% (n=179) of cases healing and only 3.8% (n=7) not healing. Dry cord care demonstrated high effectiveness, with a 100% success rate (n=45), as did petroleum jelly and saliva, both achieving 100% healing rates (n=7 and n=17, respectively). In contrast, ash, used in a single case, resulted in non-healing, making it the only method with a 0% healing rate. Overall, dry cord care, petroleum jelly, and saliva were the most effective methods, with all cases resulting in complete healing. These were followed by surgical spirit with a 96% healing rate and chlorhexidine (CHX) with 93%.

Factors associated with cord care outcomes

Table 2 displays the association between several maternal factors; such as CHX provision, its uptake, prior experience with CHX, and the use of alternative cord care methods, and cord care outcomes. The data suggest no statistically significant relationship between these variables and positive cord care outcomes. Specifically, among those provided with CHX, the crude odds ratio (cOR) for a healed outcome was 0.90 (95% CI: 0.25-2.53, p=0.8537) compared to those not provided with CHX. Similarly, CHX uptake showed a cOR of 2.24 (95% CI: 0.91-5.83, p=0.0842), and prior use of CHX had a cOR of 1.82 (95% CI: 0.51-5.20, p=0.3010), both indicating no significant impact on healing outcomes. Alternative cord care methods also showed no significant difference compared to CHX.

Factors associated with CHX use and cord care outcomes

Table 3 depicts the relationship between specific aspects of CHX use, such as duration and ease of use, and cord care outcomes, identifying two significant associations. Each additional day of CHX application reduces the likelihood of a positive outcome by 15% (COR = 0.85, 95% CI: 0.74–0.98, p=0.0260). Additionally, patients who found CHX use difficult were nearly 100% less likely to experience favourable cord care results compared to those who found it easy, with a COR of 0.00583 (95% CI: 0.000303–0.0342, p=0.00000256).

Table 3 also presents an analysis of the association between various CHX application variables and cord-care outcomes, adjusting for confounding factors. Among mothers who received CHX, those who obtained it from outside the hospital had a slightly higher, though not statistically significant, likelihood of a healed outcome compared to those who received it in the maternity setting (Adjusted OR = 1.28, 95% CI=0.00445-1.54, p = 0.1448). Additionally, mothers who obtained CHX from a pharmacy demonstrated an elevated adjusted odds ratio of 6.85 for a healed cord outcome, though this also did not reach statistical significance (AOR= 6.85, 95% CI= 0.0227 – 24.0, p = 0.8179). Regarding the application of CHX, mothers who self-applied it were over four times more likely to experience healing compared to those who had a healthcare worker apply it though not statistically significant (AOR = 4.24, 95% CI= 0.0152- 6.19, p = 0.5480). Mothers who received CHX demonstrations in a pharmacy also showed a non-significant increased likelihood of cord healing (AOR = 3.89, 95% CI= 0.0108 – 10.6 p = 0.5764) compared to those demonstrated in the maternity ward.

The user experience variable proved to be significant: mothers who found CHX challenging to use had a drastically lower likelihood of a healed cord outcome (AOR = 0.00247, 95%CI= 0.000068 -0.0222, p = 0.0000155) than those who found it easy to use. Lastly, prior CHX use was associated with a moderately higher adjusted odds of a healed outcome (AOR = 3.89, p = 0.4943) for those who had used CHX before compared to those without prior use, though this association was not statistically significant.

Comparison of CHX use in two level 5 Health facilities

The study examined cord care outcomes across two Level 5 hospitals and compared the effectiveness of Chlorhexidine (CHX) and Surgical Spirit. Thika Level 5 Hospital accounted for 51.05% of infants that had healed umbilical cords, and 27.78% of infants that had not healed. In contrast, Kiambu Level 5 Hospital accounted for 48.95% of infants that experienced healing, and 72.22% that did not heal. Infants receiving care at Kiambu L5 Hospital had a 64% lower likelihood of healing compared to those at Thika L5 Hospital (AOR = 0.36, 95% CI: 0.12–1.01, p = 0.06), suggesting a potential difference in cord care effectiveness between the two facilities, though the result was not statistically significant (Table 2, Supplementary Information).

Comparison of Outcomes Between CHX Use and Surgical Spirit

When comparing cord care practices, 48.12% of infants who received CHX had healed, while 63.16% had not. In contrast, among those treated with Surgical Spirit, 51.88% had healed, and 36.84% had not. Surgical Spirit use was associated with 1.85 times higher odds of healing compared to CHX (Crude Odds Ratio = 1.85, 95% CI: 0.73–5.07, p = 0.20), but this difference was not statistically significant. The findings indicate a non-significant trend favouring Surgical Spirit and Thika Level 5 Hospital in relation to improved cord healing outcomes; however, the observed differences did not reach statistical significance (Table 3; Supplementary Information).

Discussion

The WHO recommends CHX cord care primarily for LMICs with high out-of-hospital birth rates and harmful cord care practices, which contribute to NMR exceeding 30 per 1,000 live births [5]. In Kenya, home births and unattended deliveries have declined, with the KDHS reporting skilled birth attendance increasing from 62% in 2016 to 89% in 2022 [8,18]. While Kiambu County may not align perfectly with WHO’s CHX recommendations, the Ministry of Health in Kenya has adopted CHX cord care as the standard practice nationwide.

We found that, whereas CHX cord care was fully implemented in private health facilities, public health facilities had a low uptake (22.9%), favouring alternative cord care practices instead. However, despite this, dry cord care was associated with the highest healing outcome, followed by surgical spirit and then CHX. Therefore, while these facilities contradict the national guidelines, their methods have shown higher effectiveness compared to CHX and warrant further investigation. A total of 256 mothers who did not employ CHX observed successful cord healing without sepsis when implementing alternative methods such as dry cord care, petroleum jelly, or even saliva. Out of the total sample size of 178 newborns whose mothers utilized CHX, twelve cases of sepsis were seen. Conversely, among the 186 infants whose mothers employed surgical spirit, seven instances of sepsis were recorded. This is similar to the findings of Sazawal et al. who did not find a significant difference in mortality between CHX and dry cord care in their Pemba study [19]. Our findings are also similar to the findings of Semrau et al. who reported no benefit of using CHX in East African settings, especially in regions where most births are conducted in health facilities, as in Kiambu County [20].

In our study, some mothers reported using surgical spirit for cord care, while 45 participants (17.6%) reported using the dry cord care method. These findings align with a previous study conducted in a level 3 nursery and NICU in Lahore by Andleeb et al in 2020 [21], but differ from a study conducted in Pumwani maternity hospital in Nairobi by Kinanu et al in 2016 (Kinanu et al. , 2016) where the dry method of cord care was the most commonly used, followed by the use of surgical spirit [22]. In the present study, it was observed that the healthcare facilities where the mothers gave birth did not have any supplies of chlorhexidine (CHX) and did not provide guidance to the mothers on its procurement. Consequently, the mothers had to depend on affordable and widely available alternatives within their specific context.

Overall, this study found that CHX use did not significantly impact all the umbilical cord healing outcomes when lumped together. This included providing CHX and prior experience with CHX. Comparisons between CHX and alternative cord-care methods used in this study revealed comparable healing outcomes, suggesting that both approaches were similarly effective. This contradicts the findings of a meta-analysis by Imdad et al. which found that applying CHX to the umbilical stump can significantly reduce incidence of umbilical cord infection [23]. However, an important caveat is that this conclusion applied to community settings as opposed to ours, which is facility-based. Our results also differ from a study in South Sudan, which indicated that the application of CHX gel helped reduce cord sepsis in conflict-affected areas, where most births occur at home under unsanitary conditions [24].

Mothers who found CHX easy to use were significantly more likely to have a positive healing outcome compared to those who did not find it easy to use, indicating a strong relationship between user experience and healing success. Additional studies have indicated that mothers resorted to alternative products to clean dry flakes left by the dried CHX gel on the umbilical stump, potentially increasing infection risk [25]. Umbilical cords that remain dry are associated with a shorter time to detachment [26]. In a similar study conducted in Nigeria, delayed cord separation was perceived as an adverse outcome by mothers, prompting them to use alternative products to prevent infections. These mothers viewed prolonged cord attachment as a side effect of CHX gel and indicated reluctance to use it again [27].

The duration and experience of CHX use were found to have a statistically significant association with cord-care outcomes; each additional day of CHX application beyond one week was associated with an 18% decrease in the likelihood of a favorable outcome. A probable reason for this could be prolonged moisture at the umbilical site, which may create an environment conducive to bacterial growth and delayed healing. These findings contrast with the 7-10 day application recommendation provided by systematic reviews [23,28]. The reduced likelihood of a positive outcome with prolonged CHX use beyond one week may be due to the persistence of moisture at the umbilical site, which can inhibit natural drying and separation. This moist environment could potentially disrupt the natural healing process, increasing the risk of bacterial colonization and infection. Prolonged application may also lead to irritation or residue build-up, prompting mothers to use additional products to clean the area, which could introduce further risk.

A comparison of outcomes from two major facilities in this county revealed notable differences in CHX usage and cord-care results. Mothers attending Kiambu Level 5 Hospital reported a 69.9% rate of CHX use, yet demonstrated a 64% lower rate of positive cord-care outcomes compared to Thika Level 5 Hospital, where CHX use was only 2.7%. Of these facilities, KL5H adheres closely to WHO and Ministry of Health guidelines, while TL5H has adapted its practices based on the recognition that Kiambu County’s conditions differ significantly from those of the countries informing these guidelines. Between the two institutions, TL5H employing dry cord care reported more favourable outcomes, though the data is not statistically significant. The Kenya Ministry of Health’s neonatal cord care guidelines, recommending CHX application across the country, merit reconsideration in light of the evidence and the context-specific criteria outlined by the WHO. According to WHO recommendations, CHX is most effective in areas with high neonatal mortality rates, poor hygienic birth practices, and limited access to sterile environments. Applying these recommendations indiscriminately in counties that do not meet these criteria may lead to unnecessary expenses and potentially suboptimal outcomes, such as delayed cord healing from prolonged moisture caused by CHX application beyond one week. Implementing region-specific guidelines would not only align with WHO recommendations but also reduce financial burdens on mothers while ensuring that cord care practices are safe, culturally acceptable, and contextually appropriate. Kenya’s policies could benefit from a nuanced approach, integrating local epidemiological data and health infrastructure capacity into decision-making for neonatal cord care. This adaptive strategy may enhance outcomes while optimizing resource allocation.

The odds of achieving a good outcome were 1.85 times higher for mothers who employed surgical spirit compared to those who applied CHX, albeit not statistically significant. Several studies published have shown comparable efficacy between the two products and have reported use of methylated spirit to more that chlorhexidine [29,30]. These researchers also found CHX to have a longer separation time than Methylated spirit. Similar to our study findings, Afolaranmi et al. (2018) among many other studies, found methylated spirit to be the most used cord care product [31]. This could be a result of its low cost and high availability in hospital settings. It is an antiseptic with multiple other uses in infection control. Dry cord care is also finding high use because it is free of cost, is a WHO recommendation for settings with a low neonatal mortality rate, and is delivered under the care of trained medical workers since the outcomes of care are comparable and not inferior to those of CHX [19].

Given the findings of this study and the low neonatal mortality rates in Kiambu County, further investigations are recommended to assess the efficacy of dry cord care practices. This investigation should focus on understanding the comparative effectiveness of dry cord care against chlorhexidine application in reducing the incidence of neonatal infections. Since the context of Kiambu County features predominantly facility-based deliveries and lower rates of neonatal mortality, it is essential to explore whether simpler, cost-effective interventions such as dry cord care can achieve similar or better outcomes for newborn health. Additionally, exploring the factors influencing mothers’ preferences and adherence to different cord care practices may provide valuable insights to enhance maternal and child health strategies in the region.

Conclusion

The findings of this study indicate that various health facilities in Kiambu county have varying adherence to the national recommended cord care practices, a finding that echoes our previous work [32]. Our findings also demonstrate that the CHX cord care outcomes of cord care in health facilities in Kiambu are not significantly different from those achieved with alternative methods such as dry cord care or the application of methylated spirit. These alternatives are more cost-effective and widely accessible in the community. This suggests that while chlorhexidine has been promoted for its potential benefits, its use may not be justified in settings where simpler and less expensive interventions can provide comparable results. Consequently, healthcare policymakers should consider prioritizing education on and the promotion of these cost-effective practices to optimize resource allocation and improve neonatal care in Kiambu County. The emphasis should be on ensuring that all mothers have access to effective cord care methods that can support the health and well-being of their newborns.

What is already known about the topic

- The WHO recommends chlorhexidine (CHX) for umbilical cord care in settings with high neonatal mortality and low hospital delivery rates to reduce infections.

- The Kenyan Ministry of Health (MOH) adopted CHX nationwide, aligning with WHO guidelines to improve neonatal survival.

- However, Kiambu County has a high rate of hospital deliveries, which may not fit the WHO criteria for CHX use, raising the need to evaluate local cord care practices.

What this study adds

- Alternative cord care methods (dry cord care and surgical spirit) had comparable or better healing rates than CHX in Kiambu County, challenging the universal application of CHX guidelines.

- Self-application of CHX showed better healing outcomes than healthcare-assisted application, suggesting the importance of caregiver involvement in cord care.

- Findings suggest that a one-size-fits-all national CHX policy may not be optimal, highlighting the need for a context-specific approach that considers local health infrastructure and neonatal outcomes.

Authors´ contributions

JMG conceptualized and designed the study, secured resources, organized and conducted data collection, performed data analysis, and drafted the initial manuscript. AC and RN provided expert supervision, ensuring adherence to ethical standards and study protocols, while offering critical guidance on methodology and reviewing the manuscript. RN also provided the necessary funding. PKJ interpreted the results, contributed to drafting, and undertook substantial revisions to finalize the manuscript. All authors were involved in data analysis and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript, and approved the final version for publication, collectively ensuring the integrity and accuracy of the work.

List of abbreviations

CHX Chlorhexidine 7.1% digluconate

MOH Ministry of Health

WHO World Health Organization

NMR Neonatal Mortality Rate

SSA Sub-Saharan Africa

LMICs Low-and Middle-Income Countries

KDHS Kenya Demographic Health Survey

FBO Faith Based Organizations

COR Crude Odds Ratio

AOR Adjusted Odds Ratio

| Variable | Total N = 434, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 15–24 | 167 (38.5%) |

| 25–34 | 224 (51.6%) |

| 35–44 | 43 (9.9%) |

| Level of Education Attained | |

| Primary school | 70 (16.1%) |

| Secondary school | 205 (47.2%) |

| College | 117 (27.0%) |

| University | 42 (9.7%) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 87 (20.1%) |

| Married | 334 (77.0%) |

| Divorced or separated | 10 (2.3%) |

| Widowed | 3 (0.7%) |

| Occupation | |

| Unemployed | 208 (47.9%) |

| Employed | 76 (17.5%) |

| Self-employed | 150 (34.6%) |

| ANC attendance | |

| Attended ANC | 415 (95.6%) |

| Did not attend ANC | 19 (4.4%) |

| Attending Hospital Level | |

| Level 3 | 28 (18.7%) |

| Level 4 | 102 (11.3%) |

| Level 5 | 304 (70.1%) |

| Delivery Place | |

| Health centre/dispensary | 67 (15.4%) |

| Hospital | 367 (84.6%) |

| Issued with CHX | |

| Yes | 94 (21.7%) |

| No | 340 (78.3%) |

| Given CHX Prescription (n=340) | |

| Yes | 132 (38.8%) |

| No | 208 (61.2%) |

| CHX bought after prescription (n=132) | |

| Yes | 86 (63.6%) |

| No | 46 (34.8%) |

| Prior use of CHX | |

| Yes | 54 (12.4%) |

| No | 380 (87.6%) |

| Variables | Cord-care outcome Healed | Cord-care outcome Not Healed | Crude OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provided CHX | ||||

| Yes | 90 (21.74%) | 4 (20.00%) | Ref | |

| No | 324 (78.26%) | 16 (80.00%) | 0.90 (0.25–2.53) | 0.8537 |

| Uptake CHX | ||||

| Yes | 166 (40.10%) | 12 (60.00%) | Ref | |

| No | 248 (59.90%) | 8 (40.00%) | 2.24 (0.91–5.83) | 0.0842 |

| Prior use CHX | ||||

| Yes | 50 (12.08%) | 4 (20.00%) | Ref | |

| No | 364 (87.92%) | 16 (80.00%) | 1.82 (0.51–5.20) | 0.301 |

| Cord-care used | ||||

| CHX | 166 (40.10%) | 12 (60.00%) | Ref | |

| Alternate | 248 (59.90%) | 8 (40.00%) | 2.24 (0.90–5.83) | 0.0842 |

| Variable | Cord-Care Outcome | Crude OR (95% CI) | P-Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place Provided CHX | |||||

| Maternity (Ref) | 82 (49.40%) Healed, 3 (25.00%) Not Healed | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Bought Outside Facility | 75 (45.18%) Healed, 8 (66.67%) Not Healed | 0.34 (0.07–1.23) | 0.1240 | 1.28 (0.00445–1.54) | 0.1448 |

| Pharmacy | 9 (5.42%) Healed, 1 (8.33%) Not Healed | 0.33 (0.04–7.04) | 0.3573 | 6.85 (0.0227–24.0) | 0.8179 |

| Application at Birth | |||||

| Yes (Ref) | 106 (63.86%) Healed, 5 (41.67%) Not Healed | Ref | – | – | – |

| No | 60 (36.14%) Healed, 7 (58.33%) Not Healed | 2.47 (0.76–8.68) | 0.1360 | – | – |

| Person Applying CHX | |||||

| Healthcare Worker (Ref) | 51 (30.72%) Healed, 1 (8.33%) Not Healed | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Self | 115 (69.28%) Healed, 11 (91.67%) Not Healed | 0.20 (0.01–1.10) | 0.1341 | 4.24 (0.0152–6.19) | 0.5480 |

| CHX Use Demonstration | |||||

| Yes (Ref) | 162 (97.59%) Healed, 11 (91.67%) Not Healed | Ref | – | – | – |

| No | 4 (2.41%) Healed, 1 (8.33%) Not Healed | 0.27 (0.04–5.55) | 0.2614 | – | – |

| CHX Use Demonstration Location | |||||

| Maternity (Ref) | 154 (93.90%) Healed, 10 (83.33%) Not Healed | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Pharmacy | 10 (6.10%) Healed, 2 (16.67%) Not Healed | 0.32 (0.07–2.29) | 0.1808 | 3.89 (0.0108–10.6) | 0.5764 |

| CHX Use Frequency | |||||

| Once Daily (OD) (Ref) | 47 (28.31%) Healed, 4 (33.37%) Not Healed | Ref | – | – | – |

| Twice Daily (BD) | 78 (46.99%) Healed, 6 (50.00%) Not Healed | 1.11 (0.27–4.07) | 0.8803 | – | – |

| Three Times Daily (TID) | 41 (24.70%) Healed, 2 (16.67%) Not Healed | 1.74 (0.32–13.05) | 0.5326 | – | – |

| CHX Use Duration | |||||

| One Week (Ref) | 144 (86.75%) Healed, 8 (66.67%) Not Healed | Ref | – | – | – |

| Beyond One Week | 22 (13.35%) Healed, 4 (33.33%) Not Healed | 0.31 (0.09–1.22) | 0.0697 | – | – |

| Median (IQR) = 7 (3 – 7) | 0.85 (0.74–0.98) | 0.0260 | – | – | |

| CHX Use Experience | |||||

| Easy to Use (Ref) | 156 (93.98%) Healed, 1 (8.33%) Not Healed | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Not Easy to Use | 10 (6.02%) Healed, 11 (91.67%) Not Healed | 0.00583 (0.000303–0.0342) | 2.56e-6 | 0.00247 (0.0000682–0.022) | 0.0000155 |

| CHX Prior Use | |||||

| Yes (Ref) | 37 (22.29%) Healed, 3 (25.00%) Not Healed | Ref | – | – | – |

| No | 129 (77.71%) Healed, 9 (75.00%) Not Healed | 1.16 (0.25–4.13) | 0.8281 | – | – |

References

- Fleischmann C, Reichert F, Cassini A, Horner R, Harder T, Markwart R, Tröndle M, Savova Y, Kissoon N, Schlattmann P, Reinhart K, Allegranzi B, Eckmanns T. Global incidence and mortality of neonatal sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child [Internet]. 2021 Jan 22 [cited 2025 Aug 8];106(8):745. Available from: https://adc.bmj.com/content/106/8/745 doi:10.1136/archdischild-2020-320217

- World Health Organization. Newborn mortality [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2024 Mar 14 [cited 2025 Aug 8]. [about 3 screens]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/newborn-mortality

- Painter K, Anand S, Philip K. Omphalitis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan- [cited 2025 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513338/

- World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on maternal and newborn care for a positive postnatal experience [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2022 Mar 30 [cited 2025 Aug 8]. 242 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240045989

- World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2016 Nov 28 [cited 2025 Aug 8]. 196 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549912

- Ombere SO. Can “the expanded free maternity services” enable Kenya to achieve universal health coverage by 2030: qualitative study on experiences of mothers and healthcare providers. Front Health Serv [Internet]. 2024 Sep 10 [cited 2025 Aug 8];4:1325247. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frhs.2024.1325247/full doi:10.3389/frhs.2024.1325247

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2022: Key Indicators Report [Internet]. Nairobi (Kenya): Kenya National Bureau of Statistics; 2023 Jan [cited 2025 Aug 8]. 95 p. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/PR143/PR143.pdf

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. 2019 Kenya Population and Housing Census [Internet]. Nairobi (Kenya): Kenya National Bureau of Statistics; 2019 Nov 4 [cited 2025 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.knbs.or.ke/2019-kenya-population-and-housing-census-results/

- County Government of Kiambu. County Annual Development Plan 2021-2022 [Internet]. Kiambu (Kenya): County Government of Kiambu; 2020 Aug [cited 2025 Aug 8]. 451 p. Available from: https://repository.kippra.or.ke/handle/123456789/3206

- The World Bank Group. Kenya’s Devolution [Internet]. Washington (DC): The World Bank Group; 2019 Nov 26 [cited 2025 Aug 8]. [about 2 screens]. Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/kenya/brief/kenyas-devolution

- Wanyande P, Mboya T. DEVOLUTION: The Kenya Case [Internet]. Nairobi (Kenya); 2016 [cited 2025 Aug 8]. 13 p. Available from: https://www.hss.de/download/publications/Federalism_2016_10.pdf

- Juttla PK, Wamaitha N, Milliano F, Nyawira J, Mungai S, Mwancha-Kwasa M. Perceptions of Kenyan healthcare workers: Assessing national and county governments’ pandemic response. Social Sciences & Humanities Open [Internet]. 2023 Nov 1 [cited 2025 Aug 8];8(1):100726. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2590291123003315 doi:10.1016/j.ssaho.2023.100726

- World Health Organization. Primary health care systems (PRIMASYS): case study from Kenya, abridged version [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2017 [cited 2025 Aug 8]. 10 p. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/341073

- Githinji JM, Chepchirchir A, Juttla PK, Nduati R. Adoption and factors associated with 7.1% chlorhexidine digluconate cord care standards in public health facilities in Kiambu County, Kenya. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health [Internet]. 2024 Sep 4 [cited 2025 Aug 8];29:101781. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2213398424002781 doi:10.1016/j.cegh.2024.101781

- Tadesse Y, Mussema Abdella Y, Tadesse Y, Mathewos B, Kumar S, Teferi E, Bekele A, Gebremariam Gobezayehu A, Wall S. Integrating chlorhexidine for cord care into community based newborn care in Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Aug 8]. 2019 (Supp.3). Available from: https://www.emjema.org/index.php/EMJ/article/download/1395/556/3266

- Hosmer DW Jr, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied logistic regression [Internet]. 3rd ed. Hoboken (NJ): Wiley; 2013 [cited 2025 Aug 8]. Available from: https://books.google.co.ke/books?id=64JYAwAAQBAJ

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2014 [Internet]. Nairobi (Kenya): Kenya National Bureau of Statistics; 2015 Dec [cited 2025 Aug 8]. 569 p. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr308/fr308.pdf

- Sazawal S, Dhingra U, Ali SM, Dutta A, Deb S, Ame SM, Mkasha MH, Yadav A, Black RE. Efficacy of chlorhexidine application to umbilical cord on neonatal mortality in Pemba, Tanzania: a community-based randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health [Internet]. 2016 Nov 1 [cited 2025 Aug 8];4(11):e837-44. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27693438/ doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30223-6

- Semrau KEA, Herlihy J, Grogan C, Musokotwane K, Yeboah-Antwi K, Mbewe R, Banda B, Mpamba C, Hamomba F, Pilingana P, Zulu A, Chanda-Kapata P, Biemba G, Thea DM, MacLeod WB, Simon JL, Hamer DH. Effectiveness of 4% chlorhexidine umbilical cord care on neonatal mortality in Southern Province, Zambia (ZamCAT): a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health [Internet]. 2016 Nov 1 [cited 2025 Aug 8];4(11):e827-36. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2214109X16302157 doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30215-7

- Kanwal A, Anwar Z, Akram M, Anwar S, Pirzada S. Cord care methods in neonates. PJMHS [Internet]. 2021 Oct 30 [cited 2025 Aug 8];15(10):3509-10. Available from: https://pjmhsonline.com/published-issues/2021/october/103509 doi:10.53350/pjmhs2115103509

- Kinanu L, Odhiambo E, Mwaura J, Habtu M. Cord care practices and omphalitis among neonates aged 3 – 28 days at Pumwani maternity hospital, Kenya. Journal of Biosciences and Medicines [Internet]. 2015 Dec 25 [cited 2025 Aug 8];4(1):27-36. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=62583 doi:10.4236/jbm.2016.41004

- Imdad A, Bautista RMM, Senen KAA, Uy MEV, Mantaring JB III, Bhutta ZA. Umbilical cord antiseptics for preventing sepsis and death among newborns. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2013 May 31 [cited 2025 Aug 8];2015(3):CD008635. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD008635.pub2 doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008635.pub2

- Draiko CV, McKague K, Maturu JD, Joyce S. The effect of umbilical cord cleansing with chlorhexidine gel on neonatal mortality among the community births in South Sudan: a quasi-experimental study. Pan Afr Med J [Internet]. 2021 Jan 22 [cited 2025 Aug 8];38:78. Available from: https://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/38/78/full doi:10.11604/pamj.2021.38.78.21713

- Ambale C. Assessment of the use of chlorhexidine digluconate gel for cord care at Kangundo Level 4 Hospital. International Journal of Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2020 Dec [cited 2025 Aug 8];101:316. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S120197122031540X doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.824

- López-Medina MD, Linares-Abad M, López-Araque AB, López-Medina IM. Dry care versus chlorhexidine cord care for prevention of omphalitis. Systematic review with meta-analysis. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem [Internet]. 2019 Jan 31 [cited 2025 Aug 8];27:e3106. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0104-11692019000100601&tlng=en doi:10.1590/1518-8345.2695.3106

- Aitafo JE, West BA, Okari TG. Awareness, attitude and use of chlorhexidine gel for cord care in a well-baby clinic in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Int J Health Sci Res [Internet]. 2021 Aug 26 [cited 2025 Aug 8];11(8):180-9. Available from: https://www.ijhsr.org/IJHSR_Vol.11_Issue.8_Aug2021/IJHSR026.pdf doi:10.52403/ijhsr.20210826

- Sankar MJ, Chandrasekaran A, Ravindranath A, Agarwal R, Paul VK. Umbilical cord cleansing with chlorhexidine in neonates: a systematic review. J Perinatol [Internet]. 2016 Apr 25 [cited 2025 Aug 8];36(S1):S12-20. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/jp201628 doi:10.1038/jp.2016.28

- Shwe D, Afolaranmi T, Egbodo C, Musa J, Oguche S, Bode-Thomas F. Methylated spirit versus chlorhexidine gel: a randomized non-inferiority trial for prevention of neonatal umbilical cord infection in Jos, north-central Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice [Internet]. 2021 May 1 [cited 2025 Aug 8];24(5):762-9. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/10.4103/njcp.njcp_535_20 doi:10.4103/njcp.njcp_535_20

- Ans M, Hussain M, Ahmed F, Khan KJ, Abbas S, Sultan M. Umbilical cord care practices and cord care education of mothers attending health care (Pakistan Prospect). Health [Internet]. 2023 Jan 16 [cited 2025 Aug 8];15(1):20-32. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=122500 doi:10.4236/health.2023.151002

- Afolaranmi TO, Hassan ZI, Akinyemi OO, Sule SS, Malete MU, Choji CP, Bello DA. Cord care practices: a perspective of contemporary African setting. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2018 Jan 31 [cited 2025 Aug 8];6:10. Available from: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00010/full doi:10.3389/fpubh.2018.00010

- Githinji JM, Chepchirchir A, Nyanchoka BO, Juttla PK, Nduati R. “…In Kiambu county, there are different things being done”: A qualitative exploration of healthcare workers’ experiences with cord care practices. PLoS One [Internet]. 2025 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Aug 8];20(6):e0326506. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0326506 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0326506