Research | Open Access | Volume 8 (3): Article 65 | Published: 25 Aug 2025

Determinants of home delivery practices among women in Asutifi North District, Ghana, 2020

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Tables

| Variable | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | ||

| ≤20 Years | 33 | 8.13 |

| 21-34 Years | 261 | 64.28 |

| ≥35 Years | 112 | 27.59 |

| Mean±SD | 29.93±6.32 | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 251 | 61.82 |

| Single | 113 | 27.83 |

| Divorced | 42 | 10.34 |

| Maternal education | ||

| Basic | 162 | 39.90 |

| No Formal Education | 75 | 18.47 |

| Secondary | 96 | 23.65 |

| Tertiary | 73 | 17.98 |

| Religion | ||

| Traditional and Others | 60 | 14.78 |

| Christianity | 230 | 56.65 |

| Islamic | 116 | 28.57 |

| Place of residence | ||

| Urban | 81 | 19.95 |

| Rural | 325 | 80.05 |

| Employment status | ||

| Salaried Employed | 57 | 14.04 |

| Self Employed | 172 | 42.36 |

| Unemployed | 177 | 43.60 |

| Partner education | ||

| Basic | 112 | 27.59 |

| No Formal Education | 89 | 21.92 |

| Secondary | 117 | 28.82 |

| Tertiary | 88 | 21.67 |

| No. of children mother has | ||

| ≤1 Child | 61 | 15.02 |

| 2 Children | 147 | 36.21 |

| ≥3 Children | 198 | 48.77 |

| Mean±SD | 2.70±1.33 | |

Table 1: Socio-demographic Characteristics of Respondents (N=406)

| Variable | Total | Facility n (%) | Home n (%) | Chi square (p value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 251 | 209 (83.27) | 42 (16.73) | 11.420 (0.003) |

| Single | 113 | 84 (74.34) | 29 (25.66) | |

| Divorced | 42 | 26 (61.90) | 16 (38.10) | |

| Religion | ||||

| Traditionalist And Others | 60 | 38 (63.33) | 22 (36.67) | 9.758 (0.008) |

| Christianity | 230 | 186 (80.87) | 44 (19.13) | |

| Islamic | 116 | 95 (81.90) | 21 (18.10) | |

| Maternal Age | ||||

| ≤20 Years | 33 | 30 (90.91) | 3 (9.09) | 3.293 (0.193) |

| 21–34 Years | 261 | 203 (77.78) | 58 (22.22) | |

| ≥35 Years | 112 | 86 (76.79) | 26 (23.21) | |

| Mean±SD | 29.93±6.32 | |||

| Maternal education | ||||

| Basic | 162 | 119 (73.46) | 43 (26.54) | 47.636 (<0.001) |

| No Formal Education | 75 | 42 (56.00) | 33 (44.00) | |

| Secondary | 96 | 89 (92.71) | 7 (7.29) | |

| Tertiary | 73 | 69 (94.52) | 4 (5.48) | |

| Place of Residence | ||||

| Urban | 81 | 75 (92.59) | 6 (7.41) | 11.815 (0.001) |

| Rural | 325 | 244 (75.08) | 81 (24.92) | |

| Employment Status | ||||

| Salaried Employed | 57 | 53 (92.98) | 4 (7.02) | 8.180 (0.017) |

| Self Employed | 172 | 131 (76.16) | 41 (23.84) | |

| Unemployed | 177 | 135 (76.27) | 42 (23.73) | |

| Partner education | ||||

| Basic | 112 | 76 (67.86) | 36 (32.14) | 56.110 (<0.001) |

| No Formal Education | 89 | 52 (58.43) | 37 (41.57) | |

| Secondary | 117 | 106 (90.60) | 11 (9.40) | |

| Tertiary | 88 | 85 (96.59) | 3 (3.41) | |

| Previous Delivery Place | ||||

| Facility | 282 (90.68) | 29 (9.32) | 115.651 (<0.001) | |

| Home Delivery | 37 (38.95) | 58 (61.05) | ||

| Health Facility in Community | ||||

| Yes | 206 (86.55) | 32 (13.45) | 21.772 (<0.001) | |

| No | 113 (67.26) | 55 (32.74) | ||

| ANC Attendance | ||||

| ≥8 Times | 112 (89.60) | 13 (10.40) | 85.197 (<0.001) | |

| Never Attended | 14 (33.33) | 28 (66.67) | ||

| 1–5 Times | 78 (67.24) | 38 (32.76) | ||

| 6–7 Times | 115 (93.50) | 8 (6.50) | ||

| Mean±SD | 5.57±2.82 | |||

| Time To Health Facility | ||||

| <1 Hour | 229 (94.63) | 13 (5.37) | 91.738 (<0.001) | |

| ≥1 Hour | 90 (54.88) | 74 (45.12) | ||

Table 2: Relationship of Demographic and Geographic Factors with Mother’s Place of Delivery (N=406)

| Variable | Crude Odds Ratio | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | Reference | Reference | ||

| Single | 1.72 (1.00, 2.94) | 0.048 | 2.27 (0.96, 5.36) | 0.061 |

| Divorced | 3.06 (1.51, 6.20) | 0.002 | 1.71 (0.59, 4.92) | 0.320 |

| Maternal Age | ||||

| 21–34 Years | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≤20 Years | 0.35 (0.10, 1.19) | 0.092 | 0.16 (0.03, 0.74) | 0.019 |

| Above 35 Years | 1.06 (0.62, 1.79) | 0.833 | 1.19 (0.53, 2.67) | 0.665 |

| Mean±SD | 29.93±6.32 | |||

| Place of Residence | ||||

| Urban | Reference | Reference | ||

| Rural | 4.15 (1.74, 9.89) | 0.001 | 1.76 (0.57, 5.43) | 0.328 |

| Employment Status | ||||

| Salaried Employed | Reference | Reference | ||

| Self Employed | 4.15 (1.42, 12.15) | 0.01 | 0.74 (0.14, 3.88) | 0.717 |

| Unemployed | 4.12 (1.41, 12.06) | 0.01 | 0.44 (0.08, 2.36) | 0.338 |

| Partner Education | ||||

| Tertiary | Reference | Reference | ||

| Basic | 13.42 (3.97, 45.36) | <0.001 | 5.44 (1.19, 24.97) | 0.029 |

| No Formal Education | 20.16 (5.92, 68.71) | <0.001 | 4.84 (1.06, 22.19) | 0.042 |

| Secondary | 2.94 (0.79, 10.88) | 0.106 | 1.35 (0.31, 5.87) | 0.691 |

| Children Mother Has | ||||

| ≥3 Children | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≤1 Child | 1.14 (0.57, 2.27) | 0.708 | 2.28 (0.63, 8.26) | 0.211 |

| 2 Children | 1.07 (0.63, 1.79) | 0.811 | 0.85 (0.39, 1.87) | 0.688 |

| Mean±SD | 2.70±1.33 | |||

| Previous Delivery Place | ||||

| Facility | Reference | Reference | ||

| Home Delivery | 15.24 (8.69, 26.75) | <0.001 | 2.40 (1.07, 5.38) | 0.033 |

| Health Facility in Community | ||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | ||

| No | 3.13 (1.91, 5.13) | <0.001 | 0.89 (0.41, 1.93) | 0.773 |

| ANC Attendance | ||||

| ≥8 Times | Reference | Reference | ||

| Never Attended | 17.23 (7.28, 40.76) | <0.001 | 3.91 (1.19, 12.89) | 0.025 |

| 1–5 Times | 4.20 (2.10, 8.39) | <0.001 | 2.23 (0.89, 5.60) | 0.088 |

| 6–7 Times | 0.60 (0.24, 1.50) | 0.275 | 0.36 (0.12, 1.07) | 0.065 |

| Mean±SD | 5.57±2.82 | |||

| Time To Health Facility | ||||

| <1 Hour | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥1 Hour | 14.48 (7.65, 27.41) | <0.001 | 9.10 (3.69, 22.44) | <0.001 |

Table 3: Factors associated with Home Delivery in Asutifi North District, Ghana (N=406)

Figures

Keywords

- Home delivery

- Prevalence

- Determinants

- Factors

- Ghana

Solomon Abanga1, Frank Bonsu Osei1, Bernard Aanoume Ziem1, Mohammed Abdul-Gafaru2, John Alem Ndebugri3, Gyesi Razak Issahaku2, Samuel Malogae Badiekang1,&, Samuel Dapaa2, Felix Gumaayiri Aabebe1, Samuel Kwabena Boakye-Boateng1

1Ghana Health Service, Accra, Ghana, 2Ghana Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Programme, Accra, Ghana, 3Ghana Catholic University, Sunyani, Ghana

&Corresponding author: Samuel Malogae Badiekang, Ghana Health Service, Accra, Ghana, Email: malogaesamuel@gmail.com, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1906-3859

Received: 17 Dec 2024, Accepted: 22 Aug 2025, Published: 25 Aug 2025

Domain: Maternal and Child Health

Keywords: Home delivery, prevalence, determinants, factors, Ghana

©Solomon Abanga et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Solomon Abanga et al., Determinants of home delivery practices among women in Asutifi North District, Ghana, 2020. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8(3):65. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-24-02052

Abstract

Introduction: Utilisation of skilled birth attendants in health facilities is crucial for improving maternal and child health. In low-income countries, a significant proportion of women give birth in non-health facilities compared to high-income countries. Studies in Ghana have revealed that approximately a quarter of women deliver at home. Data available in the district health information management system revealed that Asutifi North District recorded 38.5%, 41.5%, and 39.7% for skilled delivery in 2020, 2021 and 2022, respectively, which are below the national target of 65%. Various factors, including proximity to healthcare facilities, transportation costs, availability of transportation to healthcare facilities, educational attainment, previous childbirth experiences in healthcare settings, antenatal care attendance, and individual preferences, influence home delivery. The Asutifi North District faces challenges in meeting the national target for skilled deliveries, which may be attributable to these perceived determinants. To guide focused health interventions to address the problem of home delivery, we estimated its prevalence and associated factors among women attending Child Welfare Clinics (CWC) in the Asutifi North District, Ghana.

Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional study among 406 mothers attending CWC in the Asutifi North District. A multistage sampling method was used to select respondents for this study. Initially, the district was stratified into sub-districts, and mothers were randomly selected from the Child Welfare Clinic (CWC) registers and followed up to respond to a semi-structured questionnaire to assess factors associated with home delivery. Home delivery was the outcome variable and exposure variables were sociodemographic characteristics, obstetric characteristics and health facility-related factors. We performed a chi-square test and logistic regression to assess the factors associated with home delivery.

Results: A home delivery prevalence of 21.4% was estimated in Asutifi North District. Home delivery had a positive association with marital status (AOR = 2.27, 95% CI= 0.96- 5.36, p= 0.061) and a partner with basic school education level (AOR=5.44; 95% CI= 1.19- 24.97, p= 0.029). Home delivery also showed a relationship with travel time to health facilities (AOR= 9.10; 95% CI= 3.69- 22.44, p= <0.001), and never attending ANC (AOR= 3.91; 95% CI= 1.19- 12.89, p= 0.025).

Conclusion: Our study revealed that approximately a quarter of mothers delivered at home. Shorter travel time to a health facility, partner’s low educational status, ANC non-attendance have significant relationships with home delivery. The Ghana Health Service should collaborate with the district assemblies and health development partners to build health facilities close to the community members, empower communities through educational opportunities, intensify home visits to encourage ANC attendance, and increase effective counselling in maternal health services.

Introduction

In low-income countries, a significant proportion of women estimated at 68.7% do not have access to skilled delivery compared to 1.3% recorded in high-income countries [1]. In 2020, only 56.7% of deliveries in Ghana were conducted by skilled healthcare professionals; this was a concern as it did not meet the national indicator targets for skilled delivery [2]. In 2020, Asutifi North District recorded a skilled delivery of 38.5% [2]. Home delivery is birth practice where pregnant women give birth in their homes or in non-healthcare facility without the assistance of skilled personnel (midwife, a doctor, or a trained nurse) endangering the lives of mothers and babies [3]. Home deliveries have multiple risks such as haemorrhage, foetal distress, prolonged labour, obstructed labour, and infections which can all lead to maternal and neonatal mortality, still-births, and other post-delivery complications such as obstetric fistula [3–7]. Furthermore, home delivery is associated with an increased risk of third-stage delivery difficulties, such as retained placenta and postpartum haemorrhage [9]. Ghana has a high maternal mortality ratio of 319 per 100,000 live births [8], which is largely attributable to unsafe abortions, excessive bleeding, infections, delivery complications, pre-eclampsia and eclampsia [9].These unfortunate repercussions occur because of the underutilization of professional care including skilled birth attendants in Ghana [10,11].[12]Childbirths at health facilities have been regarded as one of the effective strategies to prevent maternal mortality and morbidity and enhance infant health [13]. Maternal mortality is avoidable with good antenatal care services, adequate rest and optimal nutrition during pregnancy, and mothers counselled to deliver at health institutions [14].

The choice of place of delivery among expectant mothers has been reported to be influenced by maternal age, marital status, parity, level of autonomy, employment status, contraceptive use, previous delivery place, antenatal care utilization, history of obstetric complications, quality of care, and husband’s education level [15–17]. Maternal education level is the most frequently identified factor that influences reproductive healthcare service usage [18]. The expense of care seeking for transportation, prescriptions, and opportunity costs of trip time are frequently found to be barriers to service utilization among mothers in rural areas [17].

The Asutifi North District Health Administration in an attempt to address the challenge and risks of home deliveries facilitated the training of over 80% of Community Health Nurses (CHNs) and Community Health Officers (CHOs) who understood the rural communities very well as midwives from the year 2017 to 2019. These midwives were posted to various CHPS compounds like Krakyekrom CHPS, Nsuta CHPS, and Atwedie CHPS. This has significantly reduced the number of home deliveries in these communities[2]. However, the problem of home delivery is still significant in Asutifi North District as it has not met its target for skilled delivery. The problem of home delivery may be attributable to poor road network, unavailable transport to health facilities at the time of delivery, and other inequality dimensions such as place of residence.

Understanding the determinants of home delivery is crucial for the Ghana Health Service to work together with health planning and implementing partners. The Ghana Health Service through collaboration with implementing partners, will help develop evidence-based interventions and formulate strategies and policies aimed at improving maternal healthcare. This study therefore estimated the prevalence of home delivery and associated factors among mothers attending the Child Welfare Clinic (CWC) in the Asutifi North District, Ghana.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a cross-sectional study among mothers attending CWC in the Asutifi North District of the Ahafo Region of Ghana. Quantitative data were collected for this study from 3rd to 24th July, 2020.

Study setting

The Asutifi North District is one of the six (6) administrative districts in the Ahafo Region of Ghana. The district is divided into four sub-districts with a projected population of 76,678 in the year 2020. The population of Women in Fertility Age (WiFA) was 18,403 with 2,688 estimated number of pregnancies for the year 2020. The district has 16 health facilities: two hospitals, two health centres, six clinics, one maternity home, and five CHPS compounds that provide delivery services. The district has one government hospital known as the Asutifi North District Hospital, located in the Kenyasi Sub-District, which offers a wide range of services and skilled healthcare workers, including trained birth attendants. Asutifi North District has one functional ambulance for patient referrals. The ambulance service is easily accessible in Kenyasi and Gyedu Sub-Districts, but Goamu-Koforidua and Gambia Sub-districts are rural communities that are hard to reach because of the poor nature of their road network, which makes it difficult for easy access. The district has twenty-five demarcated CHPS zones where Child Welfare Clinic (CWC) services are provided, all post-partum women and newborns are followed up and registered in the Nutrition and Child Health Registers (NCHR). Each CHPS zone has a register and a designated point where CWC services are delivered. All mothers who delivered both in health facilities and at homes converge at the CWC points to register their children and continue to receive immunization services, growth monitoring and promotion service, family planning services and others until the fifth year of each child’s life.

Study population and eligibility criteria

We studied mothers who delivered in Asutifi North District from August 2019 to 24th July 2020.

Eligibility: Mothers who met these inclusion criteria were eligible for the study: mothers who had lived in the Asutifi North District within one (1) year at the time of the interview. Mothers using CWC services two (2) months postpartum.

Exclusion: We excluded mothers who were extremely sick and unable to respond to these questions. Mothers who declined to respond to the questionnaire were excluded.

Sample size estimation

The sample size for the study was calculated using Slovin’s formula

$$n = \frac{N}{1 + Ne^2}$$

$$\frac{2688}{1 + 2688 \cdot (0.05^2)} = 348$$

where n is the estimated sample size, N is the population, and e is the margin of error. According to data from the Asutifi North District Health Directorate annual report, the prevalence (p) of skilled delivery was 31.9% in 2019. With a margin of error (e) of 5% (0.05), allowing for a 5% non-response rate, the study’s final sample size was 365. An additional 10% was estimated to cater for errors that might have emerged, considering the multistage sampling approach in this study.

Sampling process

A multistage sampling method was used to select mothers, and the district was stratified by subdistricts: Kenyasi, Gyedu, Goamu-Koforidua, and Gambia. In each subdistrict, one health facility was randomly selected, and the total sample size was allocated proportionately to the population size of the subdistrict from which the four randomly selected health facilities were chosen from the district. The names of mothers in the CWC registers were listed and selected using simple random sampling techniques. A total of 174 respondents were drawn from the health facility in Kenyasi, 84 from Gambia, 87 from Gyedu and 61 from Goamu; the number of respondents was proportionate to the population size of each subdistrict.

Data Collection tools, procedures and quality control

A semi-structured questionnaire was used to elicit responses from mothers through face-to-face interviews whilst observing the COVID-19 protocols. The researchers designed the questionnaire based on existing literature reviewed by senior researchers, pretested it, and reworded it before actual use. This ensured that the tool accurately measured the study variables to answer the research question. The research assistants were adequately trained to effectively use questionnaires to elicit correct information from the mothers. They were asked to document the consent process to assure the autonomy of respondents. The data collection tool was developed in English and administered in languages spoken and understood by the respondents. The questionnaire had three components: sociodemographic characteristics, obstetric characteristics, and health facility-related factors. The data collected included age, educational level of women and partners, religion, marital status, place of residence, parity, place of previous delivery, number of antenatal (ANC) visits, staff attitude, availability of health facilities, availability of staff, distance to the facility, and place of delivery for their most recent live births. Two investigators, including the principal investigator, addressed data quality issues and checked for consistency, validity, and accuracy.

Data management and analysis

Filled-in questionnaires were checked for completeness, coded, entered directly into Microsoft Excel 2019, and exported into STATA 18.5 software for analysis. The collected data were stored in a password-protected computer on the principal investigator’s computer which was only accessible to the investigators of this study. Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages at a 95% confidence level. We further explored the variables through cross-tabulation and Chi-square analysis was used to test relationship between home delivery and the independent variables in the study. Given that a mother delivered at home or did not deliver at home (health facility), was a binary outcome variable, we further conducted a binary logistic regression between home delivery and the predictor variables individually and reported crude odds ratios with their 95% confidence intervals. Independent variables in this study were selected based on review of literature and plausibility of their relationship with home delivery at the design stage. At the analysis stage, variables that had relationship with home delivery at the bivariable stage were included in the final model and to avoid overfitting, variable that made no difference in the final model were excluded [19,20]. The relationship between the independent variables and the outcome variable was ascertained by running a multivariable logistic regression analysis between home delivery and the independent variables, adjusted estimates were then reported. The independent variables with p-values less than 0.05 at 95% confidence levels were considered to have sufficient evidence against the null hypothesis that there is no relationship between home delivery and the independent variables[19].

Ethical Consideration

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Ghana Health Service Ethics Review Committee (GHS-ERC 045/06/20). Permission was sought from the Asutifi North District Health Directorate before data collection. Written informed consent was obtained from the respondents before they were enrolled in the study. The data were collected without personal identifiers, and the data were stored on a password-protected computer.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents, Asutifi North District, 2020

A total of 406 respondents attending the Child Welfare Clinic participated in the study. The mean age of the respondents was 29.9 ± 6.3, and 8.1% (33/406) were below 21 years of age. Among the respondents, 61.8% (251/406) were married, and 58.4% (237/406) had either basic or no formal education (Table 1).

Prevalence of Home Delivery

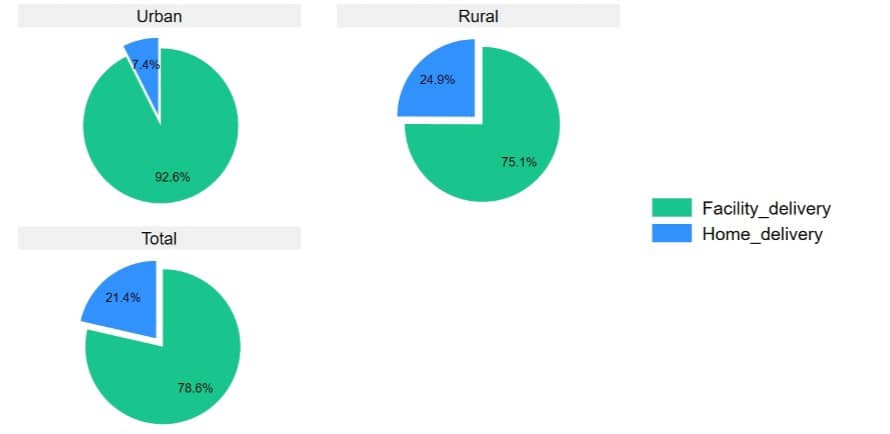

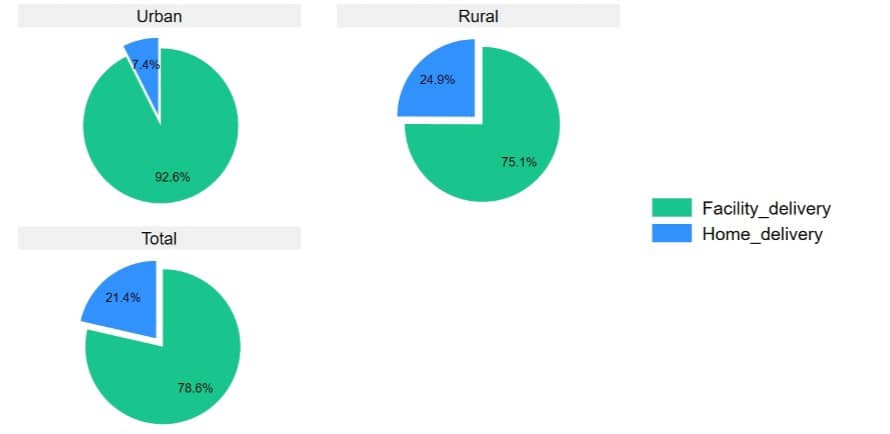

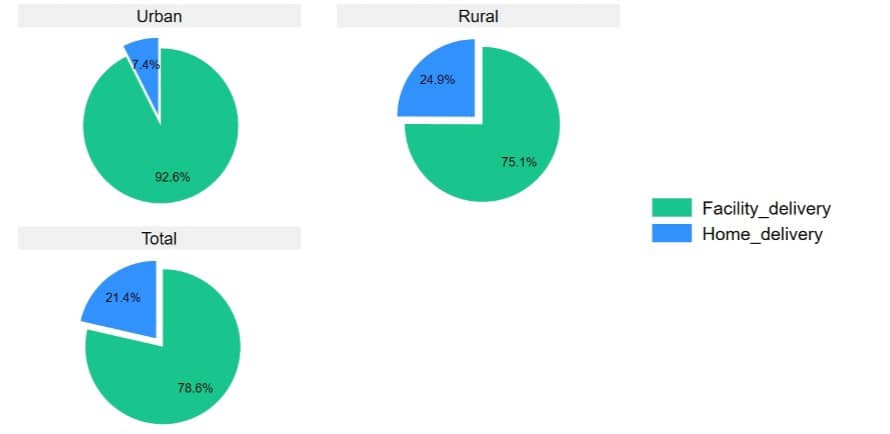

We found the general prevalence of home delivery to be 21.4% (87/406) among respondents, and 7.4% and 24.9% among urban and rural women, respectively (Figure 1).

Obstetric Characteristics of Respondents and Home Delivery, Asutifi North District, 2020

The average number of children mothers had was 2.70, and a standard deviation of 1.33, and 48.8% (198/406) of mothers had three or more children. We found that 44.0% (33/75) of mothers without formal education delivered at home, and 56.0% (42/75) of mothers without formal education delivered at health facilities. Among mothers in rural areas, 24.9% (81/325) delivered at home and 75.1% (244/325) delivered at healthcare facilities. We also found that 41.6% (37/89) of the mothers whose partners had no formal education delivered at home and 58.4% (76/89) delivered at healthcare facilities. Among the mothers who were self-employed, 23.8% (41/172) delivered at home, 76.2% (131/172) delivered at healthcare facilities. An estimated 61.1% (58/95) of mothers who previously delivered at home again delivered in the house and 38.9% (37/95) currently delivered in healthcare facilities. Among mothers who did not have health facilities in their communities, 32.7% (55/168) delivered at home and 67.3% (113/168) delivered in healthcare facilities. The average ANC attendance among mothers was 5.57±2.82 and 45.1% (74/164) of mothers who had to travel more than one hour to reach the health facility delivered at home, and 54.9% (90/164) delivered in healthcare facilities (Table 2).

Factors associated with home delivery among mothers attending CWC

Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to measure the level of association between the explanatory and dependent variables (Table 3). We observed that single women had 2.27 times the odds of delivering at home compared to married women at the adjusted level (AOR = 2.27; 95% CI 0.96 – 5.36, p = 0.061). Women whose partners had basic education level at the adjusted level had 5.44 times the odds of delivering at home compared to mothers whose partners had tertiary education (AOR = 5.44; 95% CI = 1.19 – 24.97, p = 0.029). Similarly, compared to those mothers whose partners had tertiary education, those whose partners had no formal education had 4.84 higher odds of delivering at home (AOR=4.84, 95%CI = 1.06-22.19, p=0.042). Mothers who previously delivered at home had 2.40 times the odds of delivering at home compared to mothers who previously delivered in a health facility (AOR= 2.40; 95% CI= 1.07- 5.38, p = 0.033). Mothers who had never attended ANC had 3.91 times the odds of delivering at home compared to mothers who had attended ANC eight times or more (AOR = 3.91; 95% CI= 1.19- 12.89, p= 0.025). Mothers who had to travel for 1 hour or more with an available means to a health facility had 9.10 times the odds of delivering at home compared to mothers who had to travel less than one hour to a health facility (AOR= 9.10; CI= 3.69- 22.44, p< 0.001). Mothers aged 20 years or younger have 84% lower odds of delivering from home compared to mothers aged 21-34 years (AOR=0.16, 95% CI=0.03-0.74, p=0.019).

Discussion

Our study investigated the prevalence of home delivery and associated factors among mothers attending Child Welfare Clinics (CWC). We found that almost a quarter of mothers delivered at home. Our finding is consistent with a study by Yetwale and others in 2020 where the prevalence level of home delivery was less than 37% in Southwest Ethiopia[21]. Meanwhile, a more recent study by Maximore and colleagues in 2022 reported above 90% of previous home deliveries. The disparity in the prevalence rates reported in our study may stem from differences in the characteristics of the study population. High (89.7%) ANC attendance among our study participants may have accounted for the low home delivery of less than 30.0% compared to the 90.6% home delivery [1]. Ghana has made significant strides towards reducing home deliveries and improving institutional deliveries conducted by a skilled birth attendant[22]; specific actions were taken by the Ministry of Health (MOH) and Ghana Health Service (GHS). These actions included: training of midwives and collaboration with the Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies (MMDAs) to construct CHPS compounds where primary healthcare services are delivered to facilitate the achievement of Universal Health Coverage. Naturing a health system that provides responsive health services and working with multi-stakeholders to address the determinants of home delivery will help Ghana to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity rapidly.

We found that single mothers had increased odds of delivering at home compared to married mothers though not statistically significant. Our finding validates a study by Lanza-León & Cantarero-Prieto in 2024 which reported the health hurdles of single parents [23]. This emphasises the need to redefine our health education programmes to promote partner and family support for pregnant women to promote health facility deliveries in Ghana [24].

Respondents below twenty-one years old were a statistically significant negative predicator of home delivery. A study in Ghana reported age was not a determinant of home delivery [25]. Utilization of facility-based delivery by women is attributable to: the role of husbands and autonomy in decision-making, personal desire for healthcare facility delivery, health insurance schemes, perceived low quality of care by traditional birth attendants (TBAs) or at home, perceived quality of care at health facilities. Other facilitators include: perceived risk or complications during birth, desire for modernity and better outcomes, social connections with healthcare providers, availability of transport to health facilities [26,27]. Younger women’s uptake of facility delivery is a positive health seeking behaviour that promotes deliveries by skilled birth attendants and a requisite to reduce maternal mortality [28], as a public health challenge. The Ghana Health Service should intensify its health promotion activitiesto promote and sustain health facility delivery by young expectant mothers, as well as provide more responsive and inclusive services that will encourage young expectant mothers to deliver at health facilities. Future studies which examine facilitators of health facility delivery by young people can be useful.

Partner education level is also an important factor that can influence home delivery. A similar finding has been reported that mothers whose husbands had no formal education were less likely to have their wives deliver in health facility settings [17]. This could be due to educated husbands appreciating the importance of institutional delivery and indulging in using maternal health services. Several systematic reviews on determinants of health facility delivery have shown that the husband’s education consistently increases health facility use [29–32]. Therefore, it is important for health services to consider partner involvement during antenatal care services and community health outreach programs to ensure that partners buy health services, especially when giving birth in a health facility.

Mothers who previously delivered at home had increased odds of home delivery. This reiterates the existing literature, which indicates that health-seeking behaviours have complex relationships [33]. Without planned efforts to reach mothers and expectant mothers who deliver at home, they will repeatedly put their lives at risk by delivering at home. Since these mothers are in the communities, healthcare workers should take advantage of the contact they make with these women during home visits and community outreach programmes to reach them and their spouses to promote uptake of skilled delivery.

Mothers who never attended ANC during their pregnancy were more likely to deliver at home compared to mothers who visited ANC to receive health services. Attending ANC 1-5 times was associated with higher odds of home delivery while attending ANC 6-7 times was protective against home delivery though not statistically significant. A recent study in 2021 validates our findings and reported that lower attendance to ANC care was linked to a higher chance of home delivery through an analysis of the DHS dataset for Ghana [34]. Expectant mothers should therefore be encouraged through health promotion activities to attend ANC services at least 8 times or more for it to improve health facility-based delivery and reduce home deliveries. Mothers who visited ANC may have been educated on the importance of institutional delivery, which improved facility delivery. ANC provides essential health checks, education, and support during pregnancy, fostering a connection between women and healthcare providers. This relationship often encourages women to deliver in a healthcare facility, as asserted by an earlier study in northern Uganda [35]. Ghana’s free maternal and child health service policy, which improves access to care and financial risk protection should be continually improved to address bottlenecks of National Health Insurance (NHIS) reimbursement challenges, structural, systemic issues, and others reported by [36]. An improved policy and continued promotion of ANC attendance in all health service delivery outlets will promote and reinforce health facility delivery and to propel Ghana to achieve SDG 5

In this study, travel time to health facilities was significantly associated with home delivery. In our study, mothers who travelled more than one hour to a health facility using the most available means had 9.1 times increased odds of delivering at home than those who travelled for less than one hour. This finding is consistent with other studies which found travel time and distance or proximity to healthcare facilities as factors that influence both accessibility to healthcare and health outcomes [37–39]. Longer distances to healthcare facilities increase travel time and put a huge burden on mothers, coupled with poor road networks and transportation systems, which make them risk their lives to deliver at home. When a woman lives close to a health facility, it reduces barriers to accessing maternal care during labour. Shorter travel times and distances decrease the risk of delays in reaching the facility, thereby ensuring timely and safer deliveries in healthcare facilities. Shorter travel times below 1 hourfacilitates better utilization of health services as it minimizes transportation challenges and encourages women to seek skilled care during childbirth, ultimately contributing to improved maternal and neonatal outcomes. Findings from a more recent study confirm the findings in our study that distance is a significant inequality to the achievement of optimal maternal healthcare in Nepal [40].

However, our findings should be interpreted with caution since they cannot infer causality since this was a cross-sectional study. We recommend future mixed-method longitudinal studies. Also responses from mothers can be subjective and prone to information bias such as response bias. Given this, we interviewed mothers who were using CWC services two (2) months postpartum and they were encouraged to give honest responses. To complement their responses and reduce potential biases, well-trained research assistants reviewed the CWC register and Maternal and Child Health Booklets to confirm home delivery. Our study tool in some instances was translated from English to the local language by the research assistants which might have introduced some form of bias. However all the research assistants were indigens from different communities with tertiary education who also understood the local languages very well which minimized the anticipated bias.

Conclusion

We observed a home delivery prevalence of over 21% in the Asutifi North District. Proximity to a health facility, partner’s educational status, maternal age, ANC attendance, and previous place of delivery were factors that influenced home delivery. The Ghana Health Service should work with the District and Municipal Assemblies to build health facilities close to the community members to improve proximity, ANC attendance, and reduce home delivery. The municipal and district assemblies should empower women and increase educational opportunities for both males and females to increase good health-seeking behaviour such as utilization of skilled birth attendants.

What is already known about the topic

In low-income countries, a significant proportion of mothers deliver in non-health facilities (68.7%) compared to high-income countries (1.3%)

It is already known that about a quarter of women still deliver at home in Ghana

What this study adds

More mothers preferred to deliver in health facilities in the Asutifi North District of Ghana.

Home delivery had a strong relationship with longer travel time to a health facility and previous home deliveries

ANC attendance from 0 – 5 times increased the chances of home delivery

Partner education level influenced home delivery.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the research assistants who were recruited for this study and their time and commitment throughout the study. Our sincere gratitude goes to all the study participants, the District Director of Health Service (DDHS) for Asutifi North District, the Asutifi North District Health Management Team, the Budget Management Centres (BMC), and all the healthcare workers who supported us throughout this study’s stages.

Authors´ contributions

Solomon Abanga conceived and designed the study, collected the data with Samuel Malogae Badiekang did the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft. Samuel K. Boakye-Boateng, Abdul-Gafaru Mohammed, Bernard Ziem, Frank Bonsu Osei and John Alem Ndebugri provided technical inputs during the study’s conceptualisation and made revisions to this manuscript. Samuel Malogae-Badiekang, Felix Gumaayiri Aabebe, and Samuel Dapaa assisted with the statistical analysis and draft of the manuscript. All authors have read, reviewed, and provided technical inputs for the final version of the manuscript.

List of Abbreviations

ANC: Antenatal Care

AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio

BMC: Budget Management Centres

CHPS: Community-Based Health Planning and Services

CHN: Community Health Nurses

CHO: Community Health Officers

CI: Confidence Interval

CWC: Child Welfare Clinic

DDHS: District Director of Health Service

DHIMS: District Health Information Management System

DHMT: District Health Management Team

DHS: Demographic and Health Survey

GHS: Ghana Health Service

GHS-ERC: Ghana Health Service Ethics Review Committee

JEIPH: Journal of Epidemiology Interventional and Public Health

MMDAs: Metropolitan, Municipal, and District Assemblies

MOH: Ministry of Health

NCHR: Nutrition and Child Health Register

RC: Reference Category

SD: Standard Deviation

SDG: Sustainable Development Goals

WHO: World Health Organisation

| Variable | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | ||

| ≤20 Years | 33 | 8.13 |

| 21-34 Years | 261 | 64.28 |

| ≥35 Years | 112 | 27.59 |

| Mean±SD | 29.93±6.32 | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 251 | 61.82 |

| Single | 113 | 27.83 |

| Divorced | 42 | 10.34 |

| Maternal education | ||

| Basic | 162 | 39.90 |

| No Formal Education | 75 | 18.47 |

| Secondary | 96 | 23.65 |

| Tertiary | 73 | 17.98 |

| Religion | ||

| Traditional and Others | 60 | 14.78 |

| Christianity | 230 | 56.65 |

| Islamic | 116 | 28.57 |

| Place of residence | ||

| Urban | 81 | 19.95 |

| Rural | 325 | 80.05 |

| Employment status | ||

| Salaried Employed | 57 | 14.04 |

| Self Employed | 172 | 42.36 |

| Unemployed | 177 | 43.60 |

| Partner education | ||

| Basic | 112 | 27.59 |

| No Formal Education | 89 | 21.92 |

| Secondary | 117 | 28.82 |

| Tertiary | 88 | 21.67 |

| No. of children mother has | ||

| ≤1 Child | 61 | 15.02 |

| 2 Children | 147 | 36.21 |

| ≥3 Children | 198 | 48.77 |

| Mean±SD | 2.70±1.33 | |

| Variable | Total | Facility n (%) | Home n (%) | Chi square (p value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 251 | 209 (83.27) | 42 (16.73) | 11.420 (0.003) |

| Single | 113 | 84 (74.34) | 29 (25.66) | |

| Divorced | 42 | 26 (61.90) | 16 (38.10) | |

| Religion | ||||

| Traditionalist And Others | 60 | 38 (63.33) | 22 (36.67) | 9.758 (0.008) |

| Christianity | 230 | 186 (80.87) | 44 (19.13) | |

| Islamic | 116 | 95 (81.90) | 21 (18.10) | |

| Maternal Age | ||||

| ≤20 Years | 33 | 30 (90.91) | 3 (9.09) | 3.293 (0.193) |

| 21–34 Years | 261 | 203 (77.78) | 58 (22.22) | |

| ≥35 Years | 112 | 86 (76.79) | 26 (23.21) | |

| Mean±SD | 29.93±6.32 | |||

| Maternal education | ||||

| Basic | 162 | 119 (73.46) | 43 (26.54) | 47.636 (<0.001) |

| No Formal Education | 75 | 42 (56.00) | 33 (44.00) | |

| Secondary | 96 | 89 (92.71) | 7 (7.29) | |

| Tertiary | 73 | 69 (94.52) | 4 (5.48) | |

| Place of Residence | ||||

| Urban | 81 | 75 (92.59) | 6 (7.41) | 11.815 (0.001) |

| Rural | 325 | 244 (75.08) | 81 (24.92) | |

| Employment Status | ||||

| Salaried Employed | 57 | 53 (92.98) | 4 (7.02) | 8.180 (0.017) |

| Self Employed | 172 | 131 (76.16) | 41 (23.84) | |

| Unemployed | 177 | 135 (76.27) | 42 (23.73) | |

| Partner education | ||||

| Basic | 112 | 76 (67.86) | 36 (32.14) | 56.110 (<0.001) |

| No Formal Education | 89 | 52 (58.43) | 37 (41.57) | |

| Secondary | 117 | 106 (90.60) | 11 (9.40) | |

| Tertiary | 88 | 85 (96.59) | 3 (3.41) | |

| Previous Delivery Place | ||||

| Facility | 282 (90.68) | 29 (9.32) | 115.651 (<0.001) | |

| Home Delivery | 37 (38.95) | 58 (61.05) | ||

| Health Facility in Community | ||||

| Yes | 206 (86.55) | 32 (13.45) | 21.772 (<0.001) | |

| No | 113 (67.26) | 55 (32.74) | ||

| ANC Attendance | ||||

| ≥8 Times | 112 (89.60) | 13 (10.40) | 85.197 (<0.001) | |

| Never Attended | 14 (33.33) | 28 (66.67) | ||

| 1–5 Times | 78 (67.24) | 38 (32.76) | ||

| 6–7 Times | 115 (93.50) | 8 (6.50) | ||

| Mean±SD | 5.57±2.82 | |||

| Time To Health Facility | ||||

| <1 Hour | 229 (94.63) | 13 (5.37) | 91.738 (<0.001) | |

| ≥1 Hour | 90 (54.88) | 74 (45.12) | ||

| Variable | Crude Odds Ratio | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | Reference | Reference | ||

| Single | 1.72 (1.00, 2.94) | 0.048 | 2.27 (0.96, 5.36) | 0.061 |

| Divorced | 3.06 (1.51, 6.20) | 0.002 | 1.71 (0.59, 4.92) | 0.320 |

| Maternal Age | ||||

| 21–34 Years | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≤20 Years | 0.35 (0.10, 1.19) | 0.092 | 0.16 (0.03, 0.74) | 0.019 |

| Above 35 Years | 1.06 (0.62, 1.79) | 0.833 | 1.19 (0.53, 2.67) | 0.665 |

| Mean±SD | 29.93±6.32 | |||

| Place of Residence | ||||

| Urban | Reference | Reference | ||

| Rural | 4.15 (1.74, 9.89) | 0.001 | 1.76 (0.57, 5.43) | 0.328 |

| Employment Status | ||||

| Salaried Employed | Reference | Reference | ||

| Self Employed | 4.15 (1.42, 12.15) | 0.01 | 0.74 (0.14, 3.88) | 0.717 |

| Unemployed | 4.12 (1.41, 12.06) | 0.01 | 0.44 (0.08, 2.36) | 0.338 |

| Partner Education | ||||

| Tertiary | Reference | Reference | ||

| Basic | 13.42 (3.97, 45.36) | <0.001 | 5.44 (1.19, 24.97) | 0.029 |

| No Formal Education | 20.16 (5.92, 68.71) | <0.001 | 4.84 (1.06, 22.19) | 0.042 |

| Secondary | 2.94 (0.79, 10.88) | 0.106 | 1.35 (0.31, 5.87) | 0.691 |

| Children Mother Has | ||||

| ≥3 Children | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≤1 Child | 1.14 (0.57, 2.27) | 0.708 | 2.28 (0.63, 8.26) | 0.211 |

| 2 Children | 1.07 (0.63, 1.79) | 0.811 | 0.85 (0.39, 1.87) | 0.688 |

| Mean±SD | 2.70±1.33 | |||

| Previous Delivery Place | ||||

| Facility | Reference | Reference | ||

| Home Delivery | 15.24 (8.69, 26.75) | <0.001 | 2.40 (1.07, 5.38) | 0.033 |

| Health Facility in Community | ||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | ||

| No | 3.13 (1.91, 5.13) | <0.001 | 0.89 (0.41, 1.93) | 0.773 |

| ANC Attendance | ||||

| ≥8 Times | Reference | Reference | ||

| Never Attended | 17.23 (7.28, 40.76) | <0.001 | 3.91 (1.19, 12.89) | 0.025 |

| 1–5 Times | 4.20 (2.10, 8.39) | <0.001 | 2.23 (0.89, 5.60) | 0.088 |

| 6–7 Times | 0.60 (0.24, 1.50) | 0.275 | 0.36 (0.12, 1.07) | 0.065 |

| Mean±SD | 5.57±2.82 | |||

| Time To Health Facility | ||||

| <1 Hour | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥1 Hour | 14.48 (7.65, 27.41) | <0.001 | 9.10 (3.69, 22.44) | <0.001 |

References

- Maximore LS, Mohammed AG, Issahaku GR, Sackey S, Kenu E. Prevalence and determinants of home delivery among reproductive age women, Margibi County, Liberia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet]. 2022 Aug 19 [cited 2025 Aug 24];22(1):653. doi:10.1186/s12884-022-04975-7

- Asutifi North District Assembly (Ghana). DHIMS 2. Percentage Skilled Deliveries, Asutifi North District, 2023.

- Lawn JE, Lee AC, Kinney M, Sibley L, Carlo WA, Paul VK, Pattinson R, Darmstadt GL. Two million intrapartum-related stillbirths and neonatal deaths: Where, why, and what can be done? Int J Gynaecol Obstet [Internet]. 2009 Oct 6 [cited 2025 Aug 25];107 Suppl 1:S5–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.07.016

- Aminu M, Unkels R, Mdegela M, Utz B, Adaji S, Van Den Broek N. Causes of and factors associated with stillbirth in low‐ and middle‐income countries: a systematic literature review. BJOG [Internet]. 2014 Sep [cited 2025 Aug 25];121 Suppl 4:141–53. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12995

- Stones W, Visser GHA, Theron G, FIGO Safe Motherhood and Newborn Health Committee. FIGO statement: staffing requirements for delivery care, with special reference to low‐ and middle‐income countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet [Internet]. 2019 Mar 30 [cited 2025 Aug 25];146(1):3–7. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12815

- Buchmann EJ, Stones W, Thomas N. Preventing deaths from complications of labour and delivery. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol [Internet]. 2016 Jun 26 [cited 2025 Aug 25];36:103–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2016.05.012

- Sood G, Argani C, Ghanem KG, Perl TM, Sheffield JS. Infections complicating cesarean delivery. Curr Opin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2018 Aug [cited 2025 Aug 25];31(4):368–76. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000472

- Gudu W, Addo B. Factors associated with utilization of skilled service delivery among women in rural Northern Ghana: a cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet]. 2017 May 31 [cited 2025 Aug 25];17(1):159. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1344-2

- World Health Organization. Maternal mortality 2024 [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2025 Apr 7 [cited 2025 Aug 25]. [about 4 screens]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality

- Nakua EK, Sevugu JT, Dzomeku VM, Otupiri E, Lipkovich HR, Owusu-Dabo E. Home birth without skilled attendants despite millennium villages project intervention in Ghana: insight from a survey of women’s perceptions of skilled obstetric care. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet]. 2015 Oct 7 [cited 2025 Aug 25];15(1):243. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0674-1

- Lee QY, Odoi AT, Opare‐Addo H, Dassah ET. Maternal mortality in Ghana: a hospital-based review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand [Internet]. 2012 Jul 27 [cited 2025 Aug 25];91(1):87–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01249.x

- DHIMS 2 (Ghana). Percentage Skilled Deliveries [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 04]. Available from: https://dhims.chimgh.org/dhims/dhis-web-data-visualizer/index.html

- Dankwah E, Zeng W, Feng C, Kirychuk S, Farag M. The social determinants of health facility delivery in Ghana. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2019 Jul 10 [cited 2025 Aug 25];16(1):101. doi: 10.1186/s12978-019-0753-2

- World Health Organization. Maternal mortality: Evidence brief 2019. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2019 Nov 11 [cited 2025 Nov 11];4 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/W2019

- Baba MI, Kyei KA, Kyei JB, Daniels J, Biney IJK, Oswald J, Tschida P, Brunet M. Diversities in the place of delivery choice: a study among expectant mothers in Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet]. 2022 Nov 25 [cited 2025 Aug 26];22(1):875. doi: 10.1186/s12884-022-05158-0

- Manyeh AK, Akpakli DE, Kukula V, Ekey RA, Narh-Bana S, Adjei A, Gyapong M. Socio-demographic determinants of skilled birth attendant at delivery in rural southern Ghana. BMC Res Notes [Internet]. 2017 Dec [cited 2025 Aug 26];10(1):268. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2591-z

- Kifle MM, Kesete HF, Gaim HT, Angosom GS, Araya MB. Health facility or home delivery? Factors influencing the choice of delivery place among mothers living in rural communities of Eritrea. J Health Popul Nutr [Internet]. 2018 Oct 22 [cited 2025 Aug 26];37(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s41043-018-0153-1

- Rezaeizadeh G, Mansournia MA, Keshtkar A, Farahani Z, Zarepour F, Sharafkhah M, Kelishadi R, Poustchi H. Maternal education and its influence on child growth and nutritional status during the first two years of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine [Internet]. 2024 May [cited 2025 Aug 26];71:102574. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102574

- Kirkwood B, Sterne J. Essential medical statistics [Internet]. 2nd ed. Oxford (UK): Blackwell Science; 2003 [cited 2025 Aug 26]. 513 p. Available from: http://dickyricky.com/books/medical/Essential%20Medical%20Statistics%20-%20Betty%20Kirkwood.pdf

- Stoltzfus JC. Logistic regression: a brief primer. Acad Emerg Med [Internet]. 2011 Oct 13 [cited 2025 Aug 26];18(10):1099–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01185.x

- Yetwale A, Melkamu E, Ketema W. Prevalence and associated factors of home delivery among women at Jimma town, Jimma Zone, Southwest Ethiopia. IPCB [Internet]. 2020 Aug 25 [cited 2025 Aug 26];6(4):114–9. doi: 10.15406/ipcb.2020.06.00207

- Dzomeku VM, Duodu PA, Okyere J, Aduse-Poku L, Dey NEY, Mensah ABB, Nakua EK, Agbadi P, Nutor JJ. Prevalence, progress, and social inequalities of home deliveries in Ghana from 2006 to 2018: insights from the multiple indicator cluster surveys. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet]. 2021 Jul 10 [cited 2025 Aug 26];21(1):518. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03989-x

- Lanza-León P, Cantarero-Prieto D. The loud silent side of single parenthood in Europe: health and socio-economic circumstances from a gender perspective. J Fam Econ Iss [Internet]. 2024 Apr 18 [cited 2025 Aug 26];46(2):479–91. doi: 10.1007/s10834-024-09954-y

- Adu J, Owusu MF. How do we improve maternal and child health outcomes in Ghana? Health Plann Manage [Internet]. 2023 Mar 28 [cited 2025 Aug 26];38(4):898–903. doi: 10.1002/hpm.3639

- Budu E, Ahinkorah BO, Okyere J, Seidu AA, Aboagye RG, Yaya S. High risk fertility behaviour and health facility delivery in West Africa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet]. 2023 Dec 7 [cited 2025 Aug 26];23(1):842. doi: 10.1186/s12884-023-06107-1

- Bohren MA, Hunter EC, Munthe-Kaas HM, Souza JP, Vogel JP, Gülmezoglu AM. Facilitators and barriers to facility-based delivery in low- and middle-income countries: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2014 Sep 19 [cited 2025 Aug 26];11(1):71. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-11-71

- Zin T, Mudin K, Myint T, Naing Daw KS, Sein T, Shamsul B. Influencing factors for household water quality improvement in reducing diarrhoea in resource-limited areas. WHO South-East Asia J Public Health [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2025 Aug 26];2(1):6. doi: 10.4103/2224-3151.115828

- Chinkhumba J, De Allegri M, Muula AS, Robberstad B. Maternal and perinatal mortality by place of delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: a meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2014 Sep 28 [cited 2025 Aug 26];14(1):1014. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1014

- Gabrysch S, Campbell OM. Still too far to walk: Literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet]. 2009 Aug 11 [cited 2025 Aug 26];9(1):34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-34

- Lateef MA, Kuupiel D, Mchunu GG, Pillay JD. Utilization of antenatal care and skilled birth delivery services in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2024 Apr 3 [cited 2025 Aug 26];21(4):440. doi: 10.3390/ijerph21040440

- Moyer CA, Mustafa A. Drivers and deterrents of facility delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2013 Aug 20 [cited 2025 Aug 26];10(1):40. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-10-40

- Nigusie A, Azale T, Yitayal M. Institutional delivery service utilization and associated factors in Ethiopia: a systematic review and META-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet]. 2020 Jun 15 [cited 2025 Aug 26];20(1):364. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03032-5

- Marte Marteau TM, Rutter H, Marmot M. Changing behaviour: an essential component of tackling health inequalities. BMJ [Internet]. 2021 Feb 10 [cited 2025 Aug 26];372:n332. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n332

- Ahinkorah BO, Seidu AA, Budu E, Agbaglo E, Appiah F, Adu C, Archer AG, Ameyaw EK. What influences home delivery among women who live in urban areas? Analysis of 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey data. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2021 Jan 4 [cited 2025 Aug 26];16(1):e0244811. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244811

- Ediau M, Wanyenze RK, Machingaidze S, Otim G, Olwedo A, Iriso R, Tumwesigye NM. Trends in antenatal care attendance and health facility delivery following community and health facility systems strengthening interventions in Northern Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet]. 2013 Oct 18 [cited 2025 Aug 26];13(1):189. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-189

- Alatinga KA, Hsu V, Abiiro GA, Kanmiki EW, Gyan EK, Moyer CA. Why “free maternal healthcare” is not entirely free in Ghana: a qualitative exploration of the role of street-level bureaucratic power. Health Res Policy Syst [Internet]. 2024 Oct 9 [cited 2025 Aug 26];22(1):142. doi: 10.1186/s12961-024-01233-4

- Olaleye SO, Aroyewun TF, Osman RA. Sudan’s maternal health needs urgent attention amid armed conflict. Lancet [Internet]. 2023 Sep 9 [cited 2025 Aug 26];402(10405):848–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01697-5

- Nigussie Teklehaymanot A, Kebede A, Hassen K. Factors associated with institutional delivery service utilization in Ethiopia. Int J Womens Health [Internet]. 2016 Mar 30 [cited 2025 Aug 26];8:463–75. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S109498

- Chambers D, Cantrell A, Baxter SK, Turner J, Booth A. Effects of increased distance to urgent and emergency care facilities resulting from health services reconfiguration: a systematic review. Health Serv Deliv Res [Internet]. 2020 Jul [cited 2025 Aug 26];8(31):1–86. doi: 10.3310/hsdr08310

- Ali S, Thind A, Stranges S, Campbell MK, Sharma I. Investigating health inequality using trend, decomposition and spatial analyses: a study of maternal health service use in Nepal. Int J Public Health [Internet]. 2023 Jun 2 [cited 2025 Aug 26];68:1605457. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2023.1605457