Research | Open Access | Volume 8 (3): Article 66 | Published: 26 Jul 2025

Adult pneumococcal vaccination in Northeast Nigeria: Insights into physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and clinical practices

Menu, Tables and Figures

Navigate this article

Tables

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 20–29 | 14 | 19.2 |

| 30–39 | 44 | 60.3 |

| 40–49 | 13 | 17.8 |

| 50–59 | 2 | 2.7 |

| ≥60 | 0 | 0 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 16 | 21.9 |

| Female | 57 | 78.1 |

| Years of medical practice (Years) | ||

| 1–5 | 30 | 41.1 |

| 6–10 | 23 | 31.5 |

| 11–15 | 15 | 15 |

| 16–20 | 3 | 4.1 |

| >21 | 2 | 2.7 |

| Specialty | ||

| General Practice | 28 | 38.3 |

| Internal Medicine | 15 | 20.6 |

| Infectious Diseases | 2 | 2.7 |

| Pulmonology | 4 | 5.5 |

| Others | 24 | 32.9 |

| Current practice setting | ||

| Primary healthcare setting | 3 | 4.1 |

| Secondary healthcare setting | 16 | 21.9 |

| Tertiary healthcare setting | 51 | 69.9 |

| Private healthcare setting | 3 | 4.1 |

Table 1: Sociodemographic and Professional Characteristics of Study Participants

| Variables | Knowledge | Practice | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cOR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Age (years) | 1.06 (0.97–1.16) | 0.207 | 1.09 (0.96–1.23) | 1.02 (0.94–1.11) | 0.603 | 1.05 (0.94–1.18) |

| Male vs Female | 0.39 (0.13–1.19) | 0.098 | 0.33 (0.10–1.12) | 4.45 (1.34–14.8) | 0.015 | 5.87 (1.50–23.1) |

| >10 yrs vs ≤10 yrs of practice | 0.66 (0.16–2.73) | 0.566 | 0.97 (0.18–5.28) | 0.87 (0.24–3.14) | 0.834 | 0.97 (0.21–4.43) |

| General practice vs Other | 0.35 (0.09–1.42) | 0.141 | 0.23 (0.04–1.20) | 1.92 (0.58–6.40) | 0.285 | 2.93 (0.81–10.6) |

| Tertiary vs Primary/Secondary setting | 0.47 (0.10–2.18) | 0.335 | 0.33 (0.06–1.86) | 2.08 (0.60–7.25) | 0.245 | 2.95 (0.73–11.3) |

Note: cOR = crude odds ratio; aOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. Knowledge was analysed using binary logistic regression, while practice (recommendation frequency: Never → Often) was analysed using ordinal logistic regression with logit link. In both models, multivariate analysis adjusted for age, sex, years of practice, specialty, and workplace setting.

Table 2: Determinants of physicians’ knowledge and recommendation practices for adult pneumococcal vaccination

Figures

Figure 1: Map of Ghana showing Western North Region and districts

Keywords

- Adult pneumococcal vaccine

- Physician knowledge

- Northeast Nigeria

Ibrahim Adamu1,2, Imrana Alhassan Bojude3, Adamu Ali Bukar4, Kabiru Idris5, Umar Mohammed Hassan6, Dalhat Ibrahim Sulaiman7, Abdulwahab Aliyu8

1Department of Medicine, Federal Teaching Hospital, Ashaka road, Gombe, Gombe, Nigeria, 2Department of Medicine, Gombe State University, Tudun Wada, Gombe, Gombe, Nigeria, 3National AIDS and STDS Control Programme, Abuja, Nigeria, 4Taraba State Health Services Management Board, Taraba, Nigeria, 5Department of Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital, Borno State, Nigeria, 6Department of Medical Microbiology, Federal Teaching Hospital, Ashaka road, Gombe, Gombe State, Nigeria, 7Department of Family Medicine, Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Teaching Hospital, Bauchi, Bauchi, Nigeria, 8Department of Pharmaceutical Microbiology and Biotechnology, Gombe State University, Tudun Wada, Gombe, Gombe, Nigeria.

&Corresponding author: Ibrahim Adamu, Department of Medicine, Federal Teaching Hospital, Ashaka road, Gombe, Gombe, Nigeria Email: ibbomala@gsu.edu.ng ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-8315-2462

Received: 25 Apr 2025 Accepted: 25 Aug 2025 Published: 26 Aug 2025

Domain: Vaccine Preventable Diseases

Keywords: Adult pneumococcal vaccine, physician knowledge, Northeast Nigeria

©Ibrahim Adamu et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Ibrahim Adamu et al. Adult pneumococcal vaccination in Northeast Nigeria: Insights into physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and clinical practices. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8(3):66. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00104

Abstract

Introduction: Streptococcus pneumoniae is a major cause of lower respiratory tract infections, invasive pneumococcal diseases (IPDs), and rising antibiotic resistance. Although adult pneumococcal vaccination is an effective preventive strategy, its uptake in Nigeria—especially in the Northeast—remains low. Physicians play a critical role in promoting vaccine uptake, yet data on their knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) are limited. We assessed the physicians’ KAP regarding adult pneumococcal vaccination in Northeast Nigeria and identified barriers to inform strategies for improved uptake.

Methods: A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted among 73 physicians across all healthcare levels in Northeast Nigeria using a self-administered electronic questionnaire. Data were analysed with SPSS v26. Knowledge was assessed based on awareness of vaccine types, target groups, and guidelines; attitude on perceived importance and prescribing confidence; and practice on prescription behaviours and influencing factors.

Results: Most respondents (60.3%) were aged 30–39 years and worked as general practitioners (38.3%) or internists (20.6%). Only 5.5% had received formal training on adult pneumococcal vaccination, and 34.2% were unaware of any pneumococcal vaccine. Just 9.6% correctly identified all high-risk adult groups. Although 79.5% viewed the vaccine as important, prescription rates were low. Key barriers included lack of training, poor guideline dissemination, limited vaccine access, and misconceptions about eligible populations.

Conclusion: Despite favourable attitudes, significant knowledge and practice gaps exist among physicians. Targeted training, clearer national guidelines, and improved vaccine availability are essential to enhance adult vaccination rates and reduce the burden of pneumococcal disease in Northeast Nigeria.

Introduction

Pneumococcal infection typically begins with colonizing the nasopharynx and oropharynx in healthy individuals. In susceptible individuals, the bacteria can be aspirated into the lower respiratory tract, leading to infection [1]. Globally, Streptococcus pneumoniae accounts for more than half of the morbidity and mortality associated with lower respiratory tract infections, surpassing the combined impact of other bacterial pathogens [2]. Although its burden is well-documented among children, the disease also significantly affects adults—particularly older adults and those with underlying comorbidities [3–5]. Internationally, pneumococcal disease (PD) exhibits a bimodal distribution, with the highest incidence in the very young and the elderly. In older adults, the burden is primarily driven by pneumococcal pneumonia (PP), facilitated by age-related immune decline, comorbid conditions, and impaired respiratory defences [5]. In Nigeria, research has often focused on children; however, emerging evidence highlights the adult population as significantly affected. A study from Northern Nigeria reported a mean age of 41 years among hospitalised pneumococcal pneumonia patients [6], suggesting that adults—including middle-aged and older individuals—are an under-recognised but vulnerable group. Despite this, adult pneumococcal vaccination is not routinely practised, and awareness among physicians remains suboptimal.

In Nigeria, immunisation policies have traditionally focused on paediatric populations, particularly through the Expanded Programme on Immunisation (EPI), which includes pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) for infants. In contrast, adult immunisation lacks a structured framework within the national health policy. There are no routine schedules or government-supported programmes targeting adults for pneumococcal vaccination, leaving uptake largely dependent on individual initiative and opportunistic recommendations in clinical settings. This contrasts sharply with global practices in many high-income countries, where national immunisation plans include adult pneumococcal vaccination for the elderly and at-risk populations, often supported by insurance or public health funding. The absence of such policy direction in Nigeria contributes to missed opportunities for prevention and continued high disease burden in adults.

Pneumococcal pneumonia accounts for approximately 23–54% of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) cases in adults, with an associated in-hospital mortality rate of around 7.8%[6,7]. Evidence from various settings demonstrates that increased pneumococcal vaccine coverage correlates with a reduced disease burden [8,9]. In Northeast Nigeria, however, low adult vaccine uptake may contribute to the continued high burden of pneumococcal pneumonia in the region.

Invasive pneumococcal diseases (IPD), including bacteraemic pneumonia, pneumococcal meningitis, and sepsis, present significant public health challenges across Nigeria and Sub-Saharan Africa. In the region, Streptococcus pneumoniae is a major contributor to mortality, with estimated rates of 1.8 deaths per 100,000 from meningitis, 14.62 from pneumonia, and 3.06 from bloodstream infections [10]. The burden in Nigeria is particularly high, with 20.53 pneumonia-related deaths per 100,000 population, along with 2.65 deaths from bloodstream infections and 2.54 from meningitis[10]. Globally, pneumococcus is the leading cause of meningitis-related deaths across all age groups, with a similar pattern observed in the meningitis belt, where it accounts for 18.5% (95% CI: 17.2–19.8) of meningitis-related deaths [11]. In Northern Nigeria, S. pneumoniae has been identified in 5.3% of meningitis cases and 6.1% of bloodstream infections among adult patients with community-acquired bacterial infections [12]. The growing burden of pneumococcal disease is further exacerbated by rising antibiotic resistance. A national policy review on antimicrobial resistance, with data predominantly from Southern Nigeria, reported resistance rates of S. pneumoniae as follows: ceftriaxone (18.2%), erythromycin (29.8%), penicillin G (62.7%), cotrimoxazole (92.9%), and Augmentin (18.9%) [13]. In this context, preventive strategies such as vaccination are crucial to reducing both disease incidence and antibiotic misuse, which fuels resistance [14].

Despite the well-established benefits of pneumococcal vaccination in mitigating morbidity, mortality, and resistance, uptake and prescription remain exceedingly low in Northeast Nigeria. With no adult pneumococcal vaccines provided through national immunisation platforms, access depends heavily on clinicians’ recommendation during patient encounters. This makes physicians central to vaccine uptake. Their awareness, knowledge, and attitudes significantly influence whether vaccines are offered, discussed, or even considered during consultations. In a context where adult patients may not actively seek vaccination due to limited awareness or financial constraints, physicians’ proactive engagement becomes the most decisive factor in facilitating vaccine uptake. Therefore, gaps in physicians’ understanding or confidence regarding adult pneumococcal vaccination may represent a major barrier to progress.

This study, therefore, aims to assess the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of physicians in Northeastern Nigeria regarding adult pneumococcal vaccination, with a view to identifying challenges and providing evidence-based recommendations to enhance vaccine uptake and reduce the burden of pneumococcal disease.

Methods

Study Design

This study was a cross-sectional descriptive survey that evaluated the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of physicians in Northeastern Nigeria regarding adult pneumococcal vaccination.

Study Setting

The study participants were drawn from the healthcare facilities across Northeastern Nigeria, a region with a significant burden of pneumococcal disease and low adult vaccination coverage. The region is composed of six States, with a total population of 26 million people and represents 12% of Nigeria’s population [15]. The Northeastern Region is particularly vulnerable to pneumococcal infection due to its unique challenges, including a rising number of internally displaced persons due to ongoing insecurity and recurrent flooding [16]. These conditions are compounded by widespread ignorance and poverty, leading to heightened levels of malnutrition, as the region ranks low on socioeconomic disparity indices.

Study Population

The study population consisted of licensed physicians (including general practitioners, internists, infectious disease specialists, and pulmonologists) practising in hospitals within the region. Inclusion criteria include physicians actively working in primary, secondary or tertiary healthcare facilities in Northeast Nigeria and those who have consented to participate in the study. Physicians who were unavailable during the study period and those who declined to participate were excluded.

Sampling Technique

A purposive sampling technique was employed to select participants from hospitals with high patient turnover rates. This method ensured the inclusion of physicians with direct experience in managing adult patients at risk of pneumococcal disease.

Data Collection

A total of 73 respondents participated in the study, representing a convenience sample of physicians available during the study period from November 2024 to April 2025. Given the absence of prior KAP studies on pneumococcal vaccination among physicians in this region, this sample size provides a foundational assessment for future research.

A self-administered, semi-structured questionnaire comprising both closed- and open-ended questions was developed using Google Forms and distributed in electronic formats to physicians in selected hospitals and through social media platforms of professional bodies. The questionnaire was initially piloted and updated based on feedback received from respondents. Respondents were given adequate time to complete the survey anonymously.

Measurement of variables

The outcome variables for the study were knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding adult pneumococcal vaccination. Knowledge was evaluated through four questions assessing prior training, awareness of vaccine types, knowledge of recommended target groups, and familiarity with national/international guidelines. Attitude was assessed based on physicians’ perception of vaccine importance, confidence in recommending it, and views on its utilisation rate. Practice was evaluated through the frequency of vaccine prescription, likelihood of prescribing to specific groups, and preferred vaccine type.

Additional questions explored factors influencing prescription decisions, barriers to prescription, and suggestions for improving adult pneumococcal vaccination. Two open-ended questions were included to explore perceived challenges and respondents’ recommended strategies for improving uptake of adult pneumococcal vaccination. Our independent variables were age, sex, speciality and current practice setting of the respondents, and the duration that the participants were in practice.

Data Analysis

Data was extracted from the questionnaire and entered into Microsoft Excel, cleaned and exported to SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) version 26 for analysis. Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations) were used to summarise respondents’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices. The qualitative responses were analysed using a basic content analysis approach.The responses were read repeatedly, coded manually, and grouped into recurring themes.

Ethical Considerations

The study received ethical approval from the Gombe State Ministry of Health Research Ethics Committee (GMEHREC) with the reference number GMEHREC/SMOH/2025/021. All participants provided informed consent prior to participation, and confidentiality was maintained throughout the study in accordance with ethical standards.

Results

A total of 73 physicians responded to our questionnaire. The socio-demographic and professional characteristics are summarised in Table 1. The participants had a median age of 36 years (IQR: 32.0–39.0)., indicating a relatively young group of physicians. The majority were early to mid-career physicians within 1-5 years of practice (30; 41.1%) and 6-10 years (23; 31.5%). The highly experienced, 16-20 years and above 21 years of practice, represent the least number of respondents. There were more male (78.1%) respondents than female (21.9%).

The most common type of physician who responded to the survey were general practitioners (28; 38.3%), followed by internists (15; 20.6%). The majority of respondents practiced in tertiary healthcare settings (51; 69.9%), followed by those in secondary healthcare facilities (16; 21.9%).

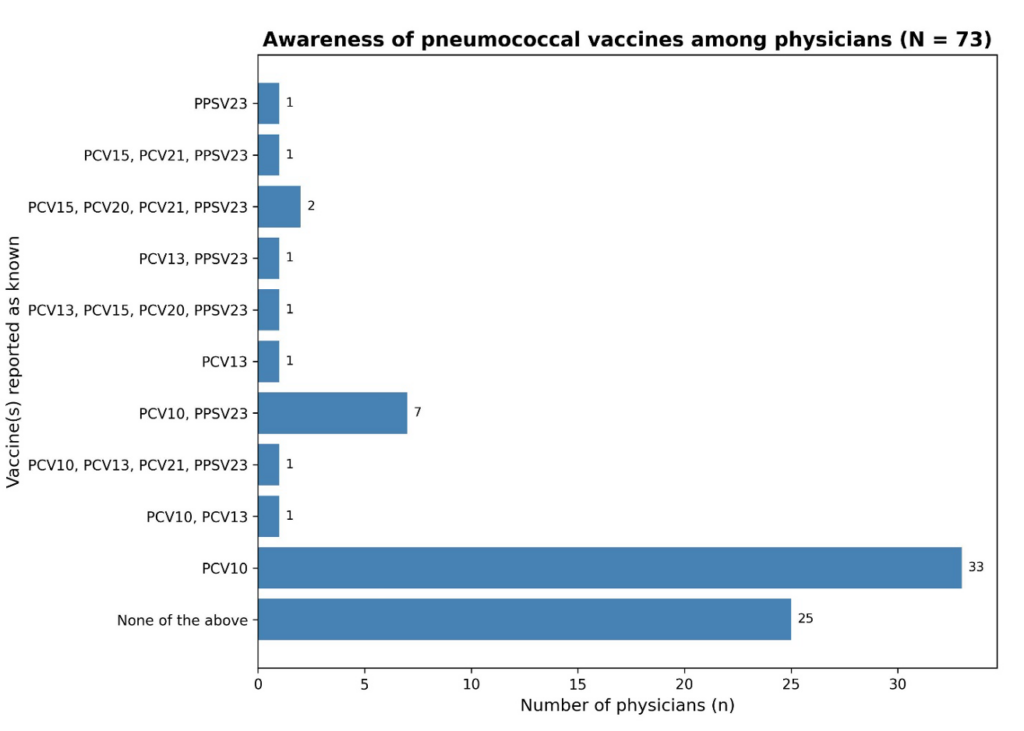

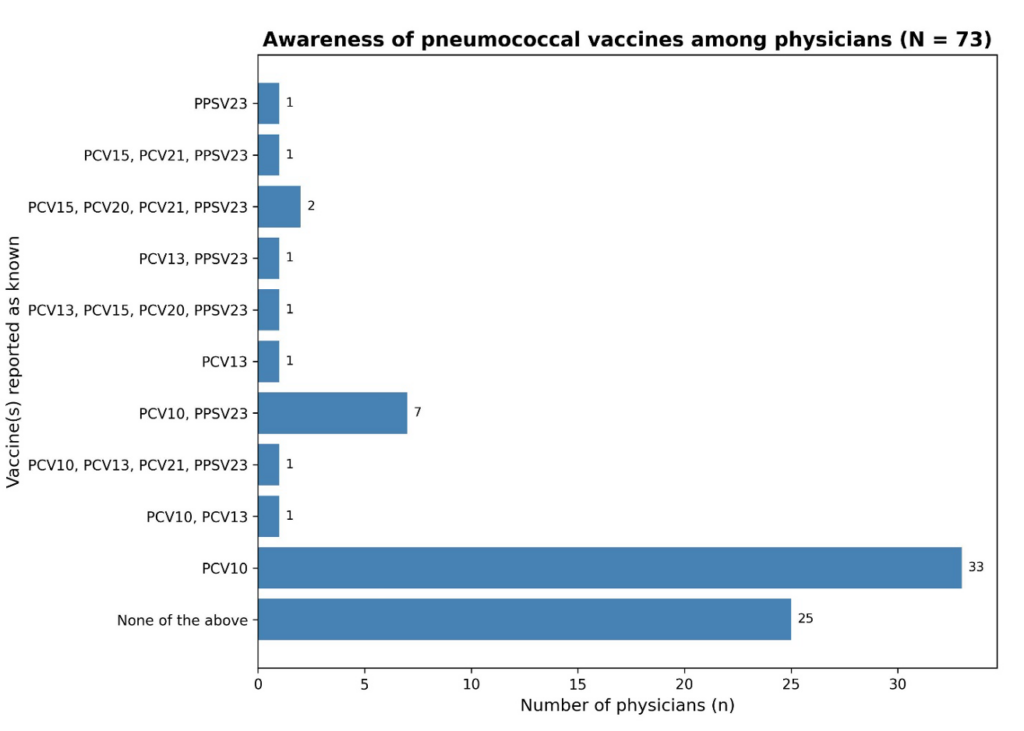

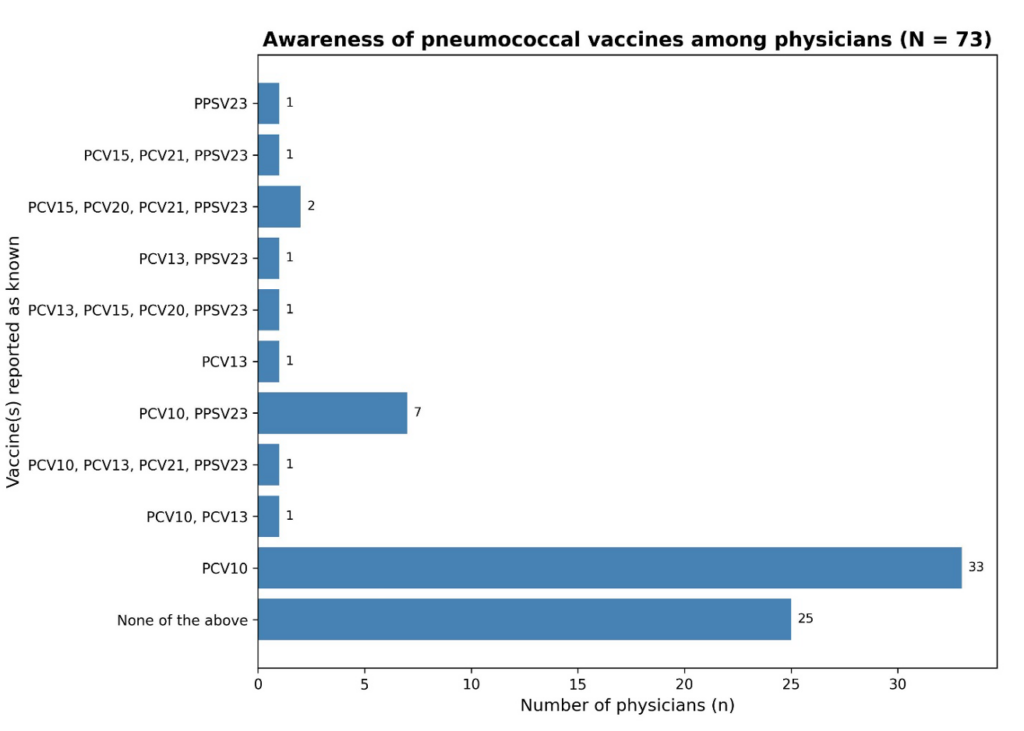

A large majority of participants, (69; 94.5%), reported having no formal training on adult pneumococcal vaccination. While 33 respondents (45.2%) were aware of PCV10, 25 participants (34.2%)—were not aware of any pneumococcal vaccine Figure 1.

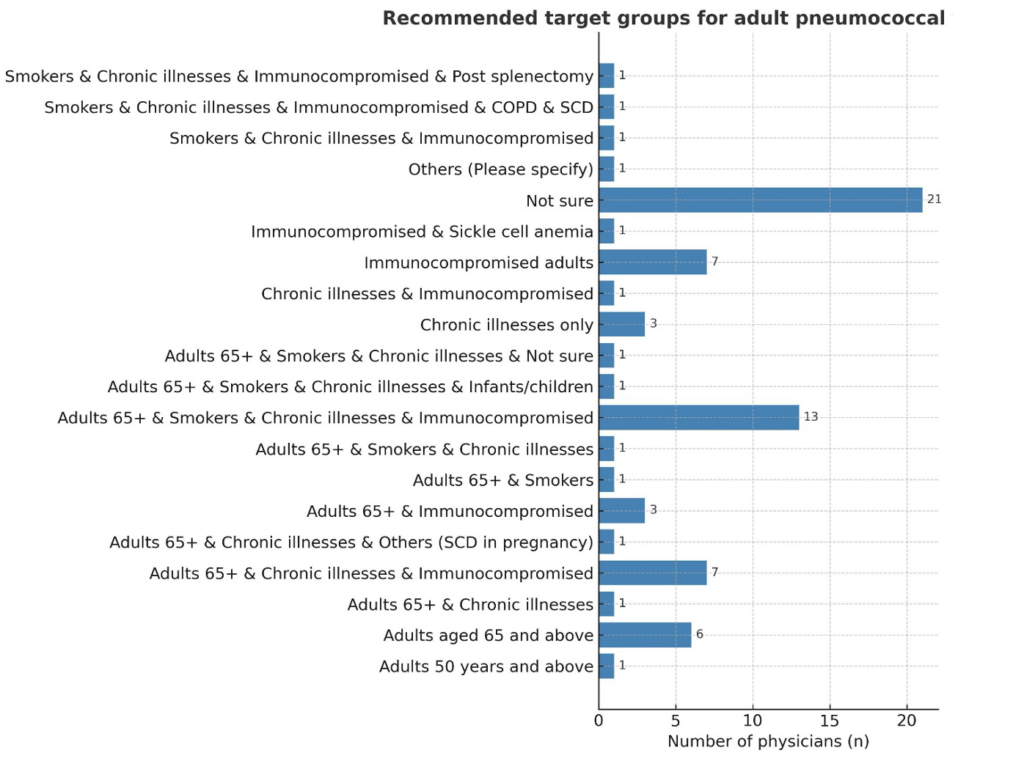

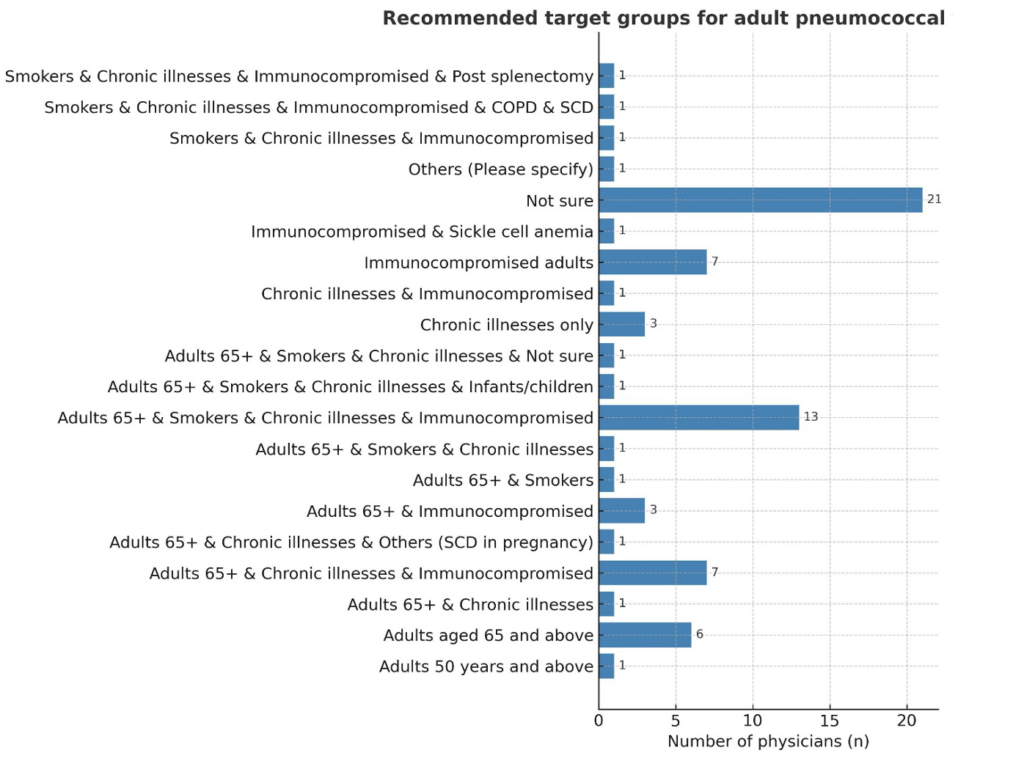

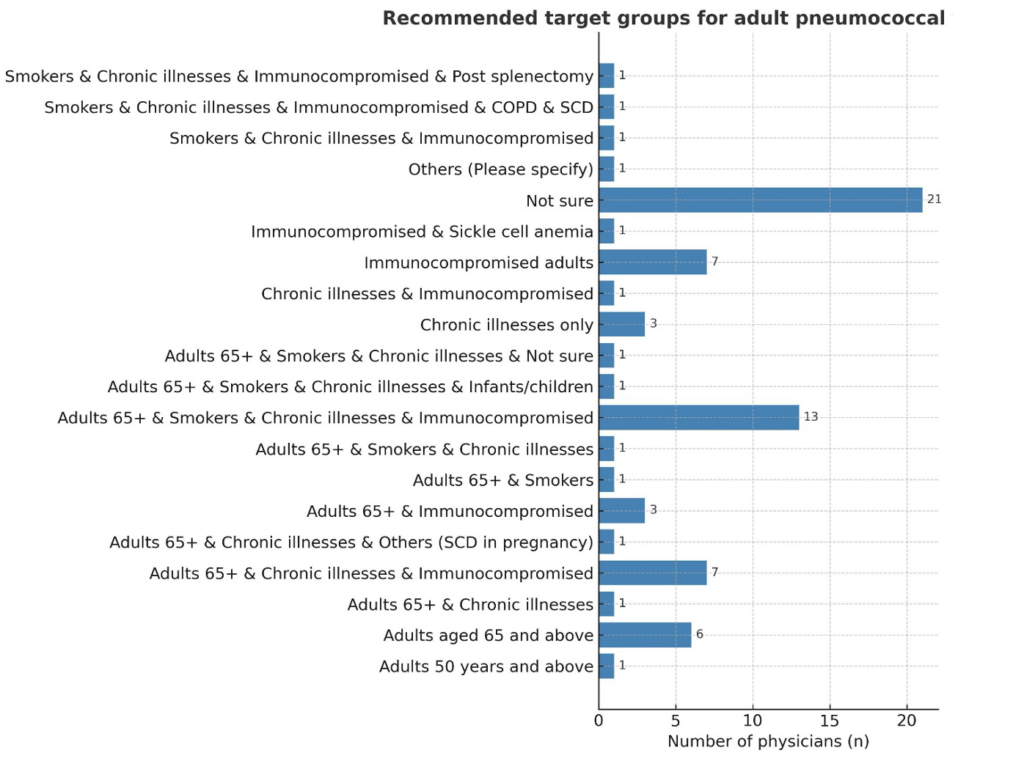

The knowledge of the recommended target groups for adult pneumococcal vaccination, such as adults aged ≥65 years, smokers, immunocompromised individuals, and those with chronic conditions, was limited. The most common response was “Not sure” (21; 28.8%). Only (7; 9.6%) correctly identified high-risk adult groups, while (13; 17.8%) included both appropriate and inappropriate groups (e.g., infants). Additionally, (52; 71.2%) of physicians were unaware of any national or international guidelines on adult pneumococcal vaccination, with only (11; 15.1%) indicating awareness.

The majority of physicians (58; 79.5%) rated adult pneumococcal vaccination as “very important” for pneumococcal disease prevention, while (15; 20.5%) considered it “somewhat important”; notably, none viewed it as unimportant. Regarding confidence in prescribing, (33; 45.2%) felt very confident, (31; 42.5%) moderately confident, and (9; 12.3%) were not confident. Most respondents (65, 89%) believed adult pneumococcal vaccination services are underutilised.

Physicians demonstrated a generally positive attitude toward recommending the vaccine, particularly to high-risk groups. For the elderly, 69.8% (51) were likely or very likely to recommend it, while19.2% (14) were unlikely or very unlikely. For immunocompromised individuals, 49.3% (36) were very likely and 26.1% (19) likely to recommend, with only9.6% (7) remaining neutral.

Among adults with chronic conditions, (53; 72.6%) were likely or very likely to recommend vaccination, while (10; 13.7%) remained neutral. For smokers, (28; 38.4%) were likely and (15; 20.5%) very likely to recommend, though (6; 8.2%) were very unlikely to do so. In contrast, for healthy adults, responses were more reserved: (21; 28.8%) were unlikely, and (17; 23.3%) either neutral or very unlikely, indicating hesitancy among physicians without clear risk factors.

In practice, (35; 47.9%) of physicians reported never recommending the vaccine, (23; 31.5%) rarely did so, and only one (1.4%) routinely prescribed it. Guideline-driven prescribing was low, with only (12; 16.4%) primarily guided by clinical recommendations. Seven (9.6%) cited a combination of factors, including age, comorbidities, and availability, while six (8.2%) relied solely on patient health status.

Notably, (35; 47.9%) do not recommend adult pneumococcal vaccines and (22; 30.1%) were unsure of the specific formulations available. Lack of awareness was the most commonly reported barrier (30; 41.1%), followed by vaccine unavailability (11; 15.1%) and a combination of both (9; 12.3%).

There was strong consensus on the lack of public health support: (62; 84.9%) believed there was insufficient public health information and support, while only four (5.5%) disagreed, and seven (9.6%) were unsure. The main barriers to recommendation included lack of awareness among physicians and patients (18; 24.7%), high vaccine cost, and cultural beliefs.

Association Between Sociodemographic Variables and Knowledge

Chi-square tests were used to explore the association between physicians’ knowledge of adult pneumococcal vaccination and key demographic/professional characteristics. The results showed no statistically significant association between knowledge and age (χ² = 18.663, p = 0.666), gender (χ² = 4.326, p = 0.115), years of medical practice (χ² = 5.104, p = 0.403), specialty (χ² = 15.683, p = 0.206), workplace setting (χ² = 1.667, p = 0.797), or perceived barriers to recommending the vaccine (χ² = 16.648, p = 0.409). These findings suggest that physicians’ knowledge of adult pneumococcal vaccination was generally uniform across different demographic and practice-related groups.

Association Between Sociodemographic Variables and Practice

In contrast to knowledge, physicians’ practices regarding vaccine recommendation showed statistically significant associations with all the examined variables. Specifically, significant associations were observed with age (χ² = 86.826, p < 0.001), gender (χ² = 84.340, p < 0.001), years of medical practice (χ² = 92.987, p < 0.001), specialty (χ² = 133.167, p < 0.001), workplace setting (χ² = 74.409, p < 0.001), and perceived barriers to vaccine recommendation (χ² = 230.130, p < 0.001). These results indicate that the practice of recommending pneumococcal vaccination to adults is influenced by multiple sociodemographic and professional factors, including perceived barriers.

Determinants of physicians’ knowledge and recommendation practices for adult pneumococcal vaccination

To identify independent predictors of physicians’ knowledge and vaccine recommendation practices, logistic regression analyses was conducted (Table 2). For knowledge, in the univariate analysis, none of the assessed variables—age, sex, years of practice, specialty, or workplace setting—showed a statistically significant association with physicians’ knowledge of adult pneumococcal vaccination. Although male physicians appeared less likely than females to have adequate knowledge (cOR = 0.39, 95% CI: 0.13–1.19, p = 0.098), this did not reach statistical significance. Similarly, general practitioners and those working in tertiary hospitals had lower odds of good knowledge compared to their counterparts, but these associations were not significant.

In the multivariate model, after adjusting for all predictors, the findings remained consistent. None of the demographic or professional characteristics independently predicted knowledge. The adjusted odds ratios (aORs) across variables were nonsignificant, indicating that physicians’ knowledge of adult pneumococcal vaccination was not systematically influenced by any single factor. Knowledge gaps regarding adult pneumococcal vaccination appear to cut across all demographic and professional groups. This suggests that educational interventions should be broadly targeted at all physicians rather than focused on specific subgroups.

For the practice of adult pneumococcal vaccination, in the univariate analysis, male physicians were significantly more likely than females to recommend adult pneumococcal vaccination (cOR = 4.45, 95% CI: 1.34–14.8, p = 0.015). No significant associations were observed for age, years of practice, specialty, or workplace setting. The multivariate analysis confirmed gender as an independent predictor of practice. After adjusting for all variables, male physicians had almost six times the odds of recommending pneumococcal vaccination more frequently than female physicians (aOR = 5.87, 95% CI: 1.50–23.1, p = 0.011). None of the other factors showed statistically significant effects. In contrast to knowledge, practice demonstrated a clear gender disparity, with male physicians substantially more likely to recommend pneumococcal vaccination to adults. This finding highlights potential gender-related influences such as professional confidence, exposure to vaccination initiatives, or social expectations that may shape recommendation behaviour.

Barriers to Adult Pneumococcal Vaccination and Suggested Strategies for Improvement

The survey also included two open-ended questions designed to explore the barriers and potential strategies for improving adult pneumococcal vaccination. A content analysis of the responses revealed several recurring themes. For the first question, which asked about the greatest challenges faced in recommending or administering pneumococcal vaccines to adults, the most frequently reported issue was a lack of awareness—both among healthcare providers and patients. Many respondents expressed unfamiliarity with the vaccine’s use in adults or reported that patients were unaware of its existence or importance. Unavailability of the vaccine was another significant barrier, with several participants noting that the vaccine was often not accessible in their facilities. Other commonly cited challenges included inadequate training or knowledge among healthcare workers, high cost of the vaccine, and cultural beliefs that hinder vaccine acceptance. A few respondents mentioned that they had never recommended the vaccine, mainly due to limited exposure or lack of awareness on their part.

In response to the second question, which sought suggestions to improve adult pneumococcal vaccination uptake, most respondents emphasised the need for increased public and professional awareness. Education campaigns targeting both healthcare providers and the general public were seen as vital to improving uptake. Many also recommended regular trainings and retraining of health workers to build confidence and competence in adult immunisation. Other suggestions included ensuring consistent vaccine availability, integrating the adult pneumococcal vaccine into the National Programme on Immunisation, subsidising its cost to improve affordability, and strengthening government support through policy and advocacy. Overall, the responses highlight the importance of awareness, training, accessibility, and policy integration in addressing the current gaps in adult pneumococcal vaccination uptake.

Discussion

This study assessed the responses of physicians in Northeastern Nigeria regarding adult pneumococcal vaccination. While there was an overwhelmingly positive perception of the importance of adult pneumococcal vaccines in preventing pneumococcal disease, the findings revealed substantial knowledge gaps, limited prescribing practices, and systemic barriers that may hinder vaccine uptake among adults in the region. The majority of respondents were early- to mid-career physicians practicing in secondary and tertiary healthcare settings. In Nigeria, due to gaps in the primary healthcare system, many adult patients—including the elderly and those with chronic comorbidities who form the bulk of the population eligible for adult pneumococcal vaccination—present directly to secondary or tertiary healthcare facilities, even for conditions typically managed at the primary care level. Although physicians in these settings may not routinely offer vaccinations, adult pneumococcal vaccination is not part of the National Programme on Immunisation and is not readily available even at the primary level. Therefore, physicians in higher-level facilities often act as primary care providers and are well-positioned to recommend vaccines, making their knowledge and attitudes crucial to improving adult pneumococcal vaccine uptake. Notably, a large proportion of respondents (94.5%) reported no formal training on adult pneumococcal vaccination, and many were unaware of available vaccine formulations or of national and international immunisation guidelines. These knowledge deficits were evident in the inability of most respondents to correctly identify the recommended high-risk adult groups for vaccination, with nearly a third selecting “not sure” in response.

The low awareness of adult pneumococcal vaccines observed in this study is consistent with previous research conducted in Lagos among patients with congestive cardiac failure, which found a pneumococcal vaccination rate of just 9%, with lack of information being the primary barrier to uptake [17]. This local pattern reflects a broader global issue. A systematic review identified inadequate training and awareness among healthcare providers as key contributors to the underutilisation of adult pneumococcal vaccines [18]. Similarly, an overview of South African adult pneumococcal vaccination guidelines noted significant knowledge gaps among healthcare workers, highlighting the need to integrate adult vaccination more effectively within existing healthcare frameworks [19].

Despite these knowledge limitations, physician attitudes were encouragingly positive. A majority (79.5%) rated adult pneumococcal vaccination as “very important.” Respondents showed the strongest willingness to recommend vaccination to elderly adults, immunocompromised individuals, and patients with chronic conditions. However, hesitancy was observed when considering groups like smokers, suggesting that uncertainty persists in the absence of structured risk stratification or clear clinical protocols.

In practice, a notable gap exists between attitude and action. Nearly half (47.9%) of the physicians reported never recommending the vaccine, while only one respondent prescribed it routinely. This discrepancy is further underscored by the fact that many were unsure of the specific pneumococcal formulations available or lacked the confidence to prescribe them. This finding contrasts with data from the United States, where over 95% of physicians routinely assess patients for pneumococcal vaccine eligibility and recommend vaccination when appropriate. This high level of engagement has been attributed to improved provider training and the availability of clearly articulated guidelines, with 50% of the participants describing the recommendations as “very clear” and 38% as “somewhat clear”) [20]. Furthermore, a global review of vaccine effectiveness concluded that healthcare providers are more likely to recommend adult vaccines when they are confident in their knowledge and have access to clear, evidence-based guidelines [21].

Barriers identified in this study—predominantly lack of awareness, unavailability of vaccines, and insufficient public health support—are aligned with challenges documented in similar low- and middle-income countries [22]. The perception of inadequate public health infrastructure was particularly strong in this study, with 84.9% of respondents citing a lack of public health engagement or information. In addition to knowledge gaps among physicians, respondents noted that patient unawareness, high costs, and cultural beliefs further limited vaccine uptake.

Importantly, participants proposed practical solutions to address these challenges. Recommendations included enhancing provider training through continuing medical education (CME), increasing public and patient awareness campaigns, offering vaccine subsidies to improve affordability, and formally integrating adult pneumococcal vaccination into the national immunisation schedule. These proposed interventions align with global best practices and support a comprehensive, multi-level strategy for improving adult vaccine uptake. These findings have direct policy relevance. They support the inclusion of adult pneumococcal vaccination in Nigeria’s immunisation strategies, particularly for high-risk groups. The gaps also identified highlight the need for structured training programs on adult immunisation as part of continuing medical education. Strengthening provider knowledge and formally integrating adult vaccines into routine care can enhance vaccine uptake and improve adult health outcomes.

A major strength of this study is that it is the first in the region to assess physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding adult pneumococcal vaccination. As such, it provides a valuable foundation for future research and offers insights to inform targeted training and capacity-building efforts. However, the relatively small sample size (n=73) and convenience sample may limit the generalisability of the findings, and the reliance on self-reported data introduces the potential for recall bias.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study highlights significant missed opportunities in the prevention of adult pneumococcal disease in Nigeria. Addressing these gaps requires a coordinated effort involving policymakers, healthcare institutions, and frontline providers. Strengthening physician education, ensuring vaccine availability, and integrating adult pneumococcal vaccination into existing health systems are critical steps toward improving coverage and ultimately reducing disease burden in Nigeria and other resource-limited settings.

What is already known about the topic

Adult pneumococcal vaccination is a key strategy in preventing severe pneumococcal infections, particularly among high-risk groups such as the elderly and those with chronic illnesses.

Studies have demonstrated that healthcare providers’ knowledge and recommendations play a critical role in vaccine uptake.

In Nigeria, adult pneumococcal vaccination uptake is low, with few studies assessing healthcare providers’ knowledge and practices, particularly in the northeastern region.

What this study adds

This is the first study to assess the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of physicians regarding adult pneumococcal vaccination in Northeastern Nigeria.

While physicians showed overwhelmingly positive attitudes toward the importance of adult pneumococcal vaccination, substantial gaps in knowledge, limited prescribing behaviour, and systemic barriers were identified.

The study highlights missed opportunities for prevention due to a lack of provider training.

It provides actionable recommendations, including the need for continuous medical education, clearer clinical protocols, and policy support to improve adult pneumococcal vaccine uptake in low-resource settings.

Authors´ contributions

IA conceived the original idea, developed the research concept and framework, designed the questionnaire, conducted data analysis and interpretation, and contributed to both the initial and final drafts of the manuscript.

IA, AAB, KI, UMH, and DIS were involved in data collection.

UMH also contributed to questionnaire development.

AAB, KI, UMH, DIS, and AA reviewed and provided critical revisions to the final draft.

AA further contributed to the discussion section and final manuscript refinement.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 20–29 | 14 | 19.2 |

| 30–39 | 44 | 60.3 |

| 40–49 | 13 | 17.8 |

| 50–59 | 2 | 2.7 |

| ≥60 | 0 | 0 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 16 | 21.9 |

| Female | 57 | 78.1 |

| Years of medical practice (Years) | ||

| 1–5 | 30 | 41.1 |

| 6–10 | 23 | 31.5 |

| 11–15 | 15 | 15 |

| 16–20 | 3 | 4.1 |

| >21 | 2 | 2.7 |

| Specialty | ||

| General Practice | 28 | 38.3 |

| Internal Medicine | 15 | 20.6 |

| Infectious Diseases | 2 | 2.7 |

| Pulmonology | 4 | 5.5 |

| Others | 24 | 32.9 |

| Current practice setting | ||

| Primary healthcare setting | 3 | 4.1 |

| Secondary healthcare setting | 16 | 21.9 |

| Tertiary healthcare setting | 51 | 69.9 |

| Private healthcare setting | 3 | 4.1 |

| Variables | Knowledge | Practice | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cOR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Age (years) | 1.06 (0.97–1.16) | 0.207 | 1.09 (0.96–1.23) | 1.02 (0.94–1.11) | 0.603 | 1.05 (0.94–1.18) |

| Male vs Female | 0.39 (0.13–1.19) | 0.098 | 0.33 (0.10–1.12) | 4.45 (1.34–14.8) | 0.015 | 5.87 (1.50–23.1) |

| >10 yrs vs ≤10 yrs of practice | 0.66 (0.16–2.73) | 0.566 | 0.97 (0.18–5.28) | 0.87 (0.24–3.14) | 0.834 | 0.97 (0.21–4.43) |

| General practice vs Other | 0.35 (0.09–1.42) | 0.141 | 0.23 (0.04–1.20) | 1.92 (0.58–6.40) | 0.285 | 2.93 (0.81–10.6) |

| Tertiary vs Primary/Secondary setting | 0.47 (0.10–2.18) | 0.335 | 0.33 (0.06–1.86) | 2.08 (0.60–7.25) | 0.245 | 2.95 (0.73–11.3) |

References

- Subramanian K, Henriques‐Normark B, Normark S. Emerging concepts in the pathogenesis of the Streptococcus pneumoniae: From nasopharyngeal colonizer to intracellular pathogen. Cell Microbiol [Internet]. 2019 Jun 28 [cited 2025 Aug 26];21(11):e13077. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cmi.13077 doi: 10.1111/cmi.13077

- Feldman C, Anderson R. Recent advances in the epidemiology and prevention of Streptococcus pneumoniae infections. F1000Res [Internet]. 2020 May 7 [cited 2025 Aug 26];9(F1000 Faculty Rev):338. Available from: https://f1000research.com/articles/9-338/v1 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.22341.1

- Butler JC, Schuchat A. Epidemiology of pneumococcal infections in the elderly. Drugs Aging [Internet]. 2012 Aug 31 [cited 2025 Aug 26];15(1999):11–9. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.2165/00002512-199915001-00002 doi: 10.2165/00002512-199915001-00002

- Drijkoningen JJC, Rohde GGU. Pneumococcal infection in adults: burden of disease. Clin Microbiol Infect [Internet]. 2013 Dec 6 [cited 2025 Aug 26];20(Suppl 5):45–51. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1198743X14601750 doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12461

- Fung HB, Monteagudo-Chu MO. Community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother [Internet]. 2010 Mar 10 [cited 2025 Aug 26];8(1):47–62. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1543594610000048 doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2010.01.003

- Iliyasu G, Mohammad FD, Habib AG. Community acquired pneumococcal pneumonia in Northwestern Nigeria: epidemiology, antimicrobial resistance and outcome. Afr J Infect Dis [Internet]. 2017 Nov 15 [cited 2025 Aug 26];12(1):15–9. Available from: https://journals.athmsi.org/index.php/AJID/article/view/3962 doi: 10.21010/ajid.v12i1.3

- Oluwatoyin G. Microbial aetiology and risk factors of community-acquired pneumonia in security-challenged communities in the northeast Nigeria. J Infect Dis Microbiol [Internet]. 2020 Sep 30 [cited 2025 Aug 26]; Available from: https://maplespub.com/article/microbial-aetiology-and-risk-factors-of-community-acquired-pneumonia-in-security-challenged-communities-in-the-northeast-nigeria doi: 10.37191/Mapsci-JIDM-1(1)-002

- Simonsen L, Taylor RJ, Young-Xu Y, Haber M, May L, Klugman KP. Impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination of infants on pneumonia and influenza hospitalization and mortality in all age groups in the United States. mBio [Internet]. 2011 Jan 25 [cited 2025 Aug 26];2(1):e00309-10. Available from: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/mBio.00309-10 doi: 10.1128/mbio.00309-10

- Griffin MR, Zhu Y, Moore MR, Whitney CG, Grijalva CG. U.S. Hospitalizations for pneumonia after a decade of pneumococcal vaccination. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2013 Jul 11 [cited 2025 Aug 26];369(2):155–63. Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1209165 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209165

- IHME, University of Oxford. MICROBE: Measuring Infectious Causes and Resistance Outcomes for Burden Estimation [Internet]. Oxford (England): University of Oxford; 2022 Dec 7 [cited 2025 Aug 26]. Available from: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/microbe/

- Wunrow HY, Bender RG, Vongpradith A, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of meningitis and its aetiologies, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol [Internet]. 2023 Aug [cited 2025 Aug 26];22(8):685–711. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1474442223001953 doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(23)00195-3

- Iliyasu G, Habib A, Aminu M. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of invasive pneumococcal isolates in North West Nigeria. J Global Infect Dis [Internet]. 2015 Apr-Jun [cited 2025 Aug 26];7(2):70–4. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/10.4103/0974-777X.154440 doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.154440

- Federal Ministries of Agriculture, Environment and Health. Antimicrobial use and resistance in Nigeria: situation analysis and recommendations [Internet]. Abuja (Nigeria): Federal Ministries of Agriculture, Environment and Health; 2017 Sep [cited 2025 Aug 26];156 p. Available from: https://ncdc.gov.ng/themes/common/docs/protocols/56_1510840387.pdf

- Lawrence H, Pick H, Baskaran V, et al. Effectiveness of the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine against vaccine serotype pneumococcal pneumonia in adults: A case-control test-negative design study. PLoS Med [Internet]. 2020 Oct 23 [cited 2025 Aug 26];17(10):e1003326. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003326 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003326

- National Population Commission. Nigeria Population projections and demographic indicators [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Aug 25]. Available from: https://nationalpopulation.gov.ng/publications

- Mba R. The plight of internally displaced persons (IDPS) and the need for reinterration [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): Medium; 2017 Dec 13 [cited 2025 Aug 26]. Available from: https://medium.com/@RuthMba1/the-plight-of-internally-displaced-persons-idps-and-the-need-for-reinterration-b7555c212f37

- Ajibare AO, Ojo OT, Odeyemi AS, et al. Pneumococcal vaccine uptake and its associated factors among adult patients with congestive cardiac failure seen in a tertiary facility in Lagos, Nigeria. Ibom Med J [Internet]. 2023 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Aug 26];16(1):14–21. Available from: https://ibommedicaljournal.org/index.php/imjhome/article/view/286 doi: 10.61386/imj.v16i1.286

- Cafiero-Fonseca ET, Stawasz A, Johnson ST, et al. The full benefits of adult pneumococcal vaccination: A systematic review. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2017 Oct 31 [cited 2025 Aug 26];12(10):e0186903. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186903 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186903

- Feldman C, Dlamini S, Richards GA, et al. A comprehensive overview of pneumococcal vaccination recommendations for adults in South Africa, 2022. J Thorac Dis [Internet]. 2022 Jul 28 [cited 2025 Aug 26];14(10):4150–72. Available from: https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/68210/html doi: 10.21037/jtd-22-287

- Hurley LP, Allison MA, Pilishvili T, et al. Primary care physicians’ struggle with current adult pneumococcal vaccine recommendations. J Am Board Fam Med [Internet]. 2018 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Aug 26];31(1):94–104. Available from: http://www.jabfm.org/lookup/doi/10.3122/jabfm.2018.01.170216 doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2018.01.170216

- Heo JY, Seo YB, Choi WS, et al. Effectiveness of pneumococcal vaccination against pneumococcal pneumonia hospitalization in older adults: a prospective, test-negative study. J Infect Dis [Internet]. 2022 Mar 2 [cited 2025 Aug 26];225(5):836–45. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/225/5/836/6372439 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab474

- Huang J, Mak FY, Wong YY, et al. Enabling factors, barriers, and perceptions of pneumococcal vaccination strategy implementation: a qualitative study. Vaccines [Internet]. 2022 Jul 21 [cited 2025 Aug 26];10(7):1164. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/10/7/1164 doi: 10.3390/vaccines10071164