Research | Open Access | Volume 8 (4): Article 95 | Published: 20 Nov 2025

Prevalence and associated factors for femoral shaft fractures among motor traffic accident victims in southern Tanzania

Menu, Tables and Figures

Navigate this article

Tables

| Characteristic | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Study site | ||

| Ligula Regional Referral Hospital | 19 | 12.3 |

| Sokoine Regional Referral Hospital | 34 | 22.1 |

| Southern Zone Referral Hospital | 4 | 2.6 |

| St. Benedict’s Ndanda Hospital | 54 | 35.1 |

| St. Walburg’s Nyangao Hospital | 43 | 27.9 |

| Age (years) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 31.5 (22–49) | |

| ≤17 | 29 | 18.8 |

| 18–34 | 57 | 37.0 |

| 35–50 | 36 | 23.4 |

| 51–64 | 14 | 9.1 |

| ≥65 | 18 | 11.7 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 37 | 24.0 |

| Male | 117 | 76.0 |

| Religion status | ||

| Christian | 32 | 20.8 |

| Muslim | 122 | 79.2 |

| Occupation status | ||

| Employed | 17 | 11.0 |

| Self-employed | 97 | 63.0 |

| Student | 30 | 19.5 |

| Unemployed | 10 | 6.5 |

| Marital status | ||

| Divorced | 2 | 1.3 |

| Married | 88 | 57.1 |

| Single | 64 | 41.6 |

| Education | ||

| Degree | 8 | 5.2 |

| Diploma | 8 | 5.2 |

| Certificate | 2 | 1.3 |

| Secondary | 43 | 27.9 |

| Primary | 86 | 55.8 |

| No school | 7 | 4.6 |

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of the MTA victims in Southern Tanzania from January to December 2023 (N=154)

| Injury characteristic | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Fracture type | ||

| Closed | 90 | 84.9 |

| Open | 16 | 15.1 |

| Fracture anatomical site | ||

| Proximal | 32 | 30.2 |

| Mid-shaft | 58 | 54.7 |

| Distal | 16 | 15.1 |

| Side of Femur fracture | ||

| Left | 57 | 53.8 |

| Right | 49 | 46.2 |

| Isolated Femur fracture | ||

| No | 20 | 18.9 |

| Yes | 86 | 81.1 |

| Pattern of femur fracture | ||

| Transverse | 58 | 54.7 |

| Oblique | 36 | 34.0 |

| Spiral | 3 | 2.8 |

| Comminuted | 9 | 8.5 |

Table 2. Distribution of Femur fracture characteristics of the MTA victims in Southern Tanzania from January to December 2023 (N=106)

| Type of associated injury | Female (N=37) n (%) | Male (N=117) n (%) | Total (N=154) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head injury | 10 (27.0) | 34 (29.1) | 44 (28.6) |

| Musculoskeletal injury | 13 (35.1) | 27 (23.1) | 40 (26.0) |

| Tibia fracture | 10 (27.0) | 12 (10.3) | 22 (14.3) |

| Chest injury | 2 (5.4) | 9 (7.7) | 11 (7.1) |

| Visceral injury | 1 (2.7) | 8 (6.8) | 9 (5.8) |

| Radius fracture | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.4) | 4 (2.6) |

| Left upper limb fracture | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.7) |

| No associated injuries | 1 (2.7) | 22 (18.8) | 23 (14.9) |

Table 3: Distribution of the studied MTA victims by the type of associated injuries according to their Sex in Southern Tanzania, from January to December 2023 (N=154)

| Variable | FSFs status | Bivariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | PR (95% CI) | p-value | aPOR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age (in years) | ||||||

| ≤17 | 25 (86.2) | 4 (13.8) | 0.80 (0.16-4.08) | 0.788 | 1.68 (0.17-16.25) | 0.656 |

| 18–34 | 26 (45.6) | 31 (54.4) | 5.96 (1.55-22.87) | 0.009 | 5.92 (1.39-25.18) | 0.016* |

| 35–50 | 21 (58.3) | 15 (41.7) | 3.57 (0.88-14.56) | 0.076 | 3.58 (0.80-15.95) | 0.094 |

| 51–64 | 9 (64.3) | 5 (35.7) | 2.78 (0.53-14.50) | 0.226 | 2.47 (0.42-14.43) | 0.317 |

| ≥65 | 15 (83.3) | 3 (16.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 31 (83.8) | 6 (16.2) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Male | 65 (55.6) | 52 (44.4) | 4.13 (1.60-10.66) | 0.003 | 3.34 (1.20-9.33) | 0.021* |

| Occupation status | ||||||

| Employed | 9 (52.9) | 8 (47.1) | 1.33 (0.27-6.50) | 0.722 | 1.05 (0.17-6.43) | 0.955 |

| Self-employed | 56 (57.7) | 41 (42.3) | 1.10 (0.29-4.14) | 0.890 | 1.18 (0.25-5.51) | 0.837 |

| Unemployed | 6 (60.0) | 4 (40.0) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 53 (60.2) | 35 (39.8) | 1 | |||

| Divorced | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 1.51 (0.09-25.01) | 0.772 | ||

| Single | 42 (65.6) | 22 (34.4) | 0.79 (0.41-1.55) | 0.498 | ||

| Education status | ||||||

| Degree | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | 0.75 (0.10-5.77) | 0.782 | ||

| Secondary | 27 (62.8) | 16 (37.2) | 0.44 (0.09-2.24) | 0.326 | ||

| No school | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) | 1 | |||

| Victim Category | ||||||

| Driver | 24 (49.0) | 25 (51.0) | 1.74 (0.74-4.06) | 0.204 | ||

| Passenger | 47 (72.3) | 18 (27.7) | 0.64 (0.28-1.48) | 0.295 | ||

| Pedestrian | 25 (62.5) | 15 (37.5) | 1 | |||

| Season of the year | ||||||

| Rainy season | 40 (75.5) | 13 (24.5) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Dry season | 50 (54.4) | 42 (45.6) | 2.58 (1.22-5.46) | 0.013 | 3.11 (1.33-7.30) | 0.009* |

| Cold season | 6 (66.7) | 3 (33.3) | 1.54 (0.34-7.04) | 0.579 | 1.64 (0.30-9.08) | 0.569 |

*p-values of the variables significantly associated with FSFs among the MTA victims in Southern Tanzania.

Table 4. Factors associated with FSFs among MTA victims in Southern Tanzania from January to December 2023 (N=154)

Figures

Keywords

- Femoral Shaft Fractures

- Motor Traffic Accidents

- Femur Fracture

- Prevalence

- Southern Tanzania

Vulstan James Shedura1,&, Geofrey John Ngomo2, Lameck Titus Moses2, Herbert George Masigati3

1Department of Clinical Research, Training, and Consultancy, Southern Zone Referral Hospital, Mtwara, Tanzania, 2Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Southern Zone Referral Hospital, Mtwara, Tanzania, 3Department of General Surgery, Southern Zone Referral Hospital, Mtwara, Tanzania

&Corresponding author: Vulstan James Shedura, Department of Clinical Research, Training, and Consultancy, Southern Zone Referral Hospital, P.O. Box 272, Mtwara, Tanzania, Email: vulstanshedura@gmail.com ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1939-2492

Received: 04 Jan 2025, Accepted: 19 Nov 2025, Published: 20 Nov 2025

Domain: Injury Epidemiology

Keywords: Femoral Shaft Fractures, Motor Traffic Accidents, Femur Fracture, Prevalence, Southern Tanzania

©Vulstan James Shedura et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Vulstan James Shedura et al., Prevalence and associated factors for femoral shaft fractures among motor traffic accident victims in southern Tanzania. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8(4):95. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00009

Abstract

Introduction: Femoral shaft fractures are a significant health issue in low- and middle-income countries, especially among victims of motor traffic accidents. The World Health Organization reported 1.2 million deaths from motor vehicle collisions in 2018. This study aimed to determine FSF prevalence and associated factors in Southern Tanzania to guide interventions.

Methods: A retrospective, health facility-based cross-sectional study was used to analyze data from 01/01/23 to 31/12/23, including 154 patients admitted to five referral hospitals in Southern Tanzania following motor traffic accidents.

Results: The median age was 31.5 years (IQR: 22–49), with 76% (117/154) being male and 57.1% (88/154) married. Most participants were self-employed (63.0%, 97/154), 37.0% (57/154) were young adults (18–34 years), and 55.8% (86/154) had primary education. The prevalence of femoral shaft fractures was 37.7% (58/154), with the majority of them, 93.1% (54/58), being closed fractures. Head injuries were the most common associated injury (28.6%, 44/154). In addition, being a young adult (aged 18-34 years old) (aPOR=5.92, 95% CI: 1.39-25.18, p=0.016), Male (aPOR=3.34, 95% CI: 1.20-9.33, p=0.021), and at the dry season of the year (aPOR=3.11, 95% CI: 1.33-7.30, p=0.009), were factors independently associated with Femoral Shaft Fractures among Motor Traffic Accidents Victims in Southern Tanzania.

Conclusion: There is a notably high prevalence of femoral shaft fractures in Southern Tanzania, which disproportionately affects young adult males. These fractures complicate trauma management and highlight the need for prompt interventions. Factors associated with Femoral Shaft fractures include age, gender, and seasonal variations. Comprehensive trauma care systems and preventive measures are crucial to reduce the burden of femoral shaft fractures in Southern Tanzania and beyond.

Introduction

Femoral shaft fractures (FSFs) are among the most severe musculoskeletal (MSK) injuries and are a significant cause of mortality and disability, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)[1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported in 2018 that motor traffic injuries caused approximately 1.2 million deaths globally, with Motor traffic accidents (MTA) ranking as the ninth leading cause of morbidity and the tenth leading cause of mortality worldwide[1].

Globally, the annual incidence of FSFs from MTA is estimated to be between 1.0 and 2.9 million, with LMICs experiencing significantly higher rates compared to high-income countries (HICs). FSFs disproportionately affect young individuals, emphasizing the need for improved access to treatment [2]. Injuries, including FSFs, account for approximately 9% of global deaths and have profound social and economic impacts on affected individuals and their families. FSFs require intensive inpatient care, further straining healthcare resources in LMICs [3, 4]. MTA also contributes significantly to hospital admissions, with LMICs bearing 90% of global road traffic mortality and disability, with the incidence ranging between 15.7 and 45.5 per 100,000 people per year in LMICs. FSFs are a major consequence of MTA, with an estimated 20–50 million people globally disabled due to MSK injuries annually, of which FSFs are among the most common [1, 2].

Studies from various parts of Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) highlight the common mechanisms and demographics associated with FSFs. Motor vehicle collisions are the leading cause of FSFs in older children and adolescents, whereas falls are the primary cause in younger children[5]. In SSA, males are disproportionately affected, often sustaining FSFs as a result of high-energy trauma[6]. Studies have identified risk factors, such as alcohol consumption, smoking, and non-compliance with road safety measures, stressing the need for proper interventions to reduce the prevalence of FSFs [7]. FSFs often result from high-energy trauma caused by MTA, which leads to significant suffering, including disability and associated injuries such as traumatic brain injuries. Blood loss in FSFs can be substantial, with reports of 2–3 units lost per patient, which may lead to irreversible shock and death[8, 9]. LMICs, for instance, in SSA, face unique challenges, such as inadequate financial resources and a focus on prevention rather than treatment, resulting in higher rates of mortality and disability among FSFs patients. A previous study in SSA reported that one person dies and four are injured every hour due to MTA, with over 65% of these incidents attributed to speeding, non-compliance with traffic signals, and alcohol use[8, 9].

In East Africa, particularly in Kenya and Tanzania, FSFs resulting from injuries such as MTA pose a significant public health and economic challenge[1,9]. MTA contributes substantially to injury-related morbidity, with national data from Kenya indicating that approximately 15% of adults experienced injuries in 2018, 4% of which were due to MTA [7,9]. The majority of the injured were males (60.3%), and predictors included youth, smoking, and heavy drinking[7]. In LMICs, like Kenya and Tanzania, the lack of surgical resources and implants often results in non-surgical management of FSFs, leading to prolonged hospital stays and increased mortality rates. Even where surgical options exist, the high costs are prohibitive for many patients, compounding the burden of disability and death[10]. Studies have shown that young adult males are the most affected demographic, frequently presenting with associated injuries such as head trauma, lower limb fractures, and upper limb fractures [9].

In Tanzania, FSFs are a common presentation in orthopaedic departments, with an annual incidence ranging between 2.1 and 18.4 per 100,000 people[6, 7]. The increasing number of MTA, particularly involving motorcycles, has significantly contributed to the rising prevalence of FSFs, especially among males aged 21–30 years[6]. Associated injuries, such as traumatic brain injuries, further compound the clinical burden. In northern Tanzania, FSFs have been reported to account for 28.6% of orthopaedic cases, with the majority resulting from MTA[11]. Despite this concerning trend, data on the magnitude and contributing factors of FSFs in the Southern part of Tanzania are limited.

FSFs represent a significant public health challenge in Tanzania, with substantial socio-economic implications[1, 11, 12]. We aimed to provide a comprehensive understanding of the prevalence and associated factors of FSFs among MTA Victims in Southern Tanzania, contributing to the development of effective interventions, including funding for implants, improving access to surgical care, and strengthening road safety measures to mitigate the burden of these injuries.

Methods

Study design

It is a cross-sectional analytical study conducted between March to April 2024 by reviewing the surveillance data of MTA from January 2023 to December 2023 from the selected referral hospitals in southern Tanzania.

Study area

This study was conducted in southern Tanzania, comprising the Lindi, Mtwara, and Ruvuma regions, which together cover an area of 146,419 square kilometres [13]. The southern zone is situated between longitudes 34°32’E and 40°26’E and latitudes 7°56’S and 11°44’S. It is bordered by the Ruvuma River and Mozambique to the south, the Ruvuma region to the west, and the Lindi region to the north[13]. Most roads in southern Tanzania are paved with tarmac in urban areas, while rural areas predominantly have unpaved, dusty roads that lack tarmac and proper traffic signage. The coastal trunk road links Mtwara, Lindi, Kilwa, and Dar es Salaam, while another major road connects Songea, Njombe, and Makambako to the Tanzania-Zambia Highway. The study was conducted in five hospitals located in the Mtwara and Lindi regions located in part of Tanzania. These hospitals provide tertiary-level services in orthopedics and trauma care. The selected hospitals included the Southern Zone Referral Hospital, Ligula Regional Referral Hospital (RRH), St. Benedict’s Ndanda Council Designated Hospital (CDH), Lindi RRH, and St. Walburg’s Nyangao CDH. These facilities were purposively selected due to their accessibility and because they handle a high volume of patients with MTA-related injuries, including FSFs, compared to other hospitals in southern Tanzania.

Study Population

The study population comprised all MTA victims (of any age) who attended the Southern Zone Referral Hospital, Ligula Regional Referral Hospital (RRH), St. Benedict’s Ndanda Council Designated Hospital (CDH), Lindi RRH, and St. Walburg’s Nyangao CDH in southern Tanzania, from January 2023 to December 2023.

Inclusion criteria: All records of MTA victims who sought care at the selected study hospitals.

Exclusion criteria: Records of MTA victims with incomplete or missing information were excluded from the analysis.

Sample size estimation and Sampling method

Sample size estimation

We calculated the sample size using the Kish and Leslie formula based on the data from a prevalence study conducted in Tanzania, with a prevalence rate of 10.0% for femoral shaft fractures [1]. We used a two-sided 95% confidence interval, a marginal error of 5%, and considered a 10% non-response rate. The resulting sample size was 154.

The sample size distribution per selected Hospital

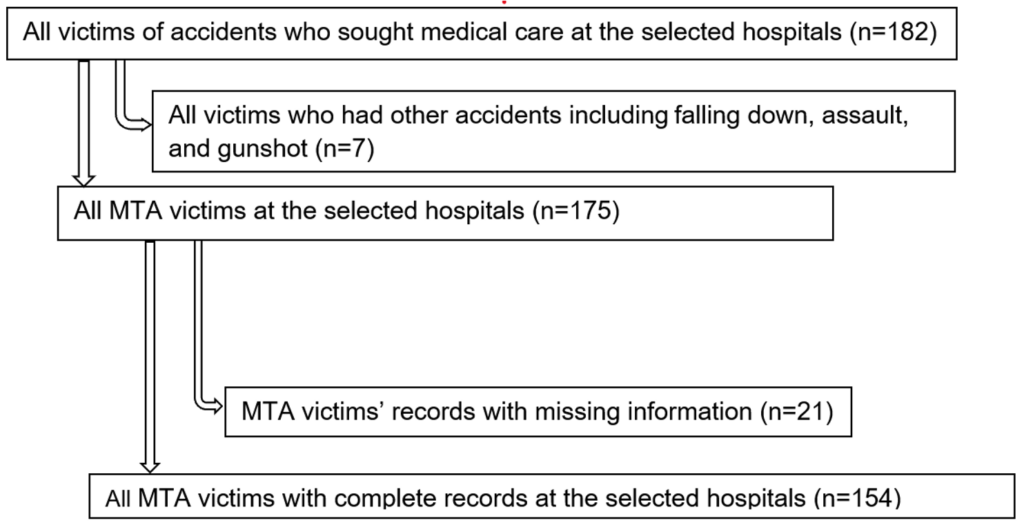

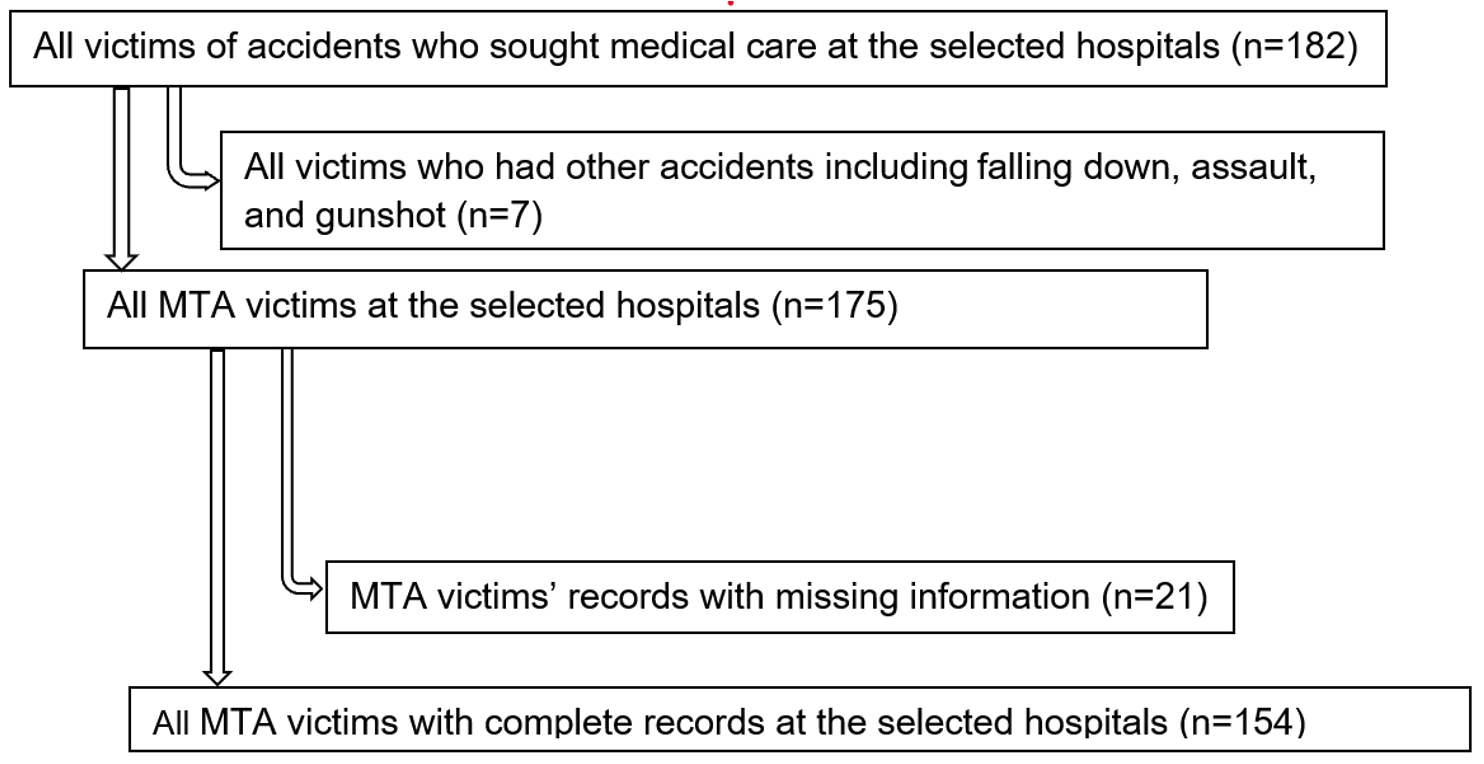

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of MTA victims who sought medical care at selected hospitals within the study period. In total, 182 victims of accidents were involved in the study, with 175 of them having experienced MTAs, while the remaining 7 had other types of accidents, including falling down, assault, and gunshot. However, 21 MTA victims’ records were excluded due to missing information, leaving 154 MTA victims with complete record information for further analysis.

Probability Proportional to size (PPS) was used to calculate the sample size of MTA victims for each selected hospital. Their distribution per hospital was as follows: Ligula Regional Referral Hospital (n = 19, 12.3%), Sokoine Regional Referral Hospital (n = 34, 22.1%), Southern Zone Referral Hospital (n = 4, 2.6%), St. Benedict’s Ndanda Hospital (n = 54, 35.1%), St. Walburg’s Nyangao Hospital (n = 43, 27.9%). These hospitals were selected based on their capacity and the number of MTA victims during the study period.

Sampling technique

Study participants were selected from the dataset using a systematic random sampling method, based on the list of participants in the sampling frame from each selected study site. The sample size for each hospital was determined using PPS. Once the required number of participants for each facility was calculated, a list of all eligible MTA victims who had experienced MTA (the sampling frame) was compiled, and each MTA victim’s record was assigned a unique number. The sampling fraction was calculated by dividing the total number of MTA victims (the sampling frame) by the sample size for each hospital. A random number between 1 and the calculated factor was selected to determine the starting point in the sampling frame. Participants’ records were then selected at regular intervals (based on the obtained factor) using systematic random sampling.

Data collection procedures

Prior to the actual data collection, the quality of the electronic database from each selected site was assessed by the investigators, and a pre-tested paper-based structured data abstraction tool (S1 File) was developed and used to gather both socio-demographic and clinical data. The quality of both databases and the data abstraction tool (S1 File) was assessed by a team of five experts from southern Tanzania, including orthopedic surgeons from the selected sites, epidemiologists, and data scientists. MTA victims were clinically and radiographically assessed using information from their medical records. The diagnosis of FSFs was based on a review of the MTA victim’s history, clinical examination, and radiological findings (anteroposterior and lateral X-rays) from their files. All data were extracted from the MTA victims’ medical records at each selected hospital. The information collected included the MTA victims’ demographic details, the cause of the injury, the side of injury, the anatomical site of the injury, and any associated injuries. To ensure data confidentiality, extraction was done using anonymized MTA victims’ IDs with no personal identifiers collected.

Variables

Dependent variable: The dependent variable was femoral shaft fractures. This was categorised as a binary outcome: either no femoral shaft fracture or femoral shaft fracture.

Independent variables: The independent variables included: age (≤17, 18–34, 35–50, 51–64, and ≥65 years), sex (male or female), occupation status (employed, self-employed, or unemployed), marital status (married, divorced, or single), education level (degree, diploma, certificate, secondary, primary, or no formal schooling), victim category (driver, passenger, or pedestrian), and season of the year included, cold season (May to July), dry season (August to October), or rainy season (November to April).

Investigation tools, validity, and reliability issues

In this study, a structured data abstraction tool (S1 File) was used to collect socio-demographic and clinical information from the MTA victims’ files. The tool was validated through a pilot (pre-testing) phase before the actual data collection to ensure it would yield the desired results. A total of 35 MTA victims’ files (10% of the total) were selected for pre-testing, which were included in the overall study sample. The findings from the pilot study were assessed by five experts, including the orthopedic surgeons from the selected hospitals, and necessary adjustments were made to improve the tool. However, these adjustments did not affect the results since the MTA victims’ records used during pretesting were repeated after the adjustments to the tool.

To ensure reliability and accuracy, the same paper-based tools were administered to all data collectors. Only the principal investigator and trained researchers were involved in the data collection process. Both English and Swahili versions of the structured data abstraction tool were used to gather the required information from the MTA victims’ records.

The validity of the tool was ensured by reviewing all variables with the help of research experts, who provided their input on the items to include, ensuring that the tool covered the research objectives effectively.

Data processing and analysis

Data were accessed for research purposes in all research sites from 01/02/24 to 30/04/24. After data collection, the data were entered into Microsoft Excel® 2019, cleaned, and checked for errors to ensure completeness (S2 File). The data were then double-entered and exported to Stata®version 15 package (StataCorp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: Stata-Corp L.L.C.), for analysis (S2 File). Frequency and proportions were calculated for categorical variables, while continuous variables were summarized using the median and interquartile range (IQR) as measures of central tendency. The association between dependent and independent variables was tested using the Chi-square (X²) test. Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression models were employed to explore the relationships between dependent and independent variables. Bivariate analysis was first conducted to examine the association of each independent variable with the dependent variable. Variables with a p-value < 0.2 in bivariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. Crude odds ratios (cOR) and adjusted odds ratios (aOR), along with their 95% confidence intervals (CI), were used to assess the significance of the independent variables. Variables with a p-value < 0.05 in the multivariate analysis were considered statistically significant, and a 95% CI was used to evaluate the strength of the associations.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the National Health Research Review Committee (NatHREC) of the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR) under identification number: NIMR/HQ/R.8a/VOL.IX/4564. Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the Regional Medical Officers (RMOs) of the selected regions (Mtwara and Lindi), as well as from the District Medical Officers (DMOs) of the selected districts: Mtwara Municipal Council (MC), Masasi District Council (DC), Lindi MC, and Lindi DC. Additionally, approval was granted by the Medical Officers in Charge (MOIs) of the Southern Zone Referral Hospital, Ligula Regional Referral Hospital, St. Benedict’s Ndanda Council Designated Hospital (CDH), Lindi Regional Referral Hospital, and St. Walburg’s Nyangao CDH. The study did not involve direct contact with MTA victims. Confidentiality of the participants was ensured by using special identification codes, and MTA victims’ names and identifying information were excluded from the dataset. Data were securely stored and maintained by the principal investigator, with access granted only to authorised personnel.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the MTA victims in Southern Tanzania

A total of 154 MTA victims were included in this study from five hospitals in Southern Tanzania. The majority were from St. Benedict’s Ndanda Hospital, 35.1% (54/154), and St. Walburg’s Nyangao Hospital, 27.9% (43/154). The median age was 31.5 years (IQR: 22-49). The study MTA victims were predominantly males 76% (117/154), and Muslim, 79.2% (122/154). Occupation-wise, most were self-employed 63% (97/154), followed by students, 19.5% (30/154). Regarding marital status, 57.1% (88/154) were married, and 41.6% (64/154) were single. Education levels varied, with 55.8% (86/154) having primary education and 27.9% (43/154) secondary education. Only 4.6% (7/154) had no formal schooling (Table 1).

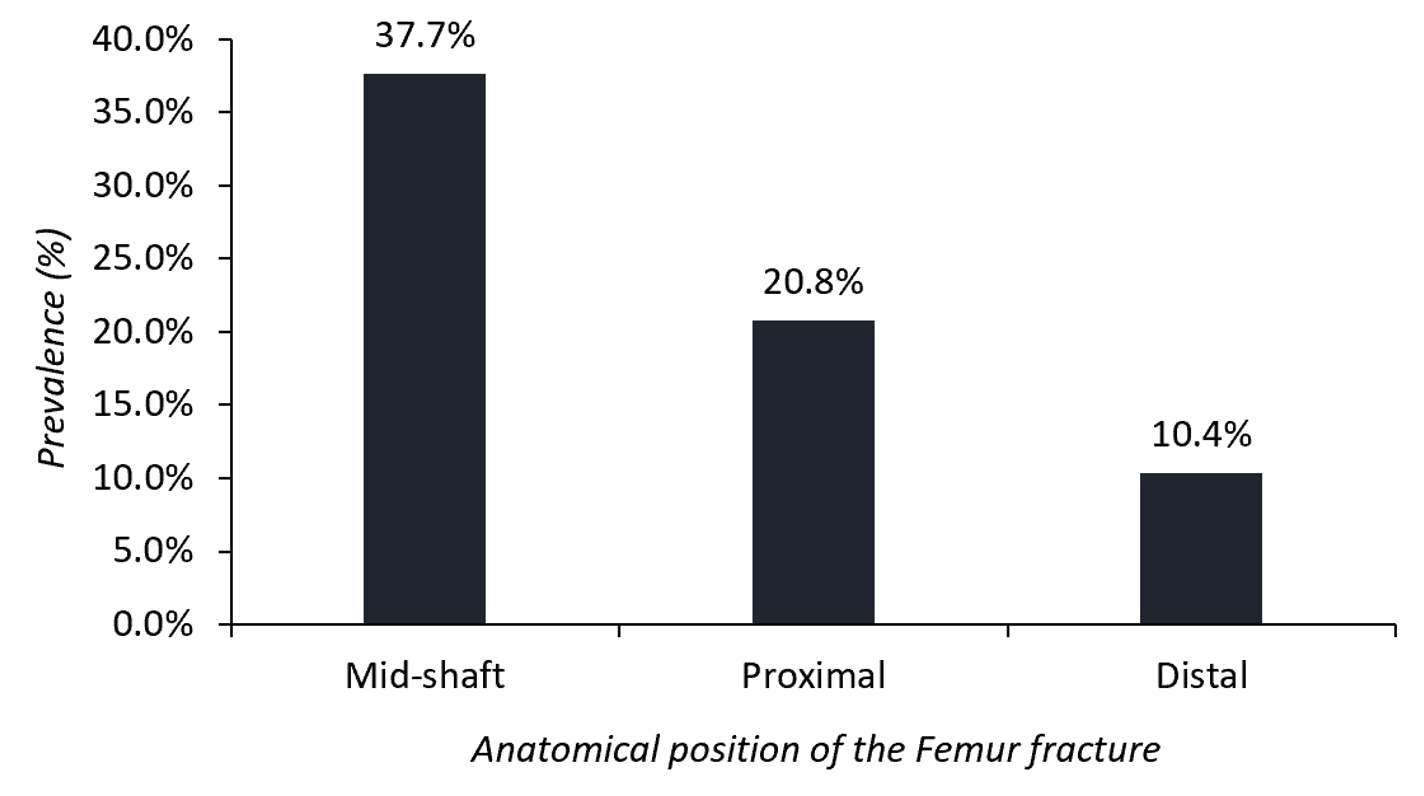

Prevalence of FSFs among MTA victims in Southern Tanzania

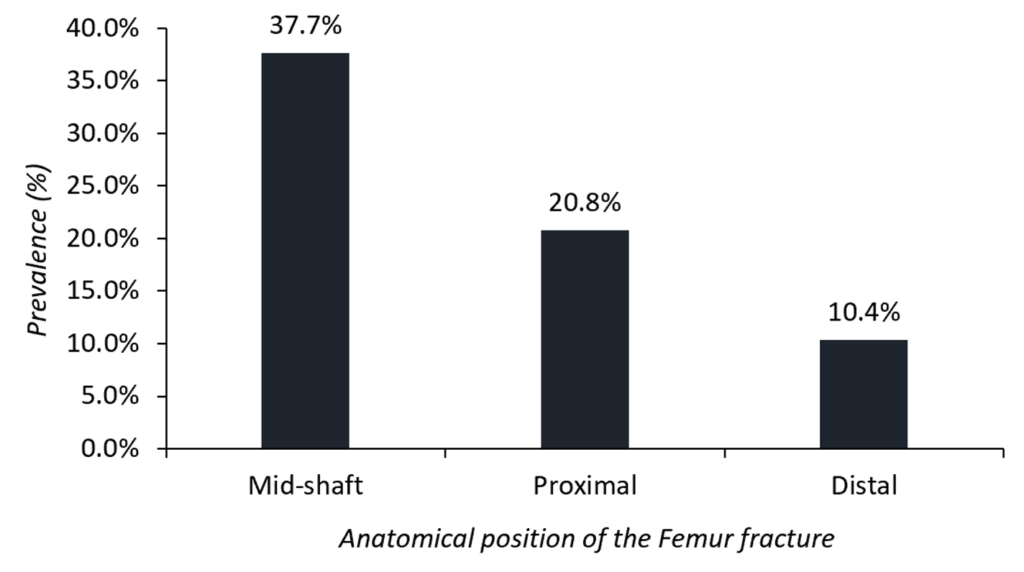

In this study, the prevalence of FSFs among MTA victims in Southern Tanzania was 37.7% (58/154) (Figure 2). The majority (29.3%, 17/58) of MTA victims with FSFs were from St. Walburg’s Nyangao Hospital, and the least (1.7%, 1/58) from Southern Zone Referral Hospital. The prevalence of other Femur fracture patterns was proximal femur 20.8 % (32/154), and the distal femur 10.4% (16/154) (Figure 2).

Distribution of Femur fracture characteristics and associated injuries

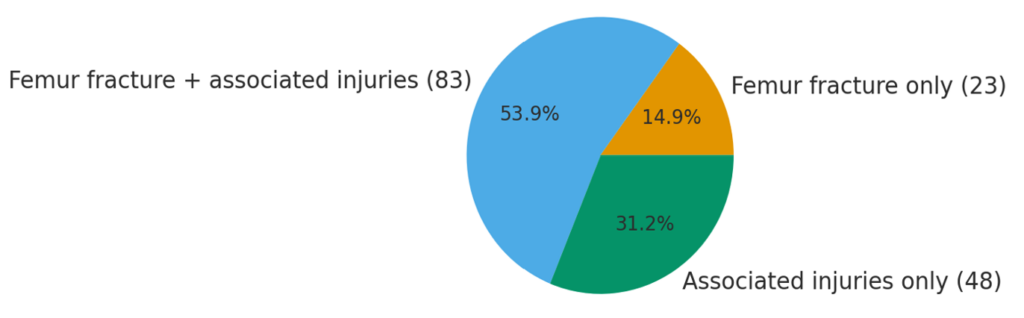

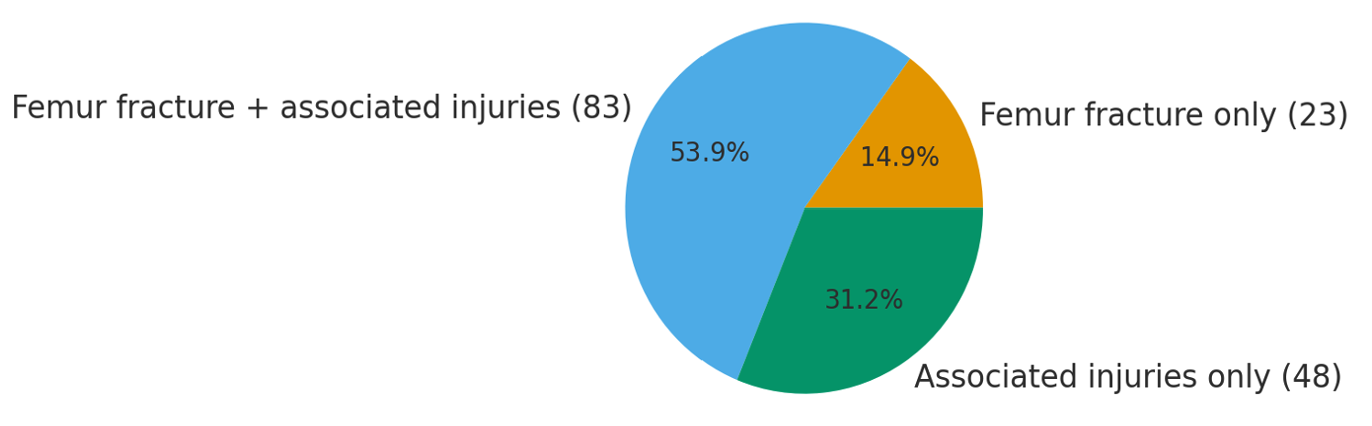

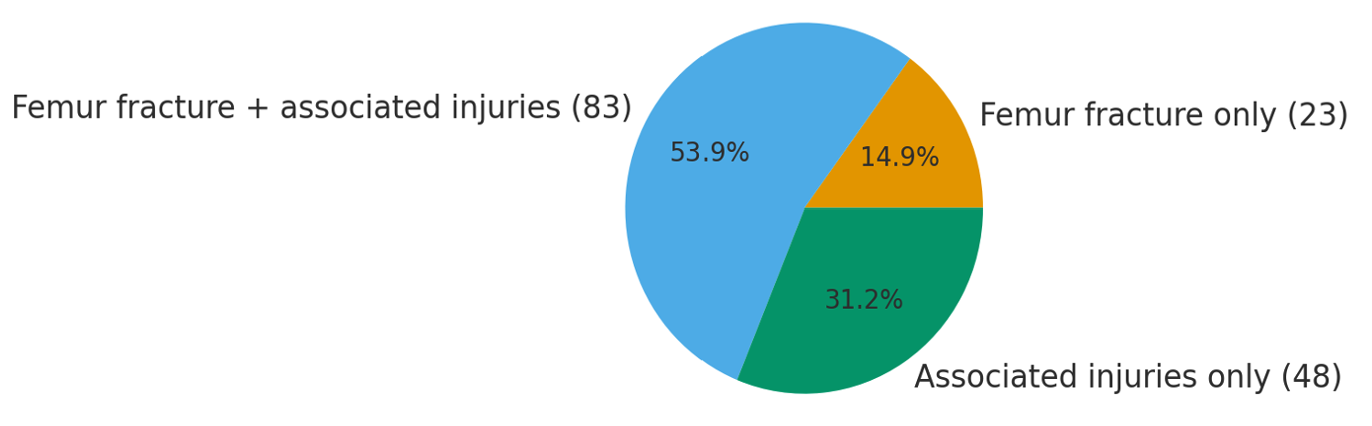

Of the 154 MTA victims, 68.8% (106) sustained femur fractures, with 14.9% (23) having isolated femur fractures and 53.9% (83) experiencing femur fractures with additional injuries. A further 31.2% (48) had associated injuries without femur fractures (Figure 3).

Among the 106 MTA victims with femur fractures, the majority, 84.9% (90/106), had closed fractures. Most of these fractures occurred at the mid-shaft of the femur, 54.7% (58/106), and the proximal site, 30.2% (32/106) (Table 2). Among individuals with femoral shaft fractures, the majority had closed fractures, accounting for 93.1% (54/58). Regarding the side of the fracture, 53.8% (57/106) of MTA victims had fractures on the left femur, and a significant proportion, 81.1% (86/106), had isolated femur fractures (Table 2). The most common fracture pattern was transverse, 54.7% (58/106), and oblique fractures, 34% (36/106) (Table 2).

In the present study, head injuries were the most common, affecting 28.6% (44/154) of all MTA victims, followed by musculoskeletal injuries, 26.0% (40/154). Less common were radius fractures, 2.6% (4/154), and left upper limb fractures, 0.7% (1/154) (Table 3). Head injuries accounted for a high proportion among males, 29.1% (34/117), and musculoskeletal injuries were more frequent in females, 35.1% (13/37), than in males, 23.1% (27/117) (Table 3).

Factors associated with FSFs among MTA victims in Southern Tanzania

In the bivariate analysis using Poisson regression, MTA victims aged 18–34 years had a significantly higher prevalence of FSFs compared to those aged ≥65 years [PR=5.96, 95% CI: 1.55–22.87, p=0.009]. In the multivariate Poisson regression model, this association remained significant, with adjusted Prevalence Odds Ratio (aPOR) = 5.92 (95% CI: 1.39–25.18), p= 0.016, indicating a strong association between younger age and FSFs occurrence (Table 4).

Males showed a significantly higher prevalence of FSFs in bivariate analysis [PR=4.13, 95% CI: 1.60–10.66, p=0.003], and this persisted in multivariate analysis [aPOR=3.34, 95% CI: 1.20–9.33, p=0.021], indicating that males had more than three times the odds of having FSFs compared to females, after adjusting for other variables in the model (Table 4).

Seasonal variation showed a significant effect, where MTA victims in the dry season had a significantly higher prevalence of FSFs compared to those in spring [PR=2.58, 95% CI: 1.22–5.46, p=0.013]. This association remained significant in the multivariate model [aPOR=3.11, 95% CI: 1.33–7.30, p=0.009], showing the seasonal influence on FSFs risk (Table 4).

Discussion

This study revealed the prevalence of FSFs among MTA victims in Southern Tanzania and identified the associated factors for these fractures. The findings revealed that FSFs were prevalent among MTA victims, indicating a significant burden of these injuries in the region. This prevalence is consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated a high incidence of FSFs in LMICs due to the high rate of MTAs and inadequate infrastructure for trauma care[1, 2, 14]. The findings highlight the urgent need for prompt interventions to mitigate the risk of FSFs and improve trauma care in Southern Tanzania.

The high prevalence of FSFs observed in this study reflects the global trend, particularly in LMICs, where MTAs are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality [1, 2]. The WHO reported that approximately 1.2 million people die annually from MTA, and the majority of these deaths occur in LMICs[14]. Tanzania, like many other LMICs, has experienced a rise in MTAs due to increased vehicle usage, poor road conditions, and inadequate enforcement of traffic laws [1, 14]. Studies from other LMICs have similarly reported a high incidence of FSFs among MTA victims, further supporting the notion that MTA is a major contributor to the burden of FSFs in these settings[10, 14].

The predominance of males among the MTA victims with FSFs, and the majority falling within the age range of 18-34 years. This distribution aligns with previous studies that have consistently reported a higher prevalence of FSFs among young adult males[9, 10, 14]. The reasons for this could be attributed to the greater exposure of men to high-risk activities, such as driving and riding motorcycles, as well as their involvement in occupations that predispose them to trauma, including MTA [10]. Additionally, young adults are more likely to engage in risky behaviours, such as speeding and disobeying traffic regulations, which increases their likelihood of being involved in high-energy trauma incidents [9, 14].

In terms of fracture characteristics, the study found that the majority of FSFs occurred at the mid-shaft of the femur. This distribution is consistent with findings from other studies in LMICs, where mid-shaft fractures are the most common type of FSFs due to the high-energy mechanisms typically involved in MTAs [1, 10]. Mid-shaft fractures often result from direct trauma, such as in vehicle collisions, and are associated with significant morbidity and complications[2]. The high incidence of mid-shaft FSFs in this study may be linked to the severity of MTAs in Southern Tanzania and the lack of safety measures, such as seat belts and helmets, which could reduce the impact of trauma.

Associated injuries were also prevalent among MTA victims with FSFs, with head injuries being the most common. The majority of MTA victims sustained head injuries in addition to FSFs. This finding is consistent with previous research that has shown a high rate of associated head injuries in MTA victims with FSFs, particularly in high-energy trauma cases [10, 11]. Head injuries are often life-threatening and can worsen the overall prognosis of patients with FSFs, increasing the risk of long-term disability or death [6, 11]. The high prevalence of associated injuries, including tibia fractures and musculoskeletal injuries, reveals the need for comprehensive trauma care that addresses not only the FSFs but also the other serious injuries that frequently accompany them.

In the present study, young age and male gender were significant risk factors for FSFs. MTA victims aged 18-34 had significantly higher prevalence odds of sustaining FSFs compared to older age groups. Previous studies have also revealed similar results, whereby young adults were more likely to be involved in MTAs and sustain high-energy injuries, such as FSFs [1, 9]. Males were also found to have over three times higher prevalence odds of experiencing FSFs compared to females. This gender difference in FSFs risk has been well-documented in the literature and is often attributed to the higher exposure of males to MTAs and high-risk activities [2, 9].

Seasonal variation was another factor significantly associated with FSFs in this study, with a higher occurrence of FSFs during the dry season compared to spring. The increased incidence of FSFs during the dry season months may be related to increased travel and outdoor activities, leading to a higher likelihood of MTAs. Similar findings have been reported in other studies, where seasonal variations in trauma cases were linked to changes in weather and activity levels [1, 2, 14]. This suggests that public health interventions aimed at reducing MTAs and FSFs should take seasonal patterns into account when planning prevention strategies.

The study findings have important implications for public health policy and trauma care in Tanzania. The high prevalence of FSFs and associated injuries justifies the need for improved trauma care infrastructure, including the availability of surgical implants and trained orthopaedic surgeons, particularly in rural and remote areas[1, 15]. Furthermore, interventions aimed at reducing MTAs, such as stricter enforcement of traffic laws, public education campaigns on road safety, and the promotion of the use of seat belts and helmets, could help reduce the incidence of FSFs and other serious injuries [2, 10, 14].

The present study was conducted in selected referral hospitals, which may not fully represent the broader population of Southern Tanzania, limiting the generalizability of the findings. However, by including referral hospitals within Southern Tanzania, the study aimed to capture a more diverse sample.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates a substantial burden of femoral shaft fractures among MTA victims in Southern Tanzania, with a prevalence of 37.7%. Young adult males were disproportionately affected, underscoring the need for targeted preventive and early intervention strategies. Factors associated with FSFs included age, sex, and seasonal variations. The predominance of FSFs, along with common associated injuries such as head injuries, further complicates the clinical presentation of MTA victims. These findings underscore the need to strengthen trauma care systems and implement effective road-safety and injury-prevention measures to reduce the growing burden of FSFs in Southern Tanzania and the wider region.

What is already known about the topic

- Femoral shaft fractures (FSFs) are among the most serious musculoskeletal injuries and a major cause of disability and mortality in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

- Motor traffic accidents are the leading cause of FSFs worldwide, with LMICs bearing most of the deaths and long-term disability.

What this study adds

- Provides the first multicenter estimate of FSF burden among motor traffic accident victims in Southern Tanzania, showing a high prevalence of femoral shaft fractures.

- Most femoral fractures involve the mid-shaft and are predominantly closed fractures, implying high demand for surgical fixation and rehabilitation.

- Young adult age and male sex are independent predictors of FSFs.

- FSFs occur more often during the dry season, suggesting a clear seasonal pattern that can guide the timing of prevention efforts.

- Head injuries are the most common associated injury, emphasising the need for integrated trauma care (orthopaedic and neuro-trauma) in referral hospitals in Southern Tanzania.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Ministry of Health and the Mtwara Southern Zone Referral Hospital administration for their tremendous support in conducting this research work. Special thanks to the Regional Medical Officers (RMOs) of the selected regions (Mtwara and Lindi), as well as the District Medical Officers (DMOs) of the selected districts: Mtwara Municipal Council (MC), Masasi District Council (DC), Lindi MC, and Lindi DC. Additionally, the authors would like to acknowledge the Executive Director of Southern Zone Referral Hospital and the Medical Officers in Charge (MOIs) of Ligula Regional Referral Hospital, St. Benedict’s Ndanda Council Designated Hospital (CDH), Lindi Regional Referral Hospital, and St. Walburg’s Nyangao CDH.

Authors´ contributions

Conceptualisation: VS, GN, and LM.

Data curation: VS, GN.

Formal analysis: VS.

Methodology: VS, LM.

Resources: HM.

Supervision: LM, HM.

Writing ± original draft: VS, GN.

Writing ± review & editing: VS, GN, LM, and HM.

Supporting information

S1 File: Data Abstraction Tool (116 downloads)

S2 File: Study dataset (119 downloads)

| Characteristic | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Study site | ||

| Ligula Regional Referral Hospital | 19 | 12.3 |

| Sokoine Regional Referral Hospital | 34 | 22.1 |

| Southern Zone Referral Hospital | 4 | 2.6 |

| St. Benedict’s Ndanda Hospital | 54 | 35.1 |

| St. Walburg’s Nyangao Hospital | 43 | 27.9 |

| Age (years) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 31.5 (22–49) | |

| ≤17 | 29 | 18.8 |

| 18–34 | 57 | 37.0 |

| 35–50 | 36 | 23.4 |

| 51–64 | 14 | 9.1 |

| ≥65 | 18 | 11.7 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 37 | 24.0 |

| Male | 117 | 76.0 |

| Religion status | ||

| Christian | 32 | 20.8 |

| Muslim | 122 | 79.2 |

| Occupation status | ||

| Employed | 17 | 11.0 |

| Self-employed | 97 | 63.0 |

| Student | 30 | 19.5 |

| Unemployed | 10 | 6.5 |

| Marital status | ||

| Divorced | 2 | 1.3 |

| Married | 88 | 57.1 |

| Single | 64 | 41.6 |

| Education | ||

| Degree | 8 | 5.2 |

| Diploma | 8 | 5.2 |

| Certificate | 2 | 1.3 |

| Secondary | 43 | 27.9 |

| Primary | 86 | 55.8 |

| No school | 7 | 4.6 |

| Injury characteristic | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Fracture type | ||

| Closed | 90 | 84.9 |

| Open | 16 | 15.1 |

| Fracture anatomical site | ||

| Proximal | 32 | 30.2 |

| Mid-shaft | 58 | 54.7 |

| Distal | 16 | 15.1 |

| Side of Femur fracture | ||

| Left | 57 | 53.8 |

| Right | 49 | 46.2 |

| Isolated Femur fracture | ||

| No | 20 | 18.9 |

| Yes | 86 | 81.1 |

| Pattern of femur fracture | ||

| Transverse | 58 | 54.7 |

| Oblique | 36 | 34.0 |

| Spiral | 3 | 2.8 |

| Comminuted | 9 | 8.5 |

| Type of associated injury | Female (N=37) n (%) | Male (N=117) n (%) | Total (N=154) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head injury | 10 (27.0) | 34 (29.1) | 44 (28.6) |

| Musculoskeletal injury | 13 (35.1) | 27 (23.1) | 40 (26.0) |

| Tibia fracture | 10 (27.0) | 12 (10.3) | 22 (14.3) |

| Chest injury | 2 (5.4) | 9 (7.7) | 11 (7.1) |

| Visceral injury | 1 (2.7) | 8 (6.8) | 9 (5.8) |

| Radius fracture | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.4) | 4 (2.6) |

| Left upper limb fracture | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.7) |

| No associated injuries | 1 (2.7) | 22 (18.8) | 23 (14.9) |

| Variable | FSFs status | Bivariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | PR (95% CI) | p-value | aPOR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age (in years) | ||||||

| ≤17 | 25 (86.2) | 4 (13.8) | 0.80 (0.16-4.08) | 0.788 | 1.68 (0.17-16.25) | 0.656 |

| 18–34 | 26 (45.6) | 31 (54.4) | 5.96 (1.55-22.87) | 0.009 | 5.92 (1.39-25.18) | 0.016* |

| 35–50 | 21 (58.3) | 15 (41.7) | 3.57 (0.88-14.56) | 0.076 | 3.58 (0.80-15.95) | 0.094 |

| 51–64 | 9 (64.3) | 5 (35.7) | 2.78 (0.53-14.50) | 0.226 | 2.47 (0.42-14.43) | 0.317 |

| ≥65 | 15 (83.3) | 3 (16.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 31 (83.8) | 6 (16.2) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Male | 65 (55.6) | 52 (44.4) | 4.13 (1.60-10.66) | 0.003 | 3.34 (1.20-9.33) | 0.021* |

| Occupation status | ||||||

| Employed | 9 (52.9) | 8 (47.1) | 1.33 (0.27-6.50) | 0.722 | 1.05 (0.17-6.43) | 0.955 |

| Self-employed | 56 (57.7) | 41 (42.3) | 1.10 (0.29-4.14) | 0.890 | 1.18 (0.25-5.51) | 0.837 |

| Unemployed | 6 (60.0) | 4 (40.0) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 53 (60.2) | 35 (39.8) | 1 | |||

| Divorced | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 1.51 (0.09-25.01) | 0.772 | ||

| Single | 42 (65.6) | 22 (34.4) | 0.79 (0.41-1.55) | 0.498 | ||

| Education status | ||||||

| Degree | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | 0.75 (0.10-5.77) | 0.782 | ||

| Secondary | 27 (62.8) | 16 (37.2) | 0.44 (0.09-2.24) | 0.326 | ||

| No school | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) | 1 | |||

| Victim Category | ||||||

| Driver | 24 (49.0) | 25 (51.0) | 1.74 (0.74-4.06) | 0.204 | ||

| Passenger | 47 (72.3) | 18 (27.7) | 0.64 (0.28-1.48) | 0.295 | ||

| Pedestrian | 25 (62.5) | 15 (37.5) | 1 | |||

| Season of the year | ||||||

| Rainy season | 40 (75.5) | 13 (24.5) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Dry season | 50 (54.4) | 42 (45.6) | 2.58 (1.22-5.46) | 0.013 | 3.11 (1.33-7.30) | 0.009* |

| Cold season | 6 (66.7) | 3 (33.3) | 1.54 (0.34-7.04) | 0.579 | 1.64 (0.30-9.08) | 0.569 |

References

- Conway D, Albright P, Eliezer E, Haonga B, Morshed S, Shearer DW. The burden of femoral shaft fractures in Tanzania. Injury [Internet]. 2019 Jun [cited 2025 Nov 20];50(7):1371-5. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0020138319303365 doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2019.06.005.

- Agarwal-Harding KJ, Meara JG, Greenberg SLM, Hagander LE, Zurakowski D, Dyer GSM. Estimating the global incidence of femoral fracture from road traffic collisions: a literature review. J Bone Joint Surg Am [Internet]. 2015 Mar 18 [cited 2025 Nov 20];97(6):e31. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/00004623-201503180-00014 doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.00314. Purchase or subscription required to view full text.

- Enninghorst N, McDougall D, Evans JA, Sisak K, Balogh ZJ. Population-based epidemiology of femur shaft fractures. J Trauma Acute Care Surg [Internet]. 2013 Jun [cited 2025 Nov 20];74(6):1516-20. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/01586154-201306000-00021 doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31828c3dc9. Purchase or subscription required to view full text.

- Schade AT, Mbowuwa F, Chidothi P, MacPherson P, Graham SM, Martin C, Harrison WJ, Chokotho L. Epidemiology of fractures and their treatment in Malawi: results of a multicentre prospective registry study to guide orthopaedic care planning. PLoS One [Internet]. 2021 Aug 4 [cited 2025 Nov 20];16(8):e0255052. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255052 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255052.

- Salonen A, Laitakari E, Berg HE, Felländer-Tsai L, Mattila VM, Huttunen TT. Incidence of femoral fractures in children and adolescents in Finland and Sweden between 1998 and 2016: a binational population-based study. Scand J Surg [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Nov 20];111(1):14574969221083133. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/14574969221083133 doi: 10.1177/14574969221083133.

- Chad A, Asplund , Mezzanotte TJ. Midshaft femur fractures in adults [Internet]. Waltham (MA): UpToDate; c2025 [updated 2025 Apr 14; cited 2025 Nov 20]. Available from: http://112.2.34.14:9095/contents/midshaft-femur-fractures-in-adults/print.

- Gathecha GK, Ngaruiya C, Mwai W, Kendagor A, Owondo S, Nyanjau L, Kibogong D, Odero W, Kibachio J. Prevalence and predictors of injuries in Kenya: findings from the national STEPs survey. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2018 Nov 7 [cited 2025 Nov 20];18(Suppl 3):1222. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-018-6061-x doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6061-x.

- ORCA Study Group. Open tibial shaft fractures: treatment patterns in sub-Saharan Africa. OTA Int [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Nov 20];6(2):e228. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/otai/fulltext/2023/03000/open_tibial_shaft_fractures__treatment_patterns_in.1.aspx doi: 10.1097/OI9.0000000000000228.

- Kalande FM. Treatment outcomes of open femoral fractures at a county hospital in Nakuru, Kenya. East Afr Orthop J [Internet]. 2018 Sep [cited 2025 Nov 20];12(2):52-5. Available from: https://files.core.ac.uk/download/478426614.pdf.

- Chagomerana MB, Tomlinson J, Young S, Hosseinipour MC, Banza L, Lee CN. High morbidity and mortality after lower extremity injuries in Malawi: a prospective cohort study of 905 patients. Int J Surg [Internet]. 2017 Mar [cited 2025 Nov 20];39:23-9. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S174391911730050X doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.01.047.

- Macha AP, Temu R, Olotu F, Seth NP, Massawe HL. Epidemiology and associated injuries in paediatric diaphyseal femur fractures treated at a limited resource zonal referral hospital in northern Tanzania. BMC Musculoskelet Disord [Internet]. 2022 Apr 18 [cited 2025 Nov 20];23(1):360. Available from: https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12891-022-05320-x doi: 10.1186/s12891-022-05320-x.

- Hollis AC, Ebbs SR, Mandari FN. The epidemiology and treatment of femur fractures at a northern Tanzanian referral centre. Pan Afr Med J [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2025 Nov 20];22:338. Available from: http://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/22/338/full/ doi: 10.11604/pamj.2015.22.338.8074.

- National Bureau of Statistics (Tanzania), President’s Office (Tanzania). Mtwara (Region, Tanzania) – Population Statistics, Charts, Map and Location. Dodoma (Tanzania): National Bureau of Statistics; 2022.

- Sonbol A, Almulla A, Hetaimish B, Taha W, Mohmmedthani T, Alfraidi T, Alrashidi Y. Prevalence of femoral shaft fractures and associated injuries among adults after road traffic accidents in a Saudi Arabian trauma center. J Musculoskelet Surg Res [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 Nov 20];2(2):62-5. Available from: https://journalmsr.com/prevalence-of-femoral-shaft-fractures-and-associated-injuries-among-adults-after-road-traffic-accidents-in-a-saudi-arabian-trauma-center/ doi: 10.4103/jmsr.jmsr_42_17.

- Ugezu AI, Nze IN, Ihegihu CC, Chukwuka NC, Ndukwu CU, Ofialei OR. Management of femoral shaft fractures in a tertiary centre, South East Nigeria. Afrimedic J [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 Nov 20];6(1):27-34. Available from: https://scispace.com/pdf/management-of-femoral-shaft-fractures-in-a-tertiary-centre-2e4vewwfzq.pdf.