Research | Open Access | Volume 8 (4): Article 99 | Published: 02 Dec 2025

Pattern and predictors of healthcare providers' recommendations for human papillomavirus vaccination in Ebonyi State, Nigeria

Menu, Tables and Figures

Navigate this article

Tables

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 187 | 20.0 |

| Female | 748 | 80.0 |

| Age group (years) | ||

| 20–29 | 247 | 26.4 |

| 30–39 | 372 | 39.8 |

| 40–49 | 202 | 21.6 |

| 50–59 | 106 | 11.3 |

| ≥60 | 8 | 0.9 |

| Mean ± SD | 36.6 ± 9.5 | |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 275 | 29.4 |

| Married | 622 | 66.5 |

| Divorced/Separated | 7 | 0.7 |

| Widowed | 31 | 3.3 |

| Religion | ||

| Christianity | 919 | 98.3 |

| Islam | 10 | 1.1 |

| African Tradition | 5 | 0.5 |

| Others | 1 | 0.1 |

| Denomination (n=919) | ||

| Catholic | 393 | 42.8 |

| Orthodox | 125 | 13.6 |

| Pentecostal | 377 | 41.0 |

| Others | 24 | 2.6 |

| Cadre | ||

| Medical Doctor | 66 | 7.1 |

| Registered Nurse | 265 | 28.3 |

| Community Health worker | 175 | 18.7 |

| Community Health Extension worker | 219 | 23.4 |

| Health Assistant | 147 | 15.7 |

| Others | 63 | 6.7 |

| Highest Educational attainment | ||

| WAEC O’ level* | 176 | 18.8 |

| OND/HND* | 385 | 41.2 |

| University Degree | 325 | 34.8 |

| Post-graduate Degree | 49 | 5.2 |

| Monthly Salary (Naira ₦) | ||

| < ₦200,000 | 815 | 87.2 |

| ₦200,000 – ₦500,000 | 108 | 11.6 |

| ₦500,001 – ₦1,000,000 | 12 | 1.3 |

| Facility Ownership | ||

| Government | 779 | 83.3 |

| Private | 156 | 16.7 |

| Facility Tier | ||

| Primary | 513 | 54.9 |

| Secondary | 238 | 25.5 |

| Tertiary | 184 | 19.7 |

| Location of Practice | ||

| Ebonyi Central | 203 | 21.7 |

| Ebonyi North | 472 | 50.5 |

| Ebonyi South | 260 | 27.8 |

| Years of Practice | ||

| <5 | 207 | 22.1 |

| 5–10 | 410 | 43.9 |

| >10 | 318 | 34.0 |

*OND = Ordinary National Diploma; HND = Higher National Diploma; WAEC = West African Examination Council

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents (N=935)

| Variables | HPV vaccine recommendation | COR (95% CI) | P value | aOR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequent (%) 349 (37.3) | Infrequent (%) 586 (62.7) | |||||

| Age group | ||||||

| <40 | 174 (28.1) | 445 (71.9) | 0.31 (0.24–0.42) | <0.001 | 0.50 (0.28–0.90) | 0.020 |

| ≥40 | 175 (55.4) | 141 (44.6) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 70 (37.4) | 117 (62.6) | 1.01 (0.72–1.40) | 0.973 | – | – |

| Female | 279 (37.3) | 469 (62.7) | 1 | – | – | |

| Education status | ||||||

| WAEC O’ Level | 53 (30.1) | 123 (69.9) | 0.77 (0.52–1.14) | 0.194 | 0.06 (0.01–0.22) | <0.001 |

| OND/HND | 203 (52.7) | 182 (47.3) | 0.30 (0.22–0.40) | <0.001 | 0.31 (0.14–0.71) | 0.005 |

| Above Diploma | 93 (24.9) | 281 (75.1) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 92 (33.5) | 183 (66.5) | 1.16 (0.57–2.35) | 0.679 | – | – |

| Married | 243 (39.1) | 379 (60.9) | 0.91 (0.46–1.79) | 0.785 | – | – |

| Others | 14 (36.8) | 24 (63.2) | 1 | – | – | |

| Denomination | ||||||

| Catholic | 122 (31.0) | 271 (69.0) | 3.70 (1.58–8.69) | 0.003 | 3.32 (0.80–13.80) | 0.099 |

| Orthodox | 23 (18.4) | 102 (81.6) | 7.39 (2.88–19.00) | <0.001 | 3.60 (0.77–16.85) | 0.105 |

| Pentecostal | 188 (49.9) | 189 (50.1) | 1.67 (0.72–3.92) | 0.234 | 1.71 (0.42–7.04) | 0.456 |

| Others | 15 (62.5) | 9 (37.5) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Cadre | ||||||

| Clinical staff | 106 (32.0) | 225 (68.0) | 0.68 (0.46–1.01) | 0.054 | 0.38 (0.10–1.43) | 0.152 |

| Community Health workers | 192 (48.7) | 202 (51.3) | 0.34 (0.23–0.49) | <0.001 | 0.92 (0.28–2.99) | 0.884 |

| Other health professionals | 51 (24.3) | 159 (75.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Facility tier | ||||||

| Primary | 225 (43.9) | 288 (56.1) | 0.64 (0.45–0.90) | 0.012 | 0.78 (0.37–1.66) | 0.521 |

| Secondary | 63 (26.5) | 175 (73.5) | 1.38 (0.90–2.10) | 0.136 | 1.35 (0.59–3.05) | 0.475 |

| Tertiary | 61 (33.2) | 123 (66.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Years of practice | ||||||

| 1–10 years | 178 (28.8) | 439 (71.2) | 0.35 (0.26–0.46) | <0.001 | 0.63 (0.36–1.12) | 0.114 |

| Above 10 years | 171 (53.8) | 147 (46.2) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Facility ownership | ||||||

| Government | 283 (36.3) | 496 (63.7) | 1.29 (0.91–1.82) | 0.159 | 1.72 (0.87–3.40) | 0.117 |

| Private | 66 (42.3) | 60 (57.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Actual knowledge | ||||||

| Good | 322 (68.2) | 150 (31.8) | 34.66 (22.45–53.52) | <0.001 | 12.38 (7.28–21.10) | <0.001 |

| Poor | 27 (5.8) | 436 (94.2) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Self knowledge | ||||||

| Good | 307 (52.4) | 279 (47.6) | 8.04 (5.61–11.54) | <0.001 | 2.94 (1.74–4.96) | <0.001 |

| Poor | 42 (12.0) | 307 (88.0) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Attitude | ||||||

| Good | 336 (55.6) | 268 (44.4) | 30.67 (17.22–54.63) | <0.001 | 15.62 (7.76–31.44) | <0.001 |

| Poor | 13 (3.9) | 318 (96.1) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Training on HPV vaccination attended | ||||||

| Yes | 267 (57.8) | 195 (42.2) | 6.59 (4.87–8.93) | <0.001 | 1.28 (0.69–2.40) | 0.437 |

| No | 80 (17.2) | 385 (82.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. COR = Crude Odds Ratio; aOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio.

Table 2: Predictors of HPV recommendations among Healthcare providers in Ebonyi State<

Figures

Keywords

- HPV vaccine

- Human Papillomavirus

- Healthcare Provider

- Healthcare Utilisation

- Immunisation

- Nigeria

Chidinma Ihuoma Amuzie1,2,&, Christian Akpa3, Benedict Ndubueze Azuogu3, Kalu Ulu Kalu1, Naiya Ahmed2, Amos Paul Bassi2

1Department of Community Medicine, Federal Medical Centre, Umuahia, Abia State, Nigeria, 2John Snow Inc., Abuja, Nigeria, 3Department of Community Medicine, Alex Ekwueme Teaching Hospital, Abakaliki, Ebonyi State, Nigeria

&Corresponding author: Chidinma Ihuoma Amuzie, Department of Community Medicine, Federal Medical Centre, Umuahia, Abia State, Nigeria. Email: Ihuoma1712@yahoo.com ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6070-1330

Received: 09 Oct 2025, Accepted: 02 Dec 2025, Published: 02 Dec 2025

Domain: Vaccine Preventable Diseases, Cancer Epidemiology

Keywords: HPV vaccine, Human Papillomavirus, Healthcare Provider, Healthcare Utilisation, Immunisation, Nigeria

©Chidinma Ihuoma Amuzie et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Chidinma Ihuoma Amuzie et al., Pattern and predictors of healthcare providers’ recommendations for human papillomavirus vaccination in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8(4):99. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00225

Abstract

Introduction: Nigeria recently introduced the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine into its National Programme of Immunization (NPI). The uptake of this vaccine was fraught with several challenges, such as misinformation, vaccine hesitancy and belief barriers. Healthcare provider recommendations are known to improve the uptake of HPV vaccine. This study assessed the pattern and predictors of HPV vaccine recommendations among healthcare providers in Ebonyi State, Nigeria.

Methods: This was a facility-based cross-sectional study conducted from July to August 2024 among healthcare providers in Ebonyi State. The respondents were selected using a multistage sampling technique. An interviewer-administered structured questionnaire programmed into Open Data Kit was used to collect data. Descriptive, bivariate, and multivariate analyses were done using IBM Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) version 26. The level of significance was set at 5%.

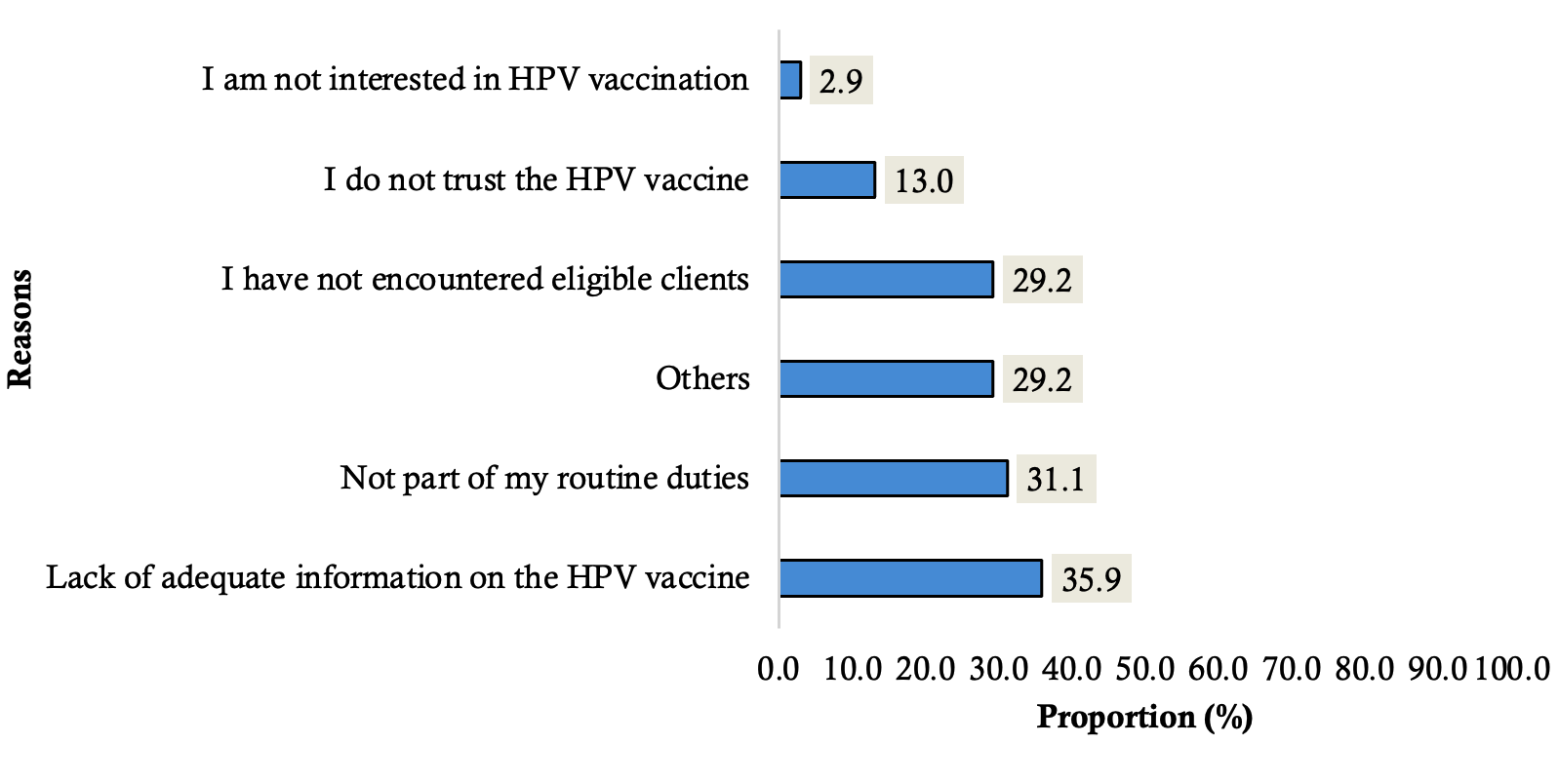

Results: A total of 935 healthcare providers participated in the survey. The mean age of the respondents was 36.6±9.5 years. The prevalence of frequent recommendations of HPV vaccination was 37.3% (95% CI: 34.1 – 40.6). Among those who had never recommended the vaccine (33.7%), the most frequent reasons included lack of information (35.9%) and the perception that vaccine recommendation was not their duty (31.1%). The independent predictors of HPV vaccine recommendation by healthcare providers included age (aOR=0.50; 95% CI: 0.28 – 0.90), education [(West African Examination Council O’ level; aOR = 0.06; 95% CI: 0.01–0.22) and (Ordinary National Diploma/Higher National Diploma; aOR = 0.31; 95% CI: 0.14–0.71)], actual knowledge (aOR=12.38; 95% CI: 7.28 – 21.10), self-reported knowledge (aOR=2.94; 95% CI: 1.74 – 4.96) and attitude to HPV vaccination (aOR=15.62; 95% CI: 7.76 – 31.44).

Conclusions: Only one third of the healthcare providers frequently recommended the HPV vaccine. Age, educational status, knowledge of HPV vaccination, and attitude of healthcare providers to HPV vaccination were associated with HPV vaccine recommendation by healthcare providers. Reorienting healthcare providers through regular training sessions on the national HPV vaccination guidelines, while designing targeted health education programmes to address identified knowledge gaps among healthcare providers, is recommended.

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common viral sexually transmitted infection (STI) of the reproductive tract and is attributed to several conditions in men and women [1]. In women, persistent infection with oncogenic HPV types may lead to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) [1]. Globally, cervical cancer ranks as the fourth most common cancer among women in both incidence and mortality, accounting for approximately 661,021 new cases and 348,189 deaths in 2022 [2]. In 2020, Nigeria contributed to about 2% of the global burden of cervical cancer, with up to 12,078 new cases reported [3]. The first vaccine for the prevention of HPV-related disease was licensed in 2006 [1].

The global strategy by the World Health Organization (WHO) to eliminate cervical cancer proposes a threshold incidence of 4 per 100,000 women years for elimination as a public health problem, and the achievement of 90-70-90 targets to be met by 2030 for all countries on the pathway to cervical cancer elimination [4]. These targets focus on primary, secondary, and tertiary preventive measures, and vaccination remains the most cost-effective intervention in the prevention of diseases [4]. The Federal Government of Nigeria, with the support of Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and other partners, launched the HPV vaccine on October 24, 2023, in a phased approach targeting girls aged 9-14 years with a single dose of Gardasil 4. Ebonyi State, one of the phase 2 states, introduced the HPV vaccine on May 27, 2024.

In Nigeria, low HPV vaccine acceptance has been attributed to conspiracy theories and myths concerning vaccination among parents and caregivers [5]. Other barriers reported by parents include concerns about side-effects, cost of the vaccine, low awareness, and fear of sexual promiscuity after the vaccination for protection [6–8]. Some health system barriers include laws governing vaccine requirements and exemption policies, and lack of access [9].

Studies have shown that healthcare providers’ (HCPs) recommendation enhances the acceptance of HPV [10,11]. A study has shown that parental confidence improved after discussing with a HCP [12]. Lower prevalences of HPV vaccine recommendations among HCPs have been documented in Japan and China [10,13]. Some of the reasons cited in studies for the lack of HCP recommendations for the HPV vaccine included a lack of support from the government, vaccine unavailability, and lack of effective communication tools [9,14]. It is known that the actual recommendation compared to the intention to recommend is a better assessment of HCP recommendation behaviour [13]. However, there is a paucity of data on the pattern and predictors of HPV vaccine recommendation by the HCPs in Ebonyi State. Therefore, this study provides insight into the pattern of HPV vaccine recommendation by HCPs and acts as a baseline assessment for evaluating interventions towards frequent HPV vaccine recommendation by HCPs in Ebonyi State. This study assessed the pattern and predictors of HPV vaccine recommendations among HCPs in Ebonyi State.

Methods

Study design and setting

This was a facility-based cross-sectional study. The study was conducted from July to August 2024 in three selected Local Government Areas (LGAs) in Ebonyi State (one LGA in each Senatorial zone). Ebonyi State is in the southeastern region of Nigeria with a 2023 projected population of 3,434,945 based on the 2006 national census figure and a growth rate of 2.8% and Christianity is the most practiced religion. Ebonyi State has 13 LGAs and 297 health wards. There are 546 health facilities in the state; 530 primary healthcare facilities, 13 secondary healthcare facilities, and three tertiary health institutions: Alex Ekwueme University Teaching Hospital, Abakaliki (AEFUTHA), National Obstetric Fistula Centre (NOFIC) and David Umahi Federal University Teaching Hospital (DUFUTH). Most of these facilities conduct routine immunization services as well as offer cervical cancer screening services. Gardasil 4 is the recommended vaccine used for eligible girls 9 to 14 years in Nigeria with a single dose vaccination schedule.

The National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) provides vaccines and related products, while the State Ministry of Health (SMOH) and the State Primary Health Care Development Agency (SPHCDA) coordinate the implementation of immunization/vaccination service delivery at the state and LGA levels through the tertiary, secondary, and primary healthcare (PHC) facilities.

Study participants

This comprised all HCPs working in healthcare facilities located in Ebonyi State. All health staff who have direct contact with patients by providing medical services and other healthcare services in the health facilities, Ad-hoc and contract staff in the selected facilities were included in the study. In contrast, non-clinical staff, those who were absent due to sickness, work leave, and those who were unable to communicate effectively due to debilitating illnesses, were excluded.

Sample size determination

The sample size was calculated using the formula

$$ n = \frac{(Z_\alpha + Z_\beta)^2 \, p q}{d^2} $$

with an error margin of 5%. The proportion (p) of HPV vaccine recommendations from HCPs of 30.2% based on a previous study in China[13], power of 80% and a precision of 5%, was used to compute the sample size. A non-response rate of 20% was assumed, giving a minimum sample size of approximately 827 participants.

Sampling procedure

Multistage random sampling was used to select the eligible respondents. In the first stage, 3 LGAs (Ohaozara, Abakaliki and Ezza North LGAs) were randomly selected from the 13 LGAs in the state. In the second stage, all health facilities within the selected LGAs were listed, and the number of respondents to be recruited from each LGA was allocated proportionally to the number of facilities in that LGA. In the third stage, the number of facilities to be selected from each LGA was determined by dividing the allocated sample size by the planned average number of respondents to be recruited per facility (approximately 5 per facility). The health facilities were selected using a simple random sampling technique from the sampling frame of listed health facilities.

Eligible participants were chosen through simple random sampling using staff lists or rosters available at the facilities. Random numbers were generated using OpenEpi (Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health), a free, web-based statistical tool for epidemiologic data analysis. In facilities with fewer than five eligible respondents, all were invited to participate.

Data collection tool and methods

A structured interviewer-administered questionnaire that was adapted from previous studies was used to collect information from the eligible respondents [9,10,13]. The reliability and validity of the questionnaire were assessed using content and face validity. The Cronbach Alpha was 71.9%. The 36-item questionnaire comprised four sections: Section 1, which contained sociodemographic information; Section 2 focused on the frequency of HPV vaccine recommendations; Section 3 consisted of information on knowledge of HPV; and Section 4 addressed attitudes towards HPV-related topics. A pretest was done in a non-sampled LGA using 5% of the sample questionnaires to establish face validity. The result of the pretest was used to improve the questionnaire’s clarity, wording, and the questions’ logical sequence.

The questions were built on KoboCollect, an open source mobile data collection application and deployed on the Open Data Kit (ODK) platform through the access link and password, programmed on smartphones. A total of nine research assistants were recruited for this study, and they were trained to administer the questionnaires to the respondents. There was a one-day training for the research assistants by the senior research team members on the ethics and interviewing process of the research. The estimated time for an interview section was 10 to 15 minutes. The respondents were requested to provide informed consent by clicking ‘yes’ after reviewing the informed consent note.

Measurement of variables

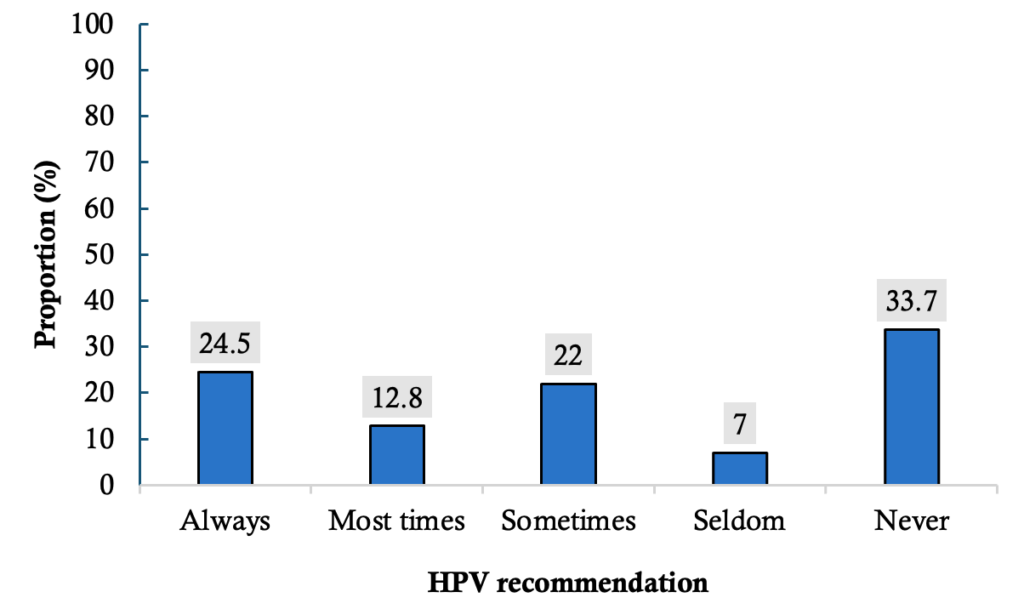

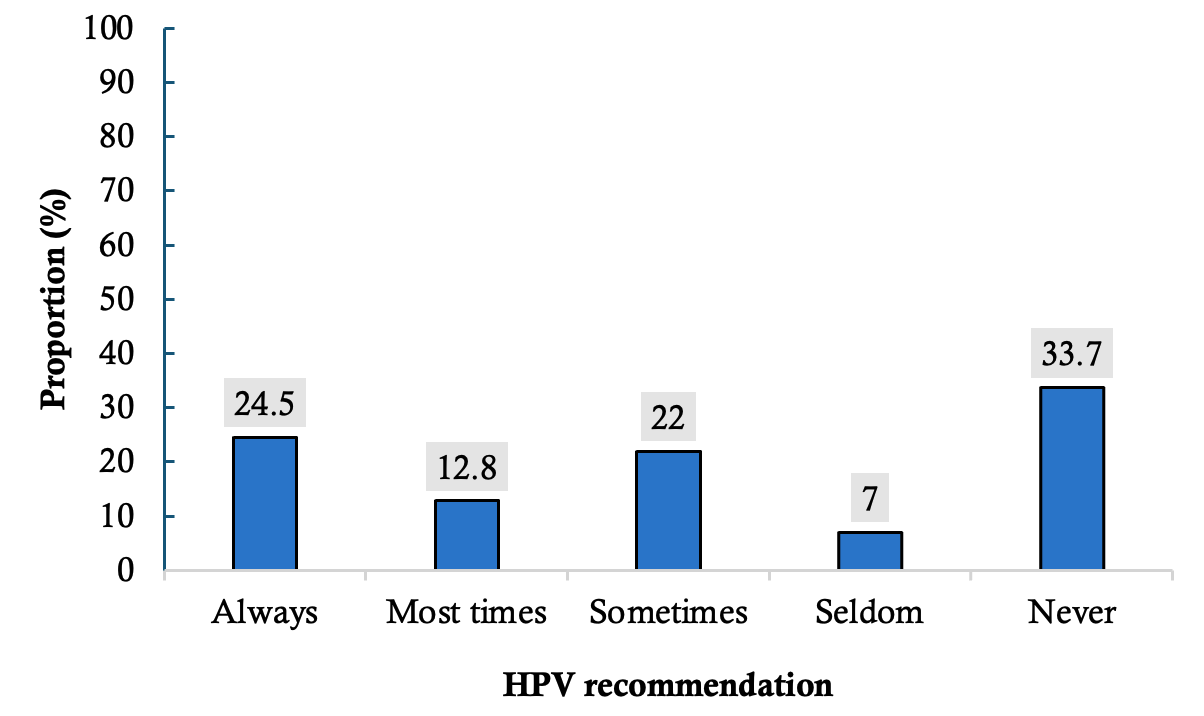

The outcome variable of this study was the HPV vaccine recommendation by the HCPs. It was assessed by the question, ‘How often have you recommended the HPV vaccine to eligible girls in the past 3 months?’ This was further measured on a 5-point Likert scale of ‘Never’, ‘Seldom’, ‘Sometimes’, ‘Most times’ and ‘Always’ [13]. The frequency for each scale was captured as follows; Always (done almost every day≥ 5 – 7 times/week), Most times (Done 3 – 4 times per week), Sometimes (Done 1 – 2 times per week), Seldom (done about 1 – 2 times per month) and Never (Not done at all, zero times per week). During analysis, responses were dichotomized into frequent (Always, most times), coded as ‘1’ and infrequent (never, seldom, and sometimes), coded as ‘0’. The independent variables included socio-demographics such as age, sex, education status, cadre, religion, denomination, tier of facility and income.

Actual and self-reported knowledge of HPV vaccination was assessed using 10 questions and three questions for actual and self-reported knowledge, respectively. The questions measuring actual knowledge were multiple-choice questions that had only one correct response. Each correct answer was scored 1 point, with a minimal and maximal score of 0 and 10, respectively, for actual knowledge. For self-reported knowledge, each correct answer was scored 1 point, with a minimal and maximal score of 0 and 3, respectively for self-reported knowledge. Scores greater than the mean of the actual knowledge score (6.08) and self-reported knowledge score (2.37) were categorized as ‘good knowledge’. Scores below the mean value of the actual knowledge score and self-reported score were categorized as ‘poor knowledge’.

Eight questions were used to assess the attitude of HCPs to HPV vaccine recommendation. The variables were measured using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’, scoring 1 to 5, respectively. The minimal and maximal total scores were 8 and 40, respectively. Good attitude was rated for scores above the mean attitude score (29.7), while low attitude scores referred to scores below the mean. The STROBE guidelines for cross-sectional studies were adopted for reporting to ensure that all items are captured.

Statistical analysis

The data was downloaded from the Kobo Collect server in Excel format. It was cleaned and exported to Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) version 26 for analysis. Univariate analysis was used to generate the frequencies and proportions of the study population across the independent variables. Binary logistic regression was used to test for associations between independent variables and HPV vaccine recommendation by the HCPs. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Multivariable logistic analysis was conducted to determine the predictors of HCP recommendation for the HPV vaccine. Factors that fit into the regression model were those with p-values < 0.2 at the level of bivariate analysis. The results of the regression analysis were reported in terms of adjusted Odds Ratios, 95% confidence intervals and p-values. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Alex Ekwueme Teaching Hospital, Abakaliki, Ebonyi State, with the HREC Approval number – NHREC/16/05/22/381. Respondents were informed that their participation was voluntary. They were requested to provide informed consent by clicking ‘yes’ after reviewing the informed consent note. They were assured of their confidentiality and the privacy of their information.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents

A total of 935 respondents participated in the survey. Most were females (80%), and the mean age was 36.6±9.5 years. Most were married (66.5%) and predominantly Christians (98.3%). More than a quarter of the respondents were registered nurses (28.3%). Most of the respondents were Ordinary National Diploma/Higher National Diploma (OND/HND) holders (41.2%). A greater proportion of the respondents (87.2%) earned less than ₦200,000 ($120.52) monthly and worked in government-owned facilities (83.3%). Just over half of them (54.9%) were engaged with the primary healthcare facilities. The mean years of practice was 9.15±5.8 years. Up to one third of the respondents (34.0%) had more than 10 years of working experience ( Table 1).

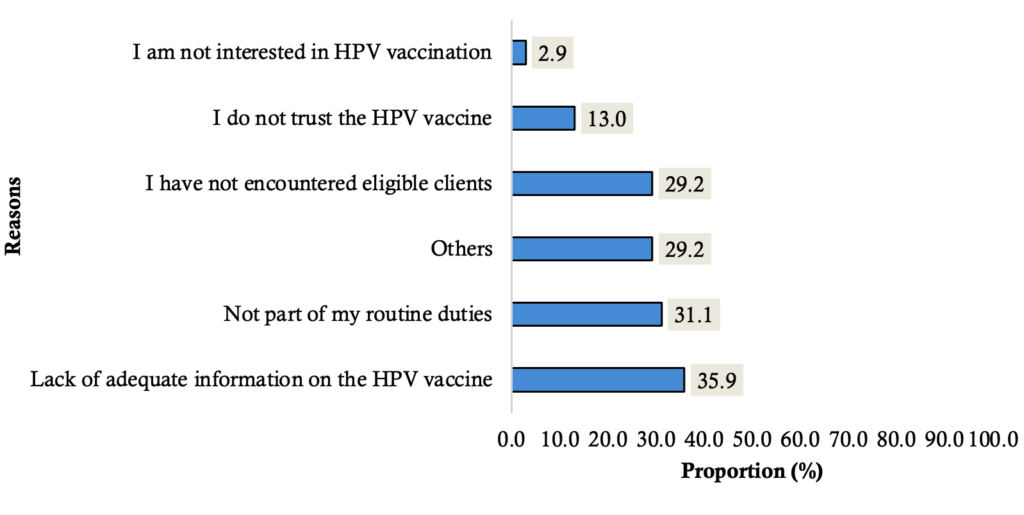

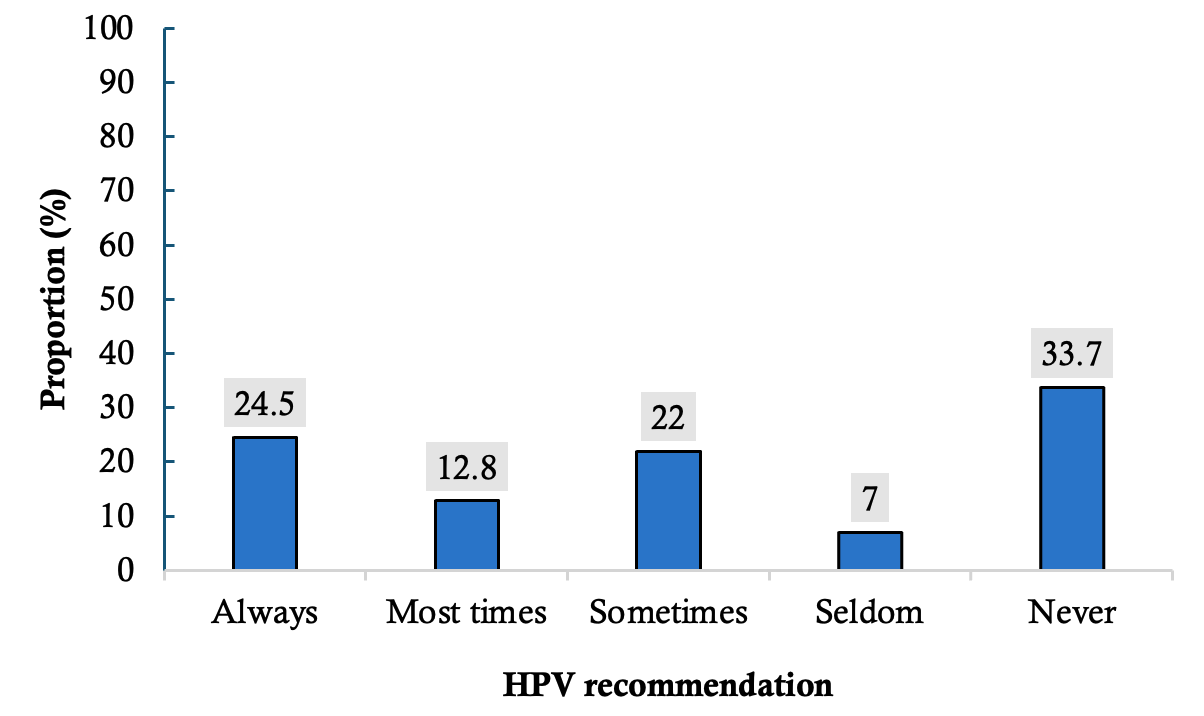

Prevalence of frequent HPV vaccine recommendations

The prevalence of frequent HPV vaccine recommendations was 37.3% (95% CI: 34.1 – 40.6). One third of the respondents had never recommended the HPV vaccine (33.7%). A smaller proportion rarely recommended the HPV vaccine (7.0%). Almost a quarter of the respondents (24.5%) always recommended the vaccine (Figure 1).

Before the implementation of the HPV vaccine in Ebonyi State, approximately half of the respondents (49.4%) had participated in at least one training for HPV vaccine implementation, with most respondents participating in the microplan training (46.3%). Good self-reported knowledge and actual knowledge were reported in 62.7% and 50.5% of the respondents, respectively. Additionally, the overall level of good attitude among the respondents was 64.6% (95% CI: 61.3 – 67.4).

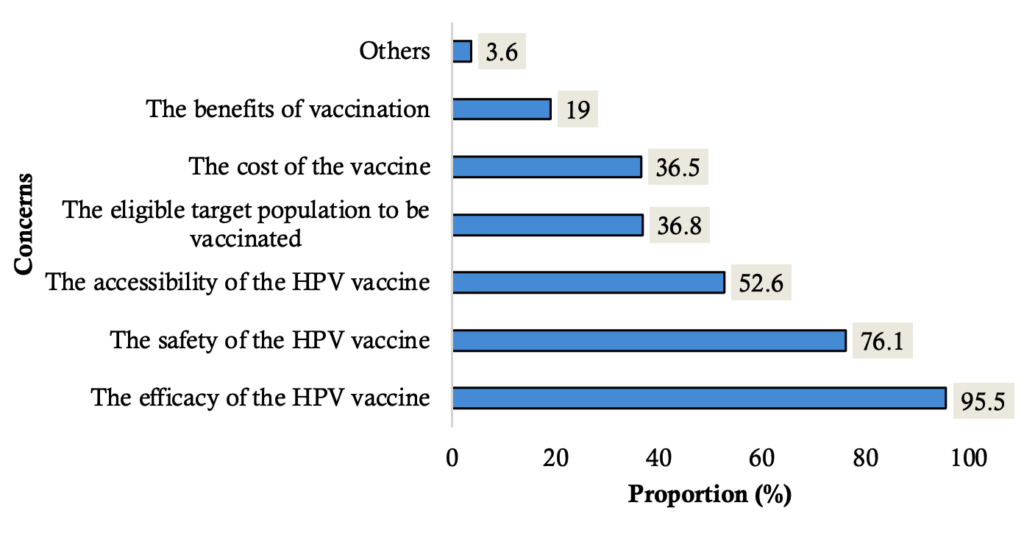

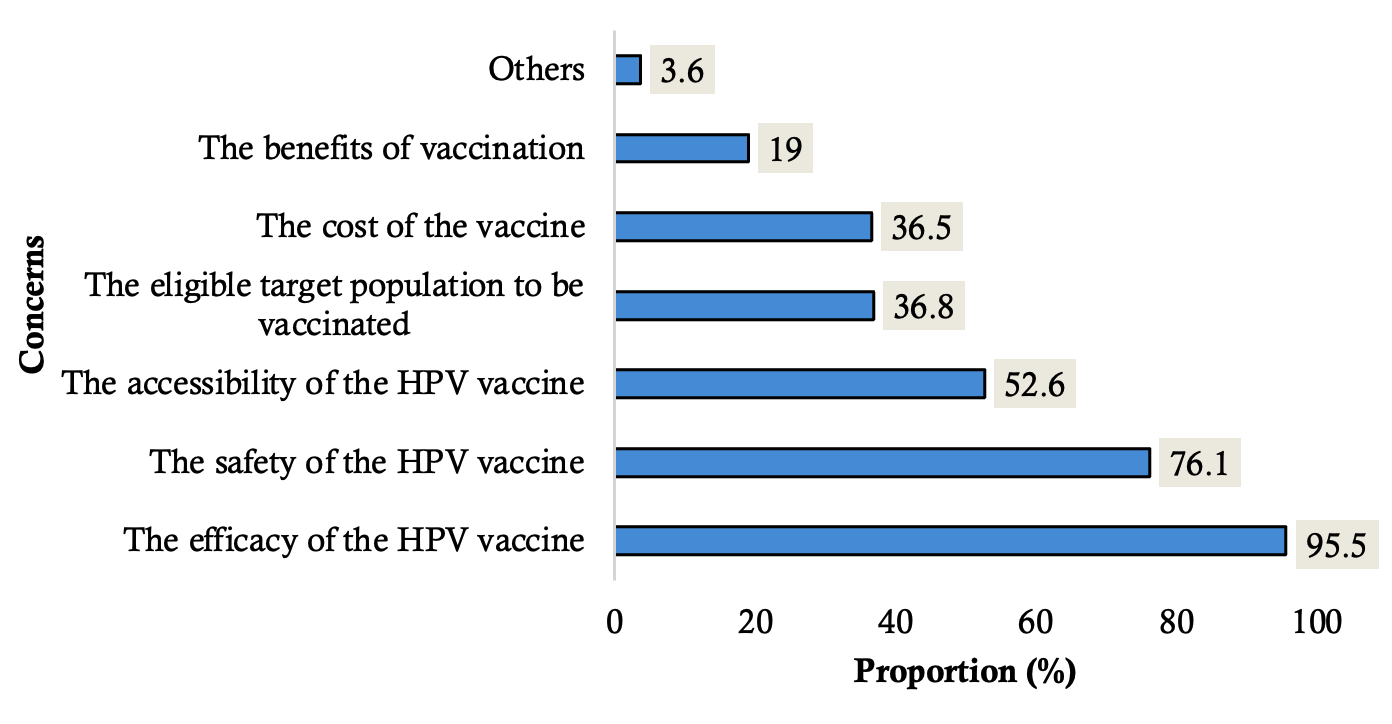

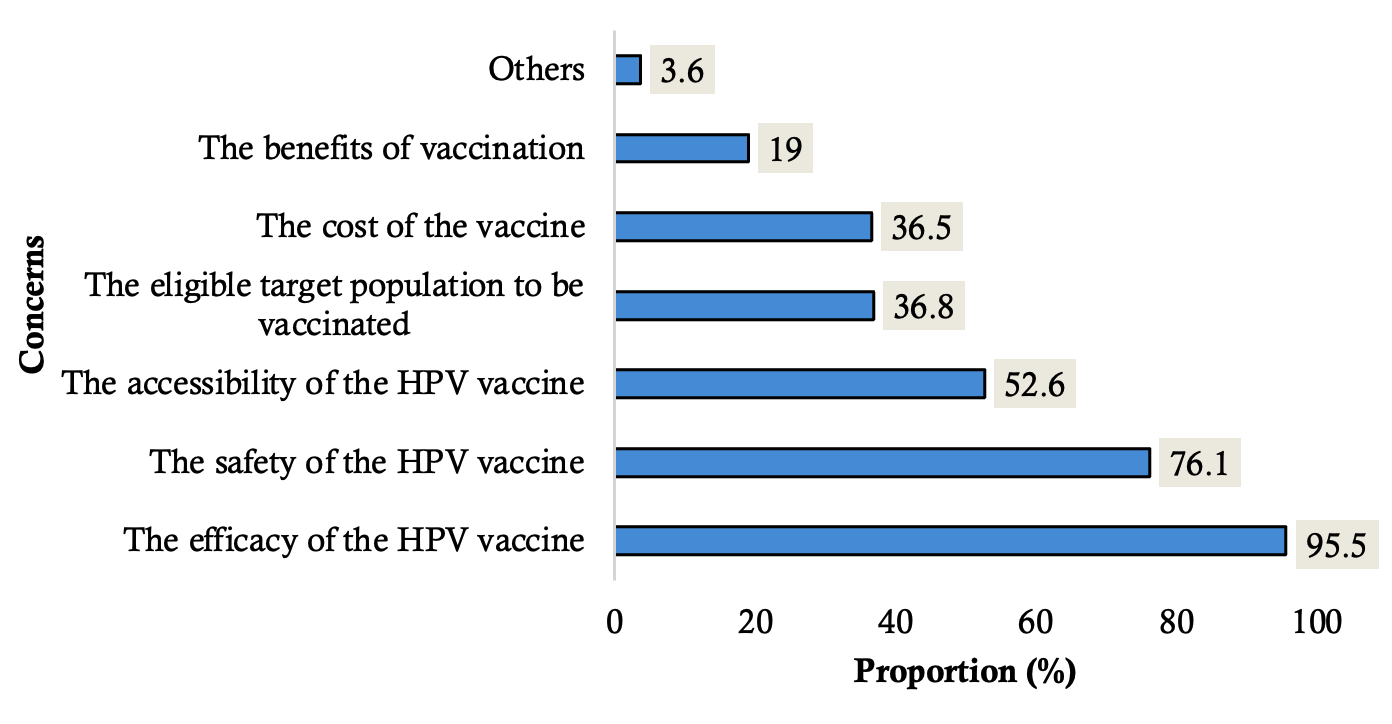

Perceived concerns of clients about the HPV vaccine

The most prevalent perceived concerns reported by the respondents included the efficacy of the HPV vaccine (95.5%) and vaccine safety (76.1%). However, the least mentioned concerns included the cost (36.5%) and the benefits of vaccination (19%, Figure 2)

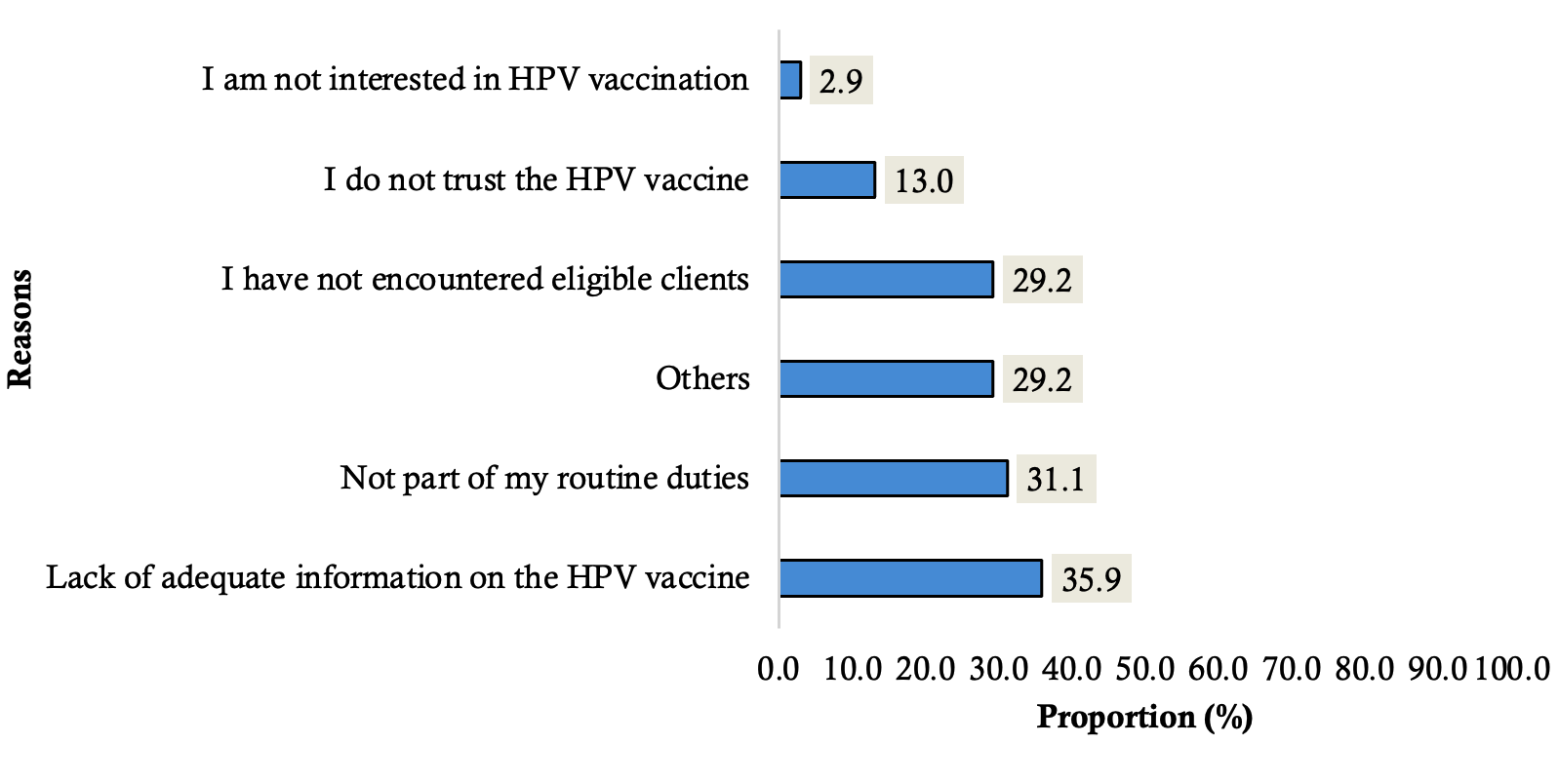

Reasons for never recommending the HPV vaccine

Among those who had never recommended the vaccines, the most frequent reasons included lack of information (35.9%) and not being part of their routine duties (31.1%). Figure 3

Predictors of HCP recommendation of HPV vaccination

Respondents of younger age (less than 40 years) were 69% less likely to recommend the HPV vaccine compared to the older respondents (COR=0.31; 95% CI: 0.24 – 0.42). Respondents with lower educational status (OND/HND) had lower odds of recommending the HPV vaccine compared to those with higher degrees (COR=0.30; 95% CI:0.22 – 0.40). Also, community health workers were less likely to recommend the vaccine compared to other health professionals (COR=0.34; 95% CI: 0.23 – 0.49). Additionally, respondents working within the primary healthcare facilities (COR=0.64; 95% CI: 0.45 – 0.90) and with 1 – 10 years of practice (COR=0.35; 95% CI: 0.26 – 0.46) were less likely to recommend the HPV vaccine compared to their counterparts. Good actual knowledge of HPV vaccination (COR=34.66; 95% CI: 22.45 – 53.52), good self-reported knowledge of HPV vaccination (COR=8.04; 95% CI: 5.61 – 11.54), and a good attitude to HPV vaccination (COR=30.67; 95% CI: 17.22 – 54.63) were positively associated with frequent recommendation of HPV vaccination. Lastly, respondents who had attended at least one training on the HPV vaccination before implementation were more likely to frequently recommend the HPV vaccine (COR=6.59; 95% CI: 4.87 – 8.93).

In multivariate analysis, the independent predictors of HPV vaccine recommendation by healthcare providers included age of less than 40 years (aOR=0.50; 95% CI: 0.28 – 0.90), lower education [(WAEC O’level; aOR = 0.06; 95% CI: 0.01–0.22) and (OND/HND; aOR = 0.31; 95% CI: 0.14–0.71)], good actual knowledge (aOR=12.38; 95% CI: 7.28 – 21.10), good self-reported knowledge (aOR=2.94; 95% CI: 1.74 – 4.96), and good attitude to the HPV vaccination (aOR=15.62; 95% CI: 7.76 – 31.44). Table 2

Discussion

This study assessed the pattern and predictors of the HPV vaccine recommendation by HCPs in Ebonyi State. Up to three out of every 10 healthcare providers frequently recommended the HPV vaccine. The predictors of frequent HPV vaccine recommendation included age, education status, knowledge and attitude of the healthcare providers to HPV vaccination.

The prevalence of frequent recommendations of the HPV vaccination reported in this study was consistent with the findings from China (30.2%) [13]. This may be attributed to comparable study populations and contextual factors. However, our finding is at variance with higher rates that have been documented in Africa (54.6%,83.2%)[14,15], Italy (77.4%) [16] and Southern China (68.1%) [17]. These studies were conducted in areas where HPV vaccination initiatives and awareness campaigns have been more extensively integrated into public health programmes, likely improving knowledge and confidence among healthcare workers. Furthermore, a lower rate of 19% was documented in a study conducted in Japan among healthcare providers, as well as 16.5% among physicians in Saudi Arabia [10,18]. The lower rates in Japan may be linked to Japan’s suspension of proactive HPV vaccine recommendations and, in Saudi Arabia, to cultural sensitivities and limited perception of HPV risk. Recommendation of vaccines (provider behaviour) is an important indicator of vaccine confidence in the general populace [12]. In this study, a few of the respondents reported receiving training before educating caregivers and the communities in their LGAs, indicating a significant gap in the preparedness of healthcare providers for effective health communication. There is a need for frequent training and regular updates on the HPV vaccination to empower the HCPs.

In this study, the younger HCPs had lower odds of recommending the HPV vaccination compared to the older HCPs. This corroborates the findings among Vietnamese healthcare providers, where older age was associated with increased willingness to recommend the HPV vaccination [19]. This finding may stem from variations in experience and confidence, with longer clinical exposure and greater familiarity with vaccination programmes, which can strengthen their advocacy compared to the younger providers. It is known that older providers are more knowledgeable about the HPV vaccination recommendations [20]. This suggests that age correlates with confidence in making recommendations. Additionally, a study in Texas observed that HCPs less than 35 years old frequently reported a lack of effective tools and information to give to patients as barriers to the recommendation of HPV vaccination [21]. These findings suggest a need for targeted educational interventions that equip healthcare providers with accurate information and effective communication skills to confidently recommend HPV vaccination to eligible girls and their caregivers.

Educational status was significantly associated with frequent recommendations for HPV vaccination in this study. This is concurrent with the findings of a study where participants with higher medical education showed a positive attitude towards vaccination [22]. People with lower education are more likely to accept misinformation [23]. Individuals with higher education are generally better informed about disease prevention, more receptive to scientific evidence, and more confident in discussing vaccination, which likely explains the consistent pattern observed across both studies. Another possible explanation is that this study included all the categories of HCPs with differences in education, professional roles, and training exposure. Higher-cadre providers such as doctors and nurses are likely more familiar with vaccination guidelines than lower-cadre or lay health workers, which may influence their knowledge and ability to recommend vaccines. Future interventions should therefore tailor training to the specific needs of each cadre.

In this current study, HCPs with good attitudes towards the HPV vaccination were more likely to frequently practice the recommendation of the HPV vaccine. This is concurrent with the findings of a study conducted in Zambia among medical doctors, where a positive correlation between attitude and practice of HPV vaccine recommendation was observed [15]. Patients trust HCPs to get reliable information on their health. Poor attitude of HCPs can lead to patients opting for other potential sources of information, which may be less accurate, leading to a wrong sense of judgement and a decrease in public trust [12]. Ineffective recommendations due to the poor attitude of healthcare providers can lead to lower HPV vaccination rates, with a rise in the incidence of cervical cancer, leading to higher healthcare costs and a strain on the healthcare system. Encouraging a positive attitude among the HCPs is essential to maintaining trust and ensuring the success of vaccination programmes.

Higher odds of actual and self-reported knowledge of HPV vaccination were associated with frequent HPV vaccine recommendations by HCPs in this study. This is similar to a finding of a systematic review, where the recommendation was positively associated with providers’ knowledge [24]. In a qualitative study conducted in Nigeria, knowledge was one of the domains with the largest frequencies of concepts regarding HPV vaccine recommendation by HCPs [25]. This is also concurrent with studies conducted in China, where having high self-reported and actual knowledge was a factor associated with high frequencies of recommendation [13,17]. Studies in Africa have observed that insufficient knowledge of the HPV vaccine affects the ability of healthcare workers (HCWs) to promote HPV vaccine uptake and the intention to recommend the vaccine, thereby reducing vaccine confidence [25,26]. With poor knowledge, HCPs may inadvertently spread misinformation about the vaccine. Ensuring HCPs are knowledgeable is critical for effective HPV vaccine promotion and uptake.

The most common reason reported in this study for never recommending the HPV vaccine was lack of information and the perception that HPV vaccine recommendation was not part of their expected duties. A similar finding was documented in a study where believing that vaccine promotion was not their duty was a notable concern for not recommending the vaccine [27]. A study cited vaccine unavailability, lack of effective communication tools, and information material as the reasons for not recommending the HPV vaccine to the eligible girls [14]. Other barriers reported included time constraints, poor delegation, and the need for training [21]. The provision of comprehensive education and training of the HCPs about the HPV vaccine is encouraged. There is also a need to provide materials such as fliers and frequently asked questions (FAQs) to help facilitate discussions with clients. Addressing each of these concerns will help the HCPs feel more equipped and motivated to recommend the HPV vaccine to their clients.

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that there is a relatively low rate of recommendation for HPV vaccination among the HCPs. Age, education status, knowledge, and attitude of HCPs to the HPV vaccination were associated with HPV vaccine recommendation by HCPs.

There is a need to reorient HCPs through the provision of regular training sessions on the national HPV vaccination guidelines, HPV-related research, and success stories from other countries. Also, designing targeted health education programmes that address identified knowledge gaps among the HCPs will empower them to frequently recommend the HPV vaccine.

The integration of HPV vaccination education and promotion into existing HIV care programmes and adolescent health services could provide an effective platform to strengthen healthcare workers’ awareness and increase HPV vaccine recommendation rates. Furthermore, these interventions should be tailored to specific sociodemographic groups for effective outcomes.

We observed some limitations in this study. Firstly, this was a cross-sectional study, so temporality could not be assessed. Secondly, we relied on self-reported data. Participants might have overreported desirable behaviours, such as recommending or supporting vaccination, or underreported undesirable ones. So, responses may have been influenced by social desirability bias, meaning reported practices may not fully reflect actual behaviour. Thirdly, there was also an increased likelihood of recall bias among the study participants. Finally, most of the study respondents were females, which may limit the external validity of the findings. To mitigate these limitations, we ensured that the research assistants were well-trained in the interviewing process, and the study sample served as a good representative of the study population. Nevertheless, this study draws its major strength from the fact that it is among the few studies to assess HCP recommendations of HPV vaccination during the HPV vaccination post-implementation period in Ebonyi State. Thus, providing baseline information for the relevant stakeholders and supporting partners in the state.

What is already known about the topic

- Healthcare providers’ (HCPs) recommendations enhance the acceptance of the HPV vaccine.

- Several barriers to HPV vaccine recommendation have been documented in studies

What this study adds

- The proportion of HCP recommendations of the HPV vaccine during the HPV vaccine post-implementation era is abysmally poor to sustain the routinization of the HPV vaccine in Ebonyi State.

- It identifies the contextual factors associated with HCP recommendations that should be addressed to achieve a successful routinization of the HPV vaccine in Ebonyi State.

Authors´ contributions

CIA: conceptualization, data collection, data analysis, writing the original draft, reviewing, editing, and finalization of the manuscript. CA, BNA, and KUK: data collection, writing the original draft, reviewing, editing, and final approval of the manuscript. NA and APB: data collection, data analysis, writing the original draft, reviewing, editing, and final approval of the manuscript. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 187 | 20.0 |

| Female | 748 | 80.0 |

| Age group (years) | ||

| 20–29 | 247 | 26.4 |

| 30–39 | 372 | 39.8 |

| 40–49 | 202 | 21.6 |

| 50–59 | 106 | 11.3 |

| ≥60 | 8 | 0.9 |

| Mean ± SD | 36.6 ± 9.5 | |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 275 | 29.4 |

| Married | 622 | 66.5 |

| Divorced/Separated | 7 | 0.7 |

| Widowed | 31 | 3.3 |

| Religion | ||

| Christianity | 919 | 98.3 |

| Islam | 10 | 1.1 |

| African Tradition | 5 | 0.5 |

| Others | 1 | 0.1 |

| Denomination (n=919) | ||

| Catholic | 393 | 42.8 |

| Orthodox | 125 | 13.6 |

| Pentecostal | 377 | 41.0 |

| Others | 24 | 2.6 |

| Cadre | ||

| Medical Doctor | 66 | 7.1 |

| Registered Nurse | 265 | 28.3 |

| Community Health worker | 175 | 18.7 |

| Community Health Extension worker | 219 | 23.4 |

| Health Assistant | 147 | 15.7 |

| Others | 63 | 6.7 |

| Highest Educational attainment | ||

| WAEC O’ level* | 176 | 18.8 |

| OND/HND* | 385 | 41.2 |

| University Degree | 325 | 34.8 |

| Post-graduate Degree | 49 | 5.2 |

| Monthly Salary (Naira ₦) | ||

| < ₦200,000 | 815 | 87.2 |

| ₦200,000 – ₦500,000 | 108 | 11.6 |

| ₦500,001 – ₦1,000,000 | 12 | 1.3 |

| Facility Ownership | ||

| Government | 779 | 83.3 |

| Private | 156 | 16.7 |

| Facility Tier | ||

| Primary | 513 | 54.9 |

| Secondary | 238 | 25.5 |

| Tertiary | 184 | 19.7 |

| Location of Practice | ||

| Ebonyi Central | 203 | 21.7 |

| Ebonyi North | 472 | 50.5 |

| Ebonyi South | 260 | 27.8 |

| Years of Practice | ||

| <5 | 207 | 22.1 |

| 5–10 | 410 | 43.9 |

| >10 | 318 | 34.0 |

| Variables | HPV vaccine recommendation | COR (95% CI) | P value | aOR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequent (%) 349 (37.3) | Infrequent (%) 586 (62.7) | |||||

| Age group | ||||||

| <40 | 174 (28.1) | 445 (71.9) | 0.31 (0.24–0.42) | <0.001 | 0.50 (0.28–0.90) | 0.020 |

| ≥40 | 175 (55.4) | 141 (44.6) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 70 (37.4) | 117 (62.6) | 1.01 (0.72–1.40) | 0.973 | – | – |

| Female | 279 (37.3) | 469 (62.7) | 1 | – | – | |

| Education status | ||||||

| WAEC O’ Level | 53 (30.1) | 123 (69.9) | 0.77 (0.52–1.14) | 0.194 | 0.06 (0.01–0.22) | <0.001 |

| OND/HND | 203 (52.7) | 182 (47.3) | 0.30 (0.22–0.40) | <0.001 | 0.31 (0.14–0.71) | 0.005 |

| Above Diploma | 93 (24.9) | 281 (75.1) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 92 (33.5) | 183 (66.5) | 1.16 (0.57–2.35) | 0.679 | – | – |

| Married | 243 (39.1) | 379 (60.9) | 0.91 (0.46–1.79) | 0.785 | – | – |

| Others | 14 (36.8) | 24 (63.2) | 1 | – | – | |

| Denomination | ||||||

| Catholic | 122 (31.0) | 271 (69.0) | 3.70 (1.58–8.69) | 0.003 | 3.32 (0.80–13.80) | 0.099 |

| Orthodox | 23 (18.4) | 102 (81.6) | 7.39 (2.88–19.00) | <0.001 | 3.60 (0.77–16.85) | 0.105 |

| Pentecostal | 188 (49.9) | 189 (50.1) | 1.67 (0.72–3.92) | 0.234 | 1.71 (0.42–7.04) | 0.456 |

| Others | 15 (62.5) | 9 (37.5) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Cadre | ||||||

| Clinical staff | 106 (32.0) | 225 (68.0) | 0.68 (0.46–1.01) | 0.054 | 0.38 (0.10–1.43) | 0.152 |

| Community Health workers | 192 (48.7) | 202 (51.3) | 0.34 (0.23–0.49) | <0.001 | 0.92 (0.28–2.99) | 0.884 |

| Other health professionals | 51 (24.3) | 159 (75.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Facility tier | ||||||

| Primary | 225 (43.9) | 288 (56.1) | 0.64 (0.45–0.90) | 0.012 | 0.78 (0.37–1.66) | 0.521 |

| Secondary | 63 (26.5) | 175 (73.5) | 1.38 (0.90–2.10) | 0.136 | 1.35 (0.59–3.05) | 0.475 |

| Tertiary | 61 (33.2) | 123 (66.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Years of practice | ||||||

| 1–10 years | 178 (28.8) | 439 (71.2) | 0.35 (0.26–0.46) | <0.001 | 0.63 (0.36–1.12) | 0.114 |

| Above 10 years | 171 (53.8) | 147 (46.2) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Facility ownership | ||||||

| Government | 283 (36.3) | 496 (63.7) | 1.29 (0.91–1.82) | 0.159 | 1.72 (0.87–3.40) | 0.117 |

| Private | 66 (42.3) | 60 (57.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Actual knowledge | ||||||

| Good | 322 (68.2) | 150 (31.8) | 34.66 (22.45–53.52) | <0.001 | 12.38 (7.28–21.10) | <0.001 |

| Poor | 27 (5.8) | 436 (94.2) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Self knowledge | ||||||

| Good | 307 (52.4) | 279 (47.6) | 8.04 (5.61–11.54) | <0.001 | 2.94 (1.74–4.96) | <0.001 |

| Poor | 42 (12.0) | 307 (88.0) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Attitude | ||||||

| Good | 336 (55.6) | 268 (44.4) | 30.67 (17.22–54.63) | <0.001 | 15.62 (7.76–31.44) | <0.001 |

| Poor | 13 (3.9) | 318 (96.1) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Training on HPV vaccination attended | ||||||

| Yes | 267 (57.8) | 195 (42.2) | 6.59 (4.87–8.93) | <0.001 | 1.28 (0.69–2.40) | 0.437 |

| No | 80 (17.2) | 385 (82.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

References

- World Health Organization. Weekly epidemiological record [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; [cited 2024 Feb 15]. Available from: https://www.hpvcenter.se/human_reference_clones/

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2024 May-Jun [cited 2025 Dec 2];74(3):229-263. Available from: https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/caac.21834 doi: 10.3322/caac.21834

- ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer. Nigeria: Human Papillomavirus and Related Cancers, Fact Sheet 2023 [Internet]. Barcelona (Spain): ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer; 2023 Mar 10 [cited 2025 Dec 2]. 2 p. Available from: https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/NGA_FS.pdf

- World Health Organization. Cervical Cancer Elimination Initiative [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 19]. Available from: https://www.who.int/initiatives/cervical-cancer-elimination-initiative

- Egbon M, Ojo T, Aliyu A, Bagudu ZS. Challenges and lessons from a school-based human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination program for adolescent girls in a rural Nigerian community. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2022 Aug 24 [cited 2025 Dec 2];22(1):1611. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-022-13975-3 doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13975-3

- Azuogu BN, Umeokonkwo CD, Azuogu VC, Onwe OE, Okedo-Alex IN, Egbuji CC. Appraisal of willingness to vaccinate daughters with human papilloma virus vaccine and cervical cancer screening uptake among mothers of adolescent students in Abakaliki, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract [Internet]. 2019 Sep [cited 2025 Dec 2];22(9):1286-1291. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/10.4103/njcp.njcp_452_18 doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_452_18

- Isara AR, Osayi N. Knowledge of human papillomavirus and uptake of its vaccine among female undergraduate students of Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma, Nigeria. J Com Med Prim Health Care [Internet]. 2021 Mar 22 [cited 2025 Dec 2];33(1):64-75. Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/jcmphc/article/view/204877 doi: 10.4314/jcmphc.v33i1.6

- Ambali RT, John-Akinola YO, Oluwasanu MM. In-depth interviews on acceptability and concerns for human papilloma virus vaccine uptake among mothers of adolescent girls in community settings in Ibadan, Nigeria. J Cancer Educ [Internet]. 2022 Jun [cited 2025 Dec 2];37(3):748-754. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s13187-020-01876-1 doi: 10.1007/s13187-020-01876-1

- Katsuta T, Moser CA, Offit PA, Feemster KA. Japanese physicians’ attitudes and intentions regarding human papillomavirus vaccine compared with other adolescent vaccines. Papillomavirus Res [Internet]. 2019 Jun [cited 2025 Dec 2];7:193-200. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2405852118301204 doi: 10.1016/j.pvr.2019.04.013

- Nishioka H, Onishi T, Kitano T, Takeyama M, Imakita N, Kasahara K, Kawaguchi R, Masaki JA, Nogami K. A survey of healthcare workers’ recommendations about human papillomavirus vaccination. Clin Exp Vaccine Res [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Dec 2];11(2):149. Available from: https://ecevr.org/DOIx.php?id=10.7774/cevr.2022.11.2.149 doi: 10.7774/cevr.2022.11.2.149

- Feemster KA, Middleton M, Fiks AG, Winters S, Kinsman SB, Kahn JA. Does intention to recommend HPV vaccines impact HPV vaccination rates? Hum Vaccin Immunother [Internet]. 2014 Sep 2 [cited 2025 Dec 2];10(9):2519-2526. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.4161/21645515.2014.969613 doi: 10.4161/21645515.2014.969613

- Vorsters A, Bonanni P, Maltezou HC, Yarwood J, Brewer NT, Bosch FX, Hanley S, Cameron R, Franco EL, Arbyn M, Muñoz N, Kojouharova M, Pattyn J, Baay M, Karafillakis E, Van Damme P. The role of healthcare providers in HPV vaccination programs – A meeting report. Papillomavirus Res [Internet]. 2019 Dec [cited 2025 Dec 2];8:100183. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2405852119300679 doi: 10.1016/j.pvr.2019.100183

- Mao Y, Zhao Y, Zhang L, Li J, Abdullah AS, Zheng P, Wang F. Frequency of health care provider recommendations for HPV vaccination: a survey in three large cities in China. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2023 Jul 11 [cited 2025 Dec 2];11:1203610. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1203610/full doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1203610

- Fokom Domgue J, Dille I, Kapambwe S, Yu R, Gnangnon F, Chinula L, Murenzi G, Mbatani N, Pande M, Sidibe F, Kamgno J, Traore B, El Fazazi H, Diop M, Tebeu PM, Diomande MI, Lecuru F, Adewole I, Plante M, Basu P, Dangou JM, Shete S. HPV vaccination in Africa in the COVID-19 era: a cross-sectional survey of healthcare providers’ knowledge, training, and recommendation practices. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2024 Jan 17 [cited 2025 Dec 2];12:1343064. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1343064/full doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1343064

- Lubeya MK, Nyirenda JCZ, Kabwe JC, Mukosha M. Knowledge, attitudes and practices towards human papillomavirus vaccination among medical doctors at a tertiary hospital: a cross sectional study. Cancer Control [Internet]. 2022 Nov [cited 2025 Dec 2];29:10732748221132646. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/10732748221132646 doi: 10.1177/10732748221132646

- Napolitano F, Navaro M, Vezzosi L, Santagati G, Angelillo IF. Primary care pediatricians’ attitudes and practice towards HPV vaccination: a nationwide survey in Italy. PLoS One [Internet]. 2018 Mar 29 [cited 2025 Dec 2];13(3):e0194920. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194920 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194920

- Chen S, Mei C, Huang W, Liu P, Wang H, Lin W, Yuan S, Wang Y. Human papillomavirus vaccination related knowledge, and recommendations among healthcare providers in Southern China: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Womens Health [Internet]. 2022 Dec [cited 2025 Dec 2];22(1):169. Available from: https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12905-022-01728-8 doi: 10.1186/s12905-022-01728-8

- Almughais ES, Alfarhan A, Salam M. Awareness of primary health care physicians about human papilloma virus infection and its vaccination: a cross-sectional survey from multiple clinics in Saudi Arabia. Infect Drug Resist [Internet]. 2018 Nov 15 [cited 2025 Dec 2];11:2257-2267. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.2147/IDR.S179642 doi: 10.2147/IDR.S179642

- Asiedu GB, Radecki Breitkopf C, Kremers WK, Ngo QV, Nguyen NV, Barenberg BJ, Tran VD, Dinh TA. Vietnamese health care providers’ preferences regarding recommendation of HPV vaccines. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev [Internet]. 2015 Jul 13 [cited 2025 Dec 2];16(12):4895-4900. Available from: https://koreascience.or.kr/journal/view.jsp?kj=POCPA9&py=2015&vnc=v16n12&sp=4895 doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.12.4895

- Warner EL, Ding Q, Pappas L, Bodson J, Fowler B, Mooney R, Kirchhoff AC, Kepka D. Health care providers’ knowledge of HPV vaccination, barriers, and strategies in a state with low HPV vaccine receipt: mixed-methods study. JMIR Cancer [Internet]. 2017 Aug 11 [cited 2025 Dec 2];3(2):e12. Available from: http://cancer.jmir.org/2017/2/e12/ doi: 10.2196/cancer.7345

- Chido-Amajuoyi OG, Osaghae I, Onyeaka HK, Shete S. Barriers to the assessment and recommendation of HPV vaccination among healthcare providers in Texas. Vaccine X [Internet]. 2024 Jun [cited 2025 Dec 2];18:100471. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2590136224000445 doi: 10.1016/j.jvacx.2024.100471

- Kuznetsova OY, Khalimov YS, Moiseeva IE, Turusheva AV. Vaccination adherence and level of knowledge: Is there a relationship? Russian Family Doctor [Internet]. 2023 Jul 20 [cited 2025 Dec 2];27(2):47-53. Available from: https://journals.eco-vector.com/RFD/article/view/501781 doi: 10.17816/RFD501781

- Hwang Y, Jeong SH. Education-based gap in misinformation acceptance: does the gap increase as misinformation exposure increases? Communication Research [Internet]. 2023 Mar [cited 2025 Dec 2];50(2):157-178. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00936502221121509 doi: 10.1177/00936502221121509

- Lin C, Mullen J, Smith D, Kotarba M, Kaplan SJ, Tu P. Healthcare providers’ vaccine perceptions, hesitancy, and recommendation to patients: a systematic review. Vaccines (Basel) [Internet]. 2021 Jul 1 [cited 2025 Dec 2];9(7):713. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/9/7/713 doi: 10.3390/vaccines9070713

- Balogun FM, Omotade OO. Facilitators and barriers of healthcare workers’ recommendation of HPV vaccine for adolescents in Nigeria: views through the lens of theoretical domains framework. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2022 Dec [cited 2025 Dec 2];22(1):824. Available from: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-022-08224-7 doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08224-7

- Rujumba J, Akugizibwe M, Basta NE, Banura C. Why don’t adolescent girls in a rural Uganda district initiate or complete routine 2-dose HPV vaccine series: Perspectives of adolescent girls, their caregivers, healthcare workers, community health workers and teachers. PLoS One [Internet]. 2021 Jun 29 [cited 2025 Dec 2];16(6):e0253735. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253735 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253735

- Song D, Liu P, Wu D, Zhao F, Wang Y, Zhang Y. Knowledge and attitudes towards human papillomavirus vaccination (HPV) among healthcare providers involved in the governmental free HPV vaccination program in Shenzhen, Southern China. Vaccines (Basel) [Internet]. 2023 May 18 [cited 2025 Dec 2];11(5):997. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/11/5/997 doi: 10.3390/vaccines11050997