Research | Open Access | Volume 8 (4): Article 100 | Published: 03 Dec 2025

Factors associated with mortality in patients diagnosed with COVID-19 in the Manzini Region, Eswatini, 2020-2021

Menu, Tables and Figures

Navigate this article

Tables

| Table 1. Factors associated with mortality among patients with COVID-19 in the Manzini Region, Eswatini, March 2020–August 2021. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Dead N=336 n (%) | Survived N=15124 n (%) | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

| Crude Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |||||

| Year | ||||||||

| 2020 | 102 (30.36) | 4225 (27.94) | Reference | |||||

| 2021 | 234 (69.64) | 10899 (72.06) | 0.89 (0.70–1.13) | 0.32 | 15.26 (6.60–35.24) | <0.001 | ||

| Age group (Years) | ||||||||

| 0–19 | 7 (2.08) | 1470 (9.72) | Reference | |||||

| 20–34 | 8 (2.38) | 4275 (28.27) | 0.39 (0.14–1.09) | 0.07 | 0.50 (0.14–1.74) | 0.28 | ||

| 35–49 | 51 (15.18) | 5140 (33.99) | 2.08 (0.94–4.60) | 0.07 | 2.48 (0.87–7.01) | 0.09 | ||

| 50–59 | 55 (16.37) | 1873 (12.38) | 6.17 (2.80–13.58) | <0.001 | 8.12 (2.81–23.49) | <0.001 | ||

| ≥60 | 215 (63.99) | 2366 (15.64) | 19.08 (8.96–40.62) | <0.001 | 9.27 (3.12–25.92) | <0.001 | ||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 177 (52.68) | 6851 (45.30) | Reference | |||||

| Female | 159 (47.32) | 8273 (54.70) | 0.74 (0.60–0.92) | 0.01 | 0.80 (0.55–1.15) | 0.23 | ||

| Hypertension | ||||||||

| No | 144 (42.86) | 258 (1.71) | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 128 (38.10) | 116 (0.77) | 1.98 (1.43–2.73) | <0.001 | 3.57 (2.01–6.36) | <0.001 | ||

| Unknown | 64 (19.05) | 14750 (97.53) | 0.01 (0.01–0.01) | 0.00 | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 | ||

| Diabetes Mellitus | ||||||||

| No | 205 (61.01) | 280 (1.85) | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 67 (19.94) | 94 (0.62) | 0.97 (0.68–1.40) | 0.89 | 0.35 (0.18–0.71) | <0.001 | ||

| Unknown | 64 (19.05) | 14750 (97.53) | 0.01 (0.01–0.01) | <0.001 | Omitted | |||

| Obesity | ||||||||

| No | 288 (85.71) | 15079 (99.70) | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 48 (14.29) | 45 (0.30) | 55.84 (36.58–85.26) | <0.001 | 1.06 (0.46–2.45) | 0.89 | ||

| HIV | ||||||||

| No | 255 (75.89) | 353 (2.33) | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 17 (5.06) | 21 (0.14) | 1.12 (0.58–2.17) | 0.74 | 0.47 (0.12–1.87) | 0.28 | ||

| Unknown | 64 (19.05) | 14750 (97.53) | 0.01 (0.01–0.01) | <0.001 | Omitted | |||

| Hospitalization | ||||||||

| No | 250 (74.40) | 14247 (94.20) | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 86 (25.60) | 877 (5.80) | 5.59 (4.33–7.21) | <0.001 | 1.35 (0.83–2.20) | 0.22 | ||

| Severity at Diagnosis | ||||||||

| Asymptomatic | 13 (3.87) | 3038 (20.09) | Reference | |||||

| Mild Disease | 123 (36.61) | 10538 (69.68) | 2.73 (1.54–4.84) | <0.001 | 5.89 (2.94–11.80) | <0.001 | ||

| Moderate Disease | 50 (14.88) | 1341 (8.87) | 8.71 (4.72–16.09) | <0.001 | 12.67 (5.54–29.01) | <0.001 | ||

| Severe Disease | 150 (44.64) | 207 (1.37) | 169.34 (94.45–303.64) | <0.001 | 123.71 (53.44–286.38) | <0.001 | ||

Table 1. Factors associated with mortality among patients with COVID-19 in the Manzini Region, Eswatini, March 2020–August 2021.

Figures

Keywords

- COVID-19

- COVID-19 mortality

- Risk factors

- Disease severity

Sincobile Victory Mavundla1,2,3,&, Vusie Lokotfwako3, Lazarus Kuonza1, Alfred Musekiwa1, Masingita Makamu1, Khuliso Ravhuhali1

1South African Field Epidemiology Training Programme, National Institute for Communicable Diseases, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2University of Pretoria, School of Health Systems and Public Health, Pretoria, South Africa, 3Eswatini Ministry of Health, Epidemiology and Disease Control Unit, Eswatini

&Corresponding author: Sincobile Victory Mavundla, South African Field Epidemiology Training Programme, National Institute for Communicable Diseases, Johannesburg, South Africa, Email: msincobile2020@gmail.com, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-0861-359X

Received: 23 Jun 2025, Accepted: 02 Dec 2025, Published: 03 Dec 2025

Domain: Field Epidemiology, COVID Pandemic

Keywords: COVID-19, COVID-19 mortality, risk factors, disease severity

©Sincobile Victory Mavundla et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Sincobile Victory Mavundla et al., Factors associated with mortality in patients diagnosed with COVID-19 in the Manzini Region, Eswatini, 2020-2021. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8(4):100. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00147

Abstract

Introduction: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) emerged in late 2019 and rapidly evolved into a global public health crisis. After more than 118,000 cases in 114 countries and 4,291 mortalities were reported, the WHO declared COVID-19 a worldwide pandemic on 11 March 2020. This study aims to determine demographic and clinical factors associated with COVID-19 case fatality among patients diagnosed in the Manzini Region, Eswatini, between March 2020 and August 2021.

Methods: This retrospective cross-sectional study was based on an analysis of secondary data for patients with a positive diagnosis of COVID-19 in the Manzini region who had an outcome of either recovery or death. It then excluded all suspected cases that were not confirmed by laboratory results. A COVID-19 mortality was defined as a death resulting from a clinically compatible illness in a confirmed COVID-19 case. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise demographic, clinical characteristics. The Pearson chi-square test was used to assess differences in categorical variables, and finally used logistic regression was used to investigate factors associated with COVID-19 mortality.

Results: After excluding 189 medical records, 15,124 cases and 336 COVID-19 mortalities were analyzed. Most of the participants were Females (54.5%), and the mortality rate in patients with SARS due to COVID-19 was 2.2%. Multivariate logistic regression identified the Year 2021 as the strongest independent predictor of mortality, increasing the odds of death over 15 times compared to 2020 (AOR 15.26, 95% CI: 6.60–35.24). Advanced age was also strongly associated with fatality, with patients aged ≥60 years (AOR 9.27, 95% CI: 3.12–25.92) and 50–59 years (AOR 8.12, 95% CI: 2.81–23.49) showing markedly higher odds of death compared with younger adults. Risk increased significantly with disease severity, ranging from mild (AOR 5.89, 95% CI: 2.94–11.80) and moderate (AOR 12.67, 95% CI: 5.54–29.01) to severe disease (AOR 123.71, 95% CI: 53.44–286.38). Hypertension also remained a significant risk factor (AOR 3.57, 95% CI: 2.01–6.36). Notably, Diabetes Mellitus appeared to be a protective factor (AOR 0.35, 95% CI: 0.18–0.71).

Conclusion: Age, severity, and hypertension were confirmed risks. Crucially, the protective factor of diabetes suggests effective local prioritization and early management of high-risk patients during the pandemic.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) emerged in late 2019 and rapidly evolved into a global public health crisis [1]. On 31 January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) Director-General declared the novel coronavirus outbreak a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) [2, 3]. Later, it was designated SARS-Cov-2 [2]. On 11 February 2020, the WHO announced that the diseases caused by the novel coronavirus will be named Coronavirus Diseases 2019, abbreviated COVID-19 [2]. After more than 118,000 cases in 114 countries and 4,291 mortalities were reported, the WHO declared COVID-19 a worldwide pandemic on 11 March 2020[2]. By 2021, most countries had experienced multiple waves of infection with varying case fatality rates (CFRs) [4-6]. While high-income countries initially recorded large case numbers, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) soon faced increasing disease burden under very different health system conditions[7, 8] . Factors such as delayed testing, underreporting, and limited access to intensive care services likely contributed to differences in reported mortality and survival outcomes across settings [9-12].

In LMICs, diagnostic delays were common during the early pandemic phase due to limited laboratory capacity, shortages of reagents, and dependence on centralised testing [6]. Many infections went undetected or were confirmed only after clinical deterioration, leading to underestimation of incidence and overestimation of case fatality rates [10, 13, 14]. In several sub-Saharan African countries, weak surveillance systems and incomplete death registration further compounded underreporting, masking the true impact of the pandemic [6, 15, 16].

Health system constraints also played a key role in shaping outcomes [16]. Limited intensive care unit (ICU) capacity, shortages of oxygen and ventilators, and inadequate human resources restricted the ability of LMIC health systems to manage severe COVID-19 cases effectively [7, 6, 17, 18]. For example, Early assessments in thirteen academic medical centers in the United States and 48 countries in Africa showed that fewer than 62% of hospitals had functional ICU beds available for COVID-19 care during peak periods [19, 20]. As a result, hospital survival rates in many African countries ranged between 52–96%, with mortality rates among hospitalized patients reported between 4% and 48% [21, 22]. Studies in South Africa, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and a multi-country analysis of the WHO African Region consistently identified older age, male sex, and comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, and HIV as major predictors of death, underscoring how non-communicable diseases amplified COVID-19 severity in resource-limited settings [23-27].

Eswatini experienced its first confirmed COVID-19 case in March 2020. By the end of 2021, the country had recorded over 447504 confirmed infections and approximately 1248 mortalities [28]. The Manzini region, the country’s commercial and industrial hub, experienced the highest COVID-19 burden in Eswatini [28, 29]. Manzini has the highest population density in the country, second, the region hosts Matsapha, Eswatini’s main industrial and transportation center, characterized by high population mobility and cross-border movement with South Africa [29, 30]. Third, a large proportion of Manzini’s residents live in peri-urban areas with limited access to water and sanitation, creating challenges for infection prevention and control [29]. Consequently, Manzini represented the most severe epidemic context in the country, and factors driving mortality there are likely to mirror those in other high-burden LMIC settings [28].

While international studies have documented predictors of COVID-19 case fatality and/or mortality, including advanced age and pre-existing conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and chronic respiratory or cardiovascular disease, evidence from Eswatini remains limited [6, 15, 30, 31]. To effectively inform future public health strategies and resource allocation in Eswatini, it is vital to understand the determinants of mortality in this region. Identifying the population subgroups disproportionately affected by COVID-19 mortality is particularly important in resource-limited settings where targeted interventions are essential [6,8,15,19,32]. Characterizing these factors in Manzini would enable evidence-based allocation of scarce resources such as oxygen supplies, ICU beds, and therapeutics, and guide public health messaging to encourage timely healthcare seeking. Moreover, findings from Manzini could provide insights applicable to other resource-constrained contexts in sub-Saharan Africa facing similar dual burdens of infectious and non-communicable diseases. This study aims to determine demographic and clinical factors associated with COVID-19 case fatality among patients diagnosed in the Manzini Region, Eswatini, between March 2020 and August 2021.

Methods

Study design and setting

The study adopted a cross-sectional study design and used routinely collected data from 14 March 2020 to 31 August 2021 on patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in the Manzini Region, Eswatini. The study was conducted in Manzini, one of the four administrative regions for Eswatini (formerly known as Swaziland), found in the center west of the country. It has an area of 4093.59 km2, and the total population of Eswatini is about 1.148 million (2019 estimates). The region is both rural and urban, and the main city in the region is Manzini City, which is densely populated due to migration for several reasons, including employment and commercial purposes[15]. It has one hundred and twenty-three health facilities, including four hospitals (with in-patient services), two public health units (equivalent to health centres), and one hundred and seventeen primary health clinics. At the peak of COVID-19, all facilities provided COVID-19 services and there was one newly identified COVID-19 centre that was prepared for patients to help relieve the load from the admitting facilities in the country. Seven provided in-patient services while 50 provided outpatient services.

Data source

The study utilised COVID-19 case data, which was collected through routine surveillance systems, including the Client Management Information System (CMIS), Health Management Information System (HMIS), Laboratory Management Information System (LMIS), and the Immediate Disease Notification System (IDNS). The CMIS and HMIS systems are data collection systems in facilities, while the LMIS collects data from laboratory facility level and transmits it to the national level. The IDNS is real real-time reporting platform that captures notifiable disease data from health facilities at the national level. The study included all patients with a positive diagnosis of COVID-19 in the Manzini region who had an outcome of either recovery or death. It then excluded all suspected cases that were not confirmed by laboratory results.

Study population

Manzini has a total population of 351,083 people, of which 33.5% (approximately 117,601) is the rural population as of the AfriGIS Analysis Report by UNICEF dated 13/06/2024 [20]. The study population included records of confirmed cases of COVID-19 in all people with a positive diagnosis, including mortalities of COVID-19 from the Manzini region during the period from 14 March 2020 to 30 August 2021. It excluded suspected cases that were not confirmed by laboratory results, patients who were confirmed in the Manzini Region facilities but reside in other regions, patients who were hospitalised and tested positive but were not reported for case management.

Variables

COVID-19 mortality, as the main outcome of this study, was defined as someone who had a positive molecular (PCR) or antigen test for COVID-19, who died without fully recovering from COVID-19 [21]. Independent variables considered for the study included demographic variables (age, gender) and clinical variables (comorbiditieshypertension, diabetes, and presence of symptoms: symptomatic, asymptomatic) which were self-reported. The variables were binary (yes/no) indicating the presence or absence of the disease and unknown where there was no definite response. Disease severity at diagnosis: Classified based on the patient’s symptoms and clinical signs upon diagnosis, referencing national treatment guidelines. Mild: Non-pneumonia symptoms (e.g., fever, cough, fatigue) and no signs of hypoxia. Moderate: Evidence of pneumonia (e.g., fever, respiratory symptoms) but with SpO2 ≥94% on room air. Severe: Requires supplemental oxygen (tachypnea, respiratory distress) with SpO2 <94% on room air or requiring intensive care. This classification was determined by the attending clinician and extracted from the clinical record. Hospitalization: Defined as any admission to a public or private health facility for the management of a confirmed COVID-19 infection. This was extracted from the clinical record. Comorbidities (e.g., Hypertension, Diabetes, Asthma): Defined as any pre-existing chronic condition noted on the patient’s admission or surveillance form. For all patients, these conditions were classified as ‘Yes/No’ and were sourced from either a self-report documented upon admission or prior medical history noted in the clinical file.

Data management and analysis

Data cleaning and de-identification were done before analyses using STATA version 15 (StataCorp. College Station, TX, USA). Data was received and managed in MS Excel before being exported to STATA. Data analysis was performed using STATA version 15 (StataCorp, USA). Missing data was excluded in this study. The variables with missing values were primarily related to patient comorbidities and clinical presentation at admission. The missingness of these records was considered to be Missing At Random (MAR), as the data were incomplete due to factors such as incomplete chart entries or administrative omissions, which were not directly related to the study’s outcome. Due to the minimal percentage of missing data, a complete case analysis was performed, where records with missing values for key variables were excluded from the final analysis. This approach was deemed appropriate to avoid the potential biases associated with imputation methods on a small subset of the total data.

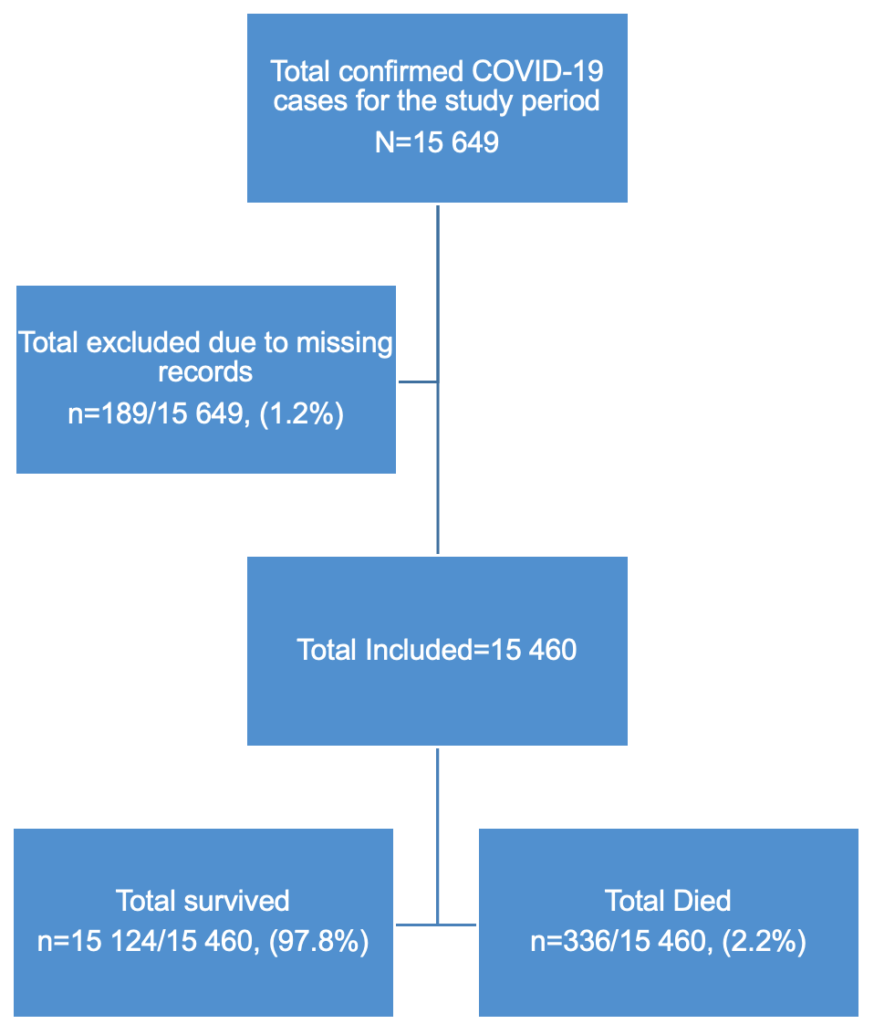

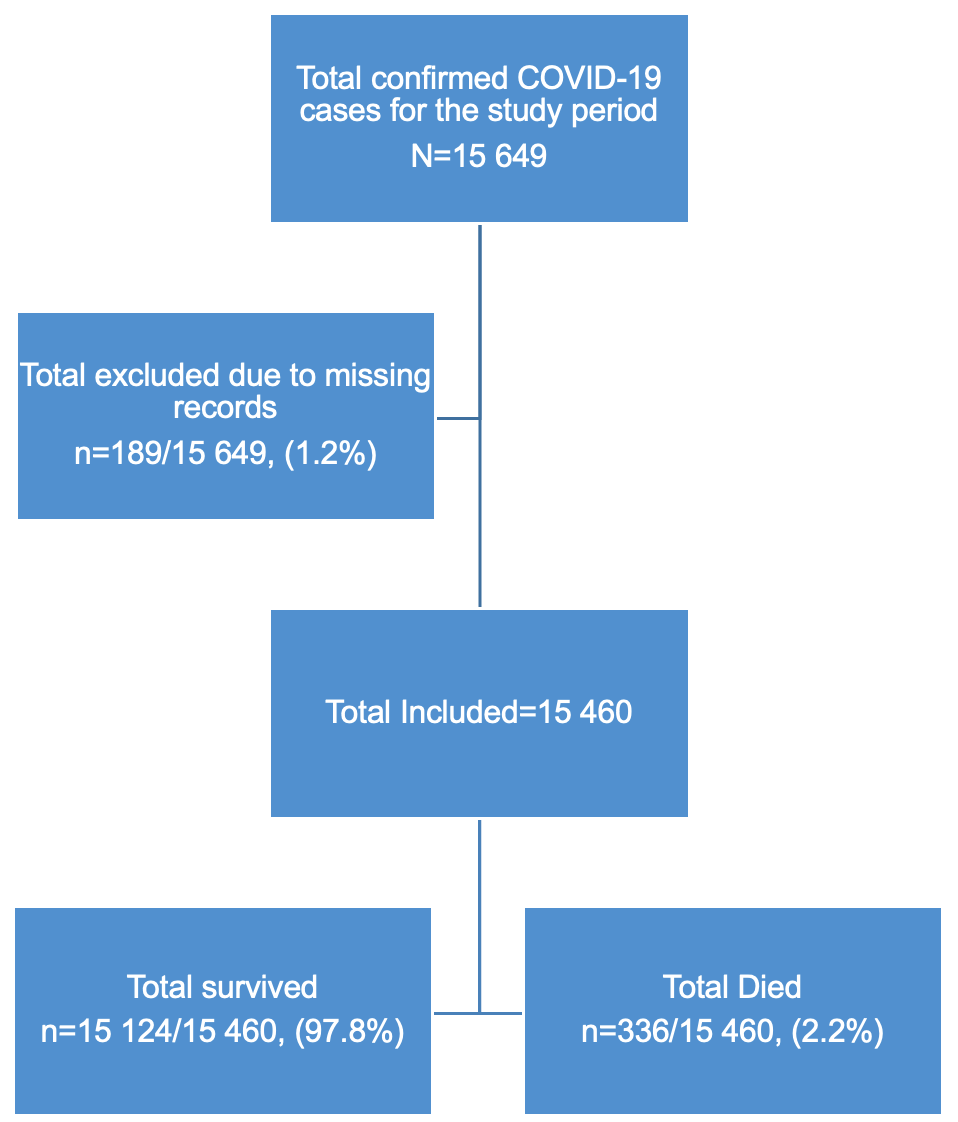

This study initially had 15,649 cases, we dropped 189 due to missing records/incomplete data to give a final sample of 15,460 COVID-19 confirmed cases (Figure 1). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics. For continuous variables, medians with interquartile ranges [IQRs] and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated, while categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. The primary outcome variable was in-hospital mortality, a dichotomous variable (dead/alive).

The choice of statistical analysis was driven by the nature of the outcome variable and the aim of the study, which was to determine the characteristics and factors associated with mortality among COVID-19 patients in the Manzini Region in Eswatini from March 2020- August 2021. We used the chi-square test to determine statistical differences between categorical variables for patients who died and those who survived. We calculated the mortality rate, not the overall case fatality rate (CFR) by dividing the number of people who died from COVID-19 by all cases diagnosed with COVID-19 infection during the study time interval.

Independent variables considered for the study included demographic variables (age, gender) and clinical variables (pre-existing conditions and symptoms). A manual stepwise forward selection procedure was used to enter variables with a p-value < 0.25 in the univariate analysis into the multivariable model. Both crude and Adjusted Odds Ratios (OR and AOR) with 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) were calculated. Logistic regression, a robust statistical method for a cross-sectional study, was used because it allows for the analysis of associations between multiple independent variables and a dichotomous outcome variable, which aligns perfectly with our study’s descriptive and association-identification objectives. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and retained in the final model.

The final multivariate model included the following variables: age group (years), Hypertension, Diabetes, Obesity, Pregnancy, Asthma, HIV, Tuberculosis, Hospitalized, and Disease Severity at Diagnosis. Model stability and fit were rigorously assessed. Multicollinearity between independent variables was checked using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). All VIF values were below 5 (maximum VIF = 2.1), indicating that multicollinearity was not a concern, thus confirming model stability. The Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was conducted to assess the model’s calibration (i.e., how closely the predicted probabilities matched the observed outcomes). The resulting p-value of 0.760 (with a null hypothesis of good fit) was not statistically significant (p>0.05), confirming that the logistic regression model adequately fits the data.

Ethical consideration

This study was carried out following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its subsequent amendments. Permission to access data was requested from the Eswatini Ministry of Health. The researcher adhered to the Data Protection Act. Even though the researcher was using secondary data, the dignity of the participants was maintained by prioritizing the privacy and anonymity of participants’ personal information. Confidentiality and anonymity were maintained such that all participants and unique identifiers were removed from the data once extracted and replaced with case numbers. The data was stored on a laptop that had a password. Databases created during the study period were password-protected, and only researchers actively involved in the study had access to them. Ethics approval was sought from the Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee (REC) of the University of Pretoria with reference number 70/2022. De-duplication was done using probability record linkage techniques with variables using a unique case number as a primary identifier, and then for those without a unique case number of name, age, and address of patients were used.

Results

Sample characteristics and case fatality

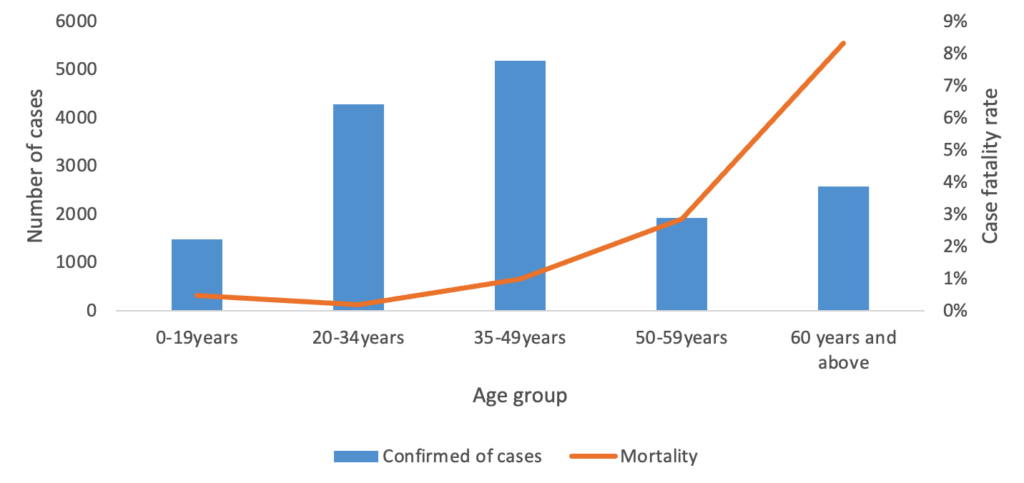

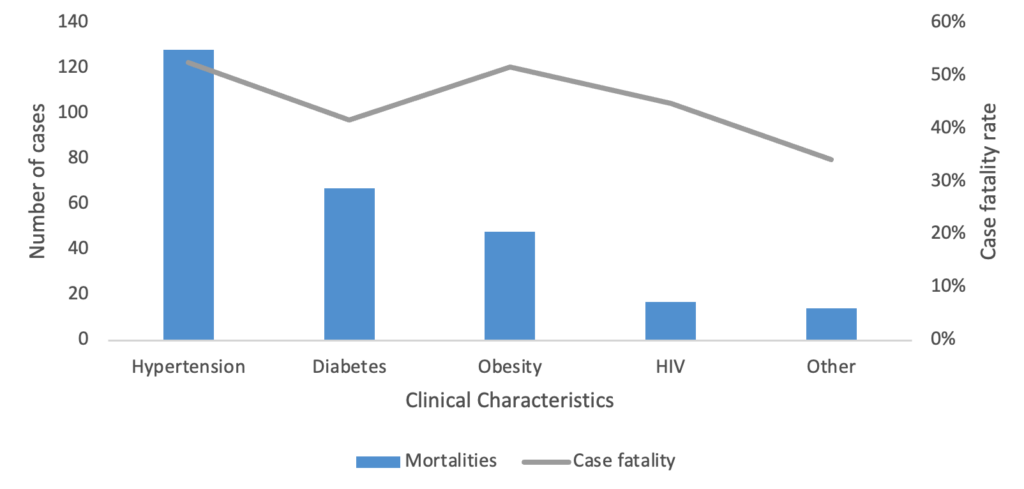

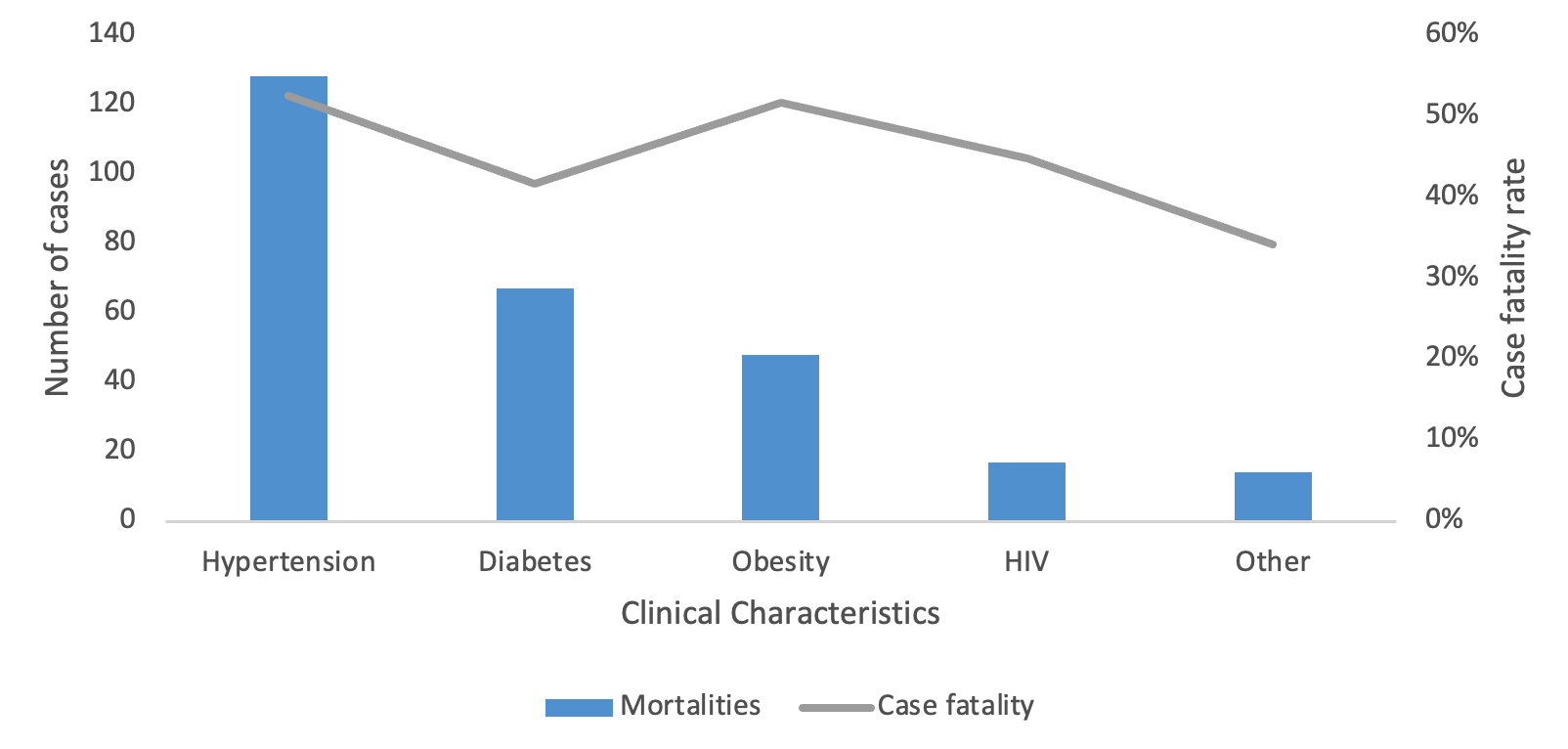

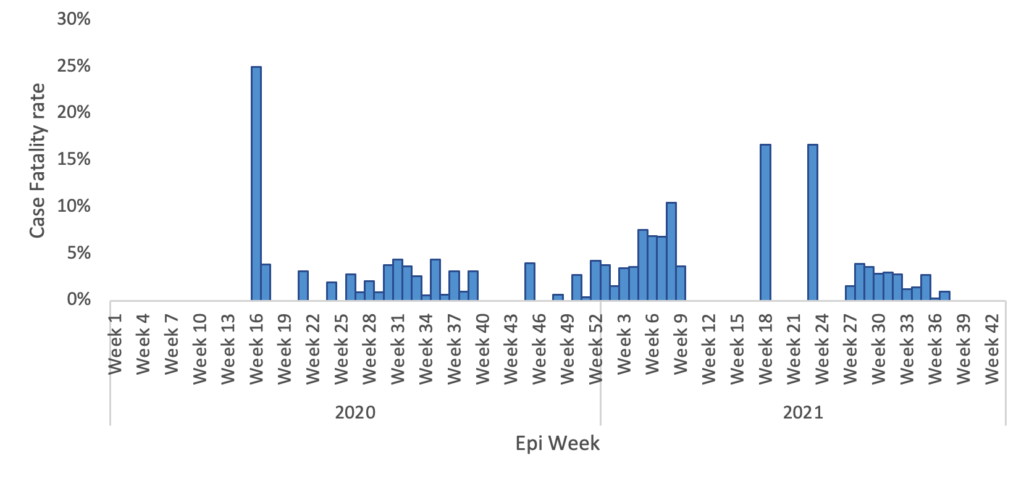

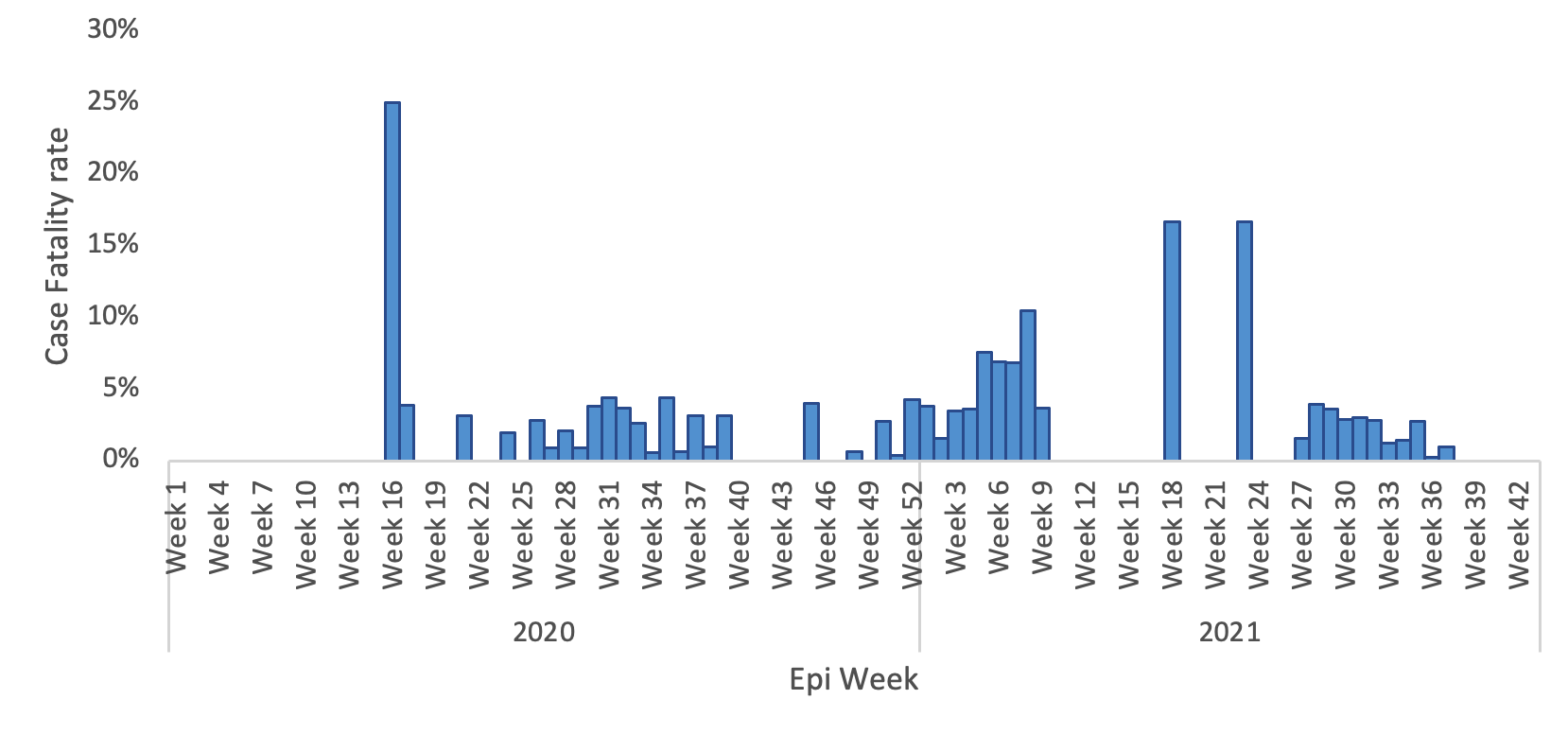

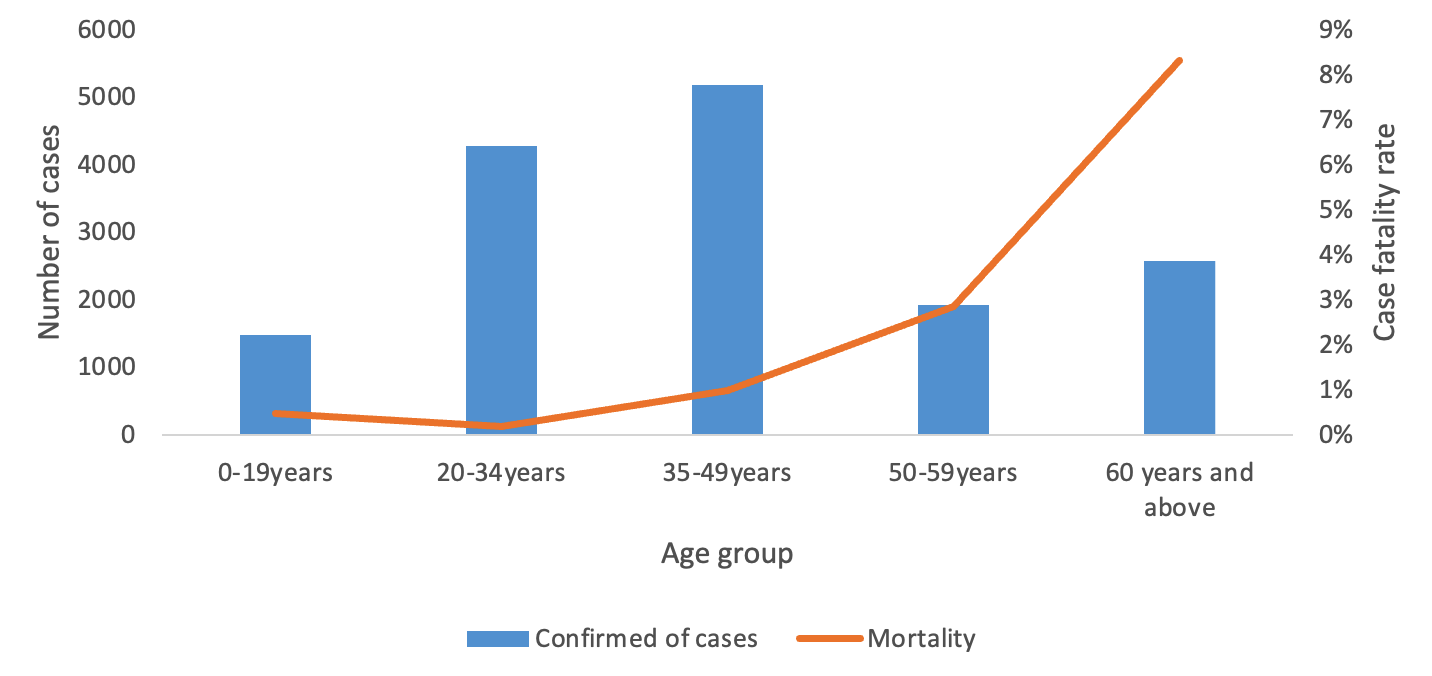

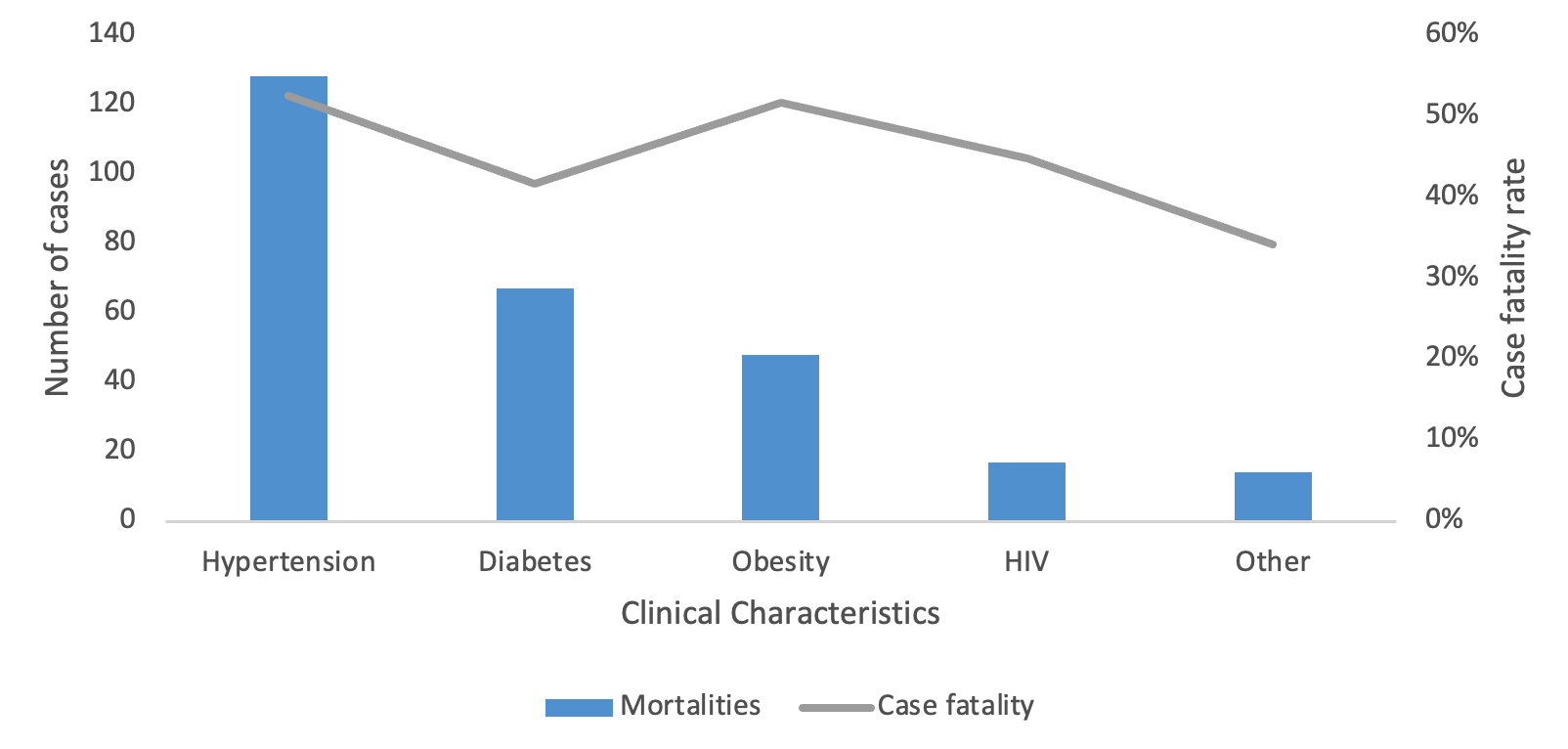

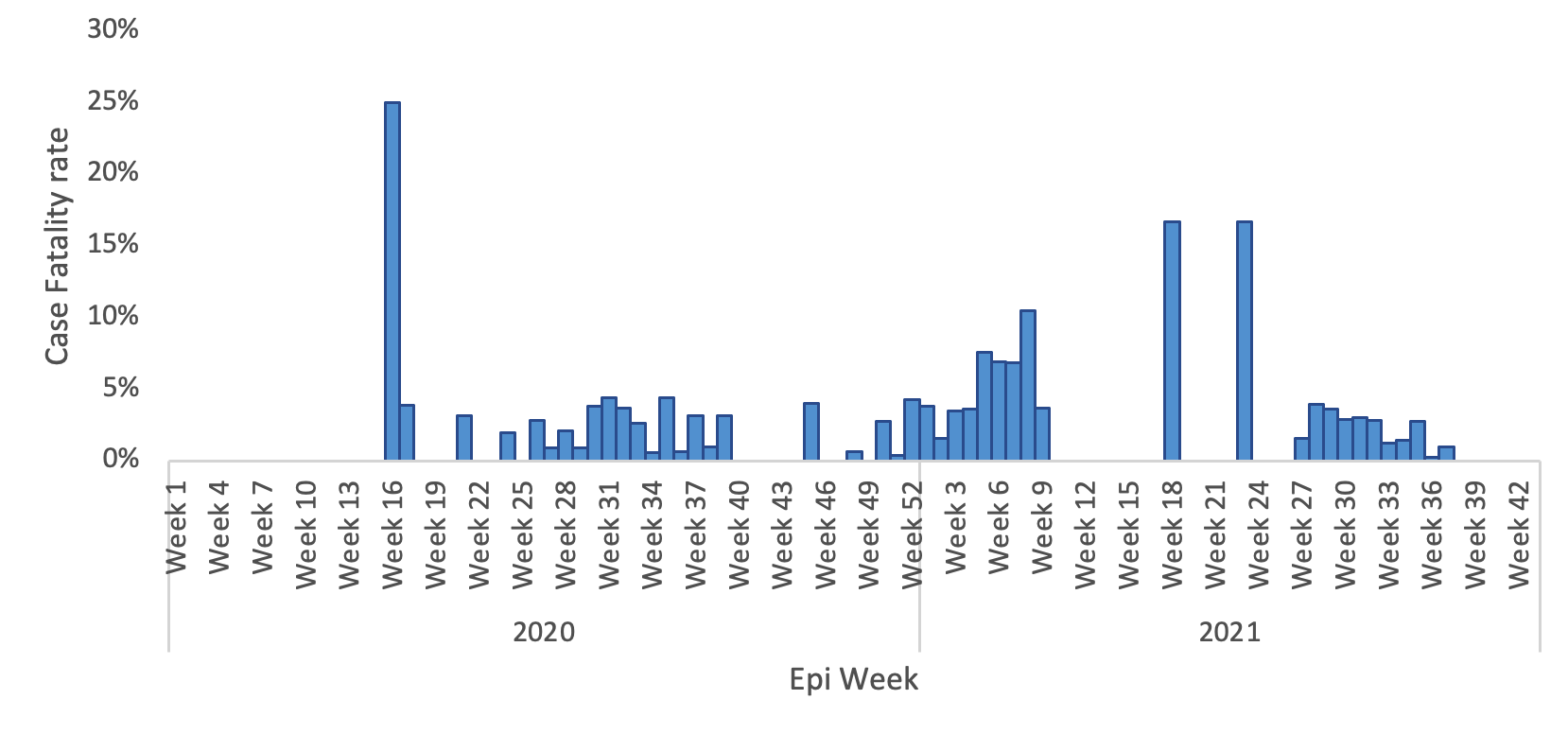

A total of 15,460 COVID-19 confirmed cases were included in the analysis, representing 98.8% of all cases (15,649) reported in the Manzini Region from 14 March 2020 to 31 August 2021. The overall COVID-19 case fatality was 2.2% (336/15,460). The majority of cases were aged 35–49 years, with a median age of 39 years (IQR: 35–49 years). The age group 60 years and above had the highest case fatality (Figure 2). Males accounted for 52.7% (177/336) of case fatality compared to 47.3% (159/336) among females. The most common comorbidities among those who died were hypertension (38.1%, 128/336) and diabetes mellitus (19.9%, 67/336) (Table 1, Figure 3). The epi curve showed the distribution of the mortalities over the study period (Figure 4)

Factors independently associated with case fatality

In unadjusted analysis (Table 1), case fatality was associated with age group (years), gender, hypertension, obesity, hospitalisation, and severity at diagnosis. After adjusting for covariates, several factors remained independently associated with fatality among COVID-19 patients. The likelihood of death was significantly higher among patients with hypertension (AOR = 3.57; 95% CI: 2.01–6.36; p < 0.001) and among those diagnosed in 2021 (AOR = 15.26; 95% CI: 6.60–35.24; p < 0.001) compared with 2020. Older age was strongly associated with increased fatality, where patients aged ≥60 years (AOR = 9.27; 95% CI: 3.12–25.92; p < 0.001) and 50–59 years (AOR = 8.12; 95% CI: 2.81–23.49; p < 0.001) had markedly higher odds of death compared with younger persons (below 20 years). Disease severity was also an important predictor. The risk of dying increased with clinical severity, from mild (AOR = 5.89; 95% CI: 2.94–11.80; p < 0.001) and moderate (AOR = 9.27; 95% CI: 3.12–25.92; p < 0.001) to severe disease (AOR = 123.71; 95% CI: 53.44–286.38; p < 0.001). Additionally, diabetes mellitus appeared to be associated with a lower likelihood of dying after adjustment for other factors (AOR = 0.35; 95% CI: 0.18-0.71; p < 0.00). (Table 1).

Discussion

This study investigated factors associated with COVID-19 case fatality in the Manzini Region of Eswatini between March 2020 and August 2021. We found a case fatality rate of 2.2% with marked temporal variation, substantially increased mortality among older adults and those with severe disease, and an unexpected 15-fold increase in odds of dying during 2021 compared with 2020. These findings characterise COVID-19 case fatality patterns in a resource-limited African setting and highlight temporal factors, age, disease severity, and hypertension as key determinants of fatal outcomes.

The CFR observed aligns with the range reported across sub-Saharan Africa during the first pandemic year (0.9–3.2%)[14], positioning Eswatini at intermediate risk. It exceeds rates in countries with younger populations and robust testing (e.g., Ghana 0.9%, Kenya 1.8%) but is lower than in settings with strained healthcare systems (e.g., Nigeria 2.9%, South Africa 3.2%)[6, 15, 18]. Notably, this rate is higher than estimates from high-income countries (0.5–1.0%)[33], reflecting the combined effects of limited ICU capacity, oxygen scarcity, delayed presentation, and unmanaged comorbidities in resource-constrained settings. In this context, mortality reflects not only viral pathogenicity but also health system limitations and population vulnerability[17,34,35].

The 15-fold increase in adjusted mortality odds observed in 2021 represents one of the study’s notable findings. Multiple factors likely contributed. The Beta variant (B.1.351), dominant in early 2021, demonstrated higher transmissibility and virulence [1]. Concurrently, healthcare system capacity deteriorated, with depleted oxygen supplies, persistently high ICU occupancy, and cumulative healthcare worker fatigue. Testing policies increasingly prioritise symptomatic cases, potentially inflating the CFR by underrepresenting mild or asymptomatic infections. Delayed care-seeking, driven by economic pressures and pandemic fatigue, may have further exacerbated mortality. This temporal pattern mirrors regional trends. South Africa’s second wave, driven largely by the Beta variant, was associated with approximately 30% higher in-hospital mortality compared with the first wave[36]. Similarly, Kenya documented a rise in national case fatality from 1.8% in 2020 to 2.4% in 2021[37]. These findings collectively underscore that pandemic preparedness in resource-limited settings must extend beyond initial containment phases. Maintaining surge capacity, oxygen infrastructure, and workforce resilience throughout successive waves is essential, as risk profiles evolve dynamically over time rather than remaining constant across epidemic phases.

The risk of dying was nine times higher among patients aged ≥60 years compared with those younger than 35 years, consistent with global evidence[38]. This pattern reflects well-established biological mechanisms, including immunosenescence and chronic low-grade inflammation, which impair the host’s ability to mount an effective response to SARS-CoV-2 infection. In Eswatini, however, these intrinsic vulnerabilities are compounded by social and structural barriers to timely care. Older adults often experience delayed presentation to health facilities, driven by financial constraints, transport challenges, and initial reliance on traditional remedies for respiratory symptoms. Consequently, many reach hospitals only when the disease is advanced. The burden of undiagnosed or poorly controlled comorbidities further amplifies this risk. An estimated 60% of individuals with hypertension and 50% with diabetes remain undiagnosed[39, 40]. Limited access to geriatric care and the fact that 42% of elderly households live below the poverty line [41] likely exacerbate these disparities. These findings underscore the interplay between biological ageing, structural inequities, and health system constraints in shaping COVID-19 mortality among older adults in low-resource settings.

Despite Eswatini’s younger population (median age 39 years, compared with 47–55 years in European cohorts[42], age remained a strong predictor of death, second only to disease severity. This suggests that age-related vulnerability operates across demographic contexts, though the relative contributions of biological ageing versus healthcare access limitations remain uncertain.

Although mortality was higher in men, gender was not statistically significant in our study. We could not conduct a gender Analysis to investigate gender-stratified results and describe gender-disaggregated outcomes in greater depth because there was no evidence to show that the gender variable is an effect modifier. However, in other studies like Grasselli et al., being male was associated with greater mortality among individuals infected with COVID-19 [43-45]. In addition, with 3.1 million participants, one major study reported that the male gender was associated with a higher ICU admission rate, mirroring the trend of increased mortality in this group [10, 20, 43]. The underlying mechanism for this phenomenon is thought to be the gender difference in immune cell characteristics: women exhibit elevated numbers of CD4+ T lymphocytes, superior cytotoxic efficacy of CD8+ T cells, and increased B cell-mediated immunoglobulin generation, allowing for the deployment of a more effective adaptive immune defence[10, 43-45].

Severe disease at presentation was the strongest clinical predictor of mortality, conferring a 124-fold increase in odds of death. This effect size exceeds estimates from high-income countries, where severe COVID-19 is typically associated with a 20–40-fold increased risk[46]. The difference likely reflects the limited capacity to manage advanced disease in resource-constrained settings. During the study period, Eswatini had approximately 2 ICU beds per 100,000 population [47]compared with 25–35 per 100,000 in Western Europe [48] and oxygen and mechanical ventilation were largely confined to referral hospitals.

Importantly, even patients with moderate disease faced an 11-fold increase in mortality odds, a pattern not commonly observed in high-income contexts [49]. Two factors may explain this. First, patients categorised as moderate may have deteriorated rapidly in the absence of systematic monitoring, as home-based surveillance was limited. Second, undiagnosed comorbidities could have accelerated progression to severe illness before clinical intervention. These findings suggest that in resource-limited settings, all symptomatic COVID-19 patients require timely clinical evaluation rather than relying solely on home-based management.

Hypertension emerged as a strong, independent predictor of COVID-19 mortality (AOR = 3.57), consistent with reports from other countries in the WHO African Region, where pre-existing conditions increase the risk of severe outcomes[50-52]. Many patients who initially reported no comorbidities were later diagnosed with unmanaged non-communicable diseases (NCDs) during hospitalisation, suggesting that undetected or poorly controlled conditions reduced physiological resilience to SARS-CoV-2 infection. In Eswatini, adult hypertension prevalence approaches 30%[39], with low rates of awareness, diagnosis, and effective control. COVID-19 may have unmasked previously undiagnosed hypertension or triggered decompensation in those with suboptimal management. The combination of high prevalence and inadequate control positions hypertension as a key, modifiable risk factor for COVID-19 deaths in this context, highlighting critical gaps in community-level NCD prevention and the urgent need to strengthen primary healthcare systems for early detection and management.

The observed protective association with diabetes likely reflects residual confounding, ascertainment bias, or preferential hospitalisation rather than a true biological effect [53-55]. First, diabetic patients may have been preferentially hospitalised due to perceived high-risk status, ensuring oxygen access and supportive care. Second, ascertainment bias may have operated, where blood glucose testing at admission would identify diabetes among survivors who underwent complete workups, while rapidly fatal cases may have lacked diagnostic evaluation. Third, residual confounding by treatment received, timing of presentation, or unmeasured disease characteristics may have influenced this association. Similarly, higher mortality among hospitalised patients reflects confounding by indication rather than the harmful effects of hospitalisation. Eswatini’s protocols prioritised hospital admission for patients aged ≥60 years, those with comorbidities, and those with moderate-to-severe symptoms[55]. Hospitalised patients thus represented a higher baseline risk population. Additionally, sicker patients who died rapidly may have been hospitalised, while mildly symptomatic individuals recovered at home.

Implications for policy and practice

Our findings have several actionable implications. First, pandemic preparedness must anticipate evolving risk across successive waves, ensuring sustained oxygen supply, ICU capacity, and workforce resilience. Second, age-targeted interventions, including prioritised vaccination and community-based monitoring for older adults, are warranted. Third, even mild-to-moderate cases require clinical oversight, including home oxygen programs and telemedicine support, to prevent progression to fatal outcomes. Fourth, strengthening NCD screening and management represents a critical investment for both infectious disease and pandemic preparedness. Finally, comprehensive surveillance systems capturing comorbidities, HIV status, vaccination history, and treatment data are essential for understanding mortality determinants in high-HIV-prevalence settings.

Strengths and limitations

This study’s primary strength is near-complete case capture (98.8%) within a defined geographic region, enabling population-based estimates and adjustment for multiple confounders. Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, comorbidity data were derived from self-report or medical records, likely underestimating undiagnosed conditions and potentially attenuating observed associations. Second, HIV status, an important risk factor in Eswatini, was inconsistently recorded, precluding its analysis. Third, data on vaccination status, treatments received, and timing of presentation relative to symptom onset were unavailable. Fourth, the diabetes finding’s biological implausibility suggests residual confounding or misclassification despite multivariable adjustment. Finally, while these findings provide valuable insights for resource-limited settings, their generalizability to regions with different healthcare infrastructure or epidemic dynamics may be limited.

Conclusion

COVID-19 case fatality in Manzini, Eswatini, was shaped by a combination of temporal, demographic, clinical, and structural factors. Advanced age, severe disease at presentation, hypertension, and evolving epidemic waves were key determinants of death. High case fatality among older adults and patients with moderate-to-severe disease highlights the critical need for early clinical intervention, strengthened NCD management, and sustained healthcare system capacity. These findings provide evidence to inform targeted public health strategies, resource allocation, and pandemic preparedness in resource-constrained African settings.

What is already known about the topic

- Age is recognised as the single most powerful predictor of severe illness and subsequent mortality from COVID-19 across all continents and healthcare settings. The risk increases exponentially starting from the fifth decade of life, with those aged ≥60 years bearing the overwhelming burden of fatal outcomes.

- Male sex has been consistently identified as an independent risk factor for adverse outcomes, including admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and death, with mortality rates typically higher in males than in females globally.

- The clinical presentation at diagnosis or admission is a decisive factor for prognosis. Patients classified with Severe or Critical disease, particularly those presenting with hypoxemia and requiring respiratory support, have a significantly higher risk of death compared to those with mild or moderate symptoms.

- The presence of pre-existing NCDs significantly elevates mortality risk. Hypertension, Diabetes Mellitus, and Obesity are the three most frequently reported and statistically robust risk factors associated with COVID-19 fatality in meta-analyses worldwide. Other important comorbidities include chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and cardiovascular disease.

- Conditions leading to immunosuppression, such as HIV (especially in patients with unsuppressed viral loads or low CD4 counts), cancer, and organ transplants, are widely recognized as increasing the odds of poor outcomes and death.

- The emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 variants (e.g., Delta and Alpha) has been linked to shifts in disease severity, transmissibility, and case fatality rates. Mortality risk tends to spike during periods dominated by more virulent strains.

- Studies have shown that when healthcare systems are overwhelmed (e.g., during major waves or peaks), the risk of patient mortality increases, even after adjusting for individual risk factors. This suggests that limited resources (ICU beds, oxygen, staff) contribute independently to adverse outcomes.

What this study adds

- Our primary novel finding is the demonstration that the Year 2021 was, by far, the most dominant independent risk factor for mortality (AOR 15.26, 95% CI 6.60–35.24). By including this temporal variable in our highly adjusted model, we show that the non-clinical, ecological pressures—such as the introduction of more virulent variants (e.g., Delta) and the potential for healthcare system saturation—had a significantly greater impact on patient outcome than many of the classic, individual risk factors. This emphasizes that mortality risk cannot be assessed solely on patient health status but must account for the rapid evolution of the pandemic and system capacity.

- International literature is often skewed toward high-income country data. Our study leverages national surveillance data from the Manzini Region, providing robust, patient-level evidence that reinforces the critical role of pre-existing conditions like Hypertension (AOR 3.57, 95% CI 2.01–6.36) in the African context, a factor highly relevant to local public health interventions.

- Our multivariate analysis uncovered an anomalous but statistically significant protective association with diabetes mellitus (AOR 0.35, 95% CI 0.18–0.71). This result, which runs counter to global clinical consensus, is likely a crucial indicator of selection bias related to local healthcare prioritization. We hypothesize that patients with known high-risk conditions, such as diabetes, who were placed under enhanced surveillance, benefited from earlier hospitalisation, or received immediate, aggressive clinical management, thereby improving their survival chances in our highly-adjusted model compared to the general case population. This finding provides unique insight into the operational response dynamics of the Eswatini healthcare system.

Funding

This study was funded by the South Africa Field Epidemiology Training Programme in collaboration with the University of Pretoria, Faculty of Health Sciences, School of Health Systems & Public Health. The funders had no role in the conceptualisation of the study, study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish and preparation of the manuscript.

Authors´ contributions

SM developed the protocol, data management, analysis, and report writing, and finalised the dissertation as well as oral presentations. VL assisted with student supervision, data access, and ethical clearance in Eswatini. KR assisted in protocol preparation, supervision, liaison with the student, preparation of presentations, data analysis plan, and report writing. MM assisted with mentorship in protocol review and manuscript writing. LK assisted with student supervision, Protocol reviews, and submission to the University of Pretoria ethics review committee. AM assisted in the analysis of the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

List of Abbreviations

- ARDS: Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- CFR: Case fatality rate

- CI: Confidence interval

- COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease-2019

- CT: Computer tomography

- COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- HR: Heart rate

- ICU: Intensive care unit

- IQR: Inter-quartile range

- LMIC: Low- and middle-income countries

- MERS: Middle East respiratory syndrome

- OR: Odds ratio

- PHEIC: Public health emergency of international concern

- RT-PCR: Reverse transcriptase– polymerase chain reaction assay

- SARS: Severe acute respiratory syndrome

- SARS-CoV-2: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2

- SD: Standard deviation

- SpO2: Peripheral capillary oxygen saturation

- WHO: World Health Organization

| Table 1. Factors associated with mortality among patients with COVID-19 in the Manzini Region, Eswatini, March 2020–August 2021. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Dead N=336 n (%) | Survived N=15124 n (%) | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

| Crude Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |||||

| Year | ||||||||

| 2020 | 102 (30.36) | 4225 (27.94) | Reference | |||||

| 2021 | 234 (69.64) | 10899 (72.06) | 0.89 (0.70–1.13) | 0.32 | 15.26 (6.60–35.24) | <0.001 | ||

| Age group (Years) | ||||||||

| 0–19 | 7 (2.08) | 1470 (9.72) | Reference | |||||

| 20–34 | 8 (2.38) | 4275 (28.27) | 0.39 (0.14–1.09) | 0.07 | 0.50 (0.14–1.74) | 0.28 | ||

| 35–49 | 51 (15.18) | 5140 (33.99) | 2.08 (0.94–4.60) | 0.07 | 2.48 (0.87–7.01) | 0.09 | ||

| 50–59 | 55 (16.37) | 1873 (12.38) | 6.17 (2.80–13.58) | <0.001 | 8.12 (2.81–23.49) | <0.001 | ||

| ≥60 | 215 (63.99) | 2366 (15.64) | 19.08 (8.96–40.62) | <0.001 | 9.27 (3.12–25.92) | <0.001 | ||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 177 (52.68) | 6851 (45.30) | Reference | |||||

| Female | 159 (47.32) | 8273 (54.70) | 0.74 (0.60–0.92) | 0.01 | 0.80 (0.55–1.15) | 0.23 | ||

| Hypertension | ||||||||

| No | 144 (42.86) | 258 (1.71) | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 128 (38.10) | 116 (0.77) | 1.98 (1.43–2.73) | <0.001 | 3.57 (2.01–6.36) | <0.001 | ||

| Unknown | 64 (19.05) | 14750 (97.53) | 0.01 (0.01–0.01) | 0.00 | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 | ||

| Diabetes Mellitus | ||||||||

| No | 205 (61.01) | 280 (1.85) | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 67 (19.94) | 94 (0.62) | 0.97 (0.68–1.40) | 0.89 | 0.35 (0.18–0.71) | <0.001 | ||

| Unknown | 64 (19.05) | 14750 (97.53) | 0.01 (0.01–0.01) | <0.001 | Omitted | |||

| Obesity | ||||||||

| No | 288 (85.71) | 15079 (99.70) | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 48 (14.29) | 45 (0.30) | 55.84 (36.58–85.26) | <0.001 | 1.06 (0.46–2.45) | 0.89 | ||

| HIV | ||||||||

| No | 255 (75.89) | 353 (2.33) | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 17 (5.06) | 21 (0.14) | 1.12 (0.58–2.17) | 0.74 | 0.47 (0.12–1.87) | 0.28 | ||

| Unknown | 64 (19.05) | 14750 (97.53) | 0.01 (0.01–0.01) | <0.001 | Omitted | |||

| Hospitalization | ||||||||

| No | 250 (74.40) | 14247 (94.20) | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 86 (25.60) | 877 (5.80) | 5.59 (4.33–7.21) | <0.001 | 1.35 (0.83–2.20) | 0.22 | ||

| Severity at Diagnosis | ||||||||

| Asymptomatic | 13 (3.87) | 3038 (20.09) | Reference | |||||

| Mild Disease | 123 (36.61) | 10538 (69.68) | 2.73 (1.54–4.84) | <0.001 | 5.89 (2.94–11.80) | <0.001 | ||

| Moderate Disease | 50 (14.88) | 1341 (8.87) | 8.71 (4.72–16.09) | <0.001 | 12.67 (5.54–29.01) | <0.001 | ||

| Severe Disease | 150 (44.64) | 207 (1.37) | 169.34 (94.45–303.64) | <0.001 | 123.71 (53.44–286.38) | <0.001 | ||

References

- Jassat W, Mudara C, Ozougwu L, Tempia S, Blumberg L, Davies MA, Pillay Y, Carter T, Morewane R, Wolmarans M, Von Gottberg A, Bhiman JN, Walaza S, Cohen C, Abdullah S, Abrahams F, Adams V, Adnane F, Adoni S, Adoons DM, Africa V, Aguinaga D, Akach S, Alakram Khelawon P, Aldrich G, Alesinloye O, Aletta MB, Alice M, Aphane T, Archary M, Arends F, Arends S, Aser M, Asmal T, Asvat M, Avenant T, Avhazwivhoni M, Azuike M, Baartman J, Babalwa D, Badenhorst J, Badenhorst MB, Badripersad B, Badul L, Bagananeng M, Bahle M, Balfour L, Baloyi T, Baloyi S, Baloyi T, Baloyi TM, Banda T, Barit S, Bartsch N, Bayat J, Bazana S, Beetge M, Bekapezulu N, Belebele R, Bella P, Belot Z, Bembe LG, Bensch S, Beukes G, Bezuidenhout K, Bhembe T, Bikisha NA, Bilenge B, Bishop L, Biyela B, Blaauw C, Blaylock M, Bodley N, Bogale P, Bokolo S, Bolon S, Booysen M, Booysen E, Boretti L, Borges P, Boshoga M, Bosman N, Bosvark L, Botes N, Botha A, Botha C, Botha J, Botha MI, Botha A, Bradbury J, Breakfast Z, Breed M, Brenda M, Brice M, Britz J, Brown A, Buchanan MT, Bucwa T, Burger C, Busakwe Z, Bushula N, Buthelezi Z, Buthelezi D, Buthelezi T, Buthelezi MB, Buthelezi FL, Bux N, Buys C, Buys A, Caka E, Canal AS, Caroline S, Casper M, Cawood S, Cebisa O, Cele N, Cele S, Cele SG, Chauke M, Chauke P, Chelin N, Chen X, Chetty V, Chetty K, Cheu C, Chibabhai V, Chirima T, Chisale Mabotja M, Chivenge C, Choene N, Choko MN, Choshi M, Chowdhury S, Christoforou A, Chuene SLS, Chueu TS, Cilliers D, Cilliers V, Claassen M, Cloete J, Coelho C, Coetzee C, Coetzee HJ, Coetzee C, Coetzee M, Coetzer D, Coka S, Colane MM, Combrink H, Conjwa S, Contrad C, Cornelissen F, Cronje L, Crouse C, Dabi T, Dandala Z, Dangor Z, Daniel G, Daniel N, Daumas A, Dauth M, David M, Davids W, Daweti N, Dawood H, Dayile W, De Bruin B, De Klerk K, De La Rosa T, De Nysschen M, De Vos M, De Wet D, Debising M, Deenadayalu D, Dekeda B, Desiree M, Deysel A, Dhlamini A, Diala MD, Diale M, Diketane B, Dingani N, Diniso S, Diphatse L, Diya A, Dladla Z, Dladla N, Dladla M, Dladla P, Dlamini B, Dlamini N, Dlamini L, Dlamini N, Dlamini W, Dlamini N, Dlamini S, Dlamini N, Dlamini L, Dlamini M, Dlava BC, Dlova P, Dlozi L, Doreen M, Doyi V, Doyi A, Du Plessis B, Du Plessis JA, Du Plessis MrE, Du Plessis N, Du Plessis K, Du Toit B, Du Toit N, Dube J, Dubula A, Duduzile M, Duiker S, Duma UB, Duma K, Dunne K, Dyantyi K, Dyantyi A, Dyasi S, Dyondzo C, Dyubhele P, Dywili BJ, Edwards LE, Eksteen M, Ellis T, Ellis T, Emmerson G, Enslin T, Epule O, Erasmus L, Erick M, Etsane L, Eunice S, Fani Z, Ferreira M, Finger-Motsepe KL, Floris F, Fobo T, Fokotsane K, Fokwana DE, Fords GM, Fortein J, Fouche C, Fourie R, Frean A, Fredericks L, Funda W, Funjwa K, Futhane M, Futuse A, Gabaediwe D, Gabuza N, Galant J, Gama Z, Gano T, Gardiner EC, Gastrow H, Gate K, Gaunt B, Gavaza R, Gayi T, Gcakasi N, Gcobo N, Geffen L, Geldenhuys S, George J, Gerber M, Getyengana Z, Gigi N, Gihwala R, Gilliland M, Gloria Z, Glover E, Gokailemang E, Goosen S, Gopane M, Gosa-Lufuta T, Gosnell B, Gouws S, Govender C, Govender R, Govender P, Govender S, Govender C, Govender R, Govender K, Govender MS, Govinden R, Gqabuza L, Gqaji N, Gqetywa M, Green C, Green N, Grobler H, Groenwald P, Grootboom D, Gumede B, Gumede N, Gumede S, Gumede S, Gumede S, Gumede N, Gumede Z, Gxotiwe T, Hadebe N, Hadebe S, Halkas C, Hamer A, Hamida E, Hammond J, Haniff S, Hare A, Hattingh L, Hendricks T, Henecke PG, Henly-Smith B, Herselman G, Heymans A, Heyns C, Hlabahlaba G, Hlabangwane L, Hlamarisa S, Hlanzi N, Hlela H, Hlokwe K, Hlongwa T, Hlongwana A, Hlubi T, Hobo T, Hopane NN, House M, Hudson C, Huysamen M, Indheren J, Ingle S, Isaacs G, Isaacs TT, Itumeleng M, Jackson S, Jacob N, Jacobs B, Jacobs T, Jacobs G, Jaftha M, Jaji Z, Jali S, James G, January G, Jeke A, Jeremiah L, Jhetam M, John M, John C, Jola T, Jonas Y, Jonas A, Juggernath A, Kaba E, Kabo V, Kadi D, Kaizer K, Kambule MP, Kapp L, Kau T, Keneth N, Kgabi O, Kgafela TA, Kgakgadi V, Kgaswe I, Kgathlane T, Kgetha VJ, Kgomojoo M, Kgoro MB, Kgosiemang C, Kgosiencho G, Khambula S, Khan A, Khanare R, Khanyase N, Khanyile N, Kharatsi F, Khawula S, Khohlakala T, Khomo L, Khoza I, Khoza S, Khukule N, Khumalo B, Khumalo T, Khumalo Z, Khumalo V, Khumalo D, Khumalo L, Khumalo B, Khumalo T, Khumalo G, Khuzwayo B, Khuzwayo T, Kidson H, Kistan J, Klaas G, Klassen M, Koeberg J, Koen M, Koena S, Kok I, Kola I, Kolokoto K, Konar R, Kotsedi D, Kotze J, Koupis Cds M, Kritzinger SH, Kruger M, Kruger H, Kubayi T, Kubeka T, Kubheka N, Kubheka M, Kubheka SC, Kubheka E, Kumalo M, Kunene T, Kunene SC, Kunneke Y, Kupa RP, Kutama R, Kwakwazi N, Kweyama L, Labuschagne M, Lakshman P, Lamani L, Lamani T, Langa N, Langeni K, Langeni A, Langeveldt G, Laubscher A, Le Roux L, Leah M, Lebea C, Lebea S, Lebenya VPC, Lebogang L, Leboho P, Lee C, Lefakane KR, Legoabe Z, Lekala P, Lekhoaba M, Lekunutu TS, Lerefolo G, Letebele MN, Lethoba TP, Letlalo E, Letlhage O, Letshufi DSV, Letsoalo DF, Letsoalo SJ, Letsoalo P, Letwaba G, Linda S, Lipholo K, Litabe S, Lochan H, Lomax L, Lombaard F, Loots E, Lourens A, Louw C, Louw R, Lubambo Z, Lubambo MM, Ludada G, Lukas M, Lungu T, Lupindo N, Lusenga E, Luthuli H, Luvuno ZS, Maarman M, Mabaso B, Mabaso C, Mabitle M, Mabogoane G, Mabone K, Mabuza R, Mabuza V, Madiseng M, Madlala T, Madolo M, Madonsela T, Madubanya L, Maepa A, Mafumana N, Mafumo C, Magadla P, Magale V, Magaqa N, Magda O, Magdeline R, Maggie T, Maginxa B, Magoba CM, Magongwa C, Magubane A, Magubane AN, Magwai R, Mahabeer P, Mahadulula E, Mahanjana L, Maharaj A, Mahlambi Q, Mahlangu Y, Mahlangu L, Mahlangu N, Mahlangu M, Mahlangu M, Mahlasela P, Mahlatse T, Mahlobo R, Mahole D, Mahomed A, Mahubane MD, Mahume P, Maifo L, Maimane V, Maimele P, Maine P, Mainongwane PS, Majamani N, Majozini A, Makalima N, Makam N, Makamba K, Makan R, Makarapa M, Makgahlela M, Makgisa MD, Makgomo M, Makgopa M, Makhalema M, Makhanya LL, Makhanya PV, Makharaedzha T, Makhathini N, Makhesi E, Makhubela C, Makhunga NF, Makhupula N, Makhura R, Makola R, Makuba Z, Makubalo A, Makumsha L, Makuya G, Malaka LM, Malangeni T, Malatji M, Malebana-Metsing P, Malek M, Malevu L, Malgas J, Malgas D, Malope PM, Malose M, Maluleke K, Mambane K, Mamorobela N, Manamela K, Manana T, Maneto S, Manganye AK, Mangena P, Mangoale A, Mangozho TF, Manickchund P, Mankayi Z, Manning A, Manyaapelo KM, Manyane T, Manzana Z, Manzini M, Mapasa-Dube B, Maphumulo S, Maphumulo N, Maponya S, Maponya KM, Maponya N, Maqubela L, Maqubela L, Maqungo V, Marais M, Marais C, Maramba N, Mare A, Maredi M, Martins A, Marule J, Marumo R, Masakona N, Masehla KV, Maseko E, Maselesele T, Maselo M, Maseloa M, Masemola ME, Masemola T, Mashaba B, Mashangwane J, Mashao M, Mashego S, Mashele L, Mashiane E, Mashibini J, Mashilo J, Mashiloane T, Mashishi C, Mashiyi N, Mashudu K, Masindi A, Maslo C, Masondo N, Masuku D, Matamela C, Matandela M, Mathabela N, Mathabi T, Mathe K, Mathebula M, Mathebula C, Mathebula MA, Mathenjwa N, Mathibe J, Mathibela L, Mathilda M, Mathiva K, Mathobela MA, Mathonsi FP, Mathonsi K, Mathosa K, Matiwane N, Matjeke E, Matjiane B, Matjila T, Matlala SC, Matome P, Matoti N, Matseliso C, Matsemela D, Matsha P, Matshediso GP, Matshediso M, Matshela E, Mavuma B, Mavundla P, Mavuso N, Mawasha L, Mawelela R, Mazibuko N, Mazibuko P, Mazubane L, Mbanjwa B, Mbasa A, Mbatha N, Mbatha Z, Mbatha RZ, Mbedzi G, Mbizi TT, Mbonambi K, Mboniswa N, Mbonisweni N, Mbuilu J, Mbulawa S, Mbutho Z, Mbuzi N, Mchunu N, Mchunu C, Mchunu N, Mchunu MT, Mciteka V, Mdaka S, Mdakane N, Mdediswa S, Mdima M, Mdima Masondo N, Mdindana S, Mdleleni N, Mdletshe S, Mdoda GP, Mdolo N, Mdontsane A, Mehta R, Memela PR, Methuse M, Metshile K, Metuse P, Meyer A, Meyer G, Meyer C, Mfazwe S, Mfecane A, Mfecane B, Mfeka N, Mgaga B, Mgauli TP, Mgedezi T, Mgedezi V, Mgevane K, Mgiba B, Mgoduka B, Mhlaba P, Mhlaba Z, Mhlanga N, Mhlinza V, Mhlongo N, Mhlongo S, Mhlotshana U, Mikateko M, Minnie H, Mintoor K, Miyeni B, Mj M, Mjethu R, Mkhize G, Mkhize M, Mkhize NS, Mkhize V, Mkhize N, Mkhize N, Mkhwanazi M, Mkile N, Mkise K, Mkiya N, Mkongi P, Mkungeka M, Mlahleki H, Mlibali N, Mlungwana S, Mmachele J, Mmateka M, Mmokwa M, Mmutlane T, Mndebele ZO, Mngomezulu N, Mnguni NM, Mngunyana P, Mngunyana N, Mngxekeza N, Mnisi Z, Mnqayi HP, Mnqayi P, Mntungwa T, Mnyaka S, Mnyakeni N, Mnyamana V, Mnyipika N, Moabelo K, Moatshe MA, Mochaki-Senoge JMS, Moche S, Mocwagae T, Modibane K, Modimoeng TG, Modisa O, Modisane I, Modise O, Modjadji MF, Modupe S, Moeketsi M, Moeketsi N, Moeng KK, Mofamere NN, Mofokeng S, Mofokeng T, Mofomme J, Mogakane V, Mogale L, Mogapi A, Mogashoa T, Mogatla MJ, Mogoale K, Mohajane DM, Mohapi N, Mohatsela M, Mohlala I, Mohlala D, Mohlamonyane M, Mohutsiwa BM, Moipone S, Moisi T, Mojalefa N, Moji V, Mokangwana B, Mokgabo M, Mokgaetji M, Mokgaotsi J, Mokgoro NT, Mokhatla T, Mokhele LL, Mokhema S, Mokoena M, Mokoena M, Mokome L, Mokone C, Mokono I, Mokonyama T, Mokori J, Mokuena D, Mokumo D, Mokwena O, Mokwena K, Mokwena KS, Mokwene L, Molate TE, Molebalwa D, Molefe B, Molehe KS, Moleme K, Moliane S, Moloi F, Molorane RJ, Molotsi GT, Molukanele L, Monareng J, Moncho T, Monica M, Monnane R, Monqo A, Montewa N, Montsioa K, Monyaki R, Monyane MJ, Monyela L, Moodley Y, Moodley K, Moodley K, Mooka BD, Moonsamy P, Moopanar S, Moore D, Mophethe L, Moremedi T, Moremong K, Morgan N, Moripa E, Morris L, Mosala MeAM, Mosana T, Mosase A, Mose Y, Mosehlo M, Moseki M, Moshabe MD, Moshani M, Moshani P, Mosima L, Mosima E, Mosoma MP, Motaung L, Motaung M, Motaung Xhama TC, Motha PK, Motimele L, Motimeng B, Motladiile S, Motlhabane O, Motlhamme J, Motloba M, Motse K, Motshegoa S, Moutlana E, Mouton I, Moya Z, Moyake N, Mpete J, Mpfuni LM, Mphahlele SM, Mphake M, Mphanya EL, Mphaphuli M, Mphela TC, Mpontshane M, Mqotyana T, Mqungquthu B, Msane NB, Mseleku M, Msibi S, Msibi M, Msibi T, Msibi SL, Msiza CN, Msomi L, Mtatambi M, Mthathambi T, Mthembu D, Mthembu N, Mthembu FM, Mthembu L, Mthethwa NP, Mthimkhulu K, Mthuli LP, Mthunzi A, Mtolo XS, Mtolo NP, Mtshali L, Mtwa N, Mtyobile F, Mtyobile K, Mudau M, Muemeleli M, Mulaudzi I, Mulaudzi R, Mulaudzi M, Muligwe DR, Muponda B, Mushadi MS, Mushid M, Muthaphuli K, Muthavhine J, Muthika M, Mvelase S, Mvelase V, Mwehu LK, Myaka T, Myburgh M, Mzamo Z, Mzawuziwa F, Mzini ML, Mzizana O, Mzobe N, Mzobe T, Mzobe Z, Mzwandile M, Naby F, Naicker K, Naicker P, Naicker S, Naicker P, Naicker SV, Naidoo R, Naidoo S, Naidoo M, Naidoo K, Naidoo A, Naku S, Nakwa F, Nancy M, Nathan R, Naude M, Ncaza G, Ncaza A, Ncha R, Ncoyini Y, Ncube S, Ndaba M, Ndaba V, Ndaba M, Ndawonde S, Ndevu Z, Ndhlovu NF, Ndima S, Ndlela S, Ndlela TP, Ndlovu N, Ndlovu N, Ndlovu VD, Ndlumbini S, Nduli K, Nduli PN, Ndwambi M, Nel J, Nel R, Nel L, Nemanashi NF, Nemudivhiso UN, Nemutavhanani JN, Nene J, Nene X, Netshilonga D, Netsianda R, Newton C, Ngalo VL, Ngani N, Ngcakaza TM, Ngcobo T, Ngcobo TN, Ngcobo R, Ngcobo G, Ngcobo G, Ngetu T, Ngewu P, Ngobeni T, Ngobeni P, Ngobeni K, Ngobeni P, Ngobese T, Ngomane T, Ngondo N, Ngubane N, Ngubane S, Nguse NP, Ngwane T, Ngwasheng E, Ngwenya S, Ngwenya G, Ngwenya N, Ngwenya T, Ngwenya E, Ngxola Z, Nhabe T, Nhlabathi J, Nhlangwana I, Nhlapo S, Nick M, Niemand V, Nienaber C, Nix L, Njikelana C, Njomi M, Nkabinde L, Nkabinde M, Nkabiti B, Nkabule G, Nkadimeng M, Nkanjeni N, Nkatlo PP, Nkewana B, Nkhwashu A, Nkoana N, Nkoane M, Nkogatse M, Nkomo F, Nkomo N, Nkonyane N, Nkosi S, Nkosi N, Nkosi P, Nkosi N, Nkosi T, Nkosi M, Nkosi G, Nkosi A, Nkosi FV, Nkosi M, Nkosi NL, Nkosi S, Nkuhlu A, Nkumane P, Nkuna M, Nkwakwha W, Noge S, Nolte E, Nomawabo P, Nombita M, Nophale N, Nothnagel J, Novokoza B, Nqaphi Z, Nqondo T, Nqwelo S, Ntabeni S, Ntabeni M, Ntampula M, Ntebe M, Ntela M, Ntimbane H, Ntintsilana X, Ntleki P, Ntobela Z, Ntombela B, Ntombela B, Ntombela Z, Ntombela KZ, Ntombela PST, Ntonintshi L, Ntseane D, Ntseane T, Ntsham X, Ntshele M, Ntshewula A, Ntsoko Z, Ntsoto A, Ntuli N, Ntuli N, Ntuli N, Ntuli AD, Ntuli F, Nurnberger M, Nxala N, Nxasane S, Nxumalo MT, Nyathi X, Nyawula N, Nzama N, Obed MN, Ogwal F, Olifant M, Oliphant MB, Olive M, Olyn K, Omoighe R, One P, Oscar R, Owen N, Padayachee N, Padayachy V, Pakade N, Palime M, Palisa J, Parker A, Parkies L, Parrish A, Patel N, Pather A, Patience MT, Patzke M, Pawuli A, Pelako N, Penrose PS, Peppeta L, Pershad S, Pertunia M, Pertunia N, Perumal D, Peter M, Peters J, Petlane V, Petrus H, Phahladira K, Phakisa MJ, Phale R, Phathela L, Phillip SD, Phiri B, Phiri MP, Phokane T, Phokoane F, Pholosho M, Phooko S, Phooko SG, Phutiane M, Pillay F, Pillay M, Pillay S, Pillay C, Plaatjie Z, Pootona J, Potgieter S, Potgieter M, Precious MM, Pretorius PJ, Prozesky H, Pule M, Punwasi J, Putzier D, Qankqiso L, Qebedu S, Qhola P, Qotoyi N, Qotso SV, Qwabe Z, Rabie H, Rabothata P, Rachoene C, Radana M, Radebe M, Radebe DrV, Radebe N, Radinne E, Raduvha S, Raghunath S, Rajagopaul C, Rakgwale M, Ralethe MM, Ralimo K, Ramafoko M, Ramagoma M, Raman C, Ramavhuya D, Rambally M, Ramdeen N, Ramdin T, Rameshwarnath S, Ramkillawan Y, Ramotlou, Rampedi F, Rampersad V, Ramuima A, Ranone N, Rapasa MP, Rapelang M, Raphaely N, Rashokeng L, Rashopola C, Ratau T, Ratau M, Ratshili MD, Rautenbach E, Ravele R, Reachable J, Rebecca PM, Reddy K, Redfern A, Reed R, Rees M, Reji D, Reubenson G, Rewthinarain V, Rheeder P, Rhulani N, Richard M, Rikhotso JS, Rikhotso SB, Robert LN, Roto N, Ruder G, Rugnath K, Ruiters L, Ruiters M, Russell S, Ruwiza L, Saaiman M, Sabela E, Sadiq L, Saki L, Salambwa H, Samjowan M, Samodien N, Samuel R, Sandile F, Sanelisiwe C, Sani M, Sawuka S, Schoeman L, Scholts M, Schroder R, Sebalabala M, Sebati SC, Seboko J, Sebuthoma W, Segami A, Segokotlo R, Sehloho M, Seisa K, Sekgobela A, Sekhosana M, Sekonyela J, Sekoto M, Sekulisa N, Sekwadi MV, Selaelo L, Selatlha J, Selekolo K, Selfridge W, Semenya L, Sengakane I, Sengata M, Sentle P, Seoketsa M, Seonandan P, Serumula TM, Setheni N, Setlale R, Setlhodi T, Setlhodi B, Setloghele R, Sewpersad A, Sewpersadh R, Shabalala P, Shabangu O, Shabangu K, Shabangu HS, Shabangu DT, Shadi C, Shaik H, Shale T, Shandu Q, Shandu N, Shange NM, Shenxane A, Sherriff A, Shezi S, Shezi T, Shihangule S, Shikwambana C, Shoba L, Shokane K, Sibande N, Sibeko L, Sibeko X, Sibiya Z, Sibiya M, Sibuta S, Sifumba T, Sigcau S, Sigila L, Sihentshe K, Sihlangu B, Sikhakhane D, Sikhakhane SN, Siko M, Sikonje S, Simanga K, Simango N, Simela T, Simelane N, Singh S, Singh M, Singh MR, Singh S, Singh A, Sithole H, Sithole S, Sithole ND, Sithole KM, Situma J, Sivraman A, Siwela K, Siyewuyewu N, Sizeka M, Siziba N, Skhosana A, Skhosana K, Skhosana R, Skoko T, Slabbert S, Smangaliso N, Smedley C, Smit L, Smit N, Smit L, Smit M, Smith F, Smith L, Smith S, Smith C, Smuts S, Sofe A, Solomon K, Solomon L, Sombani C, Songca R, Sontamo A, Soorju S, Sopazi Z, Soqasha B, Sosibo B, Sotsaka N, Soula M, Spoor S, Stacey S, Stali A, Stephina MM, Steup M, Steven S, Stevens A, Stevens V, Steyn D, Steyn B, Stocks P, Stolk H, Stoltz A, Strehlau R, Stroebel A, Strydom L, Strydom JM, Strydom A, Strydom U, Sunnyraj M, Swana N, Swanepoel W, Swanepoel S, Swartbooi E, Swartz ES, Syce C, Tabane J, Tabane N, Tawana M, Tebello N, Tembe SW, Terblanche S, Thabede N, Thabelo N, Thabethe S, Thabo George L, Thare K, Thebogo M, Thekiso L, Theko L, Themba CZ, Theron D, Theron H, Theron I, Thingathinga T, Thlabadira MM, Thoka D, Thokwana Z, Thom G, Thubakgale MJ, Thwala T, Thys P, Tieho M, Timothy M, Tintswalo N, Tivana B, Tladi M, Tokota B, Toni S, Torres A, Toubkin M, Tsatsi M, Tshabalala K, Tshamase N, Tshefu G, Tshegofatjo M, Tshikomba G, Tshilo T, Tshira L, Tshirado ST, Tshisikule M, Tsoke G, Tsoke N, Tsoko A, Tsotetsi M, Tsubella S, Tuswa N, Tutse M, Tutu N, Twala S, Twala N, Twala S, Ubisi J, Unathi T, Van Aswegen A, Van Der Merwe M, Van Der Merwe T, Van Der Plank P, Van Der Spuy E, Van Der Westhuizen L, Van Der Westhuizen A, Van Der Westhuizen T, Van Der Westhuyzen M, Van Dyk T, Van Heerden I, Van Jaarsveld R, Van Jaarsveld R, Van Lill M, Van Niekerk H, Van Niekerk B, Van Rensburg A, Van Schallwyk J, Van Sensie ZY, Van Vuuren M, Van Vuuren C, Vandu OF, Vane M, VanZyl L, Variava E, Veerus M, Velapi N, Veleko S, Velezantsi Z, Venter R, Vergottini C, Vergottini C, Vermeulen I, Vidah LL, Vilakazi B, Vilakazi TN, Vilakazi MP, Viljoen K, Viljoen W, Viljoen K, Volschenk Z, Vos A, Walters J, Webb K, Welsh J, Wessels D, Wheller J, White F, White P, Whyte C, Willemse A, William S, Williams D, Williams K, Williams M, Williamson A, Wilson C, Wolff B, Wray M, Xaba NB, Xaba TJ, Xiniwe T, Xoliswa M, Xulu F, Xulu G, Yam S, Zakhura N, Zareloa M, Zinto S, Zinziswa D, Ziselo L, Zitha Z, Zitha E, Zokufa A, Zondi I, Zondi SB, Zondi S, Zondi T, Zongola W, Zühlke L, Zulu Z, Zulu L, Zulu T, Zulu S, Zulu N, Zuma A, Zungu P, Zungu P, Zungu M, Zungu P, Zwakala BL, Zwane A, Zwane P, Zwane M, Zwane HP, Zwane N. Difference in mortality among individuals admitted to hospital with COVID-19 during the first and second waves in South Africa: a cohort study. Lancet Glob Health [Internet]. 2021 Jul 9 [cited 2025 Dec 3];9(9):e1216-e1225. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2214109X21002898 doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00289-8

- World Health Organization. Timeline: WHO’s COVID-19 response [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2025 [cited 2025 Dec 3]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactive-timeline#category-Science

- Sohrabi C, Alsafi Z, O’Neill N, Khan M, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, Agha R. World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int J Surg [Internet]. 2020 Feb 26 [cited 2025 Dec 3];76:71-76. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1743919120301977 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034

- Basu A. Estimating the infection fatality rate among symptomatic COVID-19 cases in the United States: study estimates the COVID-19 infection fatality rate at the US county level. Health Aff (Millwood) [Internet]. 2020 Jul 1 [cited 2025 Dec 3];39(7):1229-1236. Available from: http://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00455 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00455

- Fan G, Yang Z, Lin Q, Zhao S, Yang L, He D. Decreased case fatality rate of COVID-19 in the second wave: a study in 53 countries or regions. Transbound Emerg Dis [Internet]. 2021 Mar [cited 2025 Dec 3];68(2):213-215. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/tbed.13819 doi: 10.1111/tbed.13819

- Boum Y, Bebell LM, Bisseck ACZK. Africa needs local solutions to face the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet [Internet]. 2021 Mar 24 [cited 2025 Dec 3];397(10281):1238-1240. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673621007194 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00719-4

- Baatiema L, Sanuade OA, Allen LN, Abimbola S, Hategeka C, Koram KA, Kruk ME. Health system adaptions to improve care for people living with non-communicable diseases during COVID-19 in low-middle income countries: a scoping review. J Glob Health [Internet]. 2023 Mar 3 [cited 2025 Dec 3];13:06006. Available from: https://jogh.org/2023/jogh-13-06006 doi: 10.7189/jogh.13.06006

- Moyazzem Hossain M, Abdulla F, Rahman A. Challenges and difficulties faced in low- and middle-income countries during COVID-19. Health Policy Open [Internet]. 2022 Dec [cited 2025 Dec 3];3:100082. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S259022962200017X doi: 10.1016/j.hpopen.2022.100082

- Albitar O, Ballouze R, Ooi JP, Sheikh Ghadzi SM. Risk factors for mortality among COVID-19 patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract [Internet]. 2020 Aug [cited 2025 Dec 3];166:108293. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0168822720305453 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108293

- Carvalho VP, Pontes JPJ, Neto DRDB, Borges CER, Campos GRL, Ribeiro HLS, Amaral WND. Mortality and associated factors in patients with COVID-19: cross-sectional study. Vaccines (Basel) [Internet]. 2022 Dec 28 [cited 2025 Dec 3];11(1):71. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/11/1/71 doi: 10.3390/vaccines11010071

- Damayanthi HDWT, Prabani KIP, Weerasekara I. Factors associated for mortality of older people with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gerontol Geriatr Med [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Dec 3];7:23337214211057392. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/23337214211057392 doi: 10.1177/23337214211057392

- Kim L, Garg S, O’Halloran A, Whitaker M, Pham H, Anderson EJ, Armistead I, Bennett NM, Billing L, Como-Sabetti K, Hill M, Kim S, Monroe ML, Muse A, Reingold AL, Schaffner W, Sutton M, Talbot HK, Torres SM, Yousey-Hindes K, Holstein R, Cummings C, Brammer L, Hall AJ, Fry AM, Langley GE. Risk factors for intensive care unit admission and in-hospital mortality among hospitalized adults identified through the US Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)-Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET). Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2021 May 4 [cited 2025 Dec 3];72(9):e206-e214. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/72/9/e206/5872581 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1012

- Bryan A, Pepper G, Wener MH, Fink SL, Morishima C, Chaudhary A, Jerome KR, Mathias PC, Greninger AL. Performance characteristics of the Abbott Architect SARS-CoV-2 IgG assay and seroprevalence in Boise, Idaho. J Clin Microbiol [Internet]. 2020 Jul 23 [cited 2025 Dec 3];58(8):e00941-20. Available from: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/JCM.00941-20 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00941-20

- Mwananyanda L, Gill CJ, MacLeod W, Kwenda G, Pieciak R, Mupila Z, Lapidot R, Mupeta F, Forman L, Ziko L, Etter L, Thea D. COVID-19 deaths in Africa: prospective systematic postmortem surveillance study. BMJ [Internet]. 2021 Feb 17 [cited 2025 Dec 3];372:n334. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmj.n334 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n334

- Colombo S, Scuccato R, Fadda A, Cumbi AJ. COVID-19 in Africa: the little we know and the lot we ignore. E&P [Internet]. 2020 Dec [cited 2025 Dec 3];44(5-6 Suppl 2):408-422. Available from: https://epiprev.it/interventi/covid-19-in-africa-the-little-we-know-and-the-lot-we-ignore doi: 10.19191/EP20.5-6.S2.146

- George JA, Maphayi MR, Pillay T. COVID-19 and vulnerable populations in sub-Saharan Africa. In: Guest PC, editor. Clinical, biological and molecular aspects of COVID-19. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 147-162 [cited 2025 Dec 3]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-59261-5_13 doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-59261-5_13

- Gilmore AB, Fabbri A, Baum F, Bertscher A, Bondy K, Chang HJ, Demaio S, Erzse A, Freudenberg N, Friel S, Hofman KJ, Johns P, Abdool Karim S, Lacy-Nichols J, De Carvalho CMP, Marten R, McKee M, Petticrew M, Robertson L, Tangcharoensathien V, Thow AM. Defining and conceptualising the commercial determinants of health. Lancet [Internet]. 2023 Mar 23 [cited 2025 Dec 3];401(10383):1194-1213. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673623000132 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00013-2

- Salyer SJ, Maeda J, Sembuche S, Kebede Y, Tshangela A, Moussif M, Ihekweazu C, Mayet N, Abate E, Ouma AO, Nkengasong J. The first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa: a cross-sectional study. Lancet [Internet]. 2021 Mar 24 [cited 2025 Dec 3];397(10281):1265-1275. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673621006322 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00632-2

- Craig J, Kalanxhi E, Osena G, Frost I. Estimating critical care capacity needs and gaps in Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic [Internet]. medRxiv. 2020 Jun 4 [preprint] [cited 2025 Dec 3]. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.06.02.20120147 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.02.20120147

- Douin DJ, Ward MJ, Lindsell CJ, Howell MP, Hough CL, Exline MC, Gong MN, Aboodi MS, Tenforde MW, Feldstein LR, Stubblefield WB, Steingrub JS, Prekker ME, Brown SM, Peltan ID, Khan A, Files DC, Gibbs KW, Rice TW, Casey JD, Hager DN, Qadir N, Henning DJ, Wilson JG, Patel MM, Self WH, Ginde AA. ICU bed utilization during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in a multistate analysis—March to June 2020. Crit Care Explor [Internet]. 2021 Mar 12 [cited 2025 Dec 3];3(3):e0361. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/ccejournal/fulltext/2021/03000/icu_bed_utilization_during_the_coronavirus_disease.1.aspx doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000361

- Fanning JP, Weaver N, Fanning RB, Griffee MJ, Cho SM, Panigada M, Obonyo NG, Zaaqoq AM, Rando H, Chia YW, Fan BE, Sela D, Chiumello D, Coppola S, Labib A, Whitman GJR, Arora RC, Kim BS, Motos A, Torres A, Barbé F, Grasselli G, Zanella A, Etchill E, Usman AA, Feth M, White NM, Suen JY, Li Bassi G, Peek GJ, Fraser JF, Dalton H. Hemorrhage, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, and thrombosis complications among critically ill patients with COVID-19: an international COVID-19 critical care consortium study. Crit Care Med [Internet]. 2023 May [cited 2025 Dec 3];51(5):619-631. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/ccmjournal/Abstract/2023/05000/Hemorrhage,_Disseminated_Intravascular.13.aspx doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005798

- Riziki Ghislain M, Muzumbukilwa WT, Magula N. Risk factors for death in hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) [Internet]. 2023 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Dec 3];102(35):e34405. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/md-journal/fulltext/2023/09010/Risk_factors_for_death_in_hospitalized_COVID_19.1.aspx doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000034405

- Bepouka B, Mayasi N, Mandina M, Longokolo M, Odio O, Mangala D, Mbula M, Kayembe JM, Situakibanza H. Risk factors for mortality in COVID-19 patients in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One [Internet]. 2022 Oct 17 [cited 2025 Dec 3];17(10):e0276008. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0276008 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0276008