Research | Open Access | Volume 9 (1): Article 06 | Published: 08 Jan 2026

Epidemiology of stillbirth in the Savannah Region, Ghana, 2018-2022

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Tables

| Year | Institutional total births | Stillbirths | Stillbirth rate [95% CI] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh (%) | Macerated (%) | Total | |||

| 2018 | 12,546 | 64 (45.1) | 78 (54.9) | 142 | 11.3 [9.5 – 13.3] |

| 2019 | 13,924 | 67 (49.9) | 70 (50.1) | 137 | 9.8 [8.3 – 11.6] |

| 2020 | 14,441 | 70 (49.3) | 72 (50.7) | 142 | 9.8 [8.3 – 11.6] |

| 2021 | 15,989 | 78 (47.0) | 88 (53.0) | 166 | 10.4 [8.9 – 12.1] |

| 2022 | 16,693 | 91 (52.3) | 83 (47.7) | 174 | 10.4 [8.9 – 12.1] |

| Total | 73,593 | 370 (48.6) | 391 (51.4) | 761 | 10.3 [9.6 – 11.1] |

Table 1: Characteristics of institutional births, Savannah Region, 2018–2022

| District | Total births | Total stillbirths | Stillbirth rate [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bole | 17,294 | 106 | 6.1 [5.0 – 7.4] |

| Central Gonja | 14,685 | 111 | 7.6 [6.2 – 9.1] |

| East Gonja | 12,517 | 215 | 17.2 [15.0 – 19.6] |

| North Gonja | 5,312 | 43 | 8.1 [5.9 – 10.9] |

| North-East Gonja | 3,525 | 19 | 5.4 [3.2 – 8.4] |

| Sawla-Tuna-Kalba | 11,135 | 131 | 11.8 [9.8 – 13.9] |

| West Gonja | 9,125 | 136 | 14.9 [12.5 – 17.6] |

Table 2: Stillbirth rates by District, Savannah Region, 2018–2022

Figures

Keywords

- Stillbirth

- Savannah Region

- DHIMS

Chrysantus Kubio1,&, Williams Azumah Abanga2, Emmanuel Sukuruman Monanka1, Cynthia Kubio3, Jonas Abodoo1, Kwabena Adjei Sarfo1, Wadeyir Jonathan Abesig4, Christopher Sunkwa Tamal5, Michael Rockson Adjei5

1Savannah Regional Health Directorate, Ghana Health Service, Savannah Region, Damongo, Ghana, 2Saboba District Health Directorate, Ghana Health Service, Northern Region, Saboba, Ghana, 3Tamale Metropolitan Health Directorate, Ghana Health Service, Northern Region, Tamale, Ghana, 4Bole District Hospital, Ghana Health Service, Savannah Region, Bole, Ghana, 5WHO Country Office, Accra, Ghana

&Corresponding author: Chrysantus Kubio, Savannah Regional Health Directorate, Ghana Health Service, Savannah Region, Damongo, Ghana, Email: chryskubio@yahoo.com

Received: 21 May 2025, Accepted: 03 Jan 2026, Published: 08 Jan 2026

Domain: Maternal and Child Health

Keywords: Stillbirth, Savannah Region, DHIMS

©Chrysantus Kubio et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Chrysantus Kubio et al., Epidemiology of stillbirth in the Savannah Region, Ghana, 2018-2022. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025; 9(1):06. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00078

Abstract

Introduction: Stillbirth is an adverse pregnancy outcome and contributes significantly to poor maternal health. Globally, an estimated 1.9 million stillbirths were recorded in 2021, with 45% occurring in Sub-Saharan Africa. Substantial proportions of pregnancies in Ghana end as stillbirths, with limited information on their epidemiology in the Savannah Region. Information on the epidemiology of stillbirths will help design strategies to mitigate the burden. We determined the rate, trend and distribution of stillbirths in the Savannah Region of Ghana.

Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of institutional stillbirth data of the Savannah Region from January 2018 to December 2022. Stillbirth data was extracted from the District Health Information Management System 2 (DHIMS2) database by type, district and year of occurrence. Descriptive statistics were performed using Microsoft Excel 2016 and ArcGIS 10.4, by person, place and time with results presented in a table, graph and map.

Results: From January 2018 to December 2022, the region recorded a total of 761 stillbirths and 73,593 institutional deliveries. The overall stillbirth rate was 10.3 [95% CI: 9.6 – 11.1] per 1,000 total births. A little over half of the stillbirths were macerated, 51.4% (391/761). The trend of stillbirth was generally stable over the study period, ranging from 9.8/1,000 [95% CI: 8.3 – 11.6] in 2019 and 2020 to 11.3/1,000 [95% CI: 9.5 – 13.3] in 2018. All seven districts in the region recorded stillbirths, with the district-level rate varying between 5.4 and 17.2 stillbirths per 1,000 births in North-East Gonja District and East Gonja Municipal, respectively.

Conclusion: Based on the available data, the stillbirth rate in the Savannah Region was low, with a little over half being macerated. There was no substantial change in the trend of stillbirth over the study period. The East Gonja Municipality recorded the highest stillbirth rate. Further studies and interventions are required to address the disparities and reduce the burden to an acceptable minimum.

Introduction

Stillbirth is a fetal death occurring after 28 completed weeks of gestation [1]. However, fetal death at 20 or 22 weeks of gestation or longer, as defined by the International Classification of Diseases, version 10 and 11, respectively, has been used by some countries as the threshold for stillbirths [2]. The varied classification highlights the potential of underestimating stillbirth rates [3]. The occurrence of stillbirth is an adverse pregnancy outcome and contributes significantly to poor maternal health [4]. Globally, an estimated 1.9 million stillbirths were reported in 2021, with the highest burden reported in low-income countries and 45% of stillbirths occurring in Sub-Saharan Africa [5, 6]. Women and their families have devastating psycho-social experiences due to the occurrence of stillbirths [7].

Stillbirths are caused by childbirth complications, maternal infections in pregnancy, maternal disorders such as pre-eclampsia and diabetes, fetal growth restriction and congenital abnormalities [8, 9]. Inadequate health infrastructure and poor access to essential obstetric care significantly influence the occurrence of stillbirths [5, 10]. Proven interventions and health services, such as early initiation of antenatal care and skilled delivery, are vital in preventing stillbirths [4, 11, 12]. Meanwhile, the estimated global stillbirth rate of 14 per 1,000 births in 2021 [6] is higher than the World Health Organization (WHO) “Every Newborn: An Action Plan To End Preventable Deaths” target to reduce the stillbirth rate to 12 or fewer per 1000 births by 2030 [1]. Also, there is a high reported stillbirth rate of 21.7 to 23.0 per 1,000 births in Africa [13, 14]. Stillbirths are reported to have generally declined over the decades [6, 15], whilst a study in Cambodia found an increasing stillbirth rate [16]. Various studies have indicated geospatial variations in the occurrence of stillbirths, with observed low and high rates [17–19].

In Ghana, despite the implementation and scale-up of the Community-based Health Planning and Services (CHPS) concept aimed at improving maternal health outcomes through increasing access to antenatal care and skilled delivery, substantial proportions of pregnancies end as stillbirths [8]. Even though a study in the West Gonja Municipal Hospital estimated the average stillbirth rate from 2009 to 2013 as 33.2 per 1,000 births [20], there is limited information on the overall rate, trend and geographical distribution of stillbirth in the newly created Savannah Region. Information on the epidemiology will help evaluate the effectiveness of maternal health interventions implemented over the years and also design strategies to mitigate the occurrence of stillbirths. This study determined the overall rate, trend and distribution of stillbirths in the Savannah Region of Ghana from 2018 to 2022.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a secondary data analysis of the institutional stillbirth data in the Savannah Region from January 2018 to December 2022. The study was conducted in the Savannah Region of Ghana. The region has a projected population of 653,266 for 2022, with an estimated 26,131 expectant pregnancies. The region accounts for approximately 15% of the geographic land size of the country. Administratively, the region has two municipalities and five districts [21]. The majority of residents dwell in rural small communities, with distances between these communities far apart, hampering health outreach services. Most roads are impassable during the rainy season, affecting health delivery. The White and Black Volta Rivers, with their tributaries, run through the region, creating hard-to-reach communities [22]. There are five hospitals, three polyclinics with 23 health centers and 148 CHPS compounds in the region [23].

Data source

Stillbirth data were extracted from the District Health Information Management System 2 (DHIMS2) database. DHIMS2 is a web-based platform used by the Ghana Health Service to capture data on disease conditions and health events that were reported at the health facilities in the region. Births, including stillbirths occurring at health facilities, are documented in the delivery registers. They are collected, collated and entered into the DHIMS2 through the monthly Midwifery reporting form (Form A). Studies have indicated that DHIMS2 data completeness and accuracy for maternal health services in Ghana exceed 90% [24, 25]. The DHIMS2 database captures aggregated data, which does not include individual identifiers. The database pre-categorizes stillbirths into macerated and fresh. The total births and stillbirths were retrieved using the pivot table function of the database. Births, type of stillbirth (macerated and fresh), district of location of the facility reporting and year stillbirths occurred were the available variables in the DHIMS2 abstracted.

Definition of terms

Fresh stillbirth: A stillbirth in which the foetus is delivered with intact skin, suggesting that a heartbeat was present before the onset of labour and death occurred in the course of labour. This classification was done by midwives, nurses and doctors who attended to pregnant women during delivery.

Macerated stillbirth: Stillbirth with signs of skin degeneration, suggesting foetal heart sound was absent at the onset of labour and death occurred in the antepartum period.

Data analysis

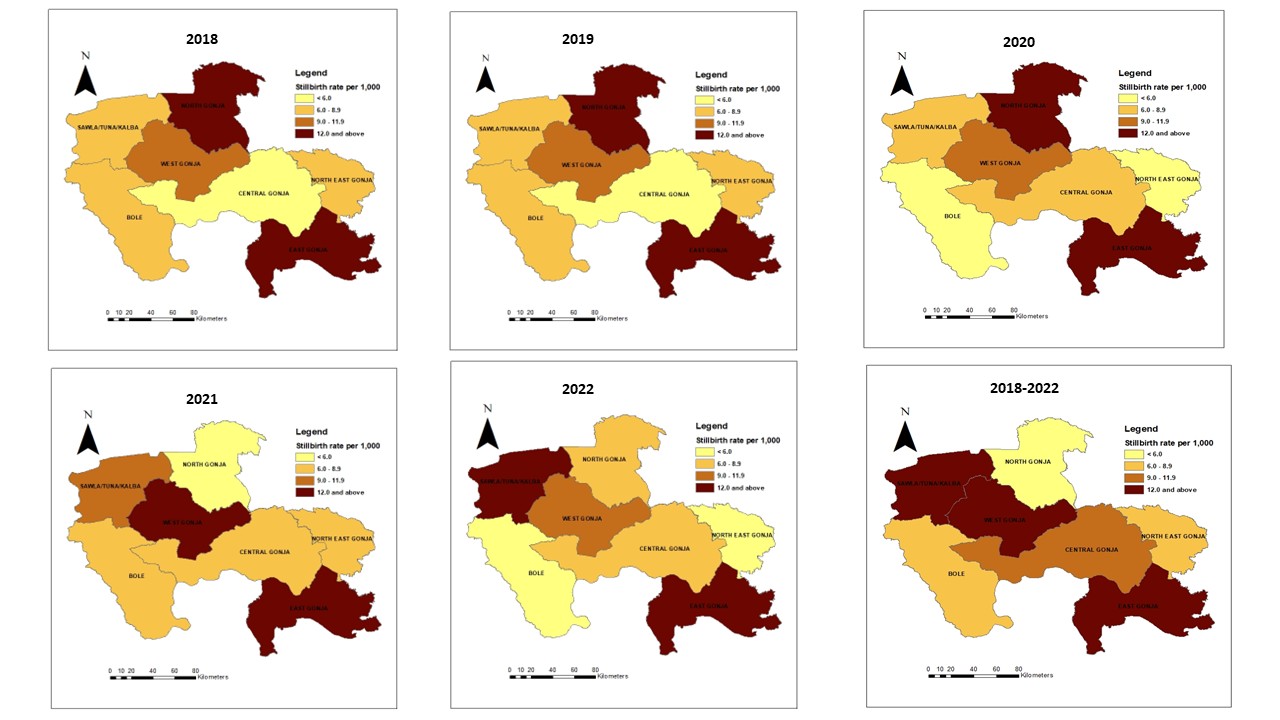

Descriptive statistics were performed using Microsoft Excel 2016 and ArcGIS 10.4 by person, place and time. The stillbirth rate was calculated by dividing the total institutional stillbirths by the total institutional births per 1,000 births. The overall stillbirth rate was calculated by dividing the institutional stillbirths by the total institutional births over the study period per 1,000 births. A choropleth map was generated using ArcGIS to display the geographical disparities of stillbirths in the region. The district shapefiles were obtained from the Ghana Demographic and Health Survey reports. We linked the district names and estimated the stillbirth rate to the shapefiles using the join tool of the ArcGIS. Furthermore, the symbology tool was used to show the estimated stillbirth rate using graduated colour. The results were presented in frequencies, proportions and rates using tables, graphs and maps.

Ethics approval

The Ghana Health Service (GHS) routinely reports stillbirth as part of the Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response using de-identified data. This aligns with Ghana’s Public Health Act, 2012, which mandates the GHS to maintain and update surveillance data on diseases and public health events. Since aggregated secondary data were used for the analysis, no formal ethical approval was required for this study. However, we obtained administrative approval from the Savannah Regional Health Directorate to access the dataset and use it for this study.

Results

Over the study period, 73,593 institutional births were recorded in the Savannah Region, of which 761 were stillbirths. The overall stillbirth rate was 10.3 stillbirths per 1,000 total births. A little over half of the stillbirths were macerated, 51.4% (391/761) (Table 1).

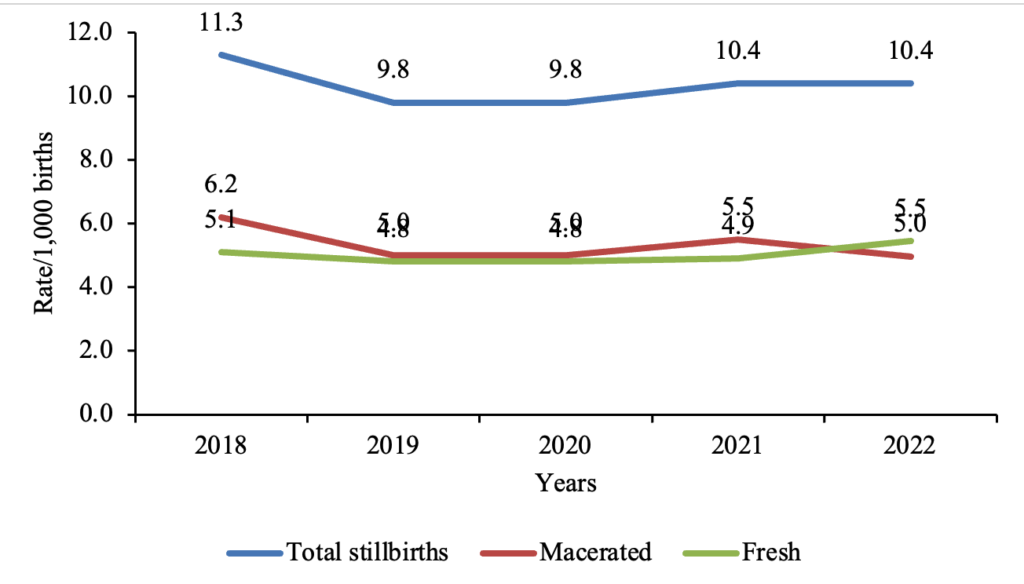

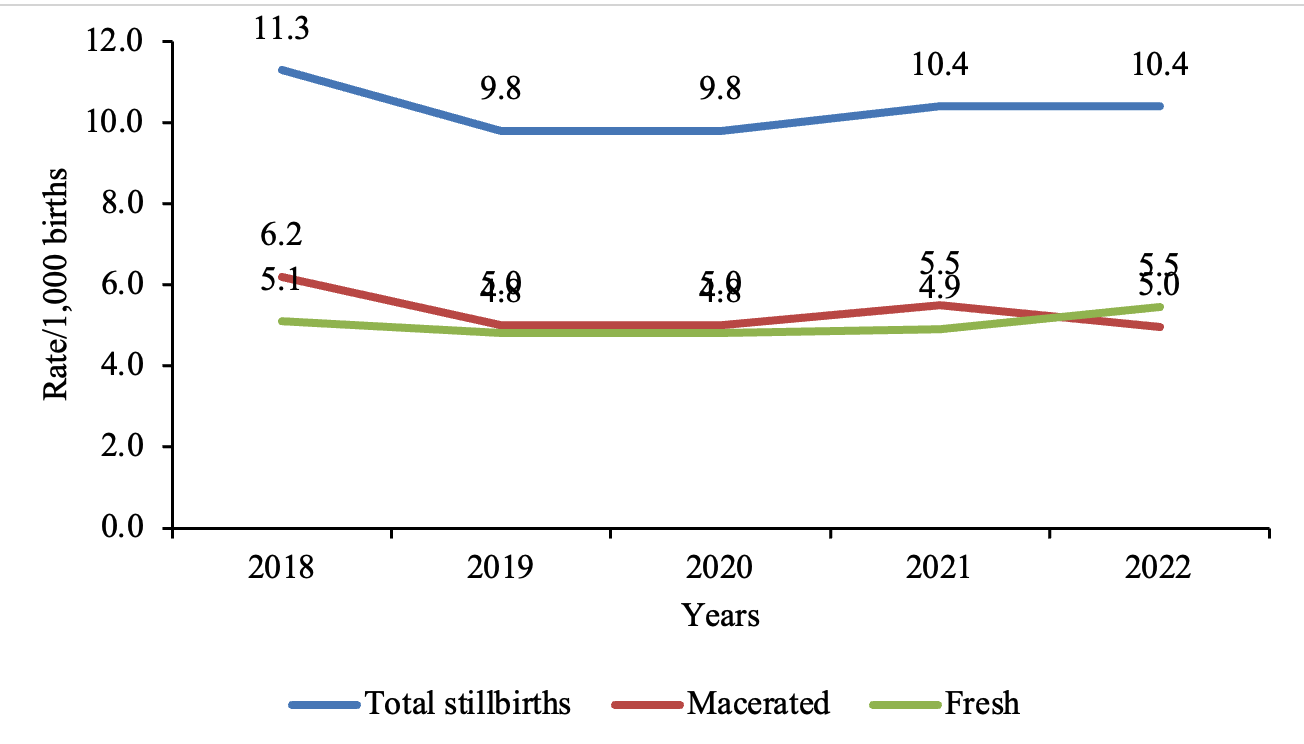

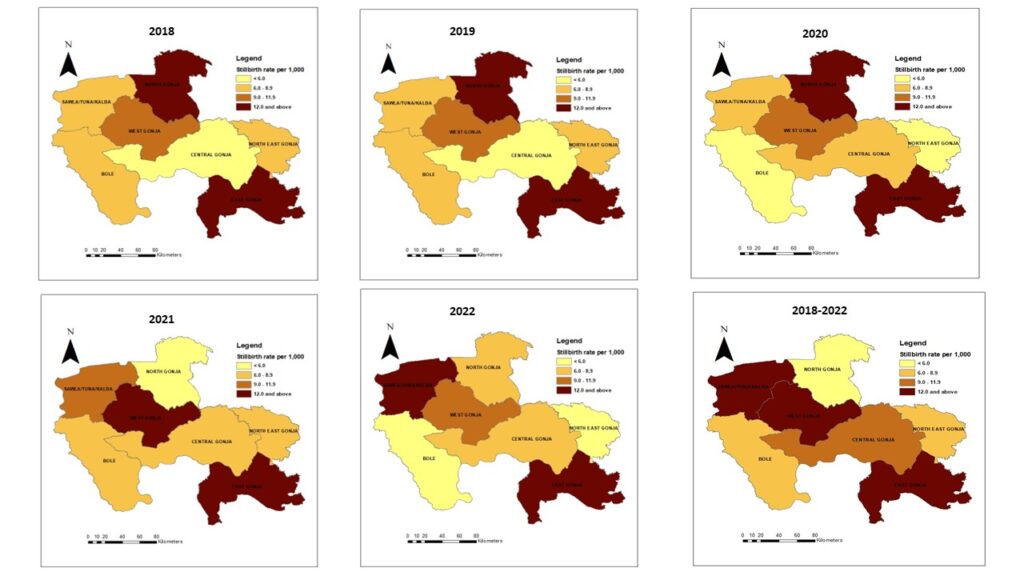

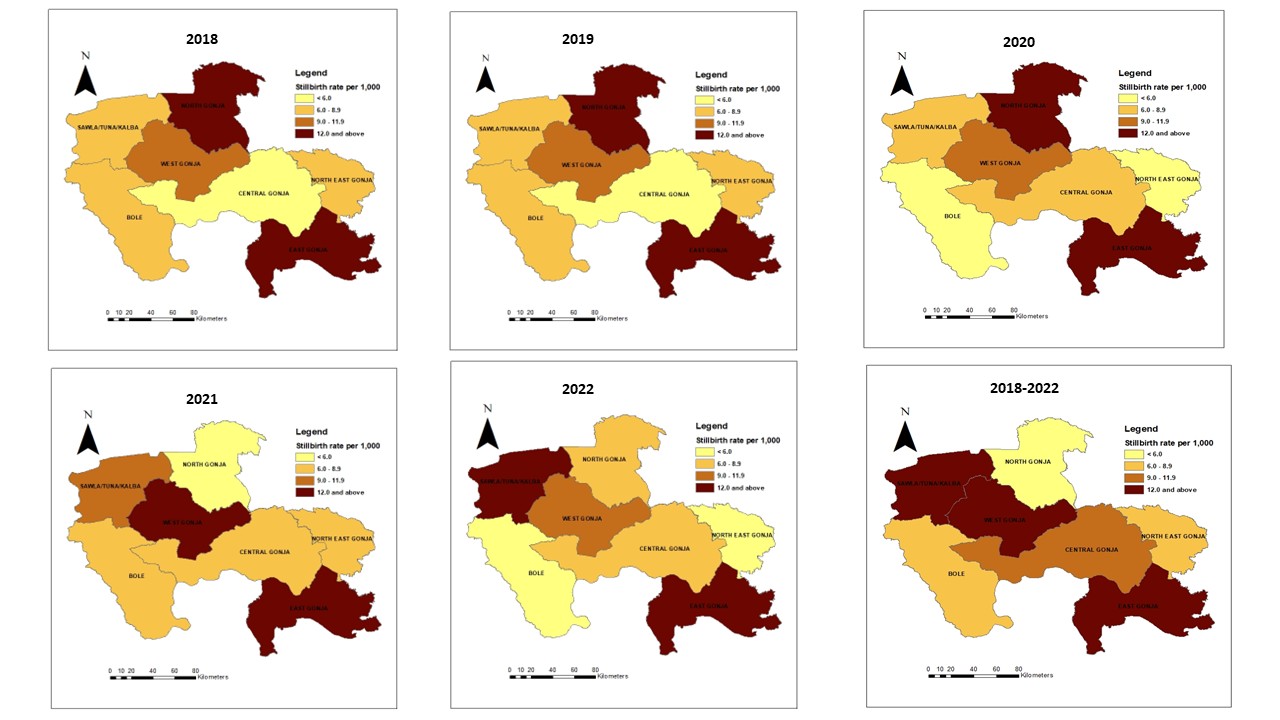

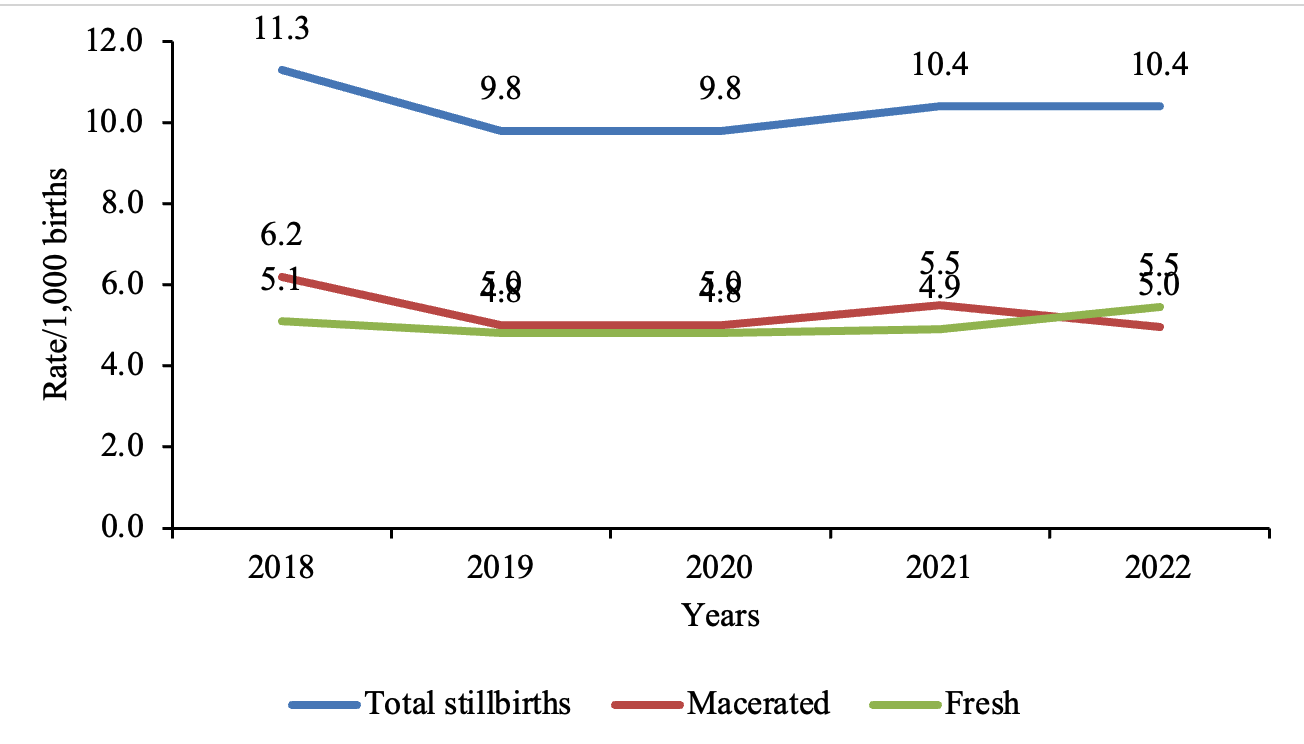

The stillbirth rate marginally decreased from 11.3/1,000 [95% CI: 9.5 – 13.3] births in 2018 to 10.4/1,000 [95% CI: 8.9 – 12.1] births in 2022 (Table 2). There were no substantial changes in the stillbirth rate in the region (Figure 1). Stillbirths occurred in all seven districts of the Savannah Region. The district-level rate varied between 5.4 and 17.2 stillbirths per 1,000 births in the North-East Gonja District and East Gonja Municipality, respectively (Figure 2).

Discussion

The study analyzed institutional stillbirth data in the Savannah Region over five years. The regional cumulative stillbirth rate was low and marginally decreased over the study period, with observed geographical variations.

The observed regional stillbirth rate was lower than the national and SDGs target of 12 or fewer stillbirths per 1,000 births. The general improvement in the coverage of maternal health services, in which 95.1% of pregnant women receive antenatal care from trained doctors, nurses and midwives, with 79.5% attending antenatal clinics at least four times and 70.6% delivering at health facilities [26] may have contributed to the low stillbirth rate in the Savannah Region. The expansion in CHPS compounds over the past years [23] may have increased access to these essential maternal health services in rural communities, thereby influencing the low stillbirth rates recorded at health facilities. This finding from this study differs from the high stillbirth rates of 27, 33 and 34 per 1,000 births reported at Municipal Hospitals in Hohoe [27], West Gonja [20], and Kassena-Nankana Districts [15], respectively, in Ghana. The Ghana Demographic and Health Survey reported national and Savannah Region stillbirth rates of 15 and 14 per 1,000, respectively [26] are higher than the findings of this study. Additionally, findings from six low-resource countries [17], Ethiopia [28] and Nigeria [29] reported high stillbirth rates of 28, 92 and 55 per 1,000, respectively. The difference in study periods may have accounted for the variations in the observed stillbirth rates. The use of the most current data for our analysis may be an indication of increasing improvement in quality obstetric care services over the past five years. Furthermore, the socio-demographic, economic and cultural changes over the study period could have contributed to the differences in the magnitude of stillbirths recorded.

Our study revealed that a little over half of the stillbirths in the Savannah Region were macerated. This is consistent with the global report that more than half of stillbirths (55%) are macerated [6] and a community-based cohort study across 11 Sub-Saharan African and South Asian countries, which also revealed that 56% of stillbirths were macerated [30]. The high occurrence of macerated stillbirths may be due to a lack of or inadequate modern equipment, such as ultrasound machines, at lower-level health facilities to effectively screen and monitor intrauterine foetal growth for the institution of appropriate interventions, where necessary [31, 32]. However, health facility-based studies in Ghana (West Gonja Municipal and War Memorial Hospitals) [15, 20] and population-based studies in India [33], Bangladesh [34] and seven other resource-limited countries [17] found that the majority of stillbirths were fresh. The varying data sources and datasets used may have influenced the disparities in the type of stillbirths in these studies. Whereas our study used aggregated data reported in DHIMS2, the studies in Ghana reviewed delivery records of women at the hospital-level. This may have accounted for the variations in the proportions of fresh and macerated stillbirths. Also, the use of verbal autopsy and interviews at the community-level could have contributed to observed disparities in the type of stillbirth in population-based studies.

From this study in the Savannah Region, there is generally no substantial change in the trend of stillbirths over the study period. This finding is contrary to observations of a study conducted in Navrongo, which reported the declining trend of stillbirths [15]. Findings in the West Gonja District [20] and Cambodia documented an increasing rate of stillbirth [16]. This finding suggests that local health authorities need to design strategies and interventions to ensure a stable decline in the stillbirth cases.

Stillbirths were heterogeneously distributed in the Savannah Region, with the highest stillbirth rate recorded in the East Gonja District. The hard-to-reach communities in the East Gonja Municipality impede access to antenatal care and timely arrival in health facilities during labour. These may have contributed to the recorded high stillbirths. In addition, the referral of pregnancy and labour complications from the North East Gonja District in the Savannah Region, and parts of the Northern Region (Kpandai and Nanumba North Districts) for care in the East Gonja Municipality may have accounted for the observed high stillbirth rate in that district. This finding corroborates other secondary data analysis findings in India [19], Ethiopia [18] and a multi-country population-based study [17] which showed geospatial variations of stillbirth rates with reported high-rate clusters. This suggests an uneven access to essential obstetric health services, such as antenatal care and skilled delivery in impoverished settings [35].

Strengths and limitations

This study offers important information on the stillbirth burden in the Savannah Region, contributing to the understanding of this maternal and child health issue. However, the study included only pregnant women who delivered at health facilities in the region. All facilities in the region, both public and private, that provide maternal health services reports in the DHIMS2, recorded over 90% completeness for the study period [23]. Meanwhile, the monthly midwifery reporting form, the source of data used for the analysis, does not capture data on stillbirths that occur at home. Therefore, these could potentially lead to an underestimation of the stillbirth rate. Furthermore, the DHIMS2 has limited obstetric and demographic data. In addition, there is no data on stillbirths by gestational age, sex, or other important background characteristics. These restricted the scope of the analysis. Despite these limitations, the study provides baseline information on the stillbirth burden in the newly created Savannah Region for informed decision-making and planning of maternal health activities. It also highlights the usefulness of DHIMS2 as a crucial source of data for monitoring stillbirths and guiding interventions to mitigate stillbirths in the region.

Conclusion

Based on the available data, the stillbirth rate in the Savannah Region was low, with a little over half being macerated. There was no substantial change in the trend of stillbirth over the study period. The East Gonja Municipality recorded the highest stillbirth rate. Whilst further studies are required to identify the health system and community factors associated with the disparities in the burden of stillbirth in the region, the Regional Reproductive Health Unit should intensify efforts to improve coverage of essential maternal health services such as early initiation and consistent antenatal clinic visits, and skilled delivery. Health education and promotion campaigns should be strengthened in various communities to encourage good practices to prevent infections and illnesses during pregnancy, and to reduce the occurrences of antepartum stillbirths. There is a need to review the DHIMS2 database to collect obstetric information, including previous pregnancy outcomes, infections and diseases during pregnancy. These variables are enormous for designing public health interventions and strategies to help mitigate stillbirths. Further research may be conducted to estimate the true burden of stillbirth in the region and examine the risk factors associated with stillbirth in East Gonja Municipality.

What is already known about the topic

- Women and their families have devastating psycho-social experiences due to the occurrence of stillbirths.

- Inadequate health infrastructure and poor access to essential obstetric care significantly influence the occurrence of stillbirths.

- The highest burden of stillbirths occurs in resource-limited settings.

What this study adds

- The stillbirth rate in the Savannah Region was 10.3 per 1,000 births.

- Most of the stillbirths recorded were macerated.

- East Gonja Municipal recorded the highest stillbirth rate of 2 per 1,000 births.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the Savannah Regional Health Directorate for granting administrative permission to access the DHIMS data for the study. The authors are also grateful to the District Health Directorates and heads of health facilities for their role in data collation and entry into DHIMS.

| Year | Institutional total births | Stillbirths | Stillbirth rate [95% CI] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh (%) | Macerated (%) | Total | |||

| 2018 | 12,546 | 64 (45.1) | 78 (54.9) | 142 | 11.3 [9.5 – 13.3] |

| 2019 | 13,924 | 67 (49.9) | 70 (50.1) | 137 | 9.8 [8.3 – 11.6] |

| 2020 | 14,441 | 70 (49.3) | 72 (50.7) | 142 | 9.8 [8.3 – 11.6] |

| 2021 | 15,989 | 78 (47.0) | 88 (53.0) | 166 | 10.4 [8.9 – 12.1] |

| 2022 | 16,693 | 91 (52.3) | 83 (47.7) | 174 | 10.4 [8.9 – 12.1] |

| Total | 73,593 | 370 (48.6) | 391 (51.4) | 761 | 10.3 [9.6 – 11.1] |

| District | Total births | Total stillbirths | Stillbirth rate [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bole | 17,294 | 106 | 6.1 [5.0 – 7.4] |

| Central Gonja | 14,685 | 111 | 7.6 [6.2 – 9.1] |

| East Gonja | 12,517 | 215 | 17.2 [15.0 – 19.6] |

| North Gonja | 5,312 | 43 | 8.1 [5.9 – 10.9] |

| North-East Gonja | 3,525 | 19 | 5.4 [3.2 – 8.4] |

| Sawla-Tuna-Kalba | 11,135 | 131 | 11.8 [9.8 – 13.9] |

| West Gonja | 9,125 | 136 | 14.9 [12.5 – 17.6] |

References

- WHO, UNICEF. Every newborn: An action plan to end preventable deaths [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2014 Jun 24 [cited 2026 Jan 8]. Available from: https://www.who.int/initiatives/every-newborn-action-plan

- WHO. ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2023 [cited 2026 Jan 8]. Available from: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en

- GBD 2021 Global Stillbirths Collaborators. Global, regional, and national stillbirths at 20 weeks’ gestation or longer in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2021: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 [Internet]. The Lancet. 2024 Nov [cited 2026 Jan 8];404(10466):1955–88. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(24)01925-1/fulltext doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01925-1

- WHO. Improving maternal and newborn health and survival and reducing stillbirth – Progress report 2023 [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2023 May 9 [cited 2026 Jan 8]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240073678

- Reinebrant HE, Leisher SH, Coory M, Henry S, Wojcieszek AM, Gardener G, Lourie R, Ellwood D, Teoh Z, Allanson E, Blencowe H, Draper ES, Erwich JJ, Frøen JF, Gardosi J, Gold K, Gordijn S, Gordon A, Heazell AEP, Khong TY, Korteweg F, Lawn JE, McClure EM, Oats J, Pattinson R, Pettersson K, Siassakos D, Silver RM, Smith GCS, Tunçalp Ö, Flenady V. Making stillbirths visible: a systematic review of globally reported causes of stillbirth [Internet]. BJOG. 2018 Jan [cited 2026 Jan 8];125(2):212–24. Available from: https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.14971 doi:10.1111/1471-0528.14971

- UNICEF. Never Forgotten: The situation of stillbirth around the globe [Internet]. New York (NY): UNICEF; 2023 Jan 09 [cited 2026 Jan 8]. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/resources/never-forgotten-stillbirth-estimates-report/

- Heazell AEP, Siassakos D, Blencowe H, Burden C, Bhutta ZA, Cacciatore J, Dang N, Das J, Flenady V, Gold KJ, Mensah OK, Millum J, Nuzum D, O’Donoghue K, Redshaw M, Rizvi A, Roberts T, Saraki HET, Storey C, Wojcieszek AM, Downe S. Stillbirths: economic and psychosocial consequences [Internet]. The Lancet. 2016 Feb [cited 2026 Jan 8];387(10018):604–16. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(15)00836-3/fulltext doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00836-3

- Ahinkorah BO, Seidu AA, Ameyaw EK, Budu E, Bonsu F, Mwamba B. Beyond counting induced abortions, miscarriages and stillbirths to understanding their risk factors: analysis of the 2017 Ghana maternal health survey [Internet]. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 8];21(1):140. Available from: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-021-03633-8 doi:10.1186/s12884-021-03633-8

- Page JM, Bardsley T, Thorsten V, Allshouse AA, Varner MW, Debbink MP, Dudley DJ, Saade GR, Goldenberg RL, Stoll B, Hogue CJ, Bukowski R, Conway D, Reddy UM, Silver RM. Stillbirth associated with infection in a diverse U.S. Cohort [Internet]. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2019 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 8];134(6):1187–96. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/fulltext/2019/12000/stillbirth_associated_with_infection_in_a_diverse.6.aspx doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003515

- McClure EM, Garces A, Saleem S, Moore JL, Bose CL, Esamai F, Goudar SS, Chomba E, Tshefu A, Patel A, Tikmani SS, Krebs NF, Derman R, Hibberd PL, Carlo WA, Koso-Thomas M, Liechty EA, Goldenberg RL. Global Network for Women’s and Children’s Health Research: probable causes of stillbirth in low- and middle-income countries using a prospectively defined classification system [Internet]. BJOG. 2018 Jan [cited 2026 Jan 8];125(2):131–138. Available from: https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.14493 doi:10.1111/1471-0528.14493

- The Lancet. Ending preventable stillbirths: an Executive Summary for The Lancet’s Series [Internet]. London (UK): Lancet; 2016 Jan [cited 2026 Jan 8]:1–8. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/pb/assets/raw/Lancet/stories/series/stillbirths2016-exec-summ.pdf

- Wastnedge E, Waters D, Murray SR, McGowan B, Chipeta E, Nyondo-Mipando AL, Gadama L, Gadama G, Masamba M, Malata M, Taulo F, Dube Q, Kawaza K, Khomani PM, Whyte S, Crampin M, Freyne B, Norman JE, Reynolds RM; Diammo Collaboration. Interventions to reduce preterm birth and stillbirth, and improve outcomes for babies born preterm in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review [Internet]. J Glob Health. 2021 Dec 30 [cited 2026 Jan 8];11:04050. Available from: https://jogh.org/documents/2021/jogh-11-04050.pdf doi:10.7189/jogh.11.04050

- Adeyinka DA, Olakunde BO, Muhajarine N. Evidence of health inequity in child survival: spatial and Bayesian network analyses of stillbirth rates in 194 countries [Internet]. Sci Rep. 2019 Dec 24 [cited 2026 Jan 8];9(1):19755. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-56326-w doi:10.1038/s41598-019-56326-w

- Hug L, You D, Blencowe H, Mishra A, Wang Z, Fix MJ, Wakefield J, Moran AC, Gaigbe-Togbe V, Suzuki E, Blau DM, Cousens S, Creanga A, Croft T, Hill K, Joseph KS, Maswime S, McClure EM, Pattinson R, Pedersen J, Smith LK, Zeitlin J, Alkema L. Global, regional, and national estimates and trends in stillbirths from 2000 to 2019: a systematic assessment [Internet]. The Lancet. 2021 Aug [cited 2026 Jan 8];398(10302):772–85. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(21)01112-0/fulltext doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01112-0

- Nonterah EA, Agorinya IA, Kanmiki EW, Kagura J, Tamimu M, Ayamba EY, Nonterah EW, Kaburise MB, Al-Hassan M, Ofosu W, Oduro AR, Awonoor-Williams JK. Trends and risk factors associated with stillbirths: A case study of the Navrongo War Memorial Hospital in Northern Ghana [Internet]. PLoS ONE. 2020 Feb 21 [cited 2026 Jan 8];15(2):e0229013. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0229013 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0229013

- Christou A, Mbishi J, Matsui M, Beňová L, Kim R, Numazawa A, Iwamoto A, Sokhan S, Ieng N, Delvaux T. Stillbirth rates and their determinants in a national maternity hospital in Phnom Penh, Cambodia in 2017–2020: a cross-sectional assessment with a nested case–control study [Internet]. Reprod Health. 2023 Oct 21 [cited 2026 Jan 8];20(1):157. Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-023-01703-y doi:10.1186/s12978-023-01703-y

- McClure EM, Garces A, Goudar SS, Saleem S, Esamai F, Patel A, Tikmani SS, Mwenechanya M, Chomba E, Lokangaka A, Bose CL, Bucher S, Liechty EA, Krebs NF, Yogesh Kumar S, Derman RJ, Hibberd PL, Carlo WA, Moore JL, Nolen TL, Koso-Thomas M, Goldenberg RL. Stillbirth 2010–2018: a prospective, population-based, multi-country study from the Global Network [Internet]. Reprod Health. 2020 Nov [cited 2026 Jan 8];17(S2):146. Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-020-00991-y doi:10.1186/s12978-020-00991-y

- Tesema GA, Gezie LD, Nigatu SG. Spatial distribution of stillbirth and associated factors in Ethiopia: a spatial and multilevel analysis [Internet]. BMJ Open. 2020 Oct [cited 2026 Jan 8];10(10):e034562. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/10/10/e034562 doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034562

- Islam DB, Purbey A, Choudhury DR, Lahariya C, Agnihotri SB. Seasonal and district level geo-spatial variations in stillbirth rates in India: an analysis of secondary data [Internet]. Indian J Pediatr. 2023 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 8];90(S1):47–53. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12098-023-04711-9 doi:10.1007/s12098-023-04711-9

- Der EM, Sutaa F, Azongo TB, Kubio C. Stillbirths at the West Gonja Hospital in northern Ghana [Internet]. J Med Biomed Sci. 2016 May 30 [cited 2026 Jan 8];5(1):1–7. Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/jmbs/article/view/136412 doi:10.4314/jmbs.v5i1.1

- Ghana Statistical Service. Ghana 2021 Population and Housing Census: General Report Volume 3A [Internet]. Accra (Ghana): Ghana Statistical Service; 2021 [cited 2026 Jan 8]:1-128. Available from: https://statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/fileUpload/pressrelease/2021%20PHC%20General%20Report%20Vol%203A_Population%20of%20Regions%20and%20Districts_181121.pdf

- Ghana Health Service. Profile- Savannah Region [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2026 Jan 8]. Available from: https://ghs.gov.gh/profile-savannah-region/

- Savannah Regional Health Directorate (Ghana). Savannah Regional Health Directorate Annual Report [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2026 Jan 8].

- Amoakoh-Coleman M, Kayode GA, Brown-Davies C, Agyepong IA, Grobbee DE, Klipstein-Grobusch K, Ansah EK. Completeness and accuracy of data transfer of routine maternal health services data in the greater Accra region [Internet]. BMC Res Notes. 2015 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 8];8(1):114. Available from: https://bmcresnotes.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13104-015-1058-3 doi:10.1186/s13104-015-1058-3

- Lasim OUL, Ansah EW, Apaak D. Maternal and child health data quality in health care facilities at the Cape Coast Metropolis, Ghana [Internet]. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022 Aug 30 [cited 2026 Jan 8];22(1):1102. Available from: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-022-08449-6 doi:10.1186/s12913-022-08449-6

- Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), ICF. Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2022 [Internet]. Accra (Ghana): Ghana Statistical Service (GSS); 2024 Jan [cited 2026 Jan 8]. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR387/FR387.pdf

- Agbozo F, Abubakari A, Der J, Jahn A. Prevalence of low birth weight, macrosomia and stillbirth and their relationship to associated maternal risk factors in Hohoe Municipality, Ghana [Internet]. Midwifery. 2016 Sept [cited 2026 Jan 8];40:200–6. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0266613816301061 doi:10.1016/j.midw.2016.06.016

- Mengesha S, Dangisso MH. Burden of stillbirths and associated factors in Yirgalem Hospital, Southern Ethiopia: a facility based cross-sectional study [Internet]. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 8];20(1):591. Available from: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-020-03296-x doi:10.1186/s12884-020-03296-x

- Dase E, Wariri O, Onuwabuchi E, Alhassan JAK, Jalo I, Muhajarine N, Okomo U, El Nafaty AU. Applying the WHO ICD-PM classification system to stillbirths in a major referral Centre in Northeast Nigeria: a retrospective analysis from 2010-2018 [Internet]. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 8];20(1):383. Available from: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-020-03059-8 doi:10.1186/s12884-020-03059-8

- Ahmed I, Ali SM, Amenga-Etego S, Ariff S, Bahl R, Baqui AH, Begum N, Bhandari N, Bhatia K, Bhutta ZA, Biemba G, Deb S, Dhingra U, Dube B, Dutta A, Edmond K, Esamai F, Fawzi W, Ghosh AK, Gisore P, Grogan C, Hamer DH, Herlihy J, Hurt L, Ilyas M, Jehan F, Kalonji M, Kaur J, Khanam R, Kirkwood B, Kumar A, Kumar A, Kumar V, Manu A, Marete I, Masanja H, Mazumder S, Mehmood U, Mishra S, Mitra DK, Mlay E, Mohan SB, Moin MI, Muhammad K, Muhihi A, Newton S, Ngaima S, Nguwo A, Nisar I, O’Leary M, Otomba J, Patil P, Quaiyum MA, Rahman MH, Sazawal S, Semrau KEA, Shannon C, Smith ER, Soofi S, Soremekun S, Sunday V, Taneja S, Tshefu A, Wasan Y, Yeboah-Antwi K, Yoshida S, Zaidi A. Population-based rates, timing, and causes of maternal deaths, stillbirths, and neonatal deaths in south Asia and sub-Saharan Africa: a multi-country prospective cohort study [Internet]. The Lancet Global Health. 2018 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 8];6(12):e1297–308. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(18)30385-1/fulltext doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30385-1

- Noël L, Coutinho CM, Thilaganathan B. Preventing stillbirth: a review of screening and prevention strategies [Internet]. Maternal-Fetal Medicine. 2022 July [cited 2026 Jan 8];4(3):218–28. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/mfm/fulltext/2022/07000/preventing_stillbirth__a_review_of_screening_and.9.aspx doi:10.1097/FM9.0000000000000160

- Shanker O, Saini V, Gupta M. Stillbirths: incidence, causes and surrogate markers of intrapartum and antepartum fetal deaths [Internet]. ijirms. 2020 Aug 1 [cited 2026 Jan 8];5(08):289–95. Available from: https://www.ijirms.in/index.php/ijirms/article/view/927 doi:10.23958/ijirms/vol05-i08/927

- Sharma B, Raina A, Kumar V, Mohanty P, Sharma M, Gupta A. Counting stillbirth in a community – To understand the burden [Internet]. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health. 2022 Mar [cited 2026 Jan 8];14:100977. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2213398422000173 doi:10.1016/j.cegh.2022.100977

- Halim A, Aminu M, Dewez JE, Biswas A, Rahman AKMF, Van Den Broek N. Stillbirth surveillance and review in rural districts in Bangladesh [Internet]. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 8];18(1):224. Available from: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-018-1866-2 doi:10.1186/s12884-018-1866-2

- WHO. Improving maternal and newborn health and survival and reducing stillbirth – Progress report 2023 [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2023 [cited 2026 Jan 8]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240073678