Research | Open Access | Volume 9 (1): Article 11 | Published: 19 Jan 2026

Predictors of COVID-19 mortality at 30 days of hospitalisation in Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Tables

| Characteristic | Overall, N = 400 | Self-medication | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, N = 374 | Yes, N = 26 | p-value | ||

| Length of hospital stay, median (IQR) | 9 (6, 13) | 10 (6, 13) | 6 (2, 10) | 0.011 |

| Status, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Alive | 312 (78) | 299 (80) | 13 (50) | |

| Deaths | 88 (22) | 75 (20) | 13 (50) | |

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 50 (34, 65) | 50 (34, 65) | 59 (43, 68) | 0.065 |

| Age (years), n (%) | 0.4 | |||

| <20 | 11 (2.8) | 11 (2.9) | 0 (0) | |

| 20–39 | 127 (32) | 122 (33) | 5 (19) | |

| 40–59 | 115 (29) | 107 (29) | 8 (31) | |

| ≥60 | 146 (37) | 133 (36) | 13 (50) | |

| Gender of patient, n (%) | 0.8 | |||

| Female | 162 (41) | 151 (40) | 11 (42) | |

| Male | 238 (59) | 223 (60) | 15 (58) | |

| Civil status, n (%) | 0.3 | |||

| Married or common-law | 161 (64) | 147 (64) | 14 (70) | |

| Single | 56 (22) | 54 (23) | 2 (10) | |

| Divorced or separated | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Widower | 33 (13) | 29 (13) | 4 (20) | |

| Profession, n (%) | 0.5 | |||

| Healthcare professional | 39 (13) | 38 (14) | 1 (4.3) | |

| No profession | 121 (40) | 111 (40) | 10 (43) | |

| Others | 140 (47) | 128 (46) | 12 (52) | |

| History of hypertension, n (%) | 0.8 | |||

| No | 239 (70) | 221 (69) | 18 (72) | |

| Yes | 104 (30) | 97 (31) | 7 (28) | |

| History of diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 0.8 | |||

| No | 256 (75) | 238 (75) | 18 (72) | |

| Yes | 87 (25) | 80 (25) | 7 (28) | |

| History of HIV, n (%) | 0.089 | |||

| No | 329 (98) | 306 (98) | 23 (92) | |

| Yes | 7 (2.1) | 5 (1.6) | 2 (8.0) | |

| History of heart disease, n (%) | 0.6 | |||

| No | 322 (96) | 297 (96) | 25 (100) | |

| Yes | 13 (3.9) | 13 (4.2) | 0 (0) | |

1 Median (IQR); n (%) 2 Wilcoxon rank sum test; Pearson’s Chi-squared test; Fisher’s exact test | ||||

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics and medical history of hospitalised COVID-19 patients in Goma City from March 2020 to September 2021

| Characteristic | Overall, N = 400 | Self-medication | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, N = 374 | Yes, N = 26 | p-value | ||

| Respiratory rate, median (IQR) | 22 (20, 27) | 22 (20, 26) | 26 (20, 36) | 0.077 |

| Heart rate, median (IQR) | 92 (81, 105) | 92 (81, 105) | 98 (86, 110) | 0.2 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure, median (IQR) | 127 (113, 142) | 127 (114, 142) | 129 (112, 151) | 0.7 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure, median (IQR) | 80 (70, 90) | 80 (70, 90) | 80 (70, 87) | 0.6 |

| Duration between symptom onset and care, median (IQR) | 4 (3, 7) | 4 (3, 7) | 7 (3, 12) | 0.032 |

| Clinical stage at admission, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Mild | 132 (33) | 129 (34) | 3 (12) | |

| Moderate | 135 (34) | 130 (35) | 5 (19) | |

| Severe | 105 (26) | 90 (24) | 15 (58) | |

| Critical | 28 (7.0) | 25 (6.7) | 3 (12) | |

| Oxygen saturation, n (%) | 0.020 | |||

| SaO2 ≥95% | 161 (43) | 156 (45) | 5 (19) | |

| SaO2 <90% | 142 (38) | 126 (36) | 16 (62) | |

| SaO2 90–94% | 73 (19) | 68 (19) | 5 (19) | |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome, n (%) | 0.002 | |||

| No | 301 (75) | 288 (77) | 13 (50) | |

| Yes | 99 (25) | 86 (23) | 13 (50) | |

| Temperature, n (%) | 0.030 | |||

| Normal | 280 (71) | 267 (73) | 13 (50) | |

| Hypothermia | 6 (1.5) | 6 (1.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Fever | 106 (27) | 93 (25) | 13 (50) | |

| Obesity status, n (%) | 0.8 | |||

| No | 332 (89) | 308 (89) | 24 (92) | |

| Yes | 42 (11) | 40 (11) | 2 (7.7) | |

| Complications, n (%) | 0.002 | |||

| Not documented / None | 243 (61) | 236 (63) | 7 (27) | |

| Respiratory failure | 112 (28) | 100 (27) | 12 (46) | |

| Heart failure | 7 (1.8) | 5 (1.3) | 2 (7.7) | |

| Thromboembolic diseases | 3 (0.8) | 3 (0.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Stroke | 5 (1.3) | 5 (1.3) | 0 (0) | |

| SIRS | 26 (6.5) | 21 (5.6) | 5 (19) | |

| Drug reaction | 3 (0.8) | 3 (0.8) | 0 (0) | |

1 Median (IQR); n (%) 2 Wilcoxon rank sum test; Fisher’s exact test; Pearson’s Chi-squared test | ||||

Table 2: Clinical characteristics of hospitalised COVID-19 patients in Goma City from March 2020 to September 2021

| Characteristic | Overall, N = 400 | Self-medication | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, N = 374 | Yes, N = 26 | p-value | ||

| Malaria, n (%) | >0.9 | |||

| Negative | 129 (88) | 116 (87) | 13 (93) | |

| Positive | 18 (12) | 17 (13) | 1 (7.1) | |

| D-dimer concentration (µg/l), n (%) | 0.7 | |||

| <500 | 59 (72) | 50 (70) | 9 (82) | |

| ≥500 | 23 (28) | 21 (30) | 2 (18) | |

| C-reactive protein concentration (mg/l), n (%) | 0.047 | |||

| <6 | 25 (15) | 25 (17) | 0 (0) | |

| ≥6 | 138 (85) | 119 (83) | 19 (100) | |

| White blood cell count, n (%) | 0.076 | |||

| 4000–10000 | 129 (63) | 118 (64) | 11 (52) | |

| <4000 | 17 (8.3) | 17 (9.3) | 0 (0) | |

| >10000 | 58 (28) | 48 (26) | 10 (48) | |

| Granulocyte count, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 550–7500 | 136 (67) | 129 (71) | 7 (33) | |

| <550 | 3 (1.5) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (9.5) | |

| >7500 | 64 (32) | 52 (29) | 12 (57) | |

| Blood glucose concentration (mmol/l), n (%) | >0.9 | |||

| 4–6 | 42 (32) | 38 (33) | 4 (29) | |

| <4 | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0) | |

| ≥7 | 87 (67) | 77 (66) | 10 (71) | |

| Creatinine concentration (µmol/l), n (%) | 0.2 | |||

| M ≤120 / F ≤100 | 71 (65) | 61 (62) | 10 (83) | |

| M >120 / F >100 | 39 (35) | 37 (38) | 2 (17) | |

| Chest radiograph, n (%) | >0.9 | |||

| Normal | 4 (7.3) | 4 (8.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Bilateral lesions | 47 (85) | 41 (84) | 6 (100) | |

| Unilateral lesions | 4 (7.3) | 4 (8.2) | 0 (0) | |

1 n (%) 2 Fisher’s exact test | ||||

Table 3: Biochemical characteristics of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Goma City from March 2020 to September 2021

Figures

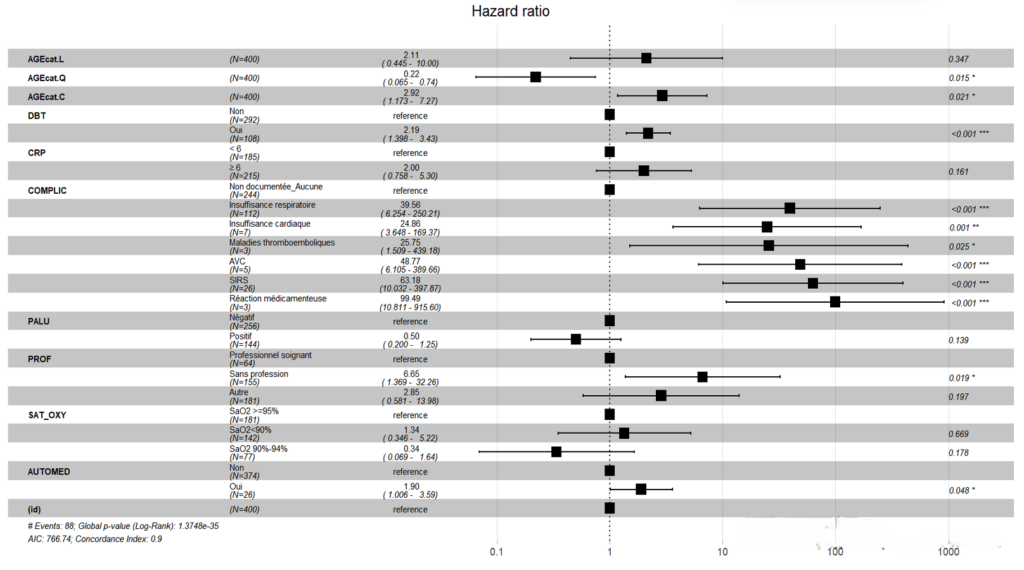

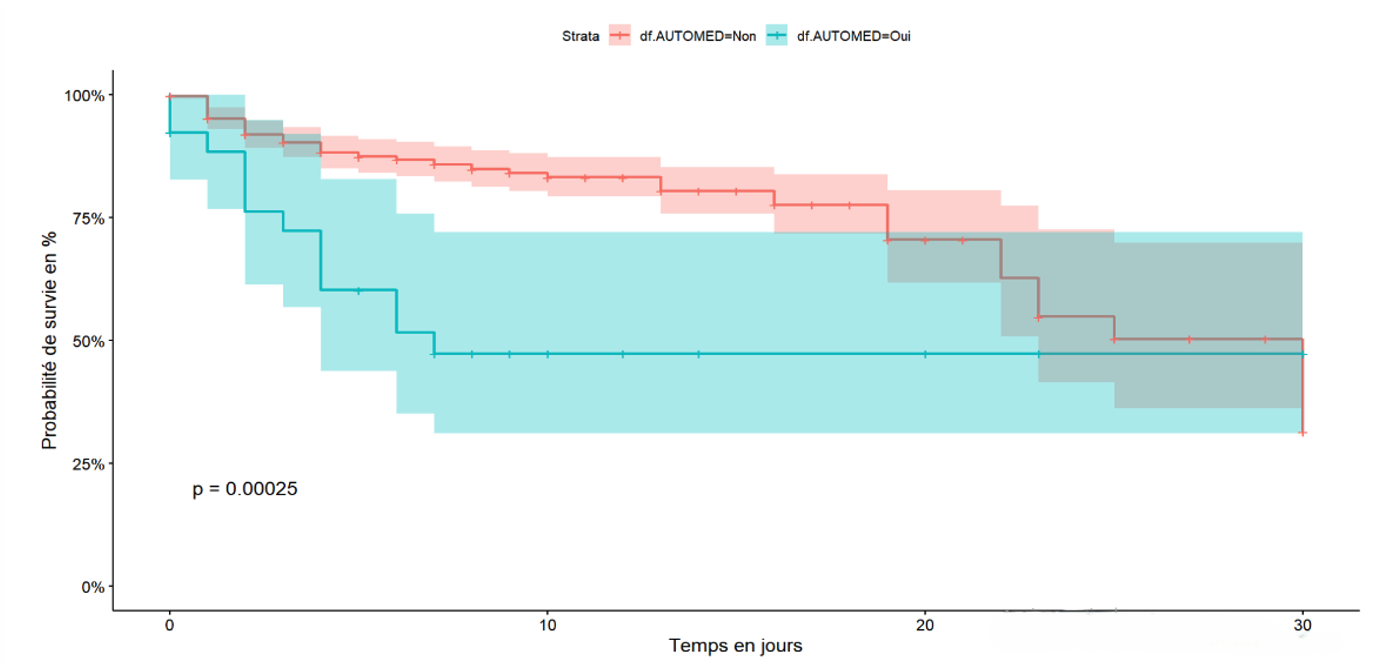

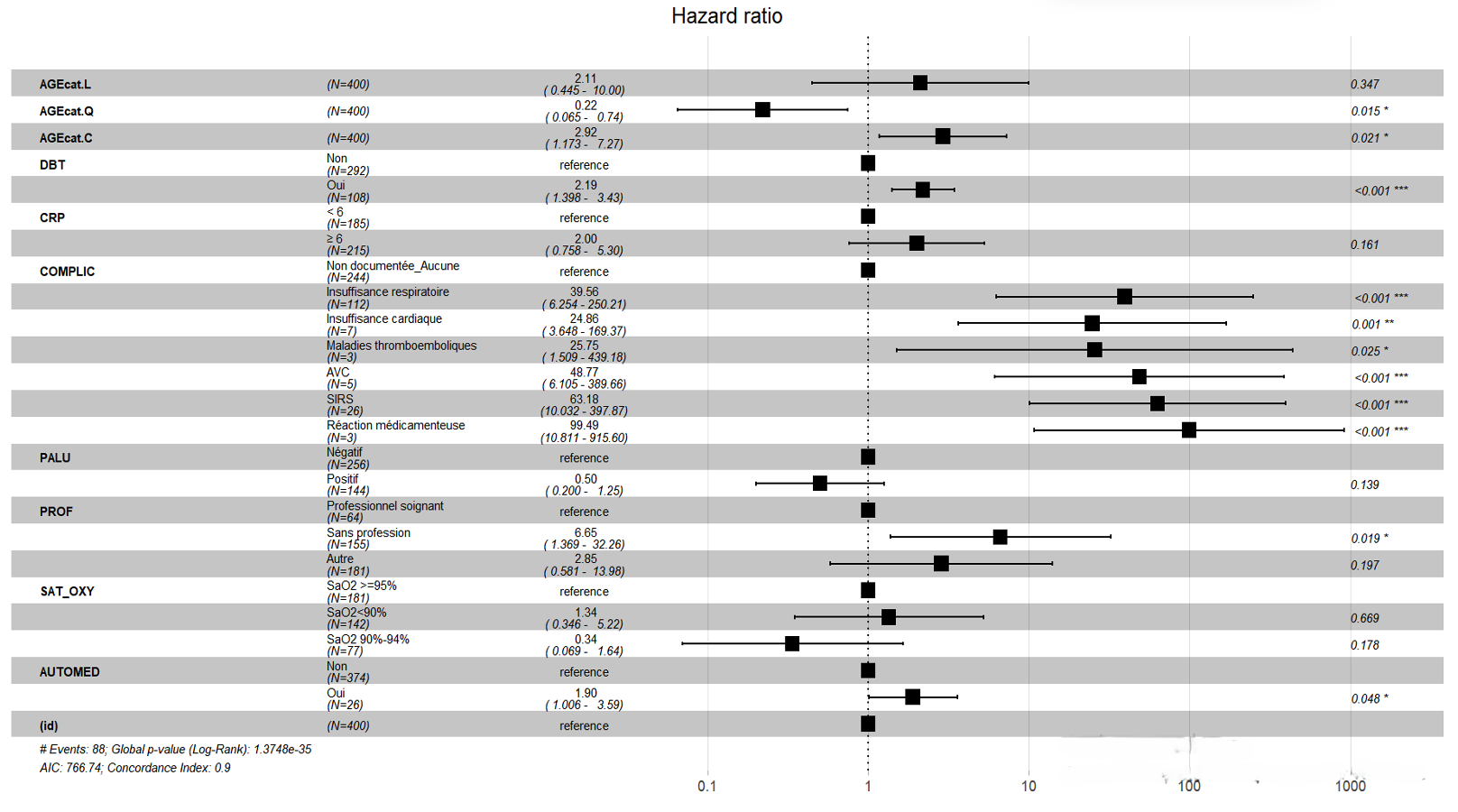

Abbreviations:

AGEcat.L: 0–39 years;

AGEcat.Q: 40–59 years;

AGEcat.C: ≥60 years;

DBT: Diabetes mellitus;

CRP: C-reactive protein;

SAT_OXY: Oxygen saturation;

COMPLIC: Complications;

PROF: Profession;

PALU: Malaria co-infection;

AUTOMED: Self-medication.

Keywords

- Predictors

- Death

- COVID-19

- Goma

Cosma Kajabika Luberamihero1,&, Odrade Chabikuli2, Claire Sangara Rukiya3, Ken Kayembe Mabika4, Nzanzu Magazani Alain4, Lubula Léopold5, Wolfgang Weber6, Prince Kimpanga Diangs2

1Field Epidemiology Training and Laboratory Programme, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2Department of Statistics and Epidemiology, Kinshasa School of Public Health, University of Kinshasa, 3Epidemiologist at the World Health Organisation’s Bukavu sub-office, 4AFENET Coordination Office, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo, 5Epidemiological Surveillance Department, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo, 6Research Coordinator at Médecins sans Frontières Netherlands, Democratic Republic of Congo Goma Mission.

&Corresponding author: Cosma Kajabika Luberamihero, Field Epidemiology Training and Laboratory Programme, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo, Email: cosmakajabika7@gmail.com, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-4336-2764

Received: 25 Feb 2025, Accepted: 18 Jan 2026, Published: 19 Jan 2026

Domain: COVID-19 Pandemic

Keywords: Predictors, Death, COVID-19, Goma

©Cosma Kajabika Luberamihero et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Cosma Kajabika Luberamihero et al., Predictors of COVID-19 mortality at 30 days of hospitalisation in Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025; 9(1):11. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00058

Abstract

Introduction: The COVID-19 pandemic has affected all provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, particularly the city of Goma (North Kivu). The effective crude fatality ratio in the DRC was 1.93%, while in Goma it was 7.4%. This study determined the apparent crude fatality ratio in the COVID-19 treatment centre and identified the predictors of COVID-19-related deaths within 30 days of hospitalisation in the city of Goma.

Methods: A historical cohort study was conducted on patients hospitalised for COVID-19 in Goma’s COVID-19 Treatment Centres with self-medication as the exposure factor. The minimum calculated sample size was 356 individuals. SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed by RT-PCR, and the WHO definition was used for confirmed deaths. Cox regression identified independent predictors of COVID-19 death in Goma. We included 400 medical records of hospitalised COVID-19 patients.

Results: The apparent crude fatality ratio was significantly higher in hospitalised patients exposed to self-medication at 50% (95% CI:32.06%-67.94%) compared to 20% (95% CI:16.19%-24.55%, p=value <0.001) among non-exposed. Cox regression identified the following death predictors: diabetes mellitus (aHR=2.92, 95% CI:1.40-3.43, p < 0.001); self-medication (aHR=1.90, 95%CI:1.01-3.59, p=0.048); being unemployed (aHR = 6.65, 95% CI:1.37-32.26, p=0.019); age ≥ 60 years (aHR=2.92, 95% CI: 1.17-7.27, p=0.021); complications including respiratory failure (aHR=39.56, 95% CI: 6.25-250.21, p < 0.001); heart failure (aHR=24.86, 95% CI: 3.65-169.37, p=0.001); thromboembolic diseases (aHR=25.75, 95% CI: 1.51- 439.18, p=0.025); stroke (aHR = 48.77, 95% CI: 6.11-389.66, p < 0.001); systemic inflammatory response syndrome (aHR=63.18, 95% CI: 10.03-397.87, p < 0.001); and drug reaction (aHR=99.49, 95% CI:10.81-915.60, p < 0.001).

Conclusions: Advanced age beyond 60 years, self-medication, a history of diabetes mellitus, unemployment, and the occurrence of complications are predictors of death related to COVID-19 within 30 days of hospitalisation. Development of policies to protect vulnerable people (aged ≥60 years, those with chronic diseases and the poor) and a communication program to change behaviour towards self-medication could reduce COVID-19 fatality in Goma.

Introduction

Since the emergence of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2), also known as “Coronavirus Disease 2019” (COVID-19), the world has faced an unprecedented health crisis. The rapid increase in hospitalisations for severe COVID-19 forms has strained the healthcare system. As of January 22, 2020, the WHO had received dozens of alerts from 20 countries regarding possible infections by the new coronavirus. In Africa, 16 countries, including the DRC, reported persons under investigation (PUI) for COVID-19 [1,2].

The DRC reported its first confirmed COVID-19 case on March 10, 2020, involving a Congolese individual living in France who returned to the country on March 8, 2020, making it the 11th African country affected by COVID-19 [2]. North Kivu province reported its first confirmed COVID-19 case on April 1, 2020, in Goma, and on April 2 in Beni, both cases being foreign truck drivers. As of August 31, 2021, the cumulative global COVID-19 cases were 216,867,420 with 4,507,837 deaths, a crude case fatality rate of 2.08%. In Africa, there were 5,580,789 confirmed cases and 135,182 deaths, a case fatality rate of 2.42%. The DRC reported 54,863 confirmed cases with 1,059 deaths, a fatality rate of 1.93%. In North Kivu, 6,794 people tested positive for COVID-19 with 500 deaths, a fatality rate of 7.4%, with about 80% of deaths in North Kivu occurring in the Goma, Karisimbi, and Nyiragongo health zones [2,3].

Interventions to reduce COVID-19 mortality in North Kivu included establishing a diagnostic centre for early diagnosis and management, though this strategy did not reduce the mortality rate to the national average. Complementary measures included lockdown, awareness campaigns, supply and logistical support, training, and free healthcare provided by the central government. Additionally, the vaccination campaign started in the DRC, and particularly in North Kivu, on April 19, 2021, did not seem effective due to community reluctance. By August 17, 2021, North Kivu had vaccinated only 6,500 people [2]. This suggests a continued transmission of the disease and, consequently, a persistence of high lethality. Based on the aforementioned, the COVID-19 crude fatality rate in the North Kivu Province is higher than the national average, making it the second most affected province after the city-province of Kinshasa.

The COVID-19 epidemic created widespread psychosis and anxiety among the population in sub-Saharan Africa [4]. This could be linked, on the one hand, to the high mortality observed in some countries, such as Italy and Spain, and on the other hand, to the lack of technical resources to combat the disease in sub-Saharan Africa [5]. Regarding the African continent, the WHO indicated that it fears the worst, as even the better-resourced health-care systems of developed countries have faced enormous difficulties in dealing with the epidemic [6]. Faced with this situation and the widespread misinformation on social media, many plants and substances without the minimum requirements of efficacy and tolerance have been proposed to treat or prevent COVID-19 [7]. The use of these substances without medical advice is considered self-medication, which is defined as taking medicines, herbs or home remedies on one’s own initiative or on the advice of another person without consulting a medical doctor [8]. In Kinshasa city, DRC, the population, distraught and on its own initiative, has heavily resorted to certain traditional pharmacopoeia recipes : this is self-medication. These recipes, which are reputed to cure certain symptoms of COVID-19, have not brought only happiness, several cases have resulted in death and other inconveniences [9].

There is an abundant literature on predictors of COVID-19 mortality, but self-medication as a predictor of COVID-19 mortality has not yet been thoroughly investigated to the best of our knowledge. Several studies have highlighted the prevalence of self-medication and associated factors in patients suffering from COVID-19 worldwide and in Africa [5,10,11,12,13].

There is a need to identify the predictors of death linked to COVID-19 in the 30 days of hospitalisation for COVID-19 in the city of Goma. We hypothesised that self-medication was the principal reason for the high mortality rate in the city of Goma. The objective of this study was to determine the apparent crude fatality ratio in the COVID-19 treatment centre in Goma and identify the predictors of COVID-19-related deaths within 30 days of hospitalisation in the city of Goma.

Methods

Study design

A retrospective cohort study was conducted from March 1, 2020, to September 31, 2021. The study population included all patients hospitalised and confirmed positive by Reverse Transcriptase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) in the CTCo of Goma. This study was conducted in four COVID-19 Treatment Centres (CTCo) in the Goma and Karisimbi health zones in Goma city: North Kivu Provincial Reference Hospital, Charité Maternelle General Reference Hospital, Virunga General Reference Hospital, and Kyeshero Hospital Centre. The statistical unit consisted of patients hospitalised for COVID-19 and who tested positive for RT-PCR in the CTCo of Goma. We excluded patients whose medical records were not found. A total of 400 medical records were retrieved. Self-medication was considered the exposure factor. Patients were divided into two groups: 26 self-medicated and 374 non-self-medicated patients. Data were collected by the authors, all of whom are physicians.

Data collection

Data were collected using a data collection form from patients’ records after identifying COVID-19 positive patients in the hospitalisation register. Data were daily encoded into Epidata software after verification and validation, and analysed using R 4.3.3 software. Missing values for the Cox model were handled by multiple imputation using the MICE (Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations) algorithm. Age, Systolic Blood Pressure, Diastolic Blood Pressure, Oxygen Saturation, Temperature, C-Reactive Protein concentration, White Blood Cell Count, Granulocyte Count, and Blood Glucose Concentration were categorised before statistical analysis. The dependent variable was the time to death occurrence within 30 days of hospitalization. Predictor variable included: Age, Sex, Profession, History of Hypertension, History of Diabetes Mellitus, History of HIV, History of Heart Disease, Respiratory Rate, Heart Rate, Systolic Blood Pressure, Diastolic Blood Pressure, Duration between symptom onset and treatment initiation, Clinical stage at admission, Oxygen Saturation, Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Temperature, Presented Complications, Malaria Coinfection, C-reactive Protein concentration (mg/l), White Blood Cell Count, Granulocyte Count, Blood Glucose Concentration (mmol/l). The time to death was calculated from admission to CTCo until death, discharge, or the end of the study.

Sample size computation

The minimum size of statistical units to be included in the study was calculated using the OpenEpi software for a cohort study. We considered the relative risk of 3 for COVID-19 mortality for the importance in public health. Significance threshold: 5%, expected proportion of cases in the unexposed group: 5%, expected proportion of cases in the exposed group: 14%, Power: 80%, i.e. β = 0.2, confidence interval:95%, RR : 3. Therefore, the total sample size computed was 356 patients.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the data. Numeric variables, after normality verification by the Shapiro test at α=0.05, were summarised by median with interquartile range (IQR) and compared using the non-parametric Wilcoxon test at α=0.05. Categorical (qualitative) data were presented as frequencies and percentages and compared using the Chi-square or Fisher’s test as appropriate. Kaplan-Meier curves assessed survival after exposure, and the Log Rank test compared different survival curves. Stepwise Cox regression evaluated predictors associated with the instantaneous risk of death, and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) chose the best-fitted model. Variables associated with the instantaneous risk of death in the bivariate analysis were selected for the multivariate model. Associations were established by calculating Hazard Ratios and their confidence intervals. Hypothesis testing was conducted at α=0.05. Model validity was verified by proportional hazards over time based on Schoenfeld residual analysis, with no predictor presenting a p-value ≤ 0.05. Multicollinearity was checked, and the Cox model variables, after excluding those with VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) ≥ 5, presented a group Variance Inflation Factor (GVIF) < 5. Variables retained in the Cox regression included: Age, History of chronic diseases (Diabetes Mellitus, Hypertension, Heart Disease), Sex, C-reactive Protein, Profession, Oxygen Saturation, COVID-19-Malaria Coinfection, Oxygen Saturation, and self-medication, complications.

Ethical considerations

This study took place after the Kinshasa School of Public Health gave authorization of the research, which was presented to the Provincial Division of Health / North Kivu and to the Central Office of the Health Zone of Goma and Karisimbi for their approval. The protocol was then approved by the ethics committee of the Kinshasa School of Public Health (ESP/CE/132/2024). With regard to informed consent, we did not have any contact with the patients, so no biological procedures were used in the collection or processing of the data. The use of the results of this study will be limited to the strict exploitation related to its objectives.

Results

The apparent crude fatality ratio was 22% (95% CI: 18.11%-26.45%) in the CTCo of Goma city in our series. Hospitalised COVID-19 patients who self-medicated had a significantly higher apparent crude fatality rate than those who did not self-medicate, at 50% (95% CI:32.06%-67.94%) versus 20% (95% CI:16.19%-24.55%), with a p-value < 0.001 (Table 1).

The median age of the studied population was 50 years (IQR: 34-65). There was no age difference between COVID-19 patients exposed to self-medication and those not exposed; however, the median age of survivors was 45 years (IQR: 31-61), significantly different from the median age of non-survivors, which was 65 years (IQR: 56-74) with a p-value < 0.001 (Table 1).

The median stay of all hospitalised COVID-19 patients was 9 days (IQR: 6-13). The median stay of hospitalised patients exposed to self-medication was 6 days (IQR: 2-10), while it was 10 days (IQR: 6-13) for those not exposed to self-medication, with a p-value of 0.011 (Table 1). Males constituted 59% of all hospitalised COVID-19 patients. Married individuals and/or those in free unions comprised 64% of the sample. In our series, 13% of hospitalised COVID-19 patients were health professionals, 40% were unemployed, and 47% belong to other professions. (Table 1). In our series, 30% hospitalized had Hypertension,25% had diabetes mellitus, and 2.1% were living with HIV (Table 1).

The duration between the onset of symptoms and treatment of hospitalised COVID-19 patients in Goma city was significantly longer in patients exposed to self-medication compared to those not exposed to self-medication, with respective durations of 4 days, IQR (3-7) and 7 days, IQR (3-12), p-value 0.032 (Table 2). The clinical stage at admission of COVID-19 patients was influenced by self-medication. Patients exposed to self-medication were admitted at severe and critical stages of the disease at 58% and 12%, respectively, while those not exposed to self-medication were admitted at these stages at 24% and 6.7%, respectively, p-value < 0.001 (Table 2). Among hospitalised COVID-19 patients, 62% ot those who self-medicated had oxygen saturation levels below 90% compare to 36% among those who did not self-medicate. This was statistically significant (Table 2).

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) was observed in 50% of hospitalised COVID-19 patients who were self-medicated, compared to 23% of those who were not self-medicated, p-value 0.002 (Table 2). Fever was observed in 50% of COVID-19 patients who were self-medicated, compared to 25% of those who were not, p-value 0.030 (Table 2).

Patients exposed to self-medication developed significantly more complications compared to those not exposed to self-medication. Acute respiratory failure occurred in 46% of self-medicated patients compared to 27% in non-self-medicated patients, systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) occurred in 19% of self-medicated patients compared to 5.6% in non-self-medicated patients, and acute heart failure occurred in 7.7% of self-medicated patients compared to 1.3% in non-self-medicated patients (Table 2). C-Reactive Protein ≥6 mg/l was present in 100% of COVID-19 patients exposed to self-medication, compared to 83% among non-self-medicated patients, p-value 0.047 (Table 3). In self-medicated COVID-19 patients, abnormal granulocyte levels were observed in 57% of cases as hypergranulocytosis and 9.5% as hypogranulocytosis, whereas these abnormalities were significantly less frequent in patients who did not self-medicate (Table 3).

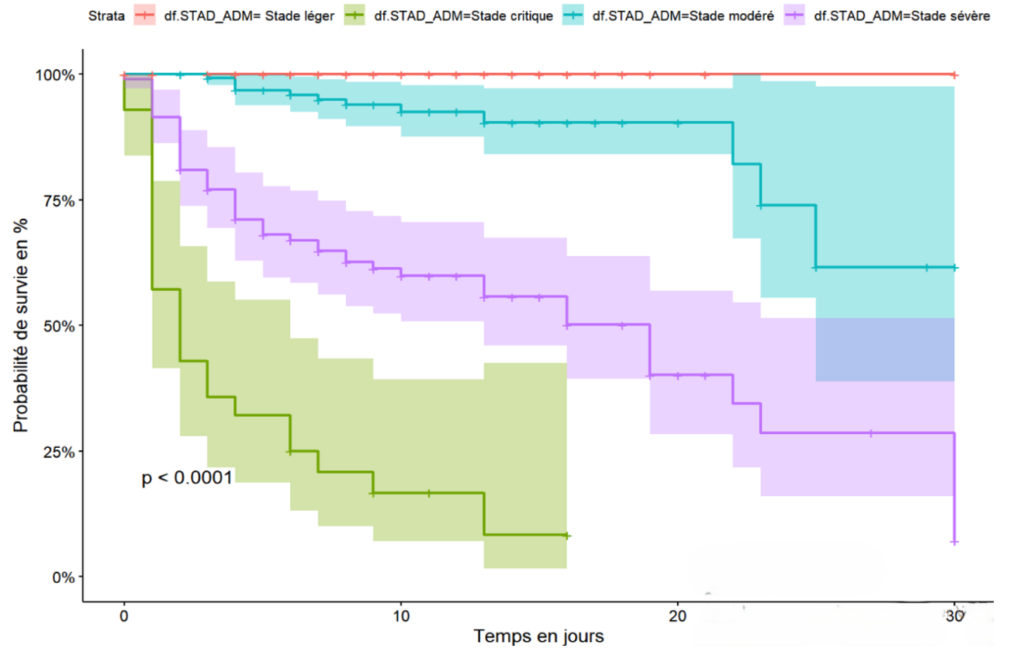

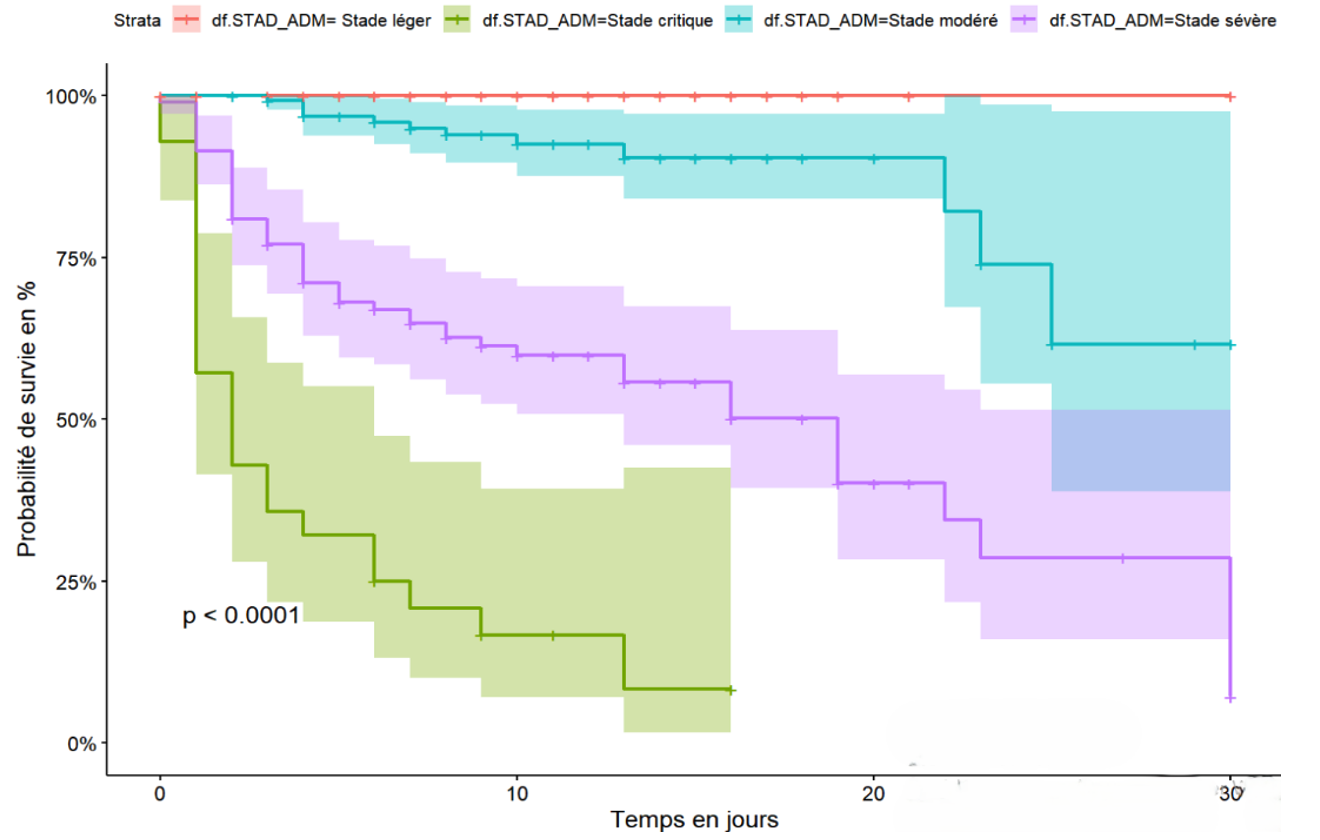

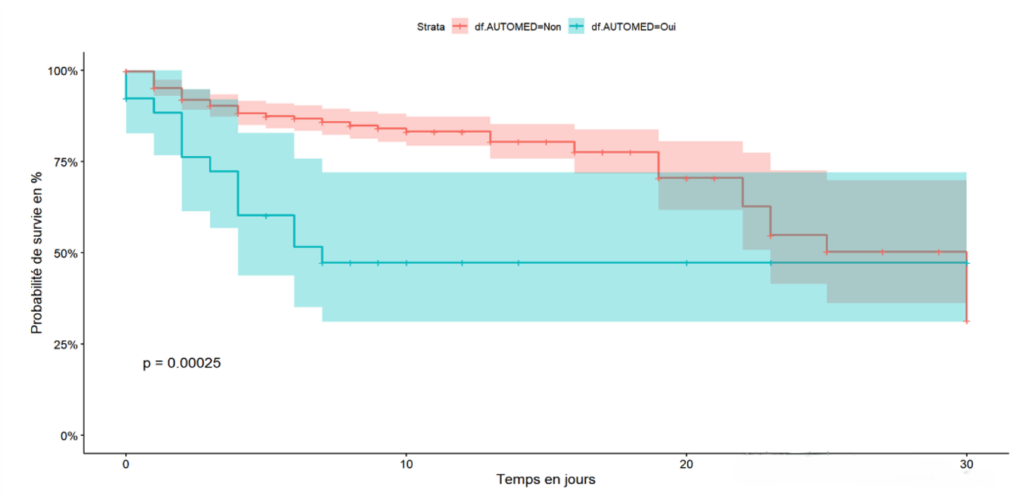

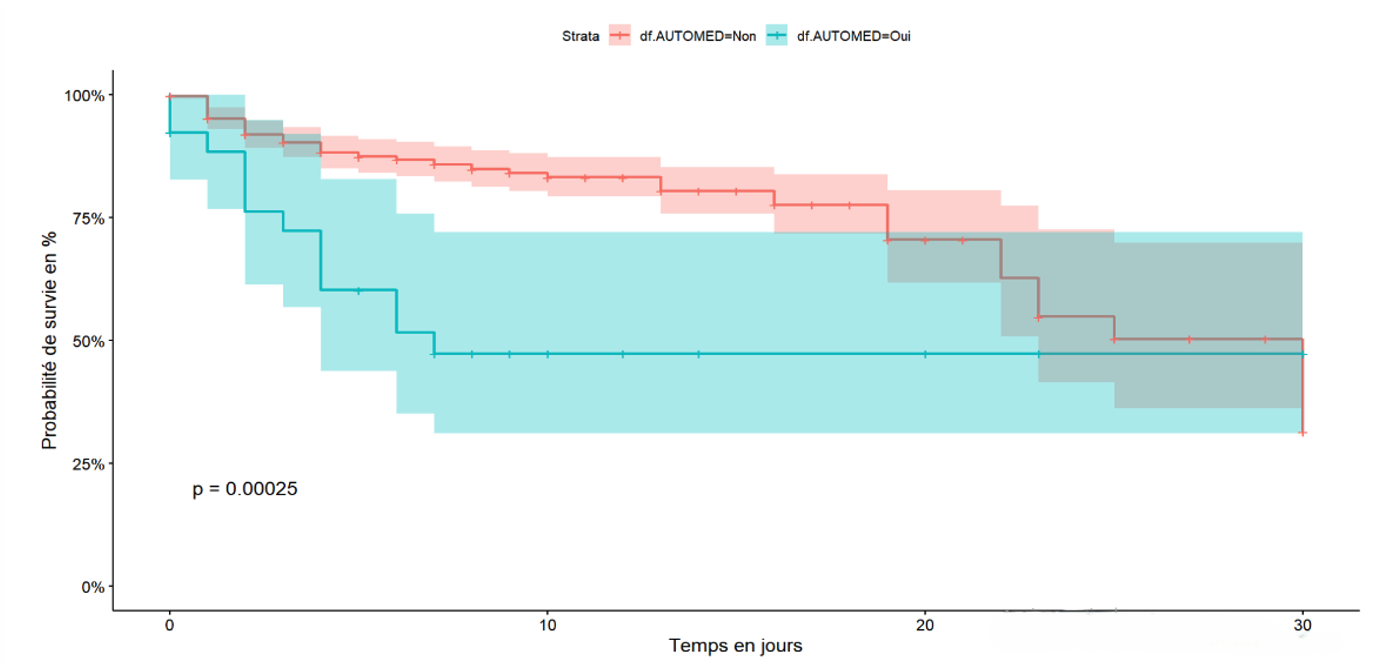

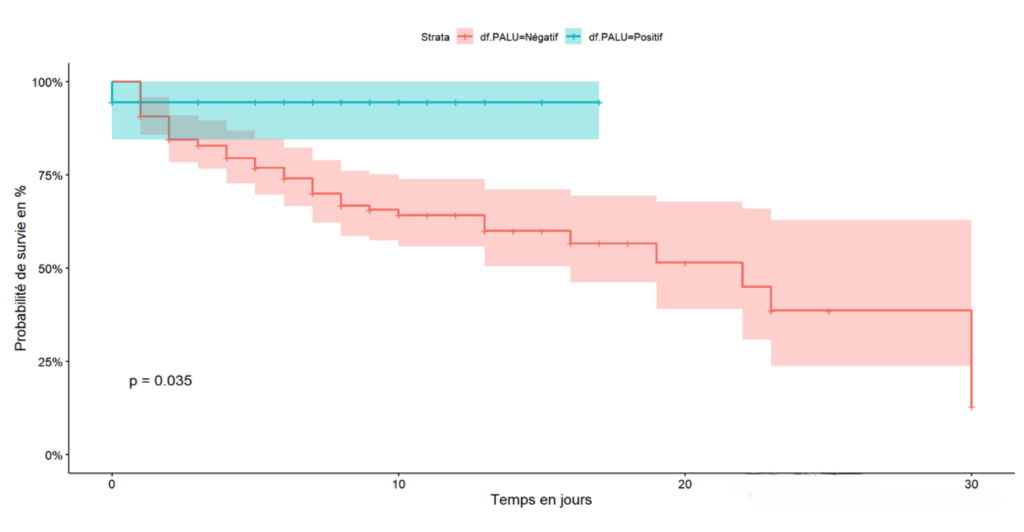

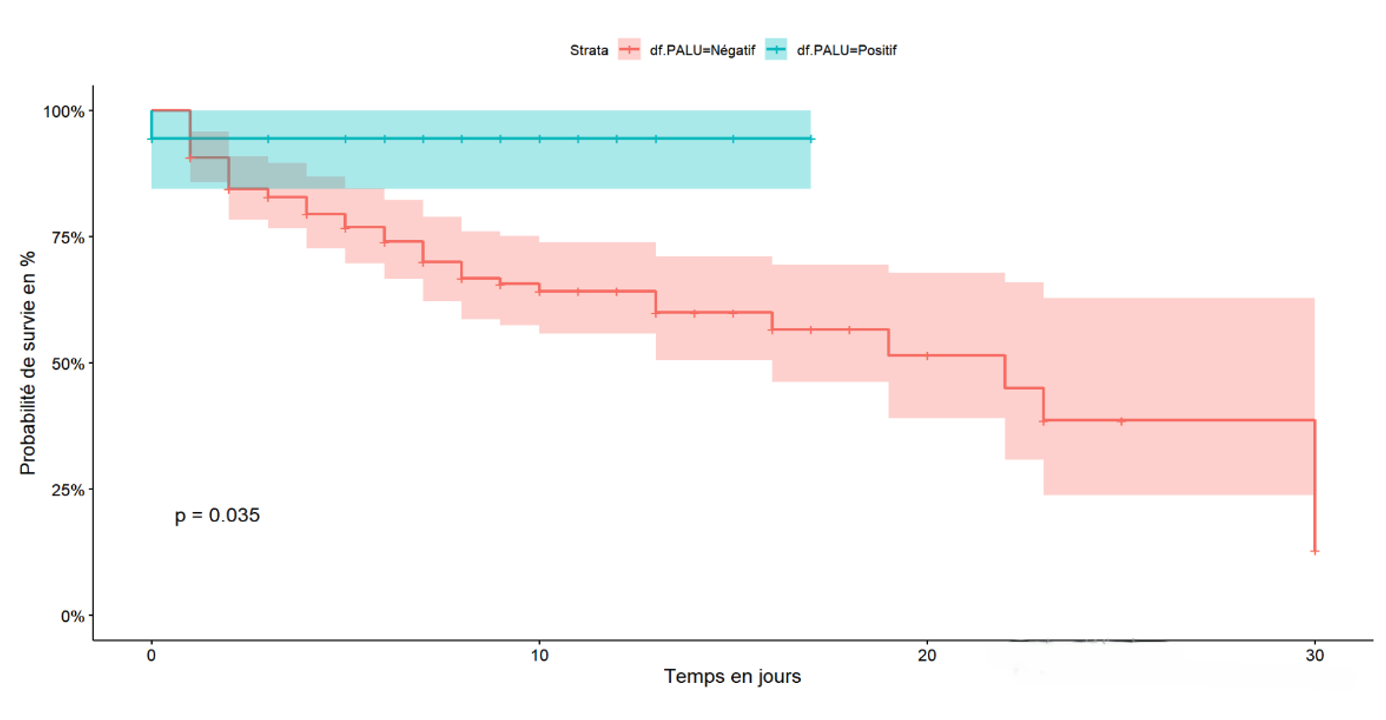

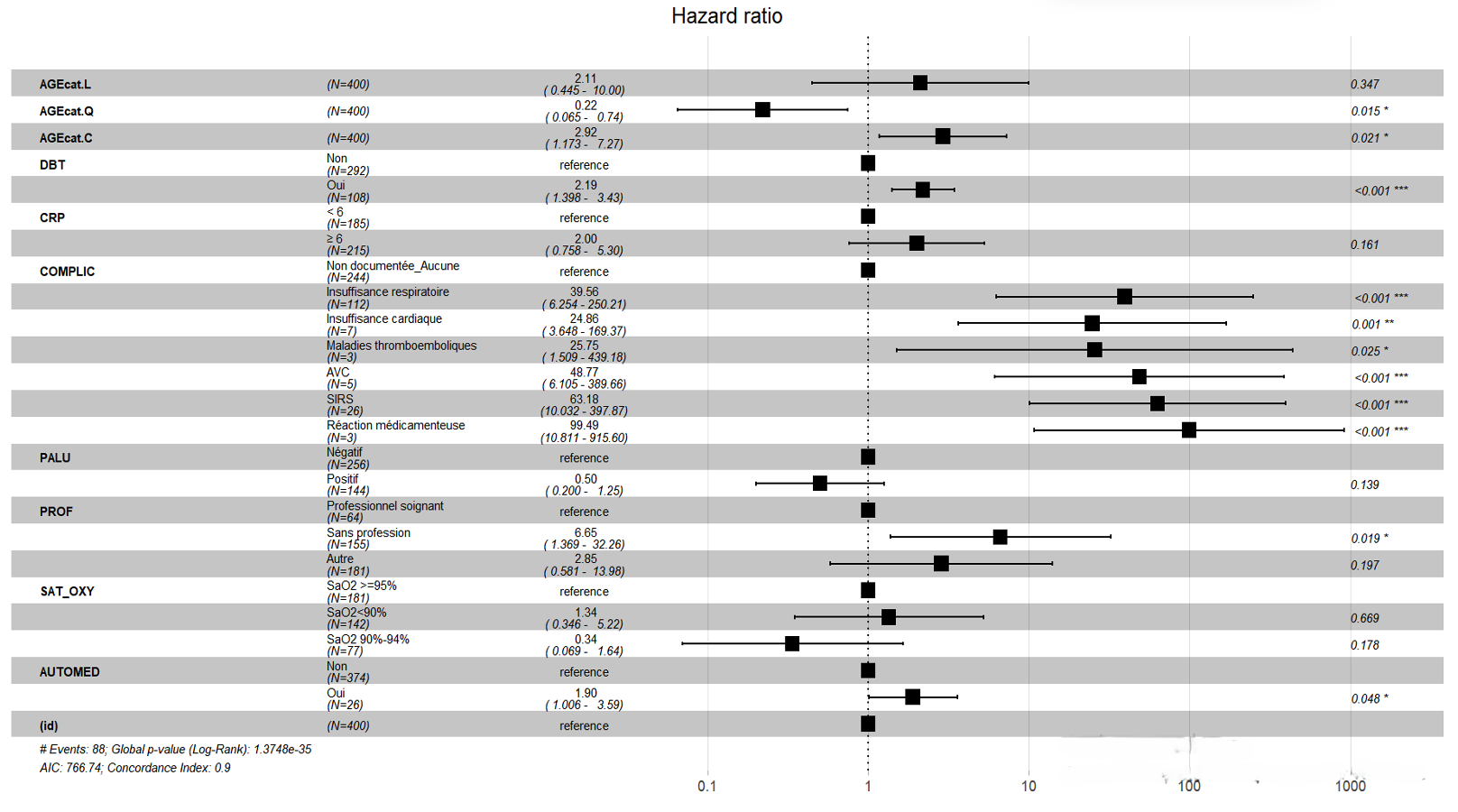

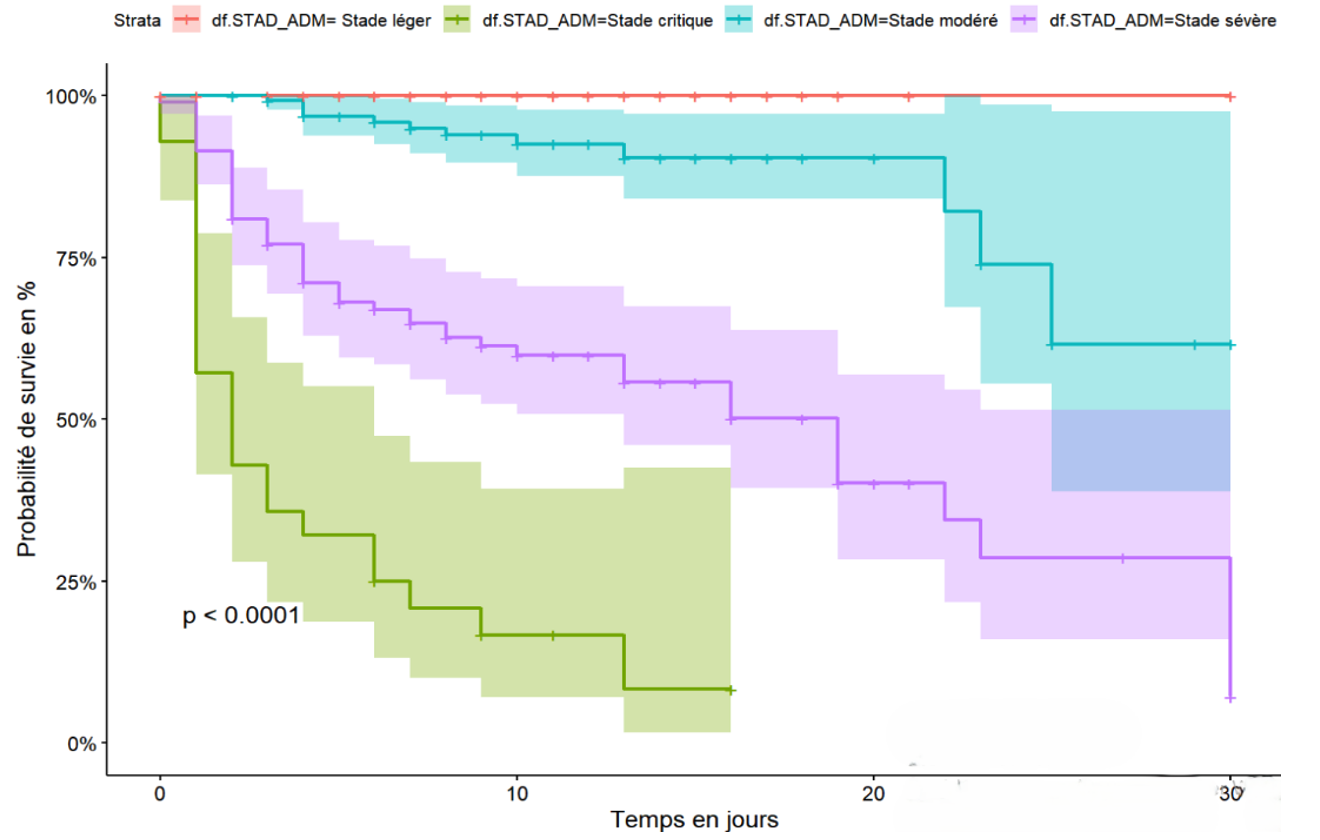

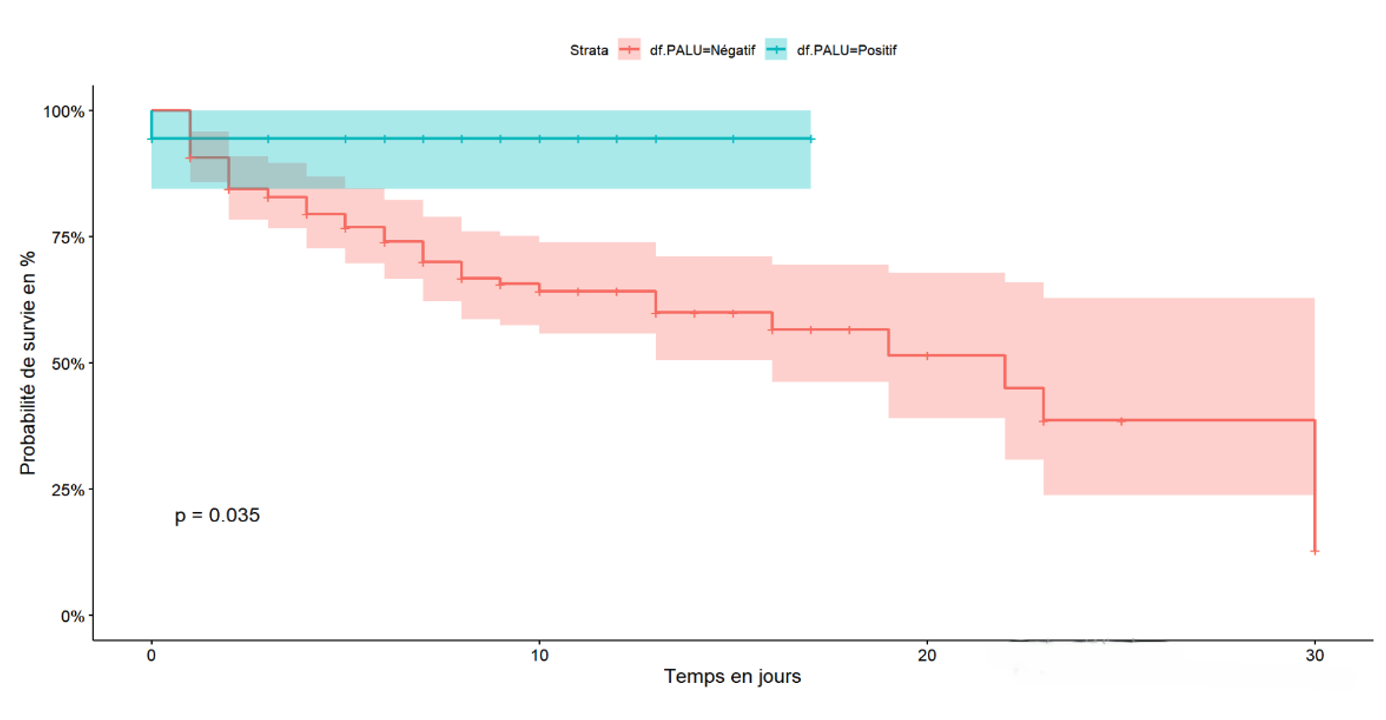

The cumulative 30-day survival probability is proportional to the stage of the disease at admission. Specifically, the mild stage had a 100% survival probability at 30 days of hospitalisation, whereas the critical stage had a 10% survival probability at 17 days of hospitalisation and 30% for the severe stage of the disease (Figure 1). Exposure to self-medication was associated with a decreased survival probability in the first week, with a 45% survival rate compared to 90% survival for patients not exposed to traditional products during the same period (Figure 2). Hospitalised COVID-19 patients who had a positive malaria test showed a cumulative survival probability of 90% at 16 days, while patients with a negative malaria test had a 58% survival probability during the same period (Figure 3)

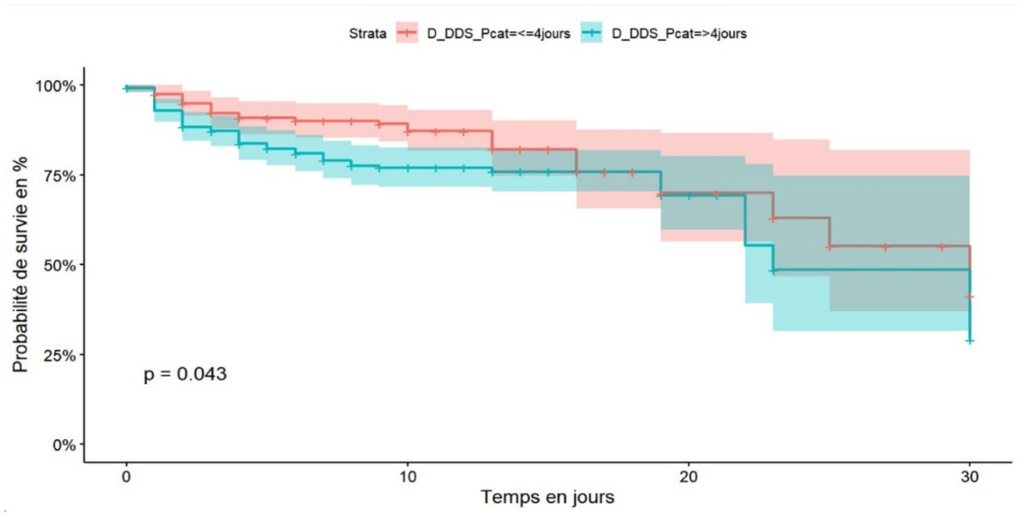

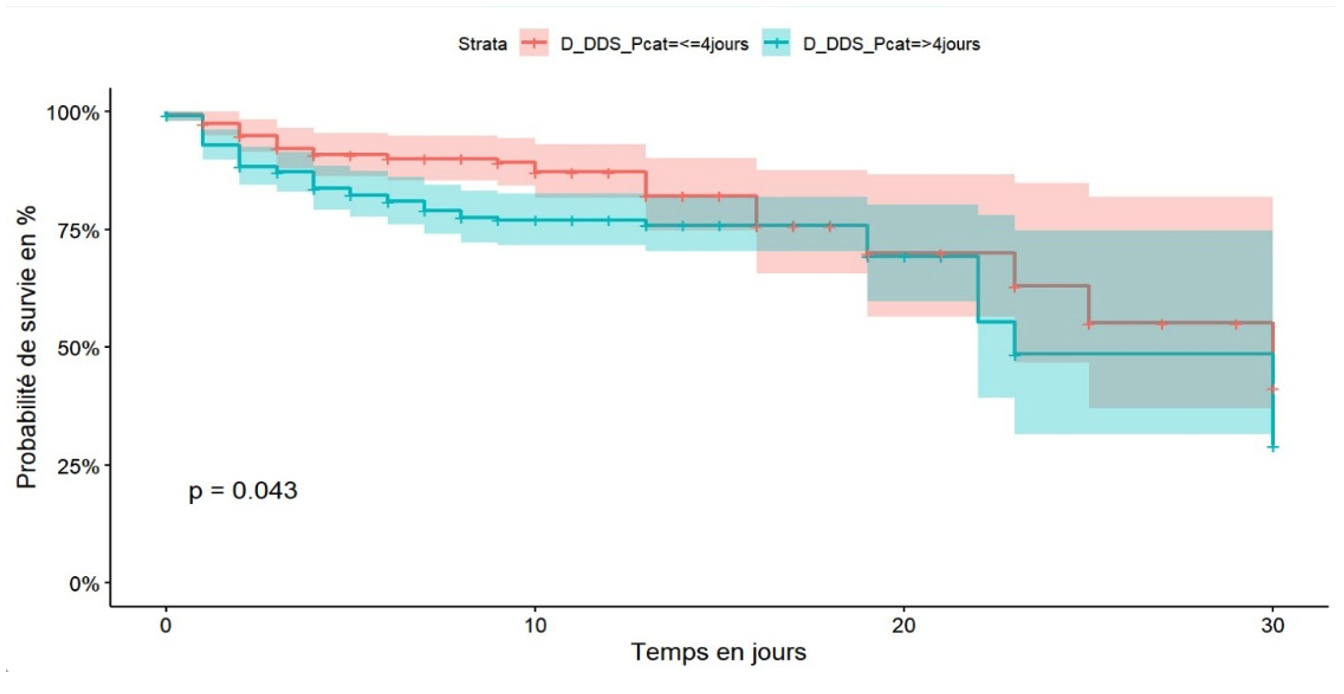

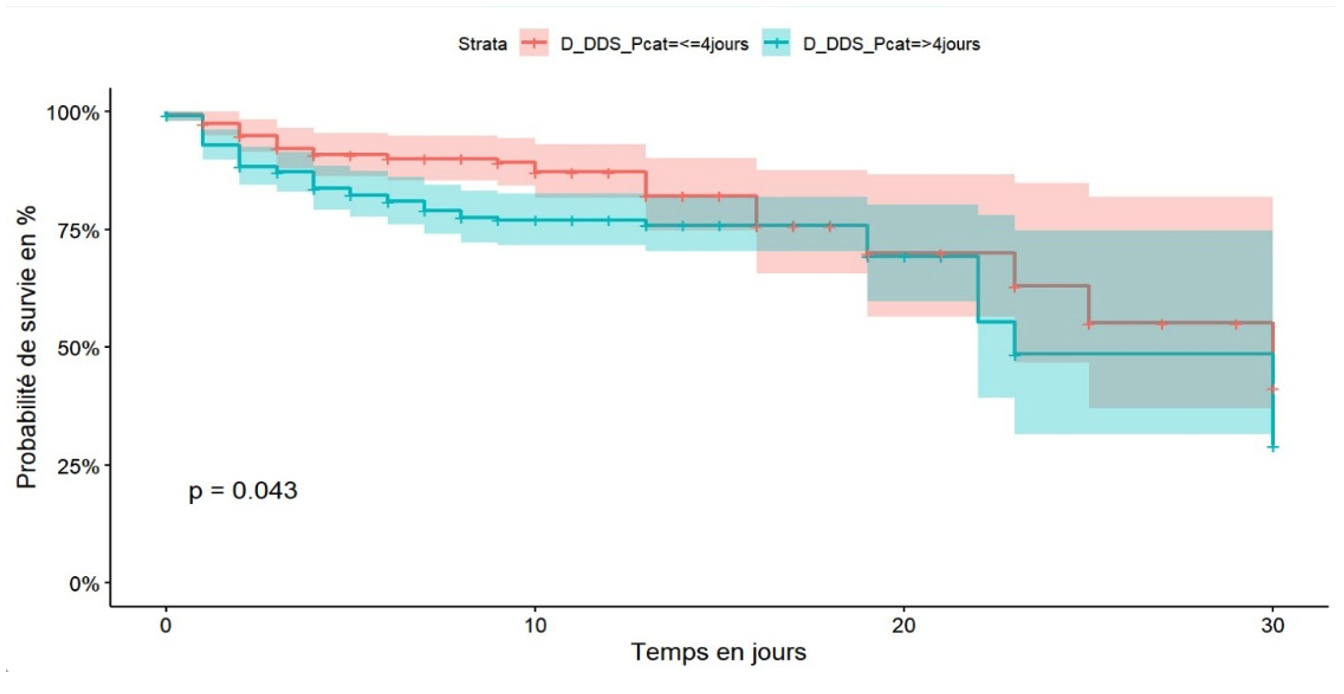

Patients who consulted healthcare facilities within four days of the onset of symptoms had better survival, 60% at 30 days of hospitalisation, than patients with COVID-19 who consulted more than four days after the onset of symptoms, 50% at 30 days of hospitalisation (Figure 4). After adjusting the Cox model, five independent predictors were identified. Diabetes mellitus was found to be an independent predictor of death among hospitalised COVID-19 patients in the city of Goma with an adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) of 2.92 (95% CI: 1.40-3.43), p-value < 0.001 (Figure 5).

Self-medication was an independent predictor of COVID-19-related death within 30 days of hospitalisation with an aHR of 1.90 (95% CI: 1.01-3.59), p-value 0.048 (Figure 5). Unemployment was an independent predictor of COVID-19-related death within 30 days of hospitalisation in the city of Goma. Unemployed patients had an aHR of 6.65 (95% CI: 1.37-32.26), p-value 0.019 (Figure 5). Age ≥ 60 years was a predictor of death with an aHR of 2.92 (95% CI: 1.17-7.27), p-value 0.021, while the age group of 30-59 years had an aHR of 0.22 (95% CI: 0.07-0.74), p-value 0.015 compared to the age group < 20 years (Figure 5).

The occurrence of complications was an independent predictor of COVID-19-related death within 30 days of hospitalisation in the city of Goma. Specifically, respiratory failure had an aHR of 39.56 (95% CI: 6.25-250.21), p-value < 0.001, heart failure had an aHR of 24.86 (95% CI: 3.65-169.37), p-value 0.001, thromboembolic diseases had an aHR of 25.75 (95% CI: 1.51-439.18), p-value 0.025, stroke had an aHR of 48.77 (95% CI: 6.11-389.66), p-value < 0.001, systemic inflammatory response syndrome had an aHR of 63.18 (95% CI: 10.03-397.87), p-value < 0.001, and drug reaction had an aHR of 99.49 (95% CI: 10.81-915.60), p-value < 0.001 (Figure 5).

Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to determine the predictors of death within 30 days of hospitalization for COVID-19 patients in the city of Goma, in order to contribute to reducing mortality rates. On this basis, we highlighted the main predictors of mortality among COVID-19 hospitalised patients in the city of Goma, namely: self-medication, lack of professional occupation, a history of diabetes mellitus and the occurrence of complications during the course of the illness.

The apparent case-fatality ratio of COVID-19 among patients hospitalized for COVID-19 is similar to the WHO estimate of the apparent case-fatality ratio, which ranges from less 0.1% to up 25%. [14] This apparent crude fatality ratio could be overestimated, on the one hand, because many less severe patients were treated either at home or in private clinics and, on the other hand, because of the greater probability of finding records of patients who died than of patients who recovered in the hospitals surveyed linked to a lack of archiving.

Our study showed that advanced age was a predictor of death within 30 days of hospitalization for COVID-19 patients. Studies conducted in the DRC in Kinshasa describe similar results [15,16]. Globally, a study conducted in England showed that advanced age, starting from 60 years, was the main risk factor for hospital mortality in patients suffering from COVID-19 [17]. Results from the ISARIC WHO CCP-UK cohort in England highlighted that age is a major contributor to high mortality scores above 9. Specifically, ages over 60 contribute 4 points, over 70 contribute 6 points, and over 80 contribute 7 points to the mortality score [17]. As with every system in the body, natural aging is accompanied by progressive biological changes in the immune system, some of which lead to its declining functions as evidenced by increased susceptibility to respiratory infections such as influenza and novel coronaviruses. On the other hand, age-related immune-mediated inflammation or inflamm-aging, and associated inflammatory diseases increase with aging. These changes in concert with comorbidities render older individuals vulnerable to latent or novel infections and lead to the observed increases in morbidity and mortality of COVID-19 [18]. COVID-19 is caused by SARS-CoV-2 (SC2) and is more prevalent and severe in elderly and patients with comorbid diseases (CM). Because chitinase 3-like-1 (CHI3L1) is induced during aging and CM, the relationships between CHI3L1 and SC2 were investigated. This study demonstrated that CHI3L1 is a potent stimulator of the SC2 receptor angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) [19]. In addition, in the context of Goma, socio-economic-environmental factors should be the subject of future research to elucidate their impact on the lives of the elderly.

The category of unemployed individuals was a predictor of mortality. This category is associated with a low economic income and aligns with the findings in England, which highlighted low economic status as a risk factor for COVID-19 mortality [17]. The risk of COVID-19-related mortalitywas substantially higher among younger unemployed participants than among younger employed participants in the corresponding age groups, unemployed female were more likely to die from COViD-19 infection than employed female, and the magnitude of this difference was greater than that between unemployed and employed male [20]. Due to socioeconomic and cultural factors, females are more likely to have part-time jobs and lower wages than males, as a consequence, jobloss may pose more economic distress for female, which would make it harder for them to afford the cost of COVID-19 treatment [20].

Diabetes mellitus is an independent predictor of mortality in our series. These results are corroborated by a meta-analysis including 33 studies (16,003 patients), which found that diabetes was significantly associated with COVID-19 mortality [16]. A WHO report reveals that in the Democratic Republic of Congo, patients with comorbidities of hypertension and/or diabetes mellitus accounted for 85% of all COVID-19 deaths[14]. A cohort study in Atlanta, US, and the OpenSAFELY database in the UK have all confirmed diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for COVID-19 mortality [17,21]. Several molecular pathomechanisms may render patients with diabetes vulnerable to COVID-19, as explained as follows.

Firstly, diabetes was associated with decreased phagocytic activity, neutrophil chemotaxis, diminished T cell function, and lower innate and adaptive immunity in general [22,23]. Furthermore, patients with diabetes had higher angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) levels than the general population. ACE2 serves as an entry receptor for SARS-CoV-2 due to its high binding affinity, which is expressed ubiquitously in human lung alveolar cells, cardiomyocytes, vascular endothelium, and other various sites. Consequently, SARS-CoV-2 has a high affinity for cellular binding and viral entry with decreased viral clearance [24].

Thirdly, elevated glucose levels directly increase SARS-CoV-2 replication with possible lethal complications due to dysregulation of the immune system and inflammatory response [25,26]. Lastly, there might be direct implications between glucose impairment and cytotoxic lymphocytes natural killer (NK) cell activity [27]. In DRC, 1.4 million people have been diagnosed with diabetes by a health professional, with an unknown, but certainly much larger number of Congolese living with diabetes without knowing it, without diagnosis, and therefore without treatment, diabetes could be a mortal danger for millions of people [28]. The high proportion of people living with undiagnosed or poorly monitored chronic hyperglycaemia, could be one of the reasons for the high COVID-19 mortality rate in the city of Goma. Future studies could investigate the prevalence and management of diabetes mellitus in a persistent humanitarian crisis setting.

The occurrence of complications is a predictor of death related to COVID-19. First, respiratory failure, where study results are similar to those found in a study carried out in Tunisia [29] but low compared to results found in China [30], This could be linked to an asymmetry of diagnostic resources in the two study contexts. Secondly, SIRS is a predictor of death in our series, the results are higher than those found in a study carried out in India for diabetics [31]. Weaknesses in infection control and prevention in hospitals and SIRS management may explain this difference. Thirdly, heart failure, which is also a predictor of death in our series, results corroborated by other authors [30]. Direct cardiac involvement in hospitalised patients is estimated at between 7 and 17%, depending on the series, and constitutes 59% of deaths related to SARS-COV 2[32]. Fourthly, thromboembolic disease is a predictor of COVID-19 mortality. COVID-19 is associated with a high thromboembolic risk, and several factors are incriminated : prolonged immobilisation, inflammation responsible for a state of hypercoagulability and endothelial dysfunction [33]. Lastly, drug reaction is also a predictor of COVID-19 mortality, in resuscitation, patients are likely to react to COVID-19 treatment or to resuscitation molecules.

Patients exposed to self-medication had poorer survival rates compared to those not exposed to self-medication. In the multivariate analysis, patients exposed to self-medication had a higher risk of dying than those not exposed to self-medication. Resorting to self-medication, especially treatments based on indigenous products, leads to delayed consultation with healthcare facilities and often results in intoxication, complicating the clinical presentation of patients. The situation could be more dramatic since the prevalence of self-medication was 6.5% in our series, while a systematic review found a prevalence of 44.78% [34]. This difference would be linked to a history focused on treatments using traditional products in our series.

Malaria comorbidity and COVID-19 is associated with better survival compared to patients who tested negative for malaria. However, a meta-analysis found a prevalence of malaria and COVID-19 co-infection of 45% and concluded that further studies are needed to fully assess the impact of COVID-19 in malaria-endemic areas [35]. Conversely, an other study in Liberia found that malaria parasitemia improved the survival of Ebola patients, where it is believed that the immunomodulatory effect of Plasmodium spp. may dampen the detrimental cytokine storm, thereby increasing survival [36]. Alternatively, the induction of natural killer (NK) cells by Plasmodium infection may explain the increased survival in co-infected individuals. Similarly, there are several examples of Plasmodium spp. causing suppression of the immune response to a secondary infection. Children with malaria and a respiratory infection were less likely to have pneumonia than children with only a respiratory infection [37].

The duration of recourse to care of more than four days from the onset of symptoms was associated with poor survival. These results are similar to those of a study carried out in Butembo [38]. From the above, we found that self-medication was associated with a delay in seeking medical care, which is one of the explanations. Also, a psychosis linked to intra-hospital deaths could explain a reluctance to seek conventional care or linked to a lack of financial access to medical care.

Limitations and strengths

We had access to patient data from four hospitals treating COVID-19 patients in the town of Goma; two further hospitals refused to give us access to patient records. This situation does not allow us to generalise the results to the entire population hospitalised for COVID-19 during our study period in the city of Goma. Given that our data source was secondary, we were confronted with problems of archiving patient records and data quality thus, several variables were not used in analysis, especially variables related to the health system and paraclinical parameters, which had an impact on the power of our study on certain variables so certain associations were not highlighted. The group of individuals exposed to self-medication is underrepresented, partly due to insufficient medical history regarding self-medication and partly due to the tendency of patients to omit their self-medication history. This study highlighted self-medication as a predictor of COVID-19-related mortality and filled the gap in the paucity of studies on COVID-19-related mortality in the city of Goma.

Conclusion

Advanced age beyond 60 years, self-medication, a history of diabetes mellitus, unemployment, and the occurrence of complications are predictors of death related to COVID-19 within 30 days of hospitalization in the city of Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo. We recommend that the health authorities of North Kivu Province adopt policies to protect elderly individuals over 60 years and those with chronic diseases such as diabetes during future COVID-19 outbreaks. It is also suggested to implement a communication program for behaviour change regarding the dangers of self-medication and early care seeking in recommended health facilities.

What is already known about the topic

- The risk factors for COVID-19 mortality are well-documented, including older age

- Having comorbidity is associated with a poorer prognosis.

What this study adds

- This study highlighted a previously unexplored predictor of COVID-19 mortality: self-medication.

- We elucidated the main predictors of COVID-19 mortality in the city of Goma

- We highlighted the lethality rate of COVID-19 in the city of Goma

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Ethics Committee of the Kinshasa Public Health School for authorising us to conduct this study under authorisation: ESP/CE/132/2024. We would also like to thank the Head of the Health Division in North Kivu and the Medical Directors of the Goma hospitals, who gave us access to the medical files in the COVID-19 treatment centres in the city of Goma. We would also like to acknowledge the support of AFENET DRC, which enabled us to carry out this work through the master’s grant in public health awarded to us.

Authors´ contributions

CKL: Conceptualisation, Data collection, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Original draft. OC: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Original draft, Final approval. CSR: Data collection. KKM: Review & editing, Final approval, NMA: Investigation, Final approval, LL: Investigation, Final approval. WW: Review & editing, Original draft. PKD: Conceptualisation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Final approval.

Abbreviations AFENET: African Field Epidemiology Network CTCo: COVID-19 treatment centre. ISARIC WHO CCP-UK: International Severe Acute Respiratory Infection Consortium – Coronavirus Clinical Characterisation Consortium in the United Kingdom. SIRS: Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome

| Characteristic | Overall, N = 400 | Self-medication | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, N = 374 | Yes, N = 26 | p-value | ||

| Length of hospital stay, median (IQR) | 9 (6, 13) | 10 (6, 13) | 6 (2, 10) | 0.011 |

| Status, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Alive | 312 (78) | 299 (80) | 13 (50) | |

| Deaths | 88 (22) | 75 (20) | 13 (50) | |

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 50 (34, 65) | 50 (34, 65) | 59 (43, 68) | 0.065 |

| Age (years), n (%) | 0.4 | |||

| <20 | 11 (2.8) | 11 (2.9) | 0 (0) | |

| 20–39 | 127 (32) | 122 (33) | 5 (19) | |

| 40–59 | 115 (29) | 107 (29) | 8 (31) | |

| ≥60 | 146 (37) | 133 (36) | 13 (50) | |

| Gender of patient, n (%) | 0.8 | |||

| Female | 162 (41) | 151 (40) | 11 (42) | |

| Male | 238 (59) | 223 (60) | 15 (58) | |

| Civil status, n (%) | 0.3 | |||

| Married or common-law | 161 (64) | 147 (64) | 14 (70) | |

| Single | 56 (22) | 54 (23) | 2 (10) | |

| Divorced or separated | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Widower | 33 (13) | 29 (13) | 4 (20) | |

| Profession, n (%) | 0.5 | |||

| Healthcare professional | 39 (13) | 38 (14) | 1 (4.3) | |

| No profession | 121 (40) | 111 (40) | 10 (43) | |

| Others | 140 (47) | 128 (46) | 12 (52) | |

| History of hypertension, n (%) | 0.8 | |||

| No | 239 (70) | 221 (69) | 18 (72) | |

| Yes | 104 (30) | 97 (31) | 7 (28) | |

| History of diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 0.8 | |||

| No | 256 (75) | 238 (75) | 18 (72) | |

| Yes | 87 (25) | 80 (25) | 7 (28) | |

| History of HIV, n (%) | 0.089 | |||

| No | 329 (98) | 306 (98) | 23 (92) | |

| Yes | 7 (2.1) | 5 (1.6) | 2 (8.0) | |

| History of heart disease, n (%) | 0.6 | |||

| No | 322 (96) | 297 (96) | 25 (100) | |

| Yes | 13 (3.9) | 13 (4.2) | 0 (0) | |

| 1 Median (IQR); n (%) 2 Wilcoxon rank sum test; Pearson’s Chi-squared test; Fisher’s exact test | ||||

| Characteristic | Overall, N = 400 | Self-medication | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, N = 374 | Yes, N = 26 | p-value | ||

| Respiratory rate, median (IQR) | 22 (20, 27) | 22 (20, 26) | 26 (20, 36) | 0.077 |

| Heart rate, median (IQR) | 92 (81, 105) | 92 (81, 105) | 98 (86, 110) | 0.2 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure, median (IQR) | 127 (113, 142) | 127 (114, 142) | 129 (112, 151) | 0.7 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure, median (IQR) | 80 (70, 90) | 80 (70, 90) | 80 (70, 87) | 0.6 |

| Duration between symptom onset and care, median (IQR) | 4 (3, 7) | 4 (3, 7) | 7 (3, 12) | 0.032 |

| Clinical stage at admission, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Mild | 132 (33) | 129 (34) | 3 (12) | |

| Moderate | 135 (34) | 130 (35) | 5 (19) | |

| Severe | 105 (26) | 90 (24) | 15 (58) | |

| Critical | 28 (7.0) | 25 (6.7) | 3 (12) | |

| Oxygen saturation, n (%) | 0.020 | |||

| SaO2 ≥95% | 161 (43) | 156 (45) | 5 (19) | |

| SaO2 <90% | 142 (38) | 126 (36) | 16 (62) | |

| SaO2 90–94% | 73 (19) | 68 (19) | 5 (19) | |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome, n (%) | 0.002 | |||

| No | 301 (75) | 288 (77) | 13 (50) | |

| Yes | 99 (25) | 86 (23) | 13 (50) | |

| Temperature, n (%) | 0.030 | |||

| Normal | 280 (71) | 267 (73) | 13 (50) | |

| Hypothermia | 6 (1.5) | 6 (1.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Fever | 106 (27) | 93 (25) | 13 (50) | |

| Obesity status, n (%) | 0.8 | |||

| No | 332 (89) | 308 (89) | 24 (92) | |

| Yes | 42 (11) | 40 (11) | 2 (7.7) | |

| Complications, n (%) | 0.002 | |||

| Not documented / None | 243 (61) | 236 (63) | 7 (27) | |

| Respiratory failure | 112 (28) | 100 (27) | 12 (46) | |

| Heart failure | 7 (1.8) | 5 (1.3) | 2 (7.7) | |

| Thromboembolic diseases | 3 (0.8) | 3 (0.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Stroke | 5 (1.3) | 5 (1.3) | 0 (0) | |

| SIRS | 26 (6.5) | 21 (5.6) | 5 (19) | |

| Drug reaction | 3 (0.8) | 3 (0.8) | 0 (0) | |

| 1 Median (IQR); n (%) 2 Wilcoxon rank sum test; Fisher’s exact test; Pearson’s Chi-squared test | ||||

| Characteristic | Overall, N = 400 | Self-medication | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, N = 374 | Yes, N = 26 | p-value | ||

| Malaria, n (%) | >0.9 | |||

| Negative | 129 (88) | 116 (87) | 13 (93) | |

| Positive | 18 (12) | 17 (13) | 1 (7.1) | |

| D-dimer concentration (µg/l), n (%) | 0.7 | |||

| <500 | 59 (72) | 50 (70) | 9 (82) | |

| ≥500 | 23 (28) | 21 (30) | 2 (18) | |

| C-reactive protein concentration (mg/l), n (%) | 0.047 | |||

| <6 | 25 (15) | 25 (17) | 0 (0) | |

| ≥6 | 138 (85) | 119 (83) | 19 (100) | |

| White blood cell count, n (%) | 0.076 | |||

| 4000–10000 | 129 (63) | 118 (64) | 11 (52) | |

| <4000 | 17 (8.3) | 17 (9.3) | 0 (0) | |

| >10000 | 58 (28) | 48 (26) | 10 (48) | |

| Granulocyte count, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 550–7500 | 136 (67) | 129 (71) | 7 (33) | |

| <550 | 3 (1.5) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (9.5) | |

| >7500 | 64 (32) | 52 (29) | 12 (57) | |

| Blood glucose concentration (mmol/l), n (%) | >0.9 | |||

| 4–6 | 42 (32) | 38 (33) | 4 (29) | |

| <4 | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0) | |

| ≥7 | 87 (67) | 77 (66) | 10 (71) | |

| Creatinine concentration (µmol/l), n (%) | 0.2 | |||

| M ≤120 / F ≤100 | 71 (65) | 61 (62) | 10 (83) | |

| M >120 / F >100 | 39 (35) | 37 (38) | 2 (17) | |

| Chest radiograph, n (%) | >0.9 | |||

| Normal | 4 (7.3) | 4 (8.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Bilateral lesions | 47 (85) | 41 (84) | 6 (100) | |

| Unilateral lesions | 4 (7.3) | 4 (8.2) | 0 (0) | |

1 n (%) 2 Fisher’s exact test | ||||

References

- Secrétariat Général à la Santé de la République Démocratique du Congo. Covid-19 Coronavirus Pandemic Management Guidelines [Internet]. Kinshasa (Democratic Republic of Congo): Secrétariat Général à la Santé de la République Démocratique du Congo; 2020 Apr [cited 2026 Jan 19]. Available from: https://www.sante.gouv.cd

- WHO AFRO. Democratic Republic of Congo [Internet]. Brazzaville (Republic of Congo): OMS; c2025 [cited 2026 Jan 19]. French. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/fr/countries/democratic-republic-congo

- Institut national de santé publique du Québec. COVID-19: Epidemiological and Clinical Fact Sheet [COVID-19 : Fiche épidémiologique et clinique] [Internet]. Québec (Canada): Gouvernement du Québec; c2026 [cited 2026 Jan 19]. French. Available from: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/publications/2901-caracteristiques-epidemiologiques-cliniques-covid19

- Owings L. Africa ‘not ready’ for COVID-19 mental health issues [Internet]. Oxfordshire (UK): SciDev.Net; 2020 Apr 24 [cited 2026 Jan 19]. Available from: https://www.scidev.net/sub-saharan-africa/news/africa-not-ready-for-covid-19-mental-health-issues/

- Sadio AJ, Gbeasor-Komlanvi FA, Konu RY, Bakoubayi AW, Tchankoni MK, Bitty-Anderson AM, Gomez IM, Denadou CP, Anani J, Kouanfack HR, Kpeto IK, Salou M, Ekouevi DK. Assessment of self-medication practices in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak in Togo. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Jan 06 [cited 2026 Jan 19];21(1):58. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-10145-1 Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-020-10145-1

- United Nations. Covid-19: WHO calls on Africa to prepare for the worst and avoid mass gatherings [Covid-19 : l’OMS appelle l’Afrique à se préparer au pire et à éviter les rassemblements de masse] [Internet]. New York (NY): United Nations; 2020 Mar 19 [cited 2026 Jan 19]. French. Available from: https://news.un.org/fr/story/2020/03/1064432

- World Health Organization Africa. WHO supports scientifically-proven traditional medicine [Internet]. Brazzaville (Switzerland): WHO AFRO; 2020 May 04 [cited 2026 Jan 19]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/news/who-supports-scientifically-proven-traditional-medicine

- Hernandez-Juyol M, Job-Quesada JR. Dentistry and self-medication: a current challenge. Med Oral [Internet]. 2002 Nov-Dec [cited 2026 Jan 19];7(5):344–7. Available from: https://www.medicinaoral.com/pubmed/medoralv7_i5_p344.pdf

- Manasi SL. COVID-19 and self-medication in the Democratic Republic of Congo [COVID-19 et automédication en République Démocratique du Congo]. Le Carrefour Congolais [Internet]. 2023 Sep 6 [cited 2026 Jan 19];5(1):111–117. French. Available from: https://lecarrefourcongolais.org/2021-5/lubanza

- Mudenda S, Witika BA, Sadiq MJ, Banda M, Mfune RL, Daka V, Kalui D, Phiri MN, Kasanga M, Mudenda F, Mufwambi W. Self-medication and its consequences during & after the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: a global health problem. EUROPEAN J ENV PUBLI [Internet]. 2020 Nov 30 [cited 2026 Jan 19];5(1):em0066. doi:10.29333/ejeph/9308 Available from: https://www.ejeph.com/article/self-medication-and-its-consequences-during-after-the-coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-pandemic-a-9308

- Okoye OC, Adejumo OA, Opadeyi AO, Madubuko CR, Ntaji M, Okonkwo KC, Edeki IR, Agboje UO, Alli OE, Ohaju-Obodo JO. Self medication practices and its determinants in health care professionals during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Pharm [Internet]. 2022 Jan 12 [cited 2026 Jan 19];44(2):507–16. doi:10.1007/s11096-021-01374-4 Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11096-021-01374-4

- Gaviria-Mendoza A, Mejía-Mazo DA, Duarte-Blandón C, Castrillón-Spitia JD, Machado-Duque ME, Valladales-Restrepo LF, Machado-Alba JE. Self-medication and the ‘infodemic’ during mandatory preventive isolation due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety [Internet]. 2022 Jan [cited 2026 Jan 19];13:20420986221072376. doi:10.1177/20420986221072376 Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/20420986221072376

- Ouédraogo AR, Bougma G, Baguiya A, Sawadogo A, Kaboré PR, Minougou CJ, Diendéré A, Maiga S, Agbaholou CR, Hema A, Sondo A, Ouédraogo G, Sanou A, Ouedraogo M. Factors associated with the occurrence of acute respiratory distress and death in patients with COVID-19 in Burkina Faso [Facteurs associés à la survenue de détresse respiratoire aiguë et de décès chez les patients atteints de COVID-19 au Burkina Faso]. Revue des Maladies Respiratoires [Internet]. 2021 Feb 05 [Version of record 2021 Mar 17; cited 2026 Jan 19];38(3):240–8. French. doi:10.1016/j.rmr.2021.02.001 Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0761842521000383

- World Health Organization. Estimating mortality from COVID-19: Scientific brief, 4 August 2020 [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2020 Aug 04 [cited 2026 Jan 19]. 4 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci-Brief-Mortality-2020.1

- Bepouka BI, Mandina M, Makulo JR, Longokolo M, Odio O, Mayasi N, Pata T, Nsangana G, Tshikangu F, Mangala D, Maheshe D, Nkarnkwin S, Muamba J, Ndaie G, Ngwizani R, Yanga Y, Nkodila A, Keke H, Kokusa Y, Lepira F, Kashongwe I, Mbula M, Kayembe JM, Situakibanza H. Predictors of mortality in covid-19 patients at kinshasa university hospital, democratic republic of the congo (From march to june 2020). Pan Afr Med J [Internet]. 2020 Oct 01 [cited 2026 Jan 19];37:105. doi:10.11604/pamj.2020.37.105.25279 Available from: https://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/37/105/full

- Kumar A, Arora A, Sharma P, Anikhindi SA, Bansal N, Singla V, Khare S, Srivastava A. Is diabetes mellitus associated with mortality and severity of COVID-19? A meta-analysis. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews [Internet]. 2020 May 06 [cited 2026 Jan 19];14(4):535–45. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.044 Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1871402120301090

- Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, Bacon S, Bates C, Morton CE, Curtis HJ, Mehrkar A, Evans D, Inglesby P, Cockburn J, McDonald HI, MacKenna B, Tomlinson L, Douglas IJ, Rentsch CT, Mathur R, Wong AYS, Grieve R, Harrison D, Forbes H, Schultze A, Croker R, Parry J, Hester F, Harper S, Perera R, Evans SJW, Smeeth L, Goldacre B. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature [Internet]. 2020 Jul 08 [cited 2026 Jan 19];584(7821):430–6. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4 Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-2521-4

- Bajaj V, Gadi N, Spihlman AP, Wu SC, Choi CH, Moulton VR. Aging, immunity, and covid-19: how age influences the host immune response to coronavirus infections? Front Physiol [Internet]. 2021 Jan 12 [cited 2026 Jan 19];11:571416. doi:10.3389/fphys.2020.571416 Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2020.571416/full

- Kamle S, Ma B, He CH, Akosman B, Zhou Y, Lee CM, El-Deiry WS, Huntington K, Liang O, Machan JT, Kang MJ, Shin HJ, Mizoguchi E, Lee CG, Elias JA. Chitinase 3-like-1 is a therapeutic target that mediates the effects of aging in COVID-19. JCI Insight [Internet]. 2021 Nov 8 [cited 2026 Jan 19];6(21):e148749. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.148749 Available from: https://insight.jci.org/articles/view/148749

- Mirahmadizadeh A, Shamooshaki MTB, Dadvar A, Moradian MJ, Aryaie M. Unemployment and COVID-19-related mortality: a historical cohort study of 50,000 COVID-19 patients in Fars, Iran. Epidemiol Health [Internet]. 2022 Mar 12 [cited 2026 Jan 19];44:e2022032. doi:10.4178/epih.e2022032 Available from: http://e-epih.org/journal/view.php?doi=10.4178/epih.e2022032

- WHO AFRO. Noncommunicable diseases increase risk of dying from COVID-19 in Africa [Les maladies non transmissibles augmentent le risque de mourir de la COVID-19 en Afrique] [Internet]. Brazzaville (Republic of Congo): WHO AFRO; 2020 Sep 10 [cited 2026 Jan 19]. French. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/fr/news/les-maladies-non-transmissibles-augmentent-le-risque-de-mourir-de-la-covid-19-en-afrique

- Pranata R, Henrina J, Raffaello WM, Lawrensia S, Huang I. Diabetes and COVID-19: The past, the present, and the future. Metabolism [Internet]. 2021 Jun 11 [cited 2026 Jan 19];121:154814. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2021.154814 Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0026049521001141

- Jafar N, Edriss H, Nugent K. The effect of short-term hyperglycemia on the innate immune system. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences [Internet]. 2016 Feb 17 [cited 2026 Jan 19];351(2):201–11. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2015.11.011 Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0002962915000270

- Rao S, Lau A, So HC. Exploring diseases/traits and blood proteins causally related to expression of ace2, the putative receptor of sars-cov-2: a mendelian randomization analysis highlights tentative relevance of diabetes-related traits. Diabetes Care [Internet]. 2020 May 19 [cited 2026 Jan 19];43(7):1416–26. doi:10.2337/dc20-0643 Available from: https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/43/7/1416/35591/Exploring-Diseases-Traits-and-Blood-Proteins

- Zhang H, Penninger JM, Li Y, Zhong N, Slutsky AS. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (Ace2) as a SARS-CoV-2 receptor: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic target. Intensive Care Med [Internet]. 2020 Mar 03 [cited 2026 Jan 19];46(4):586–90. doi:10.1007/s00134-020-05985-9 Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00134-020-05985-9

- Lim S, Bae JH, Kwon HS, Nauck MA. COVID-19 and diabetes mellitus: from pathophysiology to clinical management. Nat Rev Endocrinol [Internet]. 2020 Nov 13 [cited 2026 Jan 19];17(1):11–30. doi:10.1038/s41574-020-00435-4 Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41574-020-00435-4

- Kim JH, Park K, Lee SB, Kang S, Park JS, Ahn CW, Nam JS. Relationship between natural killer cell activity and glucose control in patients with type 2 diabetes and prediabetes. J Diabetes Investig [Internet]. 2019 Jan 07 [cited 2026 Jan 19];10(5):1223–8. doi:10.1111/jdi.13002 Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jdi.13002

- Memisa Belgium. Diabetes screening: a challenge in the Democratic Republic of Congo [Dépistage du diabète : un défi en République Démocratique du Congo] [Internet]. Brussels (Belgium): Memisa Belgium; 2024 Nov 12 [cited 2026 Jan 19]. French. Available from: https://memisa.be/fr/depistage-diabete-congo/

- Kacem A, Karaborni B, Jazia RB, Kharrat I, Tabka O, Maatallah A, Chebil D, Merzougui L, Ayechi J. Predictive factors of mortality in patients hospitalized for COVID-19 pneumonia [Facteurs prédictifs de mortalité chez les patients hospitalisés pour pneumonie à COVID-19]. Revue des Maladies Respiratoires Actualités [Internet]. 2023 Jan 13 [cited 2026 Jan 19];15(1):210. French. doi:10.1016/j.rmra.2022.11.370 Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1877120322005407

- Wang L, He W, Yu X, Hu D, Bao M, Liu H, Zhou J, Jiang H. Coronavirus disease 2019 in elderly patients: Characteristics and prognostic factors based on 4-week follow-up. J Infect [Internet]. 2020 Mar 30 [cited 2026 Jan 19];80(6):639–45. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.019 Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0163445320301468

- Nair AM, Gopalan S, Rajendran V, Varadaraj P, Marappa L, Pandurangan V, Madhavan S, Mani R, Bhaskar E. Role of secondary sepsis in COVID-19 mortality: Observations on patients with preexisting diabetes mellitus and newly diagnosed hyperglycemia. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis [Internet]. 2022 Apr 12 [cited 2026 Jan 19];92(4):2037. doi:10.4081/monaldi.2022.2037 Available from: https://www.monaldi-archives.org/index.php/macd/article/view/2037

- El Boussadani B, Benajiba C, Aajal A, Ait Brik A, Ammour O, El Hangouch J, Oussama O, Oussama B, Tahiri N, Raissuni Z. COVID-19 pandemic: impact on the cardiovascular system. Data available as of April 1, 2020 [Pandémie COVID-19 : impact sur le système cardiovasculaire. Données disponibles au 1er avril 2020]. Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris) [Internet]. 2020 Apr 07 [cited 2026 Jan 19];69(3):107–14. French. doi:10.1016/j.ancard.2020.04.001 Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0003392820300561

- Killerby ME. Characteristics associated with hospitalization among patients with covid-19 — metropolitan atlanta, georgia, march–april 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2020 Jun 26 [cited 2026 Jan 19];69(25):790–794. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6925e1 Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6925e1.htm

- Shrestha AB, Aryal M, Magar JR, Shrestha S, Hossainy L, Rimti FH. The scenario of self-medication practices during the covid-19 pandemic; a systematic review. Ann Med Surg (Lond) [Internet]. 2022 Aug 27 [cited 2026 Jan 19];82:104482. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104482 Available from: https://journals.lww.com/10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104482

- Rouamba J. Covid-19 in malaria-endemic areas: current situation [Covid-19 dans les zones d’endémie palustre : situation actuelle]. Cahiers de l’IREA [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2026 Jan 19];45:77. French. Available from: https://openurl.ebsco.com/EPDB%3Agcd%3A13%3A2851005/detailv2?sid=ebsco%3Aplink%3Acrawler&id=ebsco%3Agcd%3A155349825&crl=f&link_origin=none

- Rosenke K, Adjemian J, Munster VJ, Marzi A, Falzarano D, Onyango CO, Ochieng M, Juma B, Fischer RJ, Prescott JB, Safronetz D, Omballa V, Owuor C, Hoenen T, Groseth A, Martellaro C, Van Doremalen N, Zemtsova G, Self J, Bushmaker T, McNally K, Rowe T, Emery SL, Feldmann F, Williamson BN, Best SM, Nyenswah TG, Grolla A, Strong JE, Kobinger G, Bolay FK, Zoon KC, Stassijns J, Giuliani R, De Smet M, Nichol ST, Fields B, Sprecher A, Massaquoi M, Feldmann H, De Wit E. Plasmodium parasitemia associated with increased survival in ebola virus–infected patients. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2016 Oct 15 [cited 2026 Jan 19];63(8):1026–33. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw452 Available from: https://academic.oup.com/cid/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/cid/ciw452

- D’Acremont V, Kilowoko M, Kyungu E, Philipina S, Sangu W, Kahama-Maro J, Lengeler C, Cherpillod P, Kaiser L, Genton B. Beyond malaria — causes of fever in outpatient tanzanian children. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2014 Feb 27 [cited 2026 Jan 19];370(9):809–17. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1214482 Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1214482

- Akilimali PZ, Kayembe DM, Muhindo NM, Tran NT. Predictors of mortality among inpatients in COVID-19 treatment centers in the city of Butembo, North Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo. Croda J, editor. PLOS Glob Public Health [Internet]. 2024 Jan 24 [cited 2026 Jan 19];4(1):e0002020. doi:10.1371/journal.pgph.0002020 Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0002020