Research | Open Access | Volume 9 (1): Article 15 | Published: 22 Jan 2026

Evaluation of antibiotic prescription rates, Bono Region, Ghana, 2017-2022

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Tables

| Variables | No. of respondents (n=152) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 45 | 29.6 |

| Male | 107 | 70.4 |

| Cadre of prescribers | ||

| Doctors | 87 | 57.2 |

| Physician Assistants | 65 | 42.8 |

| Number of years in service | ||

| Less than 5 years | 59 | 38.8 |

| 5 to 10 years | 38 | 25.0 |

| More than 10 years | 55 | 36.2 |

| Number of years in the current facility | ||

| Less than 5 years | 94 | 61.8 |

| 5 to 10 years | 50 | 32.9 |

| More than 10 years | 8 | 5.3 |

| Distribution of Prescribers | ||

| Banda | 2 | 1.3 |

| Berekum East | 2 | 1.3 |

| Berekum West | 3 | 2.0 |

| Dormaa East | 4 | 2.6 |

| Dormaa Municipal | 4 | 2.6 |

| Dormaa West | 5 | 3.3 |

| Jaman North | 10 | 6.6 |

| Jaman South | 7 | 4.6 |

| Sunyani East | 84 | 55.3 |

| Sunyani West | 13 | 8.6 |

| Tain | 12 | 7.9 |

| Wenchi | 6 | 3.2 |

Table 1: Sociodemographic Characteristics of Prescribers, Bono Region, 2022

| Facility Name | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bono Regional Hospital | 0 | 0 | 35 | 72.2 | 48.9 | 38.3 |

| Chiraa Government Hospital | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29.5 |

| Dormaa East District Hospital | 0 | 0 | 0 | 112.5 | 43.3 | 27.5 |

| Presbyterian Hospital, Dormaa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 60 |

| Dormaa West District Hospital | 0 | 0 | 77.7 | 30 | 36.7 | 39.2 |

| Drobo St Mary Hospital | 47.5 | 30 | 22.5 | 21.8 | 35 | 46.7 |

| Holy Family Hospital, Berekum | 0 | 0 | 24.4 | 26.7 | 63.3 | 26.3 |

| Methodist Hospital, Wenchi | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 43.3 | 30 |

| Sampa Government Hospital | 0 | 0 | 0 | 79.4 | 133.3 | 25 |

| Sunyani Municipal Hospital | 57.5 | 62.2 | 70 | 69.2 | 63.3 | 38.3 |

| Sunyani SDA Hospital | 0 | 20 | 36.7 | 31.7 | 38.2 | 28.3 |

| Tain District Hospital | 26.7 | 25.6 | 16.7 | 30 | 37.8 | 36.7 |

Source: DHIMS 2

Footnote: “0 indicates that the facility did not report on the quarterly antibiotic surveillance report for that period.”

Table 2: Hospital Contribution to Percentage of Encounters with an Antibiotic Prescribed, 2017 to 2022

| Socio-demographic Characteristics | No. of Respondents | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 10 | 71.4 |

| Female | 4 | 28.6 |

| Cadre of Respondent | ||

| Pharmacist | 6 | 42.9 |

| Medical Officer | 5 | 35.7 |

| Health Information Officer | 3 | 21.4 |

| Number of Years in Service | ||

| Less than 5 years | 2 | 14.3 |

| 5 to 10 years | 5 | 35.7 |

| More than 10 years | 7 | 50.0 |

| Number of Years in the Current Facility | ||

| Less than 5 years | 4 | 28.6 |

| 5 to 10 years | 5 | 35.7 |

| More than 10 years | 5 | 35.7 |

| Number of Respondents from Facilities | ||

| More than 1 respondent | 2 | 16.7 |

| Only 1 respondent | 10 | 83.3 |

| Number of Respondents from District | ||

| More than 1 respondent | 1 | 8.3 |

| Only 1 respondent | 9 | 75.0 |

| No respondent | 2 | 16.7 |

Table 3: Socio-demographic Characteristics of Respondents

Figures

Keywords

- Antibiotic

- Drug use

- Ghana

- Prescription

- Rational

- Resistance

Eric Kofi Nyarko1, Emmanuel Obeng-Hinneh1, Georgia Ghartey2,&, Stephen Kwame Korang1, Emmanuel George Bachan1, Prince Quarshie1, Kofi Amo-Kodieh1, Patrick Kuma Aboagye3

1Bono Regional Health Directorate, Ghana Health Service, Ghana, 2Ghana Field Epidemiological and Laboratory Training Program, School of Public Health, University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana, 3Ghana Health Service, Headquarters, Accra, Ghana

&Corresponding author: Georgia Ghartey, Ghana Field Epidemiological and Laboratory Training Program, School of Public Health, University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana, Email: gharteyg@yahoo.com, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-5568-6175

Received: 15 Feb 2025, Accepted: 21 Jan 2026, Published: 22 Jan 2026

Domain: Antimicrobial Resistance

Keywords: Antibiotic, drug use, Ghana, prescription, rational, resistance

©Eric Kofi Nyarko et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Eric Kofi Nyarko et al., Evaluation of antibiotic prescription rates, Bono Region, Ghana, 2017-2022. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2026; 9(1):15. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00049

Abstract

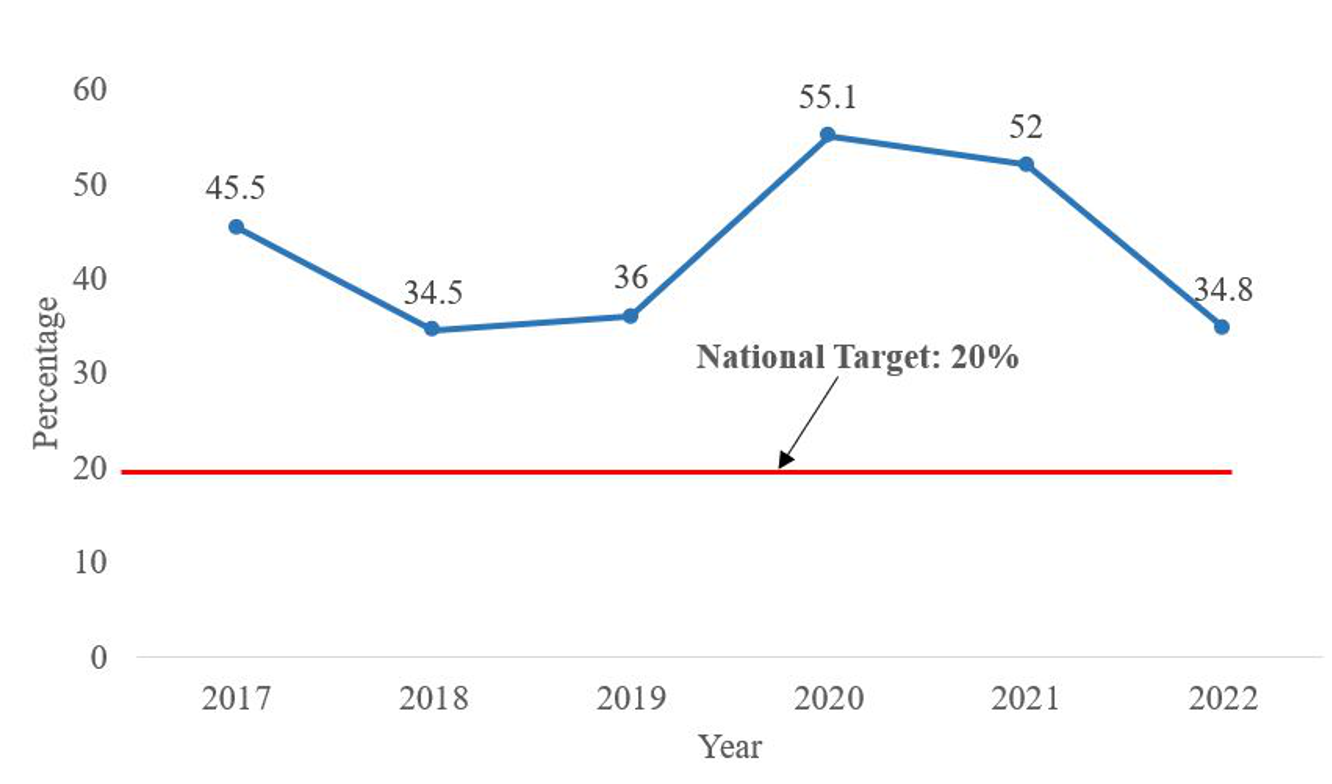

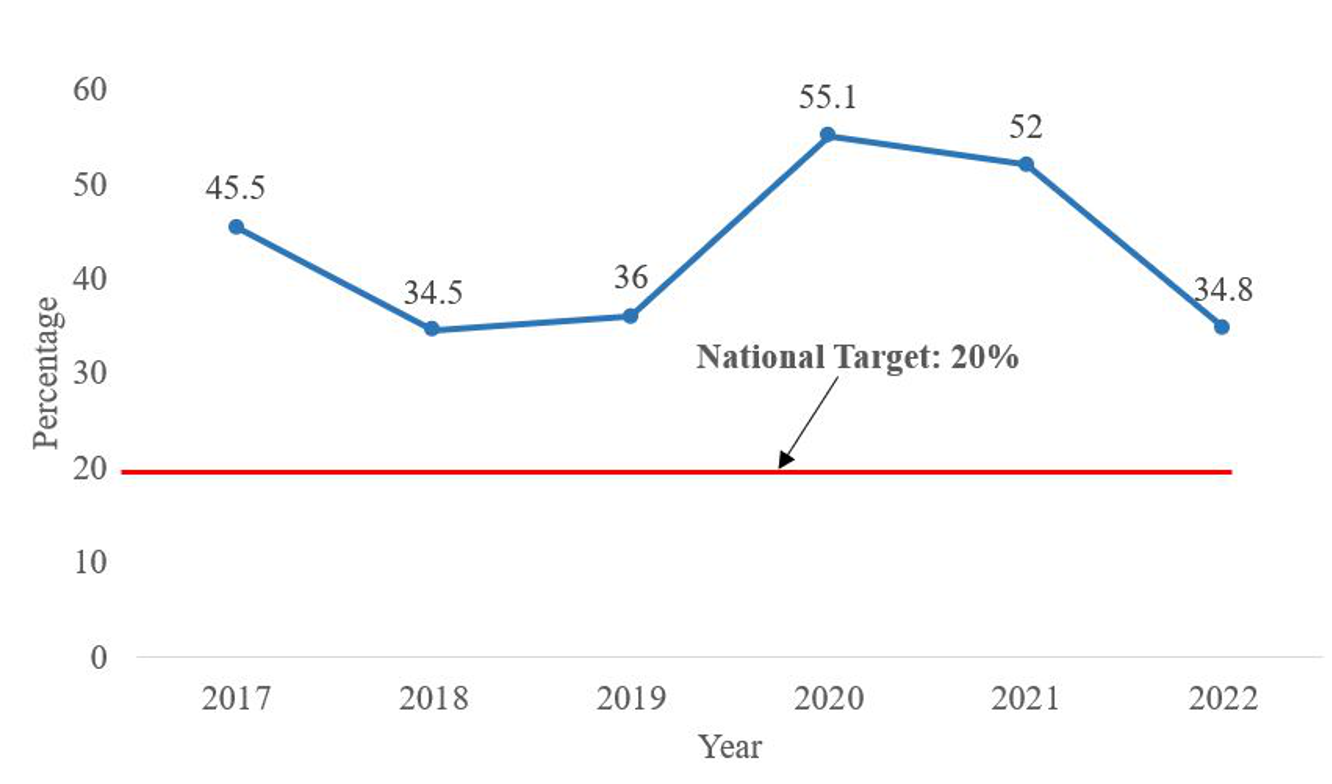

Introduction: Approximately 50% of prescriptions globally, including antibiotics, are done improperly. Ghana and Bono Region recorded 47% and 52% antibiotic prescription rates, respectively, in 2021, above the WHO’s standard of 20.0%-26.8%. These high antibiotic prescription rates demonstrate poor antimicrobial stewardship and have a poor public health impact on the region and Ghana. We determined the rates of antibiotic prescription and the factors associated with it in the Bono Region.

Methods: We evaluated the prescription rates of antibiotics in the Bono region using secondary data. Hospitals that submitted a Quarterly Rational Use of Medicine Report in the District Health Information Management System 2 from 2017-2022 were included in the evaluation, and these hospitals’ Rational Use of Medicine surveillance staff were selected for key informant interviews (KII). Quantitative data was analyzed by person, place and time. Recordings from the KII were aligned to themes and triangulated with quantitative results.

Result: Only 4.4% of facilities reported on rational medicine use. Antibiotic prescription rates ranged from 34.8% to 55.1%, exceeding targets. Findings from both quantitative and qualitative data highlighted key drivers of high antibiotic use: nonadherence to treatment guidelines, inadequate diagnostics, limited trained prescribers, weak antimicrobial stewardship, supply chain issues, and poor community infection control.

Conclusion: This evaluation revealed that antibiotic prescription in facilities in the Bono Region is high. We recommended that facility managers institute antimicrobial stewardship subcommittees, train prescribers on the rational use of antibiotics, and improve the capacities of laboratories to conduct culture and sensitivity testing.

Introduction

Rational Antibiotic Prescription (RAP) refers to the purposeful and appropriate antibiotic prescription with the correct dose and course to produce the maximum benefits and minimal side effects [1]. Studies have shown that approximately 50% of all medications, including antibiotics, are prescribed improperly globally [2–4]. A study conducted in Ghana, Uganda, Zambia and Tanzania showed that approximately 50% of patients reporting to health facilities were prescribed antibiotics, higher than the expected WHO standard of 20% to 26.8% [2]. In Ghana, the percentages of encounters with antibiotics prescribed in 2021 and 2022 were 47% and 45.2% respectively [5].

The irrational prescription of drugs, specifically antibiotics, has been shown to greatly influence antibiotic resistance in populations [6]. According to the WHO, bacterial antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is thought to have contributed to 4.95 million fatalities worldwide in 2019 and been directly responsible for 1.27 million deaths [7]. A 2021 study reported that, across Africa, the pooled prevalence of bacterial resistance to certain antibiotics ranged from 17.4% to 75.8% [8]. In Ghana, antibiotic resistance was estimated to be as high as 82% among patients presenting with bacterial diseases in regional and teaching hospitals [9]. The Bono region reported a high antibiotic prescription rate of 52% during its 2021 annual performance review meeting[5].

As part of efforts to ensure antimicrobial stewardship, and to prevent antimicrobial resistance, the Ghana Health Service monitors rational drug prescription in health facilities through the Quarterly Evaluation of Rational Use of Medicine, using the WHO/International Network of Rational Use of Drugs (INRUD) Core Drug Use Indicators [10]. The rational use of prescription indicators that are reported in the District Health Information Management System (DHIMS II) include; the average number of medicines prescribed per patient encounter, percentage of encounters with an injection prescribed, percentage of medicines prescribed by generic name, and percentage of prescriptions with antibiotics [11].

Although these problems identified are of great public health significance, there is still a dearth of literature on rational antibiotic prescription and the factors that influence rational antibiotic prescription, specific to the Bono regional context. Studying the rational prescription of antibiotics and the factors associated with them in the region will contribute to informed decisions and actions that will improve antibiotic prescription in the region and the country as a whole. This evaluation determined the rates of antibiotic prescription and factors associated with antibiotic prescription in health facilities in the Bono Region.

Methods

Evaluation design and setting

Using a descriptive cross-sectional study design, we conducted this evaluation to describe the rational prescription rates of antibiotics in the Bono region from 2017 to 2022. This evaluation was carried out in February 2023. We used both quantitative and qualitative methods.

The Bono region is one of the 16 administrative regions of Ghana, with Sunyani as its regional capital. The Bono region has an estimated population of 1,234,031 and 12 subregional administrative districts[12]. There are 272 health facilities in the region, with 210 being public facilities and 62 being private facilities. The region has 1 regional hospital and 18 primary-level hospitals, 10 of which are district-designated hospitals. Six of the hospitals are private hospitals. The top 10 OPD cases that were reported by all health facilities in DHIMS 2 in 2022 were uncomplicated malaria, upper respiratory tract infections, rheumatism/other joint pains/arthritis, diarrhoea diseases, acute urinary tract infections, skin diseases, intestinal worms, anaemia, typhoid fever and acute eye infection.

Sampling

All health facilities that were reporting on the rational antibiotic prescription indicator using the Quarterly Rational Use of Medicine Report were included. In each facility, the rational use of medicine (RUM) surveillance staff who were responsible for collecting RUM data and reporting them into the DHIMS2 were selected as key informants. Prescriber data were not sampled but represented a census of all prescribers in the region at the time of the study and were presented descriptively. All trained staff in RUM surveillance were included as key informants. All trained staff in RUM surveillance who could not be reached by phone call during the study were excluded from the study.

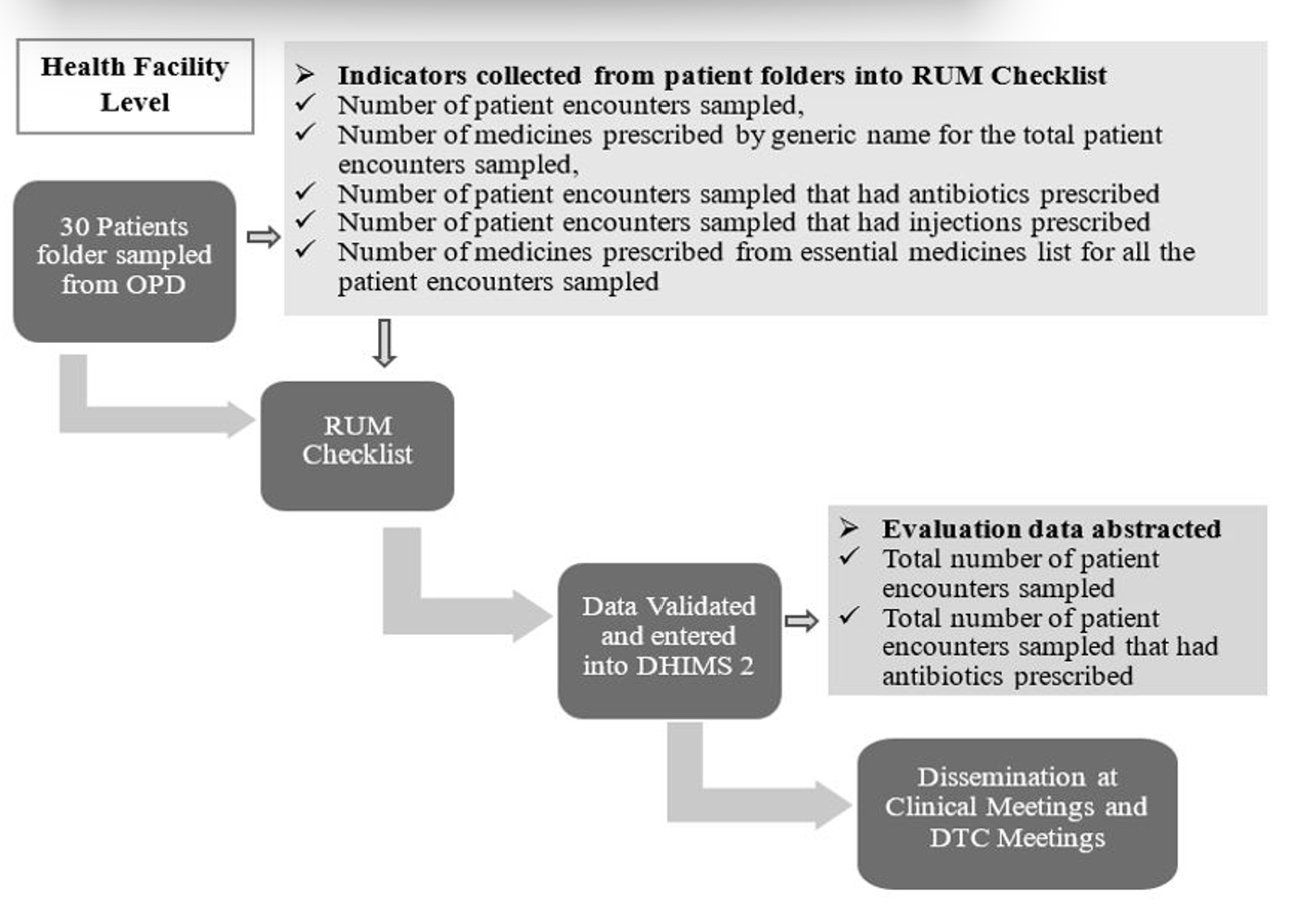

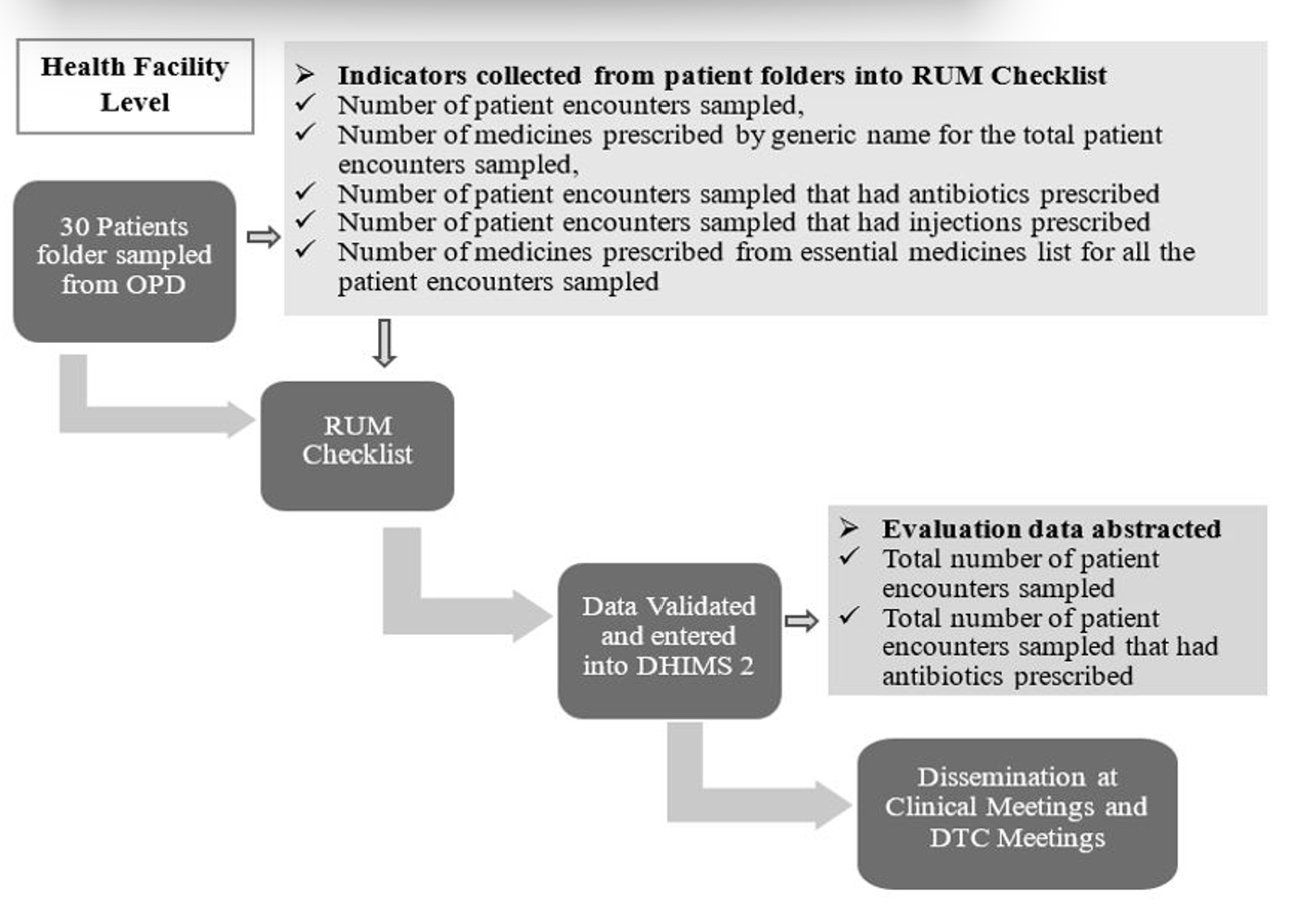

Data source

The Quarterly Rational Use of Medicines Reports data are collated by facilities using a standard data collection checklist. The data elements captured on this checklist are the total number of patient encounters sampled, total number of medicines prescribed by generic name for the total patient encounters sampled, total number of patient encounters sampled that had antibiotics prescribed, total number of patient encounters sampled that had injections prescribed and total number of medicines prescribed from the essential medicines list for all the patient encounters sampled. At least 30 folders (case notes) of patients who visited the facility in the last three months were selected at random by the team responsible for the survey at the facility. Information on their last Outpatient Department (OPD) visit is captured based on the data elements on the checklist. Specialized clinics and inpatient data are not included in this survey. The data elements picked are aggregated and entered into DHIMS 2 for that quarter. Findings from this survey are disseminated during Drug and Therapeutic Council (DTC) meetings, Clinical meetings and other meetings to solicit inputs into improving the rational use of medicines (Figure 1).

Data collection

We extracted quarterly RUM reports from DHIMS2. Variables collected from the reports included the total number of patient encounters sampled and the total number of patient encounters sampled that had antibiotics prescribed. Demographic data on prescribers were abstracted from the Human Resource Information Management System (HRIMS) of the Ghana Health Service into Microsoft Excel (Version 2108) and analyzed to identify the distribution of prescribers in the region.

Using a semi-structured questionnaire and interview guide, we conducted key informant interviews among the selected RUM surveillance staff to understand the key factors associated with antibiotic prescription in the facilities. Sociodemographic data, rational use of antibiotics and further probing of the reason for prescription were collected from the participants. Interviews were conducted via phone calls and recorded. Responses were transcribed thematically.

The themes assessed during the key informant interview were as follows: Use of standard treatment guidelines and antibiotic stewardship; Availability of culture and sensitivity testing; Supply chain management; Dissemination of the Rational Use of Medicine survey results and Data Quality.

Operational definition and data analysis

Rational antibiotic prescription rate: The proportion of patient encounters sampled that were prescribed antibiotics at health facilities (not more than 20%). The abstracted data were cleaned using Microsoft Excel (version 2108). Descriptive analysis by person, place and time was performed on quantitative data using Microsoft Excel (version 2108). The results were summarised into frequencies, rates and proportions and are presented in tables and figures. We calculated the proportion of health facilities reporting on RUM in the DHIMS2. The transcribed information was assessed to identify common themes. The relevant transcribed data from the interview were aligned with the themes, and these findings were triangulated with quantitative results.

Ethical consideration

This evaluation was carried out as part of the routine operational assessments and public health surveillance response activities of the Bono Regional Health Directorate to monitor rational prescriptions in the region. Administrative approval was obtained from the Bono Regional Health Directorate. Informed consent was sought from each respondent before an interview. The anonymity of participants was ensured by the use of codes that had been generated for the identification of respondents.

Results

Demographic characteristics of prescribers and informants

A total of 4.4% (12/272) of all health facilities in the region reported on the rational use of medicine indicators in DHIMS2. Most, 63.2% (12/19) of hospitals in the region report on antibiotic prescription. The majority of the prescribers in the region were males, 70.7% (107/152) and doctors, 57.2% (87/152). Most of them had worked in the service for less than 5 years, 38.8% (59/152), and had been working in their current facilities for less than 5 years, 61.8% (94/152). A greater proportion of the prescribers, 55.3% (84/152), were located in Sunyani East. The doctor-to-patient ratio for 2022 was 1:24,185 based on regional health administrative records [12]. The region has 36 pharmacists working in the facilities.

We interviewed 14 key informants during this evaluation. The majority of the respondents were males, 71.4% (10/14), and pharmacists, 42.9% (6/14). Fifty per cent of the respondents (7/14) had worked for more than 10 years in the health care system, and 71.4% (10/14) of them had worked in their current facility for more than 5 years (Table 3). The age range of the participants was between 29 and 56 years, with a mean age of 41 years.

Percentage of encounters with an antibiotic prescribed

A total of 4,544 patient encounters were abstracted from DHIMS2, of which 43.9% (1934/4544) were prescribed antibiotics from 2017 to 2022. In all years, the proportion of patients who were prescribed antibiotics exceeded the minimum national target of 20%. The highest proportion of patients who were prescribed antibiotics, 55.1% (523/950), was seen in 2020 (Figure 2).

The majority of antibiotic prescriptions were from Sunyani Municipal Hospital, Sunyani Municipal Hospital, Dormaa West District Hospital, Dormaa East District Hospital, Sampa Government Hospital and Drobo St. Mary Hospital in 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022, respectively (Table 2).

Factors contributing to high antibiotic use in the Bono Region

The results from the interviews to determine the factors were grouped under the following seven themes.

Level of prescribing & Standard Treatment Guidelines (STG) not adhered to

Healthcare professionals reported that the prescription of antibiotics in some hospitals was performed by nurses who had not been properly trained on antibiotic prescription and dispensing, because of the absence or inadequate number of physician assistants (PA) and doctors at the post. Most of these prescriptions do not adhere to the standard treatment guidelines and other facility-based antimicrobial policies.

R1: “In my hospital, untrained nurses prescribe in the consulting room because we have few PAs, the nurses are not given any orientation before working in the consulting room. They do not prescribe as in the STG.”

R2: “Some prescribers, especially nurses, prescribe antibiotics for conditions that do not require antibiotics.”

R3: “Nonadherence to ‘in-house’ antimicrobial formulary has contributed to the rise in Antibiotic use.”

Inability to perform culture and sensitivity tests and prescribe antibiotics when not needed

Healthcare professionals mentioned that due to the inadequacy of laboratory facilities and equipment in some hospitals, prescribers are unable to carry out the standard confirmatory laboratory procedure (recommended culture and sensitivity testing) that will aid in the accurate prescription of antibiotics. This has led to the prescription of antibiotics in most conditions that may not require their prescription of antibiotics.

R4: “Due to the lack of culture and sensitivity lab at our facility, prescribers overuse antibiotics e.g., combining 2 or more broad-spectrum antibiotics for a condition which one antibiotic can take care of.”

R5: “Lack of an antimicrobial lab for doing culture and sensitivity tests for ascertaining the need to prescribe certain antibiotics.”

R7: “Generally, most conditions presented by our Out-Patient Department (OPD) clients are diagnosed as bacterial infections resulting in the use of antibiotics. The prescribers at one point felt that antibiotic use increased recovery time.”

Supply chain management inefficiencies

It was mentioned that to reduce the number of expired antibiotics, some facilities ensure prescribers prescribe antibiotics as a way of pushing out drugs that are near expiration. This contributes to the high level of prescription of antibiotics to clients in these facilities.

R1: “Sometimes, too, when antibiotics are near expiry, prescribers are urged to push them.”

Poor infection prevention and control in communities

It was mentioned that the high level of prescriptions given by healthcare professionals was sometimes due to the high level of bacterial infections in communities. It was reported that the conditions community members usually presented with were mostly Upper Respiratory Tract Infections (URTIs) due to the nature of the roads in the area. Additionally, the activities of commercial sex workers increase during the cashew season in the cashew-growing areas of the region, leading to an increase in sexually transmitted infections and urinary tract infections (UTIs). These infections require the use of antibiotics in their treatment, and hence a high level of prescription of antibiotics.

R2: “Our Community is a cashew-growing area. During the season, a lot of Female Sexual Workers from all corners of the country and even the neighbouring countries come here and practice their trade, resulting in a rise in UTIs.”

R10: “Due to the dusty nature of our community, URTI is very common. In fact, these two conditions were among the top 3 outpatient morbidities during our recent mid-year review.”

Lack of antibiotic stewardship in health facilities

It was reported that many facilities do not have antibiotic stewardship committees to oversee antibiotic prescriptions. Again, it was reported that there were no clear-cut documented facility policies on the use of antibiotics to guide prescribers in carrying out their duties.

R6: “There is no Antibiotic Stewardship committee in my facility.”

R11: “There is an absence of a clear-cut institutional policy on the use of antibiotics in my facility”.

Irregular dissemination of RUM reports and related issues

Healthcare professionals reported that the compiled results from the quarterly rational use of medicines carried out at most facilities were not disseminated to the main stakeholders. The survey data are collected and entered into the DHIMS 2, after which the data are not used for any other purpose. Hence, the facilities do not know their level of prescription of antibiotics to inform action.

R6: “In my facility, even though Quarterly RUM surveys are done, they are not regularly disseminated.”

The quality of data entered into the quarterly rational use of medicine report

Some healthcare professionals stated that some of the individuals tasked by the facilities to carry out the surveys are not given any proper training on the data collection tools, which affects the quality of the data they collect and the accuracy of the reported data.

R5: “There has been no training on how to fill the fields on the Quarterly Rational Use of Medicine Report.”

R8: “Instead of entering the raw figures generated during the survey, the pharmacist did some calculations, and we entered the calculated figures into the DHIMS instead. This led to us having that high percentage for antibiotic use.”

R9: “Our unit has not received any survey results from the pharmacy unit to be entered into the DHIMS2 for the period that we have no figures for our facility name.”

Discussion

Our study, which sought to determine antibiotic prescription rates in the Bono Region, revealed a persistent trend of high antibiotic use in health facilities. The proportion of patient encounters resulting in antibiotic prescriptions was consistently high throughout the study period, exceeding both the national target and the WHO recommended threshold. [4]. These high rates were not isolated to specific years or facilities but rather were consistently reported across multiple hospitals, indicating that irrational antibiotic prescription is widespread in the region. This aligns with global estimates suggesting that most of health facility prescriptions include antibiotics [2]. Such persistent overprescription contributes directly to the acceleration of AMR, reducing the effectiveness of first-line antibiotics and increasing the burden on health systems through prolonged illnesses and costlier treatments.

However, our findings also highlighted critical data gaps. Only few health facilities reported antibiotic use through DHIMS2, and all reporting facilities were hospitals. This indicates that lower-level health facilities, which form the majority of health service points, are largely unmonitored in terms of antibiotic use. Qualitative insights confirmed this gap, with key informants pointing to weak data management systems and a lack of training for those responsible for reporting. The exclusion of these facilities from monitoring undermines the broader effort to manage antimicrobial resistance, as they likely contribute significantly to irrational use. The lack of comprehensive surveillance limits the Ministry of Health’s ability to design targeted interventions, weakening Ghana’s capacity to respond to AMR threats at the national level.

A major contributing factor to this trend was the nonadherence to standard treatment guidelines (STGs). Qualitative interviews revealed that in many facilities, especially those lacking sufficient medical staff, untrained nurses were tasked with prescribing antibiotics, often without orientation or reference to the STGs. These frontline workers frequently prescribed antibiotics for conditions that do not warrant their use, exacerbating inappropriate prescribing practices. The WHO strongly recommends the use of clinical guidelines to improve rational antibiotic use and curb resistance [12]. However, without institutional structures like functional Antibiotic Stewardship Committees or clear in-house policies, as noted by our respondents, adherence remains low. This aligns with a 2019 study in sub-Saharan Africa, which found that while some legislation on antibiotic use exists, enforcement is weak [13]. When prescribers deviate from STGs, it not only increases the risk of treatment failure and AMR but also undermines trust in the health system, especially when patients experience side effects or poor outcomes.

The inadequacy of trained personnel, particularly doctors and physician assistants, was another key factor. Our data showed that only 36 pharmacists were working across the region’s facilities, with most prescribers being relatively young (under 5 years in service) and skewed towards urban municipalities such as Sunyani East. In many rural or under-resourced settings, nurses with limited training are used as substitute prescribers. This human resource gap, compounded by limited exposure to STGs, increases the risk of inappropriate prescribing. Qualitative respondents emphasized that diagnostic limitations also drive inappropriate prescriptions. Inadequate laboratory infrastructure, particularly for culture and sensitivity testing, often forces clinicians to rely solely on empirical judgment, leading to the frequent use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Similar findings were observed in Mozambique, where low diagnostic capacity was linked to poor antibiotic stewardship [13]. Inadequate diagnostic and human resource capacity increases reliance on empirical treatment, which may not only promote AMR but also misallocate limited healthcare resources, especially in rural and deprived areas.

Our findings also underscored inefficiencies in supply chain management systems as a driver of inappropriate antibiotic use. Facilities reportedly pressured prescribers to use near-expiry antibiotics to avoid wastage, even when not clinically necessary. This practice contributes to overprescribing and further undermines antibiotic stewardship. Although prior studies have linked poor supply chain practices to irrational medicine use, few have directly reported the pressure to use expiring stock as a specific factor [14,15]. These supply chain practices highlight the need to align pharmaceutical logistics with clinical priorities; failure to do so can turn economic decisions into clinical risks that compromise patient safety and contribute to antibiotic misuse.

Furthermore, community-level infection prevention and control (IPC) challenges were reported to influence prescription behaviour. Informants cited poor sanitation, dusty roads, and seasonal spikes in commercial sex work—particularly during the cashew harvesting season—as contributing to higher incidences of URTIs and STIs. These environmental and social factors increase the burden of bacterial infections, prompting more frequent prescriptions of antibiotics. Similar patterns have been documented in other studies linking weak IPC systems to higher infection rates and increased antibiotic use [16,17]. Without investments in community sanitation and public health education, the cycle of infection and overprescription will persist, undermining both health outcomes and national AMR containment strategies.

Limitations

The data that were used in the study were secondary data that did not afford us the chance to conduct more findings regarding the appropriateness of the antibiotics given to clients based on diagnoses. We therefore limited ourselves to findings that were available from the data obtained. The study identified some abnormally high figures in the data generated on the patient encounters with antibiotics. It is evident that some facilities enter wrong figures during data entry. The poor data quality can affect indicator outcomes, in this case, antibiotic use. Nevertheless, the data abstracted is enough to make conclusions on the rate of antibiotic prescription.

Recommendation for responsible use of antimicrobials

It is recommended that the Drugs and Therapeutic Committees institute antimicrobial stewardship subcommittees in all hospitals and ensure regular dissemination of RUM findings. Drug therapeutic committees through the antimicrobial stewardship committee should urgently train all prescribers especially nurse prescribers, on the rational use of antibiotics and the use of STGs. The Regional Human Resource Unit should ensure there is equitable distribution of doctors and other prescribers in the region to improve there are enough prescribers in all facilities. Facility Management should plan to expand the capacity of laboratories to conduct culture and sensitivity tests as well as other needed investigations and ensure that the prescribing and dispensing of antimicrobials are informed by laboratory results. There is a need for regional and facility medical stores to improve the efficiency of procuring antibiotics to prevent indiscriminate use of near-expiry antibiotics. Additionally, the health promotion units of facilities and district health administrations should conduct health education on infection prevention & control practices in high-infectious-risk communities, especially during peak periods. The regional drugs and therapeutics committee should conduct further studies into the appropriateness of antibiotic prescription based on diagnosis. There Should be constant validation of RUM data by the regional and district health information units, and silent facilities should be enforced to enter RUM Data in DHIMS.

Conclusion

Antibiotic prescription in health facilities in the Bono Region is high. Nonadherence to standard treatment guidelines, ineffective antibiotic stewardship in health facilities, inadequate numbers of doctors and physician assistants in the region, and laboratories in health facilities not well equipped to conduct culture and sensitivity tests are some key factors influencing antibiotic prescription in the Bono Region. There is a need to improve antimicrobial stewardship in health facilities to improve the prescription of antibiotics in health facilities.

What is already known about the topic

- Half of all medications, including antibiotics, are prescribed improperly globally

- Approximately half of patients reporting to health facilities are prescribed antibiotics in Africa

- Antibiotic resistance is estimated to be as high among patients presenting with bacterial diseases in hospitals In Ghana

What this study adds

- Nonadherence to standard treatment guidelines and ineffective antibiotic stewardship influence antibiotic prescription rates

- Improving antimicrobial stewardship in facilities could reduce the rate of antibiotic prescription

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Franklin Asiedu-Bekoe Director of Public Health, Ghana Health Service, Professor Ernest Kenu, Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana, Paul Henry Dsane-Aidoo, Abdul-Gafaru, Mohammed, Magdalene Akos Odikro Ghana Field Epidemiological and Laboratory Training Program and the Bono Regional Health Directorate and Collins Amankwaa Adu, Bono Regional Health Directorate.

Authors´ contributions

Conception and design; Eric Kofi Nyarko, Emmanuel Obeng-Hinneh, Stephen Kwame Korang, Prince Quarshie, Kofi Amo-Kodieh and Georgia Ghartey. Coordinating data collection; Eric Kofi Nyarko, Emmanuel Obeng-Hinneh, and Emmanuel George Bachan Data analysis; Eric Kofi Nyarko, Emmanuel Obeng-Hinneh, Georgia Ghartey, Prince Quarshie, Kofi Amo-Kodieh and Emmanuel George Bachan. Drafting of the paper; Eric Kofi Nyarko, Emmanuel Obeng-Hinneh, Emmanuel George Bachan, Georgia Ghartey, and Kofi Amo-Kodieh. Review of the manuscript critically for important intellectual content; Eric Kofi Nyarko, Emmanuel Obeng-Hinneh, Georgia Ghartey, Stephen Kwame Korang, Kofi Amo-Kodieh, Prince Quarshie, and Emmanuel George Bachan. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

| Variables | No. of respondents (n=152) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 45 | 29.6 |

| Male | 107 | 70.4 |

| Cadre of prescribers | ||

| Doctors | 87 | 57.2 |

| Physician Assistants | 65 | 42.8 |

| Number of years in service | ||

| Less than 5 years | 59 | 38.8 |

| 5 to 10 years | 38 | 25.0 |

| More than 10 years | 55 | 36.2 |

| Number of years in the current facility | ||

| Less than 5 years | 94 | 61.8 |

| 5 to 10 years | 50 | 32.9 |

| More than 10 years | 8 | 5.3 |

| Distribution of Prescribers | ||

| Banda | 2 | 1.3 |

| Berekum East | 2 | 1.3 |

| Berekum West | 3 | 2.0 |

| Dormaa East | 4 | 2.6 |

| Dormaa Municipal | 4 | 2.6 |

| Dormaa West | 5 | 3.3 |

| Jaman North | 10 | 6.6 |

| Jaman South | 7 | 4.6 |

| Sunyani East | 84 | 55.3 |

| Sunyani West | 13 | 8.6 |

| Tain | 12 | 7.9 |

| Wenchi | 6 | 3.2 |

| Facility Name | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bono Regional Hospital | 0 | 0 | 35 | 72.2 | 48.9 | 38.3 |

| Chiraa Government Hospital | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29.5 |

| Dormaa East District Hospital | 0 | 0 | 0 | 112.5 | 43.3 | 27.5 |

| Presbyterian Hospital, Dormaa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 60 |

| Dormaa West District Hospital | 0 | 0 | 77.7 | 30 | 36.7 | 39.2 |

| Drobo St Mary Hospital | 47.5 | 30 | 22.5 | 21.8 | 35 | 46.7 |

| Holy Family Hospital, Berekum | 0 | 0 | 24.4 | 26.7 | 63.3 | 26.3 |

| Methodist Hospital, Wenchi | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 43.3 | 30 |

| Sampa Government Hospital | 0 | 0 | 0 | 79.4 | 133.3 | 25 |

| Sunyani Municipal Hospital | 57.5 | 62.2 | 70 | 69.2 | 63.3 | 38.3 |

| Sunyani SDA Hospital | 0 | 20 | 36.7 | 31.7 | 38.2 | 28.3 |

| Tain District Hospital | 26.7 | 25.6 | 16.7 | 30 | 37.8 | 36.7 |

| Socio-demographic Characteristics | No. of Respondents | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 10 | 71.4 |

| Female | 4 | 28.6 |

| Cadre of Respondent | ||

| Pharmacist | 6 | 42.9 |

| Medical Officer | 5 | 35.7 |

| Health Information Officer | 3 | 21.4 |

| Number of Years in Service | ||

| Less than 5 years | 2 | 14.3 |

| 5 to 10 years | 5 | 35.7 |

| More than 10 years | 7 | 50.0 |

| Number of Years in the Current Facility | ||

| Less than 5 years | 4 | 28.6 |

| 5 to 10 years | 5 | 35.7 |

| More than 10 years | 5 | 35.7 |

| Number of Respondents from Facilities | ||

| More than 1 respondent | 2 | 16.7 |

| Only 1 respondent | 10 | 83.3 |

| Number of Respondents from District | ||

| More than 1 respondent | 1 | 8.3 |

| Only 1 respondent | 9 | 75.0 |

| No respondent | 2 | 16.7 |

References

- Sami R, Salehi K, Sadegh R, Solgi H, Atashi V. Barriers to rational antibiotic prescription in Iran: a descriptive qualitative study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control [Internet]. 2022 Aug 29 [cited 2026 Jan 22];11(1):109. Available from: https://aricjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13756-022-01151-6 doi:10.1186/s13756-022-01151-6.

- D’Arcy N, Ashiru-Oredope D, Olaoye O, Afriyie D, Akello Z, Ankrah D, Asima DM, Banda DC, Barrett S, Brandish C, Brayson J, Benedict P, Dodoo CC, Garraghan F, Hoyelah J, Jani Y, Kitutu FE, Kizito IM, Labi AK, Mirfenderesky M, Murdan S, Murray C, Obeng-Nkrumah N, Olum WJ, Opintan JA, Panford-Quainoo E, Pauwels I, Sefah I, Sneddon J, St. Clair Jones A, Versporten A. Antibiotic prescribing patterns in Ghana, Uganda, Zambia and Tanzania hospitals: results from the global point prevalence survey (G-PPS) on antimicrobial use and stewardship interventions implemented. Antibiotics (Basel) [Internet]. 2021 Sep 17 [cited 2026 Jan 22];10(9):1122. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2079-6382/10/9/1122 doi:10.3390/antibiotics10091122.

- Wendie TF, Ahmed A, Mohammed SA. Drug use pattern using WHO core drug use indicators in public health centers of Dessie, North-East Ethiopia. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak [Internet]. 2021 Jun 25 [cited 2026 Jan 22];21(1):197. Available from: https://bmcmedinformdecismak.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12911-021-01530-w doi:10.1186/s12911-021-01530-w.

- World Health Organization. Promoting rational use of medicines: core components [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2002 Sep [cited 2026 Jan 22]. 6 p. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/67438/WHO_EDM_2002.3.pdf.

- Ministry of Health (Ghana). Quarterly Rational Use of Medicine Indicators [Internet]. Accra (Ghana): Ministry of Health; 2023 [cited 2026 Jan 22]. Available from: https://chimgh.org/.

- Hayat S. Nanoantibiotics: Future nanotechnologies to combat antibiotic resistance. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) [Internet]. 2018 Mar 1 [cited 2026 Jan 22];10(2):352-74. Available from: https://imrpress.com/journal/FBE/10/2/10.2741/E827 doi:10.2741/e827.

- Murray CJL, Ikuta KS, Sharara F, Swetschinski L, Robles Aguilar G, Gray A, Han C, Bisignano C, Rao P, Wool E, Johnson SC, Browne AJ, Chipeta MG, Fell F, Hackett S, Haines-Woodhouse G, Kashef Hamadani BH, Kumaran EAP, McManigal B, Achalapong S, Agarwal R, Akech S, Albertson S, Amuasi J, Andrews J, Aravkin A, Ashley E, Babin FX, Bailey F, Baker S, Basnyat B, Bekker A, Bender R, Berkley JA, Bethou A, Bielicki J, Boonkasidecha S, Bukosia J, Carvalheiro C, Castañeda-Orjuela C, Chansamouth V, Chaurasia S, Chiurchiù S, Chowdhury F, Clotaire Donatien R, Cook AJ, Cooper B, Cressey TR, Criollo-Mora E, Cunningham M, Darboe S, Day NPJ, De Luca M, Dokova K, Dramowski A, Dunachie SJ, Duong Bich T, Eckmanns T, Eibach D, Emami A, Feasey N, Fisher-Pearson N, Forrest K, Garcia C, Garrett D, Gastmeier P, Giref AZ, Greer RC, Gupta V, Haller S, Haselbeck A, Hay SI, Holm M, Hopkins S, Hsia Y, Iregbu KC, Jacobs J, Jarovsky D, Javanmardi F, Jenney AWJ, Khorana M, Khusuwan S, Kissoon N, Kobeissi E, Kostyanev T, Krapp F, Krumkamp R, Kumar A, Kyu HH, Lim C, Lim K, Limmathurotsakul D, Loftus MJ, Lunn M, Ma J, Manoharan A, Marks F, May J, Mayxay M, Mturi N, Munera-Huertas T, Musicha P, Musila LA, Mussi-Pinhata MM, Naidu RN, Nakamura T, Nanavati R, Nangia S, Newton P, Ngoun C, Novotney A, Nwakanma D, Obiero CW, Ochoa TJ, Olivas-Martinez A, Olliaro P, Ooko E, Ortiz-Brizuela E, Ounchanum P, Pak GD, Paredes JL, Peleg AY, Perrone C, Phe T, Phommasone K, Plakkal N, Ponce-de-Leon A, Raad M, Ramdin T, Rattanavong S, Riddell A, Roberts T, Robotham JV, Roca A, Rosenthal VD, Rudd KE, Russell N, Sader HS, Saengchan W, Schnall J, Scott JAG, Seekaew S, Sharland M, Shivamallappa M, Sifuentes-Osornio J, Simpson AJ, Steenkeste N, Stewardson AJ, Stoeva T, Tasak N, Thaiprakong A, Thwaites G, Tigoi C, Turner C, Turner P, van Doorn HR, Velaphi S, Vongpradith A, Vongsouvath M, Vu H, Walsh T, Walson JL, Waner S, Wangrangsimakul T, Wannapinij P, Wozniak T, Young Sharma TEMW, Yu KC, Zheng P, Sartorius B, Lopez AD, Stergachis A, Moore C, Dolecek C, Naghavi M. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet [Internet]. 2022 Feb 12 [cited 2026 Jan 22];399(10325):629-55. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673621027240.

- Jaka H, Rhee JA, Östlundh L, Smart L, Peck R, Mueller A, Kasang C, Mshana SE. The magnitude of antibiotic resistance to Helicobacter pylori in Africa and identified mutations which confer resistance to antibiotics: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2018 Apr 24 [cited 2026 Jan 22];18(1):193. Available from: https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-018-3099-4 doi:10.1186/s12879-018-3099-4.

- Donkor E, Newman M. Resistance to antimicrobial drugs in Ghana. Infect Drug Resist [Internet]. 2011 Dec 21 [cited 2026 Jan 22];4:215. Available from: http://www.dovepress.com/resistance-to-antimicrobial-drugs-in-ghana-peer-reviewed-article-IDR doi:10.2147/idr.s21769.

- Ministry of Health (Ghana). Ghana National Medicine Policy 3rd Edition [Internet]. Accra (Ghana): Ministry of Health; 2017 [cited 2026 Jan 22]. 112 p. Available from: https://www.ghndp.org.

- Afeti KP. Rational use of medicines: What the public must know [Internet]. Graphic Online; 2022 Jun 1 [cited 2026 Jan 22]. [about 3 screens]. Available from: https://www.graphic.com.gh/news/health/rational-use-of-medicines-what-the-public-must-know.html.

- Ghana Health Service. Bono Region [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2026 Jan 22]. [about 2 screens]. Available from: https://ghs.gov.gh/regions/bono-region.

- Mate I, Come CE, Gonçalves MP, Cliff J, Gudo ES. Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding antibiotic use in Maputo City, Mozambique. PLoS One [Internet]. 2019 Aug 22 [cited 2026 Jan 22];14(8):e0221452. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221452 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0221452.

- Kashiouris MG, Zemore Z, Kimball Z, Stefanou C, Fowler AA, Fisher B, De Wit M, Pedram S, Sessler CN. Supply chain delays in antimicrobial administration after the initial clinician order and mortality in patients with sepsis. Crit Care Med [Internet]. 2019 Oct [cited 2026 Jan 22];47(10):1388-95. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/10.1097/CCM.0000000000003921 doi:10.1097/ccm.0000000000003921.

- Kamere N, Rutter V, Munkombwe D, Atieno Aywak D, Prosper Muro E, Kaminyoghe F, Rajab K, Oluku Lawal M, Muriithi N, Kusu N, Karimu O, Hughric Adekule Barlatt S, Nambatya W, Ashiru-Oredope D. Supply-chain factors and antimicrobial stewardship. Bull World Health Organ [Internet]. 2023 Jun 1 [cited 2026 Jan 22];101(6):403-11. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10225941/pdf/BLT.22.288650.pdf doi:10.2471/blt.22.288650.

- Adedeji WA. The treasure called antibiotics. Ann Ib Postgrad Med [Internet]. 2016 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 22];14(2):56-7. PMID: 28337088.

- Larson E. Community factors in the development of antibiotic resistance. Annu Rev Public Health [Internet]. 2007 Apr 1 [cited 2026 Jan 22];28(1):435-47. Available from: https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144020 doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144020.