Review | Open Access | Volume 9 (1): Article 16 | Published: 23 Jan 2026

Antimicrobial resistance at the human-animal-environment interface: Implications for global health and food security

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Figures

Keywords

- Antimicrobial resistance

- One Health

- Global health

- Food security

- Environmental contamination

Maduabuchukwu Innocent Nkollo1,&, Rosemary Nkollo-Ngwuede2, Eseosa Irenegbe Oronsaye-Oseghale3, Osamudiamen McHillary Ogiemudia4, Martha Onarerhime Emolade5, Israel Ofejiro Efejene6

1Department of Optometry, College of Medical and Health Sciences, Novena University, Ogume, P.M.B. 002, Kwale, Delta State, Nigeria, 2Department of Agronomy and Ecological Management, Faculty of Agriculture, Enugu State University of Science and Technology, Agbani, Enugu State, Nigeria, 3Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Benin, P.M.B. 1154, Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria, 4Department of Environmental and Public Health Optometry, Faculty of Optometry, University of Benin, P.M.B. 1154, Benin-City, Edo State, Nigeria, 5Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Science, Southern Delta University, P.M.B. 5, Ozoro, Delta State, Nigeria, 6Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, Southern Delta University, P.M.B. 5, Ozoro, Delta State, Nigeria

&Corresponding author: Maduabuchukwu Innocent Nkollo, Department of Optometry, College of Medical and Health Sciences, Novena University, Ogume, P.M.B. 002, Kwale, Delta State, Nigeria. Email: nkolloinnocent@gmail.com ORCID: https://orcid.org//0009-0005-0428-0059.

Received: 28 Aug 2025, Accepted: 20 Jan 2026, Published: 23 Jan 2026

Domain: One Health, Antimicrobial Resistance

Keywords: Antimicrobial resistance, One Health, global health, food security, environmental contamination

©Maduabuchukwu Innocent Nkollo et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Maduabuchukwu Innocent Nkollo et al., Antimicrobial resistance at the human-animal-environment interface: Implications for global health and food security. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2026; 9(1):16. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00177

Abstract

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) undermines the efficacy of essential medicines and is amplified at the One Health interface, where human, animal, and environmental systems interact. Key drivers include antibiotic misuse, inadequate infection control, and environmental contamination. We assessed AMR transmission dynamics across the human–animal–environment interface and evaluated implications for global health and food security. This narrative review of peer-reviewed studies, policy documents, and global surveillance data was undertaken, incorporating case studies and best practices from international, regional, and national initiatives.

Antimicrobial use in livestock, human healthcare, and environmental contamination from pharmaceutical and agricultural waste are major contributors to AMR. Resistant pathogens spread through direct contact, food supply chains, and water systems. Impacts include increased morbidity and mortality, restricted treatment options, reduced agricultural productivity, and trade barriers. Gaps persist in surveillance, regulation, stewardship, and public engagement.

AMR at the One Health interface demands coordinated, multisectoral action. Enhanced surveillance, stricter antimicrobial regulation, research investment, and awareness campaigns are essential to safeguard health and food security.

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has emerged as one of the most critical threats to global health, food security, and sustainable development [1]. The rise of resistant pathogens undermines decades of medical progress, rendering once-effective treatments for infectious diseases increasingly powerless [2]. While much attention has been paid to human medicine, AMR is a complex, multifaceted issue that extends beyond hospitals and clinics. It thrives at the human-animal-environment interface, where interconnections between human health, veterinary practices, agriculture, and environmental systems fuel the emergence and spread of resistant organisms [3].

The overuse and misuse of antimicrobial agents in humans, livestock, aquaculture, and crop production — coupled with poor sanitation, inadequate waste management, and global trade — facilitate the transfer of resistant bacteria, genes, and residues across species and borders [4]. In animals, antibiotics are frequently used not only to treat infections but also as growth promoters and preventive measures, particularly in intensive farming systems. This contributes significantly to the development of resistant strains that can be transmitted to humans through direct contact, food consumption, or environmental contamination [5].

The consequences of AMR are far-reaching. Clinically, it leads to prolonged illness, higher mortality rates, and increased healthcare costs [6]. In agriculture, it threatens food production and animal health, risking economic loss and reduced food availability [7]. Environmentally, resistant bacteria and residues persist in soil, water, and air, creating reservoirs that perpetuate the resistance cycle [8].

Understanding and combating AMR therefore requires a One Health approach—a collaborative, multisectoral strategy that recognises the interdependence of human, animal, and environmental health [6,7,8]. This paper explores the dynamics of drug and antimicrobial resistance at this interface, examining its implications for global health, food security, and sustainable development, and emphasizing the urgent need for coordinated action and policy interventions at national and international levels.

Methods

This narrative review synthesises current knowledge on antibiotic resistance (AR) across the human-animal-environment interface, following a thematic and integrative approach to literature selection, analysis, and presentation. A purposive literature search was conducted using electronic databases including PubMed, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, and Web of Science. The search included articles published in English between January 2010 and June 2025, with additional reference to earlier foundational studies where relevant. Keywords used in various combinations included: “antibiotic resistance,” “antimicrobial resistance,” “One Health,” “human-animal-environment interface,” “zoonotic transmission,” “veterinary antibiotics,” “environmental contamination,” and “resistant pathogens.” Grey literature and official reports from organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were also reviewed to provide comprehensive and up-to-date information.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

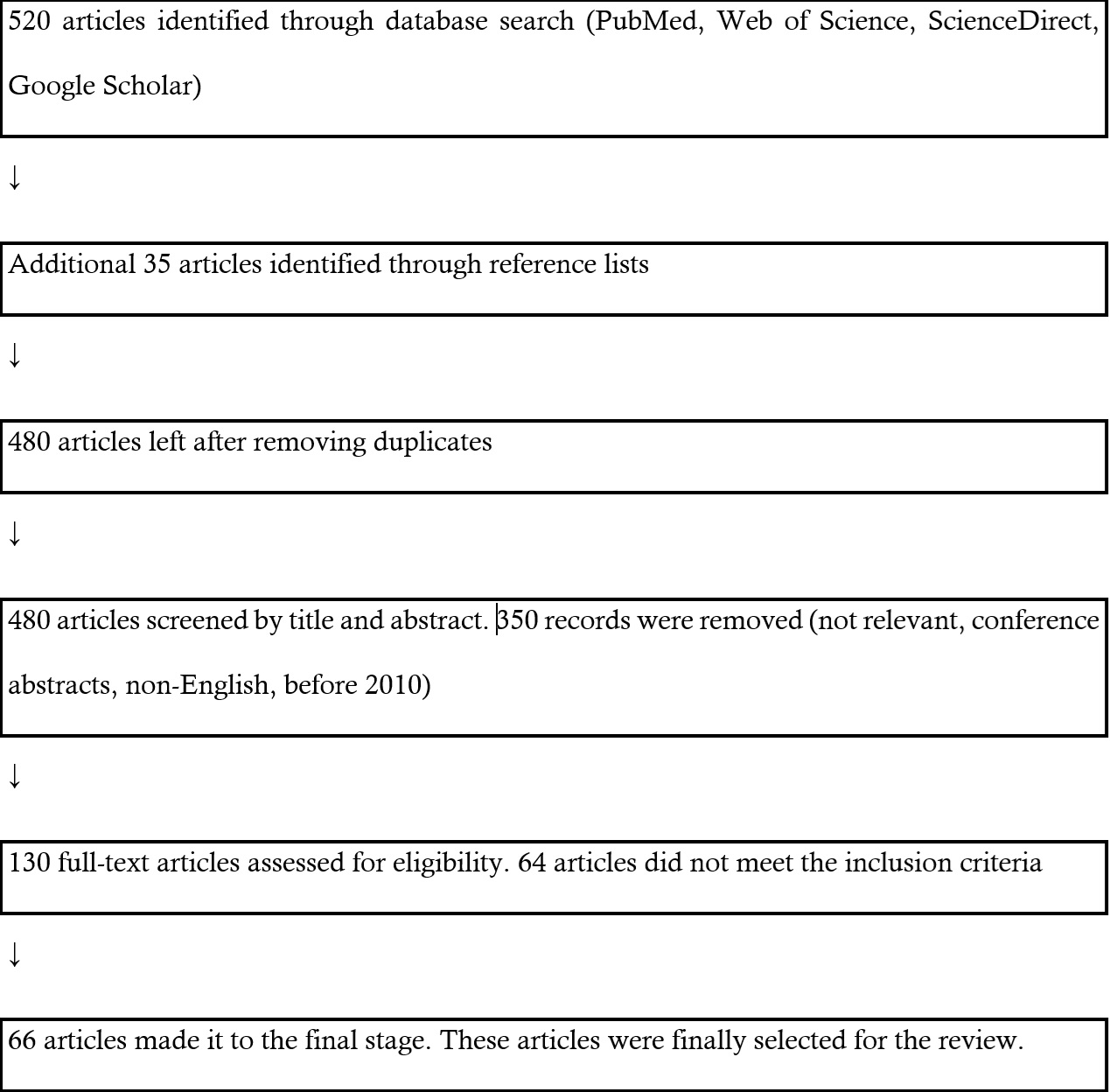

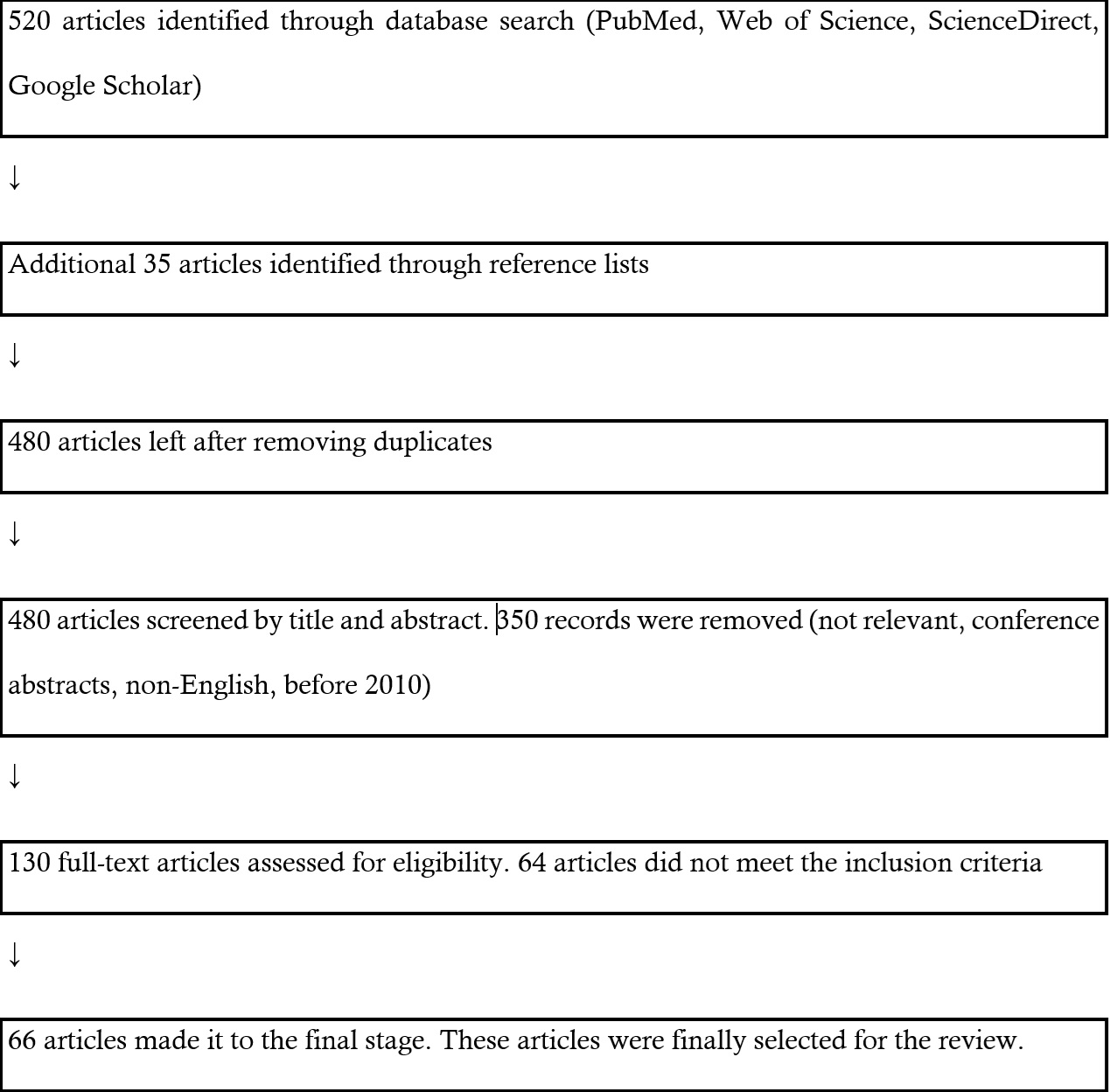

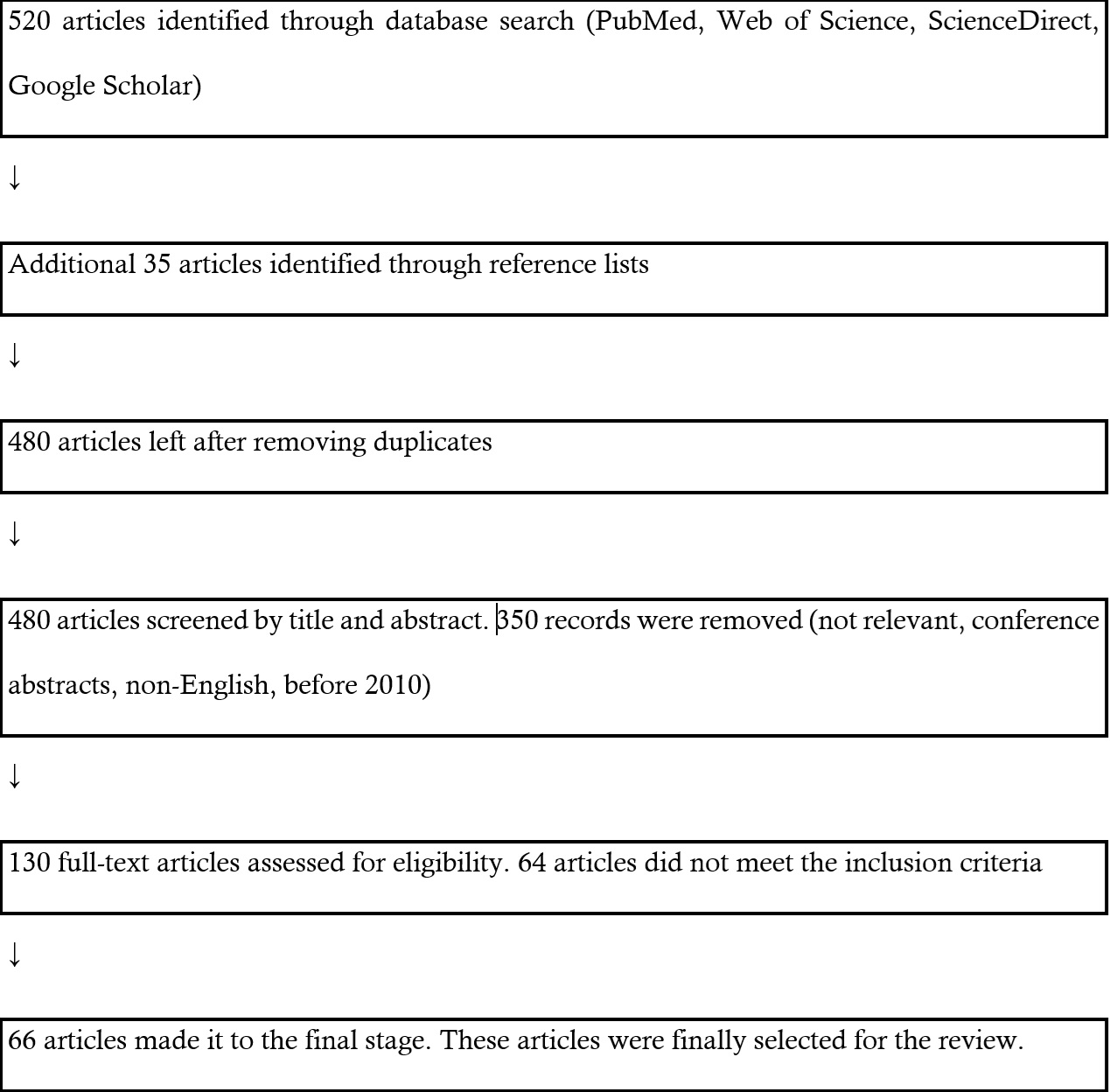

Articles were included based on relevance to the One Health framework and the review’s focus on cross-sectoral AR transmission. Eligible studies addressed at least one of the following: AR in humans, animals, or the environment; evidence of interface transmission; or strategies for monitoring and mitigation. Clinical studies not related to the interface or lacking contextual relevance were excluded. This is illustrated in the flowchart (Figure 1).

Data extraction and thematic organization

Selected materials were reviewed and categorised under thematic areas, including: Drivers and emergence of resistance in humans, animals, and the environment, transmission dynamics at the interface, surveillance systems and global response frameworks, impact on public health, food systems, and ecological stability. Proposed One Health-based solutions and policy recommendations. Due to the narrative nature of this review, no formal quality assessment or meta-analysis was performed. However, care was taken to ensure diversity of sources, scientific rigour, and relevance to the topic across different geographical contexts.

Data management and analysis

Data were synthesised narratively across the One Health interface. Studies were grouped into the three domains of human, animal, and environmental health. Within each domain, findings were coded into themes such as prevalence of resistant bacteria, antimicrobial usage patterns, resistance mechanisms, and transmission pathways. These themes were then compared and integrated across domains to identify overlaps, differences, and potential linkages, thereby providing a holistic understanding of antibiotic resistance within the One Health framework.”

Current status of knowledge

Drug resistance

Drug resistance describes a situation where a medication—such as an antimicrobial, anticancer, or antineoplastic agent—becomes less effective in treating a disease or condition [9]. This loss of effectiveness happens when microorganisms or cancer cells adapt and become resistant to the drug, whether before treatment begins, during its course, or afterwards, resulting in prolonged or more difficult-to-treat illnesses [10]. The five main types of drug resistance are: intrinsic resistance, acquired (extrinsic) resistance, multidrug resistance (MDR), extensive drug resistance (XDR), and pan-drug resistance (PDR) [11].

Intrinsic resistance refers to the innate ability of a microorganism to withstand the effects of a drug. For instance, certain bacteria naturally have cell walls that prevent antibiotics from penetrating and taking effect. Extrinsic resistance occurs when a microorganism undergoes a change—such as a genetic mutation or acquiring resistance genes—that causes a drug, which was once effective, to no longer work against it. This is the most commonly understood form of drug resistance [12].

Multidrug resistance (MDR) describes a condition where a microorganism is resistant to at least one drug in three or more different classes of antimicrobial agents [13]. These drug classes are defined based on how they work and the types of microbes they target. MDR is particularly concerning in bacteria that are resistant to several antibiotics, but the term also applies to viruses, fungi, and parasites that resist multiple types of drugs. Extensively drug-resistant (XDR) organisms are those that remain susceptible to only one or two classes of antimicrobial agents, having developed resistance to all others. Pandrug-resistant (PDR) organisms are resistant to all known antimicrobial agents across every drug category [13,14].

Antimicrobial resistance

Antimicrobial agents, including antibiotics, antivirals, and antifungals, are used to suppress or eliminate the activity of bacteria, viruses, and fungi responsible for infectious diseases. However, within microbial populations, some organisms may naturally carry genetic mutations that provide resistance to these drugs [15]. When treatment is administered, it often eliminates the non-resistant microbes, while those with resistance survive and multiply, leading to the development of drug-resistant strains. This phenomenon is more likely to occur when antimicrobial drugs are misused—for example, when a patient fails to complete a prescribed course or when drugs are incorrectly prescribed, such as using antibiotics to treat viral infections [16]. Additionally, resistance traits can be transferred between different microbial species that inhabit the same host, further contributing to the spread of resistance [17]. The excessive use of antibiotics in both human medicine and livestock production has accelerated the emergence of resistant pathogens, making certain infections increasingly difficult to treat [10]. These are referred to as drug-resistant infections, which pose significant treatment challenges and, in some cases, may be untreatable. The primary mechanisms through which microorganisms develop resistance include enzymatic inactivation or modification of the drug, reduced drug accumulation through impaired uptake or increased efflux, alterations in the drug’s target site, overproduction of the target, bypassing the targeted metabolic pathway, and mimicking the drug target to avoid its effects [4].

Drug modification or inactivation

Certain resistance genes produce enzymes that either chemically modify or degrade antimicrobial agents, leading to their inactivation. This is a widespread mechanism by which many microbes become resistant to various drugs. For example, aminoglycoside resistance may result from the enzymatic attachment of chemical groups to the drug, which disrupts its ability to bind to bacterial targets. In β-lactam antibiotics, resistance often involves the enzymatic breakdown of the β-lactam ring, specifically by cleaving the β-lactam bond. This process, carried out by β-lactamase enzymes, is the primary method by which bacteria resist β-lactams. Rifampin can be inactivated through enzymatic processes like glycosylation, phosphorylation, or ADP-ribosylation. Additionally, drugs such as macrolides and lincosamides can also be rendered ineffective through similar enzymatic modifications or inactivation [18].

Prevention of cellular uptake or efflux

Microbes can resist antimicrobial agents by preventing their accumulation within the cell, thereby stopping the drug from reaching its target site. This method of resistance is often observed in gram-negative bacteria and may result from modifications in the outer membrane’s lipid structure, alterations in porin channel function, or reduced expression of porin proteins. For example, Pseudomonas aeruginosa commonly becomes resistant to carbapenems by decreasing the production of the OprD porin, which normally allows these antibiotics to pass through the outer membrane. In addition, many gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria possess efflux pumps that actively expel antimicrobial agents from the cell, preventing the drug from reaching an effective concentration. These pumps can contribute to resistance against several antibiotics, including β-lactams, tetracyclines, and fluoroquinolones, and are often capable of removing multiple drug types [19].

Target modification

Antimicrobial drugs target specific cellular structures, but when these targets undergo structural changes, the drugs may no longer be effective. Such changes often result from spontaneous mutations in the genes encoding the drug targets, giving bacteria an evolutionary edge by enabling drug resistance. A well-known example is the alteration of penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), where mutations at their active sites reduce the binding of β-lactam antibiotics, leading to resistance across this drug class [6]. This is especially common in Streptococcus pneumoniae, which modifies its PBPs through genetic changes. On the other hand, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) acquires resistance differently—by obtaining a new PBP with low affinity for β-lactams, rather than modifying existing ones [7]. This new protein grants resistance to nearly all β-lactam antibiotics, except certain newer fifth-generation cephalosporins specifically designed to combat MRSA. Other resistance examples involving target modifications include changes in ribosomal subunits (resistance to macrolides, tetracyclines, and aminoglycosides), alterations in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) structure (resistance to polymyxins), mutations in RNA polymerase (resistance to rifampin), changes in DNA gyrase (resistance to fluoroquinolones), modified metabolic enzymes (resistance to sulfonamides, sulfones, and trimethoprim), and alterations in peptidoglycan peptide chains (resistance to glycopeptides) [19].

Target overproduction or enzymatic bypass

When an antimicrobial drug acts as an antimetabolite by inhibiting a specific enzyme, microbes can still develop resistance through several mechanisms. One method involves the microorganism producing an excess of the target enzyme, ensuring that enough unbound enzyme remains active to sustain the necessary biochemical process. Another strategy includes the development of an alternative metabolic pathway that bypasses the need for the inhibited enzyme altogether. These resistance approaches are commonly observed with sulfonamide use. In the case of Staphylococcus aureus, vancomycin resistance has been associated with reduced cross-linking of peptide chains in the cell wall, resulting in more binding sites for the antibiotic in the outer cell wall. This enhanced binding creates a barrier that hinders the drug from reaching its actual site of action, thereby obstructing the inhibition of cell wall synthesis [20].

Target mimicry

A newly identified resistance mechanism known as target mimicry involves the synthesis of proteins that attach to antimicrobial drugs, effectively trapping them and preventing interaction with their intended targets [18,20]. For instance, Mycobacterium tuberculosis produces a protein composed of repeated pentapeptide sequences that structurally resemble DNA. This mimic protein binds to fluoroquinolones, blocking their access to DNA and thereby conferring resistance to the antibiotic. Similarly, proteins that imitate the A-site of the bacterial ribosome have been implicated in resistance to aminoglycosides [20].

MDR microbes and cross-resistance

From a clinical standpoint, one of the most pressing concerns is the rise of MDR microorganisms and cross-resistance. MDR organisms, often referred to as “superbugs,” possess one or more resistance mechanisms that render them impervious to several classes of antimicrobial agents. In cases of cross-resistance, a single mechanism enables resistance to multiple drugs [19]. A common example is the use of efflux pumps by microbes to actively expel a variety of antimicrobial agents, thereby conferring broad-spectrum resistance through a single pathway. In recent years, the emergence of clinically significant superbugs has become increasingly alarming. According to the CDC, these pathogens are responsible for over 2 million infections and at least 23,000 deaths annually in the United States alone [3]. Many of these superbugs are grouped under the acronym ESKAPE, which stands for Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species [3]. The term is symbolic as these organisms often “escape” the effects of conventional antimicrobial treatments. Consequently, ESKAPE pathogens are associated with challenging-to-treat infections and are a leading cause of hospital-acquired infections.

Recent hospital-based studies across Nigeria have revealed the alarming spread of multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens. A 2025 study in Osogbo identified K. pneumoniae isolates resistant to third-generation cephalosporins and carbapenems, largely due to lapses in infection prevention and control (IPC) and irrational prescribing patterns [21]. In Lagos, a molecular study reported carbapenem-resistant Enterococcus spp. Not only in human patients but also in environmental and animal samples, highlighting the permeability of sectoral boundaries in resistance transmission [22].

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

Methicillin, a type of semisynthetic penicillin, was created to avoid being broken down by β-lactamase enzymes. However, resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus began to emerge shortly after its introduction. These methicillin-resistant strains developed resistance by acquiring a new penicillin-binding protein (PBP) with low affinity for β-lactams, making them resistant to all antibiotics in this group. MRSA has since become a widespread opportunistic pathogen, commonly linked to skin and wound infections, as well as more serious illnesses like pneumonia and bloodstream infections. Initially found in hospitals (hospital-acquired MRSA or HA-MRSA), MRSA has also spread into the general population (community-associated MRSA or CA-MRSA). About one-third of people naturally carry S. aureus in their nasal passages without symptoms, and roughly 6% of these carry methicillin-resistant strains [23].

Clavulanic acid: A small assistant to penicillin

When penicillin was introduced in the early 1940s and began to be produced on a large scale, it was hailed as a miracle drug capable of curing many infectious diseases. However, by 1945, cases of penicillin-resistant infections had already been observed, and resistance quickly spread [24]. Today, over 90% of Staphylococcus aureus strains found in clinical settings are resistant to penicillin [25].

While creating new antimicrobial drugs remains one way to tackle resistance, researchers have also pursued alternative strategies—such as designing compounds that block resistance mechanisms. One of the earliest examples of this approach is the development of clavulanic acid. This compound, produced by the bacterium Streptomyces clavuligerus, has a β-lactam ring like penicillin but lacks antibacterial activity on its own. Instead, clavulanic acid binds irreversibly to the active site of β-lactamase enzymes, thereby preventing these enzymes from breaking down penicillin when both are given together [26].

Clavulanic acid was first developed in the 1970s and was commercially released in the 1980s in combination with amoxicillin under the brand name Augmentin [27] As expected, bacteria eventually developed resistance to this combination therapy as well. Resistance typically arises either through increased production of β-lactamase to overpower clavulanic acid, mutations that render β-lactamase resistant to clavulanic acid inhibition, or acquisition of new β-lactamase enzymes unaffected by the inhibitor [28]. Despite these challenges, clavulanic acid and similar β-lactamase inhibitors like sulbactam and tazobactam remain key tools in combating antibiotic resistance by targeting the enzymes responsible for drug inactivation.

Vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE) and Staphylococcus aureus (SA)

Vancomycin is an antibiotic that is effective only against gram-positive bacteria. It is often used to treat serious infections such as wound infections, sepsis, endocarditis, and meningitis, especially when these conditions are caused by bacteria resistant to other antibiotics. As one of the last-resort drugs, vancomycin is particularly important for treating resistant infections like [29]. However, its widespread use during the 1970s and 1980s contributed to the emergence of vancomycin-resistant organisms, including VRE, vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA), and vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA). VRE develop resistance through a mechanism known as target modification [6], where changes in the peptide portion of peptidoglycan prevent vancomycin from binding effectively. These resistant strains commonly spread in healthcare environments via contact with contaminated surfaces, medical devices, or healthcare workers [6,7].

VISA and VRSA differ in both their resistance levels and underlying mechanisms. VISA strains have intermediate resistance, with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) between 4–8 μgml/ [29]. This resistance is due to reduced crosslinking in the bacterial cell wall, which increases the number of vancomycin binding sites and traps the drug in the outer layers of the cell wall. In contrast, VRSA strains demonstrate higher resistance (MIC ≥16 μg/mL), typically resulting from the horizontal transfer of resistance genes from VRE during coinfection with MRSA and VRE [30]. Prompt detection of these resistant strains is crucial to prevent their spread in healthcare settings. Oxazolidinone antibiotics, such as linezolid, are effective alternatives for treating infections caused by vancomycin-resistant bacteria and MRSA.

Extended-spectrum β-lactamase–producing gram-negative pathogens

Gram-negative bacteria that produce extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) exhibit resistance to a broad range of β-lactam antibiotics, including penicillins, cephalosporins, monobactams, and β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, though carbapenems usually remain effective. A serious issue is that ESBL genes are typically located on mobile plasmids, which often carry additional resistance genes to other antibiotic classes like fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and tetracyclines [31]. These plasmids can be easily shared between bacteria through horizontal gene transfer. ESBL-producing bacteria may be part of the normal gut flora in some people but are also key contributors to opportunistic infections in hospital settings, where they can spread to other patients.

Carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria

The emergence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) and resistance among other gram-negative bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia poses a serious challenge in healthcare [32]. These bacteria become resistant to carbapenems through several strategies, including producing carbapenemases—enzymes capable of breaking down nearly all β-lactam antibiotics—actively pumping the drug out of the cell, or blocking its entry by altering porin channels. As with extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing strains, these resistant gram-negative organisms are frequently resistant to multiple antibiotic classes, and some strains have even developed resistance to all known antibiotics (pan-resistance). Such infections are most commonly acquired in clinical environments, often due to exposure to contaminated equipment, contact with infected individuals, or following surgical interventions [33].

MDR Mycobacterium tuberculosis

The rise of MDR Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MDR-TB) and extensively drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis (XDR-TB) poses a serious global health threat [4,8,9]. MDR-TB is characterized by resistance to both rifampin and isoniazid,[33] the primary drugs used in standard TB treatment. XDR-TB, on the other hand, shows additional resistance to any fluoroquinolone and at least one of the second-line injectable drugs—amikacin, kanamycin, or capreomycin—leaving patients with very limited treatment options [34]. These resistant strains are especially dangerous for individuals with weakened immune systems, such as those living with HIV. Resistance typically arises due to improper or incomplete use of tuberculosis medications, which promotes the selection of drug-resistant strains.

Drivers of AMR

AMR is driven by a complex interplay of microbial, environmental, pharmaceutical, patient-related, and healthcare-related factors. These drivers act synergistically to facilitate the emergence, persistence, and spread of resistant pathogens. Environmental factors, drug-related factors, patient-related factors and health care provider-related factors are broadly the contributors to AMR [34].

Environmental factors

Factors contributing to the spread of AMR are multifaceted and interconnected. High population density and overcrowded living conditions, especially in urban slums and refugee settlements, create environments where infectious diseases can spread rapidly due to close human contact and limited access to healthcare. The ease and frequency of global travel further exacerbate this issue by enabling pathogens, including resistant strains, to cross borders within hours, undermining local containment efforts [35]. Poor sanitation and hygiene practices—such as inadequate access to clean water, improper waste disposal, and insufficient hand hygiene—significantly increase the risk of infection and facilitate the transmission of resistant microorganisms in communities and healthcare settings.

Additionally, weak or poorly implemented infection prevention and control (IPC) programs in hospitals and clinics, including inadequate sterilization procedures, lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), and overcrowded wards, contribute to the nosocomial spread of resistant pathogens [36]. Furthermore, the indiscriminate and excessive use of antimicrobials in agriculture and animal husbandry, often as growth promoters or preventive measures in livestock, aquaculture, and poultry, creates selective pressure that accelerates the emergence of resistant strains. These resistant bacteria can then be transmitted to humans through the food chain, direct contact with animals, or environmental contamination, further complicating efforts to manage and treat infections.

Drug-related factors

The availability and circulation of counterfeit and substandard drugs, along with the unregulated over-the-counter (OTC) sale of antimicrobials without prescriptions, pose a serious threat to global public health and significantly contribute to the growing problem of AMR [34]. Counterfeit drugs may contain incorrect doses, harmful additives, or no active ingredient at all, while substandard drugs are often improperly manufactured or stored, leading to degraded efficacy. When patients consume these poor-quality medications, the result is often sub-therapeutic drug levels in the body—insufficient to effectively eliminate pathogens but adequate to apply selective pressure that encourages the survival and proliferation of resistant strains [35].

Furthermore, the ease of access to antibiotics without proper medical guidance promotes inappropriate usage, such as using antibiotics for viral infections, incorrect dosing, and premature discontinuation of therapy. These behaviors further enhance the risk of resistance development. In many low- and middle-income countries, weak regulatory frameworks, lack of enforcement, and informal drug markets exacerbate the problem. Tackling this issue requires coordinated efforts to strengthen pharmaceutical regulations, enhance drug surveillance systems, and educate the public on the dangers of counterfeit medications and unsupervised antibiotic use [36].

Patient-related factors

Poor adherence to prescribed treatments, poverty, lack of education, and widespread self-medication are major drivers of AMR. Many patients fail to complete their full course of antibiotics either because symptoms improve or due to financial constraints, leading to incomplete eradication of pathogens and promoting the survival of resistant strains. In resource-limited settings, poverty often forces individuals to seek cheaper alternatives, including purchasing antibiotics without prescriptions or relying on unverified traditional remedies. Lack of education further compounds the issue, as many individuals are unaware of the appropriate use of antibiotics or the consequences of their misuse. This includes the common misconception that antibiotics can treat viral infections such as the common cold or flu, which leads to unnecessary and ineffective use of these drugs [37].

Widespread self-medication, often fueled by the easy availability of antibiotics over the counter, especially in low- and middle-income countries, has become a serious public health concern. People may take antibiotics without proper diagnosis, incorrect dosages, or for inappropriate durations, all of which contribute significantly to the development and spread of resistant microorganisms. Despite numerous warnings, policy recommendations, and awareness campaigns by global and national health organizations, the overuse and misuse of antibiotics remain rampant. The unchecked consumption of these drugs in both human and veterinary medicine has accelerated resistance to the point where some infections are becoming increasingly difficult—or even impossible—to treat with existing antibiotics. This alarming trend indicates that the world may be approaching a post-antibiotic era, where common infections and minor injuries could once again become deadly due to the lack of effective treatments. Urgent, coordinated action is required across all sectors to avert this looming crisis [38].

Health care-related factors

Inappropriate prescriptions, incorrect dosing regimens, and a lack of up-to-date knowledge or training among healthcare professionals contribute to the problem. Improper prescription of antibiotics plays a major role in driving AMR [34]. A study revealed that 50% of hospitalised patients received at least one antibiotic without a valid justification [39]. Ideally, antibiotic use should be based on prior bacterial isolation and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. However, a 2017 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicated that approximately one-third of hospital patients were prescribed antibiotics without proper testing, and the treatment often extended beyond necessary durations. An incorrect dosing regimen is commonly found in nursing homes [40]. Nursing homes face an even more critical issue, where nearly 75% of antibiotic prescriptions are inappropriate, often due to incorrect dosing or duration of treatment [41].

These errors may arise from diagnostic uncertainty or external pressures to satisfy patient demands. Each of these categories plays a critical role in the propagation of AMR, necessitating a multifaceted and collaborative response involving public health authorities, clinicians, veterinarians, policymakers, and the general public.

Gross domestic product (GDP) factor

The notable increase in global antibiotic consumption is closely linked to rising GDP levels, particularly in developing and emerging economies [42]. As economic conditions improve in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), access to healthcare services, pharmaceuticals, and veterinary products becomes more widespread. This socioeconomic growth is often accompanied by enhanced living standards, urbanization, and dietary changes—all of which contribute to a higher demand for antibiotics. Improved affordability and availability of medicines have led to greater usage, both through formal healthcare systems and, in many cases, through informal channels lacking adequate regulation [42].

Klein et al [43], reported that between 2000 and 2015, global antibiotic consumption surged by approximately 65%, with LMICs accounting for much of this growth. This dramatic rise is attributed not only to population increases but also to expanding access to antibiotics driven by economic development. However, this trend has raised concerns due to the often indiscriminate or unregulated use of these drugs in both human and veterinary medicine, especially where oversight and diagnostic infrastructure are weak.

Furthermore, rising GDP levels have led to dietary transitions in many LMICs, with increased consumption of animal-based proteins such as meat, eggs, and dairy. This growing demand has intensified animal farming practices, often relying heavily on antibiotics for disease prevention, growth promotion, and productivity enhancement. The widespread use of antimicrobials in agriculture has created significant reservoirs of resistant bacteria, which can be transmitted to humans through direct contact, environmental pathways, and the food chain. Consequently, economic growth—while improving health outcomes and food security—has paradoxically fueled the global threat of AMR, particularly from animal sources [43].

Agricultural practices and AMR in livestock

Animal husbandry has long been an essential part of American and African agriculture, but since the 1950s, the rise of concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) has introduced new environmental and ethical challenges [44]. These include pollution of air and water with animal waste and growing concerns over animal welfare in such intensive systems. Another major issue is the heavy use of antimicrobial drugs in these facilities. While some of these drugs are used to prevent disease outbreaks in crowded conditions, most are actually administered to promote faster growth in animals [45].

Although it is not entirely clear how antibiotics enhance growth, many of the drugs used in livestock are chemically similar to those used in human medicine. This raises concerns because their use in animals can lead to the development of drug-resistant bacteria. Some of these bacteria can also resist antibiotics commonly used to treat human infections. For example, using tylosin in livestock has been linked to bacterial resistance to erythromycin, a macrolide antibiotic used in human healthcare.

These resistant bacteria can spread into the environment, contaminating soil and water near CAFOs. Even if these bacteria do not cause human disease directly, they can carry resistance genes that may be transferred to human pathogens. While cooking meat usually destroys any leftover antibiotics, the risk of resistance still persists, prompting many to advocate for stricter control over antibiotic use in agriculture [44].

In 2012, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released voluntary guidelines urging farmers to stop using antibiotics for growth promotion and to limit their use to situations involving veterinary supervision and legitimate health needs [45]. Although not legally enforced, the FDA promotes careful, or “judicious,” use of antimicrobials in livestock as a measure to curb the rise of antibiotic resistance.

Antibiotic use in poultry and cattle farms is largely unregulated, with studies from Jos, Abeokuta, and Northern Nigeria reporting indiscriminate use of tetracyclines, sulfonamides, and penicillins [46]. Antibiotics are commonly administered without veterinary consultation, sometimes for growth promotion, and often with poor adherence to withdrawal periods. These practices have resulted in the emergence of MDR E. coli strains with zoonotic potential, contributing to the contamination of meat, water, and surrounding environments.

Symptoms of antimicrobial resistance

The symptoms of an antibiotic-resistant infection are generally indistinguishable from those of infections caused by non-resistant bacteria. Common signs include fever, chills, night sweats, pain, fatigue, headaches, skin redness or tenderness, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea [47]. However, a key indication of antibiotic resistance is a lack of improvement after completing a prescribed antibiotic regimen. Additional signs that may suggest an antibiotic-resistant infection include: Prolonged healing time, worsening of the infection, potentially leading to severe complications, extended duration of illness with a higher risk of transmitting the infection to others, longer hospital admissions, increased need for follow-up medical consultations, higher treatment costs and the need for more toxic alternative therapies and greater likelihood of experiencing adverse drug reactions [48].

How to effectively handle antimicrobial resistance

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria pose a serious challenge in clinical settings, but they can often be managed effectively through tailored treatment strategies. One approach involves the use of alternative antibiotics or a combination of antibiotics specifically chosen based on the type of infection and the resistance profile of the bacteria. Health care providers often conduct laboratory tests, such as culture and sensitivity assays, to determine which antibiotics remain effective against the resistant strain. For instance, carbapenems—such as imipenem or meropenem—are considered powerful broad-spectrum antibiotics and are often used as a last resort to treat infections caused by multidrug-resistant organisms, including some strains of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [49].

In other cases, combination therapy may be employed, wherein an antibiotic is paired with a beta-lactamase inhibitor [50]. These inhibitors, such as clavulanic acid, tazobactam, or avibactam, are designed to block bacterial enzymes (like beta-lactamases) that would otherwise degrade the antibiotic, thereby restoring its efficacy. This approach is particularly useful for bacteria that have developed mechanisms to inactivate antibiotics through enzymatic destruction. In situations where antibiotic options are limited or ineffective, supportive care becomes crucial. Supportive care includes measures such as fluid replacement, oxygen therapy, pain management, and wound care, which help the body fight off the infection while minimizing further complications. In severe cases, surgical intervention may be necessary to remove infected tissues or drain abscesses [51].

The duration of treatment is not one-size-fits-all; it depends heavily on the type of infection, the causative organism, the site of infection, and the patient’s overall health status. For example, a mild urinary tract infection (UTI) caused by a resistant strain might be treated effectively within three to seven days. In contrast, more severe infections like bacterial endocarditis (an infection of the heart valves) often require intravenous antibiotic therapy for up to six weeks or longer, due to the complexity and risk associated with these infections. Additionally, patients with compromised immune systems, such as those with diabetes, HIV/AIDS, or those undergoing chemotherapy, may require extended or more aggressive treatment regimens. Regular monitoring and follow-up testing are essential to assess the effectiveness of therapy and to make any necessary adjustments [52].

Overall, while antibiotic resistance complicates treatment, a multifaceted approach that includes targeted antibiotic use, combination therapy, supportive care, and individualized treatment duration remains a viable and often successful strategy in combating these infections.

Recommendations

AMR poses a significant threat not only to human health but also to animals, plants, and the environment. Animals, like humans, can serve as reservoirs for MDR organisms, which may spread through direct contact or the consumption of animal-derived food products.

For Policy Makers

- Adopt and implement One Health policies

In 2008, the WHO, in collaboration with the FAO of the United Nations and the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), helped establish a strategic “One Health” framework aimed at addressing global health challenges [53]. The One Health model supports a wide range of sustainable development goals and is instrumental in the design, implementation, and monitoring of programs, policies, and research—particularly in AMR surveillance. This helps build a stronger evidence base and fosters advanced collaboration across sectors involving humans, animals, plants, and their shared environment. AMR, which significantly impacts human, animal, and environmental health, serves as a key example of a global issue that underscores the relevance and necessity of the One Health approach. Integrate human, animal, and environmental health strategies into national AMR action plans. Establish regulatory frameworks to govern antimicrobial use (AMU) across sectors, especially in agriculture and veterinary [53].

- Strengthen surveillance infrastructure

The unchecked sale and widespread self-medication of antibiotics remain persistent challenges in many countries, particularly in underdeveloped and low-income settings, where medications can often be obtained without a prescription from a licensed healthcare provider. In some cases, antibiotic prescriptions are influenced by patient demands rather than clinical need—an irresponsible practice that significantly contributes to the rise of AMR. To address this growing threat, policymakers must prioritize the establishment and enforcement of stringent regulatory controls [54]. Comprehensive legislation should be enacted to prohibit the illegal sale of antibiotics and ensure that their distribution is limited to authorized professionals. Equally important is the implementation of effective monitoring systems to ensure compliance across both public and private healthcare sectors [52,53]. Additionally, promoting evidence-based prescribing practices—such as delayed antibiotic prescribing, where medication use is deferred until symptoms clearly warrant it, accompanied by precise patient instructions—can significantly reduce inappropriate antibiotic use [54]. By adopting and enforcing these measures, policymakers can play a decisive role in curbing the spread of AMR and safeguarding public health. Veterinary surveillance systems linking hospitals, farms, and environmental sources (e.g., wastewater, soil, food chains). Mandate data sharing across ministries (health, agriculture, environment) to support coordinated responses.

- Ban non-therapeutic antibiotic use

Implementing and Enforcing Bans on Antibiotic Use as Growth Promoters in Livestock and Aquaculture, and Promoting Sustainable Alternatives. The routine use of antibiotics as growth promoters in animal husbandry and aquaculture has been identified as a major driver of AMR. To combat this, governments and regulatory bodies must enforce stringent bans or restrictions on the non-therapeutic use of antibiotics in livestock and aquatic farming. These regulations should prohibit the inclusion of antibiotics in animal feed or water solely for the purpose of enhancing growth or improving feed efficiency, especially when such usage is not based on a veterinary diagnosis. To ensure compliance, robust monitoring and surveillance systems should be established, coupled with penalties for violations. Additionally, capacity building for farmers and veterinary professionals should be prioritized to foster responsible antibiotic stewardship and awareness of AMR risks [55].

Simultaneously, viable and sustainable alternatives should be actively promoted and supported. These include: Probiotics and prebiotics, which improve gut health and nutrient absorption in animals, reducing the need for antibiotics. Vaccination programs can prevent common infectious diseases in livestock and fish, thereby minimising the need for treatment. Enhanced biosecurity and hygiene practices, such as regular cleaning of animal housing, clean water supply, and controlled animal movement, which reduce infection rates [49,50].

Improved animal nutrition and breeding practices, which enhance immunity and resilience to diseases. Encouraging the adoption of these alternatives not only supports animal health and productivity but also plays a crucial role in protecting public health by reducing the development and spread of resistant pathogens from animal sources to humans via the food chain, environment, or direct contact.

- Support LMIC capacity building

Provide sustained funding, comprehensive training, and robust infrastructure support to LMICs for effective AMR monitoring and containment. This includes allocating financial resources for the establishment and maintenance of well-equipped laboratories capable of conducting microbial surveillance, antibiotic susceptibility testing, and molecular diagnostics. Additionally, there should be structured training programs for healthcare professionals, veterinarians, pharmacists, and laboratory personnel on antimicrobial stewardship, infection prevention and control (IPC), and proper diagnostic techniques. Investment should also be directed toward building integrated surveillance systems that link human health, animal health, and environmental sectors in line with the One Health approach. Strengthening data collection, reporting mechanisms, and ensuring access to digital tools and information-sharing platforms will empower LMICs to detect emerging resistance patterns early, implement timely interventions, and contribute reliable data to global AMR databases. This holistic support is critical to bridge the capacity gap between high-income and resource-limited settings in the global fight against AMR [56].

For health professionals

- Implement antimicrobial stewardship programs

Prescribe antibiotics based on clinical guidelines, diagnostic evidence, and culture sensitivity results. Healthcare professionals should ensure that antibiotic prescriptions strictly follow evidence-based clinical guidelines that are appropriate for the specific condition being treated. Whenever possible, the decision to prescribe antibiotics should be supported by accurate diagnostic tests, including laboratory investigations and imaging, to confirm bacterial infection. Additionally, conducting culture and sensitivity tests helps identify the causative pathogen and determine the most effective antibiotic, thereby minimizing the risk of resistance development due to inappropriate or broad-spectrum antibiotic use [52].

- Educate patients on responsible antibiotic use and the risks of misuse.

It is vital to engage patients in conversations about the correct use of antibiotics. Patients should be informed that antibiotics are only effective against bacterial infections and are not a cure for viral illnesses such as the common cold or flu. They must be instructed to complete the full course of treatment, even if symptoms improve, to prevent incomplete eradication of bacteria and potential resistance. Furthermore, patients should be warned against self-medication, sharing antibiotics, or keeping leftover doses for future use. Clear communication can empower individuals to take responsibility for their antibiotic use and contribute to the global fight against AMR [53].

- Enhance infection prevention and control (IPC)

Strengthening IPC practices in healthcare settings is essential to reducing the transmission of AMR pathogens. Healthcare facilities must adopt rigorous IPC protocols, including consistent hand hygiene, proper sanitation, safe injection practices, appropriate use of PPE, and routine sterilization of medical instruments and surfaces. Hand hygiene, in particular, remains one of the most effective and low-cost interventions to prevent healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) [54].

Healthcare workers should be regularly trained and monitored to ensure compliance with IPC standards, and institutional policies should mandate routine audits and feedback mechanisms. In addition to hygiene measures, implementing comprehensive vaccination programs for both healthcare personnel and patients can reduce the incidence of vaccine-preventable diseases, thereby minimizing the unnecessary use of antibiotics and reducing selection pressure for resistance. Strengthening IPC not only safeguards patients and healthcare workers but also plays a critical role in maintaining the effectiveness of antimicrobial therapies

- Participate in AMR surveillance

The continued practice of non-prescription antibiotic sales and self-medication remains a serious concern in many low- and middle-income countries, where antibiotics are often accessible without a physician’s authorisation. In some settings, healthcare providers may also prescribe antibiotics in response to patient pressure rather than clinical indication, further exacerbating the inappropriate use of these medications [57]. Public health professionals have a critical role in addressing these behaviours that contribute to the escalation of AMR. Strengthening regulatory frameworks to restrict over-the-counter sales of antibiotics is essential. Equally important is the promotion of stewardship programs that support rational prescribing practices.

One effective approach is delayed antibiotic prescribing, where antibiotics are prescribed but their use is postponed until symptoms persist or worsen. This strategy, supported by clear patient education, has shown success in reducing unnecessary antibiotic consumption without compromising patient outcomes. To combat AMR effectively, public health efforts must focus on multisectoral collaboration, community engagement, provider training, and rigorous policy enforcement. These coordinated interventions can help preserve antibiotic efficacy and protect global health. Report resistance patterns to national health authorities and contribute data to surveillance networks [58].

- Engage in public awareness campaigns

The emergence and spread of AMR is frequently viewed as a biological phenomenon, but it is also deeply interconnected with a wide range of routine human activities and societal behaviors. These include household and animal hygiene, food production practices, health-seeking behaviors, and waste management systems. Poor hygiene, both at the domestic and livestock levels, can foster the spread of resistant microbes. Similarly, unsanitary food handling and agricultural practices—such as the excessive use of antibiotics in crops and livestock—create ideal environments for resistant bacteria to evolve and propagate. Inappropriate health-seeking behaviors, including the misuse and overuse of antibiotics without proper prescriptions, contribute significantly to AMR. This is particularly common in low- and middle-income countries, where antibiotics are often accessible over the counter without a prescription. Improper disposal of unused antibiotics and poor waste management systems further exacerbate the issue by allowing these substances to enter the environment and promote microbial adaptation and resistance [59].

To combat this growing threat, extensive public awareness campaigns are essential. These should be community-driven and culturally sensitive, aimed at educating the public on the dangers of antibiotic resistance, the health risks associated with self-medication, and the importance of adhering to prescribed antibiotic regimens [60]. Campaigns should also promote best practices in personal and environmental hygiene, encourage routine handwashing, proper sanitation, and responsible animal handling. Educating farmers on alternative approaches to antibiotic use in agriculture—such as vaccinations, probiotics, and improved biosecurity measures—can also help reduce dependence on antibiotics.

A well-informed population is more likely to make responsible health and hygiene choices, reducing the unnecessary use of antibiotics and helping to limit the spread of resistant microbes. Public health agencies, governments, schools, community leaders, and healthcare professionals must all collaborate in delivering these awareness efforts to ensure a holistic and sustainable approach to AMR prevention [59,60].

For agricultural stakeholders

- Adopt responsible antibiotic use practices

Use antimicrobials only when prescribed by a licensed veterinarian to ensure that treatments are appropriate, effective, and necessary. This practice helps prevent the misuse and overuse of antibiotics, which are major contributors to AMR. Farmers and livestock handlers should refrain from self-diagnosing or administering antibiotics without professional guidance, as incorrect dosing, duration, or drug selection can harm both animal health and public safety [44].

Maintain comprehensive records of all antimicrobial use, including the type of drug administered, dosage, duration of treatment, reason for use, and treatment outcomes [45]. These records not only support responsible antibiotic stewardship but also help veterinarians monitor the effectiveness of treatments, detect any adverse effects, and make informed decisions in future cases. Such documentation is essential for traceability, compliance with regulatory requirements, and promoting transparency and accountability within animal farming systems [61].

- Improve farm biosecurity and hygiene

To reduce the incidence of disease and lower the dependence on antibiotics, it is essential to improve overall animal husbandry practices. Enhancing housing conditions—such as providing adequate ventilation, space, and shelter—helps minimize stress and overcrowding, which are key risk factors for disease transmission. Proper nutrition strengthens the immune systems of animals, making them less susceptible to infections. Sanitation plays a vital role; maintaining clean environments, including regular disinfection of pens, equipment, and water sources, reduces exposure to pathogens [62].

In addition, isolating or quarantining sick animals promptly is crucial in preventing the spread of infectious diseases to healthy stock [63]. This practice allows for timely treatment and monitoring, while limiting the use of antibiotics to only those animals that truly need them. Together, these measures foster a healthier livestock population, reduce the need for routine antibiotic use, and contribute to the fight against antimicrobial resistance.

- Use alternatives to antibiotics

Investing in animal vaccination programs and natural growth promoters is a sustainable and effective strategy to reduce reliance on antibiotics in livestock production. Vaccination helps prevent common infectious diseases, thereby reducing the need for therapeutic antibiotic use. A well-implemented vaccination schedule can significantly lower disease incidence, improve animal health and welfare, and enhance productivity [63].

In addition, natural growth promoters such as herbal feed additives, essential oils, enzymes, prebiotics, and probiotics offer safe alternatives to antibiotic growth promoters. These substances improve digestion, enhance nutrient absorption, boost immune response, and promote overall gut health in animals [61]. Herbal additives, for example, possess antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties that support disease resistance and growth performance. By combining vaccination programs with the use of natural growth promoters, farmers can adopt a more holistic and responsible approach to animal health [61,62]. This not only supports antimicrobial stewardship but also aligns with global efforts to combat antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and meet consumer demand for safer, antibiotic-free animal products.

- Promote sustainable waste management

Treat and properly dispose of animal waste, wastewater, and manure to prevent contamination of water bodies and soil with resistant bacteria [64]. This involves implementing effective waste management systems such as composting, anaerobic digestion, or bio-digestion to reduce microbial load and neutralize harmful pathogens. Wastewater from animal farms should undergo proper treatment processes, including filtration, sedimentation, and disinfection, before being released into the environment. Manure should be stored in leak-proof containment systems and applied to agricultural land according to recommended guidelines to prevent runoff during rainfall. Regular monitoring of waste treatment systems and environmental quality should be enforced to ensure compliance with biosafety standards and minimize the risk of spreading antimicrobial-resistant organisms through environmental pathways [65].

Conclusion

AMR poses a critical and rapidly growing threat to global public health, jeopardizing decades of progress made in the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases. AMR occurs when microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites evolve to resist the effects of medications that once effectively treated them. This resistance severely limits treatment options, increases the risk of complications, and leads to longer illnesses, prolonged hospital stays, and higher mortality rates. One of the primary drivers of AMR is the misuse and overuse of antibiotics—not only in human medicine, where antibiotics are often prescribed unnecessarily or taken improperly, but also in agriculture and veterinary settings, where they are used routinely for growth promotion and disease prevention in livestock. These practices contribute to the emergence and spread of resistant strains, which can cross species and national borders with ease, further complicating the challenge.

The impact of AMR is particularly devastating in LMICs, where access to quality healthcare, diagnostics, and second-line treatments is limited. Here, the burden of infectious diseases is already high, and AMR only worsens health outcomes and deepens poverty by straining fragile healthcare systems and increasing treatment costs. Addressing AMR requires an urgent, coordinated, and multi-sectorial response. This includes the implementation of robust antibiotic stewardship programs to ensure responsible prescribing and usage; enhanced surveillance systems to monitor resistance patterns and track the spread of resistant organisms; and public education campaigns to raise awareness about the appropriate use of antimicrobials. Additionally, investment in research and development is vital to discover new antimicrobial agents, alternative therapies, rapid diagnostics, and vaccines. Strengthening infection prevention and control measures—such as hand hygiene, vaccination, sanitation, and hospital disinfection—is also crucial in preventing the spread of resistant infections.

Without sustained global action, AMR could result in a post-antibiotic era, where common infections and minor injuries become untreatable, reversing decades of medical advancement. To protect global health and ensure that future generations benefit from effective antimicrobial therapies, governments, health institutions, the private sector, and the public must act collectively and decisively to combat this silent pandemic.

What is already known about the topic

- Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a growing global threat caused by antimicrobial use in humans, animals, and agriculture.

- Resistant pathogens and genes move between humans, animals, and the environment, increasing disease burden, treatment failure, and healthcare costs.

- AMR also threatens food security by reducing livestock productivity and increasing the cost and risk of food production.

What this study adds

- This study highlights AMR as an interconnected human–animal–environment issue and links its impact on global health directly to food security.

- It emphasises gaps in surveillance and coordination across sectors and supports the need for integrated One Health approaches to control AMR and protect public health and sustainable food systems.

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful to God for the wisdom to put this up. We also sincerely acknowledge the contributions of researchers, clinicians, veterinarians, environmental health professionals, and policymakers whose work continues to advance understanding of (AMR) within the human–animal–environment interface. Their collective efforts have been instrumental in shaping the One Health approach that underpins this manuscript.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). The evolving threat of antimicrobial resistance: Options for action [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2012 [cited 2026 Jan 23]. 125 p. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/publications/evolving-threat-antimicrobial-resistance-options-action

- World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance: Global report on surveillance 2014 [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2014 Apr 1 [cited 2026 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564748

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US). Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. Atlanta (GA): CDC; 2013 [cited 2026 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/antimicrobial-resistance/media/pdfs/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf

- Morgan DJ, Okeke IN, Laxminarayan R, Perencevich EN, Weisenberg S. Non-prescription antimicrobial use worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis [Internet]. 2011 Sep [cited 2026 Jan 23];11(9):692-701. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1473309911700548 doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70054-8

- Marshall BM, Levy SB. Food animals and antimicrobials: impacts on human health. Clin Microbiol Rev [Internet]. 2011 Oct [cited 2026 Jan 23];24(4):718-33. Available from: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/CMR.00002-11 doi:10.1128/CMR.00002-11

- Founou RC, Founou LL, Essack SY. Clinical and economic impact of antibiotic resistance in developing countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2017 Dec 21 [cited 2026 Jan 23];12(12):e0189621. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189621 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0189621

- Stockwell VO, Duffy B. Use of antibiotics in plant agriculture. Rev Sci Tech OIE [Internet]. 2012 Apr 1 [cited 2026 Jan 23];31(1):199-210. Available from: https://doc.oie.int/dyn/portal/index.xhtml?page=alo&aloId=31378 doi:10.20506/rst.31.1.2104

- Novo A, André S, Viana P, Nunes OC, Manaia CM. Antibiotic resistance, antimicrobial residues and bacterial community composition in urban wastewater. Water Res [Internet]. 2013 Apr 1 [cited 2026 Jan 23];47(5):1875-87. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0043135413000274 doi:10.1016/j.watres.2013.01.010

- Monaco M, Giani T, Raffone M, Arena F, Garcia-Fernandez A, Pollini S, Collective Network EuSCAPE-Italy, Grundmann H, Pantosti A, Rossolini GM. Colistin resistance superimposed to endemic carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: a rapidly evolving problem in Italy, November 2013 to April 2014. Euro Surveill [Internet]. 2014 Oct 23 [cited 2026 Jan 23];19(42). Available from: https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.42.20939 doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.42.20939

- Reygaert WC. An overview of the antimicrobial resistance mechanisms of bacteria. AIMS Microbiol [Internet]. 2018 Jun 26 [cited 2026 Jan 23];4(3):482-501. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6604941 doi:10.3934/microbiol.2018.3.482

- Ghai I, Ghai S. Understanding antibiotic resistance via outer membrane permeability. Infect Drug Resist [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2026 Jan 23];11:523-30. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.2147/IDR.S156995 doi:10.2147/IDR.S156995

- Cox G, Wright GD. Intrinsic antibiotic resistance: Mechanisms, origins, challenges and solutions. Int J Med Microbiol [Internet]. 2013 Aug 1 [cited 2026 Jan 23];303(6):287-92. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1438422113000246 doi:10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.02.009

- Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, Harbarth S, Hindler JF, Kahlmeter G, Olsson-Liljequist B, Paterson DL, Rice LB, Stelling J, Struelens MJ, Vatopoulos A, Weber JT, Monnet DL. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect [Internet]. 2012 Mar [cited 2026 Jan 23];18(3):268-81. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1198743X14616323 doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x

- Delgado-Valverde M, Sojo-Dorado J, Pascual Á, Rodríguez-Baño J. Clinical management of infections caused by multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Ther Adv Infect [Internet]. 2013 Apr [cited 2026 Jan 23];1(2):49-69. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2049936113476284 doi:10.1177/2049936113476284

- Hashmi MZ. Entry routes of antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance in the environment. In: Hashmi MZ, Strezov V, Varma A, editors. Antibiotics and Antimicrobial Resistance Genes: Environmental Occurrence and Treatment Technologies. Cham (Switzerland): Springer; 2020 [cited 2026 Jan 23]. p. 1-26. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-40422-2

- Chaw PS, Höpner J, Mikolajczyk R. The knowledge, attitude and practice of health practitioners towards antibiotic prescribing and resistance in developing countries—A systematic review. J Clin Pharm Ther [Internet]. 2018 Oct [cited 2026 Jan 23];43(5):606-13. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jcpt.12730 doi:10.1111/jcpt.12730

- Wendlandt S, Shen J, Kadlec K, Wang Y, Li B, Zhang WJ, Feßler AT, Wu C, Schwarz S. Multidrug resistance genes in staphylococci from animals that confer resistance to critically and highly important antimicrobial agents in human medicine. Trends Microbiol [Internet]. 2015 Jan [cited 2026 Jan 23];23(1):44-54. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0966842X1400211X doi:10.1016/j.tim.2014.10.002

- Fernández L, Hancock REW. Adaptive and mutational resistance: role of porins and efflux pumps in drug resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev [Internet]. 2012 Oct [cited 2026 Jan 23];25(4):661-81. Available from: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/CMR.00043-12 doi:10.1128/CMR.00043-12

- Choi U, Lee CR. Distinct roles of outer membrane porins in antibiotic resistance and membrane integrity in Escherichia coli. Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2019 Apr 30 [cited 2026 Jan 23];10:953. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00953/full doi:10.3389/fmicb.2019.00953

- Martinez JL. General principles of antibiotic resistance in bacteria. Drug Discov Today Technol [Internet]. 2014 Mar [cited 2026 Jan 23];11:33-9. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S174067491400002X doi:10.1016/j.ddtec.2014.02.001

- Akintoyese TO, Alao JO, Oladipo EK, Oyedemi OT, Oyawoye OM. Antimicrobial resistance and virulence in Klebsiella pneumoniae: a four-month study in Osogbo, Nigeria. ASHE [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2026 Jan 23];5(1):e64. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S2732494X2500021X/type/journal_article doi:10.1017/ash.2025.21

- Salami WO, Ajoseh SO, Lawal-Sanni AO, El Tawab AA, Neubauer H, Wareth G, Akinyemi KO. Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance patterns, and emerging carbapenemase-producing Enterococcus species from different sources in Lagos, Nigeria. Antibiotics [Internet]. 2025 Apr 12 [cited 2026 Jan 23];14(4):398. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2079-6382/14/4/398 doi:10.3390/antibiotics14040398

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): General information about MRSA in the community [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; 2016 [cited 2026 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mrsa/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/mrsa/community/index.html

- Hutchings MI, Truman AW, Wilkinson B. Antibiotics: past, present and future. Curr Opin Microbiol [Internet]. 2019 Oct [cited 2026 Jan 23];51:72-80. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1369527419300190 doi:10.1016/j.mib.2019.10.008

- Levy SB, Marshall B. Antibacterial resistance worldwide: causes, challenges and responses. Nat Med [Internet]. 2004 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 23];10(12 Suppl):S122-9. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nm1145 doi:10.1038/nm1145

- Arcilla MS, Van Hattem JM, Haverkate MR, Bootsma MCJ, Van Genderen PJJ, Goorhuis A, Grobusch MP, Oude Lashof AM, Molhoek N, Schultsz C, Stobberingh EE, Verbrugh HA, De Jong MD, Melles DC, Penders J. Import and spread of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae by international travellers (COMBAT study): a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis [Internet]. 2017 Jan [cited 2026 Jan 23];17(1):78-85. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S147330991630319X doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30319-X

- Michael CA, Dominey-Howes D, Labbate M. The antimicrobial resistance crisis: causes, consequences, and management. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2014 Sep 16 [cited 2026 Jan 23];2:145. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2014.00145/full doi:10.3389/fpubh.2014.00145

- Zaman SB, Hussain MA, Nye R, Mehta V, Mamun KT, Hossain N. A review on antibiotic resistance: alarm bells are ringing. Cureus [Internet]. 2017 Jun 28 [cited 2026 Jan 23];9(6):e1403. Available from: https://www.cureus.com/articles/7900-a-review-on-antibiotic-resistance-alarm-bells-are-ringing doi:10.7759/cureus.1403

- Parmar A, Lakshminarayanan R, Iyer A, Mayandi V, Goh ETL, Lloyd DG, Chalasani MLS, Verma NK, Prior SH, Beuerman RW, Madder A, Taylor EJ, Singh I. Design and syntheses of highly potent teixobactin analogues against Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) in vitro and in vivo. J Med Chem [Internet]. 2018 Mar 8 [cited 2026 Jan 23];61(5):2009-17. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01634 doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01634

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAI): General information about VISA/VRSA [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; 2016 [cited 2026 Jan 23]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/HAI/organisms/visa_vrsa/visa_vrsa.html

- Sulis G, Sayood S, Katukoori S, Bollam N, George I, Yaeger LH, Chavez MA, Tetteh E, Yarrabelli S, Pulcini C, Harbarth S, Mertz D, Sharland M, Moja L, Huttner B, Gandra S. Exposure to World Health Organization’s AWaRe antibiotics and isolation of multidrug resistant bacteria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect [Internet]. 2022 Sep [cited 2026 Jan 23];28(9):1193-202. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1198743X22001537 doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2022.05.011

- Suay-García B, Pérez-Gracia MT. Present and future of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections. In: Advances in Clinical Immunology, Medical Microbiology, COVID-19, and Big Data. Singapore: Jenny Stanford Publishing; 2021 [cited 2026 Jan 23]. p. 435-56. Available from: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/9781003180432-23/present-future-carbapenem-resistant-enterobacteriaceae-infections-beatriz-suay-garc%C3%ADa-mar%C3%ADa-teresa-p%C3%A9rez-gracia

- Koch N, Islam NF, Sonowal S, Prasad R, Sarma H. Environmental antibiotics and resistance genes as emerging contaminants: Methods of detection and bioremediation. Curr Res Microb Sci [Internet]. 2021 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 23];2:100027. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2666517421000080 doi:10.1016/j.crmicr.2021.100027

- Parmanik A, Das S, Kar B, Bose A, Dwivedi GR, Pandey MM. Current treatment strategies against multidrug-resistant bacteria: a review. Curr Microbiol [Internet]. 2022 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 23];79(12):388. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00284-022-03061-7 doi:10.1007/s00284-022-03061-7

- Castro-Sánchez E, Moore LSP, Husson F, Holmes AH. What are the factors driving antimicrobial resistance? Perspectives from a public event in London, England. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2016 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 23];16(1):465. Available from: https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-016-1810-x doi:10.1186/s12879-016-1810-x

- Holmes AH, Moore LSP, Sundsfjord A, Steinbakk M, Regmi S, Karkey A, Guerin PJ, Piddock LJV. Understanding the mechanisms and drivers of antimicrobial resistance. Lancet [Internet]. 2016 Jan 9 [cited 2026 Jan 23];387(10014):176-87. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673615004730 doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00473-0

- DiMasi JA, Grabowski HG, Hansen RW. Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: New estimates of R&D costs. J Health Econ [Internet]. 2016 May [cited 2026 Jan 23];47:20-33. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0167629616000291 doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2016.01.012

- Davies J, Davies D. Origins and evolution of antibiotic resistance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev [Internet]. 2010 Sep [cited 2026 Jan 23];74(3):417-33. Available from: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/MMBR.00016-10 doi:10.1128/MMBR.00016-10

- Friedman ND, Temkin E, Carmeli Y. The negative impact of antibiotic resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect [Internet]. 2016 May [cited 2026 Jan 23];22(5):416-22. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1198743X15010289 doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2015.12.002

- Nathwani D, Varghese D, Stephens J, Ansari W, Martin S, Charbonneau C. Value of hospital antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs): a systematic review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control [Internet]. 2019 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 23];8:35. Available from: https://aricjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13756-019-0471-0 doi:10.1186/s13756-019-0471-0

- Pulia M, Kern M, Schwei RJ, Shah MN, Sampene E, Crnich CJ. Comparing appropriateness of antibiotics for nursing home residents by setting of prescription initiation: a cross-sectional analysis. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control [Internet]. 2018 Jun 14 [cited 2026 Jan 23];7:74. Available from: https://aricjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13756-018-0364-7 doi:10.1186/s13756-018-0364-7

- Browne AJ, Chipeta MG, Haines-Woodhouse G, Kumaran EPA, Hamadani BKH, Zaraa S, Henry NJ, Deshpande A, Reiner RC Jr, Day NPJ, Lopez AD, Dunachie S, Moore CE, Stergachis A, Hay SI, Dolecek C. Global antibiotic consumption and usage in humans, 2000–18: a spatial modelling study. Lancet Planet Health [Internet]. 2021 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 23];5(12):e893-904. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2542519621002801 doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00280-1

- Klein EY, Impalli I, Poleon S, Denoel P, Cipriano M, Van Boeckel TP, Pecetta S, Bloom DE, Nandi A. Global trends in antibiotic consumption during 2016–2023 and future projections through 2030. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A [Internet]. 2024 Dec 3 [cited 2026 Jan 23];121(49):e2411919121. Available from: https://pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2411919121 doi:10.1073/pnas.2411919121

- Landers TF, Cohen B, Wittum TE, Larson EL. A review of antibiotic use in food animals: perspective, policy, and potential. Public Health Rep [Internet]. 2012 Jan-Feb [cited 2026 Jan 23];127(1):4-22. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/003335491212700103 doi:10.1177/003335491212700103

- Ghimpețeanu OM, Pogurschi EN, Popa DC, Dragomir N, Drăgotoiu T, Mihai OD, Petcu CD. Antibiotic use in livestock and residues in food—a public health threat: a review. Foods [Internet]. 2022 May 16 [cited 2026 Jan 23];11(10):1430. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/11/10/1430 doi:10.3390/foods11101430

- Mbindyo CM, Gitao GC, Plummer PJ, Kulohoma BW, Mulei CM, Bett R. Antimicrobial resistance profiles and genes of staphylococci isolated from mastitic cow’s milk in Kenya. Antibiotics [Internet]. 2021 Jun 24 [cited 2026 Jan 23];10(7):772. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2079-6382/10/7/772 doi:10.3390/antibiotics10070772

- Nkollo MI, Odogu A. New developments in the optometrist’s assessment and treatment of common headaches. Ad Med Pharma Den RE [Internet]. 2025 Feb 11 [cited 2026 Jan 23];5(1):1. Available from: http://apc.aast.edu/ojs/index.php/AMPDR/article/view/AMPDR.2025.05.1.1116 doi:10.21622/AMPDR.2025.05.1.1116

- Oliver SP, Murinda SE, Jayarao BM. Impact of antibiotic use in adult dairy cows on antimicrobial resistance of veterinary and human pathogens: a comprehensive review. Foodborne Pathog Dis [Internet]. 2011 Mar [cited 2026 Jan 23];8(3):337-55. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1089/fpd.2010.0730 doi:10.1089/fpd.2010.0730