Research | Open Access | Volume 9 (1): Article 20 | Published: 30 Jan 2026

Trends in cervical cancer screening uptake and cytology outcomes at Kiambu Level 5 Hospital, Kenya

Menu, Tables and Figures

Navigate this article

Tables

| Pap smear screening | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age categories (years) | n = 3475 (100%) |

| 18–19 | 16 (0.5%) |

| 20–29 | 534 (15.4%) |

| 30–39 | 1129 (32.5%) |

| 40–49 | 1147 (33%) |

| 50–59 | 461 (13.3%) |

| >60 | 188 (5.4%) |

| Initial screening visit | |

| Age (years) | n = 2160 (62.2%) |

| 18–19 | 16 (0.7%) |

| 20–29 | 431 (20%) |

| 30–39 | 700 (32.4%) |

| 40–49 | 625 (28.9%) |

| 50–59 | 265 (12.3%) |

| >60 | 123 (5.7%) |

| Routine screening | |

| Age (years) | n = 1315 (37.8%) |

| 18–19 | 0 (0%) |

| 20–29 | 103 (7.8%) |

| 30–39 | 429 (32.6%) |

| 40–49 | 522 (39.7%) |

| 50–59 | 196 (14.9%) |

| >60 | 65 (4.9%) |

| HIV status (n = 3475, 100%) | |

| Negative | 2113 (60.8%) |

| Positive | 1192 (34.3%) |

| Unknown | 170 (4.9%) |

| Follow-up period (n = 3475, 100%) | |

| < 6 months | 1156 (33.3%) |

| 1 year | 908 (26.1%) |

| 1–4 years | 1266 (36.4%) |

| >5 years | 43 (1.2%) |

| Unknown | 102 (2.9%) |

Table 1. Characteristics of women who underwent Pap smear screening at the cervical cancer clinic, 2014–2020

| Screening Test | HIV status | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Unknown | |

| Pap Smear | 201 (16.9%) | 1759 (83.2%) | 128 (75.3%) |

| VIA | 991 (83.1%) | 354 (16.8%) | 42 (24.7%) |

| Total | 1192 | 2113 | 170 |

Table 2. The screening test was performed as per client’s HIV status

| Variable | Pap smear results | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Premalignant | Malignant | |

| Age (years) | |||

| 18–19 | 7 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| 20–29 | 323 (15.4%) | 12 (11.4%) | 0 (0%) |

| 30–39 | 611 (29.1%) | 26 (24.8%) | 0 (0%) |

| 40–49 | 694 (33.10%) | 35 (33.3%) | 1 (50%) |

| 50–59 | 314 (15%) | 21 (20%) | 0 (0%) |

| >60 | 149 (7.1%) | 11 (10.5%) | 1 (50%) |

| Follow-up period | |||

| < 6 months | 642 (30.6%) | 28 (26.7%) | 2 (100%) |

| 1 year | 256 (12.2%) | 31 (29.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| 1–4 years | 1103 (52.6%) | 42 (40%) | 0 (0%) |

| >5 years | 33 (1.6%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Not indicated | 64 (3.1%) | 3 (2.9%) | 0 (0%) |

Table 3. The results of the Pap smears are further described by age and follow-up period. Percentages are presented as column percentages

| Cyto-diagnosis | Classification | Number (%) n=3354 |

|---|---|---|

| Specimen adequacy | ||

| Satisfactory | 3294 (98.2%) | |

| Unsatisfactory | 60 (1.8%) | |

| Non-neoplastic findings | ||

| NILM | 3115 (94.6%) | |

| Cervicitis | 1009 (66.7%) | |

| Atrophic vaginitis | 206 (13.6%) | |

| Atrophic smear | 129 (8.5%) | |

| Bacterial vaginosis | 118 (7.8%) | |

| Candida | 21 (1.4%) | |

| Cervicitis, bacterial vaginosis | 12 (0.4%) | |

| Cervicitis, Candida | 11 (0.4%) | |

| Actinomyces | 5 (0.3%) | |

| Premalignant | ||

| ASC-US | 49 (2.6%) | |

| ASC-H | 30 (0.9%) | |

| LSIL | 7 (0.2%) | |

| HSIL | 86 (2.6%) | |

| Malignant | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 2 (0.06%) | |

| Glandular cell abnormalities | ||

| AGC | 5 (0.2%) |

Abbreviations: NILM, negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy; ASC-US, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; ASC-H, atypical squamous cells (cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion); LSIL, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; AGC, atypical glandular cells.

Table 4. Cytological findings based on the Bethesda classification

Figures

Keywords

- Pap smear

- Cervical cancer

- Screening uptake

- Cytology outcomes

- Bethesda classification

Molly Mukii Maundu1, Kinara Fossa2, Magoma Mwancha-Kwasa1, David Ndegwa1, Prabhjot Kaur Juttla3,&, Rashida Admani1, Francis Makokha4

1Department of Health, County Government of Kiambu, Kiambu, Kiambu County, Kenya, 2Central Province Responses Integration Strengthening and Sustainability Project (CRISSP), University of Nairobi, Nairobi County, Kenya, 3Faculty of Health Sciences, School of Medicine, University of Nairobi, Nairobi County, Kenya, 4Directorate of Research and Innovation, Mount Kenya University, Thika, Kiambu County, Kenya

&Corresponding author: Prabhjot Kaur Juttla, Faculty of Health Sciences, School of Medicine, University of Nairobi, Nairobi County, Kenya, Email: pkjuttla13@gmail.com ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-7227-7949

Received: 04 Sep 2025, Accepted: 27 Jan 2026, Published: 30 Jan 2026

Domain: Cancer Epidemiology

Keywords: Pap smear, Cervical cancer, Screening uptake, Cytology outcomes, Bethesda classification

©Molly Mukii Maundu et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Molly Mukii Maundu et al., Trends in cervical cancer screening uptake and cytology outcomes at Kiambu Level 5 Hospital, Kenya. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2026; 9(1):20. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00183

Abstract

Introduction: Cervical cancer remains a major public health concern in Kenya, yet facility-level data describing Pap smear screening uptake and cytology outcomes within routine health services are limited. This study described trends in Pap smear screening uptake and patient cytology outcomes at Kiambu Level 5 Hospital (KL5H) between 2014 and 2020.

Methods: We conducted a facility-based retrospective study utilising data extracted from the cervical cancer screening and treatment daily activities register (MOH 412) and the Pap smear laboratory register. Descriptive statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 12.

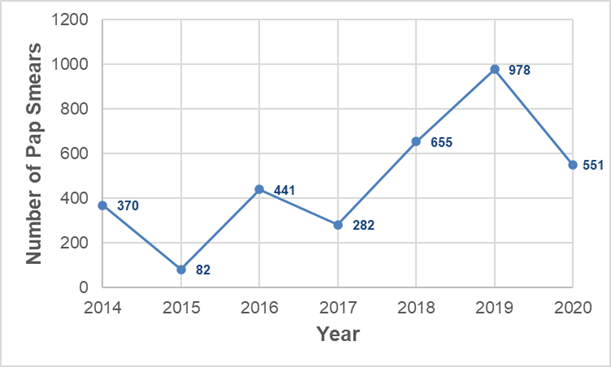

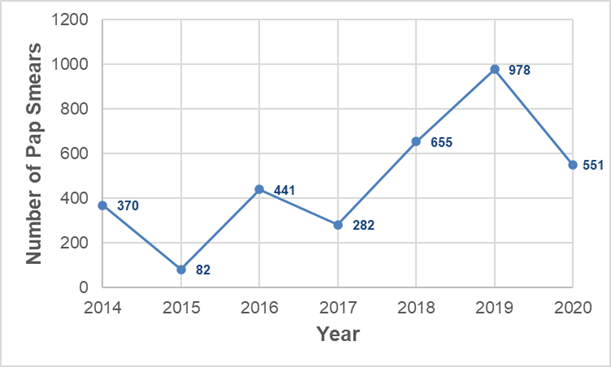

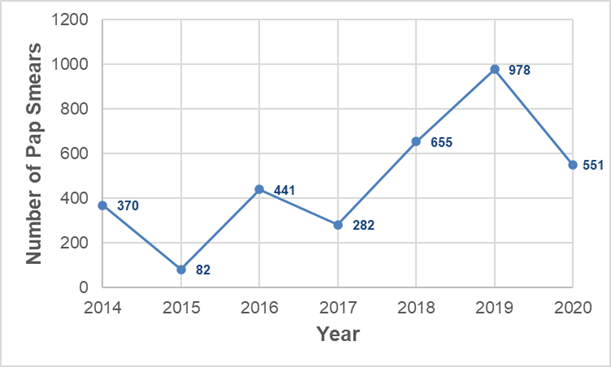

Results: A total of 3,457 women underwent Pap smear screening within the study period. Among these, 33.0% (1,147/3,457) were aged 40–49 years, 34.3% (1,192/3,457) were HIV positive, and 62.2% (2,160/3,457) were index screening tests. The Pap smear results indicated that the majority (94.6%) were negative for intraepithelial lesions or malignancy, while 5.4% exhibited premalignant Pap smears. Only 0.06% of the participants had malignant Pap smear results. Annual Pap smear screening increased from 370 women in 2014 to a peak of 978 in 2019, before declining to 551 in 2020.

Conclusion: Most women screened had normal cytology results, with a small proportion showing premalignant or malignant lesions. Pap smear screening uptake at KL5H increased following clinic establishment, with fluctuations over time and a decline observed in 2020. These findings underscore the importance of sustaining facility-based cervical cancer screening services and support the need for targeted efforts to maintain and enhance screening coverage in the county.

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most frequently diagnosed cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer mortality among women globally, with an estimated 604,000 new cases and 342,000 deaths reported annually [1]. The majority of these deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [2], where late detection contributes significantly to the higher mortality rates reported in these countries [3]. In Kenya, cervical cancer represents approximately 12% of all cancer diagnoses and is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women, accounting for over 3,200 fatalities in 2020 [2].

Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest regional incidence of cervical cancer worldwide [4], largely due to the high prevalence of HIV, which increases susceptibility to persistent human Papillomavirus (HPV) infection. HPV causes approximately 99% of cervical cancer cases [5]. Countries with a high HIV burden, such as Kenya, therefore experience disproportionately elevated cervical cancer incidence rates [6]. Although HPV testing is the recommended primary screening method for cervical cancer [7], its implementation in LMICs is limited by resource constraints [8]. As a result, screening programs in these settings commonly rely on alternative methods, including Pap smears, Visual Inspection with Acetic Acid (VIA), and Visual Inspection with Lugol’s Iodine (VILI). These approaches detect cytological abnormalities in the cervical transformation zone [9] and are endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO) because of their feasibility in LMIC contexts [10]. In Kenya, these methods are incorporated into the national cervical cancer screening algorithm [7].

Research indicates that early cervical cancer screening can reduce mortality rates and the incidence of advanced disease [6,10–12]. These benefits, however, can only be fully realised through extensive coverage of the target population, combined with prompt and accurate diagnostic follow-up. The WHO recommends that cervical cancer screening be targeted at women aged 30 years and older [1], and in line with these efforts, cervical cancer screening in Kenya targets primarily women aged 21 to 49 to undergo screening [7]. The recommended screening frequency in Kenya varies based on HIV status: HIV-negative women should be screened every five years, while HIV-positive women are advised to be screened annually [7]. For women over the age of 59, the frequency may be tailored according to individual risk factors and prior screening history.

Although Kenya has improved cervical cancer screening coverage among women aged 25–49 years from 5% in 2018 to 30.3% in 2024 [8], these screening rates remain below the screening target of 70% [7,8,13]. Moreover, current evidence on longitudinal Pap smear screening trends within routine clinical settings remains limited, and existing reports largely focus on national estimates [14]. Therefore, this study aimed to quantify trends in cervical cancer screening uptake and cytology outcomes at Kiambu Level 5 Hospital (KL5H) between 2014 and 2020, and to describe the demographic characteristics of women undergoing Pap smear screening.

Methods

Study design

This was a retrospective, cross-sectional, descriptive facility-based study that described all the results of Pap smears obtained from the cervical cancer screening clinic of KL5H, covering seven years from 1st January 2014 to 31st December 2020.

Study setting

Kiambu County is one of the 47 counties in the Republic of Kenya, situated to the north of Nairobi, the capital city. The geolocation of KL5H is approximately -1.1712 latitude and 36.8301 longitude. KL5H is notable for hosting the only clinical cytologist (at the time of the study) who provides services to all public health facilities in the county. According to the 2019 census, Kiambu County had a population of 2,417,735, with women of childbearing age (15 to 49 years) comprising 543,901 individuals [15].

Study population

The study population consisted of all women who underwent Pap smear screening at KL5H during the study period. All Pap smear results recorded in the laboratory register were included in the study, provided the patient’s age was documented. Data were also included from the cervical cancer screening and DAR, capturing variables such as age, type of visit, screening test performed, HIV status, and follow-up duration. Pap smears for women whose age was not indicated were excluded from the study.

Bethesda Classification System

According to the Bethesda Classification System for Reporting Cervical Cytologic Diagnoses, the Pap smear findings were classified as follows: atypical squamous cells (ASC), which include atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US) and atypical squamous cells where high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) cannot be excluded (ASC-H); low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL); high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL); squamous cell carcinoma (SCC); and atypical glandular cells (AGC). Additionally, non-malignant findings, including benign cellular changes, infections, and reactive cellular alterations, were also described.

Data sources

Data were extracted from two routine Ministry of Health registers. The Cervical Cancer Screening and Treatment Daily Activity Register (DAR) (MOH 412) provided information on client demographics and screening encounters, including age, type of visit (initial or follow-up), screening method used (Pap smear or VIA), HIV status, and date of screening. Although VIA screening was conducted at the facility, this analysis focuses on women who underwent Pap smear testing; VIA results are presented descriptively by HIV status only.

The Cervical Cytology Laboratory DAR recorded Pap smear results, including cytological category according to the Bethesda classification and date of smear processing. Data were abstracted manually into a coded Excel sheet by trained research personnel. The unique patient identifiers between the registers were not traceable to the respective patient, and therefore, it was not possible to link the specific patient file with the respective cytology outcome.

Clinical context and patient follow-up procedure

Screening at KL5H is offered as part of routine outpatient health services. Women presenting to the facility for cervical cancer screening, HIV care or general outpatient consultation are counselled and offered Pap smear screening in line with national guidelines [7]. Screening is therefore opportunistic and based on patient attendance and provider recommendation, rather than formal recruitment or invitation. Screening is performed primarily using Pap smear cytology or VIA/VILI according to the national screening algorithm set out in the policy guidance [7].

This study did not involve active follow-up of participants. The registers used different identifiers from the patient files, preventing reliable linkage of individual records to their respective results. As a result, follow-up and repeat-testing information was captured only when explicitly documented in the routine facility registers. However, the general practice and approach to follow-up was carried out in accordance with national cervical cancer screening guidelines [7], whereby women with negative results were advised to return for routine screening at the recommended interval, while those with abnormal results were referred for further diagnostic evaluation and management.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered into a secure spreadsheet, cross-checked for consistency, and cleaned to address missing or inconsistent values. Analysis was performed using STATA version 12 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, 77845 USA). The characteristics of the participants were summarized into frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. Data were presented in tables and charts.

Of the 3,475 women recorded in the screening register, 3,457 underwent Pap smear testing. Of these, 3,354 specimens were satisfactory for cytological evaluation and included in Bethesda classification analyses. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise participant characteristics and screening outcomes. Categorical variables were summarised using frequencies and proportions. A line graph was generated to visualize yearly trends in screening uptake. Frequency tables were used to illustrate the distribution of demographic and clinical characteristics. No inferential statistical tests were applied, as the study objective was descriptive and trend-focused. All findings are presented with corresponding denominators to ensure transparency in reporting.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was sought and granted from the University of Eastern Africa, Baraton, reference number: UEAB/REC/09/06/2020. Permission from KL5H and the Kiambu County Department of Health was also obtained. Data obtained from the study were kept confidential by limiting access to the data to only the data entry clerks, statistician, principal investigator, and authors.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

Out of the 3,457 women who had done a Pap smear test, the majority were aged between 40 – 49 years old, followed by women between 30 and 39 years old. Among the women getting their initial screening, the majority were between the ages of 30 and 39 years old. For routine re-screenings, the majority of the women were between 40 – 49 years old (Table 1). The most commonly recorded follow-up interval was 1–4 years (36.4%). Of the women screened, 1,192 (34.3%) were HIV positive. The majority of the women who were HIV positive or negative screened using VIA and Pap smear, respectively (Table 2).

Screening outcomes and follow-up period

Table 3 shows the age categories and follow-up periods of the women as per the Pap smear results. The majority of those with a premalignant smear were between 40-49 years old. There were two cases with malignancy, one was between the ages of 40-49 years old and the other above 60 years old. Those with premalignant lesions who were scheduled for follow-up within 6 months and 1 year were 28 (26.7%) and 31 (29.5%), respectively. All those with a malignant result had a follow-up in less than 6 months (n = 2, 100%) (Table 3).

Bethesda classification of Pap smears

About 98.2% of the Pap smears done had a satisfactory specimen adequacy (Table 4). Only 5.4% of women had premalignant smears, with HSIL and ASC-US each accounting for 2.6% of results. A majority (66.7%) of the non-neoplastic changes were cervicitis, while the least common pattern was actinomycoses (Table 4).

Uptake of Pap smear test from January 2014 to December 2020

From 1st January 2014 to 31st December 2020, a total of 3457 women visited KL5H for Pap smear test screening. Figure 1 illustrates the annual breakdown of Pap smears uptake from the operationalization of the clinic until 2020. The number of women screened increased from 370 in 2014 to 441 in 2016, decreased to 282 in 2017, then increased to 978 in 2019, before declining to 551 in 2020. In 2015, only 82 women were screened (Figure 1).

Discussion

In Kenya, cervical cancer is the leading cause of cancer mortality among women [10]. In 2020, the Global Cancer Observatory, through the International Agency for Research on Cancer, reported a 19.7% increase in new cervical cancer cases among women of all ages in Kenya [2]. Within Kiambu County, only one cytologist was serving the 543,901 women of childbearing age across public health facilities in the county at the time of data collection for this study. The majority of women screened using Pap smear tests received NILM results, which aligns with findings from a study conducted at Kenyatta National Hospital, although that study focused on women with positive VIA results [16].

In contrast, the proportion of women exhibiting low-grade lesions (LSIL and ASC) and high-grade lesions (HSIL and AGUS) in the present study diverged from a previous investigation of cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions among HIV-infected and uninfected women in Central Kenya [10]. That study reported LSIL cytology rates 90 times higher than those observed in our study, with ASC-US and AGUS rates being 10 and 15 times greater, respectively. This discrepancy may be attributed to the latter study’s recruitment strategy, which involved a 4:1 ratio of HIV-positive to HIV-negative participants. Furthermore, we found that HSIL was the most common pre-malignant lesion detected, with a prevalence of 2.6%. This finding is consistent with the general population’s HSIL prevalence, which ranges from 0.5% to 3.0% [17].

In this study, premalignant cervical lesions were most commonly detected among women aged 40 years and above. Similar age patterns have been reported elsewhere [18]. This pattern is likely attributable to the risk of persistent HPV infection increasing with age and longer durations of infection, allowing more time for progression to cervical abnormalities. These findings highlight the importance of maintaining regular screening for women in this age group (40 – 49 years old), while also continuing to promote earlier screening to prevent progression to high-grade disease, in line with risk-based screening recommendations [7].

Among patients who underwent Pap smear screening, 29.4% exhibited additional non-neoplastic findings, with approximately half of these cases diagnosed as cervicitis. This proportion of inflammatory findings aligns with a study conducted in a rural area of Himachal Pradesh, India, where 32.5% of symptomatic women presented with similar inflammatory findings upon Pap smear examination [19]. Similarly, another study from Southern Ethiopia reported that half of the women with non-cancerous lesions were diagnosed with cervicitis [20]. The high proportion of cervicitis observed among women with non-neoplastic findings likely reflects the opportunistic nature of screening at KL5H, where women are offered screening irrespective of symptoms. As a result, the screened population may include women with concurrent reproductive tract infections or inflammatory conditions, which are commonly detected during cytological examination in routine clinical settings.

In this study, six in ten women underwent Pap smear screening, while four in ten were screened using VIA, reflecting the service mix available at KL5H, a relatively well-equipped referral facility. Screening modality differed by HIV status, with most HIV-positive women screened using VIA and most HIV-negative women receiving Pap smear screening. This pattern reflects the integration of cervical cancer screening within HIV care services, where VIA is commonly used to support “screen-and-treat” approaches that allow same-day clinical decision-making [8]. As a result, cytology-based findings from Pap smears may under-represent screening outcomes among HIV-positive women, a group at higher risk of persistent HPV infection and cervical abnormalities. Expanding access to HPV testing and/or cytology services within HIV care pathways could improve screening equity, comparability of outcomes, and follow-up for this high-risk population.

Most visits for screening were for initial assessments, with nearly two-thirds of women aged 30 to 49 years, consistent with WHO age recommendations for screening [10]. The high proportion of women aged 40–49 years returning for routine rescreening suggests ongoing engagement with screening services among women who have already entered the screening pathway. Although the age at first screening could not be established from routine registers, the observed pattern indicates that repeat screening is occurring within the age group at highest risk for progression to premalignant disease. This aligns with WHO guidance that meaningful reductions in cervical cancer risk can be achieved even with limited lifetime screening, provided screening reaches women at appropriate ages [5].

Interpretation of scheduled follow-up intervals should be made cautiously because these values reflect routine clinic documentation rather than confirmed return attendance. In addition, follow-up interval recommendations in Kenya vary by HIV status and test results [7]; therefore, observed patterns may reflect a mixture of routine re-screening schedules, clinical review for symptoms, and management of abnormal findings. Improving documentation and using harmonised patient identifiers across screening and laboratory registers would allow clearer assessment of adherence to guideline-based follow-up.

Since the operationalisation of the screening clinic in 2014, we observed an increase in service utilisation, with a decline in 2015, 2017 and 2020. The very low screening volume recorded in 2015 may reflect early clinic implementation challenges, service disruptions, or incomplete routine documentation. The reduction in Pap smear uptake observed in 2017 coincides with the nationwide doctors’ strike in Kenya, which disrupted routine outpatient services and limited access to preventive care, including cervical cancer screening [21]. Lastly, the 2020 decline is attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic. This observation aligns with a meta-analysis that reported a decrease in cervical cancer screening uptake due to the pandemic [22]. To mitigate potential long-term consequences from this most-proximal event, strengthening awareness efforts and ensuring accessible screening services remain important to support continued use of cervical cancer screening services.

Overall, more than 84% of the women screened were over the age of 30, aligning with Kenya’s National Guidelines for cervical cancer screening, which recommend screening women above this age [7]. This also reflects WHO guidelines (that have been adopted in Kenya) advocating for screening 70% of women at least once in their lifetime [8,23]. This reflects strong alignment with national recommendations and demonstrates the clinic’s reach to the priority screening age group. The low prevalence (5.46%) of premalignant and malignant findings among screened women likely reflects both routine screening in an asymptomatic population and the importance of maintaining access to preventive services.

Study limitations

This study provides insight into screening utilization and cytology outcomes at a single high-volume public facility but does not measure population-level screening coverage or early detection outcomes. Therefore, conclusions regarding screening program effectiveness at county or national level cannot be drawn. There was no standardized unique patient identifier across the Ministry of Health (MOH 412) cervical cancer screening register and the laboratory Pap smear register. As a result, it was not possible to reliably link individual screening encounters with corresponding laboratory results or follow-up records, leading to unknown outcomes for some women. Strengthening health information systems, including the implementation of universal patient identifiers across clinical and laboratory platforms, would enhance continuity of care and support future evaluations of screening pathways and outcomes. Additionally, it was not feasible to compare histological reports from biopsies of women with abnormal Pap smears, as this data was unavailable. Finally, this study used descriptive analysis only; inferential statistics were not applied. Therefore, observed trends should be interpreted as descriptive patterns rather than statistically tested associations.

Recommendations

To enhance follow-up and continuity of care, it is crucial to adopt unique identifiers for patients across cervical cancer registers and laboratory records. Furthermore, robust public health campaigns are needed to increase the uptake of cervical cancer screening, expand the screening capacity of healthcare facilities, and encourage women overdue for screening to attend their appointments.

Conclusion

This facility-based review demonstrates increasing utilisation of Pap smear screening services at a public referral hospital in Kenya following clinic establishment, with notable disruptions during periods of health system strain. Screening largely reached women within the recommended age range, and cytology outcomes were predominantly normal, reflecting routine preventive screening. While population-level impact cannot be assessed from these data, the findings underscore the need to sustain cervical cancer screening services, strengthen integration within routine care, and improve health information systems to support continuity of care and long-term cancer prevention.

What is already known about the topic

- Cervical cancer remains a leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women in Kenya, with a disproportionately high burden in settings with elevated HIV prevalence.

- Pap smear cytology continues to be widely used for cervical cancer screening in low- and middle-income countries where access to HPV testing is limited.

- Early detection through cervical cancer screening reduces morbidity and mortality, but screening coverage and continuity of care remain inconsistent in resource-constrained health systems.

What this study adds

- Provides a seven-year (2014–2020) facility-based analysis of Pap smear screening uptake and cytology outcomes at a public referral hospital in Kiambu County, Kenya.

- Shows that most Pap smear results were negative for intraepithelial lesions or malignancy, with a small proportion of premalignant and malignant findings concentrated among women in higher-risk age groups, underscoring the importance of sustaining routine screening services

- Demonstrates that screening uptake increased following clinic establishment but was disrupted during periods of health system strain, including the COVID-19 pandemic and nationwide service disruptions

Authors´ contributions

M.M.M. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, investigation, and drafting of the original manuscript. K.F. was responsible for formal analysis, data curation, and reviewing and editing the manuscript. M.M-K. contributed through investigation, supervision, project administration, and manuscript review and editing. D.N. supported data acquisition, validation, and manuscript editing. P.K.J. contributed to the writing of the original draft, as well as review and editing, and served as the corresponding author. R.A. provided resources, clinical oversight, and contributed to manuscript review and editing. F.M. contributed through supervision and manuscript review and editing.

| Pap smear screening | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age categories (years) | n = 3475 (100%) |

| 18–19 | 16 (0.5%) |

| 20–29 | 534 (15.4%) |

| 30–39 | 1129 (32.5%) |

| 40–49 | 1147 (33%) |

| 50–59 | 461 (13.3%) |

| >60 | 188 (5.4%) |

| Initial screening visit | |

| Age (years) | n = 2160 (62.2%) |

| 18–19 | 16 (0.7%) |

| 20–29 | 431 (20%) |

| 30–39 | 700 (32.4%) |

| 40–49 | 625 (28.9%) |

| 50–59 | 265 (12.3%) |

| >60 | 123 (5.7%) |

| Routine screening | |

| Age (years) | n = 1315 (37.8%) |

| 18–19 | 0 (0%) |

| 20–29 | 103 (7.8%) |

| 30–39 | 429 (32.6%) |

| 40–49 | 522 (39.7%) |

| 50–59 | 196 (14.9%) |

| >60 | 65 (4.9%) |

| HIV status (n = 3475, 100%) | |

| Negative | 2113 (60.8%) |

| Positive | 1192 (34.3%) |

| Unknown | 170 (4.9%) |

| Follow-up period (n = 3475, 100%) | |

| < 6 months | 1156 (33.3%) |

| 1 year | 908 (26.1%) |

| 1–4 years | 1266 (36.4%) |

| >5 years | 43 (1.2%) |

| Unknown | 102 (2.9%) |

| Screening Test | HIV status | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Unknown | |

| Pap Smear | 201 (16.9%) | 1759 (83.2%) | 128 (75.3%) |

| VIA | 991 (83.1%) | 354 (16.8%) | 42 (24.7%) |

| Total | 1192 | 2113 | 170 |

| Variable | Pap smear results | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Premalignant | Malignant | |

| Age (years) | |||

| 18–19 | 7 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| 20–29 | 323 (15.4%) | 12 (11.4%) | 0 (0%) |

| 30–39 | 611 (29.1%) | 26 (24.8%) | 0 (0%) |

| 40–49 | 694 (33.10%) | 35 (33.3%) | 1 (50%) |

| 50–59 | 314 (15%) | 21 (20%) | 0 (0%) |

| >60 | 149 (7.1%) | 11 (10.5%) | 1 (50%) |

| Follow-up period | |||

| < 6 months | 642 (30.6%) | 28 (26.7%) | 2 (100%) |

| 1 year | 256 (12.2%) | 31 (29.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| 1–4 years | 1103 (52.6%) | 42 (40%) | 0 (0%) |

| >5 years | 33 (1.6%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Not indicated | 64 (3.1%) | 3 (2.9%) | 0 (0%) |

| Cyto-diagnosis | Classification | Number (%) n=3354 |

|---|---|---|

| Specimen adequacy | ||

| Satisfactory | 3294 (98.2%) | |

| Unsatisfactory | 60 (1.8%) | |

| Non-neoplastic findings | ||

| NILM | 3115 (94.6%) | |

| Cervicitis | 1009 (66.7%) | |

| Atrophic vaginitis | 206 (13.6%) | |

| Atrophic smear | 129 (8.5%) | |

| Bacterial vaginosis | 118 (7.8%) | |

| Candida | 21 (1.4%) | |

| Cervicitis, bacterial vaginosis | 12 (0.4%) | |

| Cervicitis, Candida | 11 (0.4%) | |

| Actinomyces | 5 (0.3%) | |

| Premalignant | ||

| ASC-US | 49 (2.6%) | |

| ASC-H | 30 (0.9%) | |

| LSIL | 7 (0.2%) | |

| HSIL | 86 (2.6%) | |

| Malignant | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 2 (0.06%) | |

| Glandular cell abnormalities | ||

| AGC | 5 (0.2%) |

References

- World Health Organization. WHO guideline for screening and treatment of cervical pre-cancer lesions for cervical cancer prevention. 2nd ed. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2021 Jul 6 [cited 2026 Jan 30]. 97 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030824. Also available from: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/329a5f3d-b423-48b3-beb1-26ee1240c0a3/content

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021 Feb 4 [cited 2026 Jan 30];71(3):209-49. Available from: https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/caac.21660. doi:10.3322/caac.21660

- Feletto E, Grogan P, Nickson C, Smith M, Canfell K. How has COVID-19 impacted cancer screening? Adaptation of services and the future outlook in Australia. Public Health Res Pract. 2020 Dec 9 [cited 2026 Jan 30];30(4):e3042026. Available from: https://connectsci.au/pu/article/30/4/e3042026/265081/How-has-COVID-19-impacted-cancer-screening. doi:10.17061/phrp3042026

- Dzinamarira T, Moyo E, Dzobo M, Mbunge E, Murewanhema G. Cervical cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: an urgent call for improving accessibility and use of preventive services. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2023 Apr [cited 2026 Jan 30];33(4):592-7. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1048891X24024289. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2022-003957

- Orang’o EO, Were E, Rode O, Muthoka K, Byczkowski M, Sartor H, Vanden Broeck D, Schmidt D, Reuschenbach M, Von Knebel Doeberitz M, Bussmann H. Novel concepts in cervical cancer screening: a comparison of VIA, HPV DNA test and p16INK4a/Ki-67 dual stain cytology in Western Kenya. Infect Agents Cancer. 2020 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 30];15(1):57. Available from: https://infectagentscancer.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13027-020-00323-6. doi:10.1186/s13027-020-00323-6

- Wright TC, Kuhn L. Alternative approaches to cervical cancer screening for developing countries. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012 Apr [cited 2026 Jan 30];26(2):197-208. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1521693411001660. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2011.11.004

- Ministry of Health, Kenya. National Cancer Screening and Early Diagnosis Guidelines. 2nd ed. Nairobi (Kenya): Ministry of Health, Kenya; 2024 [cited 2026 Jan 30]. 146 p. Available from: http://guidelines.health.go.ke:8000/media/National_Cancer_Screening_Guidelines_2024_1.pdf

- Ministry of Health, Kenya. Kenya national cancer screening guidelines. Nairobi (Kenya): Ministry of Health, Kenya; 2018 [cited 2026 Jan 30]. 121 p. Available from: https://arua-ncd.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/National-Cancer-Screening-Guidelines-2018.pdf

- Pangarkar MA. The Bethesda System for reporting cervical cytology. Cytojournal. 2022 Apr 30 [cited 2026 Jan 30];19:28. Available from: https://cytojournal.com/the-bethesda-system-for-reporting-cervical-cytology/. doi:10.25259/CMAS_03_07_2021

- Shami S, Coombs J. Cervical cancer screening guidelines: An update. JAAPA. 2021 Sep 1 [cited 2026 Jan 30];34(9):21-4. Available from: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/329a5f3d-b423-48b3-beb1-26ee1240c0a3/content

- Sawaya GF, Smith-McCune K, Kuppermann M. Cervical Cancer Screening: More Choices in 2019. JAMA. 2019 May 28 [cited 2026 Jan 30];321(20):2018. Available from: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.2019.4595. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.4595

- Ministry of Health, Kenya. Kenya Intensifies Efforts to Combat Cervical Cancer Amid Rising Burden [Internet]. Nairobi (Kenya): Ministry of Health; 2025 Dec 2 [cited 2026 Jan 30]. Available from: https://www.health.go.ke/kenya-intensifies-efforts-combat-cervical-cancer-amid-rising-burden

- Mwenda V, Mburu W, Bor JP, Nyangasi M, Arbyn M, Weyers S, Tummers P, Temmerman M. Cervical cancer programme, Kenya, 2011–2020: lessons to guide elimination as a public health problem. ecancermedicalscience. 2022 Aug 26 [cited 2026 Jan 30];16:1442. Available from: https://ecancer.org/en/journal/article/1442-cervical-cancer-programme-kenya-2011-2020-lessons-to-guide-elimination-as-a-public-health-problem. doi:10.3332/ecancer.2022.1442

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. 2019 Kenya Population and Housing Census: Volume V: Distribution of Population by Socio-Economic Characteristics. Nairobi (Kenya): Kenya National Bureau of Statistics; 2019 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 30]. 476 p. Available from: https://www.knbs.or.ke/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/2019-Kenya-population-and-Housing-Census-Volume-4-Distribution-of-Population-by-Socio-Economic-Characteristics.pdf

- Chagwa PJ. Pap smear cytological findings in women with abnormal visual inspection test results referred to Kenyatta National Hospital [master’s thesis]. Nairobi (Kenya): University of Nairobi; 2013 [cited 2026 Jan 30]. 62 p. Available from: UoN eRepository – Full PDF

- Edmund SC, Barbara SD. Cytology Diagnostic Principles and Clinical Correlates. 5th ed. Amsterdam (Netherlands): Elsevier; 2020 Mar 27.

- Kaabia O, Bouchahda R, Kahla AB. #1019 Cervical cancer in young women: epidemiological features, therapeutic characteristics and prognosis. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2023 Sep [cited 2026 Jan 30];33(Suppl 3):A106. Available from: https://ijgc.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/ijgc-2023-ESGO.217. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2023-ESGO.217

- Verma A, Verma S, Vashist S, Attri S, Singhal A. A study on cervical cancer screening in symptomatic women using Pap smear in a tertiary care hospital in rural area of Himachal Pradesh, India. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2017 Mar [cited 2026 Jan 30];22(1):39-42. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1110569016300668. doi:10.1016/j.mefs.2016.09.002

- Ameya G, Yerakly F. Characteristics of cervical disease among symptomatic women with histopathological sample at Hawassa University referral hospital, Southern Ethiopia. BMC Womens Health. 2017 Sep 29 [cited 2026 Jan 30];17:91. Available from: http://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12905-017-0444-5. doi:10.1186/s12905-017-0444-5

- Irimu G, Ogero M, Mbevi G, Kariuki C, Gathara D, Akech S, Barasa E, Tsofa B, English M. Tackling health professionals’ strikes: an essential part of health system strengthening in Kenya. BMJ Glob Health. 2018 Nov 28 [cited 2026 Jan 30];3(6):e001136. Available from: https://gh.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001136. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001136

- Mayo M, Potugari B, Bzeih R, Scheidel C, Carrera C, Shellenberger RA. Cancer Screening During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 30];5(6):1109-17. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2542454821001557. doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2021.10.003

- Canfell K, Kim JJ, Brisson M, Keane A, Simms KT, Caruana M, Burger EA, Martin D, Nguyen DTN, Bénard É, Sy S, Regan C, Drolet M, Gingras G, Laprise JF, Torode J, Smith MA, Fidarova E, Trapani D, Bray F, Ilbawi A, Broutet N, Hutubessy R. Mortality impact of achieving WHO cervical cancer elimination targets: a comparative modelling analysis in 78 low-income and lower-middle-income countries. Lancet. 2020 Jan 30 [cited 2026 Jan 30];395(10224):591-603. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673620301574. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30157-4