Research | Open Access | Volume 9 (1): Article 18 | Published: 29 Jan 2026

Incidence, trend and geographical disparity of malaria in pregnancy, Savannah Region, Ghana, 2018-2022

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Tables

| Variable | Suspected | Tested | Positives | ANC | MiP IR / 1,000 [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MiP | MiP (%) | MiP (%) | Reg | ||

| Year | |||||

| 2018 | 8,357 | 7,843 | 4,739 | 22,181 | 213.7 [208.3 – 217.1] |

| 2019 | 11,857 | 10,505 | 5,416 | 23,604 | 229.5 [224.1 – 234.9] |

| 2020 | 10,760 | 9,249 | 5,413 | 24,614 | 219.9 [214.8 – 225.1] |

| 2021 | 9,057 | 8,152 | 4,223 | 25,155 | 167.9 [163.3 – 172.6] |

| 2022 | 11,448 | 10,985 | 5,673 | 25,266 | 224.5 [219.4 – 229.7] |

| Age | |||||

| 10–19 yrs | 10,048 | 9,144 | 5,392 | 16,906 | 318.9 [311.9 – 326.0] |

| 20–34 yrs | 32,853 | 29,838 | 16,293 | 86,716 | 187.9 [185.3 – 190.5] |

| 35+ yrs | 8,578 | 7,752 | 3,779 | 17,198 | 219.7 [213.6 – 226.0] |

| District | |||||

| Bole | 16,797 | 14,723 | 10,315 | 25,646 | 402.2 [396.2 – 408.2] |

| Central Gonja | 12,144 | 11,380 | 5,104 | 27,427 | 186.1 [181.5 – 190.6] |

| East Gonja | 5,813 | 5,586 | 2,423 | 19,731 | 122.8 [118.3 – 127.5] |

| North Gonja | 2,594 | 2,228 | 1,329 | 11,353 | 117.1 [111.2 – 123.1] |

| North-East Gonja | 1,827 | 1,496 | 563 | 7,344 | 76.7 [70.6 – 83.0] |

| Sawla-Tuna-Kalba | 7,048 | 6,197 | 4,289 | 17,480 | 245.4 [239.0 – 251.8] |

| West Gonja | 5,256 | 5,124 | 1,441 | 11,839 | 121.7 [115.9 – 127.7] |

| Total | 51,479 | 46,734 | 25,464 | 120,820 | 210.8 [208.5 – 213.1] |

*IR = Incidence Rate

Figures

Keywords

- Malaria in pregnancy

- Trend

- Savannah Region

- Ghana

Jonathan Wadeyir Abesig1, Joseph Chantiwuni Nindow1, Annungma Christopher Bagonluri2, Kwabena Adjei Sarfo3,&, Magdalene Akos Odikro4, Gyesi Razak Issahaku4, George Akowah4, Delia Akosua Bandoh4, Ernest Kenu4, Williams Azumah Abanga5, Chrysantus Kubio3

1Ghana Health Service, Bole District Hospital, Bole, Savannah Region, Ghana, 2Ghana Health Service, Sawla-Tuna-Kalba District Health Directorate, Sawla, Savannah Region, 3Savannah Regional Health Directorate, Ghana Health Service, Damongo, Ghana, 4Ghana Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program, School of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, University of Ghana, Legon, Accra, 5Saboba District Health Directorate, Ghana Health Service, Saboba, Ghana

Received: 25 Mar 2025, Accepted: 26 Jan 2026, Published: 29 Jan 2026

Domain: Maternal Health

Keywords: Malaria in pregnancy, trend, Savannah region, Ghana

©Jonathan Wadeyir Abesig et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Jonathan Wadeyir Abesig et al., Incidence, trend and geographical disparity of malaria in pregnancy, Savannah Region, Ghana, 2018-2022. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2026; 9(1):18. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00101

Abstract

Introduction: Malaria in pregnancy (MiP) remains a major public health concern in Ghana despite the heavy investment in the fight against malaria. The burden of MiP in the Savannah Region is not well documented. This study described the incidence and distribution of MiP in the region from 2018 to 2022.

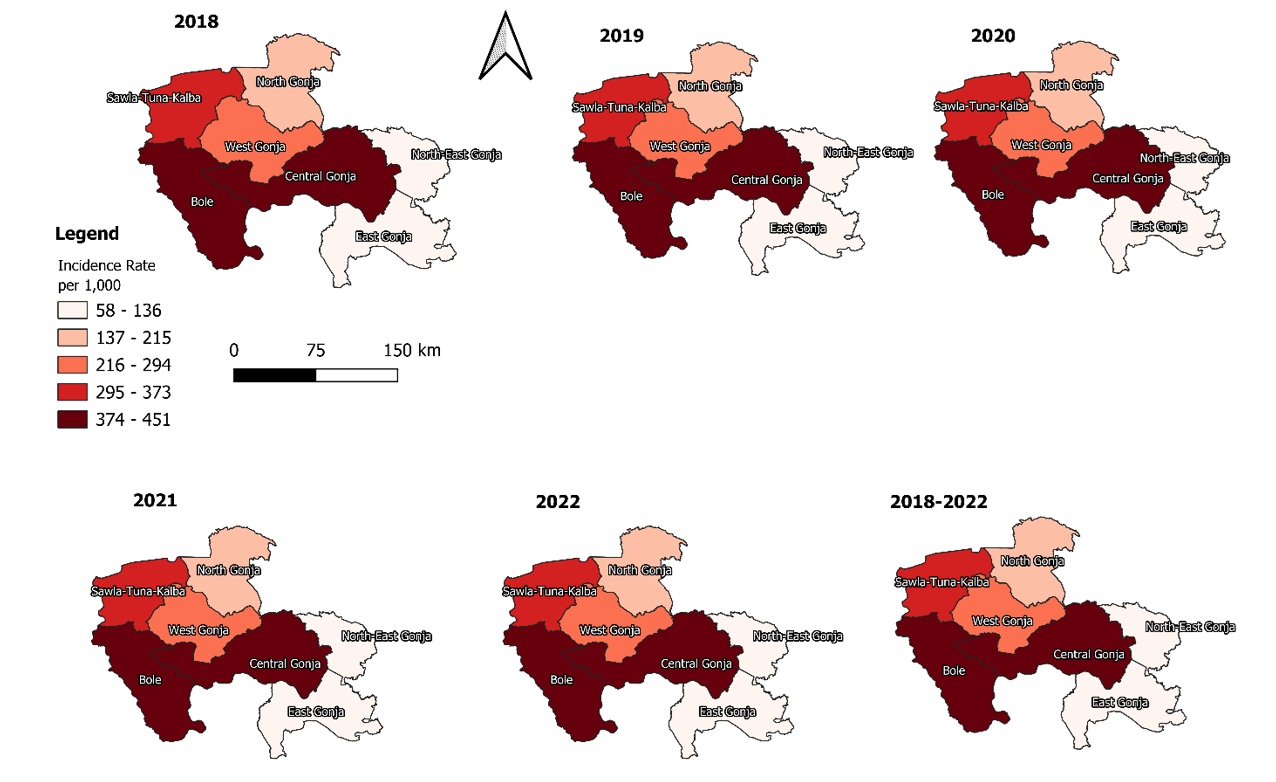

Methods: We carried out a cross-sectional descriptive analysis. Institutional MiP and ANC data from 2018 to 2022 in the Savannah Region, was extracted from DHIMS2 and sent to Microsoft Excel 19. Descriptive statistical analyses were performed. Results were summarized in tables, graphs, and maps.

Results: A total of 51,479 pregnant women were suspected of malaria, out of which 90.8% (46,734/51,479) were tested. More than half of the pregnant women were confirmed positive for malaria, 54.5% (54.0 – 54.9). Most of the cases were among adolescent pregnant women, 59.0% (58.0 – 60.0). The incidence of MiP over the five years was 210.8 (208.5 – 213.1) per 1,000. Adolescent pregnant women were more affected, 318.9 (311.9 – 326.0) per 1,000. The highest incidence was reported in the Bole District, 402.2 (396.2 – 408.2) per 1,000 pregnant women, while the North-East-Gonja District reported the lowest incidence, 76.7 (70.6 – 83.0) per 1,000. The trend of the MiP was relatively stable, marginally increasing from 213.7 (208.3 – 217.1) per 1,000 in 2018 to 224.5 (219.4 – 229.7) per 1,000 in 2022.

Conclusion: The incidence of MiP in the Savannah Region was high, with Bole District recording the highest incidence among the seven districts of the region. There is a need for community-level education, especially among pregnant women, on adherence to malaria control interventions. Further research is required to help determine factors associated with MiP in high-incidence districts.

Introduction

Malaria in pregnancy (MiP) continues to be a public health issue with significant deleterious effects on the health of both mothers and children [1]. Maternal anaemia, low birthweight, premature delivery, and maternal and newborn mortalities are among the problems linked to MiP [2–8]. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that in 2021, 13.3 million pregnant women were exposed to malaria in Africa [9].

In Ghana, three key strategies are employed for the elimination of pregnancy-related malaria: case management, sulfadoxine-pyramethamine intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy (IPTp) and use of insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs) [10].Notwithstanding the huge investment made to eliminate malaria, the disease remains a serious health issue among pregnant women in Ghana. For instance, pregnant women continue to have a high rate of positive malaria tests, even though a study reported the rate declined from 54.0% to 34.5% between 2014 and 2021 [11]. Also, the prevalence of MiP in Ghana is 5–11% in the coastal areas, 5–20% in the transition and forest zones, and 13–26% in the northern savannah zone [12]. Other researchers reported malaria prevalence among pregnant women to be 20.9% in the Shai-Odoku District [13], 20.4% in the Bono East Region [14], and between 13.4% to 14.1% in northern Ghana [15].

Previous studies have revealed the burden of malaria in the general population and children under five years in Ghana and the Bole District of the Savannah Region [13, 16, 17]. Malaria infections are reported among pregnant women seeking care at the various healthcare facilities across the Savannah Region. However, despite the routine surveillance of malaria in the region, the incidence of malaria during pregnancy is not well documented. Therefore, there is a need to research the incidence of MiP in the Savannah Region to help understand the burden. The findings will also help inform the implementation of interventions and strategies for the elimination of malaria during pregnancy. We described the incidence, trend and geographical disparities of MiP in the Savannah Region.

Methods

Study design and setting

We carried out a descriptive cross-sectional study of MiP secondary data from the District Health Information Management System 2 (DHIMS2) from 2018 to 2022. This study was conducted in Ghana’s Savannah Region. It is part of the newly established regions in 2019 and was carved out from the Northern Region. There are seven districts in the region with an estimated 653,266 population [18]. It is the largest region in terms of landmass, covering about 15% of Ghana’s land area with 35,862 km2. There are 206 health facilities in the region, including district hospitals, polyclinics, health centers and Community-based Health Planning Services (CHPS) compounds [19]. The region’s vegetation is mainly grassland, with two seasons. The rainy season is from May to November, whereas the dry season begins in December and ends in April. The general vegetation has favourable conditions for malaria transmission [20]. Most of the inhabitants are engaged in farming and agricultural activities. There are some communities in the region in which illegal mining (Galamsey) activities take place. Dollar Power, located in the Bole District, is one such community. The region is home to the Mole National Park, exposing the population to vector-borne diseases. The White and Black Volta Rivers and their tributaries traverse the region, affecting access to healthcare services in the rainy season [19].

Operational definitions

ANC registrant: a pregnant woman booked at any of the ANC clinics to start and continue antenatal care.

Suspected MiP case: any pregnant woman with fever within the previous two days.

Tested MiP case: a suspected malaria in pregnancy case for which a malaria test is carried out either using a malaria Rapid Diagnostic Test (mRDT) or a microscopy test.

Positive MiP: any pregnant woman tested and malaria parasites are confirmed to be present using mRDT or microscopy.

MiP incidence rate: number of positive MiP cases divided by ANC registrants multiplied by 1,000.

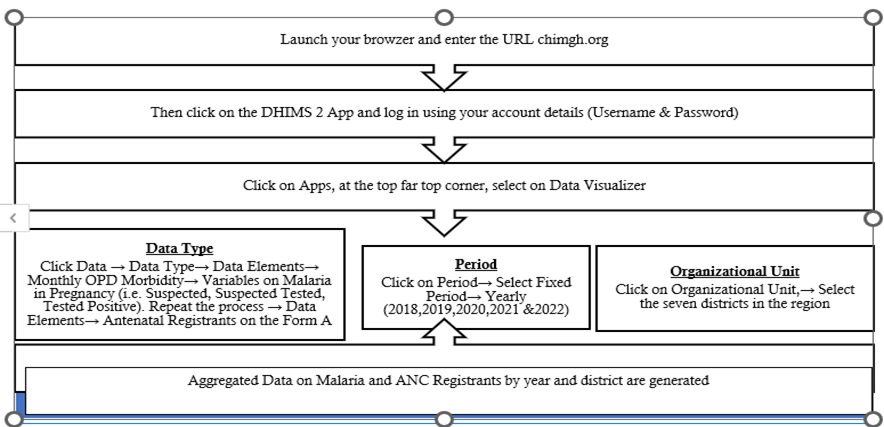

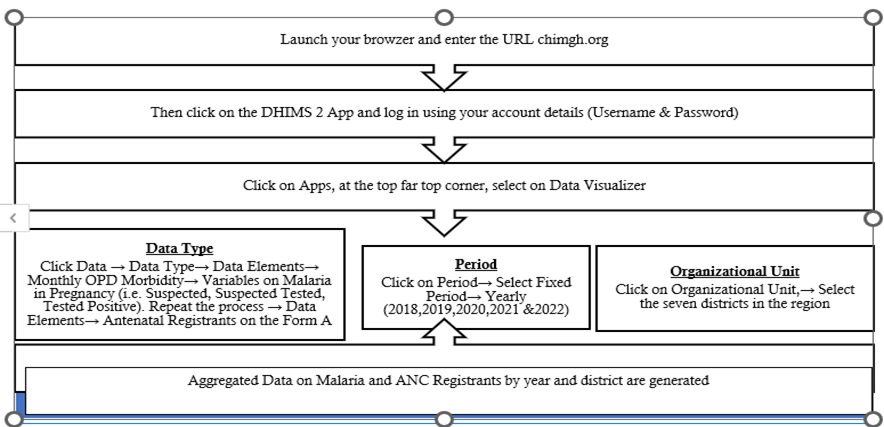

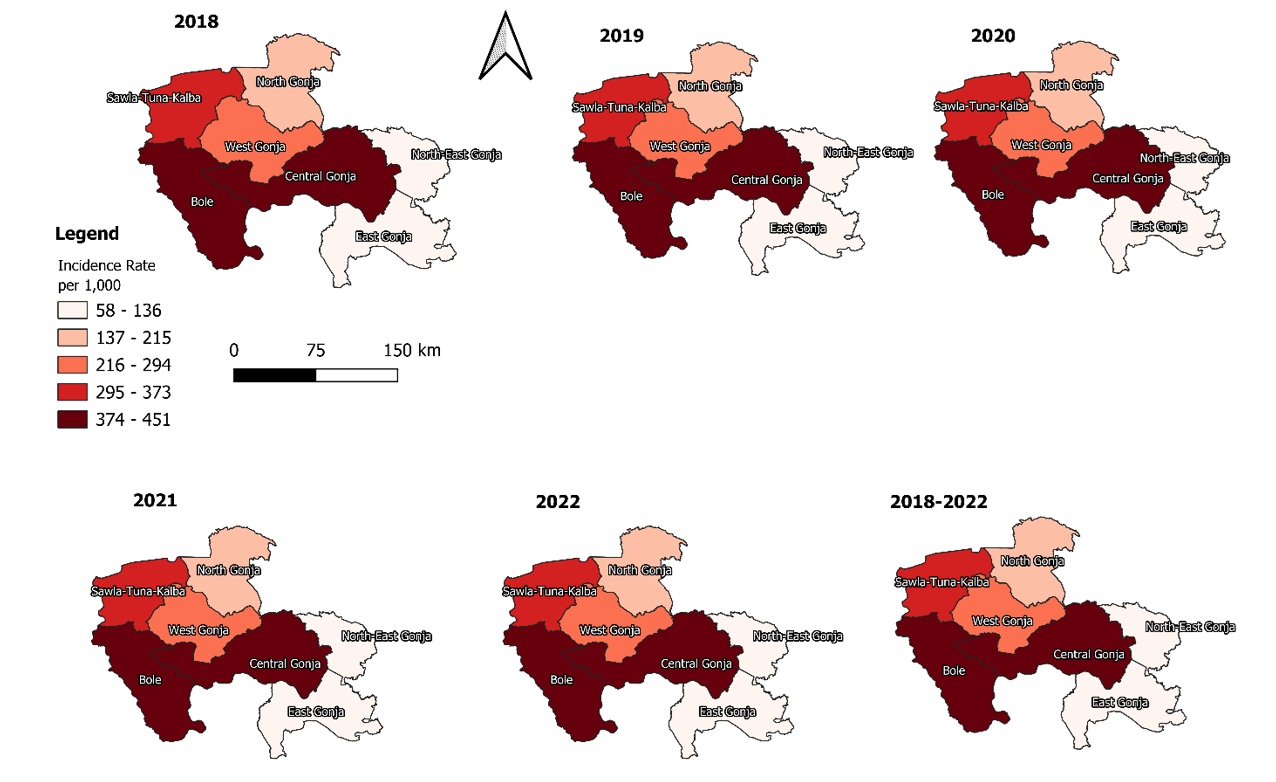

Data collection

MiP data was extracted from DHIMS2 for the period 2018 to 2022 using the Pivot Table App. The DHIMS2 is a digital database used to maintain data on health services provided by health facilities across Ghana [21]. The extracted data was exported into Microsoft Excel version 19. We extracted the following MiP variables based on district, age and year: the number of suspected MiP, tested MiP, and positive MiP. These were the available variables in the routine DHIMS2 dataset for this study. We also extracted the total antenatal (ANC) registrants for each year per district. For analytical purposes, the DHIMS2 data extracted were categorized into 10-19 years, 20-34 years, and 35 years and above based on established pregnancy risk profiles [22–24]. Adolescents (10-19 years) and older pregnant women (35 years and above) are recognized as high-risk groups for adverse maternal and pregnancy outcomes, including malaria in pregnancy, while women aged 20-34 years represent the lower-risk reference group. The risk-based categorization was applied to facilitate meaningful comparison of malaria burden across maternal risk groups and to enhance the programmatic relevance of the findings for maternal health and malaria control interventions [22, 25].

Malaria in Pregnancy cases were counted per diagnosis, meaning a woman could be counted more than once if she tested positive on multiple occasions during the same pregnancy. The denominator was based on the first ANC attendance per each pregnancy. All hospitals within the districts included in this study were fully reporting into DHIMS2 throughout the study period [19, 26, 27].

Consequently, no hospitals within the study districts were not reporting, and the proportion of non-reporting hospitals was zero. The district-level incidence and positivity estimates, therefore, reflect data captured from all hospitals serving pregnant women in these districts.

Quality assurance measures

Monthly reports are usually verified and audited at the health facility level before the information is entered into the DHIMS2 database. The district and regional health authorities also carry out routine data quality checks to ensure that the data in the database is of good quality.

Data cleaning

The data was cleaned by checking for completeness and consistency. We inspected and compared the DHIMS2 data with reports generated by the health facilities and submitted to the district level to ensure it was the right data. Also, the variables were rearranged into columns to help make identification and aggregation easy.

Data analysis

The data analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel 2019 and Quantum Geographic Information System (QGIS) 3.30. We used rates and frequencies to perform descriptive statistics by person, place and time. The QGIS was used to generate choropleth maps to illustrate the geographical disparities of MiP incidence in the region. The shapefiles for the maps were extracted from the DHIMS2 database. The results were presented in tables, graphs and maps.

Ethical approval

The Savannah Regional Health Directorate granted administrative permission to access the DHIMS2 database and use the dataset for the study. Ethical clearance was not sought because the data were generated and used for routine service provision. No identifiable names or addresses were used in the study. All data extracted from DHIMS2 were anonymized before analysis, with only aggregated counts presented at the district and regional levels. Individual-level identifiers such as patient names, IDs, and contact details were neither accessed nor reported, ensuring full compliance with ethical standards and safeguarding participant confidentiality. The data was securely stored on a computer with password protection, accessible only by the principal researcher.

Results

Background characteristics of reported MiP cases

Over the five years, a total of 51,479 suspected malaria in pregnancy cases were recorded, out of which 90.8% (46,734/51,479) were tested. More than half of the pregnant women were confirmed positive for malaria, 54.5% (54.0 – 54.9). The majority of malaria cases were adolescent pregnant women, 59.0% (58.0 – 60.0) (Table 1).

Incidence of MiP

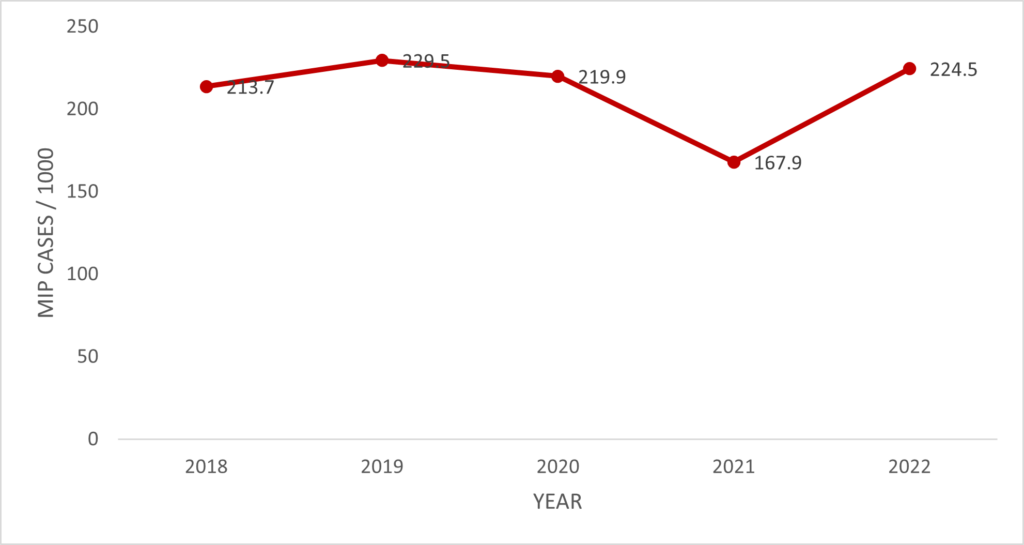

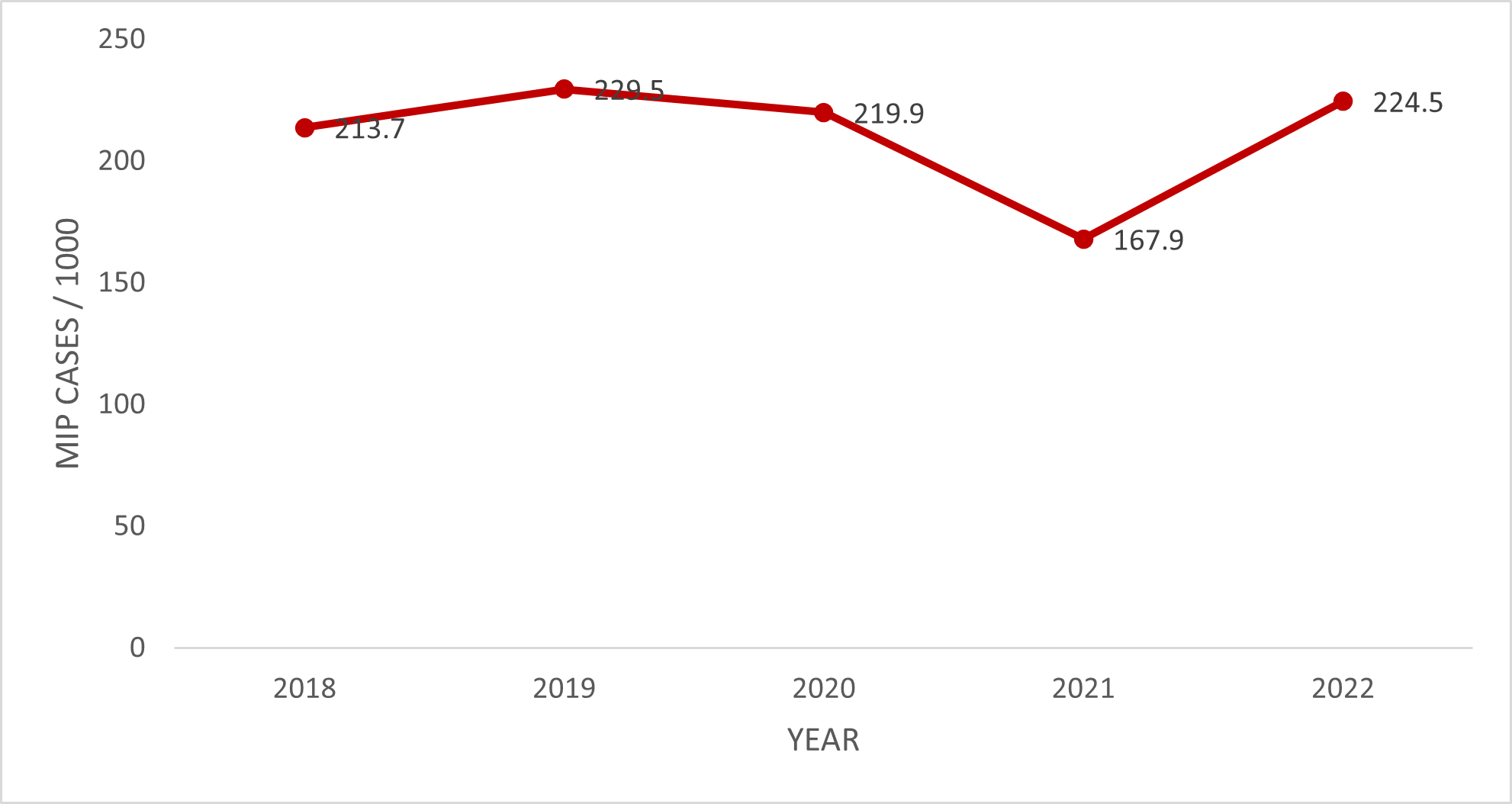

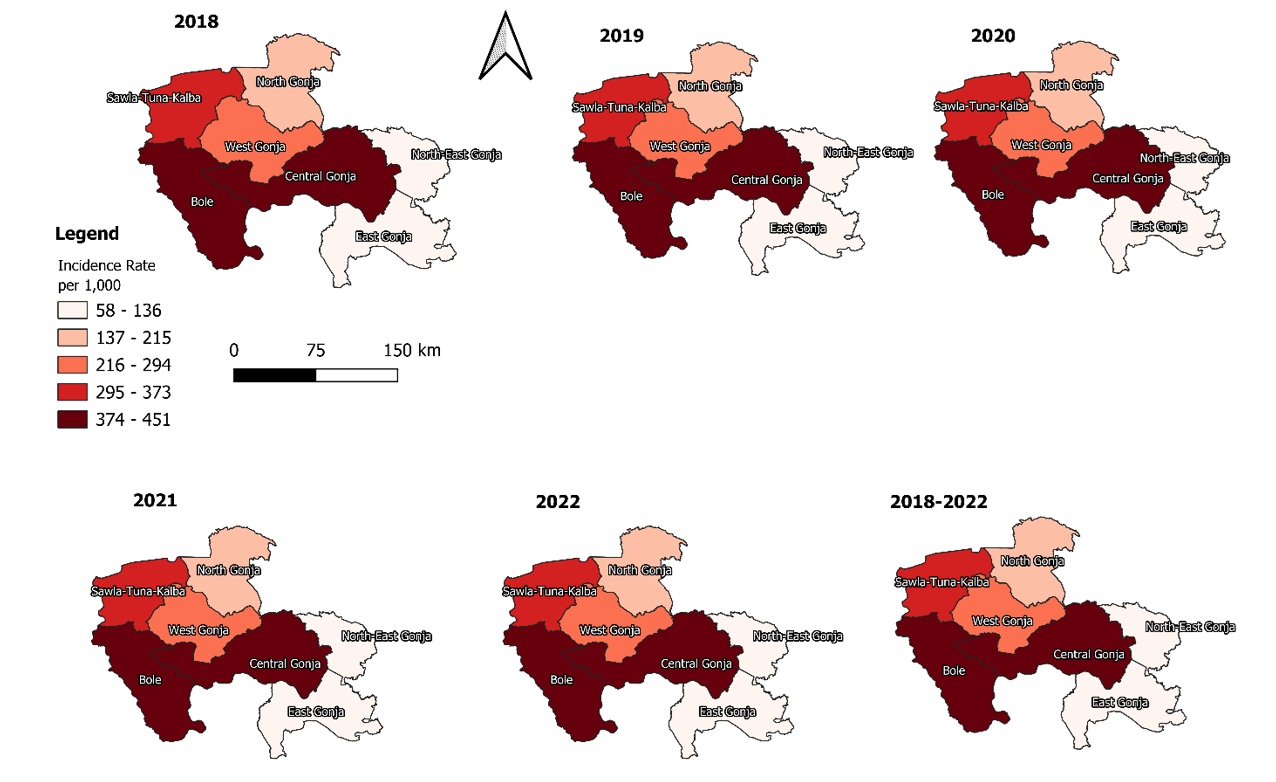

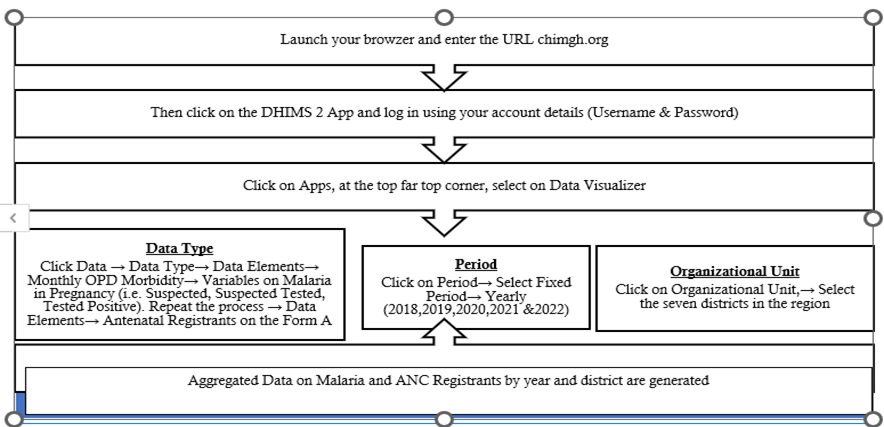

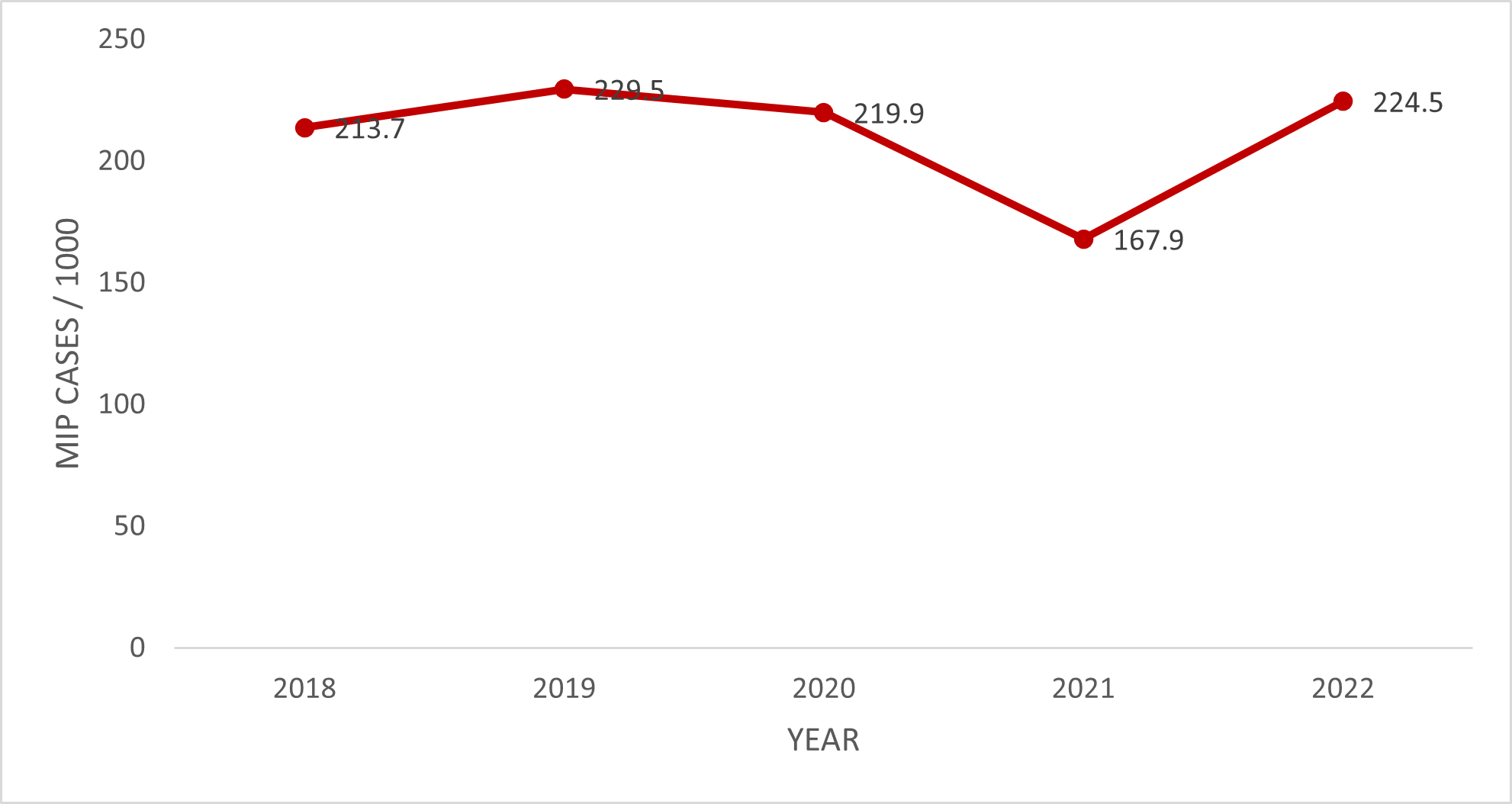

The MiP incidence rate in the Savannah Region over the 5-year study period was 210.8 (208.5 – 213.1) per 1,000. Adolescent pregnant women were more affected, 318.9 (311.9 – 326.0) per 1,000 (Table 2). The trend of the MiP incidence rate over the study period was relatively stable, with a marginal increase from 213.7 (208.3 – 217.1) per 1,000 pregnant women in 2018 to 224.5 (219.4 – 229.7) per 1,000 pregnant women in 2022. However, there was an apparent drop in 2021 from 219.9/1000 pregnant women in 2020 to 167.9/1000 pregnant women in 2021 (Figure 1). Bole District recorded the highest incidence rate, almost double that of the regional rate, 402.2 (396.2 – 408.2) per 1,000 pregnant women, while the North-East-Gonja District reported the lowest rate, 76.7 (70.6 – 83.0) per 1,000 pregnant women (Figure 2).

Discussion

The study utilized data from the DHIMS2 in the Savannah Region to describe the trend of the MiP incidence rate for 2018 – 2022. The trend in the incidence rate of MiP has been relatively stable. It only increased marginally from 213.7 cases/1,000 pregnant women to 224.5 cases/1,000 pregnant women in 2022, with an average incidence rate of 210.8 cases per 1,000 pregnant women.

There have been few studies in Ghana estimating the MiP incidence rate, making comparison difficult. According to a study conducted in the Northern Region of Ghana among pregnant women in their 3rd trimester of pregnancy in four hospitals, the MiP incidence rate was found to be 95 cases/1,000 pregnant women (9.5%) [6]. This was a prospective cohort study among pregnant women in their 3rd trimester of pregnancy and hence may not represent the true reflection of MiP incidence. Our findings, however, agreed with the malaria incidence rate in the general population conducted by USAID and CDC under the U.S President’s Malaria Initiative (Ghana Malaria Profile), which found a malaria incidence rate of 224.3 cases/1,000 population [28]. Comparing the findings of this study to findings in the neighbouring country, Burkina Faso, the MiP in Burkina Faso is not only higher but also shows an increasing trend, increasing from 310 cases/1,000 pregnant women in 2015 to 567 cases/1,000 pregnant women in 2017 [29]. The marginal increase in the MiP incidence rate in the Savanah Region over the five years raises concerns about the effectiveness of strategies used for the implementation of interventions to prevent MiP in the region, such as the use of ITNs and IPTp-SP.

From 2021 to 2022, there was a drop in the MiP incidence rate, from 219.9 cases per 1,000 pregnant women to 167.9 per 1,000 pregnant women. This drop was most likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic, possibly because pregnant women with malaria were hesitant to go to health facilities to avoid contracting COVID-19.According to a study conducted in northern Ghana, the COVID-19 pandemic also disrupted the provision of IPTp-SP to pregnant women, as well as the disruption in routine ITN distribution during ANC [30]. The limited access to IPTp-SP and ITNs due to the COVID-19 impact increased the risk of pregnant women getting malaria, coupled with pregnant women now accessing ANC services when the COVID-19 restrictions were lifted fully in 2022, which explained why the MiP incidence rate surged to 224.5 cases/1,000 pregnant women in 2022. In general, the trend of MiP in the Savannah Region was relatively stable, only increasing marginally over the study period. This does not reflect the global trend of decreasing malaria burden. In this post-COVID-19 pandemic era, all preventive measures must be scaled up in the region to mitigate the possible effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in the fight against MiP.

MiP affected all age groups. However, the incidence rate was noted to be highest among adolescent pregnant women. This finding is consistent with a study in Ghana by Osarfo and colleagues, which reported that the infection during pregnancy is high among teenage mothers and young women [12]. It further corroborates another research, which indicated that sub-Saharan African adolescent mothers are at an increased risk of clinical malaria during pregnancy as well as placental malaria compared to adult mothers [31]. This age category of pregnant women and women of primigravidae has reduced immunity against malaria, especially placental infection, and therefore suffers increased consequences of MiP, including preeclampsia [11, 32]. Dihydroartemisinin-Piperaquine use for IPTp (IPTp-DHA-PPQ) is said to lead to a lower incidence of MiP and at childbirth compared to IPTp-SP. It could be explored in this group of pregnant women [33].

Bole and Sawla-Tuna-Kalba were the only districts with MiP incidence rates above the regional average. The Bole District MiP incidence rate of 402.2 cases/1,000 pregnant women is almost double the regional MiP incidence rate of 210.8 cases/1,000 pregnant women. Principally, this alone is responsible for the high incidence of MiP in the Savannah Region. The Bole and STK districts share borders with the Ivory Coast and the Burkina Faso, respectively, and communities nearby cross these districts to access healthcare when they are unwell. These countries are noted to have a high incidence of malaria in pregnancy [29]. This could be one of the reasons for the observation in this study. The Bole District also has some ongoing illegal mining activities. The illegal mining pits, especially in the rainy seasons, could serve as breeding sites for mosquitoes. People from other districts, parts of Ghana, and even neighbouring Ivory Coast and Burkina come into the Bole District for galamsey, with resultant pregnancies being at increased risk of MiP. All the above are possible factors contributing to the high MiP incidence in the Bole District. However, factors such as errors in documentation, prescriber testing practices, and test performance, among others, could equally be responsible for the observed trend

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study provides baseline information on the burden of MiP and hypotheses for future research. Also, the study used data from DHIMS2, hence there was no potential effect of respondent and recall bias. The data used in this study were large, with all confirmed MiP cases over the study period; hence, the findings are representative of the MiP situation in the region.

This study also has some limitations, despite the strengths enumerated above. The best way to estimate the MiP incidence rate is a prospective cohort study. However, this study analyzed routine health facility data, which could underestimate the burden of MiP in the region. Additionally, due to the use of secondary data, it is not entirely possible to guarantee the quality of data reported into the database. Therefore, data capture errors might not have been sufficiently rectified. Analysis of the data could not be done at the individual woman’s level due to the aggregated nature of the DHIMS2 data.

Conclusion

The study demonstrated a high incidence of MiP in the Savannah Region, with an overall regional incidence of 210.8/1000 pregnancies. Substantial geographical disparities were observed, with the Bole district recording the highest incidence rate of 402.2/1000 pregnancies. Again, adolescent pregnancies emerged as a particularly vulnerable group, reflecting a significant burden within this population. These findings highlight the persistent public health challenge posed by MiP in the region and underscore the need for the Savannah Regional Health Directorate to engage all its stakeholders in the fight against MiP and intensify awareness and health education among pregnant women and community members on the adverse effects of MiP. Further research is needed to help determine the factors associated with MiP in high-incidence districts.

What is already known about the topic

MiP remains a major public health concern in Ghana.

Adverse maternal and child outcomes are linked to MiP.

What this study adds

- The incidence of MiP in the Savannah Region was 210.8 per 1,000

- Adolescents were most affected by MiP in the Savannah Region, 318.9 per 1,000

- This study provides information on the geographical disparities of MiP in the Savannah Region

Authors´ contributions

WJA, CK, CJAN, GA and GRI: conceptualized the study. WJA, KAS, WAA and ACB: extracted and analyzed the data. WJA and CJAN: drafted the manuscript. DAB, CK, GRI, WAA, KAS and EK: reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

| Variable | Suspected MiP | Tested MiP | Positives MiP | ANC Reg | MiP IR / 1,000 [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | |||||

| 2018 | 8,357 | 7,843 | 4,739 | 22,181 | 213.7 [208.3 – 217.1] |

| 2019 | 11,857 | 10,505 | 5,416 | 23,604 | 229.5 [224.1 – 234.9] |

| 2020 | 10,760 | 9,249 | 5,413 | 24,614 | 219.9 [214.8 – 225.1] |

| 2021 | 9,057 | 8,152 | 4,223 | 25,155 | 167.9 [163.3 – 172.6] |

| 2022 | 11,448 | 10,985 | 5,673 | 25,266 | 224.5 [219.4 – 229.7] |

| Age | |||||

| 10–19 yrs | 10,048 | 9,144 | 5,392 | 16,906 | 318.9 [311.9 – 326.0] |

| 20–34 yrs | 32,853 | 29,838 | 16,293 | 86,716 | 187.9 [185.3 – 190.5] |

| 35+ yrs | 8,578 | 7,752 | 3,779 | 17,198 | 219.7 [213.6 – 226.0] |

| District | |||||

| Bole | 16,797 | 14,723 | 10,315 | 25,646 | 402.2 [396.2 – 408.2] |

| Central Gonja | 12,144 | 11,380 | 5,104 | 27,427 | 186.1 [181.5 – 190.6] |

| East Gonja | 5,813 | 5,586 | 2,423 | 19,731 | 122.8 [118.3 – 127.5] |

| North Gonja | 2,594 | 2,228 | 1,329 | 11,353 | 117.1 [111.2 – 123.1] |

| North-East Gonja | 1,827 | 1,496 | 563 | 7,344 | 76.7 [70.6 – 83.0] |

| Sawla-Tuna-Kalba | 7,048 | 6,197 | 4,289 | 17,480 | 245.4 [239.0 – 251.8] |

| West Gonja | 5,256 | 5,124 | 1,441 | 11,839 | 121.7 [115.9 – 127.7] |

| Total | 51,479 | 46,734 | 25,464 | 120,820 | 210.8 [208.5 – 213.1] |

References

- Makoto Saito, Valérie Briand, Aung Myat Min, Rose McGready. Deleterious effects of malaria in pregnancy on the developing fetus: a review on prevention and treatment with antimalarial drugs. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health [Internet]. 2020 Oct [cited 2026 Jan 27];4(10):761–74. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2352464220300997 doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30099-7

- Line Bakken, Per Ole Iversen. The impact of malaria during pregnancy on low birth weight in East-Africa: a topical review. Malar J [Internet]. 2021 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 27];20(1):348. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-021-03883-z doi: 10.1186/s12936-021-03883-z

- Melissa Bauserman, Andrea L. Conroy, Krysten North, Jackie Patterson, Carl Bose, Steve Meshnick. An overview of malaria in pregnancy. Seminars in Perinatology [Internet]. 2019 Aug [cited 2026 Jan 27];43(5):282–90. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0146000519300436 doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2019.03.018

- Hannah Blencowe, Julia Krasevec, Mercedes De Onis, Robert E Black, Xiaoyi An, Gretchen A Stevens, Elaine Borghi, Chika Hayashi, Diana Estevez, Luca Cegolon, Suhail Shiekh, Victoria Ponce Hardy, Joy E Lawn, Simon Cousens. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of low birthweight in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. The Lancet Global Health [Internet]. 2019 Jul [cited 2026 Jan 27];7(7):e849–60. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2214109X18305655 doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30565-5

- Jamille Gregório Dombrowski, Rodrigo Medeiros De Souza, Natércia Regina Mendes Silva, André Barateiro, Sabrina Epiphanio, Lígia Antunes Gonçalves, Claudio Romero Farias Marinho. Malaria during pregnancy and newborn outcome in an unstable transmission area in Brazil: A population-based record linkage study. Georges Snounou, editor. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2018 Jun 21 [cited 2026 Jan 27];13(6):e0199415. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0199415 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199415

- Hawawu Hussein, Mansour Shamsipour, Masud Yunesian, Mohammad Sadegh Hassanvand, Percival Delali Agordoh, Mashoud Alabi Seidu, Akbar Fotouhi. Prenatal malaria exposure and risk of adverse birth outcomes: a prospective cohort study of pregnant women in the Northern Region of Ghana. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2022 Aug [cited 2026 Jan 27];12(8):e058343. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-058343 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-058343

- Joy E Lawn, Hannah Blencowe, Peter Waiswa, Agbessi Amouzou, Colin Mathers, Dan Hogan, Vicki Flenady, J Frederik Frøen, Zeshan U Qureshi, Claire Calderwood, Suhail Shiekh, Fiorella Bianchi Jassir, Danzhen You, Elizabeth M McClure, Matthews Mathai, Simon Cousens, Vicki Flenady, J Frederik Frøen, Mary V Kinney, Luc De Bernis, Joy E Lawn, Hannah Blencowe, Alexander Heazell, Susannah Hopkins Leisher, Kishwar Azad, Anisur Rahman, Shams El-Arifeen, Louise T Day, Stacy L Shah, Shafi Alam, Sonam Wangdi, Tinga Fulbert Ilboudo, Jun Zhu, Juan Liang, Yi Mu, Xiaohong Li, Nanbert Zhong, Theopisti Kyprianou, Kärt Allvee, Mika Gissler, Jennifer Zeitlin, Abdouli Bah, Lamin Jawara, Peter Waiswa, Nicholas Lack, Flor De Maria Herandez, Neena Shah More, Nirmala Nair, Prasanta Tripathy, Rajesh Kumar, Ariarathinam Newtonraj, Manmeet Kaur, Madhu Gupta, Beena Varghese, Jelena Isakova, Tambosi Phiri, Jennifer A Hall, Ala Curteanu, Dharma Manandhar, Chantal Hukkelhoven, Joyce Dijs-Elsinga, Kari Klungsøyr, Olva Poppe, Henrique Barros, Sofi Correia, Shorena Tsiklauri, Jan Cap, Zuzana Podmanicka, Katarzyna Szamotulska, Robert Pattison, Ahmed Ali Hassan, Aimable Musafi, Sanni Kujala, Anna Bergstrom, Jens Langhoff-Roos, Ellen Lundqvist, Daniel Kadobera, Anthony Costello, Tim Colbourn, Edward Fottrell, Audrey Prost, David Osrin, Carina King, Melissa Neuman, Jane Hirst, Sayed Rubayet, Lucy Smith, Bradley N Manktelow, Elizabeth S Draper. Stillbirths: rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. The Lancet [Internet]. 2016 Feb [cited 2026 Jan 27];387(10018):587–603. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673615008375 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00837-5

- Stephen J Rogerson, Meghna Desai, Alfredo Mayor, Elisa Sicuri, Steve M Taylor, Anna M Van Eijk. Burden, pathology, and costs of malaria in pregnancy: new developments for an old problem. The Lancet Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2018 Apr [cited 2026 Jan 27];18(4):e107–18. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1473309918300665 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30066-5

- WHO. WHO Malaria Policy Advisory Group (MPAG) meeting, October 2022 [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2022 Oct [cited 2025 Apr 02]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240063303

- The Commonwealth. The Commonwealth Malaria Report 2022 [Internet]. New York (NY): Reliefweb; 2022 May 19 [cited 2026 Jan 27] [about 6 screens]. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/commonwealth-malaria-report-2022

- Gifty Dufie Ampofo, Joseph Osarfo, Matilda Aberese-Ako, Livingstone Asem, Mildred Naa Komey, Wahjib Mohammed, Anthony Adofo Ofosu, Harry Tagbor. Malaria in pregnancy control and pregnancy outcomes: a decade’s overview using Ghana’s DHIMS II data. Malar J [Internet]. 2022 Oct 27 [cited 2026 Jan 27];21(1):303. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-022-04331-2 doi: 10.1186/s12936-022-04331-2

- Joseph Osarfo, Gifty Dufie Ampofo, Harry Tagbor. Trends of malaria infection in pregnancy in Ghana over the past two decades: a review. Malar J [Internet]. 2022 Jan 4 [cited 2026 Jan 27];21(1):3. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-021-04031-3 doi: 10.1186/s12936-021-04031-3

- Jessica Ashiakie Tetteh, Patrick Elorm Djissem, Alfred Kwesi Manyeh. Prevalence, trends and associated factors of malaria in the Shai-Osudoku District Hospital, Ghana. Malar J [Internet]. 2023 Apr 22 [cited 2026 Jan 27];22(1):131. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-023-04561-y doi: 10.1186/s12936-023-04561-y

- David Kwame Dosoo, Daniel Chandramohan, Dorcas Atibilla, Felix Boakye Oppong, Love Ankrah, Kingsley Kayan, Veronica Agyemang, Dennis Adu-Gyasi, Mieks Twumasi, Seeba Amenga-Etego, Jane Bruce, Kwaku Poku Asante, Brian Greenwood, Seth Owusu-Agyei. Epidemiology of malaria among pregnant women during their first antenatal clinic visit in the middle belt of Ghana: a cross sectional study. Malar J [Internet]. 2020 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 27];19(1):381. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-020-03457-5 doi: 10.1186/s12936-020-03457-5

- Nsoh Godwin Anabire, Paul Armah Aryee, Abass Abdul-Karim, Issah Bakari Abdulai, Osbourne Quaye, Gordon Akanzuwine Awandare, Gideon Kofi Helegbe. Prevalence of malaria and hepatitis B among pregnant women in Northern Ghana: Comparing RDTs with PCR. Isabelle Chemin, editor. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2019 Feb 6 [cited 2026 Jan 27];14(2):e0210365. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210365 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210365

- Robert Yankson, Evelyn Arthur Anto, Michael Give Chipeta. Geostatistical analysis and mapping of malaria risk in children under 5 using point-referenced prevalence data in Ghana. Malar J [Internet]. 2019 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 27];18(1):67. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-019-2709-y doi: 10.1186/s12936-019-2709-y

- Komlagan Mawuli Apélété Yao, Francis Obeng, Joshua Ntajal, Agbeko K. Tounou, Brama Kone. Vulnerability of farming communities to malaria in the Bole district, Ghana. Parasite Epidemiology and Control [Internet]. 2018 Nov [cited 2026 Jan 27];3(4):e00073. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2405673118300102 doi: 10.1016/j.parepi.2018.e00073

- Ghana Statistical Service (GSS). Population Projection 2021–2050 [Internet]. Accra (Ghana): Ghana 2021 Population and Housing Census; 2024 Jun [cited 2026 Jan 27]. Available from: https://statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/fileUpload/pressrelease/Population_projection_280624_final_ffa2[1][2]_with_links[_final_website.pdf

- Ghana Health Service (GHS), Savannah Regional Health Directorate. 2022 Annual Performance Report. Accra (Ghana): GHS; 2017.

- Isha Berry, Patrick Walker, Harry Tagbor, Kalifa Bojang, Sheick Oumar Coulibaly, Kassoum Kayentao, John Williams, Abraham Oduro, Paul Milligan, Daniel Chandramohan, Brian Greenwood, Matthew Cairns. Seasonal Dynamics of Malaria in Pregnancy in West Africa: Evidence for Carriage of Infections Acquired Before Pregnancy Until First Contact with Antenatal Care. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene [Internet]. 2018 Feb 7 [cited 2026 Jan 27];98(2):534–42. Available from: https://www.ajtmh.org/view/journals/tpmd/98/2/article-p534.xml doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0620

- World Health Organization (WHO). Primary health care systems (PRIMASYS): case study from Mexico [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2017 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 27]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/1d7b94c0-bc8a-4b38-9073-d8b51b4f1b53/content

- WHO. Adolescent pregnancy (Fact sheet) [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2024 Apr 10 [cited 2026 Jan 04]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy

- Louise C. Kenny, Tina Lavender, Roseanne McNamee, Sinéad M. O’Neill, Tracey Mills, Ali S. Khashan. Advanced Maternal Age and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome: Evidence from a Large Contemporary Cohort. Qinghua Shi, editor. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2013 Feb 20 [cited 2026 Jan 27];8(2):e56583. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056583 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056583

- T Ganchimeg, E Ota, N Morisaki, M Laopaiboon, P Lumbiganon, J Zhang, B Yamdamsuren, M Temmerman, L Say, Ö Tunçalp, J P Vogel, J P Souza, R Mori, on behalf of the WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal Newborn Health Research Network. Pregnancy and childbirth outcomes among adolescent mothers: a World Health Organization multicountry study. BJOG [Internet]. 2014 Mar [cited 2026 Jan 27];121(s1):40–8. Available from: https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.12630 doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12630

- Julianna Schantz-Dunn, Nawal M Nour. Malaria and Pregnancy: A Global Health Perspective. Rev Obstet Gynecol [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2026 Jan 27];2(3):186–92. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2760896/

- Mary Amoakoh-Coleman, Gbenga A Kayode, Charles Brown-Davies, Irene Akua Agyepong, Diederick E Grobbee, Kerstin Klipstein-Grobusch, Evelyn K Ansah. Completeness and accuracy of data transfer of routine maternal health services data in the greater Accra region. BMC Res Notes [Internet]. 2015 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 27];8(1):114. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1756-0500/8/114 doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1058-3

- L Obed Uwumbornyi Lasim, Edward Wilson Ansah, Daniel Apaak. Maternal and child health data quality in health care facilities at the Cape Coast Metropolis, Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2022 Aug 30 [cited 2026 Jan 27];22(1):1102. Available from: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-022-08449-6 doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08449-6

- CDC. World Malaria Day 2022: Country-to-country collaboration for antimalarial resistance monitoring [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; 2022 Apr 29 [cited 2026 Jan 27]. Available from: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/121214

- Noussaint Rouamba, Sekou Samadoulougou, Halidou Tinto, Victor A. Alegana, Fati Kirakoya‑Samadoulougou. Severe-malaria infection and its outcomes among pregnant women in Burkina Faso health-districts: Hierarchical Bayesian space-time models applied to routinely-collected data from 2013 to 2018. Spatial and Spatio-temporal Epidemiology [Internet]. 2020 Jun [cited 2026 Jan 27];33:100333. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1877584520300113 doi: 10.1016/j.sste.2020.100333

- Anna-Katharina Heuschen, Alhassan Abdul-Mumin, Martin Nyaaba Adokiya, Guangyu Lu, Albrecht Jahn, Oliver Razum, Volker Winkler, Olaf Müller. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the malaria burden in northern Ghana: Analysis of routine surveillance data [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2026 Jan 27]. Available from: http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2021.11.29.21266976 doi: 10.1101/2021.11.29.21266976

- Clara Pons-Duran, Ghyslain Mombo-Ngoma, Eusebio Macete, Meghna Desai, Mwaka A. Kakolwa, Rella Zoleko-Manego, Smaïla Ouédragou, Valérie Briand, Anifa Valá, Abdunoor M. Kabanywanyi, Peter Ouma, Achille Massougbodji, Esperança Sevene, Michel Cot, John J. Aponte, Alfredo Mayor, Laurence Slutsker, Michael Ramharter, Clara Menéndez, Raquel González. Burden of malaria in pregnancy among adolescent girls compared to adult women in 5 sub-Saharan African countries: A secondary individual participant data meta-analysis of 2 clinical trials. Lorenz Von Seidlein, editor. PLoS Med [Internet]. 2022 Sep 2 [cited 2026 Jan 27];19(9):e1004084. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004084 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1004084

- Dorotheah Obiri, Isaac Joe Erskine, Daniel Oduro, Kwadwo Asamoah Kusi, Jones Amponsah, Ben Adu Gyan, Kwame Adu-Bonsaffoh, Michael Fokuo Ofori. Histopathological lesions and exposure to Plasmodium falciparum infections in the placenta increases the risk of preeclampsia among pregnant women. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2020 May 19 [cited 2026 Jan 27];10(1):8280. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-64736-4 doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-64736-4

- Meghna Desai, Julie Gutman, Anne L’lanziva, Kephas Otieno, Elizabeth Juma, Simon Kariuki, Peter Ouma, Vincent Were, Kayla Laserson, Abraham Katana, John Williamson, Feiko O Ter Kuile. Intermittent screening and treatment or intermittent preventive treatment with dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine versus intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine for the control of malaria during pregnancy in western Kenya: an open-label, three-group, randomised controlled superiority trial. The Lancet [Internet]. 2015 Dec [cited 2026 Jan 27];386(10012):2507–19. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673615003104 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00310-4