Research | Open Access | Volume 9 (1): Article 29 | Published: 17 Feb 2026

Improving access to oncogenic human papillomavirus testing among high-risk populations using a centralised sample referral strategy in Kenya: Findings and recommendations

Menu, Tables and Figures

Navigate this article

Tables

| Participating institutions | Participating facility | County | Target population (30–49 years) | Coverage | HPV Positivity | VIA triage | VIA positive | Treated | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. tested | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| SWOP | SWOP City | Nairobi | 1794 | 817 | 45.5 | 195 | 23.9 | 155 | 79.5 | 22 | 14.2 | 22 | 100.0 |

| SWOP Kawangware | Nairobi | 927 | 461 | 49.7 | 93 | 20.2 | 93 | 100.0 | 6 | 6.5 | 6 | 100.0 | |

| SWOP Langata | Nairobi | 1100 | 487 | 44.3 | 106 | 21.8 | 88 | 83.0 | 24 | 27.3 | 24 | 100.0 | |

| SWOP Thika Road | Nairobi | 1414 | 770 | 54.5 | 167 | 21.7 | 111 | 66.5 | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 100.0 | |

| SWOP Donholm | Nairobi | 877 | 705 | 80.4 | 142 | 20.1 | 97 | 68.3 | 44 | 45.4 | 44 | 100.0 | |

| SWOP Kariobangi | Nairobi | 1528 | 701 | 45.9 | 157 | 22.4 | 114 | 72.6 | 30 | 26.3 | 30 | 100.0 | |

| SWOP Majengo | Nairobi | 1408 | 461 | 32.7 | 157 | 34.1 | 50 | 31.8 | 8 | 16.0 | 8 | 100.0 | |

| COEHM | Pumwani Maternity Hospital | Nairobi | 1395 | 1041 | 74.6 | 84 | 8.1 | 76 | 90.5 | 41 | 53.9 | 40 | 97.6 |

| Kenyatta National Hospital | Nairobi | 3510 | 1547 | 44.1 | 368 | 23.8 | 226 | 61.4 | 41 | 18.1 | 18 | 43.9 | |

| Thika Level 5 | Kiambu | 1680 | 1690 | 100.6 | 223 | 13.2 | 223 | 100.0 | 21 | 9.4 | 21 | 100.0 | |

| Kiambu Level 5 | Kiambu | 1347 | 716 | 53.2 | 79 | 11.0 | 79 | 100.0 | 13 | 16.5 | 9 | 69.2 | |

| Wangige Level 4 | Kiambu | 435 | 391 | 89.9 | 62 | 15.9 | 8 | 12.9 | 2 | 25.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Tigoni Level 4 | Kiambu | 435 | 313 | 72.0 | 21 | 6.7 | 10 | 47.6 | 8 | 80.0 | 5 | 62.5 | |

| Igegania Level 4 | Kiambu | 315 | 309 | 98.1 | 29 | 9.4 | 29 | 100.0 | 8 | 27.6 | 8 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 18165 | 10409 | 57.3 | 1883 | 18.1 | 1359 | 72.2 | 269 | 19.8 | 236 | 87.7 | ||

SWOP: Sex Workers Outreach Program; COEHM: University of Nairobi’s Centre of Excellence in HIV Medicine; HPV: Human papillomavirus; VIA: Visual inspection with acetic acid

Table 2: HPV sample testing turn-around times, HPV sample referral pilot, Kenya, 2021–2022

| Time period | Mean turn-around times (TAT), in days | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| KEMRI laboratory | NCRL | ||

| Sample collection to reception at the laboratory | 12.1 (9.3) | 8.1 (26.8) | <0.001 |

| Sample reception to testing | 15.8 (14.0) | 2.1 (3.8) | <0.001 |

| Sample testing to transmission of results | 0.4 (0.7) | 23.9 (29.6) | <0.001 |

| Total TAT | 28.3 (16.1) | 33.8 (28.2) | <0.001 |

TAT: Turnaround time; NCRL: National Cancer Reference Laboratory;

KEMRI: Kenya Medical Research Institute.

Table 3: Demographic characteristics among screened women with all variables reported on the health information system, sample referral pilot, 2021–2022 (n=3,123)

| Variable | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| <25 | 82 | 2.6 |

| 25–49 | 2,717 | 87.0 |

| 50+ | 324 | 10.4 |

| HIV status | ||

| Positive | 1,280 | 50.0 |

| Negative | 1,091 | 34.9 |

| Unknown | 752 | 24.1 |

| Type of screening visit | ||

| Initial | 2,066 | 66.2 |

| Routine | 673 | 21.5 |

| Post-treatment screening | 11 | 0.4 |

| Unknown | 373 | 11.9 |

| Method of sample collection | ||

| Self-collection | 486 | 15.6 |

| Clinician collected | 2,637 | 84.4 |

Table 4: Comparison between clinician and self-collected HPV samples, Kenya sample referral pilot, 2021–2022

| Variable | Sample collection method | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinician (N=2,637) n (%) | Self (N=486) n (%) | ||

| HPV positivity | |||

| Positive | 642 (24.3) | 101 (20.8) | 0.090 |

| Negative | 1,995 (75.7) | 385 (79.2) | |

| Sample validity | |||

| Invalid | 74 (2.8) | 14 (2.9) | 0.927 |

| Valid | 2,563 (97.2) | 472 (97.1) | |

| Laboratory results status | |||

| Unknown | 3 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.457 |

| Known | 2,634 (99.9) | 486 (100.0) | |

Figures

Keywords

- Cervical cancer elimination

- Sample referral

- VIA triaging

- Key populations

- Self-sample collection

- Health worker sample collection

Valerian Mwenda1,&, David Murage1, Joan-Paula Bor1, Lance Osiro2, Sharon Olwande2, James Njeru2, Patricia Njiri2, Mary Nyangasi1

1National Cancer Control Program, Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya, 2Clinton Health Access Initiative, Nairobi, Kenya

&Corresponding author: Valerian Mwenda, National Cancer Control Program, Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya. Email: valmwenda@gmail.com, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1956-7440

Received: 10 Feb 2025, Accepted: 11 Feb 2026, Published: 17 Feb 2026

Domain: Cancer Epidemiology

Keywords: Cervical cancer elimination, sample referral, VIA triaging, key populations, self-sample collection, health worker sample collection

©Valerian Mwenda et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Valerian Mwenda et al., Improving access to oncogenic human papillomavirus testing among high-risk populations using a centralised sample referral strategy in Kenya: Findings and recommendations. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2026; 9(1):29. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00042

Abstract

Introduction: Even though national guidelines recommend human papillomavirus (HPV) testing as the primary cervical cancer (CxCa) screening modality in Kenya, the test is not widely available. We present findings from a pilot study that assessed the feasibility of sample referral to national laboratories for HPV testing among high-risk populations in Kenya.

Methods: We implemented the pilot in Nairobi and Kiambu counties, during 05/2021–03/2022. Both self and clinician-sample collection approaches were deployed. Samples were tested at the National Cancer Reference Laboratory (NCRL) and the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI). Positive HPV cases were triaged with visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA), and pre-cancerous lesions (PCL) were treated with thermal ablation, cryotherapy, or large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ). We calculated screening coverage, HPV positivity, triage, and treatment rates, turnaround times (TAT) and compared the quality of clinician and self-collected samples.

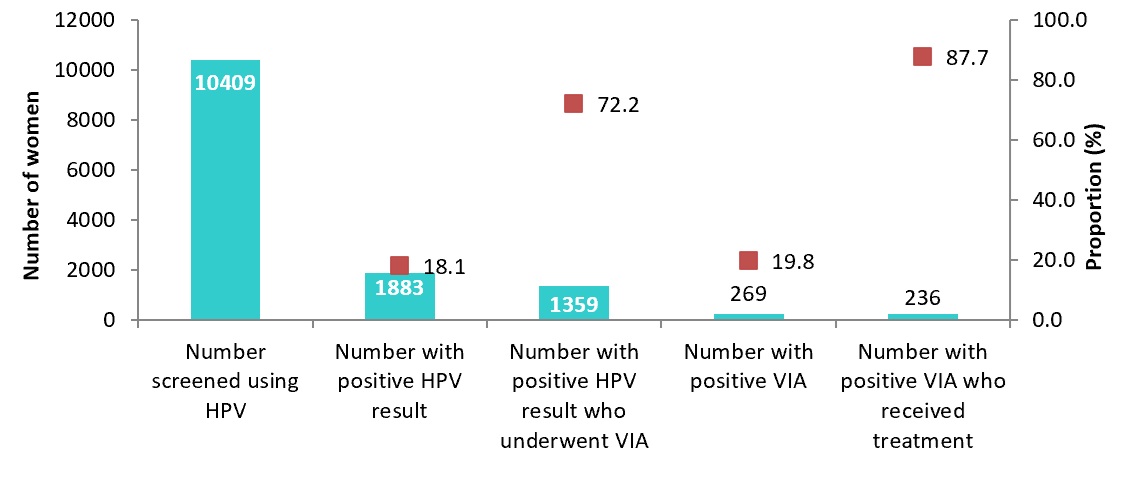

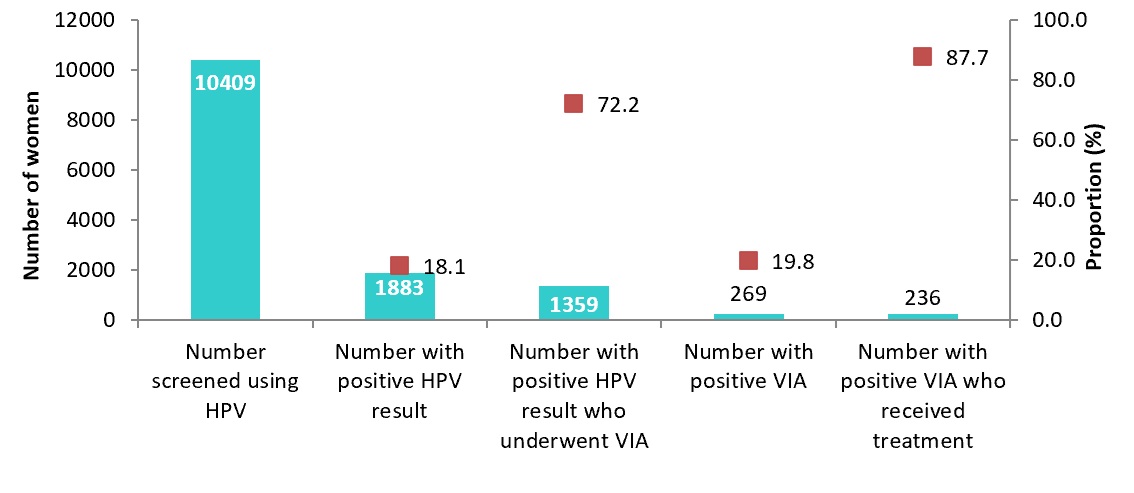

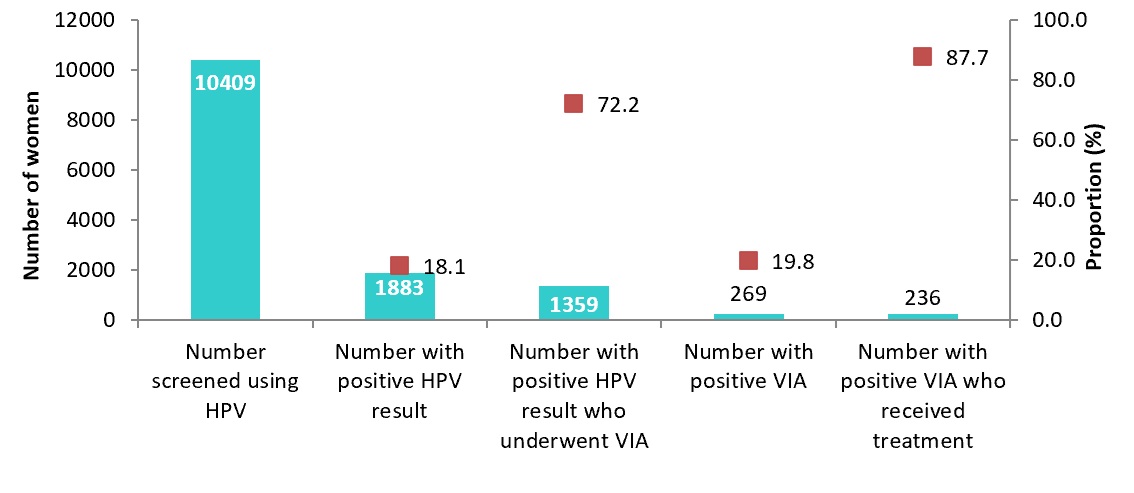

Results: Screening coverage was 57.3% (10,409/18,165), and the overall HPV positivity rate was 18.1% (1,883/10,409). VIA triaging rate was 72% (1,359/1,883) and 88% (236/269) of VIA-positive cases received treatment. Only 30% (3,123/10,409) of screened women had all key variables recorded in the health information system; mean age 39.0 (Standard deviation[SD]± 8.1) years, 50.0% (1,280) were from women living with HIV (WLHIV), 24.1% (752) were of unknown HIV status. Sixteen per cent (486/3,123) had self-collected samples, while the rest (84%) had clinician-collected samples. Self-collection was preferred by 3.6% (46/1,280) of WLHIV, and 23.9% (439/1,839) of women with negative/unknown HIV status (p<0.001). HPV positivity was 28.3% (362/1,280) among HIV positive women and 22.6% (416/1,839) among those with negative/unknown HIV status (p<0.001). The HPV positivity rate was 24.3% (642/2,637) among the clinician-collected samples and 20.8% (101/486) from the self-collected samples (p =0.090). Invalid sample rate was 2.8% (74/2,637) among clinician-collected samples and 2.9% (14/486) among self-collected samples (p =0.927). Average TAT to screening clinic receipt of results was 28.3 (±16.1) days at the KEMRI laboratory and 33.8 (±28.2) days at the NCRL (p<0.001).

Conclusion: Self-sample collection can supplement collection by health workers as HPV testing is expanded. Interventions to reduce the TAT would be warranted before a sample referral approach is deployed at scale in Kenya.

Introduction

In 2020, cervical cancer (CxCa) caused over 600,000 cases and 340,000 deaths globally [1]. One quarter of these deaths occurred in Africa [2]. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination, cost-efficient screening methods, and the treatment of precancerous lesions and early-stage cancer are successful strategies for CxCa [3]. Accordingly, in 2020 the World Health Organization (WHO) launched a call to eliminate cervical cancer [4]. The global strategy to accelerate the elimination of CxCa as a public health problem within a century identifies critical actions and targets to be achieved by 2030, which include screening using a high-precision test (HPV testing) and linkage to treatment.

CxCa screening in Africa ranged from 10–14% for women 30–49 years in the preceding five years [5]. Since HPV vaccination in most African countries is also low, the burden of cervical cancer in the continent has been noted to be rising as it falls in other parts of the world [6]. In 2021, WHO released updated guidance recommending HPV testing as the primary screening technology for secondary prevention; however, adoption of HPV testing for CxCa population-level screening programs in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has been slow [5]. Implementation of CxCa screening programmes in SSA has been hampered by organisational, financial, logistical, and socio-cultural issues [7–11].

About 3,200 women die from cervical cancer each year in Kenya, making it the leading cause of cancer mortality for females [12]. Despite the fact that 75% of eligible women are aware of the need for regular cervical cancer screening, the screening coverage from a nationally representative survey conducted in 2016 was 16% [13]. Several reasons have been fronted to explain the low uptake. First, socio-cultural attributes, especially stigma and embarrassment about the screening procedure [14, 15], as well as culturally informed communication. Second, health system challenges, including limited access to healthcare facilities that offer screening services, high costs of screening, a lack of commodities and supplies, insufficient and inadequately trained personnel and lengthy wait times; only a quarter of health facilities were offering cervical cancer screening in 2018 [16, 17].

The National Cancer Screening Guidelines 2018 recommend programmatic screening for all women 25–49 years of age, with HPV DNA testing as the preferred method for women above 30 years [18]. However, being a new screening method, the test is not widely available in public facilities in Kenya, and VIA is the method of choice in more than 90% of screening facilities. To implement HPV testing as both a policy imperative in Kenya as well as respond to the global cervical CxCa elimination call, the Kenya Ministry of Health has been exploring strategies for rolling out HPV testing at the population level countrywide. A previous pilot study explored utilization of GeneXpert platforms used for TB and HIV diagnosis at county and sub-county hospitals [19]. Another proposed strategy is to have sample collection done at the primary care level and testing occurring at the national central specialised laboratories. A pilot to explore this strategy was conducted in 2021–2022. The main objective of the pilot study was to assess the feasibility and efficiency of centralised HPV testing approach, from sample collection to results generation, transmission, and linkage to further evaluation and/or treatment within an integrated service delivery model of care in the comprehensive care clinic. We present the process, findings, and recommendations from the implementation of the HPV sample referral pilot, conducted among high-risk populations in two Kenyan counties.

Methods

Pilot setting and population

The pilot was implemented in two counties: Nairobi and Kiambu, for eleven months from May 2021 to March 2022. Nairobi, the capital city county, is a densely populated urban setting with an estimated population of 4.5 million in 2020 [20]. Kiambu is also classified as an urban county, with an estimated population of 2.5 million in 2020 [20]. The two counties have a combined population of women aged 30–49 years of 930,618. The HIV prevalence in Nairobi is 3.8%, while in Kiambu it is 1.1%, but higher in women [21].

The Project target population was women 30–49 years of age from select high-risk populations (living with or at high risk of HIV infection) drawn from facilities supported by the Sex Workers Outreach Program (SWOP) and University of Nairobi’s Centre of Excellence in HIV Medicine (COEHM) and Central Kenya Response – Integration, Strengthening and Sustainability plus Project (CRISS+ Project). SWOP is a leading sex workers health agency in Kenya that promotes the health, safety & well-being of sex workers. COEHM was a five-year project (October 2016–September 2021) supporting Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH), Pumwani Maternity Hospital (PMH), Centre for Respiratory Disease Research-Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI-CRDR) and Kenya Aids Vaccine Initiative (KAVI) to enhance their capacity to provide high-quality HIV prevention and treatment. The CRISS+ Project was a 5-year (2017–2022) PEPFAR-funded HIV prevention, care & treatment project in partnership with the Kiambu County Health Department. Implementation among key populations was informed by the need for rapid scale-up of testing among such groups, as well as integration of sample referral within existing pathways for HIV care and treatment.

Facility selection was based on capacity for testing, the need for HPV screening in a high-risk key population as per the National Screening Guidelines (Women Living with HIV) and availability of cryotherapy/ thermal ablation and large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ) on site or clear referral pathways for the same. The combined target population for the pilot sites was 18,165; this represents the population of HIV positive/key population women 30–49 years targeted for screening by the two collaborating implementing institutions. Samples were referred for testing at two national conventional laboratories: the National Cancer Reference Laboratory (NCRL) and the Kenya Medical Research Institute laboratory (KEMRI), both based in Nairobi (all testing and screening health facilities were within 30 kilometres from the testing laboratories).

Pilot implementation processes

Operational aspects of the strategy to be evaluated included the entire process of sample transmission to the NCRL/KEMRI, relaying of results to the health facilities on the Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) platform, transmission of results to screened women, and eventual linkage of positive cases to triage and treatment at the health facilities. We deployed two sample collection approaches: facility-based sampling (either health worker collected or self-collected) and a community-based self-sampling arm with the engagement of community health strategy structures. We leveraged the existing sample referral networks as established by the HIV and TB programs for referral of samples to the two laboratories.

HPV Testing

A training package targeting the joint teams from the selected facilities including clinical teams (nurses, clinical officers, medical officers and laboratory technicians), health records officers and the team leads was implemented, with the following thematic areas: strategic overview of CxCa and HPV testing in Kenya, introduction to CxCa screening, HPV self-sampling approach, laboratory processes, communication, demand generation and data collection and reporting; in total 95 facility healthcare workers were trained. In addition, 55 Community Health Volunteers (CHVs)/ peer educators and 27 Community Health Extension Workers (CHEWs) were also trained to support the self-sampling component across all the sites. The CHVs were supervised by the trained CHEWs, who were in turn supervised by the trained facility staff.

Reports (timesheets) outlining their performance, tracking commodities, and sharing challenges were shared with the pilot secretariat at the NCCP on a monthly basis. The pilot utilized sample collection kits from Lasec®, and samples were transported in PreservCyt® solution. Sample testing was integrated into the existing platforms (Cobas® 4800 system at NCRL and Abbot® M2000 in KEMRI). Cobas has a sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 95%, for Abbott, it is 96% and 92%, respectively [22, 23]. The two are included in the WHO prequalification list for HPV testing assays [24]. Both assays can detect 14 high-risk HPV types, in addition to specific genotyping information for types 16 and 18.

Data collection

To answer the pilot objectives, we tracked screening coverage, HPV test positivity, pre-cancer detection rate/triage positivity rate, treatment rate and screening turnaround times (referral, testing and results communication). Screening coverage was calculated as the number of women who underwent HPV testing at the end of the pilot period, as a proportion of the target established before the pilot. HPV test positivity was the proportion of tested women with results of one of the high-risk HPV types. The triaging rate was the proportion of women with high-risk HPV who underwent VIA. Pre-cancer detection rate was the proportion of women with abnormal VIA triaging results, out of those with high-risk HPV infection. Treatment rate was the proportion of women who were had documented evidence of receiving treatment, out of those with abnormal VIA results. Testing TAT was the time period from reception of samples at the laboratory to the transmission of results to the health facilities. Invalid HPV result meant the sample did not have adequate material or that the assay was not satisfactory.

Communication of results from the testing laboratories to the facilities was done either through facility emails or through the existing Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS), which had been updated to include HPV tests on its dashboard. Data collection was based on the existing cancer screening surveillance systems, combining physical registers and a laboratory information management system (LIMS), with the screening information transmitted to the Kenya Health Information System (KHIS).

Data management

Data on key variables including age, HIV status, sample collection site, sample collection approach, screening pathway (number of women screened, testing positive, triaged and treated) and turn-around time was extracted from the KHIS and LMIS into excel spreadsheets for cleaning and organization. We conducted descriptive statistics and used a two-sided chi-square to compare testing parameters between self and health worker collected samples as well as TAT between the two laboratories, with an alpha value of 0.05 used as the threshold for statistical significance. Data analysis was conducted using R software.

Ethical considerations

This pilot was implemented as a programmatic intervention by the Ministry of Health, based on documented policy directives. Therefore, Institutional Review Board evaluation was not necessary. Data collection was based on established public health surveillance structures for cervical cancer screening. Even in this context, data derived from the project was kept confidential and secured, in line with the Kenya Data Protection Regulations, 2021 [25].

Results

Screening statistics

A total of 10,409 women were recorded to have been screened at the participating facilities during the 11-month period, with 2,517 (24.2%) being in the community-based self-testing arm. However, we noted significant data loss as only 3,123 (30.0%) had complete screening information captured on the health information system using the cervical cancer screening tools. It was noted that most facilities did not update the details of the clients who did self-sampling in the community into their screening registers and KHIS. The overall target population coverage was 57.3%. However, a wide inter-site variability was noted, with a coverage range of between 33-100%. The overall HPV positivity rate was at 18.1%, with a range of 7-34% across the various centres. Table 1 shows the distribution of the HPV testing, triage and treatment cascade across all the participating sites.

Screening-care linkage cascade

Out of all the screen-positive clients, 72% underwent VIA testing for triaging; 20% of these had VIA-positive results (Figure 1). Approximately 88% of VIA-positive clients received treatment for pre-cancer lesions, using cryotherapy or thermal ablation.

Turn-around times

The average TAT for receipt of patient results was 28 days for the KEMRI laboratory and 34 days for the NCRL. KEMRI laboratory had shorter sample testing TAT, while the NCRL had shorter sample transmission and testing TATs (Table 2).

Demographic characteristics of screened women with all key variables

Among the 3,123 women with all core screening variables documented, the mean age was 39.0 years (S.D 8.1); 87.0% were within the target population of 25–49 years. Half were HIV positive, 66% were attending screening for the first time and 84% had their samples collected by a clinician (table 3). Uptake of self-sample collection was significantly higher among women with negative or unknown HIV status compared with HIV positive women (23.9% [439/1,839] vs. 3.6% [46/1,280], p<.001).

Comparison between clinician and self-collected samples

We found no significant differences in HPV positivity (24.3% vs. 20.8%, p=0.090), invalid sample rates (2.8% vs. 2.9%, p=0.927), or unknown sample status rates (0.1% vs. 0.0%, p=0.457) between clinician and self-collected samples (Table 4).

Discussion

The pilot was able to reach approximately half of the targeted population. There was significant data loss that was demonstrated during this pilot where a large number of the screening results were not uploaded into the Kenya Health Information System (KHIS). This could be explained by the fact that the health workers working within the comprehensive clinics for HIV care and treatment (CCCs) were not familiar with the cervical cancer data tools, as well as the fact that the two national referral laboratories did not also report to the KHIS. We found a wide range of HPV positivity across the testing sites, with an overall rate of 18%. Triage and treatment coverage was above 75%. The average TAT for HPV screening was approximately 30 days.

Approximately 57% of the target population was reached with HPV testing. While this is higher than the national screening average in 2022/2023, it is still below the desired coverage target by 2030 [4, 13]. Coverage could have been limited by demand barriers, but the HPV test kits’ supply chain challenges were also encountered during implementation.

The community strategy was an important facet of the implementation of the pilot, either as a mobilization tool or supporting the self-sampling component. Self-sample collection is one of the positive attributes of HPV testing for CxCa screening, since it can be conducted on a vaginal sample. Self-sample collection has been shown to increase CxCa screening uptake and is now recommended by the WHO [26, 27]. Women living with HIV (WLHIV) had a lower preference for self-sample collection compared with women HIV negative/unknown status. This could be due to the trust that WLHIV have built with their healthcare providers over the years of follow-up; a similar preference has been shown among high-risk population in a study conducted at the coastal region of Kenya [28]. Therefore, both sample collection strategies are complementary and may need to be implemented together. We did not find any differences between self-collected and clinician-collected samples in terms of sample quality or HPV positivity rates.

The overall high-risk HPV positivity rate was 18%, which was within the target range set by the WHO for monitoring HPV-based cervical cancer screening programs (5-25%) [29]. This is comparable with other studies from SSA [30–33]. Majority of clients at most of the facilities were successfully linked to treatment. However, despite efforts to track screen-positive clients, 25% of the eligible women did not come back for VIA triage. This could have been due to delays in results transmission to health facilities and subsequent tracking of the women. This finding is comparable with a study in Uganda, which found a triage compliance of 74% [34]. Interestingly, the health facilities had varying experiences with VIA linkage, with SWOP Majengo, Wangige Level 4 and Tigoni Level 4 having poor rates. This is despite similar pre-pilot interventions in training and mentorship; a possible reason could be differences in VIA supplies between the health facilities. Triage compliance could also be influenced by the reception of results by HPV positive women; an analysis of implementation studies from SSA by Jessica and colleagues found that approximately 72% had received their results [35]. Adequate follow-up and tracking of screen-positive women requires a functional health information system; electronic health records are one approach [36]. Of all the VIA-positive cases, 88% underwent treatment for precancer lesions. A comparable screening program implemented in Nicaragua had a triage rate of 54% and a treatment of triage-positive rate of 53.1% [37]. One reason for higher rates in our study could be due to robust follow-up mechanisms under the established framework under COEHM and SWOP. We found low treatment rates for the KNH site; the reason is that lower cadres like nurses are not authorized to conduct pre-cancer treatment at the referral hospital; therefore, women may fail to honour referrals to the gynaecological clinics. The study by Jessica et al showed a treatment of 87% among those eligible [35].

On average, it took a month for HPV testing to be transmitted to the respective testing sites. The KEMRI laboratory had long TAT for sample reception to testing, likely due to high workloads and backlogs at the testing lab. On average, the KEMRI laboratory processes over 50,000 HIV viral load and 20,000 early infant diagnosis samples every month. The NCRL, by contrast, took the longest to transmit results after samples were tested (24 days vs. less than 1 day for KEMRI). This could likely be due to human resource limitations and/or the fact that KEMRI has an automated LIMS system which uploads the testing results automatically from the testing devices, whereas NCRL is a manual process for test result upload. Mapping the strengths and weaknesses of the two laboratories can inform complementary interventions. This finding is similar to another from Western Kenya, implying that the health system inefficiencies may apply in various settings beyond the two counties [38]. The long overall TAT could have contributed to the sub-optimal linkage to VIA triage; long TATs have been shown to be associated with loss to follow-up from cervical cancer screening programs.

The main strength of this study is being operational research, it provided an opportunity to study implementation in a real-world as opposed to a traditional research setting. Therefore, the pilot provided key lessons on health system strengthening interventions needed to scale HPV testing in Kenya. However, the pilot had several limitations. In particular, only 30% of screened women had complete variables documented in the health information system. Possible explanations could be incomplete documentation at sample collection points, manual data entry at one of the testing laboratories, and failure to harmonize critical variables in the paper-based system at health facilities and electronic systems at the testing laboratories. Also, we were not able to track critical components of the cascade, including results returned to clinic or to patients. Lastly, it was established that the two laboratories do not report to the KHIS. A robust health information system is critical for an effective fail-safe mechanism in CaCx screening [39].

Conclusion

A centralised sample referral strategy leveraging on integrated service delivery models of care can enable Kenya implement successfully the WHO-recommended strategies and interventions towards cervical cancer elimination. However, for this to be realized, specific interventions and investments are required to be undertaken to strengthen the integrated health system to be more responsive for cervical cancer elimination. A harmonised, efficient, and robust health information system accompanied by sensitization of health workers is critical in this regard to minimise data loss within integrated service delivery models of care which could hinder progress in achieving elimination targets. Self-collected and clinician collected samples were comparable in terms of test results and other sample parameters in this implementation setting, and therefore self-collection would be a resourceful approach in settings where screening hesitancy is driven by fear of pelvic examinations.

As shown in this pilot, >50% screening coverage and full utilization of all available screening tests demonstrated the demand for HPV screening commodities. Ensuring regular availability of key commodities is necessary for an effective HPV-based cervical cancer screening program in Kenya. To achieve elimination, linkage to care requires optimization, especially in such a stable population like the one targeted in this pilot, with regular interaction with the healthcare system. An effective fail-safe mechanism is necessary to ensure all HPV positive women are triaged. This includes innovations in the facility-patient interface to ensure prompt communication and relay of results, linkage, and compliance to treatment. A screening registry supported either by an electronic medical records system platform or a detailed paper-based client details capture form can improve tracking of screened clients. The Health Information System should be comprehensive enough to track screened clients from sample acquisition, sample transmission to the lab, reporting of results, triaging, treatment, and follow-up. Adoption of digital health platforms and electronic records system can be one approach to achieve this, especially with a community support application and a sample tracking mechanism. Including HPV testing in the UHC benefits package can increase uptake while not compromising on the continuum of care. This will help move Kenya beyond pilot testing and opportunistic testing to implementing large-scale population-based approaches.

What is already known about the topic

- Many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are exploring strategies for scaling HPV testing as a high-precision cervical cancer screening modality.

- Various sample collection and testing pathways exist, including self-versus health worker sample collection; test-and -treat versus test-triage-treat approaches, use of near-point-of care platforms like GeneXpert or use of centralized multiplex systems.

- An earlier pilot study in Kenya evaluating feasibility of integrating HPV testing into existing GeneXpert platforms demonstrated testing backlogs due to competing priorities like TB testing.

What this study adds

- Sample referral from health facilities to central laboratories is a feasible strategy for scaling HPV testing in LMIC setting like Kenya.

- Long turn-around times, inadequate sample and/or client tracking ad resultant loss-to follow-up are the main challenges to a sample-referral strategy.

- Integration into existing sample referral mechanisms (e.g. for TB or HIV) as well as laboratory information management systems can address some of these challenges.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the respective county directors of health from the two counties, the cervical cancer program County focal persons, the community health workers and healthcare workers who were pivotal in the implementation of the pilot. We also acknowledge technical support provided by the Clinton Health Access Initiative, during the conduction of this assessment.

Authors´ contributions

VM, JP, LO and SO planned the pilot procedures, including monitoring and evaluation; PN and MN provided leadership and coordination during the assessment; DM, VM and JN conducted the analysis and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. All the authors have read the final version of the manuscript and consent to its publication.

Availability of data and materials

The assessment dataset has been provided as supplementary information

| Participating institutions | Participating facility | County | Target population (30–49 years) | Coverage | HPV Positivity | VIA triage | VIA positive | Treated | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. tested | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| SWOP | SWOP City | Nairobi | 1794 | 817 | 45.5 | 195 | 23.9 | 155 | 79.5 | 22 | 14.2 | 22 | 100.0 |

| SWOP Kawangware | Nairobi | 927 | 461 | 49.7 | 93 | 20.2 | 93 | 100.0 | 6 | 6.5 | 6 | 100.0 | |

| SWOP Langata | Nairobi | 1100 | 487 | 44.3 | 106 | 21.8 | 88 | 83.0 | 24 | 27.3 | 24 | 100.0 | |

| SWOP Thika Road | Nairobi | 1414 | 770 | 54.5 | 167 | 21.7 | 111 | 66.5 | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 100.0 | |

| SWOP Donholm | Nairobi | 877 | 705 | 80.4 | 142 | 20.1 | 97 | 68.3 | 44 | 45.4 | 44 | 100.0 | |

| SWOP Kariobangi | Nairobi | 1528 | 701 | 45.9 | 157 | 22.4 | 114 | 72.6 | 30 | 26.3 | 30 | 100.0 | |

| SWOP Majengo | Nairobi | 1408 | 461 | 32.7 | 157 | 34.1 | 50 | 31.8 | 8 | 16.0 | 8 | 100.0 | |

| COEHM | Pumwani Maternity Hospital | Nairobi | 1395 | 1041 | 74.6 | 84 | 8.1 | 76 | 90.5 | 41 | 53.9 | 40 | 97.6 |

| Kenyatta National Hospital | Nairobi | 3510 | 1547 | 44.1 | 368 | 23.8 | 226 | 61.4 | 41 | 18.1 | 18 | 43.9 | |

| Thika Level 5 | Kiambu | 1680 | 1690 | 100.6 | 223 | 13.2 | 223 | 100.0 | 21 | 9.4 | 21 | 100.0 | |

| Kiambu Level 5 | Kiambu | 1347 | 716 | 53.2 | 79 | 11.0 | 79 | 100.0 | 13 | 16.5 | 9 | 69.2 | |

| Wangige Level 4 | Kiambu | 435 | 391 | 89.9 | 62 | 15.9 | 8 | 12.9 | 2 | 25.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Tigoni Level 4 | Kiambu | 435 | 313 | 72.0 | 21 | 6.7 | 10 | 47.6 | 8 | 80.0 | 5 | 62.5 | |

| Igegania Level 4 | Kiambu | 315 | 309 | 98.1 | 29 | 9.4 | 29 | 100.0 | 8 | 27.6 | 8 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 18165 | 10409 | 57.3 | 1883 | 18.1 | 1359 | 72.2 | 269 | 19.8 | 236 | 87.7 | ||

SWOP: Sex Workers Outreach Program; COEHM: University of Nairobi’s Centre of Excellence in HIV Medicine; HPV: Human papillomavirus; VIA: Visual inspection with acetic acid

| Time period | Mean turn-around times (TAT), in days | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| KEMRI laboratory | NCRL | ||

| Sample collection to reception at the laboratory | 12.1 (9.3) | 8.1 (26.8) | <0.001 |

| Sample reception to testing | 15.8 (14.0) | 2.1 (3.8) | <0.001 |

| Sample testing to transmission of results | 0.4 (0.7) | 23.9 (29.6) | <0.001 |

| Total TAT | 28.3 (16.1) | 33.8 (28.2) | <0.001 |

| Variable | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| <25 | 82 | 2.6 |

| 25–49 | 2,717 | 87.0 |

| 50+ | 324 | 10.4 |

| HIV status | ||

| Positive | 1,280 | 50.0 |

| Negative | 1,091 | 34.9 |

| Unknown | 752 | 24.1 |

| Type of screening visit | ||

| Initial | 2,066 | 66.2 |

| Routine | 673 | 21.5 |

| Post-treatment screening | 11 | 0.4 |

| Unknown | 373 | 11.9 |

| Method of sample collection | ||

| Self-collection | 486 | 15.6 |

| Clinician collected | 2,637 | 84.4 |

| Variable | Sample collection method | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinician (N=2,637) n (%) | Self (N=486) n (%) | ||

| HPV positivity | |||

| Positive | 642 (24.3) | 101 (20.8) | 0.090 |

| Negative | 1,995 (75.7) | 385 (79.2) | |

| Sample validity | |||

| Invalid | 74 (2.8) | 14 (2.9) | 0.927 |

| Valid | 2,563 (97.2) | 472 (97.1) | |

| Laboratory results status | |||

| Unknown | 3 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.457 |

| Known | 2,634 (99.9) | 486 (100.0) | |