Research![]() | Volume 8, Article 26, 25 Apr 2025

| Volume 8, Article 26, 25 Apr 2025

Acute respiratory infections surveillance system evaluation, Mozambique, June-December 2021

Florência Vicente Chiconela Cossa1,&, Gerson Afai1, Nilsa Nascimento2, Cristolde Atanásio Salomão2, Auria Ribeiro Banze2, Cynthia Semá Baltazar1,2

1Field Epidemiology Training Program, Mozambique, 2Instituto Nacional de Saúde, Marracuene, Mozambique

&Corresponding author: Florência Vicente Chiconela Cossa, Field Epidemiology Training Program, Instituto Nacional de Saúde, Marracuene, Mozambique, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-6469-462X, email: chiconelaflo@gmail.com

Received: 14 Jan 2025, Accepted: 24 Apr 2025, Published: 25 Apr 2025

Domain: Surveillance System Evaluation, Acute Respiratory Infections

Keywords: Acute respiratory infections, COVID-19, Rapid diagnostic test, Mozambique

©Florência Vicente Chiconela Cossa et al Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Florência Vicente Chiconela Cossa et al Acute respiratory infections surveillance system evaluation, Mozambique, June-December, 2021. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8:26. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00024

Abstract

Background: COVID-19 is a public health emergency with a huge morbidity and mortality impact on the population, and rapid diagnostic testing is essential for controlling the disease. The study evaluated the surveillance system for acute respiratory infections in sentinel posts, Mozambique, from 01 June to 31 December 2021.

Methods: We evaluated the surveillance system using the CDC’s Public Health Surveillance Guidelines. Representativeness, acceptability, data quality and timeliness were assessed in 30 sentinel posts in ten provinces of Mozambique, with the exception of Maputo City. The data were analyzed and presented as proportions in text, graphs and tables.

Results: The surveillance system captured a large number of suspected cases, totaling 21,238 across 10 provinces. The highest number of suspected cases was registered in females 55% (11,668/21,238) and the 15-49 age group 43% (9,082/21,238). The months with the highest number of cases were November 25% (5,245/21,238) and August 18% (3,885/21,238). Of the 793 forms identified, 76% had a closed result with the rapid antigen diagnostic test, implying unacceptability. The completeness rate for age was 93%, COVID-19 vaccination status was 52%, and test results was 76%; with an overall completeness rate of 74% denoting regular data quality. Of the 42 interviewees, 69% (29/42) reported that the notification and availability of data in the Laboratory Information Management System took less than 24 hours.

Conclusion: The system was representative with regular data quality but lacked acceptability and timeliness. There is a need for training and sensitization of professionals in properly completing forms and logbooks.

Introduction

In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) characterized Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) as a public health emergency of international concern, caused by coronavirus subtype 2 or severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1]. WHO recommends evaluating the rapid diagnostic antigen test to obtain more evidence of its performance during implementation, considering the prevalence of each country or geographical region [2]. Due to the increased reporting of COVID-19 cases in African Union member states, WHO has modified the definition of a suspected COVID-19 case to include COVID-19 as an integral part of severe acute respiratory infection and advises the testing of all cases with severe acute respiratory infection [3]. Most Member States have sentinel surveillance systems for influenza-associated diseases and severe acute respiratory infection, including COVID-19 [3].

The active surveillance system for COVID-19 in Mozambique began in March 2020 with three sentinel posts for influenza and severe acute respiratory infection surveillance in Maputo City [4]. In April, the system was gradually expanded and now all provinces collect samples from the COVID-19 active surveillance system, with a view to increasing the detection of COVID-19 cases [4]. Until 31 March 2021, Mozambique saw an exponential increase in confirmed cases and deaths in January 2021. The average number of daily cases was about four times higher than in the first wave and had a total of 2,101.14 cases per million inhabitants [5]. The majority of COVID-19 cases in Mozambique were registered in Maputo City and Province, with a total of 38,203 cases, corresponding to 57% of the total cases [5]. The challenge posed to the surveillance system for acute respiratory infections in response to the ongoing global pandemic of the novel corona virus, known as SARS-CoV-2, requires reliable reporting of suspected cases from sentinel centers to the laboratory information management system for the purpose of informing public health decision-making. In order to ensure the reliability of this process, it is imperative that case records in logbooks and case notification forms are complete, up-to-date and reliable, particularly in the context of the ongoing pandemic. Incomplete reporting can have a negative impact on registration, case reporting and health surveillance activities, making it essential to carry out studies on this issue. This evaluation aimed to assess the surveillance system for acute respiratory infections in sentinel posts in Mozambique, from 01 June to 31 December 2021.

Methods

Study design

This was a surveillance system evaluation using the CDC’s Public Health Surveillance Guidelines 2001 [6].

Population and study period

The study population comprised all patients who presented with a respiratory infection at the designated sentinel clinics during the study period, which ran from 1 June to 31 December 2021.

Acute respiratory infection surveillance system case definitions

The case definition for severe acute respiratory infections is an acute respiratory infection with a documented history of fever or measured fever of ≥38°C, cough and onset within the last 10 days. It requires hospitalization [7].

The case definition for influenza-like illness is an acute respiratory infection accompanied by a measured fever of ≥38°C, cough and onset within the last 10 days[7].

Study site

The evaluation was conducted in 30 sentinel posts in ten provinces of Mozambique namely Maputo Province, Inhambane, Gaza, Manica, Sofala, Zambezia, Tete, Nampula, Niassa and Cabo Delgado with the exception of Maputo City, as it is the city in the country with the highest COVID-19 testing rate.

Data source

The data were collected using registry books and notification sheets for suspected cases of acute respiratory infections from the emergency services, antiretroviral treatment service, adult triage, pediatric triage, outpatient clinics and laboratory. In addition, semi-structured interviews were conducted with the focal points of the surveillance system from 1 June to 31 December 2021.

Sampling procedures

By January 2022, 62 sentinel sites had been established in the country for the active surveillance of acute respiratory infections. The present evaluation was conducted in the ten provinces of Mozambique, excluding Maputo City. In each province, three health centers were selected as sentinel sites for the active surveillance of acute respiratory infections, resulting in a total of 30 health facilities. The evaluation was conducted in ten provinces due to the under-reporting of suspected cases of acute respiratory infections. The month to be evaluated at each sentinel site was selected at random using Microsoft Excel. All the focal points operating in the acute respiratory infection surveillance system were interviewed.

Data analysis

The data was analyzed in Microsoft Excel 2010 and presented as proportions.

Description of the surveillance system for acute respiratory infections

In Mozambique, the surveillance system was established in 2013 in response to the influenza virus, and the same platform was utilised for the expeditious response to the contemporary global pandemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) caused by the new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) [8].The objective of the sentinel surveillance system is to monitor epidemiological trends, seasonality and the circulation of influenza variants, SARS-CoV-2, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and other respiratory viruses [8]. The surveillance system is guided by the guidelines established by WHO, and its scope of application covers individuals of all age groups, in both outpatient (Mild Acute Respiratory Infections) and inpatient or observation (Severe Acute Respiratory Infections) settings [8,9]. The alerts generated by the acute respiratory infection surveillance system are monitored in real time by the National Health Institute’s Alert Observation System, and the results are periodically released to the public [8].The sentinel health units are currently located in Maputo City, Maputo Province and Sofala Province [8].

Notification of acute respiratory infections in sentinel centers

Sentinel centers are responsible for the detection of suspected cases of acute respiratory infection, for which a case definition is used. All suspected cases are then screened by the emergency services, the antiretroviral treatment service, adult triage, pediatric triage and outpatient consultation. The focal points use case notification forms to record patient data, and this information is also recorded in the health unit’s log books. All suspected cases are referred to and tested at the sentinel point laboratory, and the laboratory and the adult screening focal points then compile the data collected from the samples tested at the various services and communicate it electronically via smartphones to the National Health Institute’s Laboratory Information Management System. The sentinel posts’ smartphones require Internet access to send the data from the results of the analyzed samples to the system, and all analysed samples must be notified to the system within 24 hours.

Evaluated Attributes

An evaluation of the surveillance system was conducted to ascertain its usefulness, with a focus on four key attributes: quantitative analyses of data quality and timeliness, as well as qualitative descriptive analyses of representativeness and acceptability. This evaluation will facilitate a more profound comprehension of the system, allowing for the formulation of recommendations to enhance its performance and address the needs it proposes. Consequently, this will result in benefits for the system’s focal points and patients treated at the provincial sentinel posts.

Representativeness: The proportion of suspected cases of acute respiratory infections in the population by person, place, and time was verified. This attribute looked at the surveillance system’s ability to identify suspected cases of acute respiratory infections by age group, sex, province, and the period under analysis (the months from 1 June to 31 December 2021). If the surveillance system was able to describe the disease in the 10 provinces of Mozambique, with an emphasis on age, gender, place and period, it would be representative [10].

Acceptability: For acceptability, the completeness of the notification forms for cases closed with the result of the rapid antigen diagnostic test was assessed. It was determined that a completeness rate of ≥80% would be considered acceptable, while a rate of <80% would be considered unacceptable [11].

Data quality: The quality of the data was analyzed in terms of the completeness of the data for these three study variables: age, COVID-19 vaccination status and result of the rapid antigen diagnostic test, as these are extremely important variables for the acute respiratory infection surveillance system. A proportion of forms with completeness greater than or equal to (≥) 90% was considered excellent, 70% to 89% regular, and less than (<) 70% poor [12].

Timeliness: In this study, timeliness was assessed through interviews with 42 focal points responsible for the surveillance system for acute respiratory infections at each sentinel post in Mozambique’s 10 provinces. The focal points were asked about their knowledge of the time interval between notification of cases by the sentinel post and the availability of data in the laboratory information management system. The response time was classified as timely (≤24 hours and response rate ≥80%) or untimely (response time >24 hours and response rate <80%) [3,13].

Ethical consideration

This was a public health emergency that required an immediate assessment using rapid diagnostic tests for the SARVS-COV-2 antigen, which are first-line tests in response to the COVID-19 problem in Mozambique. Therefore, no formal ethical approval was sought. However, the evaluation and implementation was monitored and authorized by the Instituto Nacional de Saúde, in consultation with the Directorate of Provincial Health Services. The participants interviewed gave their informed consent.

Results

The surveillance system recorded 21,238 suspected acute respiratory infection cases across ten provinces, and of these, 33% (7,075/21,238) were tested for COVID-19 and 25% (1,769/7,075) were positive for COVID-19.

Description of the system’s attributes

Representativeness

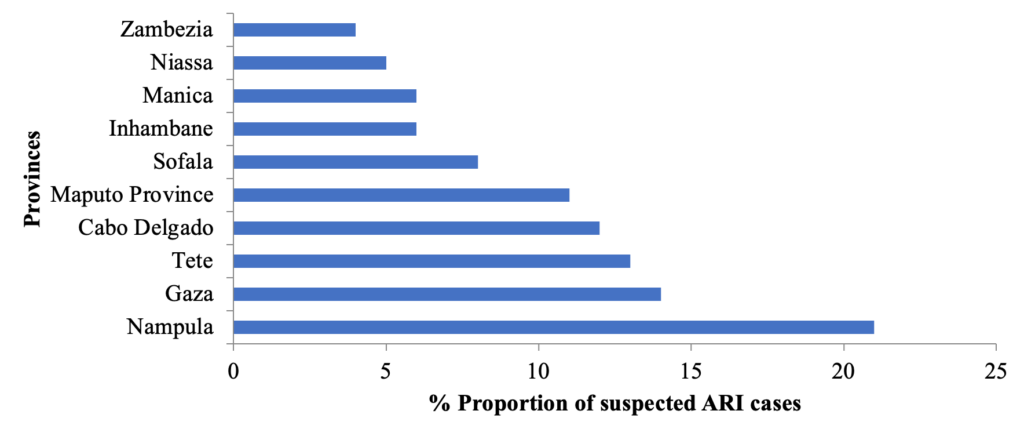

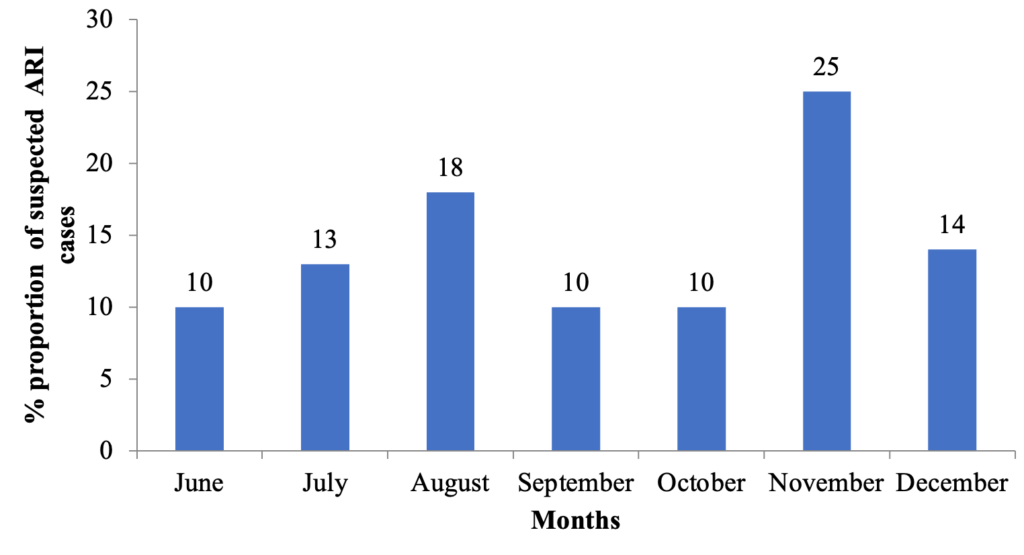

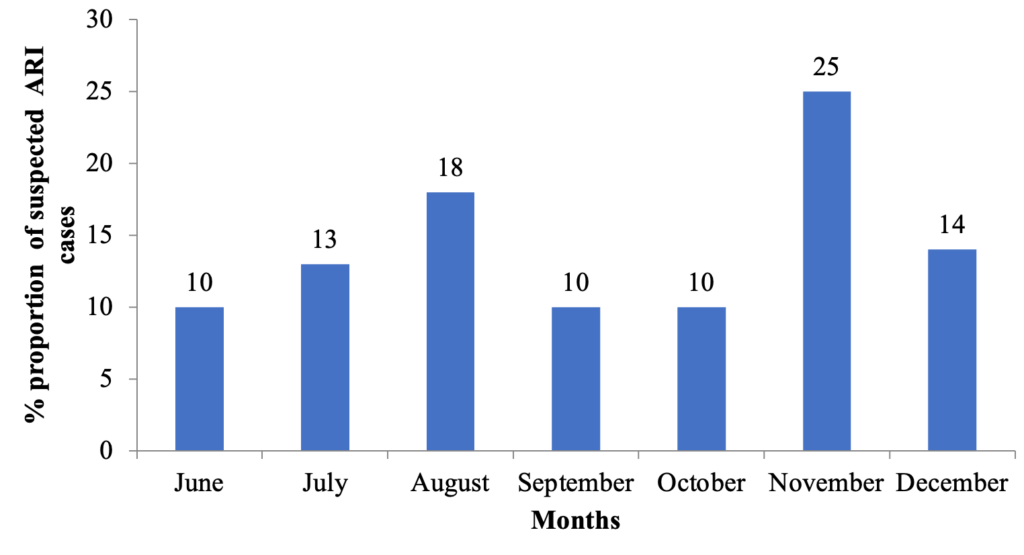

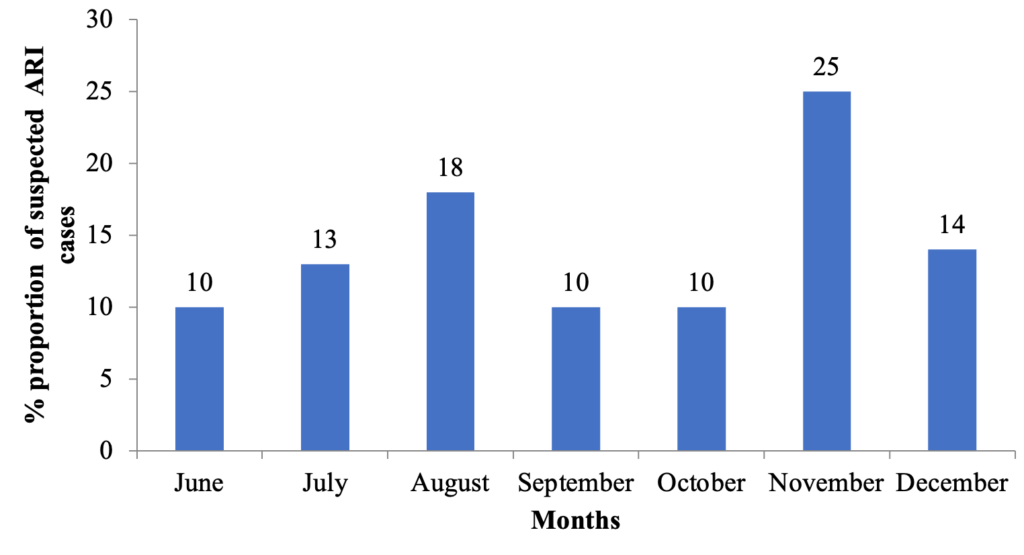

Suspected cases of acute respiratory infections were analyzed by person, place, and time. The majority of suspected cases of acute respiratory infections were female, 55% (11,668/21,238). The age group with the highest number of cases was 15-59 years 43% (9,082/21,238) followed by children aged 0-4 years 29% (6,196/21,239) (Table 1). Nampula province recorded 21% (4,455/21,238) of suspected cases of acute respiratory infections, followed by Gaza and Tete with 14% (2,924/21,238) and 13% (2,856/21,238) respectively, encompassing all the provinces under study (Figure 1). Cases of acute respiratory infections were reported in the 10 provinces of Mozambique from June to December 2021, with the highest number of suspected cases of acute respiratory infections in the months of November with 25% (5,245/21,238) and August 18% (3,885/21,238) (Figure 2). The acute respiratory infection system was able to describe the disease in the 10 provinces of Mozambique, with an emphasis on age, gender, place and period, so it was considered representative.

Acceptability

In terms of data acceptability and quality, the completeness of the data on the notification forms for suspected cases of acute respiratory infections in the 10 provinces of Mozambique was assessed. In order to assess these two attributes, a random sample of 30 case notification forms was selected, under the assumption that the total number of existing forms at the sentinel posts is unknown. In each province, 90 forms were evaluated, resulting in a total of 900 notification forms across the 10 provinces. Each sentinel site was to evaluate 30 forms. Due to the unavailability of 11.9% (107) of the forms at the sentinel posts in the provinces of Inhambane (01), Manica (30), Niassa (08), Sofala (32), Tete (23) and Zambézia (13), only 88.1% (793) of the forms were evaluated.

Of the 793 forms identified in the 10 provinces under analysis, 76% (601/793) of these suspected cases of acute respiratory infections/COVID-19 had rapid diagnostic antigen test closed with positive and negative results. The six provinces that closed with a rapid diagnostic antigen test result greater than or equal to (≥ ) 80% were Niassa 82% (67/82), Nampula 95% (86/90), Manica 100% (60/60), Tete 89% (60/67), Inhambane 91% (81/89) and Maputo Province 90% (81/90). The provinces that closed with a rapid diagnostic antigen test result of less than (<) 80 percent were Cabo Delgado, Zambezia, Sofala and Gaza. The system was classified as not acceptable with 76% (601/793).

Data quality

The completeness of data on the three variables of interest: age, COVID-19 vaccination status , and rapid diagnostic antigen test result was checked on the 793 case notification forms. In all the provinces assessed, the completeness of the age variable on the form was excellent at 93% (735/793). Cabo Delgado province had 100% (90/90) completeness of the age variable and Maputo province had 65% (56/90) poor completeness. The completeness of the COVID-19 vaccination status variable across all provinces was poor at 52% (412/793). The seven provinces in Mozambique with completeness below 70% were Maputo Province, Cabo Delgado, Zambezia, Sofala, Nampula, Tete, and Niassa (Table 2). The completeness of the disease confirmation variable across all provinces was 76% and was classified as regular. The provinces of Cabo Delgado, Zambezia and Sofala had completeness below 70% in the rapid diagnostic antigen test result variable. The completeness of the three variables studied was 74% in the 10 provinces analyzed and data quality of the system was classified as regular.

Timeliness

Forty-two focal points operating in the acute respiratory infection/COVID-19 surveillance system were interviewed about the time between case notification and data being made available in the Laboratory Information Management System, and of these, 69% (29/42) of the professionals reported that case data is notified, entered and made available in a period of less than or equal to 24 hours. The response rate was 69%. The operational capacity regarding the notification of suspected cases of acute respiratory infections/COVID-19 was considered not to be timely.

Discussion

Representativeness

Updating the COVID-19 case definition improved case reporting across all provinces in Mozambique, making notification mandatory in the acute respiratory infection surveillance system. A similar study carried out in Brazil classified the severe acute respiratory syndrome surveillance system as representative, as it was able to notify cases throughout Brazil over the period analyzed [10]. During this period, it was observed that despite the detection of suspected cases of acute respiratory infection at sentinel posts, laboratory support continues to be a challenge for the surveillance system in Mozambique. This is because some provinces did not have sentinel posts for detecting suspected cases, which may have influenced the low testing and reporting of cases in the system. In this context, it was also observed that of the ten provinces that reported suspected cases of acute respiratory infection/Covid-19, only one province had a higher record of suspected cases compared to the other provinces. A similar study published in Brazil reported that the availability of diagnostic kits for COVID-19 continues to be a global problem, which has had a huge impact on disease surveillance actions, as the scarcity of this resource jeopardizes knowledge of the dynamics of transmission in the population and the definition of criteria for determining suspected cases and deaths from COVID-19 [14]. However, the actual number of cases is likely to be significantly higher, given the weak health system, as well as its limited coverage beyond Mozambique’s urban and peri-urban areas [15]. In the months of November and August, there were more cases of acute respiratory infections /COVID-19, which coincided with the cold season, contributing to the transmissibility of the SARS-COV-2 virus and respiratory infections. A study carried out in Angola revealed a higher number of cases of severe respiratory infections and the behavior of the disease in the endemic corridor between the months of April and August in the provinces of Benguela, Huambo, Kwanza Norte, while Moxico, Namibe, and Uíge occur between the months of June and November [16]. Although the epidemic waves in some regions occurred mainly in colder periods (a possible seasonal pattern), the existing evidence indicates that the waves were the result of the degree of pathogenicity and transmissibility of the emerging and circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants and an increase in case registrations in the colder periods of the year, between March and August (the coldest period of the year) [10,17].

Acceptability

The acute respiratory infections /COVID-19 surveillance system has not been acceptable, despite the strategies adopted for surveillance; the detection of suspected cases is still a challenge. The insufficiency and lack of case notification forms may have influenced the under-reporting or under-recording of acute respiratory infections/COVID-19 cases in some sentinel posts or provinces.

Data quality

The selection of variables was predicated on three criteria: age, the status of the patient’s vaccination against the novel coronavirus, and the result of a rapid diagnostic antigen test. These variables were deemed essential in providing a comprehensive overview of the care provided to patients with acute respiratory infections (ARI). These fields facilitate the assessment of whether the healthcare provided to the individual, with the appropriate sample collection and vaccination status, was carried out properly and with quality. Consequently, they are important variables to complete in each case.

In all the provinces assessed, the completeness of the age variable on the form was excellent. Age with excellent completeness contributes to good representativeness, which makes the data evaluated more reliable and qualified. The completeness of the COVID-19 vaccination status variable across all provinces was poor. The variable relative to the history was showed that completeness was ‘poor’ and ‘very poor’ in the databases of regional and national data [18]. Another study conducted in Brazil found better outcomes among people who acquired COVID-19 when recently vaccinated against influenza[18]. Research has demonstrated that individuals who have recently received the influenza vaccination are more likely to survival of the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome, and less likely to require intensive care or respiratory assistance [19]. It is recommended that large-scale promotional initiatives be implemented to enhance the uptake of influenza vaccines, particularly among high-risk demographics with a high probability of severe SARS-CoV-2 infections[19].

The completeness of the disease confirmation variable across all provinces was regular. The confirmation criterion exhibited regular completeness [20]. Viral Watch specimen collection also exhibits a rapid decline outside the regular influenza season [21]. Absent a systematic data collection framework, the number of specimens collected may be reflective of the participation rates of sentinel sites as opposed to the true intensity of influenza transmission, thereby impeding the establishment of reliable baseline levels of activity [21]. The completeness of the data was considered regular on the forms, which may have influenced the underutilization or lack of case notification forms in the health services of sentinel posts or provinces. The completeness of the disease confirmation variable was 16 percent, with data quality classified as regular [20]. The presence of inconclusive cases, for which it was not possible to rule out or confirm the illness, may occur due to insufficient data, fields in the form left blank or filled inappropriately, or still due to the failure to collect samples for the performance of diagnostic tests [20].

Timeliness

The delay in case identification by professionals can lead to late dissemination of information, which can make it impossible to adequately adopt measures to prevent and control the disease in the community. The operational capacity of the system to timely notify suspected cases of acute respiratory infections /COVID-19 is a challenge in the provinces under analysis. Delays at any stage of the system lead to delays in disseminating the information analyzed, preventing the population and health professionals from having the information they need for timely and efficient action [22]. A study carried out in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, revealed that despite the strategies adopted by epidemiological surveillance to tackle COVID-19, using various sources of information to monitor the dynamics of the disease’s transmission, the timeliness of detecting COVID-19 cases is still a problem to be tackled [14]. Information and communication about the limiting aspects and the interpretation of the tests by professionals are essential if the population is not to have a low perception of the risk of transmission [1]. A low level of timeliness greatly increases the chances of uncontrolled community spread of the disease, since surveillance will detect viral circulation late [14].

Usefulness

The utility of the ARI surveillance system was assessed in terms of its ability to accomplish the established objectives. It was observed that the surveillance system had the capacity to monitor respiratory viruses, identify the age groups most susceptible to developing ARI, demonstrate the distribution and trend of cases over the study period, and identify the provinces most affected. The system was also able to identify cases by clinical-epidemiological criteria. Consequently, the ARI surveillance system was able to achieve the protocol’s objectives of monitoring epidemiological trends, seasonality, and the circulation of virus variants. The system was found to be useful.

Limitation

There was a shortage of 11.9% (107/900) case notification forms at some sentinel posts in the provinces under analysis. The late implementation of the surveillance system at Manica District Hospital in Manica province influenced the unavailability of forms during the period under analysis.

Conclusion

The system was representative with regular completeness but lacked acceptability and timeliness. Immediate training programs for health professionals are essential to improve data accuracy, enhance surveillance efficiency, and strengthen Mozambique’s response to future outbreaks. The implementation of ARI surveillance in Mozambique’s ten provinces enabled a rapid response to the emergency posed by the new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). We recommended that surveillance focal points be sensitized to ensure that the forms are filled in properly and completely; that technical support visits be intensified and that the availability of forms be guaranteed to avoid ruptures and consequent underreporting of acute respiratory infections /COVID-19 cases.

What is already known about the topic

- All suspected cases of severe acute respiratory infections must be screened for COVID-19 and fill in the case notification form completely and appropriately.

- The rapid antigen diagnostic test is essential for testing suspected COVID-19 cases.

What this study adds

- Updating the COVID-19 case definition to consider it a severe acute respiratory infection has contributed to the representativeness of the system.

- Improvement in the complete and appropriate filling out of the case notification form.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention staff for scientific supporting, who did everything possible to ensure the quality of this manuscript through their comments and critical analyses. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Erika Valeska Rossetto, FETP Resident Advisor, for her exceptional contributions to this manuscript. Her mentorship throughout the entire process has been invaluable. From the initial development of the research protocol to the intricate analysis and writing phases, Erika provided unwavering support and guidance.

| Variables | Suspected Cases | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | 0-4 | 6,196 | 29 |

| 5-14 | 4,571 | 22 | |

| 15-49 | 9,082 | 43 | |

| 50-59 | 0 | 0 | |

| ≥60 | 839 | 3 | |

| Without age | 550 | 3 | |

| Sex | Male | 9,570 | 45 |

| Female | 11,668 | 55 |

| Province | Evaluated Forms n | Age n (%) | COVID-19 vaccination status n (%) | Rapid antigen diagnostic test result n (%) | Completeness of 3 variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cabo Delgado | 90 | 90 (100) | 54 (60) | 37 (41) | 67% |

| Gaza | 90 | 89 (99) | 80 (89) | 67 (74) | 87% |

| Inhambane | 89 | 88 (99) | 65 (73) | 81 (91) | 88% |

| Manica | 60 | 59 (98) | 45 (75) | 60 (100) | 91% |

| Maputo Província | 90 | 56 (65) | 55 (61) | 81 (90) | 72% |

| Nampula | 90 | 74 (82) | 27 (30) | 86 (95) | 69% |

| Niassa | 82 | 81 (99) | 6 (7) | 69 (84) | 63% |

| Sofala | 58 | 58 (100) | 24 (41) | 25 (43) | 61% |

| Tete | 67 | 64 (95) | 12 (18) | 60 (85) | 66% |

| Zambezia | 77 | 76 (99) | 44 (57) | 35 (45) | 67% |

| Total | 793 | 735 (93) | 412 (52) | 601 (76) | 74% |

References

- Magno L, Rossi TA, Mendonça-Lima FW de, Santos CC dos, Campos GB, Marques LM, Pereira M, Prado NM de BL, Dourado I. Desafios e propostas para ampliação da testagem e diagnóstico para COVID-19 no Brasil [Challenges and proposals for expanding testing and diagnosis for COVID-19 in Brazil]. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva [Internet]. 2020 Jun 3 [cited 2025 Apr 24];25(9):3355–64. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-81232020000903355&tlng=pt https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232020259.17812020 Portuguese

- Ministério da Saúde. Guião para a implementação de testes de diagnóstico rápidos de antígenos para SARS-CoV-2 em Moçambique [Guide for the implementation of rapid antigen diagnostic tests for SARS-CoV-2 in Mozambique] [Internet]. Maputo (Moçambique): Ministério da Saúde ; 2020 Oct [cited 2025 Apr 25]. 18 p. Available from: https://docs.bvsalud.org/biblioref/2021/11/1344024/guiao-para-a-implementacao-de-testes-de-diagnostico-rapido-de-_xiWZf0U.pdf Download guiao-para-a-implementacao-de-testes-de-diagnostico-rapido-de-_xiWZf0U.pdf Portuguese

- African Union, Africa CDC.Protocolo para reforço da vigilância de doenças respiratórias agudas e doenças associadas á gripe para a COVID-19 em África [Protocol for strengthening surveillance of acute respiratory and influenza-related illnesses for COVID-19 in Africa] [Internet]. Adis Ababa (Ethiopia); African Union; 2020 Mar [cited 2025 Apr 25]. 17 p. Available from: https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/38350-doc-protocol_for_enhanced_sari_and_ili_surveillance_for_covid-19_in_africa_pt.pdf Download 38350-doc-protocol_for_enhanced_sari_and_ili_surveillance_for_covid-19_in_africa_pt.pdf Portuguese

- Observatorio Nacional de Saúde. COVID-19 em Moçambique: Relatório do 1° ano de 2020-2021 [COVID-19 in Mozambique 2020-2021: 1st Year Report ] . Maputo (Moçambique): Observatorio Nacional de Saúde; 2021[cited 2025 Apr 27]. 125 p. Available from: https://ons.gov.mz/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/ONS-Relatorio-do-1o-Ano-da-COVID-19-Mocambique.pdf. Download ONS-Relatorio-do-1o-Ano-da-COVID-19-Mocambique.pdf Portuguese

- German RR, Lee LM, Horan JM, Milstein RL, Pertowski CA, Waller MN, Guidelines Working Group Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Updated guidelines for evaluating public health surveillance systems: recommendations from the Guidelines Working Group. MMWR Recomm Rep [Internet]. 2001 Jul 27 [cited 2025 Apr 24];50(RR-13):1–35; quiz CE1-7. Available from: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/13376

- World Health Organization. Surveillance case definitions for ILI and SARI [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2014 [cited 2025 Mar 2]. [about 1 screen]. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/global-influenza-programme/surveillance-and-monitoring/case-definitions-for-ili-and-sari

- Instituto Nacional de Saúde. Boletim Anual da Vigilância das Infecções Respiratórias Agudas (IRA) [ Annual Bulletin of Surveillance of Acute Respiratory Infections (ARI)] [Internet]. Maputo ( Moçambique): Instituto Nacional de Saúde ; 2023 [cited 2025 Apr 24]. 4 p. Available from: https://ins.gov.mz/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Boletim-IRA_Draft3.1.pdf Download Boletim-IRA_Draft3.1.pdf Portuguese

- Instituto Nacional de Saúde. Relatório de Actividades 2013-2015 [Activity Report 2013-2015] [Internet]. Maputo ( Moçambique): Instituto Nacional de Saúde; [cited 2025 Apr 24]. 119 p. Available from: https://ins.gov.mz/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/R-A-INS-miolo-PrintRes.pdf Download R-A-INS-miolo-PrintRes.pdf Portuguese

- Ribeiro IG, Sanchez MN. Avaliação do sistema de vigilância da síndrome respiratória aguda grave (SRAG) com ênfase em influenza, no Brasil, 2014 a 2016 [ Evaluation of the surveillance system for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) with emphasis on influenza, in Brazil, 2014 to 2016] . Epidemiol E Serviços Saúde [Internet]. 2020 Jun 12[cited 2023 APr 24];29(3). Available from: https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2237-96222020000300311&lng=pt&nrm=iso&tlng=pt https://doi.org/10.5123/S1679-49742020000300013 Portuguese

- Organização Pan Americana da Saúde. Plano estratégico de preparação e resposta à COVID-19 (SPRP): Estrutura de monitoramento e avaliação [COVID‑19 Strategic Preparedness and Response (SPRP) Monitoring and Evaluation Framework] [Internet]. Brasilia (Brazil) : Organização Pan Americana da Saúde 2020 [cited 2025 Apr 24]. 54 p. Available from: https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/52943/OPASWBRAPHECOVID-1920134_por.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y Download OPASWBRAPHECOVID-1920134_por.pdf Portuguese

- Siqueira PC, Maciel ELN, Catão RDC, Brioschi AP, Silva TCCD, Prado TND. Completude das fichas de notificação de febre amarela no estado do Espírito Santo, 2017 [Completeness of yellow fever notification forms in the state of Espírito Santo, 2017 ]. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde [Internet]. 2020 Jun 10 [cited 2025 Apr 24];29(3). Available from: https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2237-96222020000300309&lng=pt&nrm=iso&tlng=pthttps://doi.org/10.5123/S1679-49742020000300014 Portuguese

- World Health Organization (Africa Region). Relatório relativo à Resposta Estratégica à COVID-19 na Região Africana da OMS Fevereiro a Dezembro de 2020 [Report on the Strategic Response to COVID-19 in the WHO African Region February to December 2020] [Internet]. Brazzaville (Congo): World Health Organozation; 2021 [cited 2025 Apr 25]. 65 p. Available from: https://www.studocu.com/row/document/universidade-eduardo-mondlane/historia-do-direito-mocambicano/012-who-afro-strategic-response-to-covid-19-a4-p-v3indd-final-pt/25844232 Download Relatório relativo à Resposta Estratégica à COVID-19 na Região Africana da OMS Fevereiro a Dezembro de 2020.pdf Portuguese

- Corrêa PRL, Ishitani LH, Abreu DMX de, Teixeira RA, Marinho F, França EB. A importância da vigilância de casos e óbitos e a epidemia da COVID-19 em Belo Horizonte, 2020 Aug 5 [The importance of case and death surveillance and the COVID-19 epidemic in Belo Horizonte, 2020]. Rev Bras Epidemiol [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2023 Dec 12];23:e200061. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1415-790X2020000100206&tlng=pt https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-549720200061 Portuguese

- United Nations Development Programme (Mozambique THE SOCIOECONOMIC IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON THE URBAN INFORMAL ECONOMY IN MOZAMBIQUE: Results from a panel survey of informal sector operators in Maputo [Internet]. Maputo (Mozambique): United Nations Development Programme; 2021 Nov 12 [cited 2025 Apr 28]. 33 p. Available from: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/mz/UNDP-MZ-Socioeconomic-impact.pdf Download UNDP-MZ-Socioeconomic-impact.pdf

- Cabrera PL, António A, González GR. Comportamento das infecções respiratórias agudas em Angola, no período 2012-2019: antevendo a pandemia da COVID-19 [Behavior of acute respiratory infections in Angola, in the period 2012-2019: anticipating the COVID-19 pandemic]. Rev Angolana Ciênc [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2023 Dec 12];2(2):1–19. Available from: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=704174611003 Portuguese

- Sidat M, Capitine I. Infeção por SARS-CoV-2 em Moçambique: a epidemiologia e os avanços alcançados com a vacinação contra a COVID-19. An Inst Hig Med Trop (Lisb) [Internet]. 2022 Oct 22 [cited 2025 Apr 24];90-98. Available from: https://anaisihmt.com/index.php/ihmt/article/view/432 https://doi.org/10.25761/anaisihmt.432 Portuguese

- Ribas FV, Custódio ACD, Toledo LV, Henriques BD, Sediyama CMNDO, Freitas BACD. Completude das notificações de síndrome respiratória aguda grave no âmbito nacional e em uma regional de saúde de Minas Gerais, durante a pandemia de COVID-19, 2020 [ Completeness of notifications of severe acute respiratory syndrome at the national level and in a health region of Minas Gerais, during the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020]. Epidemiol E Serviços Saúde [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Apr 25];31(2):e2021620. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2237-96222022000200301&tlng=pt https://doi.org/10.1590/S1679-49742022000200004 Portuguese

- Fink G, Orlova-Fink N, Schindler T, Grisi S, Ferrer APS, Daubenberger C, Brentani A. Inactivated trivalent influenza vaccination is associated with lower mortality among patients with COVID-19 in Brazil. BMJ Evid-Based Med [Internet]. 2021 Aug [cited 2025 Apr 25];26(4):192–3. Available from: https://ebm.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjebm-2020-111549 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2020-111549 Portuguese

- Maciel EL, Jabor PM, Goncalves Jr E, Siqueira PC, Prado TND, Zandonade E. Estudo da qualidade dos Dados do Painel COVID-19 para crianças, adolescente e jovens, Espírito Santo – Brasil, 2020 [Study of the quality of COVID-19 Panel Data for children, adolescents and young people, Espírito Santo – Brazil, 2020]. Esc Anna Nery [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Apr 24];25(spe):e20200509. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1414-81452021000500204&tlng=pt https://doi.org/10.1590/2177-9465-EAN-2020-0509 Portuguese

- Budgell E, Cohen AL, McAnerney J, Walaza S, Madhi SA, Blumberg L, Dawood H, Kahn K, Tempia S, Venter M, Cohen C. Evaluation of two influenza surveillance systems in south africa. PLOS ONE [Internet]. 2015 Mar 30 [cited 2025 Apr 24];10(3):e0120226. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0120226 https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0120226 Portuguese

- Waldman EA. Usos da vigilância e da monitorização em saúde pública [Uses of surveillance and monitoring in public health]. Informe Epidemiológico do Sus [Internet]. 1998 Sep [cited 2025 Apr 24];7(3):7–26. Available from: http://scielo.iec.gov.br/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S0104-16731998000300002&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=em http://dx.doi.org/10.5123/S0104-16731998000300002 Portuguese

Menu, Tables and Figures

Navigate this article

Tables

| Variables | Suspected Cases | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | 0-4 | 6,196 | 29 |

| 5-14 | 4,571 | 22 | |

| 15-49 | 9,082 | 43 | |

| 50-59 | 0 | 0 | |

| ≥60 | 839 | 3 | |

| Without age | 550 | 3 | |

| Sex | Male | 9,570 | 45 |

| Female | 11,668 | 55 |

Table 1. Distribution of suspected cases of acute respiratory infections by age group and sex in the 10 provinces of Mozambique, June to December 2021

| Province | Evaluated Forms n | Age n (%) | COVID-19 vaccination status n (%) | Rapid antigen diagnostic test result n (%) | Completeness of 3 variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cabo Delgado | 90 | 90 (100) | 54 (60) | 37 (41) | 67% |

| Gaza | 90 | 89 (99) | 80 (89) | 67 (74) | 87% |

| Inhambane | 89 | 88 (99) | 65 (73) | 81 (91) | 88% |

| Manica | 60 | 59 (98) | 45 (75) | 60 (100) | 91% |

| Maputo Província | 90 | 56 (65) | 55 (61) | 81 (90) | 72% |

| Nampula | 90 | 74 (82) | 27 (30) | 86 (95) | 69% |

| Niassa | 82 | 81 (99) | 6 (7) | 69 (84) | 63% |

| Sofala | 58 | 58 (100) | 24 (41) | 25 (43) | 61% |

| Tete | 67 | 64 (95) | 12 (18) | 60 (85) | 66% |

| Zambezia | 77 | 76 (99) | 44 (57) | 35 (45) | 67% |

| Total | 793 | 735 (93) | 412 (52) | 601 (76) | 74% |

Score: 0 to 100% Classification: Excellent: ≥90%, Regular: 70 – 89%, Poor: <70%

Table 2. Data quality – Completeness of the surveillance system for acute respiratory infections at sentinel posts in the 10 provinces of Mozambique, from June to December 2021

Figures

Keywords

- Acute respiratory infections

- COVID-19

- Rapid diagnostic test

- Mozambique