Commentary | Open Access | Volume 8 (4): Article 104 | Published: 17 Dec 2025

Assessing the implementation of the public health emergency operations centre in Ethiopia, 2017–2023

Menu, Tables and Figures

Navigate this article

Tables

| S. N | Regional PHEOC | Room size (m2) | Separate Conference room | Shared Conference Room | Electric Power (Routine/Generator) | ICT infrastructure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computer | Display TV | Server | Projector | ||||||

| 1 | Afar | 50 | Yes | No | Yes/Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | Harari | 50 | Yes | Yes | Yes/Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 3 | Somali | 20 | Yes | Yes | Yes/Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4 | SWEP* | 192 | No | No | Yes/No | Yes | No | No | No |

| 5 | SNNP* | 120 | Yes | Yes | Yes/Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 6 | BG* | 112 | No | Yes | Yes/Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 7 | Gambella | 63 | No | Yes | Yes/Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| 8 | Amhara | 77 | No | Yes | Yes/Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

*SWEP: Southwest Ethiopia Peoples; SNNP: Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples;

BG: Benishangul Gumuz

Table 1: Regional public health emergency operation centre establishment assessment,

PHEOC layout and ICT infrastructure report, Ethiopia, 2020

| S. N | Role | Qualification | Number | Designation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PHEOC Manager | MPH, Field Epidemiology | 1 | Regular |

| 2 | IT Expert | MBA, BSc., Computer Science & IT | 1 | Contract |

| 3 | PHEOC Technical Assistance | MPH, Field Epidemiologist | 3 | Contract, Seconded by partner |

| 4 | Watch Staff | Health Officer | 2 | Regular |

| 5 | Data Manager | MPH in Statistics | 1 | Contract |

| 6 | Call Center Operators | Health Officer, Nurse, Health Education | 45 | Contract |

| Total | 52 | |||

Table 2: National PHEOC human workforce in Ethiopia from August 2017 to December 2023

| S. N | Outbreak/Disaster | Period | Location of outbreak by regions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acute water diarrhea | Aug–Dec 2017 | Most of the regions in the country |

| 2 | Yellow Fever | 2018 | SNNPR region, Wolaita |

| 3 | Internal Displaced People | 2018, 2019 | Most of the regions in the country |

| 4 | EVD preparedness | 2019, 2021 | National level and point of entries |

| 5 | Cholera | July 2019 | Most of regions in the country |

| 6 | Vaccine derived polio virus outbreak response | 2019, 2020 | Somali, Oromo and SNNPR regions |

| 7 | COVID-19 | January 2020 – Ongoing (December 2023) | Nationwide |

| Drought and conflict induced humanitarian crisis | 2021, 2022 | Nationwide | |

| 8 | Monkeypox preparedness | 2022 | National level and point of entries |

| 9 | Multiple Public Health Emergencies (Malaria, Measles) | 2022 – 2023 | Nationwide |

| 10 | Marburg preparedness | 2023 | National level and point of entries |

| 11 | Cholera | March 2023 – Current ongoing (December 2023) | Nationwide |

Table 3: Public health emergencies that required emergency operation center (EOC) activation in Ethiopia, August 2017 to December 2023

Figures

Keywords

- Public Health Emergency Operation Centre

- Public Health Emergency Management

- Ethiopia

Shambel Habebe Watare1, Mohammed Hasen Badeso1,&, Addisu Daba Fufa1, Zewdu Asefa Edea2

1Public Health Emergency Operation Centre, Early Warning and Information System Management Directorate, Centre for the Public Health Emergency Management, Ethiopian Public Health Institute, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2Early Warning and Information System Management Directorate, Public Health Emergency Management, Ethiopian Public Health Institute, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

&Corresponding author: Mohammed Hasen Badeso, Public Health Emergency Operation Centre, Early Warning and Information System Management Directorate, Centre for the Public Health Emergency Management, Ethiopian Public Health Institute, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Email: direhasen@gmail.com, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4668-9638

Received: 26 Sep 2025, Accepted: 16 Dec 2025, Published: 17 Dec 2025

Domain: Outbreak Investigation and Response

Keywords: Public Health Emergency Operation Centre, Public Health Emergency Management, Ethiopia

©Shambel Habebe Watare et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Shambel Habebe Watare et al., Assessing the implementation of the public health emergency operations centre in Ethiopia, 2017–2023. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8(4):104. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00204

Abstract

Humanitarian crises and infectious diseases remain major global and national public health concerns, emphasizing the need for strong public health emergency management systems. Ethiopia established its Public Health Emergency Operations Centre (PHEOC) in 2017 to improve preparedness and response. Assessing the PHEOC’s experience is important for generating practical insights and lessons learned, yet limited evidence exists in this area. In this perspective, we discuss the experience of PHEOC implementation in terms of its core components from August 2017 to December 2023 and identify areas that need strengthening and lessons learned for effective public health emergency response in Ethiopia.

We conducted comprehensive desk reviews at the Ethiopia Ministry of Health, Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI), Regional Public Health Institutes, and Health Bureau using the READ (Ready materials, Extract data, Analyse data, Distil) approach. The major findings were synthesized and described thematically.

Between August 2017 and December 2023, the PHEOC handbook and Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), training curriculum and manuals, multi-hazard emergency preparedness and response plans, and several hazard-specific response plans developed; all core staff and more than 348 national and subnational experts in PHEOC and IMS; and 190 African Health Volunteers Corps (AVoHC) SURGE folks trained in public health emergency management principles; participatedin more than 10 simulation exercises; established 14 regional and 8 subregional PHEOCs; and strengthening the capacity of neighbouring countries such as South Sudan and Somalia in public health emergency management and coordinated responses to 11 major PHEs. These underscores how a strengthened PHEOC system contributes to enhanced regional and cross-border health security and resilience against public health threats.

Hence, the need to further enhance PHEOC, empowered by adequately implementing legal instruments; improving infrastructure; and conducting subsequent simulation exercises to test staff capability and PHEOC procedures, as well as plans for regional and subregional PHEOCs, is recommended.

Introduction

Public health emergencies require the coordinated and efficient utilisation of diverse experts and collaborative logistic efforts for effective response to disease outbreaks, disasters, displacements, and other public health concerns[1 – 4]. Therefore, to effectively handle emergencies, the public health emergency operation centre (PHEOC) acts as a hub to enhance the coordination of preparation, response, and recovery efforts for public health emergencies[1, 5]. Additionally, coordinating resources and information to support response actions during a public health emergency enhances communication and collaboration among relevant stakeholders[2, 5].

Currently, the health impacts of emerging and remerging disease outbreaks, natural and man-made disasters, climate change, and conflict have emphasised the need for robust emergency management systems [4, 6, 7]. To help meet these and other challenges, investments have been made to strengthen the capacity for prevention, mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery[4]. A functional public health emergency operations centre (PHEOC) is a crucial component in meeting the IHR (2005) minimum capabilities, and the need to establish a functional PHEOC has been recognized as one of the key thematic areas in the joint external evaluation (JEE) to prevent, detect and respond to public health threats [8, 9, 10]. Similarly, the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) urges all nations to possess a public health emergency operations centre (EOC) that operates in adherence to basic standards criteria. This includes the establishment of proficient, operational, cross-sector rapid response teams (RRTs) and real-time data systems. Moreover, EOC personnel should receive proper training to activate a unified emergency response within 120 minutes of detecting a public health crisis[9].

The government of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia established a Public Health Emergency Management (PHEM) system in 2009 [4]. The Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) coordinates the Public Health Emergency Management system, which aims to establish a resilient and efficient system for managing public health emergencies nationwide. Additionally, the system takes into account mobilizing government health resources to effectively and rapidly respond to health emergencies[4, 11]. It is also the lead agency for implementing International Health Regulation core competencies in Ethiopia [1, 4, 12]. Despite progress, the 2016 JEE highlighted major gaps in the coordination of operations and information[13]. Therefore, strengthening public health emergency operation coordination, like enhancing early detection, prevention and response, through enhancing PHEOC capacities, were prioritized within Ethiopia’s Health Sector Transformation Plan (HSTP II, 2021–2025) [11,12, 14].

Establishing and operating a PHEOC entails developing four core components: policies, plans, and procedures; information systems and data standards; skilled human resources; and communication technology and physical infrastructure [1, 2, 5]. These components are essential for improving real-time information flow, decision-making processes, and coordinated emergency response actions.

GHSA and IHR indicated that identifying public health emergency operation capacity is a priority for global health security since it improves the rapid detection of and response to public health threats, as well as mitigating their impacts on the affected population’s health and well-being [8 – 10]. However, limited evidence is available on PHEOC implementation, the challenges encountered, and the lessons learned in Ethiopia. Therefore, in this article, we discussed the experience of the PHEOC in terms of PHEOC core components such as physical and ICT infrastructure, plans and procedures, data and information systems and human resources, training and exercises and operations and functionalities between August 2017 and December 2023 and identified areas that need strengthening and lessons learned for effective public health emergency response in Ethiopia.

Methods

This study was conducted in Ethiopia, which is located in the Horn of Africa, covers 1,112,000 square kilometres, and has a population of about 110.14 million [15]. We conducted comprehensive desk reviews at the Ethiopia Ministry of Health, Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI), Regional Public Health Institutes, and Health Bureaux using the READ (Read materials, Extract data, Analyse data, Distil) approach[16]. We conducted a review of documents from online searches, grey literature, administrative reports, assessment results, and response reviews (intra-action review (IAR)/after-action reviews (AAR)). The review covered the period between August 2017 and December 2023.

Read materials: First, we established the criteria for the types of documents to be analysed, focusing on documents relevant to PHEOC. The document’s inclusion criteria were PHEOC strategies, policies, grey literature, administrative reports, and response reviews (IAR/AAR) with the full‑text of the document available. We excluded documents with no full‑text content and out of the review timeline. Extract data: The data extraction process involved carefully reviewing the selected strategic documents. We focused on extracting pertinent details regarding PHEOC experiences, lessons learned for effective public health emergency response, and areas needing improvement. This encompassed PHEOC experiences and core components such as physical and ICT infrastructure, plans and procedures; data and information systems; human resources, training and exercises; and operations and functionalities. Analyse and Distil: The analysis was conducted based on information extracted from reviewed documents. Findings were synthesized thematically. The final step involved refining and summarizing the findings from the analysis. This included organizing the extracted data into categories related to PHEOC experiences to present key findings in a coherent narrative that addresses the study objectives.

We also held discussions with the PHEOC Manager at EPHI to ensure the accuracy and verify data obtained during the document review. The major findings were synthesized and described thematically

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval and consent to participate were not required because the project is not research involving human subjects. The data collected for this study did not include any personally identifiable information or sensitive organisational data, and there was no patient and public involvement in this study.

Results

PHEOC establishment and governance

Establishing the PHEM and PHEOC: In Ethiopia, before the establishment of the PHEOC, public health emergency preparedness and response were coordinated by setting up ad hoc task forces (TFs) and technical working groups (TWGs). The national PHEOC was established in August 2017 and was activated for the first time to coordinate the acute watery diarrhoea (AWD) disease outbreak that happened in Ethiopia. Since then, it has been activated to coordinate various public health emergency responses. A roll-out plan was developed to establish PHEOC in all Ethiopian regions in 2018. Currently, PHEOCs are established at prioritized subnational levels below the regional level to manage public health emergencies in close proximity [17] [18].

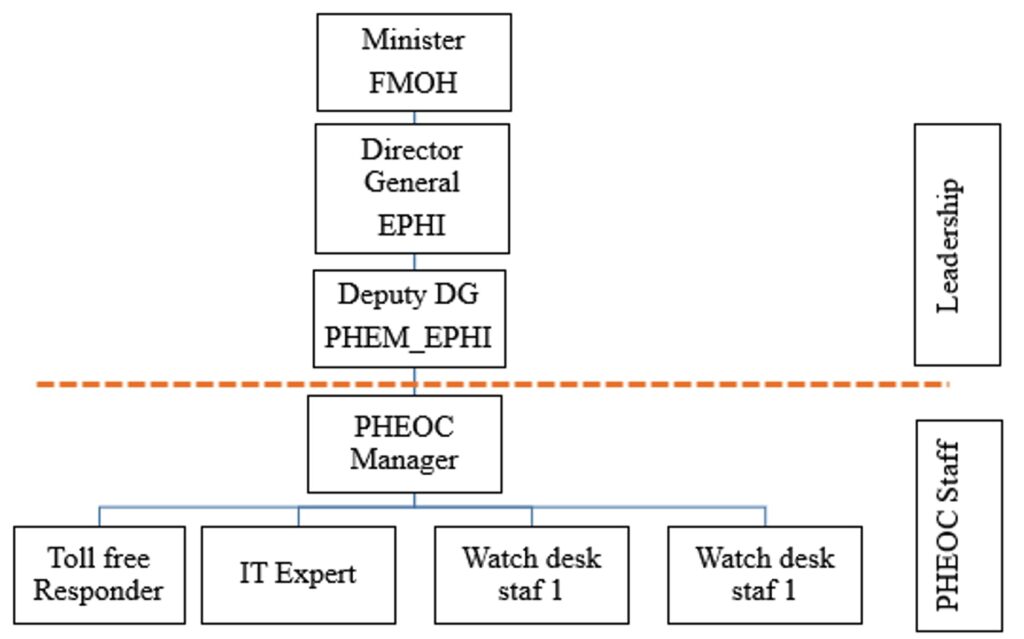

In Ethiopia, public health emergency management is the responsibility of the EPHI, which is an agency under the Ministry of Health (MOH). The national PHEOC structure is positioned in the Center for Public Health Emergency Management, which is led by the Deputy Director-General of the Ethiopian Public Health Institute [1] (Figure 1).

Legal authority: The public health emergency operation requirements explained in the constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia indicated that state executives can decree a statewide state of emergency should a natural disaster or an epidemic occur[17] and that a national policy on disaster risk management[20] and the Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) Regulation should implement international health regulations on grave public health emergencies with implications forinternational crises[21].

According to Council Minister’s Regulation 301/2013, the EPHI has the mandate to lead and coordinate national public health emergency preparedness, response, and recovery and rehabilitation efforts. Therefore, the public health emergency management centre based in the EPHI is designed to ensure rapid detection of any public health threats, preparedness related to logistic and fund administration, and prompt response to and recovery from various public health emergencies countrywide [4], [11]. Hence, the EPHI has been legally authorized to implement effective public health emergency management approaches. The revised Council Minister’s Regulation 529/2023 further defined the PHEOC and IMS and detailed the roles and responsibilities of the PHEOC in coordinating public health emergency preparedness, response and recovery efforts [11].

Understanding the concept of operation (CONOPS): The three-level, strategic, operational and tactical operations of public health emergencies in Ethiopia are defined. The MOH and EPHI senior management teams are the policy groups that provide strategic leadership and funding for emergency operations. The PHEOC at each administrative level discharges the operational-level coordination. The multiagency, multidisciplinary rapid response team (RRT) is responsible for the tactical (field)-level operations. Different levels and relevant stakeholders/agencies and key partners for emergency management interact with PHEOC depending on the type, scale and scope of the outbreak or event [1].

PHEOC core components

PHEOC physical and information communication technology infrastructure

National PHEOC infrastructure: The dedicated national PHEOC room is 45 square metres (m2) wide and provides workstations for 15 people. It is equipped with desks and chairs, desktop computers, a fixed and wireless internet network, a few landline telephones, two interactive display screens and one smart plasma screen used for media scanning and information display. There are 10 screens with digital signage technology that are mounted at different visible locations within the EPHI premises; these screens are linked to the PHEOC room and used for displaying dashboards and Critical Information Requirements (CIRs) and Essential Elements of Information (EEIs) to maintain situational awareness. There are also multipurpose spaces that have been used for expanded emergency situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the cholera outbreak and humanitarian crisis interventions for internally displaced people (IDP). There are shared conference rooms that are equipped with a smart plasma screen and an LCD projector for displaying information, but they are not interconnected with the PHEOC [18].

In addition to the physical PHEOC infrastructure, a Virtual Emergency Operations Centre (VEOC) platform was implemented at the national level at the Ethiopian Public Health Institute. The VEOC is utilized for the development and implementation of emergency plans and the dissemination of real-time information to various pillars during emergency management and regular PHEOC activities. None of the regions implemented the VEOC [18].

There is a standalone toll-free call centre to which the public calls 24/7 using an 8335 short number to report rumours and alerts and to receive reliable information related to public health emergencies. Currently, this call centre has the capacity to accommodate 24 direct callers at a time, and it is installed with interactive voice record (IVR) messages that were developed in five local languages for priority reportable diseases in the country so that the public can listen directly without necessarily reaching out to the call operators. In addition, the platform has features that allow the public to send alerts and inquiries through a recorded voice and obtain answers from subject matter experts through the moderation of call operators[22].

Regional PHEOCs infrastructures: The PHEOC expanded to all 14 regions of Ethiopia to facilitate improved emergency readiness, preparedness, response and recovery coordination nationwide. In addition, to decentralize and coordinate public health emergencies as closely as possible, eight subregional public health emergency operation centres were established in high-priority areas in the regions of Ethiopia. According to the assessment conducted in eight regions of Ethiopia[23], the Southwest Ethiopia regional PHEOC has the maximum room size (192 m2), and the Somali region PHEOC has the smallest room size (20 m2) (Table 1). All regions of Ethiopia have PHEOC functional with ICT infrastructure [18].

PHEOC data and information system

The PHEOC is situated within the Early Warning and Information System Management Directorate. Thus, the data obtained through the routine Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) and Event-based Surveillance (EBS) and from relevant sectors and agencies are linked and accessible to the PHEOC. The District Health Information System (DHIS-2) is being used for surveillance data reporting and management. In addition, Power BI software is used for dashboard development and visualization.

The virtual EOC platform was used for communication and information sharing among the incident management team,especially during the IDP response and during drought- and conflict-induced humanitarian crisis health interventions.

Plans and procedures: Ethiopia’s Public Health Emergency Operation Centre regularly prepares a multihazard emergency preparedness and response plan every year, considering the one-health and multiagency approaches. Incident-specific response plans have also been developed for prioritized lists of threats and hazards in the country, such as cholera, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the IDP, malaria, dengue, drought and related emergencies, as determined in the vulnerability risk assessment and mapping (VRAM) process. Furthermore, the Incident Action Plan (IAP) was developed whenever the PHEOC was activated and reviewed through the operational period to incorporate improvements and recommendations provided by the intra-action review (IAR).

The PHEOC handbook and standard operating procedures (SOPs) recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) was developed to guide routine activities and response operations. Additionally, a training programme including the participant and facilitator manual was developed and utilised to train a cadre of experts at the national, regional, subregional and local levels [1].

Staffing, training and exercises: The PHEOC functions are coordinated by regularly employed and temporary staff at the national and regional levels. Currently, the functions of the national PHEOC are coordinated by a team of eight core staff members, all of whom are trained in PHEM and 45 call centre operators [18] (Table 2).

Capacity-building and training to acquire the necessary skills and expertise in the PHEOC and Incident Management System (IMS) were conducted in Ethiopia at the national, regional and subregional levels in parallel with the expansion of PHEOC in the country. Within the observation period (August 2017 to December 2023), a total of eight staff members (four EPHI staff and four regional staff) completed a 4-month advanced Public Health Emergency Management Fellowship in Atlanta, Georgia, USA. At the national level, 12 rounds of training sessions were conducted, and 348 national and subnational experts were trained on PHEOC and IMS. In addition, 190 multidisciplinary and multisectoralpublic health cadres were trained on PHEOC as part of the African Health Volunteers Corps (AVoHC) SURGE training. Officials from regional and subregional PHEOCs were invited to visit the national PHEOC, the multisectoral coordination EOC at the National Disaster Management Agency and the continental PHEOC at the Africa CDC to obtain hands-on experience on how to operationalize PHEOC [18]. The roster of trained staff is maintained at the national PHEOC for the fulfilment of the identified positions upon the activation of the PHEOC, depending on the scale of the incident.

In addition to the real public health emergency response, different simulation exercises and tabletop exercises with public health emergency management officers and other multisector partners were used to test the PHEOC procedures, plans and operational capabilities of the staff and systems at the national level. Within the observation period (August 2017 to December 2023), the PHEOC conducted nearly 10 simulation exercises, which included tabletop exercises, drills, and functional exercises that lasted between 1 and 3 days [17].

PHEOC functions and activation in Ethiopia

The public health emergency operation centre receives surveillance information from the routine IDSR and EBS systems. The EBS is in place using hotlines, mainstream and social media and web scanning. The hotline contains 24 toll-free digital lines (8335 call centres) available for EBS and health information provision for the public by dedicated staff [1].

In Ethiopia, following its first establishment in August 2017, the PHEOC was initially activated to coordinate thewidespread occurrence of AWD outbreaks in various areas of the nation [1]. Since then, the PHEOC has been activated to coordinate a broad range of public health responses, including Ebola preparedness; humanitarian response for IDPs; malaria; measles; yellow fever; chikungunya; dengue fever; the COVID-19 global pandemic response; and drought-related public emergency response [17] (Table 3).

Throughout prior emergency coordination, the incident management system comprises varying pillars specific to each incident, contingent upon the need to expand. The largest number of pillars were applied during the COVID-19 pandemic, which was 13 pillars during the early PHEOC activation period[24]. Since 2017, throughout the experience of emergency response, the length of the operational periods indicated in the Incident Action Plan (IAP) has differed, and the interval operational period has been three to six months in duration.

Since its establishment, the PHEOC has coordinated four after-action reviews (AAR), including the AWD outbreak, yellow fever, 2019 Ebola-virus disease (EVD) outbreak preparedness and the COVID-19 pandemic, and two intra-action reviews, including the COVID-19 pandemic and cholera outbreak. The PHEOC also coordinated reviews of response progress for each activation during routine incident management team meetings [18].

Robust partnership and collaboration

Within the observation period (August 2017 to December 2023), delegates from South Sudan and Yemen officially visited Ethiopia’s PHEOC to learn best practices in establishing and implementing public health institutes and PHEOC. The Ethiopian PHEOC contributes to strengthening the capacity of neighbouring countries such as South Sudan and Somalia in public health emergency management. Additionally, there were higher officials and delegates from Africa, the World Bank, the US CDC, and the UKHSA who visited the centre. Furthermore, Ethiopia’s PHEOC virtually shared experiences and best practices in coordinating public health emergency response coordination for different African countries under the coordination of the African CDC and WHO AFRO [17, 18].

Discussion

This study was conducted to present the findings of the public health emergency operation centre experiences from 2017 to 2023 in Ethiopia. The findings showed that Ethiopia established a national and regional public health emergency operation centre to function as a central hub facilitating improved coordination of readiness, detection, response, and recovery from public health emergencies. The establishment and enhancement of the PHEOC were among the major plans indicated in the Ethiopia Action Plan for Health Security 2019-2023[10]. This is supported by the PHEOC expansion,which is important for meeting the core capacity requirements of the International Health Regulations (IHR 2005), which require that State Parties develop, strengthen and maintain their capacity to respond promptly and effectively to public health risks and public health emergencies of international concern[5, 25]. This requirement also supported legal authorities in Ethiopia, as indicated in the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia[17] and the Ethiopian Public Health Institute Regulation[21].

The Ethiopian Public Health Institute expanded the PHEOC to the regional and subregional levels, important for facilitating emergency preparedness and response at all levels. These are supported by the global health security agenda, and expanding to the regional and subregional levels is important for coordinating emergency response and operationalizing and planning functions contextualized to the site[26]. Additionally, expanding the technical, leadership, and infrastructure of incident management systems and PHEOCs is important for strengthening and sustaining the response capacity at all levels to incidences of multi-hazard national health security threats. Moreover, the World Health Organization, Africa CDC and Ethiopia NAPHS indicated that the expansion and strengthening of emergency operation centres through the establishment of regional EOCs were among the major areas needed to ensure health security[5, 10, 13]. Similarly, in Ethiopia, the establishment of PHEOC and the strengthening of emergency management resulted in emergency management improvements, indicating that the proportion of epidemics controlled within acceptable mortality rates increased from 40% in 2015/16 to 80% in 2017/18[12]. Additionally, public health emergency management in Ethiopia has been acquainted with improvements, with outbreak investigations and timely responses as indicated in HSTP I[12, 27]. However, the findings indicated gaps in workforce retention, sustainable financing, and connectivity. Similarly, these were reported across African countries, PHEOC systems[13, 14].

During the Pandemic Influenza outbreak in 2009 and the West African EVD preparedness in 2014, the term public health EOC and Incident Management System (IMS) was relatively new in Ethiopia, while the principles of emergency management were applied. In Ethiopia, the national PHEOC was established and activated in 2017 to coordinate the acute watery diarrhoea outbreak. Since 2017, different public health emergencies have been managed and coordinated through the activation of PHEOC at the national and subnational levels. This approach aligns with many African countries that have also formalised PHEOC structures linked to IMS and multi-tiered coordination systems[9, 13, 14, 24]. In addition to real public health emergency response, different simulation exercises and tabletop exercises with public health emergency management officers and other multisector partners were used to test PHEOC procedures and plans [13]. However, there is a weakness in adapting/developing simulation exercise materials for testing staff capability and testing PHEOC procedures and plans at the regional and subregional levels [13, 14].

The national PHEOC was established in a multipurpose space building, which can be expanded depending on the risk level of the incident and is equipped with information and communication technology infrastructure. This approach is consistent with WHO protocols, which indicate PHEOCs should be structured to support graded activation and rapid scalability to maintain continuity of operations[2][3, 5]. However, the report and assessment findings indicated a shortage of information and communication technology infrastructure equipment, qualified human resources, especially ICT experts at the regional and subregional PHEOC meetings [13, 18]. In addition to the physical infrastructure, the Virtual Emergency Operations Centre (VEOC) platform was utilized at the national level, consistent with internationally recommended protocols. The use of a VEOC aligns with WHO guidance that emphasizes integrated information management and digital platforms as essential components of modern PHEOC architecture [2, 3, 5]. It is crucial to establish lasting documentation of vital operational details in the event of an incident response, enabling secure access to such information from any location, and promoting the exchange of operational information among response collaborators[1, 13, 19].

The study reviewed available documents and reports between August 2017 and December 2023; thus, the results are not exempt from the constraints of systematic documentation of response mechanisms and other aspects of PHEOC implementation. However, despite these limitations, this study offers valuable insights and sheds light on the experience of PHEOCs in Ethiopia and offers lessons that may be useful for other countries.

Conclusion

A strengthened Public Health Emergency Operations Centre (PHEOC) enhances the capacity to respond effectively to public health threats, and contributes to national, regional, and global health security and resilience. Since 2017, when the first public health emergency operation centre was established in Ethiopia, various public health emergency responses have been coordinated in the country. The PHEOC system was expanded to all regions and prioritized subregional levels, supported by a customized national Virtual Emergency Operations Centre (VEOC) thus strengthening decentralized emergency management and improving real-time information flow for timely public health decision-making.

To further strengthen the emergency management system, it is recommended to empower the national PHEOC by adequately implementing legal instruments and improving infrastructure. Additionally, capacitate and equip the regionals and subregional PHEOC with infrastructure, qualified human resources and improve the interconnectedness between the PHEOCs at different levels, creating a permanent record of key operational information during an incident response through conducting intra-action and after-action reviews. Moreover, Adapt and conduct the simulation exercise to test staff capability and test PHEOC procedures and plans of the regional and subregional levels.

What is already known about the topic

- Public health emergencies require the coordinated and efficient utilisation of diverse experts and collaborative logistic efforts for effective response to disease outbreaks, disasters, displacements, and other public health concerns

- A functional public health emergency operations centre (PHEOC) is a crucial component in meeting the IHR (2005) minimum capabilities

What this study adds

- Establishing a national and regional public health emergency operation centre to function as a central hub facilitated improved coordination of readiness, detection, response, and recovery from public health emergencies

- A strengthened Public Health Emergency Operations Centre (PHEOC) enhances the capacity to respond effectively to public health threats, and contributes to national, regional, and global health security and resilience

Acknowledgements

We express our sincere appreciation to the Public Health Emergency Operations Centre staff for their support in reviewing the PHEOC documents included in this manuscript. Specific thanks are extended to the Ethiopian Public Health Institute for their support throughout the manuscript writing process.

Authors´ contributions

SH& MH: Contributed equally to the conception and design of the work, analysis and interpretation of the data, and development and revision of the manuscript. AD: Contributed to the design of the work, drafting of the initial manuscript, and revision of the manuscript. ZA: Contributed to the design of the work, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

List of abbreviations

CDC: Centres for Disease Control and Prevention;

EOC: Emergency Operation Centre:

EPHI: Ethiopian Public Health Institute;

PHEOC: Public Health Emergency Operation Centre;

GHSA: Global Health Security Agenda;

IHR: International Health Regulations;

MOH: Ministry of Health;

NAPHS: National Action Plan for Health Security;

VEOC: Virtual Emergency Operation Centre;

WHO: World Health Organization

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

| S. N | Regional PHEOC | Room size (m2) | Separate Conference room | Shared Conference Room | Electric Power (Routine/Generator) | ICT infrastructure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computer | Display TV | Server | Projector | ||||||

| 1 | Afar | 50 | Yes | No | Yes/Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | Harari | 50 | Yes | Yes | Yes/Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 3 | Somali | 20 | Yes | Yes | Yes/Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4 | SWEP* | 192 | No | No | Yes/No | Yes | No | No | No |

| 5 | SNNP* | 120 | Yes | Yes | Yes/Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 6 | BG* | 112 | No | Yes | Yes/Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 7 | Gambella | 63 | No | Yes | Yes/Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| 8 | Amhara | 77 | No | Yes | Yes/Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| S. N | Role | Qualification | Number | Designation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PHEOC Manager | MPH, Field Epidemiology | 1 | Regular |

| 2 | IT Expert | MBA, BSc., Computer Science & IT | 1 | Contract |

| 3 | PHEOC Technical Assistance | MPH, Field Epidemiologist | 3 | Contract, Seconded by partner |

| 4 | Watch Staff | Health Officer | 2 | Regular |

| 5 | Data Manager | MPH in Statistics | 1 | Contract |

| 6 | Call Center Operators | Health Officer, Nurse, Health Education | 45 | Contract |

| Total | 52 | |||

| S. N | Outbreak/Disaster | Period | Location of outbreak by regions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acute water diarrhea | Aug–Dec 2017 | Most of the regions in the country |

| 2 | Yellow Fever | 2018 | SNNPR region, Wolaita |

| 3 | Internal Displaced People | 2018, 2019 | Most of the regions in the country |

| 4 | EVD preparedness | 2019, 2021 | National level and point of entries |

| 5 | Cholera | July 2019 | Most of regions in the country |

| 6 | Vaccine derived polio virus outbreak response | 2019, 2020 | Somali, Oromo and SNNPR regions |

| 7 | COVID-19 | January 2020 – Ongoing (December 2023) | Nationwide |

| Drought and conflict induced humanitarian crisis | 2021, 2022 | Nationwide | |

| 8 | Monkeypox preparedness | 2022 | National level and point of entries |

| 9 | Multiple Public Health Emergencies (Malaria, Measles) | 2022 – 2023 | Nationwide |

| 10 | Marburg preparedness | 2023 | National level and point of entries |

| 11 | Cholera | March 2023 – Current ongoing (December 2023) | Nationwide |

References

- Ethiopian Public Health Institute. National Public Health Emergency Operations Center Handbook [Internet]. Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): Ethiopian Public Health Institute; 2022 Apr [cited 2025 Dec 17]. 92 p. Available from: https://ephi.gov.et/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/EPHI_cPHEM_EWISMD_PHEOC_Handbook_V1.pdf

- WHO Regional Office for Africa. Handbook for Public Health Emergency Operations Center Operations and Management [Internet]. Brazzaville (COG): WHO AFRO; 2021 [cited 2025 Dec 17]. 69 p. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/publications/handbook-public-health-emergency-operations-center-operations-and-management

- WHO. Handbook for developing a public health emergency operations centre: Part A: Policies, plans and procedures [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2018 Aug 24 [cited 2025 Dec 17]. 71 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/handbook-for-developing-a-public-health-emergency-operations-centre-part-a

- Ethiopian Public Health Institution Public Health Emergency Management Center. Public Health Emergency Management Guideline for Ethiopia [Internet]. 2nd ed. Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): Ethiopian Public Health Institution; 2022 Dec [cited 2025 Dec 17]. 163 p. Available from: https://eweb.ephi.gov.et/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/PHEM_Guideline_Second_Edition_2023.pdf

- WHO Regional Office for Africa. Public Health Emergency Operations Center (PHEOC) Legal Framework Guide: A Guide for the Development of a Legal Framework to Authorize the Establishment and Operationalization of a PHEOC [Internet]. Brazzaville (COG): WHO AFRO; 2021 [cited 2025 Dec 17]. 40 p. Available from: https://africacdc.org/download/public-health-emergency-operations-center-pheoc-legal-framework-guide/

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Emergency Operations Annual Report: saving lives and reducing suffering WHO’s work in emergency response operations in the WHO African Region in 2018 [Internet]. Congo (COG): WHO AFRO; 2020 Jan 13 [cited 2025 Dec 17]. 42 p. Available from: https://iris.who.int/items/40bd9c39-65cf-4895-864c-fae65c536051

- World Health Organization. A systematic review of public health emergency operations centres (EOC) [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2013 Dec 11 [cited 2025 Dec 17]. p. 11. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/a-systematic-review-of-public-health-emergency-operations-centres-(-eoc)

- Kamradt-Scott A. The international health regulations (2005): strengthening their effective implementation and utilisation. Int Organ Law Rev [Internet]. 2019 Dec 16 [cited 2025 Dec 17];16(2):242–71. Available from: https://brill.com/view/journals/iolr/16/2/article-p242_242.xml doi:10.1163/15723747-01602002

- CDC. Global Health Security Agenda: GHSA Emergency Operations Centers Action Package (GHSA Action Package Respond-1) [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; [Last reviewed 2023 Feb 2; cited 2025 Dec 17]. [about 6 screens]. Available from: https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/globalhealth/security/actionpackages/emergency_operations_centers.htm

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. National Action Plan for Health Security 2019-2023 [Internet]. Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia; 2019 Mar [cited 2025 Dec 17]. 120 p. Available from: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/eth210184.pdf

- Ethiopian Public Health Institute. Welcome to Ethiopian public health institute [Internet]. Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): Ethiopian Public Health Institute; c2024 [cited 2025 Dec 17]. Available from: https://ephi.gov.et/

- Ethiopian Ministry of Health. Health Sector Transformation Plan II: 2020/2021-2024/2025 (2013 EFY-2017 EFY) [Internet]. Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): Ethiopian Ministry of Health; 2021 Feb [cited 2025 Dec 17]. 116 p. Available from: https://extranet.who.int/countryplanningcycles/planning-cycle-files/health-sector-transformation-plan-ii-hstp-ii-202021-202425

- World Health Organization. Joint external evaluation of IHR core capacities of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia: Mission report March 2016 [Internet]. Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): WHO; 2017 Jan 27 [cited 2025 Dec 17]. 57 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HSE-GCR-2016.24

- Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI), Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Economist Impact. Global Health Security Index 2021: Country Score Justifications and References: Ethiopia [Internet]. Washington (DC): Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI), Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Economist Impact; 2021 [cited 2025 Dec 17]. 119 p. Available from: https://ghsindex.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ethiopia.pdf

- Embassy of Ethiopia. Overview about Ethiopia [Internet]. Washington (DC): Embassy of Ethiopia; [cited 2025 Dec 17]. [about 15 screens]. Available from: https://ethiopianembassy.org/overview-about-ethiopia/

- Dalglish SL, Khalid H, McMahon SA. Document analysis in health policy research: the READ approach. Health Policy Plan [Internet]. 2020 Nov 11 [cited 2025 Dec 17];35(10):1424–31. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/heapol/article/35/10/1424/5974853 doi:10.1093/heapol/czaa064

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Proclamation No. 1/1995 [Internet]. Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): Federal Negarit Gazeta; 1995 Aug 21 [cited 2025 Dec 17]. 38 p. Available from: https://www.ethiopianembassy.be/wp-content/uploads/Constitution-of-the-FDRE.pdf

- Ethiopian Public Health Institute. Public health emergency operation center assessment administration report [Internet]. Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): Ethiopian Public Health Institute; 2022 [cited 2025 Dec 17].

- World Health Organization. Public Health Emergency Operations Centre Network (EOC-NET) [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; c2025 [cited 2025 Dec 17]. Available from: https://www.who.int/groups/eoc-net

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. National Policy and Strategy on Disaster Risk Management [Internet]. Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia; 2013 Jul [cited 2025 Dec 17]. 21 p. Available from: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/eth149554.pdf

- The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Ethiopian Public Health Institute Establishment Council of Ministers Regulation No. 301/2013 [Internet]. Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): Federal Negarit Gazette; 2014 Jan 15 [cited 2025 Dec 17]. p. 7175-7182. Available from: https://bwcimplementation.org/sites/default/files/resource/ET_Ethiopian%20Public%20Health%20Institute%20%28EPHI%29%20Regulation%20301%3A2013.pdf

- Mastercard Foundation. Ethiopia officially launches a new digital platform that provides public health emergency-related information [Internet]. Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): Mastercard Foundation; 2022 Jun 13 [cited 2025 Dec 17]. [about 8 screens]. Available from: https://mastercardfdn.org/en/news/ethiopia-officially-launches-a-new-digital-platform-that-provides-public-health-emergency-related-information/

- Ethiopian Public Health Institute. Ethiopian Public Health Institute Administration Report [Internet]. Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): Ethiopian Public Health Institute; 2020 [cited 2025 Dec 17]. p.1–6.

- Lanyero B, Edea ZA, Musa EO, Watare SH, Mandalia ML, Livinus MC, Ebrahim FK, Girmay A, Bategereza AK, Abayneh A, Sambo BH, Abate E. Readiness and early response to COVID-19: achievements, challenges and lessons learnt in Ethiopia. BMJ Glob Health [Internet]. 2021 Jun 10 [cited 2025 Dec 17];6(6):e005581. Available from: https://gh.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005581 doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005581

- World Health Organization. Handbook for developing a public health emergency operations centre: Part C: Training and exercises [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2018 Aug 24 [cited 2025 Dec 17]. 56 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/handbook-for-developing-a-public-health-emergency-operations-centre-part-c

- Government of the United States of America. Strengthening Health Security Across the Globe: Progress and Impact of U.S. Government Investments in the Global Health Security Agenda – 2019 Annual Report [Internet]. Washington (DC): Government of the United States of America; 2020 [cited 2025 Dec 17]. 25 p. Available from: https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/GHSA_ProgressImpactFY19_final.pdf

- Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI), Ministry of Health, Ethiopia; and Countdown to 2030. Health Sector Transformation Plan-I (HSTP-I): 2015/16-2019/20: Endline Review Study [Internet]. Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): EPHI; 2022 Dec [cited 2025 Dec 17]. 91 p. Available from: https://ephi.gov.et/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2.-Ethiopia-Health-Sector-Transformation-Plan-I-2015-2020-Endline-Review.pdf