Research | Open Access | Volume 8 (3): Article 73 | Published: 12 Sep 2025

Assessment of the respiratory effects of exposure to wood particles among carpenters and associated risk factors in Senegal, 2021

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Tables

| Variables | Frequency | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of workers | 200 | |

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤19 | 35 | 17.5 |

| 20–29 | 53 | 26.5 |

| 30–39 | 59 | 29.5 |

| 40–49 | 36 | 18.0 |

| 50–59 | 12 | 6.0 |

| ≥60 | 5 | 2.5 |

| Age mean ± standard deviation | 32.43 ± 12.50 years | |

| Years of work (years) | ||

| ≤5 | 51 | 25.5 |

| 6–10 | 29 | 14.5 |

| 11–15 | 33 | 16.5 |

| 16–20 | 25 | 12.5 |

| 21–25 | 26 | 13.0 |

| ≥26 | 36 | 18.0 |

| Median years of work (Interquartile range) | 13.5 (IQR: 5–23) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 98 | 49.0 |

| Married | 95 | 47.5 |

| Divorced | 6 | 3.0 |

| Widowed | 1 | 0.5 |

| Level of education | ||

| None | 65 | 32.5 |

| Primary | 103 | 51.5 |

| Secondary | 30 | 15.0 |

| Post-secondary | 2 | 1.0 |

| Exposure duration (years) | ||

| <10 | 76 | 38.0 |

| ≥10 | 124 | 62.0 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Smokers | 18 | 9.0 |

| Non-Smokers | 182 | 91.0 |

| Carpentry shop type | ||

| Closed | 60 | 30.0 |

| Open | 140 | 70.0 |

Table 1: Description of sociodemographic characteristics, workplace conditions, and behavioural factors, N=200

| Disorders | Absolute frequency (n) | Relative frequency* (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | |||

| Chronic cough | 86 | 43.00 | 36.04 – 50.17 |

| Sputum | 97 | 48.50 | 41.39 – 55.65 |

| Fevers and chills | 74 | 37.00 | 30.30 – 44.09 |

| Shortness of breath | 72 | 36.00 | 29.35 – 43.07 |

| Whistling | 30 | 15.00 | 10.35 – 20.72 |

| Diseases | |||

| Rhinitis | 21 | 10.50 | 6.62 – 15.60 |

| Alveolite | 8 | 4.00 | 1.74 – 7.73 |

| Chronic bronchitis | 41 | 20.50 | 15.13 – 26.77 |

| Tuberculosis | 2 | 1.00 | 0.12 – 3.57 |

| Asthma | 8 | 4.00 | 1.74 – 7.73 |

*The total percentage exceeds 100% because this was a multiple response question.

Table 2: Respiratory disorders among Carpenters (N=200)

| Associated factors | Had Respiratory Disorder | No Respiratory Disorder | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure duration | |||||

| <10 years | 19 | 57 | Ref | ||

| ≥10 years | 58 | 66 | 2.74 | 1.43–5.22 | 0.0022 |

| Smoking status | |||||

| No | 67 | 115 | Ref | ||

| Yes | 10 | 8 | 1.87 | 0.68–5.17 | 0.2218 |

| Carpentry shop type | |||||

| Open | 58 | 82 | Ref | ||

| Closed | 19 | 41 | 1.84 | 0.94–3.59 | 0.0734 |

Table 3: Respiratory disorders and associated factors

Figures

Keywords

- Carpenters

- Wood Particles

- Exposure Duration

- Respiratory Diseases

- Senegal

Cheikh Mbengue1,2,3,&, Mamadou Diop2, Mamadou Fall3, Jean Kabore4, Djibril Barry5, Hermann Yoda5, Ghislain Sopoh6, Bouna Ndiaye7, Ibrahima Mamby Keita7, Kalidou Djibryl Sow7, Aminata Mbow Diokhane1, André Jacque Dioh1, Saliou Souare1, Pauline Kiswendsida Yanogo5,6,7,8, Nicolas Meda5,6,7,8

1Air Quality Management Center, Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development, Senegal, 2Laboratory of Oceantology and Geosciences, France, 3Laboratory of Toxicology and Hydrology, Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar, Senegal, 4Health Sciences Research Institute (IRSS), National Center for Scientific and Technological Research (CNRST), Burkina Faso, 5Burkina Field Epidemiology Training Program, Training and Research Unit in Health Science, Joseph KI-ZERBO University, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 6Regional Institute of Public Health (IRSP) of Ouidah – Slave Road, Ouidah – 01BP875RP – Cotonou – Benin, Buruli Ulcer Screening and Treatment Center of Allada – RNIE – BP 03 – Allada – Benin, 7Directorate General of Public Health, Ministry of Health and Social Action, Dakar, Senegal, 8Department of Public Health, Training and Research Unit in Health Science, Joseph KI-ZERBO University, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso

&Corresponding author: Cheikh Mbengue, Laboratory of Toxicology and Hydrology, Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar, Senegal, Email: mbenguech19@gmail.com, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0001-4484-4470

Received: 08 Jan 2025, Accepted: 11 Sep 2025, Published: 12 Sep 2025

Domain: Environmental Health

Keywords: Carpenters, Wood Particles, Exposure Duration, Respiratory Diseases, Senegal

©Cheikh Mbengue et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Cheikh Mbengue et al., Assessment of the respiratory effects of exposure to wood particles among carpenters and associated risk factors in Senegal, 2021. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8(3):73. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00015

Abstract

Introduction: Exposure to wood particles is frequently correlated with detrimental effects on the respiratory health of carpenters. This study examines the effects and risk factors associated with exposure to wood particles on respiratory function in informal woodworkers, such as carpenters in Senegal.

Methods: An analytical cross-sectional study was conducted from 02/08/2021 to 30/11/2021 with a four-stage random sampling of selected participants. Data collection required a questionnaire and a particule sampler. The data were processed using Epi-Info ®7.2.4.0 and Excel ®2019software for logistic regression.

Results: A total of 200 men with a mean age of 32.43±12.50 years were surveyed. The median years at work was 13.5 years (IQR: 5-23). The maximum mean particle concentrations above the occupational exposure limit value (OEL) in a closed carpentry shop (limited ventilation) and open workshops (ventilated) were 3.88 and 1.10 mg/m³ respectively. Respiratory disorders were cough (43.0%), sputum (48.5%), shortness of breath (36.0%), whistling (15.0%), chronic bronchitis (20.5%), rhinitis (10.5%), alveolitis (7.4.0 %), asthma (4.0%) and tuberculosis (1.0%). After adjustment to the smoking status variables and carpentry shop type, the duration of exposure to high levels of wood particles (aOR = 2.74, CI 95 %: 1.43-5.22, p = 0.0022) significantly increased the risk of respiratory disorders.

Conclusion: Mean exposure levels were above OEL, and the risk increased with duration of exposure to high levels of wood particles. Thus, we recommend methods for reducing and controlling exposure as well as raising awareness of respiratory health issues among carpenters.

Introduction

Exposure to wood particles is generally associated with a high prevalence of respiratory symptoms and diseases, including mucous membrane and nasal respiratory tract irritation, deterioration of lung function, asthma and allergies [1]. This exposure can lead to short- and medium-term diseases (rhinitis, eczema, conjunctivitis) and in the long term the onset of cancers of the nasal cavities, the ethmoid and other sinus of the face[2].Wood particles are also classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as proven carcinogens (Group 1) for humans, especially the nasopharynx, nasal cavities and facial sinuses [3].

In France, between 310,000 and 360,000 employees would be exposed to wood particles. They are the second leading cause of work-related cancers, 45% of nasal and sinus cancers of the face are attributed to occupational exposure to wood particles[2].

In other countries, the prevalence of respiratory symptoms among carpenters varies considerably. In Thailand and Iran the prevalence of reported respiratory symptoms ranges from 15.5% to 41%[1, 4]. Other studies in Poland and Denmark show no effect on pulmonary function[5, 6].

A study in Benin showed a higher prevalence of respiratory symptoms among carpenters (3.1% to 51.8%) compared to controls (0% to 8.3%)[7].In Nigeria, the prevalence of reported respiratory symptoms in wood sawmills varied depending on the symptoms: 5.3% and 50.2% for chest pain and microporosity production, respectively[8].

In Senegal, a study conducted in the Dakar region of 133 cabinetmakers and carpenters found high prevalences of respiratory symptoms and alteration in ventilatory function parameters. The dominant respiratory symptoms were nose irritation (84.38%), sneezing (84.38%) and coughing (72.18%). Subjects with ventilatory disorders were 36.17%[9].

Despite the potentially dangerous nature of occupational exposure to wood particles, there is a significant lack of knowledge and prevention of occupational risks factors in Senegal, hence the importance of this study in wood particles exposure in carpentry shops. To date, there is no study published in Senegal to identify the factors associated with respiratory diseases, the level and duration of particle exposure in carpenters. Therefore, this study aims to examine the effects and risk factors associated with the exposure to wood particles on respiratory function in informal carpenters in Senegal.

In the absence of national regulations on exposure to wood particles, data analysis was based on the European standard (Decree 2003-1254), which sets an Occupational Exposure Limit (OEL) of 1 mg/m³ over an 8-hour reference period[10].

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted in the administrative districts of Rufisque and Guediawaye, both in the Dakar Region. The region comprises a total of four administrative districts: Dakar, Guédiawaye, Rufisque, and Pikine. Rufisque, located to the west of Dakar, includes three borough municipalities and has a population of about 616,006 people across 372 km², with a density of 1,656 inhabitants per km². Guediawaye, located in the north of the Dakar Region, consists of four borough municipalities and has approximately 413,844 inhabitants over 13 km², with a density of 31,834 inhabitants per km². Carpentry activities in the informal sector are particularly dense in the above-described districts, with a variety of operations on wood, including sanding, cutting, and milling. The latter are carried out in artisanal shops that can be found both inside homes and close to the streets, and can be open or closed. Closed carpentry shops are found in most homes with a limited ventilation system. The open carpentry shops are in the open air, most of which are close to the streets.

Design of the study and population

This is a cross-sectional analytical study that took place from August 2nd to November 30th, 2021. The study population consisted of workers employed in carpentry shops.

Sample size estimation

The minimum sample size was estimated using Schwartz’s formula for proportions with a design effect[11]:

\( n = \frac{e \times \left( Z_{\alpha/2}^2 \times p(1 – p) \right)}{d^2} \)

Using Zα/2 = 1.96 (95% CI), p = 36.17% (prevalence of respiratory disorders in Dakar)[9], precision d = 9.5%, and a design effect of 2, we obtained n = 196.54. After adding 10% for non-response, the target sample size was 217 workers.

Selection of participants

Among the four administrative districts of the Dakar region,55 carpentry shops were selected in Rufisque and Guediawaye . Twenty-one carpentry shops in Rufisque and 21 in Guediawaye responded positively to our survey, resulting in a sample of 42 carpentry shops with a total workforce of 200 carpenters. All workers, employed continuously in a carpenter shop for at least one year in the said Rufisque and Guediawaye districts, were taken into account in the study. Workers with a history of chronic respiratory illness outside of work or those absent during the study period were not included to avoid biases, ensure valid results, and prevent misinterpretation of the findings.

A four-stage random sampling was used with at the: (i) 1st stage, a random draw without replacement of two districts out of four districts in the Dakar region, (ii) 2nd stage, a random draw without replacement of four municipalities in each district, (iii) 3rd stage, a random draw without replacement of (05) carpentry shops in each of the selected municipalities from a list of carpentry shops registered in each municipal office, (iv) 4th stage, a random draw without replacement of five eligible employees in each carpentry shop. Forty-two measurements were taken and analysed. The final study sample consisted of 42 carpentry shops with a total of 200 employees. Six workshops were randomly selected, three from each district, to compare the OEL (Occupational Exposure Limit) with the average concentrations of inhalable and respirable dust in closed and open carpentry shops.

Data collection

We administered a standardised questionnaire from the American Thoracic Society (Ferris 1978), adapted for sawmill work to collect information on sociodemographic, clinical symptoms and associated risk factors. A hand-held device (Aerocet®531S) was used to measure the concentrations of breathable (< 5 µm) and inhalable (> 5 µm) particles in carpentry shops over eight hours, corresponding to working hours. In each carpentry shop, one measurement over a duration of 8 hours was taken to obtain the average of the parameters.

Data measurement and analysis

The data were processed using Epi-info®7.2.4.0 and Excel® software. We conducted a data analysis that included both a descriptive and analytical component. A descriptive analysis of the data from the questionnaire was conducted to determine the characteristics of the study population. The duration of exposure is considered a categorical variable, distinguishing individuals with less than 10 years of exposure from those with 10 years or more. The categorical variables were expressed in number or percentage and quantitative variables expressed as means with their standard deviation or in medians with their interquartile interval. The study analytical component was based on a multiple linear regression modelling to determine the associations between the duration of exposure to airborne wood particles and the prevalence of respiratory disorders, taking into account potential confounding factors such as smoking status and carpentry shop type.

Ethical considerations

The study was an observational, non-interventional survey considered minimal risk. Approval for the conduct and defense of the research was obtained from the Faculty of Medicine, Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar. The Ministry of the Environment also approved the use of air pollution measuring devices of the Air Quality Management Center. Participation in this study was voluntary, and only participants who gave informed and voluntary oral consent were included.. The interviews were conducted in a place where confidentiality was ensured. Participants with respiratory pathologies were referred to the pneumology departments of Hôpital Principal de Dakar and Centre Hospitalier National Universitaire Fann-Dakar for adequate medical follow-up.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics, workplace conditions and behavioural factors

Our sample consisted of 200 participants and all were men. The mean age was 32.43 ±12.50 years. The median years at work was 13.5 (IQR: 5-23)with extremes ranging from1 to 47 years. The majority (75%) of workers had professional seniority under 23 years, had primary education (51.5%) and 32.5% did not attend school. The proportion of smokers was 9% (Table 1).

Concentration levels and trends of inhalable and breathable wood particles

The mean inhalable and respirable particle concentrations of the 42 carpentry shops were found to be 2.37 ±2.1 mg/m3 and 0.44 ±0.28 mg/m3 , respectively.

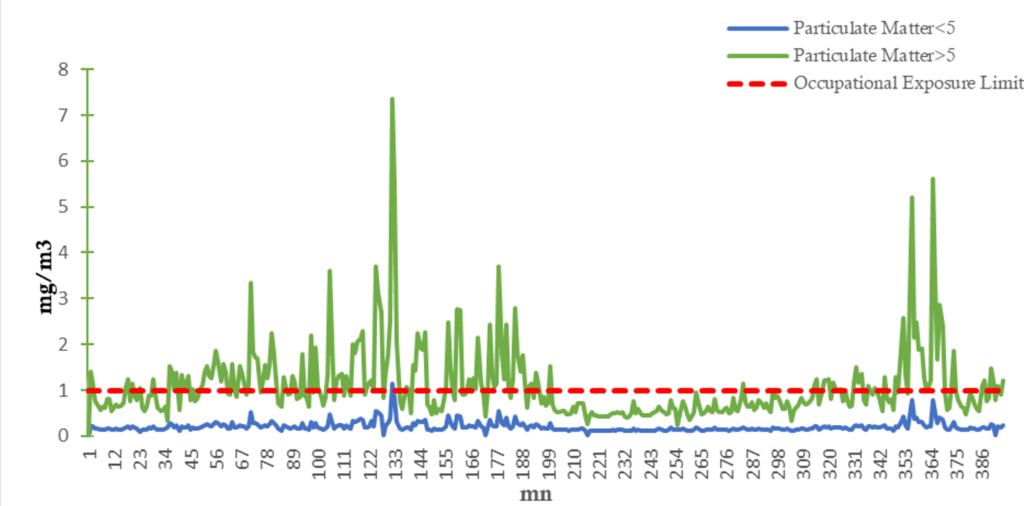

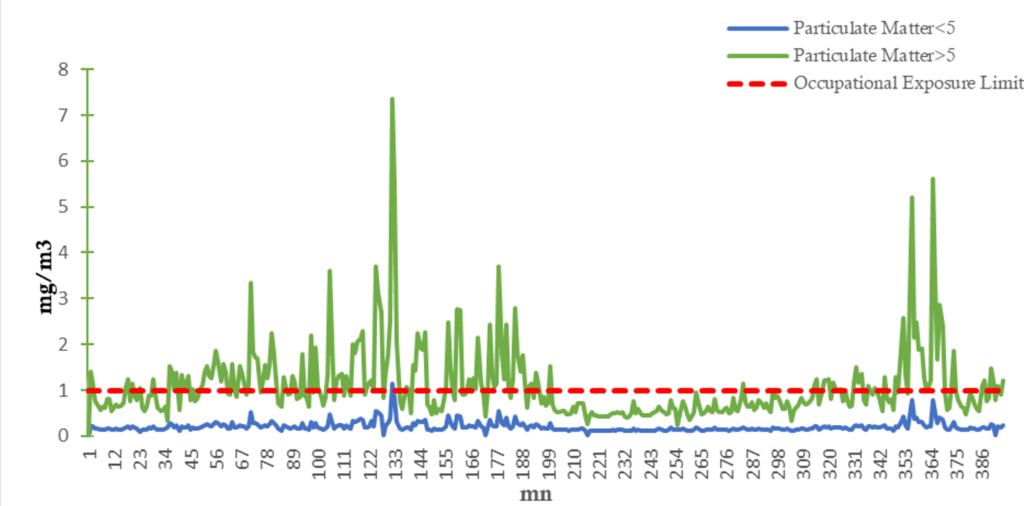

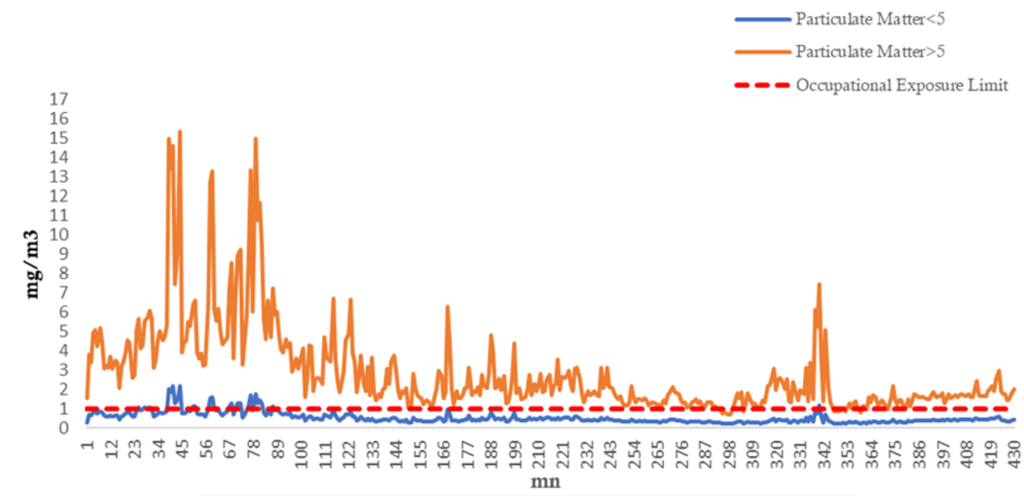

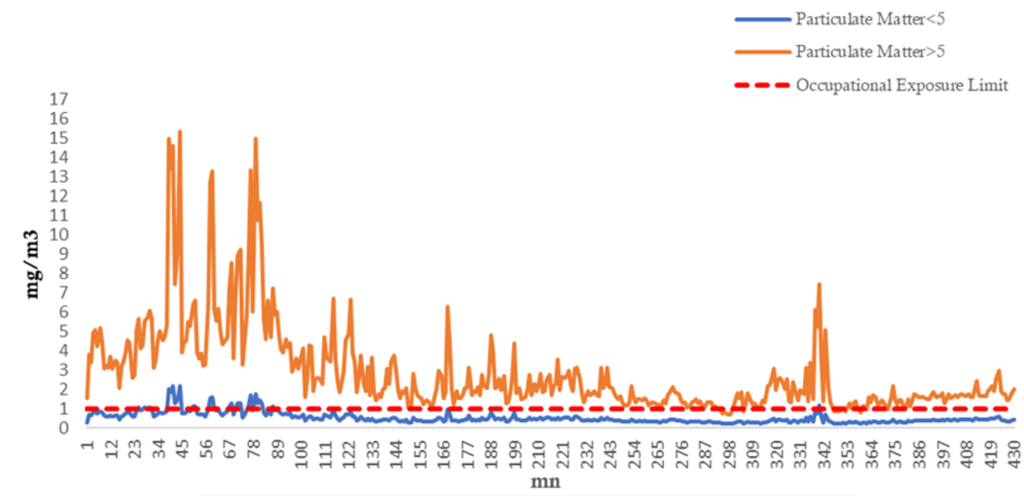

Daily mean concentrations of wood particles

Daily mean concentrations of inhalable and breathable particles were found to be higher in closed carpentry shops than open ones. Inhalable particle concentrations (> 5 µm) exceeded the daily occupational exposure limit value 1 mg/m3 for a reference period of 8 hours, whether in a closed or open environment.

Daily trends of wood particles in closed and open carpentry shops

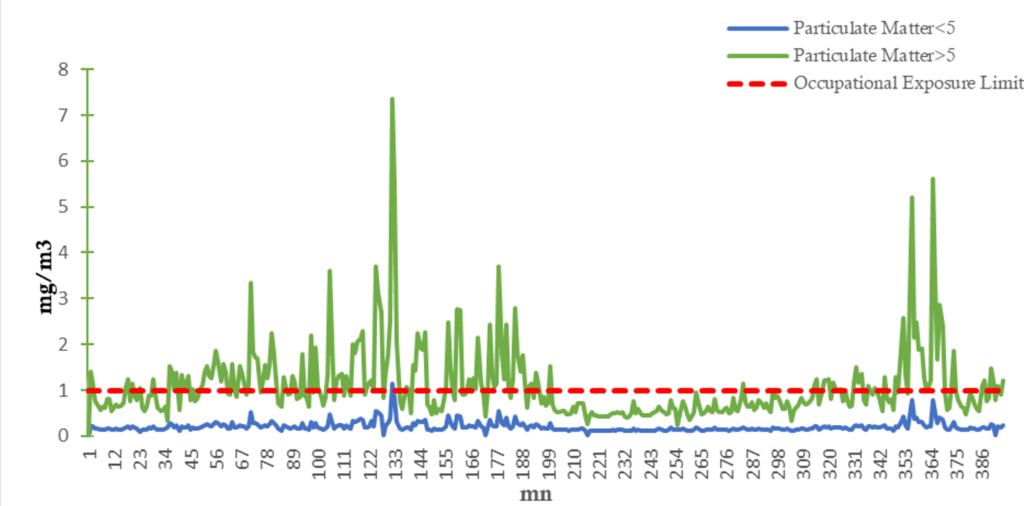

The maximum daily concentrations in open carpentry shops were observed during working hours (over an 8-hour period), and the highest concentrations were observed from 9am to 1pm with peaks of up to 7.3 mg/m3. These high particle emissions tend to dissipate during rest hours with air circulation contributing to the environment ventilation. Exceedances of the daily limit 1 mg/m3 over 8 hours were observed for inhalable particle (> 5 µm) (Figure 1).

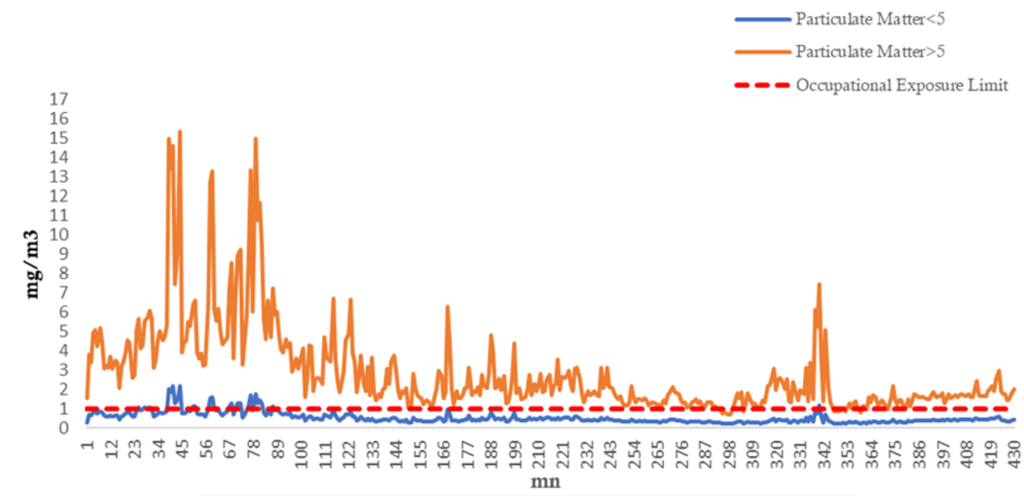

The maximum concentrations over 8 hours in closed carpentry shops, respectively for breathable and inhalable particles, 2.14 and 15.36 mg/m3, exceeded the 1 mg/m³ limit set by the European standard (Decree 2003-1254). These peak concentrations were observed during activity hours with low dispersal of wood particles due to the confined environment (Figure 2).

Respiratory health status of workers

Prevalence of respiratory symptoms: The results revealed that chronic coughs (43.00%), sputum (48.50%), fevers and chills (37.00%) and shortness of breath (36.00%) were the dominant respiratory symptoms. Whistling was the least common symptom in our subjects, with 15.00% of respondents.

Prevalence of respiratory diseases: Chronic bronchitis (20.50%) and rhinitis (10.50 %) were more common among those surveyed. Alveolitis, tuberculosis and asthma were the least common diseases (Table 2).

Prevalence of respiratory disorders: Out of the 200 participants, 77 had a respiratory disorder (either respiratory symptoms or respiratory disease), giving a prevalence of 38.5%.

Factors associated with respiratory disorders

After adjustment, the results indicate that prolonged exposure of 10 years or more to high levels of wood particles increases the risk of respiratory diseases (p= 0.0022, OR = 2.74, CI 95 % [1.43-5.22],), unlike smoking status and carpentry shop type. Indeed, workers with a longer duration of exposure had 2.74 times more risk of developing a respiratory disorder (Table 3).

Discussion

The average age of the carpenters (32.43 ± 1.19 years) and their median work experience (13.5 years, IQR: 5–23) indicate a young population but one that has already been exposed to wood particles for a long time, which could increase the risk of respiratory diseases. The low level of education (51.5% having not completed beyond primary school) may limit the adoption of preventive measures[12]. Finally, although the proportion of smokers is low (9%), smoking remains a potentially confounding factor to be considered in the analysis of respiratory effects related to occupational exposure. With regard to the factors explaining respiratory diseases in the study, only the duration of exposure was significantly associated with respiratory diseases. Indeed, a long exposure time increased the risk of respiratory diseases among workers in carpentry shops.

Prevalence of respiratory symptoms

The prevalence of all respiratory symptoms seems to be associated with exposure to wood particles. Chronic cough (43.00%), sputum (48.50%) are very common during work time, while shortness of breath (36.00%) whistles (15.00%), fevers and chills (37.00%) were also reported by participants. These symptoms tend to improve during weekends and leave periods. Other authors, such as K. HOSSEINI et al. [13] and BISLIMOVSKA et al. [14] were able to find a statistically significant association between exposure and the occurrence of respiratory symptoms.

The study also showed a higher prevalence of chronic bronchitis (20.50%) and rhinitis (10.50 %) compared to alveolitis, asthma and tuberculosis, which were 4.00%, 4.00% and 1.00% respectively. The very low percentage level of tuberculosis does not appear to be related to exposure to wood particles. The prevalence of chronic bronchitis and rhinitis appears to vary significantly with exposure to wood particles. In the study conducted by HESSEL et al.[15] in Canada, carpenters employed for more than 3 years had significantly 2.14 times more bronchitis than others.

In addition, according to JACOBSEN et al.[16], the cumulative incidence of chronic bronchitis was found to be associated with initial exposure to wood particles with a dose-response effect. However, according to some authors, chronic bronchitis can also be explained by smoking, whether in the present or the past[17].

In the LARAQUI et al. study[18], the prevalences of Rhinitis, asthma, and chronic bronchitis were 55.8%, 14.5% and 21.1% respectively with exposure to wood particles. The high prevalence of chronic symptoms and respiratory diseases found in our study may also be due to longer exposure to wood particles and a lack of training in occupational safety and health.

Duration of exposure to wood particles and respiratory diseases

The mean inhalable particle concentration in this study was 2.37 ±2.1 mg/m3 and the breathable particle concentration was 0.44 ±0.28 mg/m3. As well as the daily maximum mean particle concentrations were 3.88 mg/m³ in closed carpentry shops and 1.10 mg/m3 in open carpentry shops. Carpenters working in open shops were three times less exposed than those working in poorly ventilated places, such as a close one. These values exceeded the OEL (occupational exposure limit value of 1 mg/m3). These average concentrations exceedances have been reported by other authors, such as OSMAN & PALA (2.04 mg/m3), [19], Tobin EA et al. (1.39 mg/m3)[8], MAGAGNOTTI et al. (1.75 mg/m3) [20] but slightly lower than those found in closed carpentry shops. This can be explained, in part, by the fact that these carpentry shops had no ventilation system, and most of the workers were illiterate and were therefore unaware of the potential health effects of wood particles.

Exposure to wood particles causes both airway obstruction and extrinsic allergic alveolitis due to exposure to fungi and wood mould [21]. In the study, the risk after taking into account confounding factors (smoking and carpentry shop type), the odds ratio of respiratory disorders associated with duration of exposure to wood particles was positive and significantly high. According to VEDAL et al., the prevalence of these conditions increases with the intensity of wood dust exposure and the duration of exposure[22]. Therefore, the results of this study can be considered independent of smoking and could be attributed to exposure, although cause-and-effect relationships cannot be established from cross-sectional studies, such as this survey.

The use of the questionnaire has certain limitations, particularly the risk of bias introduced by the interviewer. To mitigate this, only interviewers with prior experience were selected and all interviewers were trained prior to data collection. The study findings cannot be generalized to the Dakar Region because they are non-representative of the region due to a problem encountered during the collection with the particle sampler, which led to a reduction in the sample size. Other factors, such as mask type, wood type, have not been included in this study, which may affect the outcome of interest. Future studies are recommended to be conducted on a larger scale and to consider different types of wood and personal protective equipment used, resources permitting.

Conclusion

The analysis of the data reveals an excessive dust level during working hours, with OEL exceedances more frequent in closed workshops than in open workshops. Exposure to extremely high levels of wood particles and its duration are associated with the prevalence of respiratory disorders. This dual qualification of both dose and duration of exposure is essential for understanding the risks.

Chronic cough, sputum, shortness of breath, bronchitis and rhinitis were the most common respiratory disorders. Prevention and awareness-raising could help to reduce exposure and prevent respiratory diseases among carpenters.

What is already known about the topic

- The prevalence of respiratory disorders and alterations in ventilatory function parameters.

- There is an increase in the prevalence of the condition with increasing levels of wood particles and duration of exposure.

What this study adds

- The estimation of wood particle exposure levels among carpenters in Senegal.

- Exposure to wood particles, regardless of smoking status and type of workshop (ventilated or poorly ventilated), constitutes a significant risk to the respiratory health of informal-sector carpenters in Senegal.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to some of the co-authors for their scientific supervision and mentorship, to the research assistants who participated in the data collection, and to the sawmill workers for their participation in the study. We also thank our dear masters (BFELTP) program coordinators for the quality of reception and supervision.

Authors´ contributions

Conceptualisation: C.M., M.D; methodology: C.M., M.D; software: C.M; validation: M.F; formal analysis: C.M, M.D, A.J.D, S.S; investigation: C.M.; resource: C.M; data retention: C.M., M.D; drafting – preparation of the original version: C.M, M.D, J.K, A.M.D, B.N, IMK , K.S; revision and editing: C.M, J.K, D.B, G.S; supervision M.F, P.K, N.M; acquisition of funds: P.K, N.M.

| Variables | Frequency | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of workers | 200 | |

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤19 | 35 | 17.5 |

| 20–29 | 53 | 26.5 |

| 30–39 | 59 | 29.5 |

| 40–49 | 36 | 18.0 |

| 50–59 | 12 | 6.0 |

| ≥60 | 5 | 2.5 |

| Age mean ± standard deviation | 32.43 ± 12.50 years | |

| Years of work (years) | ||

| ≤5 | 51 | 25.5 |

| 6–10 | 29 | 14.5 |

| 11–15 | 33 | 16.5 |

| 16–20 | 25 | 12.5 |

| 21–25 | 26 | 13.0 |

| ≥26 | 36 | 18.0 |

| Median years of work (Interquartile range) | 13.5 (IQR: 5–23) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 98 | 49.0 |

| Married | 95 | 47.5 |

| Divorced | 6 | 3.0 |

| Widowed | 1 | 0.5 |

| Level of education | ||

| None | 65 | 32.5 |

| Primary | 103 | 51.5 |

| Secondary | 30 | 15.0 |

| Post-secondary | 2 | 1.0 |

| Exposure duration (years) | ||

| <10 | 76 | 38.0 |

| ≥10 | 124 | 62.0 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Smokers | 18 | 9.0 |

| Non-Smokers | 182 | 91.0 |

| Carpentry shop type | ||

| Closed | 60 | 30.0 |

| Open | 140 | 70.0 |

| Disorders | Absolute frequency (n) | Relative frequency* (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | |||

| Chronic cough | 86 | 43.00 | 36.04 – 50.17 |

| Sputum | 97 | 48.50 | 41.39 – 55.65 |

| Fevers and chills | 74 | 37.00 | 30.30 – 44.09 |

| Shortness of breath | 72 | 36.00 | 29.35 – 43.07 |

| Whistling | 30 | 15.00 | 10.35 – 20.72 |

| Diseases | |||

| Rhinitis | 21 | 10.50 | 6.62 – 15.60 |

| Alveolite | 8 | 4.00 | 1.74 – 7.73 |

| Chronic bronchitis | 41 | 20.50 | 15.13 – 26.77 |

| Tuberculosis | 2 | 1.00 | 0.12 – 3.57 |

| Asthma | 8 | 4.00 | 1.74 – 7.73 |

| Associated factors | Had Respiratory Disorder | No Respiratory Disorder | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure duration | |||||

| <10 years | 19 | 57 | Ref | ||

| ≥10 years | 58 | 66 | 2.74 | 1.43–5.22 | 0.0022 |

| Smoking status | |||||

| No | 67 | 115 | Ref | ||

| Yes | 10 | 8 | 1.87 | 0.68–5.17 | 0.2218 |

| Carpentry shop type | |||||

| Open | 58 | 82 | Ref | ||

| Closed | 19 | 41 | 1.84 | 0.94–3.59 | 0.0734 |

References

- Douwes J, McLean D, Slater T, Pearce N. Asthma and other respiratory symptoms in New Zealand pine processing sawmill workers. Am J Ind Med [Internet]. 2001 May;39(6):608-15 [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ajim.1060 https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.1060. Subscription or purchase required to view full text.

- Environmental Cancer Prevention Department, Léon Bérard Center. Poussières de bois et risque de cancer [Internet]. Lyon (FR): Environmental Cancer Prevention Department, Léon Bérard Center; [updated 2025 Apr 14; cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: https://www.cancer-environnement.fr/333-Poussieres-de-bois.ce.aspx.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Arsenic, metals, fibres, and dusts. Lyon (FR): IARC; 2012. 501 p. (IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans; vol 100 C) [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: https://publications.iarc.who.int/_publications/media/download/6143/ef2dcba35d394362f6f5346d042bd48e5792ded3.pdf. Download PDF to view full text.

- World Health Organization, International Labour Organization. WHO/ILO joint estimates of the work-related burden of disease and injury, 2000–2016 [Internet]. Geneva (CH): WHO/ILO; 2021 Sep. 79 p. [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_dialogue/@lab_admin/documents/publication/wcms_819788.pdf. Download PDF to view full text.

- Ayars GH, Altman LC, Frazier CE, Chi EY. The toxicity of constituents of cedar and pine woods to pulmonary epithelium. J Allergy Clin Immunol [Internet]. 1989 Mar;83(3):610-8 [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0091674989900730 https://doi.org/10.1016/0091-6749(89)90073-0.

- Azees AS, Yunusa UE, Abdulfattah I, Ezenwoko ZA, Temitayo-Oboh AO, Abiodun RS, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with respiratory symptoms among sawmill workers in Sokoto State, northwest Nigeria. J Community Med Prim Health Care [Internet]. 2023 Apr;35(1):74-84 [cited 2025 Sep 14]. Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/jcmphc/article/view/245160.

- Ekaete T, Ediagbona TF. Occupational exposure to wood dust and respiratory health status of sawmill workers in south-south Nigeria. J Pollut Eff Cont [Internet]. 2016 Feb;4(1):154 [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: http://www.esciencecentral.org/journals/occupational-exposure-to-wood-dust-and-respiratory-health-status-of-sawmill-workers-in-southsouth-nigeria-2375-4397-1000154.php?aid=68456 http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/2375-4397.1000154.

- Mbengue A, Sow A, Houndjo S, Diaw M, Coly M, Fall P, et al. Assessment of ventilatory disorders in artisans exposed to wood dust. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol [Internet]. 2018;8(12):1641-6 [cited 2025 Sep 14]. Available from: https://ejmanager.com/fulltextpdf.php?mno=299342.

- Légifrance (France). Decree no. 2003-1254 of December 23, 2003 relating to the prevention of chemical risks and amending the labor code (second part: Decrees in the Council of State) [Internet]. Paris (FR): Légifrance; 2003 Dec 28 [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFARTI000001665766. French.

- Hsieh FY, Liu AA. Adequacy of sample size in health studies. Stat Med [Internet]. 1990 Nov;9(11):1382 [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/sim.4780091115 https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.4780091115.

- Geleta DH, Alemayehu M, Asrade G, Mekonnen TH. Low levels of knowledge and practice of occupational hazards among flower farm workers in southwest Shewa zone, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional analysis. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Jan;21(1):232 [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-021-10254-5 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10254-5.

- Hosseini KD, Malekshahi Nejad V, Sun H, Hosseini HK, Adeli SH, Wang T. Prevalence of respiratory symptoms and spirometric changes among non-smoker male wood workers. Larcombe A, editor. PLoS One [Internet]. 2020 Mar;15(3):e0224860 [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224860 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224860.

- Bislimovska D, Petrovska S, Minov J. Respiratory symptoms and lung function in never-smoking male workers exposed to hardwood dust. Open Access Maced J Med Sci [Internet]. 2015 Jul;3(3):500-5 [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: https://oamjms.eu/index.php/mjms/article/view/oamjms.2015.086 https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2015.086.

- Hessel PA, Herbert FA, Melenka LS, Yoshida K, Michaelchuk D, Nakaza M. Lung health in sawmill workers exposed to pine and spruce. Chest [Internet]. 1995 Sep;108(3):642-6 [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0012369216342088 https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.108.3.642. Subscription or purchase required to view full text.

- Jacobsen G, Schlünssen V, Schaumburg I, Sigsgaard T. Increased incidence of respiratory symptoms among female woodworkers exposed to dry wood. Eur Respir J [Internet]. 2009 May;33(6):1268-76 [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: https://publications.ersnet.org/lookup/doi/10.1183/09031936.00048208 https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00048208.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 2020 report [Internet]. Deer Park (IL): GOLD; 2020. 125 p. [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/GOLD-2020-REPORT-ver1.0wms.pdf. Download PDF to view full text.

- Laraqui Hossini CH, Laraqui Hossini O, Rahhali AE, Verger C, Tripodi D, Caubet A, et al. Respiratory risk in carpenters and cabinet makers. Rev Mal Respir [Internet]. 2001 Dec;18(6 Pt 1):615-22 [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11924182/. French. Subscription or purchase required to view full text.

- Osman E, Pala K. Occupational exposure to wood dust and health effects on the respiratory system in a minor industrial estate in Bursa/Turkey. Int J Occup Med Environ Health [Internet]. 2009;22(1):43-50 [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: http://www.imp.lodz.pl/home_en/publishing_office/journals_/_ijomeh/&articleId=21067&l=EN https://doi.org/10.2478/v10001-009-0008-5.

- Determining the exposure of chipper operators to inhalable wood dust. Ann Occup Hyg [Internet]. 2013 Jan;57(6):784-92 [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/annweh/article-abstract/57/6/784/148984?redirectedFrom=fulltext&login=false https://doi.org/10.1093/annhyg/mes112. Subscription or purchase required to view full text.

- Carosso A, Ruffino C, Bugiani M. Respiratory diseases in wood workers. Occup Environ Med [Internet]. 1987 Jan;44(1):53-6 [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: https://oem.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/oem.44.1.53 https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.44.1.53. Subscription or purchase required to view full text.

- Vedal S, Chan-Yeung M, Enarson D, Fera T, MacLean L, Tse KS, et al. Symptoms and pulmonary function in western red cedar workers related to duration of employment and dust exposure. Arch Environ Health [Internet]. 1986 May-Jun;41(3):179-83 [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00039896.1986.9935774 https://doi.org/10.1080/00039896.1986.9935774.