Research | Open Access | Volume 8 (3): Article 78 | Published: 23 Sep 2025

Caregivers’ readiness and willingness to accept malaria vaccine for children under five years in Gombe State, Nigeria

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Tables

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of participants, N=293

| Variable | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18-25 | 105 | 35.8 |

| 26-35 | 126 | 43.0 |

| 36-45 | 43 | 14.7 |

| 46 and above | 19 | 6.5 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 62 | 21.2 |

| Female | 231 | 78.8 |

| Education level | ||

| No formal education | 47 | 16.0 |

| Primary education | 31 | 10.6 |

| Secondary education | 111 | 37.9 |

| Tertiary education | 104 | 35.5 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 23 | 7.8 |

| Married | 262 | 89.4 |

| Divorced | 5 | 1.7 |

| Widowed | 3 | 1.0 |

| Occupation | ||

| Unemployed | 150 | 51.2 |

| Farmer | 17 | 5.8 |

| Trader | 65 | 22.2 |

| Civil servant | 46 | 15.7 |

| Artisan | 15 | 5.1 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||

| Lower class | 195 | 66.6 |

| Middle class | 90 | 30.7 |

| Upper class | 8 | 2.7 |

| Number of children under five per caregiver | ||

| 1-2 | 183 | 62.5 |

| 3-4 | 74 | 25.2 |

| > 5 | 36 | 12.3 |

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of participants, N=293

Table 2: Knowledge of Malaria and its vaccine, N=293

| Question | Response | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Are you aware of malaria and its effects on children under five? | Yes | 257 | 87.7 |

| No | 36 | 12.3 | |

| How is malaria transmitted? | Mosquito bites | 259 | 88.4 |

| Contaminated food/water | 8 | 2.7 | |

| Witchcraft | 3 | 1.0 | |

| Don’t know | 23 | 7.8 | |

| Are you aware of any vaccine that is used to prevent diseases? | Yes | 227 | 77.5 |

| No | 66 | 22.5 | |

| Have you heard about the Malaria vaccine? | Yes | 135 | 46.1 |

| No | 158 | 53.9 | |

| Are you aware that malaria vaccine has been introduced in some States in Nigeria? | Yes | 92 | 31.4 |

| No | 201 | 68.6 |

Table 2: Knowledge of malaria and its vaccine, N=293

Table 3: Participants’ Beliefs and Perceptions About Vaccines and the Malaria Vaccine, N=293

| Questions | Responses | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| How important do you think vaccines are for preventing diseases in children? | Very important | 204 | 69.6 |

| Important | 78 | 26.6 | |

| Not important | 11 | 3.8 | |

| How confident are you in the malaria vaccine’s ability to protect your child? | Very confident | 214 | 73.0 |

| Somewhat confident | 32 | 10.9 | |

| Neutral | 31 | 10.6 | |

| Not confident | 16 | 5.5 | |

| Do you believe the malaria vaccine will help reduce malaria in children? | Strongly agree | 143 | 48.8 |

| Agree | 117 | 39.9 | |

| Neutral | 23 | 7.9 | |

| Disagree | 2 | 0.7 | |

| Strongly disagree | 8 | 2.7 |

Table 3: Participants’ Beliefs and Perceptions About Vaccines and the Malaria Vaccine, N=293

Table 4: Social Influences, Trust, and Willingness to Accept the Malaria Vaccine, N=293

| Questions | Responses | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Would the opinions of friends, family, or community leaders influence your decisions to vaccinate your child? | Yes | 197 | 67.2 |

| No | 96 | 32.8 | |

| Would you be willing to vaccinate your child against malaria? | Yes | 271 | 92.5 |

| No | 22 | 7.5 | |

| Do you trust healthcare workers to provide accurate information about vaccines? | Yes | 268 | 91.5 |

| No | 25 | 8.5 |

Table 4: Social Influences, Trust, and Willingness to Accept the Malaria Vaccine, N=293

Table 5: Concerns, Preferred Timing, and Motivating Factors for Malaria Vaccination, N=293

| Questions | Responses | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| When would you prefer your child to receive the malaria vaccine? | During routine immunisation | 150 | 51.2 |

| At a specialised vaccination campaign | 31 | 10.6 | |

| Anytime it is available | 112 | 38.2 | |

| What mode of delivery of the vaccine will you prefer? | Health facilities | 244 | 83.3 |

| Mobile vaccination units | 12 | 4.1 | |

| Door-to-door campaigns | 37 | 12.6 | |

| What factors would encourage you to vaccinate your child? | Assurance of safety and effectiveness | 214 | 73.0 |

| Free or affordable vaccines | 32 | 10.9 | |

| Access to vaccination services | 12 | 4.1 | |

| Community campaigns and education | 28 | 9.6 | |

| Incentives | 7 | 2.4 | |

| How can the community be better engaged to improve vaccine acceptance? | Health education programs | 195 | 66.6 |

| Involvement of community and religious leaders | 75 | 25.6 | |

| Mobile vaccination units | 17 | 5.8 | |

| Other | 6 | 2.0 |

Table 5: Concerns, Preferred Timing, and Motivating Factors for Malaria Vaccination, N=293

| Variable | Yes N=271 n (%) | No N=22 n (%) | χ², p-value | Crude OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 18–25 | 97 (35.8) | 8 (36.4) | 48.746, <0.001 | 10.9 (3.44–34.59) | <0.001 | 25.5 (4.45–145.9) | <0.001 |

| 26–35 | 123 (45.4) | 3 (13.6) | 36.9 (8.60–158.4) | <0.001 | 56.5 (8.23–387.4) | <0.001 | |

| 36–45 | 41 (15.1) | 2 (9.7) | 18.5 (3.44–99.1) | 0.001 | 27.3 (3.03–246.5) | 0.003 | |

| 46+ | 11 (3.7) | 9 (40.9) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 57 (21.0) | 5 (22.7) | 0.35, 0.852 | 0.91 (0.32–2.56) | 0.852 | 1.91 (0.33–11.1) | 0.470 |

| Female | 214 (79.0) | 17 (77.3) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Level of Education | |||||||

| None | 36 (13.3) | 11 (50.0) | 21.059, <0.001 | 0.10 (0.03–0.37) | 0.001 | 0.13 (0.03–0.67) | 0.014 |

| Primary | 29 (10.7) | 2 (9.1) | 0.43 (0.07–2.70) | 0.369 | 0.36 (0.04–3.19) | 0.355 | |

| Secondary | 105 (38.7) | 6 (27.3) | 0.52 (0.13–2.14) | 0.364 | 0.28 (0.05–1.44) | 0.127 | |

| Tertiary (Ref) | 101 (37.3) | 3 (13.6) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Marital Status | |||||||

| Single | 22 (8.1) | 1 (4.5) | 1.704, 0.790 | ||||

| Married | 242 (89.3) | 20 (90.9) | |||||

| Widowed | 4 (1.5) | 1 (4.5) | |||||

| Divorced | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | |||||

| Married vs Unmarried | Married: 242 (89.3) | 20 (90.9) | 0.56, 0.813 | 0.83 (0.19–3.75) | 0.814 | 1.95 (0.33–11.5) | 0.462 |

| Occupation | |||||||

| Unemployed | 135 (49.8) | 15 (68.2) | 12.565, 0.014 | ||||

| Farmer | 13 (4.8) | 4 (18.2) | |||||

| Trader | 63 (23.2) | 2 (9.1) | |||||

| Civil servant | 45 (16.6) | 1 (4.5) | |||||

| Artisan | 15 (5.5) | 0 (0.0) | |||||

| Employment status | |||||||

| Unemployed | 135 (49.8) | 15 (68.2) | 2.747, 0.097 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Employed | 136 (50.2) | 7 (31.8) | 2.16 (0.85–5.46) | 0.104 | 2.22 (0.64–7.73) | 0.208 | |

| Socioeconomic status | |||||||

| Lower class | 179 (66.1) | 16 (72.7) | 0.878, 0.645 | ||||

| Middle class | 84 (31.0) | 6 (27.3) | |||||

| Upper class | 8 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||||

| Low vs Middle/High | 179 (66.1) | 16 (72.7) | 0.407, 0.523 | 1.73 (0.52–3.62) | 0.525 | 0.64 (0.17–2.38) | 0.508 |

| Number of under-five children in household | |||||||

| 1–2 | 170 (62.7) | 13 (59.1) | 0.646, 0.724 | 0.77 (0.17–3.57) | 0.737 | 0.25 (0.03–1.82) | 0.170 |

| 3–4 | 67 (24.7) | 7 (31.8) | 0.56 (0.11–2.86) | 0.488 | 0.36 (0.05–2.86) | 0.336 | |

| >5 | 34 (12.5) | 2 (9.1) | Ref | Ref | |||

Table 6: Factors associated with willingness to vaccinate under-five children with Malaria vaccine, N=293

Figures

Keywords

- Malaria vaccine

- Caregiver acceptance

- Vaccine readiness

- Gombe

Ibrahim Adamu1,2,&, Ibrahim Ibrahim Muhammad3, Imrana Bojude Alhassan4, Adamu Bukar Ali5, Bilyaminu Reme Hussaini6, Farouk Ismail Umar3, Musa Wade Mahdi7, Modu Chinta3, Abdulwahab Aliyu8, Raymond Dankoli9

1Department of Medicine, Infectious Diseases Unit, Federal Teaching Hospital Gombe, Gombe State, Nigeria, 2Department of Medicine, Gombe State University, Gombe State, Nigeria, 3World Health Organization, Gombe Field Office, Gombe State, Nigeria, 4National AIDS and STDs Control Programme (NASCP), Federal Ministry of Health, Nigeria, 5Taraba State Health Services Management Board, Jalingo, Nigeria, 6Department of Paediatrics, Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Teaching Hospital, Bauchi, Nigeria, 7World Health Organization, Jos Field Office, Plateau State, Nigeria, 8Department of Pharmaceutical Microbiology, Gombe State University, Gombe State, Nigeria, 9World Health Organization, Ghana Country Office

&Corresponding author: Ibrahim Adamu, Department of Medicine, Infectious Diseases Unit, Federal Teaching Hospital Gombe, Gombe State, Nigeria, Email: ibbomala@gsu.edu.ng ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-8315-2462

Received: 24 May 2025, Accepted: 18 Sep 2025, Published: 23 Sep 2025

Domain: Vaccine Preventable Diseases, Malaria Control

Keywords: Malaria vaccine, caregiver acceptance, vaccine readiness, Gombe

©Ibrahim Adamu et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Ibrahim Adamu et al., Caregivers’ readiness and willingness to accept malaria vaccine for children under five years in Gombe State, Nigeria. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8(3):78. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00129

Abstract

Introduction: Malaria remains a leading public health challenge in sub-Saharan Africa, with Nigeria accounting for the highest global burden, particularly among children under five. Despite ongoing prevention efforts, the disease continues to cause significant morbidity and mortality. The introduction of malaria vaccines; RTS, S/AS01 and R21/Matrix-M offers a promising tool to reduce this burden. However, the success of vaccination efforts depends on community acceptance, especially in non-pilot areas like Gombe Local Government Area (LGA) in Gombe State. This study assessed caregiver readiness and willingness to accept the malaria vaccine for children under five in Gombe LGA and explored factors influencing vaccine acceptance.

Methods: A mixed-methods cross-sectional study was conducted among 293 caregivers using consecutive sampling from primary healthcare settings. Data were collected using semi-structured questionnaires capturing demographic information, malaria vaccine knowledge, and willingness to vaccinate. In addition, all participants were asked a single open-ended question on strategies to improve trust and vaccine acceptance. Quantitative data were analysed using SPSS version 25, with descriptive statistics summarising caregiver characteristics and logistic regression identifying predictors of vaccine willingness. Qualitative responses were analysed using an inductive thematic approach to provide contextual insights.

Results: The majority of caregivers were female (78.8%), married (89.4%), and educated to at least secondary level (73.4%). While awareness of malaria was high (87.7%), only 46.1% had heard of the malaria vaccine, and just 31.4% were aware of its introduction in Nigeria. Nevertheless, 92.5% expressed willingness to vaccinate their children, with 73.0% confident in the vaccine’s protective benefit. Factors significantly associated with willingness included caregiver age and education. Health facilities were the most preferred place for vaccine access (83.3%), with 51.2% of caregivers favouring routine immunisation visits. Meanwhile, healthcare workers were identified as the most trusted source of vaccine information (91.5%). Key motivators for vaccine acceptance included trust in safety and efficacy (73.0%), affordability (10.9%), and health education (9.6%). Caregivers recommended enhancing vaccine uptake through improved community engagement, clear communication, qualified personnel, and government transparency.

Conclusion: Despite low awareness of the malaria vaccine, caregiver willingness to vaccinate in Gombe LGA is high. Addressing knowledge gaps through education, building trust in healthcare systems, and ensuring equitable access will be critical for successful vaccine rollout in the region.

Introduction

Malaria remains a significant public health challenge in sub-Saharan Africa, with Nigeria bearing the highest burden of cases, accounting for 27% of cases globally [1]. In 2023, there were 263 million malaria cases in the world, which resulted in 597,000 deaths mainly in 83 countries [2]. Most malaria cases (94%) occur in the World Health Organization (WHO) African Region, which also accounts for 95% of malaria-related deaths, with 76% of these fatalities occurring in children under five years of age [3]. In 2021, Nigeria accounted for 27% of global malaria cases, with over 68 million infections and more than 194,000 deaths, the highest number worldwide, representing about 31% of all malaria-related fatalities globally. Notably, around 80% of these deaths occurred in children under five years of age [1]. Despite concerted efforts to combat malaria through the distribution of Long-Lasting Insecticide-Treated Nets and Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention interventions, the goal of a malaria-free Nigeria remains elusive. The national average malaria prevalence among children under five was 22%, but in Kebbi State, it soared to an alarming 49% [4]. Vaccination is widely regarded as the most effective intervention for reducing the mortality and morbidity associated with infectious diseases[5]. In 2021, the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommended the RTS, S/AS01 (RTS, S) malaria vaccine for children in sub-Saharan Africa and other regions with moderate to high transmission of Plasmodium falciparum malaria[6]. In 2023, the WHO approved a second vaccine, the R21/Matrix-M, for children in malaria-endemic countries [7]. These vaccines have been shown to significantly reduce the incidence of uncomplicated malaria by 40%, severe malaria by 30%, and malaria-related mortality by 13% [8].

The R21 malaria vaccine pilot intervention has been launched in two high-prevalence states in Nigeria, Kebbi and Bayelsa, which will be administered in four doses to children under one year of age and integrated into the routine immunisation schedule [4].

The success of malaria vaccination programs depends significantly on community acceptability, which hinges on two distinct factors: Caregivers’ readiness (knowledge and informational preparedness regarding the malaria vaccine and willingness (attitudinal motivation and intention to vaccinate). Yet, limited data exist on these constructs in non-pilot areas like Gombe State. As such, this setting represents a crucial opportunity for early planning, where understanding these dynamics can ensure a smooth future vaccine introduction.

Although Gombe State is not among the initial pilot sites for malaria vaccine introduction, it offers a valuable context for examining vaccine acceptability. Situated in Nigeria’s northeast, which bears the second-highest malaria burden among the country’s six geopolitical zones, Gombe remains significantly affected by malaria-related morbidity and mortality in under-five children [9]. The state also benefits from a functional routine immunisation system, making it a feasible platform for integrating new vaccines. Furthermore, its sociocultural and health system characteristics are broadly representative of many non-pilot states in northern Nigeria, ensuring that insights generated from this study will not only inform state-level planning but also contribute to broader national strategies for malaria vaccine scale-up.

This study seeks to assess the readiness and willingness of caregivers in Gombe LGA to accept the malaria vaccine for their under-five children. It also aims to identify the factors shaping these constructs and to generate context-specific recommendations that can guide effective community engagement and support the state’s future vaccine rollout.

Methods

Study Design

This study employed a concurrent mixed-methods design (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2017; Creswell, 2009) [10,11]. Specifically, we adopted an embedded design model, in which qualitative data (from open-ended survey questions) were nested within a primary quantitative survey instrument. The qualitative responses were systematically analysed thematically and integrated with the quantitative results to provide explanatory depth and contextual understanding.

Study Area

The study was conducted in Primary Health Care Centres (PHCs) within Gombe Local Government Area (LGA), Gombe State, Nigeria. PHCs serve as the initial point of contact for caregivers seeking medical attention for their children. Gombe LGA has at least one PHC distributed across its eleven wards [12]. The estimated population of Gombe LGA is approximately 446,800, with children under five constituting about 45% of this population [13].

Study Population

Participants included caregivers (e.g., parents or guardians) of children under five years who attended PHCs within Gombe LGA.

Inclusion Criteria

- Caregivers of children under five years of age attending routine immunisation clinics, outpatient clinics, paediatric wards, or emergency departments at PHCs in Gombe LGA.

- Caregivers who provided informed consent to participate.

Exclusion Criteria

- Caregivers who were healthcare professionals.

- Caregivers who declined to provide informed consent.

Recruitment Strategy

Participants were recruited at various PHC service points:

- Routine immunisation sites during scheduled immunisation days

- Outpatient clinics

- Paediatric wards during hospital admissions

- Emergency departments

Trained research assistants explained the study purpose and obtained written informed consent before enrolment.

Sample Size

The minimum required sample size was calculated using the formula [14] for estimating a population proportion:

\( n = \frac{Z^2 \cdot P(1 – P)}{d^2} \)

where Z is the standard normal deviate at a 95% confidence level (1.96), P is the estimated prevalence (22% for malaria among children aged 6–59 months in Nigeria [4,15], and d is the margin of error (5%). This yielded a minimum sample size of 264. However, additional participants were recruited, bringing the final evaluated sample size to 293.

Sampling method

The study employed a consecutive sampling strategy to ensure representation from all primary health care (PHC) facilities in Gombe LGA. All eleven PHCs within the LGA were included. One trained research assistant was assigned to each facility. Research assistants approached all caregivers attending the facility who met the inclusion criteria and obtained informed consent before participation. Recruitment was conducted consecutively at each facility until the overall sample size of 293 participants was reached. This approach ensured that all the PHCs were represented and that all eligible and consenting caregivers within the study period had an equal opportunity to participate.

For the qualitative component, all the 293 survey participants were asked a single open-ended question to elicit rich, contextual insights. This approach ensured the qualitative data were derived from the same representative sample, capturing a wide range of perspectives.

Definition of key concepts

The successful introduction of a new health intervention hinges not only on its clinical efficacy but also on the community’s acceptance of it. This study assessed two critical, sequential precursors to vaccine uptake among caregivers of children under five: readiness and willingness. These constructs, informed by models of vaccine hesitancy by Larson et al., 2015 [16], were operationalised and measured through our structured survey to capture the cognitive and behavioural intentions that precede the actual act of vaccination.

Readiness was defined as the caregiver’s knowledge and awareness regarding the malaria vaccine. It encompasses an individual’s informational preparedness, which is a prerequisite for making an informed health decision. A caregiver who is “ready” has been exposed to essential information and possesses the basic understanding required to contemplate vaccination. This construct was measured through:

- Awareness and Knowledge: Caregivers were asked about their general awareness of malaria transmission, their familiarity with vaccines as preventive tools, and their specific knowledge of the existence and official introduction of the malaria vaccine in Nigeria.

- Informational Trust and Preferences: The study assessed whom caregivers trust for accurate information and identified their preferences for how and when the vaccine should be delivered, such as during routine immunisation schedules or through specialised campaigns.

Willingness, conversely, was defined as the behavioural intention and motivational state of the caregiver. It moves beyond knowledge to capture the attitude, confidence, and propensity to accept the vaccine for one’s child. A caregiver may be well-informed (ready) but remain hesitant or unwilling due to other influencing factors. This construct was assessed through:

- Perceived Value and Confidence: Caregivers rated the importance of vaccines in general and their confidence in the malaria vaccine’s ability to protect their child.

- Social and Contextual Influences: The survey explored the degree to which the opinions of family, friends, and community leaders would influence the decision to vaccinate.

- Intent and Barriers: Direct questions measured their intention to vaccinate, concerns (e.g., safety, effectiveness, cost), and structural facilitators such as affordability, access, and community engagement, including willingness to contribute a token payment.

Data Collection

Data were collected using a semi-structured questionnaire. Sections included demographic information (e.g., age, gender, education, socioeconomic status), knowledge of malaria and vaccines, perceptions toward vaccination, and factors influencing willingness or hesitancy to accept a malaria vaccine. Research assistants received comprehensive training to ensure culturally sensitive and respectful engagement with participants.

A qualitative component (an open-ended question) was embedded within the quantitative caregiver survey to provide contextual insights into vaccine acceptance. All caregivers (n = 293) were asked the same open-ended question: “What specific actions by the government or community leaders would increase your trust and willingness to vaccinate your child?”

Of these, 218 (74.4%) responded. Responses were either written directly by the caregivers or recorded verbatim by trained interviewers during face-to-face administration. The responses were analysed using qualitative content analysis with an inductive thematic approach (Braun & Clarke, 2006) [17]. Two researchers independently read the responses, generated initial codes, and grouped similar codes into candidate themes. Discrepancies in coding were discussed and resolved by consensus.

To enhance credibility and trustworthiness, the following measures were taken:

- Coder triangulation: Two independent coders analysed the data.

- Audit trail: All coding decisions and theme definitions were documented.

- Peer debriefing: The emerging themes were reviewed by a third researcher with qualitative expertise.

Analysis was conducted manually without qualitative software. Themes were defined, named, and supported with illustrative quotes from participants.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data were analysed using SPSS version 25. Descriptive statistics summarised participants’ characteristics, and multivariate logistic regression identified predictors of vaccine willingness. Qualitative responses were analysed thematically to extract suggested strategies for improving vaccine acceptance.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was granted by the Gombe State Ministry of Health Research and Ethics Committee with the number MOH/ADM/621/V1/604. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participation was voluntary, and confidentiality and anonymity were strictly maintained.

Results

Caregiver demographics, knowledge, and determinants of willingness to accept the malaria vaccine

A total of 293 caregivers of children under five years participated in the study conducted in Gombe Local Government Area (LGA), Nigeria. The demographic profile of the respondents is presented in Table 1. The majority, 126 (43.0%), were aged between 26–35 years, followed by 105 (35.8%) aged 18–25 years. Caregivers aged 46 years and above represented the smallest group. Most participants were women, 231 (78.8%), and had attained at least secondary-level education, 215 (73.4%). The majority were married, 262 (89.4%), while a few were widowed, 3 (1.0%). In terms of employment, 150 (51.2%) were unemployed, 65 (22.2%) were traders, 46 (15.7%) were civil servants, 17 (5.8%) were farmers, and 15 (5.1%) were artisans. Most respondents, 195 (66.6%) belonged to the lower socioeconomic class, and only 8 (2.7%) were in the upper-class category. Socioeconomic class was defined based on MO Ibadin et. al revised scoring system [19]. A majority, 183 (62.5%), had 1–2 children under five in their care, while 36 (12.3%) had five or more.

Knowledge of malaria and vaccines

Awareness of malaria and its consequences for children was high, with 257 respondents (87.7%) demonstrating knowledge about the disease (Table 2). A similar proportion, 259 (88.4%), correctly identified mosquito bites as the primary mode of transmission. However, 11 caregivers (3.7%) incorrectly attributed malaria to contaminated food/water or witchcraft. Regarding vaccine knowledge, 227 (77.5%) caregivers were aware that vaccines can prevent diseases. However, awareness of the malaria vaccine was relatively low: 135 (46.1%) caregivers had heard of it, and only 92 (31.4%) knew it had been introduced in Nigeria.

Perceptions and confidence in the malaria vaccine

The majority of caregivers 282 (96.2%) believed that vaccines were important or very important for preventing childhood illnesses (Table 3). Most respondents, 214 (73.0%), reported being “very confident” in the malaria vaccine’s ability to protect children, while an additional 32 (10.9%) were “somewhat confident.” However, 31 (10.6%) were neutral in the vaccine’s efficacy.

In terms of anticipated impact, 260 (88.7%) believed the malaria vaccine would reduce malaria incidence in children. Notably, 197 (67.2%) caregivers indicated that the opinions of friends, family members, or community leaders would influence their decision to vaccinate their children, while 96 (32.8%) said such opinions would not affect their decision (Table 4).

Willingness and preferences for malaria vaccination

Majority, 271 (92.5%) of caregivers expressed willingness to accept the malaria vaccine for their children (Table 4). Trust in healthcare workers was high, with 268 (91.5%) indicating confidence in their ability to provide accurate information. In terms of preferred vaccination timing, 150 (51.2%) preferred to receive the vaccine during routine immunisation visits, 112 (38.2%) were open to receiving it anytime it was available, and 31 (10.6%) preferred campaign-based delivery.

Health facilities were the most preferred place for vaccine access 244 (83.3%), followed by house-to-house delivery 37 (12.6%), while mobile vaccination units were the least preferred.

Motivators and barriers to vaccine acceptance

The most significant motivator for vaccine acceptance was assurance of safety and effectiveness 214 (73.0%) (Table 5). Other motivators included affordability 32 (10.9%), accessibility of immunisation services 12 (4.1%), and intensive community education 28 (9.6%). Health education programs were considered the most important strategy to improve vaccine uptake 195 (66.6%), followed by involvement of community and religious leaders, 75 (25.6%).

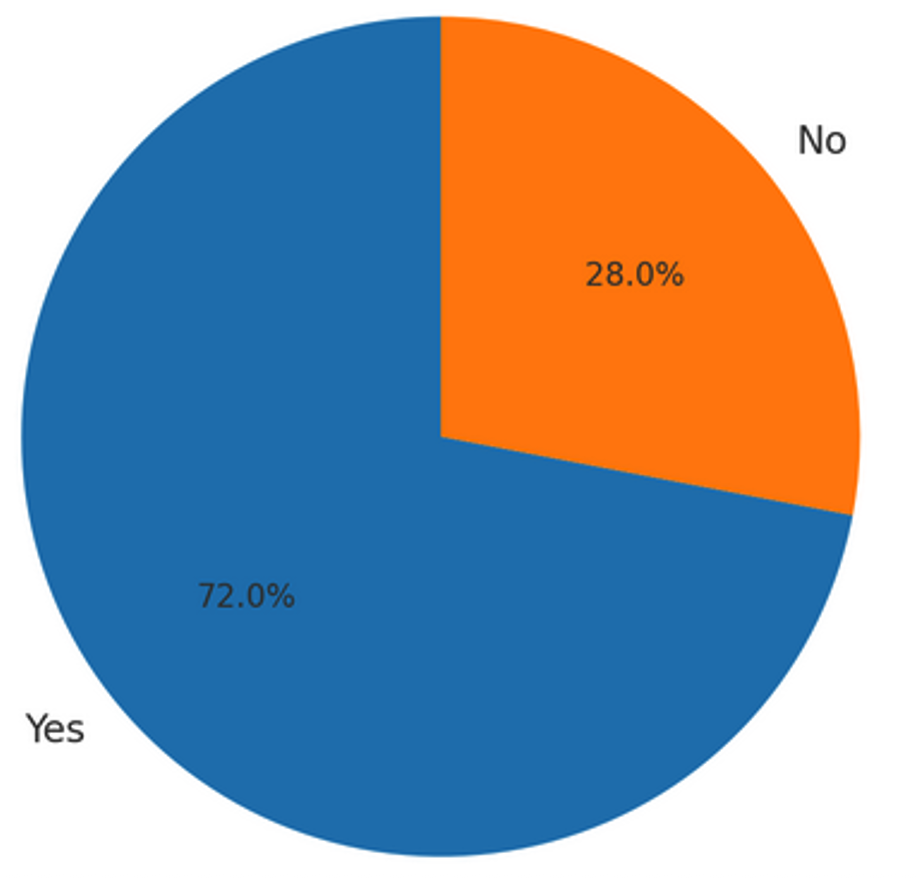

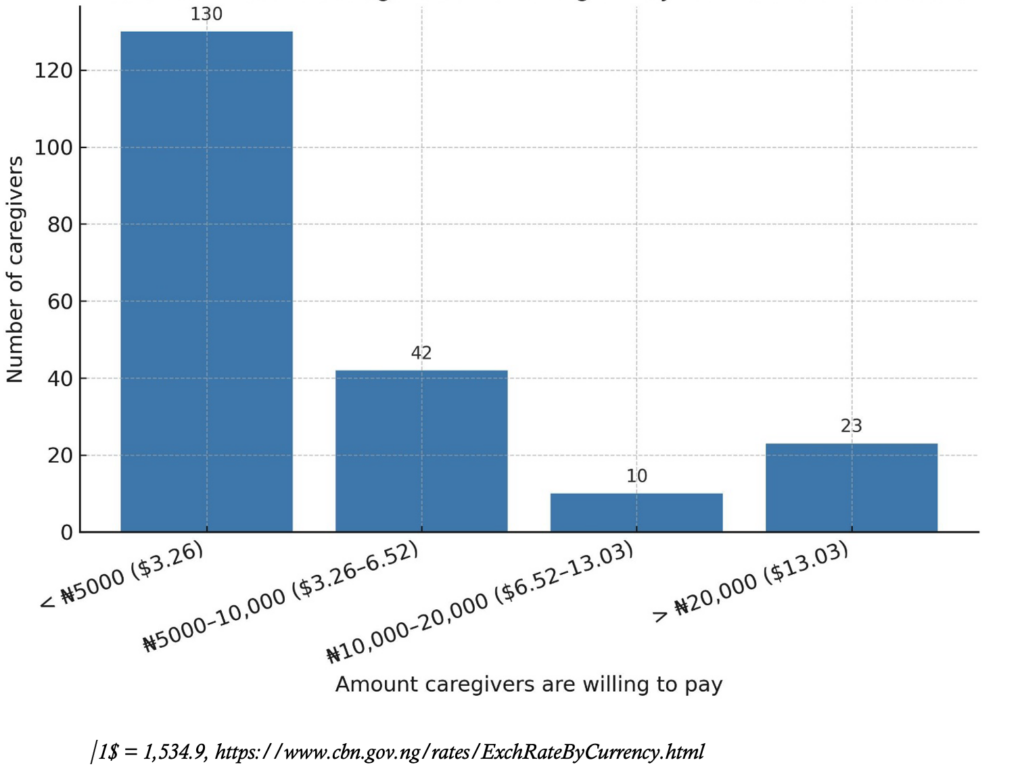

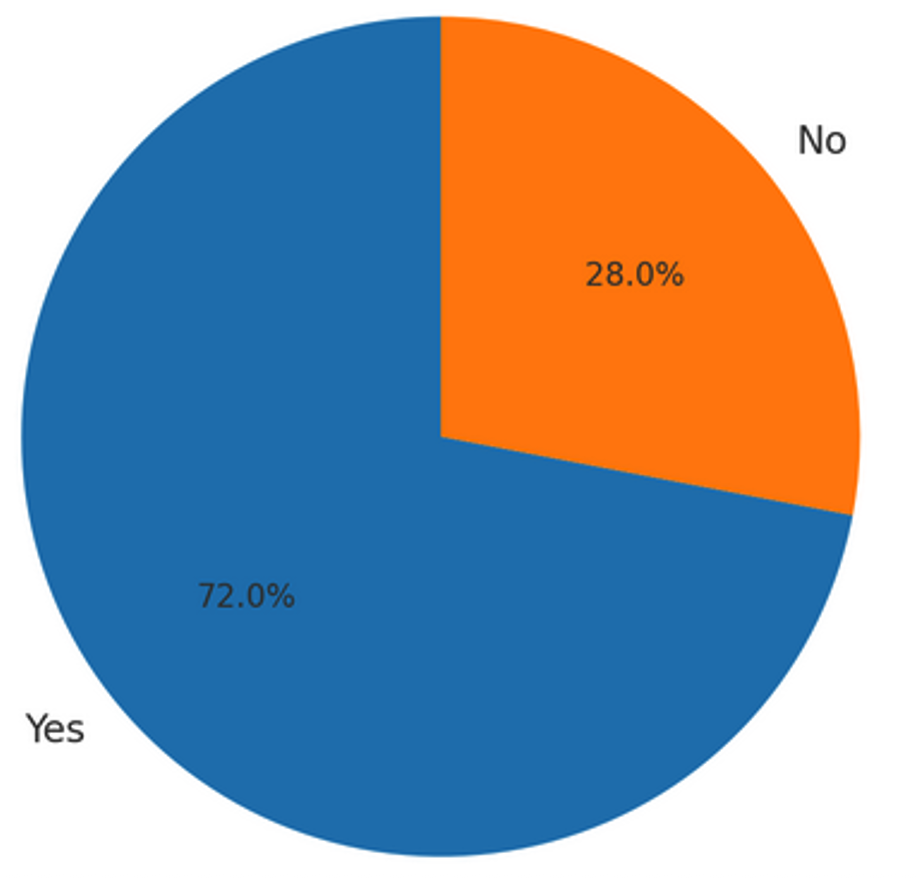

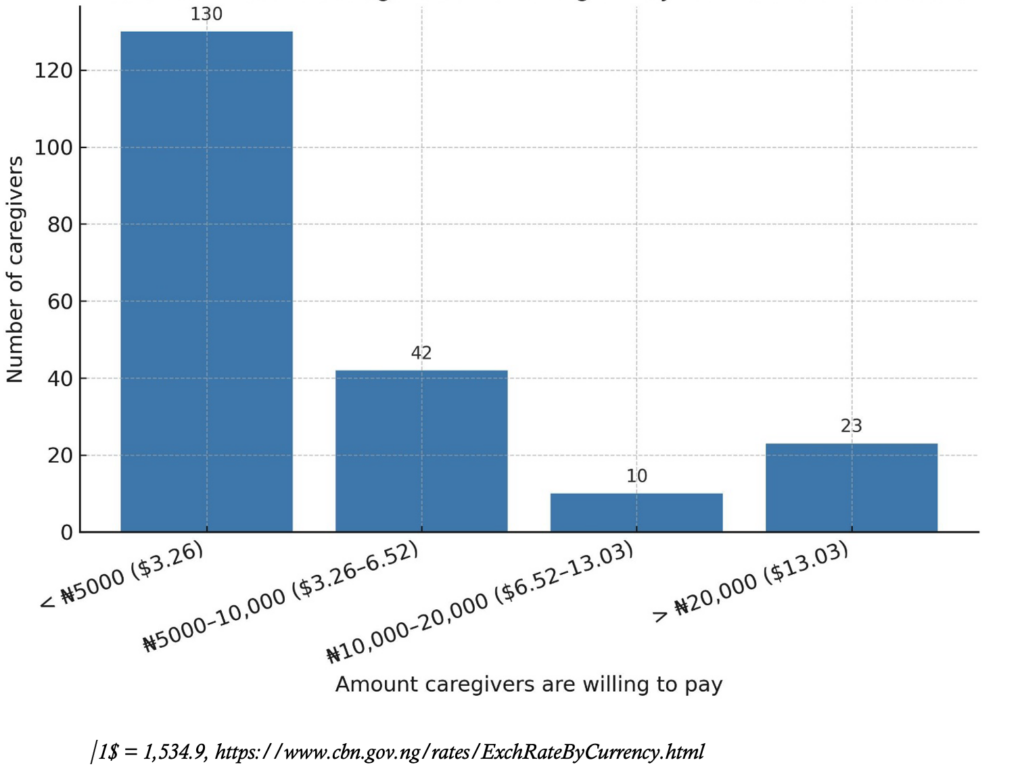

Overall, 211 caregivers (72.0%) were willing to pay a token for the malaria vaccine (Figure 1). Among them, 131 (44.7%) indicated willingness to pay less than ₦5,000 ($3.12 USD), 43 (14.7%) were willing to pay between ₦5,000 and ₦10,000 ($3.12–6.24 USD), while 24 (8.2%) reported willingness to pay above ₦20,000 ($12.48 USD) per dose (Figure 2).

Factors associated with willingness to accept the malaria vaccine

Age was strongly associated with willingness to vaccinate (χ² = 48.746, p < 0.001). Compared to respondents aged ≥46 years, those aged 18–25 years were more than 25 times more likely to accept vaccination (AOR = 25.48; 95% CI: 4.45–145.87, p < 0.001). The odds were even higher among those aged 26–35 years (AOR = 56.47; 95% CI: 8.23–387.35, p < 0.001), while respondents aged 36–45 years also showed significantly increased likelihood (AOR = 27.3; 95% CI: 3.03–246.45, p = 0.003) (Table 6).

Level of education was another significant determinant (χ² = 21.059, p < 0.001). Respondents with no formal education were significantly less likely to accept vaccination compared to those with tertiary education (AOR = 0.13; 95% CI: 0.03–0.67, p = 0.014).

The initial models that included detailed categories for marital status, occupation, and socioeconomic class were unstable due to quasi-complete separation. To address this, these variables were collapsed into binary categories (married vs. unmarried, employed vs. unemployed, and low vs. middle/high socioeconomic status). After reclassification, none showed statistically significant associations with willingness to vaccinate.

Although occupation showed a significant association in the bivariate analysis (χ² = 12.565, p = 0.014), this effect did not remain in the multivariable logistic regression. Likewise, no significant associations were observed for gender (χ² = 0.35, p = 0.852) or the number of under-five children in the household (χ² = 0.65, p = 0.724).

Caregiver suggested strategies for improving malaria vaccine acceptance

To explore how caregiver trust and willingness to accept the malaria vaccine could be enhanced, all survey participants were asked a single open-ended question: “What specific actions by the government or community leaders would increase your trust and willingness to vaccinate your child?” Of the 293 caregivers surveyed, 218 (74.4%) responded. During the questionnaire administration, some participants completed the responses themselves, while for others, the interviewer recorded the responses verbatim. All responses were subsequently analysed using an inductive thematic analysis approach. Two researchers independently reviewed the data, developed initial codes, and refined them through discussion to reach consensus on final themes, ensuring analytic rigor. Seven key themes emerged:

- Vaccine accessibility and affordability

Many participants emphasised that vaccines must be physically and financially accessible to encourage uptake. Several called for vaccines to be offered free of charge or at subsidised rates.

“Vaccines should be made accessible and affordable.”

“Affordable or free vaccines would make it easier for parents to bring their children.”

- Health system and service delivery quality

Respondents stressed the importance of qualified personnel and adequate health infrastructure. Trust in the system was associated with professional and competent vaccine delivery.

“Vaccines should be given by experienced health personnel.”

“Ensure healthcare personnel are adequate and available.”

- Trust-building through role modelling

Some participants expressed skepticism and requested that leaders demonstrate confidence in the vaccine by vaccinating their own children.

“Let people in government and health workers take their children for the vaccine first.”

- Community engagement and health education

There was a clear demand for sustained awareness campaigns and culturally appropriate community mobilisation to improve understanding and acceptance of the vaccine.

“Health awareness campaigns and community mobilisation are important.”

“We need proper education about the vaccine.”

- Government accountability and broader social responsibility

Caregivers linked vaccine acceptance to broader governance issues, including perceptions of fairness, responsiveness, and social investment by the government.

“Government should fulfil its obligations to citizens.”

“They should show concern about other issues, not just vaccines.”

- Transparency and evidence-based communication

Participants called for clear, unambiguous information about the vaccine and independent evaluation of its safety and effectiveness.

“We want clear and unambiguous information.”

“There should be transparency and independent review of the vaccine.”

- Motivation through incentives

A few caregivers mentioned that providing incentives could encourage vaccine uptake, especially in resource-limited households.

“Provide small incentives to improve uptake.”

These themes illustrate that caregivers’ willingness to vaccinate is shaped by both health system performance and sociopolitical trust. A holistic approach combining accessibility, transparency, leadership engagement, and community mobilisation is essential to increase malaria vaccine uptake among caregivers in Gombe LGA.

Discussion

This study examined caregiver readiness to adopt the malaria vaccine in Gombe LGA, Nigeria. Awareness was limited: fewer than half of respondents had heard of the malaria vaccine, and only 31.4% knew of its introduction in Nigeria. This proportion is slightly higher than that reported in Cameroon (26.7%), possibly reflecting methodological differences, as hospital-based caregivers like those in our sample are generally more health-seeking than community-based respondents [19]. Nonetheless, the low awareness highlights that willingness may not automatically translate into uptake without robust, context-sensitive communication strategies.

Perceptions of vaccines were overwhelmingly positive. Nearly all caregivers (96.2%) rated vaccines as important, and trust in healthcare workers was high (91.5%), consistent with studies identifying health professionals as critical influencers of uptake [20, 21]. However, confidence in the malaria vaccine itself was lower, with only 73% expressing strong trust, likely reflecting its novelty and limited rollout. Caregivers also highlighted the role of social networks, with 67.2% reporting that family, friends, and religious leaders influenced their decisions. This finding echoes Tanzanian evidence on COVID-19 prevention, where cultural hierarchies and leadership shaped adherence [22]. Engaging trusted community and religious leaders alongside health workers will therefore be essential for sustaining demand.

Despite these gaps in awareness and vaccine-specific confidence, willingness to vaccinate was exceptionally high: 92.5% of caregivers expressed readiness to vaccinate their under-five children. This mirrors findings from Kenya and Cameroon, where acceptability exceeded 85% [19, 23]. The consistency across endemic countries suggests that lived experience with malaria’s morbidity and mortality strongly shapes acceptance. In Kenya, willingness was highest in malaria-endemic Nyanza (98.9%) and lowest in the low-transmission North Eastern Province (23%) [23], underscoring the influence of local transmission dynamics on demand.

Sociodemographic factors also influenced willingness. Younger caregivers (18–35 years) and those with formal education were significantly more likely to accept vaccination, consistent with findings from Kenya and Cameroon, where education and generational differences predicted acceptance[ 23, 24]. In contrast, older caregivers and those without formal education were less willing, reflecting gaps in health literacy and openness to new interventions. Unlike Azakoh et al., who reported lower willingness among male caregivers, our study found no gender effect[19]. This may be due to contextual or cultural differences, or the hospital-based nature of our sample, where both male and female caregivers may be more health-engaged. These findings highlight the need to prioritise engagement of older and less educated caregivers while maintaining broad community support.

The primary motivators for uptake were assurances of safety and effectiveness, followed by affordability and accessibility. Similar safety concerns have been documented in Shanghai and Uganda, where doubts about vaccine safety impeded uptake despite high willingness [25, 26]. Encouragingly, over 72% of caregivers in our study expressed willingness to pay for the vaccine, although financial constraints remain a challenge for lower-income households.

Qualitative insights reinforced these findings and revealed broader expectations of health governance. Caregivers recommended subsidised or free vaccines, visible role-modelling by leaders, transparent communication of safety and efficacy, culturally sensitive education, and improved health system quality. A minority suggested incentives to encourage uptake. These themes underscore that vaccine acceptance is not determined by willingness alone but is embedded in wider trust in government, health systems, and sociocultural structures.

Although most caregivers correctly identified mosquitoes as the cause of malaria, misconceptions persisted, with some attributing it to witchcraft or contaminated food. Such views, although minority, mirror findings from Kano, Kenya, and other African contexts where non-biomedical beliefs (e.g., exposure to cold, spiritual causes) continue to shape health behaviour[27, 28]. Left unaddressed, these misconceptions may undermine vaccine acceptance by reinforcing hesitancy within communities.

Finally, integration into existing immunisation schedules was strongly preferred, highlighting the operational feasibility of delivering the malaria vaccine through Nigeria’s Expanded Programme on Immunisation. This platform offers a cost-effective and sustainable entry point for nationwide rollout.

Implications

The findings point to a critical window for policymakers: high willingness creates an opportunity, but sustained demand will depend on increasing awareness, addressing safety concerns, and building confidence through trusted healthcare workers and community leaders. Tailored strategies should focus particularly on older and less educated caregivers, while ensuring affordability to prevent inequities in access.

Limitations

The study’s cross-sectional design limits causal inference, and recruitment from hospital-based caregivers may bias results toward more health-seeking populations, reducing generalisability. Additionally, while the qualitative component provided valuable caregiver-driven strategies, it did not fully explore prior experiences with vaccination, sources of misinformation, or deeper cultural influences, which could have offered further insight into barriers to uptake.

Conclusion

This study shows strong caregiver readiness to accept the malaria vaccine for under-five children in Gombe LGA, driven by confidence in vaccine effectiveness, trust in healthcare workers, and preference for routine immunisation. However, low awareness remains a significant gap, consistent with findings from other settings, and may undermine sustained uptake if not addressed. Since willingness was self-reported, actual uptake may differ, underscoring the need for health education, community engagement, and subsidised access. Monitoring real-world uptake will be critical to ensure that expressed willingness translates into meaningful vaccine coverage and improved child health outcomes.

What is already known about the topic

- Malaria remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in Nigeria, particularly among children under five.

- Vaccines such as RTS, S/AS01 and R21/Matrix-M have been developed and shown to reduce malaria burden.

- Successful vaccine implementation depends on caregiver acceptance and community readiness.

- Nigeria has initiated pilot malaria vaccine rollouts in selected high-burden states (e.g., Kebbi and Bayelsa).

What this study adds

- This provides the first data on caregiver readiness and willingness to accept the malaria vaccine in Gombe, a non-pilot state.

- It also reveals high willingness (92.5%) to vaccinate children despite low awareness (46.1%) of the malaria vaccine.

- It identifies key sociodemographic factors (age and education) influencing vaccine acceptance.

- It highlights health facilities and healthcare workers as preferred and trusted vaccine delivery channels.

- Offers practical, context-specific recommendations for future malaria vaccine rollout strategies in northeastern Nigeria.

Authors´ contributions

IA conceived the study, developed the research concept and framework, designed the questionnaire, performed data analysis and interpretation, and contributed to both the initial and final drafts of the manuscript.

IA, IIM, and IBA participated in data collection.

IA, IBA, IIM, ABA, MC, FIU, MWM, BRH, RSD, and AA critically reviewed the protocol and revised the final draft of the manuscript.

IA was responsible for the final refinement of the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

| Variable | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18-25 | 105 | 35.8 |

| 26-35 | 126 | 43.0 |

| 36-45 | 43 | 14.7 |

| 46 and above | 19 | 6.5 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 62 | 21.2 |

| Female | 231 | 78.8 |

| Education level | ||

| No formal education | 47 | 16.0 |

| Primary education | 31 | 10.6 |

| Secondary education | 111 | 37.9 |

| Tertiary education | 104 | 35.5 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 23 | 7.8 |

| Married | 262 | 89.4 |

| Divorced | 5 | 1.7 |

| Widowed | 3 | 1.0 |

| Occupation | ||

| Unemployed | 150 | 51.2 |

| Farmer | 17 | 5.8 |

| Trader | 65 | 22.2 |

| Civil servant | 46 | 15.7 |

| Artisan | 15 | 5.1 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||

| Lower class | 195 | 66.6 |

| Middle class | 90 | 30.7 |

| Upper class | 8 | 2.7 |

| Number of children under five per caregiver | ||

| 1-2 | 183 | 62.5 |

| 3-4 | 74 | 25.2 |

| > 5 | 36 | 12.3 |

| Question | Response | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Are you aware of malaria and its effects on children under five? | Yes | 257 | 87.7 |

| No | 36 | 12.3 | |

| How is malaria transmitted? | Mosquito bites | 259 | 88.4 |

| Contaminated food/water | 8 | 2.7 | |

| Witchcraft | 3 | 1.0 | |

| Don’t know | 23 | 7.8 | |

| Are you aware of any vaccine that is used to prevent diseases? | Yes | 227 | 77.5 |

| No | 66 | 22.5 | |

| Have you heard about the Malaria vaccine? | Yes | 135 | 46.1 |

| No | 158 | 53.9 | |

| Are you aware that malaria vaccine has been introduced in some States in Nigeria? | Yes | 92 | 31.4 |

| No | 201 | 68.6 |

| Questions | Responses | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| How important do you think vaccines are for preventing diseases in children? | Very important | 204 | 69.6 |

| Important | 78 | 26.6 | |

| Not important | 11 | 3.8 | |

| How confident are you in the malaria vaccine’s ability to protect your child? | Very confident | 214 | 73.0 |

| Somewhat confident | 32 | 10.9 | |

| Neutral | 31 | 10.6 | |

| Not confident | 16 | 5.5 | |

| Do you believe the malaria vaccine will help reduce malaria in children? | Strongly agree | 143 | 48.8 |

| Agree | 117 | 39.9 | |

| Neutral | 23 | 7.9 | |

| Disagree | 2 | 0.7 | |

| Strongly disagree | 8 | 2.7 |

| Questions | Responses | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Would the opinions of friends, family, or community leaders influence your decisions to vaccinate your child? | Yes | 197 | 67.2 |

| No | 96 | 32.8 | |

| Would you be willing to vaccinate your child against malaria? | Yes | 271 | 92.5 |

| No | 22 | 7.5 | |

| Do you trust healthcare workers to provide accurate information about vaccines? | Yes | 268 | 91.5 |

| No | 25 | 8.5 |

| Questions | Responses | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| When would you prefer your child to receive the malaria vaccine? | During routine immunisation | 150 | 51.2 |

| At a specialised vaccination campaign | 31 | 10.6 | |

| Anytime it is available | 112 | 38.2 | |

| What mode of delivery of the vaccine will you prefer? | Health facilities | 244 | 83.3 |

| Mobile vaccination units | 12 | 4.1 | |

| Door-to-door campaigns | 37 | 12.6 | |

| What factors would encourage you to vaccinate your child? | Assurance of safety and effectiveness | 214 | 73.0 |

| Free or affordable vaccines | 32 | 10.9 | |

| Access to vaccination services | 12 | 4.1 | |

| Community campaigns and education | 28 | 9.6 | |

| Incentives | 7 | 2.4 | |

| How can the community be better engaged to improve vaccine acceptance? | Health education programs | 195 | 66.6 |

| Involvement of community and religious leaders | 75 | 25.6 | |

| Mobile vaccination units | 17 | 5.8 | |

| Other | 6 | 2.0 |

| Variable | Yes N=271 n (%) | No N=22 n (%) | χ², p-value | Crude OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 18–25 | 97 (35.8) | 8 (36.4) | 48.746, <0.001 | 10.9 (3.44–34.59) | <0.001 | 25.5 (4.45–145.9) | <0.001 |

| 26–35 | 123 (45.4) | 3 (13.6) | 36.9 (8.60–158.4) | <0.001 | 56.5 (8.23–387.4) | <0.001 | |

| 36–45 | 41 (15.1) | 2 (9.7) | 18.5 (3.44–99.1) | 0.001 | 27.3 (3.03–246.5) | 0.003 | |

| 46+ | 11 (3.7) | 9 (40.9) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 57 (21.0) | 5 (22.7) | 0.35, 0.852 | 0.91 (0.32–2.56) | 0.852 | 1.91 (0.33–11.1) | 0.470 |

| Female | 214 (79.0) | 17 (77.3) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Level of Education | |||||||

| None | 36 (13.3) | 11 (50.0) | 21.059, <0.001 | 0.10 (0.03–0.37) | 0.001 | 0.13 (0.03–0.67) | 0.014 |

| Primary | 29 (10.7) | 2 (9.1) | 0.43 (0.07–2.70) | 0.369 | 0.36 (0.04–3.19) | 0.355 | |

| Secondary | 105 (38.7) | 6 (27.3) | 0.52 (0.13–2.14) | 0.364 | 0.28 (0.05–1.44) | 0.127 | |

| Tertiary (Ref) | 101 (37.3) | 3 (13.6) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Marital Status | |||||||

| Single | 22 (8.1) | 1 (4.5) | 1.704, 0.790 | ||||

| Married | 242 (89.3) | 20 (90.9) | |||||

| Widowed | 4 (1.5) | 1 (4.5) | |||||

| Divorced | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | |||||

| Married vs Unmarried | Married: 242 (89.3) | 20 (90.9) | 0.56, 0.813 | 0.83 (0.19–3.75) | 0.814 | 1.95 (0.33–11.5) | 0.462 |

| Occupation | |||||||

| Unemployed | 135 (49.8) | 15 (68.2) | 12.565, 0.014 | ||||

| Farmer | 13 (4.8) | 4 (18.2) | |||||

| Trader | 63 (23.2) | 2 (9.1) | |||||

| Civil servant | 45 (16.6) | 1 (4.5) | |||||

| Artisan | 15 (5.5) | 0 (0.0) | |||||

| Employment status | |||||||

| Unemployed | 135 (49.8) | 15 (68.2) | 2.747, 0.097 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Employed | 136 (50.2) | 7 (31.8) | 2.16 (0.85–5.46) | 0.104 | 2.22 (0.64–7.73) | 0.208 | |

| Socioeconomic status | |||||||

| Lower class | 179 (66.1) | 16 (72.7) | 0.878, 0.645 | ||||

| Middle class | 84 (31.0) | 6 (27.3) | |||||

| Upper class | 8 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||||

| Low vs Middle/High | 179 (66.1) | 16 (72.7) | 0.407, 0.523 | 1.73 (0.52–3.62) | 0.525 | 0.64 (0.17–2.38) | 0.508 |

| Number of under-five children in household | |||||||

| 1–2 | 170 (62.7) | 13 (59.1) | 0.646, 0.724 | 0.77 (0.17–3.57) | 0.737 | 0.25 (0.03–1.82) | 0.170 |

| 3–4 | 67 (24.7) | 7 (31.8) | 0.56 (0.11–2.86) | 0.488 | 0.36 (0.05–2.86) | 0.336 | |

| >5 | 34 (12.5) | 2 (9.1) | Ref | Ref | |||

References

- World Health Organization (African Region). Report on malaria in Nigeria 2022 [Internet]. Brazzaville (Congo): World Health Organization (African Region); 2023 [cited 2025 Sep 23]. 87 p. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/countries/nigeria/publication/report-malaria-nigeria-2022

- World Health Organization. World malaria report 2024 [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2024 Dec 11 [cited 2025 Sep 23]. 316 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240104440

- World Health Organization. Malaria [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2024 Dec 11 [cited 2025 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malaria

- United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (Nigeria). Nigeria receives malaria vaccines ahead of roll out [Internet]. Abuja (Nigeria): United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (Nigeria); 2024 Oct 17 [cited 2025 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/press-releases/nigeria-receives-malaria-vaccines-ahead-roll-out

- Maamor NH, Muhamad NA, Mohd Dali NS, Leman FN, Rosli IA, Tengku Bahrudin Shah TPN, et al. Prevalence of caregiver hesitancy for vaccinations in children and its associated factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2024 Oct 24 [cited 2025 Sep 23];19(10):e0302379. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302379 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0302379

- World Health Organization. WHO recommends groundbreaking malaria vaccine for children at risk – historic RTS,S/AS01 recommendation can reinvigorate the fight against malaria [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2024 Dec 11 [cited 2025 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/06-10-2021-who-recommends-groundbreaking-malaria-vaccine-for-children-at-risk

- World Health Organization. WHO prequalifies a second malaria vaccine, a significant milestone in prevention of the disease [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2024 Dec 21 [cited 2025 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/21-12-2023-who-prequalifies-a-second-malaria-vaccine-a-significant-milestone-in-prevention-of-the-disease

- Center for Diseases Control and Prevention. Malaria vaccines [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): Center for Diseases Control and Prevention; 2024 Apr 2 [cited 2025 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/php/public-health-strategy/malaria-vaccines.html

- Ministry of Health (Nigeria). 2021 Malaria indicator survey [Internet]. Abuja (Nigeria): Ministry of Health (Nigeria); 2021 [cited 2025 Sep 23]. 2 p. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/MF34/MF34_NorthEast.pdf

- Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approach. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2009 [cited 2025 Sep 23]. 260 p.

- Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2017 [cited 2025 Sep 23]. 457 p.

- Gombe State (Nigeria). List of health facilities [Internet]. Gombe State (Nigeria): Gombe State Government; [cited 2025 Jan 1]. 16 p. Available from: http://library.procurementmonitor.org/backend/files/List%20of%20Health%20Facilities%20in%20Gombe%20State.pdf

- Thomas Brinkhoff. Gombe State in Nigeria [Internet]. Gombe State (Nigeria): City population; 2022 [cited 2025 Sep 23]. Available from: https://citypopulation.de/en/nigeria/admin/NGA016__gombe/

- Bolarinwa O. Sample size estimation for health and social science researchers: the principles and considerations for different study designs. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2020 Apr [cited 2025 Sep 23];27(2):67. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/10.4103/npmj.npmj_19_20 doi: 10.4103/npmj.npmj_19_20

- The Demographic and Health Surveys. Nigeria: MIS, 2021 [Internet]. Rockville (MD): The Demographic and Health Surveys; 2022 [cited 2025 Sep 23]. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/methodology/survey/survey-display-576.cfm

- Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Schulz WS, Chaudhuri M, Zhou Y, Dube E, et al. Measuring vaccine hesitancy: the development of a survey tool. Vaccine. 2015 Aug 14 [cited 2025 Sep 23];33(34):4165-75. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0264410X15005010 doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.037

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006 Jan [cited 2025 Sep 23];3(2):77-101. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Ibadin MO, Akpede GO. A revised scoring scheme for the classification of socio-economic status in Nigeria. Niger J Paediatr. 2021 Feb 4 [cited 2025 Sep 23];48(1):26-33. Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/njp/article/view/203582 doi: 10.4314/njp.v48i1.5

- Azakoh JN, Tamgno ED, Ifang S, Talom B, Baty L, Tsague J, et al. Assessment of the acceptance of the RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine by parents of children under five years of age in the Foumbot and Foumban health districts in Cameroon. JMMS. 2025 Dec 25 [cited 2025 Sep 23];1(1):13-20. Available from: https://urfjournals.org/open-access/assessment-of-the-acceptance-of-the-rts-sas01-malaria-vaccine-by-parents-of-children-under-five-years-of-age-in-the-foumbot-and-foumban-health-districts-in-cameroon.pdf doi: 10.51219/JMMS/Tsapi-AT/03

- Bugase E, Tindana P. Influence of trust on the acceptance of the RTS,S malaria vaccine in the Kassena-Nankana districts of Ghana. Malar J. 2024 Nov 29 [cited 2025 Sep 23];23(1):365. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-024-05180-x doi: 10.1186/s12936-024-05180-x

- Li C, Su Z, Chen Z, Cao J, Xu F. Trust of healthcare workers in vaccines may enhance the public’s willingness to vaccinate. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022 Dec 30 [cited 2025 Sep 23];18(7):2158669. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21645515.2022.2158669 doi: 10.1080/21645515.2022.2158669

- Onuekwe CE, Kessy AT, Kamanyi E, Kazyoba PE, Makulilo A, Ndaluka T, et al. Understanding the socio-ecological determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake: a cross-sectional study of post-COVID-19 Tanzania. J Public Health Afr. 2025 Apr 18 [cited 2025 Sep 23];16(3):3. Available from: https://publichealthinafrica.org/index.php/jphia/article/view/1145 doi: 10.4102/jphia.v16i3.1145

- Ojakaa DI, Jarvis JD, Matilu MI, Thiam S. Acceptance of a malaria vaccine by caregivers of sick children in Kenya. Malar J. 2014 May 5 [cited 2025 Sep 23];13(1):172. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1475-2875-13-172 doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-172

- Rainey JJ, Watkins M, Ryman TK, Sandhu P, Bo A, Banerjee K. Reasons related to non-vaccination and under-vaccination of children in low and middle income countries: findings from a systematic review of the published literature, 1999-2009. Vaccine. 2011 Oct 16 [cited 2025 Sep 23];29(46):8215-21. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0264410X11013661 doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.096

- Amodan BO, Okumu PT, Kamulegeya J, Ndyabakira A, Amanya G, Emong DJ, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and barriers to uptake of COVID-19 vaccine in Uganda, February 2021. BMJ Glob Health. 2025 Mar 26 [cited 2025 Sep 23];10(3):e016959. Available from: https://gh.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjgh-2024-016959 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2024-016959

- Wagner AL, Huang Z, Ren J, Laffoon M, Ji M, Pinckney LC, et al. Vaccine hesitancy and concerns about vaccine safety and effectiveness in Shanghai, China. Am J Prev Med. 2021 Jan [cited 2025 Sep 23];60(1):S77-86. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0749379720304025 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.09.003

- Muhammad A, Jumbam AS, Bukar M, Jajere BM, Tukur Z, Hamma AB. Knowledge, attitude and practices towards malaria amongst Almajirai in selected Tsangayu of Gwale and Municipal local government areas of Kano State. Biol Environ Sci J Trop. 2023 [cited 2025 Sep 23];20(1):11-20. Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/bestj/article/view/248517

- Ngutu M, Omia DO, Ngage TO, Oduor CA, Ouko NO, Oingo B, et al. Gender-related factors affecting community malaria-related perceptions and practices in Migori County, Kenya. Malar J. 2025 Jun 19 [cited 2025 Sep 23];24(1):196. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-025-05336-3 doi: 10.1186/s12936-025-05336-3