Research![]() | Volume 8, Article 29, 2 May 2025

| Volume 8, Article 29, 2 May 2025

Community risk perception of Mpox in Osun State, Southwest Nigeria

Mariam Treasure Olaoye1, Mathias Besong2, Joseph Tanimowo3, Abosede Olatokun3, Ayodele Majekodunmi3

&Corresponding author: Mathias Besong, C/o Nigeria Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program, 50, Haile Selassie Street, Asokoro, Abuja. Email: drbisong@yahoo.com

Received: 20 Aug 2023, Accepted: 30 Apr 2025, Published: 2 May 2025

Domain: Mpox; Infectious Diseases Epidemiology

Keywords: Monkeypox, risk perception, Osun State, Nigeria

©Mariam Treasure Olaoye et al Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Mariam Treasure Olaoye et al Community risk perception of Mpox in Osun State, Southwest Nigeria. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8:29. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph.2025.8.2.169

Abstract

Background: Mpox, formerly known as Monkeypox, is a viral zoonotic disease that re-emerged in Nigeria in September 2017. Since then, all states around Osun have reported at least one case. However, Osun State reported her first incidence on August 15, 2022. We conducted a community risk assessment in response to the outbreak to assess the risk of disease and determine communication needs.

Methods: Data was collected using a standardized interviewer-administered electronic questionnaire adapted from the questionnaire on risk perception of infectious disease outbreaks designed by the Effective Communication in Outbreak Management for Europe (ECOM). The data analysis was done using MS Excel and EpiInfo7. We summarized data using means, standard deviation, proportion, and percentages.

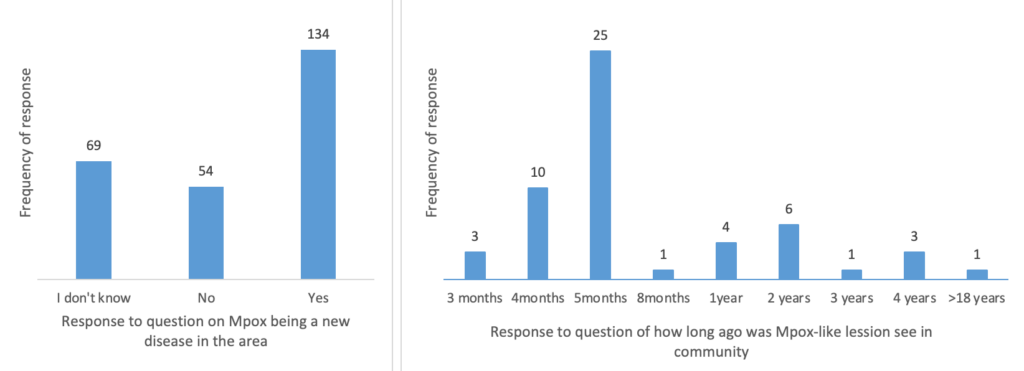

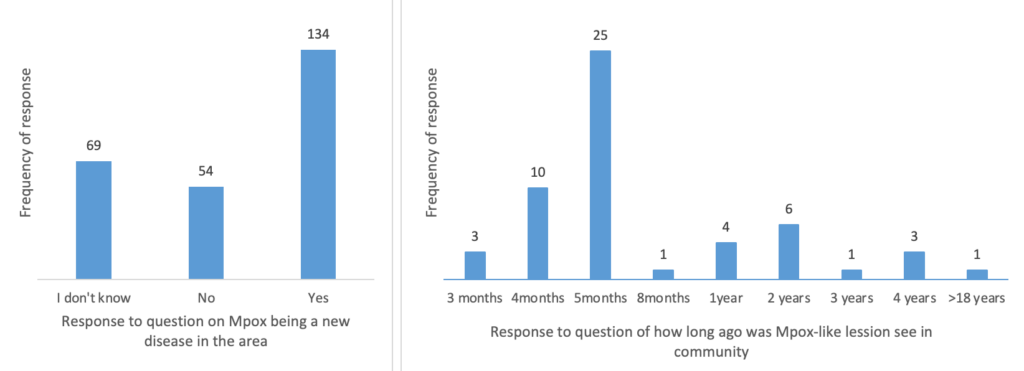

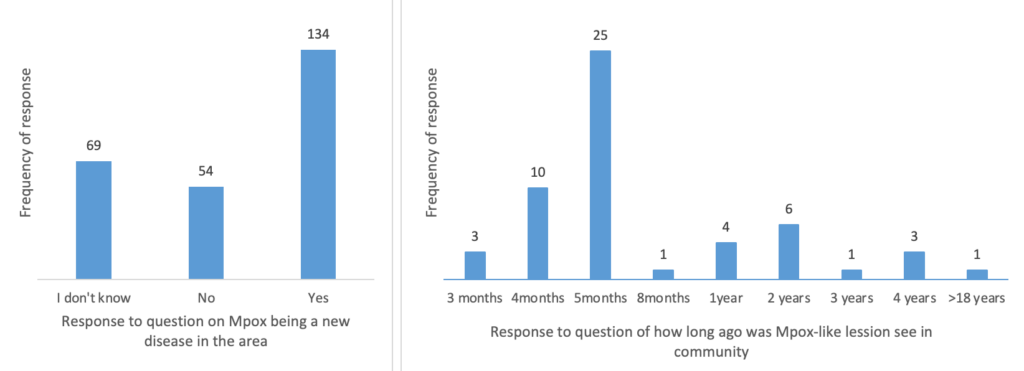

Results: 257 participants from Osogbo metropolis took part in the study. The mean age of the respondents was 39.5 ± 12.8 years. Majority (52.9%, 136/257) were male, and 56.0% (144/257) lived in semi-urban areas. Most, 165 (64.2%) of the respondents were married, with about half, 128 (49.8%) having at least tertiary education and 64 (24.9%) working as civil servants in the state. Knowledge of Mpox among respondents was good, 186 (72.4%). The majority of the residents, 187 (72.8.0%), were worried they could contract the disease if they did not take appropriate preventive measures. Hence, 191 (74.3%) were willing to comply with public health advisories. Several respondents, 179 (69.7%) wanted more information on how to prevent and control Mpox, with nearly 198 (80%) preferring information from the State Ministry of Health. Most importantly, 54 (21.3%)respondents claimed Mpox was not a new disease in the area.

Conclusion: Knowledge and perception of Mpox were relatively good among survey participants. Nevertheless, locals say the disease has been in the area long before the “index” case was discovered in August 2022. We recommend intensification of surveillance activities in all districts in the State.

Introduction

Mpox is a rare viral disease that can be transmitted from animals to humans. The disease is caused by Mpox virus, which is genetically very similar to the virus that causes Smallpox, but less severe and has milder symptoms [1–3]. Mpox is a re-emerging infectious disease of global public health importance [1]. The disease is endemic in Nigeria and a few other countries in West and Central Africa [3–7]. The re-emergence of Mpox in recent years can be associated with environmental changes, urbanization, globalization and decreased smallpox immunity, although these factors alone cannot explain the several outbreaks recorded in recent times [8–10]. The 2022 outbreak, for example, had seen unprecedented levels of transmission worldwide, with more than 79,411 laboratory-confirmed cases and 50 deaths reported from 110 countries in all six WHO regions from January 1 to 30 November 13, 2022 [11].

Mpox is mainly transmitted from animals to humans through direct contact with blood, body fluids, or cutaneous or mucosal lesions of infected animals [12,13].. The possibility of human-to-human transmission has also been reported through direct contact with skin lesions of infected individuals, through respiratory droplets following prolonged face-to-face contact, and through recently contaminated objects including clothing and bedding [14–16]. Vertical transmission has also been documented through the placenta and during childbirth [17–19]. Intercourse with an infected partner can also result in sexual transmission [20–22]. Mpox transmission has also been linked to the consumption of bush meat, especially in sub-Sahara Africa where it is considered a staple source of protein in rural communities [23, 24]. The symptoms of Mpox infection typically occur in two phases. The first phase is characterized by fever, headache, muscle pains, general body weakness, and lymphadenopathy [6,25].

Lymphadenopathy is a common symptom of Mpox, with lymph nodes swelling in areas such as the neck (submandibular and cervical), armpits (axillary), or groin (inguinal). This swelling can affect both sides of the body or just one side. During this period, a person may be able to transmit the disease to others [26]. The second phase is the rash phase that usually starts about 1 – 3 days following the onset of fever. The Mpox rash typically appears on the face and extremities, including the palms and soles, and spreads in a centrifugal pattern evolving from macules to papules, vesicles, pustules, and finally scabs [21,27,28]. A person remains contagious until all scabs have fallen off and new, intact skin has formed underneath [26]. Monkeypox infections turn to resolve on their own within 2 to 4 weeks in healthy individuals. However, the most severe cases of the disease tend to occur more among children and immunocompromised individuals [6,25].

Nigeria is one of the countries with the highest reported cases of Mpox in Africa [29]. Since the re-emergence of Mpox in Nigeria between 1st of September 2017 and 7th August 2022, a total of 2061 suspected cases have been reported, with 830 (40.3%) confirmed and 15 deaths (CFR=1.8%). Approximately 66.2% of the cases are males. Thirty-two of the 36 States and the Federal Capital Teritory (FCT) have reported at least one case, with six States (Lagos (184), Rivers (83), Bayelsa (76), Delta (55), Abia (49) and Imo (41) states in particular accounting for 58.7% of the Mpox cases. Majority of the high burden states are located within the forest belt of the country [30]. This is consistent with what is known about Mpox transmission in West and Central Africa [31,32]. However, the majority of cases have been documented in metropolitan settings and cities where there is little chance of coming into contact with the animals listed as possible reservoirs of Mpox [28,33]. This pattern may be attributed mainly to human-to-human transmission cycles of Mpox transmission [12,17,34], which in the case of Nigeria is made even more complicated now with recent evidence pointing to the existence of asymptomatic carriers of the Mpox virus in some communities[35] The first confirmed case of Mpox reported in Osun State was on the 15th of August 2022. This was despite the fact that all the contiguous states around Osun had reported at least one case of the disease prior to this period. The Osun State outbreak has only increased doubts about the effectiveness of Nigeria’s Mpox surveillance system. As a result, we set out to assess the knowledge, risk perception, and information needs of the people of Osogbo, as well as to ascertain whether Mpox was indeed a new disease in the affected communities.

Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional study was conducted in Osogbo, the capital city of Osun State, between September 30 and December 5, 2022. This study was aimed at assessing the knowledge, risk perception, and information needs of the community members regarding Mpox following a recent outbreak in some parts of the city. The Lot Quality Assurance Sampling (LQAS) method used by the World Health Organization (WHO) and other public health organizations for rapid assessment of health indicators such as immunization coverage, disease prevalence at the community or household level, was used for this study [27]. The most important application of LQAS is to determine whether the subject’s lots are acceptable or not [36]. While LQAS is generally quick to execute, it also increases the amount of time needed to train enumerators and the amount of time spent collecting data in the field, as well as time needed for data analysis [37].

Study site

Osogbo city is the capital of Osun State and headquarters of both Osogbo and Olorunda Local Government Areas, two of the LGAs with confirmed cases of Mpox. The city is the major commercial nerve center of the state and is easily accessible from any part of the state because of its central location. It has a total landmass of 47 km2 and is situated at within latitude 7o46’ N and longitudes 4o34’E [38]. The projected population of the city from the 2006 census is about 395,500 as at 2016. It has a tropical hinterland climate with a mean annual rainfall of 1200 to 1400 millimeters and a mean annual temperature of around 27°C [39]. The lowland tropical rainforest vegetation in Osogbo consists of many canopies and lianas, many of which have since yielded to secondary forests and derived savannahs as a result of intensive cultivation and bush burning [39,40].

Study participants

Residents of Osogbo who are at least 18 years old and have lived in their current location in the city for at least 21 days prior to the time of the survey.

Data collection tool and procedure

A standardized electronic questionnaire was developed based on the guidelines for risk perception during infectious disease outbreaks, as outlined by the Effective Communication in Outbreak Management for Europe (ECOM) [41]. The questionnaire template was adapted to reflect Mpox and specific questions relating to the epidemiology of Mpox were included. Qualified interviewers, trained in research ethics, interviewing skills and the content of the questionnaire, conducted face-to-face interviews with the selected households. Data collection adhered to safety protocols recommended by the Nigeria Center for Disease Control (NCDC) for preventing the spread of COVID-19. These protocols included the use of face masks, maintaining a minimum distance of 2 meters from respondents, and using alcohol-based hand sanitizers.

Data analysis

The collected data were downloaded in MS Excel format, cleaned and validated using Microsoft Excel 2019 software.Data analysis was performed using EpiInfo7 software. Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, frequencies, proportions, and percentages, were used to summarize the data.

Scoring for Knowledge Assessment: Knowledge assessment questions were designed to evaluate participants’ understanding of Mpox. Each correct answer a score of 2 points. The total knowledge score ranged from 0 to 10 points. Participants who scored 1-4 points were categorized as having poor knowledge, while those with scores of 5-10 points were considered to have good knowledge.

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Osun State Health Research Ethical Committee (OSHREC) of the Department of Health Planning, Research, and Statistics, Osun State Ministry of Health, with reference number OSHREC/PRS/569T/291. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants, ensuring their anonymity andconfidentiality throughout the study.

Results

A total of 257 residents from five randomly selected settlements of Osogbo took part in the study. One hundred and thirty-six (52.9%) of the participants were males. Majority, 147 (57.2%) were between the ages of 20-39 years. The mean age of the respondents was 39.5 ± 12.8 years with a range of 18 to 76 years. One hundred and forty-four (56.0%) of the respondents live in the semi-urban areas, 165 (64.2%) of them were married with 128 (49.8%) having at least tertiary education. The distributionof the respondents by their occupation showed the top 3 occupations as; civil servants 64 (24.9%), petty traders 55 (21.4%) and artisans 38 (14.8%) (Table 1).

Knowledge of Monkeypox

Of the 257 respondents, 195 (75.9%) knew that Mpox is a zoonotic disease. Majority 119 (46.3%) believed that Mpox couldbe prevented through good hand hygiene practices. However, a lot of them, 168 (65.4%) incorrectly assumed that Mpox cases always present with a typical rash, and 233(86.3%) did not know if there is a WHO recommended vaccine for Mpox.Generally, knowledge of Mpox was quite good with 186 (72.4%) or respondents scoring 5 points or higher out of the possible10 points allocated for the knowledge questions (Table 2).

Perception on Monkeypox

One hundred and thirty-one (51.0%) of the respondents were sure Mpox is a severe disease and 187 (72.8%) saying they wereworried they could contract the disease if adequate precaution were not taken. A total of 108 (43.7%) participants were really concerned about what will happen if they contract Mpox. One hundred and ninety-one(74.3%) of them were willing to adhere to any advice given by health authorities to prevent the disease including avoidingcontact with wildlife and not eating “bush meat”. However, only (33.5%) of the participants surveyed believed that those whohad previously taken the smallpox vaccine are protected from Mpox infection (Table 3).

About Mpox being an emerging disease

Fifty-four (21.3%) of the respondents agreed that Mpox was not a new disease in the area. They affirmed that they had seenthe rash depicted on the Nigeria Center for Disease Control (NCDC) flyers before on residents. When questioned on howlong ago the rashes were seen, responses ranged from 3 months ago to as far back as 18 years (Figure 1).

Information needs of respondents on the Mpox outbreak in Osun State

The topics on Mpox which respondents considered to be most relevant were prevention of Mpox 179 (69.7%), treatment165 (64.2%), mode of transmission 134 (52.1%) and signs/symptoms 116 (45.1%). Majority 198 (77.0%) of the respondents wanted information on Mpox to come from the State Ministry of Health or the Nigeria Center for Disease Control (NCDC) 132 (51.4%). The most preferred information channels were Radio 187 (72.8%), Television 108 (42.0%) and Social media 105 (40.9%) (Table 4).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to assess the knowledge, risk perception, and information needs of the people of Osogbo, Osun State, Nigeria, regarding Mpox. The findings provide valuable insights into the community’s awareness and preparedness in the face of a recent Mpox outbreak in the city.

The socio-demographic profile of the study participants reveals some key factors that can influence their awareness and knowledge of Mpox. Most of the partcipants were less than 40 years old and in line the city’s population data which shows that majority of residents are between the ages of 20 and 39 [42]. Furthermore, a considerable proportion of respondents had at least a tertiary education. This finding is in agreement with available data that shows that Osun State has a literacy rate of over 82% [43]. This educational background could have contributed to the study’s relatively high knowledge of Mpox.

According to this study, a significant number of respondents had good knowledge of Mpox including correctly identifying Mpox as a illness that can be transferred from animals to humans. This finding is similar to those reported by Orok et al (2024) where they report good knowledge of Mpox even though among health workers [44]. However, other studies conducted in Saudi Arabia and Jordan showed showed poor to moderate knowledge of Mpox even among healthcare workers and students [45,46]. These discrepancies in knowledge could be de due to regional/coutries exposure to the disease, with awareness evidently higher in endemic countries [44,47]. Knowledge is critical for understanding the originof the disease and transmission, demonstrating that community members are aware of the nature of the sickness. As Bates and Grijalva put it, knowledge of a disease, attitudes toward prevention, and the desire to follow public health advise are major determinants of the adoption of preventive measures, especially in the context of infectious disease such as Mpox [48].

This high knowledge of Mpox could be a direct result of the intensive social mobilization that was done by the Osun State Ministry of Health and partners following the confirmation of the outbreak, a strategy that has been proven to work in such situations [49,50]. However, there were two key misconceptions about Mpox. A significant proportion of participants wrongly felt that Mpox always manifested as a normal rash, which is not the case. This indicates a knowledge gap that must be filled by public health education. Furthermore, a sizable proportion of responders were unaware whether Mpox has a WHO-recommended vaccine.This ambiguity emphasizes the importance of clear and accessible information about disease prevention strategies. These findings are similar to the knowledge gaps identified by Orok et al., 2024, among healthcare workers [44].

Majority of the participants in our study thought that Mpox was indeed a serious illness and many were worried about getting it if precautions were not taken. This is an indication that community awareness of the seriousness of the disease was good and emphasised the significance of public health messaging to promote preventive practices.

A noteworthy finding was quite a number of the residents, after seeing the pictures on the NCDC flyers of the typical Mpox lesions, claimed that they had seen Mpox-like rashes on residents in the past, with some instances dating back several years. This information suggests that Mpox may have been present in the community for a long, potentially going undetected or possibly unreported. This seems to support the observation made by Tomori et al. 2022 about the poor surveillance and possible underreporting of Mpox cases in Africa and highlights the importance of improving disease surveillance andreporting mechanisms to detect and respond to outbreaks promptly [51].

There are several possible reasons for the underreporting of Mpox. Prominent among them is the lack of awareness among healthcare workers often leading to misdiagnosis or a failure to report cases[44–46]. A case in point is a report from a health facility in one of the affected LGAs of two patients who reported to the facility over a month before the outbreak was declared in the state, with fever and maculopapular rash at various parts of the body including the face and palms. These patients were treated but no report was made to the state. Stigma and discrimination associated with Mpox, especially if associated with certain behaviours or groups may cause such individuals to avoid seeking medical care or reporting cases [29,52]. Also, in areas with inadequate healthcare infrastructure, cases may go unreported due to lack of access to diagnostic facilities and reporting mechanisms [51,53,54]. These factors contribute to the challenge of accurately tracking and controlling the spread of mpox. Addressing these issues requires increased awareness, improved healthcare access, and efforts to reduce stigma and discrimination [55].

Our study highlighted a number of community-relevant issues in terms of information needs. Most significantly,respondents said they were very interested in learning more about the transmission and prevention of Mpox. This suggestsa proactive attitude towards protecting themselves and their communities from Mpox. Additionally, there was interest ininformation on Mpox symptoms and treatment, which are critical aspects of disease management. This information was basic, like where to go and what to do if one sees symptoms like the ones in the displayed NCDC flyer carried by enumerators.

Respondents preferred information from the State Ministry of Health or the Nigeria Center for Disease Control (NCDC), suggesting their faith in government health agencies. Radio and television were the preferred mediums for getting information, demonstrating the importance of traditional mass media in conveying public health information. Even with the advent of social media, our study showed that the use of traditional mass media is still very important in outbreak situations as indicated by Anwar et 2020 [56].

Limitations

This study was conducted in two of the four Local Government Areas (LGAs) in Osun State with reported Mpox cases, and the findings may not be entirely generalizable to all areas within the state. Additionally, as with any survey-based research, there may be recall bias and social desirability bias in participants’ responses. However, every effort was made to minimize these biases through proper questionnaire design and interviewer training. The household survey method adapted from WHO guidelines provided valuable insights into the knowledge and perceptions of Mpox among the community members in Osogbo and allowed for a comprehensive assessment of their information needs related to the disease. We were also able to highlight the factthat Mpox cases could have occurred in these communities but were missed or not reported.

Conclusion

This study provides valuable insights into the knowledge, risk perception, and information needs of residents in Osogbo, OsunState, Nigeria, regarding Mpox. While there is a relatively good understanding of the disease, there are areas ofmisconceptions and knowledge gaps that need to be addressed through targeted health education programs. Theperception of Mpox as a severe disease and the willingness to adhere to preventive measures indicate the community’s receptiveness to public health interventions. Importantly, the revelation of past Mpox-like rashes in the community highlights the need for improved disease surveillance and reporting to detect outbreaks early. State public health authorities and the NCDC should prioritize communication strategies that use traditional mass media such as radio and television to disseminate accurate and timely information about Mpox, its transmission, prevention, and where to seek medical help, to the populace.

What is already known about the topic

Mpox is a rare viral disease that can be transmitted from animals to humans.

Due to the similarities between the Mpox virus and the smallpox virus, there are fears the disease could become more severe in future if the virus changes form.

The disease is self-limiting but can be fatal in young children, the elderly and immune-compromised individuals.

Since 2017, there have been continuous outbreaks of Mpox in most parts of Nigeria including all the States in the southwestern parts of Nigeria except Osun State.

What this study adds

This study adds to our understanding of Mpox in Osobo, Osun State, Nigeria, following a recent outbreak and provides important insights into the community’s knowledge, perception, and information needs

The demographic profile of respondents, including a relatively high level of education, influenced their awareness and knowledge of Mpox.

Respondents showed a good understanding of Mpox as a zoonotic disease but had misconceptions about its typical presentation and the availability of a vaccine.

The community perceived Mpox as a severe disease and expressed concerns about contracting it, emphasizing the importance of public health messaging.

Some respondents claimed to have observed Mpox-like rashes in the community in the past, indicating potential underreporting and the need for improved surveillance.

Information needs to be centred around disease transmission, prevention, symptoms, and treatment, with a preference for information from government health authorities through radio and television.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or nonprofit sectors. However, the project was conducted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the award of a certificate of completion of the In-service Veterinary Epidemiology Training Program, coordinated by the Federal Ministry of Agriculture with support from Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations Emergency Centre for Transboundary Animal Diseases (FAO_ECTAD) and partners.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to acknowledge the support of the Osun State Ministry of Health, Osun State Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security, Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, Nigeria Center for Disease Control (NCDC), African Field Epidemiology Network, and Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations Emergency Centre for Transboundary Animal Diseases (FAO_ECTAD).

| Variable | Frequency (N=257) | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||

| <20 | 6 | (2.3%) |

| 20–39 | 147 | (57.2%) |

| 40–59 | 78 | (30.4%) |

| ≥60 | 26 | (10.1%) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 121 | (47.1%) |

| Male | 136 | (52.9%) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 64 | (24.9%) |

| Married | 165 | (64.2%) |

| Divorced | 11 | (4.3%) |

| Widow/Widower | 17 | (6.6%) |

| Highest level of education | ||

| No formal education | 12 | (4.7%) |

| Primary | 22 | (8.6%) |

| Secondary | 95 | (37.0%) |

| Tertiary | 128 | (49.8%) |

| Setting | ||

| Rural | 39 | (15.2%) |

| Semi-urban | 144 | (56.0%) |

| Urban | 74 | (28.8%) |

| What kind of work do you do? | ||

| Artisan (Plumber/carpenter/electrician etc.) | 38 | (14.8%) |

| Civil servant | 64 | (24.9%) |

| Farmer | 19 | (7.4%) |

| Medical or health worker | 16 | (6.2%) |

| Petty trader | 55 | (21.4%) |

| Student | 20 | (7.8%) |

| Unemployed | 14 | (5.5%) |

| Others | 31 | (12.1%) |

| Length of stay in community | ||

| < 1 year | 12 | (4.7%) |

| 1–2 years | 33 | (12.8%) |

| 3–4 years | 87 | (33.9%) |

| ≥5 years | 125 | (48.6%) |

| Question and responses to knowledge about MPOX | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| 1. Mpox can affect only monkeys | |

| Correct | 144 (56.0%) |

| Incorrect | 81 (31.5%) |

| Don’t know | 32 (12.5%) |

| 2. Mpox always shows symptoms of rashes all over the body | |

| Correct | 52 (20.2%) |

| Incorrect | 168 (65.4%) |

| Don’t know | 37 (14.4%) |

| 3. Mpox can be transmitted from animal to humans | |

| Correct | 195 (75.9%) |

| Incorrect | 24 (9.3%) |

| Don’t know | 38 (14.7%) |

| 4. There is a recommended vaccine against Mpox | |

| Correct | 36 (13.3%) |

| Incorrect | 1 (0.4%) |

| Don’t know | 233 (86.3%) |

| 5. Mpox can be prevented by good hand hygiene practices | |

| Correct | 99 (38.5%) |

| Incorrect | 39 (15.2%) |

| Don’t know | 119 (46.3%) |

| Knowledge level | |

| Good | 186 (72.4%) |

| Poor | 71 (27.6%) |

| Question and responses to knowledge about MPX | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| 1. How serious is Mpox? | |

| Don’t know | 51 (19.8%) |

| Not serious at all | 16 (6.2%) |

| Not sure | 59 (23.0%) |

| Serious/Very serious | 131 (51.0%) |

| 2. Do you think you can contract Mpox if you do not take preventive measures? | |

| Yes | 187 (72.8%) |

| No | 25 (9.7%) |

| Don’t know | 45 (17.5%) |

| 3. Do you think you can contract Mpox if you have never taken the Smallpox vaccine? | |

| Yes | 86 (33.5%) |

| No | 51 (19.8%) |

| Don’t know | 120 (46.7%) |

| 4. How concerned are you about contracting Mpox? | |

| Not concerned | 62 (25.1%) |

| Slightly concerned | 77 (31.2%) |

| Very concerned | 108 (43.7%) |

| 5. Do you believe contact with wild animals is a risk factor for Mpox? | |

| Yes | 182 (70.8%) |

| No | 29 (11.3%) |

| Don’t know | 46 (17.9%) |

| 6. Will you keep away from contact with wildlife including eating bush meat as advised by health authorities? | |

| Yes | 191 (74.3%) |

| No | 25 (9.7%) |

| Don’t know | 41 (16.0%) |

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| *What are the most important topics about Mpox that you want to know about? | |

| 1. How Mpox is transmitted | 134 (52.1%) |

| 2. How Mpox can be prevented | 179 (69.7%) |

| 3. Symptoms of Mpox | 116 (45.1%) |

| 4. How Mpox can be treated | 165 (64.2%) |

| 5. I do not need any information | 16 (6.2%) |

| *Who would you like to provide you with the information? | |

| 1. State Ministry of Health | 198 (77.0%) |

| 2. State Ministry of Agriculture | 48 (18.7%) |

| 3. Federal Ministry of Agriculture | 56 (21.8%) |

| 4. Nigeria Center for Disease Control (NCDC) | 132 (51.4%) |

| 5. Local Government Health Authorities | 86 (33.5%) |

| *How would you like to receive the information? | |

| 1. Mosque/Church | 53 (20.6%) |

| 2. Newspaper | 90 (35.0%) |

| 3. Radio | 187 (72.8%) |

| 4. Television | 108 (42.0%) |

| 5. Social media | 105 (40.9%) |

| 6. Town announcer | 8 (3.0%) |

References

- Gong Q, Wang C, Chuai X, Chiu S. Monkeypox virus: a re-emergent threat to humans. Virol Sin. 2022;37(4):477-82. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9437600/pdf/main.pdf

- Rodríguez-Morales AJ, Ortiz-Martínez Y, Bonilla-Aldana DK. What has been researched about monkeypox? a bibliometric analysis of an old zoonotic virus causing global concern. New Microbes New Infect. 2022;47:100993. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9243150/pdf/main.pdf

- Essbauer S, Pfeffer M, Meyer H. Zoonotic poxviruses. Vet Microbiol. 2010;140(3):229-36. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9628791/pdf/main.pdf

- World Health Organization (African Region). Outbreaks and other emergencies. Brazzaville (Congo): World Health Organization; 2022 [cited 2025 May 6]. https://www.afro.who.int/publications/outbreaks-and-emergencies-bulletin-week-39-19-25-september-2022

- Uwishema O, Adekunbi O, Peñamante CA, Bekele BK, Khoury C, Mhanna M, Nicholas A, Adanur I, Dost B, Onyeaka H. The burden of monkeypox virus amidst the Covid-19 pandemic in Africa: a double battle for Africa. Ann Med Surg. 2022;80:104197. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35855873

- Hughes L, Wilkins K, Goldsmith CS, Smith S, Hudson P, Patel N, Karem K, Damon I, Li Y, Olson VA, Satheshkumar PS. A rapid Orthopoxvirus purification protocol suitable for high-containment laboratories. J Virol Methods. 2017;243:68-73. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0166093416304852?via%3Dihub

- Yinka-Ogunleye A, Aruna O, Ogoina D, Aworabhi N, Eteng W, Badaru S, Mohammed A, Agenyi J, Etebu EN, Numbere TW, Ndoreraho A, Nkunzimana E, Disu Y, Dalhat M, Nguku P, Mohammed A, Saleh M, McCollum A, Wilkins K, Faye O, Sall A, Happi C, Mba N, Ojo O, Ihekweazu C. Reemergence of human monkeypox in Nigeria, 2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(6):1149-51. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/24/6/18-0017_article

- Petersen E, Abubakar I, Ihekweazu C, Heymann D, Ntoumi F, Blumberg L, Asogun D, Mukonka V, Lule SA, Bates M, Honeyborne I, Mfinanga S, Mwaba P, Dar O, Vairo F, Mukhtar M, Kock R, McHugh TD, Ippolito G, Zumla A. Monkeypox – enhancing public health preparedness for an emerging lethal human zoonotic epidemic threat in the wake of the smallpox post-eradication era. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;78:78-84. https://www.ijidonline.com/article/S1201-9712(18)34587-9/fulltext

- Mandja BA, Handschumacher P, Bompangue D, Gonzalez JP, Muyembe JJ, Sauleau EA, Mauny F. Environmental drivers of monkeypox transmission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Ecohealth. 2022;19(3):354-64. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10393-022-01610-x

- Mukherjee AG, Wanjari UR, Kannampuzha S, Das S, Murali R, Namachivayam A, Renu K, Ramanathan G, Doss CGP, Vellingiri B, Dey A, Velayutham GA. The pathophysiological and immunological background of the monkeypox virus infection: an update. J Med Virol. 2023;95(1):e28206. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jmv.28206

- World Health Organization. Multi-country outbreak of monkeypox. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2022 [cited 2025 Apr 30]. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20221116_monkeypox_external_sitrep-10_cleared.pdf

- Beer EM, Bhargavi Rao V. A systematic review of the epidemiology of human monkeypox outbreaks and implications for outbreak strategy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(10):e0007791. https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0007791

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Monkeypox multi-country outbreak. Stockholm (Sweden): European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2022. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Monkeypox-multi-country-outbreak.pdf

- Vivancos R, Anderson C, Blomquist P, Balasegaram S, Bell A, Bishop L, Brown CS, Chow Y, Edeghere O, Florence I, Logan S, Manley P, Crowe W, McAuley A, Shankar AG, Mora-Peris B, Paranthaman K, Prochazka M, Ryan C, Simons D, Vipond R, Byers C, Watkins NA, Welfare W, Whittaker E, Dewsnap C, Wilson A, Young Y, Chand M, Riley S, Hopkins S; UKHSA Monkeypox Incident Management team. Community transmission of monkeypox in the United Kingdom, April to May 2022. Eurosurveillance. 2022;27(22):1-5. https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.22.2200422

- Heymann DL, Szczeniowski M, Esteves K. Re-emergence of monkeypox in Africa: a review of the past six years. Br Med Bull. 1998;54(3):693-702. https://academic.oup.com/bmb/article-abstract/54/3/693/284439

- World Health Organization (Regional Office for Africa). Weekly bulletin on outbreak and other emergencies: week 4: 17 – 23 January 2022. Brazzaville (Congo): World Health Organization; 2022. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/351164

- Diaz JH. The disease ecology, epidemiology, clinical manifestations, management, prevention, and control of increasing human infections with animal orthopoxviruses. Wilderness Environ Med. 2021;32(4):528-36. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1016/j.wem.2021.08.003

- Quarleri J, Delpino MV, Galvan V. Monkeypox: considerations for the understanding and containment of the current outbreak in non-endemic countries. GeroScience. 2022;44(4):2095-103. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11357-022-00611-6

- World Health Organization. Monkeypox. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2022 [cited 2025 Apr 30]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mpox

- Raccagni AR, Candela C, Mileto D, Canetti D, Bruzzesi E, Rizzo A, Castagna A, Nozza S. Monkeypox infection among men who have sex with men: PCR testing on seminal fluids. J Infect. 2022;84(5):573-607. https://www.journalofinfection.com/article/S0163-4453(22)00449-2/fulltext

- Thornhill JP, Barkati S, Walmsley S, Rockstroh J, Antinori A, Harrison LB, Palich R, Nori A, Reeves I, Habibi MS, Apea V, Boesecke C, Vandekerckhove L, Yakubovsky M, Sendagorta E, Blanco JL, Florence E, Moschese D, Maltez FM, Goorhuis A, Pourcher V, Migaud P, Noe S, Pintado C, Maggi F, Hansen AE, Hoffmann C, Lezama JI, Mussini C, Cattelan A, Makofane K, Tan D, Nozza S, Nemeth J, Klein MB, Orkin CM; SHARE-net Clinical Group. Monkeypox virus infection in humans across 16 countries – April-June 2022. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(8):679-91. https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa2207323

- Zhu F, Li L, Che D. Monkeypox virus under COVID-19: caution for sexual transmission – correspondence. Int J Surg. 2022;104:106768. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1743919122005453?via%3Dihub

- Jagadesh S, Zhao C, Mulchandani R, Van Boeckel TP. Mapping global bushmeat activities to improve zoonotic spillover surveillance by using geospatial modeling. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29(4):742-50. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/29/4/22-1022_article

- Coad L, Abernethy K, Balmford A, Manica A, Airey L, Milner-Gulland EJ. Distribution and use of income from bushmeat in a rural village, central Gabon. Conserv Biol. 2010;24(6):1510-8. https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01525.x

- Benites-Zapata VA, Ulloque-Badaracco JR, Alarcon-Braga EA, Hernandez-Bustamante EA, Mosquera-Rojas MD, Bonilla-Aldana DK, Rodriguez-Morales AJ. Clinical features, hospitalisation and deaths associated with monkeypox: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2022;21(1):36. https://ann-clinmicrob.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12941-022-00527-1

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical features of mpox. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2024 [cited 2025 May 2]. https://www.cdc.gov/mpox/hcp/clinical-signs/index.html

- Jezek Z, Szczeniowski M, Paluku KM, Mutombo M. Clinical characteristics of human monkeypox, and risk factors for severe disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(12):1742-51. https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/41/12/1742/344953

- Yinka-Ogunleye A, Aruna O, Dalhat M, Ogoina D, McCollum A, Disu Y, Mamadu I, Akinpelu A, Ahmad A, Burga J, Ndoreraho A, Nkunzimana E, Manneh L, Mohammed A, Adeoye O, Tom-Aba D, Silenou B, Ipadeola O, Saleh M, Adeyemo A, Nwadiutor I, Aworabhi N, Uke P, John D, Wakama P, Reynolds M, Mauldin MR, Doty J, Wilkins K, Musa J, Khalakdina A, Adedeji A, Mba N, Ojo O, Krause G, Ihekweazu C; CDC Monkeypox Outbreak Team. Outbreak of human monkeypox in Nigeria in 2017–18: a clinical and epidemiological report. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(8):872-9. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(19)30294-4/fulltext

- World Health Organization. Disease outbreak news – multi-country monkeypox outbreak: situation update. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2022 [cited 2022 Aug 21]. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON396

- Nigeriascholars.com. Vegetation zones in Nigeria. 2022 [cited 2025 May 2]. https://nigerianscholars.com/tutorials/ecology-overview/nigerian-biomes/

- Khodakevich L, Jezek Z, Messinger D. Monkeypox virus: ecology and public health significance. Bull World Health Organ. 1988;66(6):747-52. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2491157/

- Federal Ministry of Health (Nigeria), Nigeria Centre for Disease Control. National monkeypox public health response guideline. Abuja (Nigeria): Federal Ministry of Health; 2019. https://ncdc.gov.ng/themes/common/docs/protocols/96_1577798337.pdf

- Federal Ministry of Health (Nigeria), Nigeria Center for Disease Control. Update on monkeypox (MPX) in Nigeria. Abuja (Nigeria): Federal Ministry of Health; 2022. https://ncdc.gov.ng/diseases/sitreps/?cat=8&name=An

- Brown K, Leggat PA. Human monkeypox: current state of knowledge and implications for the future. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2016;1(1):8. https://www.mdpi.com/2414-6366/1/1/8

- Cadmus S, Besong M, Akinseye V, Ayanwale S, Ayinmode A, Oluwayelu D, Ebenyi H, Fowotade A, Olisa M, Sampson E, Nwanga E, Gabriel Orum T, Alayande O, Ansumana R, Cadmus E, Otu S. Non-exanthematous mpox infections in Nigeria: a possible explanation of the sporadic outbreaks in city centers? PAMJ. 2025;50(1):7. https://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/series/50/1/7/full/

- Rath RS, Shrestha H. Review of lot quality assurance sampling, methodology and its application in public health. Nepal J Epidemiol. 2019;9(3):781-7. https://www.nepjol.info/index.php/NJE/article/view/24507

- Measure Evaluation. Facts about lot quality assurance sampling. New York (NC): Measure Evaluation; 2024 [cited 2025 May 5]. https://www.measureevaluation.org/resources/tools/fact-sheet-available-on-lot-quality-assurance-sampling

- Osun State (Nigeria). Osogbo. 2022 [cited 2025 May 5]. https://www.osunstate.gov.ng/about/major-towns/osogbo/

- Aremu O, Adetoro O, Awotoye O. Assessment of diversity, growth characteristics and aboveground biomass of tree species in selected urban green areas of Osogbo, Osun State. IntechOpen. 2022. https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/82124

- Ogunfolakan A, Nwokeocha C, Olayemi A, Olayiwola M, Bamigboye A, Olayungbo A, Ogiogwa J, Oyelade O, Oyebanjo O. Rapid ecological and environmental assessment of Osun Sacred Forest Grove, Southwestern Nigeria. Open Journal of Forestry. 2016;6(4):243-58. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojf

- Municipal Public Health Service Rotterdam-Rijnmond (GGD), National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) (Netherlands). Standard questionnaire on risk perception. Amsterdam (Netherlands): Municipal Public Health Service Rotterdam-Rijnmond (GGD); 2015. http://ecomeu.info/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Standard-questionnaire-risk-perception-ECOM-november-2015.pdf

- City-facts. Oshogbo, Osun, Nigeria. Oshogbo Osun (Nigeria): City-facts; 2022 [cited 2025 May 5]. https://www.city-facts.com/osogbo/population

- Knoema. Osun. 2022 [cited 2025 May 5]. https://knoema.com/atlas/Nigeria/Osun

- Orok E, Adele G, Oni O, Adelusi A, Bamitale T, Jaiyesimi B, Saka A, Apara T. Assessment of knowledge and attitude of healthcare professionals towards mpox in a Nigerian hospital. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):27604. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-79396-x

- Alshahrani NZ, Alzahrani F, Alarifi AM, Algethami MR, Alhumam MN, Ayied HAM, Awan AZ, Almutairi AF, Bamakhrama SA, Almushari BS, Sah R. Assessment of knowledge of monkeypox viral infection among the general population in Saudi Arabia. Pathogens. 2022;11(8):904. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0817/11/8/904

- Sallam M, Al-Mahzoum K, Dardas LA, Al-Tammemi AB, Al-Majali L, Al-Naimat H, Jardaneh L, AlHadidi F, Al-Salahat K, Al-Ajlouni E, AlHadidi NM, Bakri FG, Mahafzah A, Harapan H. Knowledge of human monkeypox and its relation to conspiracy beliefs among students in Jordanian health schools: filling the knowledge gap on emerging zoonotic viruses. Medicina. 2022;58(7):924. https://www.mdpi.com/1648-9144/58/7/924

- Tanashat M, Altobaishat O, Sharaf A, Hossam El Din Moawad M, Al-Jafari M, Nashwan AJ. Assessment of the knowledge, attitude, and perception of the world’s population towards monkeypox and its vaccines: a systematic review and descriptive analysis of cross-sectional studies. Vaccine: X. 2024;20:100527. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2590136224001001

- Bates BR, Grijalva MJ. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards monkeypox during the 2022 outbreak: an online cross-sectional survey among clinicians in Ohio, USA. Journal of Infection and Public Health. 2022;15(12):1459-65. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1876034122002982

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Technical report 1: multi-national mpox outbreak, United States, 2022. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2022 [cited 2025 May 2]. https://archive.cdc.gov/#/details?url=https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/cases-data/technical-report/report-1.html

- Roma W. Empowering communities: the role of health education in preventive care. J Public Heal Policy Plan. 2023;7(6):206. https://www.alliedacademies.org/public-health-policy-planning/

- Tomori O, Ogoina D. Monkeypox: the consequences of neglecting a disease, anywhere. Science. 2022;377(6612):1261-3. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.add3668

- Heskin J, Belfield A, Milne C, Brown N, Walters Y, Scott C, Bracchi M, Moore LS, Mughal N, Rampling T, Winston A, Nelson M, Duncan S, Jones R, Price DA, Mora-Peris B. Transmission of monkeypox virus through sexual contact – a novel route of infection. Journal of Infection. 2022;85(3):334-63. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0163445322003358

- Haider N, Guitian J, Simons D, Asogun D, Ansumana R, Honeyborne I, Velavan TP, Ntoumi F, Valdoleiros SR, Petersen E, Kock R, Zumla A. Increased outbreaks of monkeypox highlight gaps in actual disease burden in Sub-Saharan Africa and in animal reservoirs. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2022;122:107-11. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1201971222003228

- Beer EM, Rao VB. A systematic review of the epidemiology of human monkeypox outbreaks and implications for outbreak strategy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(10):e0007791. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007791

- World Health Organization. Monkeypox. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2024 [cited 2025 Apr 30]. httpsajes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2022;21(1):36. Available from: [https://ann-clinmicrob.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12941-022-00527-1](https://ann-clinmicrob.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12941-022-00527-1) https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-022-00527-1

- Anwar A, Malik M, Raees V, Anwar A. Role of mass media and public health communications in the COVID-19 pandemic. Cureus. 2020;12(9):e10453. https://www.cureus.com/articles/38293-role-of-mass-media-and-public-health-communications-in-the-covid-19-pandemic

Menu, Tables and Figures

Navigate this article

Tables

| Variable | Frequency (N=257) | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||

| <20 | 6 | (2.3%) |

| 20–39 | 147 | (57.2%) |

| 40–59 | 78 | (30.4%) |

| ≥60 | 26 | (10.1%) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 121 | (47.1%) |

| Male | 136 | (52.9%) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 64 | (24.9%) |

| Married | 165 | (64.2%) |

| Divorced | 11 | (4.3%) |

| Widow/Widower | 17 | (6.6%) |

| Highest level of education | ||

| No formal education | 12 | (4.7%) |

| Primary | 22 | (8.6%) |

| Secondary | 95 | (37.0%) |

| Tertiary | 128 | (49.8%) |

| Setting | ||

| Rural | 39 | (15.2%) |

| Semi-urban | 144 | (56.0%) |

| Urban | 74 | (28.8%) |

| What kind of work do you do? | ||

| Artisan (Plumber/carpenter/electrician etc.) | 38 | (14.8%) |

| Civil servant | 64 | (24.9%) |

| Farmer | 19 | (7.4%) |

| Medical or health worker | 16 | (6.2%) |

| Petty trader | 55 | (21.4%) |

| Student | 20 | (7.8%) |

| Unemployed | 14 | (5.5%) |

| Others | 31 | (12.1%) |

| Length of stay in community | ||

| < 1 year | 12 | (4.7%) |

| 1–2 years | 33 | (12.8%) |

| 3–4 years | 87 | (33.9%) |

| ≥5 years | 125 | (48.6%) |

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of respondents, Mpox risk perception survey in Osun State, Nigeria 2022

| Question and responses to knowledge about MPOX | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| 1. Mpox can affect only monkeys | |

| Correct | 144 (56.0%) |

| Incorrect | 81 (31.5%) |

| Don’t know | 32 (12.5%) |

| 2. Mpox always shows symptoms of rashes all over the body | |

| Correct | 52 (20.2%) |

| Incorrect | 168 (65.4%) |

| Don’t know | 37 (14.4%) |

| 3. Mpox can be transmitted from animal to humans | |

| Correct | 195 (75.9%) |

| Incorrect | 24 (9.3%) |

| Don’t know | 38 (14.7%) |

| 4. There is a recommended vaccine against Mpox | |

| Correct | 36 (13.3%) |

| Incorrect | 1 (0.4%) |

| Don’t know | 233 (86.3%) |

| 5. Mpox can be prevented by good hand hygiene practices | |

| Correct | 99 (38.5%) |

| Incorrect | 39 (15.2%) |

| Don’t know | 119 (46.3%) |

| Knowledge level | |

| Good | 186 (72.4%) |

| Poor | 71 (27.6%) |

Table 2: Study participants’ responses to questions on knowledge of Mpox in Osun State, 2022

| Question and responses to knowledge about MPX | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| 1. How serious is Mpox? | |

| Don’t know | 51 (19.8%) |

| Not serious at all | 16 (6.2%) |

| Not sure | 59 (23.0%) |

| Serious/Very serious | 131 (51.0%) |

| 2. Do you think you can contract Mpox if you do not take preventive measures? | |

| Yes | 187 (72.8%) |

| No | 25 (9.7%) |

| Don’t know | 45 (17.5%) |

| 3. Do you think you can contract Mpox if you have never taken the Smallpox vaccine? | |

| Yes | 86 (33.5%) |

| No | 51 (19.8%) |

| Don’t know | 120 (46.7%) |

| 4. How concerned are you about contracting Mpox? | |

| Not concerned | 62 (25.1%) |

| Slightly concerned | 77 (31.2%) |

| Very concerned | 108 (43.7%) |

| 5. Do you believe contact with wild animals is a risk factor for Mpox? | |

| Yes | 182 (70.8%) |

| No | 29 (11.3%) |

| Don’t know | 46 (17.9%) |

| 6. Will you keep away from contact with wildlife including eating bush meat as advised by health authorities? | |

| Yes | 191 (74.3%) |

| No | 25 (9.7%) |

| Don’t know | 41 (16.0%) |

Table 3: Responses of study participants to questions on perception of risk of Mpox in Osun State, 2022

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| *What are the most important topics about Mpox that you want to know about? | |

| 1. How Mpox is transmitted | 134 (52.1%) |

| 2. How Mpox can be prevented | 179 (69.7%) |

| 3. Symptoms of Mpox | 116 (45.1%) |

| 4. How Mpox can be treated | 165 (64.2%) |

| 5. I do not need any information | 16 (6.2%) |

| *Who would you like to provide you with the information? | |

| 1. State Ministry of Health | 198 (77.0%) |

| 2. State Ministry of Agriculture | 48 (18.7%) |

| 3. Federal Ministry of Agriculture | 56 (21.8%) |

| 4. Nigeria Center for Disease Control (NCDC) | 132 (51.4%) |

| 5. Local Government Health Authorities | 86 (33.5%) |

| *How would you like to receive the information? | |

| 1. Mosque/Church | 53 (20.6%) |

| 2. Newspaper | 90 (35.0%) |

| 3. Radio | 187 (72.8%) |

| 4. Television | 108 (42.0%) |

| 5. Social media | 105 (40.9%) |

| 6. Town announcer | 8 (3.0%) |

* Question allowed for multiple responses.

Table 4: Communication needs of respondents with regards to Mpox following the Osun State outbreak, 2022

Figures

Keywords

- Monkeypox

- Risk perception

- Osun State

- Nigeria