Research![]() | Volume 8, Article 34, 14 May 2025

| Volume 8, Article 34, 14 May 2025

Evaluation of the palliative care program in patients with tuberculosis in Chirumhanzu District, Zimbabwe, 2021-2023

Victoria Varaidzo Kandido1, Ronald Ncube2, Sithabiso Dube2, Addmore Chadambuka3, Gerald Shambira1, Gibson Mandozana1, Notion Gombe4, Tsitsi Juru3, Mufuta Tshimanga1, Jeconiah Chirenda1

1University of Zimbabwe, Department of Global Public Health and Family Medicine, Harare, Zimbabwe, 2The Union Zimbabwe Trust, Harare, Zimbabwe, 3Zimbabwe Field Epidemiology Training Program, Harare, Zimbabwe, 4African Field Epidemiology Network, Harare, Zimbabwe

&Corresponding author: Addmore Chadambuka, Zimbabwe Field Epidemiology Training Program, Harare, Zimbabwe. Email address: achadambuka1@yahoo.co.uk

Received: 06 Dec 2024, Accepted: 24 Apr 2025, Published: 14 May 2025

Domain: Infectious Disease Epidemiology, Tuberculosis Control

Keywords: Kunda-Nqob’I TB, Palliative Care, Tuberculosis, Unfavourable outcomes, Zimbabwe

©Victoria Varaidzo Kandido et al Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Victoria Varaidzo Kandido et al Evaluation of the palliative care program in patients with tuberculosis in Chirumhanzu District, Zimbabwe, 2021-2023. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8:34. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-24-02011

Abstract

Introduction: The Kunda-Nqob’I TB program introduced the full package of Palliative Care to improve quality of life and treatment results for patients with tuberculosis (TB). The components of Palliative care include treatment adherence, physical, and psychosocial support. The physical support provides pain relief, while psychosocial support involves counselling patients to cope with the stress associated with TB. Treatment adherence included directly observed treatment by a community-based volunteer. Among the five districts in the Midlands province implementing Palliative Care, Chirumhanzu had the highest proportion of deaths in 2022.

Methods: We conducted an analytical cross-sectional study with a retrospective record review to evaluate the Palliative Care program among patients with TB. We enrolled 125 health workers and community-based volunteers and reviewed 60 records. Checklists were used to assess inputs, and TB registers were reviewed to assess the outputs, and the package of palliative care received.

Results: HIV- positive [aPOR= 10.52 (95% CI 1.83-60.6)], extrapulmonary [ aPOR= 6.8 (95% CI 1.46- 405)], and retreatment [aPOR= 11.4 (95% CI 1.75- 74.11)] were risk factors for unfavourable TB treatment outcomes. Health workers and community-based volunteers lacked knowledge. All facilities had human resources and registers. All six support and supervision visits were conducted. Among the 60 patients,46 (76%) received treatment adherence only, and 22 (36%) had unfavourable outcomes.

Conclusion: HIV, extrapulmonary TB. and retreatment were associated with unfavourable TB treatment outcomes. While resources were adequate, most patients received treatment adherence only. The study highlights the need to address knowledge gaps among healthcare workers to improve treatment outcomes.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a preventable and curable disease, yet in 2022, globally, it was the second leading cause of death from a single infectious agent, after coronavirus disease (COVID-19), and caused almost twice as many deaths as HIV/AIDS. An estimated 10.6 million individuals worldwide fell ill with TB in 2022, with 1.3 million associated deaths [1,2]. Without treatment, the death rate from TB disease is high (about 50%), but with treatment currently recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), about 85% of people with TB can be cured [3]. High mortality of TB can be averted through prompt diagnosis, effective treatment, and proper support for TB patients and their families [4]

The WHO adopted the global End TB Strategy in March 2014 to reduce global TB incidence by 80%, decrease TB deaths by 90% from the 2015 baseline, and eliminate catastrophic costs for TB-affected households by 2035 [5,6]. The assumption was that new tools would have been developed and deployed to accelerate aspirations to achieve regional and global targets [6]. The WHO recognized palliative care (PC) as an essential component in the management of TB in November 2010. In May 2014, the World Health Assembly (WHA) directed member states to integrate PC into public health systems [7] . PC has the potential to improve TB treatment outcomes, reduce healthcare costs and provide financial risk protection for patients’ families while enhancing their quality of life. It may help patients adhere to long and difficult treatments, reducing mortality and protecting public health [6]. The PC program for TB patients aims to improve the quality of life and treatment outcomes for both patients and their families.

Zimbabwe began implementing the full Palliative Care program for TB patients in 2021 through the Kunda-Nqob;iTB programme, supported by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) across eight high-burden priority districts with relatively poor treatment outcomes at baseline. The implementation of Palliative Care was expected to improve treatment outcomes in selected districts that had previously experienced suboptimal TB treatment outcomes. These districts are namely: Gweru, Kwekwe, Chirumanzu, Zvishavane, Gwanda, Insiza, Shurugwi, and Mwenezi, five of which are from the Midlands Province. The full package of palliative care included several key components which were treatment adherence, physical health and psychosocial well- being. The physical support component focused on pain relief and management of symptoms such as shortness of breath, cough, and fatigue.

The psychosocial support was designed to assist TB patients and their families in coping with the stress associated with the disease, addressing issues such as anxiety, depression and fear of death. This support also helped patients maintain relationships with their relatives [8].

Treatment adherence refers to the extent to which a patient’s behaviour aligns with the recommendations prescribed by a health worker. In our study, a method called the Directly Observed Treatment (DOT) was implemented. This involved a healthcare worker or a trained community-based volunteer observing the patient as they take each dose of their prescribed medication. Additionally, community-based volunteers conducted pill counts of TB medicines and monitored any side effects experienced by patients as part of ensuring treatment adherence. These processes were crucial for ensuring that patients follow their prescribed treatment regime, which is essential for effectively curing TB and preventing the emergency of drug resistance. [9,10]. Among the five districts in the Midlands Province implementing Palliative Care, Chirumhanzu had the highest proportion of deaths (Table 1). This concerning trend in TB mortality was identified during death audits conducted in the district. Notably, this occurred despite the implementation of the Palliative Care package intended to improve treatment outcomes since the second quarter of 2021. Negative treatment outcomes indicate poor program performance.

In response to these findings, we conducted the first program evaluation of Palliative Care in the Chirumanzu District. The objectives of the study were to:

Determine factors associated with unfavourable outcomes among TB patients who received Palliative Care,

Assess health worker knowledge of the PC program in patients diagnosed with TB from April 2021 to September 2023

Evaluate resources provided for the Palliative Care program

Assess the processes involved in providing Palliative Care to patients with TB

Analyze the outputs of Palliative Care in patients with TB

Evaluate the outcomes of TB patients who had received palliative care

Since the introduction of Palliative Care in TB care was a new concept, this evaluation was essential to assess its implementation fidelity and to provide evidence-based recommendations to improve implementation delivery in the Chirumanzu District and upscale of the program to other districts in Zimbabwe.

Methods

Study type

The study was an analytic cross-sectional study with a secondary data review of the district TB programme.

Study setting

The study was conducted in the Chirumanzu District, in the Midlands Province. The district has a population of 105,500 and is home to 22 health facilities, which include four hospitals and several clinics. Seventeen of these facilities are in communal areas in the southern part of the district, while five are in the northern part of the district, serving resettlement areas. The district hospital primarily provides services to the resettlement areas through outreach and walk-in clients. Additionally, gold and chrome mining activities, including small-scale mining are common throughout the district.

Study Population

Our study population included healthcare workers (HCWs) and community-based volunteers (CBVs) who provided Palliative Care to TB patients between April 2021 and September 2023. TB registers were reviewed to assess Palliative Care components received by patients with TB and their outcomes for the period from April 2021 to September 2023.

Sample size calculation

STATCALC function in Epi Info 7 was used to calculate the minimum sample size of health workers recruited, from a population of 186 health workers in Chirumhanzu, (including community-based volunteers) assuming the expected frequency of 50.9% for knowledge on PC from a study by Bilal et al [10], using a 95% confidence level, an acceptable margin of error set at 5%, design effect and clusters value set at 1, the minimum sample size for the study was 125.

We included all medical records for the 60 notified Tuberculosis patients who received PC in Chirumhanzu District between April 2021 and September 2023 from the selected 14 health facilities in the district.

Inclusion criteria for TB patients

Patients diagnosed with TB from April 2021 to September 2023 received Palliative Care during their treatment phase in the Chirumhanzu District.

Exclusion criteria for TB patients

Records for TB patients with missing data, including demographics and components of palliative care, were excluded from the study.

Inclusion criteria for healthcare workers and community-based volunteers

We included healthcare workers and community-based volunteers who were trained in palliative care for patients with TB from 14 selected health facilities in the district. The selected healthcare workers and community-based volunteers were involved in management and care of TB patients during the study period.

Exclusion criteria for healthcare workers and community-based volunteers

Healthcare workers and community-based volunteers who were trained in palliative care of TB patients but not present during the study period were excluded from the study.

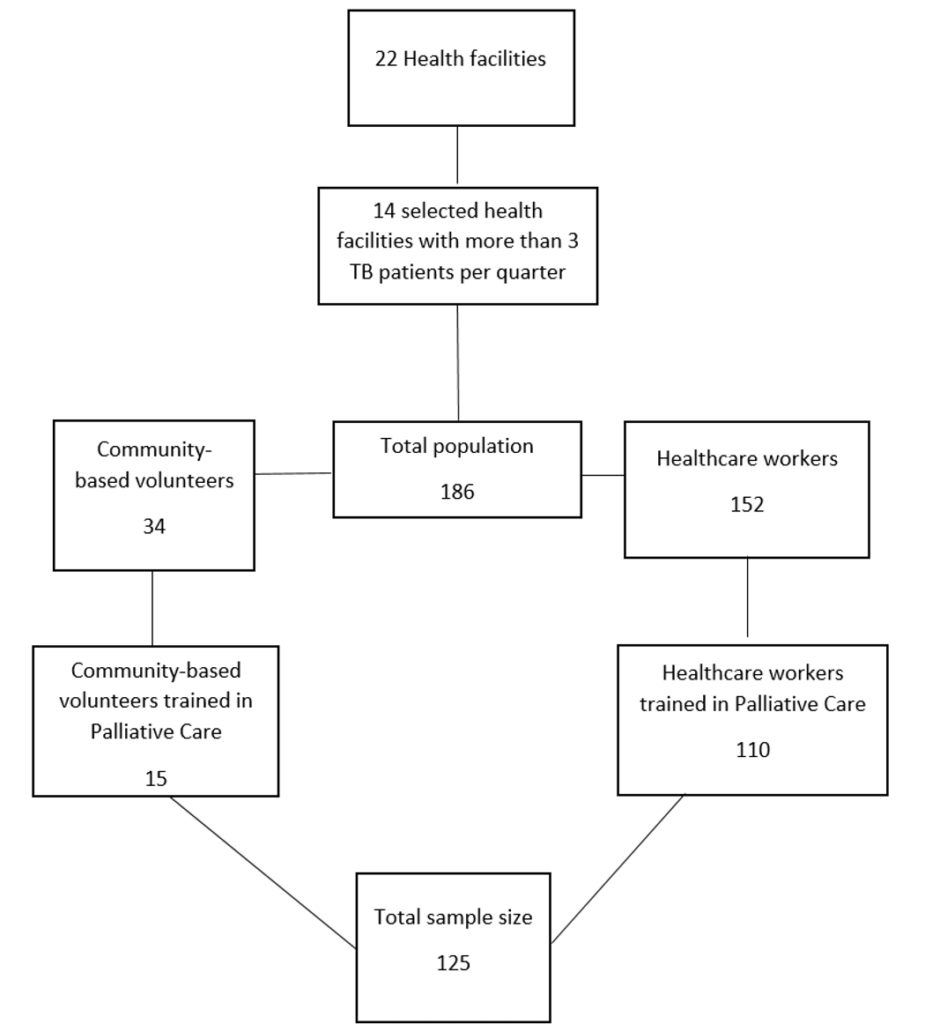

Sampling

We purposively sampled 14 health facilities that offered palliative care services to more than three TB patients per quarter. To determine the sample size, we used proportional sampling; health facilities with a larger number of health workers contributed a more significant proportion of respondents to the study compared to clinics with fewer staff members. Our sample size was selected from a population of 186 individuals, consisting of healthcare workers and community-based volunteers from the 14 selected health facilities. In total, there were 152 healthcare workers across these facilities, out of which 110 trained were chosen for the study. Additionally, from a group of 34 community-based volunteers, 15 who had received training in palliative care for TB patients were selected to participate in the study. In total, we reviewed all 60 TB patient records from the 14 selected health facilities in the district. The sampling procedure for the study participants is shown in Figure 1.

Data collection

Interviewer-administered questionnaires collected demographic data on age, sex, type of respondents (registered general nurse, primary care nurse or community-based volunteer), and the duration of working in the district. Factors associated with unfavourable TB treatment outcomes in patients who had received palliative care included HIV-positive status, site of TB, type of TB patient, sex, and the presence of diabetes mellitus and the components of Palliative Care received. Knowledge assessment covered the definition of palliative care, the palliative care package for TB patients, signs are symptoms of TB, TB treatment outcomes and benefits of palliative care to patients with TB. A checklist was utilized to capture inputs, which included the availability of the 2023 TB guidelines, TB registers, palliative care manual, trained personnel in palliative care, home visits register and the palliative care registers. Another checklist captured outputs focusing on health workers trained in palliative care and the number of TB patients who received such care. The outcome checklist concentrated on several factors: the number of health workers with adequate knowledge of palliative care program for TB patients, the number of TB patients who were cured, those who completed their treatment, those lost to follow-up, those with TB treatment failed and those not evaluated for TB treatment outcomes.

For data handling, all questionnaires and checklists were securely stored in a lockable cabinet. The questionnaires were entered into EPI info version 7 on a password-protected laptop and access to the laptop was restricted to the researcher and their supervisors.

Data cleaning was performed prior to data analysis. Multivariate analysis and logistic regression analysis were conducted to identify factors associated with unfavourable TB treatment outcomes. Adjusted prevalence odds ratios (POR) were calculated to account for potential confounding variables. In the multivariate logistic regression, variables from the bivariate analysis that had a p-value of less than 0.25 were included to determine independent factors linked to unfavourable TB treatment outcomes. The adjusted POR with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were then calculated to establish an independent association for each variable. Variables with a p-value of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The results of the data analysis were presented in tables.

Data analysis

Data was captured and analysed using Epi Info 7.2.4 statistical package, generating frequencies, means and proportions. Health worker’s knowledge of the TB program was assessed using a Likert score, where a maximum of one correct response for each question indicated poor knowledge. Two to three correct responses were fair knowledge and more than 3 correct responses were good knowledge. A mean knowledge score was computed for each respondent. Bivariate and multivariate analysis were performed to come up with independent factors associated with unfavourable TB treatment outcomes among patients who had received Palliative Care.

Tuberculosis treatment outcomes were categorized into two groups: favourable and unfavourable. Unfavourable outcomes included death, not evaluated, treatment failure, and loss of follow-up (LTFU) during treatment. Favourable outcomes included cured and treatment completed.

Ethical considerations

We obtained permission from the Midlands Provincial Medical Director (PMD), the Union Zimbabwe Trust, and the District Health Executive to carry out the study. The protocol received ethical approval from the Health Studies Office (HSO) (HSO/13/2023). An informed consent was obtained from each respondent and abstracted data from registers were anonymized. Participant names were not captured during data collection.

Results

Demographic characteristics of healthcare workers and community-based volunteers

The study enrolled 125 respondents. Among these, the majority, 72.8% (n = 91), were female. Most of the participants (67.2%) were registered general nurses who work in Chirumanzu District. The median years of service since joining the Chirumhanzu District was 10 years (Q1 = 5; Q3 = 18) (Table 2).

Demographic details of patients who received PC

All 60 notified patients with TB who received Palliative Care from the selected 14 health facilities were included in our study. Among these, 45 (75%) were males. The median age in years was 37.5 (Q1=32, Q3=46). The majority 56 (93.3%) had pulmonary TB. Out of the 60 TB patients, 34 (56.7%) were HIV positive and 28 (46.7%) were diabetic. Among the 60 TB patients who received Palliative Care, 22 (36.7%) had unfavourable outcomes defined.

Factors associated with unfavorable TB treatment outcomes

After adjusting for confounding variables, the odds of experiencing unfavorable TB treatment outcomes among HIV-positive TB patients were ten times higher (aPOR=10.52, 95% CI: 1.83-60.6) compared to those who were HIV-negative. In logistic regression, patients with a previous history of TB treatment were 11 times more likely (95% CI: 1.75-74.11) to experience unfavorable outcomes compared to patients who were undergoing their first episode of TB. This association was statistically significant. Additionally, TB patients who had extrapulmonary TB faced approximately a 76.8-fold increased risk (95% CI: 1.46-405) of unfavorable treatment outcomes compared to pulmonary TB patients, and this finding was also significant. In the bivariate analysis, the full package of palliative care seemed to reduce the likelihood of unfavourable TB treatment outcomes among TB patients. However, the result was not statistically significant (cPOR= 0.68, 96% C1 (0.16-2.86))as shown in Table 3.

Health worker Knowledge of PC and TB

Eight-six (69%) of the 125 respondents articulated that Palliative Care was specialized care given to patients with chronic and terminal health conditions, while 34 (27%) stated the reach of Palliative Care beyond the patient to family members. Only 33 (26.4%) correctly articulated the PC package for patients with TB, while 52 (41.6%) were not aware of the care package for TB patients. Night sweats (100%) and chest pains (95%) were the most frequently reported known signs and symptoms of TB. The most frequently known TB treatment outcome was “Cured”, mentioned by 90% of respondents. Table 4

Inputs for PC program

All fourteen visited health facilities had the PC manual, PC integration client registers and TB health facility registers available for use by health workers. CBVs had a home visit register and PC enrolment register they use when offering PC services. Health workers predominantly use soft copies of current TB guidelines on their mobile phones or laptops. Fifty (40%) healthcare workers and fifty-seven (45%) community-based volunteers enrolled in the study were trained in Palliative care for TB.

Processes in the PC program

During the study period, a total of six scheduled support and supervision visits were conducted in the district by health workers and partners.

Outputs of the PC program

Among the 60 patients with TB, 41 (68%) received the treatment adherence component only of the PC package, while only 23% (14/60) received the complete package which comprised treatment adherence, physical support, and psychosocial support. Out of 60 TB patients, three (5%) received treatment adherence and psychosocial support only and two (3%) received psychosocial support only.

Outcomes for PC program

The proportion of patients who completed treatment (cured + completed treatment) was 38 out of 60 (63.3%), with unfavourable outcomes accounting for 22 out of 60 (36.7%), with deaths being the most common unfavourable outcome accounting for one in two (11/22) as shown in Table 5.

Discussion

Less than one in ten healthcare providers interviewed could define the full PC package for TB patients. The outcome of “Cured” for patients receiving Palliative Care was the most frequently mentioned by nine in ten, with other possible outcomes referenced by fewer than 50%. This is notable given that 60% of health workers and community-based volunteers received on-the-job training and workshops to enhance their skills in TB and PC. These findings are similar to findings by Bilal and Connor who reported that TB workers lacked knowledge and skills in PC [9,10].

Despite these knowledge gaps, it is important to recognize that an investment was made to train Health workers and Community-based volunteers on Palliative Care as a novel approach to improve patient outcomes. This allowed them to provide services to eligible patients’ in accordance with the Palliative Care manual in Zimbabwe [8]. During visits to health facilities, it was found that the Palliative Care manuals were available, although some health workers interviewed were not aware of their existence. Additionally, hard copies of the TB guidelines were not available at any of the 14 health facilities visited. Thirty healthcare workers had access to a soft copy of the new National TB and Leprosy Management guidelines of 2023 on their smartphones and laptops. This situation meant that those without smartphones had to rely on their colleagues to access these guidelines or rely on their interpretation of the information

Despite the implementation of PC in patients with TB, a high proportion of patients experienced unfavourable treatment outcomes, with one in three sampled participants reporting unfavourable outcomes. Being HIV positive was significantly associated with these unfavourable outcomes. This finding is corroborated by findings by Tesema et al [11] and Bhargava et al [12]. This is biologically plausible that HIV weakens the immune system, making it harder for the body to combat infection. Therefore, the full package of palliative care did not protect against unfavourable TB treatment outcomes among TB patients who were HIV-positive.

Although the full package of palliative care was being implemented in Chirumhanzu District, a history of previous TB emerged as a significant risk factor for unfavourable treatment outcomes. Previous treatment history is associated with treatment failure and the emergence of drug-resistant TB. This is consistent with study findings by Tok et al [13], who highlighted that a history of previous TB treatment was associated with unfavourable outcomes. Our results suggest that the full package of Palliative Care did not reduce the likelihood of unfavourable TB treatment outcomes among patients who had a history of previous TB treatment

Study results indicate that relapse is a risk factor for unfavourable tuberculosis (TB) treatment outcomes. This finding aligns with research by Tok et al. (2020), which also showed that TB relapse is linked to negative outcomes [13]. The difficulty in detecting symptoms associated with extrapulmonary TB may contribute to this issue, as these symptoms can be severe by the time they are identified, making it less likely to achieve favourable treatment results.

Our study suggests that receiving a full package of PC may reduce the likelihood of unfavourable TB treatment outcomes, although the results were not statistically significant. This finding is unexpected, considering that the full PC intervention was primarily designed to address adverse outcomes for patients in care. Information bias may have contributed to these results, particularly in cases where patients received the full package of the PC but it was not recorded. Additionally, treatment adherence support or “Directly Observed Treatment” (DOT) is a core component of Palliative Care that has been extensively documented in the literature as beneficial for improving TB outcomes [14,15]. It is also possible that additional elements to the Palliative Care package did not have a significant impact and may contribute to an already heavy workload for stretched healthcare workers. It would be worthwhile to investigate whether confounding factors such as disease severity and socio-economic status which were not documented in this study, could have masked the effect or introduced bias in the selection of those enrolled in Palliative Care.

The retrospective nature of this study could not control for documentation errors in the abstracted data used for this analysis. As such, certain variables such as socio-demographic factors (employment, marital status and education), existing co-morbidities other than DM and HIV, Body mass index and risk behaviour (alcohol and smoking) were not readily available for investigation. The sample size used for reviewing the register was relatively small, which could have minimized significant measures of association.

Conclusion

The study highlighted an urgent need to address the identified risk factors, including HIV, extrapulmonary TB nd a previous history of TB treatment. It also emphasised the importance of enhancing palliative care knowledge and its application among health workers and community-based volunteers to improve TB treatment outcomes. The high rate of unfavourable outcomes further underscores the necessity of implementing these interventions promptly.

Recommendations

Inclusion of a multidisciplinary team in offering palliative care services to patients with TB, rather than it being the domain of community-based volunteers and nurses in the TB clinic only. Further research however may be needed, possibly prospectively with a larger sample size, to clarify the real impact of the PC package in improving treatment outcomes.

What is already known about the topic

- Treatment adherence has been shown to improve TB treatment outcomes

- Most patients with TB received treatment adherence component of the Palliative Care package

What this study adds

- Additional elements of Palliative Care beyond treatment adherence within the PC package do not seem to make a difference in averting unfavourable outcomes

- Need to revise the implementation of the Palliative Care Program for patients with TB, to include all the necessary health professionals.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the University of Zimbabwe, the Department of Global Public Health and Family Medicine, The Union Zimbabwe Trust, the Ministry of Health and Child Care and the Zimbabwe Field Epidemiology Training Program for their steadfast support throughout the study.

Authors´ contributions

VVK, AC, MT, NG, GS, RN, SD GM, JC and TJ: contributed to the conception, data collection, data analysis, and interpretation of study findings, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. VVK, AC, MT, NG, GS, RN, SD GM, and TJ: Supervised and revised several drafts of the manuscript for intellectual content. VVK, AC, MT, NG, GS, RN, SD GM, TJ and JC: Supervision and revision of several drafts of the manuscript for intellectual content. VVK, AC, MT, NG, GS, RN, SD GM, TJ, and JC: Critical supervision and revision of several drafts of the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

| Name of District | Number of notified TB patients | Number (%) TB patients that received PC | Number (%) TB patients who died |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chirumhanzu | 148 | 146 (99%) | 16 (11%) |

| Gweru | 460 | 336 (73%) | 25 (5%) |

| Kwekwe | 873 | 734 (84%) | 64 (9%) |

| Shurugwi | 367 | 275 (75%) | 18 (5%) |

| Zvishavane | 228 | 213 (93%) | 18 (8%) |

| Total | 2076 | 1704 (82%) | 141 (8.2%) |

| Characteristic (N=125) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 34 (27.2) |

| Female | 91 (72.8) |

| Type of Respondent | |

| Registered General Nurse | 84 (67.2) |

| Primary Care Nurse | 26 (20.8) |

| Village Health Worker | 15 (12) |

| Median age in years (IQR) | 44 (Q1=40, Q3=50) |

| Median years since joining the district (IQR) | 10 (Q1=5, Q3=18) |

| Variable | Category | Unfavourable TB treatment outcomes Yes [N=22] n (%) | No [N=38] n (%) | Crude Prevalence Odds Ratio | Adjusted Prevalence Odds Ratio | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV status | Positive | 18 (53.0) | 16 (47.0) | 6.19 (1.32–8.95) | 10.52 (1.83–60.6) | 0.008 |

| Negative | 4 (15) | 22 (65.0) | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Site of TB | Extrapulmonary | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | 5.84 (0.42–314.84) | 76.8 (1.46–405) | 0.03 |

| Pulmonary | 19 (34.0) | 37 (66.0) | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Type of TB | Retreatment | 16 (48.5) | 17 (51.5) | 3.29 (1.06–10.25) | 11.4 (1.75–74.11) | 0.011 |

| New | 6 (22.2) | 21 (78.8) | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Full package of palliative care | Yes | 4 (44.4) | 5 (55.6) | 0.68 (0.16–2.86) | 0.88 (0.25–8.01) | 0.7 |

| No | 18 (35.3) | 33 (64.7) | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Question | Response (n=125) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| What is PC? | Specialized care to patients with chronic/terminal health conditions | 86 (68.8) |

| Specialized care is given to patients with chronic/terminal health conditions and their families | 34 (27.2) | |

| Direct Observed Treatment (DOT) | 3 (2.4) | |

| Do not know | 2 (1.6) | |

| What is the PC package for TB patients? | Treatment adherence, physical and psychosocial support | 33 (26.4) |

| Psychosocial support | 36 (28.8) | |

| Social support | 4 (3.2) | |

| Do not know | 52 (41.6) | |

| What are the signs and symptoms of TB? | Night sweats | 125 (100) |

| Persistent cough >2 weeks in HIV-negative | 56 (44.8) | |

| Current cough in HIV-positive | 90 (72) | |

| Unintentional weight loss | 93 (74.4) | |

| Loss of appetite | 90 (72) | |

| Fever >2 weeks | 71 (56.8) | |

| Chest pains | 119 (95.2) | |

| What are the TB treatment outcomes? | Cured | 113 (90.4) |

| Treatment completed | 60 (48.0) | |

| Lost to follow-up | 13 (10.4) | |

| Not evaluated | 11 (8.8) | |

| Treatment failed | 16 (15.2) | |

| Died | 22 (17.6) | |

| What are the benefits of PC for TB patients? | Improved quality of life | 57 (14.1) |

| Enhanced treatment adherence | 32 (25.6) | |

| Psychological symptom relief | 14 (11.2) | |

| Physical pain relief | 34 (27.2) | |

| Do not know | 35 (28) |

| Outcome variable (N=60) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| The proportion of TB patients who received PC and were cured | 6 (10.0) |

| Proportion of TB patients who received PC and completed treatment | 32 (53.3) |

| Proportion of TB patients who received PC and died | 11 (18.3) |

| Proportion of TB patients who received PC with treatment failure | 1 (1.7) |

| Proportion of TB patients who received PC and were lost to follow-up | 4 (6.7) |

| The proportion of TB patients who received PC and were not evaluated | 6 (10.0) |

| Total | 60 (100.0) |

References

- World Health Organization. WHO releases new global lists of high-burden countries for TB, HIV-associated TB and drug-resistant TB. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2021 [cited 2025 Apr 29]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/17-06-2021-who-releases-new-global-lists-of-high-burden-countries-for-tb-hiv-associated-tb-and-drug-resistant-tb

- Madybaeva D, Duishekeeva A, Meteliuk A, Kulzhabaeva A, Kadyrov A, Shumskaia N, Kumar AMV. “Together against tuberculosis”: cascade of care of patients referred by the private health care providers in the Kyrgyz Republic. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2023;8(6):316. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2414-6366/8/6/316

- World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2023. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2023 [cited 2025 Apr 29]. 57 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240083851

- Shegaze M, Boda B, Ayele G, Gebremeskel F, Tariku B, Gultie T. Why people die of active tuberculosis in the era of effective chemotherapy in Southern Ethiopia: a qualitative study. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2022;29:100338. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2405579422000432

- Cleary J, Hastie B, Harding R, Jaramillo E, Connor S, Krakauer E. Global atlas of palliative care. 2nd ed. London (England): Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance; 2020 [cited 2025 Apr 29]. Chapter 3, What are the main barriers to palliative care development; p. 33-44. Available from: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/integrated-health-services-(ihs)/csy/palliative-care/whpca_global_atlas_p5_digital_final.pdf?sfvrsn=1b54423a_3

- Krakauer EL, Dheda K, Kalsdorf B, Kuksa L, Nadkarni A, Nhung NV, Selwyn P, Shin S, Skrahina A, Jaramillo E. Palliative care and symptom relief for people affected by multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2019;23(8):881-90. Available from: https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/10.5588/ijtld.18.0428

- Govender T, Naidoo S, Padayatchi N, Gwyther L. Palliative care for drug-resistant tuberculosis: an urgent call to action. S Afr Med J. 2018;108(5):360. Available from: http://www.samj.org.za/index.php/samj/article/view/12290

- World Health Organization. Management of tuberculosis: training for health facility staff. 2nd ed. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2012 [cited 2025 Apr 29]. 17 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241598736

- Bilal M. The knowledge of palliative care and the attitude toward it among the nurses at Sabia General Hospital 2018. Sudan J Med Sci. 2018;13(4):301-10. Available from: https://knepublishing.com/index.php/SJMS/article/view/3606

- Connor SR. Palliative care for tuberculosis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(2):S178-80. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0885392417303597

- Tesema T, Seyoum D, Ejeta E, Tsegaye R. Determinants of tuberculosis treatment outcome under directly observed treatment short courses in Adama City, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0232468. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232468

- Bhargava A, Bhargava M. Tuberculosis deaths are predictable and preventable: comprehensive assessment and clinical care is the key. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2020;19:100155. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2405579420300139

- Tok PSK, Liew SM, Wong LP, Razali A, Loganathan T, Chinna K, Ismail N, Kadir NA. Determinants of unsuccessful treatment outcomes and mortality among tuberculosis patients in Malaysia: a registry-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231986. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231986

- Adane HT, Howe RC, Wassie L, Magee MJ. Diabetes mellitus is associated with an increased risk of unsuccessful treatment outcomes among drug-susceptible tuberculosis patients in Ethiopia: a prospective health facility-based study. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2023;31:100368. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2405579423000244

- Otu AA. Is the directly observed therapy short course (DOTS) an effective strategy for tuberculosis control in a developing country? Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2013;3(3):227-31. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2222180813600456

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Tables

| Name of District | Number of notified TB patients | Number (%) TB patients that received PC | Number (%) TB patients who died |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chirumhanzu | 148 | 146 (99%) | 16 (11%) |

| Gweru | 460 | 336 (73%) | 25 (5%) |

| Kwekwe | 873 | 734 (84%) | 64 (9%) |

| Shurugwi | 367 | 275 (75%) | 18 (5%) |

| Zvishavane | 228 | 213 (93%) | 18 (8%) |

| Total | 2076 | 1704 (82%) | 141 (8.2%) |

Table 1: Palliative care enrolment and deaths among TB patients eligible for palliative care in Kunda-Nqob’iTB supported districts of Midlands Province – April 2021 – September 2023 (Source: DHIS2)

| Characteristic (N=125) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 34 (27.2) |

| Female | 91 (72.8) |

| Type of Respondent | |

| Registered General Nurse | 84 (67.2) |

| Primary Care Nurse | 26 (20.8) |

| Village Health Worker | 15 (12) |

| Median age in years (IQR) | 44 (Q1=40, Q3=50) |

| Median years since joining the district (IQR) | 10 (Q1=5, Q3=18) |

Table 2: Demographic characteristics of study participants in Chirumhanzu District, Zimbabwe, 2023

| Variable | Category | Unfavourable TB treatment outcomes Yes [N=22] n (%) | No [N=38] n (%) | Crude Prevalence Odds Ratio | Adjusted Prevalence Odds Ratio | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV status | Positive | 18 (53.0) | 16 (47.0) | 6.19 (1.32–8.95) | 10.52 (1.83–60.6) | 0.008 |

| Negative | 4 (15) | 22 (65.0) | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Site of TB | Extrapulmonary | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | 5.84 (0.42–314.84) | 76.8 (1.46–405) | 0.03 |

| Pulmonary | 19 (34.0) | 37 (66.0) | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Type of TB | Retreatment | 16 (48.5) | 17 (51.5) | 3.29 (1.06–10.25) | 11.4 (1.75–74.11) | 0.011 |

| New | 6 (22.2) | 21 (78.8) | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Full package of palliative care | Yes | 4 (44.4) | 5 (55.6) | 0.68 (0.16–2.86) | 0.88 (0.25–8.01) | 0.7 |

| No | 18 (35.3) | 33 (64.7) | Reference | Reference | Reference |

Table 3: Factors associated with unfavourable outcomes for TB patients who received Palliative Care in Chirumhanzu District, Zimbabwe, 2021–2023

| Question | Response (n=125) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| What is PC? | Specialized care to patients with chronic/terminal health conditions | 86 (68.8) |

| Specialized care is given to patients with chronic/terminal health conditions and their families | 34 (27.2) | |

| Direct Observed Treatment (DOT) | 3 (2.4) | |

| Do not know | 2 (1.6) | |

| What is the PC package for TB patients? | Treatment adherence, physical and psychosocial support | 33 (26.4) |

| Psychosocial support | 36 (28.8) | |

| Social support | 4 (3.2) | |

| Do not know | 52 (41.6) | |

| What are the signs and symptoms of TB? | Night sweats | 125 (100) |

| Persistent cough >2 weeks in HIV-negative | 56 (44.8) | |

| Current cough in HIV-positive | 90 (72) | |

| Unintentional weight loss | 93 (74.4) | |

| Loss of appetite | 90 (72) | |

| Fever >2 weeks | 71 (56.8) | |

| Chest pains | 119 (95.2) | |

| What are the TB treatment outcomes? | Cured | 113 (90.4) |

| Treatment completed | 60 (48.0) | |

| Lost to follow-up | 13 (10.4) | |

| Not evaluated | 11 (8.8) | |

| Treatment failed | 16 (15.2) | |

| Died | 22 (17.6) | |

| What are the benefits of PC for TB patients? | Improved quality of life | 57 (14.1) |

| Enhanced treatment adherence | 32 (25.6) | |

| Psychological symptom relief | 14 (11.2) | |

| Physical pain relief | 34 (27.2) | |

| Do not know | 35 (28) |

Table 4: Knowledge of PC among health workers and community-based volunteers in Chirumhanzu District, Zimbabwe, 2023

| Outcome variable (N=60) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| The proportion of TB patients who received PC and were cured | 6 (10.0) |

| Proportion of TB patients who received PC and completed treatment | 32 (53.3) |

| Proportion of TB patients who received PC and died | 11 (18.3) |

| Proportion of TB patients who received PC with treatment failure | 1 (1.7) |

| Proportion of TB patients who received PC and were lost to follow-up | 4 (6.7) |

| The proportion of TB patients who received PC and were not evaluated | 6 (10.0) |

| Total | 60 (100.0) |

Table 5: Outcomes for patients who received Palliative Care in Chirumhanzu District, Zimbabwe, 2021-2023

Figures

Keywords

- Kunda-Nqob’I TB,

- Palliative Care

- Tuberculosis

- Unfavourable outcomes

- Zimbabwe