Research | Open Access | Volume 8 (4): Article 86 | Published: 24 Oct 2025

Factors influencing low coverage of optimal dose of intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine among pregnant women in Farafangana, Madagascar, 2024

Menu, Tables and Figures

Navigate this article

Tables

| Characteristics | Effective (n = 901) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 15 – 19 | 218 | 24.2 |

| 20 – 24 | 310 | 34.4 |

| 25 – 29 | 165 | 18.3 |

| 30 – 34 | 114 | 12.7 |

| 35 – 39 | 65 | 7.2 |

| ≥ 40 | 29 | 3.2 |

| Distance from home to health center (in km) | ||

| ≤ 5 | 835 | 92.7 |

| 6 – 15 | 66 | 7.3 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 180 | 20.0 |

| Married | 615 | 68.3 |

| Divorced | 88 | 9.8 |

| Widowed | 18 | 2.0 |

| Education level | ||

| No formal education | 217 | 24.1 |

| Primary | 384 | 42.6 |

| Secondary | 265 | 29.4 |

| University | 35 | 3.9 |

Table 1: Distribution of surveyed mothers in the urban commune of Farafangana by socio-demographic characteristics, 2024

| Characteristics | Frequency (n = 901) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gravidity | ||

| Primigravida | 256 | 28.4 |

| Paucigravida | 426 | 47.3 |

| Multigravida | 161 | 17.9 |

| Grand multigravida | 58 | 6.4 |

| Parity | ||

| Primiparous | 274 | 30.4 |

| Pauciparous | 418 | 46.4 |

| Multiparous | 157 | 17.4 |

| Grand multiparous | 52 | 5.8 |

| Antenatal care visit | ||

| Yes | 831 | 92.2 |

| No | 70 | 7.8 |

| Number of ANC visits (n = 831) | ||

| < 4 | 134 | 16.1 |

| ≥ 4 | 697 | 83.9 |

| Gestational age at the first ANC visit (in months) (n = 831) | ||

| ≤ 4 | 669 | 80.5 |

| From the 5th month onward | 162 | 19.5 |

Table 2: Distribution of surveyed mothers in the urban commune of Farafangana by clinical characteristics, 2024

| Variables | IPTp-SP3 – n (%) | IPTp-SP3 + n (%) | Crude OR [95% CI] | Adjusted OR [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | ||||

| < 25 | 243 (60.0) | 162 (40.0) | 0.79 [0.58 – 1.08] | 0.47* [0.26 – 0.83] |

| ≥ 25 | 186 (65.5) | 98 (34.5) | 1 | |

| Gravidity | ||||

| Primigravida | 108 (54.5) | 90 (45.5) | 1 | |

| Paucigravida | 209 (64.5) | 115 (35.5) | 1.51* [1.06 – 2.17] | 1.38 [0.94 – 2.04] |

| Multigravida | 84 (68.9) | 38 (31.1) | 1.84* [1.14 – 2.96] | 1.66* [1.08 – 3.14] |

| Parity | ||||

| Primiparous | 112 (54.1) | 95 (45.9) | 1 | |

| Pauciparous | 207 (64.1) | 116 (35.9) | 1.51* [1.06 – 2.15] | 1.27 [0.82 – 1.95] |

| Multiparous | 85 (70.8) | 35 (29.2) | 2.06** [1.28 – 3.33] | 1.62* [1.13 – 3.18] |

| Knowledge of the recommended dose of SP | ||||

| No | 310 (87.6) | 44 (12.4) | 21.38*** [13.88 – 32.91] | 6.82** [3.21 – 14.49] |

| Yes | 59 (24.8) | 179 (75.2) | 1 | |

| Start of SP intake | ||||

| ≥ 5th month | 193 (68.4) | 89 (31.6) | 1.57** [1.14 – 2.16] | 2.28** [1.41 – 3.67] |

| 4th month | 236 (58.0) | 171 (42.0) | 1 | |

| Side effects during SP intake | ||||

| Yes | 233 (66.6) | 117 (33.4) | 1.45* [1.07 – 1.98] | 1.58* [1.02 – 2.46] |

| No | 196 (57.8) | 143 (42.2) | 1 | |

* = p < 0.05; ** = p < 0.01; *** = p < 0.001

OR = Odds Ratio

AOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio

IPTp-SP3− : Less than three doses of intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine during pregnancy

Table 3: Bivariate and multivariate analysis – Predictive variables of IPTp-SP3 among women in the urban commune of Farafangana, 2024

Figures

Keywords

- Coverage

- Factors

- Madagascar

- Pregnancy

- Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine

Botovola Miraimila1,2,&, Félix Alain2, Patrick Rakotondralambo3, Fanta Sogoré1,4, Youssouf Bagayan1,5, Arsène Ratsimbasoa6, Kassoum Kayentao1,4

1Department of Public Health and Specialties, Faculty of Medicine and Odonto-Stomatology, University of Sciences, Techniques, and Technologies of Bamako, Mali, 2Faculty of Medicine, University of Antananarivo, Madagascar, 3District and Public Health Service of Andramasina, Madagascar, 4Malaria Research and Training Centre (MRTC), Mali, 5Clinical Research Unit of Nanoro, Institut de Recherche en Sciences de la Santé, Nanoro, Burkina Faso, 6Faculty of Medicine, University of Fianarantsoa, Madagascar

&Corresponding author: Botovola Miraimila, Department of Public Health and Specialities, Faculty of Medicine and Odonto-Stomatology, University of Sciences, Techniques, and Technologies of Bamako, Mali, Email: miraymila90@gmail.com, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0002-0999-5019

Received: 29 Mar 2025, Accepted: 23 Oct 2025, Published: 24 Oct 2025

Domain: Malaria in Pregnancy

Keywords: Coverage, Factors, Madagascar, Pregnancy, Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine

©Botovola Miraimila et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Botovola Miraimila et al., Factors influencing low coverage of optimal dose of intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine among pregnant women in Farafangana, Madagascar, 2024. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8(4):86. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00082

Abstract

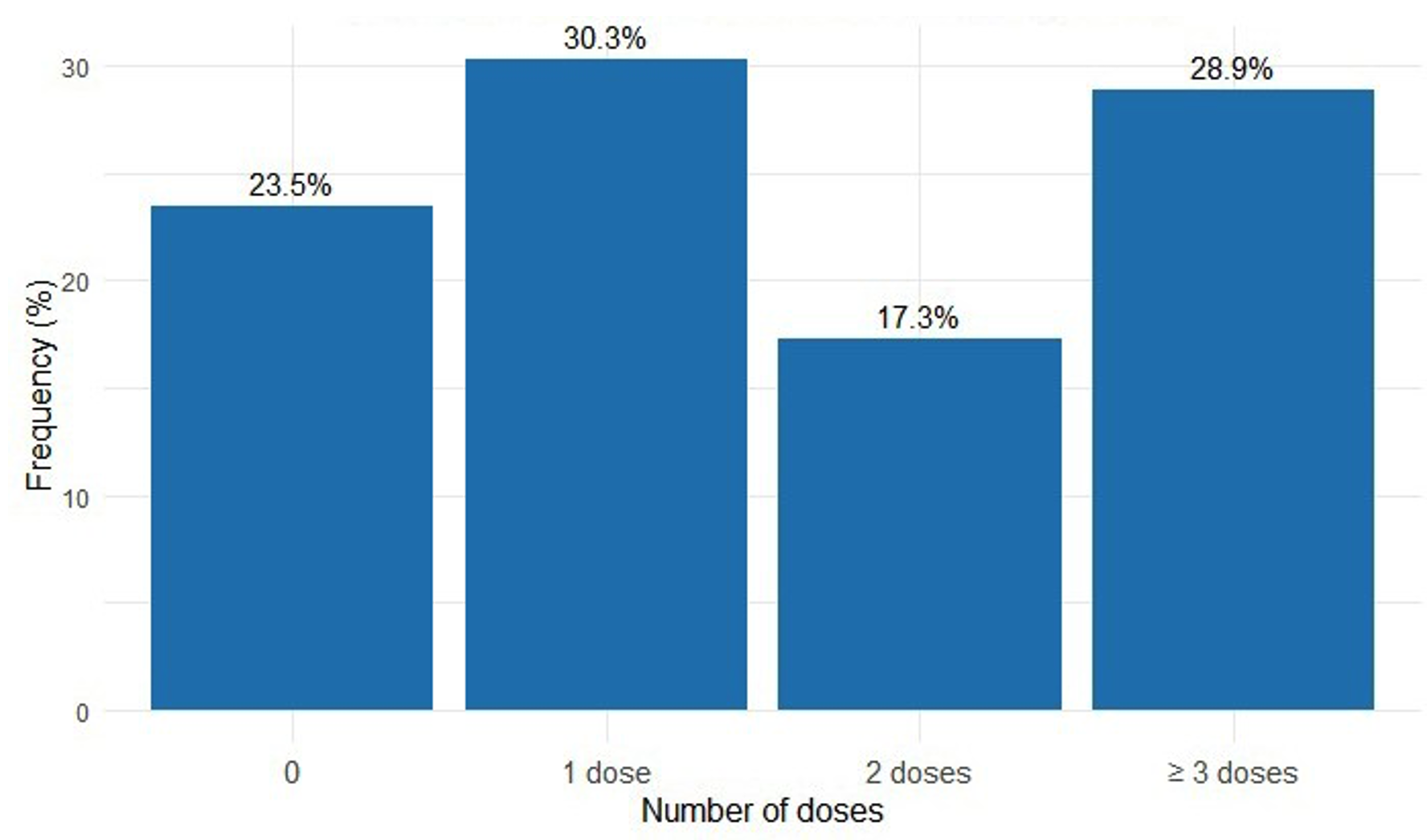

Introduction: In Madagascar, coverage of the optimal dose (three doses or more) of Intermittent Preventive Treatment with Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine during pregnancy (IPTp-SP) remains low, reaching only 31% in 2021. This study aimed to investigate the factors influencing this low coverage in a particularly affected community.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional study using a mixed-methods approach, conducted among mothers with a child under 12 months and healthcare personnel in Farafangana from November 19, 2024, to January 10, 2025. A descriptive analysis, a bivariate and multivariate logistic regression, were conducted. The odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval was used as the measure of association. Qualitative data analysis was conducted manually based on predefined themes and sub-themes.

Results: The coverage of the optimal dose of IPTp-SP was 28.9%. Factors significantly associated with the non-receipt of the optimal dose included women under 25 years of age (adjusted odds ratios (AOR) [95% confidence intervals (CI)] = 0.47 [0.26 – 0.83]), being multigravida (AOR [95% CI] = 1.66 [1.08 – 3.14]), multiparity (AOR [95% CI] = 1.62 [1.13 – 3.18]), poor knowledge of the recommended dose (AOR [95% CI] = 6.82 [3.21 – 14.49]), late initiation of intake (AOR [95% CI] = 2.28 [1.41 – 3.67]), and SP-related side effects (AOR [95% CI] = 1.58 [1.02 – 2.46]). The qualitative approach corroborated these findings and identified the influence of women’s social surroundings.

Conclusion: Factors related to women, sociocultural aspects, and the health system influence the low coverage of the optimal IPTp-SP dose in Farafangana. An implementation approach addressing all these factors would be essential to improve coverage.

Introduction

Malaria is the most common and concerning parasitic disease among pregnant women [1]. It plays a significant role in various complications such as stillbirth, prematurity, intrauterine growth retardation, low birth weight, and an increased risk of maternal anaemia [2, 3]. More than 30 million pregnant African women living in malaria endemic regions are at risk of infection each year [1]. Malaria is responsible for approximately 10,000 maternal deaths and 100,000 newborn deaths worldwide annually, with nearly half of these deaths occurring in sub-Saharan Africa [4].

In light of these severe consequences, one of the measures recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) for all pregnant women living in malaria endemic regions to prevent malaria is taking at least three doses of intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP) [4]. The administration of SP begins in the second trimester of pregnancy, with doses spaced at least one month apart during each antenatal care (ANC) visit [5]. Several studies have demonstrated that taking the optimal dose of IPTp-SP (at least three doses of SP) effectively reduces the risk of placental infection, maternal anaemia, and low birth weight [6-8].

Despite its proven effectiveness, the coverage of the optimal dose of IPTp-SP remains low in most sub-Saharan African countries, falling well below the WHO target of at least 80% coverage [1]. In 2023, among the 36 African countries that reported data on IPTp-SP coverage, 43% of eligible pregnant women received at least three doses of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP), compared to 42% in 2022 and 35% in 2021 [1]. In some sub-Saharan African countries, IPTp-SP uptake has been influenced by women’s education level, occupation, marital status, parity, and exposure to IPTp-SP-related messages[9-11].

In Madagascar, SP is administered as Directly Observed Treatment (DOT), provided free of charge during ANC visits at health centres by healthcare professionals (nurses, midwives, or doctors) [12]. The goal is to ensure that at least 80% of pregnant women receive at least three doses of IPTp-SP in the 93 districts under control phase [13]. However, national coverage of three or more doses of IPTp-SP in Madagascar remains low, 14.9% in 2018 [14], and 31% in 2021 [15]. A secondary analysis of the 2016 Malaria Indicator Survey data identified education level and exposure to malaria messages on radio and television as key determinants of IPTp-SP uptake [10]. While these factors are important, they do not fully explain the persistently low coverage, suggesting that other individual, sociocultural, and health system barriers may also play a significant role.

Few studies have examined the factors influencing the low IPTp-SP coverage in Madagascar [12,13,16] and those that exist have mainly relied on either purely quantitative or purely qualitative approaches. While quantitative studies can identify statistical associations, they often fail to capture the underlying contextual or behavioural factors. Conversely, qualitative studies provide rich insights but may lack generalizability. Conducting a mixed-methods study would provide a deeper understanding of the factors affecting this low coverage[17]. This approach would also help to explain what is slowing down the use of IPTp-SP, find ways to remove these obstacles, and suggest practical solutions that are supported by research..

The urban commune of Farafangana is among the areas with the lowest coverage of at least three doses of IPTp-SP, with coverage rates of 5.7% in 2018 [14] and 23% in 2021 [15]. As a hypothesis, factors related to women, the health system, and sociocultural factors may influence the low coverage of the optimal dose of IPTp-SP in the urban commune of Farafangana. This study aimed to identify the factors influencing the low coverage of the optimal IPTp-SP dose in the urban commune of Farafangana and to describe the reasons why pregnant women did not receive the optimal dose of IPTp-SP.

Methods

Study site

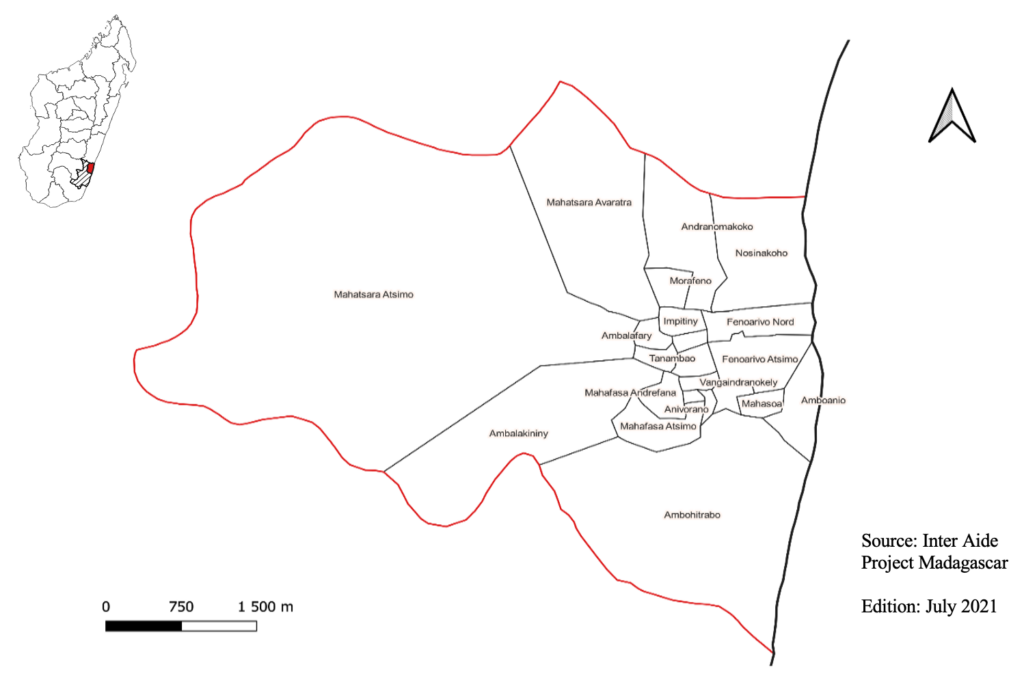

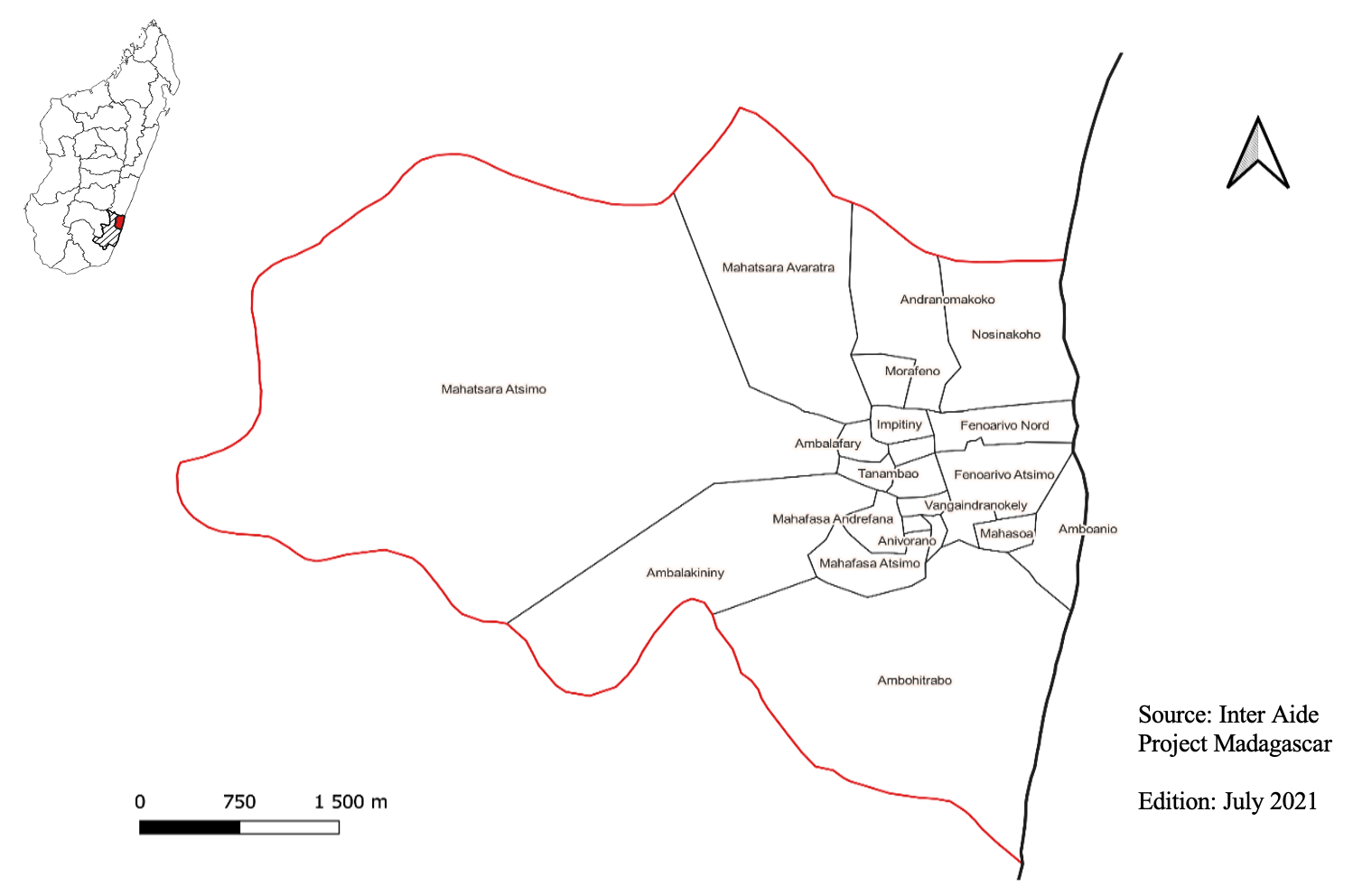

The study was conducted in the urban municipality of Farafangana, in southeastern Madagascar, an area with a high malaria incidence and low IPTp-SP3 coverage, estimated at 23% in 2021 [15]. Situated at the mouth of the Manampatrana River, south of the Pangalanes Canal, Farafangana has a tropical climate with alternating wet and dry seasons and moderate temperatures year-round [18]. This largely forested area spans 1,825 km² and had an estimated population of 42,824 in 2024 [19]. The population is mainly composed of the Antefasy, Zafisoro, and Rabakara ethnic groups [18]. Malaria is endemic, with Plasmodium falciparum as the dominant species, though P. vivax, P. malariae, and P. ovale are also present. Pregnant women receive SP during ANC visits at the Level II Basic Health Centre and two private clinics. According to national guidelines, IPTp-SP is provided from the second trimester, with at least three doses recommended at one-month intervals during ANC [14,15,20] (Figure 1).

Study type, population, and period

This was a cross-sectional study using a concurrent mixed-methods approach, conducted from November 19, 2024, to January 10, 2025. The quantitative approach was an analytical cross-sectional study that simultaneously collected information on the optimal dose of IPTp-SP and its influencing factors through a survey of mothers with a child under 12 months old. The qualitative approach involved individual interviews with healthcare personnel involved in ANC and IPTp-SP, as well as focus group discussions with mothers of children under 12 months old.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

For the quantitative component, the study included women who had given birth within the past 12 months and had lived in the urban municipality of Farafangana for at least 18 months. Minors under 18 were eligible, with informed assent and parental or guardian consent obtained per ethical guidelines. Mothers who reported attending ANC visits were asked to present their maternal health booklet to verify the number and timing of IPTp-SP doses. When unavailable due to loss or misplacement, data were collected based on verbal reports.

For the qualitative component, individual interviews were conducted with healthcare workers having at least five years of experience in ANC and IPTp-SP delivery. Focus group discussions were also held with women who had given birth in the previous 12 months. Women unable to respond due to mental, hearing, or speech impairments were excluded. The qualitative component also excluded interim, on-leave, or non-participating healthcare personnel.

Sampling method

For the quantitative approach, a two-stage sampling method was used. First, 12 of the 24 neighbourhoods (fokontany) in Farafangana were randomly selected using Excel’s “RANDBETWEEN” function. To avoid geographical clustering, selections were checked for spatial balance, and the draw was repeated if needed to ensure representativeness.

In the second stage, using sampling proportionate to size, the estimated total sample of required households was proportionally distributed across the 12 selected neighbourhoods according to the number of households in each, to ensure balanced representation. Households within selected neighbourhoods were chosen through systematic random sampling. The sampling interval was obtained by dividing the total number of households by the required sample size. The starting point was randomly selected, followed by households at fixed intervals.

To determine the survey direction, the “Bic pen spinning method” was used: from a central landmark (school, health centre, market), a pen was tossed, and the survey began in the direction indicated by the tip. In each household, one eligible woman (who had given birth in the past 12 months and met eligibility criteria) was randomly selected for interview.

For the qualitative approach, non-probability purposive sampling was used to select healthcare personnel based on their involvement and participation in ANC and IPTp-SP, as well as their tenure in their current positions. The same non-probability sampling method was used to select participants for focus group discussions, targeting women who had given birth in the last 12 months.

Sample size

For the quantitative approach, the sample size was calculated using Stacalc in Epi-Info 7.2.5.0. The two-sided confidence level was set at 95% with a study power of 80%. The ratio of unexposed to exposed was one. The proportion in the unexposed group was 62.5%, corresponding to women who had heard about IPTp-SP (unexposed group) but had received fewer than three doses of SP in a study conducted in 2018 in the Chókwè district of southern Mozambique [21]. The odds ratio was 1.6. After calculation, the minimum sample size obtained was 694. This was increased by 10% to account for potential deficiencies or incomplete data, resulting in an estimated sample size of 694 + (694*0.10) = 763 [22, 23]. The total sample of 763 households was proportionally distributed across the 12 selected neighbourhoods according to the number of households in each, to ensure balanced representation.

For the qualitative approach, we conducted six individual interviews with healthcare workers and six focus group discussions (FGDs) with pregnant women, guided by data saturation. We continued collecting data until no new themes emerged. The focus groups were divided into two main categories based on whether the women received the recommended optimal doses of IPTp-SP. Participants were selected purposively. Each category consisted of three groups of 6-8 women, organized by their parity: primiparous, pauciparous, and multiparous. This structure was maintained for both women who received the optimal doses and those who did not.

Variables and discussion themes

The dependent variable was defined as having received the optimal dose of IPTp-SP or not (optimal IPTp-SP dose: yes or no). Independent variables included: age, distance from home to health centre, marital status, education level, gravidity, parity, antenatal care visit, number of ANC visits, gestational age at the first ANC visit, knowledge of the recommended dose of SP, start of SP intake and side effects during SP intake. For the qualitative approach, discussion themes addressed three factors: individual factors, sociocultural factors, and health system-related factors.

Data collection techniques and tools

For the quantitative approach, four investigators conducted face-to-face individual interviews with each participant. Each interview lasted approximately 10 minutes. The investigators visited households accompanied by a local guide to facilitate access and community acceptance. ANC booklets were requested from those who had attended ANC. All data were collected using an electronic questionnaire deployed through the KoBoCollect application, version 2024.2.4 on Android tablets (KoBoToolbox, 2024). This tool allowed for real-time data entry, consistency checks, and secure storage, improving data quality and minimizing entry errors.

For the qualitative approach, individual and group interviews were conducted using semi-structured interview guides. Six to eight women participated in each FGD, grouped by parity and IPTp-SP uptake, using a semi-structured guide with lead and probe questions. Each session lasted about 45 minutes, was conducted in Malagasy, moderated by a facilitator, and supported by a note taker, with discussions audio-recorded for transcription and analysis.

Individual interviews with healthcare personnel with at least five years’ experience were conducted using a semi-structured guide, lasting 30 minutes, in Malagasy, audio-recorded, and supplemented with notes to capture contextual details.

Data processing and analysis

In the quantitative approach, data was analysed using R software, version 4.4.1 (R Core Team, 2023). Pearson’s chi-square test compared proportions, while Fisher’s exact test was used for expected cell counts <5. The significance threshold was set at p<0.05. Logistic regression estimated crude and adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) to assess associations. Variables with p<0.20 in bivariate analysis were retained for multivariate modelling. Model quality was evaluated with the Hosmer-Lemeshow test, and discrimination was assessed using the ROC curve (AUC). Multicollinearity was checked with the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), excluding or transforming variables with a VIF >5. Missing data were addressed via complete-case analysis, excluding observations with missing values on multivariate model variables. The proportion and pattern of missing data were assessed to ensure they were missing at random (MAR).

For the qualitative approach, interviews were transcribed verbatim, translated into French, and manually analysed using a thematic coding plan. All data, including outliers, were examined and interpreted. Results were presented through verbatim excerpts and synthesized summaries. Data triangulation was conducted as part of the mixed-methods design.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval from the Ethics Committee for Biomedical Research of Madagascar (CERBM, approval number: IORG00001212) and authorization from local authorities were obtained prior to data collection.. Informed consent was secured from all participants, and their data were treated confidentially and anonymously, accessible only to the research team.

Results

Quantitative approach

Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants

A total of 901 mothers with a child under 12 months of age were interviewed. Their mean age was 24.7 years (SD=6.73), ranging from 15 to 49 years. The majority (92.7%[90,8%-94,2%]) lived within ≤5 km of a health centre, and more than half (68.3%[65,2%-71,2%]) were married. Participants with a primary level of education were the most represented group (42.6%[39,4%-45,9%]), while 24.1%[21,4%-27%] had never attended school (Table 1).

ANC coverage rate

The paucigravida group was the most represented, accounting for 47.3%[44%-50,6%] of participants, followed by primigravida women at 28.4%[25,6%-31,4%]. Among the participants, 92.2%[90,3%-93,8%] attended ANC visits at health centres. The proportion of women who completed four or more ANC visits was 83.9%[ 81,2%-86,2%]. Additionally, the majority (80.5%[77,7%-83,1%]) initiated their ANC visits before the fifth month of pregnancy (Table 2).

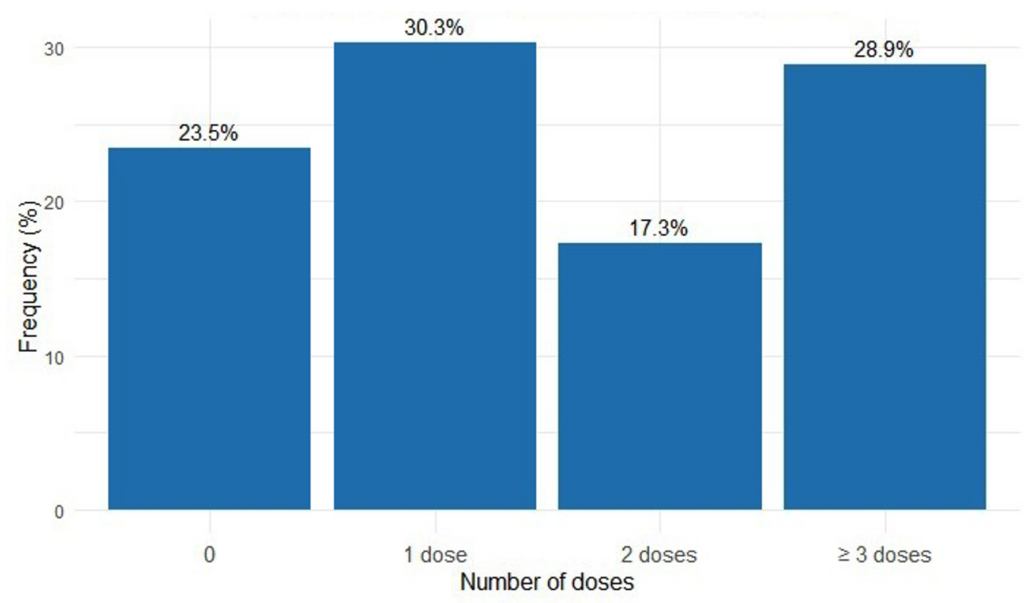

Coverage rate of the optimal dose of IPTp-SP

Among the interviewed women, 76.5%[73,6%-79,1%] (n=689) received at least one dose of SP during their last pregnancy, and 28.9% [26.0–31.9%] (n=260) received the optimal dose (Figure 2). Among them, 59.1%[55,4%-62,7%] (n=407) began taking SP from the fourth month of pregnancy. The majority (n=620), or 90%[87,5%-92%], reported not taking SP under the direct supervision of a healthcare provider.

Bivariate and multivariate analysis

Table 3 presents the results of bivariate and multivariate analyses. In the multivariate analysis, the factors significantly associated with receiving fewer than three doses of IPTp-SP (IPTp-SP3 -) were as follows: Women under 25 years old (AOR [95% CI] = 0.47[0.26–0.83]), being multigravida (AOR [95% CI] = 1.66[1.08–3.14]), multiparity (AOR [95% CI] = 1.62[1.13–3.18]), poor knowledge of the recommended dose (AOR [95% CI] = 6.82 [3.21–14.49]), late initiation of SP intake (AOR [95% CI] = 2.28[1.41–3.67]) and side effects during SP taking (AOR [95% CI] = 1.58[1.02–2.46]). These results show that women aged 25 years and above, multigravida, and multiparous women are at increased risk of not receiving the optimal dose. In addition, poor knowledge of the recommended dose, late initiation of SP intake, and side effects related to SP administration are also significant contributing factors to this situation.

Qualitative approach

Six individual interviews were conducted with ANC and IPTp-SP healthcare professionals in Farafangana, each with at least five years of experience. Additionally, six FGDs were held: three with women who had not received the optimal IPTp-SP dose and three with those who had. Each group included 6 to 8 women aged 17 to 44.

Factors related to women

All women who received the optimal IPTp-SP dose knew it was recommended to start SP at the fourth month of pregnancy and take at least three doses. In contrast, half of the women who did not receive the optimal dose (11 participants) were unaware of both the start time and the required number of doses.

Late ANC initiation and incomplete consultations were major barriers to receiving the optimal dose. Women cited heavy daily responsibilities, such as household chores and street vending, limiting their ability to attend ANC from the fourth month. Long waiting times at ANC visits also deterred attendance.

Home births with traditional birth attendants and poor service quality, especially when consultations were conducted by trainee paramedics, further discouraged formal healthcare use.

Sociocultural factors

No taboos or cultural prohibitions against SP use during pregnancy were reported. However, family influence—particularly from mothers, mothers-in-law, and close relatives—often discouraged adherence, citing beliefs that SP was too strong and could cause dizziness, vomiting, or make the baby drowsy:

“My mother advised me to take only one pill per day to avoid any potential harm to my health and my child’s.” (FGD, primiparous woman who did not receive the optimal IPTp-SP dose)

Health system-related factors

“ANC keeps us from our daily tasks. We spend the whole morning at the centre. I leave at 7:30 AM and return around 12:30 PM.” (FGD, multiparous woman who did not receive the optimal IPTp-SP dose)

Among women who did not complete the IPTp-SP schedule, side effects were a major barrier:

“The medication felt too strong. I had nausea, vomiting, and weakness. I stopped taking it.” (FGD, primiparous woman who did not receive the optimal dose)

In contrast, women who received the optimal dose managed the side effects with strategies like taking SP after a full meal and with sugary water:

“The side effects didn’t stop me. The midwife advised us to eat first and drink sugary water. It helped.” (FGD, primiparous woman who received the optimal dose)

Midwives confirmed that side effects—fatigue, nausea, and epigastric pain—are common, especially after the first dose, and lead some women to discontinue treatment.

Discussion

Age group

This study found that women under 25 were 53% less likely to miss the optimal IPTp-SP dose compared to those aged 25 years and above. This may be because younger women—often primigravidae—are more attentive to prenatal care and medical advice, while older, multiparous women may underestimate malaria risks during pregnancy [24].

These findings align with Diarra et al. (2019, Mali) [24], Masoi et al. (2022, Tanzania) [25], and Anchang-Kimbi et al. (2020, Cameroon) [26], who also reported a significant association between maternal age and IPTp-SP uptake. However, Arnaldo et al. (2018) in Mozambique found no such link, possibly due to contextual differences [21].

Gravidity and parity

This study found that multigravid and multiparous women were more likely not to receive the optimal IPTp-SP dose compared to primigravidae and primiparous women. FGDs revealed that multiparous women viewed ANC as a burden, with household duties and childcare limiting their ability to attend, reducing IPTp-SP uptake. These findings are consistent with Amankwah et al. (2019) in Ghana and Mwandagalirwa et al. (2017) in the DRC, who also reported lower IPTp-SP uptake among women with higher gravidity [27,28]. However, Masoi et al. (2022) in Tanzania found contrasting results, with multiparity associated with higher IPTp-SP uptake compared to primiparity [25].

Knowledge of the recommended SP dose

Lack of knowledge about the recommended number of SP doses was strongly associated with non-receipt of the optimal IPTp-SP dose. These findings align with previous studies by Sangho et al. in Mali (2021) [29], Amoako et al. in Ghana (2021) [30], and Mutanyi et al. in Kenya (2021) [31]. Anchang-Kimbi et al. (2020) in Mount Cameroon also identified limited knowledge on timing and dosage as a barrier to IPTp-SP uptake [26]. Focus group discussions revealed that half of the women who did not receive the optimal dose were unaware of the correct timing and dosage, emphasizing the need to improve IPTp-SP awareness.

Timing of SP initiation

Women who started SP in the fifth month were more likely not to receive the optimal dose than those who began in the fourth month. This delay likely reflects late ANC initiation. Focus groups highlighted that household and income-generating responsibilities limited women’s ability to attend ANC visits from the fourth month. Similarly, Owusu-Boateng et al. (2017) in Ghana found that early SP initiation significantly improves completion of the recommended doses [32].

Side effects of SP

In this study, women who experienced SP side effects were more likely not to receive the optimal dose. During focus group discussions, women who missed the optimal dose cited side effects as a key deterrent, while those who completed the regimen were not discouraged by them. Similarly, Eboumbou Moukoko et al. in Douala, Cameroon, reported that adverse effects and poor counselling contributed to low IPTp-SP coverage, especially among women who did not complete the recommended doses [8]. In contrast, Amankwah et al. (2019) in Ghana found no significant link between side effects and incomplete IPTp-SP uptake [27].

These findings suggest the need for targeted health education stressing early ANC attendance and correct IPTp-SP timing and dosage, particularly for older and multigravida women. Strengthening community-based counselling and follow-up may help address misconceptions and fears. Additionally, improving ANC access through flexible hours or mobile clinics could ease time and logistic constraints for busy women.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The strength of this study lies in its mixed-methods design, using qualitative data to clarify and support quantitative findings through triangulation. However, the study has several limitations. Household economic status was not assessed. The cross-sectional design and self-reported data may have introduced information bias. Recall bias is also possible, as some participants gave birth up to 12 months prior to data collection. Additionally, in the absence of maternal health booklets, ANC information had to be obtained through verbal reports, which may have affected data accuracy.

Conclusion

Optimal IPTp-SP dose coverage in Farafangana remains below WHO targets. Quantitative and qualitative analyses identified key influencing factors: maternal age, multigravidity, multiparity, limited knowledge, late initiation of SP intake, side effects, and social influences. Improving coverage requires an implementation approach addressing these factors. It is essential to strengthen sensitization of pregnant women and train healthcare workers on treatment safety and side effect management. Additional studies in rural communes are needed to identify local specificities and adapt strategies across the district.

What is already known about the topic

- The coverage of the optimal dose of intermittent preventive treatment with Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP) in Madagascar remains low, falling below the WHO target of 80%;

- This treatment is given as Directly Observed Therapy (DOT);

- It is provided free of charge during antenatal care visits at health centres by healthcare professionals, including nurses, midwives, and doctors.

What this study adds

- The quantitative approach identified various factors contributing to the low coverage of the optimal dose of intermittent preventive treatment with Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine in the urban commune of Farafangana;

- These factors include women’s age, multigravida status, multiparity, lack of knowledge about the recommended dose, late initiation of treatment, and side effects associated with SP;

- The qualitative approach supported these findings and also highlighted the influence of women’s social environment on the low coverage rates.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the teachers of the Department of Public Health and Specialities – Faculty of Medicine and Odonto-Stomatology – University of Sciences, Techniques, and Technologies of Bamako – Mali, the staff of the Public Health District Service of Farafangana, and the staff of the Regional Health Directorate of the South-East region of Madagascar

Authors´ contributions

Protocol development: Botovola Miraimila, Fanta Sogore, Youssouf Bagayan; Protocol revision: Arsène Ratsimbasoa and Kassoum Kayentao; Data collection: Botovola Miraimila, Félix Alain, Patrick Rakotondralambo; Data analysis: Botovola Miraimila, Félix Alain, Patrick Rakotondralambo; Manuscript writing: Botovola Miraimila, Arsène Ratsimbasoa, and Kassoum Kayentao; Supervision of data collection and manuscript review: Arsène Ratsimbasoa and Kassoum Kayentao. All authors contributed to conducting this study. All authors also declare that they have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

| Characteristics | Effective (n = 901) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 15 – 19 | 218 | 24.2 |

| 20 – 24 | 310 | 34.4 |

| 25 – 29 | 165 | 18.3 |

| 30 – 34 | 114 | 12.7 |

| 35 – 39 | 65 | 7.2 |

| ≥ 40 | 29 | 3.2 |

| Distance from home to health center (in km) | ||

| ≤ 5 | 835 | 92.7 |

| 6 – 15 | 66 | 7.3 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 180 | 20.0 |

| Married | 615 | 68.3 |

| Divorced | 88 | 9.8 |

| Widowed | 18 | 2.0 |

| Education level | ||

| No formal education | 217 | 24.1 |

| Primary | 384 | 42.6 |

| Secondary | 265 | 29.4 |

| University | 35 | 3.9 |

| Characteristics | Frequency (n = 901) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gravidity | ||

| Primigravida | 256 | 28.4 |

| Paucigravida | 426 | 47.3 |

| Multigravida | 161 | 17.9 |

| Grand multigravida | 58 | 6.4 |

| Parity | ||

| Primiparous | 274 | 30.4 |

| Pauciparous | 418 | 46.4 |

| Multiparous | 157 | 17.4 |

| Grand multiparous | 52 | 5.8 |

| Antenatal care visit | ||

| Yes | 831 | 92.2 |

| No | 70 | 7.8 |

| Number of ANC visits (n = 831) | ||

| < 4 | 134 | 16.1 |

| ≥ 4 | 697 | 83.9 |

| Gestational age at the first ANC visit (in months) (n = 831) | ||

| ≤ 4 | 669 | 80.5 |

| From the 5th month onward | 162 | 19.5 |

| Variables | IPTp-SP3 – n (%) | IPTp-SP3 + n (%) | Crude OR [95% CI] | Adjusted OR [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | ||||

| < 25 | 243 (60.0) | 162 (40.0) | 0.79 [0.58 – 1.08] | 0.47* [0.26 – 0.83] |

| ≥ 25 | 186 (65.5) | 98 (34.5) | 1 | |

| Gravidity | ||||

| Primigravida | 108 (54.5) | 90 (45.5) | 1 | |

| Paucigravida | 209 (64.5) | 115 (35.5) | 1.51* [1.06 – 2.17] | 1.38 [0.94 – 2.04] |

| Multigravida | 84 (68.9) | 38 (31.1) | 1.84* [1.14 – 2.96] | 1.66* [1.08 – 3.14] |

| Parity | ||||

| Primiparous | 112 (54.1) | 95 (45.9) | 1 | |

| Pauciparous | 207 (64.1) | 116 (35.9) | 1.51* [1.06 – 2.15] | 1.27 [0.82 – 1.95] |

| Multiparous | 85 (70.8) | 35 (29.2) | 2.06** [1.28 – 3.33] | 1.62* [1.13 – 3.18] |

| Knowledge of the recommended dose of SP | ||||

| No | 310 (87.6) | 44 (12.4) | 21.38*** [13.88 – 32.91] | 6.82** [3.21 – 14.49] |

| Yes | 59 (24.8) | 179 (75.2) | 1 | |

| Start of SP intake | ||||

| ≥ 5th month | 193 (68.4) | 89 (31.6) | 1.57** [1.14 – 2.16] | 2.28** [1.41 – 3.67] |

| 4th month | 236 (58.0) | 171 (42.0) | 1 | |

| Side effects during SP intake | ||||

| Yes | 233 (66.6) | 117 (33.4) | 1.45* [1.07 – 1.98] | 1.58* [1.02 – 2.46] |

| No | 196 (57.8) | 143 (42.2) | 1 | |

* = p < 0.05; ** = p < 0.01; *** = p < 0.001

OR = Odds Ratio

AOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio

IPTp-SP3− : Less than three doses of intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine during pregnancy

References

- World Health Organization. World malaria report 2024: addressing inequity in the global malaria response [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 24]. 293 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2024.

- Kojom Foko LP, Singh V. Malaria in pregnancy in India: a 50-year bird’s eye. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1150466. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1150466/full. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1150466.

- Nana RRD, Hawadak J, Foko LPK, Kumar A, Chaudhry S, Arya A, Singh V. Intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine pyrimethamine for malaria: a global overview and challenges affecting optimal drug uptake in pregnant women. Pathog Glob Health. 2023;117(5):462-75. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/20477724.2022.2128563. doi: 10.1080/20477724.2022.2128563.

- World Health Organization. Intermittent preventative treatment to reduce the risk of malaria during pregnancy [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2023 [cited 2025 Oct 24]. Available from: https://www.who.int/tools/elena/interventions/iptp-pregnancy.

- Organisation Mondiale de la Santé. Lignes directrices de l’OMS sur le paludisme, 2021 [Internet]. Genève (Switzerland): Organisation Mondiale de la Santé; 2021 [cited 2023 Oct 30]. 225 p. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/344167/WHO-UCN-GMP-2021.01-fre.pdf.

- ter Kuile FO, van Eijk AM, Filler SJ. Effect of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine resistance on the efficacy of intermittent preventive therapy for malaria control during pregnancy: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;297(23):2603-16. Available from: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.297.23.2603. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.23.2603.

- Kayentao K, Garner P, van Eijk AM, Naidoo I, Roper C, Mulokozi A, MacArthur JR, Luntamo M, Ashorn P, Doumbo OK, ter Kuile FO. Intermittent preventive therapy for malaria during pregnancy using 2 vs 3 or more doses of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and risk of low birth weight in Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2013;309(6):594-604. Available from: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.2012.216231. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.216231.

- Eboumbou Moukoko CE, Kojom Foko LP, Ayina A, Tornyigah B, Epote AR, Penda IC, Epee Eboumbou P, Ebong SB, Texier G, Nsango SE, Ayong L, Tuikue Ndam N, Same Ekobo A. Effectiveness of intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in pregnancy: low coverage and high prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum dhfr-dhps quintuple mutants as major challenges in Douala, an urban setting in Cameroon. Pathogens. 2023;12(6):844. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0817/12/6/844. doi: 10.3390/pathogens12060844.

- Tackie V, Seidu AA, Osei M. Factors influencing the uptake of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria among pregnant women: a cross-sectional study. J Public Health (Berl). 2020;29(5):1205-13. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10389-020-01234-x. doi: 10.1007/s10389-020-01234-x.

- Darteh EKM, Dickson KS, Ahinkorah BO, Owusu BA, Okyere J, Salihu T, Bio Bediako V, Budu E, Agbemavi W, Edjah JO, Seidu AA. Factors influencing the uptake of intermittent preventive treatment among pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa: a multilevel analysis. Arch Public Health. 2021;79(1):182. Available from: https://archpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13690-021-00707-z. doi: 10.1186/s13690-021-00707-z.

- Darteh EKM, Buabeng I, Akuamoah-Boateng C. Uptake of intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy for malaria in Ghana: further analysis of the 2016 Malaria Indicator Survey. DHS Working Paper No. 158. Rockville (MD): United States Agency for International Development; 2019. 24 p. Available from: https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/WP158/WP158.pdf.

- Malpass A, Hansen N, Dentinger CM, Youll S, Cotte A, Mattern C, Ravaoarinosy A. Status of malaria in pregnancy services in Madagascar 2010–2021: a scoping review. Malar J. 2023;22(1):59. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-023-04497-3. doi: 10.1186/s12936-023-04497-3.

- Enguita-Fernàndez C, Alonso Y, Lusengi W, Mayembe A, Manun’Ebo MF, Ranaivontiavina S, Rasoamananjaranahary AM, Mucavele E, Macete E, Nwankwo O, Meremikwu M, Roman E, Pagnoni F, Menéndez C, Munguambe K. Trust, community health workers and delivery of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy: a comparative qualitative analysis of four sub-Saharan countries. Glob Public Health. 2021;16(12):1889-903. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17441692.2020.1851742. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2020.1851742.

- Institut National de la Statistique (MG), UNICEF. Enquête par grappes à indicateurs multiples-MICS Madagascar, 2018 [Internet]. Antananarivo (Madagascar): INSTAT, UNICEF; 2019 [cited 2025 Oct 24]. 919 p. Available from: https://www.instat.mg/p/mics-2018-rapport-des-resultats-de-lenquete-aout-2019.

- Institut National de la Statistique (MG), ICF. Enquête Démographique et de Santé à Madagascar, 2021: Indicateurs Clés [Internet]. Antananarivo (Madagascar): Institut National de la Statistique (MG), ICF; 2021 [cited 2025 Oct 24]. 55 p. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/madagascar/media/7286/file/INSTAT_EDSMD-V_Indicateurs-cl%C3%A9s.pdf.

- Awantang GN, Babalola SO, Koenker H, Fox KA, Toso M, Lewicky N. Malaria-related ideational factors and other correlates associated with intermittent preventive treatment among pregnant women in Madagascar. Malar J. 2018;17(1):176. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-018-2308-3. doi: 10.1186/s12936-018-2308-3.

- Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications; 2017. 795 p.

- Centre de recherches, d’études et d’appui à l’analyse économique à Madagascar. Monographie de la région Atsimo Atsinanana [Internet]. Antananarivo (Madagascar): CREAM; 2014 [cited 2025 Oct 24]. 222 p. Available from: https://www.pseau.org/outils/ouvrages/mg_mef_monographie-region-atsimo-atsinanana_2014.pdf.

- Institut National de la Statistique (MG). Troisième Recensement Général de la Population et de l’Habitat de Madagascar (RGPH-3) – Projection démographique. Antananarivo (Madagascar): INSTAT; 2020. Available from: https://www.instat.mg/p/rgph-3-rapport-thematique-theme-18-projections-demographiques.

- Ministère de la Santé (MG). Plan de Développement du Secteur Santé 2020 – 2024 [Internet]. Antananarivo (Madagascar): Ministère de la Santé (MG); 2020 [cited 2025 Oct 14]. Available from: https://www.sun-hina-madagascar.org/sites/default/files/fichiers/texte_lois/plan-de-developpement-du-secteur-sante-2020-2024_1.pdf.

- Arnaldo P, Rovira-Vallbona E, Langa JS, Salvador C, Guetens P, Chiheb D, Xavier B, Kestens L, Enosse SM, Rosanas-Urgell A. Uptake of intermittent preventive treatment and pregnancy outcomes: health facilities and community surveys in Chókwè district, southern Mozambique. Malar J. 2018;17(1):109. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-018-2255-z. doi: 10.1186/s12936-018-2255-z.

- Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. Statistical inference for a single proportion. In: Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons; 2003. p. 17-49. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/0471445428. doi: 10.1002/0471445428.ch2.

- Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. Determining sample sizes needed to detect a difference between two proportions. In: Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons; 2003. p. 64-85. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/0471445428.ch4. doi: 10.1002/0471445428.ch4.

- Diarra SS, Konaté D, Diawara SI, Tall M, Diakité M, Doumbia S. Factors associated with intermittent preventive treatment of malaria during pregnancy in Mali. J Parasitol. 2019;105(2):299-302. Available from: https://bioone.org/journals/journal-of-parasitology/volume-105/issue-2/17-141/Factors-Associated-with-Intermittent-Preventive-Treatment-of-Malaria-During-Pregnancy/10.1645/17-141.full. doi: 10.1645/17-141.

- Masoi TJ, Moshi FV, Tungaraza MB. Factors associated with uptake of intermittent preventive treatment for malaria during pregnancy: analysis of data from the Tanzania 2015-2016 Demographic Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey. East Afr Health Res J. 2022;6(2):134-40. Available from: https://eahrj.eahealth.org/eah/article/view/692. doi: 10.24248/eahrj.v6i2.692.

- Anchang-Kimbi JK, Kalaji LN, Mbacham HF, Wepnje GB, Apinjoh TO, Ngole Sumbele IU, Dionne-Odom J, Tita ATN, Achidi EA. Coverage and effectiveness of intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP) on adverse pregnancy outcomes in the Mount Cameroon area, South West Cameroon. Malar J. 2020;19(1):100. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-020-03155-2. doi: 10.1186/s12936-020-03155-2.

- Amankwah S, Anto F. Factors associated with uptake of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy: a cross-sectional study in private health facilities in Tema Metropolis, Ghana. J Trop Med. 2019;2019:9278432. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jtm/2019/9278432/. doi: 10.1155/2019/9278432.

- Mwandagalirwa MK, Levitz L, Thwai KL, Parr JB, Goel V, Janko M, Tshefu A, Emch M, Meshnick SR, Carrel M. Individual and household characteristics of persons with Plasmodium falciparum malaria in sites with varying endemicities in Kinshasa Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Malar J. 2017;16(1):456. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-017-2110-7. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-2110-7.

- Sangho O, Tounkara M, Whiting-Collins LJ, Beebe M, Winch PJ, Doumbia S. Determinants of intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in pregnant women (IPTp-SP) in Mali, a household survey. Malar J. 2021;20(1):231. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-021-03764-5. doi: 10.1186/s12936-021-03764-5.

- Amoako BK, Anto F. Late ANC initiation and factors associated with sub-optimal uptake of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine in pregnancy: a preliminary study in Cape Coast Metropolis, Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):105. Available from: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-021-03582-2. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03582-2.

- Mutanyi JA, Onguru DO, Ogolla SO, Adipo LB. Determinants of the uptake of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy with sulphadoxine pyrimethamine in Sabatia Sub County, Western Kenya. Infect Dis Poverty. 2021;10(1):106. Available from: https://idpjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40249-021-00887-4. doi: 10.1186/s40249-021-00887-4.

- Owusu-Boateng I, Anto F. Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy: a cross-sectional survey to assess uptake of the new sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine five dose policy in Ghana. Malar J. 2017;16(1):323. Available from: http://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-017-1969-7. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1969-7.