Research | Open Access | Volume 8 (4): Article 105 | Published: 19 Dec 2025

Factors influencing the detection of noma cases in the West-Central region of Burkina Faso, 2024

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Tables

Table 1: Representation of themes and sub-themes

| Themes | Sub-themes |

|---|---|

| Knowledge and practices of healthcare providers at the operational level on noma | Knowledge about the definition of noma |

| Training received on noma | |

| Knowledge about the main cause of noma | |

| Systematic inspection of the mouth during consultations | |

| Notification of noma cases | |

| Collaboration with stakeholders | |

| Factors related to the provision of care and the geographical accessibility of health centers | Geographical accessibility of healthcare centres |

| Healthcare provision | |

| Availability of dental practices | |

| Availability of qualified human resources | |

| Availability of technical facilities and financial resources | |

| Factors related to the socio-political situation | |

| Socio-cultural and economic factors influencing the detection of noma | Community knowledge of noma |

| Therapeutic pathway and recourse to traditional health practitioners | |

| Cultural beliefs, stigma, discrimination and social exclusion |

Table 1: Representation of themes and sub-themes

Table 2: Distribution of study participants

| Status of Participants | Category | Effective | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operational level healthcare providers | Nurse | 5 | 19 |

| Dental nurses | 3 | ||

| Nutritionist | 1 | ||

| General practitioner | 4 | ||

| Dental surgeon | 1 | ||

| Maxillofacial surgeon | 2 | ||

| Pediatrician | 1 | ||

| CBW | 2 | ||

| Central health provider | 2 | ||

| Traditional health practitioners | 3 | ||

| Patient guardians | 7 | ||

| NGO leaders | 2 | ||

| Members of the local community | 18 | ||

| Total | 51 | ||

Table 2: Distribution of study participants

Figures

Keywords

- Noma

- Detection

- Factors

- Neglected tropical disease

- Burkina Faso

Sibdou Sandrine Ouédraogo1,2,&, Fatou Diawara1,3, Ipyn Eric Nébié4, Oumar Sangho1, Souleymane Sekou Diarra1, Souleymane Bougoum5,6, Youssouf Bagayan1,7, Christelle Djecko1,8

1Department of Teaching and Research in Public Health and Specialities, University of Sciences, Techniques and Technologies of Bamako, Mali, 2Direction Générale de la Santé Publique (DGSP), Ministère de la santé, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 3National Institute of Public Health, Bamako, Mali, 4Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland, 5Health Sciences Training and Research Unit, Joseph Ki-Zerbo University of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 6Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Yalgado Ouédraogo, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 7Unité de Recherche Clinique de Nanoro, Institut de Recherche en Sciences de la Santé, Nanoro, Burkina Faso, 8Institut National d’Hygiène Publique (INHP), Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire

&Corresponding author: Sibdou Sandrine Ouédraogo, Department of Teaching and Research in Public Health and Specialities, University of Sciences, Techniques and Technologies of Bamako, Mali, Email: os.sibdou@gmail.com, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-5277-0890

Received: 21 Oct 2025, Accepted: 19 Dec 2025, Published: 19 Dec 2025

Domain: Neglected Tropical Diseases

Keywords: Noma, detection, factors, neglected tropical disease, Burkina Faso

©Sibdou Sandrine Ouédraogo et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Sibdou Sandrine Ouédraogo et al., Factors influencing the detection of noma cases in the West-Central region of Burkina Faso, 2024. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8(4):105. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00248

Abstract

Introduction: Noma, a neglected tropical disease that mainly affects children aged 2-6 years, is a fulminant infection of the orofacial region. Early detection helps minimize its burden. Despite all the strategies implemented, its detection remains a challenge in the West-Central region of Burkina Faso. The objective of this study was to investigate the factors influencing the detection of noma in the region.

Methods: This was a qualitative study conducted with healthcare providers, traditional health practitioners, heads of non-governmental organizations, patient guardians and the local community. A total of 51 people participated in the study, through 33 interviews and three focus group discussions with six people each. The data were analysed thematically using Nvivo software version 14.

Results: Health providers were found to have a low level of awareness of noma and confusion with cleft lip and palate. The majority of health providers reported not systematically inspecting the mouth during their consultations. Noma detection in the West-Central region was also influenced by insufficient dental care, inaccessibility of health centres, insufficient technical and human resources, and reporting, which is always done monthly. At the community level, the lack of awareness of noma, reliance on traditional health practitioners, lack of money, cultural beliefs, and stigma hindered detection.

Conclusion: Noma detection was influenced by a lack of knowledge among health providers, its poor integration into surveillance systems, sociocultural, and economic factors. Continuous training of health providers and public awareness could be solutions.

Introduction

Noma or “cancrum” oris”, is a necrotizing infection affecting the orofacial region and rapidly progressing to severe complications [1]. In December 2023, it was officially added to the World Health Organization (WHO) list of neglected tropical diseases. Primarily affecting children aged 2–6 years, noma is often associated with chronic malnutrition, measles, malaria, HIV, poor oral hygiene, and low socioeconomic status [2–6].

In advanced stages, noma causes a heavy physical, psychological and economic burden [7–9]. Survivors suffer from severe disfigurements, affecting essential functions such as chewing, swallowing, speaking and breathing. It also leads to psychological trauma caused by stigma and social exclusion [7–9]. Early treatment would prevent complications and sequelae, and significantly reduce the mortality rate [3,5,10]. According to the WHO, early diagnosis and treatment significantly improve the prognosis of the disease [11]. Alerts can be given at different levels: by parents, the community or during medical consultations [11].

The global epidemiology of noma remains insufficiently documented. WHO estimates from 1998 report an annual incidence of 140,000 cases, a global prevalence of 770,000 people and a mortality rate reaching 90% in the absence of treatment [1]. However, these old data remain the most commonly cited. According to the WHO, only 15 to 20% of patients consult early enough to prevent severe complications [12]. In Africa, noma-related morbidity is particularly high in certain countries, notably Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria and Senegal, grouped together under the name of the “Noma belt” [1,13].

In Burkina Faso, several government initiatives, such as the national programme to combat neglected tropical diseases of the Ministry of Health through their strategic plan to combat neglected tropical diseases and non-governmental initiatives, have been implemented, including awareness campaigns and measures for early treatment of noma. In order to improve the detection of noma, its surveillance has been integrated into existing health status reporting systems, and its reporting has been made weekly since 2021. However, significant fluctuations and inconsistencies have been observed in the reporting of noma cases over the years in the West-Central region. In 2022, 19 cases of noma were reported in the West-central region according to the 2022 health statistics yearbook [14]. This number increased to 115 cases in 2023, according to the 2023 health statistics yearbook [15], while in 2024, 34 cases were reported in the same region [16]. These inconsistencies lead to underreporting and reduce the reliability of data, making year-to-year comparisons difficult and limiting the accuracy of the surveillance system

Challenges, therefore, persist despite all the efforts that have been made, particularly in the West-central region. Also, few studies have been found on the detection of noma in this region. It is in this context that we conducted this study in order to contribute to improving the noma detection system and to prevent the sequelae and mortality of this neglected disease. We proceeded by describing healthcare providers’ knowledge of noma in the West-central region in 2024; identifying healthcare providers’ practices in detecting noma; identifying the sociocultural and economic factors influencing the detection of noma in the West-central region, and proposing appropriate strategies to improve the early detection of noma cases in that region.

Methods

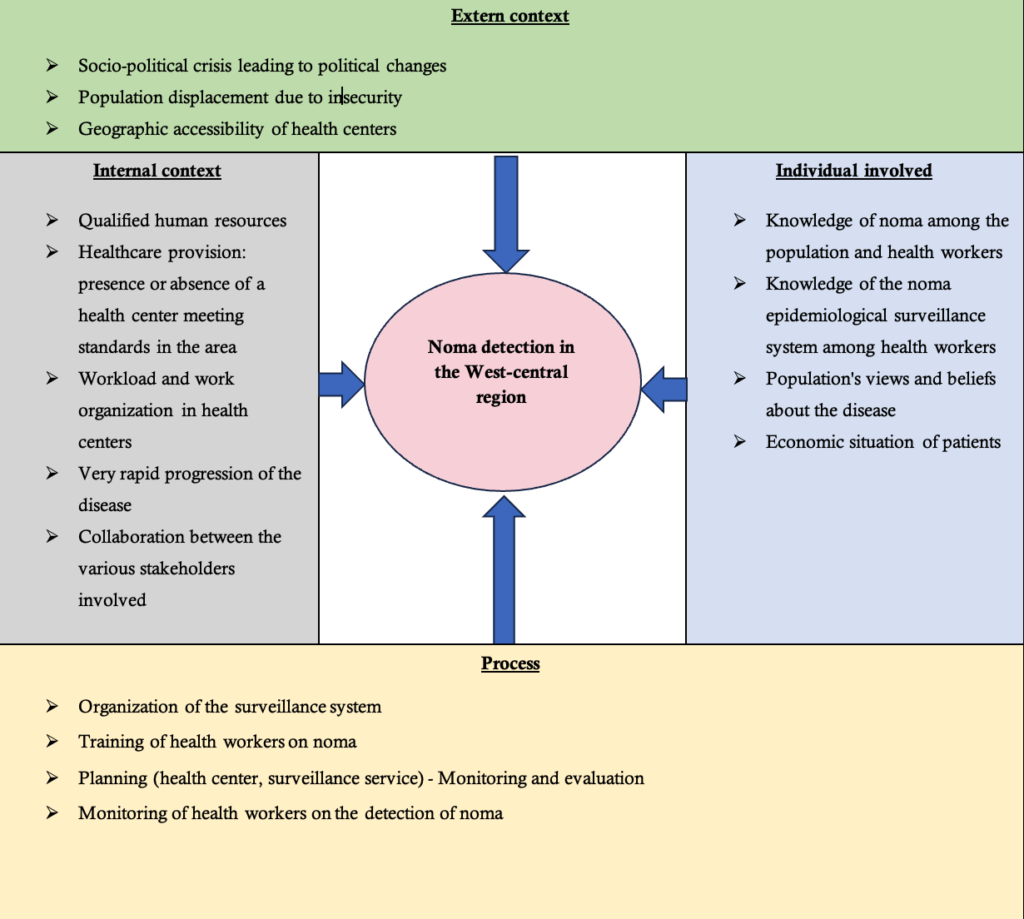

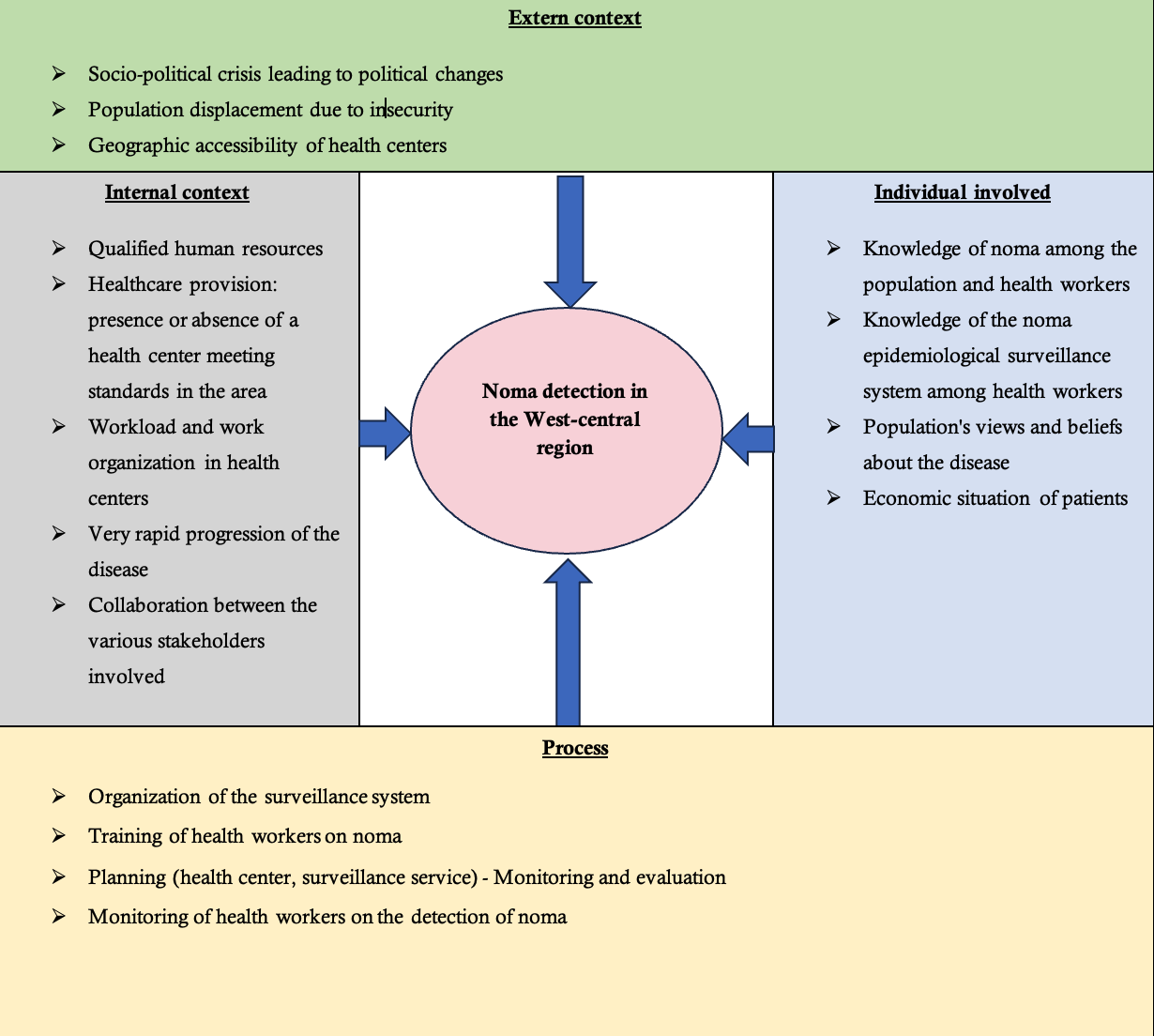

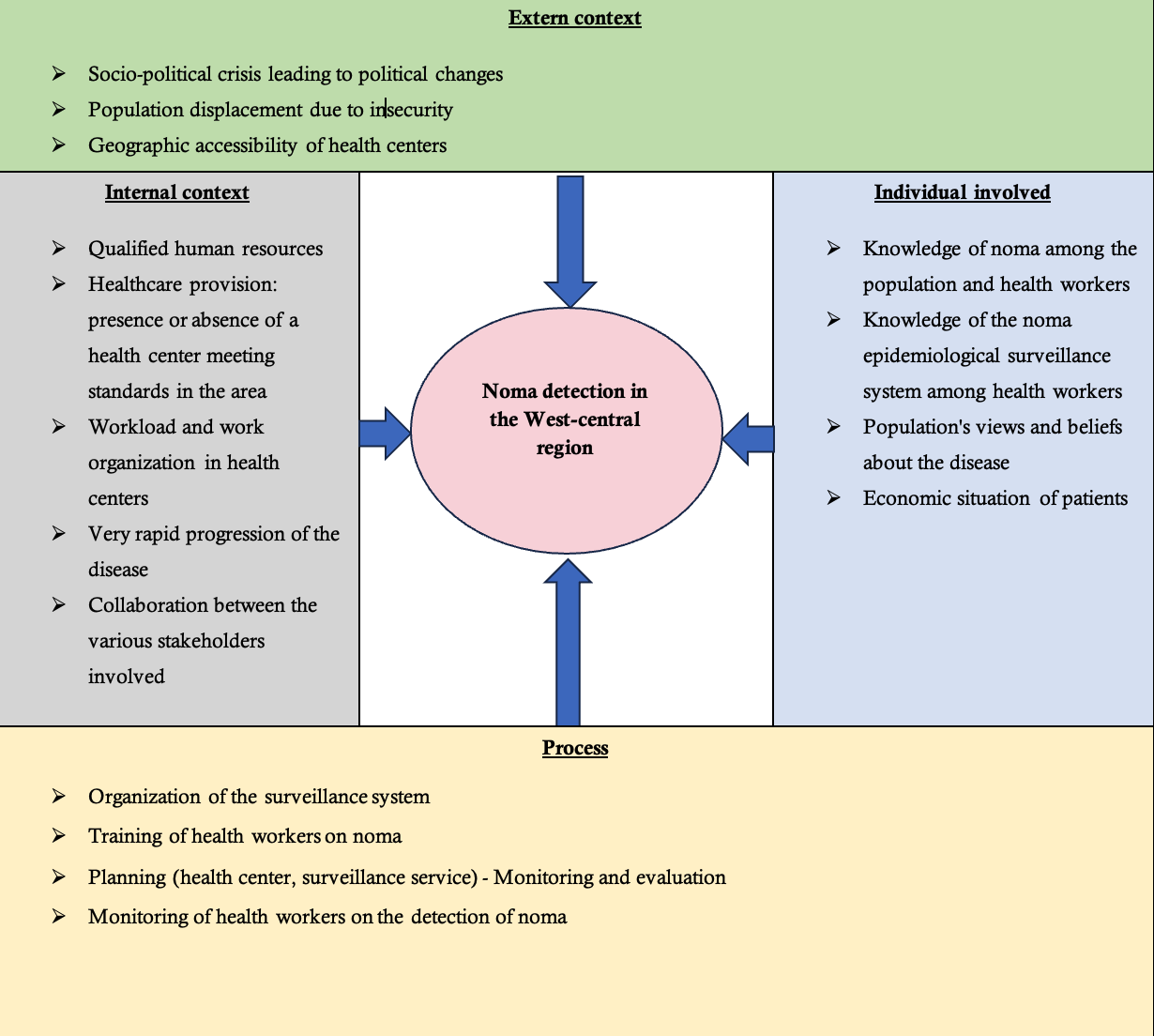

Conceptual framework

To better understand the factors influencing noma detection, we used the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), which presents the concepts and approaches for identifying implementation factors that may influence the applicability of results to a particular intervention [17,18]. Created in 2009 by Damschroder et al., it includes 5 domains: characteristics of the intervention, external context, internal context, individual factors and processes [17]. The framework adapted to the detection of noma was used to create the interview guides and for data analysis (Figure 1).

Study setting

The study was conducted in the West-Central region of Burkina Faso, which covers an area of 21,891 km². Demographically, according to the National Institute of Statistics and Demography 2022, the West-Central region had 1,660,135 inhabitants in 2019 [19]. The health statistics yearbook mentioned in 2023, one Regional Hospital Centre (CHR) and seven Health Districts (DS) with three Medical Centres with Surgical Antenna (CMA), 14 Medical Centres (CM), 235 Health and Social Promotion Centres (CSPS), one isolated dispensary, 15 infirmaries. The CHR of the region is based in Koudougou. In terms of health in 2021, 58% of its population were affected by food insecurity [20].

Study design and population

This study was conducted using a qualitative approach. We conducted semi-structured individual interviews and focus groups. The study population consisted of health providers at the operational and central levels, traditional health practitioners, managers of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) involved in the management of noma, guardians of patients with noma, and the local adult population. Participants who agreed to participate in the study and gave their consent to be recorded were included. Any participants who were not present or reachable during the data collection period were not included in our study.

Sampling

The sampling method was non-probabilistic through a reasoned choice of 56 participants until saturation was achieved by the stakeholder group.

At the operational level, a purposive sampling made it possible to select the CHR and three health districts according to the following criteria: the highest prevalence of malnutrition (DS of Réo ), the highest prevalence of measles (DS of Ténado), and the highest number of references in the region (DS of Koudougou). In total, 24 healthcare providers were selected there, distributed as follows: In the DS of Réo, one general practitioner from the CMA of Réo, one head nurse from a CSPS and one community health worker. In the DS of Ténado, one general practitioner from the CM of Ténado, one head nurse from a CSPS and one community health worker were selected. In the Koudougou DS, one general practitioner from the Koudougou CM, one dental nurse from the Municipal Oral and Dental Centre, one head nurse from a CSPS and one community health worker were selected. CSPS has notified cases in 2024: three nurses, three Community Health Workers. At the CHR level: one paediatrician, one dental surgeon, two maxillofacial surgeons; one general practitioner, two dental nurses, one nutritionist.

At the central level, a manager of the National Programme for the Fight against Neglected Tropical Diseases, a manager of the epidemiological surveillance service and two NGO managers were selected.

At the community level 28 participants, seven guardians of patients (were contacted through NGOs and health centres); three traditional health practitioners and 18 members of the local community chosen in collaboration with community leaders: six mothers, six grandmothers and six fathers.

Data collection

Data collection covered the period from December 1, 2024, to January 31, 2025. After obtaining ethical and administrative approvals, the investigators and translators were trained on the protocol and interview guides to ensure standardisation of methods, and a pretest was conducted to adjust the data collection tools. We then administered interview guides tailored to each type of participant to the participants face-to-face or by telephone when a face-to-face interview was not possible. These interviews were conducted in the participants’ preferred language using a dictaphone and lasted 30 minutes each. The contacts of the patients’ guardians were obtained from the databases of the health centres or the Sentinelles Foundation.

Three focus groups discussions were conducted with the local community: mothers, fathers, and grandmothers. Each session was held in regular meeting places and lasted approximately one hour.

Data analysis

The data obtained from the notes and transcripts of the individual and focus group interviews were cleaned, anonymized and transcribed then analysed thematically using the QSR NVivo software version 14. Participant names have been replaced by code: (HP for Healthcare provider, CBW: community-based health worker, CL: Central health worker, NGO for NGO Manager, T: Traditional health practitioner, PG: Patient guardian, PFGD: Participant of focus group). Then, themes and subthemes were identified. A deductive and inductive thematic analysis was adopted, using the CFIR domains and concepts to define the themes while including other themes suggested by the data. (Table 1)

Ethical considerations

The study received approval from the Burkina Faso Health Research Ethics Committee under number 2024-11-370, authorization from the Ministry of Health under number 2024-9464-MS/SG/DGESS/DPPSE and from the relevant health authorities. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant through a detailed information sheet. Anonymity and confidentiality were strictly respected. In-kind compensation was provided in the amount of 3,500 CFA francs. Research team members were trained in ethical principles.

Results

Participant characteristics

There were 19 operational health providers, two central health providers, two NGO managers, three traditional health practitioners, seven patient guardians, 18 local community members. The population consisted of 18 women and 33 men. Regarding operational health providers, initially planned for 24 participants, saturation was achieved after 19 participants, bringing the total number of participants to 51 people (Table 2).

Knowledge and practices of healthcare providers at the operational level on noma

While the majority of health workers claimed to have heard of noma, particularly during their initial training, few were able to give a precise definition or identify its main characteristics. For example, one health worker mentioned. Also, a major confusion was noted between noma and other maxillofacial pathologies, such as cleft lip and palate, also known as cleft lip. A nurse asked the question, ” Excuse me, is that noma that is cleft lip?” (HP12).

The lack of ongoing training or refresher training affected the accuracy of the definitions given. This was confirmed by a caregiver: “If you had told me about malaria or acute flaccid paralysis, I would have told you because we hear about that every day. But noma, it’s been a long time ago” (HP11).

One point raised in these interviews was the lack of systematic inspection of the mouth during consultations. Only oral health professionals systematically inspect the mouth. The majority of caregivers admitted to examining the oral cavity only when a patient presented oral pain or visible lesions. One nurse confided: “Systematically, no. It’s when the person says they have sores in their mouth that we try to see” (HP12).

Reporting errors were also noted. It turned out that a single CSPS had recorded more than 70 cases in 2023. After verification, it was found that this was a data entry error.

Since 2021, noma reporting has been made weekly in the Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) technical guide, but it was clear that noma still did not appear in the Weekly Official Letter Telegramme. “Indeed, noma reporting is still done monthly,” CL01, a manager at the Ministry of Health, told us. In a CSPS, a nurse also stated: “I have no idea about noma monitoring. In the TLOH, it’s not in there. As long as it’s not in there, monitoring is really difficult” (HP12).

Another important fact noted was the participation of community-based health workers (CBWs) in case detection. Indeed, some cases were discovered thanks to some CBWs: ” Once I even saw a child for that. They were displaced people. I sent them here (to the CSPS), then they went to the district ” (CBW02).

Factors related to the provision of care and the geographical accessibility of health centres

Some villages were located several kilometres from the CSPS with geographical obstacles such as dams or impassable roads, especially during the rainy season. This is the case here, explained by a village resident during a focus group discussion: ” The water fills the backwaters. You have to wait for it to decrease before you can pass and bring the patient to the CSPS, otherwise the water risks carrying you away” (P6FGD1).

One of the problems identified was the lack of dental care in some provinces. One community member explained: “There is no dental practice here. Except in Koudougou, about 40 km from here” (P1FGD1).

The number of health workers varied depending on the centres: Some rural health centres had two workers for several villages. This situation was deplored as follows: “If a health worker spends their time consulting morning, noon, and night, there is no rest on call, well! At a certain point we cannot do our best” (HP15).

There was also a lack of technical and financial resources for the activities of community health workers who act as community relays. The lack of a badge or badges often reduced their credibility. One community health worker expressed his disappointment: “It’s complicated. If you have to go somewhere, you have to pay for fuel, and often it’s the telephone units for calls” (CBW02).

Another obstacle to detecting noma was related to insecurity. Many areas had become inaccessible due to insecurity. However, malnutrition is rife in these areas. This hinders the activities of health centres and NGOs, limiting access to care.

Community knowledge of noma

The general ignorance surrounding noma was evident in discussions with the community. Many participants had never heard of this disease. However, some had identified it after seeing someone with it. The description given by these participants corresponded well to the symptoms of noma. The name in the local language is diverse. Some called it ” gniri ” in Gourounsi. » (P4FGD2) or « Nadiyo » (P6FGD1). In Mooré some called it « Roulgou » (T02), other « maskindi » (P5FGD3). The traditional practitioners interviewed recognized certain manifestations of noma, but their interpretations varied.

Therapeutic pathway and recourse to traditional health practitioners

Some participants admitted to visiting traditional practitioners. According to them, some illnesses were not “white people’s illnesses,” and therefore could not be treated in hospitals. Many former noma patients or their families had consulted traditional practitioners as a first-line treatment. This therapeutic process resulted in delayed detection: “We consulted a traditional practitioner, but my child’s condition only worsened. So we took him to the hospital.” (PG04). The patient’s guardians emphasized a sudden onset: “It came suddenly and quickly got worse. In no time. It started to eat away suddenly” (PG01). This testimony clearly illustrated the rapid and aggressive progression of noma, which often goes unnoticed or neglected until it is too late for early treatment.

As reasons for late access to care, the guardians of patients also cited economic problems: “At the beginning of the illness they gave us a prescription, but we didn’t have the money to pay” (PG07).

Cultural beliefs, stigma, discrimination and social exclusion

The origin of the disease was subject to different interpretations. While some recognized that it was a disease, others suggested mystical explanations. Some groups attributed noma to a curse, a spell cast by a malevolent spirit, or divine punishment. Others even accused sorcerers of being the cause. Families of the sick therefore turned to the occult sciences, delaying treatment: “At first, we thought someone had cast a spell on him. So we preferred to make sacrifices” (PG03).

Cultural beliefs often led to child abandonment or infanticide. The massive and sudden destruction of the face led families to believe that these children were inhuman: “I even saw a case where the mother was told to kill the child because the child was a dog, given how the child ate, when he wanted to drink water he had to stick out his tongue,” a health worker (HP05) told us. These beliefs influenced how patients were perceived and cared for.

The after-effects of noma were frightening for some people. Some patients had to drop out of school because of the mockery of their classmates and the fear of some parents of seeing their children contaminated. A parent of a patient explained to us the situation of his child: “After the intervention, he returned to school but the teacher did not want to take him back for fear of other parents who do not want to see my child near their children” (PG04). The stigma meant that parents preferred to hide the children, preventing its detection, a father explained this in these terms. Added to this was the abandonment of children by families. Indeed, two fathers of patients explained to us that their children had been abandoned by the mother after the onset of the disease. An NGO manager agreed: “There are parents who abandon children. Either it is the father, or the mother or the whole family who loses interest. This means that children would die” (NGO2).

Discussion

One of the major findings of this analysis was the lack of in-depth knowledge of noma among health workers, except those working in dentistry or maxillofacial surgery departments. Other authors in Burkina Faso in 2019 and 2022, and Zambia in 2017, also found that reported knowledge of noma was low [9,21,22]. In contrast, the study by Mujtaba et al. conducted in a higher education institution in Nigeria in 2022 found good knowledge among health workers [23]. This difference could be explained by the university context in which the study was conducted. Also, most participants in the study had not received any continuing education on noma, which suggests a de-actualization of knowledge.

In this study, a considerable confusion has been observed between noma and cleft lip and palate. This is thought to be due to the fact that cleft lip and palate, like noma, causes orofacial lesions and functional difficulties. This confusion could delay the management of noma, which is nevertheless a medical emergency. It could also lead to an underestimation or overestimation of noma cases, thus influencing public health strategies.

Although the reporting of noma cases was made weekly in 2021, it still remained monthly in practice. This goes against the recommendations of the IDSR guide, which stipulates that reporting should be weekly. This is believed to be due to the fact that noma has not yet been prioritized by the country, despite it being mentioned in the IDSR guide as a priority disease. The recent change in management of noma i.e. its recent inclusion in the national programme to combat neglected tropical diseases due to the fact that it has been newly added to the WHO list of neglected tropical diseases, was also given as a reason. This is in line with the results of Caulfield and Alfvén in 2020 who found that children with noma are reportedly undetected due to lack of follow-up and monitoring, and ignored due to lack of political will [24].

Previous studies showed that regular inspection of the mouth would identify the early signs of noma and every caregiver in the community should acquire the competency do it [11,25]. Rigorous surveillance of early oral lesions could allow early identification of symptoms before progression to severe forms.

The majority of the participants in this study turned first to traditional practitioners, especially when the disease was perceived as “strange”, which slowed down early case identification and favoured late presentation of the disease. Prior studies have also found similar results have also found similar results [9,26,27]. Lack of financial resources was mentioned to explain the delay in consultation and the use of traditional practitioners. Financial constraints had also been mentioned by other authors [7,9,28].

Noma was sometimes perceived as a curse or a spell cast by a malevolent spirit. Furthermore, shame and fear of being seen by others led some families to hide sick children. There was also family rejection due to cultural beliefs. This finding is in concord with reports by Wali et al. in their systematic review published in 2017, Srour et al. in 2017, Ahlgren et al. in 2017 in Zambia and Satapathy et al. in 2024 [8,22,29,30]. They could also lead to extreme practices such as infanticide, especially when the child was considered as a supernatural being or a divine punishment. These attitudes reflected a fear of the disease and this demonstrates that many cases remained undetected or that these cases died in secret without diagnosis. This underlines the urgency of increased awareness within communities.

Limitations of the study

One of the limitations of our study was language barriers. The interpretation of responses could be affected by linguistic differences. Indeed, in our study, it was necessary to use local translators, which could alter certain nuances of the speeches. However, these limitations were minimized by integrating a researcher who spoke local languages into our team to verify the accuracy of the translations. Despite these limitations, the findings of this study provide several important recommendations for improving the detection of noma

At the sociopolitical level, health authorities should strengthen health centres by ensuring the availability of qualified personnel and essential equipment. Continuous in-service training on noma should be provided to health workers. The epidemiological surveillance system should be improved by integrating noma into routine monitoring tools, ensuring their availability at peripheral levels, and strengthening users’ technical capacities to minimize reporting errors. Greater involvement of community health workers should be promoted through capacity-building and the provision of adequate logistical resources to enhance active surveillance. In addition, traditional health practitioners should be trained to recognize early signs of noma and promptly refer suspected cases to health facilities.

At the level of healthcare providers, routine systematic oral examinations should be integrated into all medical consultations. Health workers should be encouraged to regularly update their knowledge on the management of neglected tropical diseases, particularly noma. Improved diligence in case notification and record keeping is also essential.

At the community level, families and community members should be encouraged to promptly inform health workers when a child presents with suspicious symptoms. Community sensitization efforts should also aim to reduce stigma and discourage the hiding or rejection of patients affected by noma.

Conclusion

Noma detection remains a major challenge in the West-Central region of Burkina Faso. This devastating disease faces numerous obstacles that hinder its identification. This study highlighted several obstacles to noma detection, including inadequate knowledge among healthcare providers at the operational level, traditional health practitioners, and the community in general, and the poor integration of noma into surveillance systems. In addition, sociocultural factors such as stigmatization of patients and their families, social exclusion, and beliefs attributing noma to supernatural causes contribute to families’ reluctance to seek medical help. Added to this are economic constraints and insufficient healthcare provision, further aggravating the situation. To better understand these challenges, a larger-scale study covering all regions of the country would be necessary. In the meantime, a strategy based on an integrated, multisectoral approach, combining capacity-building, community awareness, and improvement of health facilities, would optimize case identification. Early detection and prompt management are essential to reduce the prevalence of noma and improve the prognosis of affected children.

What is already known about the topic

- The detection of noma may be influenced by the rapid progression of the disease and the high mortality rate associated with its acute phase

- Insecurity poses an obstacle to the detection of noma

- The stigma associated with the disease prevents its detection

What this study adds

- Lack of awareness of noma among health providers in the central-western region of Burkina Faso due to insufficient training leads to confusion with other maxillofacial pathologies, resulting in overestimation or underestimation of noma cases.

- Case reporting remains monthly in the region because the disease is not integrated into weekly reporting tools.

- The lack of evidence in the West-Central region is also due to case reporting errors.

- The majority of noma sufferers resort to traditional practitioners, delaying detection activities.

- The lack of dental care in the West-Central region influences the detection of noma.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank UNICEF/UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) for funding our master’s degree in implementation research and for funding the production of this article. Our thanks also go to the heads of the selected structures and the participants for their cooperation and anyone who contributed to the completion of this study.

Authors´ contributions

List of abbreviations

CBW: community-based health worker,

CHR: Regional Hospital Centre

CL: Central health worker,

CM: Medical Centre

CMA: Medical Centre with Surgical Unit

CSPS: Centre for Health and Social Promotion

DS: Health District

HP: Healthcare provider,

IDSR: Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response

NGO: Non-Governmental Organization

PFGD: Participant of focus group

PG: Patient guardian

T: Traditional health practitioner

WHO: World Health Organization

| Themes | Sub-themes |

|---|---|

| Knowledge and practices of healthcare providers at the operational level on noma | Knowledge about the definition of noma |

| Training received on noma | |

| Knowledge about the main cause of noma | |

| Systematic inspection of the mouth during consultations | |

| Notification of noma cases | |

| Collaboration with stakeholders | |

| Factors related to the provision of care and the geographical accessibility of health centers | Geographical accessibility of healthcare centres |

| Healthcare provision | |

| Availability of dental practices | |

| Availability of qualified human resources | |

| Availability of technical facilities and financial resources | |

| Factors related to the socio-political situation | |

| Socio-cultural and economic factors influencing the detection of noma | Community knowledge of noma |

| Therapeutic pathway and recourse to traditional health practitioners | |

| Cultural beliefs, stigma, discrimination and social exclusion |

| Status of Participants | Category | Effective | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operational level healthcare providers | Nurse | 5 | 19 |

| Dental nurses | 3 | ||

| Nutritionist | 1 | ||

| General practitioner | 4 | ||

| Dental surgeon | 1 | ||

| Maxillofacial surgeon | 2 | ||

| Pediatrician | 1 | ||

| CBW | 2 | ||

| Central health provider | 2 | ||

| Traditional health practitioners | 3 | ||

| Patient guardians | 7 | ||

| NGO leaders | 2 | ||

| Members of the local community | 18 | ||

| Total | 51 | ||

References

- Galli A, Brugger C, Fürst T, Monnier N, Winkler MS, Steinmann P. Prevalence, incidence, and reported global distribution of noma: a systematic literature review. Lancet Infect Dis [Internet]. 2022 Mar;22(8):e221–e230 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1473309921006988; doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00698-8

- Srour ML, Marck KW, Baratti-Mayer D. Noma: neglected, forgotten and a human rights issue. Int Health [Internet]. 2015 Jul;7(3):149–150 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/inthealth/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/inthealth/ihv001; doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihv001

- Ashok N, Tarakji B, Darwish S, Rodrigues JC, Altamimi MA. A review on noma: a recent update. Glob J Health Sci [Internet]. 2016 Jan;8(4):53–62 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: http://www.ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/gjhs/article/view/48228; doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n4p53

- Baratti-Mayer D, Gayet-Ageron A, Hugonnet S, François P, Pittet-Cuenod B, Huyghe A, et al. Risk factors for noma disease: a 6-year, prospective, matched case-control study in Niger. Lancet Glob Health [Internet]. 2013 Aug;1(2):e87–e96 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2214109X13700159; doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70015-9

- Maguire BJ, Shrestha P, Rashan S, Shrestha R, Harriss E, Varenne B, et al. Protocol for a systematic review of the evidence-based knowledge on the distribution, associated risk factors, the prevention and treatment modalities for noma. Wellcome Open Res [Internet]. 2023;8:125 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: https://wellcomeopenresearch.org/articles/8-125/v1; doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.19033.1

- Farley E, Lenglet A, Ariti C, Jiya NM, Adetunji AS, Van Der Kam S, et al. Risk factors for diagnosed noma in northwest Nigeria: a case-control study, 2017. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2018 Aug;12(8):e0006631 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0006631; doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006631

- Farley E, Lenglet A, Abubakar A, Bil K, Fotso A, Oluyide B, et al. Language and beliefs in relation to noma: a qualitative study, northwest Nigeria. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2020 Jan;14(1):e0007972 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007972; doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007972

- Wali IM, Regmi K. People living with facial disfigurement after having had noma disease: a systematic review of the literature. J Health Psychol [Internet]. 2016 Sep;22(10):1243–1255 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1359105315624751; doi: 10.1177/1359105315624751

- Kagoné M, Mpinga EK, Dupuis M, Moussa-Pham MSA, Srour ML, Grema MSM, et al. Noma: experiences of survivors, opinion leaders and healthcare professionals in Burkina Faso. Trop Med Infect Dis [Internet]. 2022 Jul;7(7):142 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2414-6366/7/7/142; doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed7070142

- Tonna JE, Lewin MR, Mensh B. A case and review of noma. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2010 Dec;4(12):e869 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0000869; doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000869

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for Africa, Non Communicable Diseases Cluster (NCD) Regional Programme for Noma Control. Noma is a severe disease. It is treatable if detected and managed early: information brochure for early detection and management of noma [Internet]. Brazzaville (Congo): WHO Regional Office for Africa; 2016 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. 23 p. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2017-07/Information_brochure_EN.pdf

- World Health Organization. Noma today: a public health problem?: report of an expert consultation organized by the Oral Health Unit of the World Health Organization using the Delphi method [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 1998 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. 28 p. (Doc. No.: WHO/MMC/NOMA/98.1). Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/63908

- Gill M. Book review: the challenge of oral disease: a call for global action. Br Dent J [Internet]. 2016 Dec;221(11):687 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/sj.bdj.2016.898; doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.898

- Ministère de la Santé et de l’Hygiène publique (Burkina Faso). Annuaire statistique 2022 [Statistical Yearbook 2022] [Internet]. Burkina Faso: Direction générale des études et des statistiques sectorielles; 2023 May [cited 2025 Dec 19]. 290 p. Available from: http://cns.bf/IMG/pdf/annuaire_2022_mshp_signe.pdf

- Ministère de la Santé et de l’Hygiène publique (Burkina Faso). Annuaire statistique 2023 [Statistical Yearbook 2023] [Internet]. Burkina Faso: Direction générale des études et des statistiques sectorielles; 2024 Jun [cited 2025 Dec 19]. 411 p. Available from: http://cns.bf/IMG/pdf/annuaire_2023_mshp_signe_020824.pdf

- Ministère de la Santé et de l’Hygiène publique (Burkina Faso). Annuaire statistique 2023 [Statistical Yearbook 2023] [Internet]. Burkina Faso: Direction générale des études et des statistiques sectorielles; 2025 Apr [cited 2025 Dec 19]. 449 p. Available from: https://www.sante.gov.bf/fileadmin/annuaire_2024_ms__signe___18062025.pdf

- Kirk MA, Kelley C, Yankey N, Birken SA, Abadie B, Damschroder L. A systematic review of the use of the consolidated framework for implementation research. Implement Sci [Internet]. 2016 May;11(1):72 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: http://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-016-0437-z; doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0437-z

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci [Internet]. 2009 Aug;4:50 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: http://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50; doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

- Institut National de la Statistique et de la Démographie (Burkina Faso). Résultats du cinquième recensement général de la population et de l’habitation: monographie de la région du Centre-Ouest [Results of the Fifth General Population and Housing Census: Monograph of the Centre-West Region] [Internet]. Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso): INSD; 2022 Dec [cited 2025 Dec 19]. 164 p. Available from: https://www.insd.bf/sites/default/files/2023-02/MONOGRAPHIE%20DU%20CENTRE%20OUEST%205E%20RGPH.pdf

- Institut National de la Statistique et de la Démographie (Burkina Faso). Enquête Démographique et de Santé 2021 [2021 Demographic and Health Survey] [Internet]. Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso): INSD; 2023 Aug [cited 2025 Dec 19]. 768 p. Available from: https://www.insd.bf/sites/default/files/2023-09/EDS%20Burkina%20Faso%202021_VF_07-09-23.pdf

- Brattström-Stolt L, Funk T, Sié A, Ndiaye C, Alfvén T. Noma—knowledge and practice competence among primary healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study in Burkina Faso. Int Health [Internet]. 2019 Mar;11(4):290–296 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/inthealth/article/11/4/290/5250961; doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihy088

- Ahlgren M, Funk T, Marimo C, Ndiaye C, Alfvén T. Management of noma: practice competence and knowledge among healthcare workers in a rural district of Zambia. Glob Health Action [Internet]. 2017 Jul;10(1):1340253 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/16549716.2017.1340253; doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1340253

- Mujtaba B, Chimezie CB, Braimah RO, Taiwo AO, Adebayo IA, Ndubuizu GU, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practices of health care workers towards noma in a tertiary institution in north-western Nigeria: knowledge, attitude and practices towards noma. Nig J Dent Res [Internet]. 2022;7(2):110–115 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/njdr/article/view/229543; doi: 10.4314/njdr.v7i2.6

- Caulfield A, Alfvén T. Improving prevention, recognition and treatment of noma. Bull World Health Organ [Internet]. 2020 May;98(5):365–366 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7265945/pdf/BLT.19.243485.pdf; doi: 10.2471/BLT.19.243485

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for Africa. Promoting oral health in Africa: prevention and control of oral diseases and noma as part of essential noncommunicable disease interventions [Internet]. Brazzaville (Republic of Congo): WHO Regional Office for Africa; 2016 May [cited 2025 Dec 19]. 108 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/promoting-oral-health-in-africa-prevention-and-control-of-oral-diseases-and-noma-as-part-of-essential-noncommunicable-disease-interventions

- Farley E, Bala HM, Lenglet A, Mehta U, Abubakar N, Samuel J, et al. ‘I treat it but I don’t know what this disease is’: a qualitative study on noma (cancrum oris) and traditional healing in northwest Nigeria. Int Health [Internet]. 2020 Mar;12(1):28–35 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/inthealth/article/12/1/28/5554319; doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihz066

- Baratti-Mayer D, Baba Daou M, Gayet-Ageron A, Jeannot E, Pittet-Cuénod B. Sociodemographic characteristics of traditional healers and their knowledge of noma: a descriptive survey in three regions of Mali. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2019 Nov;16(22):4587 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/16/22/4587; doi: 10.3390/ijerph16224587

- Mpinga EK, Srour ML, Moussa MSA, Dupuis M, Kagoné M, Grema MSM, et al. Economic and social costs of noma: design and application of an estimation model to Niger and Burkina Faso. Trop Med Infect Dis [Internet]. 2022 Jul;7(7):119 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2414-6366/7/7/119; doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed7070119

- Satapathy P, Rustagi S, Kumar P, Khatib MN, Gaidhane S, Zahiruddin QS, et al. Understanding noma: WHO’s recognition and the path forward in global health. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 2024 Sep;118(9):625–628 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/trstmh/article/118/9/625/7665301; doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trae031

- Srour ML, Marck K, Baratti-Mayer D. Noma: overview of a neglected disease and human rights violation. Am J Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 2017 Feb;96(2):268–274 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: https://www.ajtmh.org/view/journals/tpmd/96/2/article-p268.xml; doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0718