Research![]() | Volume 8, Article 28, 30 Apr 2025

| Volume 8, Article 28, 30 Apr 2025

Infection prevention and control implementation at cholera treatment facilities in Kadoma City, Zimbabwe, 2024

Clayton Munemo1, Daniel Chirundu2, Tsitsi Juru3, Gerald Shambira1, Addmore Chadambuka3, Notion Gombe4, Gibson Mandozana1, Mufuta Tshimanga1,3

1University of Zimbabwe, Department of Global Public Health and Family Medicine, Harare, Zimbabwe, 2Kadoma City Health and Environmental Services Department, Kadoma, Zimbabwe, 3Zimbabwe Field Epidemiology Training Program, Harare, Zimbabwe, 4African Field Epidemiology Network, Harare, Zimbabwe

&Corresponding author: Addmore Chadambuka, Zimbabwe Field Epidemiology Training Program, Harare, Zimbabwe, Email address: achadambuka1@yahoo.co.uk

Received: 06 Dec 2024, Accepted: 04 Apr 2025, Published: 30 Apr 2025

Domain: Infection Prevention and Control, Infectious Disease Epidemiology

Keywords: Infection Prevention and Control, Cholera Treatment Center, Oral Rehydration Points

©Clayton Munemo et al Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Clayton Munemo et al Infection prevention and control implementation at cholera treatment facilities in Kadoma City, Zimbabwe, 2024. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8:28. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-24-02008

Abstract

Introduction: In 2023, Zimbabwe declared a cholera outbreak that spread across multiple cities, reaching Kadoma by January 2024. Cholera outbreaks pose a major public health threat due to their potential to spread rapidly. Inadequate infection prevention and control (IPC) measures in treatment facilities can accelerate disease transmission, putting healthcare workers, patients, and surrounding communities at risk. Evaluating IPC implementation during outbreaks is essential to identify gaps, improve adherence to guidelines, and strengthening outbreak preparedness and response. We evaluated IPC implementation at a cholera treatment center (CTC) and oral rehydration points (ORPs) during the 2024 cholera outbreak in Kadoma, Zimbabwe.

Methods: A mixed method approach incorporating quantitative (descriptive cross-sectional) and qualitative data collection techniques was used. Data on demographics, IPC knowledge and training, availability of IPC resources and adherence to guidelines were collected from May to June 2024. Data collection tools included a structured questionnaire, records review, checklists, and direct observations. Quantitative data were analyzed using Epi Info 7.2.5™ to calculate means and proportions, presented as tables and charts. Qualitative data were thematically analyzed to identify key findings and recommendations.

Results: We recruited 146 respondents for the study. Most were auxiliary staff 74 (50.7%) and community health workers 31 (21.2%). Ninety-two respondents (63.0%) had good knowledge of IPC, and 84 (57.5%) had received IPC training. The CTC had adequate IPC supplies lasting over 14 days, while ORPs faced shortages with key resources not lasting more than 7 days. The setup of all cholera treatment facilities (1 CTC and 5 ORPs) adhered to the Global Task Force on Cholera Control (GTFCC) and Zimbabwe Cholera Control manual guidelines. Seventy-eight (53.4%) of respondents perceived staff shortages as the main IPC implementation barrier.

Conclusion: Most respondents demonstrated good IPC knowledge and the cholera treatment facilities setup adhered to the national and GTFCC guidelines. However, IPC implementation was affected by staff shortages and resource constraints, particularly at ORPs. Ensuring adequate supplies and continuous health worker training is essential for compliance with IPC practices.

Introduction

Infection prevention and control (IPC), recognized as a quality standard, is a critical component of healthcare systems. It is essential for ensuring the safety of patients, healthcare workers, and visitors within healthcare facilities and is particularly vital during outbreaks to minimize disease transmission [1,2]. Poor implementation of IPC measures has been linked to increased transmission of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) including, COVID-19, tuberculosis and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), all of which contribute to increased morbidity, mortality and healthcare cost [3–5]. The risk of HAIs is further amplified during infectious disease outbreaks, where overwhelmed healthcare systems struggle to maintain IPC standards, exacerbating disease burden [5,6].

In Africa, the 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak highlighted the importance of IPC, prompting significant improvements in its implementation across the continent [6]. However, sustaining these advancements remained a challenge due to persistent resource constrains [1,6]. In countries like Sierra Leone and Liberia, IPC strategies were enhanced through the establishment of national IPC programs and training of healthcare workers [7,8].Countries like Zambia, South Africa and Malawi, in Southern Africa have also made progress in integrating IPC policies into national health systems, though challenges such as inadequate resources and inconsistent adherence to IPC protocols persist [9–11]. Zimbabwe adopted the World Health Organization (WHO) IPC guidelines in 2012, with technical support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), but implementation remains hindered by limited financial support, inadequate training, and shortages of infection control professionals [1,12].

Cholera remains a major public health threat in Zimbabwe, with outbreaks occurring frequently due to poor water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure [13]. Since the first reported case in 1972, Zimbabwe has experienced multiple cholera outbreaks, including significant epidemics in 1992, 1999, 2002, 2008–2009, 2010, 2018–2019, 2022, and 2023–2024 [14,15]. The largest outbreak occurred between August 2008 and July 2009, resulting in 98,592 cases and 4,288 deaths [14]. In 2023, Zimbabwe experienced another widespread cholera outbreak, which reached Kadoma City by January 2024. In May 2024, Kadoma was among the cities that had reported a high number of cholera cases, recording a total of 2830 cases. The outbreak spread widely across Kadoma City, prompting the establishment of one cholera treatment center (CTC) and five community oral rehydration points (ORPs) to ensure timely access to treatment. From January to May 2024, 1175 cholera cases were attended to at the CTC, while 1655 suspected cases were managed at the community ORPs, with severe or deteriorating cases referred to the CTC for further care.

Infection prevention and control programs have proven to be both clinically and cost-effective, significantly reducing HAIs, shortening hospital stays, and mitigating antimicrobial resistance [2]. In settings like cholera treatment centers (CTCs) and oral rehydration points (ORPs), IPC measures play a pivotal role in preventing the spread of Vibrio cholera within and beyond the treatment facilities [16,17]. Adherence to IPC practices, such as proper hand hygiene, vector control, and waste management, can significantly reduce transmission of Vibrio cholera in these facilities [16,18].

Although IPC measures are being implemented in healthcare facilities across Zimbabwe, there is limited data on their implementation in outbreak settings, particularly in cholera treatment facilities (CTCs and ORPs). This study, therefore, aimed to evaluate IPC implementation at cholera treatment facilities in Kadoma City, Zimbabwe, during the 2024 cholera outbreak.

Methods

Study Setting

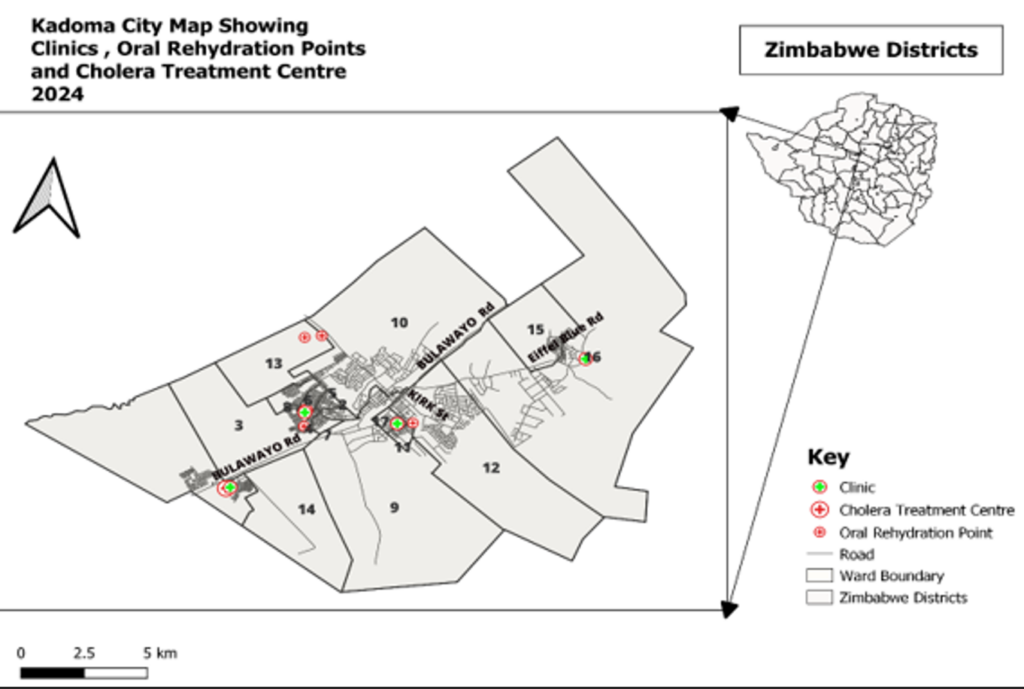

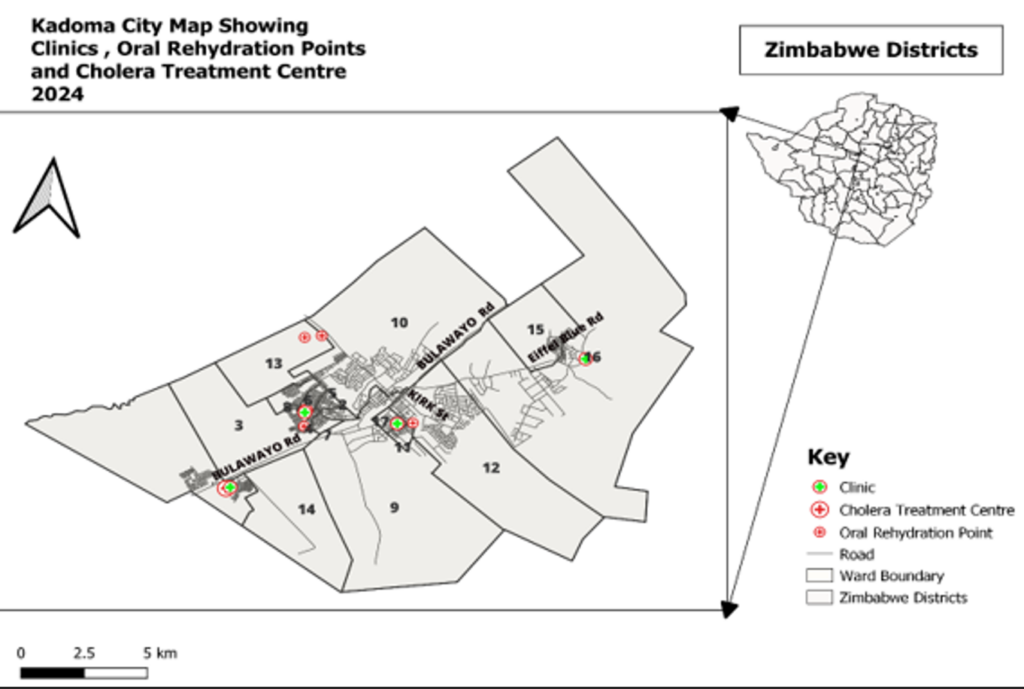

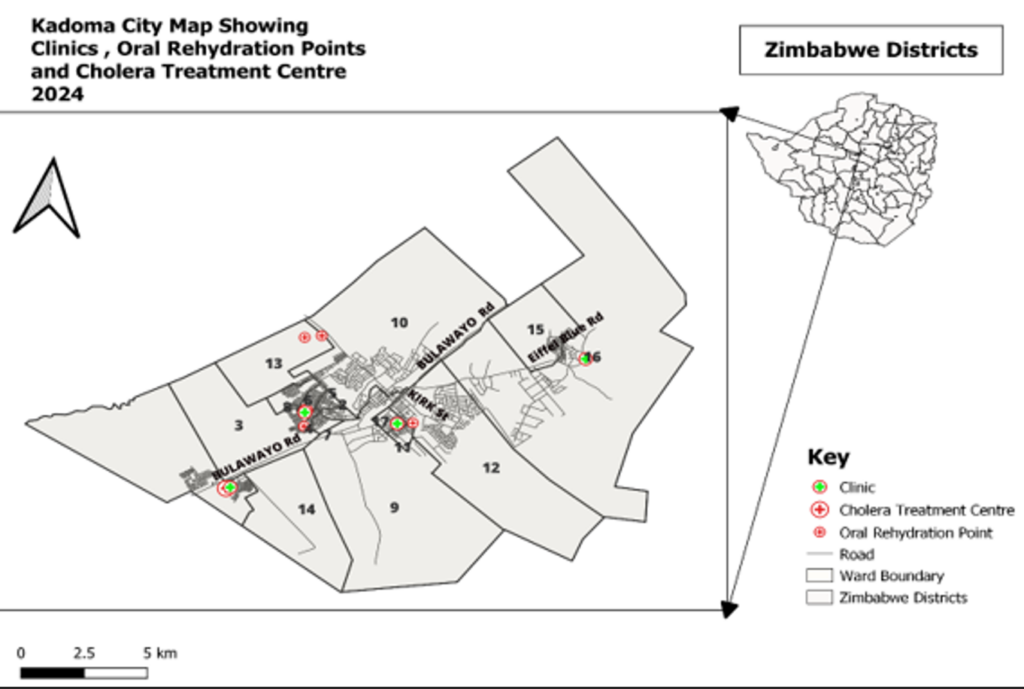

The study was conducted in Kadoma City, one of the 32 urban centers in Zimbabwe, located in Sanyati District, Mashonaland West Province. According to the 2022 central statistics office population and housing census report for Zimbabwe, the city had an estimated population of 117380, with approximately 40,000 households across 17 administrative wards [19]. Health services in Kadoma are provided through a network of six council clinics, eight private practitioners, two private hospitals, three uniformed forces clinics, and one government general hospital. Due to rapid population growth in recent years, the city faces challenges related to overcrowding in unplanned settlements, defective sanitation infrastructure, limited access to clean water, and poor hygiene practices, all of which increase the risk of cholera transmission. Kadoma has a history of cholera outbreaks, with notable occurrences in 2008–2009, 2018, 2023 and the most recent being in 2024. During the 2024 outbreak, cholera treatment services were provided at a designated Cholera Treatment Center (CTC) at Ngezi Clinic, while five Oral Rehydration Points (ORPs) were established in the most affected areas: Rimuka (2), Pixie Combie (2), and Waverly (1). The study setting and areas where the CTC and ORPs were established are presented in Figure 1.

Study Design

A mixed method approach incorporating quantitative (descriptive cross-sectional) and qualitative data collection techniques was used. This design enabled us to evaluate the implementation of infection prevention and control measures at cholera treatment facilities in Kadoma at a specific point in time and examine the study participants’ perceptions, which helped explain the observed quantitative data. The study was conducted between May and June 2024.

Study Population

The study population included healthcare workers, community health workers, cooks, administrative staff, cleaners and morticians working at the cholera treatment center and oral rehydration points in Kadoma. The IPC focal person and CTC camp coordinators were recruited as key informants.

Sample Size Determination

We calculated the sample size for the cross-sectional study with Epi Info software version 7.2.5™, using a prevalence of 11% for health workers demonstrating good knowledge of IPC based on a Zimbabwe study by Govha et. al. [12] and set a 95% confidence interval with a 5% margin of error. Additionally, a 10% allowance was included to account for potential refusals. The minimum required sample size calculated was 165 participants. However, due to logistical constraints, only 146 respondents were ultimately recruited, yielding a response rate of 88.5%.

Sampling Strategy

All cholera treatment facilities in Kadoma were included in the study. Workers at the treatment facilities were selected through stratified random sampling by duty roaster and profession. To ensure fair representation, workers were stratified according to their scheduled shifts (day and night), preventing overrepresentation from any specific shift. The workers were further stratified by profession (nurses, environmental health officers, nurse aides, community health workers, auxiliary staff etc.) to capture perspectives from different roles in IPC implementation. A proportionate number of participants were randomly selected from each stratum. Key informants were selected through purposive sampling to ensure the inclusion of individuals with in-depth knowledge of IPC implementation. They included (1) IPC focal person, (4) camp coordinators and (4) clinicians responsible for IPC decision-making at CTCs and ORPs.

Data collection

Data were collected using a pretested interviewer-administered questionnaire, which was developed on the Kobo Toolbox™ platform and later transferred to Open Data Kit™ (ODK) for offline mobile data collection. Additionally, checklists, records reviews, and structured observations were used to collect data. Records were reviewed to assess the outputs and outcomes of IPC implementation, including healthcare worker training, IPC meetings, and resource availability at the cholera treatment facilities.

A checklist was used to assess the implementation of IPC at cholera treatment facilities. The checklist was adopted from the WHO framework for IPC and the Global Task Force on Cholera Control (GTFFC) field manual [18,20]. This consisted of sections that assessed the facility layout, management of water supplies, toilets, showers, waste management, staffing protocols, and procedures.

A pretested interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to assess knowledge, barriers, and facilitators of IPC implementation among workers at the cholera treatment facilities. The questionnaire was pretested among 17 healthcare workers at clinics outside the study area to ensure clarity and reliability. Necessary adjustments were made to the questionnaire before final deployment for data collection. Discrete structured observations were also done on the personnel working at the cholera treatment facilities to confirm if they were adhering to the IPC protocols and procedures.

Data Analysis

Once collected, the data were uploaded to the Kobo ToolboxTM server, exported to Microsoft ExcelTM for cleaning, and analyzed using Epi Info 7.2.5TM. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize quantitative data, while qualitative data from observation, interviews and records were thematically analyzed to extract key findings and recommendations.

Measurement of Knowledge

A structured knowledge scale was used to assess respondents’ knowledge of IPC. A total of 9 questions adopted from literature were used and each correct answer was awarded one point. The total score for each respondent was then calculated. To classify knowledge levels, we employed a threshold approach based on established methods of measuring knowledge in public health [21]. Specifically, respondents achieving a score of at least 60% of the maximum possible points were classified as having good knowledge, while those scoring below this threshold were classified as having poor knowledge.

Ethical Considerations

Permission to carry out the evaluation was obtained from Kadoma City Council Institutional Review Board (IRB Number MUN/05/24). All respondents were asked for informed written consent before interviews and their names were not included on the questionnaires, assuring confidentiality.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

We recruited a total of 146 respondents from the Kadoma City Council workers who were actively involved in cholera response activities at the CTC and ORPs. Among those interviewed, 74 (50.7%) were auxiliary staff, 31 (21.2%) were community health workers, 7 (4.8%) were environmental health practitioners, and 4 (2.7%) were registered general nurses. Ninety-eight (67.1%) of the respondents were females. The respondent’s median duration of working at the CTC was 106 days (Q1=82; Q3=109). The median duration of working at the ORPs, was 49 days (Q1=16; Q3=106). The demographic characteristics of respondents are shown in Table 1.

Training and Knowledge of Infection Prevention and Control

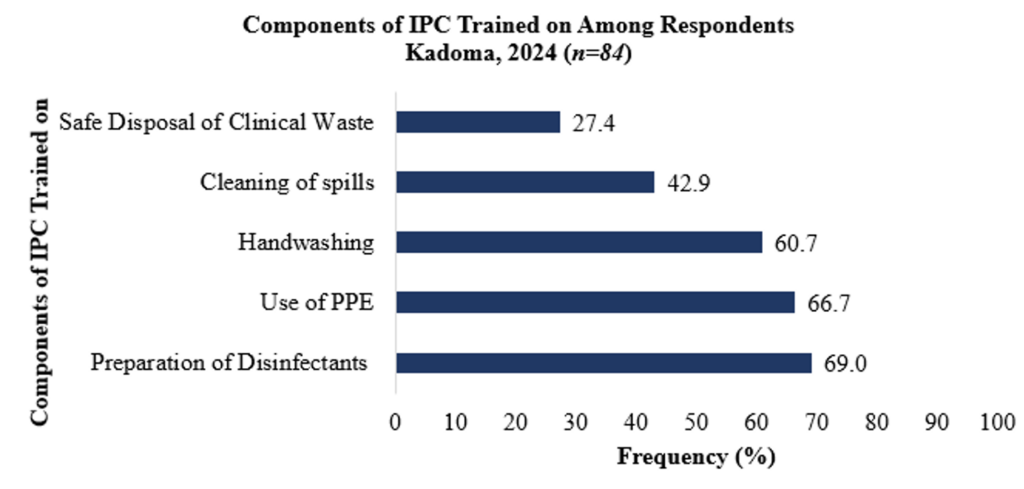

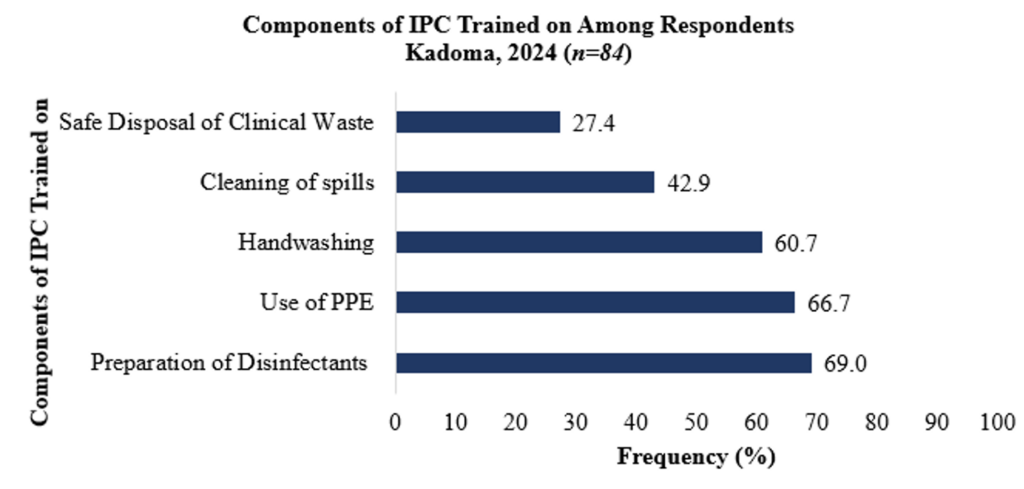

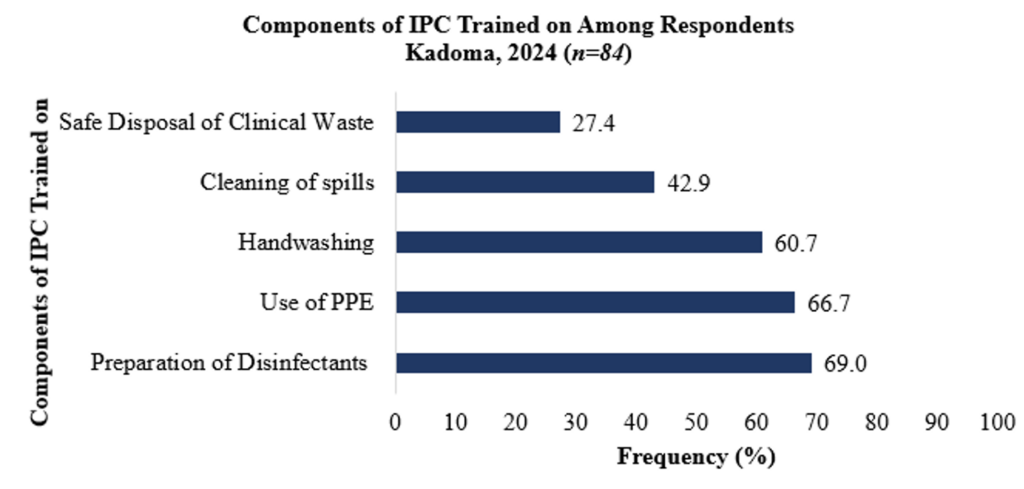

Out of the 146 respondents, 84 (57.5%) reported having received training on IPC before. The components of IPC they were trained on included preparation of disinfectants mentioned by 58 (69.0%) respondents, use of personal protective equipment (PPE) mentioned by 56 (66.7%), handwashing mentioned by 51 (60.7%), and the safe disposal of clinical waste mentioned by 23 (27.4%) respondents. The components of IPC which the participants reported to have been trained on are presented in Figure 2.

On assessment of IPC knowledge, 92 (63.0%) of the respondents had a good knowledge score of IPC. One hundred and two (69.9%) knew how to prepare the different solutions used for disinfection, 76 (52.0%) knew the importance of waste segregation at the point of generation, and 53 (36.3%) mentioned at least three components of IPC standard precautions. The knowledge attributes of the respondents on IPC at the CTC and ORPs in Kadoma are presented in Table 2.

Availability of IPC Resources at the Cholera Treatment Facilities

The CTC was stocked with key supplies, including high test hypochlorite (HTH), gloves, aprons, buckets, soap, ringer’s lactate, doxycycline, water guard, brooms, mops, and refuse receptacles, which could last for more than 14 days. The ORPs had resources for IPC implementation such as HTH, aprons, oral rehydration salts (ORS), and water guard, with less than 7 days of supply remaining. Essential items like soap and refuse receptacles were not available at the ORPs. The resources for implementation of IPC available at the CTC and ORPs in Kadoma are presented in Table 3.

Interviews with the IPC focal person and camp coordinators at the Cholera Treatment Center highlighted that as the cholera outbreak intensified number of cases attended to at both the CTC and ORPs increased. Consequently, the supply needs for PPE also increased, suggesting the need to adjust supplies to meet the rising demand as the outbreak progressed.

One camp coordinator said: “Currently, our stock has improved, and partners have supported us with a great deal of IPC resources. However, the number of cases attended to at ORPs, and the CTC is increasing, thereby requiring more resources for IPC if we are to truly protect our workers. There is a need to increase our supplies both at the CTC and ORPs so that we protect the workers and the patients they are assisting”.

Adherence to Infection Prevention and Control Protocols and Procedures

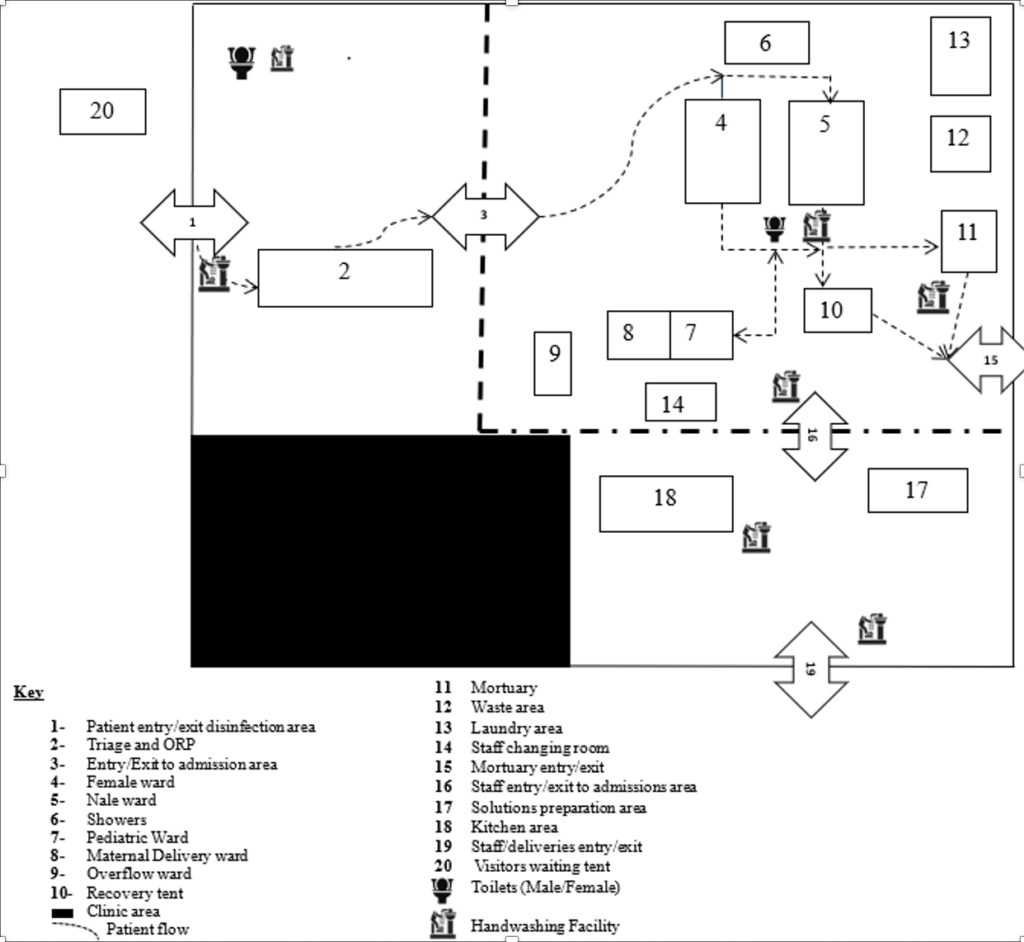

Layout of CTC and Patient Flow

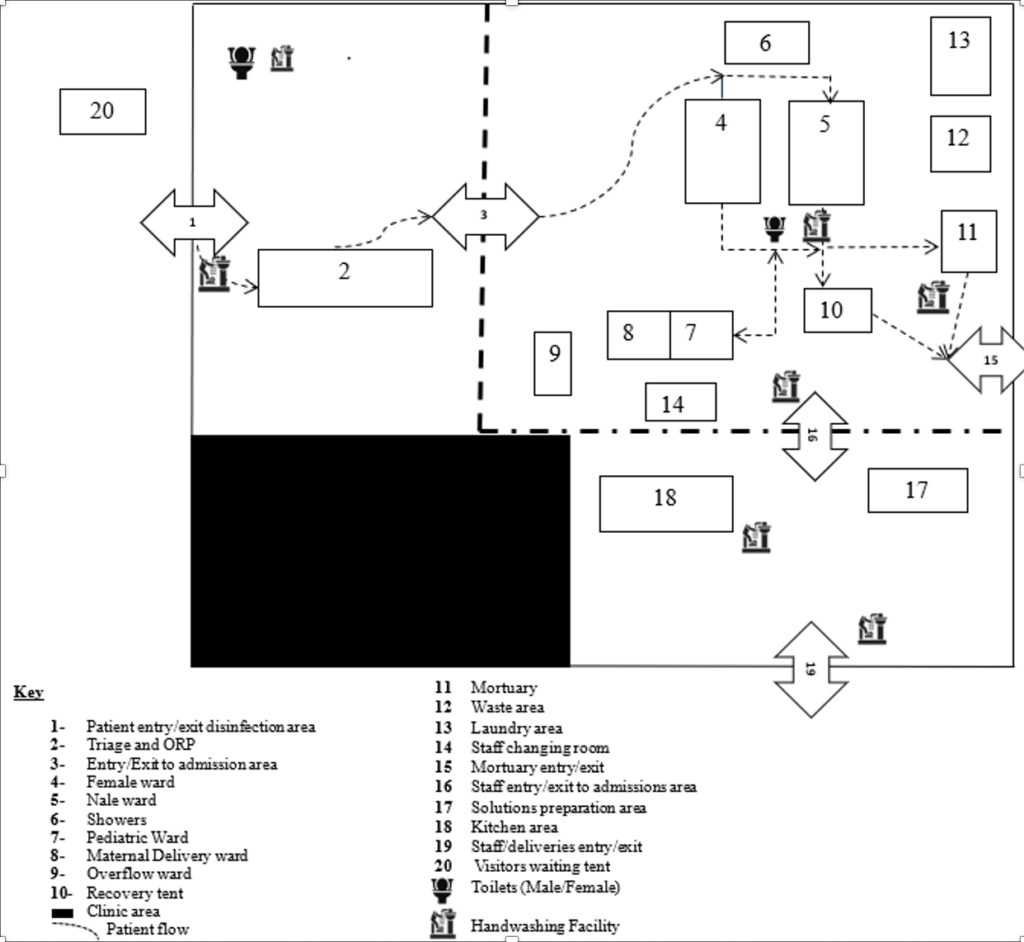

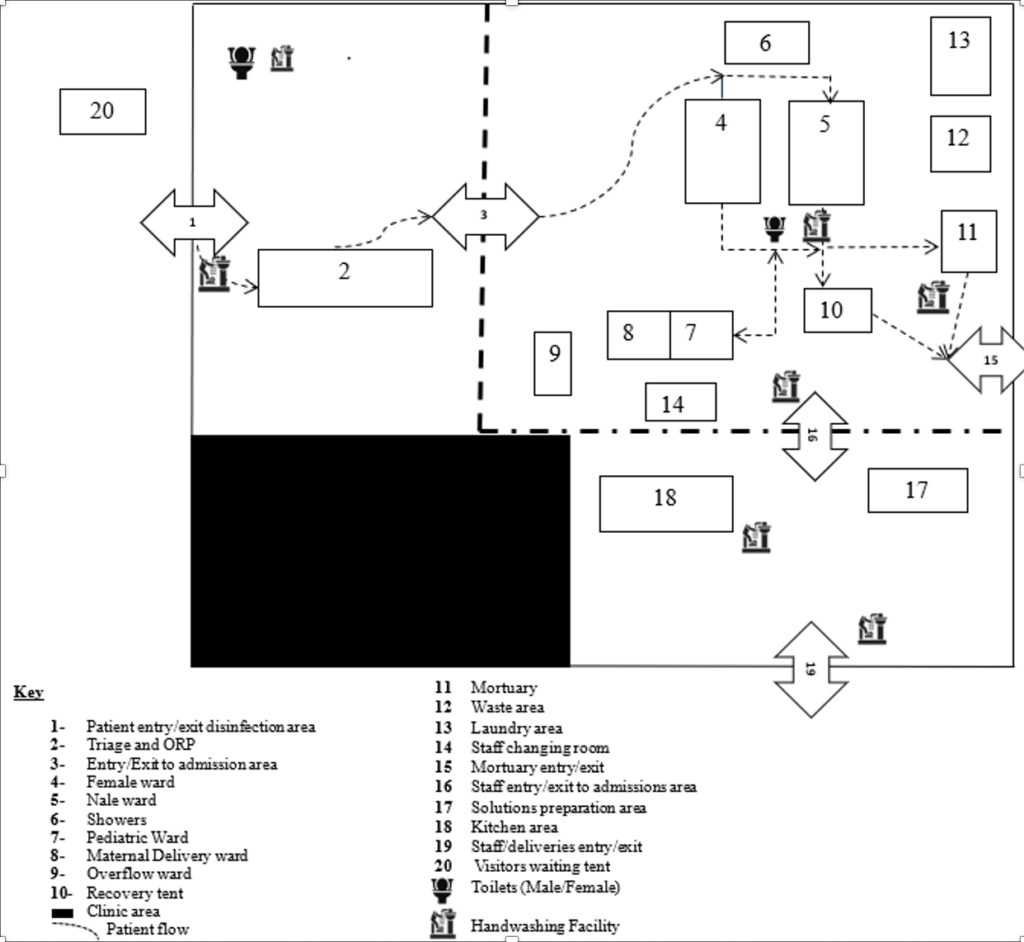

The CTC and ORPs were designed for easy access, with clearly marked entry and exit points, and surrounded by barricade lines to restrict unauthorized access. The CTC was set up with sufficient spaces for various functions including an observation area, admission area, recovery zone, neutral zone, laundry, waste management, mortuary, showers, and bathing units. The entire structure was fenced to restrict access and personnel stationed at each entry and exit point to control patient flow. Wards were separated by gender, with each patient allocated 4m² of space in the ward. The floors of the structure were covered with plastic sheets for ease of cleaning. A kitchen was set up within the CTC to prepare food for patients and staff. All the different zones within the CTC were clearly marked. The CTC layout and patient flow is presented in Figure 3.

Quote from a camp coordinator: “The layout of the CTC follows the national guidelines. We have clear entry and exit points, and we ensure that all staff follow the designated patient flow to minimize cross-contamination. However, at times, some staff bypass the system, which poses a challenge in maintaining strict infection control”

Availability of Standard Operating Procedures for Infection Prevention and Control

The National infection prevention and control guidelines for cholera were not available at the CTC and ORPs in Kadoma. Additionally, the standard operating procedures (SOPs) for various IPC components developed by Kadoma City were not available at the time of the evaluation. However, posters with signage for handwashing, preparation of disinfectants, hand hygiene, and preparation of ORS were displayed in all admission wards at the CTC and at workstations at all oral rehydration points.

Availability of Water at the Cholera Treatment Facilities

Out of the six facilities (1 CTC and 5 ORPs) assessed during the evaluation, five (83%) reported always having water available for drinking, preparation of ORS, and cleaning in all critical locations. The CTC was established at a local clinic that already had a constant supply of clean water from a borehole. At the ORPs, four used communal boreholes as their sources of water, and one used well water from a nearby household. the CTC) reported always having water for consumption with a turbidity of less than 5 NTU and a chlorine residual of at least 0.5 mg/L. Free residual chlorine for drinking water was always tested at one facility (the CTC), whereas no testing was done at the ORPs.

Availability of Hand Washing Stations at the Cholera Treatment Facilities

An assessment of the availability of handwashing facilities at the CTC and ORPs revealed that all entry and exit points (4/4) at the CTC had handwashing facilities. Similarly, all ORPs (5/5) in Kadoma had handwashing facilities at their entrances and exits. All four toilets at the CTC had handwashing facilities at their entrances; however, only one ORP had a handwashing facility at its toilet entrance. No handwashing facilities were observed at the laundry and waste management area of the CTC. The critical areas with handwashing facilities at the CTC and ORPs in Kadoma City are presented in Table 4.

Observations were made at the CTC to assess the hand hygiene practices of health workers as they performed their daily duties without their knowledge. A total of five auxiliary staff, one nurse aid and two registered general nurses were observed. All observed health workers who had contact with patients and their linen washed their hands after every contact in the admission areas. However, those who did not have any contact with patients did not wash their hands at the handwashing stations at exit points upon leaving the cholera treatment center.

Availability of Toilets at the Cholera Treatment Facilities

Of the six facilities assessed during the evaluation, all had usable toilets for every 50 patients, with one male and one female toilet per facility, except for the CTC, which had two male and two female toilets. Only the CTC had separate toilets for staff use. All toilets at the CTC and ORPs were regularly disinfected with a 0.2% chlorine solution on the slabs and floors. The availability of toilets and adherence to IPC practices at the CTC and ORPs is presented in Table 4.

Waste Management at the Cholera Treatment Facilities

All cholera treatment facilities had safe methods for disposing of feces and vomit. At the CTC, feces and vomit were disinfected with a 2% chlorine solution, which was poured into the buckets used for collection. These buckets were then emptied into a feces and vomitus tank on-site, which was emptied when three-quarters full at a designated pit offsite. At the ORPs, vomit and feces were disinfected using a 2% chlorine solution poured into the buckets used for collection and then emptied into the pits of latrines on-site, which were dislodged after filling up. Solid waste was segregated at the point of generation at all five facilities. Only the CTC had a fenced waste area, preventing access by scavengers. The waste management practices at the CTC and ORPs are presented in Table 5.

Quote from a healthcare worker: “We follow standard IPC protocols for waste disposal. Contaminated waste is segregated at the point of generation and disposed of in designated pits. However, at the ORPs, we face challenges with improper waste disposal due to limited space and lack of fenced waste areas, which sometimes attracts scavengers.”

Mortuary and Handling of Corpses at the Cholera Treatment Center

A mortuary was set up at the cholera treatment center, with adequate space, ventilation openings and located close to an exit point as shown in Figure 3. A handwashing station was placed within 5 meters of the mortuary, and the floors were regularly disinfected with a 0.2% chlorine solution. Corpses were disinfected with a 2% chlorine solution, and all orifices were plugged with cotton soaked in 2% chlorine solution before burial. The preparation of corpses was carried out by trained personnel only.

Quote from the IPC focal person: “When a patient succumbs to cholera, the body is immediately disinfected using a 2% chlorine solution. The corpse is then placed in a body bag and placed in a designated storage area within the mortuary. However, we do not have specialized body storage facilities, so burials are done promptly. The city health department coordinates transportation using a dedicated vehicle for cholera-related deaths. Burial follows public health guidelines, with supervised grave preparation and family members given PPE to prevent contamination during burial.”

Food Preparation and Food Handling at the Cholera Treatment Center

The cholera treatment center had a designated area for food preparation as highlighted in Figure 3. A handwashing facility was available near the kitchen area. Eating and cooking utensils were washed with detergent and a 0.2% chlorine solution. All leftover food was disposed of in the waste area at the CTC; no leftover food was taken outside the CTC.

Vector Control at the Cholera Treatment Center

Vector control measures were strengthened by frequently disinfecting and cleaning surfaces with a 0.2% chlorine solution. Solid waste was disposed of into two separate pits: one for biodegradable waste, which was buried with sand to prevent vector breeding, and the other for non-biodegradable waste, which was then burned. Insecticides and fly traps were used in the canteen area to control flies.

Barriers to Infection Prevention and Control

Of the 146 respondents, 78 (53.4%) perceived staff shortages as a barrier to effective IPC implementation at the CTC and ORPs. Additionally, 68 (46.6%) cited inadequate IPC resources, 48 (32.9%) mentioned lack of training, and 17 (11.6%) perceived the lack of SOPs as barriers to effective IPC implementation. The most common suggestions for improving IPC implementation included regular IPC training 83 (56.8%), having SOPs and job aids 77(52.7%), improving the availability of PPE and disinfectants 68 (47.0%), and conducting regular support and supervisory visits 30(20.5%).

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the implementation of infection prevention and control measures at cholera treatment facilities in Kadoma. A higher proportion of those interviewed were auxiliary staff and community health workers, who played a vital role in outbreak response. Their involvement in daily tasks, such as environmental cleaning, laundry and other supportive tasks, highlighted the importance of ensuring that they were well-trained in IPC protocols to prevent the spread of cholera within the facilities and the wider community.

Knowledge of infection prevention and control measures among the respondents was high. This was likely due to a higher proportion having received training on various components of IPC, including the preparation of disinfectants, hand washing, and safe disposal of clinical waste. Similar findings were reported in Kenya, where most participants had good knowledge of IPC attributed to previous training [22]. Knowledge of IPC practices among healthcare workers directly impacts the effectiveness of IPC implementation. The World Health Organization recommends training as a core component for effective IPC programs [23]. When healthcare workers are adequately trained, their overall knowledge improves, thereby contributing to compliance with IPC standard precautions [24,25].

The cholera treatment center in Kadoma was noted to be adequately stocked with resources for implementing IPC, with most resources estimated to last more than two weeks. This contrasts with findings from a study that was done in Yemen, where inadequate resources for IPC implementation, such as bins, cleaning equipment, and personal protective equipment (PPE), were noted at diarrhea treatment center [26]. Sufficient resources are critical for the long-term effectiveness and sustainability of IPC practices. Cholera treatment centers are expected to be safe and operate according to the highest safety standards to protect workers, patients, and the community from cholera [16,17,27]. The adequate resourcing of the CTC in Kadoma supported this, ensuring that IPC measures were consistently maintained and reducing the risk of cholera transmission.

In contrast, the oral rehydration points were not adequately stocked with resources for IPC implementation. Most supplies were estimated to last no more than seven days. This was probably due to the unavailability of proper stock management systems at ORPs, as most were temporary partner-supported structures, operated by community health workers who were not trained in stock management. This shortage of IPC resources at critical facilities like ORPs was a cause for concern, as it might have led to improper practices, increasing the risk for workers and patients attended to at these facilities.

In our study we noted that the layout and patient flow of the CTC and ORPs in Kadoma were designed for efficient access, ensuring that IPC measures were adhered to, reducing cross-contamination. The layout of these facilities aligned with recommendations for setting up CTCs and ORPs from the Zimbabwe cholera control guidelines 4th edition and the global taskforce on cholera control (GTFCC) [17]. Hand washing facilities were available at the CTC and ORPs and placed in all critical areas except for the entrances of latrines of three oral rehydration points. When observations were made on hand-washing practices among the workers, compliance was high. Similar findings were reported by Abuosi et. al. (2020) in Ghana where compliance with hand hygiene was moderately high among healthcare workers [28]. The high compliance rate might have been due to the consistent availability of handwashing facilities at all critical areas at the CTC and ORPs.

The perceived barriers to effective IPC implementation mentioned by respondents included shortage of staff, IPC resources, and lack of training. Similar findings were reported in Nigeria and Malawi, where a shortage of staff, IPC resources, and lack of training were the barriers mentioned by healthcare workers that affected IPC implementation in healthcare settings [3,29]. Ensuring that healthcare facilities are adequately staffed and equipped with necessary IPC resources is essential for maintaining high standards of infection control [1]. Regular training sessions can enhance the knowledge and skills of healthcare workers, enabling them to implement IPC protocols effectively.

Limitations

Our study was not without limitations. The potential for the Hawthorne effect existed, as participants may have modified their behavior due to awareness of being observed. This could have led to behaviors that were not representative of their typical daily practices. To minimize this bias, we made efforts to observe participants discreetly, without their knowledge. Also, the final sample size (146 participants) was lower than the calculated sample size of 165, which may have affected the study’s power and the generalizability of findings. Despite this, the sample still captured a diverse range of healthcare workers involved in cholera response, ensuring representation across different cadres.

Conclusion

Most respondents were auxiliary staff and community health workers who had worked at the CTC and ORPs for an average of 106 and 49 days, respectively. The majority had received IPC training and demonstrated adequate knowledge. The layout and patient flow at both facilities adhered to GTFCC and Zimbabwe Cholera Control Guidelines (4th edition), supporting adherence to IPC measures. While the CTC was well-stocked with IPC resources sufficient for over 14 days, ORPs faced shortages in key supplies such as HTH, aprons, soap, and water guards, with available stock lasting less than 7 days. Standard operating procedures for IPC were lacking, and healthcare workers were relying on poster signage for guidance. Perceived barriers to effective IPC implementation included staff shortages, resource gaps, and insufficient training.

Based on the findings from this evaluation, to improve IPC implementation at cholera treatment facilities in Kadoma, we recommended further training for healthcare workers and community health workers on critical IPC practices, including stock management. Kadoma City Council should also ensure a consistent supply chain for essential IPC resources at the cholera treatment center and oral rehydration points to prevent understocking. Additionally, the city health department should develop and distribute standardized operating procedures (SOPs) for IPC across all facilities to ensure consistency of practices.

What is already known about the topic

- Inadequate IPC practices during outbreaks can exacerbate disease transmission within healthcare facilities and the broader community

- It is common for HCWs to have good knowledge of IPC but this does not usually translate into compliance with IPC protocols

What this study adds

- This study provides local evidence from Kadoma City, Zimbabwe, on the implementation status of IPC measures at cholera treatment facilities (CTC and ORPs) during a cholera outbreak

- The evaluation identified specific IPC components that were inadequately implemented, particularly at ORPs. These included waste management, availability of PPE, hand hygiene infrastructure, and triage systems, which are essential in preventing healthcare-associated cholera transmission

- Operational challenges such as delayed supplies, limited training, and weak supervision hindered IPC implementation

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all workers of Kadoma City Council who participated in the study. Furthermore, we would like to express our sincere gratitude to the Department of Global Public Health and Family Medicine at University of Zimbabwe (UZ) and the Zimbabwe Field Epidemiology Training Program (ZimFETP) for the help they rendered to us during this project.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this study are those of the authors and are the product of professional research. It does not necessarily reflect the official position of any affiliated institution, funder or that of the publisher. The authors are responsible for this study’s findings and content shared.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from the Kadoma City Council.

Authors´ contributions

CM, DC, TJ, GS, AC, NTG, GM and MT were responsible for conceptualization of the study. CM, DC and MT were responsible for study protocol development, data collection, analysis of results and drafting of the manuscript. All authors reviewed, provided input and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable for the content and integrity of the article.

| Variable | CTC n, (%) | ORP n, (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 45 (30.8) | 3 (2.1) |

| Female | 83 (56.8) | 15 (10.3) |

| Designation | ||

| Auxillary Staff | 74 (50.7) | – |

| Community Health Worker | 18 (12.3) | 13 (8.9) |

| Nurse Aide | 9 (6.2) | – |

| Primary Care Nurse | 3 (2.1) | – |

| Registered General Nurse | 4 (2.7) | – |

| Mortician | 4 (2.7) | – |

| Environmental Health Practitioner | 7 (4.8) | – |

| Ambulance Driver | 4 (2.7) | – |

| Volunteer | 2 (1.4) | 5 (3.4) |

| Cook | 3 (2.1) | – |

| Median Age (Years) (Q1; Q3) | 46 (Q1=41; Q3=53) | 49 (Q1=28; Q3=53) |

| Median days working at treatment facilities | 106 (Q1=82; Q3=109) | 49 (Q1=16; Q3=106) |

| Attribute | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Received IPC Training | 84 (57.5) |

| Mentioned at least three components of IPC standard precautions | 53 (36.3) |

| Knew how to prepare disinfectants | 102 (69.9) |

| Knew the importance of waste segregation at the point of generation | 76 (52.0) |

| Overall, Knowledge Score | |

| Good | 92 (63.0) |

| Poor | 54 (37.0) |

| Item | CTC | ORPs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Estimated Days of Supply Left | Yes | No | Estimated Days of Supply Left | |

| HTH | ✓ | >14 | ✓ | <7 | ||

| Gloves | ✓ | >14 | ✓ | >14 | ||

| Aprons | ✓ | >14 | ✓ | <7 | ||

| ORS | ✓ | 7-14 | ✓ | <7 | ||

| Buckets | ✓ | >14 | ✓ | >14 | ||

| Soap | ✓ | >14 | ✓ | |||

| Ringer Lactate | ✓ | >14 | n/a | |||

| Catheter IV | ✓ | 7-14 | n/a | |||

| Doxycycline | ✓ | >14 | n/a | |||

| Azithromycin | ✓ | <7 | n/a | |||

| Water Guard | ✓ | >14 | ✓ | <7 | ||

| Brooms and Mops | ✓ | >14 | ✓ | |||

| Bins Refuse Receptacles | ✓ | >14 | ✓ | |||

| Doctor Trained in IPC | ✓ | – | n/a | |||

| Nurse Trained in IPC | ✓ | – | n/a | |||

| CHW Trained in IPC | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ||

| Trained logistics, supplies and stock person | ✓ | – | n/a | – | ||

| IPC Component | CTC | ORPs |

|---|---|---|

| Hand Washing Facility | ||

| Handwashing facilities with soap available at points of entry and exit | 4/4 | 5/5 |

| Handwashing facilities with soap available at latrines | 4/4 | 1/5 |

| Handwashing facility with soap available at the kitchen | 1/1 | – |

| Handwashing facility with soap available at the laundry area | 0/1 | – |

| Handwashing facility with soap available at the waste management area | 0/1 | – |

| Handwashing facility with soap available at the mortuary | 1/1 | – |

| Foot spraying/maintained footbaths available at entry and exit points | 4/4 | 5/5 |

| Handwashing facilities with soap available in treatment wards | 3/3 | – |

| Toilets | ||

| The facility has 1 usable latrine per 50 patients (minimum 2 latrines, male/female) | 1/1 | 5/5 |

| Facility has at least 2 latrines (male/female) for staff | 1/1 | 0/5 |

| Toilets are dislodged after filling up | 1/1 | 5/5 |

| Toilets are disinfected regularly with 0.2% chlorine solution (floors and slabs) | 1/1 | 5/5 |

| Waste Management | CTC | ORPs |

|---|---|---|

| Facility has a designated pit or other safe methods for disposing the feces and vomit of cases | 1/1 | 5/5 |

| Solid waste is segregated at point of generation | 1/1 | 5/5 |

| Color coded bin liners used for segregation of waste | 0/1 | 5/5 |

| A fenced waste zone is available at the facility and scavengers have no access to the waste zone | 1/1 | 0/5 |

| 2% chlorine solution poured into buckets used for collecting vomit and feces | 1/1 | 5/5 |

References

- Ministry of Health and Child Care (Zimbabwe). National Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines [Internet]. Harare (Zimbabwe): Ministry of Health and Child Care; 2013 May 1 [cited 2025 Apr 7]. Available from: http://zdhr.uz.ac.zw/xmlui/handle/123456789/701.

- Assiri AM, Choudhry AJ, Alsaleh SS, Alanazi KH, Alsaleh SS. Evaluation of infection prevention and control programmes (IPC), and assessment tools for IPC-programmes at MOH-health facilities in Saudi Arabia. Open Journal of Nursing [Internet]. 2014 Jun [cited 2025 Apr 7];4(7):483–92. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=46633. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojn.2014.47051.

- Falana ROA, Ogidan OC, Fajemilehin BR. Barriers to infection prevention and control implementation in selected healthcare facilities in Nigeria. Infectious Diseases Now [Internet]. 2024 Feb 22 [version of record 2024 Feb 25; cited 2025 Apr 7];54(3):104877. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2669991924000320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idnow.2024.104877.

- Houghton C, Meskell P, Delaney H, Smalle M, Glenton C, Booth A, Chan XHS, Devane D, Biesty LM. Barriers and facilitators to healthcare workers’ adherence with infection prevention and control (IPC) guidelines for respiratory infectious diseases: a rapid qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2020 Apr 21 [cited 2025 Apr 7];2020(8):CD013582. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD013582. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013582.

- Haque M, Sartelli M, McKimm J, Abu Bakar M. Health care-associated infections – an overview. Infect Drug Resist [Internet]. 2018 Nov 15 [cited 2025 Apr 7];11:2321–33. Available from: https://www.dovepress.com/health-care-associated-infections-an-overview-peer-reviewed-fulltext-article-IDR. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S177247.

- Tomczyk S, Storr J, Kilpatrick C, Allegranzi B. Infection prevention and control (IPC) implementation in low-resource settings: a qualitative analysis. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control [Internet]. 2021 Jul 31 [cited 2025 Apr 7];10(1):113. Available from: https://aricjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13756-021-00962-3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-021-00962-3.

- Ridge LJ, Stimpfel AW, Klar RT, Dickson VV, Squires AP. Infection prevention and control in Liberia 5 years after Ebola: a case study. Workplace Health Saf [Internet]. 2021 Apr 13 [cited 2025 Apr 7];69(6):242–51. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2165079921998076. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165079921998076.

- Margao S, Fofanah WD, Thekkur P, Kallon C, Ngauja RE, Kamara IF, Kamara RZ, Tengbe SM, Moiwo M, Musoke R, Fullah M, Kanu JS, Lakoh S, Kpagoi SSTK, Kamara KN, Thomas F, Mannah MT, Katawera V, Zachariah R. Improvement in infection prevention and control performance following operational research in Sierra Leone: a before (2021) and after (2023) study. TropicalMed [Internet]. 2023 Jul 23 [cited 2025 Apr 7];8(7):376. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2414-6366/8/7/376. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8070376.

- Kateule E, Ngosa W, Mfume F, Shimangwala C, Msisika S, Choonga S, et al. An assessment of the response to Cholera outbreak in Lusaka district, Zambia – October 2023 – February 2024. JIEPH [Internet]. 2024 Nov 19 [cited 2025 Apr 7];7:53. Available from: https://www.afenet-journal.net/content/article/7/53/full/.

- Ng’ambi D, O’Byrne T, Jingini E, Chadwala H, Musopole O, Kamchedzera W, Tancred T, Feasey N. An assessment of infection prevention and control implementation in Malawian hospitals using the WHO Infection Prevention and Control Assessment Framework (IPCAF) tool. Infection Prevention in Practice [Internet]. 2024 Aug 22 [version of record 2024 Aug 29; cited 2025 Apr 7];6(4):100388. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2590088924000520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infpip.2024.100388.

- Magadze TA, Nkhwashu TE, Moloko SM, Chetty D. The impediments of implementing infection prevention control in public hospitals: nurses’ perspectives. Health SA Gesondheid [Internet]. 2022 Nov 11 [cited 2025 Apr 7];27:a2033. Available from: http://www.hsag.co.za/index.php/hsag/article/view/2033. https://doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v27i0.2033. Download PDF to view full text.

- Emmanuel G, Tirivanhu ZS, Gerald S, Notion GT, Juru T, Chiwanda S, Mufuta T. Evaluation of infection, prevention and control program in Goromonzi District, Zimbabwe, 2018: a process outcome evaluation [Internet]. 2019 Dec 6 [cited 2025 Apr 7]. Available from: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-8875/v1. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.2.18251/v1.

- Olatunji G, Kokori E, Moradeyo A, Olatunji D, Ajibola F, Otolorin O, Aderinto N. A perspective on the 2023 cholera outbreaks in Zimbabwe: implications, response strategies, and policy recommendations. J Epidemiol Glob Health [Internet]. 2023 Nov 27 [cited 2025 Apr 7];14(1):243–8. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s44197-023-00165-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44197-023-00165-6.

- Marumure J, Nyila MA. Cholera outbreaks in Zimbabwe: an in‐depth analysis of drivers, constraints and reimagining the use of medicinal plants. Huang Z, editor. Journal of Tropical Medicine [Internet]. 2024 Nov 21 [cited 2025 Apr 7];2024(1):1981991. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/jotm/1981991. https://doi.org/10.1155/jotm/1981991.

- Mashe T, Chaibva BV, Nair P, Sani KA, Jallow M, Tarupiwa A, Goredema A, Munyanyi M, Chimusoro A, Mpala N, Masunda KPE, Duri C, Chonzi P, Phiri I. Descriptive epidemiology of the cholera outbreak in Zimbabwe 2018–2019: role of multi-sectorial approach in cholera epidemic control. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2023 Jan 30 [cited 2025 Apr 7];13(1):e059134. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059134. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059134.

- Olson D, Fesselet JF, Grouzard V. Management of a cholera epidemic: practical guide for doctors, nurses, laboratory technicians, medical auxiliaries, water and sanitation specialists and logisticians [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): Médecins Sans Frontières; 2018 [cited 2025 Apr 7]; 282 p. Available from: https://medicalguidelines.msf.org/en/viewport/CHOL/english/management-of-a-cholera-epidemic-23444438.html. Download PDF to view full text.

- Global Taskforce on Cholera Control (GTCC). Cholera outbreak response field manual [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): GTCC; 2019 Oct [cited 2025 Apr 7]; 128 p. Available from: https://www.gtfcc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/gtfcc-cholera-outbreak-response-field-manual.pdf. Download PDF to view full text.

- WHO. Guidelines on core components of infection prevention and control programmes at the national and acute health care facility level [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2016 Nov 1 [cited 2025 Apr 7]; 90 p. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/251730/9789241549929-eng.pdf?sequence=1. Download PDF to view full text.

- Zibanayi C, Munemo C, Pasi N, Tengawarima S, Moyo S, Sunganai Charimari L, Ohene SA, Chirundu D. Prevention and response to sexual exploitation and abuse (PRSEA) in emergencies: beneficiary experiences from a cholera outbreak response in Kadoma City, Zimbabwe, 2024. IJRSI [Internet]. 2024 Dec 27 [cited 2025 Apr 7];11(12):35–48. Available from: https://rsisinternational.org/journals/ijrsi/articles/prevention-and-response-to-sexual-exploitation-and-abuse-prsea-in-emergencies-beneficiary-experiences-from-a-cholera-outbreak-response-in-kadoma-city-zimbabwe-2024/. https://doi.org/10.51244/IJRSI.2024.11120004. Download PDF to view full text.

- WHO. Framework and toolkit for infection prevention and control in outbreak preparedness, readiness and response at the national level [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2021 Dec 14 [cited 2025 Apr 7]; 84 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240032729. Download PDF to view full text.

- Karunamoorthi AK. Guideline for conducting a knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) study. AECS Illumination [Internet]. 2004 Mar [cited 2025 Apr 8];4(1):7–9. Available from: https://v2020eresource.org/content/files/guideline_kap_jan_mar04.pdf. Download PDF to view full text.

- Gichuhi AW. Health care workers’ adherence to infection prevention practices and control measures: a case of a level four district hospital in Kenya. AJNS [Internet]. 2015 Mar 21 [cited 2025 Apr 9];4(2):39–44. Available from: http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/journal/paperinfo.aspx?journalid=152&doi=10.11648/j.ajns.20150402.13. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajns.20150402.13.

- WHO. Guidelines on core components of infection prevention and control programmes at the national and acute health care facility level [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2016 [cited 2025 Apr 9]; 90 p. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/251730. Download PDF to view full text.

- Geberemariyam BS, Donka GM, Wordofa B. Assessment of knowledge and practices of healthcare workers towards infection prevention and associated factors in healthcare facilities of West Arsi District, Southeast Ethiopia: a facility-based cross-sectional study. Arch Public Health [Internet]. 2018 Nov 12 [cited 2025 Apr 9];76(1):69. Available from: https://archpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13690-018-0314-0. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-018-0314-0.

- Al-Faouri I, Okour SH, Alakour NA, Alrabadi N. Knowledge and compliance with standard precautions among registered nurses: a cross-sectional study. Annals of Medicine and Surgery [Internet]. 2021 Jan 29 [version of record 2021 Feb 2; cited 2025 Apr 9];62:419–24. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2049080121000595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2021.01.058.

- Ogaili MAO, Al-gunaid EA, Al-Shamahy HA, Jaadan BM. Survey of safety practices in diarrheal treatment centers: cholera treatment centers in Yemen. Universal Journal of Pharmaceutical Research [Internet]. 2020 Sep 15 [cited 2025 Apr 9];5(4):6–10. Available from: https://ujpronline.com/index.php/journal/article/view/432. http://dx.doi.org/10.22270/ujpr.v5i4.432. Download PDF to view full text.

- MSF. Management of a cholera epidemic [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): MSF; 2018. 6.1 Cholera treatment centres (CTC) [cited 2025 Apr 9]; [about 13 screens]. Available from: https://medicalguidelines.msf.org/en/viewport/CHOL/english/6-1-cholera-treatment-centres-ctc-25296944.html.

- Abuosi AA, Akoriyea SK, Ntow-Kummi G, Akanuwe J, Abor PA, Daniels AA, Alhassan RK. Hand hygiene compliance among healthcare workers in Ghana’s health care institutions: an observational study. Journal of Patient Safety and Risk Management [Internet]. 2020 Sep 30 [cited 2025 Apr 9];25(5):177–86. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2516043520958579. https://doi.org/10.1177/2516043520958579. Subscription or purchase required to view full text.

- Tu R, Elling H, Behnke N, Tseka JM, Kafanikhale H, Mofolo I, Hoffman I, Cronk R. A qualitative study of barriers and facilitators to adequate environmental health conditions and infection control for healthcare workers in Malawi. H2Open Journal [Internet]. 2022 Jan 6 [cited 2025 Apr 9];5(1):11–25. Available from: https://iwaponline.com/h2open/article/5/1/11/86224/A-qualitative-study-of-barriers-and-facilitators. https://doi.org/10.2166/h2oj.2022.139.

Menu, Tables and Figures

Navigate this article

Tables

| Variable | CTC n, (%) | ORP n, (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 45 (30.8) | 3 (2.1) |

| Female | 83 (56.8) | 15 (10.3) |

| Designation | ||

| Auxillary Staff | 74 (50.7) | – |

| Community Health Worker | 18 (12.3) | 13 (8.9) |

| Nurse Aide | 9 (6.2) | – |

| Primary Care Nurse | 3 (2.1) | – |

| Registered General Nurse | 4 (2.7) | – |

| Mortician | 4 (2.7) | – |

| Environmental Health Practitioner | 7 (4.8) | – |

| Ambulance Driver | 4 (2.7) | – |

| Volunteer | 2 (1.4) | 5 (3.4) |

| Cook | 3 (2.1) | – |

| Median Age (Years) (Q1; Q3) | 46 (Q1=41; Q3=53) | 49 (Q1=28; Q3=53) |

| Median days working at treatment facilities | 106 (Q1=82; Q3=109) | 49 (Q1=16; Q3=106) |

Table 1: Demographic Characteristics of Respondents, Kadoma City, 2024 (n=146)

| Attribute | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Received IPC Training | 84 (57.5) |

| Mentioned at least three components of IPC standard precautions | 53 (36.3) |

| Knew how to prepare disinfectants | 102 (69.9) |

| Knew the importance of waste segregation at the point of generation | 76 (52.0) |

| Overall, Knowledge Score | |

| Good | 92 (63.0) |

| Poor | 54 (37.0) |

Table 2: Knowledge of healthcare workers on IPC at CTC and ORPs in Kadoma, 2024 (n=146)

| Item | CTC | ORPs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Estimated Days of Supply Left | Yes | No | Estimated Days of Supply Left | |

| HTH | ✓ | >14 | ✓ | <7 | ||

| Gloves | ✓ | >14 | ✓ | >14 | ||

| Aprons | ✓ | >14 | ✓ | <7 | ||

| ORS | ✓ | 7-14 | ✓ | <7 | ||

| Buckets | ✓ | >14 | ✓ | >14 | ||

| Soap | ✓ | >14 | ✓ | |||

| Ringer Lactate | ✓ | >14 | n/a | |||

| Catheter IV | ✓ | 7-14 | n/a | |||

| Doxycycline | ✓ | >14 | n/a | |||

| Azithromycin | ✓ | <7 | n/a | |||

| Water Guard | ✓ | >14 | ✓ | <7 | ||

| Brooms and Mops | ✓ | >14 | ✓ | |||

| Bins Refuse Receptacles | ✓ | >14 | ✓ | |||

| Doctor Trained in IPC | ✓ | – | n/a | |||

| Nurse Trained in IPC | ✓ | – | n/a | |||

| CHW Trained in IPC | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ||

| Trained logistics, supplies and stock person | ✓ | – | n/a | – | ||

*n/a = not applicable

Table 3: IPC Program Resources Availability at CTC and ORPs in Kadoma, 2024

| IPC Component | CTC | ORPs |

|---|---|---|

| Hand Washing Facility | ||

| Handwashing facilities with soap available at points of entry and exit | 4/4 | 5/5 |

| Handwashing facilities with soap available at latrines | 4/4 | 1/5 |

| Handwashing facility with soap available at the kitchen | 1/1 | – |

| Handwashing facility with soap available at the laundry area | 0/1 | – |

| Handwashing facility with soap available at the waste management area | 0/1 | – |

| Handwashing facility with soap available at the mortuary | 1/1 | – |

| Foot spraying/maintained footbaths available at entry and exit points | 4/4 | 5/5 |

| Handwashing facilities with soap available in treatment wards | 3/3 | – |

| Toilets | ||

| The facility has 1 usable latrine per 50 patients (minimum 2 latrines, male/female) | 1/1 | 5/5 |

| Facility has at least 2 latrines (male/female) for staff | 1/1 | 0/5 |

| Toilets are dislodged after filling up | 1/1 | 5/5 |

| Toilets are disinfected regularly with 0.2% chlorine solution (floors and slabs) | 1/1 | 5/5 |

Table 4: Availability of Handwashing, Toilet Facilities and Waste Management Practices at the CTC and ORPs in Kadoma, 2024

| Waste Management | CTC | ORPs |

|---|---|---|

| Facility has a designated pit or other safe methods for disposing the feces and vomit of cases | 1/1 | 5/5 |

| Solid waste is segregated at point of generation | 1/1 | 5/5 |

| Color coded bin liners used for segregation of waste | 0/1 | 5/5 |

| A fenced waste zone is available at the facility and scavengers have no access to the waste zone | 1/1 | 0/5 |

| 2% chlorine solution poured into buckets used for collecting vomit and feces | 1/1 | 5/5 |

Table 5: Waste Management at the Cholera Treatment Facilities, Kadoma, 2024

Figures

Keywords

- Infection Prevention and Control

- Cholera Treatment Center

- Oral Rehydration Points