Research![]() | Volume 8, Article 32, 07 May 2025

| Volume 8, Article 32, 07 May 2025

Integration and utilization of traditional medicine in child healthcare to achieve universal health coverage: Caregivers perspectives

Irene Eseohe Akhigbe1,&, Cheryl Olabisi Jones1, Abubakarr Bailor Bah1, Nellie Valerie Tayo Bell1, Lannes Namusa Susan Kamara1, Ronita Désirée Cornelia Luke1, Ayeshatu Majagbae Mustapha1

1Department of Paediatrics, Ola During Children Hospital, University of Sierra Leone Teaching Hospital Complex, Freetown, Sierra Leone

&Corresponding author: Irene Eseohe Akhigbe, Department of Paediatrics, Ola During Children Hospital, University of Sierra Leone Teaching Hospital Complex, Freetown, Sierra Leone, Email address: drireney@yahoo.com

Received: 07 Dec 2024, Accepted: 29 Apr 2025, Published: 07 May 2025

Domain: Universal Health Coverage; Maternal and Child Health

Keywords: Traditional medicine; Integration; Universal health coverage

©Irene Eseohe Akhigbe et al Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Irene Eseohe Akhigbe et al Integration and utilization of traditional medicine in child healthcare to achieve universal health coverage: Caregivers perspectives. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8:32. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-24-02019

Abstract

Introduction

Since ancient times, plants have played various essential roles in human life, particularly as sources of food and medicine to treat disease in humans [1]. Plants are a fundamental part of traditional medicine (TM), which remains widely used across African societies for maintaining health and well-being [1]. The global recognition of TM was reinforced by the 1978 Alma Ata Conference Declaration, which advocated for primary healthcare access through traditional medicine [2]. This declaration emphasized a shift toward community-based healthcare, active involvement of local populations in health system management [2], and broader healthcare accessibility. Additionally, it provided an opportunity for governments and traditional healers to collaborate and establish policies supporting the formal integration of traditional medicine into disease prevention and treatment [3].

Incorporating traditional medicine into healthcare systems aligns with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals and the 2030 agenda of ensuring “no one is left behind,” particularly in attaining Universal Health Coverage (UHC) [4]. Research suggests that achieving UHC in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) would require integrating traditional health practitioners into formal healthcare structures [5]. Studies indicate that approximately 60% of SSA’s population resides in rural areas where orthodox medical services are scarce [6], and traditional medicine remains the main form of healthcare for an estimated 80–90% of the total population [7].

Several factors contribute to the continued dependence on traditional medicine in Africa, including cultural acceptance, affordability, and accessibility. In some cases, individuals turn to traditional remedies due to the unavailability or high cost of orthodox medicine [8]. Others seek traditional treatments for conditions that have not responded to orthodox medical approaches or are perceived as insufficient or unsafe [9]. Traditional medicine is also preferred for ailments believed to have spiritual origins [10] or those requiring holistic treatment methods. These considerations have led to discussions on integrating traditional and orthodox child healthcare to ensure safe, effective, and comprehensive medical services [11].

The World Health Organisation (WHO) Traditional Medicine Strategy 2014–2023 empowers healthcare leaders to create innovative solutions that enhance health outcomes and patient autonomy. Its primary objectives are to: assist Member States leverage traditional and complementary medicine’s (T&CM) potential for health and general wellness; whilst ensuring its safe and effective use through regulation of products, practices, and practitioners [12].

Although evidence suggests that traditional medicines are widely utilised, and their integration into healthcare practices could address various child health needs, there is limited data on healthcare users’ views regarding this integration. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the use of traditional medicine among caregivers of children, and to explore their perspectives on incorporating traditional medicine into child healthcare to achieve UHC.

Methods

Study design and population

A cross-sectional study design was utilised among caregivers of children admitted into the general paediatric wards at Ola During Children’s Hospital (ODCH), between May and June 2024.

Sample size computation and sampling technique

A non-probability convenience sampling method was used in this study. All caregivers of children who were admitted into the general wards during the study period were recruited based on their availability and willingness to participate in this study, as participation was voluntary. Children’s caregivers referred to any one person who was a guardian or a parent, either biologically or not, and had the authority to make healthcare decisions about the child’s health. Any participant who did not meet those criteria because they were underage (aged below 18 years) or could not provide the required information for the study including details on traditional medicine use in their child’s care, were excluded.

Study setting

This study was conducted at Ola During Children’s Hospital (ODCH), a government hospital located in the densely populated Eastern part of the Western Area Urban, Freetown, Sierra Leone. The hospital is a tertiary referral paediatric hospital and a part of the University of Sierra Leone Teaching Hospitals Complex. It has a 164 in-patient bed capacity and equipped with facilities for neonatal care, emergency room, high dependency unit, paediatric intensive care unit, oncology unit, therapeutic feeding center and two general wards.

Study tool

Data was collected with a semi-structured pre-designed and pretested questionnaire through face-to-face interviews by trained data collectors who are paediatric residents. The data collectors were responsible for the completeness and consistency of data at the site. The study tool comprised of three (3) sections: socio-demographic characteristics of caregivers; traditional medicine utilisation and conditions treated; and perspectives on integrating traditional medicine with conventional healthcare. We collected data on the respondents’ age, gender, tribe, marital status and other socio-demographic characteristics; perspectives on how commonly traditional medicines are used in the community and personal experience with use of these preparations in children. Those who admitted using traditional medicines in their children were asked about the name(s) of the preparations, how much was given, and who administers them to the children. Additionally, they were also asked about their perspectives regarding the integration of traditional and orthodox healthcare practices for child health.

Data Analysis

The data were compiled and descriptive statistics were generated using MS Excel. These were then presented as frequencies and percentages of the responses obtained.

Ethical considerations

Permission for the study was obtained from the management and the research committee of Ola During Children’s hospital (No number was formally assigned). Written informed consent (by signature or thumbprint) was obtained from those who volunteered.

Results

Demographic data

The study included 107 participants in total. The majority of caregivers were mothers (65; 60.7%), mostly between the ages of 25-28 years (41; 38.3%), with a M:F ratio of 1:4.1. Seventy-eight (72.9%) participants were Muslims; 60 (56.1%) were married; and most had secondary level of education. Temne 42(39.3%), Mende 22(20.6%), and Limba 12(11.2%) were the common tribes among study participants; most resided in the Western Urban Area district (55; 51.4%). The demographic characteristics of caregivers are shown in Table 1.

Utilisation of traditional medicine

The use of traditional medicine was described as a common practice in their communities (82; 76.6%), and over two-thirds of participants (76; 71%) had administered traditional medicine to children. The route of administration varied, but oral route was chiefly used 88.2%, with no specified amount in most cases (50.0%). It was common for grandmothers to administer these medicines (51.3%), these medicines were mostly administered to children between the ages of 1-5years (40.8%). The situation in which traditional medicines were used included preexisting common childhood illnesses (constipation, stomachache) as shown in Table 2. Among those with experience using traditional medicine in children, the majority (48; 63.2%) did not know the names of the traditional medicine used, but the others (28; 36.8%) mentioned “Gbangba” (Cassia sieberiana) as a common traditional medicine used within their communities.

Perspectives of caregivers on the integration of traditional medicine into Child healthcare

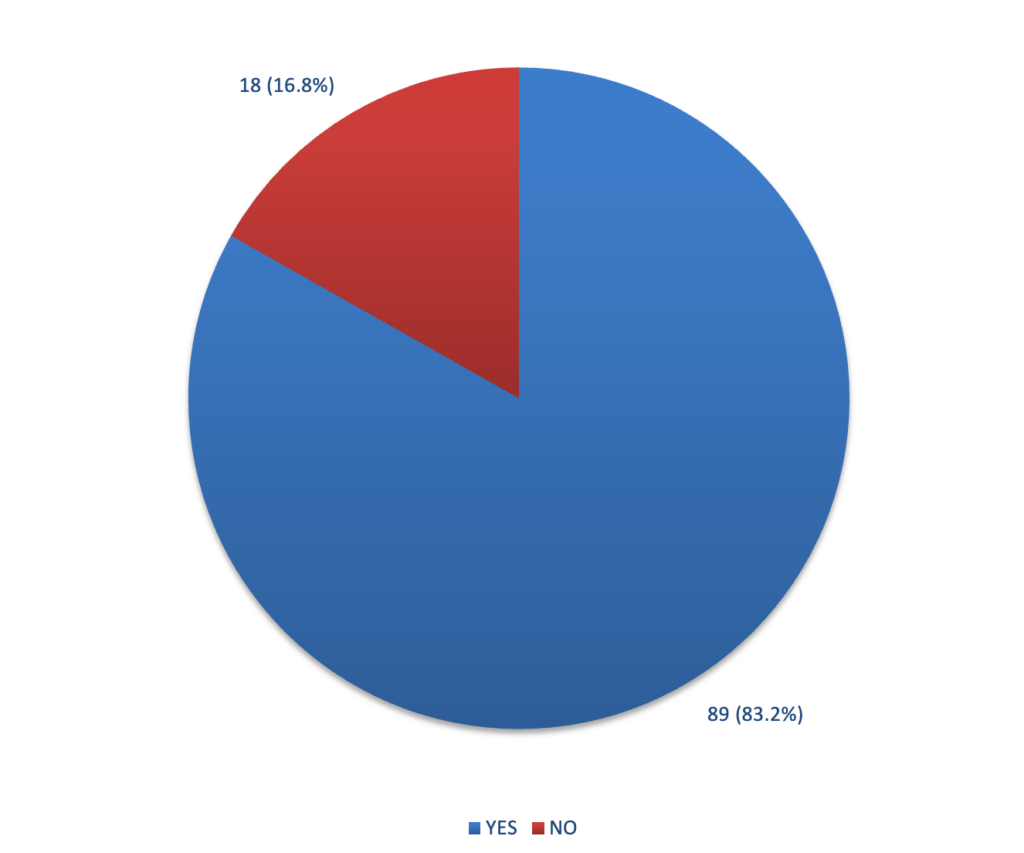

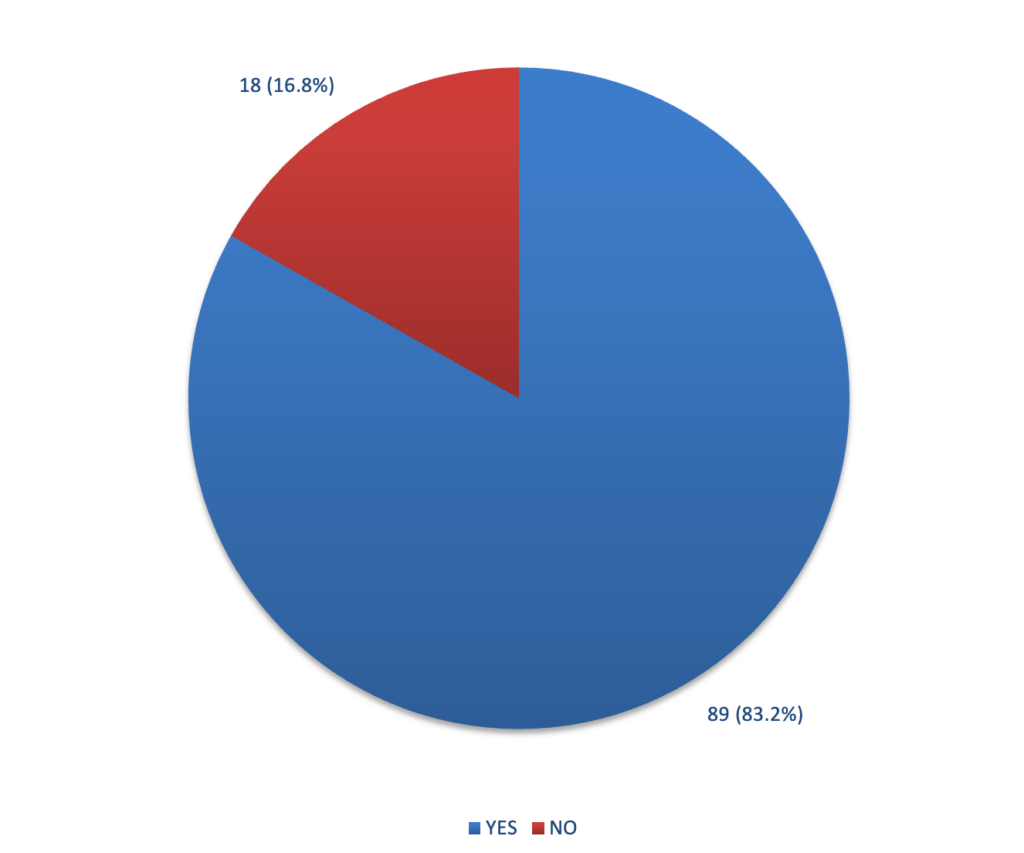

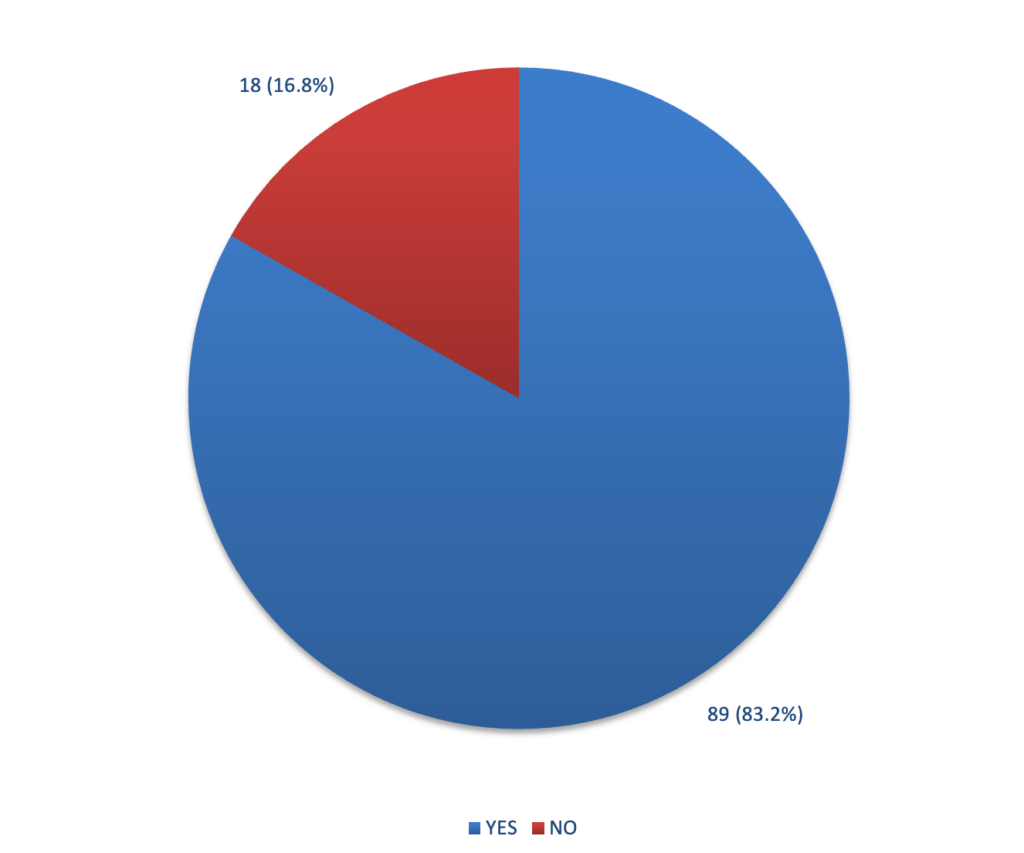

The majority of respondents (89; 83.2%) supported the integration of traditional medicine into the healthcare system (Figure 1). They believed that the integration might result in positive patient outcomes, as traditional medicines are culturally acceptable, readily available, effective, and can be used in certain illnesses perceived to have spiritual origins.

Barriers to the integration of traditional medicine into Child healthcare

On the contrary, those who opposed the integration argued that traditional medicines lacked dosages, frequency, and duration for each medication and the side effects of the medicines were unknown. They also considered it unsafe because the products were not scientifically investigated for efficacy and safety for human use.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the use of traditional medicines among children and to understand caregivers’ perspectives on integrating traditional and orthodox healthcare approaches in child health services. A major strength of the study was its setting within a health facility, focusing on individuals who sought orthodox healthcare services and had prior experience with traditional medicine. This ensured that their views on integrating traditional medicine into mainstream healthcare were relevant. The study provides valuable insights into the interaction between these two healthcare systems in a country where both are available but largely operate separately.

The study’s findings revealed that traditional medicines are widely utilised by most caregivers in Freetown communities, a trend consistent with studies conducted in Central and South Africa [13-15]. Despite the limited investment in traditional medicine development, its continued use is attributed to factors such as cultural acceptance, accessibility, affordability, and, in some cases, the unavailability and high cost of orthodox medicines, as observed in this study and other research [8,13,14].

A major concern highlighted in the study is the age of children receiving traditional remedies and the dosages administered. Given that infants have a lower tolerance for many medicinal preparations and peculiar pharmacokinetic responses to xenobiotics [16] raises safety concerns. Additionally, most caregivers lacked knowledge about the composition of the remedies, with their understanding being largely descriptive, as also reported by Dambisya et al [13]. These findings underscore the need for standardising traditional medicine practices through structured training programs aimed at educating and certifying traditional healers. Such initiatives should incorporate the perspectives of both traditional and orthodox medical practitioners to enhance collaboration, facilitate knowledge sharing, and increase trust in traditional medicine. This approach could support the documentation of existing and novel medicinal plants, the development of standardised treatment regimens, and the design of clinical trials to assess the efficacy and safety of traditional medicines [17].

While most caregivers favoured integration, some expressed concerns about potential risks associated with merging the two healthcare systems. Similar to research conducted in Botswana and South Africa [11,18], this study found that some participants questioned the scientific basis of traditional healthcare, viewing it as a potential obstacle to integration. This concern aligns with a review study [19] that highlighted biomedical practitioners’ apprehensions regarding patient safety and human rights when integrating traditional medicine. Such concerns are valid, as unethical practices among some traditional healers could pose risks to patient safety in the absence of proper regulation and policy [11]. However, rather than seeing this as a barrier, it presents an opportunity to introduce structured regulations that ensure the safe and ethical use of traditional medicines.

For instance, fostering collaboration between traditional and orthodox healthcare practitioners could facilitate the development of regulatory frameworks, ethical guidelines, and codes of conduct. Such policies could enhance cooperation, address unethical practices, and establish referral systems between the two health care systems. Additionally, these regulations could outline how traditional medicine products may be incorporated into orthodox healthcare, contribute to drug development, or help manage medication side effects. Strengthening collaboration could also aid scientists in distinguishing or, when necessary, excluding the spiritual elements of traditional medicine [17].

Given the significant healthcare gaps in many SSA communities and the complex factors shaping healthcare choices, traditional medicine holds untapped potential in improving access to acceptable and high-quality care. Investing in the accreditation of traditional medicine practices and addressing safety and ethical challenges would be a timely step toward bridging traditional and orthodox healthcare systems. Such efforts would also support the implementation of the WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy [12,20].

Limitations

This study was conducted in a health facility and findings obtained may not represent the perspectives of caregivers who only use traditional medicine. Additionally, in spite of our data quality control measures, results from this study could have been influenced due to interviewer’s bias and caregivers’ failure to recall pertinent information regarding previous use of traditional medicine.

Conclusion

This study revealed that most caregivers administer traditional medicines to children and support the integration of both health systems. However, traditional medicine remains unrecognised and excluded from the mainstream healthcare system. To ensure inclusive healthcare delivery, it is essential to decolonise the orthodox health system by acknowledging diverse communities, cultural backgrounds, and health-seeking behaviours.

In integrating traditional medicine into orthodox health systems to achieve UHC, policymakers should consider establishing regulatory frameworks to ensure the safe use of traditional medicine in child healthcare; foster stronger collaboration between traditional medicine practitioners and orthodox healthcare providers; raise awareness about the benefits and risks of traditional medicine to promote informed decision-making among caregivers; and advance research that focuses on longitudinal studies assessing the clinical outcomes of traditional medicine use in children, as well as interventions that effectively integrate traditional medicine into national health systems.

What is already known about the topic

- Traditional medicine still forms the backbone of rural health care, supporting an estimated 80–90% of the population.

- A large body of evidence indicates that 60% of the population in SSA lives in rural areas where conventional medical facilities are in short supply.

- Evidence exists showing that if UHC is to be achieved, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), traditional health practitioners should be incorporated into the healthcare systems.

What this study adds

- The study provides an insight into the phenomenon of integration between two systems of healthcare in a country where both are accessible but practicing in silos.

- Findings of this study showed that traditional medicines are widely used by the vast majority of caregivers living within communities in Freetown

- Although the majority of caregivers supported the integration, some were skeptical about the risks that may be involved with integrating the two healthcare systems.

Authors´ contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, or data analysis and interpretation, took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

| Demographic characteristics | Frequency | Percentages |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18-24 | 26 | 24.3 |

| 25-28 | 41 | 38.3 |

| 29-32 | 22 | 20.6 |

| >32 | 18 | 16.8 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 86 | 80.4 |

| Male | 21 | 19.6 |

| Religion | ||

| Muslim | 78 | 72.9 |

| Christian | 29 | 27.1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 39 | 36.4 |

| Married | 60 | 56.1 |

| Separated | 8 | 7.5 |

| Level of Education | ||

| No Formal education | 24 | 22.4 |

| Primary | 18 | 16.9 |

| Secondary | 39 | 36.4 |

| Tertiary | 26 | 24.3 |

| Tribe | ||

| Temne | 42 | 39.3 |

| Mende | 22 | 20.6 |

| Limba | 12 | 11.2 |

| Fula | 11 | 10.3 |

| Madingo | 9 | 8.4 |

| Krio | 7 | 6.5 |

| Soso | 4 | 3.7 |

| Residence | ||

| Western Urban | 55 | 51.4 |

| Western Rural | 42 | 39.3 |

| Other districts | 10 | 9.3 |

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Child’s Age | ||

| 0 – 28 days | 3 | 3.9 |

| 29 days – <1 year | 28 | 36.8 |

| 1 – 5 years | 31 | 40.8 |

| > 5 years | 14 | 18.5 |

| Route of administration* | ||

| Oral | 67 | 88.2 |

| Topical | 25 | 32.9 |

| Enema | 2 | 2.6 |

| Scarification | 7 | 9.2 |

| Amount administered* | ||

| Not specified | 38 | 50.0 |

| Spoonful | 31 | 40.8 |

| Cupful | 15 | 19.7 |

| Bottle | 9 | 11.8 |

| Medication given by:* | ||

| Grandmother | 39 | 51.3 |

| Mother | 32 | 42.1 |

| Father | 4 | 5.3 |

| Herbalist | 19 | 25.0 |

| Indications* | ||

| Constipation | 29 | 38.2 |

| Stomachache | 26 | 34.2 |

| Evil spirits | 19 | 25.0 |

| Fever | 16 | 21.1 |

| Seizures | 13 | 17.1 |

| Prophylactics | 12 | 15.8 |

| Diarrhea | 11 | 14.5 |

| Cough and flu | 5 | 6.6 |

| *Multiple responses were allowed | ||

References

-

-

- Langlois-Klassen D, Kipp W, Jhangri GS, Rubaale T. Use of traditional herbal medicine by AIDS patients in Kabarole District, western Uganda. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene [Internet]. 2007 Oct [cited 2025 Apr 1];77(4):757-763. Available from: https://www.ajtmh.org/view/journals/tpmd/77/4/article-p757.xml https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2007.77.757

- Declaration of Alma-Ata [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2019 Oct 8 [cited 2025 May 1]. 3 p. WHO Reference Number: WHO/EURO:1978-3938-43697-61471. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/declaration-of-alma-ata Download PDF to view full text.

- Duraffourd C, Lapraz JC, Chemli R. La plante médicinale: de la tradition à la science. [The medicinal plant – From tradition to science]. Paris (France): Grancher; 1997 Oct 15. 538 p. (Le corps et l’esprit).

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2010: Health Systems Financing: the Path to Universal Coverage [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2012 June 16 [cited 2025 May 1]. 106 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564021 Download PDF to view full text

- Kasilo OMJ, Wambebe C, Nikiema JB, Nabyonga-Orem J. Towards universal health coverage: advancing the development and use of traditional medicines in Africa. BMJ Glob Health [Internet]. 2019 Oct 11 [cited 2025 May 1];4(Suppl 9):e001517. Available from: https://gh.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001517 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001517

- World Bank Group. Rural population (% of total population) – Sub-Saharan Africa [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2018 [cited 2025 May 8]; [about 6 screens]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS?locations=ZG

- Mensah MLK, Komlaga G, Forkuo AD, Firempong C, Anning AK, Dickson RA. Toxicity and safety implications of herbal medicines used in Africa. In: Builders PF, editor. Herbal Medicine [Internet]. London (United Kingdom): IntechOpen; 2019 Jan 30 [cited 2025 May 1]. [about 21 screens]. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/58270 https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.72437

- Mahomoodally MF. Traditional medicines in africa: an appraisal of ten potent african medicinal plants. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine [Internet]. 2013 Dec 3 [cited 2025 May 5];2013(1): 617459. Available from: http://www.hindawi.com/journals/ecam/2013/617459/ https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/617459 Download PDF to view full text.

- Kofi B, Mhame PP, Kasilo OM. Clinical practices of African traditional medicine. The African Health Monitor [Internet]. 2010 Aug 1 [cited 2025 May 1]; Spec Iss 14:32-39. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2017-06/ahm-special-issue-14.pdf Download PDF to view full text.

- Abdullahi A. Trends and challenges of traditional medicine in africa. Afr J Trad Compl Alt Med [Internet]. 2011 Jul 15 [cited 2025 May 5];8(5S):115-23. Available from: http://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajtcam/article/view/67959 https://doi.org/10.4314/ajtcam.v8i5S.5 Download PDF to view full text.

- Makhavhu EM. Integrating traditional and allopathic child health: A healthcare transformation opportunity. Health SA Gesondheid [Internet]. 2024 Apr 24 [cited 2025 May 5];29: Available from: http://www.hsag.co.za/index.php/hsag/article/view/2501 https://doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v29i0.2501 Download PDF to view full text

- WHO AFRO Regional Committee for Africa. Enhancing the role of traditional medicine in health systems: a strategy for the African Region [Internet]. Brazaville (Congo): WHO; 2013 Sep 3 [cited 2025 May 1]; 9p. Document no: AFR/RC63/6. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/94302/AFR_RC63_6.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y Download PDF to view full text.

- Dambisya Y, Tindimwebwa G. Traditional remedies in children around eastern cape, South Africa. E Af Med Jrnl [Internet]. 2004 May 12 [cited 2025 May 1];80(8):402–5. Available from: http://www.ajol.info/index.php/eamj/article/view/8730 https://doi.org/10.4314/eamj.v80i8.8730 Download PDF to view full text.

- Mothibe M, Sibanda M. African traditional medicine: South African perspective. In: Mordeniz C, editor. Traditional and Complementary Medicine [Internet]. London (United Kingdom): IntechOpen; 2019 Feb 4 [cited 2025 May 1]. [about 24 screens]. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/books/traditional-and-complementary-medicine/african-traditional-medicine-south-african-perspective https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.83790

- Kwedi Nolna S, Ntonè R, Fouda Mbarga N, Mbainda S, Mutangala W, Boua B, Niba M, Okoko A. Integration of traditional healers in human African trypanosomiasis case finding in Central Africa: a quasi-experimental study. TropicalMed [Internet]. 2020 Nov 17 [cited 2025 May 1];5(4):172. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2414-6366/5/4/172 https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed5040172

- Munson PL, Mueller RA, Breese GR. Principles of Pharmacology: Basic Concepts and Clinical Applications. New York (NY): Hodder Education Publishers; 1996 Sep 1. 1808 p.

- Ikhoyameh M, Okete WE, Ogboye RM, Owoyemi OK, Gbadebo OS. Integrating traditional medicine into the African healthcare system post-Traditional Medicine Global Summit: challenges and recommendations. Pan Afr Med J [Internet]. 2024 Mar 27 [cited 2025 May 1];47: 146. Available from: https://www.panafrican-med-journal.com//content/article/47/146/full https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2024.47.146.43011

- Togarasei L, Mmolai SK, Kealotswe ON. ‘Quinine’, ‘Ditaola’ and the ‘Bible’: Investigating Batswana Health Seeking Practices. Journal for the Study of Religion [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2025 May 1]; 29(2):95–117. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24902916 Subscription or purchase required to view full text.

- Green B, Colucci E. Traditional healers’ and biomedical practitioners’ perceptions of collaborative mental healthcare in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Transcult Psychiatry [Internet]. 2020 Jan 14 [cited 2025 May 1];57(1):94–107. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1363461519894396 https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461519894396 Subscription or purchase required to view full text.

- Mutola S, Pemunta NV, Ngo NV. Utilization of traditional medicine and its integration into the healthcare system in Qokolweni, South Africa; prospects for enhanced universal health coverage. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice [Internet]. 2021 Apr 20 [version of record 2021 Apr 22; cited 2025 May 1];43:101386. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1744388121000852 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2021.101386

-

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Tables

| Demographic characteristics | Frequency | Percentages |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18-24 | 26 | 24.3 |

| 25-28 | 41 | 38.3 |

| 29-32 | 22 | 20.6 |

| >32 | 18 | 16.8 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 86 | 80.4 |

| Male | 21 | 19.6 |

| Religion | ||

| Muslim | 78 | 72.9 |

| Christian | 29 | 27.1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 39 | 36.4 |

| Married | 60 | 56.1 |

| Separated | 8 | 7.5 |

| Level of Education | ||

| No Formal education | 24 | 22.4 |

| Primary | 18 | 16.9 |

| Secondary | 39 | 36.4 |

| Tertiary | 26 | 24.3 |

| Tribe | ||

| Temne | 42 | 39.3 |

| Mende | 22 | 20.6 |

| Limba | 12 | 11.2 |

| Fula | 11 | 10.3 |

| Madingo | 9 | 8.4 |

| Krio | 7 | 6.5 |

| Soso | 4 | 3.7 |

| Residence | ||

| Western Urban | 55 | 51.4 |

| Western Rural | 42 | 39.3 |

| Other districts | 10 | 9.3 |

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of caregivers, N=107

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Child’s Age | ||

| 0 – 28 days | 3 | 3.9 |

| 29 days – <1 year | 28 | 36.8 |

| 1 – 5 years | 31 | 40.8 |

| > 5 years | 14 | 18.5 |

| Route of administration* | ||

| Oral | 67 | 88.2 |

| Topical | 25 | 32.9 |

| Enema | 2 | 2.6 |

| Scarification | 7 | 9.2 |

| Amount administered* | ||

| Not specified | 38 | 50.0 |

| Spoonful | 31 | 40.8 |

| Cupful | 15 | 19.7 |

| Bottle | 9 | 11.8 |

| Medication given by:* | ||

| Grandmother | 39 | 51.3 |

| Mother | 32 | 42.1 |

| Father | 4 | 5.3 |

| Herbalist | 19 | 25.0 |

| Indications* | ||

| Constipation | 29 | 38.2 |

| Stomachache | 26 | 34.2 |

| Evil spirits | 19 | 25.0 |

| Fever | 16 | 21.1 |

| Seizures | 13 | 17.1 |

| Prophylactics | 12 | 15.8 |

| Diarrhea | 11 | 14.5 |

| Cough and flu | 5 | 6.6 |

| *Multiple responses were allowed | ||

Table 2: Utilisation of Traditional Medicine among children, N=76

Figures

Keywords

- Traditional medicine

- Integration

- Universal health coverage