Lesson from the field | Open Access | Volume 8 (4): Article 101 | Published: 09 Dec 2025

Investigation and public health response to a confirmed case of streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis, Kadjebi District, Oti Region, Ghana, 2023

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Tables

| SN | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 09 May 2023 | Symptom onset with headache. Child absent from school. |

| 2 | 11 May 2023 | Visited Wawaso Community-based Health Planning and Services (CHPS) with fever (39.8°C), vomiting, loss of appetite; Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT)-positive malaria. |

| 3 | 14 May 2023 | Returned to CHPS with unresolved symptoms; referred to Jasikan Municipal Hospital. |

| 4 | 15 May 2023 | Admitted; uncle reported neck stiffness present for 4 days; clinician observed headache, fever (38.6°C), ear pain. Plan to manage case with Intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone and supportive treatment. |

| 5 | 16 May 2023 | Observed sore throat, stiff neck, and drooping eyelid. Meningitis suspected; Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) sample collected. District and Regional Surveillance Officers notified, investigation commenced. |

| 6 | 17 May 2023 | Wawaso CHPS staff commenced household contact tracing and follow-up of close contacts. |

| 7 | 18 May 2023 | CSF transported to National Public Health Reference Laboratory (NPHRL). |

| 8 | 19 May 2023 | Latex agglutination test negative for Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and Streptococcus pneumoniae; result updated on Surveillance Outbreak Response Management and Analysis System (SORMAS). |

| 9 | 21 May 2023 | Case responded well to treatment and discharged. |

| 10 | 23 May 2023 | Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) test confirmed Streptococcus pneumoniae; result updated on SORMAS. |

| 11 | 25 May 2023 | Outbreak investigation team visited the Wawaso community. |

Table 1. Chronology of key events in the detection, diagnosis, and public health response to a confirmed case of Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis, Wawaso community, Kadjebi district, Ghana, May 2023

| Outbreak Detection | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Date 1 | Date 2 | Interval | Target |

| Interval between onset of index case and detection at Jasikan Municipal Hospital | 09 May 2023 | 15 May 2023 | 6 days | < 3 days |

| Interval between initial outbreak case seen at Jasikan Municipal Hospital and reporting to district health team | 15 May 2023 | 16 May 2023 | 1 day | Within 24 hours |

| Cumulative interval between onset of index case and notification to district | 09 May 2023 | 16 May 2023 | 7 days | < 7 days |

| Outbreak Investigation | ||||

| Indicator | Yes | No | Target | |

| Case-based investigation form, SORMAS and line-lists completed | ✓ | 100% completion of form | ||

| Laboratory specimen taken | ✓ | Specimen collected in suspected case | ||

| Indicator | Date 1 | Date 2 | Interval | Target |

| Interval between notification of district and field investigation conducted | 16 May 2023 | 25 May 2023 | 9 days | Within 48 hours |

| Interval between sending specimens to the lab and receipt of results by the district | 18 May 2023 | 23 May 2023 | 5 days | 3–7 days (depending on test type) |

| Outbreak Response | ||||

| Indicator | Date 1 | Date 2 | Interval | Target |

| Interval between notification of outbreak to district and concrete response by district | 16 May 2023 | 17 May 2023 | 1 day | Within 48 hours of notification |

Table 2. Timeliness of detection, notification, investigation, and response to a confirmed case of Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis, Wawaso community, Kadjebi District, May 2023

Figures

Keywords

- Meningitis

- Streptococcus pneumoniae

- Public Health Response

- Oti Region

- Ghana

- Field Investigation

Mawuli Gohoho1,2,&, John Sonnyinado Duako Baffoe1,3, Thomas Vigbedor1,3, George Dzakah4, Robert Kokou Dowou5, Samuel Kyere6, Joyce Boakye-Yiadom4, Eric Nana Takyi6, Isaac Annobil2, Fortress Yayra Aku1,5

1Ghana Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Programme, School of Public Health, University of Ghana, Legon- Accra, Ghana, 2Jasikan Municipal Health Directorate, Ghana Health Service, Jasikan, Ghana, 3Oti Regional Health Directorate, Ghana Health Service, Jasikan, Ghana, 4Jasikan Municipal Hospital, Ghana Health Service, Jasikan, Ghana, 5Fred N. Binka School of Public Health, University of Health and Allied Sciences, Hohoe, Ghana, 6Kadjebi District Health Directorate, Ghana Health Service, Jasikan, Ghana

&Corresponding author: Mawuli Gohoho, Disease Control and Surveillance Unit, Jasikan Municipal Health Directorate, Ghana Health Service, Jasikan, Ghana. Email: mawulikgohoho@gmail.com, mawuli.gohoho@ghs.gov.gh ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0001-4357-3509

Received: 12 Oct 2025, Accepted: 09 Dec 2025, Published: 09 Dec 2025

Domain: Field Epidemiology, Outbreak Response

Keywords: Meningitis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Public Health Response, Oti Region, Ghana, Field Investigation

©Mawuli Gohoho et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Mawuli Gohoho et al., Investigation and public health response to a confirmed case of streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis, Kadjebi District, Oti Region, Ghana, 2023. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8(4):101. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00231

Abstract

Introduction: Bacterial meningitis remains a major life-threatening condition that requires prompt detection and response due to its rapid onset and high case fatality rate, which can reach about 70% when untreated. On 23 May 2023, the National Public Health Reference Laboratory confirmed the first Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis case in Kadjebi District, Oti Region of Ghana, triggering a public health response. We investigated to ascertain the situation, confirm the diagnosis, and implement preventive and control measures.

Methods: We conducted a field investigation in Wawaso community between 25 May and 29 May 2023. A suspected case was defined as any person residing in Kadjebi District from 29 April to 19 May 2023 presenting with sudden onset of fever and neck stiffness or other meningeal signs, while laboratory identification of a bacterial pathogen constituted a confirmed case. Cerebrospinal fluid was collected and tested using latex agglutination and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction tests. We reviewed health records, interviewed community members, and performed contact tracing. We analyzed data by person, place and time.

Results: We found one confirmed case of S. pneumoniae meningitis in a 9-year-old unvaccinated male pupil from Wawaso. He presented with headache, fever (38.6°C) and later developed neck stiffness and drooping eyelid. He had no recent travel history or known contact with a similar illness before symptom onset and recovered fully with treatment without any neurological sequelae. The case was detected 6 days after symptom onset and reported to the district within 24 hours after meningitis was suspected. Laboratory confirmation was obtained within 5 days, and field investigation commenced 9 days after notification. From the records review, no additional cases were identified as none met the case definition. We also listed 140 contacts and monitored daily for ten days, and none developed symptoms suggestive of meningitis.

Conclusion: This is a sporadic case of S. pneumoniae meningitis with no evidence of secondary transmission. Timely case detection was not achieved. We recommend sensitization of clinicians on meningitis surveillance to improve timely detection and reporting.

Introduction

Meningitis is an inflammation of the protective membranes (meninges) surrounding the brain and spinal cord which remains a significant global public health challenge. It can be caused by various agents, including viruses, bacteria, parasites, and fungi [1]. Among these, bacterial meningitis is a particularly acute and life-threatening condition that requires prompt detection and response due to its rapid onset and high risk of mortality [2]. Globally, case-fatality rates can be as high as 70% if untreated, with 10-20% of survivors experiencing permanent sequelae such as hearing loss, neurological disability, or loss of limb function [1]. In Ghana, the reported case-fatality rate for meningitis ranges between 36% and 50% [3].

Ghana is situated within the African meningitis belt which experiences seasonal hyperendemicity and recurrent large-scale outbreaks, typically during the dry season (November to April) [4,5]. Historically, these epidemics were predominantly caused by Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A (NmA) [6]. However, following the introduction of the serogroup A meningococcal conjugate vaccine in Ghana in 2012 [7], there has been a substantial decline in NmA cases. Consequently, other bacterial species, particularly Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae) and Neisseria meningitidis serogroup W (NmW) have increasingly emerged as major causative agents in meningitis outbreaks across Ghana. For instance, a 2016 meningitis outbreak in Northern Ghana saw S. pneumoniae predominating in the early weeks, followed by NmW [7]. The Brong Ahafo Region also experienced a large S. pneumoniae meningitis outbreak in 2015/2016 [1].

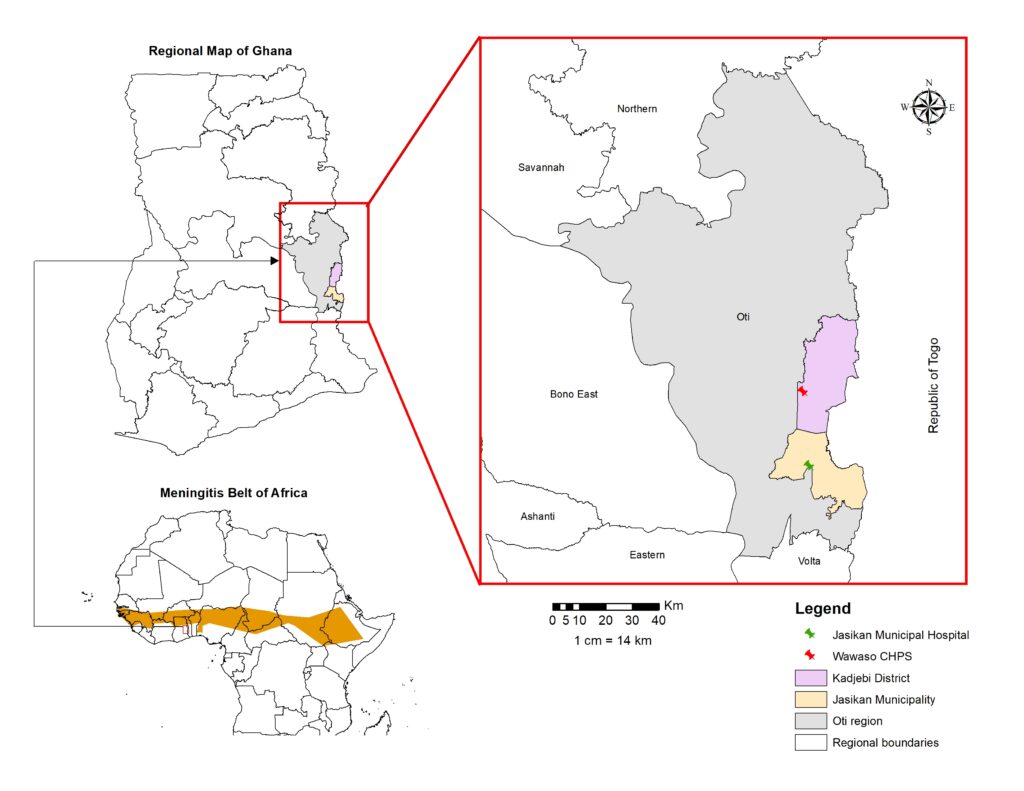

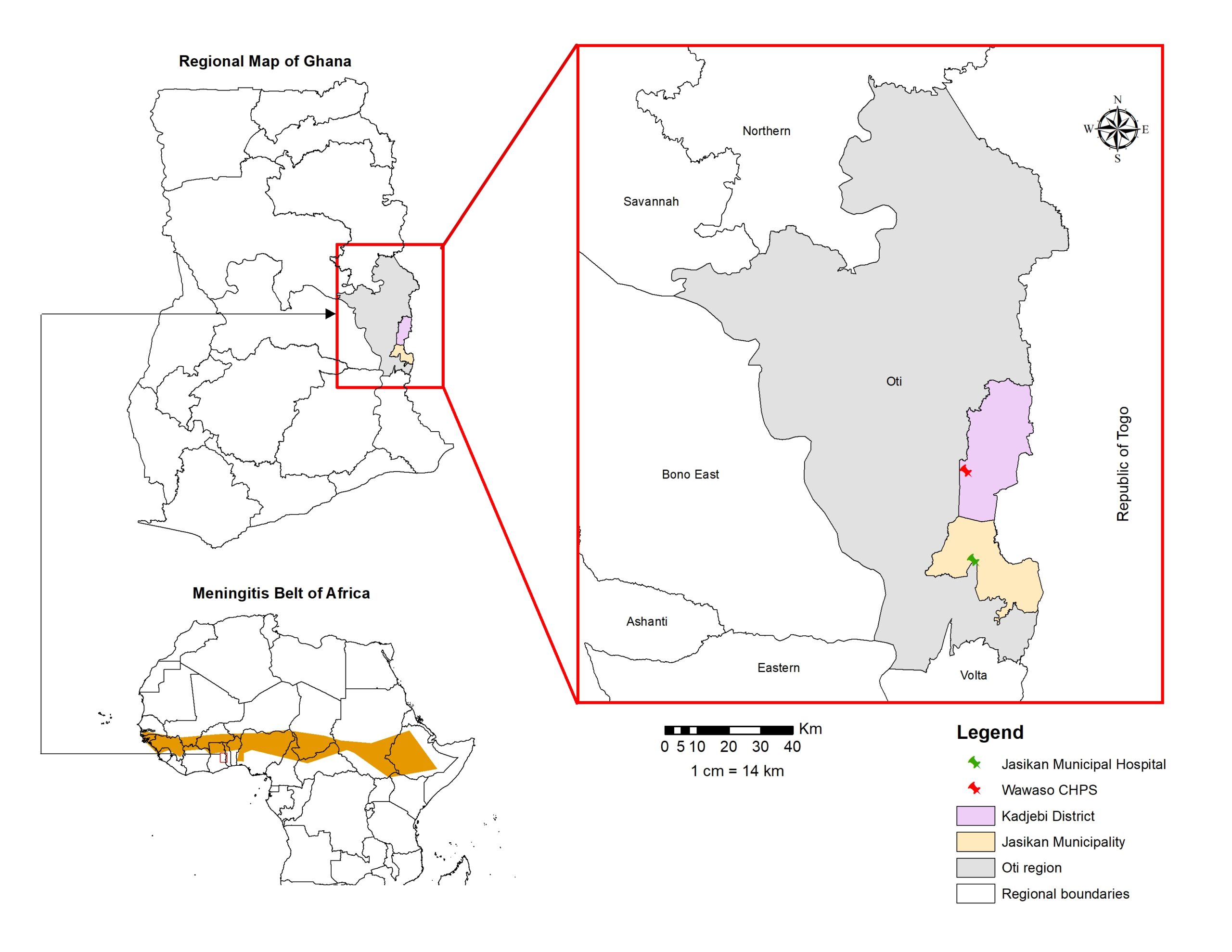

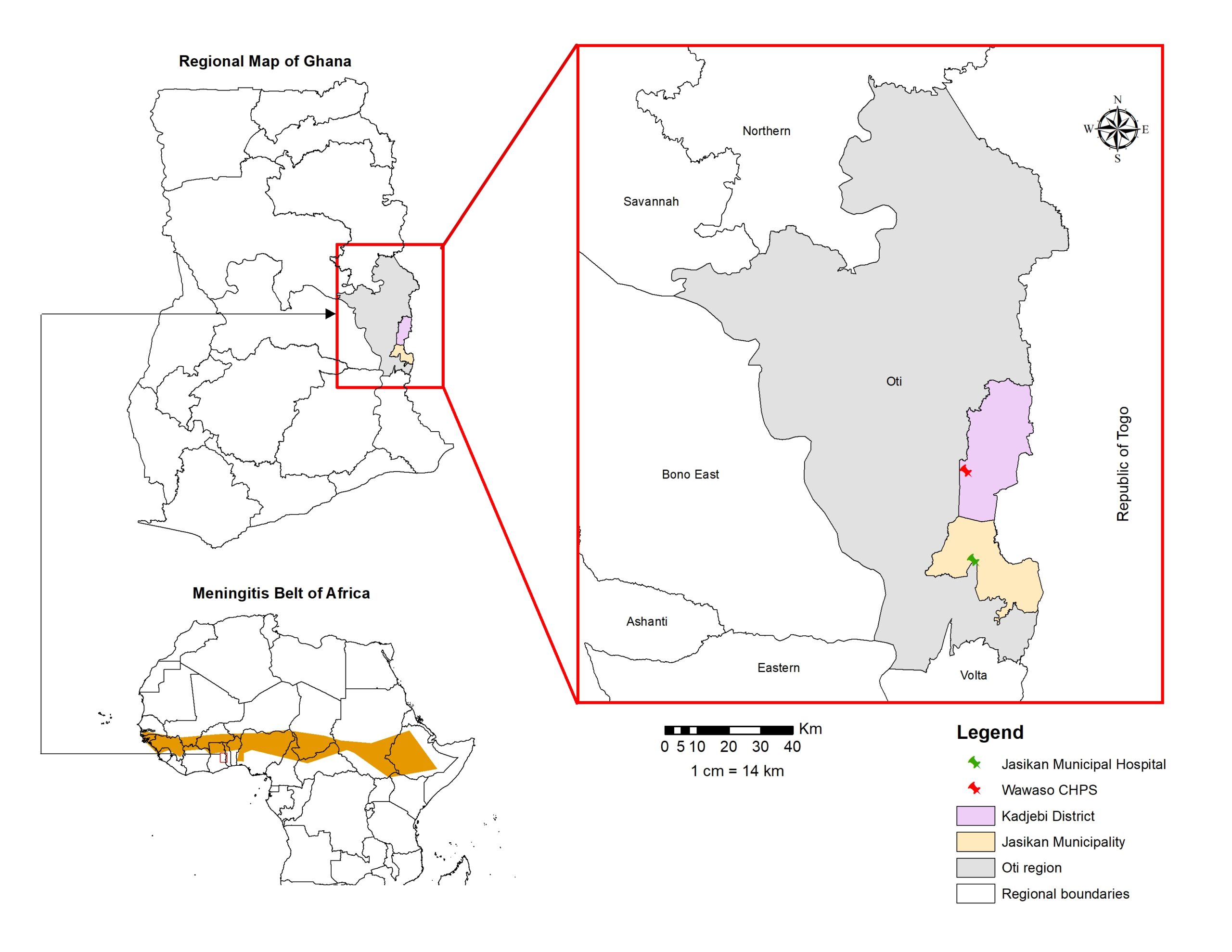

The Oti Region is in the eastern part of Ghana and shares boundaries with Bono East, Savannah, Northern and Volta Regions and the Republic of Togo, with the River Oti forming its western border. It lies south of the traditional meningitis belt of Ghana, where most outbreaks have historically occurred [2,3,6,7]. On 23 May 2023, the National Public Health Reference Laboratory (NPHRL) notified the Jasikan Municipal Health Directorate of a confirmed case of bacterial meningitis caused by S. pneumoniae. This event was particularly significant as it represented the first laboratory-confirmed meningitis case reported in the Kadjebi District of the Oti Region of Ghana, occurring outside the usual high-risk zones for meningitis in Ghana. Based on the above, a field investigation was conducted to characterise the event, confirm the diagnosis and implement control measures.

Methods

Study design and outbreak setting

We investigated a suspected case of meningitis from 25 to 29 May 2023 in the Wawaso community of the Kadjebi-Asato Sub-district in the Kadjebi District. The district shares a southern boundary with Jasikan Municipality, which houses the Jasikan Municipal Hospital. This facility functions as a primary-level referral facility for surrounding districts, including Kadjebi, and played a key role in surveillance and clinical management during this investigation. Both Kadjebi and Jasikan districts are located within the Oti Region of Ghana (a region carved out of the northern part of Volta Region in December 2018) (Figure 1). This region lies south of the African meningitis belt (Figure 1). Environmental conditions such as high temperatures, dusty weather, and low humidity are known to predispose inhabitants to meningitis infections. Routine meningitis surveillance in the region operates primarily through a passive reporting system, consistent with the national framework for notifiable diseases and conditions. Nonetheless, when outbreaks are reported within the broader meningitis belt or specifically within the Oti Region, the surveillance system transitions to an enhanced mode as part of the public health response measures.

Case definition

A suspected meningitis case was defined as any person residing in Kadjebi District from 29 April to 19 May 2023 with a sudden onset of fever (>38.5 °C rectal or 38.0 °C axillary) and neck stiffness or other meningeal signs, including bulging fontanelle in infants [8], consistent with standard WHO guidelines for bacterial meningitis surveillance. A confirmed case of meningitis was defined as any suspected case with laboratory confirmation through the identification of a causative pathogen in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) using culture, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), or rapid diagnostic tests [8].

Specimen collection and transportation

CSF samples were collected under aseptic conditions and placed in sterile tubes for latex agglutination and RT-PCR testing, which were transported using the triple packaging system under cold chain conditions to the NPHRL. The collected samples were transported alongside the corresponding case-based forms, and all associated information was subsequently entered into the Surveillance Outbreak Response Management and Analysis System (SORMAS).

Case finding

We conducted a retrospective case finding to identify any additional suspected meningitis cases that occurred in Kadjebi District between 29 April and 19 May 2023, which correspond to one full incubation period before and after illness onset of the index case. We reviewed medical records of the case, consulting room registers, and other patient folders, along with outpatient department registers at the health facility, to ensure comprehensive capture of all potential cases that sought care. We also obtained additional information through interviews with the caregiver, attending clinician, nursing staff, and teachers. An active case search was conducted in the household, school, and community of the index case to identify any additional meningitis cases.

Data source, tools and variables collected

Data were primarily collected from patient medical records, consulting room registers, and responses provided by the caregiver and attending health staff during completion of the meningitis case-based investigation form. This form captured variables such as demographic characteristics, date of symptom onset, signs and symptoms, vaccination history, exposure history, hospitalization details, and outcome [8]. Laboratory feedback was obtained from the SORMAS as updated by the NPHRL. Standardized tools, including the meningitis contact line-listing and tracing form for close contacts, were used to document and follow up all identified contacts. All data were updated in the SORMAS, and a meningitis line-list was completed at the district level and shared with the regional surveillance officer. Diagnostic tests and laboratory findings included results from latex agglutination and RT-PCR tests.

Data analysis

We performed a descriptive analysis by time, person, and place. Timelines of outbreak events were reviewed to assess timeliness in case detection, reporting, investigation, laboratory confirmation, and response, using indicators from the Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) Outbreak Evaluation Form [8]. For person analysis, we summarized demographic and clinical variables of the case and contacts. For place analysis, we described the geographic setting of the community and nearest health facility within the affected community. Laboratory tests performed, test outcome and pathogen isolated were retrieved from the SORMAS. Descriptive summaries were generated using Microsoft Excel software.

Ethical considerations

This investigation was conducted as part of a public health response to a confirmed meningitis outbreak in line with national IDSR guidelines [8]; hence, it did not require ethical approval. However, permission was obtained from the Kadjebi District Health Directorate prior to commencing the investigation. Verbal informed consent was sought from the caregiver of the case and the interviewed individuals. Participant confidentiality was protected by using coded identifiers and storing all data on a password-protected computer throughout the investigation

Results

Descriptive epidemiology

We identified a confirmed meningitis case involving a 9-year-old male pupil from Wawaso in Kadjebi District of the Oti Region of Ghana. The child had been residing in the community for several months, had not travelled within 10 days prior to symptom onset, and had no known contact with anyone with a similar illness. The only identifiable risk exposure was the absence of documented vaccination with pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) or meningococcal A conjugate vaccine (MenA). His symptom began on 9 May 2023 with headache, followed by fever and neck stiffness. On 11 May, the case visited Wawaso Community-based Health Planning and Services (CHPS) and was managed for uncomplicated malaria after testing positive using Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT) (Table 1). However, the symptoms persisted. He returned three days later with a persistent headache, fever, vomiting, and ear pain and was referred to Jasikan Municipal Hospital. On 15 May, the child was admitted. The uncle reported he had observed neck stiffness in the child four days prior. During admission, the clinical team observed ear pain, neck stiffness, sore throat, and drooping of the left eyelid. The team suspected meningitis, and CSF was collected the next day. He was managed with intravenous ceftriaxone and supportive treatment. His condition improved, and he was discharged in a stable condition without neurological deficits on 21 May.

Laboratory confirmation of diagnosis

The CSF samples collected were transported to the NPHRL on 18 May. A latex agglutination test performed on 19 May was negative for Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and S. pneumoniae. However, RT-PCR results uploaded onto SORMAS on 23 May confirmed S. pneumoniae as the causative agent (Table 1).

Timeliness of detection, notification, and response

The case was detected 6 days after symptom onset when the child was referred from Wawaso CHPS to Jasikan Municipal Hospital. After meningitis was suspected, the case was reported to the district within 24 hours. Overall, notification to the district occurred 7 days after onset. The CSF sample was sent to the NPHRL 2 days after collection, and results were received within 5 days. The district initiated household contact tracing within 24 hours of notification, and a full field investigation was conducted 9 days later, which included active surveillance and health education (Table 2).

Active case search and contact tracing

From the records reviewed at Wawaso CHPS, none of the individual patient records met the applied case definition. No suspected cases were identified during the defined search period, and therefore, no samples were collected for laboratory confirmation. However, 140 total contacts of the index case were identified, listed, and traced. This was initiated within 24 hours after the case was suspected, and screening was carried out to assess symptoms that may have occurred since the onset of the case’s symptoms. Five were household contacts, of whom 4 (80%) were female and 1 (20%) was a male while 3 (60%) were below 15 years and 2 (40%) were 15 years or older. All had either slept or eaten in the same household, and one had direct physical contact with the case, while assisting during episodes of vomiting and cleaning respiratory secretions. At the school, 116 pupils were screened, while 10 absent pupils were followed up and screened at their respective households. Additionally, three teachers and six healthcare workers who managed the case were screened. None of the contacts developed symptoms suggestive of meningitis during daily follow-up for ten days. No secondary cases were identified during contact tracing. The index case occurred in May 2023, more than two years prior to this report. Since that time, no additional meningitis cases have been reported from the affected community or the district, as surveillance activities have remained active and sustained.

Public health actions

We engaged 52 men preparing for a funeral, as well as all pupils, teachers, healthcare workers, and household members identified during contact tracing, and provided health education on recognising key symptoms, early reporting, prompt treatment, and preventive measures.

Discussion

The investigation confirmed a case of S. pneumoniae meningitis in a 9-year-old child from Wawaso in the Kadjebi District. The illness followed a typical clinical course, beginning with fever and headache and later progressing to neck stiffness and cranial nerve involvement [1,2,9]. Although the initial malaria diagnosis delayed appropriate case detection, the referral to the hospital and subsequent lumbar puncture led to the confirmation of S. pneumoniae by RT-PCR. The negative latex agglutination test performed earlier suggests the case could have been missed without RT-PCR confirmation. It highlights the importance of molecular testing in detecting S. pneumoniae infections [10]. However, the absence of pneumococcal serotyping limited the understanding of circulating strains and their relation to vaccine-preventable types.

The timeliness in case detection was not met, as the child presented to Wawaso CHPS 2 days after symptom onset, but meningitis was not suspected until the child was referred to Jasikan Municipal Hospital 6 days after symptom onset, where appropriate investigation and notification were initiated. This delay could be due to the initial malaria diagnosis at the CHPS before referral, as well as the distance and transport challenges between Wawaso and the Municipal Hospital. Health workers at the lower levels of the health system, therefore, require regular orientation to improve early disease recognition. Since malaria is often considered a default diagnosis in endemic settings [11], such trainings should emphasise maintaining a high suspicion index of for other priority diseases, including meningitis to ensure timely detection and reporting.

Once meningitis was suspected at the Jasikan Municipal Hospital, the case was promptly reported, signifying a high level of alertness among clinicians in terms of these priority disease conditions. Additionally, the timely feedback on laboratory confirmation, facilitated through the use of the digital platform, SORMAS demonstrates the essential role of real-time information capture in outbreak response particularly in supporting data entry, case tracking, and communication among health facilities, district and regional authorities, and reference laboratories [12]. The primary delay was observed during the field investigation, which was completed nine days after notification, substantially exceeding the expected timeframe of 48 hours. The delay was attributable to the waiting period for laboratory feedback and the time required to mobilise resources for the response. Such delays can affect early response activities, including community education, contact management, and surveillance, which could increase the risk of missing potential cases. However, during the waiting period, household contact tracing was initiated a day after notification, which supported early response activities.

As part of public health actions, we conducted community sensitization targeted at close contacts of the case, community members involved in funeral preparation, pupils and school staff, and nearby households. Such community engagement and risk‑communication activities are essential for managing disease outbreaks [13]. Through sensitization, communities receive accurate information on disease signs, prevention, and early care‑seeking, which helps detect new cases early and reduce transmission [14].

Conclusion

This is a sporadic case of S. pneumoniae meningitis in Kadjebi District with no evidence of secondary transmission. The timeliness of case detection was not met, partly due to initial malaria diagnosis and delays in referral. In areas with high malaria prevalence, a positive malaria RDT should not preclude consideration of other priority disease conditions, particularly meningitis. Regular IDSR sensitization of clinicians at the primary healthcare level is recommended to improve the index of suspicion for meningitis and to ensure timely detection and reporting.

What is already known about the topic

- Meningitis remains a major public health concern in Ghana, particularly in regions within the African meningitis belt.

- meningitidis has historically been the primary cause of large-scale meningitis outbreaks in Ghana.

- The introduction of PCV and MenA has led to a decline in cases caused by their respective target pathogens.

- pneumoniae has increasingly emerged as a significant cause of meningitis outbreaks in Ghana.

- Routine surveillance systems have played a key role in detecting and responding to meningitis cases in endemic regions.

What this study adds

- This is the first confirmed pneumoniae meningitis case detected in Kadjebi District of the Oti Region of Ghana.

- The case occurred in a child with no documented history of PCV or MenA vaccination.

- Public health response included contact tracing and targeted health education in both community and school settings.

- The findings emphasize the need to sensitize primary healthcare clinicians using the IDSR to improve recognition of meningitis and ensure timely detection and reporting.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Oti Regional Health Directorate, Kadjebi District Health Directorate, Jasikan Municipal Health Directorate, Jasikan Municipal Hospital, health staff of Wawaso CHPS and community members of Wawaso for their support during the investigation and response to the outbreak.

Authors´ contributions

Thomas Vigbedor led the investigation and response to the outbreak and edited the manuscript. Mawuli Gohoho provided technical support during the outbreak investigation and drafted the manuscript. John S.D. Baffoe, George Dzakah, Samuel Kyere, Joyce Boakye-Yiadom and Robert K. Dowou provided technical support during the outbreak investigation and edited the manuscript. Isaac Annobil and Eric N. Takyi supervised the outbreak investigation and response and reviewed the manuscript. Fortress Y. Aku edited and reviewed the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the manuscript for publication.

| SN | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 09 May 2023 | Symptom onset with headache. Child absent from school. |

| 2 | 11 May 2023 | Visited Wawaso Community-based Health Planning and Services (CHPS) with fever (39.8°C), vomiting, loss of appetite; Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT)-positive malaria. |

| 3 | 14 May 2023 | Returned to CHPS with unresolved symptoms; referred to Jasikan Municipal Hospital. |

| 4 | 15 May 2023 | Admitted; uncle reported neck stiffness present for 4 days; clinician observed headache, fever (38.6°C), ear pain. Plan to manage case with Intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone and supportive treatment. |

| 5 | 16 May 2023 | Observed sore throat, stiff neck, and drooping eyelid. Meningitis suspected; Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) sample collected. District and Regional Surveillance Officers notified, investigation commenced. |

| 6 | 17 May 2023 | Wawaso CHPS staff commenced household contact tracing and follow-up of close contacts. |

| 7 | 18 May 2023 | CSF transported to National Public Health Reference Laboratory (NPHRL). |

| 8 | 19 May 2023 | Latex agglutination test negative for Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and Streptococcus pneumoniae; result updated on Surveillance Outbreak Response Management and Analysis System (SORMAS). |

| 9 | 21 May 2023 | Case responded well to treatment and discharged. |

| 10 | 23 May 2023 | Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) test confirmed Streptococcus pneumoniae; result updated on SORMAS. |

| 11 | 25 May 2023 | Outbreak investigation team visited the Wawaso community. |

| Outbreak Detection | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Date 1 | Date 2 | Interval | Target |

| Interval between onset of index case and detection at Jasikan Municipal Hospital | 09 May 2023 | 15 May 2023 | 6 days | < 3 days |

| Interval between initial outbreak case seen at Jasikan Municipal Hospital and reporting to district health team | 15 May 2023 | 16 May 2023 | 1 day | Within 24 hours |

| Cumulative interval between onset of index case and notification to district | 09 May 2023 | 16 May 2023 | 7 days | < 7 days |

| Outbreak Investigation | ||||

| Indicator | Yes | No | Target | |

| Case-based investigation form, SORMAS and line-lists completed | ✓ | 100% completion of form | ||

| Laboratory specimen taken | ✓ | Specimen collected in suspected case | ||

| Indicator | Date 1 | Date 2 | Interval | Target |

| Interval between notification of district and field investigation conducted | 16 May 2023 | 25 May 2023 | 9 days | Within 48 hours |

| Interval between sending specimens to the lab and receipt of results by the district | 18 May 2023 | 23 May 2023 | 5 days | 3–7 days (depending on test type) |

| Outbreak Response | ||||

| Indicator | Date 1 | Date 2 | Interval | Target |

| Interval between notification of outbreak to district and concrete response by district | 16 May 2023 | 17 May 2023 | 1 day | Within 48 hours of notification |

References

- Letsa T, Noora CL, Kuma GK, Asiedu E, Kye-Duodu G, Afari E, Kuffour OA, Opare J, Nyarko KM, Ameme DK, Bachan EG, Issah K, Aseidu-Bekoe F, Aikins M, Kenu E. Pneumococcal meningitis outbreak and associated factors in six districts of Brong Ahafo region, Ghana, 2016. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2018 Jun 22 [cited 2025 Dec 9];18(1):781. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-018-5529-z doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5529-z

- Issahaku GR, Amoatika DA, Ameme DK, Bandoh DA, Sackey SO, Kenu E. Imminent meningitis outbreak prevented by early warning and response action: Nadowli-Kaleo District, Upper West Region, Ghana-2017. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health [Internet]. 2022 Jun 6 [cited 2025 Dec 9];5(2). Available from: https://www.afenet-journal.net/content/article/5/12/full/ doi:10.37432/jieph.2022.5.2.60

- Richard Alogitega W, Boadiwaa Amo-Yeboah A, Yakubu M, Gyesi Issahaku R, Baffour Appiah A, Kenu E. Analysis of meningitis surveillance data 2014-2018, Bawku Municipality, Ghana. JIEPH [Internet]. 2024 Oct 18 [cited 2025 Dec 9];7(4):49. Available from: https://www.afenet-journal.net/content/article/7/49/full/ doi:10.37432/jieph.2024.7.4.140

- Harrison LH, Trotter CL, Ramsay ME. Global epidemiology of meningococcal disease. Vaccine [Internet]. 2009 May [cited 2025 Dec 9];27(Suppl 2):B51-B63. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0264410X09006173 doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.04.063

- Weber MW, Herman J, Jaffar S, Usen S, Oparaugo A, Omosigho C, Adegbola RA, Greenwood BM, Mulholland EK. Clinical predictors of bacterial meningitis in infants and young children in The Gambia. Tropical Medicine & International Health [Internet]. 2002 Sep 10 [cited 2025 Dec 9];7(9):722-731. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00926.x doi:10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00926.x

- Nuoh RD, Nyarko KM, Nortey P, Sackey SO, Lwanga NC, Ameme DK, Nuolabong C, Abdulai M, Wurapa F, Afari E. Review of meningitis surveillance data, Upper West Region, Ghana 2009-2013. Pan African Medical Journal [Internet]. 2016 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Dec 9];25(Suppl 1):9. Available from: http://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/series/25/1/9/full/ doi:10.11604/pamj.supp.2016.25.1.6180

- Aku FY, Lessa FC, Asiedu-Bekoe F, Balagumyetime P, Ofosu W, Farrar J, Ouattara M, Vuong JT, Issah K, Opare J, Ohene SA, Okot C, Kenu E, Ameme DK, Opare D, Abdul-Karim A. Meningitis outbreak caused by vaccine-preventable bacterial pathogens — Northern Ghana, 2016. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report [Internet]. 2017 Aug 4 [cited 2025 Dec 9];66(30):806-810. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6630a2.htm

- Ghana Ministry of Health. Ghana Health Service. Technical Guidelines for Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response in Ghana [Internet]. Accra (Ghana): Ministry of Health Ghana; 2002 Apr [cited 2025 Dec 9]. 222 p. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.gh/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Integrated-Disease-Surveillance-and-Response-Ghana-Guidelines.pdf

- Kabanunye MM, Adjei BN, Gyaase D, Nakua EK, Afriyie SO, Enuameh Y, Owusu M. Risk factors associated with meningitis outbreak in the Upper West Region of Ghana: A matched case-control study. Borrow R, editor. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2024 Aug 26 [cited 2025 Dec 9];19(8):e0305416. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305416 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0305416

- Mosadegh M, Asadian R, Darb Emamie A, Rajabpour M, Najafinasab E, Pourmand MR, Azarsa M. Impact of laboratory methods and gene targets on detection of streptococcus pneumoniae in isolates and clinical specimens. Reports of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology [Internet]. 2020 Jul 10 [cited 2025 Dec 9];9(2):216-222. Available from: http://rbmb.net/article-1-457-en.html doi:10.29252/rbmb.9.2.216

- Peterson I, Kapito-Tembo A, Bauleni A, Nyirenda O, Pensulo P, Still W, Valim C, Cohee L, Taylor T, Mathanga DP, Laufer MK. Overdiagnosis of malaria illness in an endemic setting: a facility-based surveillance study in Malawi. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene [Internet]. 2021 May 3 [cited 2025 Dec 9];104(6):2123-2130. Available from: https://www.ajtmh.org/view/journals/tpmd/104/6/article-p2123.xml

- Barth-Jaeggi T, Houngbedji CA, Palmeirim MS, Coulibaly D, Krouman A, Ressing C, Wyss K. Introduction and acceptability of the surveillance outbreak response management and analysis system (SORMAS) during the COVID-19 pandemic in Côte D’Ivoire. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2023 Nov 7 [cited 2025 Dec 9];23(1):2189. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-023-17026-3 doi:10.1186/s12889-023-17026-3

- Health communication as a viable tool in the control and prevention of meningitis in Nigeria: an analytical audience perspective. British Journal of Mass Communication and Media Research (BJMCMR) [Internet]. 2023 Aug 14 [cited 2025 Dec 9];3(1):25-40. Available from: https://abjournals.org/bjmcmr/papers/volume-3/issue-1/health-communication-as-a-viable-tool-in-the-control-and-prevention-of-meningitis-in-nigeria-an-analytical-audience-perspective/ doi:10.52589/BJMCMR-0UDQKMKX

- Questa K, Das M, King R, Everitt M, Rassi C, Cartwright C, Ferdous T, Barua D, Putnis N, Snell AC, Huque R, Newell J, Elsey H. Community engagement interventions for communicable disease control in low- and lower-middle-income countries: evidence from a review of systematic reviews. International Journal for Equity in Health [Internet]. 2020 Apr 6 [cited 2025 Dec 9];19(1):51. Available from: https://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12939-020-01169-5 doi:10.1186/s12939-020-01169-5