Research![]() | Volume 8 (1), Article 11, 21 Apr 2025

| Volume 8 (1), Article 11, 21 Apr 2025

Measles resurgence: an outbreak investigation in Chimanimani District, Manicaland Province, Zimbabwe, 2022

Ernest Tsarukanayi Mauwa1, 2, Owen Mugurungi2, Gerald Shambira1, Tsitsi Juru3, Addmore Chadambuka3, &, Notion Gombe4, Mufuta Tshimanga1

1University of Zimbabwe, Department of Global Public Health and Family Medicine, Harare, Zimbabwe, 2AIDS and TB and Unit, Ministry of Health and Child Care, Harare, Zimbabwe, 3Zimbabwe Field Epidemiology Training Program, Harare, Zimbabwe, 4African Field Epidemiology Network, Harare, Zimbabwe

&Corresponding author: Addmore Chadambuka, Department of Global Public Health and Family Medicine, University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe, E-mail: achadambuka1@yahoo.co.uk

Received: 27 May 2024, Accepted: 16 Apr 2025, Published: 21 Apr 2025

Domain: Outbreak Investigation, Measles Elimination, Vaccine-Preventable Diseases

Keywords: Measles, outbreak, Vaccination, Apostolic, Chimanimani, Manicaland province, Zimbabwe

This article is published as part of the Eighth AFENET Scientific Conference Supplement: Volume Two, commissioned by

African Field Epidemiology Network

Ground Floor, Wings B & C

Lugogo House

Plot 42, Lugogo By-Pass

PO Box 12874 Kampala

Uganda.

©Ernest Tsarukanayi Mauwa et al Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Ernest Tsarukanayi Mauwa et al Measles resurgence: an outbreak investigation in Chimanimani District, Manicaland Province, Zimbabwe, 2022. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8(1):11. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph.supp.2025.8.2.12.12

Abstract

Introduction: Measles is a vaccine-preventable disease. Children who are unvaccinated, below 5 years of age, or malnourished are at risk of severe disease. There were five laboratory-confirmed measles IgM-positive cases in the week ending July 17, 2022, in Chimanimani District. We investigated factors associated with contracting measles in Chimanimani District.

Methods: We conducted a 1:1 unmatched case-control study. A case was a Chimanimani District resident aged below 15 years who had measles signs and symptoms or tested IgM positive between August 06 and September 06, 2022. Controls were neighbours without measles. Cases were randomly selected. We recruited 126 cases and 126 controls. An interviewer-administered questionnaire and line list were used to obtain data about the outbreak. District vaccination coverage was analysed from annual reports. We conducted bivariate and multivariate analysis.

Results: Majority 102 (81.0%) of measles cases were unvaccinated while 58 (46.0%) controls were unvaccinated. Chimanimani District measles vaccination coverage ranged between 70–89% during 2018-2022. Children of caregivers that objected COVID-19 vaccinations were more likely to contract measles [Odds Ratio (OR) 4.80, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) 2.63-8.76)]. Being unvaccinated [Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) 4.06, 95% CI (2.21-7.48)], age of child less than five years [AOR 2.25, 95% CI (1.24-4.08)] and belonging to the Apostolic religion [AOR 2.78, 95% CI (1.48-5.19)] were independent risk factors for contracting measles.

Conclusion: Measles outbreak occurred due to low vaccination coverage amidst a huge proportion of vaccine objectors, a highly susceptible population, and a lack of herd immunity. To attain and sustain herd immunity, we recommend increasing routine and supplementary vaccination coverage to at least 95%.

Introduction

Measles is a vaccine-preventable disease [1]. It is very contagious [2]: 90% of non-immune close contact with an infected person will also become infected [3]. About 32 million deaths have been averted by measles vaccination worldwide [4]. Measles elimination relies on strong case-based surveillance systems [5]. Populations at risk of severe measles disease and death include unvaccinated children, children under five years of age, malnourished individuals, immune-compromised people (e.g., HIV positive) and unvaccinated pregnant women [6–8]. The measles vaccine is safe, effective and inexpensive. It costs about one United States dollar to immunize a child against measles and it has lifelong immunity [8].

Clusters of unvaccinated children pose risks for local disease outbreaks [9]. Routine immunization (RI) must provide high and equitable coverage with measles-containing vaccine 1 (MCV1) and MCV2 [10]. The MCV1 has an efficacy of about 93% and MCV2 of 97%, respectively [3]. Herd immunity is met when there is MCV 1 and MCV 2 vaccination coverage of 95% [11,12]. Supplemental immunizations (SIAs) can achieve higher and more equitable coverage than RI, but do not reach the levels needed for measles elimination [13]. Globally, RIs of vaccine-preventable diseases like measles, were disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic response [14]. A systematic review in 2022 showed a decline in immunization uptake during COVID-19 [15].

The Chimanimani district was affected by the Cyclone Idai natural disaster in 2019 during the COVID-19 outbreak. This caused disruption to RI, SIAs and Vitamin A supplementation, as well as further strain on the health system coupled with poor measles surveillance. Additionally, transportation and movement of people, goods and services were negatively affected, with caregivers having challenges in accessing vaccination centres and supply disruptions.

Justification of the study

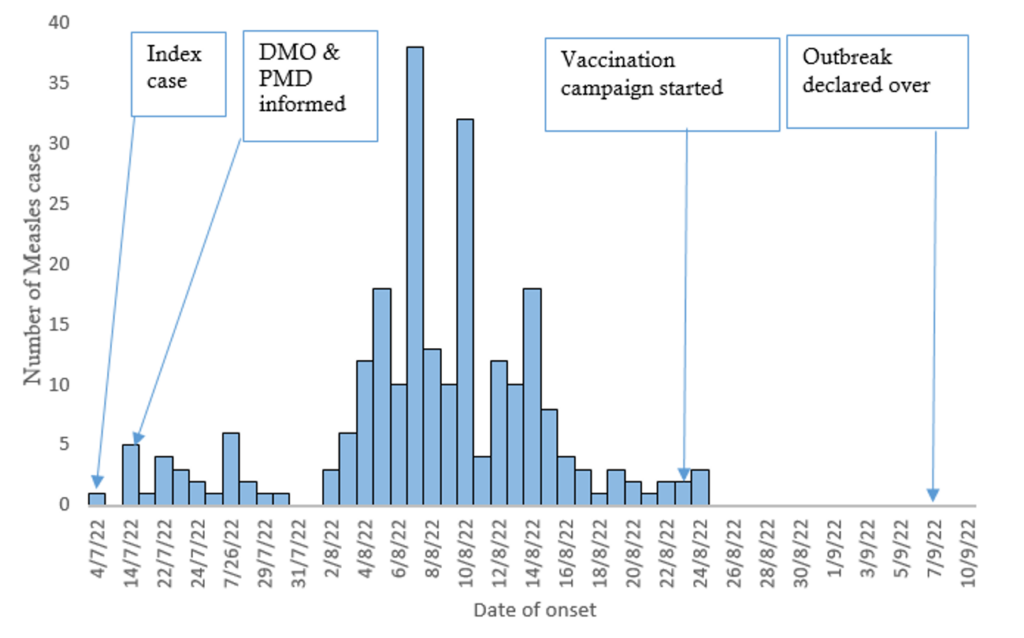

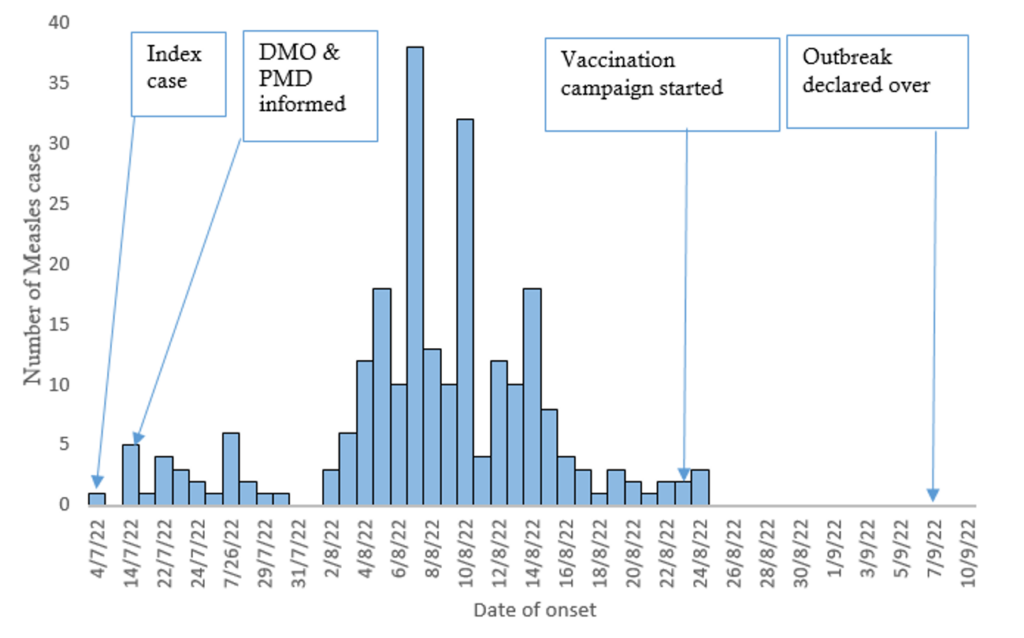

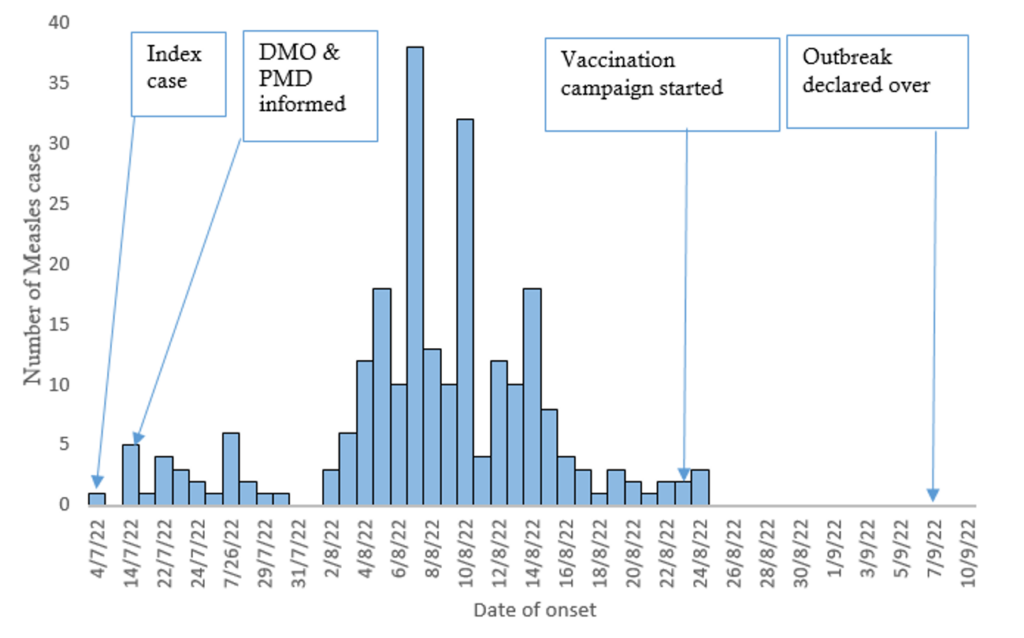

In 2022, the districts severely afflicted by the measles outbreak in Manicaland province were Chimanimani, Buhera, and Mutasa. The District Medical Officer (DMO) and the Manicaland Provincial Medical Director (PMD) were informed on July 14th, 2022 about the measles outbreak. Five laboratory-confirmed IgM cases of measles in Chimanimani District, Manicaland Province, were identified week ending July 17, 2022, during the weekly disease surveillance. By August 09th, 2022, there were over 65 suspected cases. The cases were amongst the apostolic sect of Johanne Marange Apostolic Church.

All suspected cases and deaths were of the Johanne Marange Apostolic Church. There was a history of travelling to a church gathering at Mufararikwa in Mutare District. Most of the affected children were not vaccinated. Manicaland Province had 827 cases with a total of 69 fatalities and the case fatality rate in the province was 8.3%. We therefore determined the district’s measles vaccination coverage during 2018-2022 and factors associated with contracting measles in Chimanimani District, 2022.

Methods

Study design and population

An unmatched 1:1 case-control study was conducted in Chimanimani District.

Inclusion criteria

Case: A case was any child who tested measles IgM positive or a child with fever of ≥ 37.5 °C and maculopapular skin rash lasting for three or more days with at least one of the following: cough, coryza and conjunctivitis presenting at a Chimanimani health facility, or residing in Chimanimani from July 22nd, 2022, to August 26th, 2022.

Control: Any child resident of Chimanimani who did not develop any signs and symptoms of measles and who was a neighbour to a case during the study period.

Exclusion criteria

Cases: Individuals who were unconscious or whose parents or caregivers declined to take part in the study.

Controls: Family members from the same household were excluded along with those who refused to take part.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated using Epi-Info StatCalc function. Sensitivity analysis was conducted. The Fleiss with continuity correction (Fleiss w/cc) formula was used. The sample size calculation for an unmatched 1:1 case-control study was based on: a 95% confidence level, power of 80%, caregiver lack of education factor present in 21.8% of cases and 9.1% controls. This gave a sample of 126 cases and 126 controls and a total sample size of 252, based on a study done by Pomerai et al, 2012, Zimbabwe [16].

Sampling technique

The study population were children aged 0-15 years and their caregivers. Cases were chosen at random using the lottery technique, in which each name on the line list was assigned a number on pieces of paper, which were placed in a box and randomly drawn, and the name matching that number was recruited into the research. The chosen number was replaced, and the process was repeated until the sample size was attained. The households were then derived from cases that were randomly selected from the lottery method. Only one case could be selected per household.

Controls were randomly selected and unmatched neighbours of cases residing in Chimanimani who did not suffer from measles. Only one control for one case per household was selected from the neighbours of cases so as to reduce bias. The cases-to-control ratio was 1:1.

Study tools

A pretested paper-based interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to extract data on demographic characteristics such as the age of the child, gender of the child, date of onset of rash, religion and the distance of the homestead from the health facility, and risk factors for measles such as the vaccination status. Health facility outpatient registers and line lists were used to describe the outbreak by time, place and person.

Data analysis

The descriptive analysis of measles cases was summed up by person, place and time. Data was reviewed for completeness before entry into Epi Info version 7.2.5 for analysis. All categorical factors were cross-tabulated with the outcome variable and characterized in terms of frequency and proportion in the case and control groups. To identify independent factors associated with measles infection, all explanatory variables that were associated with the outcome variable in the bivariate logistic regression at p < 0.25 were entered into a multivariable logistic regression model using the backward elimination stepwise method to control for confounding and determine the independent risk factors for contracting measles. At p-value < 0.05, adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and confidence intervals (CIs) were used to determine the strength of connections between the outcome and predictor factors.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted with permission from the Field Supervisor, Health Studies Office, Manicaland Provincial Medical Director and the Chimanimani District Medical Officer. Formal ethical approval was not obtained as the Measles outbreak was a public health emergency which required prompt implementation of control measures. Unique identifiers of the cases and controls were used to maintain confidentiality, and written informed consent was obtained from the guardians of the children.

Results

During the measles outbreak in Chimanimani District from July 4th to September 26th, 2022, there were a total of 242 cases and 25 fatalities with a total case fatality rate of 10.3%. Males accounted for more than half of the cases (64.3%, 81/126), while females were two-fifths (35.7%, 45/126).

Chimanimani District had an overall attack rate of 31 per 10 000 population. The majority of the cases were at Hotsprings village (16.3%) and followed by Nyahode (11.0%), with attack rates of 121 per 10 000 population and 50 per 10 000 population respectively. Furthermore, Nyahode had the highest mortality: it had 56% of the deaths from the overall 25 reported in Chimanimani District. Some of the villages did not have any deaths such as Hlabiso, Chisengu, Chayamiti, Ngorima and Mutsvangwa villages.

The index case’s symptoms began on July 4th, 2022, thereafter the number of cases gradually increased. The largest number of cases were on August 6th, 2022. The vaccination program began on August 23rd, 2022 at the tail end of the outbreak. The epi-curve demonstrates a propagated outbreak (Figure 1).

During the epidemic, control methods included active case search, case management, vaccination programs, and community mobilization and education. On September 7th, 2022 the outbreak was declared over.

The study had 126 cases and 126 controls. Cases had a median age of 41 months (IQR 24- 63 months) whilst the controls had a median age of 43.5 months (IQR 27- 74 months). The cases were predominantly unvaccinated, 81.0% (102/126), whilst less than half (46.0%, 58/126) of the controls were unvaccinated. Across the cases and controls, the main religion was the Apostolic religion, 82.5% (104/126) in the cases and 54.0% (68/126) amongst the controls (Tables 1 & 2).

In bivariate analysis, the significant risk factors for contracting measles were being less than 5 years of age crude odds ratio (COR) = 1.81 (95% CI= 1.05-3.10), belonging to the Apostolic religion COR = 4.03 (95% CI= 2.26 – 7.19) and being unvaccinated against measles COR = 4.98 (95% CI= 2.83-8.78). Caregivers that objected COVID-19 vaccinations were nearly five times COR = 4.80 (95% CI= 2.63-8.76) more likely to have children contracting measles than those who did not object COVID-19 vaccinations (Table 2).

Being unvaccinated Adjusted OR (AOR) = 4.06, 95% CI (2.21-7.48); being less than five years of age AOR = 2.25, 95% CI (1.24-4.08) and belonging to the Apostolic religion AOR = 278, 95% CI (1.48-5.19) were independent risk factors for contracting measles (Table 3).

Coverage of Measles Rubella (MR) vaccine in Chimanimani District from 2018 to 2022, during the COVID period and post Cyclone Idai was suboptimal. The Chimanimani District measles vaccine coverage ranged between 85 – 89% for MR1 and 70 – 78% for MR2 during the 5-year period 2018 – 2022, against the 95% district coverage target.

The district had a line list. It was updated daily and sent to the Provincial Medical Director by the District Medical Officer and District Health Information Officer. Data was analysed and disseminated during the outbreak. Village health workers were very active in identifying community cases and community deaths.

Vaccination started on August 23rd, 2022, targeting children aged six months up to 60 months. To increase acceptance and uptake of Measles vaccination among the Apostolic religion vaccine objectors, we used unmarked Ministry of Health and Child Care vehicles, plain clothed health care workers and village health workers from the Apostolic religion. Vitamin A supplementation was also conducted simultaneously. Supplemental immunization peaked on August 29th, 2022 when about 15 000 children were vaccinated. The majority of those vaccinated were at least one year old. The target was to vaccinate 74 575 children and 72 093 (96.7%) received the measles vaccine.

Discussion

The outbreak affected mostly unvaccinated children, under five years and children belonging to the Apostolic religion. Our study had a higher attack rate than that observed in South Sudan (0.4 per 1 000), Sierra Leone 24.2 per 100 000 and Ethiopia 69.9 per 10 000, [17–19] possibly due to a huge susceptible population that had not achieved herd immunity [20]. Furthermore, the district Measles Vaccine (MV) coverage was low (< 95%) in the five-year period 2018-2022. The low routine immunization coverage increased the susceptible population of non-immune children and contributed to measles resurgence due to a high susceptible population of non-immune children and no herd immunity achieved in the district [20].

Unvaccinated children were at greater odds of contracting measles. The majority of cases in this outbreak were unvaccinated children. An Ethiopian study by Belda et al in 2017 found 77% of cases occurred in unvaccinated children [22]. A Zimbabwean study done in Masvingo by Pomeria et al found that unvaccinated children had four times the odds of acquiring measles than vaccinated children [16]. Unvaccinated children have low level immunity to measles [23] yet the measles vaccine is safe, cheap and effective [24], providing lifelong immunity [21]. Routine immunization strengthening is a key strategy to prevent measles outbreaks [18].

Children that do not receive the complete Measles containing vaccine (MCV) immunization doses of the measles vaccine risk contracting measles. This was similarly observed in several studies as non-immune individuals that did not receive MCV or complete the MCV doses were more likely to contract Measles [20,22,25]. Routine vaccination must be provide high and equitable coverage with MCV 1 and MCV 2 [10]. Herd immunity is established in a population [12] by achieving a measles vaccination coverage of ≥95% with both MCV1 and MCV2 [11].

This study had cases belonging mainly to the Apostolic religion. Similar findings were observed in a Measles outbreak in Zaka, Masvingo study conducted in Zimbabwe. Their religious beliefs and practices predispose children to contracting Measles as some of them are strict vaccine objectors. Additionally, their other practices, such as putting one child with measles in a hut with other children without measles, put their children at risk. Vaccine objectors were predominately among the cases in the Zaka study [16]. Vaccine hesitancy or lack of confidence in vaccines is considered a threat to the success of vaccination programs [26].

This study found that the cold chain system in Chimanimani District was well maintained and likely that the vaccine was potent and well maintained in the distribution cold chain system. Vaccinating children in the area of the outbreak may have little impact because most susceptible individuals in the immediate vicinity of the case will probably have been exposed to the virus by the time the response is initiated. However, if it rapidly starts immediately after an outbreak is identified and well implemented, this may raise immunization levels to the point of arresting transmission. Transmission during a measles outbreak is very rapid, the incubation period is 12-14 days, so SIAs should begin as soon as possible after the identification of an outbreak. In this outbreak, SIAs commenced late, 31 days after the onset of the outbreak and lasted for 18 days (August 23rd, 2022 to October 9th, 2022). There was risk communication and community engagement to facilitate social mobilization and buy-in from the communities. In future, SIAs should commence earlier during the outbreak response.

During this outbreak, the following strategies were used to limit measles spread: (1) formation of a coordinating rapid response team, (2) isolating measles cases, (3) immunizing susceptible children and administration of Vitamin A supplementation, (4) maintaining laboratory proficiency for measles confirmation, (5) active case search in the communities (active surveillance), (6) risk communication and community engagement, (7) advocacy with the church leaders and community leaders and (8) use of Apostolic religion village health workers, plain-clothed healthcare workers, and unmarked Ministry of Health and Child Care vehicles during the outbreak.

Limitations

Recall bias by the participants could potentially have over- or under-estimated the measures of association. Misclassification of cases could also be a threat to this study and social desirability responses from the participants.

Conclusion

What is already known about the topic

- Unvaccinated children are at risk of contracting Measles.

- Herd immunity reduces the number of susceptible populations

What this study adds

- Apostolic religious practices predispose children to contracting measles.

- Use of an unmarked Ministry of Healthand Child Care vehicles, plain-clothed health workers and village health workers from the Apostolic religion are strategies to increase the uptake of measles vaccination among the vaccine objectors.

Authors´ contributions

Conceptualization: Ernest Tsarukanayi Mauwa, Owen Mugurungi, Tsitsi Patience Juru, Gibson Mandozana, Gerald Shambira, Addmore Chadambuka, Mufuta Tshimanga.

Data curation: Ernest Tsarukanayi Mauwa, Owen Mugurungi, Tsitsi Patience Juru, Gibson Mandozana, Mufuta Tshimanga.

Formal analysis: Ernest Tsarukanayi Mauwa, Tsitsi Patience Juru, Gibson Mandozana, Gerald Shambira, Addmore Chadambuka, Mufuta Tshimanga.

Investigation: Ernest Tsarukanayi Mauwa, Owen Mugurungi.

Methodology: Ernest Tsarukanayi Mauwa, Owen Mugurungi, Tsitsi Patience Juru, Gibson Mandozana, Gerald Shambira, Addmore Chadambuka, Mufuta Tshimanga.

Project administration: Ernest Tsarukanayi Mauwa, Owen Mugurungi, Tsitsi Patience Juru, Gibson Mandozana, Gerald Shambira, Mufuta Tshimanga.

Resources: Ernest Tsarukanayi Mauwa, Owen Mugurungi, Tsitsi Patience Juru, Mufuta Tshimanga.

Supervision: Owen Mugurungi, Tsitsi Patience Juru, Gibson Mandozana, Gerald Shambira, Addmore Chadambuka, Mufuta Tshimanga.

Validation: Owen Mugurungi, Tsitsi Patience Juru, Gibson Mandozana, Mufuta Tshimanga.

Writing – original draft: Ernest Tsarukanayi Mauwa, Mufuta Tshimanga, Owen Mugurungi, Tsitsi Patience Juru, Gibson Mandozana, Gerald Shambira, Addmore Chadambuka.

Writing – review & editing: Ernest Tsarukanayi Mauwa, Mufuta Tshimanga, Owen Mugurungi, Tsitsi Patience Juru, Gibson Mandozana, Gerald Shambira, Addmore Chadambuka.

| Variable | Category | Cases N=126 n (%) | Controls N=126 n (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | Median age | 41.0 (IQR 24-63) | 43.5 (IQR 27-74) | 0.027 |

| Gender of child | Female | 45 (35.7) | 56 (44.4) | 0.157 |

| Male | 81 (64.3) | 70 (55.6) | ||

| Caregiver level of education | Primary | 70 (55.6) | 60 (47.6) | 0.192 |

| Secondary | 56 (44.4) | 64 (50.8) | ||

| Tertiary | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.6) | ||

| Religion | Apostolic | 104 (82.5) | 68 (54.0) | < 0.001 |

| Pentecostal | 15 (11.9) | 20 (15.9) | ||

| Catholic | 7 (5.6) | 15 (11.9) | ||

| Traditional | 0 (0.0) | 23 (18.2) | ||

| Caregiver occupation | Peasant farmer | 97 (77.0) | 84 (66.7) | 0.016 |

| Housewife | 25 (19.8) | 40 (31.8) | ||

| Others | 4 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Teacher | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.6) | ||

| Distance to facility | < 1km | 9 (7.3) | 2 (1.6) | 0.006 |

| 1km – <3km | 30 (24.2) | 24 (19.1) | ||

| 3km – <5km | 33 (26.6) | 56 (44.4) | ||

| ≥5 km | 52 (41.9) | 44 (34.9) | ||

| Median number of people per household | 6 (IQR 4-7) | 5 (IQR 4-6) | 0.409 | |

| Median number of siblings <5 years | 2 (IQR 1-2) | 2 (IQR 2-6) | 0.580 | |

| Variable | Category | Cases N=126 n (%) | Controls N=126 n (%) | Crude Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | < 5 | 94 (74.6) | 78 (61.9) | 1.81 (1.05-3.10) | 0.030 |

| ≥ 5 | 32 (25.4) | 48 (38.1) | 1.00 | ||

| Vaccination status | No | 102 (81.0) | 58 (46.0) | 4.98 (2.83-8.78) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 24 (19.0) | 68 (54.0) | 1.00 | ||

| Religion | Apostolic | 104 (82.5) | 68 (54.0) | 4.03 (2.26-7.19) | <0.001 |

| Non Apostolic | 22 (17.5) | 58 (46.0) | 1.00 | ||

| Caregiver received COVID vaccination | No | 107 (84.9) | 68 (54.0) | 4.80 (2.63-8.76) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 19 (15.1) | 58 (46.0) | 1.00 |

| Variable | Category | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unvaccinated | Yes | 4.98 (2.83-8.78) | 4.06 (2.21-7.48) | <0.001 |

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Age < 5 years | Yes | 1.81 (1.05-3.10) | 2.25 (1.24-4.08) | 0.007 |

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Apostolic | Yes | 4.03 (2.26-7.19) | 2.78 (1.48-5.19) | 0.002 |

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

References

- Pan American Health Organization. Vaccine preventable diseases: Measles [Internet]. Washington (D.C.): Pan American Health Organization; 2022 Sep 23 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. 1 p. Available from: https://www.paho.org/en/documents/vaccine-preventable-diseases-measles Download measles-paho-eng_1.pdf

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccines and the Diseases They Prevent: Recommended vaccines by disease [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2024 Aug 10 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. [about 3 screens]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/measles/index.html

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical Overview of Measles [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2024 Jul 15 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. [about 9 screens]. Available from: htmlhttps://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/clinical-overview/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/index.html

- Dixon MG, Ferrari M, Antoni S, Li X, Portnoy A, Lambert B, Hauryski S, Hatcher C, Nedelec Y, Patel M, Alexander JP, Steulet C, Gacic-Dobo M, Rota PA, Mulders MN, Bose AS, Rosewell A, Kretsinger K, Crowcroft NS. Progress toward regional measles elimination — worldwide, 2000–2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2021 Nov 12 [cited 2025 Apr 16];70(45):1563–9. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7045a1.htm?s_cid=mm7045a1_w

- Patel MK, Antoni S, Nedelec Y, Sodha S, Menning L, Ogbuanu IU, Gacic Dobo M. The Changing Global Epidemiology of Measles, 2013–2018. J Infect Dis [Internet]. 2020 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Apr 16];222(7):1117–28. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/222/7/1117/5782424 https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa044

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Measles [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies; 2024 May 23 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. 48 p. Available from: https://epidemics.ifrc.org/volunteer/disease/measles Download Measles.pdf

- Misin A, Antonello RM, Di Bella S, Campisciano G, Zanotta N, Giacobbe DR, Comar M, Luzzati R. Measles: an overview of a re-emerging disease in children and immunocompromised patients. Microorganisms [Internet]. 2020 Feb 18 [cited 2025 Apr 16];8(2):276. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2607/8/2/276 https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8020276

- World Health Organization. Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper, May 2017. Weekly Epidemiological Record [Internet]. 20217 May 12 [ cited 2025 Apr 16]; 92(19):241–68. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/255353 Download WER9219.pdf

- Cutts FT, Ferrari MJ, Krause LK, Tatem AJ, Mosser JF. Vaccination strategies for measles control and elimination: time to strengthen local initiatives. BMC Med [Internet]. 2021 Jan 5 [cited 2025 Apr 16];19(1):2. Available from https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-020-01843-z https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01843-z

- Haddison EC, Ngwafor RA, Kagina BM. Measles outbreak investigation in a highly vaccinated community in the Centre region of Cameroon. J Public Health Afr [Internet]. 2021 Jun 18 [cited 2025 Apr 16];12(1):5. Available from: https://publichealthinafrica.org/index.php/jphia/article/view/340 https://doi.org/10.4081/jphia.2021.1775

- Dixon MG, Ferrari M, Antoni S, Li X, Portnoy A, Lambert B, Hauryski S, Hatcher C, Nedelec Y, Patel M, Alexander JP, Steulet C, Gacic-Dobo M, Rota PA, Mulders MN, Bose AS, Rosewell A, Kretsinger K, Crowcroft NS. Progress toward regional measles elimination — worldwide, 2000–2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2021 Nov 12 [cited 2025 Apr 16];70(45):1563–9. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7045a1.htm?s_cid=mm7045a1_whttps://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7045a1

- Shepherd J, Friedland G. Preventing covid-19 collateral damage. Clinical Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2020 Sep 12 [cited 2025 Apr 16];71(6):1564–7. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/71/6/1564/5858267 https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa772

- Utazi CE, Wagai J, Pannell O, Cutts FT, Rhoda DA, Ferrari MJ, Dieng B, Oteri J, Danovaro-Holliday MC, Adeniran A, Tatem AJ. Geospatial variation in measles vaccine coverage through routine and campaign strategies in Nigeria: Analysis of recent household surveys. Vaccine [Internet]. 2020 Mar 23[cited 2025 Apr 16];38(14):3062–71. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0264410X20303017 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.02.070

- Saso A, Skirrow H, Kampmann B. Impact of COVID-19 on Immunization Services for Maternal and Infant Vaccines: Results of a Survey Conducted by Imprint—The Immunising Pregnant Women and Infants Network. Vaccines [Internet]. 2020 Sep 22[cited 2025 Apr 16];8(3):556. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/8/3/556 https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines8030556

- Palo SK, Dubey S, Negi S, Sahay MR, Patel K, Swain S, Mishra BK, Bhuyan D, Kanungo S, Som M, Merta BR, Bhattacharya D, Kshatri JS, Pati S. Effective interventions to ensure MCH (Maternal and Child Health) services during pandemic related health emergencies (Zika, Ebola, and COVID-19): A systematic review. PLOS ONE [Internet]. 2022 May 10 [cited 2022 Apr16];17(5):e0268106. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0268106

- Pomerai KW, Mudyiradima RF, Gombe NT. Measles outbreak investigation in Zaka, Masvingo Province, Zimbabwe, 2010. BMC Res Notes [Internet]. 2012 Dec 19 [cited 2022 Apr 16];5(1):687. Available from: https://bmcresnotes.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1756-0500-5-687 https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-5-687

- Reliefweb. Republic of South Sudan – Measles Outbreak and Response Weekly Situation Update #9 (28 March 2023) – South Sudan [Internet]. New York (NYC); Reliefweb; 2023 Mar 30[cited 2025 Apr 16]. 6 p. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/south-sudan/republic-south-sudan-measles-outbreak-and-response-weekly-situation-update-9-28-march-2023 Measles Outbreak and Response Weekly Situation Update_Issue #9.pdf

- Bangalie A. Measles outbreak investigation in Kambia district, Sierra Leone-2018. International Journal of Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2020 Dec [cited 2025 Apr 17];101(Suppl_1):340. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1201971220316118 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.895

- Girmay A, Dadi AF. Being unvaccinated and having a contact history increased the risk of measles infection during an outbreak: a finding from measles outbreak investigation in rural district of Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2019 Apr 25 [cited 2025 Apr 17];19(1):345. Available from: https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-019-3973-8 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3973-8

- Kalil FS, Gemeda DH, Bedaso MH, Wario SK. Measles outbreak investigation in Ginnir district of Bale zone, Oromia region, Southeast Ethiopia, May 2019. Pan Afr Med J [Internet]. 2020 May 14 [cited 2022 Aug 2];36:20. Available from: http://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/36/20/full/ https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2020.36.20.21169

- Garba FM, Usman R, Umeokonkwo C, Okolocha EC, Yahaya M, AbdulQadir I, Oyeladun O, Dada AO, Balogun MS. Descriptive Epidemiology of Measles Cases in Zamfara State—Nigeria, 2012-2018. J Interv Epidemiol Public Health [Internet]. 2022 Nov 15 [cited 2025 Apr 17];5(21). Available from: https://www.afenet-journal.net/content/article/5/21/full/

- Belda K, Tegegne AA, Mersha AM, Bayenessagne MG, Hussein I, Bezabeh B. Measles outbreak investigation in Guji zone of Oromia Region, Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J [Internet]. 2017 Jun 9 [cited 2025 Apr 17];27(Suppl 2):9. Available from: http://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/series/27/2/9/full/ https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.supp.2017.27.2.10705

- Porter A, Goldfarb J. Measles: A dangerous vaccine-preventable disease returns. Cleve Clin J Med [Internet]. 2019 Jun [cited 2025 Apr 17];86(6):393–8. Available from: https://www.ccjm.org//lookup/doi/10.3949/ccjm.86a.19065 https://doi.org/10.3949/ccjm.86a.19065

- Shonhai A, Warrener L, Mangwanya D, Slibinskas R, Brown K, Brown D, Featherstone D, Samuel D. Investigation of a measles outbreak in Zimbabwe, 2010: potential of a point of care test to replace laboratory confirmation of suspected cases. Epidemiol Infect [Internet]. 2015 Dec [cited 2022 Aug 10];143(16):3442–50. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S0950268815000540/type/journal_article https://doi.org/10.1017/s0950268815000540

- Ismail AS, Aden M, Abdikarim A, Yusuf A. Risk Factors for Measles Outbreak: An Unmatched Case Control Study in Kabridahar District, Somali Regional State, Ethiopia. AJEID [Internet]. 2019 Jan 1[cited 2025 Apr 17];7:1–5. Available from: https://www.sciepub.com/ajeid/abstract/9924 https://doi.org/10.12691/ajeid-7-1-1

- Machekanyanga Z, Ndiaye S, Gerede R, Chindedza K, Chigodo C, Shibeshi ME, Goodson J, Daniel F, Zimmerman L, Kaiser R. Qualitative Assessment of Vaccination Hesitancy Among Members of the Apostolic Church of Zimbabwe: A Case Study. J Relig Health [Internet]. 2017 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Apr 17];56(5):1683–91. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10943-017-0428-7 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0428-7

Menu, Tables and Figures

Navigate this article

Tables

| Variable | Category | Cases N=126 n (%) | Controls N=126 n (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | Median age | 41.0 (IQR 24-63) | 43.5 (IQR 27-74) | 0.027 |

| Gender of child | Female | 45 (35.7) | 56 (44.4) | 0.157 |

| Male | 81 (64.3) | 70 (55.6) | ||

| Caregiver level of education | Primary | 70 (55.6) | 60 (47.6) | 0.192 |

| Secondary | 56 (44.4) | 64 (50.8) | ||

| Tertiary | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.6) | ||

| Religion | Apostolic | 104 (82.5) | 68 (54.0) | < 0.001 |

| Pentecostal | 15 (11.9) | 20 (15.9) | ||

| Catholic | 7 (5.6) | 15 (11.9) | ||

| Traditional | 0 (0.0) | 23 (18.2) | ||

| Caregiver occupation | Peasant farmer | 97 (77.0) | 84 (66.7) | 0.016 |

| Housewife | 25 (19.8) | 40 (31.8) | ||

| Others | 4 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Teacher | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.6) | ||

| Distance to facility | < 1km | 9 (7.3) | 2 (1.6) | 0.006 |

| 1km – <3km | 30 (24.2) | 24 (19.1) | ||

| 3km – <5km | 33 (26.6) | 56 (44.4) | ||

| ≥5 km | 52 (41.9) | 44 (34.9) | ||

| Median number of people per household | 6 (IQR 4-7) | 5 (IQR 4-6) | 0.409 | |

| Median number of siblings <5 years | 2 (IQR 1-2) | 2 (IQR 2-6) | 0.580 | |

| Variable | Category | Cases N=126 n (%) | Controls N=126 n (%) | Crude Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | < 5 | 94 (74.6) | 78 (61.9) | 1.81 (1.05-3.10) | 0.030 |

| ≥ 5 | 32 (25.4) | 48 (38.1) | 1.00 | ||

| Vaccination status | No | 102 (81.0) | 58 (46.0) | 4.98 (2.83-8.78) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 24 (19.0) | 68 (54.0) | 1.00 | ||

| Religion | Apostolic | 104 (82.5) | 68 (54.0) | 4.03 (2.26-7.19) | <0.001 |

| Non Apostolic | 22 (17.5) | 58 (46.0) | 1.00 | ||

| Caregiver received COVID vaccination | No | 107 (84.9) | 68 (54.0) | 4.80 (2.63-8.76) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 19 (15.1) | 58 (46.0) | 1.00 |

| Variable | Category | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unvaccinated | Yes | 4.98 (2.83-8.78) | 4.06 (2.21-7.48) | <0.001 |

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Age < 5 years | Yes | 1.81 (1.05-3.10) | 2.25 (1.24-4.08) | 0.007 |

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Apostolic | Yes | 4.03 (2.26-7.19) | 2.78 (1.48-5.19) | 0.002 |

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Figures

Figure 1: Epicurve showing the distribution of Measles cases by time, Chimanimani District, Manicaland Province, Zimbabwe, July to September 2022

Keywords

- Measles

- Outbreak

- Vaccination

- Apostolic

- Chimanimani

- Manicaland province

- Zimbabwe