Research | Open Access | Volume 8 (3): Article 51 | Published: 11 Jul 2025

Risky sexual behaviours: Predictors and perceived effect on the health of undergraduate students in a tertiary institution in Delta State, Nigeria

Menu, Tables and Figures

Navigate this article

Tables

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age of Students | ||

| 16–25 | 297 | 80.9 |

| 26–35 | 66 | 17.9 |

| 36 above | 4 | 1.1 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 131 | 35.6 |

| Female | 236 | 64.3 |

| Level of Study | ||

| 2nd year | 46 | 12.5 |

| 3rd year | 134 | 36.5 |

| 4th year | 187 | 50.9 |

| Parents’ Occupation | ||

| Business | 151 | 41.1 |

| Civil servants | 93 | 25.3 |

| Farmers | 60 | 16.3 |

| Professionals (Lawyers, Doctors, Lecturers etc) | 31 | 8.4 |

| Petty traders | 32 | 8.7 |

Table 1: Socio-demographic Characteristics of the Respondents (N=367)

| Variable | Wald | Df | P-Value | Adjusted Odd Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of Parental influence or motivation | 4.167 | 1 | 0.041 | 0.778 | 0.612 – 0.990 |

| Social media | 0.000 | 1 | 0.992 | 1.003 | 0.765 – 1.413 |

| Peer group influence | 0.028 | 1 | 0.731 | 1.035 | 0.832 – 1.264 |

| Financial hardship | 5.404 | 1 | 0.020 | 0.727 | 0.556 – 0.951 |

| Self-Satisfaction | 0.004 | 1 | 0.848 | 1.099 | 0.834 – 1.338 |

Table 2: Multivariate Analysis of Factors Promoting Risky Sexual Behaviours of Respondents (N=367)

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| I perceive the risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections (STIs) as high when engaging in risky sexual behavior | ||

| Strongly Agree | 182 | 59.2 |

| Agree | 82 | 26.7 |

| I Don’t Know | 60 | 16.3 |

| Strongly Disagree | 27 | 8.8 |

| Disagree | 16 | 5.2 |

| I believe that engaging in risky sexual behavior significantly increases the likelihood of unintended pregnancy | ||

| Strongly Agree | 155 | 50.4 |

| Agree | 108 | 35.2 |

| Neither | 60 | 16.3 |

| I Don’t Know | 32 | 10.4 |

| Strongly Disagree | 12 | 3.9 |

| My experiences with risky sexual behavior have led me to adopt safer sexual practice | ||

| Strongly Agree | 84 | 27.3 |

| Agree | 48 | 15.6 |

| I Don’t Know | 60 | 16.3 |

| Strongly Disagree | 97 | 31.6 |

| Disagree | 78 | 25.4 |

| I think social norms and peer pressure have influenced my past engagement in risky sexual behavior | ||

| Strongly Agree | 102 | 33.2 |

| Agree | 52 | 16.9 |

| I Don’t Know | 60 | 16.3 |

| Strongly Disagree | 111 | 36.1 |

| Disagree | 42 | 13.7 |

| I perceive that the long-term consequences of risky sexual behavior can be severe | ||

| Strongly Agree | 179 | 58.3 |

| Agree | 97 | 31.6 |

| I Don’t Know | 60 | 16.3 |

| Strongly Disagree | 21 | 6.8 |

| Disagree | 10 | 3.2 |

Table 3: Perceived Health Effects of Risky Sexual Behavior on Respondents (N=367)

Figures

Keywords

- Risky Sexual Behaviour

- Behavior Patterns

- Health Outcomes

- Sexual Health

- Youth Health

- Perceived Effect

- Tertiary Institution

- Sexual Risk Factors

- Public Health

- Predictors

Browne Okonkwo1, Richard Akinola Aduloju2, Christabel Nneka Ogbolu3,&, Justice Iyawa3, Otovwe Agofure4, Loveth Onuwa Okololise3

1School of Medicine and Surgery, Novena University, Ogume, Delta State, Nigeria, 2School of Dentistry, Novena University, Ogume, Delta State, Nigeria, 3Department of Public and Community Health, College of Medical and Health Sciences, Novena University, Ogume, Delta State, Nigeria, 4Department of Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, Achievers University, Owo, Ondo State, Nigeria

&Corresponding author: Christabel Nneka Ogbolu, Department of Public and Community Health, College of Medical and Health Sciences, Novena University, Ogume, Delta State, Nigeria, Email: christabelnnekaogbolu@gmail.com

Received: 10 Dec 2024, Accepted: 09 Jul 2025, Published: 11 Jul 2025

Domain: Adolescent Health, Sexual and Reproductive Health

Keywords: Risky Sexual Behavior, Behavior Patterns, Health Outcomes, Sexual Health, Youth Health, Perceived Effect, Tertiary Institution, Sexual Risk Factors, Public Health, Predictors

©Browne Okonkwo et al Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Browne Okonkwo et al Risky sexual behaviours: Predictors and perceived effect on the health of undergraduate students in a tertiary institution in Delta State, Nigeria. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8:51. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-24-02026

Abstract

Background: There are serious public health concerns associated with risky sexual conduct among undergraduate students, such as the spread of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and unwanted pregnancies. The prevalence of these practices, perceived health hazards, and contributing variables are investigated in this research of students at a tertiary institution in Delta State, Nigeria.

Methods: 367 undergraduate students participated in a cross-sectional survey. A structured questionnaire was used to gather data on sociodemographic traits, hazardous sexual activity categories, perceived health risks, and contributing variables. To find important determinants of hazardous sexual activity, the research used descriptive statistics and multivariate logistic regression.

Results: Most of the respondents (80.9%) were aged 16-25 years, with an average age of 22.3 years (standard deviation of 2.74). Females represented 64.3% of the sample. Prevalence of Risky Behaviors: Hook-ups/multiple sexual partners (67.6%), abortion (56.1%), phone sex (49.6%), oral sex (59.1%), use of strong drugs for sex (48.0%), and masturbation (46.0%) were the most common risky behaviors. Perceived Risks: Most respondents recognized the high risks of contracting sexually transmitted infections, unplanned pregnancy and perceived severe long-term consequences from hazardous sexual conduct. Influencing Elements: lack of parental influence or motivation (aOR=0.778, 95% CI=0.612-0.990), and financial hardship (aOR=0.727, 95% CI=0.556-0.951) significantly predicted their behavior.

Conclusion: A high prevalence of risky sexual behaviors among undergraduate students was revealed in this study, calling for better access to comprehensive sexual health education and reproductive health care. Financial hardship and a lack of parental influence were important protective factors, but require further investigations to understand their actual role and to guide targeted interventions to promote safer sexual practices among students and reduce associated health consequences.

Introduction

A heterogeneous population of people with a range of sexual orientations and behaviors makes up undergraduate students. Most college students engage in sexual activity, according to a study [1], and the average age of sexual initiation is between 17 and 19 years old. Generalizing sexual conduct of undergraduate students might not be appropriate as each individual is unique and may have different experiences and preferences however, we can infer using a general sample. Hookup culture is prevalent on college campuses, with many students engaging in casual sexual encounters [2]. Hookups are typically defined as sexual encounters without the anticipation of a dedicated partnership, and they can range from kissing to sexual intercourse. Research has indicated that hookup culture is more common among university attendees than among other age groups, although not all students participate in hookups [3-5].

Throughout the previous few decades, it has been observed that there has been a substantial increase in the percentage of undergraduate students who report sexual activity while at school [6], with Kenku et al, hypothetically stating that hazardous sexual behavior is greatly influenced by religion among Northern Nigerian undergraduate students [7]. Tekletsadik et al. [8] reported risky sexual behaviors to include sexual activity without condom usage, substance and alcohol use. There are consequences connected with this behavior that places the students at risk. Among these include the rise in HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), gynecological issues, a significant gap in the risk of unintended pregnancies and non-marital pregnancies, and an increase in the prevalence of abandoned babies [6,9].

In Nigeria, problems associated with adolescent sexual behaviors include a high rate of teenage pregnancy, increased rates of sexual offenses, child abandonment, school dropout, increased prevalence of STDs, and the acquisition of venereal illnesses [10,11]. Hence the study’s goal was to discuss the frequency of risky sexual behavior and its effects on undergraduate students’ health, which is essential for improving campus health services, developing supportive campus environments, influencing policy formation, and increasing student well-being and academic performance.

Methods

Study Setting and Design

The study employed a descriptive cross-sectional study design that explored the risky sexual behaviour of university students in Novena University, Ogume in addition to the health consequences of these behaviours on them. The institution is the first private university in Delta State located in Amai, Ukwuani Local Government Area. As at the time of the study the university had four colleges and 19 departments, with a total student population of 3435.

Study Population

Both male and female undergraduate students in their second through fifth years at the university comprised the study’s population.

Sample size and Sample Technique

The Taro Yamane algorithm [12] was utilised to determine the size of the sample.

$$

n = \frac{N}{1 + N(e)^2}

$$

Three key elements were used in the formula:

N: The total number of students enrolled in the most recent academic session, which was 3,435 pupils.

e: The acceptable amount of inaccuracy in the estimate, expressed as the intended margin of error or degree of precision, which is set at 5% (0.05).

n: The estimated sample size

Following the computation of n, a 10% predicted non-response rate was taken into consideration. About 398 people made up the final estimated sample size. A multi-stage sampling approach was used to select respondents across the 19 department within the institution.

- Selection of Colleges: The University were clustered into the four colleges of College of Medical and Health Sciences (CMHS), College of Management and Social Sciences (CMSS), College of Natural and Applied Sciences (CNAS), and College of Law (CL).

- Selection of Departments: The University was stratified into the 19 Departments, out of which two departments were randomly chosen from each college with multiple departments, while College of Law with one Department was purposively selected.

- Selection of Class or Years: Each of the selected Departments was stratified into second- fifth year. Only students in years 2 to 5 were included. First -year students were not selected in this study to avoid the influence of transitional challenges faced by first-year students, such as adjusting to university life, new academic expectations, and personal adjustments. This focus ensures a clearer understanding of social factors affecting students with more settled academic experiences.

- Selection of Respondents: Students were randomly selected from each of the year in each Departments. Only undergraduate students meeting the inclusion criteria participated.

- A total of 398 questionnaires were proportionally distributed across colleges and departments using this formula:

$$ \frac{\text{Total Population in a Department} \times \text{No. of Questionnaires to be Distributed in the College}}{\text{Total Population in the 2 Selected Departments}} $$

Distribution: CMHS: 164 (Nursing: 136; PCH: 28), CMSS: 129 (ISS: 53; Political Science: 76), CNAS: 103 (EPS: 78; Biological Sciences: 25) and CL: 3 (Law: 3)

Respondents were distributed evenly among four student academic years within each department. Using a random number generator, eligible students were chosen at random from departmental registers. After lectures, recruitment took place in person, and informed consent was acquired.

398 questionnaires were distributed and 367 were obtained, yielding a 92% response rate.

Method and Instrument of Data Collection

A questionnaire was the primary instrument used to collect data from the respondents. Respondents were given the questionnaire under careful observation and direction. The questionnaire was broken down into three sections: a part on sociodemographic characteristics that asked about age, gender, parents’ employment and level of education, and a piece on students’ study level. Additional parts included details on the prevalent hazardous sexual activity among students as well as the perceived health consequences of these activities.

Study Variables

Dependent: Engagement in Risky Sexual Behaviour

Independent: Socio-demographics, lack of parental Influence, financial hardship, social media, peer influence, self-satisfaction.

Data Management

Structured paper-based questionnaires were used to gather data. Statistical Product and Service Solution version 22.0 (IBM Corp SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA) was used to manually input the responses. To guarantee correctness, data were thoroughly examined and validated during entry. Prior to statistical analysis, which included descriptive statistics and logistic regression, the dataset was cleaned in SPSS by looking for duplicates, missing values, and inconsistent replies. Both descriptive statistics (frequencies & percentages) and tabular presentations were used to describe the variables. Only variables significant in the bivariate analysis were included in the logistic regression to identify independent predictors of risky sexual behaviors.

Ethical approval

The Helsinki Declaration was followed in the conduct of the research. After receiving a thorough explanation of the study, participants gave their informed consent. The Ministry of Health in Delta State provided ethical authorisation as well, with reference number HM/596/T2/85.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

A total of 367 respondents were recruited. Most respondents 297 (80.9%) fell within the 16–25 age range, 66 (17.9%) within 26-35 and 4 (1.1%) within the 36 and above age range. The respondents were 22.3 years old on average, with a standard deviation of 3.74. Majority were females 236 (64.3%) and in their fourth year of university study187 (50.9%). In addition, most of the respondents’ parents 151(41.1%) were businesspeople, followed by civil servants 93 (25.3%) and the least were petty traders 31(8.4%).

Respondents’ Dangerous Sexual Practices

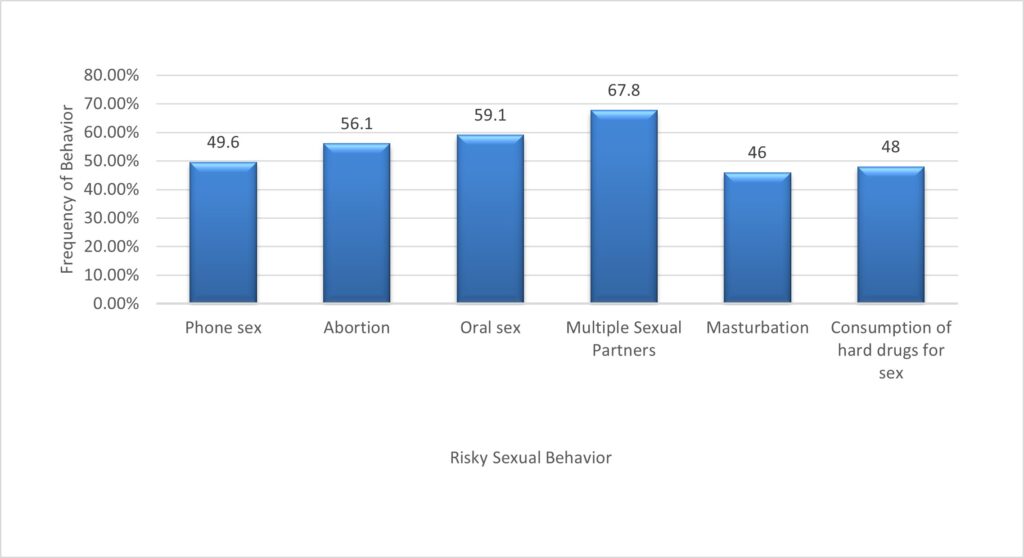

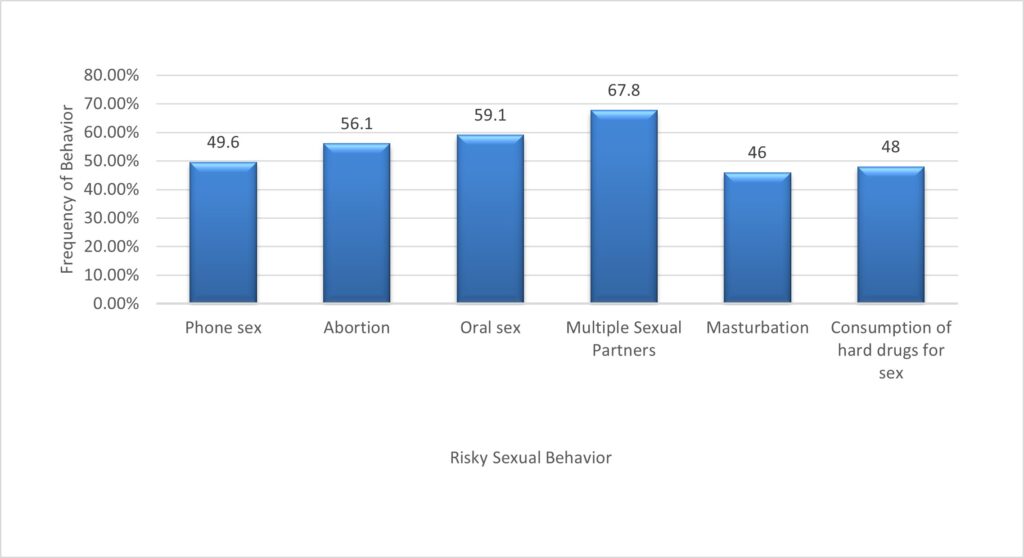

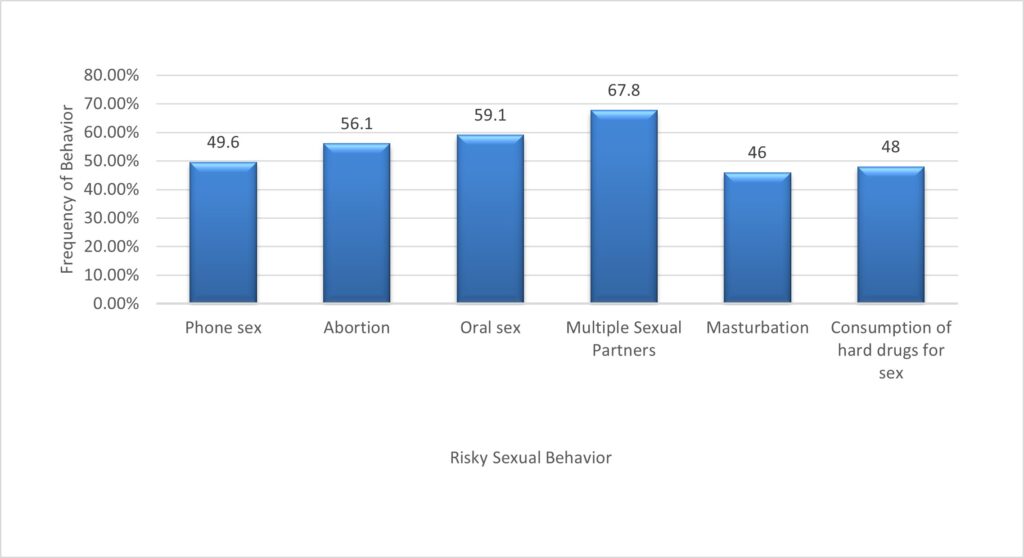

Out of 367 respondents, at least 248 students (67.6%) reported engaging in one or more forms of risky sexual behavior, with the most common being having multiple sexual partners (248, 67.6%). Abortion was also widely reported, with 206 students (56.1%) indicating they had either experienced or been involved in one. Other notable behaviors included viewing pornography (228, 62.1%), oral sex (217, 59.1%), phone sex (182, 49.6%), use of strong drugs for sex (176, 48.0%), and masturbation (169, 46.0%). Additionally, 169 students (46.0%) reported inconsistent or no condom use during sexual activity. These findings reflect a high prevalence of risky sexual practices among undergraduates, highlighting the need for targeted interventions. (Figure 1).

Factors Promoting Risky Sexual Behaviour of Respondents

To investigate the relationship between a few independent factors and hazardous sexual activity, bivariate analysis was used. Financial difficulty and a lack of parental influence or motivation were two variables that showed strong connections. The multivariate logistic regression model was then fitted with these important factors from the bivariate analysis.

Multivariate analysis revealed that both lack of parental influence or motivation (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR] = 0.778, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] = 0.612–0.990) and financial hardship (AOR = 0.727, 95% CI = 0.556–0.951) were statistically significant predictors of risky sexual behavior. However, the odds ratios were less than 1 suggesting that these factors, while significant, were associated with reduced likelihood of engaging in risky sexual behavior when adjusted for other variables in the model. (Table 2).

Respondents’ Perceived Health Effects of Dangerous Sexual Behaviour

The majority of respondents, 264/367 (85.9%), believe that there is a high risk of STDs when participating in unsafe sexual conduct. The vast majority of 263/367 people (85.6%), think that having unsafe sexual relations greatly raises the possibility of becoming pregnant unintentionally. 132/367 people (42.9%) who had previously engaged in hazardous activity have switched to safer sexual practices. 50.1% (154/367) of the participants admitted that peer pressure and societal norms had an impact on their decision to participate in hazardous sexual conduct. The majority, 276/367 (89.9%), believe that hazardous sexual conduct has serious long-term effects (Table 3).

Discussion

The majority of respondents were young individuals aged 16–25, with females outnumbering males. This aligns with findings by Jahanfar et al. and Perera et al., who reported similar gender distributions, but contrasts with Osuala et al. and Chi et al., who observed a male majority [13, 14, 15, 16]. Across various studies, cohort medians indicate that 38% to 63% of HIV infections in women occur among those aged 15-24 years, while 30% to 63% of infections in men are found in the 20-29 age group [17]. Given these trends, it is not surprising that UNAIDS reported the highest rates of newly acquired HIV infections among individuals aged 15-25 years, who account for 60% of the global HIV-positive population [17,18]. It may be necessary to modify programs designed to discourage hazardous sexual activity differently for men and women [19–21]. Most respondents’ parents were engaged in business or civil service roles—occupations associated with better access to education and health resources. This socioeconomic background may shape attitudes toward public health and academic performance. Public health activities can also be influenced by the employment of the parents; families in the civil service tend to be more stable and supportive [22, 23]. The relatively narrow age range and consistent background allow for targeted, age-specific public health and educational interventions.

According to multivariate analysis, respondents’ hazardous sexual conduct was statistically significantly predicted by financial difficulty (AOR = 0.727, 95% CI = 0.556–0.951) and a lack of parental influence or drive (AOR = 0.778, 95% CI = 0.612–0.990). Nonetheless, the fact that the odds ratios were less than one suggests that these characteristics may have had a protective impact in our study since they were linked to a decreased chance of participating in hazardous sexual conduct. Existing literature have highlighted the role of parental monitoring and communication in adolescent sexual decision-making. For example, Wang et al. and Ross-Gray reported that improved parent-child communication and supervision correlate with reduced adolescent risk behaviors [24, 25]. Similarly, Grey et al. emphasized that warmth and openness in parenting foster positive youth outcomes, while Ryan et al. demonstrated that monitoring delayed risky behaviors, including early sexual initiation [26, 27]. However, Okigbo et al. noted gender differences in the influence of paternal communication, suggesting that maternal involvement may be more impactful in shaping adolescents’ sexual behaviors [28]. These studies collectively affirm that enhancing parental engagement—especially through open, supportive communication—can serve as a key strategy for mitigating youth involvement in high-risk sexual activities. In addition, Reed et al. reported that females without financial support engaged in inconsistent condom use, while Duncan et al. found that individuals facing high financial hardship were more likely to engage in condomless anal sex and transactional sex [29, 30]. Similarly, Freedman et al. noted that many young women engaged in transactional sex out of necessity—to pay for food, healthcare, housing, or education. Morris and Rushwan added that economic pressures often restrict access to reproductive health services, increasing susceptibility to coercion and reducing the ability to practice safe sex [31,32]. Collectively, these studies affirm that financial stability is a crucial determinant of young people’s ability to make safe and informed sexual decisions.

According to the research, the majority of respondents are aware of the significant long-term implications and the high risks involved in participating in hazardous sexual conduct, such as getting an STD or becoming pregnant unintentionally. However, not all hazardous behavior experiences result in the adoption of safer habits; over 50% of respondents saw peer pressure and social norms as major impacts. This finding contrasts with the findings of Desmenu et al, and Balán et al. which indicated that despite engaging in risky behaviors, the majority of respondents had low perceptions of risk of contracting STIs [33, 34]. People who do not perceive risk may take fewer precautions, which can increase the spread of STIs [35,36]. Targeted sexual health education aims to dispel misconceptions and increase knowledge of risks [37]. Behavior changes interventions, which make use of visual aids, statistical data, and personal testimonials, can raise risk perception and promote safer behaviors.

The present study revealed that a significant proportion of respondents engaged in various high-risk sexual behaviors. Among these, having multiple sexual partners was the most commonly reported behavior, followed by oral sex, abortion, phone sex, the use of substances to enhance sexual activity, and masturbation. These findings align with previous research indicating high rates of multiple sexual partnerships among university students in Nigeria, which increases vulnerability to sexually transmitted diseases and intimate partner violence [38, 39, 40, 41]. However, the present findings slightly contrast with studies carried out in Northen Nigeria which may be related to regional differences [42,43].Abortion was notably the most commonly reported behavior in this study, with more than half (56.1%) of respondents indicating they had undergone an abortion. This percentage, which is higher than those found in other studies within the same country [44, 45], highlights increasing concerns about reproductive health risks among female students, particularly in areas with limited access to safe reproductive services. The high rate of abortion also points to deeper emotional and psychological consequences. Consistent with previous studies, abortion has been associated with increased risk of depression, anxiety, and reduced academic performance, particularly among female medical students in the same region [41, 46]. Such outcomes may contribute to long-term psychological distress, including trauma, guilt, and diminished self-confidence, which can negatively affect interpersonal relationships and academic success.

Additionally, substance use for sexual performance enhancement was reported among the respondents, a behavior strongly linked in literature to psychological dependence, depression and long-term health risks [47,48]. Drug and alcohol use among students has been shown to impair academic performance and increase the likelihood of risky sexual decisions, unplanned pregnancies, and sexually transmitted infections [49, 50]. This pattern is further supported by [51], who found that alcohol consumption heightens the probability of unsafe sexual encounters.

Collectively, these findings suggest that high-risk sexual behaviors among university students are shaped by complex socio-emotional and economic factors. Interventions should not only target sexual health education but also address mental health support, access to contraception, and substance abuse prevention.

Conclusion

This study emphasizes how common hazardous sexual activities, such as masturbation, numerous sexual partners, phone sex, oral sex, hook-ups, and abortions, are among college students. Despite a general awareness of the associated health risks such as sexually transmitted diseases and unintended pregnancies, engagement in these behaviors remains high. This calls for better access to comprehensive sexual health education and reproductive health care. Lack of parental influence and financial difficulty were found to be important protective factors and require further investigation. These results highlight the pressing need for multi-level, focused interventions. To encourage safer sexual behaviors and protect the wellbeing of young people, academic institutions, parents, and legislators must work together to address behavioral patterns and the socioeconomic factors that underlie them.

What is already known about the topic

- Studies show that a significant portion of college students engage in dangerous sexual behaviours, such as having many sexual partners, unprotected sex, and drug use during sexual activity.

- Regular sexual practices can have an impact on long-term health and socioeconomic consequences by raising the risk of STDs and unwanted pregnancies. Examples of these behaviours include hook-ups, oral sex, phone sex, drug usage, and masturbation.

- Social media may be a useful instrument for spreading positive ideas and healthy behaviours related to sexual health.

What this study adds

- Provides accurate data on the prevalence of various hazardous sexual behaviours among Nigerian undergraduate students in Delta State, allowing for comparison with other regions and the development of focused interventions.

- Documents how students perceive the health risks associated with their behaviour, showing that the majority of students are cognizant of the serious dangers associated with STIs and unintended pregnancies.

- Uses multivariate logistic regression analysis to pinpoint and measure the key elements—like peer pressure, self-satisfaction, and social media influence—that contribute to risky sexual behaviour.

Authors´ contributions

Conception and Study Design: Browne Okonkwo and Richard Akinola Aduloju. Data Collection, Entry and Clearing: Christabel Nneka Ogbolu. Data Analysis and Interpretation: Otovwe Agofure. Manuscript Drafting: Christabel Nneka Ogbolu. Manuscript Revision: Loveth Onuwa Okololise and Justice Iyawa. Christabel Nneka Ogbolu is accountable for the study’s general credibility. Before submitting the work, all writers gave their approval to its final draft.

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age of Students | ||

| 16–25 | 297 | 80.9 |

| 26–35 | 66 | 17.9 |

| 36 above | 4 | 1.1 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 131 | 35.6 |

| Female | 236 | 64.3 |

| Level of Study | ||

| 2nd year | 46 | 12.5 |

| 3rd year | 134 | 36.5 |

| 4th year | 187 | 50.9 |

| Parents’ Occupation | ||

| Business | 151 | 41.1 |

| Civil servants | 93 | 25.3 |

| Farmers | 60 | 16.3 |

| Professionals (Lawyers, Doctors, Lecturers etc) | 31 | 8.4 |

| Petty traders | 32 | 8.7 |

| Variable | Wald | Df | P-Value | Adjusted Odd Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of Parental influence or motivation | 4.167 | 1 | 0.041 | 0.778 | 0.612 – 0.990 |

| Social media | 0.000 | 1 | 0.992 | 1.003 | 0.765 – 1.413 |

| Peer group influence | 0.028 | 1 | 0.731 | 1.035 | 0.832 – 1.264 |

| Financial hardship | 5.404 | 1 | 0.020 | 0.727 | 0.556 – 0.951 |

| Self-Satisfaction | 0.004 | 1 | 0.848 | 1.099 | 0.834 – 1.338 |

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| I perceive the risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections (STIs) as high when engaging in risky sexual behavior | ||

| Strongly Agree | 182 | 59.2 |

| Agree | 82 | 26.7 |

| I Don’t Know | 60 | 16.3 |

| Strongly Disagree | 27 | 8.8 |

| Disagree | 16 | 5.2 |

| I believe that engaging in risky sexual behavior significantly increases the likelihood of unintended pregnancy | ||

| Strongly Agree | 155 | 50.4 |

| Agree | 108 | 35.2 |

| Neither | 60 | 16.3 |

| I Don’t Know | 32 | 10.4 |

| Strongly Disagree | 12 | 3.9 |

| My experiences with risky sexual behavior have led me to adopt safer sexual practice | ||

| Strongly Agree | 84 | 27.3 |

| Agree | 48 | 15.6 |

| I Don’t Know | 60 | 16.3 |

| Strongly Disagree | 97 | 31.6 |

| Disagree | 78 | 25.4 |

| I think social norms and peer pressure have influenced my past engagement in risky sexual behavior | ||

| Strongly Agree | 102 | 33.2 |

| Agree | 52 | 16.9 |

| I Don’t Know | 60 | 16.3 |

| Strongly Disagree | 111 | 36.1 |

| Disagree | 42 | 13.7 |

| I perceive that the long-term consequences of risky sexual behavior can be severe | ||

| Strongly Agree | 179 | 58.3 |

| Agree | 97 | 31.6 |

| I Don’t Know | 60 | 16.3 |

| Strongly Disagree | 21 | 6.8 |

| Disagree | 10 | 3.2 |

References

- Arogundade Ololade A. Factors influencing the sexual behaviour of undergraduate students in Adeleke university, Osun state, Nigeria. Int J Health Sci Res [Internet]. 2022 Oct 7 [cited 2025 Jul 11];12(10):9–18. Available from: https://www.ijhsr.org/IJHSR_Vol.12_Issue.10_Oct2022/IJHSR02.pdf. https://doi.org/10.52403/ijhsr.20221002.

- Wade L. American hookup: the new culture of sex on campus. 1st ed. [Internet]. Erscheinungsort nicht ermittelbar: W. W. Norton & Company, Incorporated; 2017 [cited 2025 Jul 11]. 304 p. Purchase or subscription required to access full text.

- Paul A. Making out, going all the way, or risking it: identifying individual, event, and partner-level predictors of non-penetrative, protected penetrative, and unprotected penetrative hookups. Personality and Individual Differences [Internet]. 2021 Jan 26 [cited 2025 Jul 11];174:110681. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0191886921000568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110681.

- Garcia JR, Reiber C, Massey SG, Merriwether AM. Sexual hookup culture: a review. Review of General Psychology [Internet]. 2012 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Jul 11];16(2):161–76. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1037/a0027911. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027911.

- Thorpe S, Kuperberg A. Social motivations for college hookups. Sexuality & Culture [Internet]. 2021 Oct 16 [cited 2025 Jul 11];25(2):623–45. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s12119-020-09786-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09786-6.

- Ugoji FN. Determinants of risky sexual behaviours among secondary school students in Delta State Nigeria. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth [Internet]. 2014 Jul 3 [cited 2024 Aug 4];19(3):408–18. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02673843.2012.751040. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2012.751040.

- Kenku AA, Maiwada UL, Ajodo FM. Risky sexual behaviour among new undergraduate students in Nigeria: roles of broken homes and socio-demographic characteristics. Ife Social Sciences Review [Internet]. 2023 Jun 14 [cited 2025 Jul 11];31(1):167–80. Available from: https://issr.oauife.edu.ng/index.php/issr/article/view/211.

- Tekletsadik EA, Ayisa AA, Mekonen EG, Workneh BS, Ali MS. Determinants of risky sexual behaviour among undergraduate students at the University of Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia. Epidemiol Infect [Internet]. 2021 Dec 9 [cited 2024 Aug 13];150:e2. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S0950268821002661/type/journal_article. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268821002661.

- Omisore A, Oyerinde I, Abiodun O, Aderemi Z, Adewusi T, Ajayi I, et al. Factors associated with risky sexual behaviour among sexually experienced undergraduates in Osun state, Nigeria. Afr H Sci [Internet]. 2022 Apr 29 [cited 2024 Aug 4];22(1):41–50. Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ahs/article/view/224553. https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v22i1.6.

- Alukagberie ME, Elmusharaf K, Ibrahim N, Poix S. Factors associated with adolescent pregnancy and public health interventions to address in Nigeria: a scoping review. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2023 Jun 24 [cited 2025 Jul 11];20(1):95. Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-023-01629-5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-023-01629-5.

- Ayamolowo LB, Ayamolowo SJ, Adelakun DO, Adesoji BA. Factors influencing unintended pregnancy and abortion among unmarried young people in Nigeria: a scoping review. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2024 Jun 4 [cited 2025 Jul 11];24(1):1494. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-024-19005-8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19005-8.

- Yamane T. Statistics: an introductory analysis. 2nd ed. [Internet]. New York: Harper and Row; 1967 [cited 2025 Jul 11]. Available from: https://archive.org/details/statisticsanintr0000taro. Purchase or subscription required to access full text.

- Osuala EO, Udi OA, Ogbu BN, Ojong ID. Understanding risky sexual behaviour among undergraduates. African Journal of Health, Nursing and Midwifery [Internet]. 2021 Nov 18 [cited 2025 Jul 11];4(6):60–70. Available from: https://abjournals.org/ajhnm/papers/volume-4/issue-6/understanding-risky-sexual-behaviour-among-undergraduates/. https://doi.org/10.52589/AJHNM-3GJ4LOZM.

- Chi X, Yu L, Winter S. Prevalence and correlates of sexual behaviors among university students: a study in Hefei, China. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2012 Nov 13 [cited 2024 Aug 13];12(1):972. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-12-972. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-972.

- Jahanfar S, Abedi P, Siahkal SF. Sexual behavior prevalence and its predictors among students in an American university. Sexuality & Culture [Internet]. 2021 Feb 9 [cited 2024 Aug 13];25(5):1547–63. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s12119-021-09816-x. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-021-09816-x.

- Perera UAP, Abeysena C. Prevalence and associated factors of risky sexual behaviors among undergraduate students in state universities of Western Province in Sri Lanka: a descriptive cross-sectional study. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2018 Jun 4 [cited 2025 Jul 11];15(105). Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-018-0546-z. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0546-z.

- Risher KA, Cori A, Reniers G, Marston M, Calvert C, Crampin A, Dadirai T, Dube A, Gregson S, Herbst K, Lutalo T, Moorhouse L, Mtenga B, Nabukalu D, Newton R, Price AJ, Tlhajoane M, Todd J, Tomlin K, Urassa M, Vandormael A, Fraser C, Slaymaker E, Eaton JW. Age patterns of HIV incidence in eastern and southern Africa: a modelling analysis of observational population-based cohort studies. The Lancet HIV [Internet]. 2021 Jul [cited 2025 Jul 11];8(7):e429–39. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2352301821000692. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(21)00069-2.

- Kabir M, Iliyasu Z, Abubakar I, Kabir A. Sexual behaviour among students in tertiary institutions in Kano, northern Nigeria. J Com Med and PHC [Internet]. 2005 May 19 [cited 2025 Sep 11];16(2):17–22. Available from: http://www.ajol.info/index.php/jcmphc/article/view/32408. https://doi.org/10.4314/jcmphc.v16i2.32408.

- Widman L, Choukas-Bradley S, Helms SW, Prinstein MJ. Adolescent susceptibility to peer influence in sexual situations. Journal of Adolescent Health [Internet]. 2016 Mar [cited 2025 Jul 11];58(3):323–9. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1054139X15006710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.10.253.

- Levy JK, Darmstadt GL, Ashby C, Quandt M, Halsey E, Nagar A, et al. Characteristics of successful programmes targeting gender inequality and restrictive gender norms for the health and wellbeing of children, adolescents, and young adults: a systematic review. The Lancet Global Health [Internet]. 2019 Dec 23 [cited 2025 Jul 11];8(2):e225–36. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2214109X19304954. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30495-4.

- Hiller J, Schatz K, Drexler H. Gender influence on health and risk behavior in primary prevention: a systematic review. J Public Health [Internet]. 2017 Apr 12 [cited 2025 Jul 11];25(4):339–49. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10389-017-0798-z. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-017-0798-z.

- Burusic J, Sakic M, Koprtla N. Parental perceptions of adolescent health behaviours: experiences from Croatian high schools. Health Education Journal [Internet]. 2013 Mar 26 [cited 2025 Jul 11];73(3):351–60. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0017896912471522. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896912471522.

- Atolagbe A, Oparinde O, Umaru H. Parents’ occupational background and student performance in public secondary schools in Osogbo metropolis, Osun state, Nigeria. AJIMS [Internet]. 2019 Jun 28 [cited 2024 Aug 4];1(1):13–24. Available from: https://journals.dut.ac.za/index.php/ajims/article/view/802. https://doi.org/10.51415/ajims.v1i1.802.

- Wang B, Stanton B, Deveaux L, Li X, Koci V, Lunn S. The impact of parent involvement in an effective adolescent risk reduction intervention on sexual risk communication and adolescent outcomes. AIDS Education and Prevention [Internet]. 2014 Dec [cited 2025 Jul 11];26(6):500–20. Available from: http://guilfordjournals.com/doi/10.1521/aeap.2014.26.6.500. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2014.26.6.500.

- Ross-Gray Mary. Parental supervision and monitoring and deviant adolescent behavior. [dissertation]. [Internet]. Minneapolis (MN): Walden University; 2020 May [cited 2025 Jul 11]. 154 p. Available from: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=9758&context=dissertations. Download viewcontent.cgi.pdf.

- Grey EB, Atkinson L, Chater A, Gahagan A, Tran A, Gillison FB. A systematic review of the evidence on the effect of parental communication about health and health behaviours on children’s health and wellbeing. Preventive Medicine [Internet]. 2022 Apr 8 [version of record 2022 Apr 26; cited 2025 Jul 11];159:107043. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0091743522000913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107043.

- Ryan J, Roman NV, Okwany A. The effects of parental monitoring and communication on adolescent substance use and risky sexual activity: a systematic review. TOFAMSJ [Internet]. 2015 Mar 31 [cited 2025 Jul 11];7(1):12–27. Available from: https://openfamilystudiesjournal.com/VOLUME/7/PAGE/12/. http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/1874922401507010012.

- Okigbo CC, Kabiru CW, Mumah JN, Mojola SA, Beguy D. Influence of parental factors on adolescents’ transition to first sexual intercourse in Nairobi, Kenya: a longitudinal study. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2015 Aug 21 [cited 2025 Jul 11];12(1):73. Available from: http://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-015-0069-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-015-0069-9.

- Reed E, West BS, Frost E, Salazar M, Silverman JG, McIntosh CT, Gómez MGR, Urada LA, Brouwer KC. Economic vulnerability, violence, and sexual risk factors for HIV among female sex workers in Tijuana, Mexico. AIDS and Behavior [Internet]. 2022 Apr 5 [cited 2025 Jul 11];26(10):3210–19. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10461-022-03670-0. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03670-0.

- Duncan DT, Park SH, Schneider JA, Al-Ajlouni YA, Goedel WC, Elbel B, Morganstein JG, Ransome Y, Mayer KH. Financial hardship, condomless anal intercourse and HIV risk among men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior [Internet]. 2017 Nov 3 [cited 2025 Jul 11];21(12):3478–85. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10461-017-1930-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1930-3.

- Freedman J, Rakotoarindrasata M, De Dieu Randrianasolorivo J. Analysing the economies of transactional sex amongst young people: case study of Madagascar. World Development [Internet]. 2021 Nov 15 [cited 2025 Jul 11];138:105289. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0305750X20304162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105289.

- Morris JL, Rushwan H. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health: the global challenges. Intl J Gynecology & Obste [Internet]. 2015 Feb 26 [cited 2025 Jul 11];131(S1). Available from: https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.02.006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.02.006.

- Desmennu AT, Titiloye MA, Owoaje ET. Behavioural risk factors for sexually transmitted infections and health seeking behaviour of street youths in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr H Sci [Internet]. 2018 Apr 4 [cited 2025 Jul 11];18(1):180. Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ahs/article/view/169170. https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v18i1.23.

- Balán IC, Lopez-Rios J, Dolezal C, Rael CT, Lentz C. Low sexually transmissible infection knowledge, risk perception and concern about infection among men who have sex with men and transgender women at high risk of infection. Sex Health [Internet]. 2019 Nov 8 [cited 2024 Aug 13];16(6):580. Available from: http://www.publish.csiro.au/?paper=SH18238. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH18238.

- Latt PM, Soe NN, Fairley C, Xu X, King A, Rahman R, Ong JJ, Phillips TR, Zhang L. Assessing the effectiveness of HIV/STI risk communication displays among Melbourne Sexual Health Centre attendees: a cross-sectional, observational and vignette-based study. Sex Transm Infect [Internet]. 2024 Feb 23 [cited 2025 Jul 11];100(3):158–65. Available from: https://sti.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/sextrans-2023-055978. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2023-055978.

- Clifton S, Mercer CH, Sonnenberg P, Tanton C, Field N, Gravningen K, et al. STI risk perception in the British population and how it relates to sexual behaviour and STI healthcare use: findings from a cross-sectional survey (Natsal-3). EClinicalMedicine [Internet]. 2018 Aug 12 [cited 2025 Jul 11];2–3:29–36. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S258953701830021X. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2018.08.001.

- Brayboy LM, McCoy K, Thamotharan S, Zhu E, Gil G, Houck C. The use of technology in the sexual health education especially among minority adolescent girls in the United States. Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology [Internet]. 2018 Oct [cited 2025 Jul 11];30(5):305–9. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/00001703-201810000-00004. https://doi.org/10.1097/GCO.0000000000000485.

- Adinma JIB, Umeononihu O, Echendu AD, Eke N. Sexual behaviour among students in a tertiary educational institution in southeast Nigeria. ARSci [Internet]. 2016 Aug [cited 2025 Jul 11];04(03):87–92. Available from: http://www.scirp.org/journal/doi.aspx?DOI=10.4236/arsci.2016.43010. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/arsci.2016.43010.

- Ambaw F, Mossie A, Gobena T. Sexual practices and their development pattern among Jimma university students. Ethiop J Health Sci [Internet]. 2011 Sep 12 [cited 2025 Jul 11];20(3). Available from: http://www.ajol.info/index.php/ejhs/article/view/69445. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejhs.v20i3.69445.

- Alemu MT, Dessie Y, Gobena T, Mazeingia YT, Abdu AO. Oral and anal sexual practice and associated factors among preparatory school youths in Dire Dawa city administration, Eastern Ethiopia. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2018 Nov 7 [cited 2025 Jul 11];13(11):e0206546. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0206546. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0206546.

- Manning WD, Longmore MA, Copp J, Giordano PC. The complexities of adolescent dating and sexual relationships: fluidity, meaning(s), and implications for young adults’ well-being. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev [Internet]. 2014 Jun 24 [cited 2025 Jul 11];2014(144):53–69. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cad.20060. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20060.

- Kabir M, Iliyasu Z, Abubakar I, Kabir A. Sexual behaviour among students in tertiary institutions in Kano, northern Nigeria. J Com Med and PHC [Internet]. 2005 May 19 [cited 2025 Jul 11];16(2):17–22. Available from: http://www.ajol.info/index.php/jcmphc/article/view/32408. https://doi.org/10.4314/jcmphc.v16i2.32408.

- Sabitu K, Iliyasu Z, Baba SE. Sexual behaviour and predictors of condom use among students of a Nigerian tertiary institution. Nig J Med [Internet]. 2008 Jan 14 [cited 2025 Jul 11];16(4):338–43. Available from: http://www.ajol.info/index.php/njm/article/view/37334. https://doi.org/10.4314/njm.v16i4.37334.

- Onebunne C, Bello F. Unwanted pregnancy and induced abortion among female undergraduates in University of Ibadan, Nigeria. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Jul 11];36(2):238. Available from: http://www.tjogonline.com/text.asp?2019/36/2/238/266865. http://doi.org/10.4103/TJOG.TJOG_35_19.

- Sanni TA, Elegbede OE, Durowade KA, Adewoye K, Ipinnimo TM, Alabi AK, et al. Sexual debut, sexual education, abortion, awareness and prevalence of contraceptive among female undergraduates’ students in public and private universities in Ekiti state, Nigeria. Cureus [Internet]. 2022 Aug 21 [cited 2025 Jul 11]. Available from: https://www.cureus.com/articles/105868-sexual-debut-sexual-education-abortion-awareness-and-prevalence-of-contraceptive-among-female-undergraduates-students-in-public-and-private-universities-in-ekiti-state-nigeria. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.28237.

- Nwogueze BC, Daubry TME. Exploring the prevalence of abortion and its impact on the academic performance of medical female students in Delta State University, Abraka. IJISRT [Internet]. 2020 Aug 22 [cited 2025 Jul 11];5(8):310–6. Available from: https://ijisrt.com/assets/upload/files/IJISRT20AUG021_(1).pdf.

- Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE. Prevalence and predictors of adolescent alcohol use and binge drinking in the United States. Alcohol Res Health [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2025 Jul 11];35(2):193–200. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3908711/.

- Folayan MO, Ibigbami O, El Tantawi M, Aly NM, Zuñiga RAA, Abeldaño GF, Ara E, Ellakany P, Gaffar B, Al-Khanati NM, Idigbe I, Ishabiyi AO, Khan ATA, Khalid Z, Lawal FB, Lusher J, Nzimande NP, Popoola BO, Quadri MFA, Roque M, Okeibunor JC, Brown B, Nguyen AL. Associations between mental health challenges, sexual activity, alcohol consumption, use of other psychoactive substances and use of COVID-19 preventive measures during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic by adults in Nigeria. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2023 Aug 9 [cited 2025 Jul 11];23(1):1506. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-023-16440-x. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16440-x.

- U.S. Department of Justice. College academic performance and alcohol and other drug use [Internet]. Washington (DC): U.S. Department of Justice; 2003 Jan [cited 2025 Jul 11]. 3 p. Available from: https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/college-academic-performance-and-alcohol-and-other-drug-use.

- Gómez-Núñez MI, Molla-Esparza C, Gandia Carbonell N, Badenes Ribera L. Prevalence of intoxicating substance use before or during sex among young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Sex Behav [Internet]. 2023 Mar 10 [cited 2025 Nov 11];52(6):2503–26. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10508-023-02572-z. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-023-02572-z.

- Ndagijimana E, Biracyaza E, Nzayirambaho M. Risky sexual behaviors and their associated factors within high school students from Collège Saint André in Kigali, Rwanda: an institution-based cross-sectional study. Front Reprod Health [Internet]. 2023 Mar 3 [cited 2025 Jul 11];5:1029465. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frph.2023.1029465/full. https://doi.org/10.3389/frph.2023.1029465.