Research | Open Access | Volume 8 (4): Article 96 | Published: 26 Nov 2025

Role of Tanzania Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Programme in flood disaster response in Hanang District, December 2023

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

- George Mrema

- Kokuhabwa Mukurasi

- Kristy Hayes

- Rogath Kishimba

- Emmanuel Mwakapasa

- Frank Jacob

- Danstan Ngenzi

- Ally Hussein

- Elias Bukundi

- Loveness Urio

- Nsiande Lema

- Erasto Sylvanus

- Michael Kiremeji

- Mololo Noah

- George Massawe

- Jasper Kimambo

- James Allan

- Godbless Mfuru

- Thobias Bollen

- Agnes Fridomu Njau

- Fungo Masalu

- Mohamed Kodi

- Suten Mwabulambo

- Damas Kayera

- Ernest Kyungu

- Gerald Manasseh

- Victor Muchunguzi

- Omary Ubuguyu

- Wangeci Gatei

- Mahesh Swaminathan

- Rashid Mfaume

- Elias Kwesi

- Vida Mmbaga

- Ntuli Kapologwe

- Tumaini Nagu

On Google Scholar

- George Mrema

- Kokuhabwa Mukurasi

- Kristy Hayes

- Rogath Kishimba

- Emmanuel Mwakapasa

- Frank Jacob

- Danstan Ngenzi

- Ally Hussein

- Elias Bukundi

- Loveness Urio

- Nsiande Lema

- Erasto Sylvanus

- Michael Kiremeji

- Mololo Noah

- George Massawe

- Jasper Kimambo

- James Allan

- Godbless Mfuru

- Thobias Bollen

- Agnes Fridomu Njau

- Fungo Masalu

- Mohamed Kodi

- Suten Mwabulambo

- Damas Kayera

- Ernest Kyungu

- Gerald Manasseh

- Victor Muchunguzi

- Omary Ubuguyu

- Wangeci Gatei

- Mahesh Swaminathan

- Rashid Mfaume

- Elias Kwesi

- Vida Mmbaga

- Ntuli Kapologwe

- Tumaini Nagu

Navigate this article

Tables

| Pillar/Intervention area | Ministry of Health (MOH) responders | % of MOH Total | TFELTP residents/graduates | % of TEFLTP total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coordination | 11 | 6.9% | 3 | 21.4% |

| Surveillance and Laboratory | 23 | 14.4% | 6 | 42.9% |

| Case Management | 46 | 28.8% | 0 | 0 |

| WASH | 15 | 9.4% | 3 | 21.4% |

| RCCE | 7 | 4.4% | 2 | 14.3% |

| Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPS) | 48 | 30.0% | 0 | 0 |

| Logistics | 10 | 6.3% | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 160 | 100% | 14 | 100% |

Table 1. Distribution of deployed response pillars during the flood disaster in the Hanang District Council, Manyara region, December 2023

Figures

Keywords

- Floods

- Disaster

- Epidemiology

- Tanzania

George Mrema1,2,&, Kokuhabwa Mukurasi3, Kristy Hayes3, Rogath Kishimba1,2, Emmanuel Mwakapasa1,2, Frank Jacob1, Danstan Ngenzi1,2, Ally Hussein2, Elias Bukundi4, Loveness Urio2, Nsiande Lema2, Erasto Sylvanus5, Michael Kiremeji5, Mololo Noah6, George Massawe2,4, Jasper Kimambo2,4, James Allan2,4, Godbless Mfuru2,4, Thobias Bollen2,4, Agnes Fridomu Njau2,4, Fungo Masalu2,4, Mohamed Kodi7, Suten Mwabulambo8, Damas Kayera8, Ernest Kyungu9, Gerald Manasseh2,9, Victor Muchunguzi10, Omary Ubuguyu11, Wangeci Gatei3, Mahesh Swaminathan3, Rashid Mfaume9, Elias Kwesi5, Vida Mmbaga1,2, Ntuli Kapologwe12, Tumaini Nagu13

1Epidemiology and Disease Control Section, Ministry of Health, Dodoma, Tanzania, 2 Tanzania Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program, Ministry of Health, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 3US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 4Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 5Emergency Preparedness and Response Unit, Ministry of Health, Dodoma, Tanzania, 6Prime Minister’s Office, Dodoma, Tanzania, 7Council Health Management Team, Hanang, Tanzania, 8Regional Health Management Team, Manyara, Tanzania, 9President Office, Regional Administrative Local Government, Dodoma, Tanzania, 10Mzumbe University, Morogoro, Tanzania, 11Directorate of Curative Services, Ministry of Health, Dodoma, Tanzania, 12Directorate of Preventive Services, Ministry of Health, Dodoma, Tanzania, 13Office of the Government Chief Medical Officer, Ministry of Health, Dodoma, Tanzania

&Corresponding author: George Mrema, Epidemiology and Disease Control Section, Ministry of Health, Dodoma, Tanzania. Email: drgeorgemrema@gmail.com ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0004-2612-9125

Received: 05 Apr 2025, Accepted: 25 Nov 2025, Published: 26 Nov 2025

Domain: Field Epidemiology, Climate Change

Keywords: Floods, Disaster, Epidemiology, Tanzania

©George Mrema et al. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: George Mrema et al., Role of Tanzania Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Programme in flood disaster response in Hanang District, December 2023. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8(4):96. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-25-00087

Abstract

Introduction: Natural disasters, such as floods, significantly disrupt public health systems, leading to increased risks of communicable diseases and adverse health outcomes. This study aimed to describe the contributions of residents and graduates of the Tanzania Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Programme (TFELTP) in responding to the December 2023 flooding disaster in Hanang District, Manyara Region. The disaster destroyed 1,150 households and resulted in 89 fatalities and 139 injuries.

Methods: The TFELTP team, consisting of five advanced residents and nine graduates, was deployed to the Hanang District Council on December 3, 2023. They supported four key response pillars: coordination, surveillance, Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH), and Risk Communication and Community Engagement (RCCE) through to January 5, 2024. A descriptive study was conducted, data were collected and verified data from various reports generated between December 3, 2023, and January 5, 2024. These reports included surveillance records, situation reports, active case-finding summaries, WASH assessment findings, and RCCE activity reports.

Results: The TFELTP team conducted active case-finding across 10 health facilities, identifying 350 cases of endemic diseases, primarily acute watery diarrhoea (240; 68.6%). They established alert desks for collecting and verifying information with potential human health risk from the community and a temporary emergency operation centre in a hospital located in one of the affected wards to centralize information and coordination. Training was provided to 124 healthcare workers on integrated disease surveillance and response. TFELTP, in collaboration with the Ministry of Health staff and community healthcare workers, supported WASH and RCCE interventions, including distributing 633,615 Aquatabs® to affected households and distributing 4,500 informational posters regarding disease prevention.

Conclusion: TFELTP residents and graduates played important roles in disaster response in Tanzania by complementing the government’s response and improving health security. TFELTP leveraged their expertise and skills to mitigate the health impact of the flood disaster and protect affected communities.

Introduction

Natural disasters, like earthquakes or floods, often have serious implications for public health and result in economic, political, and societal repercussions in both the short and long term [1–3]. Some of the health impacts following a flood event include heightened likelihood of spreading communicable diseases, the emergence of new diseases, disease outbreaks and an up surge in endemic illnesses[4]. This is caused by factors such as sudden population displacements, which lead to overcrowding, inadequate water and sanitation facilities, and restricted access to healthcare services [2,4]. Over the last six decades, the global climate has undergone significant transformations, with even more changes anticipated throughout the 21st century [5]. Consequences of climate change include an increase in extreme weather events, like more frequent and severe storms, heatwaves, and flooding [6]. The health impacts of disasters are often not felt equally. They tend to affect vulnerable and socioeconomically disadvantaged communities the most, which worsens existing health inequalities, increases the spread of infectious diseases, and contributes to premature deaths. This happens because disadvantaged groups usually have fewer resources, limited access to healthcare, and reduced ability to recover from disasters [7,8].

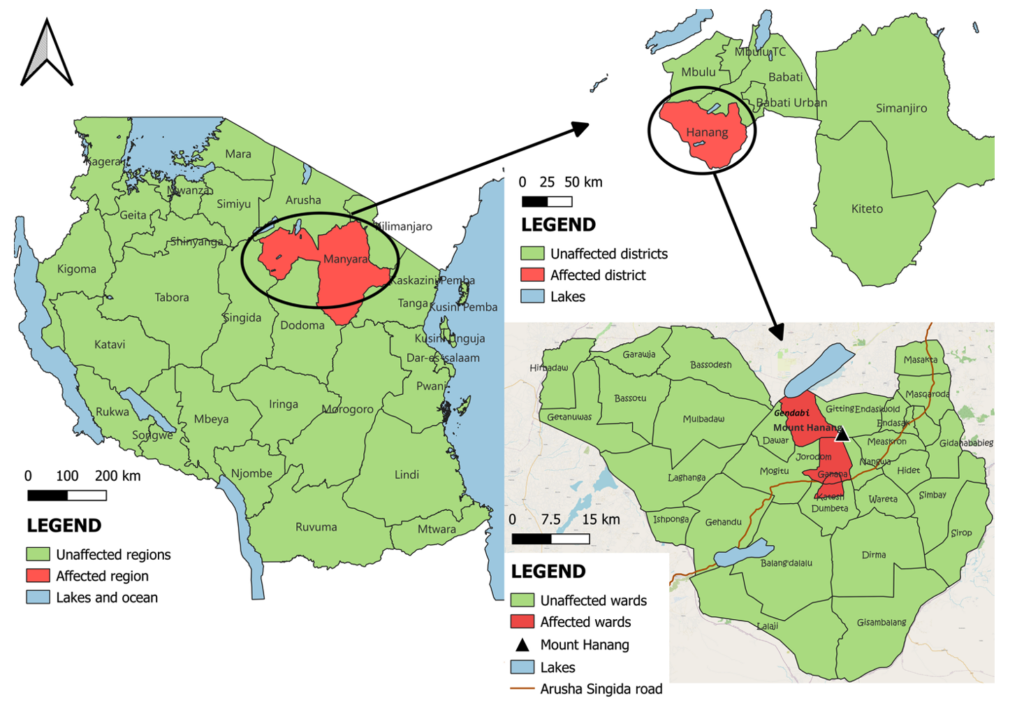

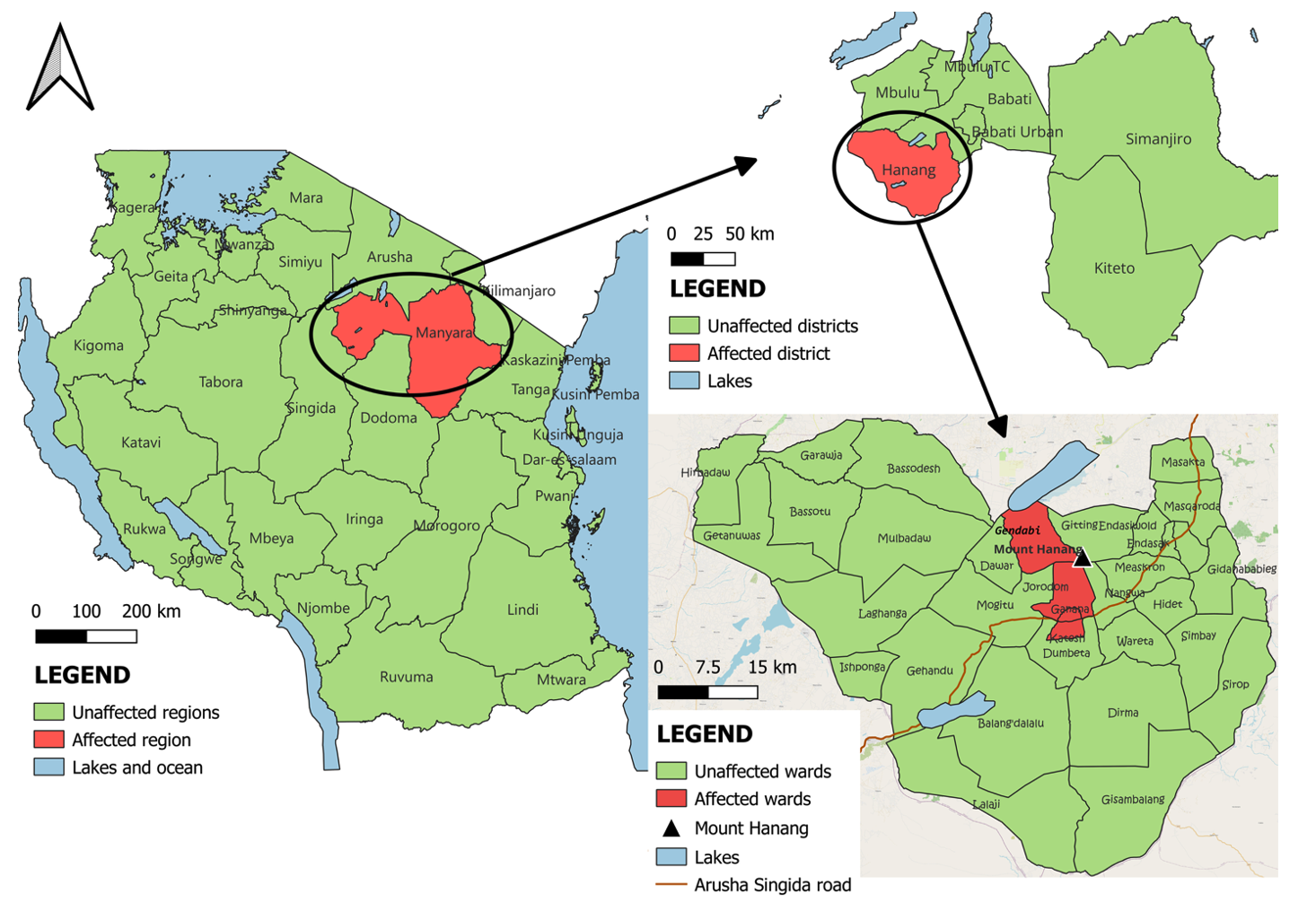

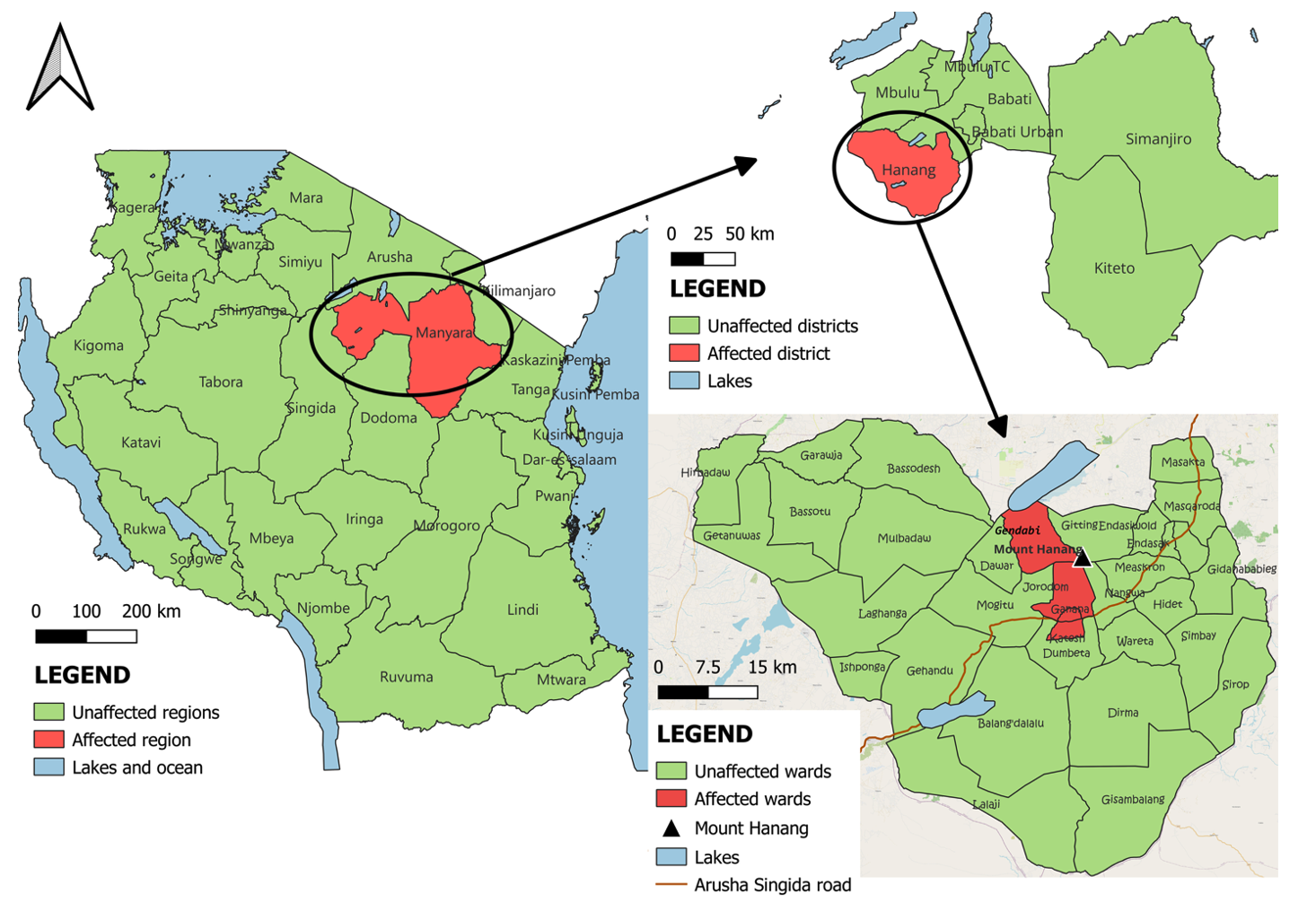

Tanzania experienced extreme weather conditions in 2023 due to the El Niño phenomenon, resulting in prolonged periods of heavy rainfall and flooding that affected agriculture, infrastructure, and livelihoods nationwide [9]. One of the most affected areas was the Hanang District Council in Manyara region, which was impacted by a severe flash flood on December 3, 2023 (Figure 1). Triggered by intense, sudden rainfall, this flash flood caused rapid water accumulation, mudslides, and the dislodgement of debris from Mount Hanang (3,420 metres above sea level). The effects were devastating, destroying 1,150 households, displacing 5,600 individuals, and resulting in 89 immediate fatalities and 139 injuries. The flood-affected four wards and prompted a major emergency response lasting for 89 days, with displacement conditions persisting for more than two weeks. On the morning of December 3, the regional commissioner notified the Ministry of Health, triggering a multisectoral response that included deployment of trained public health workforce.

Given the scale of the disaster, the advanced-level Tanzania Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Programme (TFELTP) deployed residents and graduates within 48 hours to assist in public health response. Their involvement included rapid health needs assessment, outbreak surveillance, data collection and analysis, and health risk communication with affected communities. The TFELTP engagement was aligned with the phases of disaster response, particularly the response and early recovery phases. In these phases, FELTP teams played a critical role in monitoring health conditions in temporary camps, detecting potential outbreaks, and supporting local health authorities in decision-making through evidence-based analysis.

In the face of such challenges, the need for well-trained, capable public health workers becomes even more critical. These workers must have the expertise to respond quickly and efficiently to health crises in disaster settings, where timely and coordinated interventions can make a significant difference. This need for skilled professionals in disaster response is particularly urgent in countries experiencing frequent or severe climate-related events, such as floods, which strain existing healthcare systems [10–14].

Given these persistent threats, training in epidemiology and disaster response has become an essential part of public health strategy. The Field Epidemiology Training Programme (FETP) is a residency programme established globally to train healthcare workers (HCWs) and veterinary staff whose careers are highly involved in field investigation and epidemiology to equip them with the necessary skills to collect, analyse, interpret data, and contribute to evidence-based decisions. Advanced-level FETPs are full-time two-year competency-based programme with no more than 25% of time in didactic training, and at least 75% in the field. FETP, which is currently implemented in more than 90 countries globally, is modelled after the U.S. Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) programme, founded in 1951 [10,15,16]. FETPs sometimes include laboratory trainees in their programmes and are called Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Programmes (FELTP). The Advanced-level Tanzania FELTP (TFELTP) was established in 2008 and offers two tracks leading to a Master of Science degree: Applied Epidemiology, and Epidemiology and Laboratory Management. The TFELTP approach use a holistic approach to epidemiology, giving trainees abilities that go beyond theory. TFELTP curriculum includes modules on outbreak investigation, data analysis, and coordinated response strategies equipping trainees with relevant skills not only for routine public health functions but also for emergency response, such as natural disasters [10]. In addition to the Advanced-level TFELTP, the Tanzania Ministry of Health, in collaboration with partners, introduced an FETP-Intermediate course in 2016 that runs for six months, targeting healthcare workers (HCWs) at the regional level. A 3-month FETP-Frontline course was launched in 2015 for HCWs at the district and facility levels [10,14,16,17]. As of December 2023, TFELTP had produced 1,071 graduates since its founding. This comprises 760 FETP-Frontline graduates, 101 FETP-Intermediate graduates, and 201 FETP-Advanced graduates, representing 31 Tanzanian regions.

This paper presents a descriptive study on the role of the TFELTP advanced residents and graduates in flood disaster response efforts in Hanang District, Manyara Region.

Methods

Setting

Hanang District Council is one of the six districts in the Manyara region, which is situated in the northern part of Tanzania. Mount Hanang sits in the district and is the fourth-highest mountain in Tanzania, reaching an elevation of 3,420 metres above sea level. The district has 33 wards, with the town centre located in Kateshi ward. A main road runs through Kateshi town, connecting the Arusha and Singida regions, and as of 2022 the district had an estimated population of approximately 367,000 [18]. The primary socioeconomic activities in the district include agricultural production, livestock-keeping, and fishing. The district has 38 health facilities, including one district hospital with a bed capacity of 110.

Although Hanang has largely been a rural and mountainous area, rapid and unplanned settlement expansion has occurred along natural drainage pathways. According to media reports, many homes were built in the riverbeds and watercourses that historically served as drainage routes, increasing the risk of catastrophic flooding when heavy rainfall occurred [19]. On December 3, 2023, the district experienced a severe flash flood that lasted for one day but caused extensive destruction. The most affected wards were Gendabi, Jorodom, Ganana, and Katesh.

Response team composition

The deployment of TFELTP residents and graduates during the flood response was guided by their technical expertise and the operational priorities identified by the Ministry of Health. Fellows with skills in epidemiology, laboratory diagnostics, environmental health, emergency coordination, and risk communication were prioritized. Based on these criteria and the specific needs of the flood-affected areas, residents and graduates were assigned to four of the seven response pillars- Surveillance and Laboratory, Coordination, Water Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH), and RCCE where their technical support was most critical. Deployment decisions also considered fellow availability and funding.

In total, 14 TFELTP members (9 graduates and 5 advanced-level residents) were deployed. They supported Surveillance and Laboratory (n=6), Coordination (n=3), WASH (n=3), and RCCE (n=2). Their assignments aligned with TFELTP’s core technical areas and were integrated into broader Ministry of Health response efforts that included 160 personnel across all seven national response pillars. The highest personnel needs were in Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (n=48), Case Management (n=46), and Surveillance and Laboratory (n=23), while other pillars such as WASH (n=15), Logistics (n=10), RCCE (n=7), and Coordination (n=11) were supported in collaboration with local structures and implementing partners (Table 1).

Data source and reporting

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the TFELTP’s flood response efforts, we reviewed daily activity reports submitted between December 3, 2023, and January 5, 2024. These reports, shared by TFELTP residents and graduates with the Ministry of Health (MOH), provided a detailed snapshot of their daily activities. They included surveillance records, situation reports, active case-finding reports on common endemic diseases, survey reports, WASH assessments and RCCE reports. These reports provided a structured and standardized way to track the TFELTP’s efforts that occurred in real-time. These reports were structured to capture core indicators relevant to each response pillar. For surveillance, indicators included the number of cases identified through health facility records, number and type of alerts received, the proportion of alerts verified as public health threats, and the distribution of endemic diseases over time. In WASH, indicators included the number of households assessed, number and proportion of households receiving and using Aquatabs®, and community-reported barriers to safe water practices. RCCE indicators focused on the number of posters distributed, community meetings held, CHWs and local leaders trained, and qualitative insights from focus group discussions. For Coordination, indicators included the number of situation reports produced and number of coordination meetings attended.

Reporting frequency and structure varied by response pillar, with all supported activities documented using standardized daily reporting tools. For the Coordination pillar, TFELTP residents and graduates submitted daily situation reports. In the Surveillance pillar, daily reports included alert notifications, outcomes of alert verification, and feedback from active case-finding activities conducted in health facilities. For RCCE, daily reports captured the number of people reached, the locations visited, and the key messages delivered. In the capacity-building section, reports documented the number and cadres of individuals trained each day, as well as the training sites. On average, four reports were submitted per day from each pillar, with each report tagged by location to enable geographic mapping.

Data analysis

A descriptive content analysis approach was used to systematically review and analyse the daily activity reports. The analysis was guided by the WHO Emergency Response Framework [20], with activities coded into predefined response pillars, such as surveillance, WASH, and RCCE. Each report was reviewed and coded thematically, allowing for aggregation and comparison of activities over time. Quantitative data, including the number of cases identified, trainings conducted, and distributions made, were extracted and summarized using Microsoft Excel. A trend analysis was conducted to assess the progression of activities and their correlation with public health outcomes.

Additionally, qualitative data were synthesized through a narrative approach to capture how these activities informed decision-making and shaped the overall public health response. The impact of these activities on decision-making was assessed by tracking changes in the response strategy, including the establishment of isolation facilities and follow-up investigations by the Ministry of Health. A two-sample Z-test for proportions was conducted to determine whether the differences in disease prevalence before and after the floods were statistically significant. To visualize the geographic distribution of the flood impact, QGIS (version 3.26.3) was used to map the affected areas.

Ethical considerations

This descriptive study is based on data gathered during emergency response efforts related to flooding. Permission was obtained from the Ministry of Health to analyse and publish the findings from this data. The TFELTP team worked under the authority of the Hanang District Council, with administrative clearance provided through coordination meetings with the District Medical Officer and district leadership. No personal information was collected. For these reasons, no formal ethical approval was sought.

Results

Surveillance

Active case-finding

Active case-finding was conducted for five common endemic diseases that often increase following floods and among displaced populations. These endemic diseases are acute watery diarrhoea, bloody diarrhoea/dysentery, amoebiasis, typhoid, and malaria. The team conducted a retrospective review of the health management information system (HMIS) registers across 10 health facilities in flood-affected wards from November 19 to December 17, 2023. The TFELTP team assessed the period prevalence of mentioned endemic diseases and compared record of the cases within two weeks before and after the flood.

A total of 350 patients from HMIS met the inclusion criteria of being registered within two weeks before and after the floods and having at least one of the five common endemic diseases. Using pooled data from all 10 health facilities, trends in periodic prevalence were compared for all five targeted endemic diseases before and after the floods. The most frequently reported endemic disease was acute watery diarrhoea (240; 68.6%) with 129 (36.9%) cases occurring following the floods. Although there was an increase in number of cases post floods, it was not statistically significant (P = 0.152).

As part of active case-finding, the TFELTP team designed a protocol to assess community use of antibiotics for treating diarrhoea-related diseases during the two weeks before and two weeks after the floods. The protocol was implemented across 29 community drug outlets in 20 villages, revealing a large increase in the consumption of metronidazole tablets. Two weeks prior to the flood, from November 19 to December 2, 2023, a total of 5,113 tablets were dispensed, averaging approximately 364 tablets per day. However, in the two weeks following the flood, from December 3 to December 17, 2023, dispensing surged to 20,710 tablets, averaging about 1,479 tablets per day, representing a 305% increase in utilization.

The active surveillance and its findings enabled the early detection of diarrheal disease trends, which directly informed the MOH’s decision to establish two isolation facilities for case management and further epidemiological investigations, thereby improving case containment efforts.

Alert Management

TFELTP residents and graduates established an alert desk within the Emergency Operations Centre (EOC) to enhance response. Alerts were any information that signified a potential recent risk to human health reported through community health workers (CHWs) using a toll-free number.

Alerts focused on several predefined community alerts, including clusters of individuals presenting similar symptoms from the same community, school, or workplace within a one-week period; clusters of cases involving frequent episodes of watery stool in individuals aged five years and older; and a sudden increase in sales of specific medications at local pharmacies.

TFELTP residents and graduates conducted screening of reported alerts using designed standardized form to verify if the information reported was of public health importance or if it was mild or irrelevant event. Alerts were classified as being of public health importance if they met predefined thresholds, symptoms matching epidemic-prone diseases or evidence of unusual clustering. In contrast, alerts were deemed mild or irrelevant if they involved isolated or common cases with no epidemiological linkage or public health threat. Events of public health importance were investigated. From December 8, 2023, to January 5, 2024, a total of 155 alerts were reported to the alert desk. None were determined to have the potential to represent a disease or condition of public health importance. The alert system’s operation provided real-time data that reassured response teams and helped to prioritize resource allocation, while the verification process prevented unnecessary deployment of response activities to non-urgent events.

In addition, TFELTP team in collaboration with the Ministry of Health (MOH) staff and CHWs distributed 2,500 posters to schools, markets, places of worship and health facilities in the affected wards and surrounding areas between December 12 and 21, 2023. These posters contained information on priority conditions, diseases, and symptoms that to be reported to health authorities immediately, as well as guidance on how to report such information.

Capacity-building of Healthcare Workers and Community Health Workers

During disaster response, TFELTP residents and graduates provided training to healthcare workers (HCWs) on Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) to identify priority diseases using standard case definitions. HCWs were also trained on completing cholera case investigation forms. A total of 124 HCWs from 11 facilities participated in the orientation, including 44 clinicians (35.5%), 56 nurses (45.2%), seven laboratory personnel (5.6%), and 17 individuals from other cadres (13.7%). This training improved case detection and reporting accuracy, leading to timely updates in the electronic IDSR system and supporting rapid response actions such as targeted health education, resource mobilization, and facility preparedness.

The TFELTP team also trained 90 CHWs, 33 village executive officers, and 31 religious’ leaders in Event-Based surveillance to enhance their ability to identify and report potential communicable disease events.

Coordination

TFELTP residents and graduates were involved in setting up a temporary EOC at Hanang District Hospital, which was used to coordinate information and resources in collaboration with the Ministry of Health, as well as regional and district health management teams.

They were also involved in data collection, compilation, analysis, and daily situational updates to ensure that response activities were effectively managed and communicated across all levels. This process helped inform leaders and the public about the disaster. Throughout the response, a total of 41 situation reports were developed which played a critical role in guiding the public health response. These timely reports informed the MOH and partners to implement targeted interventions, including establishing isolation units and intensifying community health education, which contributed to the containment of diarrhoea diseases.

Water sanitation and hygiene (WASH)

The TFELTP team, in collaboration with the MOH staff and CHWs, assessed and promoted the use of safe water following the destruction of WASH infrastructures by the floods. They conducted inspections of 3,958 households, evaluating both the availability and quality of toilets and handwashing facilities. This assessment laid the foundation for targeted interventions, such as the construction of sanitation facilities, the installation of handwashing facilities with soap, and community education programmes on proper hygiene practices and safe water usage.

To support the availability of safe drinking water, the TFELTP team, in collaboration with the MOH staff and CHWs, facilitated the distribution of water purification tablets for household-level treatment. In the four impacted wards, there was a total of 9,144 households. In total, 633,615 Aquatabs® were distributed to 8,738 (95.5%) households.

Moreover, residents and graduates of the TFELTP designed a protocol to gauge community awareness, attitudes, and practices regarding the use of Aquatabs®. They administered a survey to 217 respondents, identifying various barriers to the utilization of Aqua tabs. To further understand community perceptions, TFELTP organized focus group discussions with 12 village leaders and influential community members from four affected wards. These dialogues shed light on the reason the community refused the use of Aquatabs®, which was primarily due to the taste and smell of treated water.

The distribution of water purification tablets and health education materials contributed to increased community awareness and improved water safety practices, which were associated with a stabilization or decline in diarrheal case trends as observed in subsequent reports.

Risk Communication and Community Engagement (RCCE)

Two TFELTP residents and graduates were involved in community sensitization efforts on waterborne diseases such as cholera, the signs and symptoms of the disease, mode of transmission, and prevention methods. They collaborated with the Ministry of Health and regional and district health management teams to conduct community meetings and distribute 4,500 informative posters outlining the symptoms and preventive measures for diseases exacerbated by flooding.

The TFELTP team trained 45 CHWs and 20 village leaders on how to educate their communities and encourage precautions against infectious diseases. They provided information on disease symptoms, guidance for handling unvaccinated children or those who had lost their clinic cards, distributed water purification tablets, and promoted their use. Additionally, they offered psychological support to affected families through counselling sessions, where they offered emotional assistance to help individuals cope with the trauma caused by the flooding. Their focus on risk communication aimed to enhance community knowledge and promote proactive health-seeking behaviours.

These risk communication efforts led to improved community awareness and increased adoption of preventive behaviours, such as the use of water purification tablets and early symptom recognition. These changes were reflected in subsequent reports, which showed a decrease in the incidence of waterborne diseases. Furthermore, the collaborative approach with the MOH helped ensure the alignment of local and national public health strategies, supporting more targeted interventions in the affected areas.

Discussion

TFELTP residents are trained to enhance public health outcomes in a crisis. They are equipped to coordinate emergency response, conduct surveillance, and implement WASH and RCCE initiatives, thereby maximizing the resilience of the health system during an emergency. The deployment of TFELTP residents and graduates during the flood disaster in Hanang District showcased their skills in emergency response. During the flood response, active case-finding enabled real-time monitoring of endemic diseases. This led to the identification of 350 cases, mostly of acute watery diarrhoea. The findings prompted the MOH to establish two isolation facilities to manage these cases an and initiate further investigation into cases admitted to isolation facilities. Additionally, a 305% surge in over-the-counter metronidazole tablets after the flood indicated potential self-medication in the community, suggesting more widespread diarrheal cases. In response to the TFELTP findings, the MOH reinforced efforts in community education on the prevention of diarrhoea-related diseases. They emphasized to the community the importance of seeking treatment at health facilities and distributing Aquatabs® for household water treatment as well as establishing safe water point in the community. Furthermore, the establishment of an alert desk within the Emergency Operations Centre ensured that the MOH was always vigilant regarding any potential health risks in the population. Beyond this, the development of situation reports by TFELTP helped keep the public informed about the ongoing health emergency. Such activities are vital during public health emergencies, as they allow responders to provide essential epidemiological data to inform targeted interventions. Similar experiences have also been demonstrated in other studies where FELTP played a key role in implementation of surveillance and coordination activities ultimately assisting in effective control of health emergency [11–13,16].

The active involvement of TFELTP residents in capacity-building was evident throughout the disaster response. By orienting healthcare workers on IDSR and CHWs, as well as the village executive officers and religious leaders on surveillance activities, the TFELTP team ensured the continuity of surveillance of priority conditions. Similar roles of capacity-building through FETPs have been documented in other studies: study in Mozambique highlighted the role of the Mozambique FELTP during the 2019 during Cyclones Idai and Kenneth, which empowered local healthcare workers to effectively assess and address the health impacts of the disasters [11]. The experience during the first Marburg outbreak response in Tanzania highlighted the significant impact of FELTP graduates on local healthcare preparedness and response. Through targeted training sessions, these graduates successfully oriented 685 healthcare workers on essential surveillance tools. Without this enhanced capacity, the identification of cases and subsequent containment efforts would have likely been delayed, potentially resulting in a more extensive outbreak [16].

During the flood disaster response in Hanang District, WASH played a key role in mitigating health risks associated with the disruption of water and sanitation infrastructure. The TFELTP residents and graduates conducted extensive household inspections to identify gaps in sanitation and hygiene practices and address them through the distribution of water purification tablets. This approach mirrors successful strategies implemented in other regions, such as Mozambique after Cyclone Idai, where the Mozambique FELTP carried out similar assessments and interventions to prevent cholera outbreaks [11]. The successful implementation of WASH interventions by the TFELTP team highlights the importance of integrating WASH strategies into overall disaster response frameworks, thereby enhancing health security during emergencies [2,4,6].

Community engagement is a critical component of effective emergencies response. By involving local communities, we can enhance awareness, early symptom recognition, and timely access to care. The Hanang flood disaster underscores the importance of learning from past experiences in similar emergencies. For instance, FELTP graduates in Mozambique successfully controlled a cholera outbreak following Cyclone Idai in 2019 through robust community engagement [11]. Similarly, in Tanzania, FELTP graduates demonstrated the power of effective risk communication and community engagement in rapidly responding to the Marburg Virus Disease outbreak. These experiences highlight the large role that community engagement can play in building resilience and mitigating the impact of public health emergencies [16].

Although this study did not include a formal programme outcome review (POR) or a comparative evaluation of wards with and without TFELTP involvement, the retrospective analysis of disease trends before and after the flood provides useful insights into the potential impact of TFELTP supported activities. For instance, early detection of diarrheal disease trends and increased antibiotic usage informed the MOH’s decision to establish isolation centres. Additionally, community level interventions were associated with stabilization in disease reporting. Future assessments could benefit from comparing response outcomes between area supported by FETPs and those without, to further quantify their contribution to public health emergency responses.

Budget constraints limited the deployment of TFELTP residents and graduates to just 14 epidemiologists, despite the availability of 201 graduates from TFELTP advanced level. With a larger pool of trained epidemiologists, a more robust response could have been mounted, leading to earlier case identification of acute watery diarrhoea, reduced transmission, and improved health outcomes. Prioritising funding for TFELTP deployment can ensure a stronger public health response to future natural disasters, regardless of their scale and complexity.

Conclusion

TFELTP residents and graduates played a vital role in Tanzania’s flood response by enhancing surveillance, coordinating response activities, and supporting WASH and RCCE interventions. Their most valuable contribution was the early detection of diarrheal disease trends, which directly informed the Ministry of Health’s decisions on isolation and prevention efforts. These skills highlight the essential role of field epidemiologists in strengthening emergency preparedness and response.

What is already known about the topic

- Natural disasters increase the likelihood of communicable diseases and adverse health outcomes.

- FE(L)TPs globally have successfully contributed to disaster responses and public health improvements.

What this study adds

- The study highlights the contribution of TFELTP to natural disaster response.

- This study showcases how the integration of different pillars is effective in disaster response.

- The study points out the need for sustainable funding and the deployment of trained epidemiologists to enhance future public health responses to natural disasters.

- This study shows that leveraging trained personnel, such as TFELTP graduates, can significantly improve health security and response capabilities in disaster contexts.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the support and assistance of the Tanzania Ministry of Health (MOH), President Office, Regional Administration, Local Government (PORALG), Prime Minister’s Office (PMO), the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Tanzania Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Programme (TFELTP), Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS), Mzumbe University, Manyara Regional Health Management Team and Hanang Council Health Management Team.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention.

Authors´ contributions

All of the authors listed in this study made substantial contributions, and their individual contributions are outlined as follows.

Conceptualization: G.M., K.M., K.T.H., A.H., E.M., F.J., R.K., W.G., V.M.

Data Curation: G.M., E.M., F.J., R.K., D.N., E.B., E.S., M.K., G.M., J.K., J.A., G.M., T.B., A.N., F.M., M.K., S.M., D.K., E.K., G.M., V.M., N.K.

Formal Analysis: G.M., K.M., K.T.H., A.H., E.M., R.K., G.M., J.K., J.A., G.M., T.B., A.N., F.M., V.M.

Methodology: G.M., K.M., K.T.H., A.H., E.M., R.K., D.N., M.N., G.M., J.K., J.A., G.M., T.B., A.N., F.M., W.G., V.M.

Supervision: K.M., R.K., F.J., E.B., L.U., N.L., E.S., M.K., M.K., S.M., D.K., E.K., G.M., V.M., M.S., R.M., E.K., V.M., N.K., T.N.

Validation: G.M., K.M., K.T.H., A.H., E.M., R.K., F.J., D.N., E.B., L.U., N.L., E.S., M.K., M.N., G.M., J.K., J.A., G.M., T.B., A.N., F.M., M.K., S.M., D.K., E.K., G.M., V.M., M.S., R.M., E.K., V.M., N.K., T.N.

Visualization: G.M., K.M., K.T.H., A.H., E.M., R.K., F.J., D.N., E.B., L.U., N.L., E.S., M.K., M.N., G.M., J.K., J.A., G.M., T.B., A.N., F.M., M.K., S.M., D.K., E.K., G.M., V.M., M.S., R.M., E.K., V.M., N.K., T.N.

Writing – Original Draft Preparation: G.M., K.M., K.T.H., A.H., E.M., F.J., R.K., W.G., V.M.

Writing – Review & Editing: G.M., K.M., K.T.H., A.H., E.M., R.K., F.J., D.N., E.B., L.U., N.L., E.S., M.K., M.N., G.M., J.K., J.A., G.M., T.B., A.N., F.M., M.K., S.M., D.K., E.K., G.M., V.M., M.S., R.M., E.K., V.M., N.K., T.N.

| Pillar/Intervention area | Ministry of Health (MOH) responders | % of MOH Total | TFELTP residents/graduates | % of TEFLTP total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coordination | 11 | 6.9% | 3 | 21.4% |

| Surveillance and Laboratory | 23 | 14.4% | 6 | 42.9% |

| Case Management | 46 | 28.8% | 0 | 0 |

| WASH | 15 | 9.4% | 3 | 21.4% |

| RCCE | 7 | 4.4% | 2 | 14.3% |

| Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPS) | 48 | 30.0% | 0 | 0 |

| Logistics | 10 | 6.3% | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 160 | 100% | 14 | 100% |

References

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Sendai Framework Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction; 2017 [cited 2024 Aug 16]. Available from: https://www.undrr.org/terminology/disaster

- World Health Organization. Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management Framework [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2019 [cited 2025 Nov 26]. 31 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/health-emergency-and-disaster-risk-management-framework

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. What is a disaster? [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies; [cited 2024 Aug 16]. Available from: https://www.ifrc.org/en/what-we-do/disaster-management/about-disasters/what-is-a-disaster/

- World Health Organization. Communicable diseases following natural disasters: risk assessment and priority interventions [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2006 Feb 22 [cited 2025 Nov 26]. 19 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/communicable-diseases-following-natural-disasters

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Summary for policymakers. In: Climate change 2022 – mitigation of climate change [Internet]. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press; 2023 [cited 2025 Nov 26]. p. 3-48. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/9781009157926#pre2/type/book_part doi: 10.1017/9781009157926.001

- Barnett RL, Austermann J, Dyer B, Telfer MW, Barlow NLM, Boulton SJ, Carr AS, Creel RC. Constraining the contribution of the Antarctic ice sheet to last interglacial sea level. Sci Adv [Internet]. 2023 Jul 7 [cited 2025 Nov 26];9(27):eadf0198. Available from: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adf0198 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adf0198

- World Health Organization. Strengthening health resilience to climate change: technical briefing for the World Health Organization conference on health and climate change [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2015 [cited 2025 Nov 26]. 24 p. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/publications/strengthening-health-resilience-climate-change

- Stimpson JP, Rashed AL, Pandya J, Baudot EC, Whitfill J, Ortega AN. Health equity in the wake of disasters and extreme weather: evidence from an umbrella review. Health Aff Sch [Internet]. 2025 Nov 11 [cited 2025 Nov 26];3(11):qxaf207. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/healthaffairsscholar/article/doi/10.1093/haschl/qxaf207/8320417 doi: 10.1093/haschl/qxaf207

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Operation update: Tanzania floods and landslides 2023 [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies; 2024 Feb 13 [cited 2025 Nov 26]. 13 p. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/united-republic-tanzania/tanzania-africa-floods-and-landslides-2023-operation-update-1-mdrtz035

- Mmbuji P, Mukanga D, Mghamba J, Mohamed A, Mosha F, Simba A, Senga S, Moshiro C, Semali I, Rolle I, Wiktor S, McQueen S, McElroy P, Nsubuga P. The Tanzania Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program: building and transforming the public health workforce. Pan Afr Med J [Internet]. 2011 Dec 14 [cited 2025 Nov 26];10(Suppl 1):9. Available from: https://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/series/10/1/9/full/

- Baltazar CS, Rossetto EV. Mozambique Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program as responders workforce during Idai and Kenneth cyclones: a commentary. Pan Afr Med J [Internet]. 2020 Aug 11 [cited 2025 Nov 26];36:264. Available from: https://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/36/264/full doi: 10.11604/pamj.2020.36.264.21087

- López A, Cáceres VM. Central America Field Epidemiology Training Program (CA FETP): a pathway to sustainable public health capacity development. Hum Resour Health [Internet]. 2008 Dec 16 [cited 2025 Nov 26];6:27. Available from: https://human-resources-health.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1478-4491-6-27 doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-6-27

- Ramos RA, de los Reyes VC, Sucaldito MN, Tayag E. Rapid health assessments of evacuation centres in areas affected by Typhoon Haiyan. Western Pac Surveill Response J [Internet]. 2015 Nov 6 [cited 2025 Nov 26];6(Suppl 1):39-43. Available from: https://ojs.wpro.who.int/ojs/index.php/wpsar/article/view/338 doi: 10.5365/wpsar.2015.6.2.HYN_003

- Wilson K, Juya A, Abade A, Sembuche S, Leonard D, Harris J, Perkins S, Chale S, Bakari M, Mghamba J, Kohler P. Evaluation of a new field epidemiology training program intermediate course to strengthen public health workforce capacity in Tanzania. Public Health Rep [Internet]. 2021 Feb 4 [cited 2025 Nov 26];136(5):575-583. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0033354920974663 doi: 10.1177/0033354920974663

- Thacker SB. Epidemic intelligence service of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 50 years of training and service in applied epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol [Internet]. 2001 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Nov 26];154(11):985-992. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/aje/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/aje/154.11.985 doi: 10.1093/aje/154.11.985

- Hussein AK, Kishimba RS, Simba AA, Urio LJ, Lema NA, Mmbaga VM, Mutayoba BK, Malugu NE, Leonard D, Hokororo J, Kelly ME, Paschal A, Ngenzi D, Hellar JA, Kauki GC, Saguti GE, Yoti Z, Mukurasi KI, Mponela M, Mgomella GS, Gatei W, Kaniki I, Swaminathan M, Kwesi EM, Nagu TJ. Tanzania’s first Marburg viral disease outbreak response: describing the roles of FELTP graduates and residents. PLOS Glob Public Health [Internet]. 2024 May 29 [cited 2025 Nov 26];4(5):e0003189. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003189 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0003189

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Building the cadre of disease detectives in Tanzania [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2022 [cited 2025 Nov 26]. Available from: https://archive.cdc.gov/#/details?url=https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/stories/2022/disease-detectives-tanzania.html

- Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics. The 2022 population and housing census: administrative units population distribution report. Volume 1A [Internet]. Dar es Salaam (Tanzania): National Bureau of Statistics; 2022 Dec [cited 2025 Nov 26]. 259 p. Available from: https://www.nbs.go.tz/nbs/takwimu/Census2022/Administrative_units_Population_Distribution_Report_Tanzania_volume1a.pdf

- Ubwani Z. Hanang floods: a wake-up call for disaster preparedness [Internet]. Dar es Salaam (Tanzania): The Citizen; 2023 Dec 26 [cited 2025 Nov 26]. Available from: https://www.thecitizen.co.tz/tanzania/news/national/hanang-floods-a-wake-up-call-for-disaster-preparedness-4474252

- World Health Organization. Emergency Response Framework [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2024 [cited 2025 Nov 26]. 52 p. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/375964/9789240058064-eng.pdf?sequence=1