Research![]() | Volume 8, Article 23, 18 Apr 2025

| Volume 8, Article 23, 18 Apr 2025

The Adolescent Girls and Young Women Initiative in Zimbabwe, 2018-2021: A secondary data analysis

Godwin Choga1, Owen Mugurungi2, Tsitsi Patience Juru1, Gibson Mandozana1, Addmore Chadambuka1,&, Notion Tafara Gombe1,3, Gerald Shambira1, Mufuta Tshimanga1

1University of Zimbabwe, Department of Primary Health Care Sciences: Family Medicine, Global and Public Health Unit, Harare, Zimbabwe, 2AIDS and TB and Unit, Ministry of Health and Child Care, Harare, Zimbabwe, 3African Field Epidemiology Network, Harare, Zimbabwe

&Corresponding author: Addmore Chadambuka, University of Zimbabwe, Department of Primary Health Care Sciences: Family Medicine, Global and Public Health Unit, Harare, Zimbabwe, Email: achadambuka1@yahoo.co.uk, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2407-1172

Received: 05 Dec 2024, Accepted: 03 Apr 2025, Published: 17 Apr 2025

Domain: Adolescent Health, Reproductive Health, School Health

Keywords: Adolescent girls, Young women, HIV/AIDS education, HIV care, Zimbabwe

©Godwin Choga et al Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Godwin Choga et al The Adolescent Girls and Young Women Initiative in Zimbabwe, 2018-2021: A Secondary Data Analysis. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8:23. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph-d-24-02006

Abstract

Background: In Zimbabwe, the annual incidence of HIV among adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) is 9.5 times that of adolescent boys and young men. There is an AGYW initiative aimed at reducing new HIV infections among AGYW in Zimbabwe. We analyzed the AGYW initiative data for Zimbabwe to determine trends in AGYW reached with HIV/AIDS education, reasons for dropping out of school, and access to clinical services.

Methods: An analysis of the 2018-2021 AGYW initiative data from the National AIDS Council database was conducted. Variables analyzed were proportion of girls in school reached with HIV/AIDS education, reasons for girls dropping out of school, and proportion of AGYW accessing clinical services. Excel was used to generate frequencies, proportions, and trends. Chi-square test for significance was conducted.

Results: The proportion of girls in school reached with HIV/AIDS education reduced from 53% (1012568/ 1910511) in 2018 to 51% (991062/1943273) in 2019, to 28% (565612/2020137) in 2020 and increased to 37% (743675/2009894) in 2021 (χ2 202157.71, p<0.001). The major reason for school dropouts was financial problems, contributing 82% and 49% of dropouts among primary and secondary school girls respectively. In Mazowe District of Zimbabwe in 2021, the majority of AGYW accessed clinical services they were referred for, with 97.5% (828/849) accessing pre-exposure prophylaxis, and 97.4% (3793/3894) being screened for sexually transmitted illnesses.

Conclusion: HIV/AIDS education coverage for girls in school substantially reduced when Covid 19 emerged. The major reason for school dropouts was financial constraints. Access to clinical services by AGYW was high.

Introduction

The 2020 Global AIDS update report states that new HIV infections have decreased by 23% from the 2010 data, with Eastern and Southern Africa seeing the largest decrease of 38% [1] Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Global AIDS Update| 2020: Seizing the moment - Tackling entrenched inequalities to end epidemics [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2020 [cited 2025 Apr 4]; 380 p. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2020_global-aids-report_en.pdf Download 2020_global-aids-report_en.pdf . However, the risk of developing new infections remains higher for adolescent girls and young women (AGYW). Every day, approximately 1000 teenagers and young women contract HIV throughout the world [2] The Global Fund. Technical Brief: Gender Equity [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): The Global Fund; 2019 Oct [cited 2025 Apr 4]. 22 p. Available from: https://eecaplatform.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/core_gender_infonote_en.pdf Download core_gender_infonote_en.pdf . In sub-Saharan Africa, AGYW accounts for 74 % of all new HIV infections among all adolescents [3] Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. UNAIDS DATA 2021 [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AID; 2021 [cited 2025 Apr 7]. 464 p. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC3032_AIDS_Data_book_2021_En.pdf Download JC3032_AIDS_Data_book_2021_En.pdf . In Zimbabwe, the annual incidence of HIV among the AGYW is 9.5 times higher than that among adolescent boys and young men [4] Ministry of Health and Child Care (ZIM). Zimbabwe Population-based HIV Impact Assessment 2020 (ZIMPHIA 2020) [Internet]. Harare (Zimbabwe): Ministry of Health and Child Care; 2021 Dec [cited 2025 Apr 4]. 207 p. Available from: https://phia.icap.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/010923_ZIMPHIA2020-interactive-versionFinal.pdf Download 010923_ZIMPHIA2020-interactive-versionFinal.pdf .

The majority of AGYWs in Southern Africa reside in neighborhoods with weak socioeconomic foundations and socially imposed gender disparities [5] United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF ESARO). Assessing the Vulnerability and Risks of Adolescent Girls and Young Women in Eastern and Southern Africa: A Review of the Tools in Use [Internet]. Nairobi (Kenya): United Nations Children’s Fund(UNICEF ESARO); 2019 Jun [cited 2025 Apr 4]. 30 p. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/esa/media/9146/file/UNICEF-ESARO-AGYW-RV-Assessment-2021.pdf Download UNICEF-ESARO-AGYW-RV-Assessment-2021.pdf . Factors, such as poverty, discriminatory cultural norms, gender-based violence, and poor education influence their susceptibility to HIV infections [3] Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. UNAIDS DATA 2021 [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AID; 2021 [cited 2025 Apr 7]. 464 p. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC3032_AIDS_Data_book_2021_En.pdf Download JC3032_AIDS_Data_book_2021_En.pdf . There are calls for countries to come up with high-impact interventions to reduce the incidence of HIV among the AGYW. This can only be achieved if proposed interventions address the gender inequalities and the socio-cultural practices in the communities that negatively affect the AGYW, making them more vulnerable to acquiring HIV [2] The Global Fund. Technical Brief: Gender Equity [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): The Global Fund; 2019 Oct [cited 2025 Apr 4]. 22 p. Available from: https://eecaplatform.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/core_gender_infonote_en.pdf Download core_gender_infonote_en.pdf .

The Global Fund, through its 2017 – 2022 strategy, “Investing to end Epidemics” supported AGYW programs in 13 African countries including Zimbabwe with a goal of reducing new HIV infections in females aged 15-24 years by 58% by 2022 [6] The Global Fund. THE GLOBAL FUND MEASUREMENT FRAMEWORK FOR ADOLESCENTS GIRLS and YOUNG WOMEN PROGRAMS [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): The Global Fund; 2018 Sep [cited 2025 Apr 4]. 36 p. Available from: https://resources.theglobalfund.org/media/13924/cr_me-adolescents-girls-young-women-programs_framework_en.pdf Download cr_me-adolescents-girls-young-women-programs_framework_en.pdf . In Zimbabwe, 21 out of the 63 districts are being supported by the Global Fund AGYW funds and an additional four districts are supported by the Global Fund Modified DREAMS (Determined, Resilient, Empowered, AIDS-free, Mentored and Safe) program. The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) fund is also supporting the AGWY Initiative through the DREAMS project. In Zimbabwe, the PEPFAR DREAMS project is being implemented in 16 districts. The AGYW programs in the districts which are not being supported by Global Fund and PEPFAR are funded by the Zimbabwe National AIDS Council (NAC) through the National AIDS Trust Fund. The programs being implemented by NAC and all the partners are meant to complement each other in the fight against new HIV infections in AGYW. NAC coordinates the AGYW programs through its District AIDS Coordinators (DACs) who are present in all the districts in Zimbabwe. Implementing partners in the districts report monthly to NAC through a National AIDS reporting form and narrative reports which are submitted to the DACs. The DACs then consolidate the data and send it to the provincial and then to the national level.

According to the Zimbabwe Population-based HIV Impact Survey of 2020 (ZIMPHIA 2020), 77.2% of AGYW living with HIV knew their status and 95.1% of those who knew their status were on antiretroviral therapy (ART). Among those AGYW who were on ART, 85.3% achieved viral suppression. The annual incidence of HIV among the AGYW was 0.76%, compared to 0.08% among adolescent boys and young men [4] Ministry of Health and Child Care (ZIM). Zimbabwe Population-based HIV Impact Assessment 2020 (ZIMPHIA 2020) [Internet]. Harare (Zimbabwe): Ministry of Health and Child Care; 2021 Dec [cited 2025 Apr 4]. 207 p. Available from: https://phia.icap.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/010923_ZIMPHIA2020-interactive-versionFinal.pdf Download . This reflects a huge difference in HIV infection rates between young males and females. There is no evidence of information sharing between the NAC and the Ministry of Health and Child Care to inform HIV prevention programs for the AGYW. To evaluate the impact of the HIV intervention packages for AGYW, there should be a platform for data use for action [6] The Global Fund. THE GLOBAL FUND MEASUREMENT FRAMEWORK FOR ADOLESCENTS GIRLS and YOUNG WOMEN PROGRAMS [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): The Global Fund; 2018 Sep [cited 2025 Apr 4]. 36 p. Available from: https://resources.theglobalfund.org/media/13924/cr_me-adolescents-girls-young-women-programs_framework_en.pdf Download cr_me-adolescents-girls-young-women-programs_framework_en.pdf . We analyzed the AGYW Initiative dataset at NAC in order to inform policy and come up with recommendations to improve the performance of the AGYW initiative.

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted in Zimbabwe which is located in Southern Africa. Zimbabwe has 10 provinces and 63 districts and has an agriculture-based economy. The country has a population of approximately 15.2 million people and 16.2% of the population are AGYW [7] Zimbabwe National Statistic Agency. 2022 Population and Housing Census Preliminary Results [Internet]. Harare (Zimbabwe): Zimbabwe National Statistic Agency; 2022 [cited 2025 Apr 4]. 159 p. Available from: https://zimbabwe.unfpa.org/en/publications/2022-population-and-housing-census-preliminary-results Download 2022_population_and_housing_census_preliminary_report_on_population_figures.pdf . It is estimated that 12.9% of the population of Zimbabwe is living with HIV [8] Ministry of Health and Child Care (ZIM). ZIMBABWE NATIONAL HIV AND AIDS STRATEGIC PLAN 2021 – 2025 [Internet]. Harare (Zimbabwe): Ministry of Health and Child Care; 2020 Jul [cited 2025 Apr 7]. 109 p. Available from: https://www.nac.org.zw/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/ZIMBABWE-NATIONAL-HIV-STATEGIC-PLAN_2021-2025-1.pdf Download ZIMBABWE-NATIONAL-HIV-STATEGIC-PLAN_2021-2025-1.pdf .

Study design

A cross-sectional study was conducted using secondary data for the adolescent girls and young women initiative program for Zimbabwe for the period 2018 to 2021. The datasets contained aggregated data so analytic studies could not be conducted.

Data sources

The data for the girls in school, girls out of school, and youths in tertiary institutions reached through HIV/AIDS life skills education, girls dropping out of school and for the HIV cascade was obtained from the AGYW Initiative dataset which was resident at the NAC. The data was in the form of an Excel spreadsheet.

The targets for the girls in school were obtained from the Zimbabwe National AIDS Strategy (ZNASP) and the Ministry of Education school enrolment data whilst that for the girls out of school was obtained from the ZNASP.

The data for the number of AGYW referred for clinical services and those who accessed the clinical services were obtained from the AGYW Initiative dataset for Mazowe District one of the high burden districts concerning HIV incidence in Zimbabwe [8] Ministry of Health and Child Care (ZIM). ZIMBABWE NATIONAL HIV AND AIDS STRATEGIC PLAN 2021 – 2025 [Internet]. Harare (Zimbabwe): Ministry of Health and Child Care; 2020 Jul [cited 2025 Apr 7]. 109 p. Available from: https://www.nac.org.zw/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/ZIMBABWE-NATIONAL-HIV-STATEGIC-PLAN_2021-2025-1.pdf Download ZIMBABWE-NATIONAL-HIV-STATEGIC-PLAN_2021-2025-1.pdf . Among the high-burdened districts, the Mazowe District data was the most complete in relation to the services that we wanted to assess. The clinical services analyzed were pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), screening for sexually transmitted illnesses (STI), gender-based violence (GBV) related services, family planning, HIV testing, and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) services.

Study variables

The proportion of girls in school reached through HIV/AIDS life skills education was calculated by dividing the number of girls in school reached through HIV/AIDS life skills education by the ZNASP target and by the actual number of girls enrolled in schools. The proportion of girls out of school reached through comprehensive sexuality HIV/AIDS education was calculated by dividing the number of girls out of school reached through comprehensive sexuality HIV/AIDS education by the estimated number of girls out of school in that respective year. The proportion of girls dropping out of school was calculated by dividing the number of girls dropping out of school by the number of girls enrolled in schools in that respective year. The proportion of AGYW who accessed clinical services was calculated by dividing the number of AGYW who accessed a clinical service by the number of AGYW referred for that respective clinical service (Table 1).

Data analysis

The Excel spreadsheet was used to conduct a univariate analysis to generate frequencies and proportions and generate graphs and tables. A trend analysis for the period 2018 to 2021 was done for the girls in school and girls out of school reached through HIV/AIDS life skills education, AGYW reached with HIV/AIDS education, and girls dropping out of school. A Chi-square (χ2) test for trends was used to test for significance in the trend analysis with the p-value set at 5% significance level. Bar graphs were used to present the data for the percentage of girls dropping out of school by province, reasons for dropping out of school, and the HIV testing cascade. The data for the access to clinical services by the AGYW was presented in a table.

Data quality

The data in the Excel sheets was compared with data on the hard copies submitted by the districts to ensure that there were no data-capturing errors. The quarterly data was checked for outliers. The data for the year 2021 was noted to have been captured as cumulative figures for the respective quarters of the year whilst the data for the years 2018 to 2020 were captured as the actual figures for each quarter. This was verified with the Monitoring and Evaluation Officers from the National AIDS Council. The quarterly data for the year 2021 was recalculated by computing the difference between the reported figures for the quarter and the reported figures for the previous quarter. To assess access to clinical services, we analyzed only the 2021 data because it was the most complete dataset. A more complete dataset would inform policy and decision-making better.

Permission and ethical considerations

Permission and ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Secretary of the Ministry of Health and Child Care and the University of Zimbabwe Health Studies Office (Approval No. HSO/13/003). The Chief Executive Officer of the National AIDS Council also approved the use of the AGYW Initiative dataset for the study. The dataset contained aggregate data and there was no patient-level information. No human subjects were interviewed.

Results

HIV/AIDS life skills education

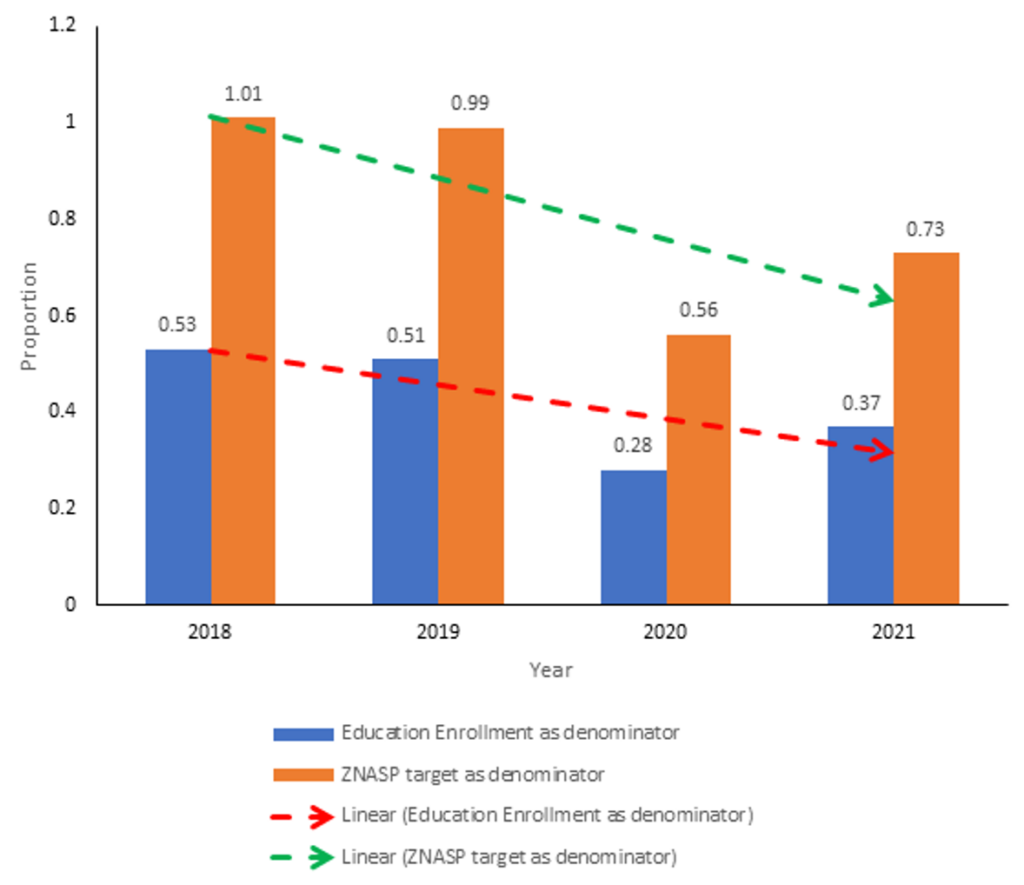

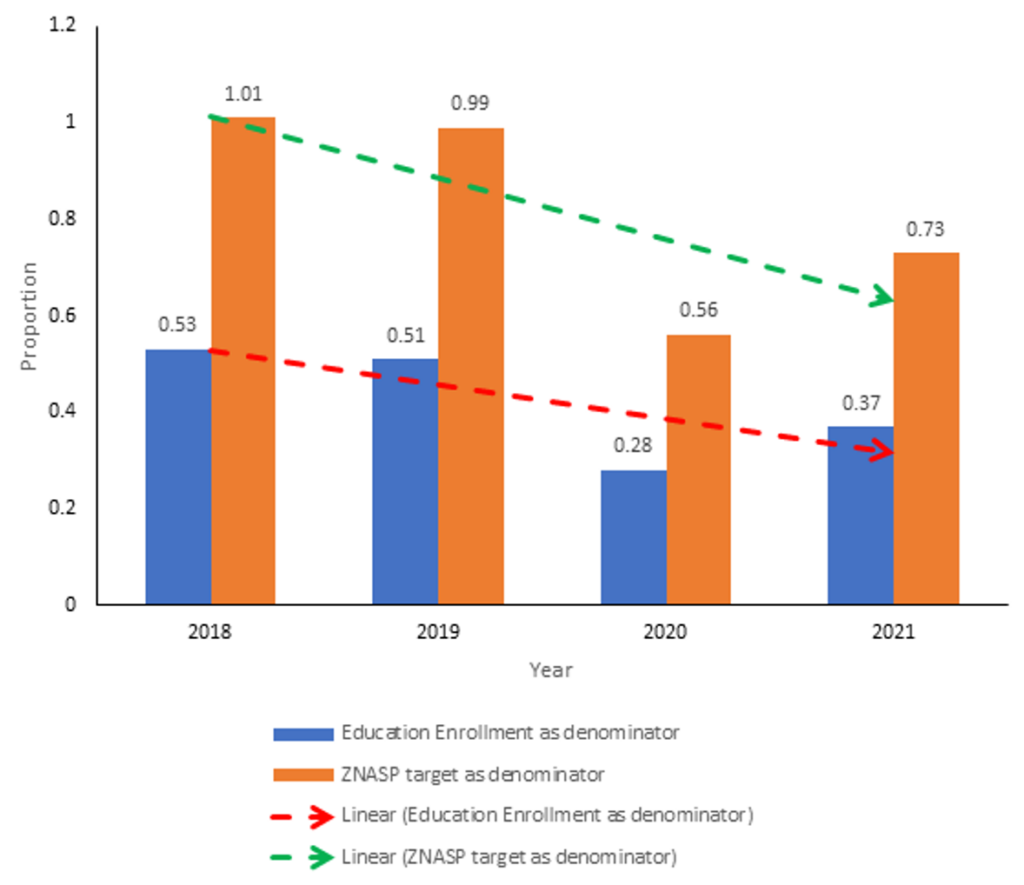

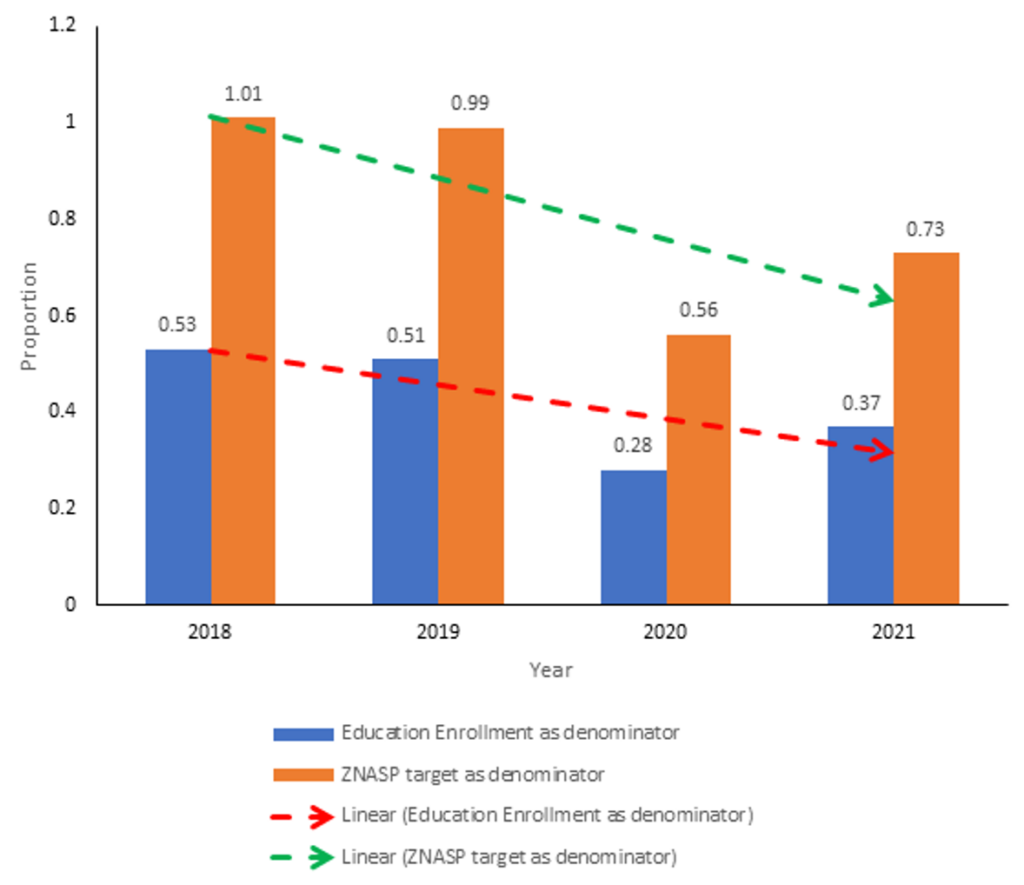

Using the Zimbabwe National AIDS Strategic Plan (ZNASP) targets, the proportion of girls in school reached through HIV/AIDS life skills education was 101% (1 012 568/1 000 000) in 2018 and reduced to 99% (991 062/1 000 000) in 2019 and then 56% (565 612/ 1 010 000) in 2020. The proportion of girls reached through HIV/AIDS life skills education then increased to 73% (743 675/1 020 000) in 2021 (χ2 528 239.19, p <0.001). Using the actual school enrolments as targets, the proportion of girls in school reached through HIV/AIDS life skills education reduced from 53% (1 012 568/ 1 910 511) in 2018 to 51% (991 062/1 943 273) in 2019 and 28% (565 612/2 020 137) in 2020. The proportion of girls reached through HIV/AIDS life skills education increased to 37% (743 675/2 009 894) in 2021 (χ2 202 157.71, p<0.001) (Figure 1).

There was a decrease in the percentage of girls out of school reached through HIV/AIDS life skills education from 27% (31 863/118 000) in the year 2018 to 22% (25 967/118 000) in 2019 and 5% (6 154/123 000) in 2020. The percentage of the girls reached increased to 6.4% (8 192/128 000) in the year 2021(χ2 29 775.28, p<0.001).

Girls dropping out of school

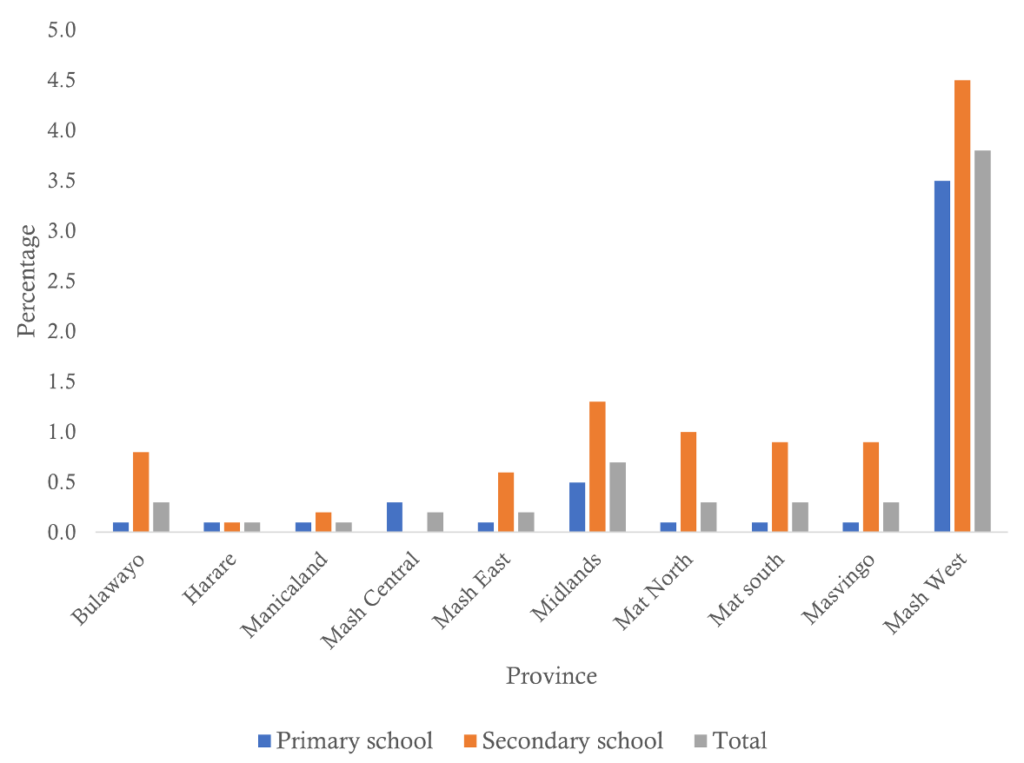

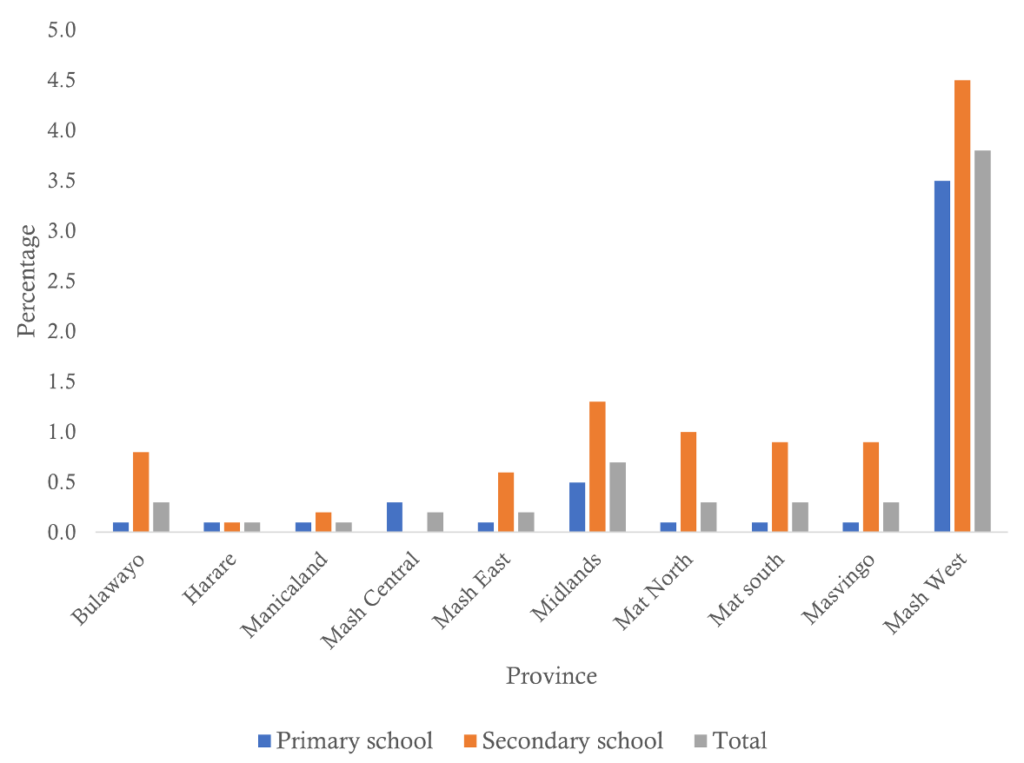

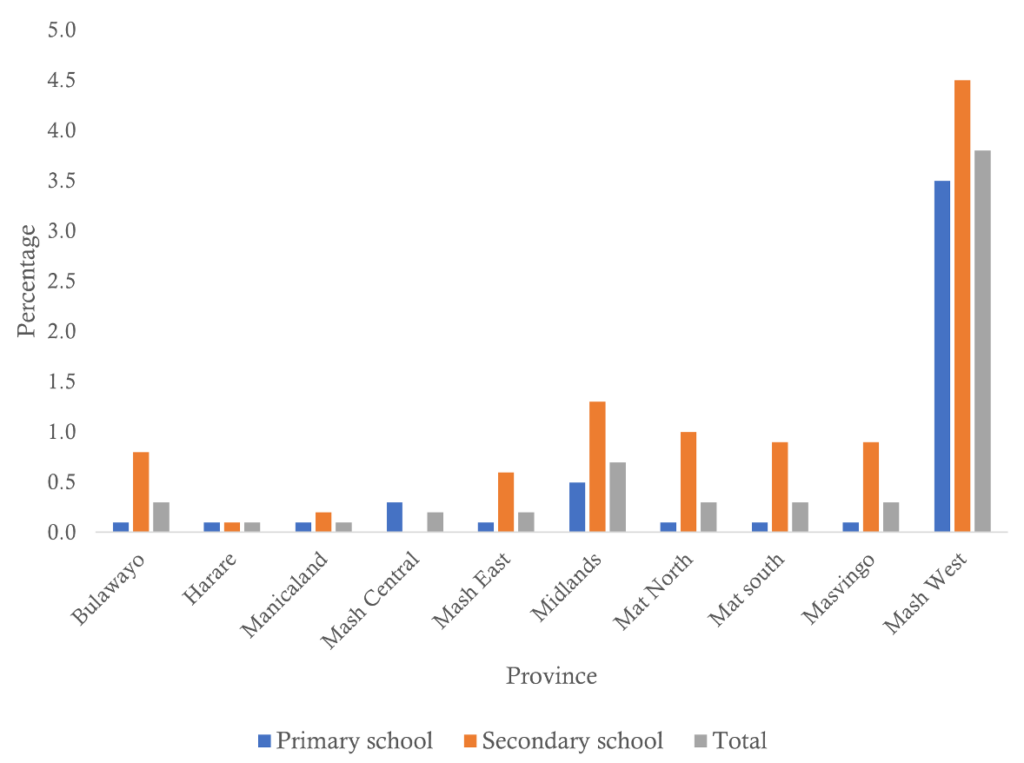

The proportion of girls dropping out of school in Zimbabwe was 0.84% (16 049/1 910 511) in 2018 and decreased to 0.66% (12 826/1 943 273) in 2019 and 0.13% (2 627/2 020 137) in 2020. The school dropout percentage then increased to 0.56% (11 256/2 009 894) in 2021 (χ2 3346.74, p<0.001). The greatest proportion of girls dropping out of school in Zimbabwe in the year 2021 was in Mashonaland West Province (3.8%), followed by Midlands Province (0.73%). The lowest proportion of girls dropping out of school was in Harare province with a dropout rate of 0.07% (Figure 2).

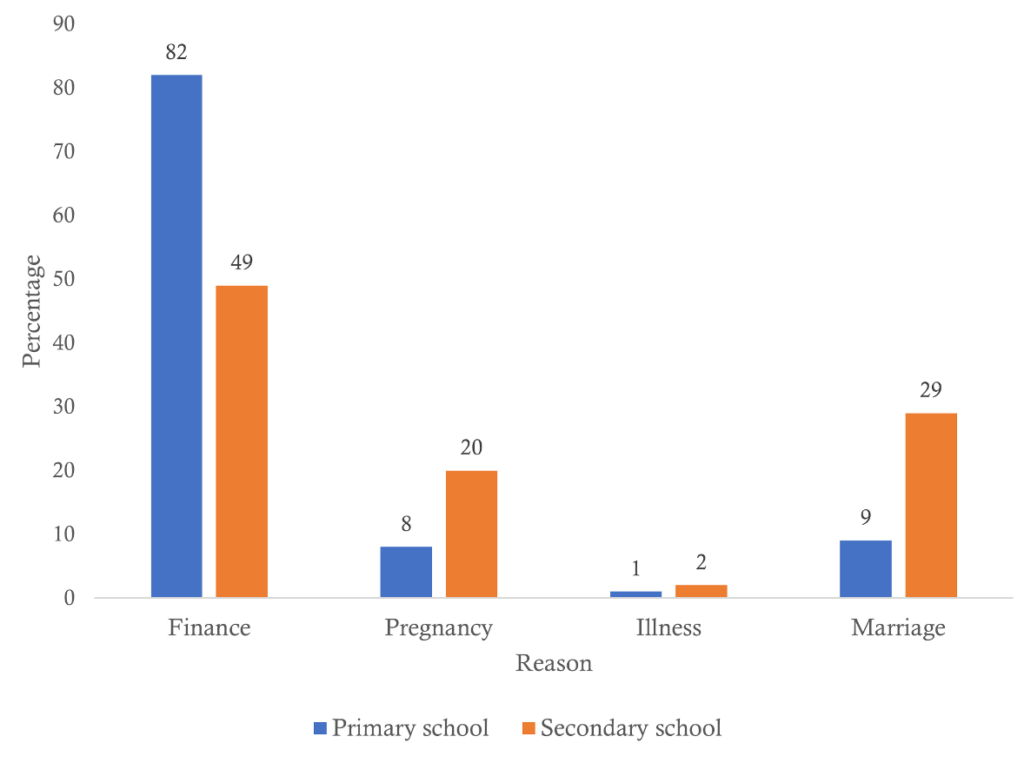

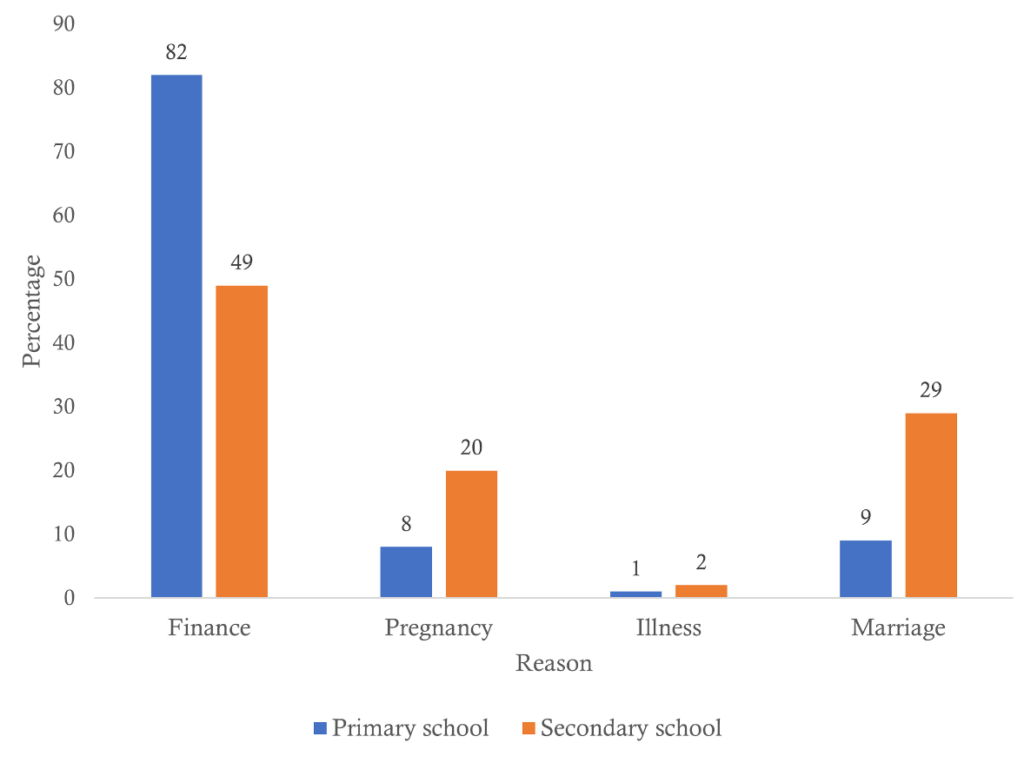

Reasons for school dropouts

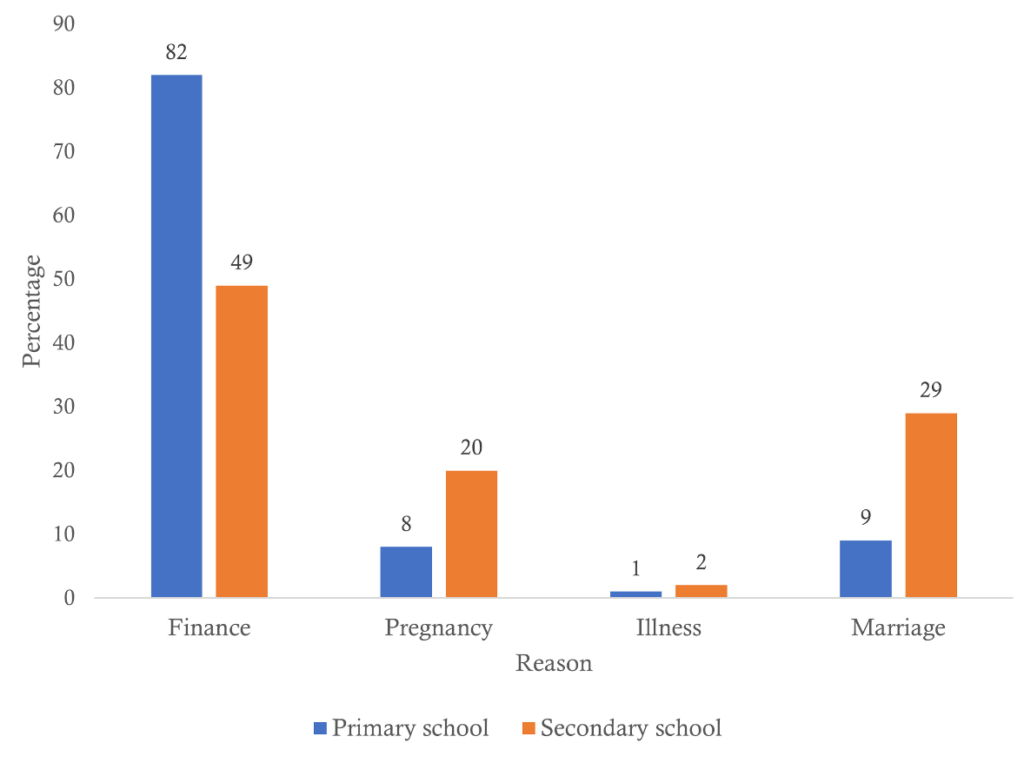

Financial problems contributed to 82% of dropouts among primary school girls and 49% of dropouts among secondary school girls. Early marriage contributed to 9% of dropouts among primary school girls and 29% of dropouts among secondary school girls. Pregnancy contributed to 8% of dropouts among primary school girls and 20% of dropouts among secondary school girls while illness contributed to 1% of dropouts among primary school girls and 2% among secondary school girls (Figure 3).

Access to clinical services

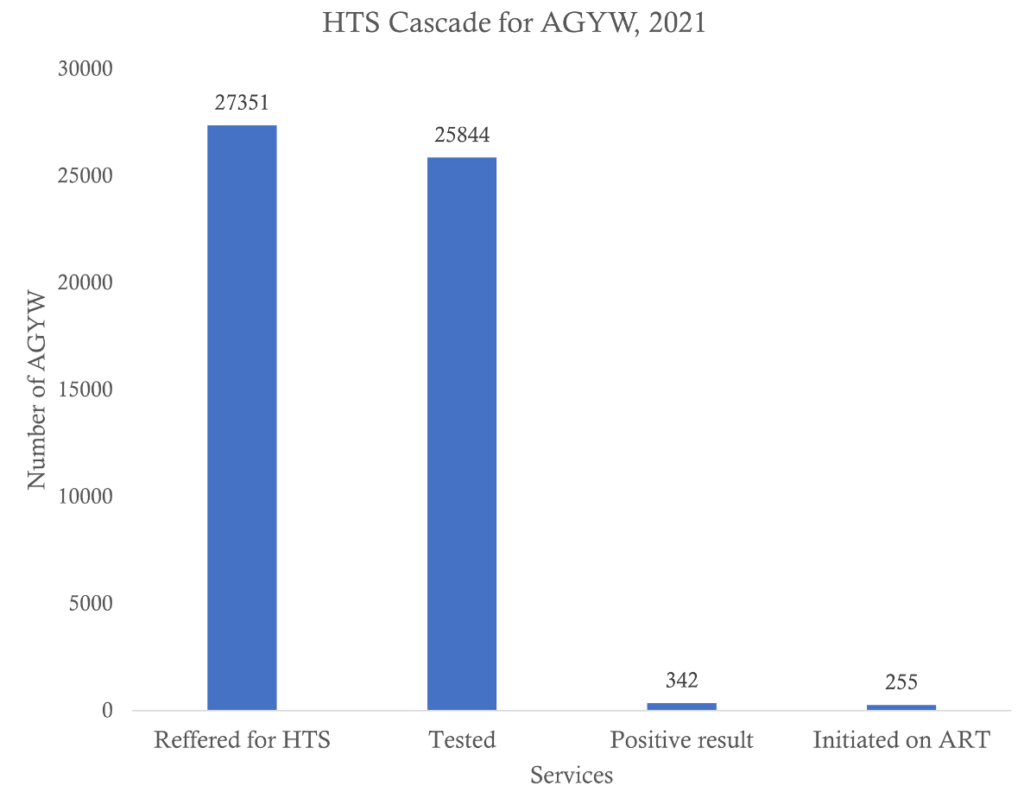

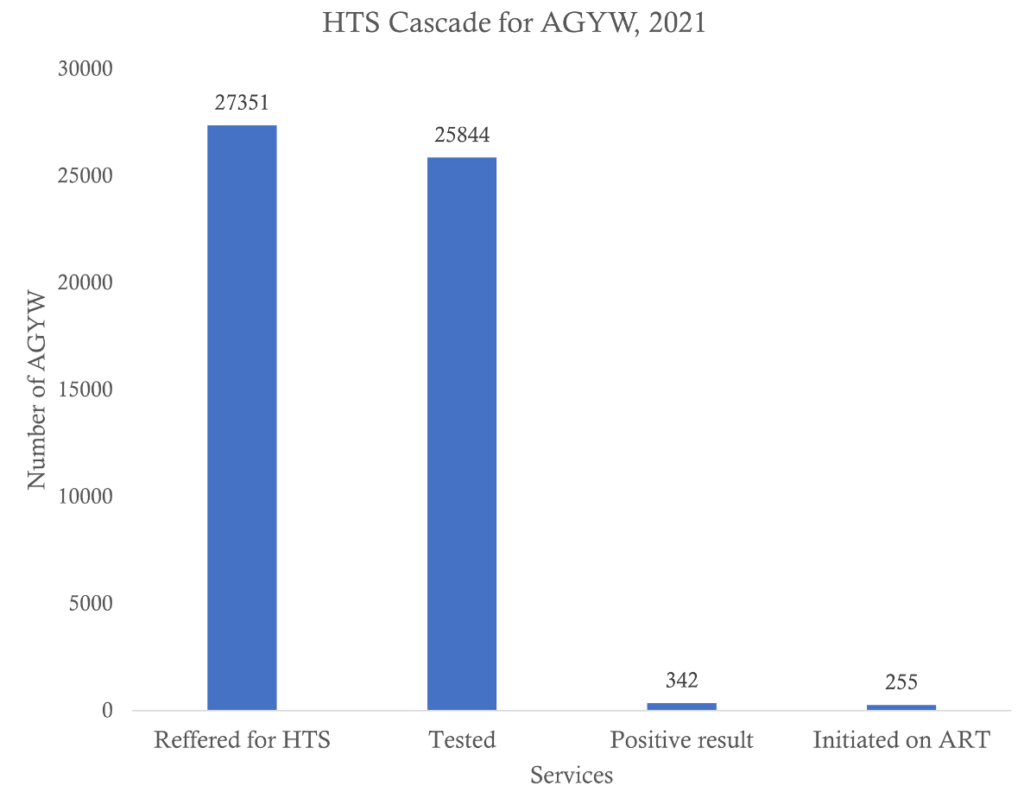

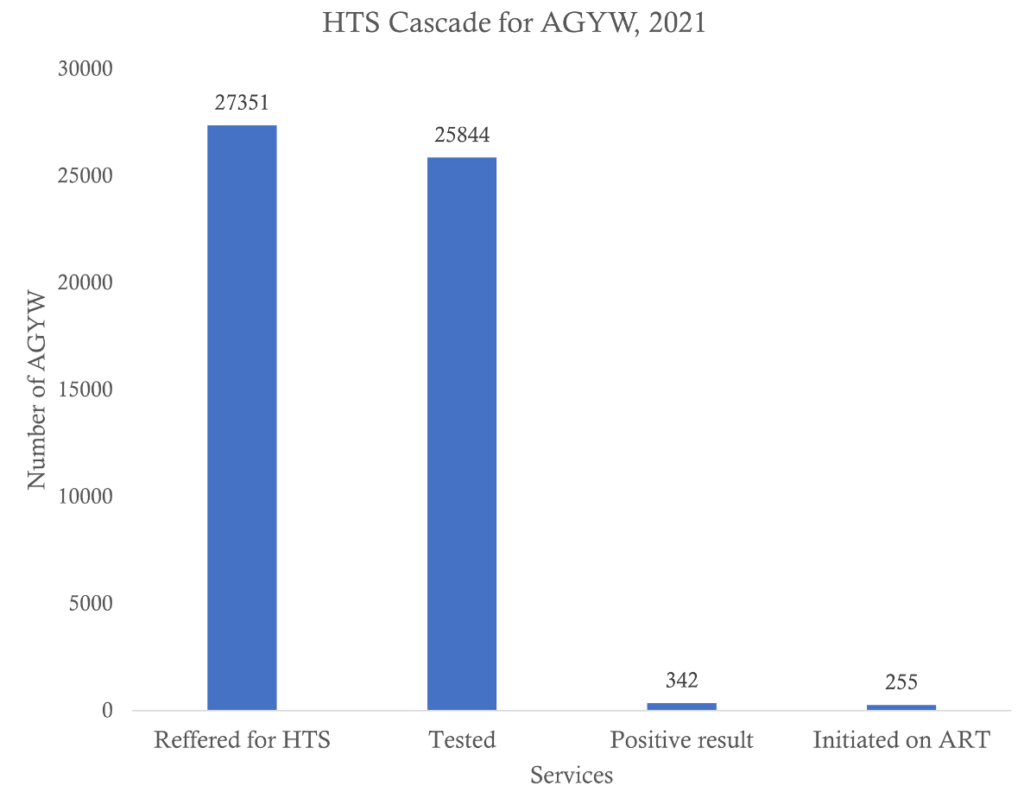

In 2021, 25 844 (94%) of the 27 351 girls referred for HIV testing services by the different AGYW initiative programs in Zimbabwe accessed the testing services and received their results. The positivity rate among the tested AGYWs was 1.3% (342/25 844) and 75% (255/342) of those testing HIV positive were initiated on ART (Figure 4).

In Mazowe District of Zimbabwe, most of the adolescent girls and young women who were referred for clinical services accessed the services, with 97.5% (828/849) accessing Pre-Exposure prophylaxis, 97.4% (3 793/3 894) being screened for sexually transmitted diseases, and 97.1% (842/867) accessing gender-based violence related services. Ninety-five percent (933/981) of AGYWs accessed family planning services, 91% (752/826) accessed HIV testing and 75.8% (50/66) accessed post-exposure prophylaxis (Table 2).

Discussion

The study’s findings revealed that the proportion of AGYW reached with HIV/AIDS education decreased from 2018 to 2020 and then slightly increased in 2021. The targets for the girls in school reached with HIV/AIDS education in the national HIV strategic plan did not match the actual school enrolments for girls. Financial constraints and early marriage were the major reasons for girls dropping out of school. Most of the AGYW referred for clinical services through the AGYW initiative accessed the respective services.

The significant decrease in adolescent girls and young women in schools who were reached with HIV/AIDS education could be attributed to the effects of Covid 19 mitigation measures. Schools and tertiary institutions were closed in the year 2020 and that is the year when the least proportion of girls and young women were reached with HIV/AIDS education. In a policy briefing in 2021, the Parliament of Zimbabwe highlighted that about 3.4 million learners failed to access education due to the lockdowns imposed by the government to curb the effects of Covid 19. Only those children from elite backgrounds managed to access education through e-learning platforms [9] Sibongile M P. COVID 19: A DEATH KNELL TO THE EDUCATION SYSTEM IN ZIMBABWE? Policy Brief No. 1 of 2021[Internet]. Harare (Zimbabwe): Parliament of Zimbabwe; 2021 [cited 2025 Apr 4]. 6 p. Available from: https://parlzim.gov.zw/download/policy-brief-covid-on-education/ Download POLICY BRIEF – COVID ON EDUCATION.pdf . This further widened the societal inequalities in access to education [10] Parker R, Morris K, Hofmeyr J. Education, inequality and innovation in the time of COVID-19 [Internet]. Johannesburg (South Africa): JET Education Services; 2020 Jul [cited 2025 Apr 4]; 49 p. Available from: https://www.jet.org.za/resources/theme-9-final-july-2020-parker-et-al.pdf Download theme-9-final-july-2020-parker-et-al.pdf . Lack of education is one of the drivers of HIV transmission among adolescent girls and young women. Studies have shown that low education is associated with reduced knowledge about health issues and HIV risk [11 11. Kiviniemi MT, Orom H, Waters EA, McKillip M, Hay JL. Education‐based disparities in knowledge of novel health risks: The case of knowledge gaps in HIV risk perceptions. British J Health Psychol [Internet]. 2018 Jan 31 [cited 2025 Apr 4];23(2):420–35. Available from: https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjhp.12297 https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12297 ,12] World Food Programme. Literature Review on the Impact of Education Levels on HIV/AIDS Prevalence Rates [Internet]. Rome (Italy): World Food Programme; 2006 Mar [cited 2025 Apr 4]. 15 p. Available from: https://healtheducationresources.unesco.org/sites/default/files/resources/Literature%20Review%20on%20the%20Impact%20of%20Education%20Levels%20on%20HIV-A.pdf Download . Governments should be deliberate in crafting home-grown solutions and funding mechanisms to ensure children do not drop out of school. Similarly there should also be intentional efforts by ministries of health to target and reach communities with lower levels of education with HIV risk communication strategies [13] Global Partnership for Education. How education plays a key role in the fight against AIDS: On World Aids Day, we explore the close link between preventing HIV/AIDS and education [Internet]. Washington (D.C.);Global Partnership for Education; 2018 Dec 1[cited 2025 Apr 4]. [about 3 screens]. Available from: https://www.globalpartnership.org/blog/how-education-plays-key-role-fight-against-aids .

There was an increase in the number of AGYW reached with comprehensive HIV/AIDS life skills education in the year 2021. This was attributed to a phased approach to opening schools towards the end of 2021. The Ministry of Education worked together with the Ministry of Health and Child Care and UNICEF to put together standard operating procedures in schools so that the reopening of schools would not increase the Covid 19 transmission rates among school children [14] Elizabeth Mupfumira. Zimbabwe’s children return to school after COVID-19 third wave disruptions: Over a billion children across the world have been impacted by school closures since the COVID-19 pandemic began – disrupting learning and increasing social vulnerabilities [Internet]. Harare (Zimbabwe): United Nations Children’s Fund; 2021 Sep 8[cited 2025 Apr 4]. [about 4 screens]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/zimbabwe/stories/zimbabwes-children-return-school-after-covid-19-third-wave-disruptions . That could have explained the proportions of the girls in school and young women in tertiary schools who were reached with HIV/AIDS education in that year.

There was a huge decline in the proportion of out-of-school girls reached with HIV education in 2020 and 2021 compared to 2018 and 2019. The lockdowns imposed during 2020 and 2021 also restricted movements and negatively affected access to community HIV prevention programs [15] Murewanhema G, Makurumidze R. Essential health services delivery in Zimbabwe during the COVID-19 pandemic: perspectives and recommendations. PAMJ [Internet]. 2020 Aug 11 [cited 2025 Apr 4]; 2020;35(2):143. Available from: https://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/35/143/full https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.143.25367 . This was consistent with findings from a multi-country study by Salve et al, 2023, where community health programs were negatively affected by COVID-19 public health measures such as restrictions on gatherings and travel [16] Salve S, Raven J, Das P, Srinivasan S, Khaled A, Hayee M, Olisenekwu G, Gooding K. Community health workers and Covid-19: Cross-country evidence on their roles, experiences, challenges and adaptive strategies. Daftary A, editor. PLOS Glob Public Health [Internet]. 2023 Jan 4 [cited 2025 Apr 4];3(1):e0001447. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001447 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001447 . This could be because these community programs were not regarded as emergency services. Community programs are important in AGYW health programming as they can act as safe spaces where the AGYW can build social support systems which are critical in HIV prevention [3] Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. UNAIDS DATA 2021 [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AID; 2021 [cited 2025 Apr 7]. 464 p. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC3032_AIDS_Data_book_2021_En.pdf Download JC3032_AIDS_Data_book_2021_En.pdf .

The major reasons for dropping out of school by primary and secondary school students were financial constraints, early marriage, and teenage pregnancy. Low resource settings are characterized by poverty which may be exacerbated by orphanhood, and this makes the affected AGYW vulnerable to early marriages and pregnancies. These findings are consistent with findings from studies done in Zimbabwe, Ghana, and the Democratic Republic of Congo [17 Adam S, Adom D, Bediako A. The Major Factors That Influence Basic School Dropout in Rural Ghana: The Case of Asunafo South District in the Brong Ahafo Region of Ghana. J Educ Pract [Internet]. 2016 Oct 1[cited 2025 Apr 4];7:1–8. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Factors-that-influence-dropout-Source-Authors-Field-Survey-September-2016_fig1_310064576 Download JEP-Vol.7 No.28 2016.pdf ,18] Hubert Ngamaba K, Sedzo Lombo L, Lombo G, Ekira Viviar N. Causes and consequences of school dropout in Kinshasa: students’ perspectives before and after dropping out. JAE [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Apr 4];2(3):177–94. Available from: https://journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.31920/2633-2930/2021/v2n3a8 https://doi.org/10.31920/2633-2930/2021/v2n3a8 . Keeping girls in school has been shown to have a protective effect on reducing their risk of acquiring HIV infection [19] Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Keeping girls in school reduces new HIV infections [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS ; 2021 Apr 6 [cited 2025 Apr 4]. [about 2 screens]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2021/april/20210406_keeping-girls-in-school-reduces-new-hiv-infections .

Of the adolescent girls and young women who were referred for clinical services in Mazowe District, the majority accessed the respective services. This could be due to these services being provided free of charge at the health facilities in Zimbabwe. Out-of-pocket expenses can act as a barrier to access to HIV-related services by adolescent girls and young women [20] Chanley J, Ouma L, Shaikat S.M, Adolescents and Youth Are Key to Fully Achieving Universal Health Coverage: In 2021, adolescents and youth between ages 10 and 24 are estimated to make up approximately 24% of the world’s population [Internet]. Washington (D. C): Population Reference Bureau; 2021 Apr 8 [cited 2025 Apr 4]. [about 4 screens]. Available from: https://www.prb.org/resources/adolescents-and-youth-are-key-to-fully-achieving-universal-health-coverage/ . Apart from health facility fees, out-of-pocket expenses can also be in the form of transport costs. This was consistent with an article by Sidamo et al, 2024, where a lack of adolescent-friendly services and insufficient outreach efforts were found to be barriers to access to health by AGYW [21] Sidamo NB, Abebe Kerbo A, Gidebo KD, Wado YD. A policy brief: improving access and utilization of adolescent sexual and reproductive health services in Southern Ethiopia. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2024 Nov 21 [cited 2025 Apr 4];12:1364058. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1364058/full https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1364058 . AGYW initiative implementing partners support outreach programs that bring clinical services closer to the communities, thereby increasing access to the services and reducing travel costs. Community outreaches facilitated the utilization of sexual and reproductive health services by youths in Southern Africa [22] Ninsiima LR, Chiumia IK, Ndejjo R. Factors influencing access to and utilisation of youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2021 Jun 27 [cited 2025 Apr 4];18(1):135. Available from: Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-021-01183-y https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01183-y . Skovdal et al, in 2022, found that community based health initiatives improved the uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis among AGYW [23] Skovdal M, Magoge-Mandizvidza P, Dzamatira F, Maswera R, Nyamukapa C, Thomas R, Mugurungi O, Gregson S. Improving access to pre-exposure prophylaxis for adolescent girls and young women: recommendations from healthcare providers in eastern Zimbabwe. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2022 Apr 23 [cited 2025 Apr 4];22(1):399. Available from: https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-022-07376-5 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07376-5 . The AGYW initiative programs also allow the AGYWs to interact as peers. Peer education and support are critical in influencing the AGYWs to seek the clinical services that they would have been referred for [22] Ninsiima LR, Chiumia IK, Ndejjo R. Factors influencing access to and utilisation of youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2021 Jun 27 [cited 2025 Apr 4];18(1):135. Available from: Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-021-01183-y https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01183-y .

Limitation

The data was aggregated so an analysis of the performance of the different AGYW initiative programs could not be conducted. Since analysis of access to clinical services was restricted to 2021 due to incomplete datasets for the other years, we were not able to assess the impact of COVID on the utilistaion of this services.

Conclusion

There was good access to clinical services by the AGYWs who were referred through the AGYW initiative. However, based on the actual school enrolments, the coverage of the AGYW initiative was low. The COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected the implementation of the HIV/AIDS education programs in Zimbabwe. The major reasons for children dropping out of school were financial constraints, early marriages, and teen pregnancies.

The targets for the AGYWs reached with HIV/AIDS life skills and education should be revised and matched to the actual school enrolments and the statistics for girls out of school. Measures should also be put in place for the continuation of health services during potential future emergencies.

What is already known about the topic

- AGWY are at a higher risk of acquiring new HIV infections than adolescent boys and young men.

- Poverty, lack of education and discriminatory social and cultural norms are drivers of HIV infections among the AGYW.

What this study adds

- The COVID-19 pandemic magnified the effects of the drivers of HIV transmission among AGYW in Zimbabwe.

- There are discrepancies between the target numbers set in the ZNASP for in-school girls reached with HIV/AIDS life skills education and the actual school enrolments which reflects under targeting of girls who could benefit from HIV prevention services.

- The majority of AGYW referred for clinical services access the services that they are referred for.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the staff at the Ministry of Health and Child Care AIDS and TB Directorate, and NAC for their support. Special thanks go to the staff in the Family Medicine, Global and Public Health Unit, Department of Primary Health Care Sciences, and the Health Studies Office for the guidance and support that they rendered to us.

Authors´ contributions

Conceptualization: Godwin Choga, Mufuta Tshimanga, Owen Mugurungi, Tsitsi Patience Juru, Notion Tafara Gombe, Gerald Shambira, Addmore Chadambuka, Godwin Choga, Owen Mugurungi, Tsitsi Patience Juru, Gibson Mandozana, Addmore Chadambuka, Notion Tafara Gombe, Gerald Shambira, Mufuta Tshimanga; Data curation: Godwin Choga, Mufuta Tshimanga, Owen Mugurungi, Tsitsi Patience Juru, Gibson Mandozana; Formal analysis: Godwin Choga, Mufuta Tshimanga, Tsitsi Patience Juru, Gibson Mandozana, Gerald Shambira, Notion Tafara Gombe; Investigation: Godwin Choga, Owen Mugurungi; Methodology: Godwin Choga, Mufuta Tshimanga, Owen Mugurungi, Tsitsi Patience Juru, Gibson Mandozana, Notion Tafara Gombe, Gerald Shambira, Addmore Chadambuka; Project administration: Godwin Choga, Mufuta Tshimanga, Owen Mugurungi, Tsitsi Patience Juru, Gibson Mandozana, Notion Tafara Gombe, Gerald Shambira; Resources: Godwin Choga, Mufuta Tshimanga, Owen Mugurungi, Tsitsi Patience Juru; Supervision: Mufuta Tshimanga, Owen Mugurungi, Tsitsi Patience Juru, Gibson Mandozana, Notion Tafara Gombe, Gerald Shambira, Addmore Chadambuka; Validation: Mufuta Tshimanga, Owen Mugurungi, Tsitsi Patience Juru, Gibson Mandozana; Writing – original draft: Godwin Choga, Mufuta Tshimanga, Owen Mugurungi, Tsitsi Patience Juru, Gibson Mandozana, Notion Tafara Gombe, Gerald Shambira, Addmore Chadambuka; Writing – review & editing: Godwin Choga, Mufuta Tshimanga, Owen Mugurungi, Tsitsi Patience Juru, Gibson Mandozana, Notion Tafara Gombe, Gerald Shambira, Addmore Chadambuka.

| Variable | Numerator | Denominator |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion of girls in school reached through HIV/AIDS life skills education | Number of girls in school reached through HIV/AIDS life skills education | 1. ZNASP target for girls in school reached through HIV/AIDS life skills education 2. Number of girls enrolled in schools |

| Proportion of girls out of school reached with comprehensive sexuality HIV/AIDS education | Number of girls out of school reached with comprehensive sexuality HIV/AIDS education | Number of girls out of school |

| Proportion of girls dropping out of school | Number of girls dropping out of school | Number of girls enrolled in schools |

| Proportion of AGYW who were tested for HIV and received their results | Number of AGYW who were tested for HIV and received their results | Number of AGYW referred for HIV testing |

| Proportion of AGYW who tested HIV positive | Number of AGYW who tested HIV positive | Number of AGYW who were tested for HIV and received their results |

| Proportion of AGYW who were initiated on ART | Number of AGYW who were initiated on ART | Number of AGYW who tested HIV positive |

| Proportion of AGYW who accessed Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) | Number of AGYW who accessed PrEP | Number of AGYW who were referred for PrEP |

| Proportion of AGYW who accessed STI screening | Number of AGYW who accessed STI screening | Number of AGYW who were referred for STI screening |

| Proportion of AGYW who accessed Gender Based Violence (GBV) related services | Number of AGYW who accessed GBV-related services | Number of AGYW who were referred for GBV-related services |

| Proportion of AGYW who accessed family planning services | Number of AGYW who accessed family planning services | Number of AGYW who were referred for family planning services |

| Proportion of AGYW who accessed HIV testing services | Number of AGYW who accessed HIV testing services | Number of AGYW who were referred for HIV testing services |

| Proportion of AGYW who accessed Post Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) | Number of AGYW who accessed PEP | Number of AGYW who were referred for PEP |

| Services | Referred | Accessed | Proportion % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis | 849 | 828 | 97.5 |

| STI screening | 3894 | 3793 | 97.4 |

| Gender Based Violence related services | 867 | 842 | 97.1 |

| Family planning | 981 | 933 | 95.1 |

| HIV testing | 826 | 752 | 91.0 |

| Post Exposure Prophylaxis | 66 | 50 | 75.8 |

Source: NAC AGYW Initiative dataset for Mazowe District, Zimbabwe.

References

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Global AIDS Update| 2020: Seizing the moment - Tackling entrenched inequalities to end epidemics [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2020 [cited 2025 Apr 4]; 380 p. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2020_global-aids-report_en.pdf Download 2020_global-aids-report_en.pdf

- The Global Fund. Technical Brief: Gender Equity [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): The Global Fund; 2019 Oct [cited 2025 Apr 4]. 22 p. Available from: https://eecaplatform.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/core_gender_infonote_en.pdf Download core_gender_infonote_en.pdf

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AID UNAIDS DATA 2021 [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AID; 2021 [cited 2025 Apr 7]. 464 p. Available from:https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC3032_AIDS_Data_book_2021_En.pdf Download JC3032_AIDS_Data_book_2021_En.pdf

- Ministry of Health and Child Care (ZIM). Zimbabwe Population-based HIV Impact Assessment 2020 (ZIMPHIA 2020) [Internet]. Harare (Zimbabwe): Ministry of Health and Child Care; 2021 Dec [cited 2025 Apr 4]. 207 p. Available from: https://phia.icap.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/010923_ZIMPHIA2020-interactive-versionFinal.pdf Download 010923_ZIMPHIA2020-interactive-versionFinal.pdf

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF ESARO). Assessing the Vulnerability and Risks of Adolescent Girls and Young Women in Eastern and Southern Africa: A Review of the Tools in Use [Internet]. Nairobi (Kenya): United Nations Children’s Fund(UNICEF ESARO); 2019 Jun [cited 2025 Apr 4]. 30 p. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/esa/media/9146/file/UNICEF-ESARO-AGYW-RV-Assessment-2021.pdf Download UNICEF-ESARO-AGYW-RV-Assessment-2021.pdf

- The Global Fund. THE GLOBAL FUND MEASUREMENT FRAMEWORK FOR ADOLESCENTS GIRLS and YOUNG WOMEN PROGRAMS [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): The Global Fund; 2018 Sep [cited 2025 Apr 4]. 36 p. Available from:https://resources.theglobalfund.org/media/13924/cr_me-adolescents-girls-young-women-programs_framework_en.pdf Download cr_me-adolescents-girls-young-women-programs_framework_en.pdf

- Zimbabwe National Statistic Agency. 2022 Population and Housing Census Preliminary Results [Internet]. Harare (Zimbabwe): Zimbabwe National Statistic Agency; 2022 [cited 2025 Apr 4]. 159 p. Available from: https://zimbabwe.unfpa.org/en/publications/2022-population-and-housing-census-preliminary-results Download 2022_population_and_housing_census_preliminary_report_on_population_figures.pdf

- Ministry of Health and Child Care (ZIM). ZIMBABWE NATIONAL HIV AND AIDS STRATEGIC PLAN 2021 – 2025 [Internet]. Harare (Zimbabwe): Ministry of Health and Child Care; 2020 Jul [cited 2025 Apr 7]. 109 p. Available from: https://www.nac.org.zw/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/ZIMBABWE-NATIONAL-HIV-STATEGIC-PLAN_2021-2025-1.pdf Download ZIMBABWE-NATIONAL-HIV-STATEGIC-PLAN_2021-2025-1.pdf

- Sibongile M P. COVID 19: A DEATH KNELL TO THE EDUCATION SYSTEM IN ZIMBABWE? Policy Brief No. 1 of 2021[Internet]. Harare (Zimbabwe): Parliament of Zimbabwe; 2021 [cited 2025 Apr 4]. 6 p. Available from: https://parlzim.gov.zw/download/policy-brief-covid-on-education/ Download POLICY BRIEF – COVID ON EDUCATION.pdf

- Parker R, Morris K, Hofmeyr J. Education, inequality and innovation in the time of COVID-19 [Internet]. Johannesburg (South Africa): JET Education Services; 2020 Jul [cited 2025 Apr 4]; 49 p. Available from: https://www.jet.org.za/resources/theme-9-final-july-2020-parker-et-al.pdf Download theme-9-final-july-2020-parker-et-al.pdf

- Kiviniemi MT, Orom H, Waters EA, McKillip M, Hay JL. Education‐based disparities in knowledge of novel health risks: The case of knowledge gaps in HIV risk perceptions. British J Health Psychol [Internet]. 2018 Jan 31 [cited 2025 Apr 4];23(2):420– Available from: https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjhp.12297 https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12297

- World Food Programme. Literature Review on the Impact of Education Levels on HIV/AIDS Prevalence Rates [Internet]. Rome (Italy): World Food Programme; 2006 Mar [cited 2025 Apr 4]. 15 p. Available from: https://healtheducationresources.unesco.org/sites/default/files/resources/Literature%20Review%20on%20the%20Impact%20of%20Education%20Levels%20on%20HIV-A.pdf Download Literature Review on the Impact of Education Levels on HIV-A.pdf

- Global Partnership for Education. How education plays a key role in the fight against AIDS: On World Aids Day, we explore the close link between preventing HIV/AIDS and education [Internet]. Washington (D.C.);Global Partnership for Education; 2018 Dec 1[cited 2025 Apr 4]. [about 3 screens]. Available from: https://www.globalpartnership.org/blog/how-education-plays-key-role-fight-against-aids

- Elizabeth Mupfumira. Zimbabwe’s children return to school after COVID-19 third wave disruptions: Over a billion children across the world have been impacted by school closures since the COVID-19 pandemic began – disrupting learning and increasing social vulnerabilities [Internet]. Harare (Zimbabwe): United Nations Children’s Fund; 2021 Sep 8[cited 2025 Apr 4]. [about 4 screens]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/zimbabwe/stories/zimbabwes-children-return-school-after-covid-19-third-wave-disruptions

- Murewanhema G, Makurumidze R. Essential health services delivery in Zimbabwe during the COVID-19 pandemic: perspectives and recommendations. PAMJ [Internet]. 2020 Aug 11 [cited 2025 Apr 4]; 2020;35(2):143. Available from: https://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/35/143/full https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.143.25367

- Salve S, Raven J, Das P, Srinivasan S, Khaled A, Hayee M, Olisenekwu G, Gooding K. Community health workers and Covid-19: Cross-country evidence on their roles, experiences, challenges and adaptive strategies. Daftary A, editor. PLOS Glob Public Health [Internet]. 2023 Jan 4 [cited 2025 Apr 4];3(1):e0001447. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001447 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001447

- Adam S, Adom D, Bediako A. The Major Factors That Influence Basic School Dropout in Rural Ghana: The Case of Asunafo South District in the Brong Ahafo Region of Ghana. J Educ Pract [Internet]. 2016 Oct 1[cited 2025 Apr 4];7:1–8. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Factors-that-influence-dropout-Source-Authors-Field-Survey-September-2016_fig1_310064576Download JEP-Vol.7 No.28 2016.pdf

- Hubert Ngamaba K, Sedzo Lombo L, Lombo G, Ekira Viviar N. Causes and consequences of school dropout in Kinshasa: students’ perspectives before and after dropping out. JAE [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Apr 4];2(3):177–94. Available from: https://journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.31920/2633-2930/2021/v2n3a8 https://doi.org/10.31920/2633-2930/2021/v2n3a8

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Keeping girls in school reduces new HIV infections [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS ; 2021 Apr 6 [cited 2025 Apr 4]. [about 2 screens]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2021/april/20210406_keeping-girls-in-school-reduces-new-hiv-infections

- Chanley J, Ouma L, Shaikat S.M, Adolescents and Youth Are Key to Fully Achieving Universal Health Coverage: In 2021, adolescents and youth between ages 10 and 24 are estimated to make up approximately 24% of the world’s population [Internet]. Washington (D. C): Population Reference Bureau; 2021 Apr 8 [cited 2025 Apr 4]. [about 4 screens]. Available from: https://www.prb.org/resources/adolescents-and-youth-are-key-to-fully-achieving-universal-health-coverage/

- Sidamo NB, Abebe Kerbo A, Gidebo KD, Wado YD. A policy brief: improving access and utilization of adolescent sexual and reproductive health services in Southern Ethiopia. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2024 Nov 21 [cited 2025 Apr 4];12:1364058. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1364058/full https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1364058

- Ninsiima LR, Chiumia IK, Ndejjo R. Factors influencing access to and utilisation of youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2021 Jun 27 [cited 2025 Apr 4];18(1):135. Available from: Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-021-01183-y https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01183-y

- Skovdal M, Magoge-Mandizvidza P, Dzamatira F, Maswera R, Nyamukapa C, Thomas R, Mugurungi O, Gregson S. Improving access to pre-exposure prophylaxis for adolescent girls and young women: recommendations from healthcare providers in eastern Zimbabwe. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2022 Apr 23 [cited 2025 Apr 4];22(1):399. Available from: https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-022-07376-5 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07376-5

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Tables

| Variable | Numerator | Denominator |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion of girls in school reached through HIV/AIDS life skills education | Number of girls in school reached through HIV/AIDS life skills education | 1. ZNASP target for girls in school reached through HIV/AIDS life skills education 2. Number of girls enrolled in schools |

| Proportion of girls out of school reached with comprehensive sexuality HIV/AIDS education | Number of girls out of school reached with comprehensive sexuality HIV/AIDS education | Number of girls out of school |

| Proportion of girls dropping out of school | Number of girls dropping out of school | Number of girls enrolled in schools |

| Proportion of AGYW who were tested for HIV and received their results | Number of AGYW who were tested for HIV and received their results | Number of AGYW referred for HIV testing |

| Proportion of AGYW who tested HIV positive | Number of AGYW who tested HIV positive | Number of AGYW who were tested for HIV and received their results |

| Proportion of AGYW who were initiated on ART | Number of AGYW who were initiated on ART | Number of AGYW who tested HIV positive |

| Proportion of AGYW who accessed Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) | Number of AGYW who accessed PrEP | Number of AGYW who were referred for PrEP |

| Proportion of AGYW who accessed STI screening | Number of AGYW who accessed STI screening | Number of AGYW who were referred for STI screening |

| Proportion of AGYW who accessed Gender Based Violence (GBV) related services | Number of AGYW who accessed GBV-related services | Number of AGYW who were referred for GBV-related services |

| Proportion of AGYW who accessed family planning services | Number of AGYW who accessed family planning services | Number of AGYW who were referred for family planning services |

| Proportion of AGYW who accessed HIV testing services | Number of AGYW who accessed HIV testing services | Number of AGYW who were referred for HIV testing services |

| Proportion of AGYW who accessed Post Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) | Number of AGYW who accessed PEP | Number of AGYW who were referred for PEP |

| Services | Referred | Accessed | Proportion % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis | 849 | 828 | 97.5 |

| STI screening | 3894 | 3793 | 97.4 |

| Gender Based Violence related services | 867 | 842 | 97.1 |

| Family planning | 981 | 933 | 95.1 |

| HIV testing | 826 | 752 | 91.0 |

| Post Exposure Prophylaxis | 66 | 50 | 75.8 |

Source: NAC AGYW Initiative dataset for Mazowe District, Zimbabwe.

Table 2: Proportion of AGYW referred for services who accessed the services in Mazowe District, Zimbabwe, 2021

Figures

Figure 1: Percentage of girls in school reached through HIV/AIDS life skills education in Zimbabwe, 2018-2021 (Source: Numerator: NAC AGYW Initiative dataset, Denominators: Education enrollments reports, Zimbabwe National AIDS Strategy targets)

Keywords

- Adolescent girls

- Young women

- HIV/AIDS education

- HIV care

- Zimbabwe