Research![]() | Volume 8, Article 20, 14 Apr 2025

| Volume 8, Article 20, 14 Apr 2025

Trend analysis of age-specific adolescent pregnancy among antenatal care registrants, Savannah Region, Ghana 2018 to 2022

Ballu Cletus1,2,&, Odikro Magdalene Akos2, Akowuah George2, Gyesi Razak Issahaku2.3, Gyasi Ophelia Apau4, Bandoh Delia Akosua2, Kenu Ernest2, Kubio Chrysantus5

1Buipe Polyclinic, Ghana Health Service, Savannah Region, Ghana, 2Ghana Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program, School of Public Health, University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana, 3Laboratory Department, Tamale Teaching Hospital, Tamale, Ghana, 4University for Development Studies School of Medicine, Tamale, Ghana, 5Savannah Regional Health Directorate, Ghana Health Service, Damongo, Ghana

&Corresponding author: Ballu Cletus, Buipe Polyclinic, Ghana Health Service, Savannah Region, Ghana, Email: cletusballu@gmail.com

Received: 17 Apr 2024, Accepted: 04 Mar 2025, Published: 14 Apr 2025

Domain: Maternal and Child Health, Adolescent Health

Keywords: Adolescent pregnancy, Savannah Region, period prevalence, Age-specific adolescent birth rate

©Ballu Cletus et al Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health (ISSN: 2664-2824). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Ballu Cletus et al Trend analysis of age-specific adolescent pregnancy among antenatal care registrants, Savannah Region, Ghana 2018 to 2022. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health. 2025;8:20. https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph.2025.8.2.168

Abstract

Introduction: Adolescent pregnancy prevalence is a key determinant of health and socio-economic growth, affecting maternal and perinatal outcomes. In Ghana, it is roughly three times higher than in developed countries. Understanding age-specific dynamics is essential for meeting the sustainable development goal (SDG) for reproductive health targets. This study aimed to assess the period prevalence of adolescent pregnancies in the Savannah region, identify the district with the highest prevalence, determine the age-specific adolescent birth rate, and analyze trends in reducing birth rate for both early and late adolescent pregnancies.

Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of a single data set over five years (2018 – 2022) in the Savannah Region. Records of adolescent mothers on ante-natal visits at registration from the District Health Information Management System 2 DHIMS2 were utilized. Age-specific bivariate analysis was conducted at a 95% confidence interval using Microsoft Excel 2018. We analysed the data by year and determined the period prevalence, age-specific adolescent birth rate (ASABR), and rate of change in prevalence. Microsoft Excel spreadsheet was used in analyzing the data. We presented results graphically with a forest plot, simple line and bar graphs, and a map using QGIS.

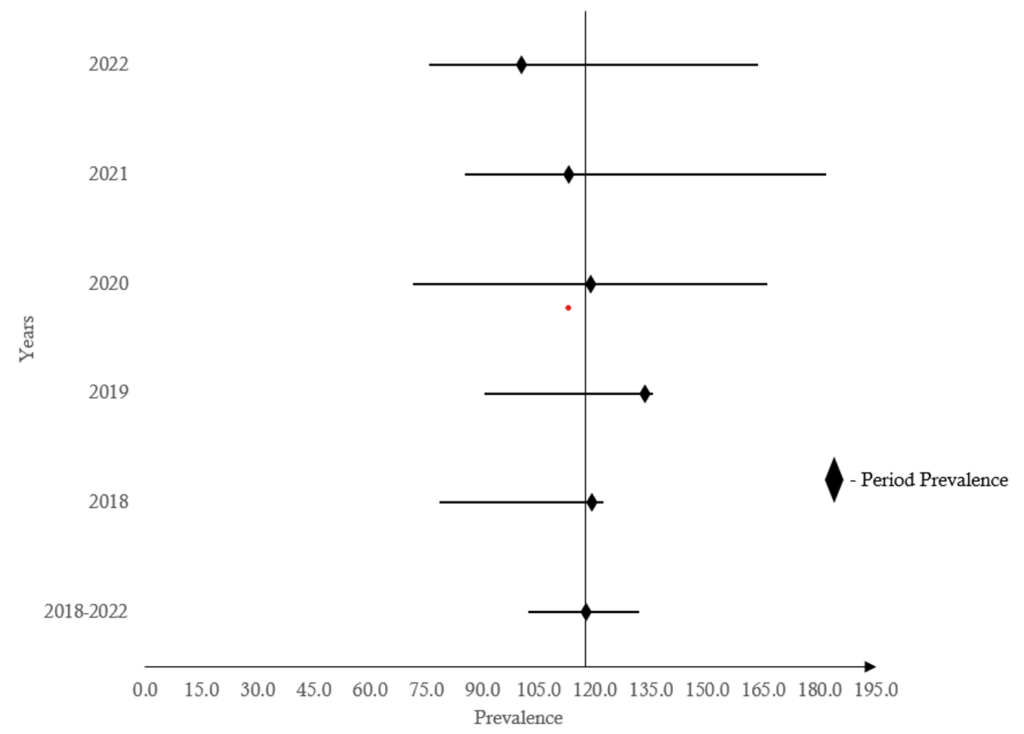

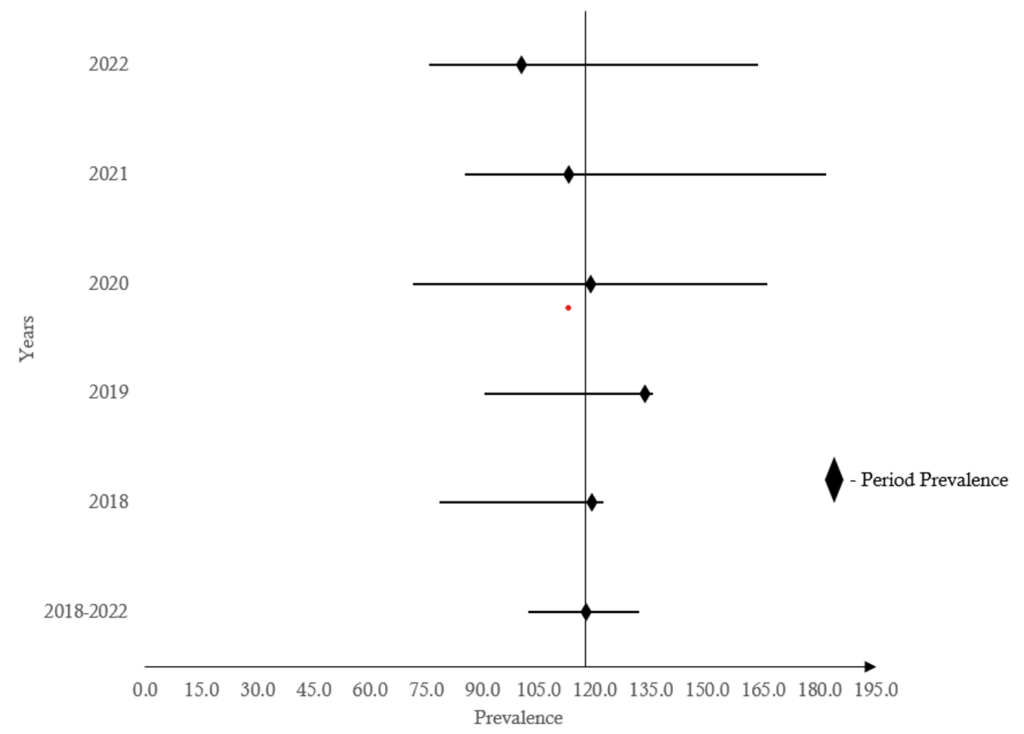

Results: The period prevalence of adolescent pregnancy in the Savannah Region was 117.50 childbirths per 1000 women (95% CI: of 102.17 -– 131.92). Prevalence among late adolescents was 230 childbirths per 1000 (95% CI: of 165. I3- 296.01) with a rate of change of +0.8 childbirths per 1000 women per year. Early adolescent pregnancy prevalence was 6.57 (95% CI: 3.46 -– 9.68) with a rate of change of +0.4 child births per 1000 women per year. The prevalence in the Bole District was 230 births per 1000 (95% CI; 165-296).

Conclusion: Adolescent pregnancy prevalence in the Savannah Region exceeds global estimates for Sub-Saharan Africa, with early adolescent pregnancies showing the least reduction over the five years despite interventions implemented. Bole District had the highest prevalence in the region. Targeted interventions and policies are needed to strengthen sexual and reproductive health, particularly in high-burden areas with slower reductions.

Introduction

Adolescent pregnancy is a planned or unplanned pregnancy in a girl between the ages of 10 to 19 years [1] United Nations Population Fund. Adolescent pregnancy [Internet]. New York (NY): United Nations Population Fund; c2025 [cited 2025 Mar 25]. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/adolescent-pregnancy#readmore-expand . Although global adolescent pregnancy rates have seen notable progress, about a 35% reduction in the global trend as of 2023, approximately 21 million adolescent pregnancies are still reported annually [2] World Health Organization. Adolescent pregnancy [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2024 Apr 10[cited 2025 Mar 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy . In developed countries, one in five adolescent girls becomes pregnant before the age of 18, while in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), this figure rises to at least one in three [2] World Health Organization. Adolescent pregnancy [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2024 Apr 10[cited 2025 Mar 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy [3] Azzopardi PS, Hearps SJC, Francis KL, Kennedy EC, Mokdad AH, Kassebaum NJ, Lim S, Irvine CMS, Vos T, Brown AD, Dogra S, Kinner SA, Kaoma NS, Naguib M, Reavley NJ, Requejo J, Santelli JS, Sawyer SM, Skirbekk V, Temmerman M, Tewhaiti-Smith J, Ward JL, Viner RM, Patton GC. Progress in adolescent health and wellbeing: tracking 12 headline indicators for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016. The Lancet [Internet]. 2019 Mar 12[cited 2025 Mar 25];393(10176):1101–18. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673618324279 https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32427-9 Erratum in: Corrected: Progress in adolescent health and wellbeing: tracking 12 headline indicators for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016. The Lancet [Internet]. 2019 Mar 23[cited 2025 Apr 3];393(10177):1204. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673619305781 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30578-1 . In Latin America, as of 2015, approximately 2.5 million girls aged 10 to 14 gave birth annually [4] Neal S, Matthews Z, Frost M, Fogstad H, Camacho AV, Laski L. Childbearing in adolescents aged 12–15 years in low resource countries: a neglected issue. New estimates from demographic and household surveys in 42 countries. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand [Internet]. 2012 May 23 [cited 2025 Mar 25];91(9):1114–8. Available from: https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01467.x https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01467.x . In Sub-Saharan Africa, the case is not any better [5] Ahinkorah BO, Kang M, Perry L, Brooks F, Hayen A. Prevalence of first adolescent pregnancy and its associated factors in sub-Saharan Africa: A multi-country analysis. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2021 Feb 4 [cited 2025 Mar 25];16(2):e0246308. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246308 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246308 [6] Neal S, Channon AA, Chandra-Mouli V, Madise N. Trends in adolescent first births in sub-Saharan Africa: a tale of increasing inequity? Int J Equity Health [Internet]. 2020 Sep 4 [cited 2025 Mar 25];19(1):151. Available from: https://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12939-020-01251-y https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-01251-y . This region has the highest adolescent birth rate, with 97 births per 1,000 women. In 2023, over 6 million childbirths occurred to girls aged 15–19 years, and more than 300,000 births in 10–14 years, the highest numbers globally [2] World Health Organization. Adolescent pregnancy [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2024 Apr 10[cited 2025 Mar 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy .

In Ghana, the period prevalence of late adolescent pregnancies (15-19 years) over 30 years, was 15.4 childbirths per 1000 (95% CI 13.49 – 17.30) with higher prevalence in rural areas [7] Mohammed S. Analysis of national and subnational prevalence of adolescent pregnancy and changes in the associated sexual behaviours and sociodemographic determinants across three decades in Ghana, 1988–2019. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2023 Mar 17[cited 2025 Mar 25];13(3):e068117. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068117 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068117 . Savannah Region has one of the lowest prevalence of adolescent pregnancies in Ghana [8] DHIMS 2 [Internet]. Accra (Ghana): Ministry of Health (Ghana), Centre for Health Information Management. [date unknown]- [cited 2025 Mar 25]. Available from: https://dhims.chimgh.org/dhims/dhis-web-commons/security/login.action . However, the region’s low population density, combined with its youthful demographic, high population growth rate, and the prevalence of certain sociocultural practices among some tribes, invites further review of the facts. It is home to the largest confluence of the Fulani population in Ghana, among who studies have shown high rates of child marriages [9] Mobolaji JW, Fatusi AO, Adedini SA. Ethnicity, religious affiliation and girl-child marriage: a cross-sectional study of nationally representative sample of female adolescents in Nigeria. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2020 Apr 29 [cited 2025 Mar 25];20(1):583. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-020-08714-5 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08714-5 .

Thematic analysis revealed that factors such as early marriage, sexual risk behaviours, a family history of adolescent pregnancy, peer pressure, and limited access to reproductive health services, contribute to the rising incidence of adolescent pregnancies [10] Chung HW, Kim EM, Lee J. Comprehensive understanding of risk and protective factors related to adolescent pregnancy in low‐ and middle‐income countries: A systematic review. Journal of Adolescence [Internet]. 2018 Oct 26[cited 2025 Mar 25];69(1):180–8. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.10.007 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.10.007 Subscription or purchase required to view full text. . Adolescent pregnancies have been shown to have a profound effect on the socioeconomic, physical, and mental development of the girls involved, as well as the society, and the nation as a whole. Maternal and perinatal complications are notably more severe in this population [11] Finlay JE, Norton MK, Guevara IM. Adolescent fertility and child health: the interaction of maternal age, parity and birth intervals in determining child health outcomes. International Journal of Child Health and Nutrition [Internet]. 2017 Mar 16 [cited 2025 Mar 25];6(1):16–33. Available from: https://lifescienceglobal.com/pms/index.php/ijchn/article/view/4472/2547 https://doi.org/10.6000/1929-4247.2017.06.01.2 [12] Xie Y, Wang X, Mu Y, Liu Z, Wang Y, Li X, Dai L, Li Q, Li M, Chen P, Zhu J, Liang J. Characteristics and adverse outcomes of Chinese adolescent pregnancies between 2012 and 2019. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2021 Jun 15 [cited 2025 Mar 25];11(1):12508. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-92037-x https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92037-x [13] Yussif AS, Lassey A, Ganyaglo GY kumah, Kantelhardt EJ, Kielstein H. The long-term effects of adolescent pregnancies in a community in Northern Ghana on subsequent pregnancies and births of the young mothers. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2017 Dec 29 [cited 2025 Mar 25];14(1):178. Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-017-0443-x https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0443-x . To emphasize adolescents’ reproductive health in most policy initiatives among specific youth age groups, the 10-14 age group was included in the Sustainable Development Goals indicator framework for reproductive health by the United Nations General Assembly in July 2017 [14] MacQuarrie KL, Mallick L, Allen C. Sexual and Reproductive Health in Early and Later Adolescence: DHS Data on Youth Age 10-19 [Internet]. Washington (DC): United States Agency for International Development; 2017 Aug [cited 2025 Mar 25]. 100 p. DHS Comparative Reports No. 45. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-cr45-comparative-reports.cfm Download pdf to view full text. . This contributed to the progress made in reducing the prevalence of adolescent pregnancies globally [15] Akombi-Inyang BJ, Woolley E, Iheanacho CO, Bayaraa K, Ghimire PR. Regional trends and socioeconomic predictors of adolescent pregnancy in Nigeria: A Nationwide Study. IJERPH [Internet]. 2022 Jul 5 [cited 2025 Mar 25];19(13):8222. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/13/8222 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138222 [16] Monteiro DLM, Martins JAFDS, Rodrigues NCP, Miranda FRDD, Lacerda IMS, Souza FMD, Wong ACT, Raupp RM, Trajano AJB. Adolescent pregnancy trends in the last decade. Rev Assoc Med Bras [Internet]. 2019 Oct 10 [cited 2025 Mar 25];65(9):1209–15. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0104-42302019000901209&tlng=en https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.65.9.1209 from 45.7 in 2017 to 41.9 [17] World Bank Group. The Social and Educational Consequences of Adolescent Childbearing [Internet]. Washington (DC): World Bank Group; 2022 Feb 25 [cited 2025 Mar 25]. Available from: https://genderdata.worldbank.org/en/data-stories/adolescent-fertility . Nevertheless, there remains some variability in progress across age groups and different populations [2] World Health Organization. Adolescent pregnancy [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2024 Apr 10[cited 2025 Mar 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy . For example, countries like Niger and Chad continue to have a very highest prevalence of ABR in late adolescents and about 6% reduction since, 2017. These countries still do not have reliable conclusions about the early adolescent group [17] World Bank Group. The Social and Educational Consequences of Adolescent Childbearing [Internet]. Washington (DC): World Bank Group; 2022 Feb 25 [cited 2025 Mar 25]. Available from: https://genderdata.worldbank.org/en/data-stories/adolescent-fertility .

Some studies on adolescent pregnancy trends involve long-term data reviews with some researchers focusing on the 15-19 age group to conform to certain standards [18] Mutea L, Were V, Ontiri S, Michielsen K, Gichangi P. Trends and determinants of adolescent pregnancy: Results from Kenya demographic health surveys 2003–2014. BMC Women’s Health [Internet]. 2022 Oct 10 [cited 2025 Mar 25];22(1):416. Available from: https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12905-022-01986-6 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01986-6 . These do not show real-time trends and do not consider the early adolescent risk group. For instance, a study in Kenya revealed that approximately one million adolescent pregnancies were missed over 11 years [18] Mutea L, Were V, Ontiri S, Michielsen K, Gichangi P. Trends and determinants of adolescent pregnancy: Results from Kenya demographic health surveys 2003–2014. BMC Women’s Health [Internet]. 2022 Oct 10 [cited 2025 Mar 25];22(1):416. Available from: https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12905-022-01986-6 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01986-6 . The lengthy periods of study and the marginalized focus of these studies underscore the need to understand the age-specific prevalence in perspective. This will help trigger the significance of improved data collection across all age groups, and to develop targeted public health policies and interventions to reduce the incidence of adolescent pregnancies.

In Ghana and other similar populations, studies on adolescent pregnancies typically focus on cause-and-effect factors [13] Yussif AS, Lassey A, Ganyaglo GY kumah, Kantelhardt EJ, Kielstein H. The long-term effects of adolescent pregnancies in a community in Northern Ghana on subsequent pregnancies and births of the young mothers. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2017 Dec 29 [cited 2025 Mar 25];14(1):178. Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-017-0443-x https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0443-x [19] Amoadu M, Ansah EW, Assopiah P, Acquah P, Ansah JE, Berchie E, Hagan D, Amoah E. Socio-cultural factors influencing adolescent pregnancy in Ghana: a scoping review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet]. 2022 Nov 11 [cited 2025 Mar 25];22(1):834. Available from: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-022-05172-2 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-05172-2 [20] Bain LE, Muftugil-Yalcin S, Amoakoh-Coleman M, Zweekhorst MBM, Becquet R, De Cock Buning T. Decision-making preferences and risk factors regarding early adolescent pregnancy in Ghana: stakeholders’ and adolescents’ perspectives from a vignette-based qualitative study. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2020 Sep 11[cited 2025 Mar 25];17(1):141. Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-020-00992-x https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-00992-x . Among these socioeconomic and sociocultural factors have shown strong associations [19] Amoadu M, Ansah EW, Assopiah P, Acquah P, Ansah JE, Berchie E, Hagan D, Amoah E. Socio-cultural factors influencing adolescent pregnancy in Ghana: a scoping review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet]. 2022 Nov 11 [cited 2025 Mar 25];22(1):834. Available from: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-022-05172-2 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-05172-2 . Few studies however examine trends in reduction within the country, specific age groups, and regions, such as the Savannah region [7] Mohammed S. Analysis of national and subnational prevalence of adolescent pregnancy and changes in the associated sexual behaviours and sociodemographic determinants across three decades in Ghana, 1988–2019. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2023 Mar 17[cited 2025 Mar 25];13(3):e068117. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068117 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068117 [21] . Ahinkorah BO, Kang M, Perry L, Brooks F. Knowledge and awareness of policies and programmes to reduce adolescent pregnancy in Ghana: a qualitative study among key stakeholders. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2023 Sep 22 [cited 2025 Mar 25];20(1):143. Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-023-01672-2 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-023-01672-2 .

This manuscript presents a comprehensive analysis of the trends in adolescent pregnancies among different age groups across the Savannah region and in its various districts. It provides a foundation for understanding the progress in reducing the burden of adolescent pregnancies in the region. The analysis includes the period prevalence, the average rate of change in adolescent pregnancy over the five-year period, and the age-specific adolescent birth rate in the Savannah region.

Methods

Study design

The study utilized a cross-sectional design. Data on all antenatal care (ANC) registrants from all health facilities in the Savannah region of Ghana, as recorded in the DHIMS-2 registry between 2018 and 2022, were included in this study.

Study setting

The study was conducted in the Savannah Region, one of two regions carved out of the Northern Region in 2019 [22]. The region has the largest land area in Ghana covering approximately 15% of the total surface area [22].

The region has the lowest population density in the country and one of the fastest rates of population growth in the country at 3.1% [22]. Approximately 70% of the population are rural [22]. With female populations marginally exceeding the male population, the region is one of the few still with a very slow transition into a youthful population [22]. Most populations in the region are child populations [22]. The region has one of the highest total fertility rates (TFR) among rural populations in the country [22].

The region like any rural-dominated region in the country has subsistence agriculture as the main socio-economic activity. Together with the other two Northern regions, it is categorized as the only region in Ghana with below average Human Development Index (HDI) [23].

Operational definitions

Age-specific birth rate (ASBR): It is the ratio of the total number of live births born to women within a specific age category to the mid-year population of women in the age bracket for a given country, territory, or geographic area, during a specified period, usually multiplied by 1,000.

Average rate of change: It is a measure of how much a function changed per unit, on average, over that interval. It is calculated from the difference in the function over the interval’s endpoints expressed as a fraction of the change in time Mathematically;

$$A_x = \frac{\sum (f(b) – f(a))}{\Delta t}$$

Where;

Ax – Average rate of change

f(a) – function of ‘a’

F(b) –function of ‘b’

t – change in time

Data collection and management

Data of all adolescent antenatal mothers at registration, along with the population of Savannah Region by year, sex, and age categories, from 2018 to 2022 were extracted onto an Excel spreadsheet and restructured. The data was categorized into two age groups-early adolescent (10-14) and late adolescent (15-19) and further broken down by districts.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel 2018. First, we estimated the risk populations for each year from the DHIMS 2 platform, using the projected population data entered into the system. To determine the proportion of Women in Fertility Age (WIFA), we calculated 24% of the female population. Using projected population growth rates of 10.2% for early adolescents and 9.9% for late adolescents [22], we estimated the risk population for each age group. Next, we calculated the specific Birth Rate (ASBR) per 1,000 adolescent girls in the population at 95% confidence interval. We also determined the period prevalence and the average rate of change in ASBR. The rate of change in ASBR from one year to another was assessed for each district, and an average rate of change was calculated. Variations in trends of ASBR across different districts and age categories were graphically represented with bar and line graphs to illustrate these trends and a map using QGIS.

Ethical consideration

The Savannah Regional Health Directorate (SRHD) of the Ghana Health Services (GHS) granted the access and administrative approval to the dataset. The institution is required by the Public Health Act 2012 to ensure accurate data capture and dissemination of all important public health diseases and events reported on the various surveillance data platforms in the country like the DHIMS -2. No formal ethical approval was required for this study since it aligned to the institution’s mandate. Extracted aggregated data from the DHIMS-2 without any patient identification markers was kept on a password-protected personal computer of the lead researcher and only available to the research team of the Savannah region on request.

Results

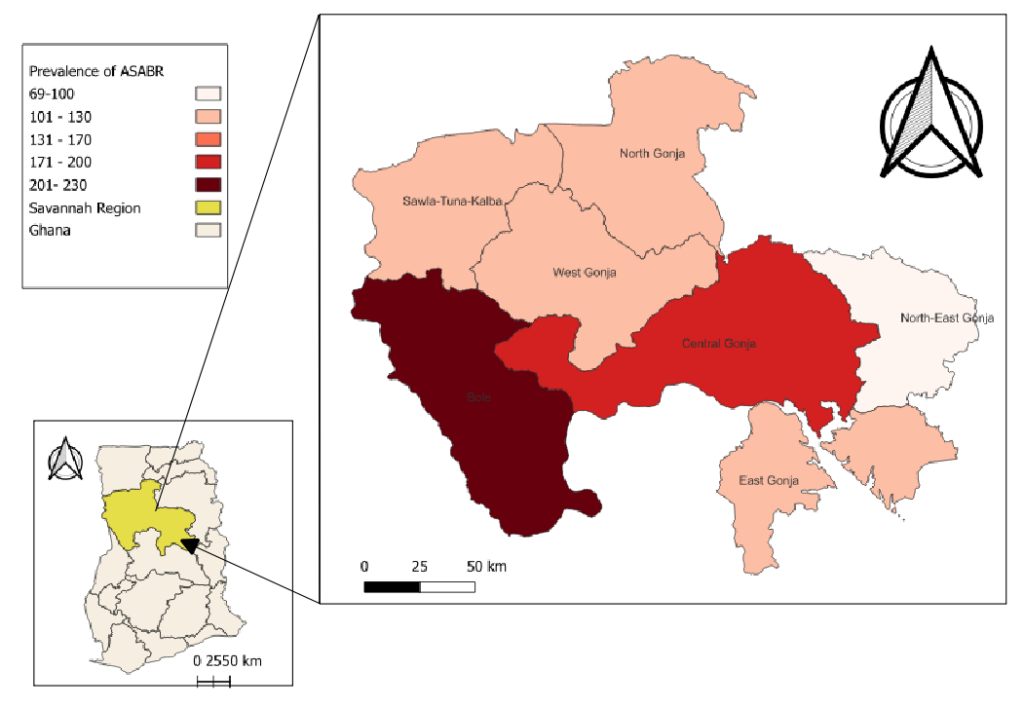

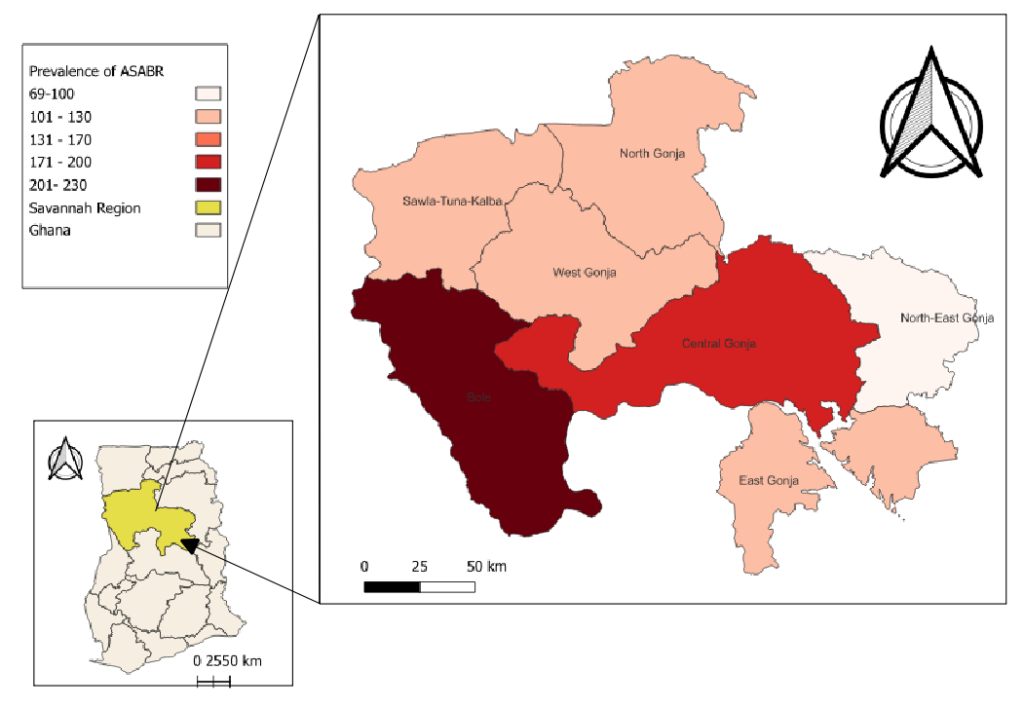

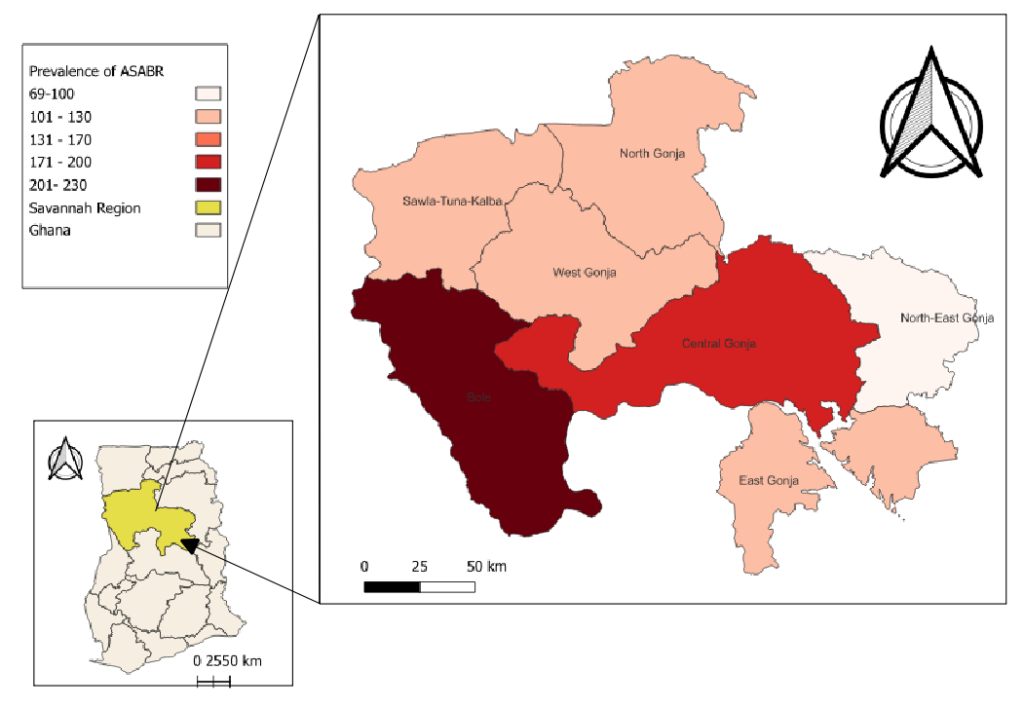

We found a total of 16,906 adolescent mothers at ANC registration were recorded over the 5 years (2018 – 2022). The period prevalence of adolescent pregnancies was 117.50 childbirths per 1000 women (95% CI of 102.17 – 131.92) as shown in Figure 1. Within the districts, adolescent pregnancies in the Savannah region were highest in the Bole District, 230 childbirths per 1000 women (95%CI; 165-296) followed by Central Gonja District with 190 (95% CI; 147-232) childbirths per 1000 women. Sawla-Tuna-Kalba, North Gonja, West Gonja and the East Gonja Districts followed with rates of 109 (95% CI; 99-118), 105 (95% CI; 95-114), 117 (95% CI; 89-145) and 119 (95%CI; 70-168) child births per 1000 women respectively. The North-East Gonja district recorded the least with 69 (95%CI; 49-88) childbirths per 1000 women as shown in Figure 2.

We found that among age specific groups, the period prevalence among girls aged 10 – 14 years was 6.57 childbirths per 1,000 women (95% CI: 3.46–9.68) and among girls 15 – 19 years was 230 childbirths per 1,000 women (95% CI of 165. 13 – 296.01).

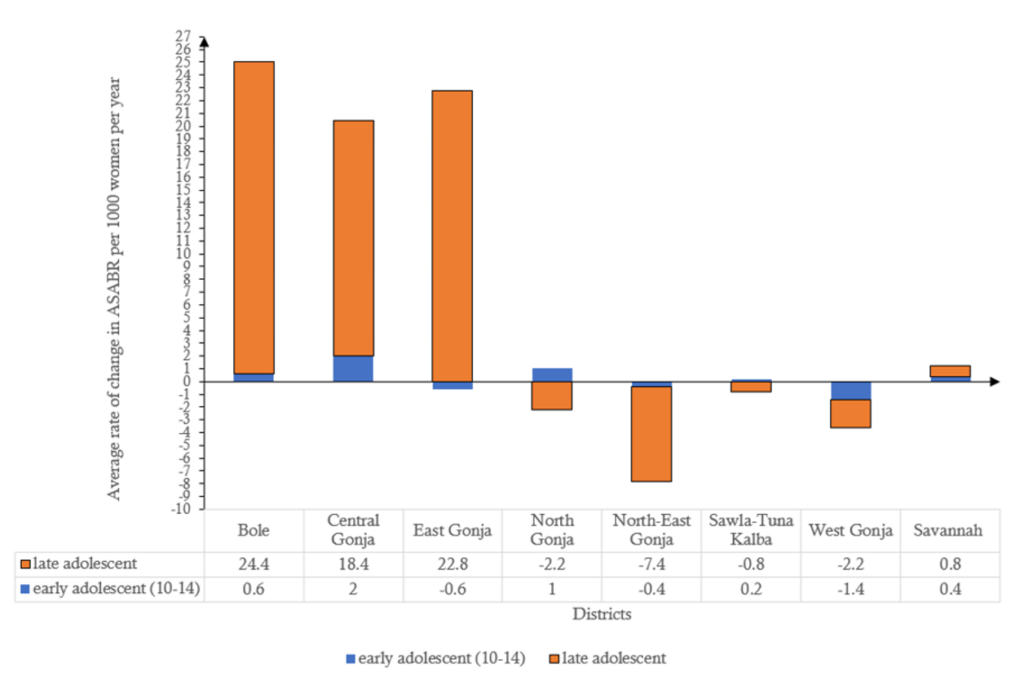

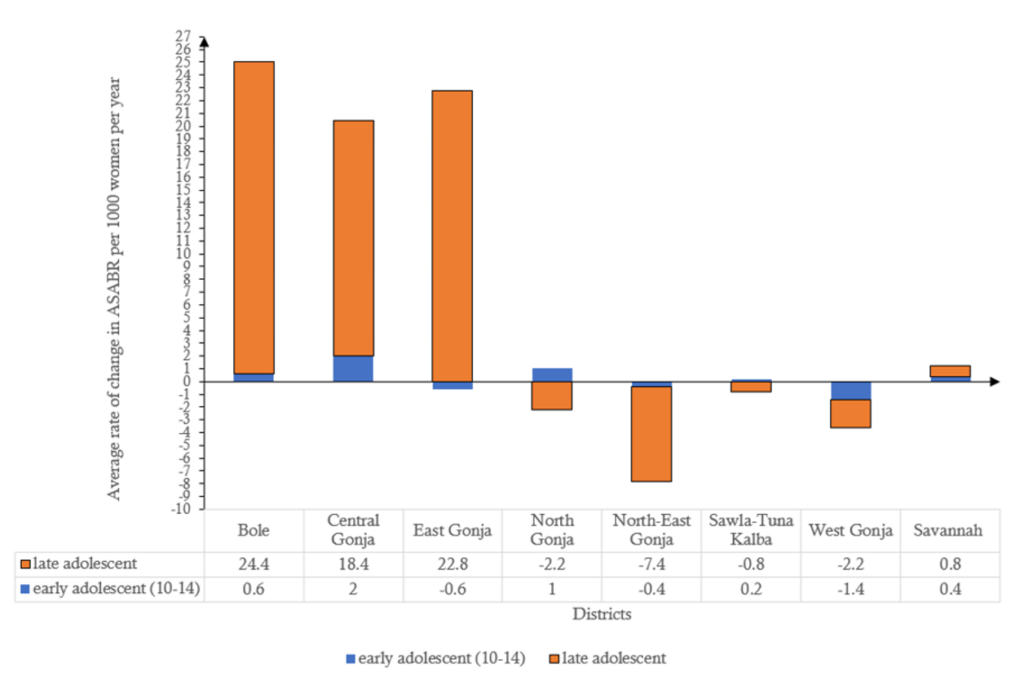

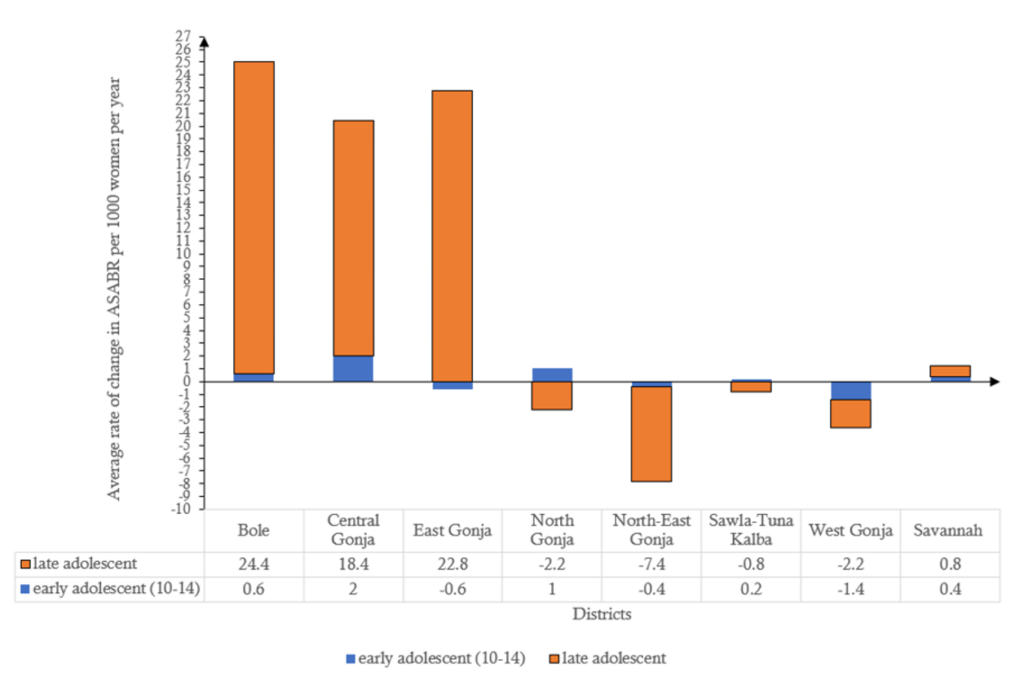

In terms of reduction in the prevalence of adolescent birth ratio (ABR), we found that there was generally a positive reduction in the Savannah region of +1.2 childbirths per 1000 women per year (Figure 3). Within the districts approximately 40% (3/7) including, Bole, Central Gonja and East Gonja recorded positive reductions at +25.0, +18.6, and +22.2 childbirths per 1000 women per year respectively. Proportionately, the remaining 60% (4/7) of the districts, North Gonja, North-East Gonja, Sawla-Tuna-Kalba and the West Gonja districts recorded negative reductions at -1.2, -7.8, -0.6, and -3.6 childbirths per 1000 women per year respectively (Figure 3).

Introspectively, we also fund that the Bole and Central Gonja Districts recorded positive reductions in both early (+0.6, +2.0) and late (+24.4, +18.4) adolescent pregnancies respectively. Negative reductions were also seen in two districts, West Gonja and North- East Gonja in both early (-1.4, -0.4) and late (-2.2, -7.4) adolescent pregnancies respectively. North Gonja and Sawla-Tuna- Kalba demonstrated a positive reduction in early (+1.0, +0.2) and a negative reduction for late (-2.2, -0.8) adolescent pregnancies respectively. East Gonja however also showed positive reduction for late adolescents (+22.8) and negative reduction for early adolescents (-0.6). Proportionately, about 60% (4/7) of the districts had positive reduction dynamic in the 5-year period among early adolescents, with the least occurring in Sawla-Tuna-Kalba (-0.2) and the most in Central Gonja Disrict (+2.0). Among late adolescents, about 40% (3/7) of the districts had positive reductions, the highest occurred in the Bole district (+22.4) and the least in the Central Gonja District (+18.4).

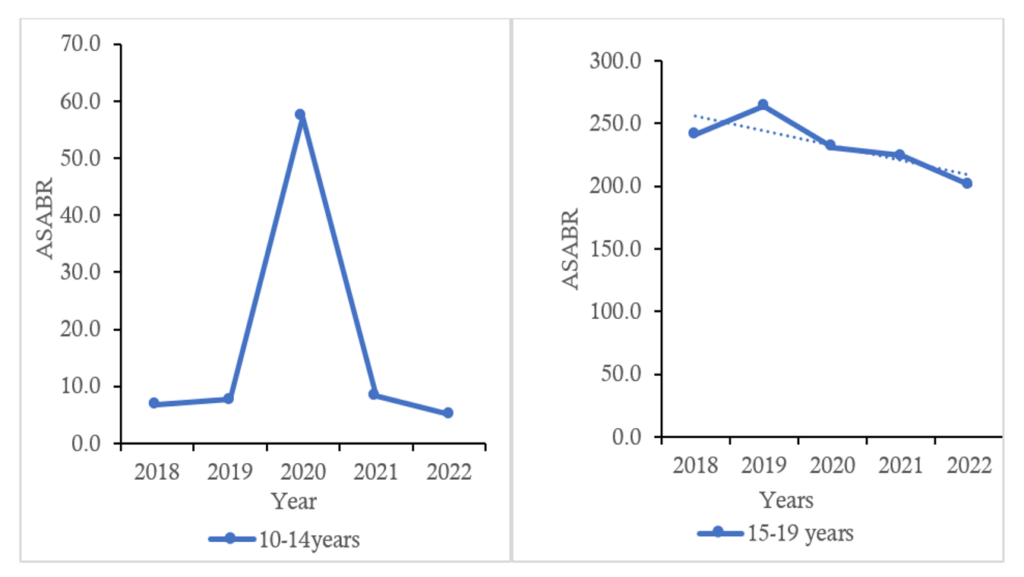

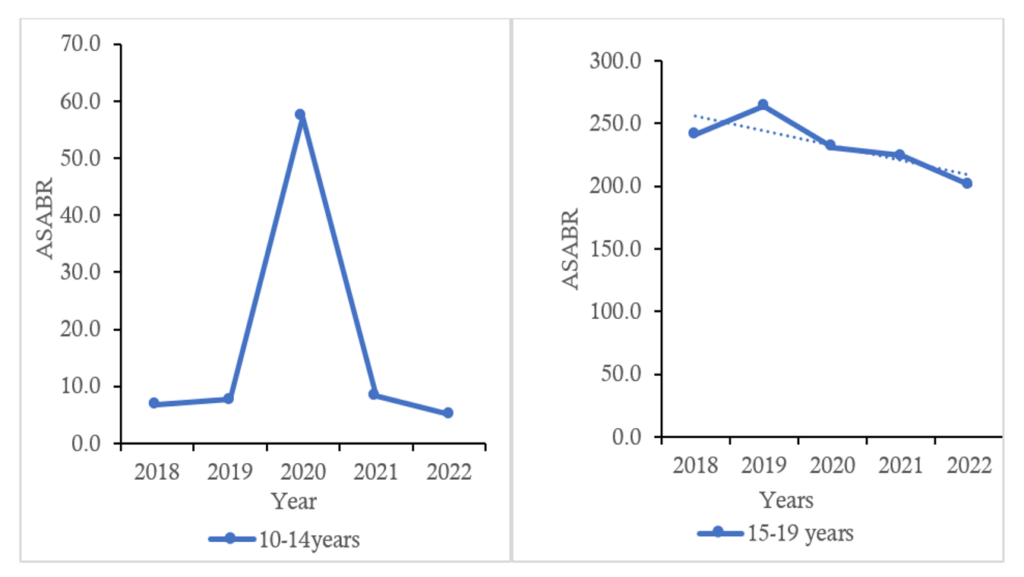

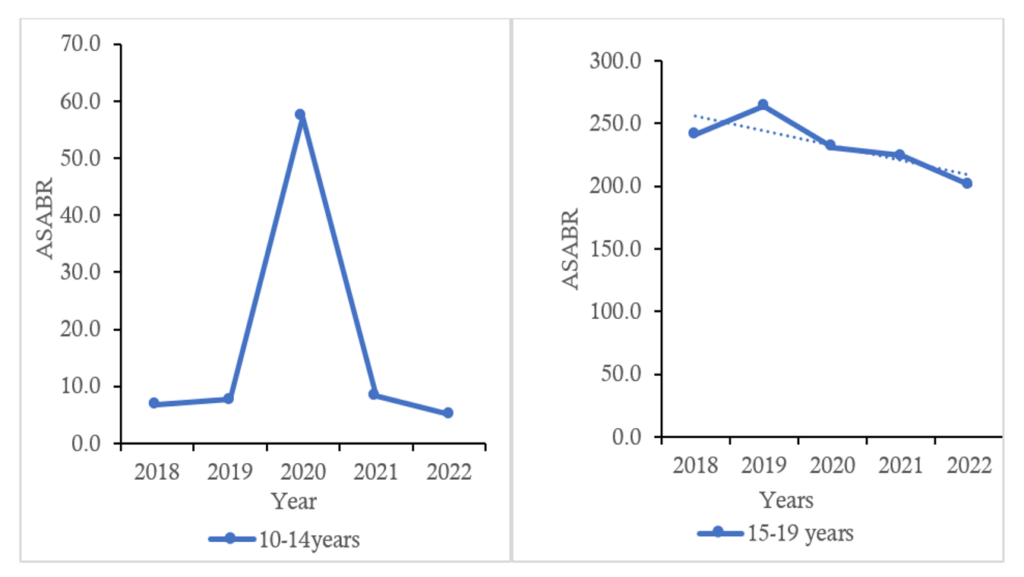

Among the age-specific groups, there was a very steady slow trend in reduction among early adolescents in all the years except 2020 where there was about 6-fold increase in the prevalence of ASABR as shown in Figure 4. Late adolescents showed a significantly consistent reduction since 2018 with a slight increase in 2019 compared to the reduction observed in early adolescents (Figure 4).

Discussion

Savannah region has a high period prevalence of adolescent pregnancy. This is almost consistent with global estimates of 100 per 1000 risk population [23] United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2019: Beyond income, beyond averages, beyond today: Inequalities in human development in the 21st century [Internet]. New York (NY): United Nations Development Programs; 2019 Dec 9 [cited 2025 Mar 26]. 350 p. Available from: https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/hdr2019.pdf Download hdr2019.pdf for Africa. In Ghana, this is above the prevalence of 59 childbirths per every 1000 women estimated by the world bank Gender data in 2022 [17] World Bank Group. The Social and Educational Consequences of Adolescent Childbearing [Internet]. Washington (DC): World Bank Group; 2022 Feb 25 [cited 2025 Mar 25]. Available from: https://genderdata.worldbank.org/en/data-stories/adolescent-fertility . This clearly provides a benchmark to justify the conclusion drawn in this report that though it did not consider pregnancies in early adolescents unlike this study, regional variability within the country, could have accounted for the difference. Again, the prevalence in the Savannah region comparative to the findings in a three-year study on regional trends in Nigeria’s political zones is low. This study found about 22% increased prevalence in adolescent childbirths [24] Ikotun O. Gendered Insecurity and Mobility in West African Borderlands: Putting the Nigeria/Niger Border in Perspective. In: Okunade SK, Ogunnubi O, editors. ECOWAS Protocol on Free Movement and the AfCFTA in West Africa: Costs, Benefits and Challenges [Internet]. Singapore(SGP): Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore; 2023 May 14[cited 2026 Mar 26]. p. 45–70. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-981-19-5005-6_3 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5005-6_3 .

The prevalence of 230 childbirths per 1000 women among late adolescents is more than twice the estimated prevalence for Sub-Saharan Africa. Its however consistent with the findings from Mohammed in 2023 [7] Mohammed S. Analysis of national and subnational prevalence of adolescent pregnancy and changes in the associated sexual behaviours and sociodemographic determinants across three decades in Ghana, 1988–2019. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2023 Mar 17[cited 2025 Mar 25];13(3):e068117. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068117 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068117 . He stated that late adolescent pregnancies are higher in rural Ghana compared to urban cities. The Savannah region in context is predominantly rural. Furthermore in the Sub-Region, Barron et al in their five-year analysis of public sector data on teen births and pregnancies in the South Africa, also found adolescent pregnancies in late teens to be increase by approximately 18% [25] Barron P, Subedar H, Letsoko M, Makua M, Pillay Y. Teenage births and pregnancies in South Africa, 2017 – 2021 – a reflection of a troubled country: Analysis of public sector data. SAMJ [Internet]. 2022 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Mar 26];112(4):252–8. Available from: https://journals.co.za/doi/full/10.7196/SAMJ.2022.v112i4.16327 https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2022.v112i4.16327 . In accessing the geographic variations and risk factors for teenage pregnancies in Uganda over a five-year period, Byonanebye et al, also found late adolescent pregnancies demonstrably increased with regional variability [26] Byonanebye J, Brazauskas R, Tumwesigye N, Young S, May T, Cassidy L. Geographic variation and risk factors for teenage pregnancy in Uganda. Afr H Sci [Internet]. 2020 Dec 16 [cited 2025 Mar 26];20(4):1898–907. Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ahs/article/view/202361 https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v20i4.48 . Musinguzi et al on the contrary concluded that prevalence of adolescent pregnancies decreases with increasing age [27] Musinguzi M, Kumakech E, Auma AG, Akello RA, Kigongo E, Tumwesigye R, Opio B, Kabunga A, Omech B. Prevalence and correlates of teenage pregnancy among in-school teenagers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Hoima district western Uganda–A cross-sectional community-based study. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2022 Dec 16 [cited 2025 Mar 26];17(12):e0278772. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278772 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278772 . This study however was conducted among only school-going girls. This could have influenced his finding since most school going girls do not end up pregnant within the time they are in school.

The ASABR among the early adolescent group peaked in 2020 whilst the late adolescent groups peaked in 2019. It can be inferred that the COVID-19 pandemic is largely accountable for the observed increase. Pursuant to the this there were concurrent lockdowns which provided the right avenue for the observed situation. Girls who stayed out of school were found to be twice more likely to get pregnant compared to those who graduated before the COVID-19 pandemic [28] Zulaika G, Bulbarelli M, Nyothach E, Van Eijk A, Mason L, Fwaya E, Obor D, Kwaro D, Wang D, Mehta SD, Phillips-Howard PA. Impact of COVID-19 lockdowns on adolescent pregnancy and school dropout among secondary schoolgirls in Kenya. BMJ Glob Health [Internet]. 2022 Jan 13[cited 2025 Mar 26];7(1):e007666. Available from: https://gh.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007666 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007666 . The peaked prevalence in turn can also be attributed to the prioritization of early adolescent age-group into policy initiatives [2] World Health Organization. Adolescent pregnancy [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2024 Apr 10[cited 2025 Mar 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy . This could have rendered most pregnancies accounted for due to improved data capture and record keeping.

There was significant variability observed among the districts in terms of prevalence. North-East Gonja and West Gonja are the only districts showing negative progress in both early and late adolescent pregnancies. This may be due to the fact that West Gonja, located in the heart of the regional capital, is heavily affected by migration in and out of the district. Again, the district has the potential to benefit from prioritized interventions, such as improving girl-child education (which has been linked to a reduction in adolescent pregnancies) [27] Musinguzi M, Kumakech E, Auma AG, Akello RA, Kigongo E, Tumwesigye R, Opio B, Kabunga A, Omech B. Prevalence and correlates of teenage pregnancy among in-school teenagers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Hoima district western Uganda–A cross-sectional community-based study. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2022 Dec 16 [cited 2025 Mar 26];17(12):e0278772. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278772 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278772 , it is primarily urban. Studies have shown that adolescent pregnancies tend to be lower in urban areas [7] Mohammed S. Analysis of national and subnational prevalence of adolescent pregnancy and changes in the associated sexual behaviours and sociodemographic determinants across three decades in Ghana, 1988–2019. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2023 Mar 17[cited 2025 Mar 25];13(3):e068117. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068117 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068117 . On the other hand, North-East Gonja is a typically rural district and one of the newly created districts in the country. It lacks a hospital, with only primary healthcare facilities such as a health center and Community-based Health Planning and Services (CHPS) compounds. The district also faces challenges in terms of educational infrastructure. With these characteristics, coupled with the district’s smallest population in the Savannah region, the findings are understandable and unlikely to be contested.

Bole, despite having the highest adolescent birth rate (ABR), showed the most significant positive change, particularly among late adolescents. This could be because districts with a higher prevalence tend to demonstrate the most progress and are given the highest priority [24] Ikotun O. Gendered Insecurity and Mobility in West African Borderlands: Putting the Nigeria/Niger Border in Perspective. In: Okunade SK, Ogunnubi O, editors. ECOWAS Protocol on Free Movement and the AfCFTA in West Africa: Costs, Benefits and Challenges [Internet]. Singapore(SGP): Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore; 2023 May 14[cited 2026 Mar 26]. p. 45–70. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-981-19-5005-6_3 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5005-6_3 . The socio-economic characteristics could in part contribute to this finding. The district serves as a major hub for small-scale mining activities which has shown to be a factor in increasing teenage pregnancy in some communities in the country [29] Wireko-Gyebi RS, King RS, Braimah I, Lykke AM. Local knowledge of risks associated with artisanal small-scale mining in Ghana. Int J Occup Saf Ergon [Internet]. 2020 Aug 27 [cited 2025 Mar 26];28(1):528–35. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10803548.2020.1795374 https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2020.1795374 ,[30] Mensah J, Amoah JO, Nketsiah‐Essoun A. Effects of artisanal gold mining and routes towards sustainable development for a low‐profile mining community in Ghana. Natural Resources Forum [Internet]. 2024 Mar 13 [cited 2025 Mar 26];1477-8947.12431. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1477-8947.12431 https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-8947.12431 Purchase or subscription required to view full text. . Again, being a gateway into the country from La Cote d’Ivoire also provides another recipe for the thriving of this situation. Women are targets of sexual insecurities in the borderlands [24] Ikotun O. Gendered Insecurity and Mobility in West African Borderlands: Putting the Nigeria/Niger Border in Perspective. In: Okunade SK, Ogunnubi O, editors. ECOWAS Protocol on Free Movement and the AfCFTA in West Africa: Costs, Benefits and Challenges [Internet]. Singapore(SGP): Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore; 2023 May 14[cited 2026 Mar 26]. p. 45–70. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-981-19-5005-6_3 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5005-6_3 . This situation is consistent with Gay et al.’s findings, which highlight the impact of community exposure to the mining industry. In addition to tobacco and alcohol use, other behavioral issues linked to adolescence were found to be significant in such communities [31] Gay C, Clements‐Nolle K, Packham J, Ackerman G, Lensch T, Yang W. Community‐level exposure to the rural mining industry: the potential influence on early adolescent alcohol and tobacco use. The Journal of Rural Health [Internet]. 2018 Jan 31 [cited 2025 Mar 26];34(3):304–13. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jrh.12288 https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12288 . Although the prevalence of early adolescent pregnancies is comparatively low, the moral concern of seeing even one child under 15 years who probably may not be capable of making rational decisions pregnant, is unacceptable. Dahmen et al., 2019 in their study on mental health of adolescents, also concluded that early pregnancies have negative effects on mother-child relationships and the psychosocial and mental development of the children, as both mothers and their children are still in the process of development [32] Dahmen B, Konrad K, Jahnen L, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Firk C. Psychische Gesundheit von Teenagermüttern: Auswirkungen auf die nächste Generation [Teenage Mothers’ Mental Health: Impact on the Next Generation]. Nervenarzt [Internet]. 2019 Jan 14 [cited 2025 Mar 26];90(3):243–50. German. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00115-018-0661-7 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-018-0661-7 Purchase or subscription required to view full text. .

Limitations

The prevalence recorded in this study could be underestimated because only pregnancies at registration were considered. Abortions, unregistered pregnancies, and deliveries at home or with traditional birth attendants (TBAs) in the region were not included, as these data sources are not accessible on the DHIMS2 platform. Although no discrepancies were found in the data extracted, the study is still subject to the limitations of using secondary data. However, we ensured the data’s accuracy by confirming its up-to-date status with the reporting sources.

Conclusion

The period prevalence of adolescent pregnancies in the Savannah region over five years is high above global estimates for developing countries. Prevalence is highest in the Bole district. The prevalence of early adolescent pregnancy in the region has the least remarkable trend to it. Interventions and policies to control the situation should be focused on both age groups in all districts in the region with priority to highly burdened sections with unremarkable reducing trends. Interventions and policies to control the situation should be focused on both age groups in all districts in the region with priority to highly burdened sections with unremarkable reducing trends to their progress. The age-specific directed approach should be employed.

What is already known about the topic

- A reduction in trend of adolescent birth rate is necessary for achieving reproductive health goal for sustainable development.

- Understanding adolescent birth rate in all age categories is necessary to unify inclusion of adolescents into policy initiatives

What this study adds

- This study found a reducing trend in adolescent birth-rate in the Savannah region from 2018-2022.

- This study also found very slow progress in reducing early adolescent births and supports the need for age-specific targeted reproductive health interventions in the Savannah region with priority to high-burdened districts with slower reductions

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Savannah Regional Health Directorate for sponsoring the manuscript write-up workshop that produced this manuscript and the Savannah Regional Health Research Team for the assistance with data extraction and restructuring as well as the permission to use this data for the manuscript. Also, the Ghana Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program (GFELTP) and the University of Ghana Legon School of Public Health for assistance with manuscript write-ups and reviews.

Authors´ contributions

Ballu Cletus and Kubio Chrysantus conceptualized the study, Kubio Chrysantus extracted the data, Gyasi Ophelia Apau and Ballu Cletus analysis the data. Ballu Cletus drafted the manuscript. MO, Akowuah George, Gyesi Razak Issahaku, Kubio Chrysantus, Bandoh Delia Akosuah, Gyasi Ophelia Apau and Kenu Ernest reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- United Nations Population Fund. Adolescent pregnancy [Internet]. New York (NY): United Nations Population Fund; c2025 [cited 2025 Mar 25]. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/adolescent-pregnancy#readmore-expand

- World Health Organization. Adolescent pregnancy [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2024 Apr 10[cited 2025 Mar 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy

- Azzopardi PS, Hearps SJC, Francis KL, Kennedy EC, Mokdad AH, Kassebaum NJ, Lim S, Irvine CMS, Vos T, Brown AD, Dogra S, Kinner SA, Kaoma NS, Naguib M, Reavley NJ, Requejo J, Santelli JS, Sawyer SM, Skirbekk V, Temmerman M, Tewhaiti-Smith J, Ward JL, Viner RM, Patton GC. Progress in adolescent health and wellbeing: tracking 12 headline indicators for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016. The Lancet [Internet]. 2019 Mar 12[cited 2025 Mar 25];393(10176):1101–18. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673618324279 https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32427-9 Erratum in: Corrected: Progress in adolescent health and wellbeing: tracking 12 headline indicators for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016. The Lancet [Internet]. 2019 Mar 23[cited 2025 Apr 3];393(10177):1204. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673619305781 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30578-1

- Neal S, Matthews Z, Frost M, Fogstad H, Camacho AV, Laski L. Childbearing in adolescents aged 12–15 years in low resource countries: a neglected issue. New estimates from demographic and household surveys in 42 countries. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand [Internet]. 2012 May 23 [cited 2025 Mar 25];91(9):1114–8. Available from: https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01467.xhttps://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01467.x

- Ahinkorah BO, Kang M, Perry L, Brooks F, Hayen A. Prevalence of first adolescent pregnancy and its associated factors in sub-Saharan Africa: A multi-country analysis. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2021 Feb 4 [cited 2025 Mar 25];16(2):e0246308. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246308 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246308

- Neal S, Channon AA, Chandra-Mouli V, Madise N. Trends in adolescent first births in sub-Saharan Africa: a tale of increasing inequity? Int J Equity Health [Internet]. 2020 Sep 4 [cited 2025 Mar 25];19(1):151. Available from: https://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12939-020-01251-y https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-01251-y

- Mohammed S. Analysis of national and subnational prevalence of adolescent pregnancy and changes in the associated sexual behaviours and sociodemographic determinants across three decades in Ghana, 1988–2019. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2023 Mar 17[cited 2025 Mar 25];13(3):e068117. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068117 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068117

- DHIMS 2 [Internet]. Accra (Ghana): Ministry of Health (Ghana), Centre for Health Information Management. [date unknown]- [cited 2025 Mar 25]. Available from: https://dhims.chimgh.org/dhims/dhis-web-commons/security/login.action

- Mobolaji JW, Fatusi AO, Adedini SA. Ethnicity, religious affiliation and girl-child marriage: a cross-sectional study of nationally representative sample of female adolescents in Nigeria. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2020 Apr 29 [cited 2025 Mar 25];20(1):583. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-020-08714-5 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08714-5

- Chung HW, Kim EM, Lee J. Comprehensive understanding of risk and protective factors related to adolescent pregnancy in low‐ and middle‐income countries: A systematic review. Journal of Adolescence [Internet]. 2018 Oct 26[cited 2025 Mar 25];69(1):180–8. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.10.007 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.10.007 Subscription or purchase required to view full text.

- Finlay JE, Norton MK, Guevara IM. Adolescent fertility and child health: the interaction of maternal age, parity and birth intervals in determining child health outcomes. International Journal of Child Health and Nutrition [Internet]. 2017 Mar 16 [cited 2025 Mar 25];6(1):16–33. Available from: https://lifescienceglobal.com/pms/index.php/ijchn/article/view/4472/2547 https://doi.org/10.6000/1929-4247.2017.06.01.2

- Xie Y, Wang X, Mu Y, Liu Z, Wang Y, Li X, Dai L, Li Q, Li M, Chen P, Zhu J, Liang J. Characteristics and adverse outcomes of Chinese adolescent pregnancies between 2012 and 2019. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2021 Jun 15 [cited 2025 Mar 25];11(1):12508. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-92037-x https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92037-x

- Yussif AS, Lassey A, Ganyaglo GY kumah, Kantelhardt EJ, Kielstein H. The long-term effects of adolescent pregnancies in a community in Northern Ghana on subsequent pregnancies and births of the young mothers. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2017 Dec 29 [cited 2025 Mar 25];14(1):178. Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-017-0443-xhttps://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0443-x

- MacQuarrie KL, Mallick L, Allen C. Sexual and Reproductive Health in Early and Later Adolescence: DHS Data on Youth Age 10-19 [Internet]. Washington (DC): United States Agency for International Development; 2017 Aug [cited 2025 Mar 25]. 100 p. DHS Comparative Reports No. 45. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-cr45-comparative-reports.cfm Download pdf to view full text.

- Akombi-Inyang BJ, Woolley E, Iheanacho CO, Bayaraa K, Ghimire PR. Regional trends and socioeconomic predictors of adolescent pregnancy in Nigeria: A Nationwide Study. IJERPH [Internet]. 2022 Jul 5 [cited 2025 Mar 25];19(13):8222. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/13/8222 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138222

- Monteiro DLM, Martins JAFDS, Rodrigues NCP, Miranda FRDD, Lacerda IMS, Souza FMD, Wong ACT, Raupp RM, Trajano AJB. Adolescent pregnancy trends in the last decade. Rev Assoc Med Bras [Internet]. 2019 Oct 10 [cited 2025 Mar 25];65(9):1209–15. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0104-42302019000901209&tlng=en https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.65.9.1209

- World Bank Group. The Social and Educational Consequences of Adolescent Childbearing [Internet]. Washington (DC): World Bank Group; 2022 Feb 25 [cited 2025 Mar 25]. Available from: https://genderdata.worldbank.org/en/data-stories/adolescent-fertility

- Mutea L, Were V, Ontiri S, Michielsen K, Gichangi P. Trends and determinants of adolescent pregnancy: Results from Kenya demographic health surveys 2003–2014. BMC Women’s Health [Internet]. 2022 Oct 10 [cited 2025 Mar 25];22(1):416. Available from: https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12905-022-01986-6 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01986-6

- Amoadu M, Ansah EW, Assopiah P, Acquah P, Ansah JE, Berchie E, Hagan D, Amoah E. Socio-cultural factors influencing adolescent pregnancy in Ghana: a scoping review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet]. 2022 Nov 11 [cited 2025 Mar 25];22(1):834. Available from: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-022-05172-2 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-05172-2

- Bain LE, Muftugil-Yalcin S, Amoakoh-Coleman M, Zweekhorst MBM, Becquet R, De Cock Buning T. Decision-making preferences and risk factors regarding early adolescent pregnancy in Ghana: stakeholders’ and adolescents’ perspectives from a vignette-based qualitative study. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2020 Sep 11[cited 2025 Mar 25];17(1):141. Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-020-00992-x https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-00992-x

- Ahinkorah BO, Kang M, Perry L, Brooks F. Knowledge and awareness of policies and programmes to reduce adolescent pregnancy in Ghana: a qualitative study among key stakeholders. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2023 Sep 22 [cited 2025 Mar 25];20(1):143. Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-023-01672-2 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-023-01672-2

- Ghana Statistical Service. Ghana 2021 Population and Housing Census: General Report Volume 3A [Internet]. Accra (Ghana): Ghana Statistical Service; 2021 Nov [cited 2025 Mar 25]. 112 p. Available from: https://statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/fileUpload/pressrelease/2021%20PHC%20General%20Report%20Vol%203A_Population%20of%20Regions%20and%20Districts_181121.pdfDownload 2021 PHC General Report Vol 3A_Population of Regions and Districts_181121.pdf

- United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2019: Beyond income, beyond averages, beyond today: Inequalities in human development in the 21st century [Internet]. New York (NY): United Nations Development Programs; 2019 Dec 9 [cited 2025 Mar 26]. 350 p. Available from: https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/hdr2019.pdf Download hdr2019.pdf

- Ikotun O. Gendered Insecurity and Mobility in West African Borderlands: Putting the Nigeria/Niger Border in Perspective. In: Okunade SK, Ogunnubi O, editors. ECOWAS Protocol on Free Movement and the AfCFTA in West Africa: Costs, Benefits and Challenges [Internet]. Singapore(SGP): Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore; 2023 May 14[cited 2026 Mar 26]. p. 45–70. Available from:https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-981-19-5005-6_3 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5005-6_3

- Barron P, Subedar H, Letsoko M, Makua M, Pillay Y. Teenage births and pregnancies in South Africa, 2017 – 2021 – a reflection of a troubled country: Analysis of public sector data. SAMJ [Internet]. 2022 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Mar 26];112(4):252–8. Available from: https://journals.co.za/doi/full/10.7196/SAMJ.2022.v112i4.16327 https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2022.v112i4.16327

- Byonanebye J, Brazauskas R, Tumwesigye N, Young S, May T, Cassidy L. Geographic variation and risk factors for teenage pregnancy in Uganda. Afr H Sci [Internet]. 2020 Dec 16 [cited 2025 Mar 26];20(4):1898–907. Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ahs/article/view/202361 https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v20i4.48

- Musinguzi M, Kumakech E, Auma AG, Akello RA, Kigongo E, Tumwesigye R, Opio B, Kabunga A, Omech B. Prevalence and correlates of teenage pregnancy among in-school teenagers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Hoima district western Uganda–A cross-sectional community-based study. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2022 Dec 16 [cited 2025 Mar 26];17(12):e0278772. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278772 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278772

- Zulaika G, Bulbarelli M, Nyothach E, Van Eijk A, Mason L, Fwaya E, Obor D, Kwaro D, Wang D, Mehta SD, Phillips-Howard PA. Impact of COVID-19 lockdowns on adolescent pregnancy and school dropout among secondary schoolgirls in Kenya. BMJ Glob Health [Internet]. 2022 Jan 13[cited 2025 Mar 26];7(1):e007666. Available from: https://gh.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007666 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007666

- Wireko-Gyebi RS, King RS, Braimah I, Lykke AM. Local knowledge of risks associated with artisanal small-scale mining in Ghana. Int J Occup Saf Ergon [Internet]. 2020 Aug 27 [cited 2025 Mar 26];28(1):528–35. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10803548.2020.1795374 https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2020.1795374

- Mensah J, Amoah JO, Nketsiah‐Essoun A. Effects of artisanal gold mining and routes towards sustainable development for a low‐profile mining community in Ghana. Natural Resources Forum [Internet]. 2024 Mar 13 [cited 2025 Mar 26];1477-8947.12431. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1477-8947.12431 https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-8947.12431 Purchase or subscription required to view full text.

- Gay C, Clements‐Nolle K, Packham J, Ackerman G, Lensch T, Yang W. Community‐level exposure to the rural mining industry: the potential influence on early adolescent alcohol and tobacco use. The Journal of Rural Health [Internet]. 2018 Jan 31 [cited 2025 Mar 26];34(3):304–13. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jrh.12288 https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12288

- Dahmen B, Konrad K, Jahnen L, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Firk C. Psychische Gesundheit von Teenagermüttern: Auswirkungen auf die nächste Generation [Teenage Mothers’ Mental Health: Impact on the Next Generation]. Nervenarzt [Internet]. 2019 Jan 14 [cited 2025 Mar 26];90(3):243–50. German. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00115-018-0661-7 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-018-0661-7 Purchase or subscription required to view full text

Menu, Tables and Figures

On Pubmed

Navigate this article

Figures

Keywords

- Adolescent pregnancy

- Savannah Region

- Period prevalence

- Age-specific adolescent birth rate